Crispi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

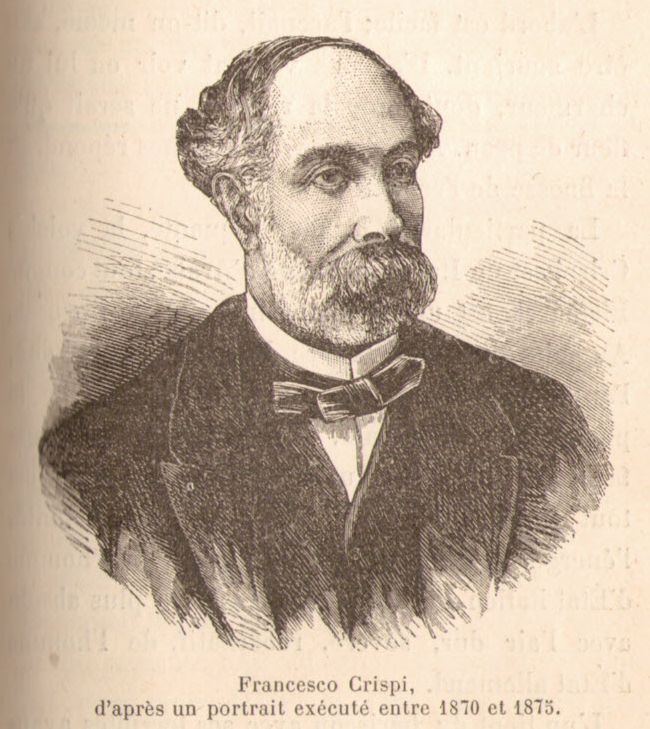

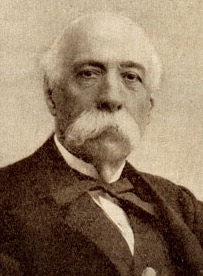

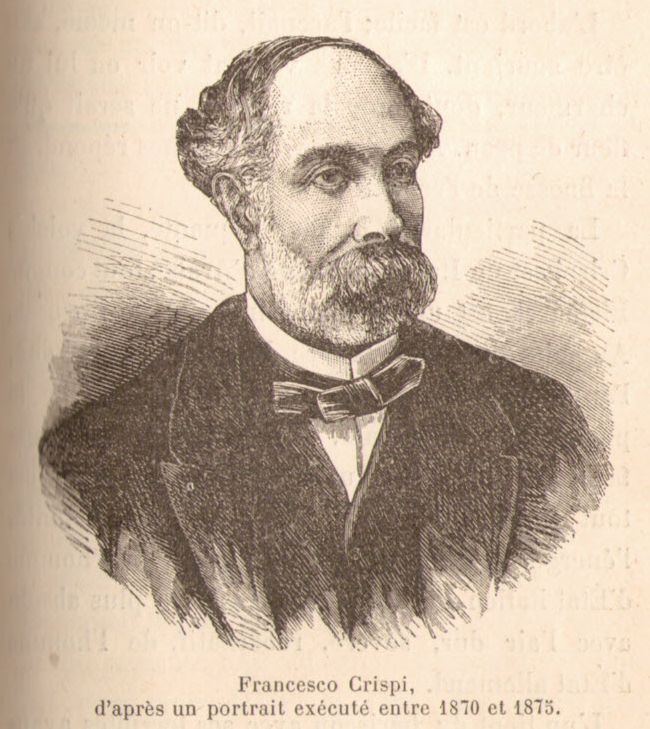

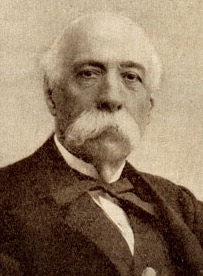

Francesco Crispi (4 October 1818 – 11 August 1901) was an Italian patriot and statesman. He was among the main protagonists of the Risorgimento, a close friend and supporter of Giuseppe Mazzini and

Christopher Duggan, History Today, 1 February 2002 Crispi served as

by David Gilmour, The Spectator, 1 June 2002 (Review of Francesco Crispi, 1818-1901: From Nation to Nationalism, by Christopher Duggan)

Conflict on the Nile

', p. 61Crispi, Francesco

Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 30 (1984)Gilmour

The Pursuit of Italy

/ref> His grandfather was an

pp. 222–23

/ref> where he distinguished himself for his liberal and revolutionary ideas.

The

The

The New York Times, 10 June 1894

In 1849, he moved to

In 1849, he moved to

He helped persuade

He helped persuade

After the fall of Palermo, Crispi was appointed First Secretary of State in the provisional government; shortly a struggle began between Garibaldi's government and the emissaries of Cavour on the question of timing of the annexation of Sicily by Italy. It was established a Sicilian Army and a fleet of the Dictatorship Government of Sicily.

The pace of Garibaldi's victories had worried Cavour, who in early July sent to the provisional government a proposal of immediate annexation of Sicily to

After the fall of Palermo, Crispi was appointed First Secretary of State in the provisional government; shortly a struggle began between Garibaldi's government and the emissaries of Cavour on the question of timing of the annexation of Sicily by Italy. It was established a Sicilian Army and a fleet of the Dictatorship Government of Sicily.

The pace of Garibaldi's victories had worried Cavour, who in early July sent to the provisional government a proposal of immediate annexation of Sicily to

The general election of 1861 took place on 27 January, even before the formal birth of the

The general election of 1861 took place on 27 January, even before the formal birth of the

In December 1877 he replaced

In December 1877 he replaced

For nine years Crispi remained politically under a cloud, leading the "progressive" opposition. In 1881 Crispi was among the main supporters of the universal male suffrage, which was approved by the government of

For nine years Crispi remained politically under a cloud, leading the "progressive" opposition. In 1881 Crispi was among the main supporters of the universal male suffrage, which was approved by the government of

True to his initial progressive leanings he moved ahead with stalled reforms, abolishing the death penalty, revoking anti-strike laws, limiting police powers, reforming the penal code and the administration of justice with the help of his Minister of Justice Giuseppe Zanardelli, reorganising charities and passing public health laws and legislation to protect emigrants that worked abroad. He sought popular support for the state with a programme of orderly development at home and expansion abroad.Sarti, ''Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present''

True to his initial progressive leanings he moved ahead with stalled reforms, abolishing the death penalty, revoking anti-strike laws, limiting police powers, reforming the penal code and the administration of justice with the help of his Minister of Justice Giuseppe Zanardelli, reorganising charities and passing public health laws and legislation to protect emigrants that worked abroad. He sought popular support for the state with a programme of orderly development at home and expansion abroad.Sarti, ''Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present''

pp. 43–44

/ref>Seton-Watson, ''Italy from liberalism to fascism'', p. 131

In 1889 Crispi's government promoted a reform of the magistracy and promulgated a new penal code, which unified penal legislation in Italy, abolished death sentence and recognised the right to strike. The code was regarded as a great work by contemporary European jurists. The code was named after Giuseppe Zanardelli, then Minister of Justice, who promoted the approval of the code.

Another important reform was that of local government, or '' comuni'', which was approved by the Chamber in July 1888, in just three weeks. The new reform almost doubled the local electorate, incrementing the suffrage. But the most controversial part of the law was related to the mayors, who were previously appointed by the government, and who would now elected by the electors, in the municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants and in all the provincial capitals. The law also introduced the office of the prefect. The reform was approved by the Senate in December 1888 and entered into force in February 1889.

On 22 December 1888, the Freemason Crispi enacted the first Italian law for the national healthcare system including the

In 1889 Crispi's government promoted a reform of the magistracy and promulgated a new penal code, which unified penal legislation in Italy, abolished death sentence and recognised the right to strike. The code was regarded as a great work by contemporary European jurists. The code was named after Giuseppe Zanardelli, then Minister of Justice, who promoted the approval of the code.

Another important reform was that of local government, or '' comuni'', which was approved by the Chamber in July 1888, in just three weeks. The new reform almost doubled the local electorate, incrementing the suffrage. But the most controversial part of the law was related to the mayors, who were previously appointed by the government, and who would now elected by the electors, in the municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants and in all the provincial capitals. The law also introduced the office of the prefect. The reform was approved by the Senate in December 1888 and entered into force in February 1889.

On 22 December 1888, the Freemason Crispi enacted the first Italian law for the national healthcare system including the

One of his first acts as premier was a visit to the German chancellor

One of his first acts as premier was a visit to the German chancellor

In December 1893 the impotence of the Giolitti cabinet to restore public order, menaced by disturbances in Sicily and the

In December 1893 the impotence of the Giolitti cabinet to restore public order, menaced by disturbances in Sicily and the

The New York Times, 17 June 1894 On 24 June an Italian anarchist killed French President Carnot. In this climate of increased the fear of anarchism, Crispi was able to introduce a series of anti-anarchist laws in July 1894, which were also used against socialists. Heavy penalties were announced for "incitement to class hatred" and police received extended powers of preventive arrest and deportation. The whole parliament expressed solidarity with the Prime Minister who saw his position considerably strengthened. This favored the approval of the Sonnino law. The reform saved Italy from the crisis and started the way for economic recovery.

During his second term, Crispi continued his colonial expansionist policy in

During his second term, Crispi continued his colonial expansionist policy in

''The New York Times'', 5 July 1896 In Rome, people demonstrated under the slogans "death to the king!" and "long live the republic!" as the war had badly damaged the prestige of Umberto who had backed Crispi so forcefully and strongly. Crispi was opposed to making peace with Ethiopia, saying he regarded it as humiliating for the Italians to make peace with "barbarians" as he called the Ethiopians and said he did not care about the lives of almost 3,000 Italians taken prisoner by the Ethiopians who were being held as hostages, saying they were "expendable" compared to the "glorious" national mission of conquering Ethiopia.

The ensuing Antonio di Rudini cabinet lent itself to Cavallotti's campaign, and at the end of 1897 the judicial authorities applied to the Chamber of Deputies for permission to prosecute Crispi for embezzlement. A parliamentary commission of inquiry discovered only that Crispi, on assuming office in 1893, had found the secret service coffers empty, and had borrowed money from a state bank to fund it, repaying it with the monthly installments granted in regular course by the treasury. The commission, considering this proceeding irregular, proposed, and the Chamber adopted, a vote of censure, but refused to authorize a prosecution.

Crispi resigned his seat in parliament, but was re-elected by an overwhelming majority in April 1898 by his Palermo constituents. For some time he took little part in active politics, chiefly on account of his growing blindness. A successful operation for cataract restored his eyesight in June 1900, and notwithstanding his 81 years, he resumed to some extent his former political activity.

Soon afterward, however, his health began to give way and he died in

The ensuing Antonio di Rudini cabinet lent itself to Cavallotti's campaign, and at the end of 1897 the judicial authorities applied to the Chamber of Deputies for permission to prosecute Crispi for embezzlement. A parliamentary commission of inquiry discovered only that Crispi, on assuming office in 1893, had found the secret service coffers empty, and had borrowed money from a state bank to fund it, repaying it with the monthly installments granted in regular course by the treasury. The commission, considering this proceeding irregular, proposed, and the Chamber adopted, a vote of censure, but refused to authorize a prosecution.

Crispi resigned his seat in parliament, but was re-elected by an overwhelming majority in April 1898 by his Palermo constituents. For some time he took little part in active politics, chiefly on account of his growing blindness. A successful operation for cataract restored his eyesight in June 1900, and notwithstanding his 81 years, he resumed to some extent his former political activity.

Soon afterward, however, his health began to give way and he died in

The New York Times, 12 August 1901 according to many witnesses, his last words were: "Before closing my eyes to life, I would have the supreme comfort of knowing that our homeland is beloved and defended by all its sons".

Conflict on the Nile

', p. 61 Although he began life as a revolutionary and democratic figure, his premiership was authoritarian and he showed disdain for Italian liberals. He was born as a firebrand and died as firefighter.

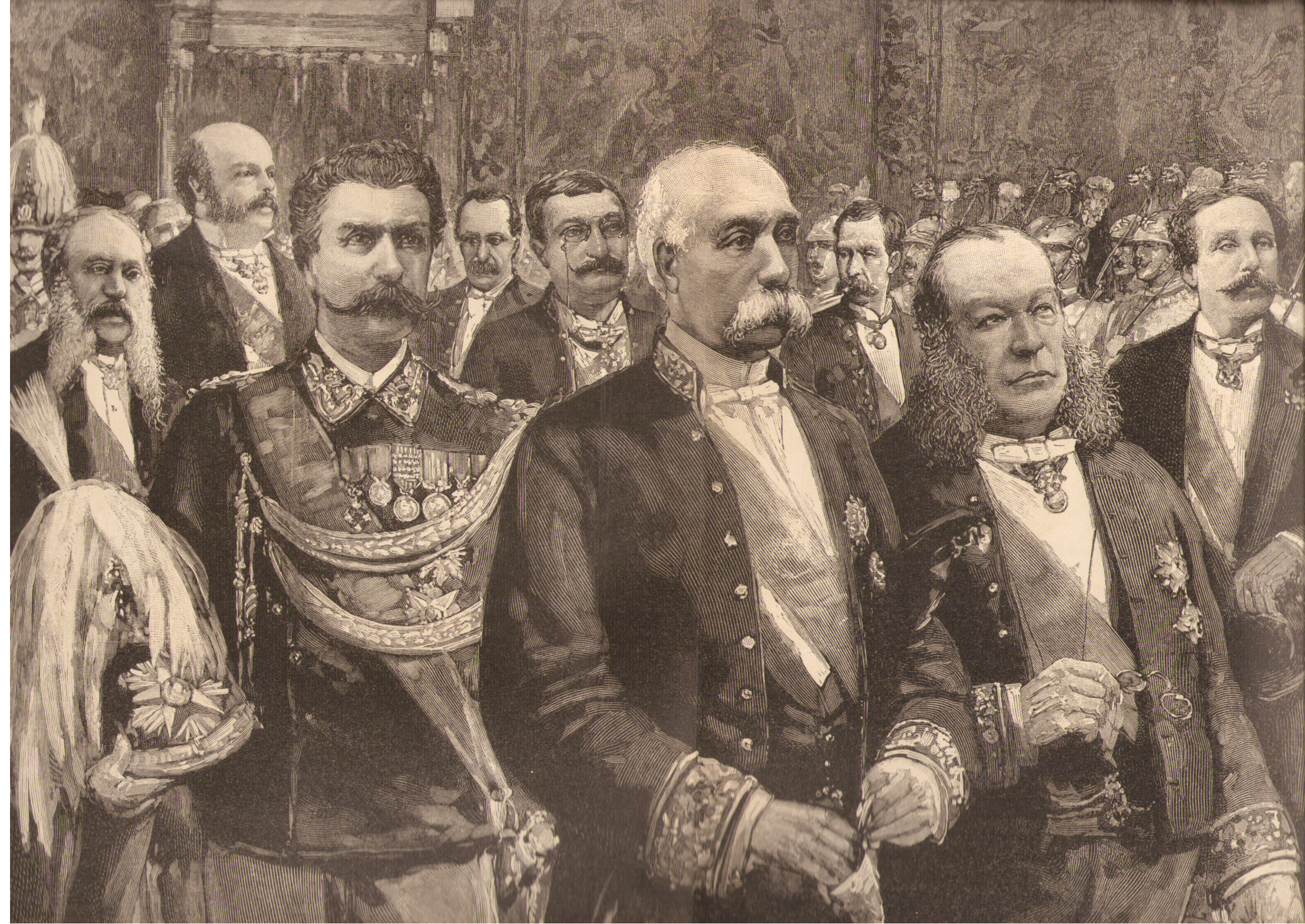

La Repubblica, 13 December 2012 At the end of the 19th century, Crispi was the dominant figure of Italian politics for a decade. He was saluted by As prime minister in the 1880s and 1890s, Crispi was internationally famous and often mentioned along with world statesmen such as Bismarck,

As prime minister in the 1880s and 1890s, Crispi was internationally famous and often mentioned along with world statesmen such as Bismarck,

p. 29

/ref>

Italy and the Wider World: 1860-1960

', New York: Routledge, * Duggan, Christopher. (2002) "Nation-building in 19th-century Italy: The Case of Francesco Crispi", ''History Today'' . 52:2: (2002): pp. 9–18. * Duggan, Christopher. "Francesco Crispi's relationship with Britain: from admiration to disillusionment." ''Modern Italy'' 16.4 (2011): 427–436. * Duggan, Christopher (2002).

Francesco Crispi, 1818–1901 : From Nation to Nationalism

', Oxford University Press, * Gilmour, David (2011).

The Pursuit of Italy: A History of a Land, its Regions and their Peoples

', London: Penguin UK, * Mack Smith, Denis (1989). ''Italy and Its Monarchy'', New Haven; Yale, * Sarti, Roland (2004).

Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present

', New York: Facts on File Inc., * Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967).

Italy from liberalism to fascism, 1870–1925

', New York: Taylor & Francis, * Vandervort, Bruce (1998),

Wars Of Imperial Conquest In Africa, 1830-1914

', London: Taylor & Francis, * Scichilone, Giorgio (2012), ''Francesco Crispi'', Flaccovio, Palermo, , in Italian * Stilllman, William James (1899).

Francesco Crispi: Insurgent, Exile, Revolutionist and Statesman

', London: Grant Richards * * Wright, Patricia (1972).

Conflict on the Nile: the Fashoda incident of 1898

', Heinemann,

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

, and one of the architects of Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

in 1860.Nation-building in 19th-century Italy: the case of Francesco CrispiChristopher Duggan, History Today, 1 February 2002 Crispi served as

Prime Minister of Italy

The Prime Minister of Italy, officially the President of the Council of Ministers ( it, link=no, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri), is the head of government of the Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is ...

for six years, from 1887 to 1891, and again from 1893 to 1896, and was the first Prime Minister from Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

. Crispi was internationally famous and often mentioned along with world statesmen such as Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

, and Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

.

Originally an Italian patriot and democrat liberal, Crispi went on to become a bellicose authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

prime minister and an ally and admirer of Bismarck. He was indefatigable in stirring up hostility toward France. His career ended amid controversy and failure: he got involved in a major banking scandal and fell from power in 1896 after the devastating loss of the Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ti, ውግእ ዓድዋ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The d ...

, which repelled Italy's colonial ambitions over Ethiopia. Due to his authoritarian policies and style, Crispi is often regarded as a strongman and seen as a precursor of the Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

.The Randolph Churchill of Italyby David Gilmour, The Spectator, 1 June 2002 (Review of Francesco Crispi, 1818-1901: From Nation to Nationalism, by Christopher Duggan)

Early life

Crispi's paternal family came originally from the small agricultural community ofPalazzo Adriano

Palazzo Adriano ( IPA: , aae, Pallaci, scn, U PalàzzuGasca Queirazza, Giuliano (ed.) (1990). ''Dizionario di toponomastica. Storia e significato dei nomi geografici italiani'', p. 468. UTET. ) is a town and ''comune'' of Arbëresh origin in t ...

, in south-western Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. It had been founded in the later fifteenth century by Orthodox Christian

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churche ...

Albanians

The Albanians (; sq, Shqiptarët ) are an ethnic group and nation native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Se ...

(Arbëreshë Arbën/Arbër, from which derived Arbënesh/Arbëresh originally meant all Albanians, until the 18th century. Today it is used for different groups of Albanian origin, including:

* Arbër (given name), an Albanian masculine given name

* Arbëresh ...

), who settled in Sicily after the Ottoman occupation of Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

.Wright, Conflict on the Nile

', p. 61Crispi, Francesco

Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 30 (1984)Gilmour

The Pursuit of Italy

/ref> His grandfather was an

Arbëreshë Arbën/Arbër, from which derived Arbënesh/Arbëresh originally meant all Albanians, until the 18th century. Today it is used for different groups of Albanian origin, including:

* Arbër (given name), an Albanian masculine given name

* Arbëresh ...

Orthodox priest; the parish priests were married men, and Arbëreshë Arbën/Arbër, from which derived Arbënesh/Arbëresh originally meant all Albanians, until the 18th century. Today it is used for different groups of Albanian origin, including:

* Arbër (given name), an Albanian masculine given name

* Arbëresh ...

was the family language down to the lifetime of the young Crispi.Stillman, ''Francesco Crispi'', p. 23 Crispi himself was born in Ribera, Sicily, to Tommaso Crispi, a grain merchant

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals and other food grains such as wheat, barley, maize, and rice. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other ...

and Giuseppa Genova from Ribera; he was baptised as a Greek Catholic The term Greek Catholic Church can refer to a number of Eastern Catholic Churches following the Byzantine (Greek) liturgy, considered collectively or individually.

The terms Greek Catholic, Greek Catholic church or Byzantine Catholic, Byzantine Ca ...

. Belonging to a family of Arbëreshë descent, he spoke Italian as his third or fourth language. His uncle Giuseppe

Giuseppe is the Italian form of the given name Joseph,

from Latin Iōsēphus from Ancient Greek Ἰωσήφ (Iōsḗph), from Hebrew יוסף.

It is the most common name in Italy and is unique (97%) to it.

The feminine form of the name is Giusep ...

wrote the first monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monograph ...

on the Albanian language

Albanian ( endonym: or ) is an Indo-European language and an independent branch of that family of languages. It is spoken by the Albanians in the Balkans and by the Albanian diaspora, which is generally concentrated in the Americas, Europ ...

. In a telegram from 1895 on the Albanian question, Francesco Crispi said of his origins that he was "an Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

by blood and heart" and an Italo-Albanian from Sicily. "Crispi... In accepting the honor, he wired to the congress that as "an Albanian by blood and heart" -he was an Italo-Albanian from Sicily"

At the age of five he was sent to a family in Villafranca

Villafranca (Basque: ''Alesbes'') is a town and municipality located in the province and the autonomous community (Comunidad Foral) of Navarre, northern Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo ...

, where he could receive an education. In 1829, at 11 years old, he attended a seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

in Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan ...

, where he studied classical subjects. The rector of the institute was Giuseppe Crispi

Giuseppe Crispi ( Arbërisht: Zef Krispi; 1781–1859) was an Italian philologist and priest of Arbëresh descent. One of the major figures of the Arbëresh community of Sicily of that era, he wrote a number of works on the Albanian language. ...

, his uncle. Crispi attended the seminary until 1834 or 1835, when his father, after becoming mayor of Ribera, encountered major difficulties in health and finances.

In the same period, Crispi became a close friend of the poet and doctor Vincenzo Navarro, whose friendship marked his initiation to the Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. In 1835 he studied law and literature at the University of Palermo receiving a law degree in 1837; in the same year he fell in love with Rosina D'Angelo, the daughter of a goldsmith. Despite his father's ban, Crispi married Rosina in 1837, when she was already pregnant. In May Crispi became the father of his first daughter, Giuseppa, who was named after his grandmother. It was a brief marriage: Rosina died on 29 July 1839, the day after giving birth to her second son, Tommaso; the child lived only a few hours and in December, also Giuseppa died.

Between 1838 and 1839, Crispi founded his own newspaper, ''L'Oreteo'', from the name of the Sicilian river Oreto. This experience brought him into contact with a number of political figures including the Neapolitan liberal activist and poet, Carlo Poerio. In 1842 Crispi wrote about the necessity to educate poor people, about the huge damage caused by the excessive wealth of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and regarding the need for all citizens, including women, to be equal before the law.

In 1845 Crispi took up a judgeship in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

,Sarti, ''Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present''pp. 222–23

/ref> where he distinguished himself for his liberal and revolutionary ideas.

1848 Sicilian uprising

On 20 December 1847, Crispi was sent to Palermo along with Salvatore Castiglia, a diplomat and patriot, to prepare the revolution against theBourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

monarchy and King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies.

The

The revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

started on 12 January 1848, and therefore was the very first of the numerous revolutions to occur that year. Three revolutions had previously occurred on the island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

starting from 1800 against Bourbon rule. The uprising was substantially organized from, and centered in, Palermo. The popular nature of the revolt is evident in the fact that posters and notices were being handed out a full three days before the substantive acts of the revolution occurred on 12 January 1848. The timing was deliberately planned, by Crispi and the other revolutionaries, to coincide with the birthday of Ferdinand II.

The Sicilian nobles were immediately able to resuscitate the constitution of 1812, which included the principles of representative democracy and the centrality of Parliament in the government of the state. Vincenzo Fardella was elected president of Sicilian Parliament. The idea was also put forward for a confederation of all the states of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

.

The constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of an Italian confederation of states. Crispi was appointed a member of the provisional Sicilian Parliament and responsible of the Defence Committee; during his tenure he supported the separatist movement that wanted to break ties with Naples.

Thus Sicily survived as a quasi-independent state for sixteen months, with the Bourbon army taking back full control of the island on 15 May 1849 by force. The effective head of state during this period was Ruggero Settimo

Ruggero Settimo (19 May 1778 – 2 May 1863) was an Italian politician, diplomat, and patriotic activist from Sicily. He was a counter-admiral of the Sicilian Fleet. He fought alongside the British fleet in the Mediterranean Sea against the ...

. On capitulating to the Bourbons, Settimo escaped to Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

where he was received with the full honours of a head of state. Unlike many, Crispi was not granted amnesty and was forced to flee the country.Crispi and the ArchpriestThe New York Times, 10 June 1894

Exile

After leaving Sicily, Crispi took refuge inMarseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where he met the woman who would become his second wife, Rose Montmasson

Rose Montmasson (January 12, 1823 – November 10, 1904), also known as Rosalia Montmasson, was an Italian patriot. Born in Savoy, Montmasson contributed to the unification of Italy and was notably the only woman to openly participate in Giusepp ...

, born five years after him in Haute-Savoie (which at that time belonged to the Kingdom of Sardinia) in a family of farmers.

In 1849, he moved to

In 1849, he moved to Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, the capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia, where he worked as a journalist. During this period he became a friend of Giuseppe Mazzini, a republican politician, journalist and activist. In 1853 Crispi was implicated in the Mazzini conspiracy, and was arrested by the Piedmontese policy and sent to Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

. Here, on 27 December 1854 married Rose Montmasson.

Then he moved to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

where he became a revolutionary conspirator and continued his close friendship with Mazzini, involving himself in the exile politics of the national movement, abandoning Sicilian separatism.

On 10 January 1856 he moved to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where he continued his work as journalist. On 22 August, he was informed that his father had died and that three years earlier also his mother had died, but that news had been hidden by his father who did not want to increase his sorrows.

Assassination attempt on Napoleon III

On the evening of 14 January 1858, as the EmperorNapoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

and the Empress Eugénie de Montijo

''Doña'' María Eugenia Ignacia Agustina de Palafox y Kirkpatrick, 19th Countess of Teba, 16th Marchioness of Ardales (5 May 1826 – 11 July 1920), known as Eugénie de Montijo (), was Empress of the French from her marriage to Emperor Napo ...

were on their way to the theatre in the Rue Le Peletier, the precursor of the Opera Garnier

The Palais Garnier (, Garnier Palace), also known as Opéra Garnier (, Garnier Opera), is a 1,979-seatBeauvert 1996, p. 102. opera house at the Place de l'Opéra in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was built for the Paris Opera from ...

, to see, rather ironically, Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

's ''William Tell

William Tell (german: Wilhelm Tell, ; french: Guillaume Tell; it, Guglielmo Tell; rm, Guglielm Tell) is a folk hero of Switzerland.

According to the legend, Tell was an expert mountain climber and marksman with a crossbow who assassinated Albr ...

'', the Italian revolutionary Felice Orsini and his accomplices threw three bombs at the imperial carriage. The first bomb landed among the horsemen in front of the carriage. The second bomb wounded the animals and smashed the carriage glass. The third bomb landed under the carriage and seriously wounded a policeman who was hurrying to protect the occupants. Eight people were killed and 142 wounded, though the emperor and empress were unhurt.

Orsini himself was wounded on the right temple and stunned. He tended his wounds and returned to his lodgings, where police found him the next day.

Of the five conspirators, only one remained unidentified. In 1908 (seven years after Crispi's death) one of them, Charles DeRudio

Charles Camillo DeRudio (born Carlo Camillo Di Rudio; August 26, 1832 – November 1, 1910) was an Italian aristocrat, would-be assassin of Napoleon III, and later a career U.S. Army officer who fought in the 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment at the ...

, claimed to have seen, half an hour before the attack, a man approaching and talking with Orsini, and recognized him as Crispi. But no evidences have never been found regarding Crispi's role in the attack. Anyway on 7 August 1858, he was expelled from France.

In Sicily with Garibaldi

Expedition of the Thousand

In June 1859 Crispi returned to Italy after publishing a letter repudiating the aggrandizement ofPiedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

in the Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

. He proclaimed himself a republican and a partisan of national unity. He travelled around Italy under various disguises and with counterfeit passports. Twice in that year he went the round of the Sicilian cities in disguise preparing the insurrectionist movement of 1860.

He helped persuade

He helped persuade Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

to sail with his Expedition of the Thousand

The Expedition of the Thousand ( it, Spedizione dei Mille) was an event of the Italian Risorgimento that took place in 1860. A corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto, near Genoa (now Quarto dei Mille) and landed in Ma ...

, which disembarked on Sicily on 11 May 1860. The Expedition was formed by corps of volunteers led by Garibaldi, who landed in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

in order to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and a ...

, ruled by the Bourbons

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanish ...

. The project was an ambitious and risky venture aiming to conquer, with a thousand men, a kingdom with a larger regular army and a more powerful navy. The expedition was a success and concluded with a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

that brought Naples and Sicily into the Kingdom of Sardinia, the last territorial conquest before the creation of the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

on 17 March 1861.

The sea venture was the only desired action that was jointly decided by the "four fathers of the nation" Giuseppe Mazzini, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Victor Emmanuel II

Victor Emmanuel II ( it, Vittorio Emanuele II; full name: ''Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia''; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia from 1849 until 17 March 1861, when he assumed the title o ...

, and Camillo Cavour

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (, 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as Cavour ( , ), was an Italian politician, businessman, economist and noble, and a leading figure in the movement towa ...

, pursuing divergent goals. Crispi utilized his political influence to bolster the Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

project.

The various groups participated in the expedition for a variety of reasons: for Garibaldi, it was to achieve a united Italy; to the Sicilian bourgeoisie, an independent Sicily as part of the kingdom of Italy, and for the mass farmers, land distribution and the end of oppression.

Garibaldi dictatorship

After the fall of Palermo, Crispi was appointed First Secretary of State in the provisional government; shortly a struggle began between Garibaldi's government and the emissaries of Cavour on the question of timing of the annexation of Sicily by Italy. It was established a Sicilian Army and a fleet of the Dictatorship Government of Sicily.

The pace of Garibaldi's victories had worried Cavour, who in early July sent to the provisional government a proposal of immediate annexation of Sicily to

After the fall of Palermo, Crispi was appointed First Secretary of State in the provisional government; shortly a struggle began between Garibaldi's government and the emissaries of Cavour on the question of timing of the annexation of Sicily by Italy. It was established a Sicilian Army and a fleet of the Dictatorship Government of Sicily.

The pace of Garibaldi's victories had worried Cavour, who in early July sent to the provisional government a proposal of immediate annexation of Sicily to Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. Garibaldi, however, refused vehemently to allow such a move until the end of the war. Cavour's envoy, Giuseppe La Farina

Giuseppe La Farina (20 July 1815 in Messina – 5 September 1863 in Torino) was an influential leader of the Italian Risorgimento.

He was founder of the Italian National Society in 1857, a society dedicated to the unification of Italy.

Life

H ...

, was arrested and expelled from the island. He was replaced by the more malleable Agostino Depretis

Agostino Depretis (31 January 181329 July 1887) was an Italian statesman and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Italy for several stretches between 1876 and 1887, and was leader of the Historical Left parliamentary group for more than a de ...

, who gained Garibaldi's trust and was appointed as pro-dictator.

During the dictatorial government of Garibaldi, Crispi secured the resignation of the pro-dictator Depretis, and continued his fierce opposition to Cavour.

In Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Garibaldi's provisional government was largely controlled by Cavour. Crispi, who arrived in the city in mid-September, tried to increase his power and influence, at the expense of Cavour's loyalists. However, the revolutionary impulse that had animated the Expedition was fading, especially after the Battle of Volturnus.

On 3 October 1860, to seal an alliance with King Victor Emmanuel II

Victor Emmanuel II ( it, Vittorio Emanuele II; full name: ''Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia''; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia from 1849 until 17 March 1861, when he assumed the title o ...

, Garibaldi appointed pro-dictator of Naples, Giorgio Pallavicino, a supporter of the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

. Pallavicino immediately stated that Crispi was unable and inappropriate to hold the office of Secretary of State.

Meanwhile, Cavour stated that in Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

would not accept anything but the unconditional annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia by plebiscite. Crispi, who still had the hope to continue the revolution to rescue Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, strongly opposed this solution, proposing to elect a parliamentary assembly. This proposal was also supported by the federalist Carlo Cattaneo

Carlo Cattaneo (; 15 June 1801 – 6 February 1869) was an Italian philosopher, writer, and activist, famous for his role in the Five Days of Milan in March 1848, when he led the city council during the rebellion.

Early life

Cattaneo was born i ...

. Garibaldi announced that the decision would have been taken by the two pro-dictators of Sicily and Naples, Antonio Mordini and Giorgio Pallavicino, who both opted for the plebiscite. On 13 October Crispi resigned from the government of Garibaldi.

Member of the Parliament

The general election of 1861 took place on 27 January, even before the formal birth of the

The general election of 1861 took place on 27 January, even before the formal birth of the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, which took place on 17 March. Francesco Crispi was elected as a member of the Historical Left

The Left group ( it, Sinistra), later called Historical Left ( it, Sinistra storica) by historians to distinguish it from the left-wing groups of the 20th century, was a liberal and reformist parliamentary group in Italy during the second half of ...

, in the constituency of Castelvetrano; he would retain his seat in all successive legislatures until the end of his life.

Crispi acquired the reputation of being the most aggressive and most impetuous member of his parliamentary group. He denounced the Right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of Liberty, freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convent ...

for "diplomatising the revolution".Seton-Watson, ''Italy from liberalism to fascism'', p. 47 Personal ambition and restlessness made him difficult to cooperate with and he earned himself the nickname of ''Il Solitario'' (The Loner). In 1864, he finally deserted Mazzini and announced he was a monarchist, because as he put it in a letter to Mazzini: "The monarchy unites us; the republic would divide us."

In 1866 he refused to enter Baron Bettino Ricasoli's cabinet; in 1867 he worked to impede the Garibaldian invasion of the papal states, foreseeing the French occupation of Rome and the disaster of Mentana

Mentana is a town and ''comune'', former bishopric and present Latin Catholic titular see in the Metropolitan City of Rome, Lazio, central Italy. It is located north-east of Rome and has a population of about 23,000.

History

Mentana's name in ...

. By methods of the same character as those subsequently employed against himself by Felice Cavallotti

Felice Cavallotti (6 November 1842 – 6 March 1898) was an Italian politician, poet and dramatic author.

Biography

Early career

Born in Milan, Cavallotti fought with the Garibaldian Corps in their 1860 and 1866 campaigns during the Italian ...

, he carried on the violent agitation known as the Lobbia affair, in which sundry conservative deputies were, on insufficient grounds, accused of corruption. On the outbreak of the Franco-German War he worked energetically to impede the projected alliance with France, and to drive the Giovanni Lanza cabinet to Rome. The death of Urbano Rattazzi

Urbano Pio Francesco Rattazzi (; 29 June 1808 5 June 1873) was an Italian statesman.

Personal life

He was born in Alessandria (Piedmont). He studied law at Turin, and in 1838 began his practice, which met with marked success at the capital and ...

in 1873 induced Crispi's friends to put forward his candidature to the leadership of the Left; but Crispi, anxious to reassure the crown, secured the election of Agostino Depretis

Agostino Depretis (31 January 181329 July 1887) was an Italian statesman and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Italy for several stretches between 1876 and 1887, and was leader of the Historical Left parliamentary group for more than a de ...

.

President of the Chamber of Deputies

After the general election in 1876, in which the Left gained almost 70% of votes, Crispi was electedPresident of the Chamber of Deputies President of the Chamber of Deputies may refer to:

* List of presidents of the Argentine Chamber of Deputies

* List of presidents of the Chamber of Deputies of Bolivia

* President of the Chamber of Deputies (Brazil)

* President of the Chamber of Dep ...

.

During the autumn of 1877, as President of the Chamber, he went to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

on a confidential mission, establishing cordial personal relationships with British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

and Foreign Minister Lord Granville

Earl Granville is a title that has been created twice, once in the Peerage of Great Britain and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It is now held by members of the Leveson-Gower family.

First creation

The first creation came in the Pee ...

and other English statesmen, and with Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, by then Chancellor of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

. In 1877 during the Great Eastern Crisis

The Great Eastern Crisis of 1875–78 began in the Ottoman Empire's territories on the Balkan peninsula in 1875, with the outbreak of several uprisings and wars that resulted in the intervention of international powers, and was ended with the T ...

Crispi was offered Albania as possible compensation by Bismarck and the British Earl of Derby if Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and He ...

, however he refused and preferred the Italian Alpine regions under Austro-Hungarian rule.

Minister of the Interior

In December 1877 he replaced

In December 1877 he replaced Giovanni Nicotera

Giovanni Nicotera (9 September 1828 – 13 June 1894) was an Italian patriot and politician. His surname is pronounced , with the stress on the second syllable.

Biography

Nicotera was born at Sambiase, in Calabria, in the Kingdom of the Two Si ...

as Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

in the cabinet of Depretis. Although his short term of office lasted just 70 days, they were instrumental in establishing a unitary monarchy. Moreover, during his term as minister, Crispi tried to unite the many factions which were part of the Left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

, at that time.

On 9 January 1878, the death of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

en, Victor Emmanuel Maria Albert Eugene Ferdinand Thomas

, house = Savoy

, father = Charles Albert of Sardinia

, mother = Maria Theresa of Austria

, religion = Roman Catholicism

, image_size = 252px

, succession1 ...

and the accession of King Umberto enabled Crispi to secure the formal establishment of a unitary monarchy, the new monarch taking the title of Umberto I of Italy

Umberto I ( it, Umberto Rainerio Carlo Emanuele Giovanni Maria Ferdinando Eugenio di Savoia; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900) was King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his assassination on 29 July 1900.

Umberto's reign saw Italy attempt colo ...

instead of Umberto IV of Savoy.

On 7 February 1878, the death of Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

necessitated a conclave, the first to be held after the unification of Italy. Crispi, helped by Mancini and Cardinal Pecci (afterwards Leo XIII), persuaded the Sacred College

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are appoi ...

to hold the conclave in Rome, establishing the legitimacy of the capital.

Bigamy scandal and political isolation

The statesmanlike qualities displayed on this occasion were insufficient to avert the storm of indignation of Crispi's opponents when he was accused ofbigamy

In cultures where monogamy is mandated, bigamy is the act of entering into a marriage with one person while still legally married to another. A legal or de facto separation of the couple does not alter their marital status as married persons. I ...

. When he remarried, a woman he had married in 1853 was still living. But a court ruled that Crispi's 1853 marriage on Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

was invalid because it was contracted while another woman he had married yet earlier was also still alive. By the time of his third marriage, his first wife had died and his marriage to his second wife was legally invalid. Therefore, his marriage to his third wife was ruled valid and not bigamous. He was nevertheless compelled to resign office after only three months in March 1878, bringing down the whole government with him.

For nine years Crispi remained politically under a cloud, leading the "progressive" opposition. In 1881 Crispi was among the main supporters of the universal male suffrage, which was approved by the government of

For nine years Crispi remained politically under a cloud, leading the "progressive" opposition. In 1881 Crispi was among the main supporters of the universal male suffrage, which was approved by the government of Agostino Depretis

Agostino Depretis (31 January 181329 July 1887) was an Italian statesman and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Italy for several stretches between 1876 and 1887, and was leader of the Historical Left parliamentary group for more than a de ...

.

Pentarchy

In 1883 the leaders of the Left, Agostino Depretis, and the Right,Marco Minghetti

Marco Minghetti (18 November 1818 – 10 December 1886) was an Italian economist and statesman.

Biography

Minghetti was born at Bologna, then part of the Papal States.

He signed the petition to the Papal conclave, 1846, urging the electio ...

, formed an alliance based on flexible centrist

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to the l ...

coalition of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

which isolated the extremes of the left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

and the right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of Liberty, freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convent ...

; this politics was known as ''Trasformismo

''Trasformismo'' is the method of making a flexible centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the political left and the political right in Italian politics after the Italian unification and before the rise of Benito Mussoli ...

''. Crispi, who was a strong supporter of two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually referre ...

, strongly opposed it and founded a progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

and radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

parliamentary group called Dissident Left

The Dissident Left ( it, Sinistra dissidente), commonly named The Pentarchy ( it, La Pentarchia) for its five leaders, was a progressive and radical parliamentary group active in Italy during the last decades of the 19th century.

History

It eme ...

. The group was also known as "The Pentarchy", due to its five leaders, Giuseppe Zanardelli, Benedetto Cairoli

Benedetto Cairoli (28 January 1825 – 8 August 1889) was an Italian politician.

Biography

Cairoli was born at Pavia, Lombardy. From 1848 until the completion of Italian unity in 1870, his whole activity was devoted to the ''Risorgimento'', as ...

, Giovanni Nicotera

Giovanni Nicotera (9 September 1828 – 13 June 1894) was an Italian patriot and politician. His surname is pronounced , with the stress on the second syllable.

Biography

Nicotera was born at Sambiase, in Calabria, in the Kingdom of the Two Si ...

, Agostino Magliani

Agostino Magliani (23 July 182420 February 1891), Italian financier, was a native of Laurino, near Salerno.

He studied at Naples, and a book on the philosophy of law based on Liberal principles won for him a post in the Neapolitan treasury. He ...

, Alfredo Beccarini and Crispi.

The party supported authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

and progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

internal policies, expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

and Germanophile foreign policies, and protectionist economy policies.

After the general elections in May 1886, in which the Dissident Left gained almost 20% of votes, Crispi returned to office as Minister of the Interior in the Depretis cabinet. Following Depretis's death on 29 July 1887 Crispi, abandoned the Dissident Left and became the leader of the Left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

group; he was also appointed, by the King, Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

and Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

.

First term as Prime Minister

On 29 July 1887, Francesco Crispi sworn in as new Prime Minister. He was the first one fromSouthern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

. Crispi immediately distinguished himself, for being a reformist leader, but his political style provoked many protests from his opponents, who accused him of being an authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

Prime Minister and a strongman.

True to his initial progressive leanings he moved ahead with stalled reforms, abolishing the death penalty, revoking anti-strike laws, limiting police powers, reforming the penal code and the administration of justice with the help of his Minister of Justice Giuseppe Zanardelli, reorganising charities and passing public health laws and legislation to protect emigrants that worked abroad. He sought popular support for the state with a programme of orderly development at home and expansion abroad.Sarti, ''Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present''

True to his initial progressive leanings he moved ahead with stalled reforms, abolishing the death penalty, revoking anti-strike laws, limiting police powers, reforming the penal code and the administration of justice with the help of his Minister of Justice Giuseppe Zanardelli, reorganising charities and passing public health laws and legislation to protect emigrants that worked abroad. He sought popular support for the state with a programme of orderly development at home and expansion abroad.Sarti, ''Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present''pp. 43–44

/ref>Seton-Watson, ''Italy from liberalism to fascism'', p. 131

Internal policy

One of the most important acts was the reform regarding the central administration of the State, with which Crispi strengthened the role of the Prime Minister. The bill aimed to separate the roles of the government from those of parliament, trying to untie the first by the political games of the second. The first point of the law was to give the cabinet the right to decide on the number and functions of the ministries. The prospect was also to keep the King (as well as provided the Albertine Statute) free to decide on the organization of the various ministries. Moreover, the reform provided the establishment of the secretaries, who were supposed to help ministers and, at the same time, do them as spokesmen in parliament. The reform was heavily criticized by theRightist

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, auth ...

opposition but also by the Far Left. On 9 December 1887 it was approved by the Chamber of Deputies.

In 1889 Crispi's government promoted a reform of the magistracy and promulgated a new penal code, which unified penal legislation in Italy, abolished death sentence and recognised the right to strike. The code was regarded as a great work by contemporary European jurists. The code was named after Giuseppe Zanardelli, then Minister of Justice, who promoted the approval of the code.

Another important reform was that of local government, or '' comuni'', which was approved by the Chamber in July 1888, in just three weeks. The new reform almost doubled the local electorate, incrementing the suffrage. But the most controversial part of the law was related to the mayors, who were previously appointed by the government, and who would now elected by the electors, in the municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants and in all the provincial capitals. The law also introduced the office of the prefect. The reform was approved by the Senate in December 1888 and entered into force in February 1889.

On 22 December 1888, the Freemason Crispi enacted the first Italian law for the national healthcare system including the

In 1889 Crispi's government promoted a reform of the magistracy and promulgated a new penal code, which unified penal legislation in Italy, abolished death sentence and recognised the right to strike. The code was regarded as a great work by contemporary European jurists. The code was named after Giuseppe Zanardelli, then Minister of Justice, who promoted the approval of the code.

Another important reform was that of local government, or '' comuni'', which was approved by the Chamber in July 1888, in just three weeks. The new reform almost doubled the local electorate, incrementing the suffrage. But the most controversial part of the law was related to the mayors, who were previously appointed by the government, and who would now elected by the electors, in the municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants and in all the provincial capitals. The law also introduced the office of the prefect. The reform was approved by the Senate in December 1888 and entered into force in February 1889.

On 22 December 1888, the Freemason Crispi enacted the first Italian law for the national healthcare system including the cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a Cadaver, dead body through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India ...

after the colera pandemies of 1835–37, 1854–55 and 1856–67 which had caused the death of more than 160,000 people. Crispi was also the first politician to have implemented the role of the Italian lay state in the fields of charity and solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

which till then had been traditionally kept a monopoly of private citizens and organizations, mainly of the Italian Roman Catholic Church that strongly adversed his reforms.

Foreign policy

As prime minister in the 1880s and 1890s Crispi pursued an aggressive foreign policy to strengthen Italy's beleaguered institutions. He saw France as the permanent enemy and he counted heavily on British support. Britain was on good terms with France and refused to help, leaving Crispi perplexed and ultimately disillusioned about what he had felt was a special friendship between the two countries. He turned to imperialism in Africa, especially against the independent kingdom of Ethiopia, and Ottoman province ofTripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

(in present-day Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

).

Relations with Germany

One of his first acts as premier was a visit to the German chancellor

One of his first acts as premier was a visit to the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, whom he desired to consult upon the working of the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

.

Basing his foreign policy upon the alliance, as supplemented by the naval entente with Great Britain negotiated by his predecessor, Carlo Felice Nicolis di Robilant, Crispi assumed a resolute attitude towards France, breaking off the prolonged and unfruitful negotiations for a new Franco-Italian commercial treaty, and refusing the French invitation to organize an Italian section at the Paris Exhibition of 1889

The Exposition Universelle of 1889 () was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 5 May to 31 October 1889. It was the fourth of eight expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937. It attracted more than thirty-two million visitors. The ...

. The Triple Alliance committed Italy to a possible war with France, requiring a vast increase in the already heavy Italian military expenditure, making the alliance unpopular in Italy. As part of his anti-French foreign policy, Crispi began a tariff war with France in 1888. The Franco-Italian trade war was an economic disaster for Italy which over a ten-year period was to cost two billion lire in lost exports, and was ended in 1898 with the Italians agreeing to end their tariffs on French goods in exchange for the French ending their tariffs on Italian goods.

Colonial policy

Francesco Crispi was a patriot and anItalian nationalist

Italian nationalism is a movement which believes that the Italians are a nation with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness is ...

, and his desire to make Italy a colonial power led to conflicts with France, which rejected Italian claims to Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and opposed Italian expansion elsewhere in Africa.

Under Crispi's rule, Italy signed the Treaty of Wuchale; it was a deal reached by King Menelik II of Shewa

Shewa ( am, ሸዋ; , om, Shawaa), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa (''Scioà'' in Italian language, Italian), is a historical region of Ethiopia which was formerly an autonomous monarchy, kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The ...

, later the Emperor of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

with Count Pietro Antonelli in the town of Wuchale

Wuchale ( Amharic: ውጫሌ), also spelled Uccialli, is a town in northern Ethiopia. Located about 40 km north of Dessie in the Debub Wollo Zone of the Amhara Region, this town has a latitude and longitude of and an elevation of 1711 m. I ...

, on 2 May 1889. The treaty stated that the regions of Bogos, Hamasien, Akkele Guzay

The Provinces of Eritrea existed between Eritrea's incorporation as a colony of Italy until the conversion of the provinces into administrative regions.

Overview

In Italian Eritrea, the Italian colonial administration had divided the colony into ...

, and Serae

The Provinces of Eritrea existed between Eritrea's incorporation as a colony of Italy until the conversion of the provinces into administrative regions.

Overview

In Italian Eritrea, the Italian colonial administration had divided the colony into e ...

were part of the Italian colony of Eritrea and is the origin of the Italian colony and modern state of Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

. Per the Treaty, Italy promised financial assistance and military supplies.

Albanian question

Balkan geopolitics and security concerns drove Italy to seek great power status in the Adriatic sea and Crispi viewed a future autonomous Albania within the Ottoman Empire or as an independent country being a safeguarded for Italian interests. Crispi regarded Albania's interests against Pan-Slavism and possible Austro-Hungarian invasion were best served through a Greco-Albanian union and he founded in Rome aphilhellenic

Philhellenism ("the love of Greek culture") was an intellectual movement prominent mostly at the turn of the 19th century. It contributed to the sentiments that led Europeans such as Lord Byron and Charles Nicolas Fabvier to advocate for Greek i ...

committee that worked toward that goal. Crispi, after becoming prime minister, stimulated and intensified ethno-cultural relations between Italo-Albanians and Albanians of the Balkans, moves which were considered as extending Italian influence over Albanians by Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. To counteract Austro-Hungarian influence in northern Albania, Crispi took the initiative and opened the first Italian schools in Shkodër

Shkodër ( , ; sq-definite, Shkodra) is the fifth-most-populous city of the Republic of Albania and the seat of Shkodër County and Shkodër Municipality. The city sprawls across the Plain of Mbishkodra between the southern part of Lake Shkod ...

in 1888. Prominent Albanians involved with the Albanian National Awakening

The Albanian National Awakening ( sq, Rilindja or ), commonly known as the Albanian Renaissance or Albanian Revival, is a period throughout the 19th and 20th century of a cultural, political and social movement in the Albanian history where the ...

such as Abdyl Frashëri

Abdyl Dume bey Frashëri ( tr, Fraşerli Abdül Bey; 1 June 1839 – 23 October 1892) was an Ottoman Albanian civil servant, politician during the First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire, and one of the first Albanian political ideologues ...

and Thimi Mitko

Thimi (Euthimio) Mitko (1820 – March 22, 1890) was an activist of the Albanian National Awakening and folklorist.

Mitko was born in Korçë, Albania (then Ottoman Empire), where he attended the local Greek school. His uncle, Peti Mitko, ...

corresponded with Crispi over the Albanian question.

Resignation

The general election in 1890 was an extraordinary triumph for Crispi. Out of 508 deputies, 405 sided with the government. But already in October, the first signs of a political crisis grew up. The Emperor Menelik had contested the Italian text of the Wuchale Treaty, stating that it did not oblige Ethiopia to be an Italian protectorate. Menelik informed the foreign press and the scandal erupted. Few days after the Finance Minister and Crispi's long-time main political rival,Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. After Benito Mussolini, he is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history. A pr ...

, abandoned the government.

However, the decisive event was a document published by the new Minister of Finance Bernardino Grimaldi, who revealed that the planned deficit was higher than expected; after that, the government lost his majority with 186 votes against and 123 in favor. Prime Minister Crispi resigned on 6 February 1891.

After the premiership

After fall of Crispi's government, Umberto I gave the task of forming the new cabinet to the MarquisAntonio Starabba di Rudinì

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular male ...

. The government faced many difficulties since the beginning and in May 1892, Giolitti, who became the new Left leader after Crispi's resignation, decided not to support it anymore.

After that, King Umberto I, appointed Giolitti as new Prime Minister. The first Giolitti cabinet, however, relied on a slender majority and in December 1892 the Prime Minister was involved in a major scandal.

Banca Romana scandal

TheBanca Romana scandal