Courtly Love on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

an literary conception of love that emphasized nobility and chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours we ...

. Medieval literature is filled with examples of knights setting out on adventures and performing various deeds or services for ladies because of their "courtly love". This kind of love is originally a literary fiction

Literary fiction, mainstream fiction, non-genre fiction or serious fiction is a label that, in the book trade, refers to market novels that do not fit neatly into an established genre (see genre fiction); or, otherwise, refers to novels that are ch ...

created for the entertainment of the nobility, but as time passed, these ideas about love changed and attracted a larger audience. In the high Middle Ages, a "game of love" developed around these ideas as a set of social practices. "Loving nobly" was considered to be an enriching and improving practice.

Courtly love began in the ducal and princely courts of Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 January ...

, Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

, Champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

, ducal Burgundy and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

at the end of the eleventh century. In essence, courtly love was an experience between erotic desire and spiritual attainment, "a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and discipline

Discipline refers to rule following behavior, to regulate, order, control and authority. It may also refer to punishment. Discipline is used to create habits, routines, and automatic mechanisms such as blind obedience. It may be inflicted on ot ...

d, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent". The topic was prominent with both musicians and poets, being frequently used by troubadour

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a ''trobairit ...

s, trouvère

''Trouvère'' (, ), sometimes spelled ''trouveur'' (, ), is the Northern French ('' langue d'oïl'') form of the '' langue d'oc'' (Occitan) word ''trobador'', the precursor of the modern French word ''troubadour''. ''Trouvère'' refers to poet ...

s and minnesänger

(; "love song") was a tradition of lyric- and song-writing in Germany and Austria that flourished in the Middle High German period. This period of medieval German literature began in the 12th century and continued into the 14th. People who wr ...

. The topic was also popular with major writers, including Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

, Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

and Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited w ...

.

The term "courtly love" was first popularized by Gaston Paris

Bruno Paulin Gaston Paris (; 9 August 1839 – 5 March 1903) was a French literary historian, philologist, and scholar specialized in Romance studies and medieval French literature. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901, 19 ...

and has since come under a wide variety of definitions and uses. Its interpretation, origins and influences continue to be a matter of critical debate.

Origin of term

While its origin is uncertain, the term ''amour courtois'' ("courtly love") was given greater popularity byGaston Paris

Bruno Paulin Gaston Paris (; 9 August 1839 – 5 March 1903) was a French literary historian, philologist, and scholar specialized in Romance studies and medieval French literature. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901, 19 ...

in his 1883 article "Études sur les romans de la Table Ronde: Lancelot du Lac, II: ''Le conte de la charrette''", a treatise inspecting Chrétien de Troyes's ''Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart

, original_title_lang = fro

, translator =

, written = between 1177 and 1181

, country =

, language = Old French

, subject = Arthurian legend

, genre = Chivalric romance

, fo ...

'' (1177). Paris said ''amour courtois'' was an idolization and ennobling discipline. The lover (idolizer) accepts the independence of his mistress and tries to make himself worthy of her by acting bravely and honorably (nobly) and by doing whatever deeds she might desire, subjecting himself to a series of tests (ordeals) to prove to her his ardor and commitment. Sexual satisfaction, Paris said, may not have been a goal or even result, but the love was not entirely platonic

Plato's influence on Western culture was so profound that several different concepts are linked by being called Platonic or Platonist, for accepting some assumptions of Platonism, but which do not imply acceptance of that philosophy as a whole. It ...

either, as it was based on sexual attraction

Sexual attraction is attraction on the basis of sexual desire or the quality of arousing such interest. Sexual attractiveness or sex appeal is an individual's ability to attract other people sexually, and is a factor in sexual selection or ma ...

.

The term and Paris's definition were soon widely accepted and adopted. In 1936 C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

wrote ''The Allegory of Love

''The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition'' (1936), by C. S. Lewis (), is an exploration of the allegorical treatment of love in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, which was published on 21 May 1936.D. W. Robertson Jr., in the 1960s and John C. Moore and E. Talbot Donaldson in the 1970s, were critical of the term as being a modern invention, Donaldson calling it "The Myth of Courtly Love", because it is not supported in medieval texts. Even though the term "courtly love" does appear only in just one extant Provençal poem (as ''cortez amors'' in a late 12th-century lyric by

The practice of courtly love developed in the castle life of four regions:

The practice of courtly love developed in the castle life of four regions:

Hispano-Arabic literature, as well as Arabic influence on Sicily, provided a further source, in parallel with Ovid, for the early

Hispano-Arabic literature, as well as Arabic influence on Sicily, provided a further source, in parallel with Ovid, for the early

The vernacular poetry of the ''romans courtois'', or courtly romances, included many examples of courtly love. Some of them are set within the cycle of poems celebrating

The vernacular poetry of the ''romans courtois'', or courtly romances, included many examples of courtly love. Some of them are set within the cycle of poems celebrating

. ''Roman de la Rose'' Digital Library. Accessed 13 November 2012. In it, a man becomes enamored with an individual rose on a rosebush, attempting to pick it and finally succeeding. The rose represents the female body, but the romance also contains lengthy digressive "discussions on free will versus determinism as well as on optics and the influence of heavenly bodies on human behavior".

(Adapted from Barbara W. Tuchman)Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim, ''A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous Fourteenth Century'' (New York: Knopf, 1978). .

* Attraction to the lady, usually via eyes/glance

* Worship of the lady from afar

* Declaration of passionate devotion

* Virtuous rejection by the lady

* Renewed wooing with oaths of virtue and eternal fealty

* Moans of approaching death from unsatisfied desire (and other physical manifestations of

(Adapted from Barbara W. Tuchman)Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim, ''A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous Fourteenth Century'' (New York: Knopf, 1978). .

* Attraction to the lady, usually via eyes/glance

* Worship of the lady from afar

* Declaration of passionate devotion

* Virtuous rejection by the lady

* Renewed wooing with oaths of virtue and eternal fealty

* Moans of approaching death from unsatisfied desire (and other physical manifestations of

Courtly Love

Washington State University. *Andreas Capellanus

"The Art of Courtly Love (btw. 1174–1186)"

extracts via the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

"Courtly love"

In ''

Were Women Ever Sacred? Some Medieval and Modern Men Would Like Us to Think So

" medievalists.net, 14 October 2018 *Emmanuel-Juste Duits

The meaning of Love in the light of the Courtly Love

extract of the French essay "L'Autre désir" {{Authority control Heterosexuality Love Interpersonal relationships European Cultural History pl:Trubadurzy (literatura)#Fin' amors – miłość dworska

Peire d'Alvernhe

Peire d'Alvernhe or d'Alvernha (''Pèire'' in modern Occitan; b. c. 1130) was an Auvergnat troubadour (active 1149–1170) with twenty-oneGaunt and Kay, 287. or twenty-fourEgan, 72.Aubrey, ''The Music of the Troubadours'', 8. surviving works ...

), it is closely related to the term ''fin'amor'' ("fine love") which does appear frequently in Provençal and French, as well as German translated as ''hohe Minne''. In addition, other terms and phrases associated with "courtliness" and "love" are common throughout the Middle Ages. Even though Paris used a term with little support in the contemporaneous literature, it was not a neologism

A neologism Greek νέο- ''néo''(="new") and λόγος /''lógos'' meaning "speech, utterance"] is a relatively recent or isolated term, word, or phrase that may be in the process of entering common use, but that has not been fully accepted int ...

and does usefully describe a particular conception of love and focuses on the courtliness that was at its essence.Roger Boase (1986). "Courtly Love," in ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages

The ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages'' is a 13-volume encyclopedia of the Middle Ages published by the American Council of Learned Societies between 1982 and 1989. It was first conceived and started in 1975 with American medieval historian Jo ...

'', Vol. 3, pp. 667–668.

Richard Trachsler says that "the concept of courtly literature is linked to the idea of the existence of courtly texts, texts produced and read by men and women sharing some kind of elaborate culture they all have in common". He argues that many of the texts that scholars claim to be courtly also include "uncourtly" texts, and argues that there is no clear way to determine "where courtliness ends and uncourtliness starts" because readers would enjoy texts which were supposed to be entirely courtly without realizing they were also enjoying texts which were uncourtly. This presents a clear problem in the understanding of courtliness.Busby, Keith, and Christopher Kleinhenz. Courtly Arts and the Art of Courtliness: Selected Papers from the Eleventh Triennial Congress of the International Courtly Literature Society. Cambridge, MA: D.S. Brewer, 2006. 679-692. Print.

History

The practice of courtly love developed in the castle life of four regions:

The practice of courtly love developed in the castle life of four regions: Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 January ...

, Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

, Champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

and ducal Burgundy, from around the time of the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

(1099). Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II, and Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right from ...

(1124–1204) brought ideals of courtly love from Aquitaine first to the court of France, then to England (she became queen-consort in each of these two realms in succession). Her daughter Marie, Countess of Champagne (1145–1198) brought courtly behavior to the Count of Champagne

The count of Champagne was the ruler of the County of Champagne from 950 to 1316. Champagne evolved from the County of Troyes in the late eleventh century and Hugh I was the first to officially use the title count of Champagne.

Count Theobald ...

's court. Courtly love found expression in the lyric poems written by troubadour

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a ''trobairit ...

s, such as William IX, Duke of Aquitaine

William IX ( oc, Guilhèm de Peitieus; ''Guilhem de Poitou'' french: Guillaume de Poitiers) (22 October 1071 – 10 February 1126), called the Troubadour, was the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and Count of Poitou (as William VII) between 1086 and ...

(1071–1126), one of the first troubadour poets.

Poets adopted the terminology of feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

, declaring themselves the vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. W ...

of the lady and addressing her as ''midons'' (my lord), which had dual benefits: allowing the poet to use a code name (so as to avoid having to reveal the lady's name) and at the same time flattering her by addressing her as his lord. The troubadour's model of the ideal lady was the wife of his employer or lord, a lady of higher status, usually the rich and powerful female head of the castle. When her husband was away on Crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

or elsewhere she dominated the household and cultural affairs; sometimes this was the case even when the husband was at home. The poet gave voice to the aspirations of the courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the official ...

class, for only those who were noble could engage in courtly love. This new kind of love saw nobility not based on wealth and family history, but on character and actions; such as devotion

Devotion or Devotions may refer to:

Religion

* Faith, confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept

* Anglican devotions, private prayers and practices used by Anglican Christians

* Buddhist devotion, commitment to religious observance

* Cat ...

, piety

Piety is a virtue which may include religious devotion or spirituality. A common element in most conceptions of piety is a duty of respect. In a religious context piety may be expressed through pious activities or devotions, which may vary among ...

, gallantry

Gallantry may refer to:

* military courage or bravery

* Chivalry

* Warrior ethos

* Knightly Piety Knightly Piety refers to a specific strand of Christian belief espoused by knights during the Middle Ages. The term comes from ''Ritterfrömmigkei ...

, thus appealing to poorer knights who saw an avenue for advancement.

Since at the time some marriages among nobility had little to do with modern perspectives of what constitutes love, courtly love was also a way for nobles to express the love not found in their marriage. "Lovers" in the context of courtly love need not refer to sex, but rather to the act of loving. These "lovers" had short trysts in secret, which escalated mentally, but might not physically. On the other hand, continual references to beds and sleeping in the lover's arms in medieval sources such as the troubador ''albas'' and romances such as Chrétien's ''Lancelot'' imply at least in some cases a context of actual sexual intercourse.

By the late 12th century Andreas Capellanus' highly influential work '' De amore'' ("Concerning Love") had codified the rules of courtly love. ''De amore'' lists such rules as:

* "Marriage is no real excuse for not loving."

* "He who is not jealous cannot love."

* "No one can be bound by a double love."

* "When made public love rarely endures."

Much of its structure and its sentiments derived from Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's ''Ars amatoria

The ''Ars amatoria'' ( en, The Art of Love) is an instructional elegy series in three books by the ancient Roman poet Ovid. It was written in 2 AD.

Background

Book one of ''Ars amatoria'' was written to show a man how to find a woman. In book tw ...

''.

Andalusian and Islamic influence

Hispano-Arabic literature, as well as Arabic influence on Sicily, provided a further source, in parallel with Ovid, for the early

Hispano-Arabic literature, as well as Arabic influence on Sicily, provided a further source, in parallel with Ovid, for the early troubadours

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a ''trobairi ...

of Provence—overlooked though this sometimes is in accounts of courtly love. The Arabic poets and poetry of Muslim Spain

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mus ...

express similarly oxymoronic views of love as both beneficial and distressing as the troubadours were to do; while the broader European contact with the Islamic world must also be taken into consideration. Given that practices similar to courtly love were already prevalent in Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

and elsewhere in the Islamic world, it is very likely that Islamic practices influenced the Christian Europeans - especially in southern Europe where classical forms of courtly love first emerged.

According to Gustave E. von Grunebaum, several relevant elements developed in Arabic literature

Arabic literature ( ar, الأدب العربي / ALA-LC: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is '' Adab'', which is derived from ...

- including such contrasts as sickness/medicine and delight/torment - to characterise the love experience. The notions of "love for love's sake" and "exaltation of the beloved lady" have been traced back to Arabic literature of the 9th and 10th centuries. The Persian psychologist and philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

Ibn Sina ( 980 – 1037; known as "Avicenna" in Europe) developed the notion of the "ennobling power" of love in the early 11th century in his treatise ''Risala fi'l-Ishq'' ("Treatise on Love"). The final element of courtly love, the concept of "love as desire never to be fulfilled", sometimes occurred implicitly in Arabic poetry, but first developed into a doctrine in European literature

Western literature, also known as European literature, is the literature written in the context of Western culture in the languages of Europe, as well as several geographically or historically related languages such as Basque and Hungarian, an ...

, in which all four elements of courtly love were present.

According to an argument outlined by Maria Rosa Menocal

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

*Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, d ...

in ''The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History'' (1987), in 11th-century Spain, a group of wandering poets appeared who would go from court to court, and sometimes travel to Christian courts in southern France, a situation closely mirroring what would happen in southern France about a century later. Contacts between these Spanish poets and the French troubadours were frequent. The metrical forms used by the Spanish poets resembled those later used by the troubadours.

Analysis

The historic analysis of courtly love varies between different schools of historians. That sort of history which views the early Middle Ages dominated by a prudish and patriarchal theocracy views courtly love as a "humanist" reaction to the puritanical views of the Catholic Church. Scholars who endorse this view value courtly love for its exaltation of femininity as an ennobling, spiritual, and moral force, in contrast to the ironclad chauvinism of the first and second estates. The condemnation of courtly love in the beginning of the 13th century by the church as heretical, is seen by these scholars as the Church's attempt to put down this "sexual rebellion". However, other scholars note that courtly love was certainly tied to the Church's effort to civilize the crude Germanic feudal codes in the late 11th century. It has also been suggested that the prevalence of arranged marriages required other outlets for the expression of more personal occurrences of romantic love, and thus it was not in reaction to the prudery or patriarchy of the Church but to the nuptial customs of the era that courtly love arose.Denis de Rougemont

Denys Louis de Rougemont (September 8, 1906 – December 6, 1985), known as Denis de Rougemont (), was a Swiss writer and cultural theorist who wrote in French. One of the non-conformists of the 1930s, he addressed the perils of totalitarian ...

(1956), ''Love in the Western World''. In the Germanic cultural world a special form of courtly love can be found, namely ''Minne''.

At times, the lady could be a ''princesse lointaine

A princess lointaine or princesse lointaine, (in French, "distant princess") is a stock character of an unattainable loved figure.

The name comes from the play ''La Princesse Lointaine'' by Edmond Rostand (1895), and draws on medieval romances. ...

'', a far-away princess, and some tales told of men who had fallen in love with women whom they had never seen, merely on hearing their perfection described, but normally she was not so distant. As the etiquette

Etiquette () is the set of norms of personal behaviour in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviours that accord with the conventions and norms observed and practised by a ...

of courtly love became more complicated, the knight might wear the colors of his lady: where blue or black were sometimes the colors of faithfulness, green could be a sign of unfaithfulness. Salvation, previously found in the hands of the priesthood, now came from the hands of one's lady. In some cases, there were also women troubadours who expressed the same sentiment for men.

Literary convention

The literary convention of courtly love can be found in most of the major authors of the Middle Ages such asGeoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

, John Gower

John Gower (; c. 1330 – October 1408) was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and the Pearl Poet, and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is remembered primarily for three major works, the '' Mirour de l'Omme'', '' Vo ...

, Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

, Marie de France

Marie de France ( fl. 1160 to 1215) was a poet, possibly born in what is now France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court ...

, Chretien de Troyes, Gottfried von Strassburg

Gottfried von Strassburg (died c. 1210) is the author of the Middle High German courtly romance ', an adaptation of the 12th-century ''Tristan and Iseult'' legend. Gottfried's work is regarded, alongside the ''Nibelungenlied'' and Wolfram von Esc ...

and Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of ''Le Morte d'Ar ...

. The medieval genres

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

in which courtly love conventions can be found include the lyric, the romance

Romance (from Vulgar Latin , "in the Roman language", i.e., "Latin") may refer to:

Common meanings

* Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings

* Romance languages, ...

and the allegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

.

Lyric

Courtly love was born in the lyric, first appearing with Provençal poets in the 11th century, including itinerant and courtlyminstrels

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in Middle Ages, medieval Europe. It originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobatics, acrobat, singer or jester, fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to ...

such as the French troubadours and trouvère

''Trouvère'' (, ), sometimes spelled ''trouveur'' (, ), is the Northern French ('' langue d'oïl'') form of the '' langue d'oc'' (Occitan) word ''trobador'', the precursor of the modern French word ''troubadour''. ''Trouvère'' refers to poet ...

s, as well as the writers of lays. Texts about courtly love, including lays, were often set to music by troubadours or minstrels. According to scholar Ardis Butterfield, courtly love is "the air which many genres of troubadour song breathe". Not much is known about how, when, where, and for whom these pieces were performed, but we can infer that the pieces were performed at court by troubadours, trouvères, or the courtiers themselves. This can be inferred because people at court were encouraged or expected to be "courtly" and be proficient in many different areas, including music. Several troubadours became extremely wealthy playing the fiddle and singing their songs about courtly love for a courtly audience.

It is difficult to know how and when these songs were performed because most of the information on these topics is provided in the music itself. One lay, the "Lay of Lecheor", says that after a lay was composed, "Then the lay was preserved / Until it was known everywhere / For those who were skilled musicians / On viol, harp and rote / Carried it forth from that region…" Scholars have to then decide whether to take this description as truth or fiction.

Period examples of performance practice, of which there are few, show a quiet scene with a household servant performing for the king or lord and a few other people, usually unaccompanied. According to scholar Christopher Page, whether or not a piece was accompanied depended on the availability of instruments and people to accompany—in a courtly setting. For troubadours or minstrels, pieces were often accompanied by fiddle, also called a vielle

The vielle is a European bowed stringed instrument used in the medieval period, similar to a modern violin but with a somewhat longer and deeper body, three to five gut strings, and a leaf-shaped pegbox with frontal tuning pegs, sometimes with a ...

, or a harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

. Courtly musicians also played the vielle and the harp, as well as different types of viol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

s and flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

s.

This French tradition spread later to the German Minnesänger

(; "love song") was a tradition of lyric- and song-writing in Germany and Austria that flourished in the Middle High German period. This period of medieval German literature began in the 12th century and continued into the 14th. People who wr ...

, such as Walther von der Vogelweide

Walther von der Vogelweide (c. 1170c. 1230) was a Minnesänger who composed and performed love-songs and political songs (" Sprüche") in Middle High German. Walther has been described as the greatest German lyrical poet before Goethe; his hundr ...

and Wolfram von Eschenbach

Wolfram von Eschenbach (; – ) was a German knight, poet and composer, regarded as one of the greatest epic poets of medieval German literature. As a Minnesinger, he also wrote lyric poetry.

Life

Little is known of Wolfram's life. There are ...

. It also influenced the Sicilian School

The Sicilian School was a small community of Sicilian and mainland Italian poets gathered around Frederick II, most of them belonging to his imperial court. Headed by Giacomo da Lentini, they produced more than 300 poems of courtly love betwe ...

of Italian vernacular poetry, as well as Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited w ...

and Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

.

Romance

The vernacular poetry of the ''romans courtois'', or courtly romances, included many examples of courtly love. Some of them are set within the cycle of poems celebrating

The vernacular poetry of the ''romans courtois'', or courtly romances, included many examples of courtly love. Some of them are set within the cycle of poems celebrating King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

's court. This was a literature of leisure, directed to a largely female audience for the first time in European history.

Allegory

Allegory is common in the romantic literature of the Middle Ages, and it was often used to interpret what was already written. There is a strong connection between religious imagery and human sexual love in medieval writings. The tradition of medieval allegory began in part with the interpretation of the Song of Songs in the Bible. Some medieval writers thought that the book should be taken literally as an erotic text; others believed that the Song of Songs was a metaphor for the relationship between Christ and the church and that the book could not even exist without that as its metaphorical meaning. Still others claimed that the book was written literally about sex but that this meaning must be "superseded by meanings related to Christ, to the church and to the individual Christian soul". Marie de France's lai "Eliduc

"Eliduc" is a Breton lai by the medieval poet Marie de France. The twelfth and last poem in the collection known as ''The Lais of Marie de France'', it appears in the manuscript Harley 978 at the British Library. Like the other poems in this colle ...

" toys with the idea that human romantic love is a symbol for God's love when two people love each other so fully and completely that they leave each other for God, separating and moving to different religious environments. Furthermore, the main character's first wife leaves her husband and becomes a nun so that he can marry his new lover.

Allegorical treatment of courtly love is also found in the ''Roman de la Rose

''Le Roman de la Rose'' (''The Romance of the Rose'') is a medieval poem written in Old French and presented as an allegorical dream vision. As poetry, ''The Romance of the Rose'' is a notable instance of courtly literature, purporting to prov ...

'' by Guillaume de Lorris

Guillaume de Lorris (c. 1200c. 1240) was a French scholar and poet from Lorris. He was the author of the first section of the ''Roman de la Rose''. Little is known about him, other than that he wrote the earlier section of the poem around 1230, ...

and Jean de Meun

Jean de Meun (or de Meung, ) () was a French author best known for his continuation of the '' Roman de la Rose''.

Life

He was born Jean Clopinel or Jean Chopinel at Meung-sur-Loire. Tradition asserts that he studied at the University of Paris. He ...

.History and Summary of the Text by Lori J. Walters. ''Roman de la Rose'' Digital Library. Accessed 13 November 2012. In it, a man becomes enamored with an individual rose on a rosebush, attempting to pick it and finally succeeding. The rose represents the female body, but the romance also contains lengthy digressive "discussions on free will versus determinism as well as on optics and the influence of heavenly bodies on human behavior".

Later influence

Through such routes as Capellanus's record of the Courts of Love and the later works ofPetrarchism

Philosophy of love is the field of social philosophy and ethics that attempts to explain the nature of love.

Current theories

There are many different theories that attempt to explain what love is, and what function it serves. It would be very ...

(as well as the continuing influence of Ovid), the themes of courtly love were not confined to the medieval, but appear both in serious and comic forms in early modern Europe. Shakespeare's ''Romeo and Juliet,'' for example, shows Romeo attempting to love Rosaline in an almost contrived courtly fashion while Mercutio mocks him for it; and both in his plays and his sonnets the writer can be seen appropriating the conventions of courtly love for his own ends.

Paul Gallico

Paul William Gallico (July 26, 1897 – July 15, 1976) was an American novelist and short story and sports writer.Ivins, Molly,, ''The New York Times'', July 17, 1976. Retrieved Oct. 25, 2020. Many of his works were adapted for motion pictu ...

's 1939 novel ''The Adventures of Hiram Holliday

''The Adventures of Hiram Holliday'' is an American adventure sitcom that aired on NBC from October 3, 1956 to February 27, 1957. Starring Wally Cox in the title role, the series is based on the 1939 novel of the same name by Paul Gallico.

Plot

...

'' depicts a Romantic modern American consciously seeking to model himself on the ideal Medieval knight. Among other things, when finding himself in Austria in the aftermath of the Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

, he saves a Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

princess who is threatened by the Nazis, acts towards her in strict accordance with the maxims of courtly love and finally wins her after fighting a duel with her aristocratic betrothed.

Points of controversy

Sexuality

A point of ongoing controversy about courtly love is to what extent it was sexual. All courtly love was erotic to some degree, and not purely platonic—the troubadours speak of the physical beauty of their ladies and the feelings and desires the ladies arouse in them. However, it is unclear what a poet should do: live a life of perpetual desire channeling his energies to higher ends, or physically consummate. Scholars have seen it both ways.Denis de Rougemont

Denys Louis de Rougemont (September 8, 1906 – December 6, 1985), known as Denis de Rougemont (), was a Swiss writer and cultural theorist who wrote in French. One of the non-conformists of the 1930s, he addressed the perils of totalitarian ...

said that the troubadours were influenced by Cathar

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. Follo ...

doctrines which rejected the pleasures of the flesh and that they were metaphorically addressing the spirit and soul of their ladies. Rougemont also said that courtly love subscribed to the code of chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours we ...

, and therefore a knight's loyalty was always to his King before his mistress. Edmund Reiss claimed it was also a spiritual love, but a love that had more in common with Christian love, or '' caritas''. On the other hand, scholars such as Mosché Lazar claim it was adulterous sexual love with physical possession of the lady the desired end.

Many scholars identify courtly love as the "pure love" described in 1184 by Capellanus in '' De amore libri tres'':

Within the corpus of troubadour poems there is a wide range of attitudes, even across the works of individual poets. Some poems are physically sensual, even bawdily imagining nude embraces, while others are highly spiritual and border on the platonic.Dian Bornstein (1986). "Courtly Love," in ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages

The ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages'' is a 13-volume encyclopedia of the Middle Ages published by the American Council of Learned Societies between 1982 and 1989. It was first conceived and started in 1975 with American medieval historian Jo ...

'', volume 3, pp.668-674.

The lyrical use of the word ''midons,'' borrowed from Guilhem de Poitou, allowed troubadours to address multiple listeners—the lords, men, and women of the court alike. A sort of hermaphroditic code word, or ''senhan,'' scholar Meg Bogin writes, the multiple meanings behind this term allowed a covert form of flattery: "By refusing to disclose his lady's name, the troubadour permitted every woman in the audience, notably the patron's wife, to think that it was she; then, besides making her the object of a secret passion—it was ''always'' covert romance—by making her his lord he flashed her an aggrandized image of herself: she was more than 'just' a woman; she was a man." These points of multiple meaning and ambiguity facilitated a "coquetry of class", allowing the male troubadours to use the images of women as a means to gain social status with other men, but simultaneously, Bogin suggests, voiced deeper longings for the audience: "In this way, the sexual expressed the social and the social the sexual; and in the poetry of courtly love the static hierarchy of feudalism was uprooted and transformed to express a world of motion and transformation."

Real-world practice

A continued point of controversy is whether courtly love was purely literary or was actually practiced in real life. There are no historical records that offer evidence of its presence in reality. Historian John Benton found no documentary evidence in law codes, court cases, chronicles or other historical documents.John F. Benton, "The Evidence for Andreas Capellanus Re-examined Again", in ''Studies in Philology'', 59 (1962); and "The Court of Champagne as a Literary Center", in ''Speculum'', 36(1961). However, the existence of the non-fiction genre ofcourtesy book A courtesy book (also book of manners) was a didactic manual of knowledge for courtiers to handle matters of etiquette, socially acceptable behaviour, and personal morals, with an especial emphasis upon life in a royal court; the genre of courtesy ...

s is perhaps evidence for its practice. For example, according to Christine de Pizan's courtesy book ''Book of the Three Virtues'' (c. 1405), which expresses disapproval of courtly love, the convention was being used to justify and cover up illicit love affairs. Courtly love probably found expression in the real world in customs such as the crowning of Queens of Love and Beauty at tournaments

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

. Philip le Bon, in his '' Feast of the Pheasant'' in 1454, relied on parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, w ...

s drawn from courtly love to incite his nobles to swear to participate in an anticipated crusade, while well into the 15th century numerous actual political and social conventions were largely based on the formulas dictated by the "rules" of courtly love.

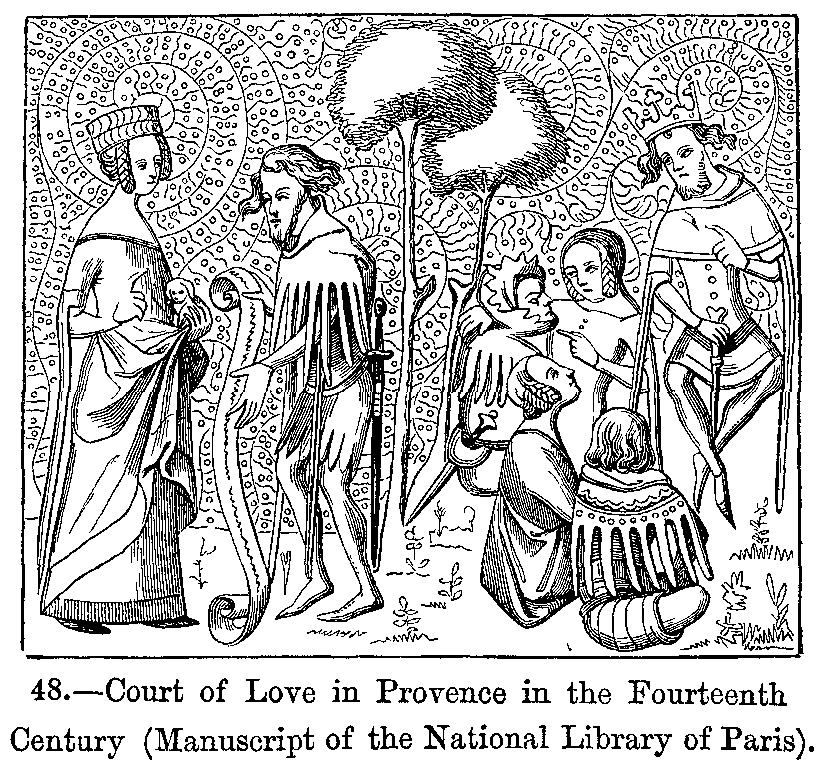

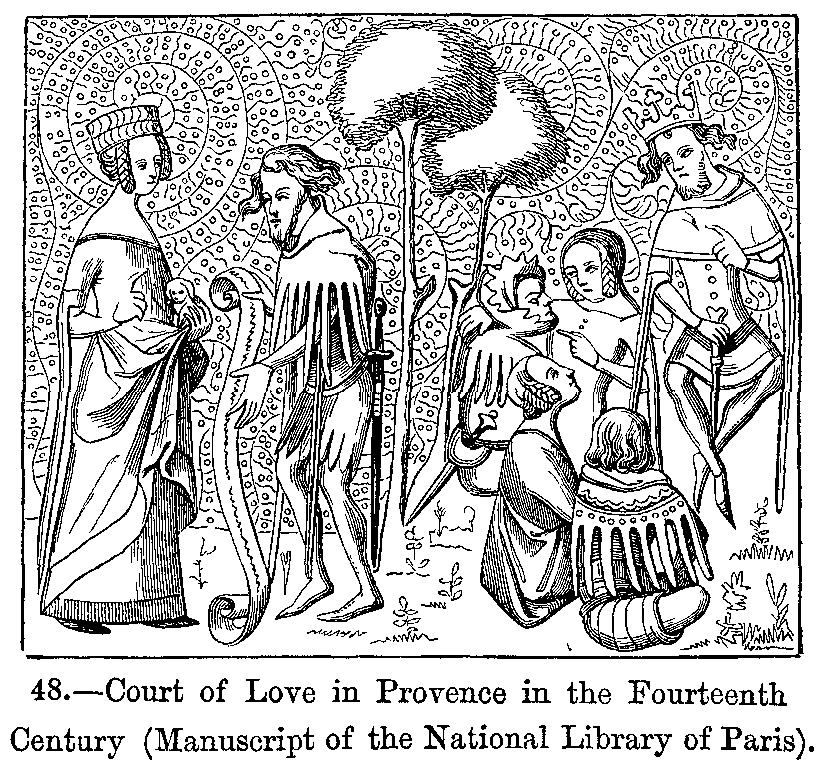

Courts of love

A point of controversy was the existence of "courts of love", first mentioned by Andreas Capellanus. These were supposed courts made up of tribunals staffed by 10 to 70 women who would hear a case of love and rule on it based on the rules of love. In the 19th century, historians took the existence of these courts as fact, but later historians such as Benton noted "none of the abundant letters, chronicles, songs and pious dedications" suggest they ever existed outside of the poetic literature. Likewise,feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

historian Emily James Putnam wrote in 1910 that, secrecy being "among the lover's first duties" in the ideology of courtly love, it is "manifestly absurd to suppose that a sentiment which depended on concealment for its existence should be amenable to public inquiry". According to Diane Bornstein, one way to reconcile the differences between the references to courts of love in the literature, and the lack of documentary evidence in real life, is that they were like literary salons or social gatherings, where people read poems, debated questions of love, and played word games of flirtation.

Courtly love as a response to canon law

The Church emphasized love as more of a spiritual rather than sexual connection. There is a possibility that other writings not associated with the Church over courtly love were made as a response to the Catholic Church's ideas about love. Many scholars believe Andreas Capellanus’ work, ''De arte honeste amandi'', was a satire poking fun at the Church. In that work, Capellanus is supposedly writing to a young man named Walter, and he spends the first two books telling him how to achieve love and the rules of love. However, in the third book he tells him that the only way to live his life correctly is to shun love in favor of God. This sudden change is what has sparked the interest of many scholars.Stages

(Adapted from Barbara W. Tuchman)Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim, ''A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous Fourteenth Century'' (New York: Knopf, 1978). .

* Attraction to the lady, usually via eyes/glance

* Worship of the lady from afar

* Declaration of passionate devotion

* Virtuous rejection by the lady

* Renewed wooing with oaths of virtue and eternal fealty

* Moans of approaching death from unsatisfied desire (and other physical manifestations of

(Adapted from Barbara W. Tuchman)Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim, ''A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous Fourteenth Century'' (New York: Knopf, 1978). .

* Attraction to the lady, usually via eyes/glance

* Worship of the lady from afar

* Declaration of passionate devotion

* Virtuous rejection by the lady

* Renewed wooing with oaths of virtue and eternal fealty

* Moans of approaching death from unsatisfied desire (and other physical manifestations of lovesickness

Lovesickness refers to an affliction that can produce negative feelings when deeply in love, during the absence of a loved one or when love is unrequited.

The term "lovesickness" is rarely used in modern medicine and psychology, though new rese ...

)

* Heroic deeds of valor which win the lady's heart

* Consummation of the secret love

* Endless adventures and subterfuges avoiding detection

See also

*''Cicisbeo

In 18th- and 19th-century Italy, the ''cicisbeo'' ( , , ; plural: ''cicisbei'') or (french: chevalier servant) was the man who was the professed gallant or lover of a woman married to someone else. With the knowledge and consent of the husband, ...

''

*''Domnei

Domnei or donnoi is an Old Provençal term meaning the attitude of chivalrous devotion of a knight to his Lady, which was mainly a non-physical and non-marital relationship.

Principles

This type of relationship was highly ritualized and complex ...

''

*Dulcinea

Dulcinea del Toboso is a fictional character who is unseen in Miguel de Cervantes' novel ''Don Quijote''. Don Quijote believes he must have a lady, under the mistaken view that chivalry requires it.

As he does not have one, he invents her, mak ...

References

Further reading

*Duby, Georges. ''The Knight, the Lady, and the Priest: the Making of Modern Marriage in Medieval France''. Translated byBarbara Bray

Barbara Bray (née Jacobs; 24 November 1924 – 25 February 2010) was an English translator and critic.

Early life

Bray was born in Maida Vale, London; her parents had Belgian and Jewish origins. An identical twin (her sister Olive Classe was al ...

. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983. ().

*Frisardi, Andrew. ''The Young Dante and the One Love: Two Lectures on the Vita Nova''. Temenos Academy, 2013. .

*Gaunt, Simon. "Marginal Men, Marcabru, and Orthodoxy: The Early Troubadours and Adultery". ''Medium Aevum'' 59 (1990): 55–71.

*Lewis, C. S. ''The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition''. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1936. ()

*Lupack, Alan. ''The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend.'' Oxford: University Press, 2005.

*Menocal, Maria Rosa. ''The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003. ()

*Murray, Jacqueline. ''Love, Marriage, and Family in the Middle Ages.'' Canada: Broadview Press Ltd., 2001.

*Newman, Francis X. ''The Meaning of Courtly Love''. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1968. ()

*Capellanus, Andreas. ''The Art of Courtly Love''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1964.

*Schultz, James A. ''Courtly Love, the Love of Courtliness, and the History of Sexuality. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006. ()

*Busby, Keith, and Christopher Kleinhenz. Courtly Arts and the Art of Courtliness: Selected Papers from the Eleventh Triennial Congress of the International Courtly Literature Society. Cambridge, MA: D.S. Brewer, 2006. 679–692.

External links

*Michael DelahoydeCourtly Love

Washington State University. *Andreas Capellanus

"The Art of Courtly Love (btw. 1174–1186)"

extracts via the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

"Courtly love"

In ''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'' Online.

*Richard UtzWere Women Ever Sacred? Some Medieval and Modern Men Would Like Us to Think So

" medievalists.net, 14 October 2018 *Emmanuel-Juste Duits

The meaning of Love in the light of the Courtly Love

extract of the French essay "L'Autre désir" {{Authority control Heterosexuality Love Interpersonal relationships European Cultural History pl:Trubadurzy (literatura)#Fin' amors – miłość dworska