Cuneiform is a

logo-

syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the

Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early

Bronze Age until the beginning of the

Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-shaped impressions (

Latin: ) which form its

signs

Signs may refer to:

* ''Signs'' (2002 film), a 2002 film by M. Night Shyamalan

* ''Signs'' (TV series) (Polish: ''Znaki'') is a 2018 Polish-language television series

* ''Signs'' (journal), a journal of women's studies

*Signs (band), an American ...

. Cuneiform was originally developed to write the

Sumerian language

Sumerian is the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the oldest attested languages, dating back to at least 3000 BC. It is accepted to be a local language isolate and to have been spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, in the area that is modern-day ...

of southern

Mesopotamia (modern

Iraq). Cuneiform is the

earliest known writing system.

Over the course of its history, cuneiform was adapted to write a number of languages in addition to Sumerian.

Akkadian texts are attested from the 24th century BC onward and make up the bulk of the cuneiform record. Akkadian cuneiform was itself adapted to write the

Hittite language in the early

second millennium BC

The 2nd millennium BC spanned the years 2000 BC to 1001 BC.

In the Ancient Near East, it marks the transition from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age.

The Ancient Near Eastern cultures are well within the historical era:

The first half of the mil ...

. The other languages with significant cuneiform

corpora are

Eblaite

Eblaite (, also known as Eblan ISO 639-3), or Palaeo-Syrian, is an extinct East Semitic language used during the 3rd millennium BC by the populations of Northern Syria. It was named after the ancient city of Ebla, in modern western Syria. Varia ...

,

Elamite,

Hurrian,

Luwian, and

Urartian. The

Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan language, Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native ...

and

Ugaritic alphabets feature cuneiform-style signs; however, they are unrelated to the cuneiform logo-syllabary proper.

The latest known cuneiform tablet dates to 75 AD. The script fell totally out of use soon after and was forgotten until its rediscovery and

decipherment

In philology, decipherment is the discovery of the meaning of texts written in ancient or obscure languages or scripts. Decipherment in cryptography refers to decryption. The term is used sardonically in everyday language to describe attempts to ...

in the

19th century

The 19th (nineteenth) century began on 1 January 1801 ( MDCCCI), and ended on 31 December 1900 ( MCM). The 19th century was the ninth century of the 2nd millennium.

The 19th century was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was abolis ...

. The study of cuneiform belongs to the field of

Assyriology

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , '' -logia'') is the archaeological, anthropological, and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (a region that encompassed what is now modern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southea ...

. An estimated half a million tablets are held in museums across the world, but comparatively few of these are

published. The largest collections belong to the

British Museum ( 130,000 tablets), the

Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin, the

Louvre, the

Istanbul Archaeology Museums

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums ( tr, ) are a group of three archaeological museums located in the Eminönü quarter of Istanbul, Turkey, near Gülhane Park and Topkapı Palace.

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums consists of three museums:

#Arch ...

, the

National Museum of Iraq, the

Yale Babylonian Collection ( 40,000 tablets), and

Penn Museum.

History

Writing began after pottery was invented, during the

Neolithic, when clay tokens were used to record specific amounts of livestock or commodities.

In recent years a contrarian view has arisen on the tokens being the precursor of writing. These tokens were initially impressed on the surface of round clay envelopes (

clay bullae) and then stored in them.

The tokens were then progressively replaced by flat tablets, on which signs were recorded with a

stylus

A stylus (plural styli or styluses) is a writing utensil or a small tool for some other form of marking or shaping, for example, in pottery. It can also be a computer accessory that is used to assist in navigating or providing more precision w ...

. Writing is first recorded in

Uruk, at the end of the 4th millennium BC, and soon after in various parts of the

Near-East.

["Beginning in the pottery-phase of the Neolithic, clay tokens are widely attested as a system of counting and identifying specific amounts of specified livestock or commodities. The tokens, enclosed in clay envelopes after being impressed on their rounded surface, were gradually replaced by impressions on flat or plano-convex tablets, and these in turn by more or less conventionalized pictures of the tokens incised on the clay with a reed stylus. The transition to writing was complete ]

An ancient Mesopotamian poem gives the first known story of the

invention of writing:

The cuneiform writing system was in use for more than three millennia, through several stages of development, from the 31st century BC down to the second century AD. The latest firmly dateable tablet, from Uruk, dates to 79/80 AD. Ultimately, it was completely replaced by

alphabetic writing

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syll ...

(in the general sense) in the course of the

Roman era, and there are no cuneiform systems in current use. It had to be deciphered as a completely unknown writing system in 19th-century

Assyriology

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , '' -logia'') is the archaeological, anthropological, and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (a region that encompassed what is now modern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southea ...

. It was successfully deciphered by 1857.

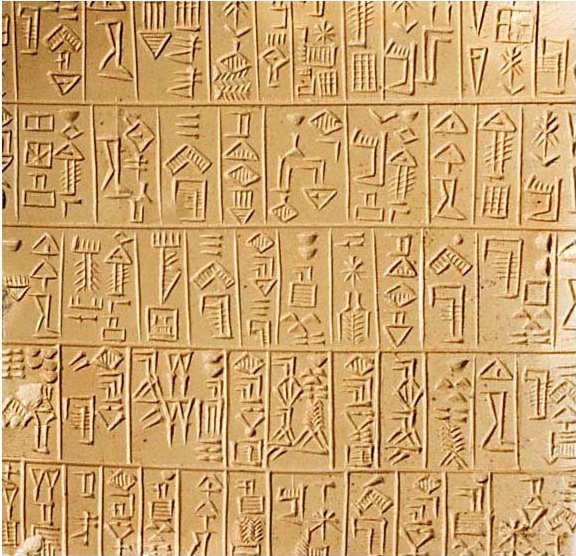

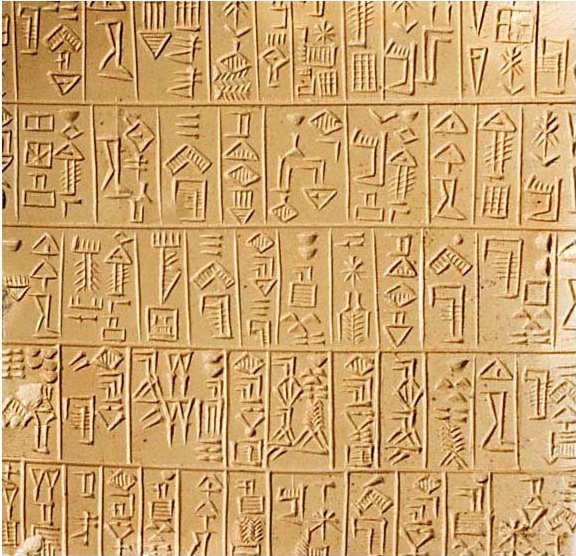

Sumerian pictographs (circa 3300 BC)

The cuneiform script was developed from

pictographic proto-writing in the late 4th millennium BC, stemming from the near eastern token system used for accounting. The meaning and usage of these tokens is still a matter of debate. These tokens were in use from the 9th millennium BC and remained in occasional use even late in the 2nd millennium BC. Early tokens with pictographic shapes of animals, associated with numbers, were discovered in

Tell Brak, and date to the mid-4th millennium BC. It has been suggested that the token shapes were the original basis for some of the Sumerian pictographs.

Mesopotamia's "proto-literate" period spans roughly the 35th to 32nd centuries BC. The first unequivocal written documents start with the Uruk IV period, from circa 3,300 BC, followed by tablets found in Uruk III,

Jemdet Nasr

Jemdet Nasr ( ar, جمدة نصر) is a tell or settlement mound in Babil Governorate (Iraq) that is best known as the eponymous type site for the Jemdet Nasr period (3100–2900 BC), and was one of the oldest Sumerian cities. The site was first ...

, Early Dynastic I

Ur and

Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo-Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

(in

Proto-Elamite) dating to the period until circa 2,900 BC.

Originally, pictographs were either drawn on

clay tablets in vertical columns with a sharpened

reed stylus

A stylus (plural styli or styluses) is a writing utensil or a small tool for some other form of marking or shaping, for example, in pottery. It can also be a computer accessory that is used to assist in navigating or providing more precision w ...

or incised in stone. This early style lacked the characteristic wedge shape of the strokes.

Most

Proto-Cuneiform records from this period were of an accounting nature.

The proto-cuneiform sign list has grown, as new texts are discovered, and shrunk, as variant signs are combined. The current sign list is 705 elements long with 42 being numeric and four considered pre-proto-Elamite.

Certain signs to indicate names of gods, countries, cities, vessels, birds, trees, etc., are known as

determinatives and were the Sumerian signs of the terms in question, added as a guide for the reader. Proper names continued to be usually written in purely "logographic" fashion.

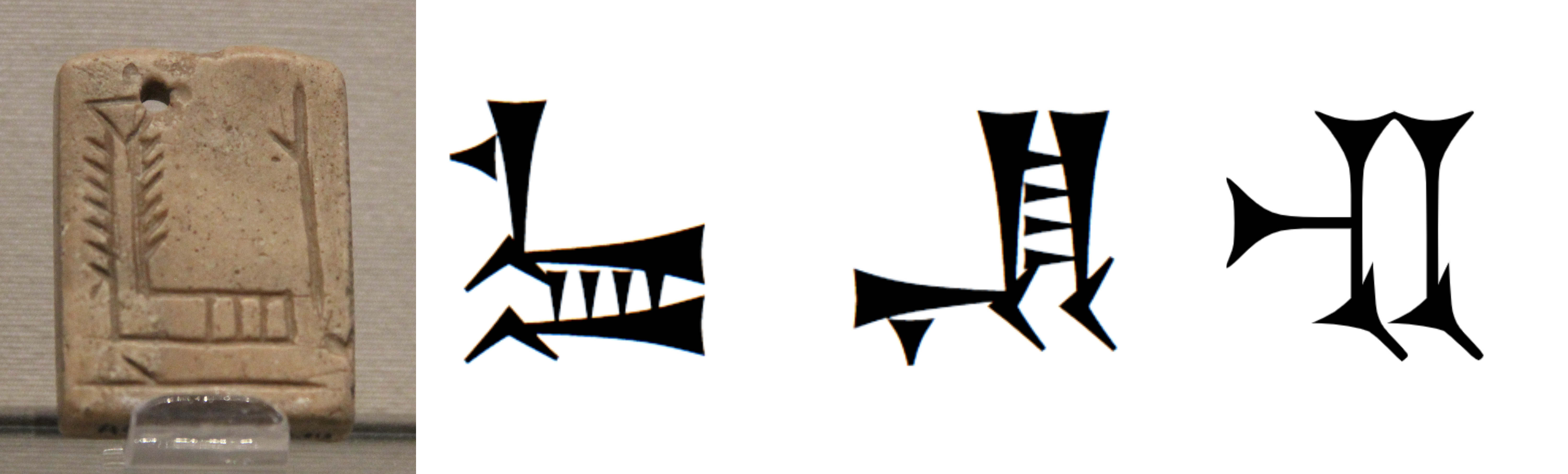

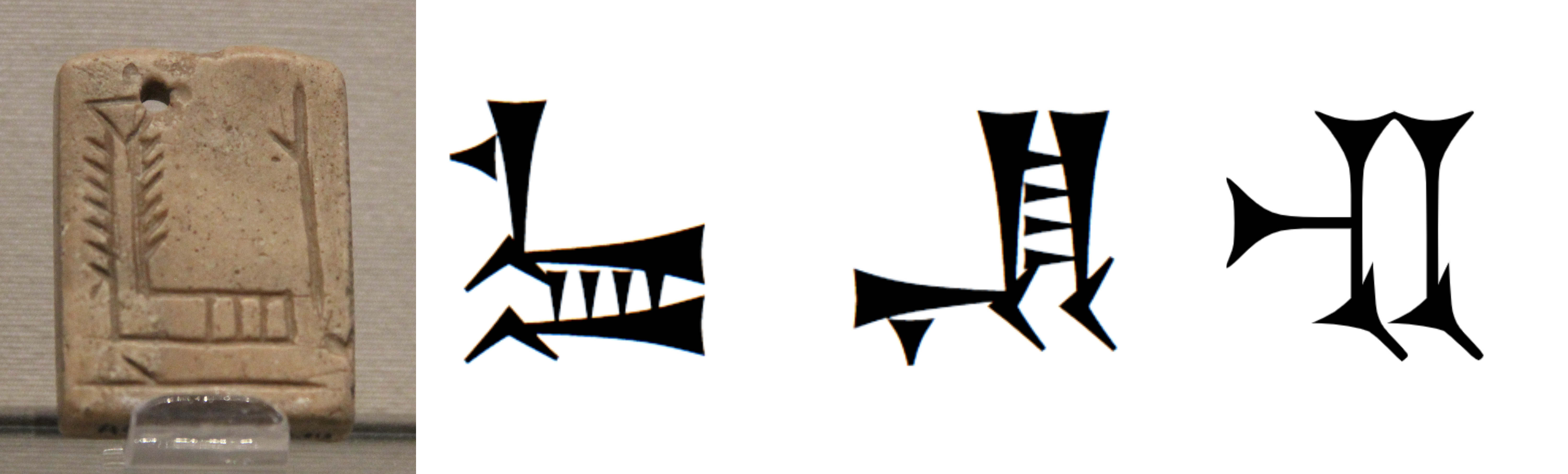

Archaic cuneiform (circa 2900 BC)

The first inscribed tablets were purely pictographic, which makes it technically difficult to know in which language they were written. Different languages have been proposed though usually Sumerian is assumed. Later tablets after circa 2,900 BC start to use syllabic elements, which clearly show a language structure typical of the non-Indo-European

agglutinative Sumerian language

Sumerian is the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the oldest attested languages, dating back to at least 3000 BC. It is accepted to be a local language isolate and to have been spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, in the area that is modern-day ...

. The first tablets using syllabic elements date to the Early Dynastic I-II, circa 2,800 BC, and they are agreed to be clearly in Sumerian.

This is the time when some pictographic element started to be used for their phonetical value, permitting the recording of abstract ideas or personal names.

Many pictographs began to lose their original function, and a given sign could have various meanings depending on context. The sign inventory was reduced from some 1,500 signs to some 600 signs, and writing became increasingly

phonological. Determinative signs were re-introduced to avoid ambiguity. Cuneiform writing proper thus arises from the more primitive system of pictographs at about that time (

Early Bronze Age II

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

).

The earliest known Sumerian king, whose name appears on contemporary cuneiform tablets, is

Enmebaragesi of Kish (fl. c. 2600 BC). Surviving records became less fragmentary for following reigns and by the end of the pre-Sargonic period it had become standard practice for each major city-state to date documents by year-names, commemorating the exploits of its ''lugal'' (king).

File:Precuneiform tablet-AO 29561-IMG 9151-gradient.jpg, Pre-cuneiform tablet, end of the 4th millennium BC.

File:Archaic cuneiform tablet E.A. Hoffman.jpg, Proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BC.

File:Cuneiform tablet- administrative account of barley distribution with cylinder seal impression of a male figure, hunting dogs, and boars MET DT847.jpg, Proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BC. A dog on a leash is visible in the background of the lower panel.

File:Blau Monument British Museum 86260.jpg, The Blau Monuments combine proto-cuneiform characters and illustrations, 3100–2700 BC. British Museum.

Cuneiforms and hieroglyphs

Geoffrey Sampson stated that

Egyptian hieroglyphs "came into existence a little after

Sumerian script

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

, and, probably,

ereinvented under the influence of the latter",

and that it is "probable that the general idea of expressing words of a language in writing was brought to Egypt from Sumerian Mesopotamia". There are many instances of

Egypt-Mesopotamia relations at the time of the invention of writing, and standard reconstructions of the

development of writing generally place the development of the Sumerian

proto-cuneiform script before the development of Egyptian hieroglyphs, with the suggestion the former influenced the latter.

Early Dynastic cuneiform (circa 2500 BC)

Early cuneiform inscription were made by using a pointed stylus, sometimes called "linear cuneiform".

Many of the early dynastic inscriptions, particularly those made on stone, continued to use the linear style as late as circa 2000 BC.

In the mid-3rd millennium BC, a new wedge-tipped stylus was introduced which was pushed into the clay, producing wedge-shaped cuneiform. This development made writing quicker and easier, especially when writing on soft clay.

By adjusting the relative position of the stylus to the tablet, the writer could use a single tool to make a variety of impressions.

For numbers, a round-tipped stylus was initially used, until the wedge-tipped stylus was generalized.

The direction of writing was from top-to-bottom and right-to-left.

Cuneiform clay tablets could be fired in

kilns to bake them hard, and so provide a permanent record, or they could be left moist and recycled if permanence was not needed, so surviving cuneiform tablets have largely been preserved by accident.

The script was also widely used on commemorative

stelae and carved reliefs to record the achievements of the ruler in whose honor the monument had been erected. The spoken language included many

homophone

A homophone () is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A ''homophone'' may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, for example ''rose'' (flower) and ''rose'' (p ...

s and near-homophones, and in the beginning, similar-sounding words such as "life"

iland "arrow"

iwere written with the same symbol. WIth the rise of the Akkadian language some signs gradually changed from being pictograms to

syllabograms, most likely to make things clearer in writing. In that way, the sign for the word "arrow" would become the sign for the sound "ti".

Words that sounded alike would have different signs; for instance, the syllable

�uhad fourteen different symbols.

When the words had a similar meaning but very different sounds they were written with the same symbol. For instance 'tooth'

u 'mouth'

aand 'voice'

uwere all written with the symbol for "voice". To be more accurate, scribes started adding to signs or combining two signs to define the meaning. They used either geometrical patterns or another cuneiform sign.

As time went by, the cuneiform got very complex and the distinction between a pictogram and syllabogram became vague. Several symbols had too many meanings to permit clarity. Therefore, symbols were put together to indicate both the sound and the meaning of a compound. The word 'raven'

GAhad the same logogram as the word 'soap'

AGA the name of a city

REŠ and the patron goddess of Eresh

ISABA Two phonetic complements were used to define the word

in front of the symbol and

ubehind. Finally, the symbol for 'bird'

UŠENwas added to ensure proper interpretation.

For unknown reasons, cuneiform pictographs, until then written vertically, were rotated 90° counterclockwise, in effect putting them on their side. This change first occurred slightly before the Akkadian period, at the time of the

Uruk ruler

Lugalzagesi (r. c. 2294–2270 BC).

The vertical style remained for monumental purposes on stone

stelas until the middle of the 2nd millennium.

Written Sumerian was used as a scribal language until the first century AD. The spoken language died out between about 2100 and 1700 BC.

Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform

: ''

DNa-ra-am

DSîn

Nanna, Sīn or Suen ( akk, ), and in Aramaic ''syn'', ''syn’'', or even ''shr'' 'moon', or Nannar ( sux, ) was the god of the moon in the Mesopotamian religions of Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia and Aram. He was also associated with ...

'', ''Sîn'' being written 𒂗𒍪 EN.ZU), appears vertically in the right column. British Museum. These are some of the more important signs: the

complete Sumero-Akkadian list of characters actually numbers about 600, with many more "values", or pronunciation possibilities.

The archaic cuneiform script was adopted by the

Akkadian Empire from the 23rd century BC (

short chronology

The chronology of the ancient Near East is a framework of dates for various events, rulers and dynasties. Historical inscriptions and texts customarily record events in terms of a succession of officials or rulers: "in the year X of king Y". Com ...

). The

Akkadian language being

East Semitic, its structure was completely different from Sumerian.

There was no way to use the Sumerian writing system as such, and the Akkadians found a practical solution in writing their language phonetically, using the corresponding Sumerian phonetic signs.

Still, some of the Sumerian characters were retained for their pictorial value as well: for example the character for "sheep" was retained, but was now pronounced ''immerū'', rather than the Sumerian "udu-meš".

The East Semitic languages employed equivalents for many signs that were distorted or abbreviated to represent new values because the syllabic nature of the script as refined by the Sumerians was not intuitive to Semitic speakers.

From the beginning of the

Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

(20th century BC), the script evolved to accommodate the various dialects of Akkadian: Old Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian.

At this stage, the former pictograms were reduced to a high level of abstraction, and were composed of only five basic wedge shapes: horizontal, vertical, two diagonals and the ''Winkelhaken'' impressed vertically by the tip of the stylus. The signs exemplary of these basic wedges are:

* AŠ (B001, U+12038)

: horizontal;

* DIŠ (B748, U+12079)

: vertical;

* GE

23, DIŠ ''tenû'' (B575, U+12039)

: downward diagonal;

* GE

22 (B647, U+1203A)

: upward diagonal;

* U (B661, U+1230B)

: the ''

Winkelhaken''.

Except for the ''Winkelhaken'', which has no tail, the length of the wedges' tails could vary as required for sign composition.

Signs tilted by about 45 degrees are called ''tenû'' in Akkadian, thus DIŠ is a vertical wedge and DIŠ ''tenû'' a diagonal one. If a sign is modified with additional wedges, this is called ''gunû'' or "gunification"; if signs are cross-hatched with additional ''Winkelhaken'', they are called ''šešig''; if signs are modified by the removal of a wedge or wedges, they are called ''nutillu''.

"Typical" signs have about five to ten wedges, while complex

ligatures

Ligature may refer to:

* Ligature (medicine), a piece of suture used to shut off a blood vessel or other anatomical structure

** Ligature (orthodontic), used in dentistry

* Ligature (music), an element of musical notation used especially in the me ...

can consist of twenty or more (although it is not always clear if a ligature should be considered a single sign or two collated, but distinct signs); the ligature KAxGUR

7 consists of 31 strokes.

Most later adaptations of Sumerian cuneiform preserved at least some aspects of the Sumerian script. Written

Akkadian included phonetic symbols from the Sumerian

syllabary

In the linguistic study of written languages, a syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent the syllables or (more frequently) moras which make up words.

A symbol in a syllabary, called a syllabogram, typically represents an (optiona ...

, together with logograms that were read as whole words. Many signs in the script were polyvalent, having both a syllabic and logographic meaning. The complexity of the system bears a resemblance to

Old Japanese, written in a Chinese-derived script, where some of these Sinograms were used as logograms and others as phonetic characters.

Elamite cuneiform

Elamite cuneiform

Elamite cuneiform was a logo-syllabic script used to write the Elamite language. The complete corpus of Elamite cuneiform consists of over 30,000 tablets and fragments. The majority belong to the Achaemenid era, and contain primarily economic rec ...

was a simplified form of the Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform, used to write the

Elamite language in the area that corresponds to modern

Iran. Elamite cuneiform at times competed with other local scripts,

Proto-Elamite and

Linear Elamite. The earliest known Elamite cuneiform text is a treaty between Akkadians and the Elamites that dates back to 2200 BC.

However, some believe it might have been in use since 2500 BC.

[Peter Daniels and William Bright (1996)] The tablets are poorly preserved, so only limited parts can be read, but it is understood that the text is a treaty between the Akkad king

Nāramsîn and Elamite ruler

Hita, as indicated by frequent references like "Nāramsîn's friend is my friend, Nāramsîn's enemy is my enemy".

The most famous Elamite scriptures and the ones that ultimately led to its decipherment are the ones found in the trilingual

Behistun inscriptions, commissioned by the

Achaemenid kings.

[Reiner, Erica (2005)] The inscriptions, similar to that of the

Rosetta Stone's, were written in three different writing systems. The first was

Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan language, Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native ...

, which was deciphered in 1802 by

Georg Friedrich Grotefend

Georg Friedrich Grotefend (9 June 1775 – 15 December 1853) was a German epigraphist and philologist. He is known mostly for his contributions toward the decipherment of cuneiform.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend had a son, named Carl Ludwig Grot ...

. The second,

Babylonian cuneiform, was deciphered shortly after the Old Persian text. Because Elamite is unlike its neighboring

Semitic languages, the script's decipherment was delayed until the 1840s. Even today, lack of sources and comparative materials hinder further research of Elamite.

Assyrian cuneiform

This "mixed" method of writing continued through the end of the

Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

n and

Assyrian empires, although there were periods when "purism" was in fashion and there was a more marked tendency to spell out the words laboriously, in preference to using signs with a phonetic complement. Yet even in those days, the Babylonian syllabary remained a mixture of logographic and phonemic writing.

Hittite cuneiform is an adaptation of the Old Assyrian cuneiform of c. 1800 BC to the

Hittite language. When the cuneiform script was adapted to writing Hittite, a layer of Akkadian logographic spellings was added to the script, thus the pronunciations of many Hittite words which were conventionally written by logograms are now unknown.

In the

Iron Age (c. 10th to 6th centuries BC), Assyrian cuneiform was further simplified. The characters remained the same as those of Sumero-Akkadian cuneiforms, but the graphic design of each character relied more heavily on wedges and square angles, making them significantly more abstract. The pronunciation of the characters was replaced by that of the Assyrian dialect of the

Akkadian language:

File:Assurbanipal King of Assyria (Sumero-Akkadian and Neo-Babylonian scripts).jpg, "

Assurbanipal King of

Assyria"

''Aššur-bani-habal šar mat Aššur

KI''

Same characters, in the classical Sumero-Akkadian script of circa 2000 BC (top), and in the Neo-Assyrian script of the

Rassam cylinder, 643 BC (bottom).

Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian language, Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur (god), Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king o ...

against "Black Pharaoh

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXV, alternatively 25th Dynasty or Dynasty 25), also known as the Nubian Dynasty, the Kushite Empire, the Black Pharaohs, or the Napatans, after their capital Napata, was the last dynasty of th ...

" Taharqa, 643 BC

From the 6th century, the

Akkadian language was marginalized by

Aramaic, written in the

Aramaean alphabet, but Neo-Assyrian cuneiform remained in use in the literary tradition well into the times of the

Parthian Empire (250 BC–226 AD). The last known cuneiform inscription, an astronomical text, was written in 75 AD. The ability to read cuneiform may have persisted until the third century AD.

Derived scripts

Old Persian cuneiform (5th century BC)

The complexity of cuneiforms prompted the development of a number of simplified versions of the script.

Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey ( Van Fo ...

was developed with an independent and unrelated set of simple cuneiform characters, by

Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

in the 5th century BC. Most scholars consider this writing system to be an independent invention because it has no obvious connections with other writing systems at the time, such as

Elamite, Akkadian,

Hurrian, and

Hittite cuneiforms.

It formed a semi-alphabetic syllabary, using far fewer wedge strokes than Assyrian used, together with a handful of logograms for frequently occurring words like "god" (), "king" () or "country" (). This almost purely alphabetical form of the cuneiform script (36 phonetic characters and 8 logograms), was specially designed and used by the early Achaemenid rulers from the 6th century BC down to the 4th century BC.

Because of its simplicity and logical structure, the Old Persian cuneiform script was the first to be deciphered by modern scholars, starting with the accomplishments of

Georg Friedrich Grotefend

Georg Friedrich Grotefend (9 June 1775 – 15 December 1853) was a German epigraphist and philologist. He is known mostly for his contributions toward the decipherment of cuneiform.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend had a son, named Carl Ludwig Grot ...

in 1802. Various ancient bilingual or trilingual inscriptions then permitted to decipher the other, much more complicated and more ancient scripts, as far back as to the 3rd millennium Sumerian script.

Ugaritic

Ugaritic was written using the

Ugaritic alphabet, a standard Semitic style

alphabet (an ''

abjad'') written using the cuneiform method.

Archaeology

Between half a million

[ and two million cuneiform tablets are estimated to have been excavated in modern times, of which only approximately 30,000][–100,000 have been read or published. The British Museum holds the largest collection (approx. 130,000 tablets), followed by the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin, the Louvre, the ]Istanbul Archaeology Museums

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums ( tr, ) are a group of three archaeological museums located in the Eminönü quarter of Istanbul, Turkey, near Gülhane Park and Topkapı Palace.

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums consists of three museums:

#Arch ...

, the National Museum of Iraq, the Yale Babylonian Collection (approx. 40,000), and Penn Museum. Most of these have "lain in these collections for a century without being translated, studied or published",

Decipherment

For centuries, travelers to Persepolis, located in Iran, had noticed carved cuneiform inscriptions and were intrigued.[Sayce 1908.] Attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey ( Van Fo ...

date back to Arabo-Persian historians of the medieval Islamic world

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, though these early attempts at decipherment

In philology, decipherment is the discovery of the meaning of texts written in ancient or obscure languages or scripts. Decipherment in cryptography refers to decryption. The term is used sardonically in everyday language to describe attempts to ...

were largely unsuccessful.

In the 15th century, the Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

Giosafat Barbaro explored ancient ruins in the Middle East and came back with news of a very odd writing he had found carved on the stones in the temples of Shiraz and on many clay tablets.

Antonio de Gouvea

Antonio de Gouvea, O.E.S.A. (1575 – 18 August 1628) was a diplomat in the service of Habsburg Spain, who served as ambassador (envoy) to Safavid Iran between 1602 and 1613. An Augustinian Portuguese missionary by origin, during his service a ...

, a professor of theology, noted in 1602 the strange writing he had seen during his travels a year earlier in Persia.[C. Wade Meade]

''Road to Babylon: Development of U.S. Assyriology,''

Brill Archive, 1974 p.5. In 1625, the Roman traveler Pietro Della Valle

Pietro Della Valle ( la, Petrus a Valle; 2 April 1586 – 21 April 1652), also written Pietro della Valle, was an Italian composer, musicologist, and author who travelled throughout Asia during the Renaissance period. His travels took him to the ...

, who had sojourned in Mesopotamia between 1616 and 1621, brought to Europe copies of characters he had seen in Persepolis and inscribed bricks from Ur and the ruins of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

. The copies he made, the first that reached circulation within Europe, were not quite accurate, but Della Valle understood that the writing had to be read from left to right, following the direction of wedges. However, he did not attempt to decipher the scripts.

Englishman Sir Thomas Herbert, in the 1638 edition of his travel book ''Some Yeares Travels into Africa & Asia the Great'', reported seeing at Persepolis carved on the wall "a dozen lines of strange characters...consisting of figures, obelisk, triangular, and pyramidal" and thought they resembled Greek. In the 1677 edition he reproduced some and thought they were 'legible and intelligible' and therefore decipherable. He also guessed, correctly, that they represented not letters or hieroglyphics but words and syllables, and were to be read from left to right. Herbert is rarely mentioned in standard histories of the decipherment of cuneiform.

In 1700 Thomas Hyde first called the inscriptions "cuneiform", but deemed that they were no more than decorative friezes.

Old Persian cuneiform: deduction of the word for "King" (circa 1800)

Proper attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform started with faithful copies of cuneiform inscriptions, which first became available in 1711 when duplicates of Darius's inscriptions were published by Jean Chardin.

Proper attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform started with faithful copies of cuneiform inscriptions, which first became available in 1711 when duplicates of Darius's inscriptions were published by Jean Chardin.[Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 9. American Oriental Society, 1950.]

Carsten Niebuhr brought very complete and accurate copies of the inscriptions at Persepolis to Europe, published in 1767 in ''Reisebeschreibungen nach Arabien'' ("Account of travels to Arabia and other surrounding lands").Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey ( Van Fo ...

, was soon perceived as being the simplest of the three types of cuneiform scripts that had been encountered, and because of this was understood as a prime candidate for decipherment (the two other, older and more complicated scripts were Elamite and Babylonian). Niebuhr identified that there were only 42 characters in the simpler category of inscriptions, which he named "Class I", and affirmed that this must therefore be an alphabetic script.Pahlavi

Pahlavi may refer to:

Iranian royalty

*Seven Parthian clans, ruling Parthian families during the Sasanian Empire

*Pahlavi dynasty, the ruling house of Imperial State of Persia/Iran from 1925 until 1979

**Reza Shah, Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878–1944 ...

and Persian under the Parsis, and published in 1771 a translation of the '' Zend Avesta'', thereby making known Avestan

Avestan (), or historically Zend, is an umbrella term for two Old Iranian languages: Old Avestan (spoken in the 2nd millennium BCE) and Younger Avestan (spoken in the 1st millennium BCE). They are known only from their conjoined use as the scrip ...

, one of the ancient Iranian languages.Naqsh-e Rostam

Naqsh-e Rostam ( lit. mural of Rostam, fa, نقش رستم ) is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 12 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into the ...

had a rather stereotyped structure on the model: "Name of the King, the Great King, the King of Iran and Aniran, son of N., the Great King, etc...".Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan language, Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native ...

language and probably mentioned Achaemenid kings.Avestan

Avestan (), or historically Zend, is an umbrella term for two Old Iranian languages: Old Avestan (spoken in the 2nd millennium BCE) and Younger Avestan (spoken in the 1st millennium BCE). They are known only from their conjoined use as the scrip ...

''xšaΘra-'' and the Sanskrit '' kṣatra-'' meaning "power" and "command", and now known to be pronounced ''xšāyaθiya'' in Old Persian.

Old Persian cuneiform: deduction of the names of Achaemenid rulers and translation (1802)

By 1802

By 1802 Georg Friedrich Grotefend

Georg Friedrich Grotefend (9 June 1775 – 15 December 1853) was a German epigraphist and philologist. He is known mostly for his contributions toward the decipherment of cuneiform.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend had a son, named Carl Ludwig Grot ...

conjectured that, based on the known inscriptions of much later rulers (the Pahlavi inscriptions of the Sassanid kings), a king's name is often followed by "great king, king of kings" and the name of the king's father.[Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 10. American Oriental Society, 1950.]Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

, his father Hystaspes Vishtaspa ( ae, wiktionary:𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀, 𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀 ; peo, wikt:𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, 𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, ), Hellenization, hellenized as Hystáspes (, ), may refer to:

* Vishtaspa (floruit, fl. ...

who was not a king, and his son the famous Xerxes. In Persian history around the time period the inscriptions were expected to be made, there were only two instances where a ruler came to power without being a previous king's son. They were Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

and Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

, both of whom became emperor by revolt. The deciding factors between these two choices were the names of their fathers and sons. Darius's father was Hystaspes Vishtaspa ( ae, wiktionary:𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀, 𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀 ; peo, wikt:𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, 𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, ), Hellenization, hellenized as Hystáspes (, ), may refer to:

* Vishtaspa (floruit, fl. ...

and his son was Xerxes, while Cyrus' father was Cambyses I and his son was Cambyses II

Cambyses II ( peo, 𐎣𐎲𐎢𐎪𐎡𐎹 ''Kabūjiya'') was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 530 to 522 BC. He was the son and successor of Cyrus the Great () and his mother was Cassandane.

Before his accession, Cambyses ...

. Within the text, the father and son of the king had different groups of symbols for names so Grotefend assumed that the king must have been Darius.Hystaspes Vishtaspa ( ae, wiktionary:𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀, 𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀 ; peo, wikt:𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, 𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, ), Hellenization, hellenized as Hystáspes (, ), may refer to:

* Vishtaspa (floruit, fl. ...

, and Darius's son Xerxes.Darius

Darius may refer to:

Persian royalty

;Kings of the Achaemenid Empire

* Darius I (the Great, 550 to 487 BC)

* Darius II (423 to 404 BC)

* Darius III (Codomannus, 380 to 330 BC)

;Crown princes

* Darius (son of Xerxes I), crown prince of Persia, ma ...

, as known from the Greeks.Hystaspes Vishtaspa ( ae, wiktionary:𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀, 𐬬𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬁𐬯𐬞𐬀 ; peo, wikt:𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, 𐎻𐏁𐎫𐎠𐎿𐎱, ), Hellenization, hellenized as Hystáspes (, ), may refer to:

* Vishtaspa (floruit, fl. ...

, but again with the supposed Persian reading of ''g-o-sh-t-a-s-p'',

External confirmation through Egyptian hieroglyphs (1823)

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when the French philologist Champollion, who had just deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, was able to read the Egyptian dedication of a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on an alabaster vase in the Cabinet des Médailles, the Caylus vase.

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when the French philologist Champollion, who had just deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, was able to read the Egyptian dedication of a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on an alabaster vase in the Cabinet des Médailles, the Caylus vase.

Consolidation of the Old Persian cuneiform alphabet

In 1836, the eminent French scholar Eugène Burnouf discovered that the first of the inscriptions published by Niebuhr contained a list of the satrapies of Darius. With this clue in his hand, he identified and published an alphabet of thirty letters, most of which he had correctly deciphered.[Prichard 1844, pp. 30–31]

A month earlier, a friend and pupil of Burnouf's, Professor Christian Lassen of Bonn, had also published his own work on ''The Old Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions of Persepolis''.

Decipherment of Elamite and Babylonian

Meanwhile, in 1835 Henry Rawlinson, a British East India Company army officer, visited the Behistun Inscriptions in Persia. Carved in the reign of King Darius of Persia (522–486 BC), they consisted of identical texts in the three official languages of the empire: Old Persian, Babylonian and Elamite. The Behistun inscription was to the decipherment of cuneiform what the Rosetta Stone (discovered in 1799) was to the decipherment of

Meanwhile, in 1835 Henry Rawlinson, a British East India Company army officer, visited the Behistun Inscriptions in Persia. Carved in the reign of King Darius of Persia (522–486 BC), they consisted of identical texts in the three official languages of the empire: Old Persian, Babylonian and Elamite. The Behistun inscription was to the decipherment of cuneiform what the Rosetta Stone (discovered in 1799) was to the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyph

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1,00 ...

s in 1822.

Rawlinson successfully completed the decipherment of Old Persian cuneiform. In 1837, he finished his copy of the Behistun inscription, and sent a translation of its opening paragraphs to the Royal Asiatic Society. Before his article could be published, however, the works of Lassen and Burnouf reached him, necessitating a revision of his article and the postponement of its publication. Then came other causes of delay. In 1847, the first part of the Rawlinson's Memoir was published; the second part did not appear until 1849. The task of deciphering Old Persian cuneiform texts was virtually accomplished.

Decipherment of Akkadian and Sumerian

The decipherment of Babylonian ultimately led to the decipherment of Akkadian, which was a close predecessor of Babylonian. The actual techniques used to decipher the Akkadian language have never been fully published; Hincks described how he sought the proper names already legible in the deciphered Persian while Rawlinson never said anything at all, leading some to speculate that he was secretly copying Hincks. They were greatly helped by the excavations of the French naturalist

The decipherment of Babylonian ultimately led to the decipherment of Akkadian, which was a close predecessor of Babylonian. The actual techniques used to decipher the Akkadian language have never been fully published; Hincks described how he sought the proper names already legible in the deciphered Persian while Rawlinson never said anything at all, leading some to speculate that he was secretly copying Hincks. They were greatly helped by the excavations of the French naturalist Paul Émile Botta

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

* Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

and English traveler and diplomat Austen Henry Layard

Sir Austen Henry Layard (; 5 March 18175 July 1894) was an English Assyriologist, traveller, cuneiformist, art historian, draughtsman, collector, politician and diplomat. He was born to a mostly English family in Paris and largely raised in It ...

of the city of Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

from 1842. Among the treasures uncovered by Layard and his successor Hormuzd Rassam were, in 1849 and 1851, the remains of two libraries, now mixed up, usually called the Library of Ashurbanipal

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BC, including texts in vari ...

, a royal archive containing tens of thousands of baked clay tablets covered with cuneiform inscriptions.

By 1851, Hincks and Rawlinson could read 200 Akkadian signs. They were soon joined by two other decipherers: young German-born scholar Julius Oppert

Julius (Jules) Oppert (9 July 1825 – 21 August 1905) was a French-German Assyriologist, born in Hamburg of Jewish parents.

Career

After studying at Heidelberg, Bonn and Berlin, he graduated at Kiel in 1847, and the next year went to France, wh ...

, and versatile British Orientalist William Henry Fox Talbot. In 1857, the four men met in London and took part in a famous experiment to test the accuracy of their decipherments. Edwin Norris, the secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society, gave each of them a copy of a recently discovered inscription from the reign of the Assyrian emperor Tiglath-Pileser I. A jury of experts was impaneled to examine the resulting translations and assess their accuracy. In all essential points, the translations produced by the four scholars were found to be in close agreement with one another. There were, of course, some slight discrepancies. The inexperienced Talbot had made a number of mistakes, and Oppert's translation contained a few doubtful passages which the jury politely ascribed to his unfamiliarity with the English language. But Hincks' and Rawlinson's versions corresponded remarkably closely in many respects. The jury declared itself satisfied, and the decipherment of Akkadian cuneiform was adjudged a ''fait accompli''.

Finally, Sumerian

Sumerian or Sumerians may refer to:

*Sumer, an ancient civilization

**Sumerian language

**Sumerian art

**Sumerian architecture

**Sumerian literature

**Cuneiform script, used in Sumerian writing

*Sumerian Records, an American record label based in ...

, the oldest language with a script, was also deciphered through the analysis of ancient Akkadian-Sumerian dictionaries and bilingual tablets, as Sumerian long remained a literary language in Mesopotamia, which was often re-copied, translated and commented in numerous Babylonian tablets.

Proper names

In the early days of cuneiform decipherment, the reading of proper names presented the greatest difficulties. However, there is now a better understanding of the principles behind the formation and the pronunciation of the thousands of names found in historical records, business documents, votive inscriptions, literary productions, and legal documents. The primary challenge was posed by the characteristic use of old Sumerian non-phonetic logograms in other languages that had different pronunciations for the same symbols. Until the exact phonetic reading of many names was determined through parallel passages or explanatory lists, scholars remained in doubt or had recourse to conjectural or provisional readings. However, in many cases, there are variant readings, the same name being written phonetically (in whole or in part) in one instance and logographically in another.

Digital approaches

Computer-based methods are being developed to digitise tablets and help decipher texts.

Transliteration

Cuneiform has a specific format for transliteration. Because of the script's

Cuneiform has a specific format for transliteration. Because of the script's polyvalence

Polyvalence or polyvalent may refer to:

*Polyvalency (chemistry), chemical species, generally atoms or molecules, which exhibit more than one chemical valence

*Polyvalence (music), the musical use of more than one harmonic function of a tonality ...

, transliteration requires certain choices of the transliterating scholar, who must decide in the case of each sign which of its several possible meanings is intended in the original document. For example, the sign dingir

''Dingir'' (, usually transliterated DIĜIR, ) is a Sumerian word for "god" or "goddess". Its cuneiform sign is most commonly employed as the determinative for religious names and related concepts, in which case it is not pronounced and is con ...

in a Hittite text may represent either the Hittite syllable ''an'' or may be part of an Akkadian phrase, representing the syllable '' il'', it may be a Sumerogram, representing the original Sumerian meaning, 'god' or the determinative for a deity. In transliteration, a different rendition of the same glyph is chosen depending on its role in the present context.

Therefore, a text containing DINGIR and MU in succession could be construed to represent the words "ana", "ila", god + "a" (the accusative case

The accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: 'me,' 'him,' 'her,' 'us,' and ‘the ...

ending), god + water, or a divine name "A" or Water. Someone transcribing the signs would make the decision how the signs should be read and assemble the signs as "ana", "ila", "Ila" ("god"+accusative case), etc. A transliteration of these signs, however, would separate the signs with dashes "il-a", "an-a", "DINGIR-a" or "Da". This is still easier to read than the original cuneiform, but now the reader is able to trace the sounds back to the original signs and determine if the correct decision was made on how to read them. A transliterated document thus presents the reading preferred by the transliterating scholar as well as an opportunity to reconstruct the original text.

There are differing conventions for transliterating Sumerian, Akkadian (Babylonian), and Hittite (and Luwian) cuneiform texts. One convention that sees wide use across the different fields is the use of acute and grave accents as an abbreviation for homophone disambiguation. Thus, ''u'' is equivalent to ''u1'', the first glyph expressing phonetic ''u''. An acute accent, ''ú'', is equivalent to the second, ''u2'', and a grave accent ''ù'' to the third, ''u3'' glyph in the series (while the sequence of numbering is conventional but essentially arbitrary and subject to the history of decipherment). In Sumerian transliteration, a multiplication sign ('×') is used to indicate typographic ligature

In writing and typography, a ligature occurs where two or more graphemes or letters are joined to form a single glyph. Examples are the characters æ and œ used in English and French, in which the letters 'a' and 'e' are joined for the first li ...

s. As shown above, signs ''as such'' are represented in capital letter

Letter case is the distinction between the letters that are in larger uppercase or capitals (or more formally ''majuscule'') and smaller lowercase (or more formally ''minuscule'') in the written representation of certain languages. The writing ...

s, while the specific reading selected in the transliteration is represented in small letters. Thus, capital letters can be used to indicate a so-called Diri compound – a sign sequence that has, in combination, a reading different from the sum of the individual constituent signs (for example, the compound IGI.A – "eye" + "water" – has the reading ''imhur'', meaning "foam"). In a Diri compound, the individual signs are separated with dots in transliteration. Capital letters may also be used to indicate a Sumerogram (for example, KÙ.BABBAR – Sumerian for "silver" – being used with the intended Akkadian reading ''kaspum'', "silver"), an Akkadogram, or simply a sign sequence of whose reading the editor is uncertain. Naturally, the "real" reading, if it is clear, will be presented in small letters in the transliteration: IGI.A will be rendered as imhur4.

Since the Sumerian language has only been widely known and studied by scholars for approximately a century, changes in the accepted reading of Sumerian names have occurred from time to time. Thus the name of a king of Ur, read ''Ur-Bau'' at one time, was later read as ''Ur-Engur'', and is now read as Ur-Nammu or Ur-Namma; for Lugal-zage-si, a king of Uruk, some scholars continued to read ''Ungal-zaggisi''; and so forth. Also, with some names of the older period, there was often uncertainty whether their bearers were Sumerians or Semites. If the former, then their names could be assumed to be read as Sumerian, while, if they were Semites, the signs for writing their names were probably to be read according to their Semitic equivalents, though occasionally Semites might be encountered bearing genuine Sumerian names. There was also doubt whether the signs composing a Semite's name represented a phonetic reading or a logographic compound. Thus, e.g. when inscriptions of a Semitic ruler of Kish, whose name was written ''Uru-mu-ush'', were first deciphered, that name was first taken to be logographic because ''uru mu-ush'' could be read as "he founded a city" in Sumerian, and scholars accordingly retranslated it back to the original Semitic as ''Alu-usharshid''. It was later recognized that the URU sign can also be read as ''rí'' and that the name is that of the Akkadian king Rimush.

Since the Sumerian language has only been widely known and studied by scholars for approximately a century, changes in the accepted reading of Sumerian names have occurred from time to time. Thus the name of a king of Ur, read ''Ur-Bau'' at one time, was later read as ''Ur-Engur'', and is now read as Ur-Nammu or Ur-Namma; for Lugal-zage-si, a king of Uruk, some scholars continued to read ''Ungal-zaggisi''; and so forth. Also, with some names of the older period, there was often uncertainty whether their bearers were Sumerians or Semites. If the former, then their names could be assumed to be read as Sumerian, while, if they were Semites, the signs for writing their names were probably to be read according to their Semitic equivalents, though occasionally Semites might be encountered bearing genuine Sumerian names. There was also doubt whether the signs composing a Semite's name represented a phonetic reading or a logographic compound. Thus, e.g. when inscriptions of a Semitic ruler of Kish, whose name was written ''Uru-mu-ush'', were first deciphered, that name was first taken to be logographic because ''uru mu-ush'' could be read as "he founded a city" in Sumerian, and scholars accordingly retranslated it back to the original Semitic as ''Alu-usharshid''. It was later recognized that the URU sign can also be read as ''rí'' and that the name is that of the Akkadian king Rimush.

Syllabary

The table below shows signs used for simple syllables of the form CV or VC. As used for the Sumerian language, the cuneiform script was in principle capable of distinguishing at least 16 consonants, transliterated as

as well as four vowel qualities, ''a, e, i, u''.

The Akkadian language had no use for ''g̃'' or ''ř'' but needed to distinguish its emphatic series

In Semitic languages, Semitic linguistics, an emphatic consonant is an obstruent consonant which originally contrasted with series of both voiced and voiceless obstruents. In specific Semitic languages, the members of this series may be realized ...

, ''q, ṣ, ṭ'', adopting various "superfluous" Sumerian signs for the purpose (e.g. ''qe''=KIN, ''qu''=KUM, ''qi''=KIN, ''ṣa''=ZA, ''ṣe''=ZÍ, ''ṭur''=DUR etc.)

Hittite, as it adopted the Akkadian cuneiform, further introduced signs such as ''wi5''=GEŠTIN.

Sign inventories

The Sumerian cuneiform script had on the order of 1,000 distinct signs (or about 1,500 if variants are included). This number was reduced to about 600 by the 24th century BC and the beginning of Akkadian records. Not all Sumerian signs are used in Akkadian texts, and not all Akkadian signs are used in Hittite.

A. Falkenstein

Adam Falkenstein (17 September 1906 – 15 October 1966) was a German Assyriologist.

He was born in Planegg, near Munich in Bavaria and died in Heidelberg.

Life

Falkenstein studied Assyriology in Munich and Leipzig. He was involved primarily ...

(1936) lists 939 signs used in the earliest period (late Uruk

The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC; also known as Protoliterate period) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named after ...

, 34th to 31st centuries). (See #Bibliography for the works mentioned in this paragraph.)

With an emphasis on ''Sumerian'' forms, Deimel (1922) lists 870 signs used in the Early Dynastic II

The Early Dynastic period (abbreviated ED period or ED) is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) that is generally dated to c. 2900–2350 BC and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of w ...

period (28th century, ''Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen'' or "LAK") and for the Early Dynastic IIIa period (26th century, ''Šumerisches Lexikon'' or "ŠL").

Rosengarten (1967) lists 468 signs used in Sumerian (pre- Sargonian) Lagash,

and Mittermayer and Attinger (2006, '' Altbabylonische Zeichenliste der Sumerisch-Literarischen Texte'' or "aBZL") list 480 Sumerian forms, written in Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian times. Regarding ''Akkadian'' forms, the standard handbook for many years was Borger (1981, ''Assyrisch-Babylonische Zeichenliste'' or "ABZ") with 598 signs used in Assyrian/Babylonian writing, recently superseded by Borger (2004, ''Mesopotamisches Zeichenlexikon'' or "MesZL") with an expansion to 907 signs, an extension of their Sumerian readings and a new numbering scheme.

Signs used in Hittite cuneiform are listed by Forrer (1922), Friedrich (1960) and Rüster and Neu (1989, ''Hethitisches Zeichenlexikon'' or "HZL"). The HZL lists a total of 375 signs, many with variants (for example, 12 variants are given for number 123 ''EGIR'').

Numerals

The Sumerians used a numerical system based on 1, 10, and 60. The way of writing a number like 70 would be the sign for 60 and the sign for 10 right after.

Usage

Cuneiform script was used in many ways in ancient Mesopotamia. Besides the well known clay tablets and stone inscriptions cuneiform was also written on wax boards, which one example from the 8th century BC was found at Nimrud. The wax contained toxic amounts of arsenic. It was used to record laws, like the Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text composed 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organised, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East. It is written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian, purportedly by Hamm ...

. It was also used for recording maps, compiling medical manuals, and documenting religious stories and beliefs, among other uses. In particular it is thought to have been used to prepare surveying data and draft inscriptions for Kassite stone kudurru

A kudurru was a type of stone document used as a boundary stone and as a record of land grants to vassals by the Kassites and later dynasties in ancient Babylonia between the 16th and 7th centuries BC. The original kudurru would typically be stor ...

. Studies by Assyriologists like Claus Wilcke and Dominique Charpin suggest that cuneiform literacy was not reserved solely for the elite but was common for average citizens.

According to the ''Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture'', cuneiform script was used at a variety of literacy levels: average citizens needed only a basic, functional knowledge of cuneiform script to write personal letters and business documents. More highly literate citizens put the script to more technical use, listing medicines and diagnoses and writing mathematical equations. Scholars held the highest literacy level of cuneiform and mostly focused on writing as a complex skill and an art form.

Modern usage

Cuneiform is occasionally used nowadays as inspiration for logos.

Ama-gi.svg, Cuneiform '' ama-gi'', literally "return to the mother", loosely translated as "liberty", is the logo of Liberty Fund.

Unicode

As of version 8.0, the following ranges are assigned to the Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform script in the Unicode Standard:

*U+12000–U+123FF (922 assigned characters) Cuneiform

*U+12400–U+1247F (116 assigned characters) Cuneiform Numbers and Punctuation

*U+12480–U+1254F (196 assigned characters) Early Dynastic Cuneiform

The final proposal for Unicode encoding of the script was submitted by two cuneiform scholars working with an experienced Unicode proposal writer in June 2004.

The base character inventory is derived from the list of Ur III signs compiled by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative of UCLA based on the inventories of Miguel Civil, Rykle Borger (2003) and Robert Englund. Rather than opting for a direct ordering by glyph shape and complexity, according to the numbering of an existing catalog, the Unicode order of glyphs was based on the Latin alphabetic order of their "last" Sumerian transliteration as a practical approximation. Once in Unicode, glyphs can be automatically processed into segmented transliterations.[Gordin S, Gutherz G, Elazary A, Romach A, Jiménez E, Berant J, et al. (2020) "Reading Akkadian cuneiform using natural language processing". ''PLoS ONE'' 15(10): e0240511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240511]

List of major cuneiform tablet discoveries

See also

* Hieratic

Hieratic (; grc, ἱερατικά, hieratiká, priestly) is the name given to a cursive writing system used for Ancient Egyptian and the principal script used to write that language from its development in the third millennium BC until the ris ...

* Babylonokia

''Babylonokia'' (also ''Babylon-Nokia'', ''Alien-Mobile'', and ''Cuneiform Mobile Phone'') is a 2012 artwork by Karl Weingärtner in the form of a clay tablet shaped like a mobile phone, its keys and screen showing cuneiform script.

Weingärtn ...

: a 21st-century cuneiform artwork

* Elamite cuneiform

Elamite cuneiform was a logo-syllabic script used to write the Elamite language. The complete corpus of Elamite cuneiform consists of over 30,000 tablets and fragments. The majority belong to the Achaemenid era, and contain primarily economic rec ...

* Hittite cuneiform

* Journal of Cuneiform Studies

* List of cuneiform signs

* List of museums of ancient Near Eastern art

This is a list of museums with major art collections from the Ancient Near East.

* British Museum, London, UK. 290,000 objects.

* Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany. 250,000 objects.

* National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad, Iraq. 170,000 objects ...

* Old Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey ( Van Fo ...

* Ugaritic alphabet

* Urartian cuneiform

* Proto-cuneiform numerals

The Proto-Cuneiform numerals are one of the most complex Numeral system, systems of enumeration in any early writing system. Their decipherment took place over several phases in the 20th century, including major advances in Adam Falkenstein’s ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Adkins, Lesley, ''Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon'', New York, St. Martin's Press (2003)

*

*

* R. Borger

Riekele or Rykle Borger (born 24 May 1929, Wiuwert, the Netherlands; died 27 December 2010, Göttingen, Germany) was a notable Dutch Assyriologist educated in the German tradition. He was the protégé of Wolfram von Soden, and taught as professo ...

, ''Assyrisch-Babylonische Zeichenliste'', 2nd ed., Neukirchen-Vluyn (1981)

*

* Burnouf, E. (1836)

"Mémoire sur deux Inscriptions Cunéiformes trouvées près d'Hamadan et qui font partie des papiers du Dr Schulz"

emoir on two cuneiform inscriptions [that werefound near Hamadan and that form part of the papers of Dr. Schulz">hat_were.html" ;"title="emoir on two cuneiform inscriptions [that were">emoir on two cuneiform inscriptions [that werefound near Hamadan and that form part of the papers of Dr. Schulz Imprimerie Royale, Paris.

* Cammarosano, M. (2017–2018

"Cuneiform Writing Techniques"

cuneiform.neocities.org (with further bibliography)

* Charvát, Petr. "Cherchez la femme: The SAL Sign in Proto-Cuneiform Writing". La famille dans le Proche-Orient ancien: réalités, symbolismes et images: Proceedings of the 55e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Paris, edited by Lionel Marti, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, 2021, pp. 169–182

*

* Anton Deimel">A. Deimel (1922), ''Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen'' ("LAK"), WVDOG 40, Berlin.

* A. Deimel (1925–1950), ''Šumerisches Lexikon'', Pontificum Institutum Biblicum.

* F. Ellermeier, M. Studt

Sumerisches Glossar

** vol. 1: 1979–1980, ,

** vol. 3.2: 1998–2005, A-B , D-E , G

** vol. 3.3: (font CD )

** vol. 3.5:

** vol 3.6: 2003, Handbuch Assur

* Robert K. Englund, Roger J. Matthews, "Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Diverse Collections", Berlin: Gebr. Mann 1996 ISBN 978-3786118756

* Robert K. Englund and Rainer M.Boehmer, "Archaic Administrative Texts from Uruk – The Early Campaigns", (ATU Bd. 5), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag 1994 ISBN 978-3786117452

* A. Falkenstein

Adam Falkenstein (17 September 1906 – 15 October 1966) was a German Assyriologist.

He was born in Planegg, near Munich in Bavaria and died in Heidelberg.

Life

Falkenstein studied Assyriology in Munich and Leipzig. He was involved primarily ...

, ''Archaische Texte aus Uruk'', Berlin-Leipzig (1936)

* Charpin, Dominique. 2004. 'Lire et écrire en Mésopotamie: une affaire dé spécialistes?' Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres: 481–501.

* E. Forrer, ''Die Keilschrift von Boghazköi'', Leipzig (1922)

* J. Friedrich, ''Hethitisches Keilschrift-Lesebuch'', Heidelberg (1960)

* Jean-Jacques Glassner, ''The Invention of Cuneiform'', English translation, Johns Hopkins University Press (2003), .

*

* Heeren (1815) "Ideen über die Politik, den Verkehr und den Handel der vornehmsten Volker der alten Welt", vol. i. pp. 563 seq., translated into English in 1833.

*

* René Labat

Jean René Labat (19 February 1892 – 8 March 1970) was a French high jumper

The high jump is a track and field event in which competitors must jump unaided over a horizontal bar placed at measured heights without dislodging it. In its moder ...

, ''Manuel d'epigraphie Akkadienne'', Geuthner, Paris (1959); 6th ed., extended by Florence Malbran-Labat (1999), .

* Lassen, Christian (1836

''Die Altpersischen Keil-Inschriften von Persepolis. Entzifferung des Alphabets und Erklärung des Inhalts.''

he Old-Persian cuneiform inscriptions of Persepolis. Decipherment of the alphabet and explanation of its content.Eduard Weber, Bonn, (Germany).

*

* Moorey, P. R. S. (1992). ''A Century of Biblical Archaeology''. Westminster Knox Press. .

* O. Neugebauer

Otto Eduard Neugebauer (May 26, 1899 – February 19, 1990) was an Austrian-American mathematician and historian of science who became known for his research on the history of astronomy and the other exact sciences as they were practiced in anti ...

, A. Sachs (eds.), ''Mathematical Cuneiform Texts'', New Haven (1945).

* Patri, Sylvain (2009). "La perception des consonnes hittites dans les langues étrangères au XIIIe siècle." ''Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie'' 99(1): 87–126. .

* Prichard, James Cowles (1844)

"Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind"

3rd ed., vol IV, Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper, London.

* Rawlinson, Henry (1847

"The Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun, decyphered and translated; with a Memoir on Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions in general, and on that of Behistun in Particular,"

''The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland'', vol. X. .

* Rune Rattenborg et al.

University of Uppsala, Cuneiform Digital Library Journal, Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative, 2021:001 ISSN 1540-8779

* Y. Rosengarten, ''Répertoire commenté des signes présargoniques sumériens de Lagash'', Paris (1967)

* Chr. Rüster, E. Neu, ''Hethitisches Zeichenlexikon'' (''HZL''), Wiesbaden (1989)

* Sayce, Rev. A. H. (1908)

"The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions"

Second Edition-revised, 1908, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, Brighton, New York; at pp 9–1

Not in copyright

* Nikolaus Schneider, ''Die Keilschriftzeichen der Wirtschaftsurkunden von Ur III nebst ihren charakteristischsten Schreibvarianten'', Keilschrift-Paläographie; Heft 2, Rom: Päpstliches Bibelinstitut (1935).

* Wilcke, Claus. 2000. Wer las und schrieb in Babylonien und Assyrien. Sitzungsberichte der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Philosophisch-historische Klasse. 2000/6. München: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

* Wolfgang Schramm, ''Akkadische Logogramme'', Goettinger Arbeitshefte zur Altorientalischen Literatur (GAAL) Heft 4, Goettingen (2003), .

* F. Thureau-Dangin, ''Recherches sur l'origine de l'écriture cunéiforme'', Paris (1898).

* Ronald Herbert Sack, ''Cuneiform Documents from the Chaldean and Persian Periods'', (1994)

External links

Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative

Tablet Collections, Cornell University

Finding aid to the Columbia University Cuneiform Collection at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library

The Cuneiform Wide Web: From Card Catalogues to Digital Assyriology - Shai Gordin and Avital Romach - ANE Today - Oct 2022

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cuneiform Script

Sumerian language

Akkadian language

Elamite language

Obsolete writing systems

Hittite language

Hurro-Urartian languages

Luwian language

Old Persian language

Ugaritic language and literature

4th-millennium BC establishments

1st-century disestablishments

History of writing

Writing systems of Asia

Writing began after pottery was invented, during the Neolithic, when clay tokens were used to record specific amounts of livestock or commodities. In recent years a contrarian view has arisen on the tokens being the precursor of writing. These tokens were initially impressed on the surface of round clay envelopes ( clay bullae) and then stored in them. The tokens were then progressively replaced by flat tablets, on which signs were recorded with a

Writing began after pottery was invented, during the Neolithic, when clay tokens were used to record specific amounts of livestock or commodities. In recent years a contrarian view has arisen on the tokens being the precursor of writing. These tokens were initially impressed on the surface of round clay envelopes ( clay bullae) and then stored in them. The tokens were then progressively replaced by flat tablets, on which signs were recorded with a  Mesopotamia's "proto-literate" period spans roughly the 35th to 32nd centuries BC. The first unequivocal written documents start with the Uruk IV period, from circa 3,300 BC, followed by tablets found in Uruk III,

Mesopotamia's "proto-literate" period spans roughly the 35th to 32nd centuries BC. The first unequivocal written documents start with the Uruk IV period, from circa 3,300 BC, followed by tablets found in Uruk III,  The first inscribed tablets were purely pictographic, which makes it technically difficult to know in which language they were written. Different languages have been proposed though usually Sumerian is assumed. Later tablets after circa 2,900 BC start to use syllabic elements, which clearly show a language structure typical of the non-Indo-European agglutinative

The first inscribed tablets were purely pictographic, which makes it technically difficult to know in which language they were written. Different languages have been proposed though usually Sumerian is assumed. Later tablets after circa 2,900 BC start to use syllabic elements, which clearly show a language structure typical of the non-Indo-European agglutinative  Early cuneiform inscription were made by using a pointed stylus, sometimes called "linear cuneiform". Many of the early dynastic inscriptions, particularly those made on stone, continued to use the linear style as late as circa 2000 BC.

In the mid-3rd millennium BC, a new wedge-tipped stylus was introduced which was pushed into the clay, producing wedge-shaped cuneiform. This development made writing quicker and easier, especially when writing on soft clay. By adjusting the relative position of the stylus to the tablet, the writer could use a single tool to make a variety of impressions. For numbers, a round-tipped stylus was initially used, until the wedge-tipped stylus was generalized. The direction of writing was from top-to-bottom and right-to-left. Cuneiform clay tablets could be fired in kilns to bake them hard, and so provide a permanent record, or they could be left moist and recycled if permanence was not needed, so surviving cuneiform tablets have largely been preserved by accident.

The script was also widely used on commemorative stelae and carved reliefs to record the achievements of the ruler in whose honor the monument had been erected. The spoken language included many

Early cuneiform inscription were made by using a pointed stylus, sometimes called "linear cuneiform". Many of the early dynastic inscriptions, particularly those made on stone, continued to use the linear style as late as circa 2000 BC.

In the mid-3rd millennium BC, a new wedge-tipped stylus was introduced which was pushed into the clay, producing wedge-shaped cuneiform. This development made writing quicker and easier, especially when writing on soft clay. By adjusting the relative position of the stylus to the tablet, the writer could use a single tool to make a variety of impressions. For numbers, a round-tipped stylus was initially used, until the wedge-tipped stylus was generalized. The direction of writing was from top-to-bottom and right-to-left. Cuneiform clay tablets could be fired in kilns to bake them hard, and so provide a permanent record, or they could be left moist and recycled if permanence was not needed, so surviving cuneiform tablets have largely been preserved by accident.

The script was also widely used on commemorative stelae and carved reliefs to record the achievements of the ruler in whose honor the monument had been erected. The spoken language included many  Words that sounded alike would have different signs; for instance, the syllable �uhad fourteen different symbols.

When the words had a similar meaning but very different sounds they were written with the same symbol. For instance 'tooth' u 'mouth' aand 'voice' uwere all written with the symbol for "voice". To be more accurate, scribes started adding to signs or combining two signs to define the meaning. They used either geometrical patterns or another cuneiform sign.

As time went by, the cuneiform got very complex and the distinction between a pictogram and syllabogram became vague. Several symbols had too many meanings to permit clarity. Therefore, symbols were put together to indicate both the sound and the meaning of a compound. The word 'raven' GAhad the same logogram as the word 'soap' AGA the name of a city REŠ and the patron goddess of Eresh ISABA Two phonetic complements were used to define the word in front of the symbol and ubehind. Finally, the symbol for 'bird' UŠENwas added to ensure proper interpretation.

For unknown reasons, cuneiform pictographs, until then written vertically, were rotated 90° counterclockwise, in effect putting them on their side. This change first occurred slightly before the Akkadian period, at the time of the Uruk ruler Lugalzagesi (r. c. 2294–2270 BC). The vertical style remained for monumental purposes on stone stelas until the middle of the 2nd millennium.

Written Sumerian was used as a scribal language until the first century AD. The spoken language died out between about 2100 and 1700 BC.

Words that sounded alike would have different signs; for instance, the syllable �uhad fourteen different symbols.

When the words had a similar meaning but very different sounds they were written with the same symbol. For instance 'tooth' u 'mouth' aand 'voice' uwere all written with the symbol for "voice". To be more accurate, scribes started adding to signs or combining two signs to define the meaning. They used either geometrical patterns or another cuneiform sign.

As time went by, the cuneiform got very complex and the distinction between a pictogram and syllabogram became vague. Several symbols had too many meanings to permit clarity. Therefore, symbols were put together to indicate both the sound and the meaning of a compound. The word 'raven' GAhad the same logogram as the word 'soap' AGA the name of a city REŠ and the patron goddess of Eresh ISABA Two phonetic complements were used to define the word in front of the symbol and ubehind. Finally, the symbol for 'bird' UŠENwas added to ensure proper interpretation.