Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

began

colonizing the Americas under the

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accessi ...

and was spearheaded by the Spanish . The Americas were invaded and incorporated into the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, with the exception of

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

,

British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas from 16 ...

, and some small regions of South America and the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

. The crown created civil and religious structures to administer the vast territory. The main motivations for colonial expansion were profit through

resource extraction

Extractivism is the process of extracting natural resources from the Earth to sell on the world market. It exists in an economy that depends primarily on the extraction or removal of natural resources that are considered valuable for exportation w ...

and the

spread of Catholicism by converting

indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

.

Beginning with

Columbus's first voyage

Between 1492 and 1504, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus led four Spanish transatlantic maritime expeditions of discovery to the Americas. These voyages led to the widespread knowledge of the New World. This breakthrough inaugurated the per ...

to the Caribbean and gaining control over more territory for over three centuries, the Spanish Empire would expand across the

Caribbean Islands

Almost all of the Caribbean islands are in the Caribbean Sea, with only a few in inland lakes. The largest island is Cuba. Other sizable islands include Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico and Trinidad and Tobago. Some of the smaller islands are re ...

, half of South America, most of Central America and much of North America. It is estimated that during the colonial period (1492–1832), a total of 1.86 million

Spaniards

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance peoples, Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of National and regional identity in Spain, national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex Hist ...

settled in the Americas, and a further 3.5 million immigrated during the post-colonial era (1850–1950); the estimate is 250,000 in the 16th century and most during the 18th century, as immigration was encouraged by the new

Bourbon dynasty

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

.

By contrast,

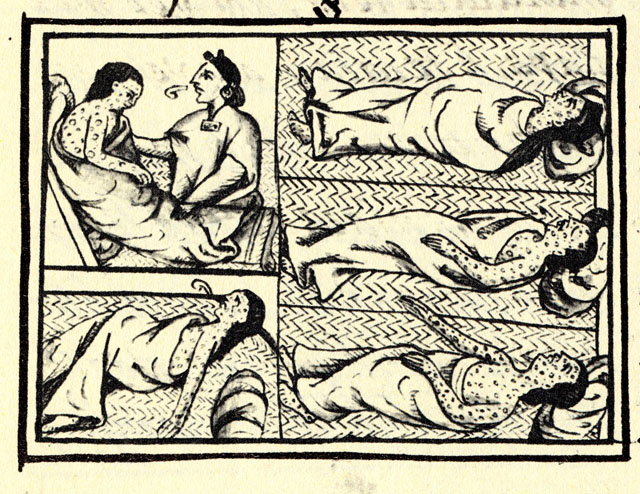

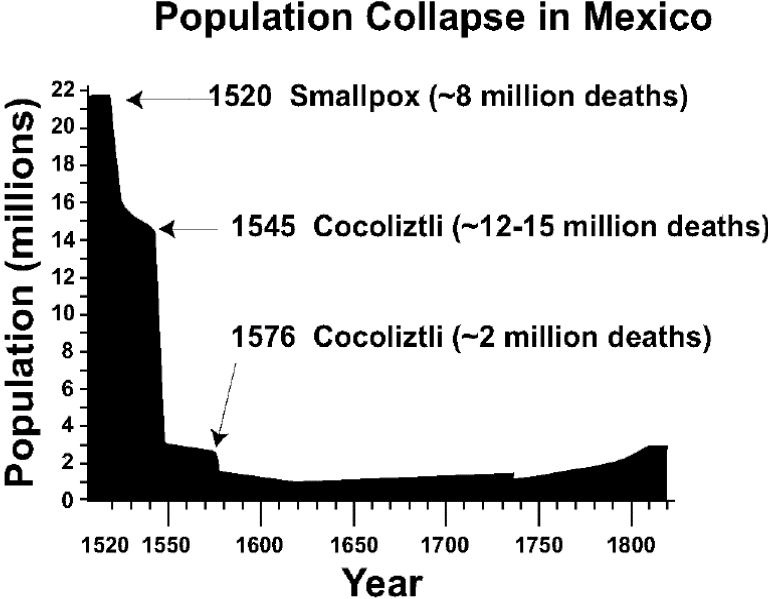

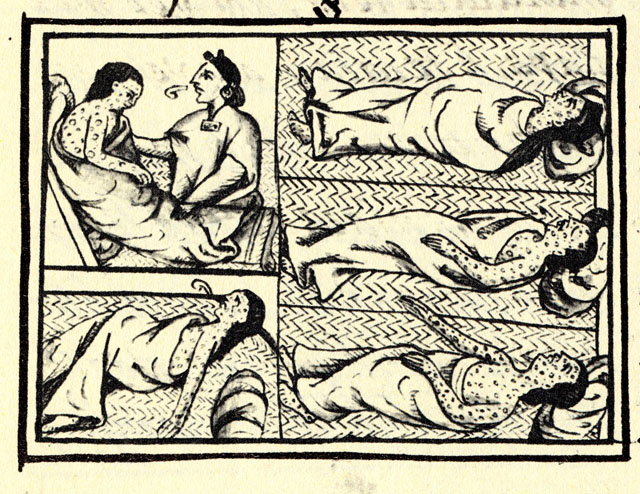

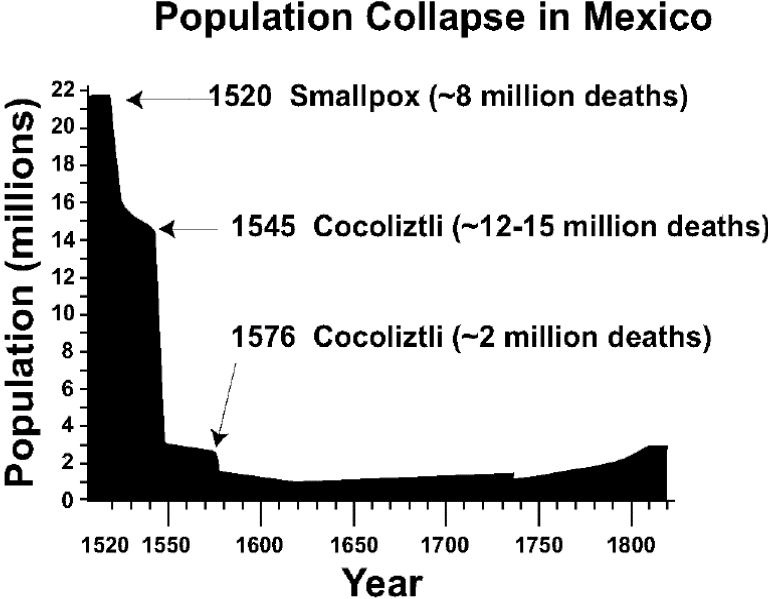

the indigenous population plummeted by an estimated 80% in the first century and a half following Columbus's voyages, primarily through

the spread of disease,

forced labor and slavery for resource extraction, and

missionization.

["La catastrophe démographique" (The Demographic Catastrophe) in '']L'Histoire

''L'Histoire'' is a monthly mainstream French magazine dedicated to historical studies, recognized by peers as the most important historical popular magazine (as opposed to specific university journals or less scientific popular historical mag ...

'' n°322, July–August 2007, p. 17 This has been argued to be the first large-scale act of

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

in the modern era.

In the early 19th century, the

Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

resulted in the secession and subsequent division of most Spanish territories in the Americas, except for

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

and

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

, which were lost to the United States in 1898, following the

Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. The loss of these territories ended Spanish rule in the Americas.

Imperial expansion

The expansion of Spain’s territory took place under the Catholic Monarchs

Isabella of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 by ...

, Queen of

Castile and her husband

King Ferdinand, King of

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, whose marriage marked the beginning of Spanish power beyond the

Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

. They pursued a policy of joint rule of their kingdoms and created the initial stage of a single

Spanish monarchy

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

, completed under the eighteenth-century Bourbon monarchs. The first expansion of territory was the conquest of the Muslim

Emirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada ( ar, إمارة غرﻧﺎﻃﺔ, Imārat Ġarnāṭah), also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada ( es, Reino Nazarí de Granada), was an Emirate, Islamic realm in southern Iberia during the Late Middle Ages. It was the ...

on 1 January 1492, the culmination of the Christian

Reconquest of the Iberian peninsula, held by the Muslims since 711. On 31 March 1492, the Catholic Monarch ordered the expulsion of the Jews in Spain who refused to convert to Christianity. On 12 October 1492, Genoese mariner

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

made landfall in the Western Hemisphere.

Even though Castile and Aragon were ruled jointly by their respective monarchs, they remained separate kingdoms so that when the Catholic Monarchs gave official approval for the plans for Columbus’s voyage to reach "the Indies" by sailing West, the funding came from the queen of Castile. The profits from Spanish expedition flowed to Castile. The

Kingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal ( la, Regnum Portugalliae, pt, Reino de Portugal) was a monarchy in the western Iberian Peninsula and the predecessor of the modern Portuguese Republic. Existing to various extents between 1139 and 1910, it was also kno ...

authorized a series of voyages down the coast of Africa and when they rounded the southern tip, were able to sail to India and further east. Spain sought similar wealth, and authorized Columbus’s voyage sailing west. Once the Spanish settlement in the Caribbean occurred, Spain and Portugal formalized a division of the world between them in the 1494

Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Emp ...

. The deeply pious Isabella saw the expansion of Spain's sovereignty inextricably paired with the evangelization of non-Christian peoples, the so-called “spiritual conquest” with the military conquest. Pope

Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Churc ...

in a 4 May 1493 papal decree, ''

Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other orks) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May () 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile all lands to the "west and south" o ...

'', divided rights to lands in the Western Hemisphere between Spain and Portugal on the proviso that they spread Christianity. These formal arrangements between Spain and Portugal and the pope were ignored by other European powers.

General principles of expansion

The Spanish expansion has sometimes been succinctly summed up as "gold, glory, God." The search for material wealth, the enhancement of the conquerors' and the crown's position, and the expansion of Christianity. In the extension of Spanish sovereignty to its overseas territories, authority for expeditions (''entradas'') of discovery, conquest, and settlement resided in the monarchy. Expeditions required authorization by the crown, which laid out the terms of such expedition. Virtually all expeditions after the Columbus voyages, which were funded by the crown of Castile, were done at the expense of the leader of the expedition and its participants. Although often the participants,

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

s, are now termed “soldiers”, they were not paid soldiers in ranks of an army, but rather

soldiers of fortune, who joined an expedition with the expectation of profiting from it. The leader of an expedition, the ''

adelantado

''Adelantado'' (, , ; meaning "advanced") was a title held by Spanish nobles in service of their respective kings during the Middle Ages. It was later used as a military title held by some Spain, Spanish ''conquistadores'' of the 15th, 16th and 17 ...

'' was a senior with material wealth and standing who could persuade the crown to issue him a license for an expedition. He also had to attract participants to the expedition who staked their own lives and meager fortunes on the expectation of the expedition’s success. The leader of the expedition pledged the larger share of capital to the enterprise, which in many ways functioned as a commercial firm. Upon the success of the expedition, the spoils of war were divvied up in proportion to the amount a participant initially staked, with the leader receiving the largest share. Participants supplied their own armor and weapons, and those who had a horse received two shares, one for himself, the second recognizing the value of the horse as a machine of war. For the conquest era, two names of Spaniards are generally known because they led the conquests of high indigenous civilizations,

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

, leader of the expedition that

conquered the Aztecs of Central Mexico, and

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

, leader of the

conquest of the Inca in Peru.

Caribbean islands and the Spanish Main

Until his dying day, Columbus was convinced that he had reached Asia, the Indies. From that misperception the Spanish called the

indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

, "Indians" (''indios''), lumping a multiplicity of civilizations, groups, and individuals into a single category. The Spanish royal government called its overseas possessions "The Indies" until its empire dissolved in the nineteenth century. Patterns set in this early period of exploration and colonization were to endure as Spain expanded further, even as the region became less important in the overseas empire after the conquests of Mexico and Peru.

In the Caribbean, there was no large-scale Spanish conquest of indigenous peoples, but there was indigenous resistance. Columbus made four voyages to the

West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

as the monarchs granted Columbus vast powers of governance over this unknown part of the world. The crown of Castile financed more of his trans-Atlantic journeys, a pattern they would not repeat elsewhere. Effective Spanish settlement began in 1493, when Columbus brought livestock, seeds, agricultural equipment. The first settlement of

La Navidad

La Navidad ("The Nativity", i.e. Christmas) was a settlement that Christopher Columbus and his men established on the northeast coast of Haiti (near what is now Caracol, Nord-Est Department, Haiti) in 1492 from the remains of the Spanish ship th ...

, a crude fort built on his first voyage in 1492, had been abandoned by the time he returned in 1493. He then founded the settlement of

La Isabela

La Isabela in Puerto Plata Province, Dominican Republic was the first Spanish town in the Americas. The site is 42 km west of the city of Puerto Plata, adjacent to the village of El Castillo. The area now forms a National Historic Park.

...

on the island they named

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

(now divided into

Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

and the

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

).

Spanish explorations of other islands in the Caribbean and what turned out to be the mainland of South and Central America occupied them for over two decades. Columbus had promised that the region he now controlled held a huge treasure in the form of gold and spices. Spanish settlers found relatively dense populations of indigenous peoples, who were agriculturalists living in villages ruled by leaders not part of a larger integrated political system. For the Spanish, these populations were there for their exploitation, to supply their own settlements with foodstuffs, but more importantly for the Spanish, to extract mineral wealth or produce another valuable commodity for Spanish enrichment. The labor of dense populations of

Tainos were allocated to Spanish settlers in an institution known as the

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

, where particular indigenous settlements were awarded to individual Spaniards. There was surface gold found in early islands, and holders of encomiendas put the indigenous to work panning for it. For all practical purposes, this was slavery. Queen Isabel put an end to formal slavery, declaring the indigenous to be vassals of the crown, but Spaniards' exploitation continued. The Taino population on Hispaniola went from hundreds of thousands or millions –- the estimates by scholars vary widely—but in the mid-1490s, they were practically wiped out. Disease and overwork, disruption of family life and the agricultural cycle (which caused severe food shortages to Spaniards dependent on them) rapidly decimated the indigenous population. From the Spanish viewpoint, their source of labor and viability of their own settlements was at risk. After the collapse of the Taino population of Hispaniola, Spaniards took to slave raiding and settlement on nearby islands, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica, replicating the demographic catastrophe there as well.

Dominican friar

Antonio de Montesinos

Antonio de Montesinos or Antonio Montesino (c. 1475 - June 27, 1540) was a Spanish Dominican friar who was a missionary on the island of Hispaniola (now comprising the Dominican Republic and Haiti). With the backing of Pedro de Córdoba and ...

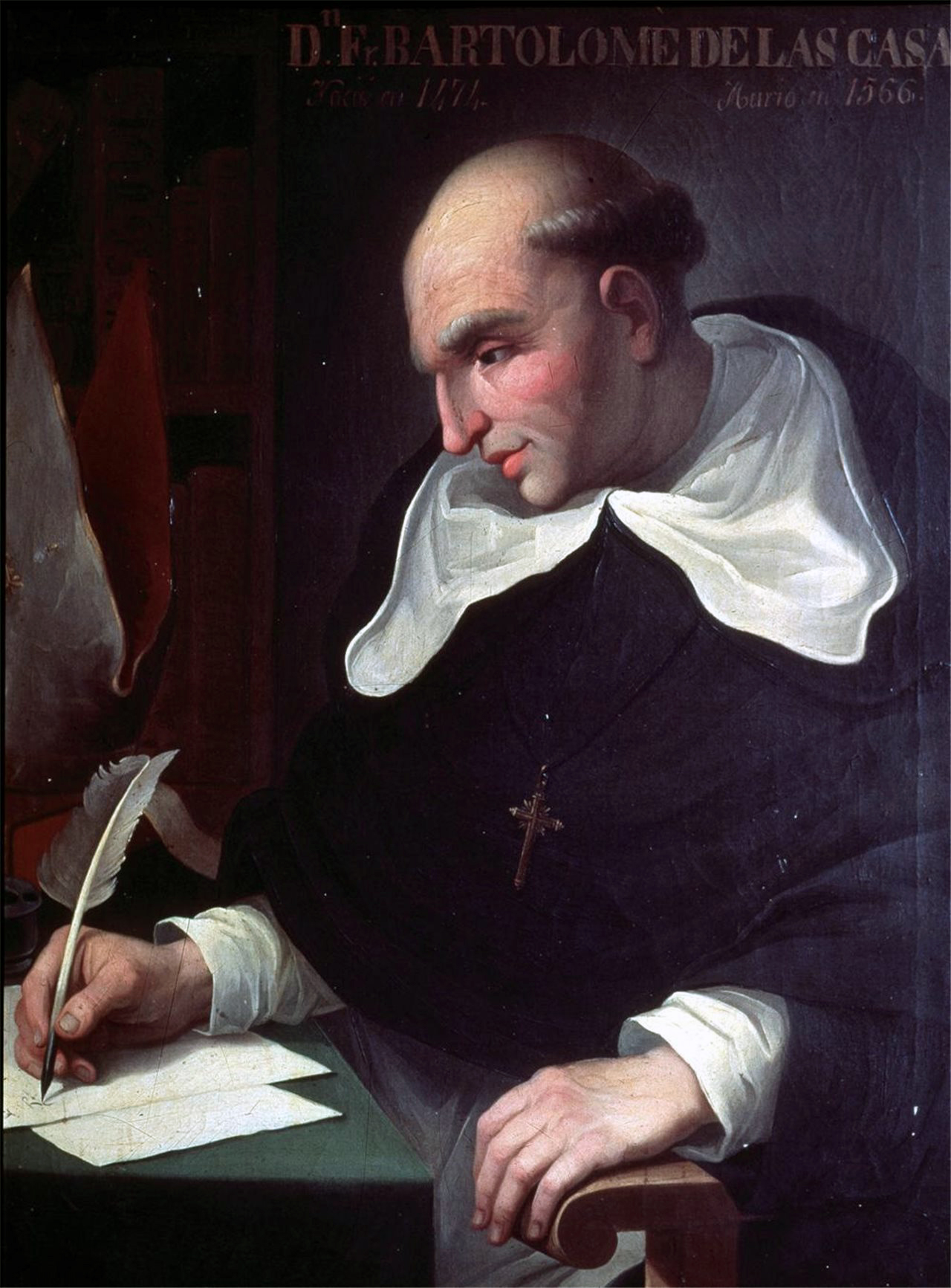

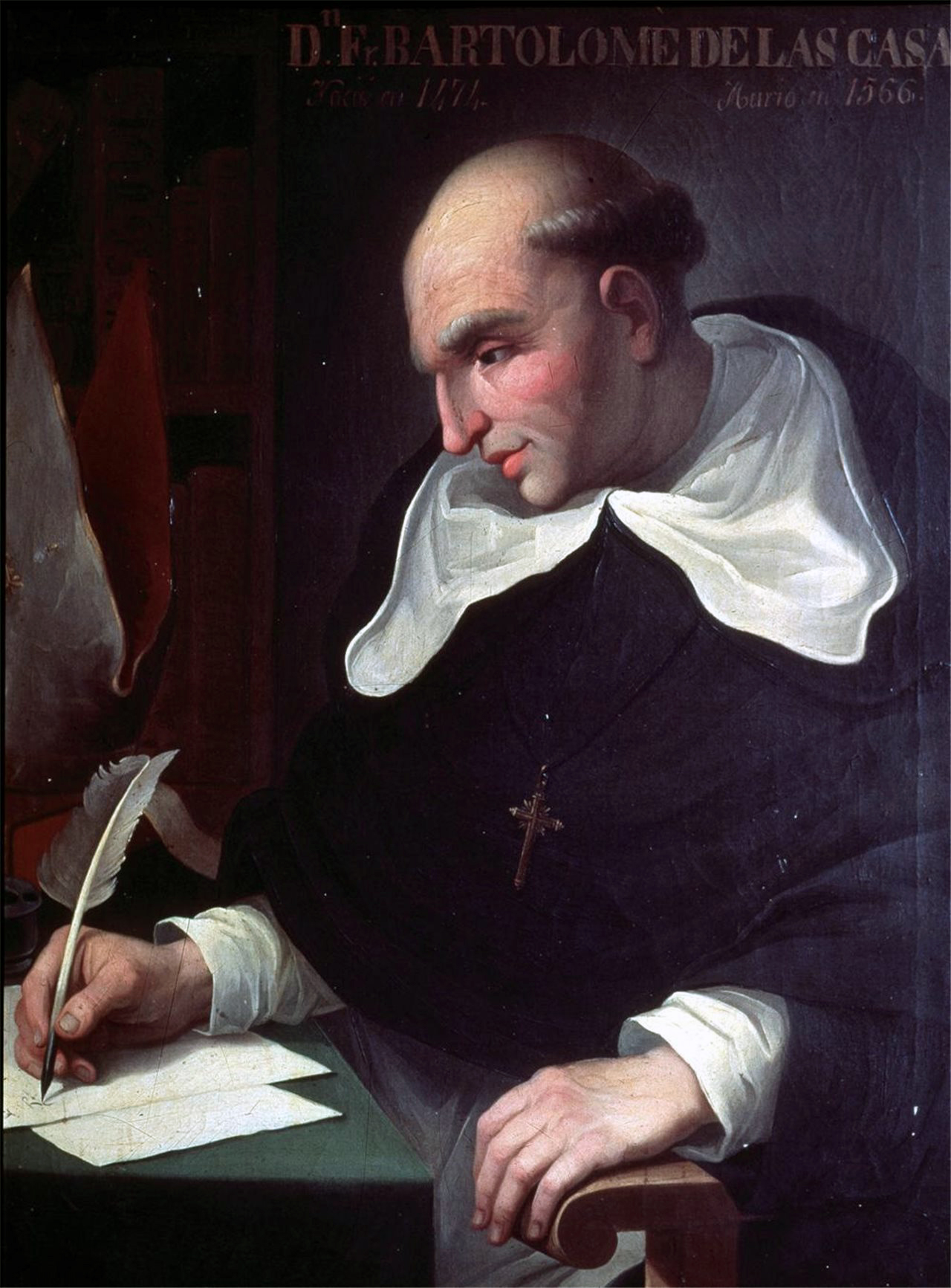

denounced Spanish cruelty and abuse in a sermon in 1511, which comes down to us in the writings of Dominican friar

Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

. In 1542 Las Casas wrote a damning account of this genocide, ''A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies''. It was translated quickly to English and became the basis for the anti-Spanish writings, collectively known as the

Black Legend.

The first mainland explorations by Spaniards were followed by a phase of inland expeditions and conquest. In 1500 the city of

Nueva Cádiz

''

Nueva Cádiz is an archaeological site and former port town on Cubagua, off the coast of Venezuela. First established in 1500 as a seasonal settlement, by 1515 it had become a year-round permanent town. it was one of the first European settlem ...

was founded on the island of

Cubagua

Cubagua Island or Isla de Cubagua () is the smallest and least populated of the three islands constituting the Venezuelan state of Nueva Esparta, after Margarita Island and Coche Island. It is located north of the Araya Peninsula, the closest ...

,

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, followed by the founding of Santa Cruz by

Alonso de Ojeda

Alonso de Ojeda (; c. 1466 – c. 1515) was a Spanish explorer, governor and conquistador. He travelled through modern-day Guyana, Venezuela, Trinidad, Tobago, Curaçao, Aruba and Colombia. He navigated with Amerigo Vespucci who is famous ...

in present-day

Guajira peninsula

The Guajira Peninsula ( es, Península de La Guajira, links=no, also spelled ''Goajira'', mainly in colonial period texts, guc, Hikükariby) is a peninsula in northern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela in the Caribbean. It is the northernm ...

.

Cumaná

Cumaná () is the capital city of Venezuela's Sucre State. It is located east of Caracas. Cumaná was one of the first cities founded by Spain in the mainland Americas and is the oldest continuously-inhabited Hispanic-established city in South ...

in Venezuela was the first permanent settlement founded by

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

ans in the mainland

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, in 1501 by

Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ol ...

s, but due to successful attacks by the indigenous people, it had to be refounded several times, until

Diego Hernández de Serpa

Diego Hernández de Serpa (; 1510 – May 10, 1570) was a Spaniards, Spanish conquistador and explorer, who under the patronage of Philip II of Spain was part of the European conquest and colonization of the New Andalusia Province (Venezuela regio ...

's foundation in 1569. The Spanish founded San Sebastián de Uraba in 1509 but abandoned it within the year. There is indirect evidence that the first permanent Spanish mainland settlement established in the Americas was

Santa María la Antigua del Darién

Santa María la Antigua del Darién—turned into Dariena in the Latin of Decades of the New World, De Orbo Novo—was a Spanish colonization of the Americas, Spanish colonial town founded in 1510 by Vasco Núñez de Balboa, located in present-d ...

.

Spaniards spent over 25 years in the Caribbean where their initial high hopes of dazzling wealth gave way to continuing exploitation of disappearing indigenous populations, exhaustion of local gold mines, initiation of

cane sugar

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

cultivation as an export product, and importation of African slaves as a labor force. Spaniards continued to expand their presence in the circum-Caribbean region with expeditions. One was by

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba Francisco Hernández de Córdoba may refer to:

* Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (Yucatán conquistador) (died 1517)

* Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (founder of Nicaragua) (died 1526)

{{hndis, name=Hernandez de Cordoba, Francisco ...

in 1517, another by

Juan de Grijalva

Juan de Grijalva (; born c. 1490 in Cuéllar, Crown of Castile – 21 January 1527 in Honduras) was a Spanish conquistador, and a relative of Diego Velázquez.Diaz, B., 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, He went to Hispa ...

in 1518, which brought promising news of possibilities there. Even by the mid-1510s, the western Caribbean was largely unexplored by Spaniards. A well-connected settler in Cuba,

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

received authorization in 1519 by the governor of Cuba to form an expedition of exploration-only to this far western region. That expedition was to make world history.

Mexico

It wasn’t until Spanish expansion into modern-day Mexico that Spanish explorers were able to find wealth on the scale that they had been hoping for. Unlike Spanish expansion in the Caribbean, which involved limited armed combat and sometimes the participation of indigenous allies, the conquest of central Mexico was protracted and necessitated indigenous allies who chose to participate for their own purposes. The conquest of the Aztec empire involved the combined effort of armies from many indigenous allies, spearheaded by a small Spanish force of conquistadors. The Aztecs did not govern over an empire in the conventional sense, but were the hegemons of a confederation of dozens of city-states, tribes and other polities; the status of each varied from harshly subjugated to closely allied. The Spaniards persuaded the leaders of Aztec vassals and

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 60 municipaliti ...

(a city-state never conquered by the Aztecs), to ally with them against the Aztecs. Through such methods, the Spaniards came to accumulate a massive force of thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of indigenous warriors. Records of the conquest of central Mexico include accounts by the expedition leader Hernán Cortés,

Bernal Díaz del Castillo

Bernal Díaz del Castillo ( 1492 – 3 February 1584) was a Spanish conquistador, who participated as a soldier in the conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and late in his life wrote an account of the events. As an experienced ...

and other Spanish conquistadors, indigenous allies from the city-states

altepetl

The (, plural ''altepeme'' or ''altepemeh'') was the local, ethnically-based political entity, usually translated into English as "city-state," of pre-Columbian Nahuatl-speaking societiesSmith 1997 p. 37 in the Americas. The ''altepetl'' was co ...

of Tlaxcala,

Texcoco, and Huexotzinco. In addition, indigenous accounts were written by the defeated from the Aztec capital,

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

, a case of history being written by those other than the victors.

The capture of the Aztec emperor

Moctezuma II

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin ( – 29 June 1520; oteːkˈsoːmaḁ ʃoːkoˈjoːt͡sĩn̥), nci-IPA, Motēuczōmah Xōcoyōtzin, moteːkʷˈsoːma ʃoːkoˈjoːtsin variant spellings include Motewksomah, Motecuhzomatzin, Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecu ...

, by Cortés was not a brilliant stroke of innovation, but came from the playbook that the Spanish developed during their period in the Caribbean. The composition of the expedition was the standard pattern, with a senior leader, and participating men investing in the enterprise with the full expectation of rewards if they did not lose their lives. Cortés’s seeking indigenous allies was a typical tactic of warfare: divide and conquer. But the indigenous allies had much to gain by throwing off Aztec rule. For the Spaniards’ Tlaxcalan allies, their crucial support gained them enduring political legacy into the modern era, the Mexican state of Tlaxcala.

The conquest of central Mexico sparked further Spanish conquests, following the pattern of conquered and consolidated regions being the launching point for further expeditions. These were often led by secondary leaders, such as

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucatá ...

. Later conquests in Mexico were protracted campaigns with less immediate results than the conquest of the Aztec empire. The

Spanish conquest of Yucatán

The Spanish conquest of Yucatán was the campaign undertaken by the Spanish ''conquistadores'' against the Late Postclassic Maya states and polities in the Yucatán Peninsula, a vast limestone plain covering south-eastern Mexico, northern Gu ...

, the

Spanish conquest of Guatemala

In a protracted conflict during the Spanish colonization of the Americas, Spanish colonisers gradually incorporated the territory that became the modern country of Guatemala into the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain. Before the conquest, this te ...

, the conquest of the

Purépecha

The Purépecha (endonym pua, P'urhepecha ) are a group of indigenous people centered in the northwestern region of Michoacán, Mexico, mainly in the area of the cities of Cherán and Pátzcuaro.

They are also known by the pejorative "Tarascan ...

of Michoacan, the

war of Mexico's west, and the

Chichimeca War

The Chichimeca War (1550–90) was a military conflict between the Spanish Empire and the Chichimeca Confederation established in the territories today known as the Central Mexican Plateau, called by the Conquistadores La Gran Chichimeca. The ...

in northern Mexico expanded Spanish control over territory and indigenous populations stretching thousands of miles. Not until the

victory over the Incan Empire, using similar tactics, in 1532, was the conquest of the Aztecs matched in scale of either territory or treasure.

Peru

In 1532 at the

Battle of Cajamarca

The Battle of Cajamarca also spelled Cajamalca (though many contemporary scholars prefer to call it Massacre of Cajamarca) was the ambush and seizure of the Inca ruler Atahualpa by a small Spanish force led by Francisco Pizarro, on November 16, 1 ...

a group of Spaniards under

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

and their

indigenous Andean Indian auxiliaries

Indian auxiliaries were those indigenous peoples of the Americas who allied with Spain and fought alongside the conquistadors during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. These auxiliaries acted as guides, translators and porters, and in the ...

native allies ambushed and captured the Emperor

Atahualpa

Atahualpa (), also Atawallpa (Quechua), Atabalica, Atahuallpa, Atabalipa (c. 1502 – 26-29 July 1533) was the last Inca Emperor. After defeating his brother, Atahualpa became very briefly the last Sapa Inca (sovereign emperor) of the Inca Empir ...

of the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

. It was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting to subdue the mightiest

empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

. In the following years, Spain extended its rule over the Empire of the

Inca civilization

The Incas were most notable for establishing the Inca Empire in Pre-Columbian America, which was centered in modern day South America in Peru and Chile. It was about 2,500 miles from the northern to southern tip. The civilization lasted from 14 ...

.

The Spanish took advantage of a recent civil war between the factions of the two brothers Emperor

Atahualpa

Atahualpa (), also Atawallpa (Quechua), Atabalica, Atahuallpa, Atabalipa (c. 1502 – 26-29 July 1533) was the last Inca Emperor. After defeating his brother, Atahualpa became very briefly the last Sapa Inca (sovereign emperor) of the Inca Empir ...

and

Huáscar

Huáscar Inca (; Quechua: ''Waskar Inka''; 1503–1532) also Guazcar was Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire from 1527 to 1532. He succeeded his father, Huayna Capac and his brother Ninan Cuyochi, both of whom died of smallpox while campaigning near Qui ...

, and the enmity of

indigenous nations the Incas had subjugated, such as the

Huancas,

Chachapoyas, and

Cañari

The Cañari (in Kichwa: Kañari) are an indigenous ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the territory of the modern provinces of Azuay and Cañar in Ecuador. They are descended from the independent pre-Columbian tribal confederation of the s ...

s. In the following years the

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

s and indigenous allies extended control over Greater Andes Region. The Viceroyalty of Perú was established in 1542. The

last Inca stronghold was conquered by the Spanish in 1572.

Peru was the last territory in the continent under Spanish rule, which ended on 9 December 1824 at the Battle of Ayacucho (Spanish rule continued until 1898 in Cuba and Puerto Rico).

Chile

Chile was explored by Spaniards based in Peru, where Spaniards found the fertile soil and

mild climate attractive. The

Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

people of Chile, whom the Spaniards called

Araucanian

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

s, resisted fiercely. The Spanish did establish the settlement of

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

in 1541, founded by

Pedro de Valdivia

Pedro Gutiérrez de Valdivia or Valdiva (; April 17, 1497 – December 25, 1553) was a Spanish conquistador and the first royal governor of Chile. After serving with the Spanish army in Italy and Flanders, he was sent to South America in 1534, whe ...

.

[

Southward colonization by the Spanish in Chile halted after the conquest of ]Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

in 1567. This is thought to have been the result of an increasingly harsh climate to the south, and the lack of a populous and sedentary indigenous population to settle among for the Spanish in the fjords and channels of Patagonia.Destruction of the Seven Cities

The Destruction of the Seven Cities ( es, Destrucción de las siete ciudades) is a term used in Chilean historiography to refer to the destruction or abandonment of seven major Spanish outposts in southern Chile around 1600, caused by the Mapuc ...

in 1599–1604.[ This Mapuche victory laid the foundation for the establishment of a Spanish-Mapuche frontier called La Frontera. Within this frontier the city of Concepción assumed the role of "military capital" of Spanish-ruled Chile.][Collier, Simon. "Chile: Colonial Foundations" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 2, p. 99.]

New Granada

Between 1537 and 1543, six Spanish expeditions entered highland Colombia, conquered the

Between 1537 and 1543, six Spanish expeditions entered highland Colombia, conquered the Muisca Confederation

The Muisca Confederation was a loose confederation of different Muisca rulers (''zaques'', ''zipas'', '' iraca'', and ''tundama'') in the central Andean highlands of present-day Colombia before the Spanish conquest of northern South America. The ...

, and set up the New Kingdom of Granada

The New Kingdom of Granada ( es, Nuevo Reino de Granada), or Kingdom of the New Granada, was the name given to a group of 16th-century Spanish colonial provinces in northern South America governed by the president of the Royal Audience of Santa ...

( es, Nuevo Reino de Granada). Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada y Rivera, also spelled as Ximénez and De Quezada, (;1496 16 February 1579) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador in northern South America, territories currently known as Colombia. He explored the territory named ...

was the leading conquistador with his brother Hernán second in command. It was governed by the president of the Audiencia of Bogotá

The New Kingdom of Granada ( es, Nuevo Reino de Granada), or Kingdom of the New Granada, was the name given to a group of 16th-century Spanish colonial provinces in northern South America governed by the president of the Royal Audience of Santa ...

, and comprised an area corresponding mainly to modern-day Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

and parts of Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

. The conquistadors

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

originally organized it as a captaincy general

A captaincy ( es, capitanía , pt, capitania , hr, kapetanija) is a historical administrative division of the former Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires. It was instituted as a method of organization, directly associated with the home-rule a ...

within the Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed from ...

. The crown established the '' audiencia'' in 1549. Ultimately, the kingdom became part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of New Granada ( es, Virreinato de Nueva Granada, links=no ) also called Viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada or Viceroyalty of Santafé was the name given on 27 May 1717, to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in norther ...

first in 1717 and permanently in 1739. After several attempts to set up independent states in the 1810s, the kingdom and the viceroyalty ceased to exist altogether in 1819 with the establishment of Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

.

Venezuela

Venezuela was first visited by Europeans during the 1490s, when Columbus was in control of the region, and the region as a source for indigenous slaves for Spaniards in Cuba and Hispaniola, since the Spanish destruction of the local indigenous population. There were few permanent settlements, but Spaniards settled the coastal islands of Cubagua

Cubagua Island or Isla de Cubagua () is the smallest and least populated of the three islands constituting the Venezuelan state of Nueva Esparta, after Margarita Island and Coche Island. It is located north of the Araya Peninsula, the closest ...

and Margarita

A margarita is a cocktail consisting of Tequila, triple sec, and lime juice often served with salt on the rim of the glass. The drink is served shaken with ice (on the rocks), blended with ice (frozen margarita), or without ice (straight up). T ...

to exploit the pearl beds. Western Venezuela’s history took an atypical direction in 1528, when Spain’s first Hapsburg monarch, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

granted rights to colonize to the German banking family of the Welser

Welser was a Germans, German banking and merchant family, originally a patrician (post-Roman Europe), patrician family based in Augsburg and Nuremberg, that rose to great prominence in international high finance in the 16th century as bankers t ...

s. Charles sought to be elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a populatio ...

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

and was willing to pay whatever it took to achieve that. He became deeply indebted to the German Welser

Welser was a Germans, German banking and merchant family, originally a patrician (post-Roman Europe), patrician family based in Augsburg and Nuremberg, that rose to great prominence in international high finance in the 16th century as bankers t ...

and Fugger

The House of Fugger () is a German upper bourgeois family that was historically a prominent group of European bankers, members of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century mercantile patriciate of Augsburg, international mercantile bankers, and vent ...

banking families. To satisfy his debts to the Welsers, he granted them the right to colonize and exploit western Venezuela, with the proviso that they found two towns with 300 settlers each and construct fortifications. They established the colony of Klein-Venedig

(Little Venice) or Welserland (pronunciation �vɛl.zɐ.lant was the most significant territory of the German colonization of the Americas, from 1528 to 1546, in which the Welser banking and patrician family of the Free Imperial Cities of Pr ...

in 1528. They founded the towns of Coro

Coro or CORO may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Coro'' (Berio), a composition by Luciano Berio

* Coro (music), Italian for choir

* Coro TV, Venezuelan community television channel

* Omweso (Coro), mancala game played in the Lango region of Uganda

* ...

and Maracaibo

)

, motto = "''Muy noble y leal''"(English: "Very noble and loyal")

, anthem =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_alt = ...

. They were aggressive in making their investment pay, alienating the indigenous populations and Spaniards alike. Charles revoked the grant in 1545, ending the episode of German colonization.

Río de la Plata and Paraguay

Argentina was not conquered or later exploited in the grand fashion of central Mexico or Peru, since the indigenous population was sparse and there were no precious metals or other valuable resources. Although today

Argentina was not conquered or later exploited in the grand fashion of central Mexico or Peru, since the indigenous population was sparse and there were no precious metals or other valuable resources. Although today Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

at the mouth of Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and fo ...

is a major metropolis, it held no interest for Spaniards and the 1535-36 settlement failed and was abandoned by 1541. Pedro de Mendoza

Pedro de Mendoza () (c. 1499 – June 23, 1537) was a Spanish ''conquistador'', soldier and explorer, and the first ''adelantado'' of New Andalusia.

Setting sail

Pedro de Mendoza was born in Guadix, Grenada, part of a large noble family that ...

and Domingo Martínez de Irala

Domingo Martínez de Irala (; c. 1509 Bergara, Gipuzkoa – c. 1556 Asunción, Paraguay) was a Spanish Basque conquistador.

He headed for America in 1535 enrolled in the expedition of Pedro de Mendoza and participated in the founding of Buenos ...

, who led the original expedition, went inland and founded Asunción, Paraguay, which became the Spaniards' base. A second (and permanent) settlement was established in 1580 by Juan de Garay

Juan de Garay (1528–1583) was a Spanish conquistador.

Garay's birthplace is disputed. Some say it was in the city of Junta de Villalba de Losa in Castile, while others argue he was born in the area of Orduña (Basque Country). There's ...

, who arrived by sailing down the Paraná River

The Paraná River ( es, Río Paraná, links=no , pt, Rio Paraná, gn, Ysyry Parana) is a river in south-central South America, running through Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina for some ."Parana River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Br ...

from Asunción

Asunción (, , , Guarani: Paraguay) is the capital and the largest city of Paraguay.

The city stands on the eastern bank of the Paraguay River, almost at the confluence of this river with the Pilcomayo River. The Paraguay River and the Bay of ...

, now the capital of Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

. Exploration from Peru resulted in the foundation of Tucumán in what is now northwest Argentina.

End of era of exploration

The spectacular conquests of central Mexico (1519–21) and Peru (1532) sparked Spaniards' hopes of finding yet another high civilization. Expeditions continued into the 1540s and regional capitals founded by the 1550s. Among the most notable expeditions are

The spectacular conquests of central Mexico (1519–21) and Peru (1532) sparked Spaniards' hopes of finding yet another high civilization. Expeditions continued into the 1540s and regional capitals founded by the 1550s. Among the most notable expeditions are Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

into southeast North America, leaving from Cuba (1539–42); Francisco Vázquez de Coronado

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y Luján (; 1510 – 22 September 1554) was a Spanish conquistador and explorer who led a large expedition from what is now Mexico to present-day Kansas through parts of the southwestern United States between 15 ...

to northern Mexico (1540–42), and Gonzalo Pizarro

Gonzalo Pizarro y Alonso (; 1510 – April 10, 1548) was a Spanish conquistador and younger paternal half-brother of Francisco Pizarro, the conqueror of the Inca Empire. Bastard son of Captain Gonzalo Pizarro y Rodríguez de Aguilar (senior) (14 ...

to Amazonia, leaving from Quito, Ecuador (1541–42). In 1561, Pedro de Ursúa

Pedro de Ursúa (1526 – 1561) was a Spanish conquistador from Baztan in Navarre. He is best known for his final trip with Lope de Aguirre in search for El Dorado, where he found death in a plot.

He was born in Arizkun, Baztan, to a Beaum ...

led an expedition of some 370 Spanish (including women and children) into Amazonia to search for El Dorado. Far more famous now is Lope de Aguirre

Lope de Aguirre (; 8 November 1510 – 27 October 1561) was a Basque Spanish conquistador who was active in South America. Nicknamed ''El Loco'' ("the Madman"), he styled himself "Wrath of God, Prince of Freedom." Aguirre is best known for his fi ...

, who led a mutiny against Ursúa, who was murdered. Aguirre subsequently wrote a letter to Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

bitterly complaining about the treatment of conquerors like himself in the wake of the assertion of crown control over Peru. An earlier expedition that left in 1527 was led by Pánfilo Naváez, who was killed early on. Survivors continued to travel among indigenous groups in the North American south and southwest until 1536. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (; 1488/90/92"Cabeza de Vaca, Alvar Núñez (1492?-1559?)." American Eras. Vol. 1: Early American Civilizations and Exploration to 1600. Detroit: Gale, 1997. 50-51. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 10 Decembe ...

was one of four survivors of that expedition, writing an account of it. The crown later sent him to Asunción

Asunción (, , , Guarani: Paraguay) is the capital and the largest city of Paraguay.

The city stands on the eastern bank of the Paraguay River, almost at the confluence of this river with the Pilcomayo River. The Paraguay River and the Bay of ...

, Paraguay to be adelantado

''Adelantado'' (, , ; meaning "advanced") was a title held by Spanish nobles in service of their respective kings during the Middle Ages. It was later used as a military title held by some Spain, Spanish ''conquistadores'' of the 15th, 16th and 17 ...

there. Expeditions continued to explore territories in hopes of finding another Aztec or Inca empire, with no further success. Francisco de Ibarra

Francisco de Ibarra (1539 –June 3, 1575) was a Spanish-Basque explorer, founder of the city of Durango, and governor of the Spanish province of Nueva Vizcaya, in present-day Durango and Chihuahua.

Biography

Francisco de Ibarra was born a ...

led an expedition from Zacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

in northern New Spain, and founded Durango

Durango (), officially named Estado Libre y Soberano de Durango ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Durango; Tepehuán: ''Korian''; Nahuatl: ''Tepēhuahcān''), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico, situated in ...

. Juan de Oñate

Juan de Oñate y Salazar (; 1550–1626) was a Spanish conquistador from New Spain, explorer, and colonial governor of the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México in the viceroyalty of New Spain. He led early Spanish expeditions to the Great Pla ...

, is sometimes referred to as "the Last Conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

", expanded Spanish sovereignty over what is now New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

. Like previous conquistadors, Oñate engaged in widespread abuses of the Indian population. Shortly after founding Santa Fe, Oñate was recalled to Mexico City by the Spanish authorities. He was subsequently tried and convicted of cruelty to both natives and colonists and banished from New Mexico for life.

Factors affecting Spanish settlement

Two major factors affected the density of Spanish settlement in the long term. One was the presence or absence of dense, hierarchically organized indigenous populations that could be made to work. The other was the presence or absence of an exploitable resource for the enrichment of settlers. Best was gold, but silver was found in abundance.

The two main areas of Spanish settlement after 1550 were Mexico and Peru, the sites of the Aztec and Inca indigenous civilizations. Equally important, rich deposits of the valuable metal silver. Spanish settlement in Mexico “largely replicated the organization of the area in preconquest times” while in Peru, the center of the Incas was too far south, too remote, and at too high an altitude for the Spanish capital. The capital

Two major factors affected the density of Spanish settlement in the long term. One was the presence or absence of dense, hierarchically organized indigenous populations that could be made to work. The other was the presence or absence of an exploitable resource for the enrichment of settlers. Best was gold, but silver was found in abundance.

The two main areas of Spanish settlement after 1550 were Mexico and Peru, the sites of the Aztec and Inca indigenous civilizations. Equally important, rich deposits of the valuable metal silver. Spanish settlement in Mexico “largely replicated the organization of the area in preconquest times” while in Peru, the center of the Incas was too far south, too remote, and at too high an altitude for the Spanish capital. The capital Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

was built near the Pacific coast. The capitals of Mexico and Peru, Mexico City and Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

came to have large concentrations of Spanish settlers and became the hubs of royal and ecclesiastical administration, large commercial enterprises and skilled artisans, and centers of culture. Although Spaniards had hoped to find vast quantities of gold, the discovery of large quantities of silver became the motor of the Spanish colonial economy, a major source of income for the Spanish crown, and transformed the international economy. Mining regions in both Mexico were remote, outside the zone of indigenous settlement in central and southern Mexico Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

, but mines in Zacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

(founded 1548) and Guanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

(founded 1548) were key hubs in the colonial economy. In Peru, silver was found in a single silver mountain, the Cerro Rico de Potosí, still producing silver in the 21st century. Potosí (founded 1545) was in the zone of dense indigenous settlement, so that labor could be mobilized on traditional patterns to extract the ore. An important element for productive mining was mercury for processing high-grade ore. Peru had a source in Huancavelica

Huancavelica () or Wankawillka in Quechua is a city in Peru. It is the capital of the department of Huancavelica and according to the 2017 census had a population of 49,570 people. The city was established on August 5, 1572 by the Viceroy ...

(founded 1572), while Mexico had to rely on mercury imported from Spain.

Establishment of early settlements

The Spanish founded towns in the Caribbean, on Hispaniola and Cuba, on a pattern that became spatially similar throughout Spanish America. A central plaza had the most important buildings on the four sides, especially buildings for royal officials and the main church. A checkerboard pattern radiated outward. Residences of the officials and elites were closest to the main square. Once on the mainland, where there were dense indigenous populations in urban settlements, the Spanish could build a Spanish settlement on the same site, dating its foundation to when that occurred. Often they erected a church on the site of an indigenous temple. They replicated the existing indigenous network of settlements, but added a port city. The Spanish network needed a port city so that inland settlements could be connected by sea to Spain. In Mexico, Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

and the men of his expedition founded of the port town of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

in 1519 and constituted themselves as the town councilors, as a means to throw off the authority of the governor of Cuba, who did not authorize an expedition of conquest. Once the Aztec empire was toppled, they founded Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

on the ruins of the Aztec capital. Their central official and ceremonial area was built on top of Aztec palaces and temples. In Peru, Spaniards founded the city of Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

as their capital and its nearby port of Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists o ...

, rather than the high-altitude site of Cuzco

Cusco, often spelled Cuzco (; qu, Qusqu ()), is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; ...

, the center of Inca rule. Spaniards established a network of settlements in areas they conquered and controlled. Important ones include Santiago de Guatemala

Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala ("St. James of the Knights of Guatemala") was the name given to the capital city of the Spanish colonial Captaincy General of Guatemala in Central America.

History

;Quauhtemallan — Guatemala

:The name was ...

(1524); Puebla

Puebla ( en, colony, settlement), officially Free and Sovereign State of Puebla ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Puebla), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 217 municipalities and its cap ...

(1531); Querétaro

Querétaro (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Querétaro ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Querétaro, links=no; Otomi language, Otomi: ''Hyodi Ndämxei''), is one of the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 federal entities of Mexico. I ...

(ca. 1531); Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the list of states of Mexico, state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Me ...

(1531–42); Valladolid (now Morelia

Morelia (; from 1545 to 1828 known as Valladolid) is a city and municipal seat of the municipality of Morelia in the north-central part of the state of Michoacán in central Mexico. The city is in the Guayangareo Valley and is the capital and larg ...

), (1529–41); Antequera (now Oaxaca

Oaxaca ( , also , , from nci, Huāxyacac ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Oaxaca), is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of Mexico. It is ...

(1525–29); Campeche

Campeche (; yua, Kaampech ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Campeche ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Campeche), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. Located in southeast Mexico, it is bordered by ...

(1541); and Mérida. In southern Central and South America, settlements were founded in Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

(1519); León, Nicaragua

León () is the second largest city in Nicaragua, after Managua. Founded by the Spanish as Santiago de los Caballeros de León, it is the capital and largest city of León Department. , the municipality of León has an estimated population of 2 ...

(1524); Cartagena (1532); Piura

Piura is a city in northwestern Peru located in the Sechura Desert on the Piura River. It is the capital of the Piura Region and the Piura Province. Its population was 484,475 as of 2017.

It was here that Spanish Conqueror Francisco Pizarro fou ...

(1532); Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

(1534); Trujillo (1535); Cali

Santiago de Cali (), or Cali, is the capital of the Valle del Cauca department, and the most populous city in southwest Colombia, with 2,227,642 residents according to the 2018 census. The city spans with of urban area, making Cali the second ...

(1537) Bogotá

Bogotá (, also , , ), officially Bogotá, Distrito Capital, abbreviated Bogotá, D.C., and formerly known as Santa Fe de Bogotá (; ) during the Spanish period and between 1991 and 2000, is the capital city of Colombia, and one of the larges ...

(1538); Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

(1534); Cuzco

Cusco, often spelled Cuzco (; qu, Qusqu ()), is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; ...

1534); Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

(1535); Tunja

Tunja () is a city on the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes, in the region known as the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 130 km northeast of Bogotá. In 2018 it had a population of 172,548 inhabitants. It is the capital of Boyacá department an ...

, (1539); Huamanga

Ayacucho (, qu, Ayak'uchu) is the capital city of Ayacucho Region and of Huamanga Province, Ayacucho Region, Peru.

During the Inca Empire and Viceroyalty of Peru periods the city was known by the name of Huamanga (Quechua: Wamanga), and it c ...

(1539); Arequipa

Arequipa (; Aymara and qu, Ariqipa) is a city and capital of province and the eponymous department of Peru. It is the seat of the Constitutional Court of Peru and often dubbed the "legal capital of Peru". It is the second most populated city ...

(1540); Santiago de Chile

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

(1544) and Concepción, Chile

Concepción (; originally: ''Concepción de la Madre Santísima de la Luz'', "Conception of the Blessed Mother of Light") is a city and commune in central Chile, and the geographical and demographic core of the Greater Concepción metropolitan a ...

(1550). Settled from the south were Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

(1536, 1580); Asunción

Asunción (, , , Guarani: Paraguay) is the capital and the largest city of Paraguay.

The city stands on the eastern bank of the Paraguay River, almost at the confluence of this river with the Pilcomayo River. The Paraguay River and the Bay of ...

(1537); Potosí

Potosí, known as Villa Imperial de Potosí in the colonial period, is the capital city and a municipality of the Department of Potosí in Bolivia. It is one of the highest cities in the world at a nominal . For centuries, it was the location o ...

(1545); La Paz, Bolivia

La Paz (), officially known as Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Spanish pronunciation: ), is the seat of government of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. With an estimated 816,044 residents as of 2020, La Paz is the third-most populous city in Bol ...

(1548); and Tucumán (1553).

Ecological conquests

The Columbian Exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

was as significant as the clash of civilizations. Arguably the most significant introduction was diseases brought to the Americas, which devastated indigenous populations in a series of epidemics. The loss of indigenous population had a direct impact on Spaniards as well, since increasingly they saw those populations as a source of their own wealth, disappearing before their eyes.

In the first settlements in the Caribbean, the Spaniards deliberately brought animals and plants that transformed the ecological landscape. Pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, and chickens allowed Spaniards to eat a diet with which they were familiar. But the importation of horses transformed warfare for both the Spaniards and the indigenous. Where the Spaniards had exclusive access to horses in warfare, they had an advantage over indigenous warriors on foot. They were initially a scarce commodity, but horse breeding became an active industry. Horses that escaped Spanish control were captured by indigenous; many indigenous also raided for horses. Mounted indigenous warriors were significant foes for Spaniards. The Chichimeca in northern Mexico, the Comanche in the northern Great Plains and the

In the first settlements in the Caribbean, the Spaniards deliberately brought animals and plants that transformed the ecological landscape. Pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, and chickens allowed Spaniards to eat a diet with which they were familiar. But the importation of horses transformed warfare for both the Spaniards and the indigenous. Where the Spaniards had exclusive access to horses in warfare, they had an advantage over indigenous warriors on foot. They were initially a scarce commodity, but horse breeding became an active industry. Horses that escaped Spanish control were captured by indigenous; many indigenous also raided for horses. Mounted indigenous warriors were significant foes for Spaniards. The Chichimeca in northern Mexico, the Comanche in the northern Great Plains and the Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

in southern Chile and the pampas of Argentina resisted Spanish conquest. For Spaniards, the fierce Chichimecas barred them for exploiting mining resources in northern Mexico. Spaniards waged a fifty-year war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

(ca. 1550-1600) to subdue them, but peace was only achieved by Spaniards’ making significant donations of food and other commodities the Chichimeca demanded. "Peace by purchase" ended the conflict. In southern Chile and the pampas, the Araucanians

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sh ...

(Mapuche) prevented further Spanish expansion. The image of mounted Araucanians capturing and carrying off white women was the embodiment of Spanish ideas of civilization and barbarism.

Cattle multiplied quickly in areas where little else could turn a profit for Spaniards, including northern Mexico and the Argentine pampas. The introduction of sheep production was an ecological disaster in places where they were raised in great numbers, since they ate vegetation to the ground, preventing the regeneration of plants.

The Spanish brought new crops for cultivation. They preferred wheat cultivation to indigenous sources of carbohydrates: casava, maize (corn), and potatoes, initially importing seeds from Europe and planting in areas where plow agriculture could be utilized, such as the Mexican Bajío

El Bajío (the ''lowland'') is a cultural and geographical region within the central Mexican plateau which roughly spans from north-west of the Mexico City metropolitan area to the main silver mines in the northern-central part of the country. Thi ...

. They also imported cane sugar

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

, which was a high-value crop in early Spanish America. Spaniards also imported citrus trees, establishing orchards of oranges, lemons, and limes, and grapefruit. Other imports were figs, apricots, cherries, pears, and peaches among others. The exchange did not go one way. Important indigenous crops that transformed Europe were the potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

and maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

, which produced abundant crops that led to the expansion of populations in Europe. Chocolate

Chocolate is a food made from roasted and ground cacao seed kernels that is available as a liquid, solid, or paste, either on its own or as a flavoring agent in other foods. Cacao has been consumed in some form since at least the Olmec civ ...

(Nahuatl: chocolate) and vanilla

Vanilla is a spice derived from orchids of the genus ''Vanilla (genus), Vanilla'', primarily obtained from pods of the Mexican species, flat-leaved vanilla (''Vanilla planifolia, V. planifolia'').

Pollination is required to make the p ...

were cultivated in Mexico and exported to Europe. Among the foodstuffs that became staples in European cuisine and could be grown there were tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

es, squashes, bell peppers

The bell pepper (also known as paprika, sweet pepper, pepper, or capsicum ) is the fruit of plants in the Grossum Group of the species ''Capsicum annuum''. Cultivars of the plant produce fruits in different colors, including red, yellow, orange ...

, and to a lesser extent in Europe chili peppers; also nuts of various kinds: Walnut

A walnut is the edible seed of a drupe of any tree of the genus ''Juglans'' (family Juglandaceae), particularly the Persian or English walnut, '' Juglans regia''.

Although culinarily considered a "nut" and used as such, it is not a true ...

s, cashew

The cashew tree (''Anacardium occidentale'') is a tropical evergreen tree native to South America in the genus ''Anacardium'' that produces the cashew seed and the cashew apple accessory fruit. The tree can grow as tall as , but the dwarf cult ...

s, pecan

The pecan (''Carya illinoinensis'') is a species of hickory native to the southern United States and northern Mexico in the region of the Mississippi River. The tree is cultivated for its seed in the southern United States, primarily in Georgia, ...

s, and peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible Seed, seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics, important to both small ...

s.

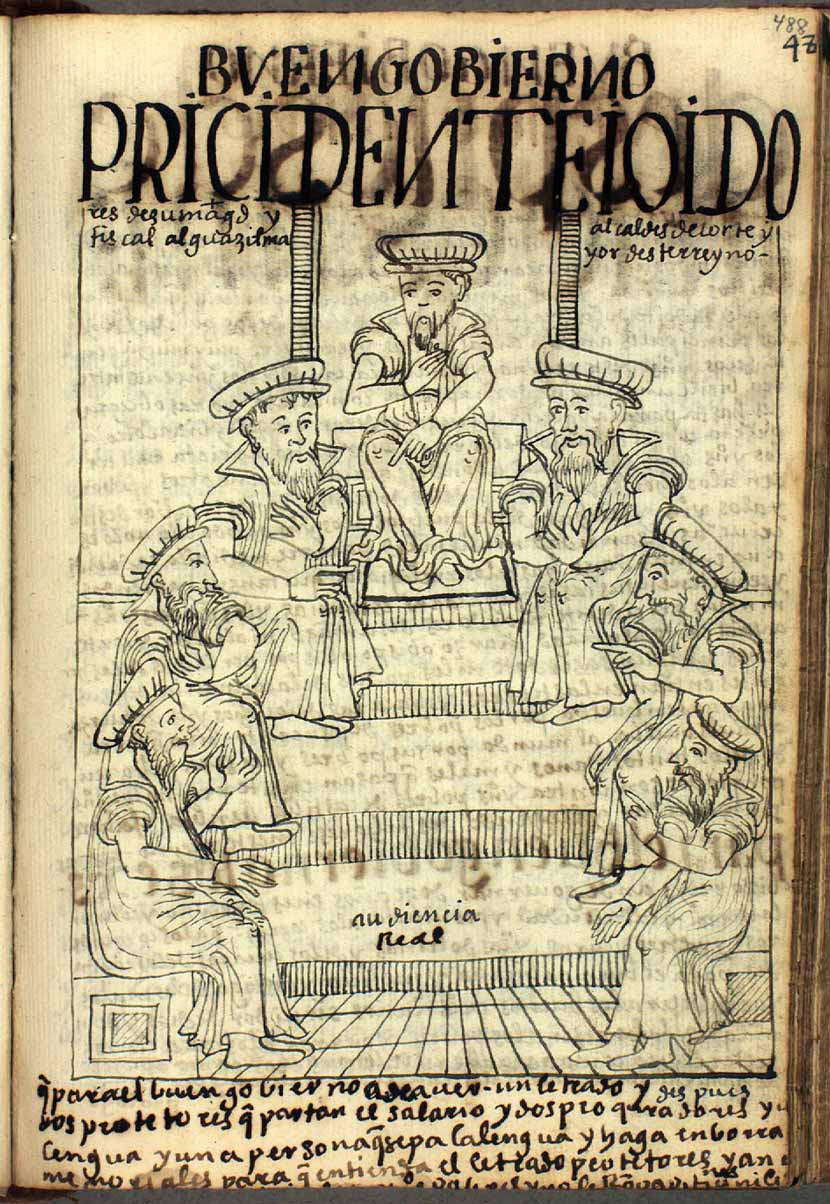

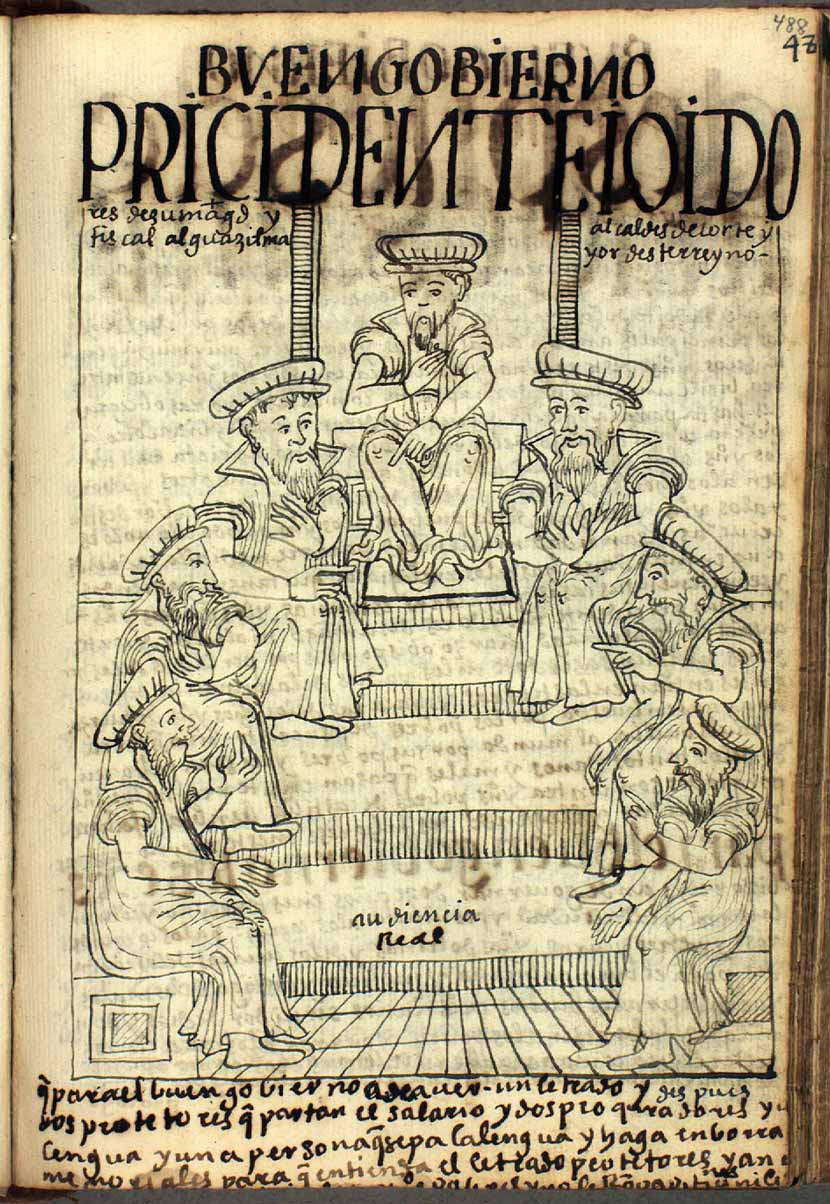

Civil governance

The empire in the Indies was a newly established dependency of the kingdom of Castile alone, so crown power was not impeded by any existing

The empire in the Indies was a newly established dependency of the kingdom of Castile alone, so crown power was not impeded by any existing cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places