Cyrus McCormick on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cyrus Hall McCormick (February 15, 1809 – May 13, 1884) was an American inventor and businessman who founded the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, which became part of the International Harvester Company in 1902. Originally from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, he and many members of the McCormick family became prominent residents of Chicago.

McCormick always claimed credit as the single inventor of the mechanical reaper. He was, however, one of several designing engineers who produced working models in the 1830s. His efforts built on more than two decades of work by his father Robert McCormick Jr., with the aid of Jo Anderson, an enslaved African-American man held by the family. He also successfully developed a modern

Cyrus Hall McCormick was born on February 15, 1809, in Raphine, Virginia. He was the eldest of eight children born to inventor Robert McCormick Jr. and Mary Ann "Polly" Hall. As Cyrus's father saw the potential of the design for a mechanical reaper, he applied for a patent to claim it as his own invention. He worked for 28 years on a horse-drawn mechanical reaper to harvest grain, but was never able to produce a reliable version.

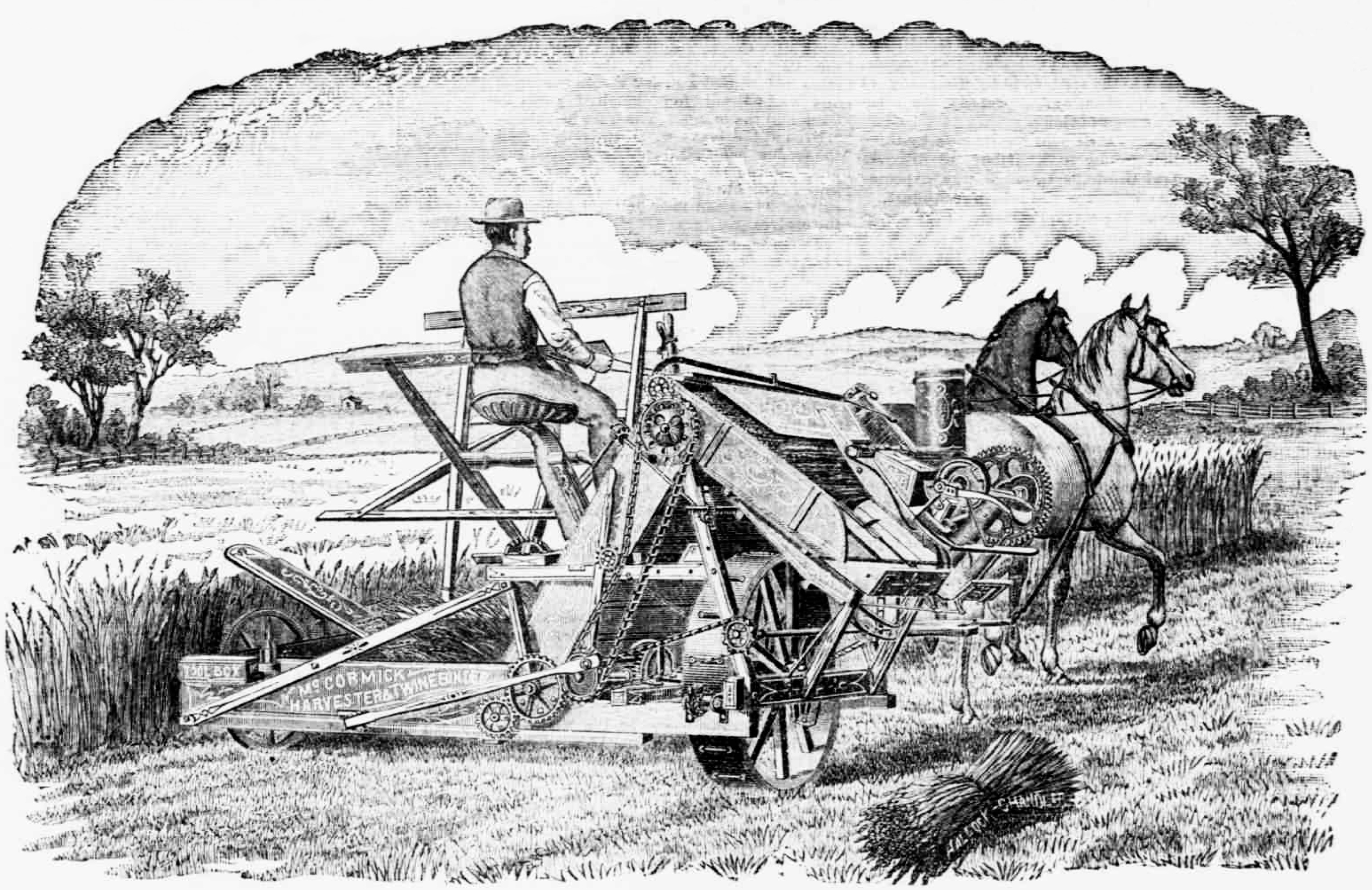

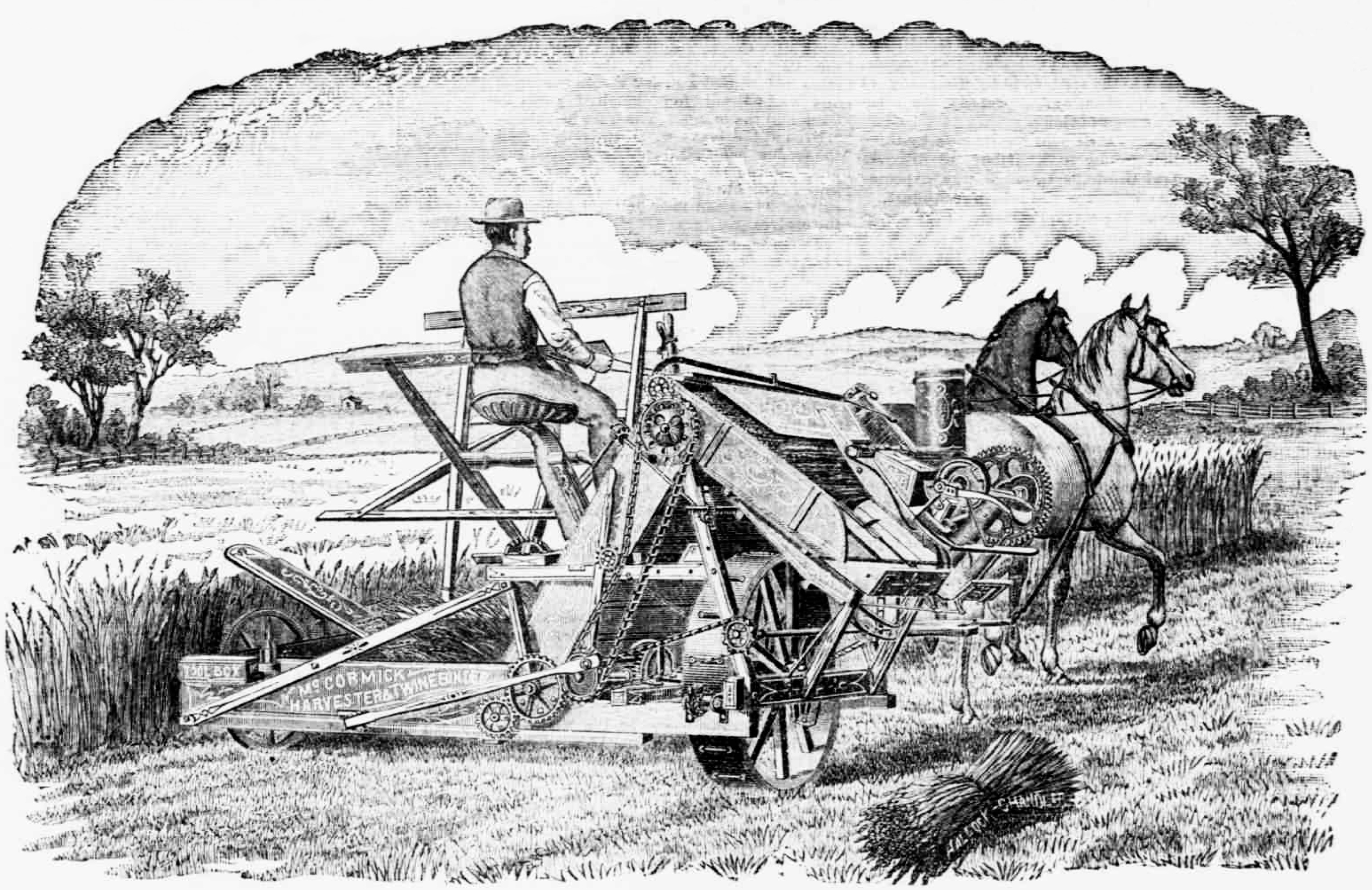

Building on his father's years of development, Cyrus took up the project aided by Jo Anderson, an enslaved African-American man held on the McCormick plantation. A few machines based on a design of Patrick Bell of Scotland (which had not been patented) were available in the United States in these years. The Bell machine was pushed by horses. The McCormick design was pulled by horses and cut the grain to one side of the team.

Cyrus McCormick held one of his first demonstrations of mechanical reaping at the nearby village of Steeles Tavern, Virginia in 1831. He claimed to have developed a final version of the reaper in 18 months. The young McCormick was granted a patent on the reaper on June 21, 1834, two years after having been granted a patent for a self-sharpening plow. None was sold, however, because the machine could not handle varying conditions.

The McCormick family also worked together in a blacksmith/metal smelting business. The

Cyrus Hall McCormick was born on February 15, 1809, in Raphine, Virginia. He was the eldest of eight children born to inventor Robert McCormick Jr. and Mary Ann "Polly" Hall. As Cyrus's father saw the potential of the design for a mechanical reaper, he applied for a patent to claim it as his own invention. He worked for 28 years on a horse-drawn mechanical reaper to harvest grain, but was never able to produce a reliable version.

Building on his father's years of development, Cyrus took up the project aided by Jo Anderson, an enslaved African-American man held on the McCormick plantation. A few machines based on a design of Patrick Bell of Scotland (which had not been patented) were available in the United States in these years. The Bell machine was pushed by horses. The McCormick design was pulled by horses and cut the grain to one side of the team.

Cyrus McCormick held one of his first demonstrations of mechanical reaping at the nearby village of Steeles Tavern, Virginia in 1831. He claimed to have developed a final version of the reaper in 18 months. The young McCormick was granted a patent on the reaper on June 21, 1834, two years after having been granted a patent for a self-sharpening plow. None was sold, however, because the machine could not handle varying conditions.

The McCormick family also worked together in a blacksmith/metal smelting business. The

In 1856, McCormick's factory was producing more than 4,000 reapers each year, mostly sold in the Midwest and West. In 1861, however, Hussey's patent was extended but McCormick's was not. McCormick's outspoken opposition to Lincoln and the anti-slavery Republican party may not have helped his cause. McCormick decided to seek help from the U.S. Congress to protect his patent.

In 1871, the factory burned down in the Great Chicago Fire, but McCormick rebuilt and it reopened in 1873. In 1879, brother Leander changed the company's name from "Cyrus H. McCormick and Brothers" to "McCormick Harvesting Machine Company". To the annoyance of Cyrus, Leander tried to emphasize the contributions of others in the family to the reaper invention, especially their father.

In 1856, McCormick's factory was producing more than 4,000 reapers each year, mostly sold in the Midwest and West. In 1861, however, Hussey's patent was extended but McCormick's was not. McCormick's outspoken opposition to Lincoln and the anti-slavery Republican party may not have helped his cause. McCormick decided to seek help from the U.S. Congress to protect his patent.

In 1871, the factory burned down in the Great Chicago Fire, but McCormick rebuilt and it reopened in 1873. In 1879, brother Leander changed the company's name from "Cyrus H. McCormick and Brothers" to "McCormick Harvesting Machine Company". To the annoyance of Cyrus, Leander tried to emphasize the contributions of others in the family to the reaper invention, especially their father.

online

popular history focused on family ties. * * , for elementary schools.

on Antique Farming web site * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:McCormick, Cyrus 1809 births 1884 deaths 19th-century American inventors 19th-century American journalists 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) American anti-war activists American male journalists American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Presbyterians Burials at Graceland Cemetery (Chicago) Businesspeople from Chicago Illinois Democrats American recipients of the Legion of Honour McCormick family Members of the French Academy of Sciences People from Rockbridge County, Virginia Washington and Lee University trustees

company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether Natural person, natural, Juridical person, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members ...

, with manufacturing

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of the

secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer ...

, marketing

Marketing is the act of acquiring, satisfying and retaining customers. It is one of the primary components of Business administration, business management and commerce.

Marketing is usually conducted by the seller, typically a retailer or ma ...

, and a sales

Sales are activities related to selling or the number of goods sold in a given targeted time period. The delivery of a service for a cost is also considered a sale. A period during which goods are sold for a reduced price may also be referred ...

force to market his products.

Early life and career

panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

almost caused the family to go into bankruptcy when a partner pulled out. In 1839 McCormick started doing more public demonstrations of the reaper, but local farmers still thought the machine was unreliable. He did sell one in 1840, but none for 1841.

Using the endorsement of his father's first customer, Khane Hale, for a machine built by McPhetrich, Cyrus continually attempted to improve the design. He finally sold seven reapers in 1842, 29 in 1843, and 50 in 1844. They were all built manually in the family farm shop. He received a second patent for reaper improvements on January 31, 1845.

As word spread about the reaper, McCormick noticed orders arriving from farther west, where farms tended to be larger and the land flatter. While he was in Washington, D.C. to get his 1845 patent, he heard about a factory in Brockport, New York

Brockport is a village (New York), village in Monroe County, New York, United States. Most of the village is within the town of Sweden, New York, Sweden, with two small portions in the town of Clarkson, New York, Clarkson. The population was 7,1 ...

, where he contracted to have the machines mass-produced. He also licensed several others across the country to build the reaper, but their quality often proved poor, which hurt the product's reputation.

Move to Chicago

In 1847, after their father's death, Cyrus and his brother Leander J. McCormick (1819–1900) moved to Chicago, where they established a factory to build their machines. At the time, other cities in themidwestern United States

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

, such as Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–United States border, Canada–U.S. maritime border ...

; St. Louis, Missouri; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee is the List of cities in Wisconsin, most populous city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Located on the western shore of Lake Michigan, it is the List of United States cities by population, 31st-most populous city in the United States ...

were more established. Chicago had the best water transportation from the east over the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

for his raw materials, as well as railroad connections to the west where most of his customers would be.

When McCormick tried to renew his patent in 1848, the U.S. Patent Office noted that a similar machine had already been patented by Obed Hussey a few months earlier. McCormick claimed he had invented his machine in 1831, but the renewal was denied. William Manning of Plainfield, New Jersey had also received a patent for his reaper in May 1831, but at the time, Manning was evidently not defending his patent.

McCormick's brother William Sanderson McCormick (1815–1865) moved to Chicago in 1849, and joined the company to take care of financial affairs. The McCormick reaper sold well, partially as a result of savvy and innovative business practices. Their products came onto the market just as the explosive expansion of railroads offered inexpensive wide distribution. McCormick developed marketing and sales techniques, forming a wide network of salesmen trained to demonstrate the operation of his machines in the field, as well as to get parts quickly and repair machines in the field if necessary during crucial seasons in the farm year.

A company advertisement was a take-off of the '' Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way'' mural by Emanuel Leutze; it added to the title: "with McCormick Reapers in the Van."

In 1851, McCormick traveled to London to display a reaper at the Crystal Palace Exhibition. After his machine successfully harvested a field of green wheat while the Hussey machine failed, he won a gold medal and was admitted to the Legion of Honor. His celebration was short-lived after he learned that he had lost a court challenge to Hussey's patent.

Legal controversies and success

Another McCormick Company competitor was John Henry Manny ofRockford, Illinois

Rockford is a city in Winnebago County, Illinois, Winnebago and Ogle County, Illinois, Ogle counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. Located in far northern Illinois on the banks of the Rock River (Mississippi River tributary), Rock River, Rockfor ...

. After the Manny Reaper beat the McCormick version at the Paris Exposition of 1855, McCormick filed a lawsuit against Manny for patent infringement. McCormick demanded that Manny stop producing reapers, and pay McCormick $400,000. The trial, originally scheduled for Chicago in September 1855, featured prominent lawyers on both sides. McCormick hired the former U.S. Attorney General Reverdy Johnson and New York patent attorney Edward Nicholl Dickerson. Manny hired George Harding and Edwin Stanton. Because the trial was set to take place in Illinois, Harding hired the local Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

. Manny finally won the case on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1856, McCormick's factory was producing more than 4,000 reapers each year, mostly sold in the Midwest and West. In 1861, however, Hussey's patent was extended but McCormick's was not. McCormick's outspoken opposition to Lincoln and the anti-slavery Republican party may not have helped his cause. McCormick decided to seek help from the U.S. Congress to protect his patent.

In 1871, the factory burned down in the Great Chicago Fire, but McCormick rebuilt and it reopened in 1873. In 1879, brother Leander changed the company's name from "Cyrus H. McCormick and Brothers" to "McCormick Harvesting Machine Company". To the annoyance of Cyrus, Leander tried to emphasize the contributions of others in the family to the reaper invention, especially their father.

In 1856, McCormick's factory was producing more than 4,000 reapers each year, mostly sold in the Midwest and West. In 1861, however, Hussey's patent was extended but McCormick's was not. McCormick's outspoken opposition to Lincoln and the anti-slavery Republican party may not have helped his cause. McCormick decided to seek help from the U.S. Congress to protect his patent.

In 1871, the factory burned down in the Great Chicago Fire, but McCormick rebuilt and it reopened in 1873. In 1879, brother Leander changed the company's name from "Cyrus H. McCormick and Brothers" to "McCormick Harvesting Machine Company". To the annoyance of Cyrus, Leander tried to emphasize the contributions of others in the family to the reaper invention, especially their father.

Family relationships

On January 26, 1858, 49-year-old Cyrus McCormick married Nancy "Nettie" Fowler. She was an orphan from New York who had graduated from the Troy Female Seminary and moved to Chicago. They had met six months earlier and shared views about business, religion and Democratic party politics. They had seven children: # Cyrus Hall McCormick Jr. was born May 16, 1859. # Mary Virginia McCormick was born May 5, 1861. # Robert McCormick III was born October 5, 1863, and died January 6, 1865. # Anita McCormick was born July 4, 1866, married Emmons Blaine on September 26, 1889, and died February 12, 1954. Emmons was a son of the US. Secretary of State James G. Blaine. # Alice McCormick was born March 15, 1870, and died less than a year later on January 25, 1871. # Harold Fowler McCormick was born May 2, 1872, married Edith Rockefeller, and died in 1941. Edith was the youngest daughter of Standard Oil co-founder John Davison Rockefeller and schoolteacher Laura Celestia "Cettie" Spelman. # Stanley Robert McCormick was born November 2, 1874, married Katharine Dexter (1875–1967), and died January 19, 1947. Mary and Stanley both hadschizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, Auditory hallucination#Schizophrenia, hearing voices), delusions, thought disorder, disorganized thinking and behavior, and Reduced affect display, f ...

. Stanley McCormick's life inspired the 1998 novel '' Riven Rock'' by T. Coraghessan Boyle.

Cyrus McCormick was an uncle of Robert Sanderson McCormick (son-in-law of Joseph Medill

Joseph Medill (April 6, 1823 – March 16, 1899) was a Canadian-American newspaper editor, publisher, and Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician. He was co-owner and managing editor of the ''Chicago Tribune'', and he was M ...

); granduncle of Joseph Medill McCormick and Robert Rutherford McCormick; and great-granduncle of William McCormick Blair Jr.

Activism

McCormick had always been a devoutPresbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

, as well as advocate of Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

unity. He also valued and demonstrated in his life the Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

traits of self-denial, sobriety, thriftiness, efficiency, and morality. He believed feeding the world, made easier by the reaper, was part of his religious mission in life.

A lifelong Democrat, before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, McCormick had published editorials in his newspapers, ''The Chicago Times

The ''Chicago Times'' was a newspaper in Chicago from 1854 to 1895, when it merged with the ''Chicago Herald'', to become the ''Chicago Times-Herald''. The ''Times-Herald'' effectively disappeared in 1901 when it merged with the ''Chicago Recor ...

'' and ''Herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen ...

'', calling for reconciliation between the national sections. His views, however, were unpopular in his adopted home town. Although his invention helped feed Union troops, McCormick believed the Confederacy would not be defeated and he and his wife traveled extensively in Europe during the war. McCormick unsuccessfully ran for Congress as a Democrat for Illinois's 2nd congressional district

Illinois's 2nd congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of Illinois. It stretches south from Chicago's Kenwood community area through portions of the city's South Side and southern suburbs, extending into several m ...

with a peace-now platform in 1864, and was soundly defeated by Republican John Wentworth. He also proposed a peace plan to include a Board of Arbitration. After the war, McCormick helped found the Mississippi Valley Society, with a mission to promote New Orleans and Mississippi ports for European trade. He also supported efforts to annex the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. It shares a Maritime boundary, maritime border with Puerto Rico to the east and ...

as a territory of the United States. Beginning in 1872, McCormick served a four-year term on the Illinois Democratic Party's Central Committee. McCormick later proposed an international mechanism to control food production and distribution.

McCormick also became the principal benefactor and a trustee of what had been the Theological Seminary of the Northwest, which moved to Chicago's Lincoln Park neighborhood in 1859, a year in which he endowed four professorships. The institution was renamed McCormick Theological Seminary in 1886, after his death, although it moved to Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood in 1975 and began sharing facilities with the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago.

In 1869, McCormick donated $10,000 to help Dwight L. Moody

Dwight Lyman Moody (February 5, 1837 – December 22, 1899), also known as D. L. Moody, was an American evangelist and publisher connected with Keswickianism, who founded the Moody Church, Northfield School and Mount Hermon School in Mas ...

start YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organisation based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It has nearly 90,000 staff, some 920,000 volunteers and 12,000 branches w ...

, and his son Cyrus Jr. would become the first chairman of the Moody Bible Institute

Moody Bible Institute (MBI) is a private evangelical Christian Bible college in Chicago, Illinois. It was founded by evangelist and businessman Dwight Lyman Moody in 1886. Historically, MBI has maintained positions that have identified it as ...

.

McCormick and later his widow, Nettie Day McCormick, also donated significant sums to Tusculum College, a Presbyterian institution in Tennessee, as well as to establish churches and Sunday Schools in the South after the war, even though that region was slow to adopt his farm machinery and improved practices. Also, in 1872, McCormick purchased a religious newspaper, the ''Interior'', which he renamed the ''Continent'' and became a leading Presbyterian periodical.

For the last 20 years of his life, McCormick was a benefactor and member of the board of trustees at Washington and Lee University

Washington and Lee University (Washington and Lee or W&L) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lexington, Virginia, United States. Established in 1749 as Augusta Academy, it is among ...

in his native Virginia. His brother Leander also donated funds to build an observatory on Mount Jefferson, operated by the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

and named the McCormick Observatory.

Later life and death

During the last four years of his life, McCormick became an invalid, after a stroke paralyzed his legs; he was unable to walk during his final two years. He died at home in Chicago on May 13, 1884. He was buried in Graceland Cemetery. He was survived by his widow, Nettie, who continued his Christian and charitable activities, within the United States and abroad, between 1890 and her death in 1923, donating $8 million (over $160 million in modern equivalents) to hospitals, disaster and relief agencies, churches, youth activities and educational institutions, and becoming the leading benefactress of Presbyterian Church activities in that era. Official leadership of the company passed to his eldest son Cyrus Hall McCormick Jr., but his grandson Cyrus McCormick III ran the company. Four years later, the company's labor practices (paying workers $9 per week) led to the Haymarket riots. Ultimately Cyrus Jr. teamed with J.P. Morgan to create the International Harvester Corporation in 1902. After Cyrus Hall McCormick Jr., Harold Fowler McCormick ran International Harvester. Various members of the McCormick family continued involvement with the corporation until Brooks McCormick, who died in 2006.Legacy and honors

Numerous prizes and medals were awarded McCormick for his reaper, which reduced human labor on farms while increasing productivity. Thus, it contributed to the industrialization of agriculture as well as migration of labor to cities in numerous wheat-growing countries (36 by McCormick's death). The French government named McCormick an Officier de la Légion d'honneur in 1851, and he was elected a corresponding member of theFrench Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

in 1878 "as having done more for the cause of agriculture than any other living man."

The Wisconsin Historical Society

The Wisconsin Historical Society (officially the State Historical Society of Wisconsin) is simultaneously a state agency and a private membership organization whose purpose is to maintain, promote and spread knowledge relating to the history of ...

holds Cyrus McCormick's papers.

* The Cyrus McCormick Farm, operated by other family members after Cyrus and Leander moved to Chicago, was ultimately donated to Virginia Tech

The Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, commonly referred to as Virginia Tech (VT), is a Public university, public Land-grant college, land-grant research university with its main campus in Blacksburg, Virginia, United States ...

, which operates the core of the property as a free museum, and other sections as an experimental farm. A marker memorializing Cyrus McCormick's contribution to agriculture had been erected near the main house in 1928.

* In 1999, the City of Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

placed a historical marker in honor of McCormick near the site of his home at 675 N. Rush St., between Erie and Huron. His original home at the site was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871; the replacement home was torn down in the 1950s.

* A statue of McCormick was erected on the front campus of Washington and Lee University

Washington and Lee University (Washington and Lee or W&L) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lexington, Virginia, United States. Established in 1749 as Augusta Academy, it is among ...

, at Lexington, Virginia

Lexington is an Independent city (United States)#Virginia, independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 7,320. It is the county seat of Rockbridge County, Virg ...

, by Serbian-American artist John David Brcin.

* The town of McCormick, South Carolina and McCormick County in the state were named for him after he bought a gold mine in the town, formerly known as Dornsville.

* 1975, McCormick was inducted into the Junior Achievement

JA (Junior Achievement) Worldwide is a global non-profit youth organization. It was founded in 1919 by Horace A. Moses, Theodore Vail, and Winthrop M. Crane. JA works with local businesses, schools, and organizations to deliver experiential ...

U.S. Business Hall of Fame.

* 3 cent U.S. postage stamps were issued in 1940 to commemorate Cyrus Hall McCormick. See Famous Americans Series of 1940.See also

* History of agriculture in the United States * McCormick reaper *Reaper

A reaper is a farm implement that reaps (cuts and often also gathers) crops at harvest when they are ripe. Usually the crop involved is a cereal grass, especially wheat. The first documented reaping machines were Gallic reapers that were used ...

References

Further reading

* , for middle schools * ; the standard scholarly biography. ** * * Rosenberg, Chaim M. ''The International Harvester Company: A History of the Founding Families and Their Machines'' (McFarland, 2019)online

popular history focused on family ties. * * , for elementary schools.

Primary sources

* , with long quotes from primary sources.External links

* ''Improvement in Machines for Reaping Small Grain'': Cyrus H. McCormick, June 21, 1834on Antique Farming web site * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:McCormick, Cyrus 1809 births 1884 deaths 19th-century American inventors 19th-century American journalists 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) American anti-war activists American male journalists American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Presbyterians Burials at Graceland Cemetery (Chicago) Businesspeople from Chicago Illinois Democrats American recipients of the Legion of Honour McCormick family Members of the French Academy of Sciences People from Rockbridge County, Virginia Washington and Lee University trustees