Daguerrotypes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Daguerreotype (; french: daguerréotype) was the first publicly available

Daguerreotype (; french: daguerréotype) was the first publicly available  To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated

To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated

In 1829

In 1829  The written contract drawn up between Nicéphore Niépce and Daguerre includes an undertaking by Niépce to release details of the process he had invented – the asphalt process or heliography. Daguerre was sworn to secrecy under penalty of damages and undertook to design a camera and improve the process. The improved process was eventually named the

The written contract drawn up between Nicéphore Niépce and Daguerre includes an undertaking by Niépce to release details of the process he had invented – the asphalt process or heliography. Daguerre was sworn to secrecy under penalty of damages and undertook to design a camera and improve the process. The improved process was eventually named the  To exploit the invention four hundred shares would be on offer for a thousand francs each; secrecy would be lifted after a hundred shares had been sold, or the rights of the process could be bought for twenty thousand francs.

Daguerre wrote to Isidore Niepce on 2 January 1839 about his discussion with Arago:

To exploit the invention four hundred shares would be on offer for a thousand francs each; secrecy would be lifted after a hundred shares had been sold, or the rights of the process could be bought for twenty thousand francs.

Daguerre wrote to Isidore Niepce on 2 January 1839 about his discussion with Arago:

/ref> Nevertheless, he benefited from the state pension awarded to him together with Daguerre. Miles Berry, a patent agent acting on Daguerre's and Isidore Niépce's behalf in England, wrote a six-page memorial to the Board of the Treasury in an attempt to repeat the French arrangement in Great Britain, 'for the purpose of throwing it open in England for the benefit of the public.' The Treasury wrote to Miles Berry on 3 April to inform him of their decision: Without bills being passed by Parliament, as had been arranged in France, Arago having presented a bill in the House of Deputies and Gay-Lussac in the Chamber of Peers, there was no possibility of repeating the French arrangement in England which is why the daguerreotype was given free to the world by the French government with the exception of England and Wales for which Richard Beard controlled the patent rights. Daguerre patented his process in England, and Richard Beard patented his improvements to the process in Scotland During this time the astronomer and member of the House of Deputies

A further clue to fixing the date of invention of the process is that when the Paris correspondent of the London periodical '' The Athenaeum'' reported the public announcement of the daguerreotype in 1839, he mentioned that the daguerreotypes now being produced were of considerably better quality than the ones he had seen "four years earlier".

At a joint meeting of the

A further clue to fixing the date of invention of the process is that when the Paris correspondent of the London periodical '' The Athenaeum'' reported the public announcement of the daguerreotype in 1839, he mentioned that the daguerreotypes now being produced were of considerably better quality than the ones he had seen "four years earlier".

At a joint meeting of the  Daguerre was present but complained of a sore throat. Later that year

Daguerre was present but complained of a sore throat. Later that year

The ''

The ''

Even when strengthened by gilding, the image surface was still very easily marred and air would tarnish the silver, so the finished plate was bound up with a protective cover glass and sealed with strips of paper soaked in

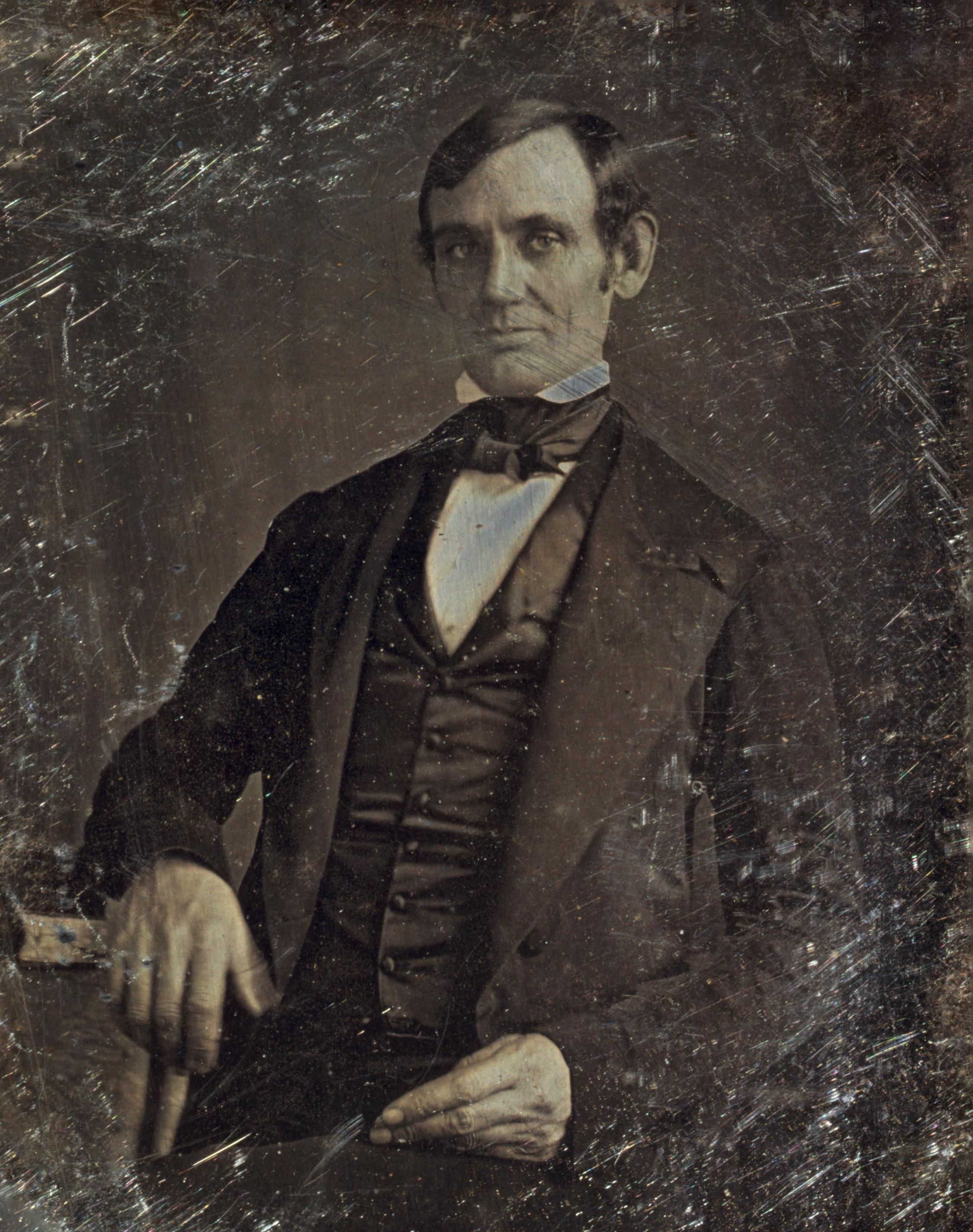

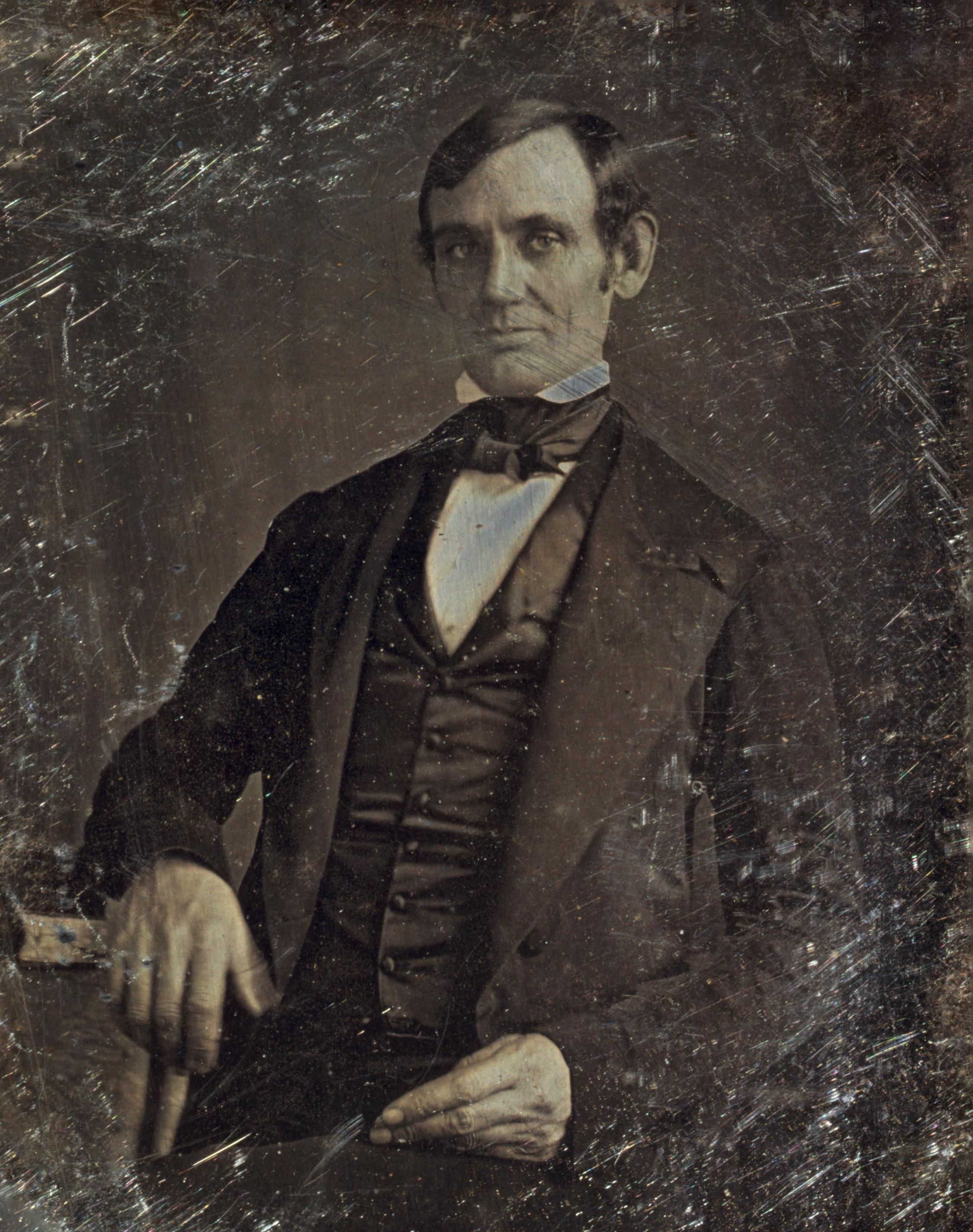

Even when strengthened by gilding, the image surface was still very easily marred and air would tarnish the silver, so the finished plate was bound up with a protective cover glass and sealed with strips of paper soaked in  Conservators were able to determine that a daguerreotype of

Conservators were able to determine that a daguerreotype of

Daguerreotypes are normally laterally reversed—mirror images—because they are necessarily viewed from the side that originally faced the camera lens. Although a daguerreotypist could attach a mirror or

Daguerreotypes are normally laterally reversed—mirror images—because they are necessarily viewed from the side that originally faced the camera lens. Although a daguerreotypist could attach a mirror or

Even with fast lenses and much more sensitive plates, under portrait studio lighting conditions an exposure of several seconds was necessary on the brightest of days, and on hazy or cloudy days the sitter had to remain still for considerably longer. The head rest was already in use for portrait painting.

Establishments producing daguerreotype portraits generally had a daylight studio built on the roof, much like a greenhouse. Whereas later in the history of photography artificial electric lighting was done in a dark room, building up the light with hard spotlights and softer floodlights, the daylight studio was equipped with screens and blinds to control the light, to reduce it and make it unidirectional, or diffuse it to soften harsh direct lighting. Blue filtration was sometimes used to make it easier for the sitter to tolerate the strong light, as a daguerreotype plate was almost exclusively sensitive to light at the blue end of the spectrum and filtering out everything else did not significantly increase the exposure time.

Usually, it was arranged so that sitters leaned their elbows on a support such as a posing table, the height of which could be adjusted, or else head rests were used that did not show in the picture, and this led to most daguerreotype portraits having stiff, lifeless poses. Some exceptions exist, with lively expressions full of character, as photographers saw the potential of the new medium, and would have used the

Even with fast lenses and much more sensitive plates, under portrait studio lighting conditions an exposure of several seconds was necessary on the brightest of days, and on hazy or cloudy days the sitter had to remain still for considerably longer. The head rest was already in use for portrait painting.

Establishments producing daguerreotype portraits generally had a daylight studio built on the roof, much like a greenhouse. Whereas later in the history of photography artificial electric lighting was done in a dark room, building up the light with hard spotlights and softer floodlights, the daylight studio was equipped with screens and blinds to control the light, to reduce it and make it unidirectional, or diffuse it to soften harsh direct lighting. Blue filtration was sometimes used to make it easier for the sitter to tolerate the strong light, as a daguerreotype plate was almost exclusively sensitive to light at the blue end of the spectrum and filtering out everything else did not significantly increase the exposure time.

Usually, it was arranged so that sitters leaned their elbows on a support such as a posing table, the height of which could be adjusted, or else head rests were used that did not show in the picture, and this led to most daguerreotype portraits having stiff, lifeless poses. Some exceptions exist, with lively expressions full of character, as photographers saw the potential of the new medium, and would have used the

The Gallery of the Louvre

Morse used a Camera obscura to precisely capture the gallery which he then used to create the final painting. Morse met the inventor of the daguerreotype, Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre, in Paris in January 1839 when Daguerre's invention was announced While the daguerreotype fascinated Morse, he was concerned about how the new invention would compete with his telegraph. However, Morse's viewing of the daguerreotype alleviated his fears when he saw how revolutionary its technology was. Morse wrote a letter to his brother Sidney describing Daguerre's invention, which Sidney then published in the New-York Observer on April 20, 1839. While this was not the first report of the daguerreotype to appear in America, it was the first in-person report to appear in the United States. Morse's account of the brand-new invention interested the American public, and through further publishings the technique of the daguerreotype was integrated into the United States. Magazines and newspapers included essays applauding the daguerreotype for advancing democratic American values because it could create an image without painting, which was less efficient and more expensive. The introduction of the daguerreotype to America also promoted progress of ideals and technology. For example, an article published in the Boston Daily Advertiser on February 23, 1839 described the daguerreotype as having similar properties of the camera obscura, but introduced its remarkable capability of "fixing the image permanently on the paper, or making a permanent drawing, by the agency of light alone," which combined old and new concepts for readers to understand. By 1853, an estimated three million daguerreotypes per year were being produced in the United States alone. One of these original Morse Daguerreotype cameras is currently on display at the

File:Dagbox.jpg, Small Wooden box containing uncased primitive daguerreotypes. They are the early work of Dr John Draper and Samuel Morse at NYU in the fall of 1839. A failed image attempt and four good images from the box are posted in this gallery.

File:Failed Image 1839.jpg, Failed image attempt by John W Draper from the box containing his early efforts at making daguerreotypes at NYU in the fall of 1839

File:Dr John W Draper.jpg, Dr John William Draper, long credited as the first person to take an image of the human face, sitting with his plant experiment , pen in hand, at NYU in the fall of 1839. Daguerreotype by Samuel Morse 1839.

File:Samuel Morse 1839.jpg, Samuel Morse, Art Professor at NYU in 1839. Daguerreotype by Dr John William Draper 1839.

File:Freylinghuysen.jpg,

The Daguerreotype. Photographic Processes. Series Chapter 2 of 12. George Eastman Museum

The Daguerreian Society

A predominantly US oriented database & galleries

The Daguerreotype: an Archive of Source Texts, Graphics, and Ephemera

Historique et description des procédés du daguerréotype rédigés par Daguérre, ornés du portrait de l'auteur, et augmentés de notes et d'observations par MM Lerebours et Susse Frères, Lerebours, Opticien de L'Observatoire; Susse Frères, Éditeurs. Paris 1839

''Daguerre's Daguerreotype Manual.'' *

at rochester.edu

International Contemporary Daguerreotypes community (non-profit org)

The Social Construction of the American Daguerreotype Portrait

Daguerreotype Plate Sizes

Daguerreotype collection at the Canadian Centre for Architecture

*

* ttp://www.museedebry.fr/#/homepage-daguerre/en Website of Bry-Sur-Marne's Museum– Enhancement of the museum's collections, some are related with the work of Louis Daguerre and the Daguerreotype {{Authority control Photographic processes dating from the 19th century Audiovisual introductions in 1839 French inventions Alternative photographic processes Monochrome photography Mercury (element) 19th century in art 19th-century photography

Daguerreotype (; french: daguerréotype) was the first publicly available

Daguerreotype (; french: daguerréotype) was the first publicly available photographic

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating durable images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is employed i ...

process; it was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process.

Invented by Louis Daguerre

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre ( , ; 18 November 1787 – 10 July 1851) was a French artist and photographer, recognized for his invention of the eponymous daguerreotype process of photography. He became known as one of the fathers of photog ...

and introduced worldwide in 1839, the daguerreotype was almost completely superseded by 1860 with new, less expensive processes, such as ambrotype

The ambrotype (from grc, ἀμβροτός — “immortal”, and — “impression”) also known as a collodion positive in the UK, is a positive photograph on glass made by a variant of the wet plate collodion process. Like a pr ...

(collodion process

The collodion process is an early photographic process. The collodion process, mostly synonymous with the "collodion wet plate process", requires the photographic material to be coated, sensitized, exposed, and developed within the span of about ...

), that yield more readily viewable images. There has been a revival of the daguerreotype since the late 20th century by a small number of photographers interested in making artistic use of early photographic processes.

To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated

To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

to a mirror finish; treated it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive; exposed

Expose, exposé, or exposed may refer to:

News sources

* Exposé (journalism), a form of investigative journalism

* ''The Exposé'', a British conspiracist website

Film and TV Film

* ''Exposé'' (film), a 1976 thriller film

* ''Exposed'' (1932 ...

it in a camera

A camera is an Optics, optical instrument that can capture an image. Most cameras can capture 2D images, with some more advanced models being able to capture 3D images. At a basic level, most cameras consist of sealed boxes (the camera body), ...

for as long as was judged to be necessary, which could be as little as a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or much longer with less intense lighting; made the resulting latent image

{{citations needed, date=November 2015

A latent image is an invisible image produced by the exposure to light of a photosensitive material such as photographic film. When photographic film is developed, the area that was exposed darkens and forms ...

on it visible by fuming it with mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

vapor; removed its sensitivity to light by liquid chemical treatment; rinsed and dried it; and then sealed the easily marred result behind glass in a protective enclosure.

The image is on a mirror-like silver surface and will appear either positive or negative, depending on the angle at which it is viewed, how it is lit and whether a light or dark background is being reflected in the metal. The darkest areas of the image are simply bare silver; lighter areas have a microscopically fine light-scattering texture. The surface is very delicate, and even the lightest wiping can permanently scuff it. Some tarnish

Tarnish is a thin layer of corrosion that forms over copper, brass, aluminum, magnesium, neodymium and other similar metals as their outermost layer undergoes a chemical reaction. Tarnish does not always result from the sole effects of oxygen in ...

around the edges is normal.

Several types of antique photographs, most often ambrotypes and tintype

A tintype, also known as a melainotype or ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. Tintypes enjoyed their wi ...

s, but sometimes even old prints on paper, are commonly misidentified as daguerreotypes, especially if they are in the small, ornamented cases in which daguerreotypes made in the US and the UK were usually housed. The name "daguerreotype" correctly refers only to one very specific image type and medium, the product of a process that was in wide use only from the early 1840s to the late 1850s.

History

Since theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

era, artists and inventors had searched for a mechanical method of capturing visual scenes. Using the camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a aperture, small hole or lens at one side through which an image is 3D projection, projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions su ...

, artists would manually trace what they saw, or use the optical image as a basis for solving the problems of perspective and parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby objects ...

, and deciding color values. The camera obscura's optical reduction of a real scene in three-dimensional space

Three-dimensional space (also: 3D space, 3-space or, rarely, tri-dimensional space) is a geometric setting in which three values (called ''parameters'') are required to determine the position (geometry), position of an element (i.e., Point (m ...

to a flat rendition in two dimensions

In mathematics, a plane is a Euclidean ( flat), two-dimensional surface that extends indefinitely. A plane is the two-dimensional analogue of a point (zero dimensions), a line (one dimension) and three-dimensional space. Planes can arise as ...

influenced western art

The art of Europe, or Western art, encompasses the history of visual art in Europe. European prehistoric art started as mobile Upper Paleolithic rock and cave painting and petroglyph art and was characteristic of the period between the Paleol ...

, so that at one point, it was thought that images based on optical geometry (perspective) belonged to a more advanced civilization. Later, with the advent of Modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

, the absence of perspective in oriental art

The history of Asian art includes a vast range of arts from various cultures, regions, and religions across the continent of Asia. The major regions of Asia include Central, East, South, Southeast, and West Asia.

Central Asian art primarily co ...

from China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and in Persian miniature

A Persian miniature (Persian: نگارگری ایرانی ''negârgari Irâni'') is a small Persian painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a ''muraqqa''. The ...

s was revalued.

In the early seventeenth century, the Italian physician and chemist Angelo Sala

Angelo Sala (Latin: Angelus Sala) (21 March 1576, Vicenza – 2 October 1637, Bützow) was an Italian doctor and early iatrochemist. He promoted chemical remedies and, drawing on the relative merits of the conflicting chemical and Galenical syst ...

wrote that powdered silver nitrate was blackened by the sun, but did not find any practical application of the phenomenon.

The discovery and commercial availability of the halogens—iodine

Iodine is a chemical element with the symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid at standard conditions that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

, bromine

Bromine is a chemical element with the symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is the third-lightest element in group 17 of the periodic table (halogens) and is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a simila ...

and chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate betwee ...

a few years earlier (iodine was discovered by Courtois Courtois can refer to:

Locations

*Courtois-sur-Yonne, a commune in Yonne department, France

*Courtois, Missouri, an unincorporated community

*Courtois Creek, a creek in Missouri

*Courtois Hills, a region in Missouri

Persons Painters

*Jean Cour ...

in 1811, bromine by Löwig in 1825 and Balard in 1826 independently, and chlorine by Scheele

Scheele is a surname of Germanic origin. Notable people with the surname include:

*Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742–1786), German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist

*George Heinrich Adolf Scheele (1808–1864), German botanist

* Karin Scheele (b. 1968), ...

in 1774)—meant that silver photographic processes that rely on the reduction of silver iodide

Silver iodide is an inorganic compound with the formula Ag I. The compound is a bright yellow solid, but samples almost always contain impurities of metallic silver that give a gray coloration. The silver contamination arises because AgI is hig ...

, silver bromide

Silver bromide (AgBr) is a soft, pale-yellow, water-insoluble salt well known (along with other silver halides) for its unusual sensitivity to light. This property has allowed silver halides to become the basis of modern photographic materials. A ...

and silver chloride

Silver chloride is a chemical compound with the chemical formula Ag Cl. This white crystalline solid is well known for its low solubility in water (this behavior being reminiscent of the chlorides of Tl+ and Pb2+). Upon illumination or heating, ...

to metallic silver became feasible. The daguerreotype is one of these processes, but was not the first, as Niépce had experimented with paper silver chloride negatives while Wedgwood's experiments were with silver nitrate as were Schultze's stencils of letters. Hippolyte Bayard

Hippolyte Bayard (20 January 1801 – 14 May 1887) was a French photographer and pioneer in the history of photography. He invented his own process that produced direct positive paper prints in the camera and presented the world's first public e ...

had been persuaded by François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago ( ca, Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: ''Francesc Aragó'', ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of t ...

to wait before making his paper process public.

Previous discoveries of photosensitive methods and substances—including silver nitrate

Silver nitrate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula . It is a versatile precursor to many other silver compounds, such as those used in photography. It is far less sensitive to light than the halides. It was once called ''lunar caustic' ...

by Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop. Later canonised as a Catholic saint, he was known during his life ...

in the 13th century, a silver and chalk mixture by Johann Heinrich Schulze

Johann Heinrich Schulze (12 May 1687 – 10 October 1744) was a German professor and polymath.

History

Schulze studied medicine, chemistry, philosophy and theology and became a professor in Altdorf and Halle for anatomy and several other ...

in 1724, and Joseph Niépce's bitumen

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term a ...

-based heliography

Heliography (in French, ''héliographie)'' from ''helios'' (Greek: ''ἥλιος'')'','' meaning "sun"'','' and ''graphein (γράφειν),'' "writing") is the photographic process invented, and named thus, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce around ...

in 1822 contributed to development of the daguerreotype.

The first reliably documented attempt to capture the image formed in a camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a aperture, small hole or lens at one side through which an image is 3D projection, projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions su ...

was made by Thomas Wedgwood as early as the 1790s, but according to an 1802 account of his work by Sir Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for t ...

:

The images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver. To copy these images was the first object of Mr. Wedgwood in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used the nitrate of silver, which was mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensible to the influence of light; but all his numerous experiments as to their primary end proved unsuccessful.

Development in France

In 1829

In 1829 French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

artist and chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

Louis Daguerre, when obtaining a camera obscura for his work on theatrical scene painting from the optician Chevalier, was put into contact with Nicéphore Niépce

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (; 7 March 1765 – 5 July 1833), commonly known or referred to simply as Nicéphore Niépce, was a French inventor, usually credited with the invention of photography. Niépce developed heliography, a technique he use ...

, who had already managed to make a record of an image from a camera obscura using the process he invented: heliography

Heliography (in French, ''héliographie)'' from ''helios'' (Greek: ''ἥλιος'')'','' meaning "sun"'','' and ''graphein (γράφειν),'' "writing") is the photographic process invented, and named thus, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce around ...

.

Daguerre met with Niépce and entered into correspondence with him. Niépce had invented an early internal combustion engine (the Pyréolophore

The Pyréolophore () was probably the world's first internal combustion engine. It was invented in the early 19th century in Chalon-sur-Saône, France, by the Niépce brothers: Nicéphore (who went on to invent photography) and Claude. In 1807 ...

) together with his brother Claude and made improvements to the velocipede, as well as experimenting with lithography and related processes. Their correspondence reveals that Niépce was at first reluctant to divulge any details of his work with photographic images. To guard against letting any secrets out before the invention had been improved, they used a numerical code for security. 15, for example, signified the tanning action of the sun on human skin (''action solaire sur les corps''); 34 – a camera obscura (''chambre noir''); 73 – sulphuric acid.

The written contract drawn up between Nicéphore Niépce and Daguerre includes an undertaking by Niépce to release details of the process he had invented – the asphalt process or heliography. Daguerre was sworn to secrecy under penalty of damages and undertook to design a camera and improve the process. The improved process was eventually named the

The written contract drawn up between Nicéphore Niépce and Daguerre includes an undertaking by Niépce to release details of the process he had invented – the asphalt process or heliography. Daguerre was sworn to secrecy under penalty of damages and undertook to design a camera and improve the process. The improved process was eventually named the physautotype

The physautotype (from French, ''physautotype'') was a photographic process, invented in the course of his investigation of heliography, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre in 1832, in which images were produced by the us ...

.

Niépce's early experiments had derived from his interest in lithography and consisted of capturing the image in a camera (then called a camera obscura), resulting in an engraving that could be printed through various lithographic processes. The asphalt process or heliography required exposures that were so long that Arago said it was not fit for use. Nevertheless, without Niépce's experiments, it is unlikely that Daguerre would have been able to build on them to adapt and improve what turned out to be the daguerreotype process.

After Niépce's death in 1833, his son, Isidore, inherited rights in the contract and a new version was drawn up between Daguerre and Isidore. Isidore signed the document admitting that the old process had been improved to the limits that were possible and that a new process that would bear Daguerre's name alone was sixty to eighty times as rapid as the old asphalt (bitumen) one his father had invented. This was the daguerreotype process that used iodized silvered plates and was developed with mercury fumes.

To exploit the invention four hundred shares would be on offer for a thousand francs each; secrecy would be lifted after a hundred shares had been sold, or the rights of the process could be bought for twenty thousand francs.

Daguerre wrote to Isidore Niepce on 2 January 1839 about his discussion with Arago:

To exploit the invention four hundred shares would be on offer for a thousand francs each; secrecy would be lifted after a hundred shares had been sold, or the rights of the process could be bought for twenty thousand francs.

Daguerre wrote to Isidore Niepce on 2 January 1839 about his discussion with Arago:

He sees difficulty with this proceeding by subscription; it is almost certain – just as I myself have been convinced ever since looking on my first specimens – that subscription would not serve. Everyone says it is superb: but it will cost us the thousand francs before we learn itIsidore did not contribute anything to the invention of the Daguerreotype and he was not let in on the details of the invention.Isidore Niépce and Daguerrehe process He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...and be able to judge if it could remain secret. M. de Mandelot himself knows several persons who could subscribe but will not do so because they think ithe secret He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...would be revealed by itself, and now I have proof that many think in this way. I entirely agree with the idea of M. Arago, that is get the government to purchase this discovery, and that he himself would pursue this in the chambre. I have already seen several deputies who are of the same opinion and would give support; this way it seems to me to have the most chance of success; thus, my dear friend, I think it is the best option, and everything makes me think we will not regret it. For a start M. Arago will speak next Monday at the Académie des Sciences ...

/ref> Nevertheless, he benefited from the state pension awarded to him together with Daguerre. Miles Berry, a patent agent acting on Daguerre's and Isidore Niépce's behalf in England, wrote a six-page memorial to the Board of the Treasury in an attempt to repeat the French arrangement in Great Britain, 'for the purpose of throwing it open in England for the benefit of the public.' The Treasury wrote to Miles Berry on 3 April to inform him of their decision: Without bills being passed by Parliament, as had been arranged in France, Arago having presented a bill in the House of Deputies and Gay-Lussac in the Chamber of Peers, there was no possibility of repeating the French arrangement in England which is why the daguerreotype was given free to the world by the French government with the exception of England and Wales for which Richard Beard controlled the patent rights. Daguerre patented his process in England, and Richard Beard patented his improvements to the process in Scotland During this time the astronomer and member of the House of Deputies

François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago ( ca, Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: ''Francesc Aragó'', ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of t ...

had sought a solution whereby the invention would be given free to the world by the passing of Acts in the French Parliament. Richard Beard, controlled most of the licences in England and Wales with the exception of Antoine Claudet

Ada Byron's daguerreotype by Claudet, .

Antoine François Jean Claudet (August 18, 1797 – December 27, 1867) was a French photographer and artist active in London who produced daguerreotypes.

Early Years

Claudet was born in La Croix-Rousse ...

who had purchased a licence directly from Daguerre.

In the US, Alexander S. Wolcott

Alexander Simon Wolcott (June 14, 1804 – November 10, 1844) was an American inventor, experimental photographer, and medical supply manufacturer. With John Johnson, he established the world's first commercial photography portrait studio and p ...

invented the mirror daguerreotype camera, according to John Johnson's account, in one single day after reading the description of the daguerreotype process published in English translation.

Johnson's father travelled to England with some specimen portraits to patent the camera and met with Richard Beard who bought the patent for the camera, and a year later bought the patent for the daguerreotype outright. Johnson assisted Beard in setting up a portrait studio on the roof of the Regent Street Polytechnic and managed Beard's daguerreotype studio in Derby and then Manchester for some time before returning to the US.

Wolcott's Mirror Camera, which gave postage stamp sized miniatures, was in use for about two years before it was replaced by Petzval's Portrait lens, which gave larger and sharper images.

Antoine Claudet

Ada Byron's daguerreotype by Claudet, .

Antoine François Jean Claudet (August 18, 1797 – December 27, 1867) was a French photographer and artist active in London who produced daguerreotypes.

Early Years

Claudet was born in La Croix-Rousse ...

had purchased a licence from Daguerre directly to produce daguerreotypes. His uncle, the banker Vital Roux, arranged that he should head the glass factory at Choisy-le-Roi together with Georges Bontemps

Georges Bontemps was a director of an eminent French glass manufacturer in the 19th century, moved to England to work and is accredited with the re-invention of a technique for making ruby-coloured glass that was first used by the Venetians in the ...

and moved to England to represent the factory with a showroom in High Holborn. At one stage, Beard sued Claudet with the aim of claiming that he had a monopoly of daguerreotypy in England, but lost. Niépce's aim originally had been to find a method to reproduce prints and drawings for lithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

. He had started out experimenting with light-sensitive materials and had made a contact print from a drawing and then went on to successfully make the first photomechanical record of an image in a camera obscura – the world's first photograph. Niépce's method was to coat a pewter plate with bitumen of Judea (asphalt) and the action of the light differentially hardened the bitumen. The plate was washed with a mixture of oil of lavender and turpentine leaving a relief image. Later, Daguerre's and Niépce's improvement to the heliograph process, the physautotype, reduced the exposure to eight hours.

Early experiments required hours of exposure in the camera to produce visible results. Modern photo-historians consider the stories of Daguerre discovering mercury development by accident because of a bowl of mercury left in a cupboard, or, alternatively, a broken thermometer, to be spurious.

Another story of a fortunate accident, which modern photo historians are now doubtful about, and was related by Louis Figuier, of a silver spoon lying on an iodized silver plate which left its design on the plate by light perfectly. Noticing this, Daguerre supposedly wrote to Niépce on 21 May 1831 suggesting the use of iodized silver plates as a means of obtaining light images in the camera.

Daguerre did not give a clear account of his method of discovery and allowed these legends to become current after the secrecy had been lifted.

Letters from Niépce to Daguerre dated 24 June and 8 November 1831, show that Niépce was unsuccessful in obtaining satisfactory results following Daguerre's suggestion, although he had produced a negative on an iodized silver plate in the camera. Niépce's letters to Daguerre dated 29 January and 3 March 1832 show that the use of iodized silver plates was due to Daguerre and not Niépce.

Jean-Baptiste Dumas

Jean Baptiste André Dumas (14 July 180010 April 1884) was a French chemist, best known for his works on organic analysis and synthesis, as well as the determination of atomic weights (relative atomic masses) and molecular weights by measuring v ...

, who was president of the National Society for the Encouragement of Science (Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale

Lactalis is a French multinational dairy products corporation, owned by the Besnier family and based in Laval, Mayenne, France. The company's former name was Besnier SA.

Lactalis is the largest dairy products group in the world, and is the sec ...

) and a chemist, put his laboratory at Daguerre's disposal. According to Austrian chemist Josef Maria Eder

Josef Maria Eder (16 March 1855 – 18 October 1944) was an Austrian chemist who specialized in the chemistry of photography, and who wrote a comprehensive early history of the technical development of chemical photography.

Life and work

Eder was ...

, Daguerre was not versed in chemistry and it was Dumas who suggested Daguerre use sodium hyposulfite, discovered by Herschel in 1819, as a fixer to dissolve the unexposed silver salts.

First mention in print (1835) and public announcement (1839)

A paragraph tacked onto the end of a review of one of Daguerre'sDiorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

spectacles in the ''Journal des artistes'' on 27 September 1835, a Diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

painting of a landslide that occurred in "La Vallée de Goldau

Goldau is a town in the community of Arth, canton of Schwyz, Switzerland. It lies between the Rigi and Rossberg mountains, and between lakes Zug and Lauerz.

Well known attractions include the Natur- und Tierpark Goldau and the Arth-Goldau valle ...

", made passing mention of rumour that was going around the Paris studios of Daguerre's attempts to make a visual record on metal plates of the fleeting image produced by the camera obscura:

It is said that Daguerre has found the means to collect, on a plate prepared by him, the image produced by the camera obscura, in such a way that a portrait, a landscape, or any view, projected upon this plate by the ordinary camera obscura, leaves an imprint in light and shade there, and thus presents the most perfect of all drawings ... a preparation put over this image preserves it for an indefinite time ... the physical sciences have perhaps never presented a marvel comparable to this one.

A further clue to fixing the date of invention of the process is that when the Paris correspondent of the London periodical '' The Athenaeum'' reported the public announcement of the daguerreotype in 1839, he mentioned that the daguerreotypes now being produced were of considerably better quality than the ones he had seen "four years earlier".

At a joint meeting of the

A further clue to fixing the date of invention of the process is that when the Paris correspondent of the London periodical '' The Athenaeum'' reported the public announcement of the daguerreotype in 1839, he mentioned that the daguerreotypes now being produced were of considerably better quality than the ones he had seen "four years earlier".

At a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

and the Académie des Beaux-Arts

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

held at the ''Institut de Françe'' on Monday, 19 August 1839François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago ( ca, Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: ''Francesc Aragó'', ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of t ...

briefly referred to the earlier process that Niépce had developed and Daguerre had helped to improve without mentioning them by name (the heliograph and the physautotype) in rather disparaging terms stressing their inconvenience and disadvantages such as that exposures were so long as eight hours that required a full day's exposure during which time the sun had moved across the sky removing all trace of halftones or modelling in round objects, and the photographic layer was apt to peel off in patches, while praising the daguerreotype in glowing terms. Overlooking Nicéphore Niépce's contribution in this way led Niépce's son, Isidore to resent his father being ignored as having been the first to capture the image produced in a camera by chemical means, and Isidore wrote a pamphlet in defence of his father's reputation ''Histoire de la decouverte improprement nommé daguerréotype''(History of the discovery improperly named the daguerreotype)

Daguerre was present but complained of a sore throat. Later that year

Daguerre was present but complained of a sore throat. Later that year William Fox Talbot

William Henry Fox Talbot Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE Royal Astronomical Society, FRAS (; 11 February 180017 September 1877) was an English scientist, inventor, and photography pioneer who invented the Salt print, salted paper and calo ...

announced his silver chloride "sensitive paper" process.

Together, these announcements caused early commentators to choose 1839 as the year photography was born, or made public. Later, it became known that Niépce's role had been downplayed in Arago's efforts to publicize the daguerreotype, and the first photograph is recorded in Eder's ''History of Photography'' as having been taken in 1826 or 1827. Niépce's reputation as the real inventor of photography became known through his son Isidore's indignation that his father's early experiments had been overlooked or ignored although Nicéphore had revealed his process, which, at the time, was secret.

The phrase ''the birth of photography'' has been used by different authors to mean different things – either the publicizing of the process (in 1839) as a metaphor to indicate that previous to that the daguerreotype process had been kept secret; or, the date the first photograph was taken by or with a camera (using the asphalt process or heliography), thought to have been 1822, but Eder's research indicates that the date was more probably 1826 or later. Fox Talbot's first photographs, on the other hand, were made "in the brilliant summer of 1835."

Daguerre and Niépce had together signed a good agreement in which remuneration for the invention would be paid for by subscription. However, the campaign they launched to finance the invention failed. François Arago, whose views on the system of patenting inventions can be gathered from speeches he made later in the House of Deputies (he apparently thought the English patent system had advantages over the French one) did not think the idea of raising money by subscription to be a good one, and supported Daguerre by arranging for motions to be passed in both Houses of the French parliament.

Daguerre did not patent and profit from his invention in the usual way. Instead, it was arranged that the French government

The Government of France ( French: ''Gouvernement français''), officially the Government of the French Republic (''Gouvernement de la République française'' ), exercises executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister, who ...

would acquire the rights in exchange for lifetime pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

s to Daguerre and to Niépce's son and heir, Isidore. The government would then present the daguerreotype process "free to the world" as a gift, which it did on 19 August 1839. However, five days previous to this, Miles Berry, a patent agent

A patent attorney is an attorney who has the specialized qualifications necessary for representing clients in obtaining patents and acting in all matters and procedures relating to patent law and practice, such as filing patent applications and op ...

acting on Daguerre's behalf filed for patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

No. 8194 of 1839: "A New or Improved Method of Obtaining the Spontaneous Reproduction of all the Images Received in the Focus of the Camera Obscura". The patent applied to "England, Wales, and the town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, and in all her Majesty's Colonies and Plantations abroad". This was the usual wording of English patent specifications before 1852. It was only after the 1852 Act, which unified the patent systems of England, Ireland and Scotland, that a single patent protection was automatically extended to the whole of the British Isles, including the Channel Isles and the Isle of Man. Richard Beard bought the patent rights from Miles Berry, and also obtained a Scottish patent, which he apparently did not enforce. The United Kingdom and the "Colonies and Plantations abroad" therefore became the only places where a license was legally required to make and sell daguerreotypes.

Much of Daguerre's early work was destroyed when his home and studio caught fire on 8 March 1839, while the painter Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

was visiting from the US. Malcolm Daniel points out that "fewer than twenty-five securely attributed photographs by Daguerre survive—a mere handful of still lifes, Parisian views, and portraits from the dawn of photography."

''Camera obscura''

The ''

The ''camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a aperture, small hole or lens at one side through which an image is 3D projection, projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions su ...

'' (Latin for "dark chamber") in its simplest form is a naturally occurring phenomenon.

A broad-leaved tree in bright sunshine will provide conditions that fulfill the requirements of a pinhole camera

A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens but with a tiny aperture (the so-called ''pinhole'')—effectively a light-proof box with a small hole in one side. Light from a scene passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image o ...

or a camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a aperture, small hole or lens at one side through which an image is 3D projection, projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions su ...

: a bright light source (the sun), the shade that the leafy canopy provides, a flat surface onto which the image is projected and holes formed by the gaps between the leaves. The sun's image will show as a round disc, and, in a partial eclipse, as a crescent.

A clear description of a camera obscura is given by Leonardo da Vinci in Codex Atlanticus (1502): (he called it ''oculus artificialis'' which means "the artificial eye")

If the facade of a building, or a place, or a landscape is illuminated by the sun and a small hole is drilled in the wall of a room in a building facing this, which is not directly lighted by the sun, then all objects illuminated by the sun will send their images through this aperture and will appear, upside down, on the wall facing the hole.In another notebook, he wrote:

You will catch these pictures on a piece of white paper, which placed vertically in the room not far from that opening, and you will see all the above-mentioned objects on this paper in their natural shapes or colors, but they will appear smaller and upside down, on account of crossing of the rays at that aperture. If these pictures originate from a place which is illuminated by the sun, they will appear colored on the paper exactly as they are. The paper should be very thin and must be viewed from the back.In the 16th century,

Daniele Barbaro

Daniele Matteo Alvise Barbaro (also Barbarus) (8 February 1514 – 13 April 1570) was an Italian cleric and diplomat. He was also an architect, writer on architecture, and translator of, and commentator on, Vitruvius.

Barbaro's fame is chief ...

suggested replacing the small hole with a larger hole and an old man's spectacle lens (a biconvex lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

for correcting long-sightedness), which produced a much brighter and sharper image.

By the late 18th century, small, easily portable box-form units equipped with a simple lens, an internal mirror, and a ground glass

Ground glass is glass whose surface has been ground to produce a flat but rough (matte) finish, in which the glass is in small sharp fragments.

Ground glass surfaces have many applications, ranging from ornamentation on windows and table glassw ...

screen had become popular among affluent amateurs for making sketches of landscapes and architecture. The camera was pointed at the scene and steadied, a sheet of thin paper was placed on top of the ground glass, then a pencil or pen could be used to trace over the image projected from within. The beautiful but fugitive little light-paintings on the screen inspired several people to seek some way of capturing them more completely and effectively—and automatically—by means of chemistry.

Daguerre, a skilled professional artist, was familiar with the ''camera obscura'' as an aid for establishing correct proportion and perspective, sometimes very useful when planning out the celebrated theatrical scene backdrops he painted and the even larger ultra-realistic panoramas he exhibited in his popular Diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

.

Plate manufacture

The daguerreotype image is formed on a highly polishedsilver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

surface. Usually the silver is a thin layer on a copper substrate, but other metals such as brass can be used for the substrate and daguerreotypes can also be made on solid silver sheets. A surface of very pure silver is preferable, but sterling (92.5% pure) or US coin (90% pure) or even lower grades of silver are functional. In 19th century practice, the usual stock material, Sheffield plate

Sheffield plate is a layered combination of silver and copper that was used for many years to produce a wide range of household articles. Almost every article made in sterling silver was also crafted by Sheffield makers, who used this manufactur ...

, was produced by a process sometimes called plating by fusion. A sheet of sterling silver was heat-fused onto the top of a thick copper ingot. When the ingot was repeatedly rolled under pressure to produce thin sheets, the relative thicknesses of the two layers of metal remained constant. The alternative was to electroplate

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct electric current. The part to be ...

a layer of pure silver onto a bare copper sheet. The two technologies were sometimes combined, the Sheffield plate being given a finishing coat of pure silver by electroplating.

In order that the corners of the plate would not tear the buffing material when the plate was polished, the edges of the plate were bent back using patented devices that could also serve as plate holders to avoid touching the surface of the plate during processing.

Process

Polishing

To optimize the image quality of the end product, the silver side of the plate had to be polished to as nearly perfect a mirror finish as possible. The silver had to be completely free of tarnish or other contamination when it was sensitized, so the daguerreotypist had to perform at least the final portion of the polishing and cleaning operation not too long before use. In the 19th century, the polishing was done with a buff covered with hide or velvet, first usingrotten stone

Rotten stone, sometimes spelled as rottenstone, also known as tripoli, is fine powdered porous rock used as a polishing abrasive for metalsmithing and in woodworking. It is usually weathered limestone mixed with diatomaceous, amorphous, or crysta ...

, then jeweler's rouge, then lampblack

Carbon black (subtypes are acetylene black, channel black, furnace black, lamp black and thermal black) is a material produced by the incomplete combustion of coal and coal tar, vegetable matter, or petroleum products, including fuel oil, fluid ...

. Originally, the work was entirely manual, but buffing machinery was soon devised to assist. Finally, the surface was swabbed with nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

to burn off any residual organic matter.

Sensitization

In darkness or by the light of asafelight

A safelight is a light source suitable for use in a photographic darkroom. It provides illumination only from parts of the visible spectrum to which the photographic material in use is nearly, or completely insensitive.

Design

A safelight usua ...

, the silver surface was exposed to halogen

The halogens () are a group in the periodic table consisting of five or six chemically related elements: fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), iodine (I), astatine (At), and tennessine (Ts). In the modern IUPAC nomenclature, this group is ...

fumes. Originally, only iodine

Iodine is a chemical element with the symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid at standard conditions that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

fumes (from iodine crystals at room temperature) were used, producing a surface coating of silver iodide

Silver iodide is an inorganic compound with the formula Ag I. The compound is a bright yellow solid, but samples almost always contain impurities of metallic silver that give a gray coloration. The silver contamination arises because AgI is hig ...

, but it was soon found that a subsequent exposure to bromine

Bromine is a chemical element with the symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is the third-lightest element in group 17 of the periodic table (halogens) and is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a simila ...

fumes greatly increased the sensitivity of the silver halide

A silver halide (or silver salt) is one of the chemical compounds that can form between the element silver (Ag) and one of the halogens. In particular, bromine (Br), chlorine (Cl), iodine (I) and fluorine (F) may each combine with silver to prod ...

coating. Exposure to chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate betwee ...

fumes, or a combination of bromine and chlorine fumes, could also be used. A final re-fuming with iodine was typical.

Exposure

The plate was then carried to the camera in a light-tight plate holder. Withdrawing a protectivedark slide

In photography, a dark slide is a wooden or metal plate that covers the sensitized emulsion side of a photographic plate. In use, a pair of plates joined back to back were used with both plates covered with a dark slide. When used, the dark slid ...

or opening a pair of doors in the holder exposed the sensitized surface within the dark camera and removing a cap from the camera lens began the exposure, creating an invisible latent image

{{citations needed, date=November 2015

A latent image is an invisible image produced by the exposure to light of a photosensitive material such as photographic film. When photographic film is developed, the area that was exposed darkens and forms ...

on the plate. Depending on the sensitization chemistry used, the brightness of the lighting, and the light-concentrating power of the lens, the required exposure time ranged from a few seconds to many minutes. After the exposure was judged to be complete, the lens was capped and the holder was again made light-tight and removed from the camera.

Development

The latent image was developed to visibility by several minutes of exposure to the fumes given off by heatedmercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

in a purpose-made developing box. The toxicity of mercury was well known in the 19th century, but precautionary measures were rarely taken. Today, however, the hazards of contact with mercury and other chemicals traditionally used in the daguerreotype process are taken more seriously, as is the risk of release of those chemicals into the environment.

In the Becquerel

The becquerel (; symbol: Bq) is the unit of radioactivity in the International System of Units (SI). One becquerel is defined as the activity of a quantity of radioactive material in which one nucleus decays per second. For applications relatin ...

variation of the process, published in 1840 but very rarely used in the 19th century, the plate, sensitized by fuming with iodine alone, was developed by overall exposure to sunlight passing through yellow, amber or red glass. The silver iodide in its unexposed condition was insensitive to the red end of the visible spectrum

The visible spectrum is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visual perception, visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called ''visible light'' or simply light. A typical human eye wil ...

of light and was unaffected, but the latent image created in the camera by the blue, violet and ultraviolet rays color-sensitized each point on the plate proportionally, so that this color-filtered "sunbath" intensified it to full visibility, as if the plate had been exposed in the camera for hours or days to produce a visible image without development. Becquerel daguerreotypes, when fully developed and fixed, typically take on a somewhat bluish hue. The image quality may not be as magnificently sharp as a daguerreotype developed using mercury vapor, although modern photographers pursuing daguerreotypy tend to favor the Becquerel process due to the hazards and expense of working with mercury.

Fixing

After development, the light sensitivity of the plate was arrested by removing the unexposed silver halide with a mild solution ofsodium thiosulfate

Sodium thiosulfate (sodium thiosulphate) is an inorganic compound with the formula . Typically it is available as the white or colorless pentahydrate, . The solid is an efflorescent (loses water readily) crystalline substance that dissolves well i ...

; Daguerre's initial method was to use a hot saturated solution of common salt.

Gilding, also called gold toning, was an addition to Daguerre's process introduced by Hippolyte Fizeau

Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau FRS FRSE MIF (; 23 September 181918 September 1896) was a French physicist, best known for measuring the speed of light in the namesake Fizeau experiment.

Biography

Fizeau was born in Paris to Louis and Beatrice Fiz ...

in 1840. It soon became part of the standard procedure. To give the steely gray image a slightly warmer tone and physically reinforce the powder-like silver particles of which it was composed, a gold chloride Gold chloride can refer to:

* Gold(I) chloride (gold monochloride), AuCl

* Gold(I,III) chloride (gold dichloride, tetragold octachloride), Au4Cl8

* Gold(III) chloride (gold trichloride, digold hexachloride), Au2Cl6

* Chloroauric acid

Chloroauric ...

solution was pooled onto the surface and the plate was briefly heated over a flame, then drained, rinsed and dried. Without this treatment, the image was as delicate as the "dust" on a butterfly's wing.

Casing and other display options

Even when strengthened by gilding, the image surface was still very easily marred and air would tarnish the silver, so the finished plate was bound up with a protective cover glass and sealed with strips of paper soaked in

Even when strengthened by gilding, the image surface was still very easily marred and air would tarnish the silver, so the finished plate was bound up with a protective cover glass and sealed with strips of paper soaked in gum arabic

Gum arabic, also known as gum sudani, acacia gum, Arabic gum, gum acacia, acacia, Senegal gum, Indian gum, and by other names, is a natural gum originally consisting of the hardened sap of two species of the '' Acacia'' tree, ''Senegalia sen ...

. In the US and UK, a gilt brass mat called a preserver in the US and a pinchbeck in Britain, was normally used to separate the image surface from the glass. In continental Europe, a thin cardboard mat or '' passepartout'' usually served that purpose.

There were two main methods of finishing daguerreotypes for protection and display:

In the US and Britain, the tradition of preserving miniature paintings in a wooden case covered with leather or paper stamped with a relief pattern continued through to the daguerreotype. Some daguerreotypists were portrait artists who also offered miniature portraits. Black-lacquered cases ornamented with inset mother of pearl

Nacre ( , ), also known as mother of pearl, is an organicinorganic composite material produced by some molluscs as an inner shell layer; it is also the material of which pearls are composed. It is strong, resilient, and iridescent.

Nacre is ...

were sometimes used. The more substantial Union case was made from a mixture of colored sawdust and shellac (the main component of wood varnish) formed in a heated mold to produce a decorative sculptural relief. The word "Union" referred to the sawdust and varnish mixture—the manufacture of Union cases began in 1856. In all types of cases, the inside of the cover was lined with velvet or plush or satin to provide a dark surface to reflect into the plate for viewing and to protect the cover glass. Some cases, however, held two daguerreotypes opposite each other. The cased images could be set out on a table or displayed on a mantelpiece

The fireplace mantel or mantelpiece, also known as a chimneypiece, originated in medieval times as a hood that projected over a fire grate to catch the smoke. The term has evolved to include the decorative framework around the fireplace, and ca ...

. Most cases were small and lightweight enough to easily carry in a pocket, although that was not normally done. The other approach, common in France and the rest of continental Europe, was to hang the daguerreotype on the wall in a frame, either simple or elaborate.

Conservators were able to determine that a daguerreotype of

Conservators were able to determine that a daguerreotype of Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among t ...

was made in New Orleans with the main clue being the type of frame, which was made for wall hanging in the French and continental style. Supporting evidence of the New Orleans origin was a scrap of paper from ''Le Mesager'', a New Orleans bilingual newspaper of the time, which had been used to glue the plate into the frame. Other clues used by historians to identify daguerreotypes are hallmarks in the silver plate and the distinctive patterns left by different photographers when polishing the plate with a leather buff, which leaves extremely fine parallel lines discernible on the surface.

As the daguerreotype itself is on a relatively thin sheet of soft metal, it was easily sheared down to sizes and shapes suited for mounting into lockets, as was done with miniature paintings. Other imaginative uses of daguerreotype portraits were to mount them in watch fobs and watch cases, jewel caskets and other ornate silver or gold boxes, the handles of walking stick

A walking stick or walking cane is a device used primarily to aid walking, provide postural stability or support, or assist in maintaining a good posture. Some designs also serve as a fashion accessory, or are used for self-defense.

Walking sti ...

s, and in brooches, bracelets and other jewelry now referred to by collectors as "daguerreian jewelry". The cover glass or crystal was sealed either directly to the edges of the daguerreotype or to the opening of its receptacle and a protective hinged cover was usually provided.

Unusual characteristics

Daguerreotypes are normally laterally reversed—mirror images—because they are necessarily viewed from the side that originally faced the camera lens. Although a daguerreotypist could attach a mirror or

Daguerreotypes are normally laterally reversed—mirror images—because they are necessarily viewed from the side that originally faced the camera lens. Although a daguerreotypist could attach a mirror or reflective prism

An optical prism is a transparent optical element with flat, polished surfaces that are designed to refract light. At least one surface must be angled — elements with two parallel surfaces are ''not'' prisms. The most familiar type of optical ...

in front of the lens to obtain a right-reading result, in practice this was rarely done.

The use of either type of attachment caused some light loss, somewhat increasing the required exposure time, and unless they were of very high optical quality they could degrade the quality of the image. Right-reading text or right-handed buttons on men's clothing in a daguerreotype may be the only evidence that the specimen is a copy of a typical wrong-reading original.

The experience of viewing a daguerreotype is unlike that of viewing any other type of photograph. The image does not sit on the surface of the plate. After flipping from positive to negative as the viewing angle is adjusted, viewers experience an apparition in space, a mirage that arises once the eyes are properly focused. When reproduced via other processes, this effect associated with viewing an original daguerreotype will no longer be apparent. Other processes that have a similar viewing experience are holograms

Holography is a technique that enables a wavefront to be recorded and later re-constructed. Holography is best known as a method of generating real three-dimensional images, but it also has a wide range of other applications. In principle, it ...

on credit cards or Lippmann plate

Gabriel Lippmann conceived a two-step method to record and reproduce colours, variously known as direct photochromes, interference photochromes, Lippmann photochromes, Photography in natural colours by direct exposure in the camera or the Lippman ...

s.

Although daguerreotypes are unique images, they could be copied by re-daguerreotyping the original. Copies were also produced by lithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

or engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a Burin (engraving), burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or Glass engraving, glass ...

. Today, they can be digitally scanned.

A well-exposed and sharp large-format daguerreotype is able to faithfully record fine detail at a resolution that today's digital cameras are not able to match.

Reduction of exposure time

In the early 1840s, two innovations were introduced that dramatically shortened the required exposure times: a lens that produced a much brighter image in the camera, and a modification of the chemistry used to sensitize the plate. The very first daguerreotype cameras could not be used for portraiture, as the exposure time required would have been too long. The cameras were fitted with Chevalierlenses

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

which were "slow

In everyday use and in kinematics, the speed (commonly referred to as ''v'') of an object is the magnitude (mathematics), magnitude of the change of its Position (vector), position over time or the magnitude of the change of its position per ...

" (about f/14). They projected a sharp and undistorted but dim image onto the plate. Such a lens was necessary in order to produce the highly detailed results which had elicited so much astonishment and praise when daguerreotypes were first exhibited, results which the purchasers of daguerreotype equipment expected to achieve. Using this lens and the original sensitizing method, an exposure of several minutes was required to photograph even a very brightly sunlit scene. A much "faster" lens could have been provided—simply omitting the integral fixed diaphragm

Diaphragm may refer to:

Anatomy

* Thoracic diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle between the thorax and the abdomen

* Pelvic diaphragm or pelvic floor, a pelvic structure

* Urogenital diaphragm or triangular ligament, a pelvic structure

Other

* Diap ...

from the Chevalier lens would have increased its working aperture to about f/4.7 and reduced the exposure time by nearly 90 percent—but because of the existing state of lens design the much shorter exposure would have been at the cost of a peripherally distorted and very much less clear image. With uncommon exceptions, daguerreotypes made before 1841 were of static subjects such as landscapes, buildings, monuments, statuary, and still life

A still life (plural: still lifes) is a work of art depicting mostly wikt:inanimate, inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which are either natural (food, flowers, dead animals, plants, rocks, shells, etc.) or artificiality, m ...

arrangements. Attempts at portrait photography

Portrait photography, or portraiture, is a type of photography aimed toward capturing the personality of a person or group of people by using effective Photographic lighting, lighting, Painted photography backdrops, backdrops, and poses. A portr ...

with the Chevalier lens required the sitter to face into the sun for several minutes while trying to remain motionless and look pleasant, usually producing repulsive and unflattering results. The Woolcott mirror lens that produced tiny, postage stamp size daguerreotypes made portraiture with the daguerreotype process possible and these were the first photographic portraits to be produced. In 1841, the Petzval Portrait Lens was introduced. Professor Andreas von Ettingshausen

Andreas Freiherr von Ettingshausen (25 November 1796 – 25 May 1878) was an Austrian mathematician and physicist.

Biography

Ettingshausen studied philosophy and jurisprudence at the University of Vienna. In 1817, he joined the University of Vi ...

brought the need for a faster lens for daguerreotype cameras to his colleague, Professor Petzval's attention, who went ahead in cooperation with the Voigtländer

Voigtländer () was a significant long-established company within the optics and photographic industry, headquartered in Braunschweig, Germany, and today continues as a trademark for a range of photographic products.

History

Voigtländer was fo ...

firm to design a lens that would reduce the time needed to expose daguerreotype plates for portraiture. Petzval was not aware of the scale of his invention at the start of his work on the lens, and later regretted not having secured his rights by obtaining letters patent on his invention. It was the first lens to be designed using mathematical computation, and a team of mathematicians whose specialty was in fact calculating the trajectories of ballistics was put at Petzval's disposal by the Archduke Ludwig. It was scientifically designed and optimized for its purpose. With a working aperture of about f/3.6, an exposure only about one-fifteenth as long as that required when using a Chevalier lens was sufficient. Although it produced an acceptably sharp image in the central area of the plate, where the sitter's face was likely to be, the image quality dropped off toward the edges, so for this and other reasons it was unsuitable for landscape photography and not a general replacement for Chevalier-type lenses. Petzval intended his lens to be convertible with two alternative rear components: one for portraiture and the other for landscape and architecture.

The other major innovation was a chemical one. In Daguerre's original process, the plate was sensitized by exposure to iodine