Coronations in Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

: ''Note: this article is one of a set, describing coronations around the world.''

: ''For general information related to all coronations, please see the umbrella article

Coronations in Europe were previously held in the monarchies of Europe. The United Kingdom is the only monarchy in Europe that still practices coronation. Current European monarchies have either replaced coronations with simpler ceremonies to mark an accession (e.g. Denmark) or have never practiced coronations (e.g. The Netherlands and Belgium). Most monarchies today only require a simple oath to be taken in the presence of the country's legislature.

Coronations in Europe were previously held in the monarchies of Europe. The United Kingdom is the only monarchy in Europe that still practices coronation. Current European monarchies have either replaced coronations with simpler ceremonies to mark an accession (e.g. Denmark) or have never practiced coronations (e.g. The Netherlands and Belgium). Most monarchies today only require a simple oath to be taken in the presence of the country's legislature.

According to legend, the first crowned monarch of Croatia was

According to legend, the first crowned monarch of Croatia was

Following perhaps the Byzantine or Visigothic formula, the French coronation ceremony called ''Sacre'' primarily included the

Following perhaps the Byzantine or Visigothic formula, the French coronation ceremony called ''Sacre'' primarily included the  During the

During the

Since

Since

The Holy Roman Empire: Introduction

. From th

Almanach de la Cour

website. Retrieved on 14 September 2008. Later rulers simply proclaimed themselves ''Electus Romanorum Imperator'' or "Elected Emperor of the Romans", without the formality of a coronation by the Pontiff. Coronations were held in Rome (under the pope),

Rulers of Hungary were not considered legitimate monarchs until they were crowned King of Hungary with the

Rulers of Hungary were not considered legitimate monarchs until they were crowned King of Hungary with the

In 1646, immediately after his Coronation, King João IV of Portugal and the Algarves consecrated the Crown of Portugal to the

In 1646, immediately after his Coronation, King João IV of Portugal and the Algarves consecrated the Crown of Portugal to the

The

The

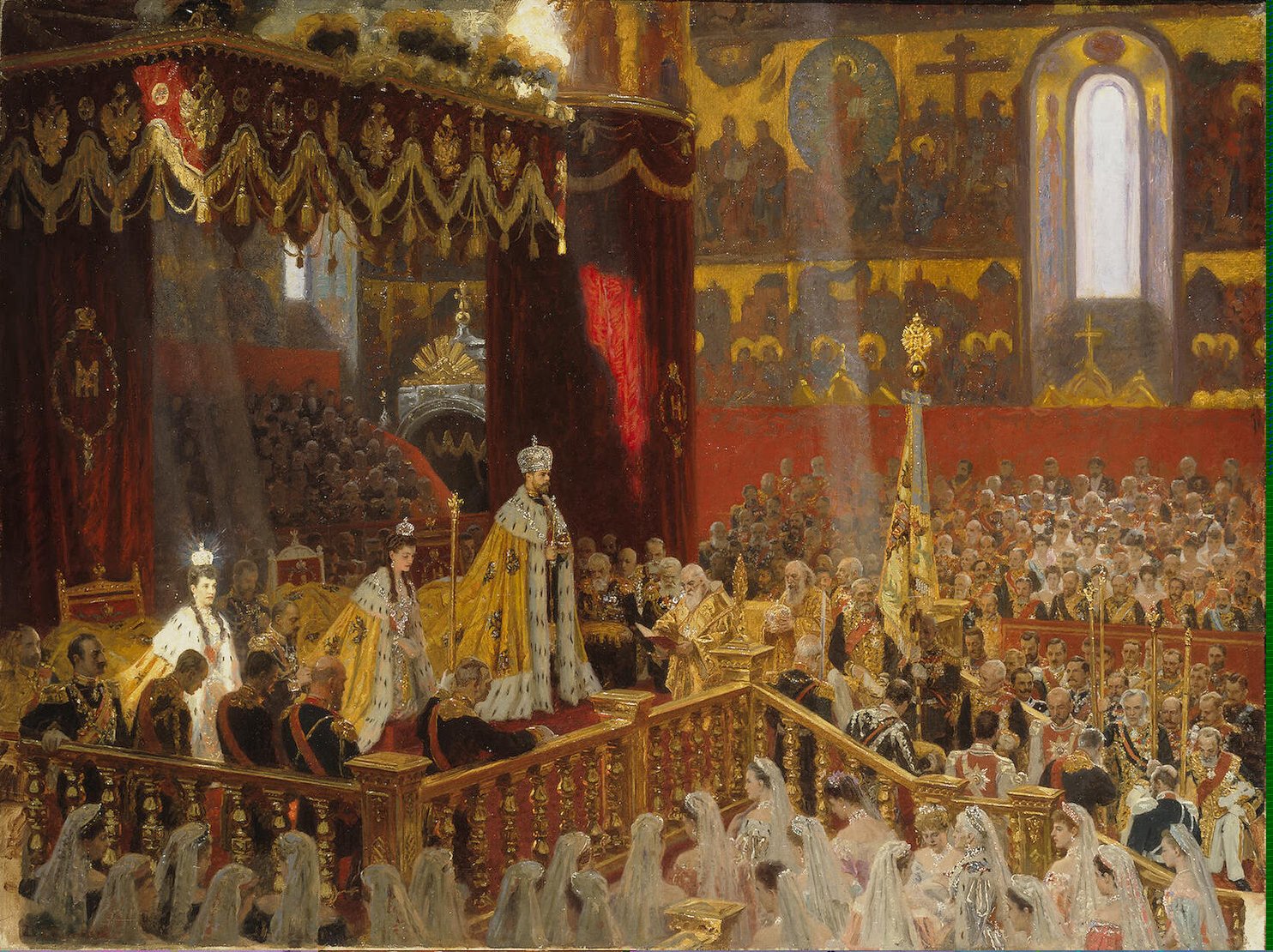

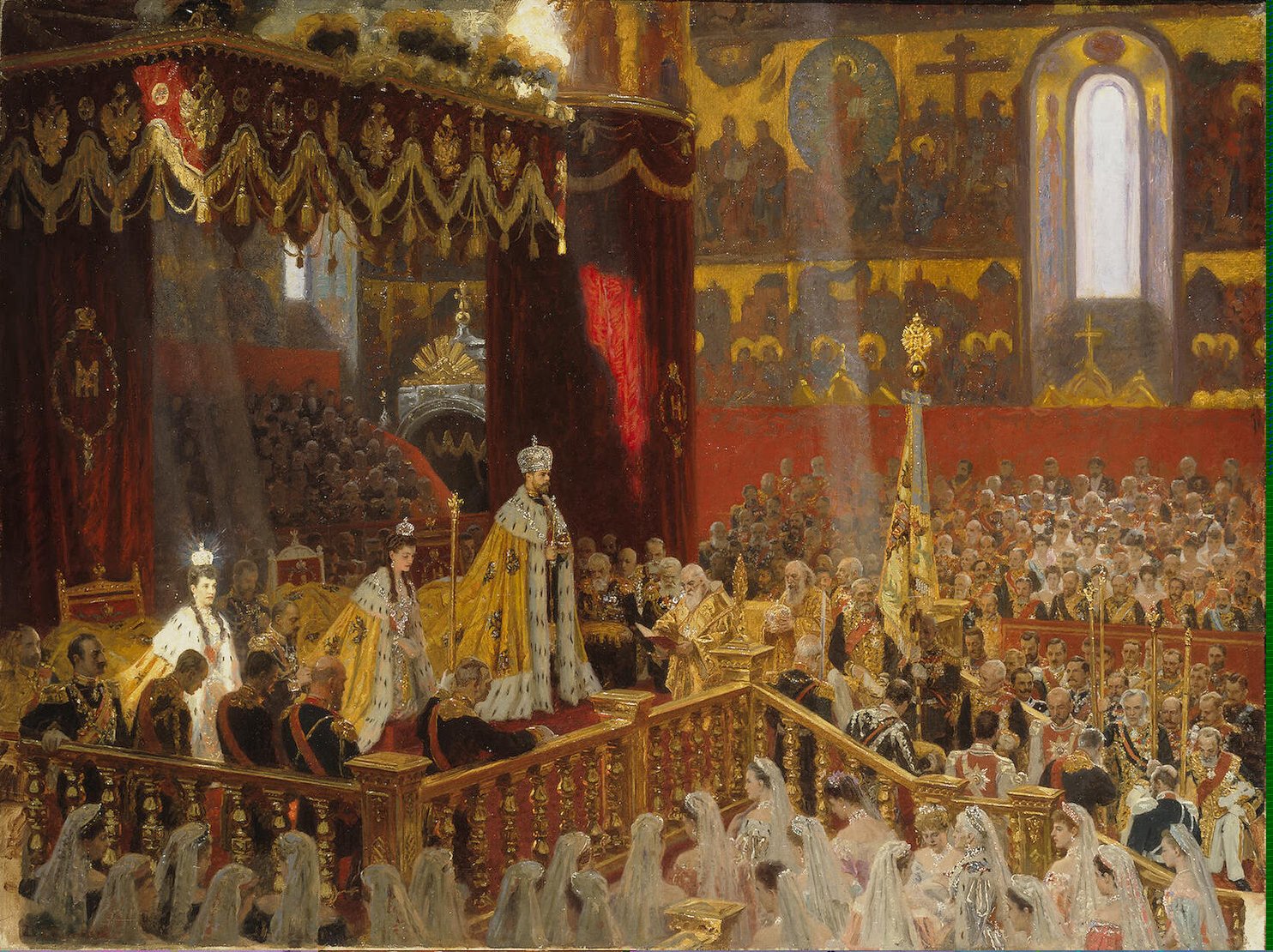

. Retrieved on 2009-12-31. After the Tsar entered the cathedral, he and his spouse venerated the

Kings of

Kings of

Swedish monarchs were crowned in various cities during the 13th and 14th centuries, but from the middle of the 15th century on in either the Uppsala Cathedral, Cathedral in Uppsala or Storkyrkan in Stockholm, with the exception of the coronation of Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden, Gustav IV Adolf, which took place in Norrköping in 1800. Earlier coronations were also held at Uppsala, the ecclesiastical center of Sweden. Prior to Sweden's change into a hereditary monarchy, the focus of the coronation rite was on legitimising an elected king.

Nineteenth-century coronations of Swedish monarchs followed a rite last used during the coronation of Oscar II of Sweden, Oscar II in 1873:

The king and queen proceeded to the Cathedral in separate processions. The king was met at the front portal by the Archbishop of Uppsala, highest prelate in the Church of Sweden, together with other bishops in their copes. The Archbishop greeted the king: "Blessed be he who cometh in the Name of the Lord", while the Bishop of Skara said a prayer that the king might be endowed with the grace to govern his people well. The Archbishop and bishops then escorted the king to his seat on the right-hand side of the choir, with the Royal Standard on his right side and the banner of the Order of the Seraphim on his left.

The Bishop of Strängnäs and the rest of the bishops then awaited the approach of the queen; when she arrived the Bishop of Strängnäs greeted her with: "Blessed is she who cometh in the Name of the Lord", while the Bishop of Härnösand said a prayer virtually identical to the one previously said for the king. The Bishop of Strängnäs and the other bishops then escorted the queen to her seat on the left hand side of the choir where the king and queen both knelt for a few moments of private prayer while the regalia were deposited upon the altar.

The Archbishop began the service by singing: "Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Sabaoth", the normal beginning of the Swedish High Mass. The Bishop of Skara recited the Creed before the altar and the hymn "Come, thou Holy Spirit, come" was sung. The Litany of the Saints, Litany and then an anthem were sung during which the king went to his throne on a dais before the altar with the Royal Standard being borne on his right and the banner of the Order of the Seraphim on his left. Following this, the Regalia was brought forward. The king's mantle and Crown Prince's coronet were removed and placed on the altar, and the kneeling king was vested in the Royal Mantle by a state minister while the Archbishop read the first chapter of the Gospel of St. John. The Minister of Justice recited the oath to the king, which he took while laying three fingers on the Bible.

Following this, the Archbishop anointed the king on his forehead, breast, temples and wrists, saying:

Swedish monarchs were crowned in various cities during the 13th and 14th centuries, but from the middle of the 15th century on in either the Uppsala Cathedral, Cathedral in Uppsala or Storkyrkan in Stockholm, with the exception of the coronation of Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden, Gustav IV Adolf, which took place in Norrköping in 1800. Earlier coronations were also held at Uppsala, the ecclesiastical center of Sweden. Prior to Sweden's change into a hereditary monarchy, the focus of the coronation rite was on legitimising an elected king.

Nineteenth-century coronations of Swedish monarchs followed a rite last used during the coronation of Oscar II of Sweden, Oscar II in 1873:

The king and queen proceeded to the Cathedral in separate processions. The king was met at the front portal by the Archbishop of Uppsala, highest prelate in the Church of Sweden, together with other bishops in their copes. The Archbishop greeted the king: "Blessed be he who cometh in the Name of the Lord", while the Bishop of Skara said a prayer that the king might be endowed with the grace to govern his people well. The Archbishop and bishops then escorted the king to his seat on the right-hand side of the choir, with the Royal Standard on his right side and the banner of the Order of the Seraphim on his left.

The Bishop of Strängnäs and the rest of the bishops then awaited the approach of the queen; when she arrived the Bishop of Strängnäs greeted her with: "Blessed is she who cometh in the Name of the Lord", while the Bishop of Härnösand said a prayer virtually identical to the one previously said for the king. The Bishop of Strängnäs and the other bishops then escorted the queen to her seat on the left hand side of the choir where the king and queen both knelt for a few moments of private prayer while the regalia were deposited upon the altar.

The Archbishop began the service by singing: "Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Sabaoth", the normal beginning of the Swedish High Mass. The Bishop of Skara recited the Creed before the altar and the hymn "Come, thou Holy Spirit, come" was sung. The Litany of the Saints, Litany and then an anthem were sung during which the king went to his throne on a dais before the altar with the Royal Standard being borne on his right and the banner of the Order of the Seraphim on his left. Following this, the Regalia was brought forward. The king's mantle and Crown Prince's coronet were removed and placed on the altar, and the kneeling king was vested in the Royal Mantle by a state minister while the Archbishop read the first chapter of the Gospel of St. John. The Minister of Justice recited the oath to the king, which he took while laying three fingers on the Bible.

Following this, the Archbishop anointed the king on his forehead, breast, temples and wrists, saying:

The United Kingdom is the only country in Europe that still practises coronations. All other countries have either become republics, never practiced coronations, or replaced the coronation with an inauguration ceremony.

The Coronation of the British monarch takes place in

The United Kingdom is the only country in Europe that still practises coronations. All other countries have either become republics, never practiced coronations, or replaced the coronation with an inauguration ceremony.

The Coronation of the British monarch takes place in

Enthronements in Royal Europe: 1964-2000

Contains details and photos of several recent European enthronements.

Contains video from Consecration of Olav V of Norway.

A Queen Is Crowned

Coronation of Elizabeth II of Great Britain in 1953, in seven parts.

Coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

.''

Coronations in Europe were previously held in the monarchies of Europe. The United Kingdom is the only monarchy in Europe that still practices coronation. Current European monarchies have either replaced coronations with simpler ceremonies to mark an accession (e.g. Denmark) or have never practiced coronations (e.g. The Netherlands and Belgium). Most monarchies today only require a simple oath to be taken in the presence of the country's legislature.

Coronations in Europe were previously held in the monarchies of Europe. The United Kingdom is the only monarchy in Europe that still practices coronation. Current European monarchies have either replaced coronations with simpler ceremonies to mark an accession (e.g. Denmark) or have never practiced coronations (e.g. The Netherlands and Belgium). Most monarchies today only require a simple oath to be taken in the presence of the country's legislature.

By country

Albania

KingZog I

Zog I ( sq, Naltmadhnija e tij Zogu I, Mbreti i Shqiptarëve, ; 8 October 18959 April 1961), born Ahmed Muhtar bey Zogolli, taking the name Ahmet Zogu in 1922, was the leader of Albania from 1922 to 1939. At age 27, he first served as Albania's ...

, self-proclaimed monarch of Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

, was ritually crowned on 1 September 1928. His coronation attire included rose-colored breeches, gold spurs, and a gold crown weighing . Europe's only Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

king swore a required constitutional oath on the Bible and the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

, symbolizing his desire to unify his country. Zog was forced into exile by Italian invaders in 1939, and the monarchy was formally abolished in 1945.

Austria

Emperors of Austria

The Emperor of Austria (german: Kaiser von Österreich) was the ruler of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A hereditary imperial title and office proclaimed in 1804 by Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, a member of the Hous ...

were never crowned (unlike their predecessors in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

), as a coronation was not viewed as being necessary to legitimize their rule in that country.

However, they were crowned in some kingdoms within the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

. Ferdinand I was crowned as King of Hungary

The King of Hungary ( hu, magyar király) was the ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Apostoli Magyar Király'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

with the Crown of Saint Stephen

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( hu, Szent Korona; sh, Kruna svetoga Stjepana; la, Sacra Corona; sk, Svätoštefanská koruna , la, Sacra Corona), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the ...

in 1830, as King of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings beforehand, first gaining the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman ...

with the Crown of Saint Wenceslas

The crown of Saint Wenceslas ( cs, Svatováclavská koruna, german: Wenzelskrone) is a crown forming part of the Bohemian crown jewels, made in 1346. Charles IV, king of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, had it made for his coronation, dedicating it ...

in 1836, and as King of Lombardy and Venetia with the Iron Crown of Lombardy

The Iron Crown ( lmo, Corona Ferrea de Lombardia; it, Corona Ferrea; la, Corona Ferrea) is a relic and may be one of the oldest royal insignia of Christendom. It was made in the Early Middle Ages, consisting of a circlet of gold and jewels fit ...

in 1838.

After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (german: Ausgleich, hu, Kiegyezés) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hungary ...

, the Emperors of Austria were only crowned as King of Hungary (again with the Crown of Saint Stephen): Franz-Joseph I in 1867 and Charles I (as Charles IV of Hungary) in 1916.

Bavaria

In 1806, theGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a Middle Ages, medieval country, territory, fiefdom, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or Queen regnant, queen in Western European tradition.

There once exis ...

of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

was upgraded to full "kingdom" status. The former ''Duke of Bavaria'', who now became King of Bavaria

King of Bavaria was a title held by the hereditary Wittelsbach rulers of Bavaria in the state known as the Kingdom of Bavaria from 1805 until 1918, when the kingdom was abolished. It was the second time Bavaria was a kingdom, almost a thousand ...

, Maximilian I, commissioned a set of crown jewels to commemorate Bavaria's elevation. However, there was no coronation ceremony, and the king never wore the crown in public. Rather, it was placed on a cushion at his feet when displayed on occasions. The Bavarian monarchy was abolished in 1918.

Belgium

Following theBelgian Revolution

The Belgian Revolution (, ) was the conflict which led to the secession of the southern provinces (mainly the former Southern Netherlands) from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

T ...

from 1830 to 1831 and the subsequent establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands ( nl, Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden; french: Royaume uni des Pays-Bas) is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed between 1815 and 1839. The United Netherlands was cr ...

, Leopold I and his successors have never been crowned in a coronation rite. Belgium has no regalia such as crowns (except as a heraldic emblem); the monarch's formal installation requires only a solemn oath to "abide by the Constitution and the laws of the Belgian people, maintain the country’s independence and preserve its territory" before members of the two chambers of parliament.

During the enthronement of Baudouin, one legislator, Julien Lahaut

Julien Lahaut (6 September 1884 – 18 August 1950) was a Belgian politician and communist activist. He became leader of the Communist Party of Belgium after the First World War. A dissident during the German occupation of 1940–44, he became ...

, cried "Vive la République", only to be shouted down by others, who cried "Vive le Roi", with the entire chamber rising to applaud the king. Lahaut was found dead a week later. During the enthronement of Albert II, legislator Jean-Pierre Van Rossem

Jean-Pierre Van Rossem (29 May 1945 – 13 December 2018) was a Belgian stock market guru, economist, econometrician, convicted fraudster, author, philosopher, public figure, politician, and member of the Belgian and Flemish Parliaments.

Life ...

cried "Leve de republiek, Vive la république européenne, Vive Lahaut!" Van Rossem was also shouted down by the others, but did not suffer the same fate as Lahaut.

Bohemia

Vratislaus II of Bohemia

Vratislaus II (or Wratislaus II) ( cs, Vratislav II.) (c. 1032 – 14 January 1092), the son of Bretislaus I and Judith of Schweinfurt, was the first King of Bohemia as of 15 June 1085, his royal title granted as a lifetime honorific from Holy R ...

was the first crowned ruler of Bohemia. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, it was held that enthronement would make a person Duke of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings beforehand, first gaining the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman ...

and that only coronation would make a person King of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings beforehand, first gaining the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman ...

.Lisa Wolverton, ''Hastening Toward Prague: Power and Society in the Medieval Czech Lands'', University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001 St. Vitus Cathedral

, native_name_lang = Czech

, image = St Vitus Prague September 2016-21.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, imagelink =

, imagealt =

, landscape =

, caption ...

was the coronation church. Monarchs of Bohemia were crowned with the Crown of Saint Wenceslas

The crown of Saint Wenceslas ( cs, Svatováclavská koruna, german: Wenzelskrone) is a crown forming part of the Bohemian crown jewels, made in 1346. Charles IV, king of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, had it made for his coronation, dedicating it ...

and invested with royal insignia, among which a cap or mitre and a lance (symbols of Saint Wenceslas

Wenceslaus I ( cs, Václav ; c. 907 – 28 September 935 or 929), Wenceslas I or ''Václav the Good'' was the Duke ('' kníže'') of Bohemia from 921 until his death, probably in 935. According to the legend, he was assassinated by his younger ...

) were specific for Bohemian coronations.

Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

, the only female monarch of Bohemia, was crowned king in order to emphasize that she was the monarch and not consort. The last King of Bohemia to be crowned as such was Emperor Ferdinand of Austria.

The Abbess of the St. George's Abbey had the privilege to crown the wife of the King of Bohemia.''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1913 In 1791, the right to crown the Queen of Bohemia was transferred to the Abbess of

the Damenstift

The term (; nl, sticht) is derived from the verb (to donate) and originally meant 'a donation'. Such donations usually comprised earning assets, originally landed estates with serfs defraying dues (originally often in kind) or with vassal tenan ...

or Theresian Institution of Noble Ladies

The Theresian Institution of Noble Ladies, officially the Imperial and Royal Theresian Stift for Noble Ladies in the Castle of Prague, was a Catholic monastic chapter of secular canonesses in Hradčany that admitted women from impoverished nobl ...

(a post always filled by an Archduchess of Austria).

Bosnia

The first crowned ruler ofBosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and He ...

was Tvrtko I

Stephen Tvrtko I ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Stjepan/Stefan Tvrtko, Стјепан/Стефан Твртко; 1338 – 10 March 1391) was the first king of Bosnia. A member of the House of Kotromanić, he succeeded his uncle Stephen II ...

. His coronation, held on 26 October 1377, created the Kingdom of Bosnia. It was traditionally held that Stephen Tvrtko I was crowned in the Mileševo monastery by its metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan (alternative obsolete form: metropolite), pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis.

Originally, the term referred to the b ...

,John Van Antwerp Fine, ''The Late Medieval Balkans, A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest'', University of Michigan Press, 1987 but it has been proposed that he was crowned in the monastery of Mile

The mile, sometimes the international mile or statute mile to distinguish it from other miles, is a British imperial unit and United States customary unit of distance; both are based on the older English unit of length equal to 5,280 English ...

, where most Bosnian coronations were held, with a crown sent by King Louis I of Hungary

Louis I, also Louis the Great ( hu, Nagy Lajos; hr, Ludovik Veliki; sk, Ľudovít Veľký) or Louis the Hungarian ( pl, Ludwik Węgierski; 5 March 132610 September 1382), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and King of Poland from 1370 ...

.Malcolm D. Lambert, ''The Cathars'', Blackwell Publishing, 1998Mitja Velikonja, ''Religious separation and political intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina'', Texas A&M University Press, 2003 Tvrtko I's coronation served as an example to subsequent such rites.

The details of the Bosnian coronation ceremony are unclear. The Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the Bosnian Church

The Bosnian Church ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=/, Crkva bosanska, Црква Босанска) was a Christian church in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina that was independent of and considered heretical by both the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox ...

and the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

competed in Bosnia, and it is not even known which church's officials performed the coronation. The Bosnian Church is considered least likely to have led the ceremony, as its elders frowned upon such rituals. The liturgical aspect of the ceremony was important, but not primary. A specific crown was revered and deemed indispensable for a proper coronation. Dethroned rulers had to undergo another coronation upon restoration to the throne.Pavo Živković, ''Tvrtko II Tvrtković: Bosna u prvoj polovini XV stoljeća'', Institut za istoriju, 1981, page 84. The coronation was sometimes delayed, but monarchs could exercise full authority immediately after their election.Ćirković, Sima (1964). Историја средњовековне босанске државе (in Serbo-Croatian). Srpska književna zadruga. Page 225.

The last coronation in Bosnia was held in the St. Mary's Church in Jajce

Jajce (Јајце) is a town and municipality located in the Central Bosnia Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to the 2013 census, the town has a population of 7,172 inhabitants, with ...

, November 1461. Although all kings of Bosnia were at least formally Roman Catholic, only the last king, Stephen Tomašević

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

, was crowned with the Pope's approval and with a crown sent by Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August ...

. The coronation was performed by the papal legate.

Bulgaria

The rulers of theSecond Bulgarian Empire

The Second Bulgarian Empire (; ) was a medieval Bulgarians, Bulgarian state that existed between 1185 and 1396. A successor to the First Bulgarian Empire, it reached the peak of its power under Tsars Kaloyan of Bulgaria, Kaloyan and Ivan Asen II ...

were crowned in the same manner as Byzantine emperors, while the manner of coronation of the rulers of the First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire ( cu, блъгарьско цѣсарьствиѥ, blagarysko tsesarystviye; bg, Първо българско царство) was a medieval Bulgar- Slavic and later Bulgarian state that existed in Southeastern Europ ...

remains unknown. Modern Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

was a monarchy from its independence in 1878 until 1946. The modern hereditary Bulgarian kings were pronounced heads of state by the Parliament and anointed at the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia, but did not pass the formal coronation ritual known in the western countries.

Croatia

According to legend, the first crowned monarch of Croatia was

According to legend, the first crowned monarch of Croatia was King Tomislav

Tomislav (, la, Tamisclaus) was the first king of Croatia. He became Duke of Croatia and was crowned king in 925, reigning until 928. During Tomislav's rule, Croatia forged an alliance with the Byzantine Empire against Bulgaria. Croatia's strug ...

. He was allegedly crowned on the Plain of Duvno

Tomislavgrad (), also known by its former name Duvno (), is a town and municipality located in Canton 10 of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It mainly covers an area of the historical and geographica ...

in 925. However, it is disputed whether Tomislav was ever crowned; some sources identify Držislav as the first crowned King of Croatia, ignoring the legend of Tomislav's coronation.

Zvonimir

Zvonimir is a Croatian male given name, used since the Middle Ages.

During Yugoslavia, the name became popular in other ex-Yugoslav republics like Croatia and Slovenia.{{citation needed, date=February 2014

People named Zvonimir

*Demetrius Zvon ...

was crowned as King of Croatia and Dalmatia on 8 October 1076 at Solin

Solin (Latin and it, Salona; grc, Σαλώνα ) is a town in Dalmatia, Croatia. It is situated right northeast of Split, on the Adriatic Sea and the river Jadro.

Solin developed on the location of ancient city of ''Salona'', which was the ca ...

in the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

Basilica of Saint Peter and Moses (known today as the ''Hollow Church'') by Gebizo, a representative of Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII ( la, Gregorius VII; 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana ( it, Ildebrando di Soana), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint ...

(1073-1085).

In 1102, upon the death of the last member of the House of Trpimirović

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

, Croatia entered a personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with Hungary. It was agreed that every King of Hungary would come to Croatia for a separate coronation as King of Croatia. This second coronation was required to soothe Croatian sensibilities, by demonstrating that Croatia remained an independent state. The last King of Croatia to be crowned in Croatia was King Andrew II of Hungary. His son and successor, King Béla, refused to be crowned in Croatia in 1235, and the custom afterwards died out. Some scholars claim that Béla IV's father was never crowned as King of Croatia either. The issue remains unsettled, because there are no documents on either of Andrew II's supposed coronations.

In 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 unt ...

was occupied and partitioned by the Axis powers. A puppet state, the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

(NDH), was formed on a part of occupied Yugoslav territory and Aimone, 4th Duke of Aosta, was installed as King by fascist Italy. The Italians planned to have Aimone crowned as "Tomislav II" at the Field of Duvno, where King Tomislav was allegedly crowned. The coronation was never held, due to Italy taking Yugoslav coastal territory that was claimed by the NDH.

Denmark

Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

enthronements may be divided into three distinct types of rituals: the medieval coronation, which existed during the period of elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected monarch, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, and the ...

; the anointing ritual, which replaced coronation with the introduction of absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

in 1660; and finally the simple proclamation, which has been used since the introduction of the Danish Constitution

The Constitutional Act of the Realm of Denmark ( da, Danmarks Riges Grundlov), also known as the Constitutional Act of the Kingdom of Denmark, or simply the Constitution ( da, Grundloven, fo, Grundlógin, kl, Tunngaviusumik inatsit), is the c ...

in 1849.

The coronation ritual (as of 1537) began with a procession of the ruler and his consort into St. Mary's Cathedral in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, followed by the Danish crown jewels. The monarch was seated before the altar, where he swore to govern justly, preserve the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

religion, support schools, and help the poor. Following this, the king was anointed on the lower right arm and between the shoulders, but not on the head. Then the royal couple retired to a tented enclosure where they were robed in royal attire, returning to hear a sermon, the Kyrie

Kyrie, a transliteration of Greek , vocative case of (''Kyrios''), is a common name of an important prayer of Christian liturgy, also called the Kyrie eleison ( ; ).

In the Bible

The prayer, "Kyrie, eleison," "Lord, have mercy" derives fr ...

and Gloria

Gloria may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music Christian liturgy and music

* Gloria in excelsis Deo, the Greater Doxology, a hymn of praise

* Gloria Patri, the Lesser Doxology, a short hymn of praise

** Gloria (Handel)

** Gloria (Jenkins) ...

, and then a prayer and the Epistle

An epistle (; el, ἐπιστολή, ''epistolē,'' "letter") is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as par ...

reading.

Following the Epistle, the king knelt before the altar, where he was first given a sword. After flourishing and sheathing it, the still-kneeling monarch was crowned by the clergy and nobility, who jointly placed the diadem upon their ruler's head. The sceptre and orb were presented, then returned to attendants. The queen was anointed and crowned in a similar manner, but she received only a sceptre and not an orb. A choral hymn was then sung, and then the newly crowned king and queen listened to a second sermon and the reading of the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

, which brought the service to an end.

In 1660 the coronation ritual was replaced with a ceremony of anointing

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or oth ...

: the new king would arrive at the coronation site already wearing the crown, and he was then anointed. This rite was in turn abolished with the introduction of the Danish Constitution in 1849. Today the crown of Denmark is only displayed at the monarch's funeral, when it lies on top of their coffin. The present Queen, Margrethe II

Margrethe II (; Margrethe Alexandrine Þórhildur Ingrid, born 16 April 1940) is Queen of Denmark. Having reigned as Denmark's monarch for over 50 years, she is Europe's longest-serving current head of state and the world's only incumbent femal ...

, did not have any formal enthronement service; a public announcement of her accession was made from the balcony of Christiansborg Palace

Christiansborg Palace ( da, Christiansborg Slot; ) is a palace and government building on the islet of Slotsholmen in central Copenhagen, Denmark. It is the seat of the Danish Parliament ('), the Danish Prime Minister's Office, and the Supreme ...

, with the new sovereign being acclaimed by her Prime Minister at the time (1972), Jens Otto Krag

Jens Otto Krag (; 15 September 1914 – 22 June 1978) was a Danish politician who served as prime minister of Denmark from 1962 to 1968 and from 1971 to 1972, and as leader of the Social Democrats from 1962 to 1972. He was president of the Nordi ...

, then cheered with a ninefold "hurrah" by the crowds below.

England

:''This section describes coronations held in England prior to its unification with Scotland. For coronations after that time, see below under "United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

".''

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

has long been England's coronation church since 1066. From William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

through to Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

, all except two monarchs have been crowned in the Abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conce ...

.

Following the start of the reformation in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, the boy king Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

had been crowned in the first Protestant coronation in 1547, during which Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry' ...

preached a sermon against idolatry and "the tyranny of the bishops of Rome". However, six years later, he was succeeded by his half-sister Mary I, who restored the Catholic rite. In 1559, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

underwent the last English coronation under the auspices of the Catholic Church; however, Elizabeth's insistence on changes to reflect her Protestant beliefs resulted in several bishops refusing to officiate at the service and it was conducted by the low-ranking bishop of Carlisle, Owen Oglethorpe

Owen Oglethorpe ( – 31 December 1559) was an English academic and Roman Catholic Bishop of Carlisle, 1557–1559.

Childhood and Education

Oglethorpe was born in Tadcaster, Yorkshire, England (where he later founded a school), the third son ...

.

After the Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

, England and Scotland merged to form the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

.

France

Following perhaps the Byzantine or Visigothic formula, the French coronation ceremony called ''Sacre'' primarily included the

Following perhaps the Byzantine or Visigothic formula, the French coronation ceremony called ''Sacre'' primarily included the anointing

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or oth ...

or unction

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or oth ...

of the king. It was first held in Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital ...

in 752 for the Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

king Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

to legitimise his deposition of the last of the Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

kings, who had been elected by an assembly of nobles inside the royal family and according to hereditary rules. A second coronation of Pepin by Pope Stephen II

Pope Stephen II ( la, Stephanus II; 714 – 26 April 757) was born a Roman aristocrat and member of the Orsini family. Stephen was the bishop of Rome from 26 March 752 to his death. Stephen II marks the historical delineation between the Byzant ...

took place at the Basilica of St Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (french: Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, links=no, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building ...

in 754; this is the first recorded by a Pope. The unction served as a reminder of the baptism of king Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single kin ...

in Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

by archbishop Saint Remi

Remigius (french: Remi or ; – January 13, 533), was the Bishop of Reims and "Apostle of the Franks". On 25 December 496, he baptised Clovis I, King of the Franks. The baptism, leading to about 3000 additional converts, was an important eve ...

in 496/499, where the ceremony was finally transferred in 816 and completed with the use of the Holy Ampulla

The Holy Ampulla or Holy Ampoule (''Sainte Ampoule'' in French) was a glass vial which, from its first recorded use by Pope Innocent II for the anointing of Louis VII in 1131 to the coronation of Louis XVI in 1774, held the chrism or anointing ...

found in 869 in the grave of the saint. Since this Roman glass vial, containing the balm due to be mixed with chrism

Chrism, also called myrrh, ''myron'', holy anointing oil, and consecrated oil, is a consecrated oil used in the Anglican, Assyrian, Catholic, Nordic Lutheran, Old Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Latter Day Saint churches in ...

, was allegedly brought by the dove of the Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

, the French monarchs claimed to receive their power by divine right. The French coronation ritual was similar to that used in England, from 925 and above all 1066, with the coronation of William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

. The last royal coronation was that of Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Loui ...

, in 1825. Heirs to the French throne were also sometimes crowned during their predecessors' reigns during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, but this was discontinued as laws of primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

became stronger. The coronation regalia

Regalia is a Latin plurale tantum word that has different definitions. In one rare definition, it refers to the exclusive privileges of a sovereign. The word originally referred to the elaborate formal dress and dress accessories of a sovereign ...

like the throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the monar ...

and sceptre

A sceptre is a staff or wand held in the hand by a ruling monarch as an item of royal or imperial insignia. Figuratively, it means royal or imperial authority or sovereignty.

Antiquity

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

The ''Was'' and other ...

of Dagobert I

Dagobert I ( la, Dagobertus; 605/603 – 19 January 639 AD) was the king of Austrasia (623–634), king of all the Franks (629–634), and king of Neustria and Burgundy (629–639). He has been described as the last king of the Merovingian dy ...

or crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

and sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

, were kept in the Basilica of Saint-Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (french: Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, links=no, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building ...

near Paris, and the liturgical instruments, like the Holy Ampulla

The Holy Ampulla or Holy Ampoule (''Sainte Ampoule'' in French) was a glass vial which, from its first recorded use by Pope Innocent II for the anointing of Louis VII in 1131 to the coronation of Louis XVI in 1774, held the chrism or anointing ...

and Chalice

A chalice (from Latin 'mug', borrowed from Ancient Greek () 'cup') or goblet is a footed cup intended to hold a drink. In religious practice, a chalice is often used for drinking during a ceremony or may carry a certain symbolic meaning.

Re ...

, in Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

, where they are still partly preserved as well as in the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

and other Parisian museums.

During the

During the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eu ...

, Emperor Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and Empress Josephine were crowned in December 1804 in an extremely elaborate ritual presided over by Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

and conducted at the Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the ...

in Paris. Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

chose not to be crowned. The French republican government broke up and sold off most of the Crown Jewels, in the hope of avoiding any public sentiment for a restoration of the monarchy after the collapse of the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Empire, Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the French Second Republic, Second and the French Third Republic ...

in 1871.

Greece

Although Greece retains a set of crown jewels given to it by its first king,Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Francia, East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the olde ...

, no King of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach between 1832 and 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924, temporarily abolished during the Second Hellenic Republic, and from 1935 to 1973, when it was once more abolishe ...

was ever crowned with them. All monarchs apart from Otto took office by a swearing-in ceremony in front of the Greek Parliament

The Hellenic Parliament ( el, Ελληνικό Κοινοβούλιο, Elliniko Kinovoulio; formally titled el, Βουλή των Ελλήνων, Voulí ton Ellínon, Boule of the Hellenes, label=none), also known as the Parliament of the Hel ...

, until the Greek monarchy was abolished in 1973 by a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

following a short-lived dictatorship by the Greek junta during which the king had fled the country.

Holy Roman Empire

Since

Since Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

in 800, Holy Roman Emperors

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperator ...

were crowned by the pope until 1530, when Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

became the last Holy Roman Emperor to be crowned by the Pope, at Bologna. Thereafter, until the abolition of the empire in 1806, imperial coronations were held in Frankfurt and were performed by the Spiritual Princes-Electors, the Archbishops of Cologne, Mainz and Trier.See also Guy Stair SaintyThe Holy Roman Empire: Introduction

. From th

Almanach de la Cour

website. Retrieved on 14 September 2008. Later rulers simply proclaimed themselves ''Electus Romanorum Imperator'' or "Elected Emperor of the Romans", without the formality of a coronation by the Pontiff. Coronations were held in Rome (under the pope),

Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

(the Kingdom of Italy), Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province of ...

(Burgundy) and Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

(Germany). Although the Roman ceremony was initially the most important, it was eventually eclipsed by the German ritual. The custom of the emperors going to Rome to be crowned was last observed by Frederick III in 1440; after that only the German coronation was celebrated.

Hungary

Rulers of Hungary were not considered legitimate monarchs until they were crowned King of Hungary with the

Rulers of Hungary were not considered legitimate monarchs until they were crowned King of Hungary with the Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( hu, Szent Korona; sh, Kruna svetoga Stjepana; la, Sacra Corona; sk, Svätoštefanská koruna , la, Sacra Corona), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the ...

. As women were not considered fit to rule Hungary, the two queens regnant, Maria I

Dom (title), Dona Maria I (17 December 1734 – 20 March 1816) was Queen of Portugal from 24 February 1777 until her death in 1816. Known as Maria the Pious in Portugal and Maria the Mad in Brazil, she was the first undisputed queen regnant of Por ...

and Maria II Theresa, were crowned ''kings'' of Hungary.Bernard Newman, ''The New Europe'', 1972 Hungarian coronations usually took place at Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; german: Stuhlweißenburg ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the regional capital of Central Transdanubia, and the centre of Fejér ...

, the burial place of the first crowned ruler of Hungary, Saint Stephen I

Pope Stephen I ( la, Stephanus I) was the bishop of Rome from 12 May 254 to his death on 2 August 257.Mann, Horace (1912). "Pope St. Stephen I" in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. He was later Canonizati ...

, except years 1563 – 1830, when did coronations took place in St. Martin cathedral in Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approxim ...

, because of Ottoman occupation of Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; german: Stuhlweißenburg ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the regional capital of Central Transdanubia, and the centre of Fejér ...

.

. The final such rite was held in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

on 30 December 1916, when ''Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

'' Karl I of Austria

Charles I or Karl I (german: Karl Franz Josef Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Maria, hu, Károly Ferenc József Lajos Hubert György Ottó Mária; 17 August 18871 April 1922) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary (as Charles IV, ), King of Croatia, ...

and Empress

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Zita

Zita (c. 1212 – 27 April 1272; also known as Sitha or Citha) is an Italian saint, the patron saint of maids and domestic servants. She is often appealed to in order to help find lost keys.

She is often confused with St. Osyth or Ositha, ...

were crowned as King Károly IV and Queen Zita of Hungary. The Hungarian monarchy perished with the end of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, although the nation would later restore a titular monarchy from 1920 to 1945—while forbidding King Károly from resuming the throne. A communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

takeover in 1945 spelled the final end of this "kingdom without a king".

Italy

The modernKingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, which existed from 1861 to 1946, did not crown its monarchs.

The Sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

were crowned Kings of Italy with the famous Iron Crown

The Iron Crown ( lmo, Corona Ferrea de Lombardia; it, Corona Ferrea; la, Corona Ferrea) is a relic and may be one of the oldest royal insignia of Christendom. It was made in the Early Middle Ages, consisting of a circlet of gold and jewels fit ...

; also Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

was crowned King of Italy in 1805 with this crown.

Liechtenstein

The sovereign Princes of Liechtenstein have never undergone a coronation or enthronement ceremony, although PrinceHans-Adam II

Hans-Adam II (Johannes Adam Ferdinand Alois Josef Maria Marco d'Aviano Pius; born 14 February 1945) is the reigning Prince of Liechtenstein, since 1989. He is the son of Prince Franz Joseph II and his wife, Countess Georgina von Wilczek. He al ...

attended a mass by the Archbishop of Vaduz

Vaduz ( or , High Alemannic pronunciation: [])Hans Stricker, Toni Banzer, Herbert Hilbe: ''Liechtensteiner Namenbuch. Die Orts- und Flurnamen des Fürstentums Liechtenstein.'' Band 2: ''Die Namen der Gemeinden Triesenberg, Vaduz, Schaan.'' Hrsg. ...

, followed by a choral display. In 1719 the Liechtenstein family finally attained the long-sought rank of Princes of the Holy Roman Empire, and had a crown (or ducal hat, as it is named) made of diamonds, pearls and rubies. However, as the subsequent princes always resided in Vienna, and until modern times did not even visit their principality, the original princely crown may never have been brought there, and is now lost. On the occasion of his seventieth birthday, Franz Joseph II, Prince of Liechtenstein

Franz Joseph II (Franz Josef Maria Aloys Alfred Karl Johannes Heinrich Michael Georg Ignaz Benediktus Gerhardus Majella; 16 August 1906 – 13 November 1989) was the reigning Prince of Liechtenstein from 25 July 1938 until his death.

Franz Jose ...

, the first monarch of Liechtenstein to dwell in his own realm, was given a princely coronet

A coronet is a small crown consisting of ornaments fixed on a metal ring. A coronet differs from other kinds of crowns in that a coronet never has arches, and from a tiara in that a coronet completely encircles the head, while a tiara does ...

edged in ermine, a replica of the original, as a gift from his people, which is kept on display in the principality. But it has never been used in a coronation nor worn by a reigning prince. Typical of princely coronets, it lacks "royal" arches, and is surmounted by a tassel

A tassel is a finishing feature in fabric and clothing decoration. It is a universal ornament that is seen in varying versions in many cultures around the globe.

History and use

In the Hebrew Bible, the Lord spoke to Moses instructing him to ...

instead of a royal orb or cross.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg's sovereignGrand Dukes

Grand duke (feminine: grand duchess) is a European hereditary title, used either by certain monarchs or by members of certain monarchs' families. In status, a grand duke traditionally ranks in order of precedence below an emperor, as an approx ...

have never been crowned. Instead, the sovereign is enthroned at a simple ceremony held in the nation's parliament at the beginning of his or her reign to take an oath of loyalty to the state constitution as required by the constitution.

The sovereign then attends a solemn mass at the Notre-Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the ...

. No crown or other regalia exists for the rulers of Europe's last sovereign Grand Duchy

A grand duchy is a sovereign state, country or territory whose official head of state or ruler is a monarch bearing the title of grand duke or grand duchess.

Relatively rare until the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the term was oft ...

.

Monaco

The Principality ofMonaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign city-state and microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Italian region of Lig ...

does not possess any regalia, and thus does not physically crown its ruler. However, the Prince or Princess does attend a special investiture ceremony, consisting of a festive mass in Saint Nicholas Cathedral, followed by a reception where the new sovereign prince meets his people.

Netherlands

The Netherlands have never physically crowned its monarchs. The Dutch monarch, however, undergoes a "swearing-in and investiture" ceremony. Article 32 of the Dutch constitution states that as soon as the monarch assumes the royal prerogative, he is to be sworn in and inaugurated in Amsterdam at a publicjoint session

A joint session or joint convention is, most broadly, when two normally separate decision-making groups meet, often in a special session or other extraordinary meeting, for a specific purpose.

Most often it refers to when both houses of a bicame ...

of the two houses of the States General The word States-General, or Estates-General, may refer to:

Currently in use

* Estates-General on the Situation and Future of the French Language in Quebec, the name of a commission set up by the government of Quebec on June 29, 2000

* States Genera ...

. This ritual is held at the Nieuwe Kerk, in the capital city of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

. Regalia such as the crown, orb and sceptre are present but are never physically given to the monarch, instead they are placed on cushions, on what is called a credence table

A credence table is a small side table in the sanctuary of a Christian church which is used in the celebration of the Eucharist. (Latin ''credens, -entis'', believer).

The credence table is usually placed near the wall on the epistle (south) sid ...

. The royal regalia surround a copy of the Dutch constitution. Two other regalia–the sword of state and the standard of the kingdom bearing the coat of arms of the Netherlands–are carried by two senior military officers.

During the ceremony, the monarch, wearing a ceremonial robe, is seated on a chair of state with his or her consort on a raised dais opposite members of the States General. The ceremony consists of two parts. In the first part, the monarch is sworn in: he takes his formal oath to uphold the kingdom's fundamental law and protect the country with everything within his power. After the king has taken his oath, he is invested by the States General and the States of the other countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

, national_anthem = )

, image_map = Kingdom of the Netherlands (orthographic projection).svg

, map_width = 250px

, image_map2 = File:KonDerNed-10-10-10.png

, map_caption2 = Map of the four constituent countries shown to scale

, capital = ...

: members of the States General pay homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to the monarch. The president of the Joint Session of the States General will first make a solemn declaration while all members of the States General and members of the States of Aruba, Curaçao and St Maarten will then, in turn, swear or affirm this declaration.

Norway

The first coronation in Norway, and Scandinavia, took place inBergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

in 1163 or 1164. The Christ Church (Old Cathedral) in Bergen remained the place of coronations in Norway until the capital was moved to Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

under King Haakon V. From then on some coronations were held in Oslo, but most were held in Nidaros Cathedral

Nidaros Cathedral ( no, Nidarosdomen / Nidaros Domkirke) is a Church of Norway cathedral located in the city of Trondheim in Trøndelag county. It is built over the burial site of Olav II of Norway, King Olav II (c. 995–1030, reigned 1015–102 ...

in Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

.

In 1397, Norway, Sweden and Denmark united in what is referred to as the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union (Danish language, Danish, Norwegian language, Norwegian, and sv, Kalmarunionen; fi, Kalmarin unioni; la, Unio Calmariensis) was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden, that from 1397 to 1523 joined under ...

, sharing the same monarch. During this period the kings were crowned consecutively in each of the three countries until the union was dissolved in 1523. Following this dissolution, Norway entered into a union in 1524 with Denmark which would eventually evolve to an integrated state that was to last until 1814. No coronations were held in Norway during this time. Meanwhile, the monarch underwent a coronation and later, with the introduction of absolutism in 1660, an anointing ceremony in Denmark.

Following the dissolution of Denmark-Norway, Norway declared its independence and elected the Danish heir as its own king. Christian Frederick would "abdicate" this position following the Swedish-Norwegian War and Norway would be forced into a union with Sweden and elected the King of Sweden as King of Norway. The Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

*Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

*Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including the ...

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

of 1814 required the King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingdoms ...

to be crowned in Trondheim. King Karl Johan was subsequently crowned in Stockholm and Trondheim after acceding to the thrones of Sweden and Norway in 1818. Succeeding monarchs would also be crowned separately in Sweden and Norway.

In 1905, the personal union between Sweden and Norway was dissolved. Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick VI ...

was subsequently elected Norway's monarch. Haakon and his wife Queen Maud were the last to be crowned in Nidaros Cathedral

Nidaros Cathedral ( no, Nidarosdomen / Nidaros Domkirke) is a Church of Norway cathedral located in the city of Trondheim in Trøndelag county. It is built over the burial site of Olav II of Norway, King Olav II (c. 995–1030, reigned 1015–102 ...

in 1906. Following this, the constitutional provision requiring the coronation was repealed in 1908. Thereafter, the monarch has only been required to take his formal accession oath in the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

and then in the parliament, the Storting

The Storting ( no, Stortinget ) (lit. the Great Thing) is the supreme legislature of Norway, established in 1814 by the Constitution of Norway. It is located in Oslo. The unicameral parliament has 169 members and is elected every four years bas ...

. King Olav V

Olav V (; born Prince Alexander of Denmark; 2 July 1903 – 17 January 1991) was the King of Norway from 1957 until his death in 1991.

Olav was the only child of King Haakon VII of Norway and Maud of Wales. He became heir apparent to the Norw ...

, desiring a religious ceremony to mark his accession to the throne in 1957, instituted a ceremony of royal consecration, known as . This "blessing" rite took place again in 1991, when King Harald V

Harald V ( no, Harald den femte, ; born 21 February 1937) is King of Norway. He acceded to the throne on 17 January 1991.

Harald was the third child and only son of King Olav V of Norway and Princess Märtha of Sweden. He was second in the lin ...

and Queen Sonja

Sonja (born Sonja Haraldsen on 4 July 1937) is Queen of Norway since 17 January 1991 as the wife of King Harald V.

Sonja and the then Crown Prince Harald had dated for nine years prior to their marriage in 1968. They had kept their relations ...

were similarly consecrated. Both consecrations were held where the coronation rite had formerly taken place: Nidaros Cathedral

Nidaros Cathedral ( no, Nidarosdomen / Nidaros Domkirke) is a Church of Norway cathedral located in the city of Trondheim in Trøndelag county. It is built over the burial site of Olav II of Norway, King Olav II (c. 995–1030, reigned 1015–102 ...

in Trondheim.

Poland

Poland crowned its rulers beginning in 1025; the final such ceremony occurred in 1764, when the last Polish King,Stanisław August Poniatowski

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1764 to 1795, and the last monarch ...

, was crowned at St. John's Cathedral, Warsaw. Other coronations took place at Wawel Cathedral

The Wawel Cathedral ( pl, Katedra Wawelska), formally titled the Royal Archcathedral Basilica of Saints Stanislaus and Wenceslaus, is a Roman Catholic cathedral situated on Wawel Hill in Kraków, Poland. Nearly 1000 years old, it is part of the ...

in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, and also in Poznań