Cryptid whale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cryptid whales are

Giglioli's Whale, or ''Amphiptera pacifica'', is a purported species of whale observed by

Giglioli's Whale, or ''Amphiptera pacifica'', is a purported species of whale observed by

The rhinoceros dolphin (''Delphinus rhinoceros'' or ''Cetodipteros rhinoceros'') is a purported species of dolphin – or dolphin-like whale – said to have an additional dorsal fin on or near the head, reminiscent of a

The rhinoceros dolphin (''Delphinus rhinoceros'' or ''Cetodipteros rhinoceros'') is a purported species of dolphin – or dolphin-like whale – said to have an additional dorsal fin on or near the head, reminiscent of a

cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

ns claimed to exist by cryptozoologists

Cryptozoology is a pseudoscience and subculture that searches for and studies unknown, legendary, or extinct animals whose present existence is disputed or unsubstantiated, particularly those popular in folklore, such as Bigfoot, the Loch Ness M ...

on the basis of informal sightings, but not accepted by taxonomist

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are given ...

s as they lack formal descriptions of type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

s. Over the past few hundred years, sailors and whalers have reported seeing whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s they cannot identify. The most well-known are Giglioli's Whale, the rhinoceros dolphin, Trunko

Trunko is the nickname for a large unidentified lump of flesh or a decomposed sea creature, a so-called "globster", reportedly sighted in Margate, South Africa on 25 October 1924. The initial source for Trunko was an article entitled "Fish Like ...

, the high-finned sperm whale, and the Alula whale.

Multiple-finned cetaceans

Records of two-finned cetaceans have been described in unverified written accounts by naturalists over the past few hundred years.Giglioli's Whale

Giglioli's Whale, or ''Amphiptera pacifica'', is a purported species of whale observed by

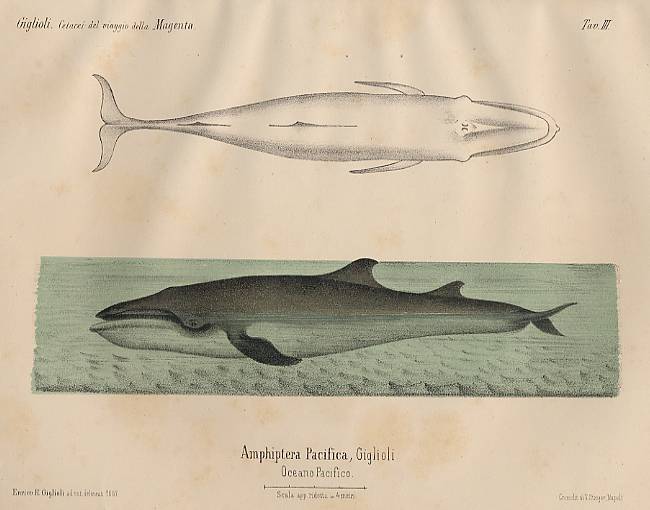

Giglioli's Whale, or ''Amphiptera pacifica'', is a purported species of whale observed by Enrico Hillyer Giglioli

Enrico Hillyer Giglioli (13 June 1845 – 16 December 1909) was an Italians, Italian zoologist and anthropologist.

Giglioli was born in London and first studied there. He obtained a degree in science at the University of Pisa in 1864 and started ...

. It is described to have two dorsal fins, a feature which no known whales have. On September 4, 1867, on board a ship called the ''Magenta'' about off the coast of Chile, the zoologist spotted a species of whale which he could not recognize. It was very close to the ship (too close to shoot with a cannon) and was observed for a quarter of an hour, allowing Giglioli to make very detailed observations. The whale looked overall similar to a rorqual, long with an elongated body, but the most notable difference was the presence of two large dorsal fins about apart. Other unusual features include the presence of two long sickle-shaped flippers and a lack of throat pleats. Another report of a two finned whale of roughly the same size was recorded from the ship ''Lily'' off the coast of Scotland the following year. In 1983 between Corsica and the French mainland, French zoologist Jacques Maigret sighted a similar looking creature. Although it has not been proven to exist, it was given a "classification" by Giglioli. The whale may have been a genetic mutation. Given the species' alleged size and attributes, it is extremely doubtful such a species would not have been taken (and reported) by modern commercial whalers, bringing into doubt its very existence.

Rhinoceros dolphin

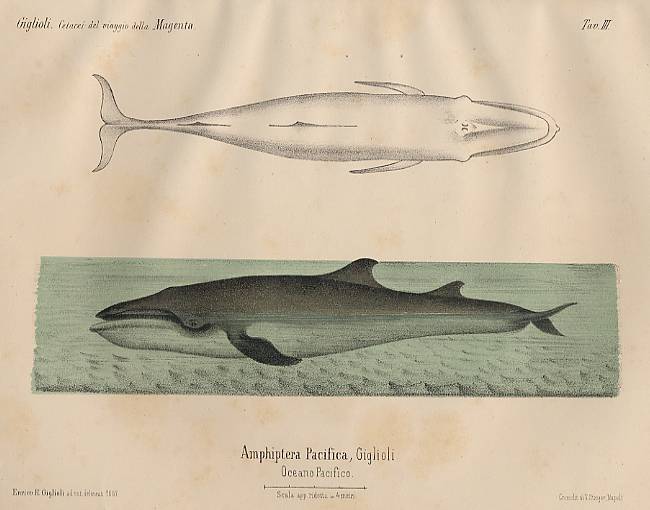

The rhinoceros dolphin (''Delphinus rhinoceros'' or ''Cetodipteros rhinoceros'') is a purported species of dolphin – or dolphin-like whale – said to have an additional dorsal fin on or near the head, reminiscent of a

The rhinoceros dolphin (''Delphinus rhinoceros'' or ''Cetodipteros rhinoceros'') is a purported species of dolphin – or dolphin-like whale – said to have an additional dorsal fin on or near the head, reminiscent of a rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct species o ...

horn. Jean René Constant Quoy

Jean René Constant Quoy (10 November 1790 in Maillé, Vendée, Maillé – 4 July 1869 in Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, Rochefort) was a French naval surgeon, zoologist and anatomist.

In 1806, he began his medical studies at the school of naval ...

and Joseph Gaimard allegedly discovered this dolphin off the coast of the Sandwich Islands and New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. It supposedly possesses two dorsal fins, much like Giglioli's Whale. One is near the head, where the neck would be on terrestrial animals, and the other is farther back than the dorsal fin of any other dolphin. These have a somewhat large size, and are black with large white blotches. Michel Raynal suggested it may have been misobserved somersault behavior (with the first "fin" being a flipper and the second being a fluke), but dismissed it as unlikely. Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

proposed it may have been an optical illusion and Richard Ellis suggested it may have been a dolphin with a remora

The remora (), sometimes called suckerfish, is any of a family (Echeneidae) of ray-finned fish in the order Carangiformes. Depending on species, they grow to long. Their distinctive first dorsal fins take the form of a modified oval, sucker-li ...

stuck on its head. Markus Bühler pointed out that one dolphin's deformed jaw curiously resembles the oddly placed fin or "horn" of the rhinoceros dolphin. Supernumerary dorsal fins are apparently a genuine mutation; however, none have turned up a considerable distance from where the dorsal fin should be positioned, let alone on the head. Raynal and Sylvestre (1991) argued that since Quoy and Gaimard observed multiple individuals exhibiting the morphology, a distinct species, ''Cetodipterus rhinoceros'', would be more probable than a pod of disfigured individuals. Another argued hypothesis is that that pod was part of an inbred

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders and o ...

population, which led to the mutation. Another possibility is that Quoy and Gaimard observed specimens which were neither deformed nor members of an unknown species or population, but rather misidentified a pair of beaked whales that, by perspective, appeared to be one single creature.

High-finned sperm whale

The high-finned sperm whale, or the high-finned cachalot, is an alleged variant or relative of the known sperm whale, ''Physeter macrocephalus'', with an unusually tall dorsal fin from the North Atlantic. Thephysician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

Sir Robert Sibbald

Sir Robert Sibbald (15 April 1641 – August 1722) was a Scottish physician and antiquary.

Life

He was born in Edinburgh, the son of David Sibbald (brother of Sir James Sibbald) and Margaret Boyd (January 1606 – 10 July 1672). Educated at th ...

, in 1687, described an alleged stranded female individual on Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

, saying its dorsal fins was similar to a "mizzen mast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation ligh ...

", and the whale, based on Sibbald's account, was described as ''P. tursio''. However, naturalist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

disregarded Sibbald's claim as a bad description of the carcass, as well as dismissing the name ''P. tursio''. Another alleged sighting was off the Annapolis Basin

The Annapolis Basin is a sub-basin of the Bay of Fundy, located on the bay's southeastern shores, along the northwestern shore of Nova Scotia and at the western end of the Annapolis Valley.

The basin takes its name from the Annapolis River, which ...

, Nova Scotia, Canada on September 27, 1946, where the creature was apparently trapped there for two days. Its length was estimated to be between .

Alula whale

The Alula whale, or the Alula killer, or ''Orcinus mörzer-bruynsus'', was discussed and illustrated for the first time, but not formally named, by W. F. J. Mörzer Bruyns in ''Field Guide of Whales and Dolphins'', purportedly being seen by the author several times. It resembles a sepia brownkiller whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white pa ...

with a well-rounded forehead and white, star-like scars on the body. He wrote they are present in the deep coastal waters in eastern Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden ( ar, خليج عدن, so, Gacanka Cadmeed 𐒅𐒖𐒐𐒕𐒌 𐒋𐒖𐒆𐒗𐒒) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channe ...

to Socotra

Socotra or Soqotra (; ar, سُقُطْرَىٰ ; so, Suqadara) is an island of the Republic of Yemen in the Indian Ocean, under the ''de facto'' control of the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist participant in Yemen’s ...

, and they were seen in April, May, June, and September. He estimated it to be roughly long, weigh around , and have a dorsal fin that is around high. Bruyns reported that they maintained a cruising speed of 4 knots, and traveled in groups of 4 to 8, but usually 6.

Unidentified beaked whales

The "Moore's Beach monster", an initially unidentified carcass found in 1925 on Moore's Beach onMonterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area and its major city at the south of the bay, San Jose. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by a ...

was identified by the California Academy of Sciences

The California Academy of Sciences is a research institute and natural history museum in San Francisco, California, that is among the largest museums of natural history in the world, housing over 46 million specimens. The Academy began in 1853 ...

as a Baird's beaked whale

Baird's beaked whale (''Berardius bairdii''), also known as the northern giant bottlenose whale, North Pacific bottlenose whale, giant four-toothed whale, northern four-toothed whale and the North Pacific four-toothed whale, is a species of whale ...

.

Regarding similar cases relating to beaked whale

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of the 24 species are reasonably well-k ...

s, an unknown type of large beaked whale of similar size to fully grown '' Berardius bairdii'' have been reported to live in the Sea of Okhotsk. These whales are claimed to have heads somewhat resembling Longman's beaked whale

The tropical bottlenose whale (''Indopacetus pacificus''), also known as the Indo-Pacific beaked whale or Longman's beaked whale, was considered to be the world's rarest cetacean until recently, but the spade-toothed whale now holds that positio ...

s, and there have been claims that records of strandings of these whales exist along the areas within and adjacent to Tatar Strait

Strait of Tartary or Gulf of Tartary (russian: Татарский пролив; ; ja, 間宮海峡, Mamiya kaikyō, Mamiya Strait; ko, 타타르 해협) is a strait in the Pacific Ocean dividing the Russian island of Sakhalin from mainland Asia ...

in the 2010s. In addition, possible new species of beaked whales have been described to be present in the coastal and pelagic waters of Abashiri

is a city located in Okhotsk Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan.

Abashiri is known as the site of the Abashiri Prison, a Meiji-era facility used for the incarceration of political prisoners. The old prison has been turned into a museum, but the city ...

and Shiretoko Peninsula

is located on the easternmost portion of the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, protruding into the Sea of Okhotsk. It is separated from Kunashir Island, which is now occupied by Russia, by the Nemuro Strait. The name Shiretoko is derived from the ...

northeastern Hokkaido

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

.

See also

*List of cryptids

Cryptids are animals that cryptozoologists believe may exist somewhere in the wild, but are not believed to exist by mainstream science. Cryptozoology is a pseudoscience, which primarily looks at anecdotal stories, and other claims rejected b ...

References

{{reflist Cryptozoology Whales