Communist International on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a

The victory of the Russian Communist Party in the

The victory of the Russian Communist Party in the

''Report on the Unity Congress of the R.S.D.L.P.''

/ref> In this period, the Comintern was promoted as the general staff of the

Ahead of the Second Congress of the Communist International, held in July through August 1920, Lenin sent out a number of documents, including his

Ahead of the Second Congress of the Communist International, held in July through August 1920, Lenin sent out a number of documents, including his

Lenin died in 1924 and the next year saw a shift in the organization's focus from the immediate activity of world revolution towards a defence of the Soviet state. In that year, Joseph Stalin took power in Moscow and upheld the thesis of

Lenin died in 1924 and the next year saw a shift in the organization's focus from the immediate activity of world revolution towards a defence of the Soviet state. In that year, Joseph Stalin took power in Moscow and upheld the thesis of

Marxism and Philosophy

'. Zinoviev himself was dismissed in 1926 after falling out of favor with Stalin. Bukharin then led the Comintern for two years until 1928, when he too fell out with Stalin. Bulgarian communist leader Georgi Dimitrov headed the Comintern in 1934 and presided until its dissolution. Geoff Eley summed up the change in attitude at this time as follows:

online

* Belogurova, Anna. ''The Nanyang Revolution: The Comintern and Chinese Networks in Southeast Asia, 1890–1957'' (Cambridge UP, 2019). focus on Malaya * Caballero, Manuel. ''Latin America and the Comintern, 1919-1943'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002) * Carr, E.H. '' Twilight of the Comintern, 1930–1935.'' New York: Pantheon Books, 1982

online free to borrow

* Chase, William J. ''Enemies within the Gates? The Comintern and the Stalinist Repression, 1934–1939.'' (Yale UP, 2001). * Dobronravin, Nikolay. "The Comintern, 'Negro Self-Determination' and Black Revolutions in the Caribbean." ''Interfaces Brasil/Canadá'' 20 (2020): 1-18

online

* Drachkovitch, M. M. ed. ''The Revolutionary Internationals'' (Stanford UP, 1966). * Drachewych, Oleksa. "The Comintern and the Communist Parties of South Africa, Canada, and Australia on Questions of Imperialism, Nationality and Race, 1919-1943" (PhD dissertation, McMaster University, 2017

online

* Dullin, Sabine, and Brigitte Studer. "Communism+ transnational: the rediscovered equation of internationalism in the Comintern years." ''Twentieth Century Communism'' 14.14 (2018): 66–95. * Gankin, Olga Hess and Harold Henry Fisher. ''The Bolsheviks and the World War: The Origin of the Third International.'' (Stanford UP, 1940

online

* Gupta, Sobhanlal Datta. ''Comintern and the Destiny of Communism in India: 1919-1943'' (2006

online

* Haithcox, John Patrick. ''Communism and nationalism in India: MN Roy and Comintern policy, 1920–1939'' (1971)

online

* Hallas, Duncan. ''The Comintern: The History of the Third International.'' London: Bookmarks, 1985. *

online

* Jeifets, Víctor, and Lazar Jeifets. "The Encounter between the Cuban Left and the Russian Revolution: The Communist Party and the Comintern." ''Historia Crítica'' 64 (2017): 81-100. * Kennan, George F. ''Russia and the West Under Lenin and Stalin'' (1961) pp. 151–93

online

* Lazitch, Branko and Milorad M. Drachkovitch. ''Biographical dictionary of the Comintern'' (2nd ed. 1986). * McDermott, Kevin. "Stalin and the Comintern during the 'Third Period', 1928-33." ''European history quarterly'' 25.3 (1995): 409-429. * McDermott, Kevin. "The History of the Comintern in Light of New Documents," in Tim Rees and Andrew Thorpe (eds.), ''International Communism and the Communist International, 1919–43.'' Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1998. * McDermott, Kevin, and J. Agnew. ''The Comintern: a History of International Communism from Lenin to Stalin.'' Basingstoke, 1996. * Melograni, Piero. ''Lenin and the Myth of World Revolution: Ideology and Reasons of State 1917–1920'', Humanities Press, 1990. * Priestland, David. ''The Red Flag: A History of Communism.'' 2010. * Riddell, John. "The Comintern in 1922: The Periphery Pushes Back." ''Historical Materialism'' 22.3–4 (2014): 52–103.

online

* Smith, S. A. (ed.) ''The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism'' (2014), ch 10:

The Comintern

. * Taber, Mike (ed.), ''The Communist Movement at a Crossroads: Plenums of the Communist International's Executive Committee, 1922–1923.'' John Riddell, trans. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019. * Ulam, Adam B. ''Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–1973.'' (2nd ed. Praeger Publishers, 1974)

online

* Valeva, Yelena. ''The CPSU, the Comintern, and the Bulgarians'' (Routledge, 2018). * Worley, Matthew et al. (eds.) ''Bolshevism, Stalinism and the Comintern: Perspectives on Stalinization, 1917–53.'' (2008). * ''The Comintern and its Critics'' (Special issue of ''Revolutionary History'' Volume 8, no 1, Summer 2001).

online

* Redfern, Neil. "The Comintern and Imperialism: A Balance Sheet." ''Journal of Labor and Society'' 20.1 (2017): 43-60.

online vol 1 1919–22vol 2 1923–28vol 3 1929-43

(PDF). * Firsov, Fridrikh I., Harvey Klehr, and John Earl Haynes, eds. ''Secret Cables of the Comintern, 1933–1943.'' New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014

online review

* Gruber, Helmut. ''International Communism in the Era of Lenin: A Documentary History'' (Cornell University Press, 1967) * Kheng, Cheah Boon, ed. ''From PKI to the Comintern, 1924–1941'' (Cornell University Press, 2018). on China * Riddell, John (ed.): ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time, Vol. 1: Lenin's Struggle for a Revolutionary International: Documents: 1907–1916: The Preparatory Years.'' New York: Monad Press, 1984. ** Riddell, John (ed.): ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time, Vol. 2: The German Revolution and the Debate on Soviet Power: Documents: 1918–1919: Preparing the Founding Congress.'' New York: Pathfinder Press, 1986. ** Riddell, John (ed.) ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time, Vol. 3: Founding the Communist International: Proceedings and Documents of the First Congress: March 1919.'' New York: Pathfinder Press, 1987. ** Riddell, John (ed.) ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time: Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples Unite! Proceedings and Documents of the Second Congress, 1920.'' In Two Volumes. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991. ** Riddell, John (ed.) ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time: To See the Dawn: Baku, 1920: First Congress of the Peoples of the East.'' New York: Pathfinder Press, 1993. ** Riddell, John (ed.) ''Toward the United Front: Proceedings of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, 1922.'' Lieden, NL: Brill, 2012.

Marxists Internet Archive * Lenin's speech: The Third, Communist International ()

Site Comintern Archives

*

Site Comintern Archives

*

Program of the Communist International. Together With Its Constitution

' (adopted at 6th World Congress in 1928)

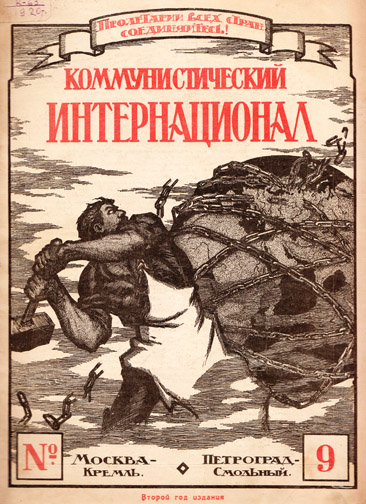

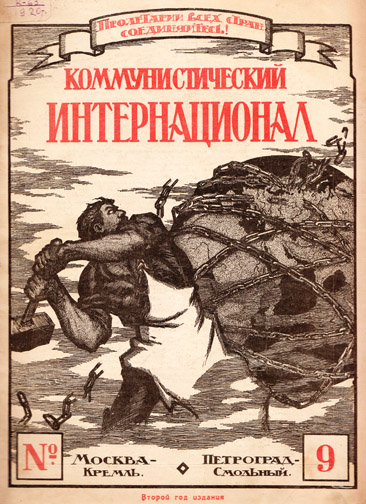

Journal of the Comintern, Marxists Internet Archive

''Outline History of the Communist International''

''The Internationale''

by R. Palme Dutt, 1964

Report from Moscow, 3rd International congress, 1920

by

Article on the Third International from the Encyclopædia Britannica

{{Authority control Communist organizations History of socialism Left-wing internationals Far-left politics Foreign relations of the Soviet Union Political internationals Stalinist organizations Stalinism Defunct international non-governmental organizations Politics of the Soviet Union 1919 establishments in Russia 1943 disestablishments in the Soviet Union Organizations established in 1919 Organizations disestablished in 1943 International Socialist Organisations

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

-controlled international organization

An international organization or international organisation (see spelling differences), also known as an intergovernmental organization or an international institution, is a stable set of norms and rules meant to govern the behavior of states a ...

founded in 1919 that advocated world communism

World communism, also known as global communism, is the ultimate form of communism which of necessity has a universal or global scope. The long-term goal of world communism is an unlimited worldwide communist society that is classless (lacking ...

. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the state". The Comintern was preceded by the 1916 dissolution of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

.

The Comintern held seven World Congresses in Moscow between 1919 and 1935. During that period, it also conducted thirteen Enlarged Plenums of its governing Executive Committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

, which had much the same function as the somewhat larger and more grandiose Congresses. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, leader of the Soviet Union, dissolved the Comintern in 1943 to avoid antagonizing his allies in the later years of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the United States and the United Kingdom. It was succeeded by the Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist-Leninist communist parties in Europe during the early Cold War that was formed in part as a replacement of the ...

in 1947.

Organizational history

Failure of the Second International

Differences between the revolutionary andreformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can ...

wings of the workers' movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

had been increasing for decades, but the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was the catalyst for their separation. The Triple Alliance comprised two empires, while the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

was formed by three. Socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

had historically been anti-war and internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

, fighting against what they perceived as militarist exploitation of the proletariat for bourgeois states. A majority of socialists voted in favor of resolutions for the Second International to call upon the international working class to resist war if it were declared.

But after the beginning of World War I, many European socialist parties announced support for the war effort of their respective nations. Exceptions were the British Labour Party and the socialist parties of the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. To Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

's surprise, even the Social Democratic Party of Germany voted in favor of war. After influential anti-war French Socialist

The Socialist Party (french: Parti socialiste , PS) is a French centre-left and social-democratic political party. It holds pro-European views.

The PS was for decades the largest party of the "French Left" and used to be one of the two major p ...

Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

was assassinated on 31 July 1914, the socialist parties hardened their support in France for their government of national unity

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other nati ...

.

Socialist parties in neutral countries mostly supported neutrality, rather than totally opposing the war. On the other hand, during the 1915 Zimmerwald Conference

The Zimmerwald Conference was held in Zimmerwald, Switzerland, from September 5 to 8, 1915. It was the first of three international socialist conferences convened by anti-militarist socialist parties from countries that were originally neutral ...

, Lenin, then a Swiss resident refugee, organized an opposition to the "imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

war" as the Zimmerwald Left

The Zimmerwald Conference was held in Zimmerwald, Switzerland, from September 5 to 8, 1915. It was the first of three international socialist conferences convened by anti-militarist socialist parties from countries that were originally neutral ...

, publishing the pamphlet ''Socialism and War'' where he called socialists collaborating with their national governments social chauvinists, i.e. socialists in word, but nationalists in deed.

The Second International divided into a revolutionary left-wing, a moderate center-wing, and a more reformist right-wing. Lenin condemned much of the center as "social pacifists" for several reasons, including their vote for war credits despite publicly opposing the war. Lenin's term "social pacifist" aimed in particular at Ramsay MacDonald, leader of the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

in Britain, who opposed the war on grounds of pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

but did not actively fight against it.

Discredited by its apathy towards world events, the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

dissolved in 1916. In 1917, after the February Revolution overthrew the Romanov Dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

, Lenin published the ''April Theses

The April Theses (russian: апрельские тезисы, transliteration: ') were a series of ten directives issued by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin upon his April 1917 return to Petrograd from his exile in Switzerland via Germany ...

'' which openly supported revolutionary defeatism

Revolutionary defeatism is a concept made most prominent by Vladimir Lenin in World War I. It is based on the Marxist idea of class struggle. Arguing that the proletariat could not win or gain in a capitalist war, Lenin declared its true enemy is ...

, where the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

hoped that Russia would lose the war so that they could quickly cause a socialist insurrection.

Impact of the Russian Revolution

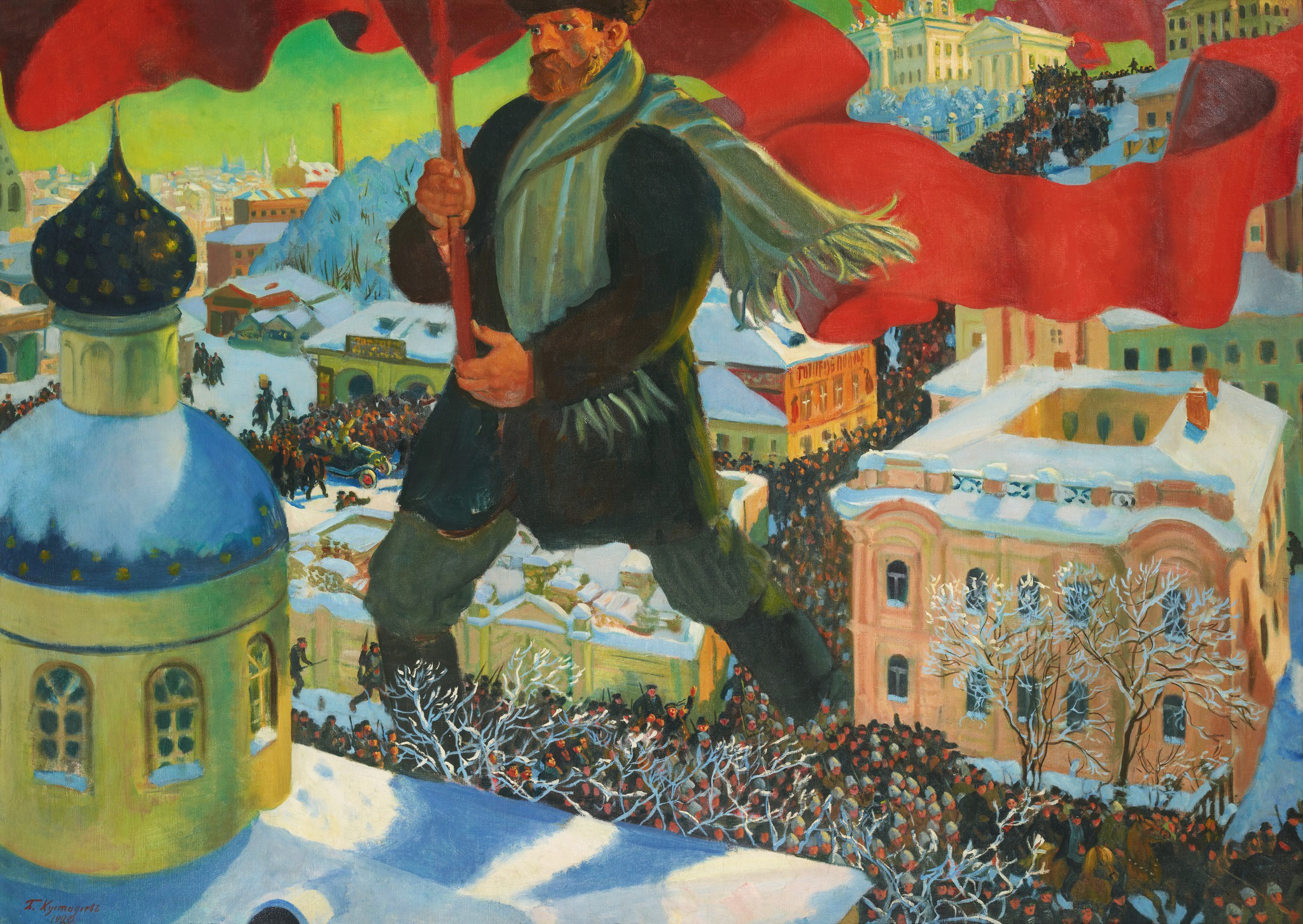

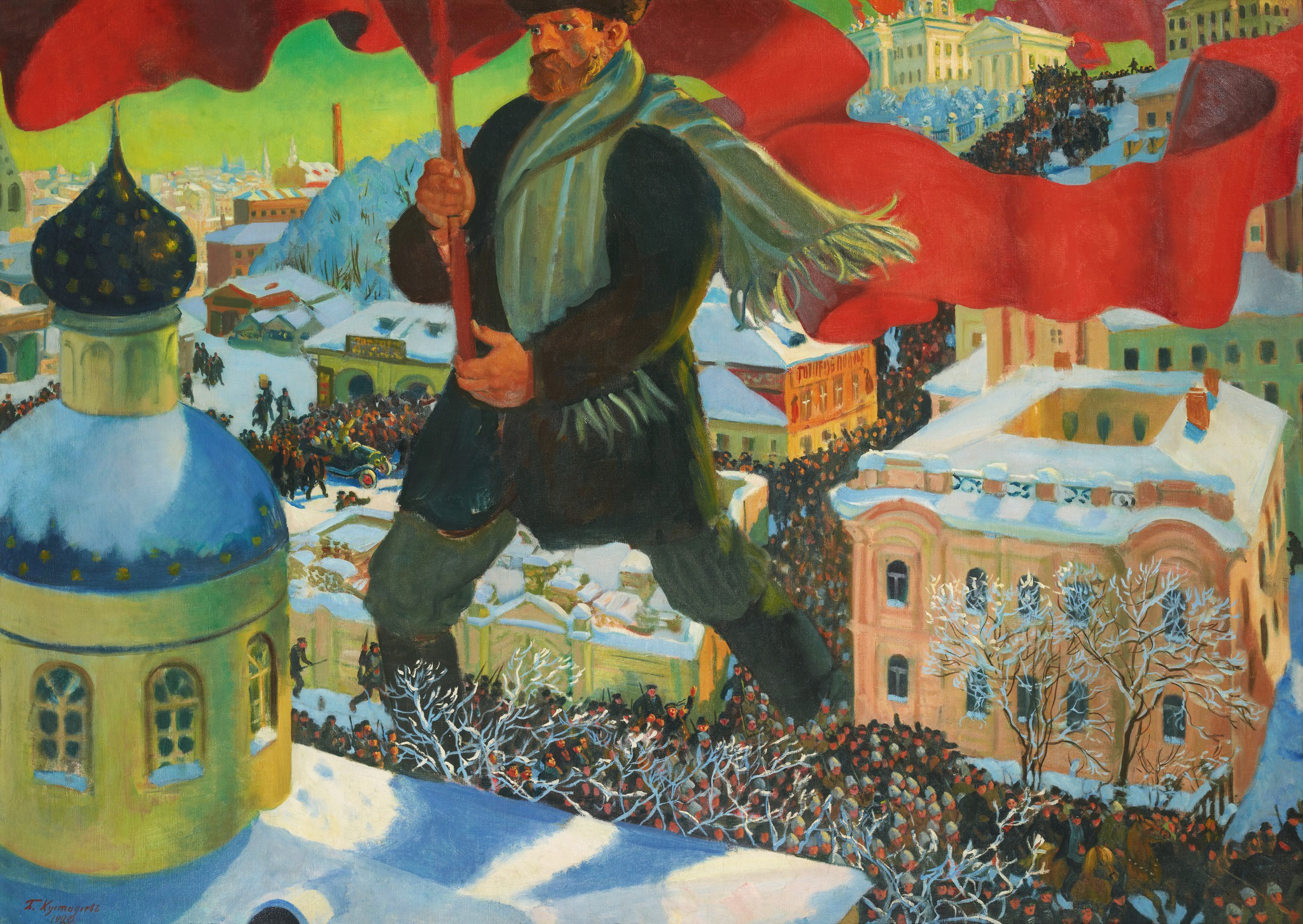

The victory of the Russian Communist Party in the

The victory of the Russian Communist Party in the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

of November 1917 was felt throughout the world and an alternative path to power to parliamentary politics was demonstrated. With much of Europe on the verge of economic and political collapse in the aftermath of the carnage of World War I, revolutionary sentiments were widespread. The Russian Bolsheviks headed by Lenin believed that unless socialist revolution swept Europe, they would be crushed by the military might of world capitalism just as the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

had been crushed by force of arms in 1871. The Bolsheviks believed that this required a new international to foment revolution in Europe and around the world.

First Period of the Comintern

During this early period (1919–1924), known as the First Period in Comintern history, with the Bolshevik Revolution under attack in theRussian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

and a wave of revolutions across Europe, the Comintern's priority was exporting the October Revolution. Some communist parties had secret military wings. One example is the M-Apparat of the Communist Party of Germany. Its purpose was to prepare for the civil war the communists believed was impending in Germany and to liquidate opponents and informers who might have infiltrated the party. There was also a paramilitary organization called the Rotfrontkämpferbund.

The Comintern was involved in the revolutions across Europe in this period, starting with the Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

in 1919. Several hundred agitators and financial aid were sent from the Soviet Union and Lenin was in regular contact with its leader Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napo ...

. Soon, an official Terror Group of the Revolutionary Council of the Government was formed, unofficially known as Lenin Boys. The next attempt was the March Action

The March Action (German "März Aktion" or "Märzkämpfe in Mitteldeutschland," i.e. "The March battles in Central Germany") was a 1921 failed Communist uprising, led by the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), the Communist Workers' Party of Germa ...

in Germany in 1921, including an attempt to dynamite the express train from Halle to Leipzig. After this failed, the Communist Party of Germany expelled its former chairman Paul Levi

Paul Levi (11 March 1883 – 9 February 1930) was a German communist and social democratic political leader. He was the head of the Communist Party of Germany following the assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in 1919. After being ...

from the party for publicly criticising the March Action in a pamphlet, which was ratified by the Executive Committee of the Communist International prior to the Third Congress. A new attempt was made at the time of the Ruhr crisis in spring and then again in selected parts of Germany in the autumn of 1923. The Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

was mobilized, ready to come to the aid of the planned insurrection. Resolute action by the German government cancelled the plans, except due to miscommunication in Hamburg, where 200–300 communists attacked police stations, but were quickly defeated. In 1924, there was a failed coup in Estonia by the Communist Party of Estonia

The Communist Party of Estonia ( et, Eestimaa Kommunistlik Partei, abbreviated EKP) was a subdivision of the Soviet communist party which in 1920-1940 operated illegally in Estonia and, after the 1940 occupation and annexation of Estonia by the ...

.

Founding Congress

The Comintern was founded at a Congress held inMoscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

on 2–6 March 1919. It opened with a tribute to Karl Liebknecht

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht (; 13 August 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a German socialist and anti-militarist. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) beginning in 1900, he was one of its deputies in the Reichstag fro ...

and Rosa Luxemburg, recently murdered by the Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

during the Spartakus Uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising (), was a general strike and the accompanying armed struggles that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revoluti ...

, against the backdrop of the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

. There were 52 delegates present from 34 parties. They decided to form an Executive Committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

with representatives of the most important sections and that other parties joining the International would have their own representatives. The Congress decided that the Executive Committee would elect a five-member bureau to run the daily affairs of the International. However, such a bureau was not formed and Lenin, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

and Christian Rakovsky later delegated the task of managing the International to Grigory Zinoviev as the Chairman of the Executive. Zinoviev was assisted by Angelica Balabanoff

, image = Brodskiy II Balabanova.jpg

, birth_name = Anzhelika Isaakovna Balabanova

, birth_date = August 4, 1878

, birth_place = Chernihiv, Ukraine

, death_date =

, death_place = Rome, Ital ...

, acting as the secretary of the International, Victor L. Kibaltchitch and Vladmir Ossipovich Mazin. Lenin, Trotsky and Alexandra Kollontai

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (russian: Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й, née Domontovich, Домонто́вич; – 9 March 1952) was a Russian revolutionary, politician, diplomat and Marxist the ...

presented material. The main topic of discussion was the difference between bourgeois democracy and the dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

.

The following parties and movements were invited to the Founding Congress:

* Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

)

* Spartacus League (later became the Communist Party of Germany)

* Communist Party of German Austria

* Hungarian Communist Workers' Party

The Hungarian Workers' Party ( hu, Magyar Munkáspárt) is a communist party in Hungary led by Gyula Thürmer. Established after the fall of the communist Hungarian People's Republic, the party has yet to win a seat in the Hungarian parliament ...

(in power during Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napo ...

's Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

)

* Communist Party of Finland

The Communist Party of Finland ( fi, Suomen Kommunistinen Puolue, SKP; sv, Finlands Kommunistiska Parti) was a communist political party in Finland. The SKP was a section of Comintern and illegal in Finland until 1944.

The SKP was banned ...

* Polish Communist Workers’ Party

* Communist Party of Estonia

The Communist Party of Estonia ( et, Eestimaa Kommunistlik Partei, abbreviated EKP) was a subdivision of the Soviet communist party which in 1920-1940 operated illegally in Estonia and, after the 1940 occupation and annexation of Estonia by the ...

* Communist Party of Latvia

The Communist Party of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Komunistiskā partija, LKP) was a political party in Latvia.

History Latvian Social-Democracy prior to 1919

The party was founded at a congress in June 1904. Initially the party was known as the Latvia ...

* Communist Party of Lithuania

The Communist Party of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos komunistų partija; russian: Коммунистическая партия Литвы) is a banned communist party in Lithuania. The party was established in early October 1918 and operated clan ...

* Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Byelorussia

* Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine ( uk, Комуністична Партія України ''Komunistychna Partiya Ukrayiny'', КПУ, ''KPU''; russian: Коммунистическая партия Украины) was the founding and ruling ...

(Ukrainian section of Russian Communist Party)

* The revolutionary elements of the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party

The Czech Social Democratic Party ( cs, Česká strana sociálně demokratická, ČSSD, ) is a social-democratic political party in the Czech Republic. Sitting on the centre-left of the political spectrum and holding pro-European views, it is a ...

(who founded the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Comint ...

)

* Social Democratic and Labour Party of Bulgaria (''Tesnyatsi'')

* Left-wing of the Socialist Party of Romania

The Socialist Party of Romania ( ro, Partidul Socialist din România, commonly known as ''Partidul Socialist'', PS) was a Romanian socialist political party, created on December 11, 1918 by members of the Social Democratic Party of Romania (PSDR) ...

(who would create the Romanian Communist Party)

* Left-wing of the Serbian Social Democratic Party (later formed the League of Communists of Yugoslavia)

* Social Democratic Left Party of Sweden

* Norwegian Labour Party

* For Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, the Klassekampen group

* Communist Party of the Netherlands

The Communist Party of the Netherlands ( nl, Communistische Partij Nederland, , CPN) was a Dutch communist party. The party was founded in 1909 as the Social-Democratic Party (SDP) and merged with the Pacifist Socialist Party, the Political Part ...

* Revolutionary elements of the Belgian Labour Party

The Belgian Labour Party ( nl, Belgische Werkliedenpartij, BWP; french: Parti ouvrier belge, POB) was the first major socialist party in Belgium. Founded in 1885, the party was officially disbanded in 1940 and superseded by the Belgian Socialist ...

(who would create the Communist Party of Belgium

french: Parti Communiste de Belgique

, abbreviation = KPB-PCB

, colorcode =

, leader1_title = Historical leaders

, leader1_name = Joseph JacquemotteJulien LahautLouis Van Geyt

, founder = Julien Lahaut

, founded =

, dissolved =

, merge ...

in 1921)

* Groups and organizations within the French socialist

The Socialist Party (french: Parti socialiste , PS) is a French centre-left and social-democratic political party. It holds pro-European views.

The PS was for decades the largest party of the "French Left" and used to be one of the two major p ...

and syndicalist movements

* Left-wing within the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland

The Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei der Schweiz; SP; rm, Partida Socialdemocrata da la Svizra) or Swiss Socialist Party (french: Parti socialiste suisse, it, Partito Socialista Svizzero; PS), is a polit ...

(later formed the Communist Party of Switzerland

The Communist Party of Switzerland (german: Kommunistische Partei der Schweiz; KPS) or Swiss Communist Party (french: Parti communiste suisse; it, Partito Comunista Svizzero; PCS) was a communist party in Switzerland between 1921 and 1944. It was ...

)

* Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Socialism, socialist and later Social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Italy, political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the l ...

* Revolutionary elements of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gove ...

(formed the Spanish Communist Party

The Spanish Communist Party (in es, Partido Comunista Español), was the first communist party in Spain, formed out of the Federación de Juventudes Socialistas (Federation of Socialist Youth, youth wing of Spanish Socialist Workers' Party). Th ...

and the Spanish Communist Workers' Party)

* Revolutionary elements of the Portuguese Socialist Party

The Portuguese Socialist Party ( pt, Partido Socialista Português) was a political party in Portugal.

The party was founded in 1875. During its initial phase the party was heavily influenced by Proudhonism, and rejected revolutionary Marxism. T ...

(formed the Portuguese Maximalist Federation

The Portuguese Maximalist Federation ( or ) was a revolutionary movement founded on April 27, 1919 in Lisbon. The organization was inspired by the most radical factions involved in the Russian revolution of 1917, and was mostly composed by anar ...

)

* British socialist parties (particularly the current represented by John Maclean)

* Socialist Labour Party (United Kingdom)

* Revolutionary elements of the workers' organizations of Ireland

* Revolutionary elements among the Shop stewards

A union representative, union steward, or shop steward is an employee of an organization or company who represents and defends the interests of their fellow employees as a labor union member and official. Rank-and-file members of the union hold ...

(United Kingdom)

* Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

(United States)

* Left elements of the Socialist Party of America (the tendency represented by the Socialist Propaganda League of America

The Socialist Propaganda League of America (SPLA) was established in 1915, apparently by C. W. Fitzgerald of Beverly, Massachusetts. The group was a membership organization established within the ranks of the Socialist Party of America (SPA) and ...

, later formed the Communist Party USA)

* Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(international trade union based in the United States)

* Workers' International Industrial Union

The Workers' International Industrial Union (WIIU) was a Revolutionary Industrial Union headquartered in Detroit in 1908 by radical trade unionists closely associated with the Socialist Labor Party of America, headed by Daniel DeLeon. The organiz ...

(United States)

* The Socialist groups of Tokyo and Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

(Japan, represented by Sen Katayama

Sen may refer to:

Surname

* Sen (surname), a Bengali surname

* Şen, a Turkish surname

* A variant of the Serer patronym Sène

Currency subunit

* Etymologically related to the English word ''cent''; a hundredth of the following currencies:

* ...

)

* Socialist Youth International

Socialist Youth International (in German: ''Sozialistische Jugend-Internationale'', French: ''L'Internationale de la Jeunesse Socialiste'') was an international union of socialist youth organisations. It was founded in Hamburg 1923, through the me ...

(represented by Willi Münzenberg

Wilhelm "Willi" Münzenberg (14 August 1889, Erfurt, Germany – June 1940, Saint-Marcellin, France) was a German Communist political activist and publisher. Münzenberg was the first head of the Young Communist International in 1919–20 and est ...

)

Of these, the following attended (see list of delegates of the 1st Comintern congress

This is a list of delegates of the 1st World Congress of the Communist International. The founding congress that established the Communist International was held in Moscow from 2 March 1919 to 6 March 1919.

Full delegates Russian Communist Party ...

): the communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

of Russia, Germany, German Austria, Hungary, Poland, Finland, Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania, Byelorussia, Estonia, Armenia, the Volga German region; the Swedish Social Democratic Left Party (the opposition), Balkan Revolutionary People's of Russia; Zimmerwald Left Wing of France; the Czech, Bulgarian, Yugoslav, British, French and Swiss Communist Groups; the Dutch Social-Democratic Group; Socialist Propaganda League and the Socialist Labor Party of America; Socialist Workers' Party of China; Korean Workers' Union, Turkestan, Turkish, Georgian, Azerbaijanian and Persian Sections of the Central Bureau of the Eastern People's and the Zimmerwald Commission.

Zinoviev served as the first Chairman of the Comintern's Executive Committee from 1919 to 1926, but its dominant figure until his death in January 1924 was Lenin, whose strategy for revolution had been laid out in ''What Is to Be Done?

''What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement'' is a political pamphlet written by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin (credited as N. Lenin) in 1901 and published in 1902. Lenin said that the article represented "a skeleton plan t ...

'' (1902). The central policy of the Comintern under Lenin's leadership was that communist parties should be established across the world to aid the international proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialists, ...

. The parties also shared his principle of democratic centralism (freedom of discussion, unity of action), namely that parties would make decisions democratically, but uphold in a disciplined fashion whatever decision was made.Lenin, V. (1906)''Report on the Unity Congress of the R.S.D.L.P.''

/ref> In this period, the Comintern was promoted as the general staff of the

world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

.

Second World Congress

Twenty-one Conditions The Twenty-one Conditions, officially the Conditions of Admission to the Communist International, refer to the conditions, most of which were suggested by Vladimir Lenin, to the adhesion of the socialist parties to the Third International (Comintern ...

to all socialist parties. Congress adopted the 21 conditions as prerequisites for any group wanting to become affiliated with the International. The 21 Conditions called for the demarcation between communist parties and other socialist groups and instructed the Comintern sections not to trust the legality of the bourgeois states. They also called for the build-up of party organisations along democratic centralist lines in which the party press and parliamentary factions would be under the direct control of the party leadership.

Regarding the political situation in the colonized world, the Second Congress of the Communist International stipulated that a united front should be formed between the proletariat, peasantry, and national bourgeoisie in the colonial countries. Amongst the twenty-one conditions drafted by Lenin ahead of the congress was the 11th thesis which stipulated that all communist parties must support the bourgeois-democratic liberation movements in the colonies. Notably, some of the delegates opposed the idea of an alliance with the bourgeoisie and preferred giving support to communist movements in these countries instead. Their criticism was shared by the Indian revolutionary M. N. Roy

Manabendra Nath Roy (born Narendra Nath Bhattacharya, better known as M. N. Roy; 21 March 1887 – 25 January 1954) was an Indian revolutionary, radical activist and political theorist, as well as a noted philosopher in the 20th century. Roy ...

, who attended as a delegate of the Mexican Communist Party

The Mexican Communist Party ( es, Partido Comunista Mexicano, PCM) was a communist party in Mexico. It was founded in 1917 as the Socialist Workers' Party (, PSO) by Manabendra Nath Roy, a left-wing Indian revolutionary. The PSO changed its name ...

. The Congress removed the term bourgeois-democratic in what became the 8th condition.

Many European socialist parties were divided because of the adhesion issue. The French Section of the Workers International

The French Section of the Workers' International (french: Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO) was a political party in France that was founded in 1905 and succeeded in 1969 by the modern-day Socialist Party. The SFIO was foun ...

(SFIO) thus broke away with the 1920 Tours Congress

The Tours Congress was the 18th National Congress of the French Section of the Workers' International, or SFIO, which took place in Tours on 25–30 December 1920. During the Congress, the majority voted to join the Third International and create ...

, leading to the creation of the new French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Un ...

(initially called French Section of the Communist International – SFIC). The Communist Party of Spain

The Communist Party of Spain ( es, Partido Comunista de España; PCE) is a Marxist-Leninist party that, since 1986, has been part of the United Left coalition, which is part of Unidas Podemos. It currently has two of its politicians serving a ...

was created in 1920, the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). ...

was created in 1921, the Belgian Communist Party

french: Parti Communiste de Belgique

, abbreviation = KPB-PCB

, colorcode =

, leader1_title = Historical leaders

, leader1_name = Joseph JacquemotteJulien LahautLouis Van Geyt

, founder = Julien Lahaut

, founded =

, dissolved =

, merge ...

in September 1921, and so on.

Third World Congress

The Third Congress of the Communist International was held between 22 June–12 July 1921 in Moscow.Fourth World Congress

The Fourth Congress, held in November 1922, at which Trotsky played a prominent role, continued in this vein. In 1924, the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party joined the Comintern. At first, in China both theChinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

and the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

were supported. After the definite break with Chiang Kai-shek in 1927, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

sent personal emissaries to help organize revolts which at this time failed.

The Fourth World Congress was coincidentally held within days of the March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, ...

by Benito Mussolini and his PNF in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. Karl Radek lamented the proceedings in Italy as the "largest defeat suffered by socialism and communism since the beginning of the period of world revolution", and Zinoviev programmatically announced the similarities between fascism and social democracy, laying the groundwork for the later ''social fascism

Social fascism (also socio-fascism) was a theory that was supported by the Communist International (Comintern) and affiliated communist parties in the early 1930s that held that social democracy was a variant of fascism because it stood in the way ...

'' theory.

Fifth to Seventh World Congresses: 1925–1935

Second Period

Lenin died in 1924 and the next year saw a shift in the organization's focus from the immediate activity of world revolution towards a defence of the Soviet state. In that year, Joseph Stalin took power in Moscow and upheld the thesis of

Lenin died in 1924 and the next year saw a shift in the organization's focus from the immediate activity of world revolution towards a defence of the Soviet state. In that year, Joseph Stalin took power in Moscow and upheld the thesis of socialism in one country

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin encouraged th ...

, detailed by Nikolai Bukharin in his brochure ''Can We Build Socialism in One Country in the Absence of the Victory of the West-European Proletariat?'' (April 1925). The position was finalized as the state policy after Stalin's January 1926 article ''On the Issues of Leninism''. Stalin made the party line clear: "An internationalist is one who is ready to defend the USSR without reservation, without wavering, unconditionally; for the USSR it is the base of the world revolutionary movement, and this revolutionary movement cannot be defended and promoted without defending the USSR".

The dream of a world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

was abandoned after the failures of the Spartacist uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising (), was a general strike and the accompanying armed struggles that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revolutio ...

in Germany and of the Hungarian Soviet Republic and the failure of all revolutionary movements in Europe such as in Italy, where the fascist ''squadristi

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Natio ...

'' broke the strikes during the Biennio Rosso

The Biennio Rosso (English: "Red Biennium" or "Two Red Years") was a two-year period, between 1919 and 1920, of intense social conflict in Italy, following the First World War.Brunella Dalla Casa, ''Composizione di classe, rivendicazioni e prof ...

and quickly assumed power following the 1922 March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, ...

. This period up to 1928 was known as the Second Period, mirroring the shift in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

from war communism

War communism or military communism (russian: Военный коммунизм, ''Voyennyy kommunizm'') was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921.

According to Soviet histo ...

to the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

.

At the Fifth World Congress of the Comintern in July 1924, Zinoviev condemned both Marxist philosopher Georg Lukács

Georg may refer to:

* ''Georg'' (film), 1997

* Georg (musical), Estonian musical

* Georg (given name)

* Georg (surname)

* , a Kriegsmarine coastal tanker

See also

* George (disambiguation)

{{disambiguation ...

's ''History and Class Consciousness'', published in 1923 after his involvement in Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napo ...

's Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

, and Karl Korsch's Marxism and Philosophy

'. Zinoviev himself was dismissed in 1926 after falling out of favor with Stalin. Bukharin then led the Comintern for two years until 1928, when he too fell out with Stalin. Bulgarian communist leader Georgi Dimitrov headed the Comintern in 1934 and presided until its dissolution. Geoff Eley summed up the change in attitude at this time as follows:

By the Fifth Comintern Congress in July 1924 ..the collapse of Communist support in Europe tightened the pressure for conformity. A new policy of "Bolshevization" was adopted, which dragooned the CPs toward stricter bureaucratic centralism. This flattened out the earlier diversity of radicalisms, welding them into a single approved model of Communist organization. Only then did the new parties retreat from broader Left arenas into their own belligerent world, even if many local cultures of broader cooperation persisted. Respect for Bolshevik achievements and defense of the Russian Revolution now transmuted into dependency on Moscow and belief in Soviet infallibility. Depressing cycles of "internal rectification" began, disgracing and expelling successive leaderships, so that by the later 1920s many founding Communists had gone. This process of coordination, in a hard-faced drive for uniformity, was finalized at the next Congress of the Third International in 1928.The Comintern was a relatively small organization, but it devised novel ways of controlling communist parties around the world. In many places, there was a communist subculture, founded upon indigenous left-wing traditions which had never been controlled by Moscow. The Comintern attempted to establish control over party leaderships by sending agents who bolstered certain factions, by judicious use of secret funding, by expelling independent-minded activists and even by closing down entire national parties (such as the

Communist Party of Poland

The interwar Communist Party of Poland ( pl, Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP) was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland a ...

in 1938). Above all, the Comintern exploited Soviet prestige in sharp contrast to the weaknesses of local parties that rarely had political power.David Priestland, ''The Red Flag: A History of Communism'' (2009) pp. 124–125

Communist front organizations

Communist front

A communist front is a political organization identified as a front organization under the effective control of a communist party, the Communist International or other communist organizations. They attracted politicized individuals who were not p ...

organizations were set up to attract non-members who agreed with the party on certain specific points. Opposition to fascism

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were ...

was a common theme in the popular front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

era of the mid 1930s. The well-known names and prestige of artists, intellectuals and other fellow travelers were used to advance party positions. They often came to the Soviet Union for propaganda tours praising the future. Under the leadership of Zinoviev, the Comintern established fronts in many countries in the 1920s and after. To coordinate their activities, the Comintern set up international umbrella organizations linking groups across national borders, such as the Young Communist International

The Young Communist International was the parallel international youth organization affiliated with the Communist International (Comintern).

History

International socialist youth organization before World War I

After failed efforts to form an i ...

(youth), Profintern

The Red International of Labor Unions (russian: Красный интернационал профсоюзов, translit=Krasnyi internatsional profsoyuzov, RILU), commonly known as the Profintern, was an international body established by the Comm ...

(trade unions), Krestintern

The Peasant International (russian: Крестьянский Интернационал), known most commonly by its Russian abbreviation Krestintern (Крестинтерн), was an international peasants' organization formed by the Communist ...

(peasants), International Red Aid

International Red Aid (also commonly known by its Russian acronym MOPR ( ru , МОПР, for: ''Междунаро́дная организа́ция по́мощи борца́м револю́ции'' - Mezhdunarodnaya organizatsiya pomoshchi bor ...

(humanitarian aid), Sportintern (organized sports), and more. Front organizations were especially influential in France, which in 1933 became the base for communist front organizer Willi Münzenberg

Wilhelm "Willi" Münzenberg (14 August 1889, Erfurt, Germany – June 1940, Saint-Marcellin, France) was a German Communist political activist and publisher. Münzenberg was the first head of the Young Communist International in 1919–20 and est ...

. These organizations were dissolved in the late 1930s or early 1940s.

Third Period

In 1928, the Ninth Plenum of the Executive Committee began the so-calledThird Period

The Third Period is an ideological concept adopted by the Communist International (Comintern) at its Sixth World Congress, held in Moscow in the summer of 1928. It set policy until reversed when the Nazis took over Germany in 1933.

The Comint ...

, which was to last until 1935. The Comintern proclaimed that the capitalist system was entering the period of final collapse and therefore all communist parties were to adopt an aggressive and militant ultra-left

The term ultra-leftism, when used among Marxist groups, is a pejorative for certain types of positions on the far-left that are extreme or uncompromising. Another definition historically refers to a particular current of Marxist communism, where ...

line. In particular, the Comintern labelled all moderate left-wing parties social fascists

Social fascism (also socio-fascism) was a theory that was supported by the Communist International (Comintern) and affiliated communist parties in the early 1930s that held that social democracy was a variant of fascism because it stood in the way ...

and urged the communists to destroy the moderate left. With the rise of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

in Germany after the 1930 federal election, this stance became controversial.

The Sixth World Congress also revised the policy of united front in the colonial world. In 1927 in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

had turned on the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

, which led to a review of the policy on forming alliances with the national bourgeoisie in the colonial countries. The Congress did make a differentiation between the character of the Chinese Kuomintang on one hand and the Indian Swaraj Party and the Egyptian Wafd Party

The Wafd Party (; ar, حزب الوفد, ''Ḥizb al-Wafd'') was a nationalist liberal political party in Egypt. It was said to be Egypt's most popular and influential political party for a period from the end of World War I through the 1930 ...

on the other, considering the latter as an unreliable ally yet not a direct enemy. The Congress called on the Indian Communists

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asi ...

to utilize the contradictions between the national bourgeoisie and the British imperialists.

Seventh World Congress and the Popular Front

The Seventh and last Congress of the Comintern was held between 25 July and 20 August 1935. It was attended by representatives of 65 communist parties. The main report was delivered by Dimitrov, other reports were delivered byPalmiro Togliatti

Palmiro Michele Nicola Togliatti (; 26 March 1893 – 21 August 1964) was an Italian politician and leader of the Italian Communist Party from 1927 until his death. He was nicknamed ("The Best") by his supporters. In 1930 he became a citizen of ...

, Wilhelm Pieck

Friedrich Wilhelm Reinhold Pieck (; 3 January 1876 – 7 September 1960) was a German communist politician who served as the chairman of the Socialist Unity Party from 1946 to 1950 and as president of the German Democratic Republic from 1949 to ...

, and Dmitry Manuilsky

Dmitriy Manuilsky, or Dmytro Zakharovych Manuilsky ( Russian: Дми́трий Заха́рович Мануи́льский; Ukrainian: Дмитро Захарович Мануїльський; October 1883 in Sviatets near Kremenets – 22 ...

. The Congress officially endorsed the popular front against fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. This policy argued that communist parties should seek to form a popular front with all parties that opposed fascism and not limit themselves to forming a united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

with those parties based in the working class. There was no significant opposition to this policy within any of the national sections of the Comintern. In France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, it would have momentous consequences with Léon Blum's 1936 election which led to the Popular Front government

The Popular Front ( es, Frente Popular) in Spain's Second Republic was an electoral alliance and pact signed in January 1936 by various left-wing political organizations, instigated by Manuel Azaña for the purpose of contesting that year's el ...

.

Stalin's purges of the 1930s affected Comintern activists living in both the Soviet Union and overseas. At Stalin's direction, the Comintern was thoroughly infused with Soviet secret police and foreign intelligence operatives and informers working under Comintern guise. One of its leaders, Mikhail Trilisser, using the pseudonym Mikhail Aleksandrovich Moskvin, was in fact chief of the foreign department of the Soviet OGPU (later the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

). Numerous Comintern officials were also targeted by the dictator and became victims of show trials and political persecution, such as Grigory Zinoviev and Nikolai Bukharin. At Stalin's orders, 133 out of 492 Comintern staff members became victims of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

. Several hundred German communists and antifascists who had either fled from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

or were convinced to relocate in the Soviet Union were liquidated, and more than a thousand were handed over to Germany. Wolfgang Leonhard

Wolfgang Leonhard (16 April 1921 – 17 August 2014) was a German political author and historian of the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic and Communism. A German Communist whose family had fled Hitler's Germany and who was educated i ...

, who experienced this period in Moscow as a contemporary witness, wrote about it in his political autobiography, which was published in the 1950s: “The foreign communists living in the Soviet Union were particularly affected. In a few months, more functionaries of the Comintern apparatus were arrested than had been put together by all bourgeois governments in twenty years. Just listing the names would fill entire pages.” Fritz Platten

Fritz Platten (8 July 1883 – 22 April 1942) was a Swiss communist politician and one of the founders of the Communist International.

Early life

Platten was born in the village of Tablat, now part of St. Gallen, on 8 July 1883, to and Old Cathol ...

died in a labor camp and the leaders of the Indian (Virendranath Chattopadhyaya

Virendranath Chattopadhyaya ( bn, বীরেন্দ্রনাথ চট্টোপাধ্যায়), alias Chatto, (31 October 1880 – 2 September 1937, Moscow), also known by his pseudonym Chatto, was a prominent Indian revolutiona ...

or Chatto), Korean, Mexican, Iranian, and Turkish communist parties were executed. Out of 11 Mongolian Communist Party leaders, only Khorloogiin Choibalsan

Khorloogiin Choibalsan ( mn, Хорлоогийн Чойбалсан, spelled ''Koroloogiin Çoibalsan'' before 1941; 8 February 1895 – 26 January 1952) was the leader of Mongolia (Mongolian People's Republic) and Marshal (general chief com ...

survived. Leopold Trepper

Leopold Zakharovich Trepper (23 February 1904 – 10 January 1982) was a Polish Communist and career Soviet agent of the Red Army Intelligence. With the code name Otto'','' Trepper had worked with the Red Army since 1930. He was also a resistance ...

recalled these days: "In house, where the party activists of all the countries were living, no-one slept until 3 o'clock in the morning. ..Exactly 3 o'clock the car lights began to be seen ..we stayed near the window and waited o find out where the car stopped".

Among those persecuted were many KPD

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West German ...

functionaries, such as members of the KPD Central Committee, who believed they had found safe asylum in the Soviet Union after Adolf Hitler's rise to power. Among them was Hugo Eberlein

Max Albert Hugo Eberlein (4 May 1887 – 16 October 1941) was a German Communist politician. He took part of the founding congress of the Communist Party of Germany (Dec–Jan 1919), and then in the First Congress of the Comintern (2–6 March 19 ...

, who had been present at the 1919 Comintern founding congress.

Trotsky, who was also marginalized and persecuted by Stalin, and other communists founded the Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) is a revolutionary socialist international organization consisting of followers of Leon Trotsky, also known as Trotskyists, whose declared goal is the overthrowing of global capitalism and the establishment of ...

in 1938 as an oppositional alternative to the Stalin-dominated Comintern. In the years that followed, however, their sections rarely got beyond the status of the smallest cadre or splinter parties.

Although the General Association of German Anti-Communist Associations had existed in Berlin since 1933 as part of the Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

's propaganda against the Soviet Union and the Comintern, a treaty of assistance was concluded between Germany and Japan in 1936, the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

. In it, the two states agreed to fight the Comintern and assured each other that they would not sign any treaties with the Soviet Union that would contradict the anti-communist spirit of the agreement. However, this did not prevent Hitler from signing the Nazi-Soviet pact with Stalin in August 1939, which in turn meant the end of the Popular Front policy and, in fact, that of the Comintern as well.

Dissolution

The German-Soviet non-aggression treaty contained far-reaching agreements onspheres of interest

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

, which the two totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

powers implemented over the next two years using military means. On 3 September 1939, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany after its invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

, beginning World War II in Europe

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

. The Comintern sections now found themselves in the politically suicidal situation of having to support, for example, the Soviet invasion and subsequent annexation of Eastern Poland. The Soviet Foreign Minister

The Ministry of External Relations (MER) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (russian: Министерство иностранных дел СССР) was founded on 6 July 1923. It had three names during its existence: People's Co ...

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

declared on October 31 that it was not Hitler's Germany but rather Britain and France that were to be regarded as the aggressors. The weakened and decimated Comintern was forced to officially adopt a policy of non-intervention

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is a political philosophy or national foreign policy doctrine that opposes interference in the domestic politics and affairs of other countries but, in contrast to isolationism, is not necessarily opposed t ...

, declaring on November 6 that the conflict was an imperialist war between various national ruling classes on both sides, much like World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

had been, and that the main culprits were Britain and France.

This period, during which the Comintern enabled Hitlerite fascism, only ended on 22 June 1941 with the invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, when the Comintern changed its position to one of active support for the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

. During these two years, many communists turned their backs on their Comintern sections, and the organization lost its political credibility and relevance. On 15 May 1943, a declaration of the Executive Committee was sent out to all sections of the International, calling for the dissolution of the Comintern. The declaration read: The historical role of the Communist International, organized in 1919 as a result of the political collapse of the overwhelming majority of the old pre-war workers' parties, consisted in that it preserved the teachings of Marxism from vulgarisation and distortion by opportunist elements of the labor movement. But long before the war it became increasingly clear that, to the extent that the internal as well as the international situation of individual countries became more complicated, the solution of the problems of the labor movement of each individual country through the medium of some international centre would meet with insuperable obstacles.Concretely, the declaration asked the member sections to approve:

To dissolve the Communist International as a guiding centre of the international labor movement, releasing sections of the Communist International from the obligations ensuing from the constitution and decisions of the Congresses of the Communist International.After endorsements of the declaration were received from the member sections, the International was dissolved. The dissolution was interpreted as Stalin wishing to calm his

World War II allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

(particularly Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

) and to keep them from suspecting the Soviet Union of pursuing a policy of trying to foment revolution in other countries.

Successor organizations

The Research Institutes 100 and 205 worked for the International and later were moved to the International Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, founded at roughly the same time that the Comintern was abolished in 1943, although its specific duties during the first several years of its existence are unknown. Following the June 1947 Paris Conference onMarshall Aid

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

, Stalin gathered a grouping of key European communist parties in September and set up the Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist-Leninist communist parties in Europe during the early Cold War that was formed in part as a replacement of the ...