Claude Bernard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

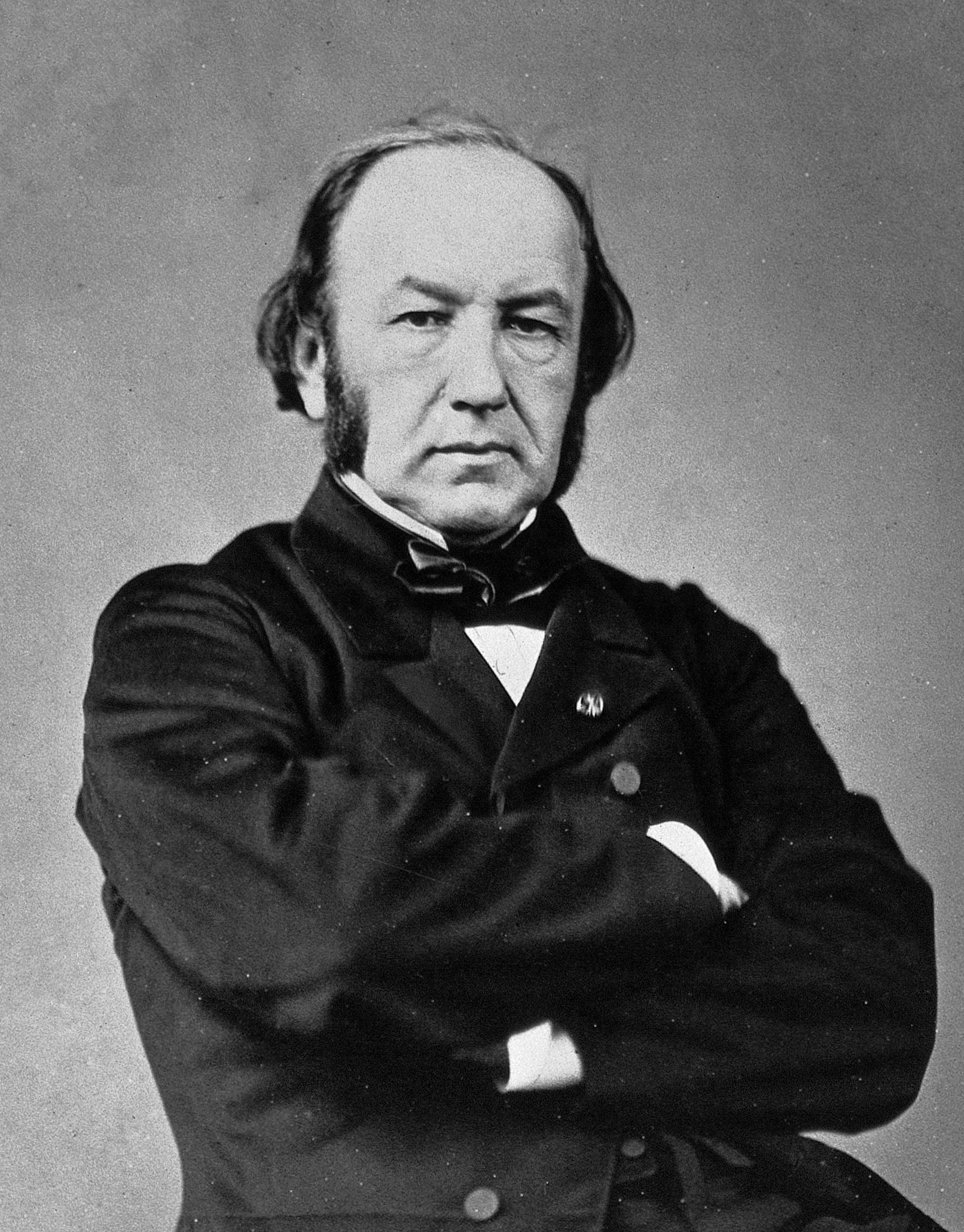

Claude Bernard (; 12 July 1813 – 10 February 1878) was a

Patron Claude Bernard's aim, as he stated in his own words, was to establish the use of the

Patron Claude Bernard's aim, as he stated in his own words, was to establish the use of the

In his major discourse on the scientific method, ''An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine'' (1865), Bernard described what makes a scientific theory good and what makes a scientist important, a true discoverer. Unlike many scientific writers of his time, Bernard wrote about his own experiments and thoughts, and used the first person.

''Known and Unknown''. What makes a scientist important, he states, is how well he or she has penetrated into the unknown. In areas of science where the facts are known to everyone, all scientists are more or less equal—we cannot know who is great. But in the area of science that is still obscure and unknown the great are recognized: "They are marked by ideas which light up phenomena hitherto obscure and carry science forward."

''Authority vs. Observation''. It is through the experimental method that science is carried forward—not through uncritically accepting the authority of academic or scholastic sources. In the experimental method, observable reality is our only authority. Bernard writes with scientific fervor:

:When we meet a fact which contradicts a prevailing theory, we must accept the fact and abandon the theory, even when the theory is supported by great names and generally accepted.

''Induction and Deduction''. Experimental science is a constant interchange between theory and fact, induction and deduction. Induction, reasoning from the particular to the general, and deduction, or reasoning from the general to the particular, are never truly separate. A general theory and our theoretical deductions from it must be tested with specific experiments designed to confirm or deny their truth; while these particular experiments may lead us to formulate new theories.

''Cause and Effect''. The scientist tries to determine the relation of cause and effect. This is true for all sciences: the goal is to connect a "natural phenomenon" with its "immediate cause". We formulate hypotheses elucidating, as we see it, the relation of cause and effect for particular phenomena. We test the hypotheses. And when an hypothesis is proved, it is a scientific theory. "Before that we have only groping and empiricism."

''Verification and Disproof''. Bernard explains what makes a theory good or bad scientifically:

:Theories are only hypotheses, verified by more or less numerous facts. Those verified by the most facts are the best, but even then they are never final, never to be absolutely believed.

In his major discourse on the scientific method, ''An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine'' (1865), Bernard described what makes a scientific theory good and what makes a scientist important, a true discoverer. Unlike many scientific writers of his time, Bernard wrote about his own experiments and thoughts, and used the first person.

''Known and Unknown''. What makes a scientist important, he states, is how well he or she has penetrated into the unknown. In areas of science where the facts are known to everyone, all scientists are more or less equal—we cannot know who is great. But in the area of science that is still obscure and unknown the great are recognized: "They are marked by ideas which light up phenomena hitherto obscure and carry science forward."

''Authority vs. Observation''. It is through the experimental method that science is carried forward—not through uncritically accepting the authority of academic or scholastic sources. In the experimental method, observable reality is our only authority. Bernard writes with scientific fervor:

:When we meet a fact which contradicts a prevailing theory, we must accept the fact and abandon the theory, even when the theory is supported by great names and generally accepted.

''Induction and Deduction''. Experimental science is a constant interchange between theory and fact, induction and deduction. Induction, reasoning from the particular to the general, and deduction, or reasoning from the general to the particular, are never truly separate. A general theory and our theoretical deductions from it must be tested with specific experiments designed to confirm or deny their truth; while these particular experiments may lead us to formulate new theories.

''Cause and Effect''. The scientist tries to determine the relation of cause and effect. This is true for all sciences: the goal is to connect a "natural phenomenon" with its "immediate cause". We formulate hypotheses elucidating, as we see it, the relation of cause and effect for particular phenomena. We test the hypotheses. And when an hypothesis is proved, it is a scientific theory. "Before that we have only groping and empiricism."

''Verification and Disproof''. Bernard explains what makes a theory good or bad scientifically:

:Theories are only hypotheses, verified by more or less numerous facts. Those verified by the most facts are the best, but even then they are never final, never to be absolutely believed.

When have we verified that we have found a cause? Bernard states:

:Indeed, proof that a given condition always precedes or accompanies a phenomenon does not warrant concluding with certainty that a given condition is the immediate cause of that phenomenon. It must still be established that when this condition is removed, the phenomenon will no longer appear…

We must always try to disprove our own theories. "We can solidly settle our ideas only by trying to destroy our own conclusions by counter-experiments." What is observably true is the only authority. If through experiment, you contradict your own conclusions—you must accept the contradiction—but only on one condition: that the contradiction is PROVED.

''Determinism and Averages''. In the study of disease, "the real and effective cause of a disease must be constant and determined, that is, unique; anything else would be a denial of science in medicine." In fact, a "very frequent application of mathematics to biology sthe use of averages"—that is, statistics—which may give only "apparent accuracy". Sometimes averages do not give the kind of information needed to save lives. For example:

:A great surgeon performs operations for stone by a single method; later he makes a statistical summary of deaths and recoveries, and he concludes from these statistics that the mortality law for this operation is two out of five. Well, I say that this ratio means literally nothing scientifically and gives us no certainty in performing the next operation; for we do not know whether the next case will be among the recoveries or the deaths. What really should be done, instead of gathering facts empirically, is to study them more accurately, each in its special determinism….to discover in them the cause of mortal accidents so as to master the cause and avoid the accidents.

Although the application of mathematics to every aspect of science is its ultimate goal, biology is still too complex and poorly understood. Therefore, for now the goal of medical science should be to discover all the new facts possible. Qualitative analysis must always precede quantitative analysis.

''Truth vs. Falsification''. The "philosophic spirit", writes Bernard, is always active in its desire for truth. It stimulates a "kind of thirst for the unknown" which ennobles and enlivens science—where, as experimenters, we need "only to stand face to face with nature". The minds that are great "are never self-satisfied, but still continue to strive." Among the great minds he names

When have we verified that we have found a cause? Bernard states:

:Indeed, proof that a given condition always precedes or accompanies a phenomenon does not warrant concluding with certainty that a given condition is the immediate cause of that phenomenon. It must still be established that when this condition is removed, the phenomenon will no longer appear…

We must always try to disprove our own theories. "We can solidly settle our ideas only by trying to destroy our own conclusions by counter-experiments." What is observably true is the only authority. If through experiment, you contradict your own conclusions—you must accept the contradiction—but only on one condition: that the contradiction is PROVED.

''Determinism and Averages''. In the study of disease, "the real and effective cause of a disease must be constant and determined, that is, unique; anything else would be a denial of science in medicine." In fact, a "very frequent application of mathematics to biology sthe use of averages"—that is, statistics—which may give only "apparent accuracy". Sometimes averages do not give the kind of information needed to save lives. For example:

:A great surgeon performs operations for stone by a single method; later he makes a statistical summary of deaths and recoveries, and he concludes from these statistics that the mortality law for this operation is two out of five. Well, I say that this ratio means literally nothing scientifically and gives us no certainty in performing the next operation; for we do not know whether the next case will be among the recoveries or the deaths. What really should be done, instead of gathering facts empirically, is to study them more accurately, each in its special determinism….to discover in them the cause of mortal accidents so as to master the cause and avoid the accidents.

Although the application of mathematics to every aspect of science is its ultimate goal, biology is still too complex and poorly understood. Therefore, for now the goal of medical science should be to discover all the new facts possible. Qualitative analysis must always precede quantitative analysis.

''Truth vs. Falsification''. The "philosophic spirit", writes Bernard, is always active in its desire for truth. It stimulates a "kind of thirst for the unknown" which ennobles and enlivens science—where, as experimenters, we need "only to stand face to face with nature". The minds that are great "are never self-satisfied, but still continue to strive." Among the great minds he names

Biography, bibliography, and links on digitized sources

in the Virtual Laboratory of the

'Claude Bernard': detailed biography and a comprehensive bibliography linked to complete on-line texts, quotations, images and more.

*

Biography and genealogy of Claude Bernard

*

Claude Bernard's works

digitized by th

BIUM (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Paris)

see its digital librar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bernard, Claude 1813 births 1878 deaths People from Rhône (department) Collège de France faculty French Roman Catholics French physiologists French medical writers Members of the Académie Française Members of the French Academy of Sciences Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Recipients of the Copley Medal Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters École pratique des hautes études faculty Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences University of Paris faculty Foreign Members of the Royal Society

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

physiologist. Historian I. Bernard Cohen

I. Bernard Cohen (1 March 1914 – 20 June 2003) was the Victor S. Thomas Professor of the history of science at Harvard University and the author of many books on the history of science and, in particular, Isaac Newton and Benjamin Franklin. ...

of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

called Bernard "one of the greatest of all men of science". He originated the term '' milieu intérieur'', and the associated concept of homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British English, British also homoeostasis) Help:IPA/English, (/hɒmɪə(ʊ)ˈsteɪsɪs/) is the state of steady internal, physics, physical, and chemistry, chemical conditions maintained by organism, living systems. Thi ...

(the latter term being coined by Walter Cannon

Walter Bradford Cannon (October 19, 1871 – October 1, 1945) was an American physiologist, professor and chairman of the Department of Physiology at Harvard Medical School. He coined the term " fight or flight response", and developed the theor ...

).

Life and career

Bernard was born in 1813 in the village of Saint-Julien nearVillefranche-sur-Saône

Villefranche-sur-Saône (, ; frp, Velafranche) is a commune in the Rhône department in eastern France.

It lies 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the river Saône, and is around north of Lyon. The inhabitants of the town are called ''Caladois''.

...

. He received his early education in the Jesuit school of that town, and then proceeded to the college at Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

, which, however, he soon left to become assistant in a druggist's shop. He is sometimes described as an agnostic and even humorously referred to by his colleagues as a "great priest of atheism". Despite this, after his death Cardinal Ferdinand Donnet claimed Bernard was a fervent Catholic, with a biographical entry in the ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. His leisure hours were devoted to the composition of a vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic compositio ...

comedy, and the success it achieved moved him to attempt a prose drama in five acts, ''Arthur de Bretagne''.

In 1834, at the age of twenty-one, he went to Paris, armed with this play and an introduction to Saint-Marc Girardin

Saint-Marc Girardin (22 February 1801 – 1 April 1873) was a French politician and man of letters, whose real name was Marc Girardin.

Biography

Girardin was born in Paris. After a brilliant university career in the city, he began in 1828 to cont ...

, but the critic dissuaded him from adopting literature as a profession, and urged him rather to take up the study of medicine. This advice Bernard followed, and in due course he became ''interne'' at the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris In French-speaking countries, a hôtel-Dieu ( en, hostel of God) was originally a hospital for the poor and needy, run by the Catholic Church. Nowadays these buildings or institutions have either kept their function as a hospital, the one in Paris b ...

. In this way he was brought into contact with the great physiologist, François Magendie

__NOTOC__

François Magendie (6 October 1783 – 7 October 1855) was a French physiologist, considered a pioneer of experimental physiology. He is known for describing the foramen of Magendie. There is also a ''Magendie sign'', a downward a ...

, who served as physician at the hospital. Bernard became 'preparateur' (lab assistant) at the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris ...

in 1841.

In 1845, Bernard married Marie Françoise "Fanny" Martin for convenience; the marriage was arranged by a colleague and her dowry helped finance his experiments. In 1847 he was appointed Magendie's deputy-professor at the college, and in 1855 he succeeded him as full professor. In 1860, Bernard was elected an international member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communi ...

. His field of research was considered inferior at the time, the laboratory assigned to him was simply a "regular cellar." Some time previously Bernard had been chosen the first occupant of the newly instituted chair of physiology at the Sorbonne, but no laboratory was provided for his use. It was Louis Napoleon

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

who, after an interview with him in 1864, repaired the deficiency, building a laboratory at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loca ...

in the Jardin des Plantes. At the same time, Napoleon III established a professorship which Bernard accepted, leaving the Sorbonne.

In the same year, 1868, he was also admitted a member of the ''Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

'' and elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

When he died on 10 February 1878, he was accorded a public funeral – an honor which had never before been bestowed by France on a man of science. He was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (french: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise ; formerly , "East Cemetery") is the largest cemetery in Paris, France (). With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world. Notable figures ...

in Paris.

''Arthur de Bretagne''

At the age of 19 Claude Bernard wrote an autobiographical prose play in five acts called ''Arthur de Bretagne'', which was published only after his death. A second edition appeared in 1943.Works

scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

in medicine. He dismissed several previous misconceptions, questioned common presumptions, and relied on experimentation. Unlike most of his contemporaries, he insisted that all living creatures were bound by the same laws as inanimate matter.

Claude Bernard's first important work was on the functions of the pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an en ...

, the juice of which he proved to be of great significance in the process of digestion; this achievement won him the prize for experimental physiology from the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at th ...

.

A second investigation – perhaps his most famous – was on the glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. The polysaccharide structure represents the main storage form of glucose in the body.

Glycogen functions as one o ...

ic function of the liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it ...

; in the course of his study he was led to the conclusion, which throws light on the causation of diabetes mellitus

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level (hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

, that the liver, in addition to secreting bile, is the seat of an internal secretion, by which it prepares sugar at the expense of the elements of the blood passing through it.

A third research resulted in the discovery of the vasomotor system. In 1851, while examining the effects produced in the temperature of various parts of the body by section of the nerve or nerves belonging to them, he noticed that division of the cervical sympathetic nerve gave rise to more active circulation and more forcible pulsation of the arteries in certain parts of the head, and a few months afterwards he observed that electrical excitation of the upper portion of the divided nerve had the contrary effect. In this way he established the existence of both vasodilator

Vasodilation is the widening of blood vessels. It results from relaxation of smooth muscle cells within the vessel walls, in particular in the large veins, large arteries, and smaller arterioles. The process is the opposite of vasoconstriction ...

and vasoconstrictor nerves.

The study of the physiological action of poisons was also of great interest to him, his attention being devoted in particular to curare

Curare ( /kʊˈrɑːri/ or /kjʊˈrɑːri/; ''koo-rah-ree'' or ''kyoo-rah-ree'') is a common name for various alkaloid arrow poisons originating from plant extracts. Used as a paralyzing agent by indigenous peoples in Central and Sout ...

and carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

gas. Bernard is widely credited with first describing carbon monoxide's affinity for hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

in 1857, although James Watt had drawn similar conclusions about hydrocarbonate's affinity for blood acting as "an antidote to the oxygen" in 1794 prior to the discoveries of carbon monoxide and hemoglobin.

Milieu intérieur

Milieu intérieur is the key concept with which Bernard is associated. He wrote, "The stability of the internal environment he ''milieu intérieur''is the condition for the free and independent life." This is the underlying principle of what would later be called homeostasis, a term coined byWalter Cannon

Walter Bradford Cannon (October 19, 1871 – October 1, 1945) was an American physiologist, professor and chairman of the Department of Physiology at Harvard Medical School. He coined the term " fight or flight response", and developed the theor ...

. He also explained that:

The living body, though it has need of the surrounding environment, is nevertheless relatively independent of it. This independence which the organism has of its external environment, derives from the fact that in the living being, the tissues are in fact withdrawn from direct external influences and are protected by a veritable internal environment which is constituted, in particular, by the fluids circulating in the body. The constancy of the internal environment is the condition for free and independent life: the mechanism that makes it possible is that which assured the maintenance, within the internal environment, of all the conditions necessary for the life of the elements. The constancy of the environment presupposes a perfection of the organism such that external variations are at every instant compensated and brought into balance. In consequence, far from being indifferent to the external world, the higher animal is on the contrary in a close and wise relation with it, so that its equilibrium results from a continuous and delicate compensation established as if the most sensitive of balances.

Vivisection

Bernard's scientific discoveries were made throughvivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experimen ...

, of which he was the primary proponent in Europe at the time. He wrote:

:The physiologist is no ordinary man. He is a learned man, a man possessed and absorbed by a scientific idea. He does not hear the animals' cries of pain. He is blind to the blood that flows. He sees nothing but his idea, and organisms which conceal from him the secrets he is resolved to discover.

Bernard practiced vivisection, to the disgust of his wife and daughters who had returned at home to discover that he had vivisected their dog. The couple was officially separated in 1869 and his wife went on to actively campaign against the practice of vivisection.

His wife and daughters were not the only ones disgusted by Bernard's animal experiments. The physician-scientist George Hoggan spent four months observing and working in Bernard's laboratory and was one of the few contemporary authors to chronicle what went on there. He was later moved to write that his experiences in Bernard's lab had made him "prepared to see not only science, but even mankind, perish rather than have recourse to such means of saving it."

''Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine''

In his major discourse on the scientific method, ''An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine'' (1865), Bernard described what makes a scientific theory good and what makes a scientist important, a true discoverer. Unlike many scientific writers of his time, Bernard wrote about his own experiments and thoughts, and used the first person.

''Known and Unknown''. What makes a scientist important, he states, is how well he or she has penetrated into the unknown. In areas of science where the facts are known to everyone, all scientists are more or less equal—we cannot know who is great. But in the area of science that is still obscure and unknown the great are recognized: "They are marked by ideas which light up phenomena hitherto obscure and carry science forward."

''Authority vs. Observation''. It is through the experimental method that science is carried forward—not through uncritically accepting the authority of academic or scholastic sources. In the experimental method, observable reality is our only authority. Bernard writes with scientific fervor:

:When we meet a fact which contradicts a prevailing theory, we must accept the fact and abandon the theory, even when the theory is supported by great names and generally accepted.

''Induction and Deduction''. Experimental science is a constant interchange between theory and fact, induction and deduction. Induction, reasoning from the particular to the general, and deduction, or reasoning from the general to the particular, are never truly separate. A general theory and our theoretical deductions from it must be tested with specific experiments designed to confirm or deny their truth; while these particular experiments may lead us to formulate new theories.

''Cause and Effect''. The scientist tries to determine the relation of cause and effect. This is true for all sciences: the goal is to connect a "natural phenomenon" with its "immediate cause". We formulate hypotheses elucidating, as we see it, the relation of cause and effect for particular phenomena. We test the hypotheses. And when an hypothesis is proved, it is a scientific theory. "Before that we have only groping and empiricism."

''Verification and Disproof''. Bernard explains what makes a theory good or bad scientifically:

:Theories are only hypotheses, verified by more or less numerous facts. Those verified by the most facts are the best, but even then they are never final, never to be absolutely believed.

In his major discourse on the scientific method, ''An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine'' (1865), Bernard described what makes a scientific theory good and what makes a scientist important, a true discoverer. Unlike many scientific writers of his time, Bernard wrote about his own experiments and thoughts, and used the first person.

''Known and Unknown''. What makes a scientist important, he states, is how well he or she has penetrated into the unknown. In areas of science where the facts are known to everyone, all scientists are more or less equal—we cannot know who is great. But in the area of science that is still obscure and unknown the great are recognized: "They are marked by ideas which light up phenomena hitherto obscure and carry science forward."

''Authority vs. Observation''. It is through the experimental method that science is carried forward—not through uncritically accepting the authority of academic or scholastic sources. In the experimental method, observable reality is our only authority. Bernard writes with scientific fervor:

:When we meet a fact which contradicts a prevailing theory, we must accept the fact and abandon the theory, even when the theory is supported by great names and generally accepted.

''Induction and Deduction''. Experimental science is a constant interchange between theory and fact, induction and deduction. Induction, reasoning from the particular to the general, and deduction, or reasoning from the general to the particular, are never truly separate. A general theory and our theoretical deductions from it must be tested with specific experiments designed to confirm or deny their truth; while these particular experiments may lead us to formulate new theories.

''Cause and Effect''. The scientist tries to determine the relation of cause and effect. This is true for all sciences: the goal is to connect a "natural phenomenon" with its "immediate cause". We formulate hypotheses elucidating, as we see it, the relation of cause and effect for particular phenomena. We test the hypotheses. And when an hypothesis is proved, it is a scientific theory. "Before that we have only groping and empiricism."

''Verification and Disproof''. Bernard explains what makes a theory good or bad scientifically:

:Theories are only hypotheses, verified by more or less numerous facts. Those verified by the most facts are the best, but even then they are never final, never to be absolutely believed.

When have we verified that we have found a cause? Bernard states:

:Indeed, proof that a given condition always precedes or accompanies a phenomenon does not warrant concluding with certainty that a given condition is the immediate cause of that phenomenon. It must still be established that when this condition is removed, the phenomenon will no longer appear…

We must always try to disprove our own theories. "We can solidly settle our ideas only by trying to destroy our own conclusions by counter-experiments." What is observably true is the only authority. If through experiment, you contradict your own conclusions—you must accept the contradiction—but only on one condition: that the contradiction is PROVED.

''Determinism and Averages''. In the study of disease, "the real and effective cause of a disease must be constant and determined, that is, unique; anything else would be a denial of science in medicine." In fact, a "very frequent application of mathematics to biology sthe use of averages"—that is, statistics—which may give only "apparent accuracy". Sometimes averages do not give the kind of information needed to save lives. For example:

:A great surgeon performs operations for stone by a single method; later he makes a statistical summary of deaths and recoveries, and he concludes from these statistics that the mortality law for this operation is two out of five. Well, I say that this ratio means literally nothing scientifically and gives us no certainty in performing the next operation; for we do not know whether the next case will be among the recoveries or the deaths. What really should be done, instead of gathering facts empirically, is to study them more accurately, each in its special determinism….to discover in them the cause of mortal accidents so as to master the cause and avoid the accidents.

Although the application of mathematics to every aspect of science is its ultimate goal, biology is still too complex and poorly understood. Therefore, for now the goal of medical science should be to discover all the new facts possible. Qualitative analysis must always precede quantitative analysis.

''Truth vs. Falsification''. The "philosophic spirit", writes Bernard, is always active in its desire for truth. It stimulates a "kind of thirst for the unknown" which ennobles and enlivens science—where, as experimenters, we need "only to stand face to face with nature". The minds that are great "are never self-satisfied, but still continue to strive." Among the great minds he names

When have we verified that we have found a cause? Bernard states:

:Indeed, proof that a given condition always precedes or accompanies a phenomenon does not warrant concluding with certainty that a given condition is the immediate cause of that phenomenon. It must still be established that when this condition is removed, the phenomenon will no longer appear…

We must always try to disprove our own theories. "We can solidly settle our ideas only by trying to destroy our own conclusions by counter-experiments." What is observably true is the only authority. If through experiment, you contradict your own conclusions—you must accept the contradiction—but only on one condition: that the contradiction is PROVED.

''Determinism and Averages''. In the study of disease, "the real and effective cause of a disease must be constant and determined, that is, unique; anything else would be a denial of science in medicine." In fact, a "very frequent application of mathematics to biology sthe use of averages"—that is, statistics—which may give only "apparent accuracy". Sometimes averages do not give the kind of information needed to save lives. For example:

:A great surgeon performs operations for stone by a single method; later he makes a statistical summary of deaths and recoveries, and he concludes from these statistics that the mortality law for this operation is two out of five. Well, I say that this ratio means literally nothing scientifically and gives us no certainty in performing the next operation; for we do not know whether the next case will be among the recoveries or the deaths. What really should be done, instead of gathering facts empirically, is to study them more accurately, each in its special determinism….to discover in them the cause of mortal accidents so as to master the cause and avoid the accidents.

Although the application of mathematics to every aspect of science is its ultimate goal, biology is still too complex and poorly understood. Therefore, for now the goal of medical science should be to discover all the new facts possible. Qualitative analysis must always precede quantitative analysis.

''Truth vs. Falsification''. The "philosophic spirit", writes Bernard, is always active in its desire for truth. It stimulates a "kind of thirst for the unknown" which ennobles and enlivens science—where, as experimenters, we need "only to stand face to face with nature". The minds that are great "are never self-satisfied, but still continue to strive." Among the great minds he names Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted e ...

and Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal ( , , ; ; 19 June 1623 – 19 August 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and Catholic writer.

He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen. Pascal's earlies ...

.

Meanwhile, there are those whose "minds are bound and cramped". They oppose discovering the unknown (which "is generally an unforeseen relation not included in theory") because they do not want to discover anything that might disprove their own theories. Bernard calls them "despisers of their fellows" and says "the dominant idea of these despisers of their fellows is to find others' theories faulty and try to contradict them."Bernard (1957), p. 38. They are deceptive, for in their experiments they report only results that make their theories seem correct and suppress results that support their rivals. In this way, they "falsify science and the facts":

:They make poor observations, because they choose among the results of their experiments only what suits their object, neglecting whatever is unrelated to it and carefully setting aside everything which might tend toward the idea they wish to combat.

''Discovering vs. Despising''. The "despisers of their fellows" lack the "ardent desire for knowledge" that the true scientific spirit will always have—and so the progress of science will never be stopped by them. Bernard writes:

:Ardent desire for knowledge, in fact, is the one motive attracting and supporting investigators in their efforts; and just this knowledge, really grasped and yet always flying before them, becomes at once their sole torment and their sole happiness….A man of science rises ever, in seeking truth; and if he never finds it in its wholeness, he discovers nevertheless very significant fragments; and these fragments of universal truth are precisely what constitutes science.Bernard (1957), p. 22.

See also

*Physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

*Medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

References

Attribution: *Further reading

* * Holmes, Frederic Lawrence. ''Claude Bernard and Animal Chemistry: The Emergence of a Scientist''. Harvard University Press, 1974. * Olmsted, J. M. D. and E. Harris. ''Claude Bernard and the Experimental Method in Medicine''. New York: Henry Schuman, 1952. * Wise, Peter. ''"A Matter of Doubt – the novel of Claude Bernard".'' CreateSpace, 2011 and ''"Un défi sans fin – la vie romancée de Claude Bernard"'' La Société des Ecrivains, Paris, 2011.External links

* * *Biography, bibliography, and links on digitized sources

in the Virtual Laboratory of the

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (German: Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte) is a scientific research institute founded in March 1994. It is dedicated to addressing fundamental questions of the history of knowledg ...

'Claude Bernard': detailed biography and a comprehensive bibliography linked to complete on-line texts, quotations, images and more.

*

Biography and genealogy of Claude Bernard

*

Claude Bernard's works

digitized by th

BIUM (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Paris)

see its digital librar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bernard, Claude 1813 births 1878 deaths People from Rhône (department) Collège de France faculty French Roman Catholics French physiologists French medical writers Members of the Académie Française Members of the French Academy of Sciences Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Recipients of the Copley Medal Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters École pratique des hautes études faculty Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences University of Paris faculty Foreign Members of the Royal Society