Computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW) is the study of how people utilize technology collaboratively, often towards a shared goal. CSCW addresses how

Computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW) is the study of how people utilize technology collaboratively, often towards a shared goal. CSCW addresses how History

The origins of CSCW as a field are intertwined with the rise and subsequent fall of office automation as response to some of the criticisms, particularly the failure to address the impact human psychological and social behaviors can have. Greif and Cashman created the term CSCW to help employees seeking to further their work with technology. A few years later, in 1987, Charles Findley presented the concept of collaborative learning-work.Joseph A. Carpini, Sharon K. Parker and Mark A. Griffin, 20 March 2017. "A Look Back and a Leap Forward: A Review and Synthesis of the Individual Work Performance Literature" ''Academy of Management Annals'', Vol. 11, No. 2 Computer-supported cooperative work is an interdisciplinary research area of growing interest which relatesCentral concerns and concepts

CSCW is a design-oriented academic field that is interdisciplinary in nature and brings together librarians, economists,Articulation work

Articulation work is essentially the work that makes other work exist and possible. It is an effort made to make other work easier, more manageable, and can either be planned or unplanned. Therefore articulation work is an integral part of software process since software processes can sometimes fail or break down. Articulation work is also commonly known as "invisible work" since it is not always noticed. The concept was introduced by Anselm Strauss. He described it as a way to observe the "nature of mutually dependent actors in their division of labour".Peiwei Mi and W. Scacchi, "Modeling Articulation Work in Software Engineering Processes," in ''Proceedings. First International Conference on the Software Process,'', Redondo Beach, Calif., 1991 pp. 188–201. doi: 10.1109/ICSP.1991.664349 It was introduced in CSCW by Schmidt and Bannon in 1992, where it would be applied to more realistic work scenarios in society. Articulation work is inherent in collaboration. The idea of articulation work was initially used in relation to computer-supported cooperative work, but it was travelled through other domains of work, such as healthcare. Initially, articulation work was known for scheduling and allocation of resources, but now, extends beyond that. Articulation work can also be seen as the response developers make to adapt to changes due to error or misjudgments in the real world.Fjuk, Annita & Nurminen, Markku & Smørdal, Ole & Centre, Turku. (2002). Taking Articulation Work Seriously – an Activity Theoretical Approach. There are various models of articulation work that help identify applicable solutions to recover or reorganize planned activities. It is also important to note that it can vary depending on the scenario. Oftentimes there is an increase in the need for articulation work as the situation becomes more complex. Because articulation work is so abstract, it can be split into two categories from the highest level: individual activity and collective activity. * With individual activity, articulation work is almost always applicable. It is obvious that the subject is required to articulate his / her own work. But when a subject is faced with a new task, there are many questions that must be answered in order to move forward and be successful. This questioning is considered the articulation work to the actual project; invisible, but necessary. There is also articulation of action within an activity. For example, creating to-do lists and blueprints may be imperative to progressing a project. There is also articulation of operation within an action. In terms of software, the user must have adequate knowledge and skill in using computer systems and knowledge about software in order to perform tasks. * In a teamwork setting, articulation is imperative for collective activity. To maximize the efficiency of all the people working, the articulation work must be very solid. Without a solid foundation, the team is unable to collaborate effectively. Furthermore, as the size of the team increases, the articulation work becomes more complex. What goes in between the user and the system is often overlooked. But software process modeling techniques as well as the model of articulation work is imperative in creating a solid foundation that allows for improvement and enhancement. In a way, all work needs to be articulated; there needs to be a who, what, where, when and how. With technology, there are many tools that utilize articulation work. Tasks such as planning and scheduling can be considered articulation work. There are also times when the articulation work is bridging the gap between the technology and the user. Ultimately, articulation work is the means that allows for cooperative work to be cooperative, a main objective of CSCW.Matrix

One of the most common ways of conceptualizing CSCW systems is to consider the context of a system's use. One such conceptualization is the CSCW Matrix, first introduced in 1988 by Johansen; it also appears in Baecker (1995). The matrix considers work contexts along two dimensions: whether collaboration is co-located or geographically distributed, and whether individuals collaborate synchronously (same time) or asynchronously (not depending on others to be around at the same time).Same time/same place – face to face interaction

*Roomware *Shared tables, wall displays * Digital whiteboards * Electronic meeting systems *Single display groupware *Group decision support systemSame time/different place – remote interaction

* Electronic meeting systems *Different time/same place – continuous task (ongoing task)

* Team rooms * Large displays * Post-it * War-roomsDifferent time/different place – communication and coordination

* Electronic meeting systems *Model of Coordinated Action (MoCA)

The Model of Coordinated Action, as a framework for analyzing group collaboration, identifies several dimensions of common features of cooperative work that extend beyond the CSCW matrix and allow for more complexity in describing how teams work given certain conditions. The seven total dimensions that constitute the model (MoCA) are used to describe essential "fields of action" seen in existing CSCW research. Rather than existing as a rigid matrix with distinct quadrants, this model is to be interpreted as multidimensional – each dimension existing as its own continuum. These ends of these dimensions' continuums are defined in the following subsections.Synchronicity

This is pertaining to the time at which the collaborative work occurs. This could range from live meetings conducted at exact times to viewing recordings or responding to messages that do not require one or all participants to be active at the time the recording, message, or other deliverable was created.Physical distribution

This covers the distance in which team members could be geographically separated while still being able to collaborate. The least physically distributed cooperative work is a meeting in which all team members are physically present in the same space and communicating verbally, face-to-face. Conversely, technology now allows for more distanced communication that could extend as far as meeting from multiple countries.Scale

The scale of a collaborative project refers to how many individuals comprise the project team. As the number of people involved increases, the division of tasks must become more intricate and complex to ensure that each participant is contributing in some way.Number of communities of practice

ANascence

Some collaborative projects are designed to be more long-lasting than others, often meaning that their standard practices and actions are more established than newer, less developed projects. Synonymous with "newness", nascence refers to how established a cooperative effort is at a given point in time. While most work is always developing in some way, newer projects will have to spend more time establishing common ground among its team members and will thus have a higher level of nascence.Planned permanence

This dimension encourages teams to establish common practices, terminology, etc. within the group to ensure cohesion and understanding among the work. It is difficult to gauge how long a project will last, therefore establishing these foundations in early stages helps to prevent confusion between group members at later stages when there may be higher stakes or deeper investigation. The notion of planned permanence is essential to the model as it allows for productive communication between individuals who may have different expertise or are members of different communities of practice.Turnover

This dimension is used to describe the rate at which individuals leave a collaborative group. Such events may occur at various rates depending on the impact one's departure may have on the individual and the group. In a well-established collaborative action or a group with a small scale, a team member leaving may have detrimental effects, whereas temporary projects with open membership may have high turnover rates covered by the project's high scale.Considerations for interaction design

Self-presentation

Self-presentation has been studied in traditional face-to-face environments, but as society has embraced content culture, social platforms have generated new affordances for presenting oneself online. Due to technological growth, social platforms, and their increased affordances, society has reconfigured the way users self-present online due to audience input and context collapse.Hollenbaugh, E. E. (2020). Self-Presentation in Social Media: Review and Research Opportunities. Review of Communication Research, 9, 80–98. Received January 2020; revised June 2020; accepted July 2020.

In an online setting, audiences are physically invisible which complicates the users ability to distinguish their intended audience. Audience input, on social platforms, can range from commenting, sharing, liking, tagging, etc. For example,

Self-presentation has been studied in traditional face-to-face environments, but as society has embraced content culture, social platforms have generated new affordances for presenting oneself online. Due to technological growth, social platforms, and their increased affordances, society has reconfigured the way users self-present online due to audience input and context collapse.Hollenbaugh, E. E. (2020). Self-Presentation in Social Media: Review and Research Opportunities. Review of Communication Research, 9, 80–98. Received January 2020; revised June 2020; accepted July 2020.

In an online setting, audiences are physically invisible which complicates the users ability to distinguish their intended audience. Audience input, on social platforms, can range from commenting, sharing, liking, tagging, etc. For example, Affordance

As media platforms proliferate, so do the affordances offered that directly influence how users manage their self-presentation. According to researchers, the three most influential affordances on how users present themselves in an online domain include anonymity, persistence, and visibility. Anonymity in the context of social media refers to the separation of an individual's online and offline identity by making the origin of their messages unspecified. Platforms that support anonymity have users that are more likely to depict their offline self accurately online (i.e Reddit). Comparatively, platforms with less constraints on anonymity are subject to users that portray their online and offline selves differently, thus creating a "Boundary object

A boundary object is an informational item which is used differently by various communities or fields of study and may be a concrete, physical item or an abstract concept. Examples of boundary objects include: * Most research libraries, as different research groups may use different resources from the same libraries. * An interdisciplinary research project, as different business sectors and research groups may have different goals for the project. * The outline of a U.S. state's boundaries, which may be drawn on a roadmap for travelers or on an ecological map for biologists. In computer-supported cooperative work, boundary objects are typically used to study how information and tools are transmitted between different cultures or communities. Some examples of boundary objects in CSCW research are: * Electronic health records, which pass health information between groups with different priorities (such as doctors, nurses, and medical secretaries). * The concept of a "digital work environment", as used in Swedish political debate.Standardization vs. flexibility in CSCW

Standardization is defined as "agile processes that are enforced as a standard protocol across an organization to share knowledge and best practice." Flexibility, on the other hand, is the "ability to customize and evolve processes to suit the aims of an agile team". As CSCW tools, standardization and flexibility are almost mutually exclusive from each other. In CSCW, flexibility comes in two forms, flexibility for future change, and flexibility for interpretation. Everything that is done on the internet has a level of standardization due to the internet standards. In fact, Email has its own set of standards, of which the first draft was created in 1977. No CSCW tool is perfectly flexible, and all lose flexibility in the same three levels. Either flexibility is lost when the programmer makes the toolkit, when the programmer makes the application, and/or when the user uses the application.Standardization in information infrastructure

Information infrastructure requires extensive standardization to make collaboration work. Since data is transferred from company to company and occasionally nation to nation, international standards have been put in place to make communication of data much simpler. Often one company's data will be included in a much larger system, and this would become almost impossible without standardization. With information infrastructure, there is very little flexibility in potential future changes. Due to the fact that the standards have been around for decades and there are hundreds of them, it is nearly impossible to change one standard without greatly affecting the others.Flexibility in toolkits

Creating CSCW toolkits requires flexibility of interpretation; it is important that these tools are generic and can be used in many different ways. Another important part of a toolkit's flexibility is the extensibility, the extent to which new components or tools can be created using the tools provided. An example of a toolkit that is flexible in how generic the tools are is Oval. Oval consists of four components: objects, views, agents, and links. This toolkit was used to recreate four previously existing communication systems: The Coordinator, gIBIS, Lotus Notes, and Information Lens. It proved that, due to its flexibility, Oval was able to create many forms of peer-to-peer communication applications.Applications

Applications in education

There have been three main generations to distance education, starting with the first being through postal service, the second through mass media such as the radio, television, and films, and the third being the current state of e-learning. Technology-enhanced learning, or "e-learning", has been an increasingly relevant topic in education, especially with the development of theCommunity of inquiry framework

E-learning has been explained by the community of inquiry (COI) framework introduced by Garrison et al. In this framework, there are three major elements: cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence. * Cognitive presence in this framework is the measure of how well meaning is able to be constructed from the content being taught. It assumes that students have access to a large network from which to gain information from. This includes peers, instructors, alumni, and practicing professionals. E-learning has allowed this network to be easily accessible through the internet, and these connections can be made synchronously through video, audio, or texts. * Social presence in the community of inquiry framework is how well participants can connect with one another on a social level and present themselves as "real people". Video conferencing has been shown to increase social presence within students. One study found that "social presence in VC irtual Conferencingcan have a positive effect on group efficacy and performance by amplifying group cohesion". This information is greatly useful in designing future systems because it explains the importance of technology like video conferencing in synchronous e-learning. Groups that are able to see each other face to face have a stronger bond and are able to complete tasks faster than those without it. Increasing the social presence in online education environments helps facilitate in the understanding of the content and the ability for the group to solve problems. * Teaching presence in the COI framework contains two main functions: creation of content and the facilitation of this content. The creation of content is usually done by the instructor, but students and instructors can share the role of facilitator, especially in higher education settings. The goal of teaching presence is "to support and enhance social and cognitive presence for the purpose of realizing educational outcome". Virtual educational software and tools are becoming more readily used globally. Remote educational platforms and tools must be accessible for various generations, including children as well as guardians or teachers, yet these frameworks are not adapted to be child-friendly. The lack of interface and design consideration for younger users causes difficulty in potential communication between children and older generations utilizing the software. This in turn leads to a decrease in virtual learning participation as well as potential diminished collaboration with peers. In addition, it may be difficult for older teachers to utilize such technology, and communicate with their students. Similar to orienting older workers with CSCW tools, it is difficult to train younger students or older teachers in utilizing virtual technology, and may not be possible for widely spread virtual classrooms and learning environments.Applications in gaming

Collaborative mixed reality games modify the shared social experience, during which players can interact in real-time with physical and virtual gaming environments and with otherCommunication systems

The group members experience effective communication practices following the availability of a common platform for expressing opinions and coordinating tasks. The technology is applicable not only in professional contexts but also in the gaming world. CSCW usually offers synchronous and asynchronous games to allow multiple individuals to compete in a certain activity across social networks. Thus, the tool has made gaming more interesting by facilitating group activities in real-time and widespread social interactions beyond geographical boundaries.Self-presentation

HCI,Collaborations and game design in multi-user video games

The most collaborative and socially interactive aspect of a video game is the online communities. Popular video games often have various social groups for their diverse community of players. For example, in the quest-based multiplayer game ''Applications of mobile devices

Mobile devices are generally more accessible than their non-mobile counterparts, with about 41% of the world's population as per a survey from 2019 owning a mobile device. This coupled with their relative ease of transport makes mobile devices usable in a large variety of settings which other computing devices would not function as well. Because of this, mobile devices make videoconferencing and texting possible in a variety of settings which would not be accessible without such a device. The Chinese social media platformApplications in social media

Social media tools and platforms have expanded virtual communication amongst various generations. However, with older individuals being less comfortable with CSCW tools, it is difficult to design social platforms that account for both older and younger generational social needs. Often, these social systems focus key functionality and feature creation for younger demographics, causing issues in adaptability for older generations. In addition, with the lack of scalability for these features, the tools are not able to adapt to fit evolutional needs of generations as they age. With the difficulty for older demographics to adopt these intergenerational virtual platforms, the risk of social isolation is increased in them. While systems have been created specifically for older generations to communicate amongst one another, system design frameworks are not complex enough to lend to intergenerational communication.Applications to ubiquitous computing

Along the lines of a more collaborative modality is something called ubiquitous computing. Ubiquitous computing was first coined by Mark Weiser of Xerox PARC. This was to describe the phenomenon of computing technologies becoming prevalent everywhere. A new language was created to observe both the dynamics of computers becoming available at mass scale and its effects on users in collaborative systems. Between the use of social commerce apps, the rise of social media, and the widespread availability of smart devices and the Internet, there is a growing area of research within CSCW that how come out of these three trends. These topics include ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (EMCA) within social media, ubiquitous computing, and instant message based social commerce.Ethnomethodology and synchronicity

In ''You Recommend I Buy: How and Why People Engage in Instant Messaging Based Social Commerce'', researchers on this project analyzed twelve users of Chinese Instant Messenger (IM) social commerce platforms to study how social recommendation engines on IM commerce platforms result in a different user experience. The study was entirely on Chinese platforms, mainly WeChat. The research was conducted by a team composed of members from Stanford, Beijing, Boston, and Kyoto. The interviewing process took place in the winter of 2020 and was an entirely qualitative analysis, using just interviews. The goal of the interviews were to probe about how participants got involved in IM based social commerce, their experience on IM based social commerce, the reasons for and against IM based social commerce, and changes introduced by IM based social commerce to their lives. An IM-based service integrates directly with more intimate social experiences. Essentially, IM is real-time texting over a network. This can be both a synchronous or asynchronous activity. IM based social commerce makes the user shopping experience more accessible. In terms of CSCW, this is an example of ubiquitous computing. This creates a "jump out of the box" experience as described in the research because the IM based platform facilitates a change in user behavior and the overall experience on social commerce. The benefit of this concept is that the app is leveraging personal relationships and real-life networks that can actually lead to a more meaningful customer experience, which is founded upon trust.Embeddedness

A second CSCW paper, ''Embeddedness and Sequentiality in Social Media'', explores a new methodology for analyzing social media—another expression of ubiquitous computing in CSCW. This paper used ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (EMCA) as a framework to research Facebook users. In brief, ethnomethodology studies the everyday interactions of people and relates how this pertains to forming their outlook of the world. Conversational analysis delves into the structures of conversations so as to extract information about how people construct their experiences. The team behind this research, hailing fromFor EMCA, the activities of everyday life are structured in time—some things routinely happen before others. Fundamentally there is a 'sequentiality' to activity, something that has been vital for developing understanding of the orderly nature of talk and bodily interaction.In other words, EMCA pays attention to the sequence of events, so as to reveal some sort of underlying order about our behavior in our day-to-day interactions. In the bigger picture, this work reveals that time, as one of the dimensions to consider within collaborative systems design, matters. Another major factor would be distance. ''Does Distance Still Matter? Revisiting the CSCW Fundamentals on Distributed Collaboration'' is another research article that, as the title suggests, explores under what circumstances distance matters. Most notably, it mentions the "mutual knowledge problem." This problem arises when a group in a distributed collaborative system experiences a breakdown in communication due to the fact that its members lack a shared understanding for the given context they are working in. According to the article, it matters that everyone is in alignment over the nature of what they are doing.

Co-located, parallel and sequential activities

The solutions of unresolved issues in ubiquitous computing systems can be explored now that the observations of user experiences in social media, which are normally based on recollection, are no longer needed. Some of the unresolved questions include: "How does social media start being used, stop being used? When is it being used, and how is that usage ordered and integrated into other, parallel activities at the time?" Parallel activities refer to occurrences in co-located groupware and ubiquitous computing technologies like social media. Examining these sequential and parallel activities in user groups on social media networks enables the ability to " anagethe experience of that everyday life." An important takeaway from this paper on EMCA and sequentiality is that it reveals how the choices made by designers of social media apps ultimately mediates our end-user experience, for better or for worse. It reveals: "when content is posted and sequentially what is associated with it."Ubiquitous computing infrastructures

On the topic of computing infrastructures, ''Democratizing Ubiquitous Computing – a Right for Locality'' presents a study from researchers atA ubiquitous computing infrastructure can play an important role in enabling and enhancing beneficial social processes as, unlike electricity, digital infrastructure enhances a society's cognitive power by its ability to connect people and information 9 While infrastructure projects in the past had the idealistic notion to connect the urban realm and its communities of different ethnicity, wealth, and beliefs, Graham et al. 8note the increasing fragmentation of the management and ownership of infrastructures. This is because ubicomp has the potential to further disadvantage marginalized communities online.The current disadvantage of ubiquitous computing infrastructures is that they do not best support urban development. Proposals to resolve these social issues include increased transparency about personal data collection as well as individual and community accountability about the data collection process in ubicomp infrastructure. ''Data at work: supporting sharing in science and engineering'' is one such paper that goes into greater depth about how to build better infrastructures that enable open data-sharing and thus, empower its users. What this article outlines is that in building better collaborative systems that advance science and society, we are, by effect, "promoting sharing behaviors" that will encourage greater cooperation and more effective outcomes. Essentially, ubiquitous computing will reflect society and the choices it makes will influence those computing systems that are put in place. Ubiquitous computing is huge to the field of CSCW because as the barriers between physical boundaries that separate us break down with the adoption of technology, our relationships to those locations is actually strengthened. However, there remains few potential challenges when it comes to social collaboration and the workplace.

Challenges

Social – technical gap

The success of CSCW systems is often so contingent on the social context that it is difficult to generalize. Consequently, CSCW systems that are based on the design of successful ones may fail to be appropriated in other seemingly similar contexts for a variety of reasons that are nearly impossible to identify ''Leadership

Generally, teams working in a CSCW environment need the same types ofAdoption of groupware

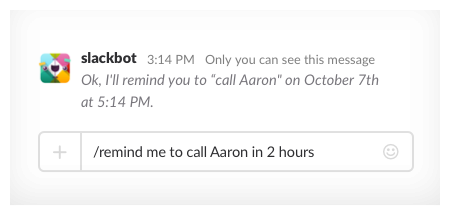

Groupware goes hand in hand with CSCW. The term refers to software that is designed to support activities of a group or organization over a network and includes email, conferencing tools, group calendars, workflow management tools, etc. While groupware enables geographically dispersed teams to achieve organizational goals and engage in cooperative work, there are also many challenges that accompany use of such systems. For instance, groupware often requires users to learn a new system, which users may perceive as creating more work for them without much benefit. If team members are not willing to learn and adopt groupware, it is highly difficult for the organization to develop the requisite critical mass for the groupware to be useful. Further, research has found that groupware requires careful implementation into a group setting, and product developers have not as yet been able to find the most optimal way to introduce such systems into organizational environments. On the technical side, networking issues with groupware often create challenges in using groupware for CSCW. While access to the Internet is becoming increasingly ubiquitous, geographically dispersed users still face challenges of differing network conditions. For instance, web conferencing can be quite challenging if some members have a very slow connection and others are able to utilize high speed connections.Intergenerational groups

Adapting CSCW tools for intergenerational groups is a prevalent issue within all forms of CSCW. Different generations have different feelings towards technology as well as different ways to utilize technology. However, as technology has become integral to everyday tasks, it must be accessible to all generations of people. With cooperative work becoming increasingly important and diversified, virtual interaction between different generations is also expanding. Given this, many fields that utilize CSCW tools require carefully designed frameworks to account for different generations.Workplace teams

One of the recurring challenges in CSCW environments is development of an infrastructure that can bridge cross- generational gaps in virtual teams. Many companies rely on communication and collaboration between intergenerational employees to be successful, and often this collaboration is performed using various software and technologies. These team-driven groupware platforms range from email and daily calendars to version control platforms, task management software, and more. These tools must be accessible to workplace teams virtually, with remote work becoming more commonplace. Ideally, system designs will accommodate all team members, but orienting older workers to new CSCW tools can often be difficult. This can cause problems in virtual teams due to the necessity of incorporating the wealth of knowledge and expertise that older workers bring to the table with the technological challenges of new virtual environments. Orienting and retraining older workers to effectively utilize new technology can often be difficult, as they generally have less experience than younger workers with learning such new technologies. As older workers delay their retirement and re-enter the workforce, teams are becoming increasingly intergenerational, meaning that the creation of effective intergenerational CSCW frameworks for virtual environments is essential.Tools in CSCW

Collaboration amongst peers has always been an integral aspect to getting something done. Working together not only eases the difficulty of the task at hand, but leads to more effective work that is accomplished. As computers and technology become increasingly important in everyday lives, communication skills change as technology allows individuals to stay connected across many previous barriers. Barriers to communication might have been the end of the work day, being across the country or even slow applications that are more of a hindrance than an aid. With new collaborative tools that have been tried and tested, these previous barriers to communication have been shattered and replaced with new tools that help progress collaboration. Tools that have been integral in shaping computer supported cooperative work can be split into two major categories: communication and organization. * Communication: The ability to communicate with others while working is a luxury that has increased the speed and accuracy at which tasks are accomplished. Individuals can also send pictures of code and issues through platforms like

* Communication: The ability to communicate with others while working is a luxury that has increased the speed and accuracy at which tasks are accomplished. Individuals can also send pictures of code and issues through platforms like Departmental conflicts

Cross-boundary breakdowns

Cross-boundary breakdowns are when different departments of the same organization unintentionally harm other. They may be caused by failures to coordinate activities across multiple departments, a form of articulation work.Re-coordinating activities

To restore useful communication between departments after a cross-boundary breakdown, organizations may perform re-coordinating activities. Hospitals may respond to cross-boundary breakdowns by explicitly ranking key resources or assigning "integrator" roles to multiple staff members across different departments.Challenges in research

Differing meanings

In the CSCW field, researchers rely on a variety of sources that include journals and research schools of thought. These different sources may lead to disagreement and confusion, as there are terms in the field that can be used in different contexts ("user", "implementation", etc.) User requirements change over time and are often not clear to participants due to their evolving nature and the fact that requirements are always in flux.Identifying user needs

CSCW researchers often have difficulty deciding which set(s) of tools will benefit a particular group because of the nuances within organizations. This is exacerbated by the fact that it is challenging to accurately identify user/group/organization needs and requirements, since such needs and requirements inevitably change through the introduction of the system itself. When researchers study requirements multiple times, the requirements themselves often change and evolve once the researchers have completed a particular iteration.Evaluation and measurement

The range of disciplinary approaches leveraged in implementing CSCW systems makes CSCW difficult to evaluate, measure, and generalize to multiple populations. Because researchers evaluating CSCW systems often bypass quantitative data in favor of naturalistic inquiry, results can be largely subjective due to the complexity and nuances of organizations themselves. Possibly as a result of the debate between qualitative and quantitative researchers, three evaluation approaches have emerged in the literature examining CSCW systems. However, each approach faces its own unique challenges and weaknesses:Diversity, equity, and inclusion

Gender

In computer-supported cooperative work, there are small psychological differences between how men and women approach CSCW programs. This can lead to unintentionally biased systems, due to the majority of software being designed and tested by men. As well, in systems where societal gender differences are not accounted for and countered, men tend to overrepresent women in these online spaces. This can lead to women feeling potentially alienated and unfairly targeted by CSCW programs. In recent years, more studies have been conducted on how men and women interact with each other using CSCW systems. Findings do not indicate that men and women have performance difference when performing CSCW tasks, but rather that each gender approaches and interacts with software and performs CSCW tasks differently. In most findings, men were more likely to explore potential choices and willing to take risks compared to women. In group tasks, women in general were more conservative in voicing their opinions and suggestions on tasks when paired with a male, but inversely were very communicative when paired with another woman. As well, men are found to be more likely to take control of group activities and teamwork, even from a young age, leading to further ostracizing of women speaking up in CSCW group work. Additionally, in CSCW message boards, men on average posted more messages and engaged more frequently than their female counterparts.Increasing female participation

The dynamic of women in the workforce not participating as much is less of a CSCW problem and is prevalent in all workspaces, but software can still be designed to increase female participation in CSCW. In software design, women are more likely to be involved if software is designed to center communication and cooperation. This is one possible method to increasing female participation, and it does not address why CSCW has lower female participation in the first place. In a study, women generally rated themselves as being poor at understanding technology, having difficulty at using mobile programs, and disliked using CSCW software. However, when asked these same questions about specific software in general, they rated themselves just as strongly as the men in the study did. This lack of confidence in software as a whole impacts women's ability to efficiently and effectively use online programs compared to men, and accounts for some of the difficulties women face in using CSCW software. Despite being an active area of research since the 1990s, many developers often do not take gender differences into account when designing their CSCW systems. These issues compound on top of the cultural problems mentioned previously, and lead to further difficulties for women in CSCW. By enabling developers to be more aware of the differences and difficulties facing women in CSCW design, women can be more effective users of CSCW systems through sharing and voicing opinions.Conferences

Since 2010, theSee also

* Collaborative working environment * Collaborative working system *References

Further reading

;Most cited papers This list, the CSCW Handbook Papers, is the result of a citation graph analysis of the CSCW Conference./ref> It was established in 2006 and reviewed by the CSCW community. This list only contains papers published in one conference; papers published at other venues have also had significant impact on the CSCW community. The "CSCW handbook" papers were chosen as the overall most cited within the CSCW conference ... It led to a list of 47 papers, corresponding to about 11% of all papers. # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #

External links

CSCW Conference

European CSCW Conference Foundation

GROUP Conference

COOP Conference

{{DEFAULTSORT:Computer Supported Cooperative Work Computer-related introductions in 1984 Collaboration Groupware Multimodal interaction Human–computer interaction Instructional design