The Cold War (1953–1962) refers to the period in the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

between the end of the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

in 1953 and the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

in 1962. It was marked by tensions and efforts at détente between the US and

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

After the death of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

in March 1953,

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

rose to power, initiating the policy of

De-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

which caused political unrest in the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

and

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

nations. Khrushchev's speech at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in 1956 shocked domestic and international audiences, by

denouncing Stalin’s personality cult and his regime's excesses.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

succeeded

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

as US President in 1953, but US foreign policy remained focused on containing Soviet influence.

John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American politician, lawyer, and diplomat who served as United States secretary of state under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his resignation in 1959. A member of the ...

, Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, advocated for a doctrine of

massive retaliation

Massive retaliation, also known as a massive response or massive deterrence, is a military doctrine and nuclear strategy in which a state commits itself to retaliate in much greater force in the event of an attack. It is associated with the U. ...

and

brinkmanship, whereby the US would threaten overwhelming nuclear force in response to Soviet aggression. This strategy aimed to avoid the high costs of conventional warfare by relying heavily on nuclear deterrence.

Despite temporary reductions in tensions, such as the

Austrian State Treaty

The Austrian State Treaty ( ) or Austrian Independence Treaty established Austria as a sovereign state. It was signed on 15 May 1955 in Vienna, at the Schloss Belvedere among the Allied occupying powers (France, the United Kingdom, the Uni ...

and the

1954 Geneva Conference

The Geneva Conference was intended to settle outstanding issues resulting from the Korean War and the First Indochina War and involved several nations. It took place in Geneva, Switzerland, from 26 April to 20 July 1954. The part of the confe ...

ending the

First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam, and alternatively internationally as the French-Indochina War) was fought between French Fourth Republic, France and Việ ...

, both superpowers continued their

arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more State (polity), states to have superior armed forces, concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

and extended their rivalry into space with the launch of

Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program ...

in 1957 by the Soviets. The

Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

and the nuclear arms buildup defined much of the competitive atmosphere during this period. The Cold War expanded to new regions, with the addition of

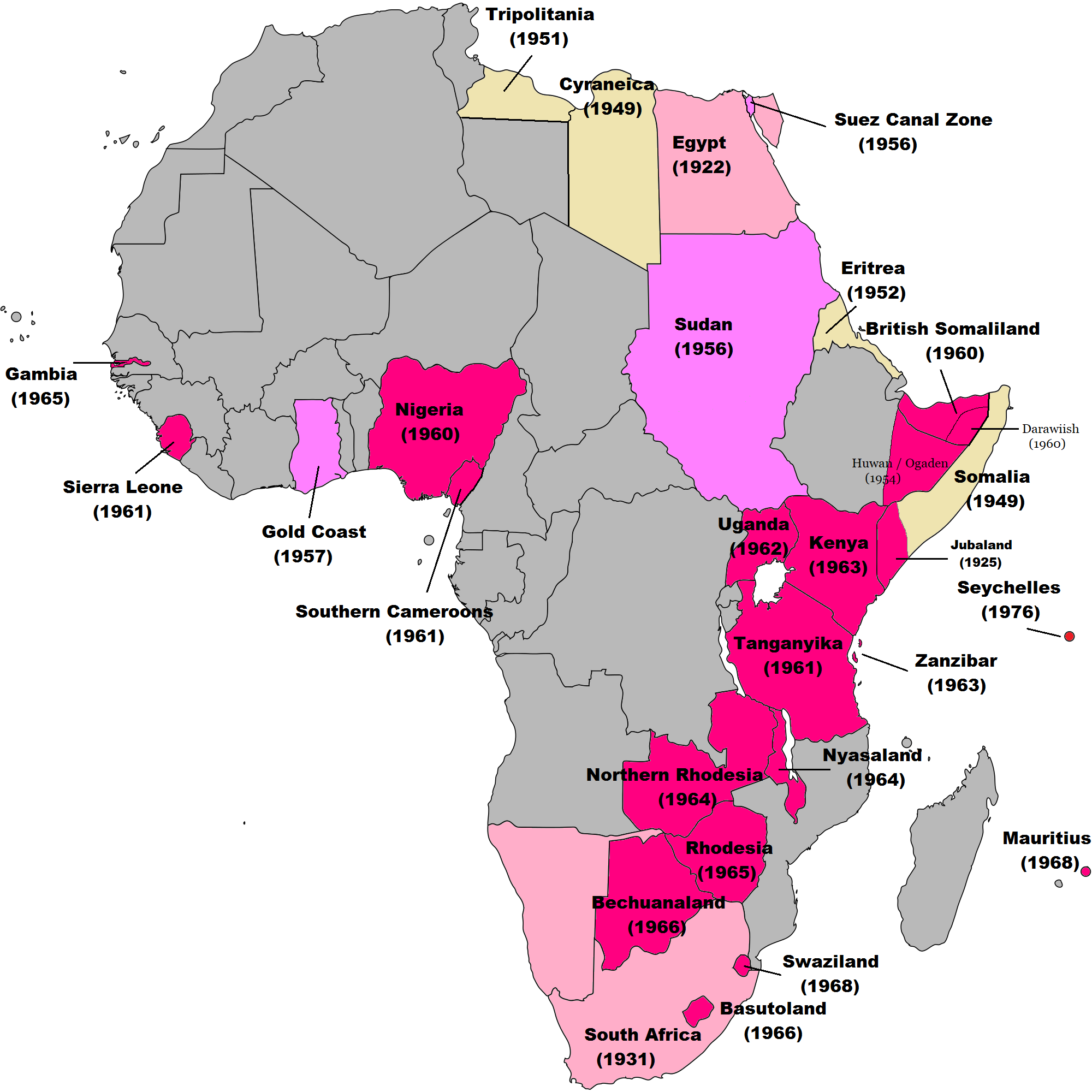

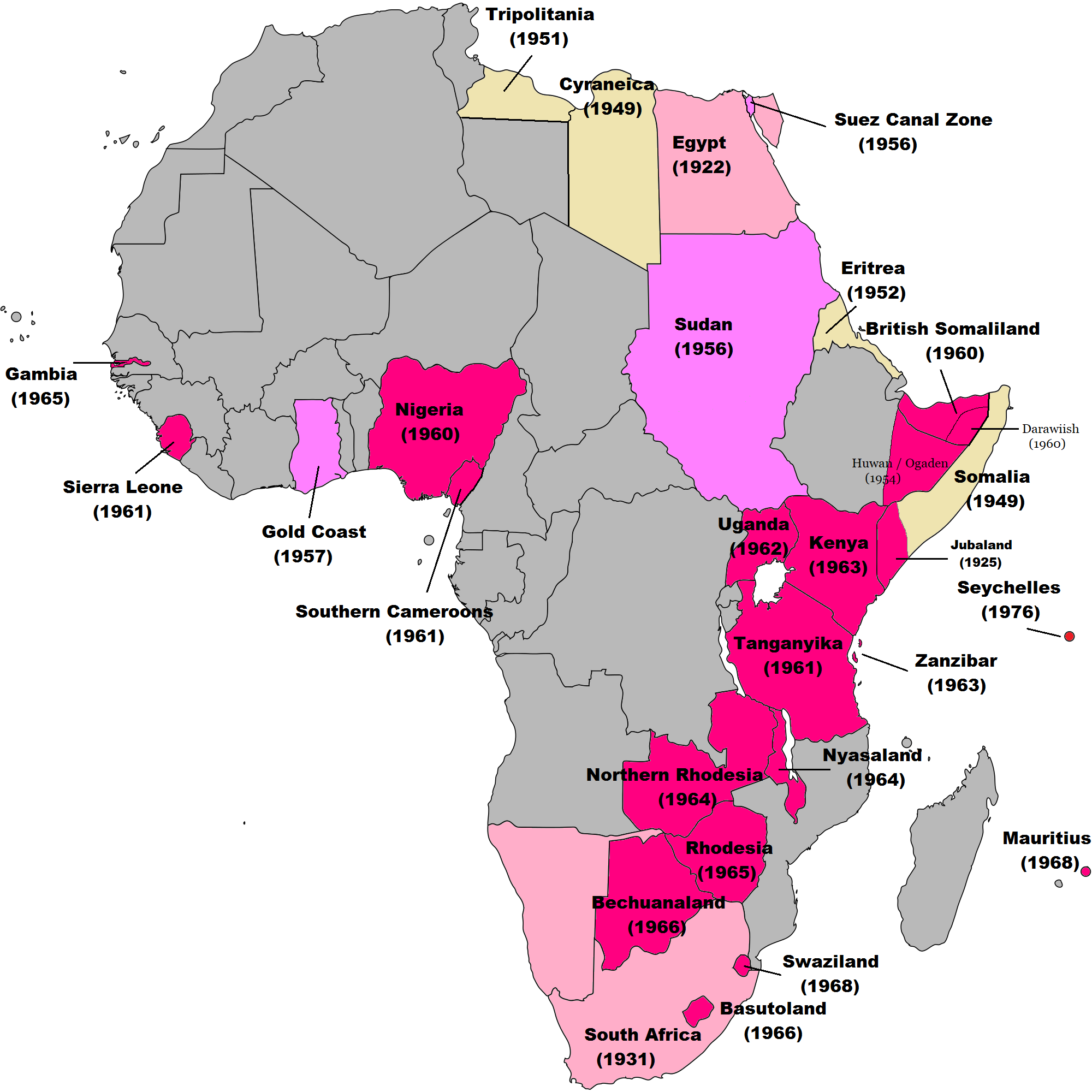

African decolonization movements. The

Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis () was a period of Crisis, political upheaval and war, conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost ...

in 1960 drew Cold War battle lines in Africa, as the

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Republic of the Congo), is a country in Central Africa. By land area, it is t ...

became a Soviet ally, causing concern in the West. However, by the early 1960s, the Cold War reached its most dangerous point with the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

in 1962, as the world stood on the brink of nuclear war.

Eisenhower and Khrushchev

When

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

was succeeded in office by

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

as the 34th

U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

in 1953, the

Democrats lost their two-decades-long control of the U.S. presidency. Under Eisenhower, however, the United States' Cold War policy remained essentially unchanged. Whilst a thorough rethinking of foreign policy was launched (known as "

Project Solarium"), the majority of emerging ideas (such as a "

rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, ...

of communism" and the liberation of Eastern Europe) were quickly regarded as unworkable. An underlying focus on the

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

of Soviet communism remained to inform the broad approach of U.S. foreign policy.

While the transition from the

Truman to the Eisenhower presidencies was a mild transition in character (from moderate to conservative), the change in the Soviet Union was immense. With the death of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

(who led the Soviet Union from 1928 and through the

Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

) in 1953,

Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov (8 January 1902 O.S. 26 December 1901">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 26 December 1901ref name=":6"> – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who br ...

was named leader of the Soviet Union. This was short lived however, as

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

soon undercut all of Malenkov's authority as

First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. was the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). From 1924 until the country's dissolution in 1991, the officeholder was the recognize ...

and took control of the Soviet Union himself. Malenkov joined a failed coup against Khrushchev in 1957, after which he was sent to

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

.

During a subsequent period of

collective leadership

In communist and socialist theory, collective leadership is a shared distribution of power within an organizational structure, sometimes publicly described or designed as Primus inter pares, ''primus inter pares'' (''first among equals'').

Commun ...

, Khrushchev gradually consolidated his hold on power. At

a speech to the closed session of the

Twentieth Party Congress of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

, February 25, 1956, First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev shocked his listeners by denouncing Stalin's

personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an ideali ...

and the multiple crimes that occurred under Stalin's leadership. Although the contents of the speech were secret, it was leaked to outsiders, thus shocking both Soviet allies and Western observers. Khrushchev was later named

premier of the Soviet Union

The Premier of the Soviet Union () was the head of government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). From 1923 to 1946, the name of the office was Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, and from 1946 to 1991 its name was ...

in March 1958.

The effect of this speech on Soviet politics was immense. With it Khrushchev stripped his remaining

Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

rivals of their legitimacy in a single stroke, dramatically boosting the First Party Secretary's domestic power. Khrushchev followed by easing restrictions, freeing some dissidents and initiating economic policies that emphasized commercial goods rather than just

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

and

steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

production.

U.S. strategy: "massive retaliation" and "brinksmanship"

Conflicting objectives

When Eisenhower entered office in 1953, he was committed to two possibly contradictory goals: maintaining—or even heightening—the national commitment to counter the spread of Soviet influence; and satisfying demands to balance the budget, lower taxes, and curb

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

. The most prominent of the doctrines to emerge from this goal was "massive retaliation", which Secretary of State

John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American politician, lawyer, and diplomat who served as United States secretary of state under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his resignation in 1959. A member of the ...

announced early in 1954. Eschewing the costly, conventional ground forces of the Truman administration, and wielding the vast superiority of the U.S.

nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

arsenal and covert intelligence, Dulles defined this approach as "

brinksmanship" in a January 16, 1956, interview with ''

Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

'': pushing the Soviet Union to the brink of war in order to exact concessions.

Eisenhower inherited from the Truman administration a military budget of roughly US$42 billion, as well as a paper (NSC-141) drafted by Acheson, Harriman, and Lovett calling for an additional $7–9 billion in military spending. With Treasury Secretary

George Humphrey leading the way, and reinforced by pressure from

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate majority le ...

and the cost-cutting mood of the

Republican Congress, the target for the new fiscal year (to take effect on July 1, 1954) was reduced to $36 billion. While the Korean armistice was on the verge of producing significant savings in troop deployment and money, the State and Defense Departments were still in an atmosphere of rising expectations for budgetary increases. Humphrey wanted a balanced budget and a tax cut in February 1955, and had a savings target of $12 billion (obtaining half of this from cuts in military expenditures).

Although unwilling to cut deeply into defense, the President also wanted a balanced budget and smaller defense allocations. "Unless we can put things in the hands of people who are starving to death we can never lick

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

", he told his cabinet. With this in mind, Eisenhower continued funding for America's innovative

cultural diplomacy

Cultural diplomacy is a type of soft power that includes the "exchange of ideas, information, art, language and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples in order to foster mutual understanding". The purpose of cultural diplomac ...

initiatives throughout Europe which included goodwill performances by the "soldier-musician ambassadors" of the

Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra.

[''The Juilliard Journal – Faculty Portrait'' Samuel Adler Biography - on journal.juilliard.edu](_blank)

/ref> Moreover, Eisenhower feared that a bloated "military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the Arms industry, defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving fac ...

" (a term he popularized) "would either drive U.S. to war—or into some form of dictatorial government" and perhaps even force the U.S. to "initiate war at the most propitious moment." On one occasion, the former commander of the greatest amphibious invasion force in history privately exclaimed, "God help the nation when it has a President who doesn't know as much about the military as I do."

In the meantime, however, attention was being diverted elsewhere in Asia. The continuing pressure from the "China lobby" or "Asia firsters", who had insisted on active efforts to restore Chiang Kai-shek to power was still a strong domestic influence on foreign policy. In April 1953 Senator Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate majority le ...

and other powerful Congressional Republicans suddenly called for the immediate replacement of the top chiefs of the Pentagon, particularly the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (12 February 1893 – 8 April 1981) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He wa ...

. To the so-called "China lobby" and Taft, Bradley was seen as having leanings toward a Europe-first orientation, meaning that he would be a possible barrier to new departures in military policy that they favored. Another factor was the vitriolic accusations of McCarthyism

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a Fear mongering, campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage i ...

, where large portions of the U.S. government allegedly contained covert communist agents or sympathizers. But after the mid-term elections in 1954–and censure by the Senate–the influence of Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

ebbed after his unpopular accusations against the Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

.

Eisenhower administration strategy

The administration attempted to reconcile the conflicting pressures from the "Asia firsters" and pressures to cut federal spending while continuing to fight the Cold War effectively. On May 8, 1953, the President and his top advisors tackled this problem in "Operation Solarium", named after the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

sunroom where the president conducted secret discussions. Although it was not traditional to ask military men to consider factors outside their professional discipline, the President instructed the group to strike a proper balance between his goals to cut government spending and an ideal military posture.

The group weighed three policy options for the next year's military budget: the Truman-Acheson approach of containment and reliance on conventional forces; threatening to respond to limited Soviet "aggression" in one location with nuclear weapons; and serious "liberation" based on an economic response to the Soviet political-military-ideological challenge to Western hegemony: propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

campaigns and psychological warfare

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), has been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations ( MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and Mi ...

. The third option was strongly rejected.

Eisenhower and the group (consisting of Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles ( ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was an American lawyer who was the first civilian director of central intelligence (DCI), and its longest serving director. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the ea ...

, Walter Bedell Smith

General (United States), General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forc ...

, C.D. Jackson, and Robert Cutler) instead opted for a combination of the first two, one that confirmed the validity of containment, but with reliance on the American air-nuclear deterrent. This was geared toward avoiding costly and unpopular ground wars, such as Korea.

The Eisenhower administration viewed atomic weapons as an integral part of U.S. defense, hoping that they would bolster the relative capabilities of the U.S. vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. The administration also reserved the prospects of using them, in effect, as a weapon of first resort, hoping to gain the initiative while reducing costs. By wielding the nation's nuclear superiority, the new Eisenhower-Dulles approach was a cheaper form of containment geared toward offering Americans "more bang for the buck".

Thus, the administration increased the number of nuclear warheads from 1,000 in 1953 to 18,000 by early 1961. Despite overwhelming U.S. superiority, one additional nuclear weapon was produced each day. The administration also exploited new technology. In 1955 the eight-engined B-52 Stratofortress

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic aircraft, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the ...

bomber, the first true jet bomber designed to carry nuclear weapons, was developed.

In 1961, the U.S. deployed 15 Jupiter IRBMs (intermediate-range ballistic missiles) at İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, aimed at the western USSR's cities, including Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

. Given its range, Moscow was only 16 minutes away. The U.S. could also launch -range Polaris

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinisation of names, Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an ...

SLBM

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which carries a nuclear warhead ...

s from submerged submarines.Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

the U.S. had 142 Atlas and 62 Titan I ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

s, mostly in hardened underground silos.

Fear of Soviet influence and nationalism

Allen Dulles, along with most U.S. foreign policy-makers of the era, considered a number of Third World nationalists and "revolutionaries" as being essentially under the influence, if not control, of the Warsaw Pact. Ironically, in ''War, Peace, and Change'' (1939), he had called Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

an "agrarian reformer", and during World War II he had deemed Mao's followers "the so called 'Red Army faction. But he no longer recognized indigenous roots in the Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

by 1950. In ''War or Peace'', an influential work denouncing the containment policies of the Truman administration, and espousing an active program of "liberation", he writes:

Thus the 450,000,000 people in China have fallen under leadership that is violently anti-American, and takes its inspiration and guidance from Moscow... Soviet Communist leadership has won a victory in China which surpassed what Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

was seeking and we risked war to avert.

Behind the scenes, Dulles could explain his policies in terms of geopolitics. But publicly, he used the moral and religious reasons that he believed Americans preferred to hear, even though he was often criticized by observers at home and overseas for his strong language.

Two of the leading figures of the interwar and early Cold War period who viewed international relations from a " realist" perspective, diplomat George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

and theologian Reinhold Niebuhr

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr (June 21, 1892 – June 1, 1971) was an American Reformed theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr was one of Ameri ...

, were troubled by Dulles' moralism and the method by which he analyzed Soviet behavior. Kennan disagreed with the notion that the Soviets even had a world design after Stalin's death, being far more concerned with maintaining control of their own bloc. However, the underlying assumptions of a monolithic world communism, directed from the Kremlin, of the Truman-Acheson containment after the drafting of NSC-68 were essentially compatible with those of the Eisenhower-Dulles foreign policy. The conclusions of Paul Nitze

Paul Henry Nitze (January 16, 1907 – October 19, 2004) was an American businessman and government official who served as United States Deputy Secretary of Defense, U.S. Secretary of the Navy, and Director of Policy Planning for the U.S. Sta ...

's National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

policy paper were as follows:

What is new, what makes the continuing crisis, is the polarization of power which inescapably confronts the slave society with the free... the Soviet Union, unlike previous aspirants to hegemony, is animated by a new fanatic faith, antithetical to our own, and seeks to impose its absolute authority... nthe Soviet Union and second in the area now under tscontrol... In the minds of the Soviet leaders, however, achievement of this design requires the dynamic extension of their authority... To that end Soviet efforts are now directed toward the domination of the Eurasian land mass.

The end of the Korean War

Prior to his election in 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

was already displeased with the manner that Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

had handled the war in Korea. After the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

secured a resolution from the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

to engage in military defense on behalf of South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

led by the president Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee (; 26 March 1875 – 19 July 1965), also known by his art name Unam (), was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960. Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisiona ...

, who had been invaded by North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

in an attempt to unify all of Korea under the communist North Korean regime led by the dictator Kim Il-sung

Kim Il Sung (born Kim Song Ju; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he led as its first supreme leader from its establishment in 1948 until his death in 1994. Afterwards, he was ...

. President Truman engaged U.S. land, air, and sea forces;United States presidential election

The election of the president of the United States, president and Vice President of the United States, vice president of the United States is an indirect election in which citizens of the United States who are Voter registration in the United ...

campaign, Eisenhower visited Korea on December 2, 1952, to assess to the situation. Eisenhower's investigation consisted of meeting with South Korean troops, commanders, and government officials, after his meetings Eisenhower concluded, "we could not stand forever on a static front and continue to accept casualties without any visible results. Small attacks on small hills would not end this war".Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee (; 26 March 1875 – 19 July 1965), also known by his art name Unam (), was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960. Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisiona ...

to compromise in order to speed up peace talks. This, coupled with the United States' threat of using nuclear weapons if the war did not end soon, led to the signing of an armistice on July 27, 1953. The armistice concluded the United States' initial Cold War concept of "limited war".Prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

were allowed to choose where they would stay, either the area that would become North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

or the area to become South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

, and a border was placed between the two territories in addition to an allotted demilitarized zone. The "police action" implemented by the Korean U.N. agreement prevented communism from spreading from North Korea to South Korea. United States involvement in the Korean War demonstrated its readiness to the world to rally to the aid of nations under invasion, particularly communistic invasion, and resulted in President Eisenhower's empowered image as an effective leader against tyranny; this ultimately led to a strengthened position of the United States in Europe and guided the development of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental transnational military alliance of 32 member states—30 European and 2 North American. Established in the aftermat ...

.NSC 68

United States Objectives and Programs for National Security, better known as NSC68, was a 66-page top secret U.S. National Security Council (NSC) policy paper drafted by the Department of State and Department of Defense and presented to President ...

.

Origins of the Space Race

The Space Race between the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

was an integral component of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. Contrary to the Nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

, it was a peaceful competition in which the two powers could demonstrate their technological and theoretical advancements over the other. The Soviet Union was the first nation to enter the space realm with their launch of Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program ...

on October 4, 1957. The satellite was merely an 83.6-kilogram aluminum alloy sphere, which was a major downsize from the original 1,000-kilogram design, that carried a radio and four antennas into space. This size was shocking to western scientists as America was designing a much smaller 8-kilogram satellite. This size discrepancy was apparent due to the gap in weapon technology as the United States was able to develop much smaller nuclear warheads than their Soviet counterparts. The Soviet Union later launched Sputnik 2

Sputnik 2 (, , ''Satellite 2'', or Prosteyshiy Sputnik 2 (PS-2, , ''Simplest Satellite 2'', launched on 3 November 1957, was the second spacecraft launched into Earth orbit, and the first to carry an animal into orbit, a Soviet space dog named ...

less than a month later.Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

responded by creating the President's Science Advisory Committee

The President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) was created on November 21, 1957, by President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower, as a direct response to the Soviet launching of the Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2 satellites. PSAC was an upgra ...

(PSAC). This committee was appointed to lead the United States in policy for scientific and defense strategies. Another United States response to the Soviets' successful satellite mission was a Navy led attempt to launch the first American satellite into space using its Vanguard TV3

Vanguard TV-3 (also called Vanguard Test Vehicle-Three), was the first attempt of the United States to launch a satellite into orbit around the Earth, after the successful Soviet launches of Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2. Vanguard TV-3 was a small s ...

missile.Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

appointed his President's Science Advisor, James Rhyne Killian

James Rhyne Killian Jr. (July 24, 1904 – January 29, 1988) was the 10th president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, from 1948 until 1959. He also held a number of government roles, such as Chair of the President's Intelligence A ...

, to consult with the PSAC to develop a solution.

Creation of NASA

In reaction to the launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union, the President's Science Advisory Committee advised President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

to convert National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency that was founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its ...

into a new organization that would be more progressive in the United States' efforts for space exploration and research.NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

). This agency would effectively shift the control of space research and travel from the military into the hands of NASA, which was to be a civilian-government administration.DARPA

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is a research and development agency of the United States Department of Defense responsible for the development of emerging technologies for use by the military. Originally known as the Adva ...

) was to be responsible for space travel and technology intended for military use.

On April 2, 1958, Eisenhower presented legislation to Congress to implement the creation of the National Aeronautics and Space Agency. Congress responded by supplementing the creation of NASA, with an additional committee to be called the National Aeronautics and Space Council

The National Space Council is a body within the Executive Office of the President of the United States created in 1989 during the George H. W. Bush administration, disbanded in 1993, and reestablished in June 2017 by the Donald Trump administrati ...

(NASC). The NASC would include the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, the head of the Atomic Energy Commission, and the administrator of NASA. Legislation was passed by Congress, and then signed by President Eisenhower on July 29, 1958. NASA began operations on October 1, 1958.

Kennedy's space administration

Since the conception of NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, there had been considerations about the possibility of flying a man to the Moon. On July 5, 1961, the "Research Steering Committee on Manned Spaceflight", led by George Low

George Michael Low (born Georg Michael Löw; June 10, 1926 – July 17, 1984) was an administrator at NASA and the 14th president of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Low was one of the senior NASA officials who made decisions as manager ...

presented the concept of the Apollo program

The Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo, was the United States human spaceflight program led by NASA, which Moon landing, landed the first humans on the Moon in 1969. Apollo followed Project Mercury that put the first Americans in sp ...

to the NASA "Space Exploration Council". Although under the Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

presidential administration NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

was given little authority to further explore space travel, it was proposed that after the crewed Earth-orbiting missions, Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

, that the government-civilian administration should make efforts to successfully complete a crewed lunar spaceflight mission. NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

administrator T. Keith Glennan

Thomas Keith Glennan (September 8, 1905 – April 11, 1995) was the first Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, serving from August 19, 1958 to January 20, 1961.

Early career

Born in Enderlin, North Dakota, the son ...

explained that President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, restricted any further space exploration beyond Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

. After John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

had been elected as president the previous November, policy for space exploration underwent a revolutionary change."This nation should commit itself to the achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth" -John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

After President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

made this proposal to Congress on May 25, 1961, he remained true to this commitment to send a crewed lunar spaceflight in the ensuing 30 months prior to his assassination. Directly after his proposal, there was an 89% increase in government funding for NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, followed by a 101% increase in funding the subsequent year.

The Soviet Union in the Space Race

In August 1957 the Soviet Union tested the world's first successful Intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

(ICBM), the R7 Semyorka. Within only two months of the launch of the Semyorka, Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program ...

became the first human made object in Earth's orbit. This was followed by the launch of Sputnik II which carried Laika

Laika ( ; , ; – 3 November 1957) was a Soviet space dog who was one of the first animals in space and the first to orbit the Earth. A stray mongrel from the streets of Moscow, she flew aboard the Sputnik 2 spacecraft, launched into lo ...

the first living space traveler though she did not survive the trip. This led to the creation of the Vostok programme

The Vostok programme ( ; rus, Восток, p=vɐˈstok, a=ru-восток.ogg, t=East) was a Soviet human spaceflight project to put the first Soviet cosmonauts into low Earth orbit and return them safely. Competing with the United States P ...

in 1960 and the first living creatures to survive the trip to space, Belka and Strelka the Soviet space dogs

During the 1950s and 1960s the Soviet space program used dogs for sub-orbital and Orbital spaceflight, orbital space flights to determine whether human spaceflight was feasible. The Soviet space program typically used female dogs due to the ...

. The Vostok Program was responsible for placing the first human in space, yet another task that the Soviet Union would complete before the United States.

The R7 ICBM

Prior to the start of the space race, the Soviet Union and the United States were struggling to build and obtain a missile that could not only carry nuclear cargo, but could also travel effectively from one country to another. These missiles, also known as ICBMs or Intercontinental Ballistic Missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

, were key for either country to gain a major strategical advantage in the early years of the Cold War. However, where the U.S. failed in their initial ICBM flight tests, the Soviets proved to be years ahead in ICBM technology with their R7 program. The R7 missile, first tested in October 1953, originally was designed to carry a nose cone plus nuclear cargo equal to 3 tons, maintain a flight range of 7000 to 8000 km, a launch weight of 170 tons, and a two-stage launch and flight system. However, during the initial testing, the R7 ICBM proved too small for the required cargo and major changes were approved and implemented in May 1954. These changes consisted of a heavier nose that could carry 3 tons of nuclear payload and a design change that would allow for a controlled take off and flight due to the new launch weight being 280 tons. This rocket proved effective in testing in May 1957 and was then slightly adjusted to support space flight.

Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union successfully launched the first Earth satellite into space. Sputnik 1's official mission was to send back data from space, however the effects of this launch were monumental for both the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. For both countries, the launch of Sputnik 1 sparked the start of the Timeline of the Space Race. It created a curiosity for space flight and a relatively peaceful competition to the Moon. However the initial effects of Sputnik 1 for the United States was not a matter of exploration, but a matter of national security. What the USSR proved to the world, and mainly the United States, was that they were capable of launching a missile into space and potentially an ICBM carrying nuclear cargo at the United States. The fear of the unknown capability of Sputnik sparked fear in the Americans and a number of government officials went on record giving their thoughts on the matter. Senator Jackson of Seattle said the launch of Sputnik "was a devastating blow", and that " residentEisenhower should declare a week of shame and danger". For the Russians' the launch of Sputnik 1 proved to be a major advantage in the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, because it secured their current leading position in the war, created a retaliation force in the event of a U.S. nuclear strike, and allowed for a competitive advantage in ICBM technology.

Sputnik 2

Sputnik 2 (, , ''Satellite 2'', or Prosteyshiy Sputnik 2 (PS-2, , ''Simplest Satellite 2'', launched on 3 November 1957, was the second spacecraft launched into Earth orbit, and the first to carry an animal into orbit, a Soviet space dog named ...

launched almost a month later on November 3, 1957, with a mission goal of carrying the first dog, Laika

Laika ( ; , ; – 3 November 1957) was a Soviet space dog who was one of the first animals in space and the first to orbit the Earth. A stray mongrel from the streets of Moscow, she flew aboard the Sputnik 2 spacecraft, launched into lo ...

, into Earth orbit. This mission, though unsuccessful in the sense that Laika did not survive the mission, further established the USSR's position in the Cold War. Not only were the Soviets capable of launching a missile into space, but they could continue to complete successful space launches before the United States could complete one launch.

Lunar missions

The USSR launched three Lunar missions in 1959. The Lunar missions were the Russian equivalent to the United States Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

and Project Gemini

Project Gemini () was the second United States human spaceflight program to fly. Conducted after the first American crewed space program, Project Mercury, while the Apollo program was still in early development, Gemini was conceived in 1961 and ...

space programs, whose primary mission was to prepare to put the first human on the Moon.Luna 1

''Luna 1'', also known as ''Mechta'' ( , ''Literal translation, lit.'': ''Dream''), ''E-1 No.4'' and ''First Lunar Rover'', was the first spacecraft to reach the vicinity of Earth's Moon, the first spacecraft to leave Earth's orbit, and the fi ...

, which launched on January 2, 1959. Its successful mission established the first rocket engine restart within Earth orbit and the first man-made object to establish heliocentric orbit

A heliocentric orbit (also called circumsolar orbit) is an orbit around the barycenter of the Solar System, which is usually located within or very near the surface of the Sun. All planets, comets, and asteroids in the Solar System, and the Sun ...

. Luna 2

''Luna 2'' (), originally named the Second Soviet Cosmic Rocket and nicknamed Lunik 2 in contemporaneous media, was the sixth of the Soviet Union's Luna programme spacecraft launched to the Moon, E-1 No.7. It was the first spacecraft Moon landi ...

, which launched on September 14, 1959, established the first impact into another celestial body (the Moon). Finally, Luna 3

Luna 3, or E-2A No.1 (), was a Soviet spacecraft launched in 1959 as part of the Luna programme. It was the first mission to photograph the far side of the Moon and the third Soviet space probe to be sent to the neighborhood of the Moon. The hi ...

launched on October 7, 1959, and took the first pictures of the dark side of the Moon. After these three missions in 1959, the Soviets continued their exploration of the Moon and its environment in 21 other Luna missions.

Soviet space travel from 1960–1962

The Luna ("Moon") program was a giant step forward for the Soviets in achieving the goal of putting the first man on the Moon. It also "planted the building blocks" of a program for the Soviets to "sustain human beings safely and productively in low Earth orbit" with the creation of the Soviet "equivalent to the Apollo command module, the Soyuz

Soyuz is a transliteration of the Cyrillic text Союз (Russian language, Russian and Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, 'Union'). It can refer to any union, such as a trade union (''profsoyuz'') or the Soviet Union, Union of Soviet Socialist Republi ...

space capsule".cosmonauts

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spacecraft. Although generally reserve ...

on May 15, 1960. However, on May 19, "an attempt to deorbit a space cabin failed" and sent the cabin into high Earth orbit, only for it to crash into the Earth in September of the same year. The Soviets continued their space program, however by launching Sputnik 5

Korabl-Sputnik 2 (), also known as Sputnik 5 in the West, was a Soviet artificial satellite, and the third test flight of the Vostok spacecraft. It was the first spaceflight to send animals into orbit and return them safely back to Earth, incl ...

on August 19, 1960, which carried the first animals and plants to space and return them safely to Earth.

Other notable launches include:

* Vostok 1

Vostok 1 (, ) was the first spaceflight of the Vostok programme and the first human spaceflight, human orbital spaceflight in history. The Vostok 3KA space capsule was launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome on 12 April 1961, with Soviet astronaut, c ...

: Launched on April 12, 1961. Successfully carried the first human into space, Yuri Gagarin

Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin; Gagarin's first name is sometimes transliterated as ''Yuriy'', ''Youri'', or ''Yury''. (9 March 1934 – 27 March 1968) was a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful Human spaceflight, crewed sp ...

, and completed the first crewed orbital flight.

* Vostok 2: Launched August 6, 1961. Successfully carried the first crewed mission lasting one day carrying Gherman Titov.

* Vostok 3 and Vostok 4

Vostok 3 () and Vostok 4 (, 'Orient 4' or 'East 4') were Soviet space program flights in August 1962, intended to determine the Effect of spaceflight on the human body, ability of the human body to function in conditions of weightlessness, test ...

: Launched August 12, 1962. Vostok 3 carried Andriyan Nikolayev

Andriyan Grigoryevich Nikolayev ( Chuvash and ; 5 September 1929 – 3 July 2004) was a Soviet cosmonaut. In 1962, aboard Vostok 3, he became the third Soviet cosmonaut to fly into space. Nikolayev was an ethnic Chuvash and because of it con ...

and Vostok 4 carried Pavel Popovich

Pavel Romanovich Popovich (; ; 5 October 1930 – 29 September 2009) was a Soviet Union, Soviet cosmonaut.

Popovich was the fourth cosmonaut in space, the sixth person in orbit, the eighth person and first Ukrainians, Ukrainian in space.

Bio ...

. Successfully completed the first dual crewed space flight, the first ship-to-ship radio contact and first simultaneous flight of crewed spacecraft.

The race continues

The Soviet Union continued to extend its lead in the space race with its mission on April 12, 1961, which made Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin

Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin; Gagarin's first name is sometimes transliterated as ''Yuriy'', ''Youri'', or ''Yury''. (9 March 1934 – 27 March 1968) was a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful Human spaceflight, crewed sp ...

the first human being to leave Earth's atmosphere and enter space. The United States gained some ground a month later, on May 15, 1961, when they sent Alan Shepard

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr. (November 18, 1923 – July 21, 1998) was an American astronaut. In 1961, he became the second person and the first American to travel into space and, in 1971, he became the List of Apollo astronauts#Apollo astr ...

on a fifteen-minute flight outside of Earth's atmosphere during the '' Freedom 7'' project. On February 20, 1962, America made further progress as John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth in his Mercury mission ''Friendship 7

Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) was the first crewed American orbital spaceflight, which took place on February 20, 1962. Piloted by astronaut John Glenn and operated by NASA as part of Project Mercury, it was the fifth human spaceflight, preceded by Sov ...

''.

Soviet strategy

In 1960 and 1961, Khrushchev tried to impose the concept of nuclear deterrence on the military. Nuclear deterrence holds that the reason for having nuclear weapons is to discourage their use by a potential enemy, with each side deterred from war because of the threat of its escalation into a nuclear conflict, Khrushchev believed, "peaceful coexistence" with capitalism would become permanent and allow the inherent superiority of socialism to emerge in economic and cultural competition with the West.

Khrushchev hoped that exclusive reliance on the nuclear firepower of the newly created Strategic Rocket Forces

The Strategic Rocket Forces of the Russian Federation or the Strategic Missile Forces of the Russian Federation (RVSN RF; ) is a military branch, separate combat arm of the Russian Armed Forces that controls Russia's land-based intercontinenta ...

would remove the need for increased defense expenditures. He also sought to use nuclear deterrence to justify his massive troop cuts; his downgrading of the Ground Forces, traditionally the "fighting arm" of the Soviet armed forces; and his plans to replace bombers with missiles and the surface fleet with nuclear missile submarines.Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

the USSR had only four R-7 Semyorka

The R-7 Semyorka (, GRAU index: 8K71) was a Soviet Union, Soviet missile developed during the Cold War, and the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile. The R-7 made 28 launches between 1957 and 1961. A derivative, the R-7A Semyorka, R ...

s and a few R-16s intercontinental missiles deployed in vulnerable surface launchers.

Mutual assured destruction

An important part of developing stability was based on the concept of Mutual assured destruction (MAD). While the Soviets acquired atomic weapons in 1949, it took years for them to reach parity with the United States. In the meantime, the Americans developed the

An important part of developing stability was based on the concept of Mutual assured destruction (MAD). While the Soviets acquired atomic weapons in 1949, it took years for them to reach parity with the United States. In the meantime, the Americans developed the hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

, which the Soviets matched during the era of Khrushchev. New methods of delivery such as Submarine-launched ballistic missile

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from Ballistic missile submarine, submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which ...

s and Intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

s with MIRV

A multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) is an exoatmospheric ballistic missile payload containing several warheads, each capable of being aimed to hit a different target. The concept is almost invariably associated with i ...

warheads meant that both superpowers could easily devastate the other, even after attack by an enemy.

This fact often made leaders on both sides extremely reluctant to take risks, fearing that some small flare-up could ignite a war that would wipe out all of human civilization. Nonetheless, leaders of both nations pressed on with military and espionage plans to prevail over the other side. At the same time, different avenues were pursued to try to advance their causes; these began to encompass athletics

Athletics may refer to:

Sports

* Sport of athletics, a collection of sporting events that involve competitive running, jumping, throwing, and walking

** Track and field, a sub-category of the above sport

* Athletics (physical culture), competitio ...

(with the Olympics

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a variety of competit ...

becoming a battleground between ideologies as well as athletes) and culture (with respective countries supporting pianist

A pianist ( , ) is a musician who plays the piano. A pianist's repertoire may include music from a diverse variety of styles, such as traditional classical music, jazz piano, jazz, blues piano, blues, and popular music, including rock music, ...

s, chess

Chess is a board game for two players. It is an abstract strategy game that involves Perfect information, no hidden information and no elements of game of chance, chance. It is played on a square chessboard, board consisting of 64 squares arran ...

players, and movie directors).

One of the most important forms of nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

competition was the space race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

. The Soviets jumped out to an early lead in 1957 with the launching of Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space progra ...

, the first artificial satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scienti ...

, followed by the first crewed flight. The success of the Soviet space program

The Soviet space program () was the state space program of the Soviet Union, active from 1951 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Contrary to its competitors (NASA in the United States, the European Space Agency in Western Euro ...

was a great shock to the United States, which had believed itself to be ahead technologically. The ability to launch objects into orbit was especially ominous because it showed Soviet missiles could target anywhere on the planet.

Soon the Americans had a space program of their own but remained behind the Soviets until the mid-1960s. American President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

launched an unprecedented effort, promising that by the end of the 1960s Americans would land a man on the Moon, which they did, thus beating the Soviets to one of the more important objectives in the space race.

Another alternative to outright battle was the shadow war that was taking place in the world of espionage. There was a series of shocking spy scandals in the west, most notably that involving the Cambridge Five

The Cambridge Five was a ring of spies in the United Kingdom that passed information to the Soviet Union during the Second World War and the Cold War and was active from the 1930s until at least the early 1950s. None of the known members were e ...

. The Soviets had several high-profile defections to the west, such as the Petrov Affair. Funding for the KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

, CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

, MI6

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

and smaller organizations such as the Stasi

The Ministry for State Security (, ; abbreviated MfS), commonly known as the (, an abbreviation of ), was the Intelligence agency, state security service and secret police of East Germany from 1950 to 1990. It was one of the most repressive pol ...

increased greatly as their agents and influence spread around the world.

In 1957 the CIA started the program of reconnaissance flights over the USSR using Lockheed U-2

The Lockheed U-2, nicknamed the "''Dragon Lady''", is an American single-engine, high–altitude reconnaissance aircraft operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) since the 1950s. Designed for all- ...

spy planes. When such a plane was brought down over the Soviet Union on May 1, 1960 (1960 U-2 incident

On 1 May 1960, a United States Lockheed U-2, U-2 reconnaissance aircraft, spy plane was shot down by the Soviet Air Defence Forces while conducting photographic aerial reconnaissance inside Soviet Union, Soviet territory. Flown by American pil ...

) at first the United States government denied the plane's purpose and mission, but was forced to admit its role as a surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing, or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as ...

aircraft when the Soviet government revealed that it had captured the pilot, Gary Powers, alive and was in possession of its largely intact remains. Coming just over two weeks before a scheduled East-West Summit in Paris, the incident caused a collapse in the talks and a marked deterioration in relations.

Eastern Bloc events

As the Cold War became an accepted element of the international system, the battlegrounds of the earlier period began to stabilize. A ''de facto'' buffer zone

A buffer zone, also historically known as a march, is a neutral area that lies between two or more bodies of land; usually, between countries. Depending on the type of buffer zone, it may serve to separate regions or conjoin them.

Common types o ...

between the two camps was set up in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

. In the south, Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

became heavily allied with the other European communist states. Meanwhile, Austria had become neutral.

1953 East Germany uprising

Following large numbers of East Germans traveling west through the only "loophole" left in the Eastern Bloc emigration restrictions, the Berlin sector border,East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

into a satellite state of the Soviet Union. Already disaffected East Germans, who could see the relative economic successes of West Germany within Berlin, became enraged,Soviet Army

The Soviet Ground Forces () was the land warfare service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces from 1946 to 1992. It was preceded by the Red Army.

After the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991, the Ground Forces remained under th ...

intervened.

Creation of the Warsaw Pact

In 1955, the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

was formed partly in response to NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

's inclusion of West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

and partly because the Soviets needed an excuse to retain Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

units in potentially problematic Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

.

1956 Polish protests

After the death of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the communist regime in Poland relaxed some of its policies. This led to a desire within the Polish public for more radical reforms of this kind, though the majority of Polish officials did not share this desire and were hesitant to reform. This caused impatience among industrial workers who began to strike; demanding better wages, lower work quotas, and cheaper food. 30,000 demonstrators carried banners demanding "Bread and Freedom". Władysław Gomułka