The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a

political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated

world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the

Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

during

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Comintern was founded in March 1919 at a congress in

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

convened by

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

and the

Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (RCP), which aimed to create a new international body committed to

revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revo ...

and the overthrow of

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

worldwide.

Initially, the Comintern operated with the expectation of imminent

proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialist ...

s in Europe, particularly Germany, which were seen as crucial for the survival and success of the

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

. Its early years were characterized by attempts to foment and coordinate revolutionary uprisings and the establishment of disciplined communist parties across the globe, often demanding strict adherence to the "

Twenty-one Conditions" for admission. As these revolutionary hopes faded by the early 1920s, the Comintern's policies shifted, notably with the adoption of the "

united workers' front" tactic, aiming to win over the working masses from

reformist

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

socialist parties. Throughout the 1920s, the Comintern underwent a process of "

Bolshevisation", increasing the centralization of its structure and the dominance of the RCP within its ranks. This process intensified with the rise of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

The "

Third Period" (1928–1933) saw the Comintern adopt an

ultra-left line, denouncing

social democratic

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

parties as "

social fascism" and advocating "class against class" tactics, which proved disastrous, particularly in the face of rising

Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

in Germany. From 1934, the Comintern shifted to the

Popular Front policy, advocating broad alliances with socialist and even liberal parties against fascism. This was formally adopted at its

Seventh World Congress in 1935. The Comintern played a significant role in organizing support for the Republican side in the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, including the formation of the

International Brigades

The International Brigades () were soldiers recruited and organized by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front (Spain), Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The International Bri ...

. However, this period also coincided with the

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

in the Soviet Union, during which many Comintern officials and foreign communists residing in Moscow were arrested and executed.

With the signing of the

Nazi–Soviet Pact in August 1939, the Comintern again changed its line, denouncing the war between

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and the Western Allies as an "imperialist war" and abandoning its

anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

stance until the

German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. As a gesture to its Western Allies in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Stalin unilaterally dissolved the Comintern on 15 May 1943. While its formal structures were dismantled, mechanisms of Soviet control over the international communist movement persisted and were later partially revived through the

Cominform (1947–1956).

Background

The Comintern, or Third International, was the direct descendant of the

First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist ...

(1864–1872) and the

Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

(1889–1916). The First International, established by

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, aimed to coordinate the

proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

in its worldwide struggle against

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

, based on the premise that "the working men have no country" and that horizontal class allegiance would supersede vertical national divisions. The Second International, created in 1889, was a looser federation of autonomous socialist parties, comprising "left", "right", and "centrist" factions divided on issues such as

bourgeois democracy, the

national question,

general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

s, and, crucially, war.

The Second International foundered in August 1914 on the rock of

national chauvinism when most of its constituent parties chose to support their respective national governments in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

by voting for

war credits.

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, a key figure in the Russian

Bolshevik Party (later the Russian Communist Party, RCP), viewed this as a "sheer betrayal of socialism" and declared the Second International dead, calling for a Third International by the autumn of 1914. During the war, a minority of intransigent revolutionaries coalesced around the Bolsheviks, forming the

Zimmerwald Left. Lenin advocated turning the international war into a revolutionary civil war and was implacably hostile to parliamentary democracy. The

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of 1917 in Russia, led by the Bolsheviks, was seen by Lenin as the first act of a global drama, with European workers expected to follow suit. To achieve this, a new International, purged of

reformist

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

"traitors", was deemed an absolute necessity.

Foundation and early years (1919–1923)

The Communist International was founded at a congress of revolutionaries in

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

from 2–6 March 1919. The impetus for its creation came from the Bolsheviks' belief in the imminence of world

proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialist ...

, spurred by the perceived collapse of capitalism after World War I and

revolutionary upheavals across Europe, particularly the German "

November Revolution". The mission of the Comintern was to build a "world party" of

communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

dedicated to the armed overthrow of capitalist private property and its replacement by a system of collective ownership.

First (Founding) Congress

On 24 January 1919, a "Letter of Invitation to the

First Congress of the Communist International" was relayed by wireless, identifying thirty-nine communist parties and revolutionary groups eligible to attend. The congress convened in the

Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin (fortification), Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Mosco ...

on 2 March 1919. Of the fifty-one delegates, only nine arrived from abroad due to the

Allied blockade of Russia; the rest resided in Soviet Russia, and many lacked authorized credentials.

Hugo Eberlein, the delegate of the

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (, ; KPD ) was a major Far-left politics, far-left political party in the Weimar Republic during the interwar period, German resistance to Nazism, underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and minor party ...

(KPD), was mandated to oppose the immediate formation of a new International, reflecting

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg ( ; ; ; born Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary and Marxist theorist. She was a key figure of the socialist movements in Poland and Germany in the early 20t ...

's earlier concerns about premature Bolshevik dominance. Despite Eberlein's abstention, the congress voted overwhelmingly to establish the Third International on 4 March 1919.

The principal document of the congress was

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

's "Manifesto to the Proletariat of the Entire World", which emphasized

soviets (workers' councils) as the instrument of working-class unity and action, deeming the Russian model universally applicable. It dismissed "bourgeois democracy" and reiterated Lenin's insistence on the

dictatorship of the proletariat. The improvised nature of the congress meant that no formal statutes or rules were adopted, but an

Executive Committee (ECCI) was elected, with

Grigory Zinoviev as its first President. While provision was made for foreign party representation on the ECCI, Bolsheviks predominated due to the prestige of the Russian Revolution and the weakness of foreign parties.

Universalisation of Bolshevism

The foundation of the Comintern institutionalized the split in the international labour movement between revolutionary communists and reformist

social democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

. This schism was rooted in fundamentally different conceptions of the path to socialism.

Karl Kautsky, a leading theoretician of the Second International, condemned the Bolshevik coup in ''

The Dictatorship of the Proletariat'' (1918), arguing that socialism was inseparable from democracy and that a revolution in backward Russia could only result in a terroristic dictatorship. Lenin, in his reply ''

The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky'' (1918), excoriated Kautsky, asserting that parliamentary institutions were a sham concealing bourgeois class rule and that "proletarian democracy is a million times more democratic than any bourgeois democracy". He proclaimed that

Bolshevism could "serve as a model of tactics for all".

The

Second World Congress, held in

Petrograd and Moscow from 19 July to 7 August 1920, is considered the true founding congress of the Comintern. It adopted the famous "

Twenty-one Conditions" for admission, drafted primarily by Zinoviev under Lenin's guidance. These conditions aimed to split the rank-and-file of European socialist parties from their "

opportunist" leaders and enforce Bolshevik organizational principles. Key conditions included: systematic removal of reformists and centrists from all responsible posts; combining legal and illegal activity; complete break with figures like Kautsky and

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

; establishing communist cells in trade unions; adherence to

democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is the organisational principle of most communist parties, in which decisions are made by a process of vigorous and open debate amongst party membership, and are subsequently binding upon all members of the party. The co ...

based on iron discipline and periodic purges; unconditional support for every Soviet republic; and changing party names to "Communist Party". Point sixteen stated that all decisions of Comintern congresses and the ECCI were binding on all parties. The congress also ratified the Statutes of the Comintern, which established the annual world congress as the supreme body and the ECCI as the directing body between congresses. Point 8 of the Statutes stipulated that the work of the ECCI was performed mainly by the party of the country where it was located (Soviet Russia), which had five representatives with full voting rights, while other major parties had only one.

This "universalisation of Bolshevism" was further elaborated in Lenin's pamphlet ''

"Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder'' (April 1920), which argued that "certain fundamental features of our revolution have a significance that is not local... but international". The

Third (June–July 1921) and

Fourth (November–December 1922) Congresses reinforced the centralist Bolshevik model, creating ECCI bodies like the Presidium, Secretariat, Organisational Bureau (Orgburo), and International Control Commission (ICC) that paralleled Russian party structures. The Comintern also began dispatching "agents" and "emissaries" to intervene in the affairs of national parties. Funding for foreign communist parties and the Comintern's clandestine activities, managed by the

International Liaison Department (OMS) from 1921, came from the Soviet state treasury, creating economic dependence.

Despite the trend towards Russian dominance and centralisation, the Comintern in Lenin's era displayed a degree of pluralism and open debate not seen later. Figures like

Paul Levi of the KPD and the Italian

Amadeo Bordiga were not docile, and some national parties resisted or reinterpreted Moscow's directives.

"United workers' front"

By late 1920 and into 1921, with the failure of revolutionary upheavals in Europe (such as the

factory occupations in Italy and the "

March Action" in Germany in 1921), Lenin reluctantly concluded that proletarian revolution was no longer on the immediate agenda. This led to the adoption of the "

united workers' front" policy, formally expounded in ECCI theses on 18 December 1921. The policy aimed to win over the majority of the working class by engaging in joint defensive struggles with socialist rank-and-file against the capitalist offensive. It allowed for temporary alliances with reformist leaders ("united front from above") but primarily focused on unity "from below". The slogan of the Third Congress (1921) was "To the masses!".

The United Front policy was closely intertwined with changes in Soviet domestic and foreign policy, particularly the

New Economic Policy (NEP) and the search for trade relations with capitalist nations. The

Rapallo Treaty of April 1922 between Germany and Soviet Russia epitomized the growing tension between the Comintern's revolutionary goals and Soviet state interests. The United Front tactics faced intense opposition from left-wing elements in many communist parties (e.g., in France and Italy), who found it inconceivable to court the "social chauvinists". A conference of the three Internationals (Second, Comintern, and the

Vienna Union or "Two-and-a-half International") in Berlin in April 1922, aimed at creating common action, failed amidst mutual suspicion. The Comintern's trade union arm, the

Profintern (Red International of Labour Unions), founded in 1921, played a crucial role in applying United Front tactics in the industrial field, though this often led to splits in national trade union movements, as in Czechoslovakia and France.

The "

German October" of 1923, a failed Comintern-inspired uprising in Germany, revealed fundamental limitations in Comintern thinking, including inadequate military preparations and a misjudgment of the German workers' mood. This debacle convinced many Bolsheviks, notably

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, that European revolution was a distant prospect, reinforcing the priority of defending the Soviet state.

Bolshevisation and Stalin's rise (1924–1928)

The period from 1924 to 1928 was characterized by the "

Bolshevisation" of the Comintern and its member sections. This entailed an increasing Russian dominance, the Russification of ideological and organizational structures, and the canonization of

Leninist

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

principles of party unity, discipline, and

democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is the organisational principle of most communist parties, in which decisions are made by a process of vigorous and open debate amongst party membership, and are subsequently binding upon all members of the party. The co ...

, particularly the concentration of power in the hands of the Russian party delegation to the ECCI.

Impact of Soviet inner-party struggles

The failure of the "German October" and

Lenin's death in January 1924 intensified inner-party struggles in the Soviet Union, which profoundly affected the Comintern. The triumvirate of Zinoviev,

Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

, and Stalin moved against Trotsky and his supporters. At an ECCI Presidium session in January 1924, Zinoviev attributed the German failure to the "opportunism" of

Karl Radek

Karl Berngardovich Radek (; 31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a revolutionary and writer active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and a Communist International leader in the Soviet Union after the Russian ...

,

Heinrich Brandler, and

August Thalheimer, implicating Trotsky by association. "

Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

" was branded a "right deviation".

The slogan of "Bolshevisation" was officially proclaimed at the Fifth Comintern Congress (June–July 1924). In practice, it meant creating centralized, disciplined Leninist organizations fiercely loyal to the RCP majority in its struggle against the "Trotskyite opposition". Zinoviev declared the need for "iron discipline" and the eradication of "social-democratism, federalism, 'autonomy'". This led to a series of denunciations and expulsions: Brandler and Thalheimer were removed from the KPD leadership, replaced by leftists

Arkadi Maslow and

Ruth Fischer;

Boris Souvarine was expelled from the French party; and Polish leaders like

Adolf Warski were condemned.

The Fifth Congress also marked a tactical shift to the left regarding the United Front. The ''Theses on Tactics'' rejected united fronts "solely from above" and re-emphasized the united front "from below" under communist party leadership as a means to unmask reformist "bosses". Radek was removed from the ECCI, and Trotsky was demoted to non-voting status, replaced by Stalin.

However, the period 1925–1926 saw a tentative move back to the centre under

Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

's growing influence in the Comintern, emphasizing a broader conception of the United Front. This coincided with Stalin's doctrine of "

socialism in one country", first propounded in December 1924. This theory argued that the Soviet Union could build socialism without the need for immediate world revolution, and that the main task of communist parties was to defend the USSR. This implied a subordination of the Comintern's revolutionary mission to Soviet state interests and its foreign policy of "

peaceful coexistence". A key initiative of this period was the

Anglo-Russian Trade Union Committee, formed in April 1925.

By 1926, Zinoviev and Trotsky formed the

United Opposition against the Stalin-Bukharin

duumvirate, criticizing "socialism in one country" and the Comintern's rightward turn. The ensuing power struggle dominated the Comintern, leading to Zinoviev's removal as Comintern President in October 1926 (replaced by a "collective leadership" headed by Bukharin) and Trotsky's expulsion from the ECCI and eventually the Soviet Union.

National party responses

Foreign communist parties responded to Bolshevisation in various ways. Many leaders and members, out of sincere respect for the Bolsheviks' revolutionary success or a sense of disorientation, accepted Moscow's directives, sometimes lapsing into deference. Loyalty to the USSR as the first "socialist bastion" and a commitment to "internationalism" as defined by Moscow were powerful motivating factors. Figures like

Palmiro Togliatti of the Italian party ultimately aligned with the RCP majority, recognizing the operational necessity of Moscow's support.

Bureaucratisation within the Comintern and national parties also facilitated Russian control. As world congresses became less frequent, power devolved to the ECCI and its Presidium, which were disproportionately staffed by Bolsheviks and managed the day-to-day workings of the International. However, there was also resistance. "

Ultra-left" elements in parties like the KPD challenged the Russification of the Comintern and the perceived subordination of revolutionary goals to Soviet state interests. There was also widespread reluctance to implement specific organizational prescriptions of Bolshevisation, such as the replacement of territorial branches with factory cells and the formation of communist fractions in reformist trade unions. These measures often clashed with local traditions and practical difficulties, leading to slow implementation or outright disregard.

Third Period (1928–1933)

The years 1928–1933 in Comintern history are known as the "

Third Period", a phase of "ultra-leftist" tactics that proved disastrous. This period was characterized by the belief that capitalism was entering its final crisis, leading to a new revolutionary upsurge and impending imperialist wars.

Defeat of the "right deviation"

The concept of a "Third Period" was first introduced by Bukharin at the Seventh ECCI Plenum (November–December 1926). He posited it as a phase following the initial post-war revolutionary upheaval (First Period) and the relative capitalist stabilization (Second Period), where the internal contradictions of stabilization would lead to a new revolutionary wave. This analysis remained Comintern orthodoxy through the

Sixth World Congress (July–September 1928).

However, by 1928, the political landscape within the Soviet Union was shifting. Stalin began to move against Bukharin and his allies (the "

Right Opposition"), who resisted his policies of

rapid industrialization and

forced collectivization. This struggle inevitably extended to the Comintern. The Sixth Congress, while formally still under Bukharin's influence, saw the

Stalinist faction begin to construct a "right-wing deviation" within the Comintern, linking it to social democracy. Stalin's pivotal speech at an ECCI Presidium meeting in December 1928 concerning the KPD (the "German question") signalled a decisive move against any "Right faction" in the Comintern, demanding "iron inner-party discipline" and condemning "conciliators". This led to purges of "rightists" and "conciliators" in various parties, such as in Germany, Sweden, and Czechoslovakia. Bukharin himself was removed from his Comintern duties in July 1929. Leading Comintern officials like

Dmitri Manuilsky,

Osip Piatnitsky,

Otto Kuusinen, and

Klement Gottwald

Klement Gottwald (; 23 November 1896 – 14 March 1953) was a Czech communist politician, who was the leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1929 until his death in 1953 – titled as general secretary until 1945 and as chairman f ...

aligned with Stalin.

Theory and practice of "social fascism"

The central ideological tenet of the Third Period was the doctrine of "

social fascism". This theory, formally expounded at the Tenth ECCI Plenum (July 1929), asserted that social democracy had transformed from a right-wing working-class party into a wing of the

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

, and in the context of capitalism's final crisis, had become the "moderate wing of

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

". "Left" social democrats (like the

Austro-Marxists or the British

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party (UK), Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse work ...

) were branded as the most dangerous enemies, as they allegedly deceived the workers with revolutionary phrases while supporting capitalism.

This doctrine precluded any united front with social democratic leaders and mandated a strategy of "class against class", meaning communists should fight independently for the leadership of the working class. In practice, this led to intense hostility towards social democratic parties and trade unions. The Comintern urged the creation of independent "Red" trade unions or revolutionary oppositions within existing unions, aiming to organize the unorganized and unemployed, who were seen as a key revolutionary force. This policy proved largely counterproductive, isolating communists from the bulk of the organized working class and leading to a decline in membership and influence in many countries, such as Britain and Czechoslovakia.

In Germany, the "social fascism" line had particularly tragic consequences. The KPD, under

Ernst Thälmann, directed its main fire against the

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany ( , SPD ) is a social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany. Saskia Esken has been the party's leader since the 2019 leadership election together w ...

(SPD), even engaging in joint actions with the

Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

against SPD-led governments (e.g., the

Prussian referendum of 1931). This division in the German labour movement fatally weakened its ability to resist the rise of

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. While some local-level collaboration between communists and social democrats occurred, the official Comintern line remained largely unchanged even after Hitler's accession to power in January 1933. Soviet foreign policy concerns, particularly the desire to maintain stable relations with Germany and prevent its alignment with Western powers against the USSR, also played a role in shaping the Comintern's approach, leading to a downplaying of the Nazi threat at times.

Popular Front and Great Purge (1934–1939)

The disastrous consequences of the Third Period, epitomized by the Nazi seizure of power in Germany, led to a gradual and complex reorientation of Comintern policy towards the

Popular Front. This era was simultaneously marked by the devastating impact of the Stalinist

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

on the Comintern itself.

Origins of the Popular Front

The catalyst for the shift away from "social fascism" came largely from events in France. In February 1934, joint actions by socialist and communist workers against

a common fascist threat created a powerful groundswell for unity from below. This coincided with a growing recognition within parts of the Comintern leadership, notably

Georgi Dimitrov (who became General Secretary in spring 1934 after his

Leipzig trial), that the old tactics had failed. Dimitrov, with Stalin's cautious and vacillating support, began to advocate for broader

anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

alliances, including with social democratic parties ("united front from above") and even middle-class "democratic" forces.

The process was driven by a "triple interaction": national factors (such as the anti-fascist unity in France), internal Comintern dynamics (Dimitrov's initiatives and debates between "innovators" and "fundamentalists" like Piatnitsky and

Béla Kun), and Soviet foreign policy (the USSR's search for collective security against Nazi Germany, leading to its entry into the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

in 1934 and the

Franco-Soviet Pact in May 1935). By mid-May 1934, Dimitrov was pushing for a change in line, and in July 1934, the

French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (, , PCF) is a Communism, communist list of political parties in France, party in France. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its Member of the European Parliament, MEPs sit with The Left in the ...

(PCF) signed a "Pact of Unity of Action" with the French

Socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

. The PCF, under

Maurice Thorez, then pioneered the call for a broader ''Rassemblement Populaire'' in October 1934, extending appeals to the

Radical Party.

Popular Front in practice

The

Seventh World Congress of the Comintern (July–August 1935) formally ratified the Popular Front policy. Dimitrov's main report defined fascism as "the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinistic and most imperialist elements of finance capital" and called for a "broad people's anti-fascist front" based on the proletarian united front but extending to the peasantry and urban

petty-bourgeoisie. Communists were to defend bourgeois democratic liberties against fascism and present themselves as tribunes of national independence. The Congress resolution allowed for communist participation in Popular Front governments under certain pre-revolutionary conditions, viewing them as potential "transitional forms" to proletarian revolution.

However, the break with the past was partial. The universal applicability of the Bolshevik model was not challenged, and conditions for "organic unity" with socialists remained prohibitively strict. The Popular Front era was marked by an unresolved tension between inherited ideologies and new initiatives. While parties were given more leeway for local adaptation, Moscow's ultimate control remained, especially concerning foreign policy.

In France, the

Popular Front led to an

electoral victory in May 1936 and the formation of a government under

Léon Blum, which the PCF supported from outside. This period saw massive growth in PCF membership and trade union influence, but was also characterized by a wave of strikes that alarmed the Radicals and complicated Soviet foreign policy aims of alliance with France. In Spain, the

Popular Front's narrow

election victory in February 1936 was followed by

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

's

military coup in July, leading to the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

(1936–1939). The USSR and the Comintern provided significant military aid to the

Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

, including the organization of the

International Brigades

The International Brigades () were soldiers recruited and organized by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front (Spain), Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The International Bri ...

. However, Soviet intervention was also aimed at limiting the social revolution and was accompanied by Stalinist purges of Trotskyists (e.g., the

POUM) and anarchists, which fatally divided the Republican camp.

Comintern and the Great Purge

The Popular Front era coincided with the

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

in the USSR (1936–1938), which had a devastating impact on the Comintern. Foreign communists and political émigrés in Moscow were heavily targeted. The repression was driven by Stalin's paranoia, xenophobia, and desire to eliminate all potential opposition, real or imagined. Leading Comintern figures like Piatnitsky, Kun, and

Vilhelm Knorin were arrested and shot. Entire national sections, most notably the

Communist Party of Poland (KPP), were accused of infiltration by enemy agents and dissolved (the KPP in 1938). Thousands of foreign communists perished in the

Gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

or were executed. Comintern officials like Dimitrov and Manuilsky were complicit in the purges, though Dimitrov also attempted to save some individuals. The Purge effectively paralyzed the Comintern apparatus and shattered any remaining illusions about its independence.

Comintern in East Asia (1919–1939)

The Comintern's influence in

East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

was shaped by the context of colonialism, anti-colonial nationalist movements, and the predominance of rural economies. While initial interest focused on Japan, the only industrialized nation in the region, it was in China that the Comintern had its greatest impact.

"Colonial question" and early approaches

The First Comintern Congress (1919) devoted little attention to the "colonial question". However, by the Second Congress (1920), as European revolution failed to materialize, the Bolsheviks began to see anti-imperialist struggles in the East as a way to stabilize the Soviet regime. Lenin's theses on the national and colonial questions, debated with the

Indian communist M. N. Roy, allowed for temporary alliances between communists and "bourgeois-democratic" nationalist forces in colonial regions, provided the proletarian movement maintained its independence. The Baku

Congress of the Peoples of the East (September 1920) and the Congress of Toilers of the Far East (January 1922) further formalized this commitment, though they also highlighted the complexities of applying Bolshevik models in agrarian societies lacking a strong industrial proletariat.

In Japan, the Communist International assisted in the

socialist movement, eventually forming the

Enlightened People's Communist Party, which evolved into the

Japanese Communist Party in 1922. In Korea, the Communist International and the Far Eastern Bureau of the CPSU assisted in the

communist movement in Korea.

China and the First United Front

In China, the Comintern engaged with both the nationalist

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

(KMT) and the fledgling

Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

(CCP), founded in 1921. Under Comintern guidance, the KMT was reorganized along Soviet lines. In August 1922, the ECCI directed the CCP to enter the KMT as individuals, forming a "bloc within" – the

First United Front. This policy, aimed at achieving national independence and unification under KMT leadership, was contested by CCP leaders like

Chen Duxiu

Chen Duxiu ( zh, t=陳獨秀, p=Chén Dúxiù, w=Ch'en Tu-hsiu; 9 October 1879 – 27 May 1942) was a Chinese revolutionary, writer, educator, and political philosopher who co-founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921, serving as its fi ...

but ultimately enforced by Moscow. Comintern advisers like

Mikhail Borodin played a significant role in both parties.

The United Front initially benefited the CCP, which grew rapidly, particularly after the

May Thirtieth Movement

The May Thirtieth Movement () was a major labor and anti-imperialist movement during the middle-period of the Republic of China era. It began when the Shanghai Municipal Police opened fire on Chinese protesters in Shanghai's International Set ...

of 1925. However, tensions mounted. After

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by Names of Sun Yat-sen, several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and political philosopher who founded the Republ ...

's death in March 1925,

Chiang Kai-shek consolidated power within the KMT. In March 1926, Chiang moved against the communists within the KMT, but the Comintern, under Stalin's direction, ignored this and continued to support the alliance and Chiang's

Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT) against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The purpose of the campaign was to reunify China prop ...

. In April 1927, Chiang launched a brutal

massacre of communists in Shanghai, effectively ending the First United Front. The Comintern, seeking to preserve Stalin's infallibility, blamed CCP "rightists" and "leftists" for the disaster. Chen Duxiu was removed as General Secretary.

"28 Bolsheviks" and rural soviets

The Sixth CCP Congress, held in Moscow in 1928 under Comintern supervision, confirmed Stalin's doctrinal "correctness" and initiated a deeper Bolshevisation of the CCP. This period saw the rise of Moscow-trained Chinese cadres, the "

28 Bolsheviks" like

Wang Ming, who ensured CCP subordination to Comintern directives. The Comintern line emphasized urban proletarian leadership, despite the CCP's growing rural base under figures like

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

.

Li Lisan's attempts to implement Comintern directives to seize major urban centers in 1930 ended in failure, for which he was made a scapegoat.

Wang Ming became CCP General Secretary in 1931, marking the zenith of direct Comintern intervention. However, the CCP leadership, particularly those in the

Jiangxi Soviet

The Jiangxi Soviet, sometimes referred to as the Jiangxi-Fujian Soviet, was a soviet area that existed between 1931 and 1934, governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It was the largest component of the Chinese Soviet Republic and hom ...

like Mao, maintained a degree of autonomy, partly due to irregular communications with Moscow and Shanghai. The

Long March

The Long March ( zh, s=长征, p=Chángzhēng, l=Long Expedition) was a military retreat by the Chinese Red Army and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from advancing Kuomintang forces during the Chinese Civil War, occurring between October 1934 and ...

(1934–1935), forced by KMT encirclement campaigns, saw Mao rise to pre-eminence at the

Zunyi Conference (January 1935), challenging the Moscow-backed leadership. The Comintern's adoption of the Popular Front policy at its Seventh Congress (1935) and the growing threat of Japanese expansion led to the formation of a

Second United Front

The Second United Front ( zh, t=第二次國共合作 , s=第二次国共合作 , first=t , l=Second Nationalist-Communist Cooperation, p=dì èr cì guógòng hézuò ) was the alliance between the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Co ...

between the CCP and KMT in 1937, following the

Xi'an Incident. By this time, however, direct Comintern influence over CCP policy had significantly diminished.

World War II and dissolution (1939–1943)

The period from August 1939 to June 1943 is widely regarded as marking the apogee of the Comintern's subordination to Stalin's foreign policy.

Nazi–Soviet Pact and "imperialist war"

The signing of the

Nazi–Soviet Pact in August 1939 led to a dramatic "about turn" in Comintern policy. On 7 September 1939, following a personal interview with Stalin, Dimitrov received instructions to characterize the unfolding war as an "imperialist" conflict between two groups of capitalist states, for which the bourgeoisie of all belligerent states bore equal responsibility. The division between "fascist" and "democratic" capitalist countries was declared to have lost its former sense, and the Popular Front slogan was to be renounced. ECCI Secretariat theses issued on 9 September directed communist parties in belligerent states to actively oppose the "unjust war" and expose its imperialist nature. This marked a fundamental revision of the anti-fascist strategy pursued since 1934.

The new line caused confusion and dissent in many communist parties. The

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

(CPGB), for instance, initially supported the war against Nazi Germany but was forced to reverse its position after intervention from Moscow, leading to the replacement of

Harry Pollitt as General Secretary by

R. Palme Dutt. The PCF was outlawed, and its leaders fled into exile or were arrested. Throughout 1940 and early 1941, the Comintern maintained the "imperialist war" characterization, though the rapid

collapse of France in summer 1940 prompted some tentative rethinking regarding communist participation in anti-Nazi resistance in occupied territories.

"Great Patriotic War" and dissolution

The

German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 (Operation Barbarossa) led to another abrupt ''volte-face''. The war was now redefined as a "

Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

" for the defense of the USSR and an anti-fascist struggle. Communist parties were instructed to give unstinting support to the Allied governments and build broad national fronts and resistance movements.

The Comintern was officially dissolved on 15 May 1943, with the ECCI Presidium recommending its disbandment. The stated reasons were that the centralized international organizational form had become a drag on the further strengthening of national working-class parties and that the diverse conditions in different countries required greater independence and maneuverability. Stalin, in a rare interview, added that the dissolution would expose the "lie of the Hitlerites" that Moscow intended to intervene in other nations and "Bolshevise" them, and would facilitate the work of patriots in uniting freedom-loving peoples against Hitlerism.

The dissolution is widely seen as a gesture by Stalin to appease his Western Allies (Britain and the United States), particularly to facilitate the opening of a

second front in Europe. It also reflected the reality that the Comintern had largely ceased to function effectively as a centralized directing body during the war due to disrupted communications. Some scholars argue that the "real dissolution" of the centralized apparatus had already occurred at the start of the war. After 1943, an organizational framework continued in Moscow under Dimitrov, attached to the

CPSU Central Committee as the

International Department, and through "special institutes" (numbered 99, 100, and 205) that carried on tasks like training cadres, maintaining radio links, and gathering intelligence. This ensured continued Soviet influence over the international communist movement, which would re-emerge more formally with the creation of the

Cominform in 1947.

Organization

The Comintern's organizational structure was designed to be a centralized "world party". Its supreme body was the World Congress, which was supposed to meet annually (later less frequently) to decide on program and policy. Between congresses, the Comintern was directed by its

Executive Committee (ECCI). The ECCI, in turn, elected a Presidium to handle day-to-day affairs, and a Secretariat. Other important bodies included the Organisational Bureau (Orgburo) and the International Control Commission (ICC), which was responsible for discipline and ideological purity. The

International Liaison Department (, OMS), established in 1921, managed the Comintern's clandestine activities, including funding, communications, and forging documents.

The ECCI and its subsidiary bodies were based in Moscow. The statutes stipulated that the Communist Party of the host country (the Soviet Union) would have a disproportionate influence, holding five seats on the ECCI, while other major parties held one. National communist parties were considered "sections" of the Comintern, bound by its decisions.

World Congresses and Plenums

The Comintern held seven World Congresses:

The ECCI also convened thirteen Enlarged Plenums between 1922 and 1933, which served as important decision-making forums between congresses:

# First Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 24 February–4 March 1922

# Second Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 7–11 June 1922

# Third Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 12–23 June 1923

# Fourth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 12–13 July 1924

# Fifth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 21 March–6 April 1925

# Sixth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 17 February–15 March 1926

# Seventh Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 22 November–16 December 1926

# Eighth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 18–30 May 1927

# Ninth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 9–25 February 1928

# Tenth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 3–19 July 1929

# Eleventh Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 26 March–11 April 1931

# Twelfth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 27 August–15 September 1932

# Thirteenth Enlarged Plenum: Moscow, 28 November–12 December 1933

Comintern-sponsored organizations

Several international organizations (

communist fronts) were sponsored by the Comintern:

*

Young Communist International (1919–1943)

*

Red International of Labour Unions

The Red International of Labor Unions (, RILU), commonly known as the Profintern (), was an international body established by the Communist International (Comintern) with the aim of coordinating communist activities within trade unions. Formally ...

(Profintern, formed in 1920)

*

Communist Women's International (formed in 1920)

*

International Red Aid (MOPR, formed in 1922)

*

Red Peasant International (Krestintern, formed in 1923)

*

Red Sport International (Sportintern)

* International of the Proletarian Freethinkers (1925–1933)

*

League against Imperialism (formed in 1927)

*

Workers International Relief

Bureaus

*

Amsterdam Bureau of the Communist International

*

Far Eastern Bureau of the Communist International

* Scandinavian Bureau of the Communist International

* Southern Bureau of the Communist International

* Balkan Bureau of the Communist International

* Vienna Bureau of the Communist International

Historiography

The

historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

of the Comintern is diverse and has evolved significantly, particularly with the opening of Soviet archives in the late 1980s. Early Western scholarship during the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

often depicted the Comintern as a monolithic tool of Soviet foreign policy, emphasizing its subordination to Moscow. "Dissident communist" critiques, such as those by former members like

Franz Borkenau or

Trotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

writers, often focused on the Comintern's degeneration under Stalin compared to an idealized Leninist phase. Official communist historiography, particularly during the Soviet era, presented a sanitized and ideologically controlled narrative.

More recent "scientific" scholarly studies, including those by

E. H. Carr and

Fernando Claudin, have offered more nuanced interpretations. Carr, while not completing a single-volume history, extensively analyzed the Comintern's relationship with Soviet foreign policy, allowing for a degree of autonomous action by Comintern leaders and national parties. Claudin, in his Marxist analysis, argued that the Comintern failed to differentiate between Russian and Western European conditions, leading to flawed strategies.

The opening of the Comintern archives in Moscow has spurred new research, often confirming the extent of Soviet control, particularly under Stalin, but also revealing complexities in the relationship between the center and national sections, and internal debates within the Comintern apparatus. There is ongoing debate about the degree of autonomy retained by national parties and the interplay between Moscow's directives and indigenous factors in shaping communist policies.

Legacy

The legacy of the Comintern is overwhelmingly viewed as one of failure in achieving its original aims of worldwide socialist revolution and the liberation of colonial peoples. Instead of being a pluralistic body of enthusiastic revolutionaries, it was gradually transformed into a bureaucratized instrument of the Soviet state, particularly under Stalin. The concept of

proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory th ...

became identified with devotion to the USSR and the duty to protect the "first socialist motherland".

The Comintern's insistence on "iron discipline", intolerance of political rivals, and the ossification of Marxist thought under Stalinism hindered the development of strategies more applicable to diverse national conditions. The processes of Bolshevisation and later Stalinisation led to the demotion, expulsion, and purging of those who resisted Moscow's line. The Comintern legitimized the absurdities of "social fascism", justified the Great Purge and the mass repression of loyal communists, and supported the Nazi–Soviet Pact.

However, the Comintern's legacy is also seen as ambiguous. In the 1920s, it nurtured a range of theoretical responses to contemporary problems, with figures like Trotsky, Bukharin, and

Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Francesco Gramsci ( , ; ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian Marxist philosophy, Marxist philosopher, Linguistics, linguist, journalist, writer, and politician. He wrote on philosophy, Political philosophy, political the ...

offering diverse solutions. During the Popular Front era and World War II, communists were among the most active anti-fascists. The threat of communism may also have spurred capitalist governments to undertake social reforms. After World War II, communism expanded significantly, partly due to the Soviet war effort and the groundwork laid by the Comintern in consolidating disciplined communist parties.

Ultimately, the universalisation of a Bolshevik model specific to Russian conditions, later subjected to Stalinist hyper-centralisation, is seen as a core reason for the Comintern's failures and the eventual demise of the communist ideal. The Leninist party structure and its associated dogmas proved to be an enduring constraint on communist parties adapting to changing post-war realities.

See also

*

List of left-wing internationals

This is a list of Socialism, socialist, Communism, communist, and Anarchism, anarchist, and other Left-wing politics, left-wing internationals. An "International" — such as, the "International Workingmen's Association, First International", the " ...

*

:Comintern sections

*

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

*

Communist University of the National Minorities of the West

*

Communist University of the Toilers of the East

*

Communist Workers' International

*

International Communist Opposition

*

International Entente Against the Third International

*

International Lenin School

*

International Revolutionary Marxist Centre

*

Moscow Sun Yat-sen University

*

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) was a political international established in France in 1938 by Leon Trotsky and his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union and the Communist International (also known as Comintern or the Third Inte ...

(est. 1938)

*

Socialist International

The Socialist International (SI) is a political international or worldwide organisation of political parties which seek to establish democratic socialism, consisting mostly of Social democracy, social democratic political parties and Labour mov ...

(est. 1951)

References

Works cited

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

* Barrett, James R. "What Went Wrong? The Communist Party, the US, and the Comintern." ''American Communist History'' 17.2 (2018): 176–184.

* Belogurova, Anna. "Networks, Parties, and the" Oppressed Nations": The Comintern and Chinese Communists Overseas, 1926–1935." ''Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review'' 6.2 (2017): 558–582

online* Belogurova, Anna. ''The Nanyang Revolution: The Comintern and Chinese Networks in Southeast Asia, 1890–1957'' (Cambridge UP, 2019). focus on Malaya

* Caballero, Manuel. ''Latin America and the Comintern, 1919–1943'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

* Carr, E. H. '' Twilight of the Comintern, 1930–1935''. New York: Pantheon Books, 1982

online free to borrow* Chase, William J. ''Enemies within the Gates? The Comintern and the Stalinist Repression, 1934–1939.'' (Yale UP, 2001).

* Dobronravin, Nikolay. "The Comintern, 'Negro Self-Determination' and Black Revolutions in the Caribbean." ''Interfaces Brasil/Canadá'' 20 (2020): 1–18

online* Drachkovitch, M. M. ed. ''The Revolutionary Internationals'' (Stanford UP, 1966).

* Drachewych, Oleksa. "The Comintern and the Communist Parties of South Africa, Canada, and Australia on Questions of Imperialism, Nationality and Race, 1919–1943" (PhD dissertation, McMaster University, 2017

online

* Dullin, Sabine, and Brigitte Studer. "Communism+ transnational: the rediscovered equation of internationalism in the Comintern years." ''Twentieth Century Communism'' 14.14 (2018): 66–95.

* Gankin, Olga Hess and Harold Henry Fisher. ''The Bolsheviks and the World War: The Origin of the Third International''. (Stanford UP, 1940

online

* Gupta, Sobhanlal Datta. ''Comintern and the Destiny of Communism in India: 1919–1943'' (2006

online* Haithcox, John Patrick. ''Communism and nationalism in India: MN Roy and Comintern policy, 1920–1939'' (1971)

online* Hallas, Duncan. ''The Comintern: The History of the Third International''. (London: Bookmarks, 1985).

*

Hopkirk, Peter. ''Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin's Dream of a Empire in Asia 1984'' (1984).

* Ikeda, Yoshiro. "Time and the Comintern: Rethinking the Cultural Impact of the Russian Revolution on Japanese Intellectuals." in ''Culture and Legacy of the Russian Revolution: Rhetoric and Performance–Religious Semantics–Impact on Asia'' (2020): 227+.

*

James, C. L. R., ''

World Revolution 1917–1936: The Rise and Fall of the Communist International.'' (1937)

online* Jeifets, Víctor, and Lazar Jeifets. "The Encounter between the Cuban Left and the Russian Revolution: The Communist Party and the Comintern." ''Historia Crítica'' 64 (2017): 81–100.

* Kennan, George F. ''Russia and the West Under Lenin and Stalin'' (1961) pp. 151–93

online* Lazitch, Branko and Milorad M. Drachkovitch. ''Biographical dictionary of the Comintern'' (2nd ed. 1986).

* McDermott, Kevin. "Stalin and the Comintern during the 'Third Period', 1928–33." ''European history quarterly'' 25.3 (1995): 409–429.

* McDermott, Kevin. "The History of the Comintern in Light of New Documents", in Tim Rees and Andrew Thorpe (eds.), ''International Communism and the Communist International, 1919–43''. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1998.

* McDermott, Kevin, and J. Agnew. ''The Comintern: a History of International Communism from Lenin to Stalin''. (Basingstoke, 1996).

* Melograni, Piero. ''Lenin and the Myth of World Revolution: Ideology and Reasons of State 1917–1920'', (Humanities Press, 1990).

* Priestland, David. ''The Red Flag: A History of Communism.'' (2010).

* Riddell, John. "The Comintern in 1922: The Periphery Pushes Back." ''Historical Materialism'' 22.3–4 (2014): 52–103.

online* Smith, S. A. (ed.) ''The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism'' (2014), ch 10:

The Comintern.

* Studer, Brigitte. ''Travellers of the World Revolution: A Global History of the Communist International'' (Verso, 2023

online scholarly review of this book* Taber, Mike (ed.), ''The Communist Movement at a Crossroads: Plenums of the Communist International's Executive Committee, 1922–1923''. John Riddell, trans. (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019).

* Ulam, Adam B. ''Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–1973''. (2nd ed. Praeger Publishers, 1974)

online* Valeva, Yelena. ''The CPSU, the Comintern, and the Bulgarians'' (Routledge, 2018).

* Worley, Matthew et al. (eds.) ''Bolshevism, Stalinism and the Comintern: Perspectives on Stalinization, 1917–53''. (2008).

* ''The Comintern and its Critics'' (Special issue of ''Revolutionary History'' Volume 8, no 1, Summer 2001).

Historiography

* Drachewych, Oleksa. "The Communist Transnational? Transnational studies and the history of the Comintern." ''History Compass'' 17.2 (2019): e12521.

* McDermott, Kevin. "Rethinking the Comintern: Soviet Historiography, 1987–1991", ''Labour History Review'', 57#3 (1992), pp. 37–58.

* McIlroy, John, and Alan Campbell. "Bolshevism, Stalinism and the Comintern: A historical controversy revisited." ''Labor History'' 60.3 (2019): 165–192

online

* Redfern, Neil. "The Comintern and Imperialism: A Balance Sheet." ''Journal of Labor and Society'' 20.1 (2017): 43–60.

Primary sources

* Banac, I. ed. ''The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov 1933–1949'', Yale University Press, 2003.

* Davidson, Apollon, ''et al.'' (eds.) ''South Africa and the Communist International: A Documentary History''. 2 volumes, 2003.

* Degras, Jane T. ''The Communist International, 1919–43'' 3 volumes. 1956; documents

online vol 1 1919–22vol 2 1923–28

vol 3 1929–43

* Firsov, Fridrikh I., Harvey Klehr, and John Earl Haynes, eds. ''Secret Cables of the Comintern, 1933–1943''. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2014

online review

* Gruber, Helmut. ''International Communism in the Era of Lenin: A Documentary History'', Cornell University Press, 1967.

* Kheng, Cheah Boon, ed. ''From PKI to the Comintern, 1924–1941'', Cornell University Press, 2018.

* Riddell, John (ed.):

** ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time, Vol. 1: Lenin's Struggle for a Revolutionary International: Documents: 1907–1916: The Preparatory Years''. New York: Monad Press, 1984.

** ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time, Vol. 2: The German Revolution and the Debate on Soviet Power: Documents: 1918–1919: Preparing the Founding Congress''. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1986.

** ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time, Vol. 3: Founding the Communist International: Proceedings and Documents of the First Congress: March 1919''. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1987.

** ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time: Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples Unite! Proceedings and Documents of the Second Congress, 1920''. In Two Volumes. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991.

** ''The Communist International in Lenin's Time: To See the Dawn: Baku, 1920: First Congress of the Peoples of the East''. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1993.

** ''Toward the United Front: Proceedings of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, 1922''. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

External links

Marxists Internet Archive

* Lenin's speech: The Third, Communist International ()

Site Comintern Archives

*

Site Comintern Archives

*

Program of the Communist International. Together With Its Constitution

' (adopted at 6th World Congress in 1928)

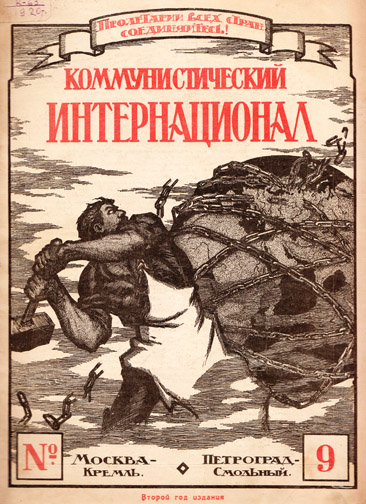

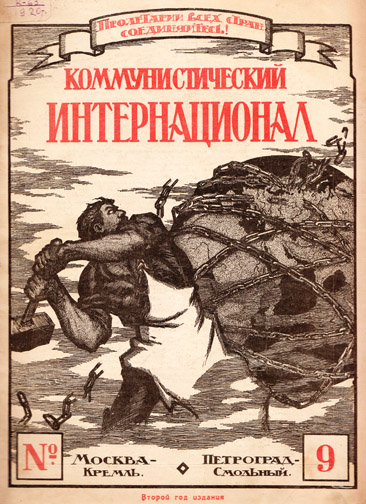

Journal of the Comintern, Marxists Internet Archive

''Outline History of the Communist International''

''The Internationale''

by R. Palme Dutt, 1964

Report from Moscow, 3rd International congress, 1920

by Otto Rühle

Article on the Third International from the Encyclopædia Britannica

{{Authority control

Comintern

Communist organizations

History of socialism

Left-wing internationals

Far-left politics

Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

Stalinist organizations

Stalinism

Former international organizations

International non-profit organizations

Politics of the Soviet Union

1919 establishments in Russia

1943 disestablishments in the Soviet Union

Organizations established in 1919

Organizations disestablished in 1943

International socialist organizations

The Second World Congress, held in Petrograd and Moscow from 19 July to 7 August 1920, is considered the true founding congress of the Comintern. It adopted the famous " Twenty-one Conditions" for admission, drafted primarily by Zinoviev under Lenin's guidance. These conditions aimed to split the rank-and-file of European socialist parties from their " opportunist" leaders and enforce Bolshevik organizational principles. Key conditions included: systematic removal of reformists and centrists from all responsible posts; combining legal and illegal activity; complete break with figures like Kautsky and

The Second World Congress, held in Petrograd and Moscow from 19 July to 7 August 1920, is considered the true founding congress of the Comintern. It adopted the famous " Twenty-one Conditions" for admission, drafted primarily by Zinoviev under Lenin's guidance. These conditions aimed to split the rank-and-file of European socialist parties from their " opportunist" leaders and enforce Bolshevik organizational principles. Key conditions included: systematic removal of reformists and centrists from all responsible posts; combining legal and illegal activity; complete break with figures like Kautsky and  The failure of the "German October" and Lenin's death in January 1924 intensified inner-party struggles in the Soviet Union, which profoundly affected the Comintern. The triumvirate of Zinoviev,

The failure of the "German October" and Lenin's death in January 1924 intensified inner-party struggles in the Soviet Union, which profoundly affected the Comintern. The triumvirate of Zinoviev,  However, the period 1925–1926 saw a tentative move back to the centre under

However, the period 1925–1926 saw a tentative move back to the centre under  The central ideological tenet of the Third Period was the doctrine of " social fascism". This theory, formally expounded at the Tenth ECCI Plenum (July 1929), asserted that social democracy had transformed from a right-wing working-class party into a wing of the

The central ideological tenet of the Third Period was the doctrine of " social fascism". This theory, formally expounded at the Tenth ECCI Plenum (July 1929), asserted that social democracy had transformed from a right-wing working-class party into a wing of the  In France, the Popular Front led to an electoral victory in May 1936 and the formation of a government under Léon Blum, which the PCF supported from outside. This period saw massive growth in PCF membership and trade union influence, but was also characterized by a wave of strikes that alarmed the Radicals and complicated Soviet foreign policy aims of alliance with France. In Spain, the Popular Front's narrow election victory in February 1936 was followed by

In France, the Popular Front led to an electoral victory in May 1936 and the formation of a government under Léon Blum, which the PCF supported from outside. This period saw massive growth in PCF membership and trade union influence, but was also characterized by a wave of strikes that alarmed the Radicals and complicated Soviet foreign policy aims of alliance with France. In Spain, the Popular Front's narrow election victory in February 1936 was followed by  In China, the Comintern engaged with both the nationalist

In China, the Comintern engaged with both the nationalist  The Comintern's organizational structure was designed to be a centralized "world party". Its supreme body was the World Congress, which was supposed to meet annually (later less frequently) to decide on program and policy. Between congresses, the Comintern was directed by its Executive Committee (ECCI). The ECCI, in turn, elected a Presidium to handle day-to-day affairs, and a Secretariat. Other important bodies included the Organisational Bureau (Orgburo) and the International Control Commission (ICC), which was responsible for discipline and ideological purity. The International Liaison Department (, OMS), established in 1921, managed the Comintern's clandestine activities, including funding, communications, and forging documents.

The ECCI and its subsidiary bodies were based in Moscow. The statutes stipulated that the Communist Party of the host country (the Soviet Union) would have a disproportionate influence, holding five seats on the ECCI, while other major parties held one. National communist parties were considered "sections" of the Comintern, bound by its decisions.

The Comintern's organizational structure was designed to be a centralized "world party". Its supreme body was the World Congress, which was supposed to meet annually (later less frequently) to decide on program and policy. Between congresses, the Comintern was directed by its Executive Committee (ECCI). The ECCI, in turn, elected a Presidium to handle day-to-day affairs, and a Secretariat. Other important bodies included the Organisational Bureau (Orgburo) and the International Control Commission (ICC), which was responsible for discipline and ideological purity. The International Liaison Department (, OMS), established in 1921, managed the Comintern's clandestine activities, including funding, communications, and forging documents.

The ECCI and its subsidiary bodies were based in Moscow. The statutes stipulated that the Communist Party of the host country (the Soviet Union) would have a disproportionate influence, holding five seats on the ECCI, while other major parties held one. National communist parties were considered "sections" of the Comintern, bound by its decisions.