The Colombian–Peruvian territorial dispute was a territorial dispute between

Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

and

Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, which, until 1916, also included

Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

.

[Ecuador and Colombia signed the Muñoz Vernaza-Suárez Treaty in 1916, ending their dispute.] The dispute had its origins on each country's interpretation of what ''Real Cedulas'' (Royal Proclamations)

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

used to precisely define its possessions in the Americas. After

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, all of Spain's former territories signed and agreed to proclaim their limits in the basis of the principle of ''

uti possidetis juris

''Uti possidetis juris'' or ''uti possidetis iuris'' (Latin for "as oupossess under law") is a principle of international law which provides that newly-formed sovereign states should retain the internal borders that their preceding dependent are ...

'', which regarded the Spanish borders of 1810 as the borders of the new republics. However, conflicting claims and disagreements between the newly formed countries eventually escalated to the point of

armed conflict

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

s on several occasions.

The dispute between both states ended in the aftermath of the

Colombia–Peru War

The Colombia–Peru War, also called the Leticia War, was a short-lived armed conflict between Colombia and Peru over territory in the Amazon rainforest that lasted from September 1, 1932 to May 24, 1933. In the end, an agreement was reached to d ...

, which led to the signing of the

Rio Protocol

The Protocol of Peace, Friendship, and Boundaries between Peru and Ecuador, or Rio Protocol for short, was an international agreement signed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 29, 1942, by the foreign ministers of Peru and Ecuador, with the p ...

two years later, finally establishing a border agreed upon by both parties to the conflict.

Spanish era

At the beginning of the 18th century, the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

's

possessions in the Americas were initially divided into two

viceroyalties

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

: the

Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

and the

Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed from ...

. From these viceroyalties, new divisions would be later established to better administer the large territories in Central America, South America and the Caribbean.

On May 27, 1717, the

Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of New Granada ( es, Virreinato de Nueva Granada, links=no ) also called Viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada or Viceroyalty of Santafé was the name given on 27 May 1717, to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in norther ...

was established on the basis of the

New Kingdom of Granada

The New Kingdom of Granada ( es, Nuevo Reino de Granada), or Kingdom of the New Granada, was the name given to a group of 16th-century Spanish colonial provinces in northern South America governed by the president of the Royal Audience of Santa ...

, the

Captaincy General of Venezuela

The Captaincy General of Venezuela ( es, Capitanía General de Venezuela), also known as the Kingdom of Venezuela (), was an administrative district of colonial Spain, created on September 8, 1777, through the Royal Decree of Graces of 1777, t ...

and the

Royal Audience of Quito

The of Quito (sometimes referred to as or ) was an administrative unit in the Spanish Empire which had political, military, and religious jurisdiction over territories that today include Ecuador, parts of northern Peru, parts of southern Colo ...

. It would be temporarily dissolved on November 5, 1723, and its territories reincorporated into the Viceroyalty of Peru, but in 1739 it was re-established again and definitively, with the same territories and rights that it had according to the Royal Decree of 1717.

A series of royal decrees followed in the following century until 1819. The decree of 1802 would later serve as the basis of the

conflict

Conflict may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Conflict'' (1921 film), an American silent film directed by Stuart Paton

* ''Conflict'' (1936 film), an American boxing film starring John Wayne

* ''Conflict'' (1937 film) ...

between

Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

and

Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, with its existence being disputed by the former. The decree of 1740 has also been called into question by the latter, with some historians also questioning its existence.

After the

wars of independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List of o ...

, the new republics in South America agreed to proclaim their limits in the basis of the principle of ''

uti possidetis juris

''Uti possidetis juris'' or ''uti possidetis iuris'' (Latin for "as oupossess under law") is a principle of international law which provides that newly-formed sovereign states should retain the internal borders that their preceding dependent are ...

'', which regarded the Spanish borders of 1810 as the borders of the new states.

Wars of Independence

The formal independence of

Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

was declared on October 9, 1820, establishing the

Free Province of Guayaquil

The Free Province of Guayaquil was a South America, South American state that emerged between 1820 and 1822 with the Independent Guayaquil, independence of the province of Guayaquil from the Spanish Empire, Spanish monarchy. The free province had ...

and beginning the proclaimed state's independence campaign. Public opinion was divided into three: one part supported annexation to the

Protectorate of Peru

The Protectorate of Peru ( es, Protectorado del Perú, italic=yes), also known as the Protectorate of San Martín ( es, Protectorado de San Martín, italic=yes) was a protectorate created in 1821 in present-day Peru after its declaration of indep ...

, another annexation to the

Republic of Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

, and another supported independence.

Around the same time, a newly independent

Republic of Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

established three provinces in October 1821: the northern, central, and southern provinces. The latter nominally included the

Jaén de Bracamoros Province. The province, however, had declared itself part of the

Presidency of Trujillo on June 4, alongside

Tumbes on January 7 and

Maynas on August 19. With the entry of

San Martín

San Martín or San Martin may refer to:

People Saints

* Saint Martin (disambiguation)#People, name of various saints in Spanish

Political leaders

*Vicente San Martin (1839 -1901), Military, National hero of Mexico.

*Basilio San Martin (1849 ...

's troops into

Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

on June 9, the Peruvian proclamation of independence took place on July 28 of the same year, and Trujillo, Tumbes, Jaén and Maynas being integrated into the new state.

On July 22, 1822,

Antonio José de Sucre

Antonio José de Sucre y Alcalá (; 3 February 1795 – 4 June 1830), known as the "Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho" ( en, "Grand Marshal of Ayacucho"), was a Venezuelan independence leader who served as the president of Peru and as the second pr ...

ordered Jaén to swear to the Colombian constitution and thus, to form part of Colombia. The city rejected the mandate, arguing that it had deputies in the

Peruvian Congress

The Congress of the Republic of Peru ( es, Congreso de la República) is the unicameral body that assumes legislative power in Peru.

Congress' composition is established by Chapter I of Title IV of the Constitution of Peru. Congress is compose ...

.

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

himself made Sucre desist from his plans for the same reasons.

Gran Colombia–Peru conflict

The Guayaquil issue was approached with care by both countries, who signed a treaty on July 6, 1822, allowing special privileges to citizens of both states. The issue, yet to be resolved, was postponed.

On September 1, 1823, Simón Bolívar arrived in

Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists o ...

, aboard the brig ''Chimborazo'', invited by the Peruvian Congress to "consolidate the independence" of Peru. On December 18 of the same year, the Galdeano-Mosquera Agreement was signed in Lima, which established that "Both parties recognize the limits of their respective territories, the same ones that the former Viceroyalties of Peru and Nueva Grenada." It was approved by the Peruvian Congress, but months later the Colombian Congress disregarded the agreement.

On December 9, 1824, the

Battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho ( es, Batalla de Ayacucho, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of South America. In Peru it is co ...

took place, ending the war in Peru. After the fact, protests against Bolívar, who remained

Dictator of Peru, took place. During his government, the territorial question was not brought up, and governors in Jaén and Maynas were appointed, apparently recognizing Peru's ownership of the territories. In correspondence with

Francisco de Paula Santander

Francisco José de Paula Santander y Omaña (Villa del Rosario, Norte de Santander, Colombia, April 2, 1792 – Santafé de Bogotá, Colombia, May 6, 1840), was a Colombian military and political leader during the 1810–1819 independ ...

on August 3, 1822, Bolívar recognized that both Jaén and Maynas legitimately belonged to Peru.

With Bolívar withdrawing in 1826, liberal and nationalist elements in Peru put an end to the Bolivarian regime in January 1827. The new government dismissed the Colombian troops and expelled the Colombian diplomatic agent, Cristóbal Armero. Throughout the country, several protests were organized against Bolívar and Sucre. At the same time, the Peruvian army under the command of

Agustín Gamarra

Agustín Gamarra Messia (August 27, 1785 – November 18, 1841) was a Peruvian soldier and politician, who served as the 4th and 7th President of Peru.

Gamarra was a Mestizo, being of mixed Spanish and Quechua descent.Larned, Smith, Seymour, She ...

entered Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

and forced Sucre to resign from the presidency, ending Colombian influence in that country.

To remedy the crisis, Peru sent José Villa to Colombia as minister plenipotentiary. Bolívar refused to receive him and, through the Colombian foreign minister, asked Peru for explanations about the dismissal of Colombian troops, the intervention in Bolivia, the expulsion of Armero, the debt of independence and the restitution of Jaén and Maynas. Next, Villa received his passports.

The situation between Colombia and Peru worsened as time went by. On May 17, 1828, the Peruvian Congress authorized President

José de la Mar

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

to take military measures as a response to Villa's expulsion. On July 3, 1828, however, the Republic of Colombia officially declared war on the Peruvian Republic, beginning the

Gran Colombia–Peru War

The Gran Colombia–Peru War (Spanish: ''Guerra Grancolombo-Peruana'') of 1828 and 1829 was the first international conflict fought by the Republic of Peru, which had gained its independence from Spain in 1821, and Gran Colombia, that existed b ...

.

The

Peruvian Navy

The Peruvian Navy ( es, link=no, Marina de Guerra del Perú, abbreviated MGP) is the branch of the Peruvian Armed Forces tasked with surveillance, patrol and defense on lakes, rivers and the Pacific Ocean up to from the Peruvian littoral. Addit ...

blockaded the Colombian coast and besieged the port of

Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

, occupying it on January 19, 1829. The

Peruvian Army

The Peruvian Army ( es, Ejército del Perú, abbreviated EP) is the branch of the Peruvian Armed Forces tasked with safeguarding the independence, sovereignty and integrity of national territory on land through military force. Additional missions ...

occupied

Loja and

Azuay

Azuay (), Province of Azuay is a province of Ecuador, created on 25 June 1824. It encompasses an area of . Its capital is Cuenca. It is located in the south center of Ecuador in the highlands. Its mountains reach above sea level in the nationa ...

. Despite the initial success of the Peruvian Army, however, the war ended with the

Battle of Tarqui

The Battle of Tarqui, also known as the Battle of Portete de Tarqui, took place on 27 February 1829 at Tarqui, near Cuenca, today part of Ecuador. It was fought between troops from Gran Colombia, commanded by Antonio José de Sucre, and Peruvian ...

, on February 27, 1829; and with the signing of the

Girón Agreement the following day.

The Agreement was disapproved by Peru due to Colombian actions considered offensive. Therefore, La Mar was willing to continue the war, but was overthrown by

Agustín Gamarra

Agustín Gamarra Messia (August 27, 1785 – November 18, 1841) was a Peruvian soldier and politician, who served as the 4th and 7th President of Peru.

Gamarra was a Mestizo, being of mixed Spanish and Quechua descent.Larned, Smith, Seymour, She ...

. The latter, wishing to end the conflict, signed the

Piura Armistice that stipulated the suspension of hostilities and the return of Guayaquil. To put a definitive end to the dispute, the representatives of Peru and Colombia, José Larrea and Pedro Gual respectively, met in Guayaquil, and on September 22, 1829, the

Larrea-Gual Treaty

The Treaty of Guayaquil, officially the Treaty of Peace Between Colombia and Peru, and also known as the Larrea–Gual Treaty after its signatories, was a peace treaty signed between Gran Colombia and Peru in 1829 that officially put an end to the ...

was signed, which constituted a treaty of peace and friendship, but not limits. Its articles 5 and 6 established the basis that should serve for the delimitation between the two countries and the procedure that would be used for it. As for the procedure to carry out said delimitation, it ordered that a Commission of two people for each republic should be appointed to go over, rectify and fix the dividing line, work that should begin 40 days after the treaty had been ratified by both countries. The tracing of the line would start at the

Tumbes River

The Tumbes River ( es, Río Tumbes or Río Túmbez in Peru; Río Puyango in Ecuador), is a river in South America. The river's sources are located between Ecuadorian El Oro and Loja provinces. It is the border between El Oro and Loja, and afterw ...

. In case of disagreement, it would be submitted to arbitration by a friendly government. The delimitation mission did not take place, however, as problems took place, such as both parties arrived at different times, and the

dissolution of Gran Colombia itself into

New Granada New Granada may refer to various former national denominations for the present-day country of Colombia.

*New Kingdom of Granada, from 1538 to 1717

*Viceroyalty of New Granada, from 1717 to 1810, re-established from 1816 to 1819

*United Provinces of ...

,

Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

and

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, which further complicated the issue.

Conflict with Brazil and Ecuador

With Gran Colombia dissolved, the conflict now included the newly formed

Republic of Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

and the

Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and (until 1828) Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Dom Pe ...

.

Creation of Popayán Province

After the separation, Nueva Granada was constituted territorially according to the division of 1810. Thus,

Popayán Province Popayán Province was first a Spanish jurisdiction under the Royal Audience of Quito and the Royal Audience of Santafé , and after the independence one of the provinces of the Cauca Department (Gran Colombia), later becoming the Republic of New Gra ...

was created, which established the Napo River and its confluence with the Amazon as its southern limit.

Ecuadorian–Colombian War

On February 7, 1832, due to territorial disputes over the provinces of Pasto,

Popayán

Popayán () is the capital of the Colombian departments of Colombia, department of Cauca Department, Cauca. It is located in southwestern Colombia between the Cordillera Occidental (Colombia), Western Mountain Range and Cordillera Central (Colo ...

and

Buenaventura, the republics of New Granada and Ecuador went to war. The conflict was favorable for the former and ended with the Treaty of Pasto, which only delimited the first section of the

border

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders c ...

between the two nations: the

Carchi River

The Carchi River is a river of Ecuador. It rises on the slopes of Chiles Volcano, elevation , on the border of Ecuador and Colombia. The river flows eastward across the high plateau of El Angel. The Carchi has a total course of about , forming ...

.

Pando–Noboa Treaty

Peru recognized Ecuador as an independent nation, and received its representative in Lima, Diego Noboa. On July 12, 1832, two agreements were concluded: one of friendship and alliance, and another of trade. They were approved by the Congresses of both countries, and the respective ratifications were exchanged.

The treaty is important because it recognized the existing limits, that is, the possessory state of Peru of Tumbes, Jaén and Maynas (against the interests of Granada) and, that of Ecuador, of Quito, Azuay and Guayaquil; until the signing of a definitive boundary treaty.

The

Granadine minister in Lima, José del C. Triunfo, considered that the treaty violated the rights of his country, and raised a protest against it.

Creation of Amazonas Department

On November 21, 1832, the Peruvian Congress created the

Department of Amazonas

Amazonas () is a department of Southern Colombia in the south of the country. It is the largest department in area while also having the 3rd smallest population. Its capital is Leticia and its name comes from the Amazon River, which drains the ...

, made up of the provinces of

Chachapoyas,

Pataz and

Maynas; separating from the

Department of La Libertad

La Libertad (; in English: ''The Liberty'') is a region in northwestern Peru. Formerly it was known as the Department of La Libertad ('). It is bordered by the Lambayeque, Cajamarca and Amazonas regions on the north, the San Martín Region on t ...

.

Juan José Flores and Peru

Juan José Flores

Juan José Flores y Aramburu (19 July 1800 – 1 October 1864) was a Venezuelan-born military general who became the first (in 1830), third (in 1839) and fourth (in 1843) President of the new Republic of Ecuador. He is often referred to as "The ...

assumed the government of Ecuador again in 1839. His foreign policy corresponded to his desire to expand the Ecuadorian territory to the detriment of New Granada and Peru. His expansionist spirits increased when, after the dissolution of the

Peru-Bolivian Confederation, numerous political voices from the ephemeral state revived the Bolivarian claim of Tumbes, Jaén and Maynas.

Then, two negotiations took place between both countries: between the Peruvian ministers Matías León and Agustín Guillermo Charún, and the Ecuadorians José Félix Valdivieso and Bernardo Daste, which failed. However, its importance lies in the fact that for the first time Peru based its rights over Maynas invoking the Royal Decree of 1802 (then lost) and the self-determination of peoples, as it would also do in future negotiations with Colombia.

''Real Cédula'' of 1802 published

On March 3, 1842, the recently founded newspaper

El Comercio published for the first time the text of the ''Real Cédula'' of 1802, whose existence had been questioned and doubted. About the original, the same newspaper indicated that there was a copy in the

High Court of Accounts and another in the archive of the

convent of Ocopa, transferred to Lima. The official files were lost during a fire.

[ Basadre, Vol. 2, p. 241.]

Referendum in Maynas Province

In May 1842, acts were signed in the province of Maynas, which ratified the will of its inhabitants to belong to Peru.

[

]

Creation of Caquetá Territory

On May 2, 1845, the Caquetá Territory

The Caquetá Territory ( es, Territorio del Caquetá) was a national territory of the Republic of New Granada and the subsequent states of the Granadine Confederation and the United States of Colombia from 1845 to 1886. Its capital was Mocoa.

Hi ...

was separated from Popayán Province Popayán Province was first a Spanish jurisdiction under the Royal Audience of Quito and the Royal Audience of Santafé , and after the independence one of the provinces of the Cauca Department (Gran Colombia), later becoming the Republic of New Gra ...

. The city of Mocoa

Mocoa () (Kamsá: Shatjok) is a municipality and capital city of the department of Putumayo in Colombia.

The city is located in the northwest of the Putumayo department

Putumayo () is a department of Southern Colombia. It is in the south-w ...

was designated as the capital, covering the territories bathed by the Caquetá, Putumayo, Napo and Amazon rivers, from the border with Ecuador to Brazil.

1851 Treaty between Peru and Brazil

On October 23, 1851, a fluvial convention was signed by Bartolomé Herrera (for Peru) and Duarte Da Ponte Ribeyro (for Brazil). In its eight article, the first section of the border of both countries was delimited: the and the Yavarí River

The Javary River, Javari River or Yavarí River ( es, Río Yavarí, links=no; pt, Rio Javari, links=no) is a tributary of the Amazon that forms the boundary between Brazil and Peru for more than . It is navigable by canoe for from above its ...

.

When the Granadine government was made aware of this agreement, it ordered its minister in Chile, Manuel Ancízar

Manuel Esteban Ancízar Basterra (25 December 1812 — 21 May 1882) was a Colombian lawyer, writer, and journalist. He founded a publishing house and a newspaper before joining the Chorographic Commission in 1850. He also served as the 4th ...

, to raise a protest in April 1853; stating that it violated the Treaty of San Ildefonso of 1777.

Creation of the Political and Military Government of Loreto

On March 10, 1853, the Peruvian government created the Political and Military Government of Loreto, assigning the city of Moyobamba

Moyobamba () or Muyupampa ( Quechua ''muyu'' circle, ''pampa'' large plain, "circle plain") is the capital city of the San Martín Region in northern Peru. Called "Santiago of eight valleys of Moyobamba" or "Maynas capital". There are 50,073 inha ...

as its capital. It covered the territories and missions located to the north and south of the Amazon and its respective tributaries, in accordance with the Royal Decree of 1802.

Given this fact, the Plenipotentiary Minister of New Granada in Lima, Mariano Arosemena, and that of Ecuador, Pedro Moncayo

Pedro Moncayo y Esparza (29 June 1807 in Ibarra, Ecuador — February 1888 in Valparaíso, Chile) was an Ecuadorian journalist and politician. He was the son of an Ecuadorian mother and Colombian father. He was politically active during the perio ...

, raised a protest. José Manuel Tirado, then Foreign Minister of Peru, maintained that, according to the ''uti possidetis iure'' of 1810, those territories belonged to his country. He based himself on the Royal Decree of 1802 and the self-determination of peoples.

1853 Ecuadorian Law

On November 26, 1853, the Ecuadorian Congress enacted a law, declaring "free navigation of the Chinchipe, Santiago, Morona

The Morona River is a tributary to the Marañón River, and flows parallel to the Pastaza River and immediately to the west of it, and is the last stream of any importance on the northern side of the Amazon before reaching the Pongo de Manseriche.

...

, Pastaza, Tigre, Curaray

The Curaray River (also called the Ewenguno River or Rio Curaray) is a river in eastern Ecuador and Peru. It is a tributary of the Napo River, which is a part of the Amazon basin. The land along the river is home to several indigenous people group ...

, Nancana, Napo, Putumayo and other Ecuadorian rivers that descend to the Amazon." The Peruvian Minister Plenipotentiary in Quito, Mariano José Sanz León, forwarded his protest.

1856 Treaty of Bogotá

On July 9, 1856, the plenipotentiary minister of New Granada, Lino de Pombo; and that of Ecuador, Teodoro Gómez de la Torre, signed a treaty, in which the provisional limits between both nations were recognized as those defined by the Colombian law of July 25, 1824, annulling what was decreed by the Treaty of Pasto.

Creation of the Federal State of Cauca

On June 15, 1857, within the Granadina Confederation, the Federal State of Cauca

Cauca State was one of the states of Colombia.

Today the area of the former state makes up most of modern-day west and southern Colombia, with some portion of its vast territories acquired by present-day Peru, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela.

Na ...

was created. The city of Popayán

Popayán () is the capital of the Colombian departments of Colombia, department of Cauca Department, Cauca. It is located in southwestern Colombia between the Cordillera Occidental (Colombia), Western Mountain Range and Cordillera Central (Colo ...

was designated as its capital and its limits to the south extended from the mouth of the Mataje River

The Mataje River is a South American river belonging to the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on ...

to the mouth of the Yavarí River in the Amazon.

Arbitration of Chile between New Granada and Ecuador

In 1858, the governments of New Granada and Ecuador decided to go to arbitration in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, to resolve conflicts in the Amazon region. The arguments were presented by Florentino González, on behalf of Nueva Granada; and Vicente Piedrahíta, for Ecuador. However, the Chilean government did not issue a ruling, due to the vagueness of its powers and the lack of a formal commitment.

Ecuadorian–Peruvian War

On October 26, 1858, the war between Peru and Ecuador began, because, according to the Peruvian plenipotentiary Juan Celestino Cavero, the Ecuadorian government decided to settle its foreign debt with

On October 26, 1858, the war between Peru and Ecuador began, because, according to the Peruvian plenipotentiary Juan Celestino Cavero, the Ecuadorian government decided to settle its foreign debt with England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

by ceding Peruvian Amazonian territories. After a successful blockade campaign of the Ecuadorian coast and the occupation of Guayaquil, the Franco-Castile Treaty, also called the Treaty of Mapasingue, was signed. In this document, the validity of the Royal Decree of 1802 and the ''uti possidetis'' of 1810 were recognized:

The Boundary Commission between Brazil and Peru

In accordance with the 1851 treaty between Peru and Brazil, both governments appointed their respective commissioners in 1866 to place the respective milestones from the mouth of the Apaporis, continuing through the Putumayo (where there were some exchanges of territories) and exploring the Yavarí River, determining (incorrectly) its origin at coordinates , when in fact it is at coordinates .

Direct negotiations

First Spanish arbitration

In 1887, the Ecuadorian government tried to renew the cession of territories to an English company. Peruvian Foreign Minister Cesáreo Chacaltana raised his protest and his government proposed taking the border problem to arbitration in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. Through the Espinoza-Bonifaz Arbitration Agreement, both parties agreed to submit the border problem to arbitration by the King of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

. Both countries presented their arguments in 1889: Peru, through its commissioner José Pardo y Barreda

José Simón Pardo y Barreda (February 24, 1864 – August 3, 1947) was a Peruvian politician who served as the 35th (1904–1908) and 39th (1915–1919) President of Peru.

Biography

Born in Lima, Peru, he was the son of Manuel Justo Pardo y L ...

; however, the Ecuadorian document was lost, so a copy had to be sent.

García–Herrera Treaty

The García-Herrera Treaty was a border treaty between Ecuador and Peru signed in 1890 but never effective.

The Foreign Minister of Ecuador, Carlos R. Tobar, proposed to his Peruvian counterpart, Isaac Alzamora, to enter into direct negotiations to definitively resolve the boundary dispute, dispensing with Spanish arbitration. Alzamora, in turn, accepted, and sent Arturo García as representative, initiating discussions with his Ecuadorian counterpart Pablo Herrera González.

In order to counter popular opinion, the Peruvian government of Andrés Avelino Cáceres

Andrés Avelino Cáceres Dorregaray (November 10, 1836 – October 10, 1923) served as the President of Peru two times during the 19th century, from 1886 to 1890 as the 27th President of Peru, and again from 1894 to 1895 as the 30th Preside ...

at first stressed the importance of such a treaty, due to a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

regarding Tacna and Arica, territories occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October 2 ...

by Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

since the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific ( es, link=no, Guerra del Pacífico), also known as the Saltpeter War ( es, link=no, Guerra del salitre) and by multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought ...

.

Disagreements soon appeared, as the Peruvian government presented revisions to the treaty, which Ecuador refused to accept. At the same time, Peru refused to accept the original proposal. As a result of these disagreements, the treaty was never applied.

In 1890 and 1891, the Colombian government raised its protest in both Quito and Lima, since this treaty interfered with its claims in the Napo and Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technology c ...

rivers.

1890 Colombian Law

On December 22, 1890, the Colombian Congress

The Congress of the Republic of Colombia ( es, Congreso de la República de Colombia) is the name given to Colombia's bicameral national legislature.

The Congress of Colombia consists of the 108-seat Senate, and the 188-seat Chamber of Re ...

issued a law by which authorizations were given to create missions and police services in the regions bathed by the Caquetá, Putumayo, Amazonas rivers and their tributaries.

Peruvian Foreign Minister Alberto Elmore raised his protest on April 8, 1891, considering that the law violated the territorial rights of Peru, in accordance with the Royal Decree of 1802 and the possession of his country, since the inhabitants of those places obeyed the laws, the regulations and the Peruvian authorities of the Department of Loreto

Loreto () is Peru's northernmost department and region. Covering almost one-third of Peru's territory, Loreto is by far the nation's largest department; it is also one of the most sparsely populated regions due to its remote location in the Amaz ...

. His Colombian peer, Marco Fidel Suárez, indicated that:

1894 Tripartite Conferences

The Colombian government, on the occasion of the diplomatic efforts between Ecuador and Peru, requested to be admitted to the boundary discussions in order to reach a definitive agreement; such efforts culminated with the tripartite convention meeting in Lima on October 11, 1894. Aníbal Galindo, as special lawyer, and Luis Tanco, who was chargé d'affaires in Lima, were appointed as representatives for Colombia; for Ecuador, Julio Castro, extraordinary envoy and plenipotentiary minister of Ecuador in Lima; and for Peru, Luis Felipe Villarán, as special counsel.

The Colombian government, on the occasion of the diplomatic efforts between Ecuador and Peru, requested to be admitted to the boundary discussions in order to reach a definitive agreement; such efforts culminated with the tripartite convention meeting in Lima on October 11, 1894. Aníbal Galindo, as special lawyer, and Luis Tanco, who was chargé d'affaires in Lima, were appointed as representatives for Colombia; for Ecuador, Julio Castro, extraordinary envoy and plenipotentiary minister of Ecuador in Lima; and for Peru, Luis Felipe Villarán, as special counsel.[ Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 40.]

Upon entering the dispute, Colombia upheld the recognition of the ''uti possidetis'', but integrating and replacing it (in cases of obscurity and deficiency) with the principle of equity and reciprocal convenience. According to his thesis, the arbitrator should not only attend to the titles of law, but also the interests of the countries in dispute.

Colombia defined its position on the General Command of Maynas, which was disputed by the three countries. Peru maintained that, according to the ''uti possidetis'', the territory belonged to Peru, as mandated by the Royal Decree of 1802; while Ecuador had maintained its non-existence and, when the certificate was presented, its non-compliance. For its part, Colombia disputed the legal nature of the document, and argued that it was not a political or civil demarcation, but an ecclesiastical order. Thus, the intention of the royal act was to place the ecclesiastical missions in Maynas under the supervision of the Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed from ...

, but depending politically on that of New Granada New Granada may refer to various former national denominations for the present-day country of Colombia.

*New Kingdom of Granada, from 1538 to 1717

*Viceroyalty of New Granada, from 1717 to 1810, re-established from 1816 to 1819

*United Provinces of ...

.

Regarding the possible rights of Ecuador, Colombia argued that these do not start from the certificate of erection of the Audiencia de Quito, since this was never an autonomous entity, but dependent on the viceroyalties of Peru and New Granada. Due to this, the ''uti possidetis'' cannot be claimed in its favor, which is only valid for territorial divisions such as the viceroyalties and the general captaincies. The Ecuadorian nation and its rights were born on February 10, 1832, when Colombia recognized the separation of the provinces of Ecuador, Azuay and Guayaquil, to form an independent state.

The arbitration agreement was signed on December 15, 1894, since the three countries did not reach an agreement on their arguments. The first article said:

The congresses of Colombia and Peru approved the agreement, but not Ecuador, who refrained from doing so. Colombia, for its part, and given Ecuador's conduct, preferred to engage in direct negotiations.Bustillo Bustillo may refer to: Places

* Bustillo de Chaves, municipality in the province of Valladolid, Spain

* Bustillo del Oro, municipality in the province of Zamora, Spain

* Bustillo del Páramo de Carrión, place in the province of Palencia, Spain

* ...

1916, p. 39.[

]

Abadía Méndez-Herboso Protocol

On September 27, 1901, a protocol was signed between Colombian Foreign Minister Miguel Abadía Méndez

Miguel Abadía Méndez (June 5, 1867 – May 9, 1947) was the 12th President of Colombia (1926–1930). A Conservative party politician, Abadía was the last president of the period known as the Conservative Hegemony, running unopposed and fo ...

and the Chilean plenipotentiary in Bogotá, Francisco J. Herboso, establishing an alliance between Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, Colombia and (presumably) Ecuador. The Colombian-Chilean negotiations continued, which included the sale of an armored vehicle of the Chilean Navy

The Chilean Navy ( es, Armada de Chile) is the naval warfare service branch of the Chilean Armed Forces. It is under the Ministry of National Defense. Its headquarters are at Edificio Armada de Chile, Valparaiso.

History

Origins and the Wars ...

, which was, at that time, one of the most powerful in America and the world. This was frustrated, however, by the discovery and publication of these documents by the Peruvian plenipotentiary in Colombia, Alberto Ulloa Cisneros.

Rubber boom, later treaties, and the ''modus vivendi''

Pardo-Tanco Argáez Treaty

On May 6, 1904, a treaty was signed in Lima between the Peruvian Foreign Minister José Pardo y Barreda and the Colombian Plenipotentiary Luis Tanco Argáez, which submitted the question of limits to the arbitration of the King of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

. That same day, a ''modus vivendi

''Modus vivendi'' (plural ''modi vivendi'') is a Latin phrase that means "mode of living" or " way of life". It often is used to mean an arrangement or agreement that allows conflicting parties to coexist in peace. In science, it is used to descr ...

'' was signed in the Napo and Putumayo areas. However, it was not approved by Colombian Foreign Minister Francisco de Paula Matéus, arguing that Tanco had no instructions.

Tobar–Río Branco Treaty

The Tobar–Río Branco Treaty was signed between Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

on May 4, 1904, the same day as the signing of the ''modus vivendi'' between Colombia and Peru. The governments of Ecuador (represented by Carlos R. Tobar) and Brazil (represented by José Paranhos

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced ...

) signed a treaty, in which they defined their border in the . According to a 1851 treaty, the border was originally defined as being between Peru and Brazil.

Velarde-Calderón-Tanco Treaties

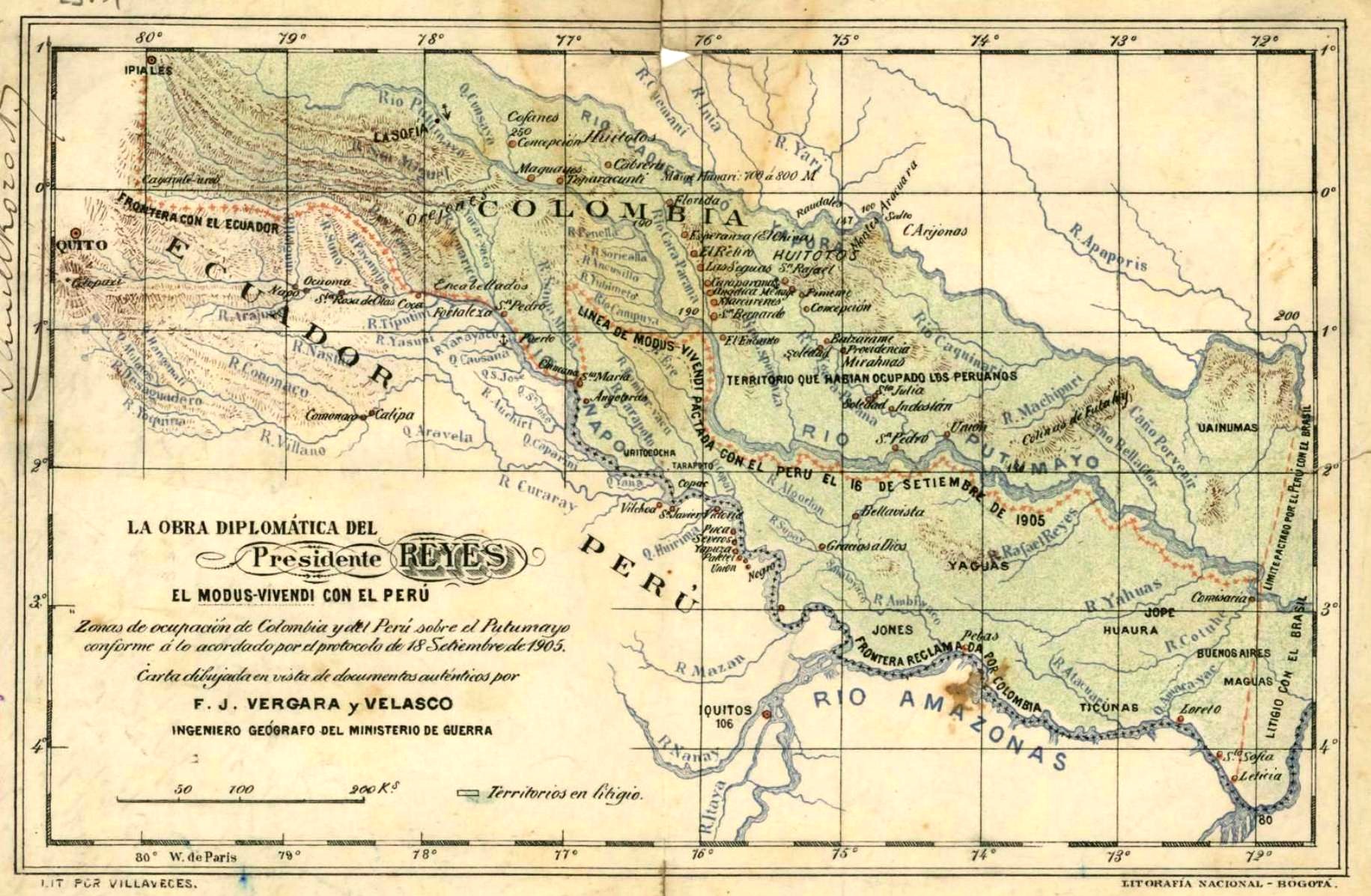

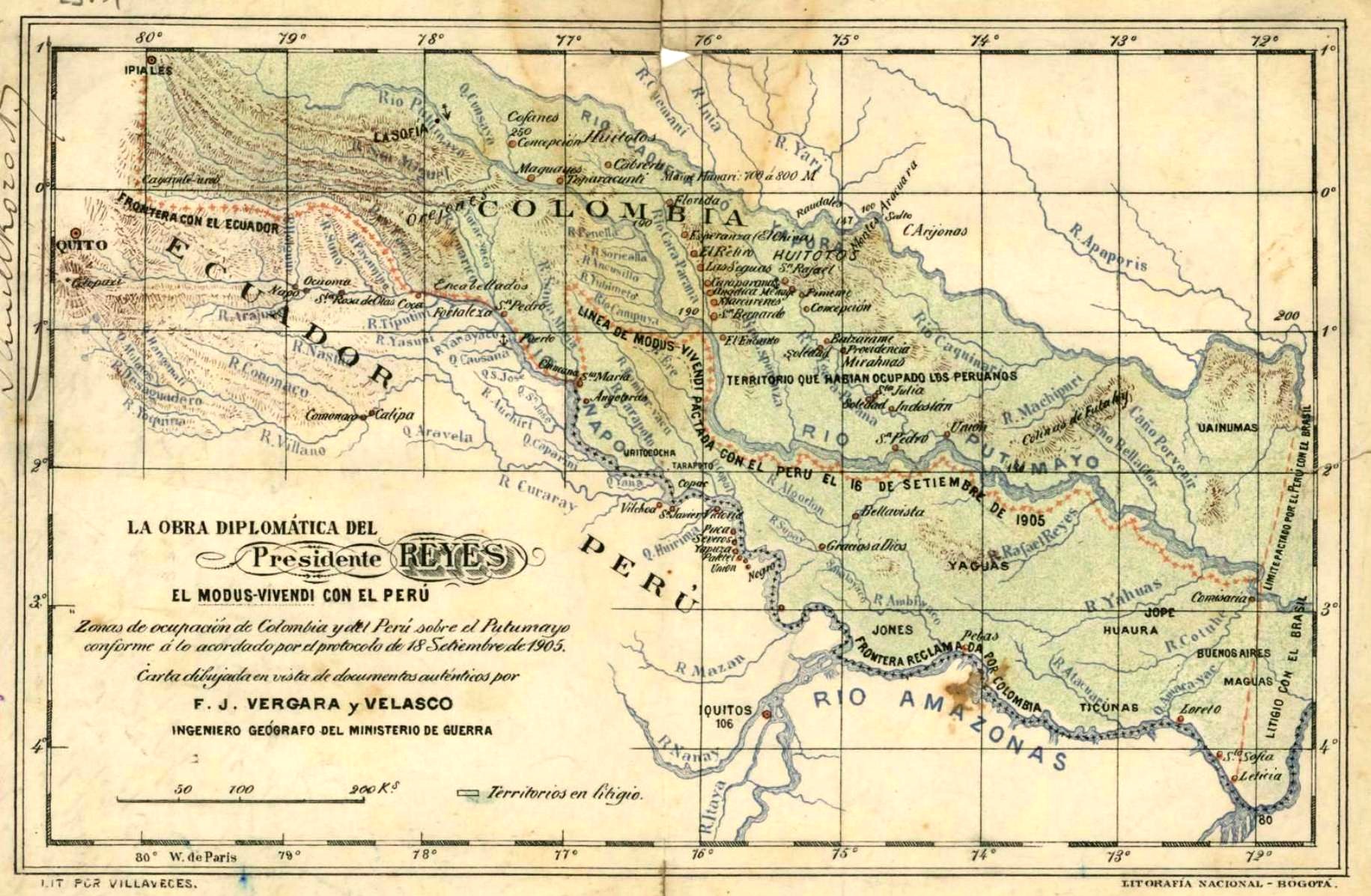

On September 12, 1905, the new Peruvian legation in Bogotá (directed by the Peruvian plenipotentiary Hernán Velarde) managed to celebrate three new conventions with the Colombian Foreign Ministry: the Velarde-Calderón-Tanco treaties, with

On September 12, 1905, the new Peruvian legation in Bogotá (directed by the Peruvian plenipotentiary Hernán Velarde) managed to celebrate three new conventions with the Colombian Foreign Ministry: the Velarde-Calderón-Tanco treaties, with Clímaco Calderón

Clímaco Calderón Reyes (August 23, 1852 – July 19, 1913) was a Colombian lawyer and politician, who became 15th President of Colombia for one day, following the death of President Francisco Javier Zaldúa.

Biographic data

Calderón was b ...

, Foreign Minister of Colombia; and the Colombian Minister Plenipotentiary in Peru, Luis Tanco Argáez.

The first agreement was a general arbitration agreement, by which both countries undertook to resolve all their differences, except those that affected national independence or honor, through arbitration. The referee would be the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

. The arbitration commitment would last 10 years, with the contentious issues presented to the arbitrator by special conventions.

The second agreement submitted the question of limits to Pius X

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of C ...

, or in his refusal or impediment, to the President of the Argentine Republic; establishing the principles of law and equity. The arbitration should only be initiated when the litigation between Peru and Ecuador, pending before the King of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

, is over.

The third treaty was the status quo and modus vivendi in the disputed area. Neither of the two countries would alter their positions until the dispute was resolved. Meanwhile, the dividing line would be the Putumayo River, which would be neutral. Colombia would occupy the left margin and Peru, the right margin. Customs would be mixed and the product of these common.[

The agreements were approved by the Colombian Congress and sent for ratification in Lima. However, it seems that due to the enormous influence of the powerful '' Casa Arana'', its approval was delayed.

In this context, on June 6, 1906, a ''status quo'' protocol was signed in Lima in the disputed area and a ''modus vivendi'' in the Putumayo, a river declared neutral. Garrisons, customs, and civil and military authorities were withdrawn until the border conflicts were resolved. These measures would indirectly barbarize the region.

]

The rubber boom and the Putumayo genocide

Rubber exploitation had radically changed the lives of the inhabitants of the Amazon. Iquitos

Iquitos (; ) is the capital city of Peru's Maynas Province and Loreto Region. It is the largest metropolis in the Peruvian Amazon, east of the Andes, as well as the ninth-most populous city of Peru. Iquitos is the largest city in the world th ...

, Manaus

Manaus () is the capital and largest city of the Brazilian state of Amazonas. It is the seventh-largest city in Brazil, with an estimated 2020 population of 2,219,580 distributed over a land area of about . Located at the east center of the s ...

and Belém

Belém (; Portuguese for Bethlehem; initially called Nossa Senhora de Belém do Grão-Pará, in English Our Lady of Bethlehem of Great Pará) often called Belém of Pará, is a Brazilian city, capital and largest city of the state of Pará in t ...

received a great economic boost at that time. On the Peruvian side, '' Casa Arana'' was the owner of all the rubber territories from the Amazon to the current Colombian territory. His enormous commercial successes pushed him to create a company called the ''Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company'', incorporated on September 27, 1907, with a capital of one million pounds sterling. The board was made up of Henry M. Read, Sir John Lister Kaye, John Russel Gubbins, Baron de Souza Deiro, M. Henri Bonduel, Abel Alarco, and Julio Cesar Arana.[ Valcárcel 2004, pp. 51.]

On August 9, 1907, Benjamín Saldaña Roca filed a criminal complaint in Iquitos against the employees of Arana's company. The accusation pointed out that horrible crimes were being committed against the indigenous people of Putumayo: rapes, torture, mutilations and murders. In Lima, the news was published by the newspaper La Prensa on December 30, 1907.[ However, under the pretext that, due to the modus vivendi agreed upon the previous year, the Peruvian authorities did not have authority over the area between the Putumayo and Caquetá, the complaint was filed.

In 1909, American citizens Hardenburg and Perkins were imprisoned by the Casa Arana because, according to them, they were reproached for the exploitation of indigenous people and workers in general. According to the company, Hardenburg had tried to blackmail them, indicating "that he had in his possession very compromising documents for the Peruvian Amazon Co."

The following year, the world press was agitated by the so-called Putumayo scandals, thanks to Hardenburg's denunciation, who indicated the chilling figure of 40,000 murdered natives. The brutal crimes against the indigenous people, committed in that area by both Peruvians and Colombians, shook public opinion in ]Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

; even more so, when it was discovered that the accused for the terrible abuses had British capital. Sir Roger Casement

Roger David Casement ( ga, Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916), known as Sir Roger Casement, CMG, between 1911 and 1916, was a diplomat and Irish nationalist executed by the United Kingdom for treason during Worl ...

, the British consul in Manaus, was sent to investigate these events. Casement was already world famous, due to his denunciation of the abuse and mistreatment to which the native population in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

was subjected.[ Palacios y Safford, p. 515.]

The Supreme Court of Peru

The Supreme Court of Justice is the highest judicial court in Peru. Its jurisdiction extends over the entire territory of the nation. It is headquartered in the Palace of Justice (Peru), Palace of Justice in Lima.

Structure

The supreme court is ...

appointed, thanks to a complaint from the Attorney General of the Nation on August 8, 1910, a commission to investigate what happened in those territories. Carlos A. Valcárcel received the orders in November of that year, and on the 22nd, ordered that the alleged culprits be prosecuted. However, due to health problems and lack of money, Valcárcel was unable to take charge of the investigation, so he was replaced by Rómulo Paredes.

Casement's report was presented at the beginning of 1911. In it, the horrible practices of the Arana house were described. The recruitment of natives at the hands of Peruvians and Colombians, slavery, sexual exploitation of women, the death of thousands of Amazonian indigenous people; which confirmed the allegations made earlier. Despite this, Julio César Arana would never be tried for his alleged crimes, neither before the House of Commons of Great Britain, nor before the Peruvian justice system. He would become a senator from Loreto and an opponent of the Salomón-Lozano Treaty.[

]

Putumayo–Caquetá armed incidents

Despite the agreements signed with Peru, on June 5, 1907, the Colombian government secretly held a convention with Ecuador, to negotiate a border agreement in the territories that were also in dispute with Peru. At the same time, it demanded that this country approve the 1905 treaty (which did not happen).

Given this, on October 22, 1907, the Colombian government unilaterally declared the modus vivendi of 1906 ended, appointing and sustaining authorities in Putumayo. Because of this, the Peruvian Foreign Ministry asked Julio C. Arana to help with his employees to repel a possible Colombian invasion. As a consequence of these two actions, a series of armed incidents took place between Peruvian and Colombian rubber tappers in the area.

Vásquez Cobo-Martins Treaty

On April 24, 1907, it was signed in Bogotá

Bogotá (, also , , ), officially Bogotá, Distrito Capital, abbreviated Bogotá, D.C., and formerly known as Santa Fe de Bogotá (; ) during the Spanish period and between 1991 and 2000, is the capital city of Colombia, and one of the larges ...

, between the representatives of the governments of Colombia and Brazil; Alfredo Vásquez Cobo and Enéas Martins, respectively, a treaty that defined the border, between the Cocuy stone to the mouth of the Apaporis River in Caquetá.

Porras-Tanco Argáez Treaty

In 1909, negotiations were resumed between Peru and Colombia, in order to put an end to the conflict taking place between Putumayo and Caquetá. The Peruvian foreign minister, Melitón Porras, and the Colombian minister, Luis Tanco Argáez, signed an agreement on April 22 of that year, which consisted of the following points:[ Porras Barrenechea, p. 51-52.]

*The appointment of a commission to investigate the events in Putumayo and establish responsibilities.

*The material damages and the families of the victims would be compensated.

*The question of limits would be resolved when the Spanish ruling was issued in the lawsuit with Ecuador and would be submitted to arbitration in case of disagreement.

*A new modus vivendi would be agreed upon.

*A trade agreement would be adjusted.

In compliance with the first part of the treaty, the convention on claims was signed in Bogotá on April 13, 1910. The constitution of an international mixed tribunal that would meet in Rio de Janeiro 4 months after the signing of the convention was agreed upon. The court had to decide:[

*The amount of compensation that one of the countries had to pay to another

*Determine the cases in which Colombian or Peruvian law should be applied to those presumed guilty of crimes in the region.

However, regarding the arbitration and modus vivendi agreements agreed upon in the Porras-Tanco Argáez treaty, no formal agreement was reached.

]

La Pedrera Conflict

In 1911, Colombia began to establish military garrisons on the left bank of the Caquetá River, in clear violation of the Porras-Tanco Argáez treaty, which established that this area was Peruvian territory. An expedition commanded by General Isaac Gamboa, made up of 110 men, occupied Puerto Córdoba, also called La Pedrera. In June, another expedition sailed to Puerto Córdoba under the command of General Neyra.

Meanwhile, the Peruvian government, safeguarding its interests in the area that were being threatened by the Colombian expeditions, requested the suspension of the Neyra expedition, but was denied. Then, the Loreto authorities sent out a Peruvian contingent, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Óscar R. Benavides

Óscar Raymundo Benavides Larrea (March 15, 1876 – July 2, 1945) was a Peruvian field marshal, diplomat, and politician who served as the 38th (1914 – 1915, by a coup d'etat) and 42nd (1933 – 1939) President of Peru.

Early life

He was b ...

, to evict the Colombians from La Pedrera.

It was then that the consuls of Peru and Colombia in Manaus, aware of the consequences of a possible confrontation, telegraphically proposed to their governments the diversion of the expeditions: the Colombian expedition, commanded by Neyra, would stop in Manaus; and the Peruvian, from Benavides, in Putumayo.

However, due to lack of knowledge of these negotiations, an armed clash took place between the Peruvian and Colombian forces. On July 10, Benavides demanded the withdrawal of the Colombians from La Pedrera, which was denied. For this reason, the attack on Puerto Córdoba began: after two days of fighting, the Colombian contingent was forced to withdraw.

On July 19, 1911, a week after the clashes in La Pedrera, the Peruvian Minister Plenipotentiary Ernesto de Tezanos Pinto and the Colombian Foreign Minister Enrique Olaya Herrera

Enrique Alfredo Olaya Herrera (12 November 1880 – 18 February 1937) was a Colombian journalist and politician. He served as President of Colombia from 7 August 1930 until 7 August 1934 representing the Colombian Liberal Party.

Early years

...

signed the Tezanos Pinto-Olaya Herrera Agreement in Bogotá. In this agreement, Colombia undertook not to increase the contingent located in Puerto Córdoba and not to attack the Peruvian positions located between Putumayo and Caquetá. At the same time, the Peruvian troops were forced to abandon La Pedrera and return the captured war trophies to the Colombians.

Muñoz Vernaza-Suárez Treaty

On July 15, 1916, the plenipotentiary minister of Ecuador, Alberto Muñoz Vernaza; and that of Colombia, Fidel Suárez, signed in Bogotá the , a boundary treaty between the two republics, from the Mataje River to the mouth of the Ambiyacú River in the Amazon:

Peru duly made a reservation of its rights affected by said pact.[ Porras Barrenechea, p. 54.]

Colombia–Peru negotiations

After the La Pedrera incident, relations between Colombia and Peru were disturbed: Colombian civilians stoned the house of the Peruvian ambassador in Bogotá and their press attacked the attitude of their government. The separation of Panama, a very sensitive episode, was still in the collective mind, being referred to when talking about Caquetá. Meanwhile, the foreign ministries of both countries were concerned with initiating new negotiations. Between 1912 and 1918, both countries insisted on the idea of arbitration. Colombia, led by the conservatives, proposed the arbitration of the Pope: Peru, on the other hand, proposed as arbitrator the Court of The Hague

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordanc ...

or the President of the Swiss Confederation

The president of the Swiss Confederation, also known as the president of the Confederation or colloquially as the president of Switzerland, is the head of Switzerland's seven-member Federal Council (Switzerland), Federal Council, the country's ...

.

In 1919, a new phase of the conflict began. Colombia proposes a direct settlement, however, the line proposed by Colombian Minister Fabio Lozano Torrijos to the Peruvian Foreign Ministry was not accepted, since it did not imply any cession by Colombia. The Peruvian counterproposal was also not accepted by the Colombian minister.

Salomón–Lozano Treaty

Once the negotiations were restarted, on March 24, 1922, a direct agreement was reached in Lima, the work of the plenipotentiaries Fabio Lozano Torrijos (representing Colombia) and Alberto Salomón Osorio (representing Peru). The Salomón-Lozano treaty established the following limit:

The rectification of the boundary between Peru and Brazil and the delivery of the strip of territory bordering Brazil, by the line agreed in 1851 with Peru, as well as Colombia's access to the Amazon, of which only Peru and Brazil were condominium owners, determined Brazil's opposition to the Salomón-Lozano treaty. This attitude delayed the approval of the agreement, until the signing of an act in Washington in 1925, by which Colombia recognized the territories ceded by Peru to Brazil in 1851. On December 20, 1927, it was approved by the Peruvian Congress, it would be ratified by the Colombian on March 17, 1928, and became effective on March 19, 1928. Finally, the treaty was consummated with the physical delivery of the territories on August 17, 1930.

In Peru, Leguía is still criticized for signing this treaty, considered excessively inconvenient, as it delivered over 300,000 km2, a considerable part occupied by Peruvian citizens, to Colombia. However, the intention of the Peruvian government was to gain an ally for Peru, when it was overwhelmed by the conflicts with Ecuador and

Once the negotiations were restarted, on March 24, 1922, a direct agreement was reached in Lima, the work of the plenipotentiaries Fabio Lozano Torrijos (representing Colombia) and Alberto Salomón Osorio (representing Peru). The Salomón-Lozano treaty established the following limit:

The rectification of the boundary between Peru and Brazil and the delivery of the strip of territory bordering Brazil, by the line agreed in 1851 with Peru, as well as Colombia's access to the Amazon, of which only Peru and Brazil were condominium owners, determined Brazil's opposition to the Salomón-Lozano treaty. This attitude delayed the approval of the agreement, until the signing of an act in Washington in 1925, by which Colombia recognized the territories ceded by Peru to Brazil in 1851. On December 20, 1927, it was approved by the Peruvian Congress, it would be ratified by the Colombian on March 17, 1928, and became effective on March 19, 1928. Finally, the treaty was consummated with the physical delivery of the territories on August 17, 1930.

In Peru, Leguía is still criticized for signing this treaty, considered excessively inconvenient, as it delivered over 300,000 km2, a considerable part occupied by Peruvian citizens, to Colombia. However, the intention of the Peruvian government was to gain an ally for Peru, when it was overwhelmed by the conflicts with Ecuador and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

. Indeed, one consequence of the treaty was that Colombia supported Peru in the Peruvian-Ecuadorian dispute and that Ecuador broke off its relations with Colombia.

Colombia–Peru War

The Colombia–Peru War was the result of dissatisfaction with the

The Colombia–Peru War was the result of dissatisfaction with the Salomón–Lozano Treaty

The Salomón–Lozano Treaty was signed in July 1922 by representatives Fabio Lozano Torrijos, of Colombia and Alberto Salomón Osorio of Peru. The fourth in a succession of treaties on the Colombian-Peruvian disputes over land in the upper Amazo ...

and the imposition of heavy tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and polic ...

on sugar. On August 27, 1932, Peruvian civilians Oscar Ordoñez and Juan La Rosa Guevara, in the presence of Lieutenant Colonel Isauro Calderón, Lieutenant Commander Hernán Tudela y Lavalle, engineers Oscar H. Ordóñez de la Haza and Luis A. Arana, doctors Guillermo Ponce de León, Ignacio Morey Peña, Pedro del Águila Hidalgo and Manuel I. Morey created the National Patriotic Junta ( es, Junta Patriótica Nacional), known also as the Patriotic Junta of Loreto ( es, Junta Patriótica de Loreto). They obtained, through donations and charity from civilians and the military, the necessary weapons and resources to start the “recovery of the port”.

The group released an irredentist manifesto known as the Leticia Plan ( es, Plan de Leticia) denouncing the Salomón-Lozano Treaty. The "plan" would be carried out peacefully and force would only be used if Colombia authorities responded in a hostile manner. Civilians would be the only ones participating so as not to compromise the entire country, which led to Juan La Rosa Guevara renouncing his appointment as second lieutenant in order to participate as a civilian.Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

. On 1 September 1932, President Luis Miguel Sánchez dispatched two regiments of the Peruvian Army

The Peruvian Army ( es, Ejército del Perú, abbreviated EP) is the branch of the Peruvian Armed Forces tasked with safeguarding the independence, sovereignty and integrity of national territory on land through military force. Additional missions ...

to Leticia and Tarapacá

San Lorenzo de Tarapacá, also known simply as Tarapacá, is a town in the region of the same name in Chile.

History

The town has likely been inhabited since the 12th century, when it formed part of the Inca trail. When Spanish explorer Diego d ...

; both settlements were in the Amazonas Department

Amazonas () is a department of Southern Colombia in the south of the country. It is the largest department in area while also having the 3rd smallest population. Its capital is Leticia and its name comes from the Amazon River, which drains t ...

, now in southern Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

. Those actions were then mostly ignored by the Colombian government

The Government of Colombia is a republic with separation of powers into executive, judicial and legislative branches.

Its legislature has a congress,

its judiciary has a supreme court, and

its executive branch has a president.

The citiz ...

.Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro

Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro (August 12, 1889 – April 30, 1933) was a high-ranking Peruvian army officer who served as the 41st President of Peru, from 1931 to 1933 as well as Interim President of Peru, officially as the President of the Pro ...

's assassination on the same year by an APRA APRA or Apra may refer to:

Places

*Apra, Punjab, a census town city in Jalandhar District of Punjab, India

* Apra Harbor, the main port of Guam

Acronyms

* American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana), a Peruvi ...

member.

Rio Protocol

The commission to settle the dispute over Leticia met in Rio de Janeiro in October 1933. The Peruvian side was made up of Víctor M. Maúrtua, Víctor Andrés Belaúnde

Víctor Andrés Belaúnde Diez Canseco (15 December 1883 – 14 December 1966) was a Peruvian diplomat, politician, philosopher and scholar. He chaired the 14th Session and the 4th Emergency Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly ...

, Alberto Ulloa Sotomayor, and Raúl Porras Barrenechea

Raúl Porras Barrenechea (23 March 1897 – 27 September 1960) was a Peruvian diplomat, historian and politician. He was President of the Senate in 1957 and Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1958 and 1960. A well-known figure of the student m ...

. The Colombian delegation, by Roberto Urdaneta Arbeláez

Roberto Urdaneta Arbeláez (27 June 1890 – 20 August 1972) was a Colombian Conservative party politician and lawyer who served as President of Colombia from November 1951 until June 1953, while President Laureano Gómez was absent due to healt ...

, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Luis Cano Villegas and Guillermo Valencia Castillo.

Peru invited Ecuador to begin negotiations in order to settle the question of pending limits between the two countries, which it refused. The country was an interested party in the dispute between Colombia and Peru, not only because of territorial contiguity, but also because there was an area that the three countries claimed. The Ecuadorian Congress declared that it would not recognize the validity of the arrangements between its two neighbors.

On May 24, 1934, the diplomatic representations of Colombia and Peru signed the Protocol of Rio de Janeiro, in the city of the same name, ratifying the Salomón-Lozano treaty, still in force today and accepted by both parties, and finally ending the territorial dispute.

See also

* Bolivian–Peruvian territorial dispute

*Chilean–Peruvian territorial dispute

The Chilean–Peruvian territorial dispute is a territorial dispute between Chile and Peru that started in the aftermath of the War of the Pacific and ended significantly in 1929 with the signing of the Treaty of Lima and in 2014 with a ruling by ...

*Ecuadorian–Peruvian territorial dispute

The Ecuadorian–Peruvian territorial dispute was a territorial dispute between Ecuador and Peru, which, until 1928, also included Colombia.Ecuador and Colombia signed the Muñoz Vernaza-Suárez Treaty in 1916, ending their dispute, while Peru an ...

*Colombia–Peru relations

Colombian–Peruvian relations is the relationship between two South American states, Colombia and Peru. Both nations are members of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, Lima Group, Organization of Ibero-American States, Organizat ...

* Dispute resolution

*Territorial dispute

A territorial dispute or boundary dispute is a disagreement over the possession or control of land between two or more political entities.

Context and definitions

Territorial disputes are often related to the possession of natural resources su ...

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

*

*

*

*

History of Peru

History of Colombia

Territorial disputes of Colombia

Territorial disputes of Peru

Colombia–Peru border

Colombia–Peru relations

Irredentism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Colombian-Peruvian territorial dispute

The formal independence of

The formal independence of  The Guayaquil issue was approached with care by both countries, who signed a treaty on July 6, 1822, allowing special privileges to citizens of both states. The issue, yet to be resolved, was postponed.

On September 1, 1823, Simón Bolívar arrived in

The Guayaquil issue was approached with care by both countries, who signed a treaty on July 6, 1822, allowing special privileges to citizens of both states. The issue, yet to be resolved, was postponed.

On September 1, 1823, Simón Bolívar arrived in  Then, two negotiations took place between both countries: between the Peruvian ministers Matías León and Agustín Guillermo Charún, and the Ecuadorians José Félix Valdivieso and Bernardo Daste, which failed. However, its importance lies in the fact that for the first time Peru based its rights over Maynas invoking the Royal Decree of 1802 (then lost) and the self-determination of peoples, as it would also do in future negotiations with Colombia.

Then, two negotiations took place between both countries: between the Peruvian ministers Matías León and Agustín Guillermo Charún, and the Ecuadorians José Félix Valdivieso and Bernardo Daste, which failed. However, its importance lies in the fact that for the first time Peru based its rights over Maynas invoking the Royal Decree of 1802 (then lost) and the self-determination of peoples, as it would also do in future negotiations with Colombia.

On October 26, 1858, the war between Peru and Ecuador began, because, according to the Peruvian plenipotentiary Juan Celestino Cavero, the Ecuadorian government decided to settle its foreign debt with

On October 26, 1858, the war between Peru and Ecuador began, because, according to the Peruvian plenipotentiary Juan Celestino Cavero, the Ecuadorian government decided to settle its foreign debt with

The Colombian government, on the occasion of the diplomatic efforts between Ecuador and Peru, requested to be admitted to the boundary discussions in order to reach a definitive agreement; such efforts culminated with the tripartite convention meeting in Lima on October 11, 1894. Aníbal Galindo, as special lawyer, and Luis Tanco, who was chargé d'affaires in Lima, were appointed as representatives for Colombia; for Ecuador, Julio Castro, extraordinary envoy and plenipotentiary minister of Ecuador in Lima; and for Peru, Luis Felipe Villarán, as special counsel. Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 40.

Upon entering the dispute, Colombia upheld the recognition of the ''uti possidetis'', but integrating and replacing it (in cases of obscurity and deficiency) with the principle of equity and reciprocal convenience. According to his thesis, the arbitrator should not only attend to the titles of law, but also the interests of the countries in dispute.

Colombia defined its position on the General Command of Maynas, which was disputed by the three countries. Peru maintained that, according to the ''uti possidetis'', the territory belonged to Peru, as mandated by the Royal Decree of 1802; while Ecuador had maintained its non-existence and, when the certificate was presented, its non-compliance. For its part, Colombia disputed the legal nature of the document, and argued that it was not a political or civil demarcation, but an ecclesiastical order. Thus, the intention of the royal act was to place the ecclesiastical missions in Maynas under the supervision of the

The Colombian government, on the occasion of the diplomatic efforts between Ecuador and Peru, requested to be admitted to the boundary discussions in order to reach a definitive agreement; such efforts culminated with the tripartite convention meeting in Lima on October 11, 1894. Aníbal Galindo, as special lawyer, and Luis Tanco, who was chargé d'affaires in Lima, were appointed as representatives for Colombia; for Ecuador, Julio Castro, extraordinary envoy and plenipotentiary minister of Ecuador in Lima; and for Peru, Luis Felipe Villarán, as special counsel. Porras Barrenechea 1926, p. 40.

Upon entering the dispute, Colombia upheld the recognition of the ''uti possidetis'', but integrating and replacing it (in cases of obscurity and deficiency) with the principle of equity and reciprocal convenience. According to his thesis, the arbitrator should not only attend to the titles of law, but also the interests of the countries in dispute.