Cyfarthfa Ironworks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cyfarthfa Ironworks were major 18th- and 19th-century

The Cyfarthfa Ironworks were major 18th- and 19th-century

Under

Under

The Cyfarthfa Ironworks

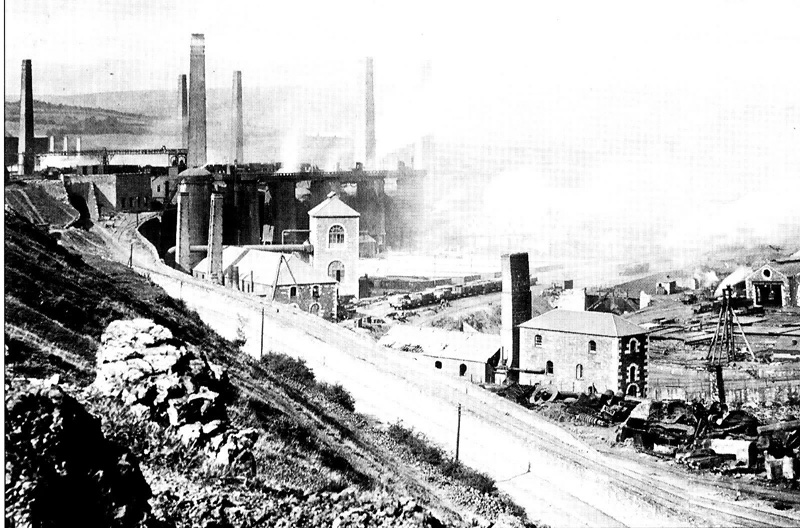

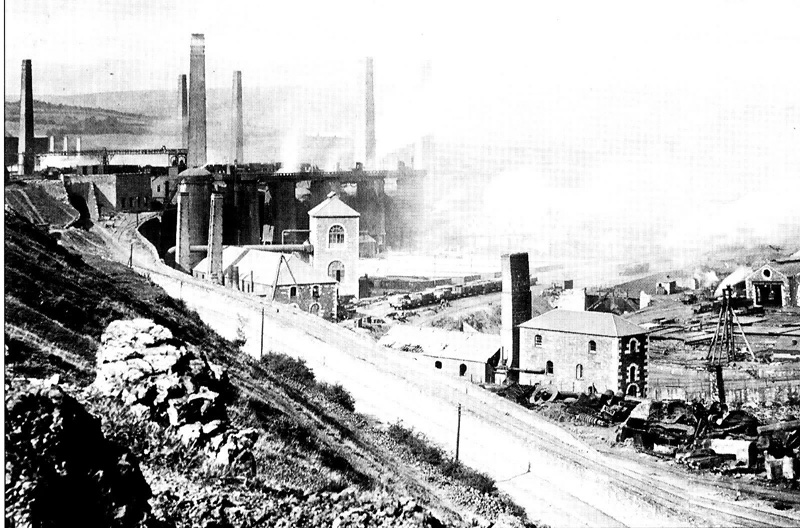

– Historical Photographs of Cyfarthfa Ironworks. {{coord, 51.7526, -3.3941, format=dms, type:landmark, display=title Buildings and structures in Merthyr Tydfil Industrial archaeological sites in Wales Ironworks and steelworks in Wales Industrial buildings completed in 1765

The Cyfarthfa Ironworks were major 18th- and 19th-century

The Cyfarthfa Ironworks were major 18th- and 19th-century ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloomeri ...

in Cyfarthfa

Cyfarthfa is a community and electoral ward in the west of the town of Merthyr Tydfil in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales.

Community

Cyfarthfa mainly consists of the settlements of Gellideg and Heolgerrig and Rhyd-y-car area just west of Mer ...

, on the north-western edge of Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydf ...

, in South West Wales

South West Wales is one of the regions of Wales consisting of the unitary authorities of Swansea, Neath Port Talbot, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire.

This definition is used by a number of government agencies and private organisations including ...

.

The beginning

The Cyfarthfa works were begun in 1765 by Anthony Bacon (by then a merchant in London), who in that year withWilliam Brownrigg

William Brownrigg ( – 6 January 1800) was a British doctor and scientist, who practised at Whitehaven in Cumberland. While there, Brownrigg carried out experiments that earned him the Copley Medal in 1766 for his work on carbonic acid gas. He ...

, a fellow native of Whitehaven

Whitehaven is a town and port on the English north west coast and near to the Lake District National Park in Cumbria, England. Historically in Cumberland, it lies by road south-west of Carlisle and to the north of Barrow-in-Furness. It is th ...

, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, leased the right to mine in a tract of land on the west side of the river Taff

The River Taff ( cy, Afon Taf) is a river in Wales. It rises as two rivers in the Brecon Beacons; the Taf Fechan (''little Taff'') and the Taf Fawr (''great Taff'') before becoming one just north of Merthyr Tydfil. Its confluence with the R ...

at Merthyr Tydfil. They employed Brownrigg's brother-in-law Charles Wood to build a forge there, to use the potting and stamping Potting and stamping is a modern name for one of the 18th-century processes for refining pig iron without the use of charcoal.

Inventors

The process was devised by Charles Wood of Lowmill, Egremont in Cumberland and his brother John Wood of We ...

process, for which he and his brother had a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

. This was powered by water from the river, the race dividing into six to power a clay mill (for making the pots), two stampers, two helve hammers and a chafery

A chafery is a variety of hearth used in ironmaking for reheating a bloom of iron, in the course of its being drawn out into a bar of wrought iron.

The equivalent term for a bloomery was string hearth, except in 17th century Cumbria, where the ...

. The construction of the first coke blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

began in August 1766. This was intended to be 50 feet high with cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

blowing cylinders, rather than the traditional bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtigh ...

. It was probably brought into blast in autumn 1767. In the meantime, Plymouth ironworks

The Plymouth Ironworks was a major 18th century and 19th century ironworks located on land leased from the Earl of Plymouth at Merthyr Tydfil, in South Wales. The metal produced was considered to be the finest in South Wales.

The Ironworks was ...

was leased to provide pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

for the forge.

Brownrigg retired as a partner in 1777, receiving £1500 for his share. From about that time Richard Crawshay

Richard Crawshay (1739 – 27 June 1810) was a London iron merchant and then South Wales ironmaster; he was one of ten known British millionaires in 1799.

Early life and marriage

Richard Crawshay was born in Normanton in the West Riding of ...

was Bacon's partner in his contracts to supply cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

to the Board of Ordnance

The Board of Ordnance was a British government body. Established in the Tudor period, it had its headquarters in the Tower of London. Its primary responsibilities were 'to act as custodian of the lands, depots and forts required for the defence ...

, but perhaps not in the ironworks. Bacon had previously subcontracted cannon-founding

Founding may refer to:

* The formation of a corporation, government, or other organization

* The laying of a building's Foundation

* The casting of materials in a mold

See also

* Foundation (disambiguation)

* Incorporation (disambiguation)

In ...

to John Wilkinson, but henceforth made them at Cyfarthfa, as is indicated by his asking for ships carrying them to be convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

ed from Penarth

Penarth (, ) is a town and Community (Wales), community in the Vale of Glamorgan ( cy, Bro Morgannwg), Wales, exactly south of Cardiff city centre on the west shore of the Severn Estuary at the southern end of Cardiff Bay.

Penarth is a weal ...

. Bacon had the Cyfarthfa Canal, a short tub boat

A tub boat was a type of unpowered cargo boat used on a number of the early English and German canals. The English boats were typically long and wide and generally carried to of cargo, though some extra deep ones could carry up to . They a ...

waterway, constructed during the latter part of the 1770s to bring coal to the ironworks.

In 1782, Bacon (as a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

) had to give up government contracts and passed the forge and boring mill with the gunfounding business to Francis Homfray. However, he gave it up in 1784 to David Tanner, so that his sons could establish the Penydarren Ironworks

Penydarren Ironworks was the fourth of the great ironworks established at Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales.

Built in 1784 by the brothers Samuel Homfray, Jeremiah Homfray, and Thomas Homfray, all sons of Francis Homfray of Stourbridge. Their f ...

. However, David Tanner also did not stay long, giving up the works in 1786, the year of Bacon's death. Tanner's managers were James Cockshutt, Thomas Treharne, and Francis William Bowzer.

Bacon left a family of illegitimate children and was the subject of Chancery proceedings. The court directed a lease of the whole works to Richard Crawshay, who took as his partners, William Stevens (a London merchant) and James Cockshutt. Richard Crawshay took out a licence from Henry Cort

Henry Cort (c. 1740 – 23 May 1800) was an English ironware producer although formerly a Navy pay agent. During the Industrial Revolution in England, Cort began refining iron from pig iron to wrought iron (or bar iron) using innovative producti ...

for the use of his puddling process, and proceeded to build the necessary rolling mill

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

. However, difficulties remained with the puddling process and it was not until perhaps 1791 that these were resolved. In 1790, Crawshay terminated the partnership, which had been barely profitable, and continued the works alone, adding further furnaces in the following years.

The Crawshay heyday

Richard Crawshay 1739–1810

Under

Under Richard Crawshay

Richard Crawshay (1739 – 27 June 1810) was a London iron merchant and then South Wales ironmaster; he was one of ten known British millionaires in 1799.

Early life and marriage

Richard Crawshay was born in Normanton in the West Riding of ...

, the Cyfarthfa works rapidly became an important producer of iron products. Great Britain was involved in various naval conflicts during this time around the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, and the demand for cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

and other weapons was great. Cyfarthfa works became critical to the success of the war effort, so much so that Admiral Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

paid a personal visit to the works in 1802. The Crawshay family crest included a pile of cannonballs in token of the crucial role of their ironworks. Richard passed on the responsibility for the works to his son, William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, but the latter was less committed to the works than his father.

William Crawshay II 1788–1867

William Crawshay II

William Crawshay II (27 March 1788 – 4 August 1867) was the son of William Crawshay I, the owner of Cyfarthfa Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales.

William Crawshay II became an ironmaster when he took over the business from his father. He wa ...

was appointed by his father William Crawshay to manage the works after Richard's death in 1810. By 1819, the ironworks had grown to six blast furnaces, producing 23,000 tons of iron. The works continued to play an enormous role in providing high-quality iron to fuel the voracious appetite of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, with the Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

sending a representative to view the production of iron rail. During this time, the Cyfarthfa works lost its position as the leading ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil to its longtime rival, the Dowlais Ironworks

The Dowlais Ironworks was a major ironworks and steelworks located at Dowlais near Merthyr Tydfil, in Wales. Founded in the 18th century, it operated until the end of the 20th, at one time in the 19th century being the largest steel producer in ...

.

It was also during this period that Crawshay had built a home, which became known as Cyfarthfa Castle

Cyfarthfa Castle ( cy, Castell Cyfarthfa; ) is a castellated mansion that was the home of the Crawshay family, ironmasters of Cyfarthfa Ironworks in Park, Merthyr Tydfil, Wales. The house commanded a view of the valley and the works, which � ...

. The buildings were erected in 1824, at a cost of £30,000 (equivalent to £2,104,964.72 in 2007). They were solidly and massively built of local stone, and designed by Robert Lugar

Robert Lugar (1773 – 23 June 1855), was a British architect and engineer in the Industrial Revolution.

Although born in Colchester, England, Lugar carried out much of his most important work in Scotland and Wales, where he was employed by s ...

, the same engineer who had built many bridges and viaducts for the local railways. It was designed in the form of a "sham" or mock castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

, complete with crenellated

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at interva ...

battlements, towers and turrets, in Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

and Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

styles, and occupied by William Crawshay II and his family. It stood, and still does, amid of landscaped parkland, and overlooked the family-owned ironworks just across the river. The Cyfarthfa Canal ceased operation in the late 1830s during William Crawshay II's time as manager.

Robert Thompson Crawshay 1847–1879

Robert Thompson Crawshay

Robert Thompson Crawshay (3 March 1817 – 10 May 1879) was a British ironmaster.

Life

Crawshay, youngest son of William Crawshay by his second wife, Bella Thompson, was born at Cyfarthfa Ironworks. He was educated at Dr. Prichard's school at ...

was the last of the great Crawshay ironmaster

An ironmaster is the manager, and usually owner, of a forge or blast furnace for the processing of iron. It is a term mainly associated with the period of the Industrial Revolution, especially in Great Britain.

The ironmaster was usually a large ...

s, as foreign competition and the rising cost of iron ore (much of which had to be imported as local supplies were exhausted) exacted a heavy toll on the Cyfarthfa works. Robert was reluctant to switch to the production of steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

, but in 1875 the works was forced to close.

Decline and final closure

The next generation

After R.T. Crawshay's death, his sons reopened the works, but soon closed again for a long and costly rebuild that was not complete until 1884, while a steel works was constructed. Crawshay Brothers, Cyfarthfa, Limited continued the business until 1902, when the works were sold to Guest Keen and Nettlefolds Limited, the proprietors of theDowlais Ironworks

The Dowlais Ironworks was a major ironworks and steelworks located at Dowlais near Merthyr Tydfil, in Wales. Founded in the 18th century, it operated until the end of the 20th, at one time in the 19th century being the largest steel producer in ...

.

By 1910, the steelworks had been forced to close again, and while it was briefly reopened in 1915 to aid in the production of materials for World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the works closed for the last time in 1919. It fell into disrepair until it was dismantled in 1928. The failure of the works was a devastating blow to the local community, as it had depended heavily on the works for its economic livelihood.

The works today

Portions of the enormous complex that formed the Cyfarthfa works remain intact today, including six of the original blast furnaces. The furnaces at Cyfarthfa are the largest and most complete surviving specimens of their type anywhere. In 2013, workers building a do-it-yourself store near the site of the old ironworks unearthed a significant portion of the old factory. Found during the excavation were a canal, tram lines and the plant's coking ovens; until the discovery, little was known about how the ironworks prepared its fuel. The structures were razed shortly after the end of World War I. Archaeologists were given an opportunity to study the artifacts before they were reburied. The site is now part of the Cyfarthfa Heritage Area and is administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. The council has plans for restoration of the ironworks site.See also

* Benjamin Hall *Pont-y-Cafnau

The Pont-y-Cafnau (Welsh, meaning ''bridge of troughs''), sometimes written ''Pont y Cafnau'' or ''Pontycafnau'', is a long iron truss bridge over the River Taff in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales. The bridge was designed by Watkin George and built i ...

, world's earliest iron railway bridge

* ''The Fire People

''The Fire People'' is a historical novel by Alexander Cordell, first published in 1972. It forms part of the 'Second Welsh Trilogy' of Cordell's writings. It tells of events leading up to the 1831 Merthyr Rising in Merthyr Tydfil and surroundin ...

'', a novel by Alexander Cordell

Alexander Cordell (9 September 1914 – 9 July 1997) was the pen name of George Alexander Graber. He was a prolific Welsh novelist and author of 30 acclaimed works which include, '' Rape of the Fair Country'', '' Hosts of Rebecca'' and '' So ...

about the lives of the workers at Cyfarthfa and surrounding districts.

* Eliot Crawshay-Williams

Eliot Crawshay-Williams (4 September 1879 – 11 May 1962), was a British author, army officer, and Liberal Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) and Parliamentary Private Secretary to Lloyd George and Winston Churchill.

Early ...

References

The Cyfarthfa Ironworks

External links

– Historical Photographs of Cyfarthfa Ironworks. {{coord, 51.7526, -3.3941, format=dms, type:landmark, display=title Buildings and structures in Merthyr Tydfil Industrial archaeological sites in Wales Ironworks and steelworks in Wales Industrial buildings completed in 1765