circumnavigate on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Circumnavigation is the complete

Circumnavigation is the complete

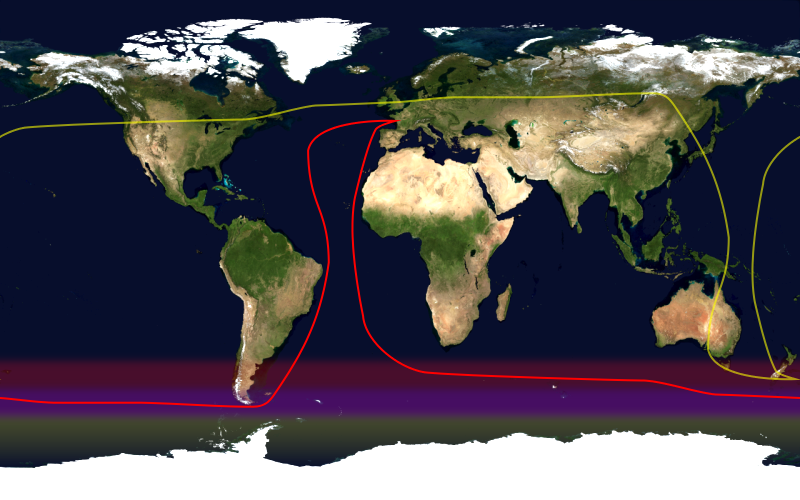

The map on the right shows, in red, a typical, non-competitive, route for a

The map on the right shows, in red, a typical, non-competitive, route for a  In

In

According to adjudicating bodies ''

According to adjudicating bodies ''

Route of the first circumnavigation in Google Maps and Earth

{{Authority control 16th-century introductions Navigation

navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

around an entire island

An island or isle is a piece of land, distinct from a continent, completely surrounded by water. There are continental islands, which were formed by being split from a continent by plate tectonics, and oceanic islands, which have never been ...

, continent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention (norm), convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as ...

, or astronomical body

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical object, physical entity, association, or structure that exists within the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ...

(e.g. a planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

or moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

.

The first circumnavigation of the Earth was the Magellan Expedition

The Magellan expedition, sometimes termed the MagellanElcano expedition, was a 16th-century Spanish Empire, Spanish expedition planned and led by Portuguese Empire, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan. One of the most important voyages in th ...

, which sailed from Sanlucar de Barrameda, Spain in 1519 and returned in 1522, after crossing the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

, Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

, and Indian oceans. Since the rise of commercial aviation

Commercial aviation is the part of civil aviation that involves operating aircraft for remuneration or hire, as opposed to private aviation.

Definition

Commercial aviation is not a rigorously defined category. All commercial air transport and ae ...

in the late 20th century, circumnavigating Earth is straightforward, usually taking days instead of years. Today, the challenge of circumnavigating Earth has shifted towards human and technological endurance, speed, and less conventional methods.

Etymology

The word ''circumnavigation'' is a noun formed from the verb ''circumnavigate'', from the past participle of theLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

verb ''circumnavigare'', from ''circum'' "around" + ''navigare'' "to sail".

Definition

A person walking completely around either pole will cross all meridians, but this is not generally considered a "circumnavigation". The path of a true (global) circumnavigation forms a continuous loop on the surface of Earth separating two regions of comparable area. A basic definition of a global circumnavigation would be a route which covers roughly agreat circle

In mathematics, a great circle or orthodrome is the circular intersection of a sphere and a plane passing through the sphere's center point.

Discussion

Any arc of a great circle is a geodesic of the sphere, so that great circles in spher ...

, and in particular one which passes through at least one pair of points antipodal

Antipode or Antipodes may refer to:

Mathematics

* Antipodal point, the diametrically opposite point on a circle or ''n''-sphere, also known as an antipode

* Antipode, the convolution inverse of the identity on a Hopf algebra

Geography

* Antipodes ...

to each other. In practice, people use different definitions of world circumnavigation to accommodate practical constraints, depending on the method of travel. Since the planet is quasispheroidal, a trip from one Pole to the other, and back again on the other side, would technically be a circumnavigation. There are practical difficulties (namely, the Arctic ice pack

The Arctic ice pack is the sea ice cover of the Arctic Ocean and its vicinity. The Arctic ice pack undergoes a regular seasonal cycle in which ice melts in spring and summer, reaches a minimum around mid-September, then increases during fall a ...

and the Antarctic ice sheet

The Antarctic ice sheet is a continental glacier covering 98% of the Antarctic continent, with an area of and an average thickness of over . It is the largest of Earth's two current ice sheets, containing of ice, which is equivalent to 61% of ...

) in such a voyage, although it was successfully undertaken in the early 1980s by Ranulph Fiennes

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, 3rd Baronet (born 7 March 1944), commonly known as Sir Ranulph Fiennes () and sometimes as Ran Fiennes, is a British explorer, writer and poet, who holds several endurance records.

Fiennes served in the ...

.

History

The first circumnavigation was that of the ship ''Victoria'' between 1519 and 1522, now known as the Magellan–Elcano expedition. It was a Castilian (Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

) voyage of discovery. The voyage started in Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, crossed the Atlantic Ocean, andafter several stopsrounded the southern tip of South America, where the expedition named the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

. It then continued across the Pacific, discovering a number of islands on its way (including Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

), before arriving in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. The voyage was initially led by the Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer best known for having planned and led the 1519–22 Spanish expedition to the East Indies. During this expedition, he also discovered the Strait of Magellan, allowing his fl ...

but he was killed on Mactan

Mactan is a densely populated island located a few kilometers (~1 mile) east of Cebu Island in the Philippines. The island is part of Cebu province and it is divided into the city of Lapu-Lapu and the municipality of Cordova.

The island is ...

in the Philippines in 1521. The remaining sailors decided to circumnavigate the world instead of making the return voyageno passage east across the Pacific would be successful for four decadesand continued the voyage across the Indian Ocean, round the southern cape of Africa, north along Africa's Atlantic coasts, and back to Spain in 1522. Of the 270 crew members who set out from Seville, only 18 were still with the expedition at the end including its surviving captain, the Spaniard Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano (Elkano in modern Basque language, Basque; also known as ''del Cano''; 1486/1487 – 4 August 1526) was a Spaniards, Spanish navigator, ship-owner and explorer of Basques, Basque origin, ship-owner and explorer from Getaria ...

.

The next to circumnavigate the globe were the survivors of the Castilian/Spanish expedition of García Jofre de Loaísa

García or Garcia may refer to:

People

* García (surname)

* Kings of Pamplona/Navarre

** García Íñiguez of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 851/2–882

** García Sánchez I of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 931–970

** García Sánchez II of Pam ...

between 1525 and 1536. None of the seven original ships of the Loaísa expedition nor its first four leadersLoaísa, Elcano, Salazar, and Íñiguezsurvived to complete the voyage. The last of the original ships, the , was sunk in 1526 in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

(now Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

) by the Portuguese. Unable to press forward or retreat, Hernando de la Torre erected a fort on Tidore

Tidore (, lit. "City of Tidore Islands") is a city, island, and archipelago in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, west of the larger island of Halmahera. Part of North Maluku Province, the city includes the island of Tidore (with three sm ...

, received reinforcements under Alvaro de Saavedra that were similarly defeated, and finally surrendered to the Portuguese. In this way, a handful of survivors became the second group of circumnavigators when they were transported under guard to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

in 1536. A third group came from the 117 survivors of the similarly failed Villalobos Expedition in the next decade; similarly ruined and starved, they were imprisoned by the Portuguese and transported back to Lisbon in 1546.

In 1577, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

sent Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

to start an expedition against the Spanish along the Pacific coast of the Americas. Drake set out from Plymouth, England in November 1577, aboard ''Pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

'', which he renamed ''Golden Hind'' mid-voyage. In September 1578, the ship passed south of Tierra del Fuego, the southern tip of South America, through the area now known as the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile, Argentina, and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean (Scotia Sea) with the southeastern part of the Pa ...

.Wagner, Henry R., ''Sir Francis Drake's Voyage Around the World: Its Aims and Achievements'', Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2006, In June 1579, Drake landed somewhere north of Spain's northernmost claim in Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

, presumably Drakes Bay

Drakes Bay ( Coast Miwok: ''Tamál-Húye'') is a bay along the Point Reyes National Seashore on the coast of northern California in the United States, approximately northwest of San Francisco at approximately 38 degrees north latitude. The ...

. Drake completed the second complete circumnavigation of the world in a single vessel on September 1580, becoming the first commander to survive the entire circumnavigation.

Thomas Cavendish completed his circumnavigation between 1586 and 1588 in record timein two years and 49 days, nine months faster than Drake. It was also the first deliberately planned voyage of the globe.

Jeanne Baret is recognized as the first woman to have completed a voyage of circumnavigation of the globe, which she did via maritime transport

Maritime transport (or ocean transport) or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people (passengers or goods (cargo) via waterways. Freight transport by watercraft has been widely used throughout recorded history, as it pr ...

. A key part of her journey was as a member of Louis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (; 12 November 1729 – 31 August 1811) was a French military officer and explorer. A contemporary of the British explorer James Cook, he served in the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War. B ...

's expedition on the ships '' La Boudeuse'' and '' Étoile'' in 1766–1769.

Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

became the first navigator to record three circumnavigations through the Pacific aboard the ''Endeavour'' from 1769 to 1779. He was among the first to complete west–east circumnavigation in high latitudes.

For the wealthy, long voyages around the world, such as was done by Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, became possible in the 19th century, and the two World Wars moved vast numbers of troops around the planet. The rise of commercial aviation in the late 20th century made circumnavigation even quicker and safer.

Nautical

The nautical global and fastest circumnavigation record is currently held by a wind-powered vessel, the trimaran IDEC 3. The record was established by six sailors: Francis Joyon, Alex Pella, Clément Surtel, Gwénolé Gahinet, Sébastien Audigane and Bernard Stamm. On 26 January, 2017, this crew finished circumnavigating the globe in 40 days, 23 hours, 30 minutes and 30 seconds. The absolute speed sailing record around the world followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Equator, South Atlantic Ocean, Southern Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Equator, North Atlantic Ocean route in an easterly direction.Wind powered

The map on the right shows, in red, a typical, non-competitive, route for a

The map on the right shows, in red, a typical, non-competitive, route for a sailing

Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship, sailboat, raft, Windsurfing, windsurfer, or Kitesurfing, kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat) or on ''land'' (Land sa ...

circumnavigation of the world by the trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere, ...

s and the Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

and Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

canals; overlaid in yellow are the points antipodal to all points on the route. It can be seen that the route roughly approximates a great circle

In mathematics, a great circle or orthodrome is the circular intersection of a sphere and a plane passing through the sphere's center point.

Discussion

Any arc of a great circle is a geodesic of the sphere, so that great circles in spher ...

, and passes through two pairs of antipodal points. This is a route followed by many cruising sailors, going in the western direction; the use of the trade winds makes it a relatively easy sail, although it passes through a number of zones of calms or light winds.

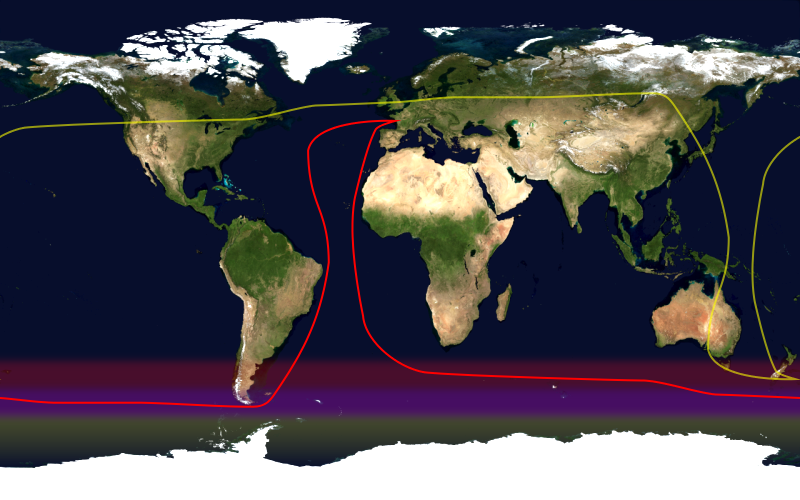

In

In yacht racing

Yacht racing is a Sailing (sport), sailing sport involving sailing yachts and larger sailboats, as distinguished from dinghy racing, which involves open boats. It is composed of multiple yachts, in direct competition, racing around a course mark ...

, a round-the-world route approximating a great circle would be quite impractical, particularly in a non-stop race where use of the Panama and Suez Canals would be impossible. Yacht racing therefore defines a world circumnavigation to be a passage of at least 21,600 nautical miles (40,000 km) in length which crosses the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

, crosses every meridian and finishes in the same port as it starts. The second map on the right shows the route of the Vendée Globe round-the-world race in red; overlaid in yellow are the points antipodal to all points on the route. It can be seen that the route does not pass through any pairs of antipodal points. Since the winds in the higher southern latitudes predominantly blow west-to-east it can be seen that there are an easier route (west-to-east) and a harder route (east-to-west) when circumnavigating by sail; this difficulty is magnified for square-rig

Square rig is a generic type of sail and rigging arrangement in which a sailing vessel's primary driving sails are carried on horizontal spars that are perpendicular (or square) to the median plane of the keel and masts of the vessel. These s ...

vessels due to the square rig's dramatic lack of upwind ability when compared to a more modern Bermuda rig

Bermuda rig, Bermudian rig, or Marconi rig is a type of sailing rig that uses a triangular sail set abaft (behind) the mast. It is the typical configuration for most modern sailboats. Whilst commonly seen in sloop-rigged vessels, Bermuda rig is ...

.

For around the world sailing records, there is a rule saying that the length must be at least 21,600 nautical miles calculated along the shortest possible track from the starting port and back that does not cross land and does not go below 63°S. It is allowed to have one single waypoint to lengthen the calculated track. The equator must be crossed.

The solo wind powered circumnavigation record of 42 days, 16 hours, 40 minutes and 35 seconds was established by François Gabart on the maxi-multihull sailing yacht MACIF and completed on 7 December 2017. The voyage followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Equator, South Atlantic Ocean, Southern Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Equator, North Atlantic Ocean route in an easterly direction.

Mechanically powered

Since the advent of world cruises in 1922, by Cunard's ''Laconia'', thousands of people have completed circumnavigations of the globe at a more leisurely pace. Typically, these voyages begin inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

or Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

, and proceed westward. Routes vary, either travelling through the Caribbean and then into the Pacific Ocean via the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

, or around Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

. From there ships usually make their way to Hawaii, the islands of the South Pacific, Australia, New Zealand, then northward to Hong Kong, South East Asia, and India. At that point, again, routes may vary: one way is through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

and into the Mediterranean; the other is around Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

and then up the west coast of Africa. These cruises end in the port where they began.

In 1960, the American nuclear-powered submarine USS ''Triton'' circumnavigated the globe in 60 days, 21 hours for Operation Sandblast

Operation Sandblast was the code name for the first submarine circumnavigation of the world. It was executed by the United States Navy nuclear-powered submarine, nuclear-powered radar picket submarine in 1960 under the command of Captain Edward ...

.

The current circumnavigation record in a powered boat of 60 days 23 hours and 49 minutes was established by a voyage of the wave-piercing trimaran '' Earthrace'' which was completed on 27 June 2008. The voyage followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Panama Canal, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Suez Canal, Mediterranean Sea route in a westerly direction.

Aviation

In 1922 Norman Macmillan (RAF officer), Major W T Blake and Geoffrey Malins made an unsuccessful attempt to fly a ''Daily News''-sponsored round-the-world flight. The first aerial circumnavigation of the planet was flown in 1924 by aviators of the U.S. Army Air Service in a quartet of Douglas World Cruiser biplanes. The first non-stop aerial circumnavigation of the planet was flown in 1949 byLucky Lady II

''Lucky Lady II'' is a United States Air Force Boeing B-50 Superfortress that became the first airplane to circumnavigate, circle the world nonstop. Its 1949 journey, assisted by in-flight refueling, lasted 94 hours and 1 minute.

1949: First cir ...

, a United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

Boeing B-50 Superfortress

The Boeing B-50 Superfortress is a retired American strategic bomber. A post–World War II revision of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, it was fitted with more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial engines, stronger structure, a taller tail fin ...

.

Since the development of commercial aviation, there are regular routes that circle the globe, such as Pan American Flight One (and later United Airlines

United Airlines, Inc. is a Major airlines of the United States, major airline in the United States headquartered in Chicago, Chicago, Illinois that operates an extensive domestic and international route network across the United States and six ...

Flight One). Today planning such a trip through commercial flight connections is simple.

The first lighter-than-air

A lifting gas or lighter-than-air gas is a gas that has a density lower than normal atmospheric gases and rises above them as a result, making it useful in lifting lighter-than-air aircraft. Only certain lighter-than-air gases are suitable as lift ...

aircraft of any type to circumnavigate under its own power was the rigid airship

A rigid airship is a type of airship (or dirigible) in which the Aerostat, envelope is supported by an internal framework rather than by being kept in shape by the pressure of the lifting gas within the envelope, as in blimps (also called pres ...

LZ 127 ''Graf Zeppelin'', which did so in 1929.

Aviation records take account of the wind circulation patterns of the world; in particular the jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow thermal wind, air currents in the Earth's Atmosphere of Earth, atmosphere.

The main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are westerly winds, flowing west to east around the gl ...

s, which circulate in the northern and southern hemispheres without crossing the equator. There is therefore no requirement to cross the equator, or to pass through two antipodal points, in the course of setting a round-the-world aviation record.

For powered aviation, the course of a round-the-world record must start and finish at the same point and cross all meridians; the course must be at least long (which is approximately the length of the Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, also known as the Northern Tropic, is the Earth's northernmost circle of latitude where the Sun can be seen directly overhead. This occurs on the June solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun ...

). The course must include set control points at latitudes outside the Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

and Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

circles.

In ballooning, which is at the mercy of the winds, the requirements are even more relaxed. The course must cross all meridians, and must include a set of checkpoints which are all outside of two circles, chosen by the pilot, having radii of and enclosing the poles (though not necessarily centred on them). For example, Steve Fossett

James Stephen Fossett (April 22, 1944 – September 3, 2007) was an American businessman and a record-setting aviator, sailor, and adventurer. He was the first person to fly solo nonstop around the world in a balloon and in a fixed-wing aircraf ...

's global circumnavigation by balloon was entirely contained within the southern hemisphere.

Astronautics

The first person to fly in space,Yuri Gagarin

Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin; Gagarin's first name is sometimes transliterated as ''Yuriy'', ''Youri'', or ''Yury''. (9 March 1934 – 27 March 1968) was a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful Human spaceflight, crewed sp ...

, also became the first person to complete an orbital spaceflight

An orbital spaceflight (or orbital flight) is a spaceflight in which a spacecraft is placed on a trajectory where it could remain in space for at least one orbit. To do this around the Earth, it must be on a free trajectory which has an altit ...

in the Vostok 1

Vostok 1 (, ) was the first spaceflight of the Vostok programme and the first human spaceflight, human orbital spaceflight in history. The Vostok 3KA space capsule was launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome on 12 April 1961, with Soviet astronaut, c ...

spaceship within 2 hours on April 12 1961. The flight started at 63° E, 45 N and ended at 45° E 51° N; thus Gagarin did not circumnavigate Earth completely.

Gherman Titov in the Vostok 2 was the first human to fully circumnavigate Earth in spaceflight and made 17.5 orbits on August 6, 1961.

Human-powered

According to adjudicating bodies ''

According to adjudicating bodies ''Guinness World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a British reference book published annually, list ...

'' and Explorersweb, Jason Lewis completed the first human-powered circumnavigation of the globe on 6 October 2007. This was part of a thirteen-year journey entitled Expedition 360.

In 2012, Turkish-born American adventurer Erden Eruç completed the first entirely ''solo'' human-powered circumnavigation, travelling by rowboat, sea kayak

A sea kayak or touring kayak is a kayak used for the sport of Watercraft paddling, paddling on open waters of lakes, bays, and oceans. Sea kayaks are seaworthy small boats with a covered deck and the ability to incorporate a spray deck. They t ...

, foot and bicycle from 10 July 2007 to 21 July 2012, crossing the equator twice, passing over 12 antipodal points, and logging in 1,026 days of travel time, excluding breaks.

National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly ''The National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as ''Nat Geo'') is an American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. The magazine was founded in 1888 as a scholarly journal, nine ...

lists Colin Angus as being the first to complete a human-powered global circumnavigation in 2006. However, his journey did not cross the equator or hit the minimum of two antipodal points as stipulated by the rules of ''Guinness World Records'' and AdventureStats by Explorersweb.

People have both bicycled and run around the world, but the oceans have had to be covered by air or sea travel, making the distance shorter than the ''Guinness'' guidelines. To go from North America to Asia on foot is theoretically possible but very difficult. It involves crossing the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

on the ice, and around of roadless swamped or freezing cold areas in Alaska and eastern Russia. No one has so far travelled all of this route by foot. David Kunst was the first person that Guinness verified to have walked around the world between 20 June 1970 and 5 October 1974, by " alking23,250 km (14,450 miles) through four continents".

Notable circumnavigations

Maritime

* The Castilian ('Spanish')Magellan-Elcano expedition

The Magellan expedition, sometimes termed the MagellanElcano expedition, was a 16th-century Spanish Empire, Spanish expedition planned and led by Portuguese Empire, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan. One of the most important voyages in th ...

of August 1519 to 8 September 1522, started by Portuguese navigator Fernão de Magalhães (Ferdinand Magellan) and completed by Spanish Basque navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano (Elkano in modern Basque language, Basque; also known as ''del Cano''; 1486/1487 – 4 August 1526) was a Spaniards, Spanish navigator, ship-owner and explorer of Basques, Basque origin, ship-owner and explorer from Getaria ...

after Magellan's death, was the first global circumnavigation (see ''Victoria'').

* The survivors of García Jofre de Loaísa

García or Garcia may refer to:

People

* García (surname)

* Kings of Pamplona/Navarre

** García Íñiguez of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 851/2–882

** García Sánchez I of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 931–970

** García Sánchez II of Pam ...

's Spanish expedition 1525–1536, including Andrés de Urdaneta

Andres or Andrés may refer to:

* Andres, Illinois, an unincorporated community in Will County, Illinois, US

* Andres, Pas-de-Calais, a commune in Pas-de-Calais, France

*Andres (name)

Andres or Andrés is a male given name. It can also be a ...

and Hans von Aachen, who was also one of the 18 survivors of Magellan's expedition, making him the first to circumnavigate the world twice.

* Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

carried out the second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition (and on a single independent voyage), from 1577 to 1580.

* Jeanne Baret is the first woman to complete a voyage of circumnavigation, in 1766–1769.

* John Hunter commanded the first ship to circumnavigate the World starting from Australia, between 2 September 1788 and 8 May 1789, with one stop in Cape Town to load supplies for the colony of New South Wales.

* completed the first circumnavigation by a steam ship in 1845–1847.

* The Spanish frigate '' Numancia'', commanded by Juan Bautista Antequera y Bobadilla, completed the first circumnavigation by an ironclad

An ironclad was a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by iron armour, steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or ince ...

in 1865–1867.

* Joshua Slocum

Joshua Slocum (February 20, 1844 – on or shortly after November 14, 1909) was the first person to sail single-handedly around the world. He was a Nova Scotian-born, naturalised American seaman and adventurer, and a noted writer. In 1900 he w ...

completed the first single-handed circumnavigation in 1895–1898.

* In 1942, Vito Dumas became the first person to single-handedly circumnavigate the globe along the Roaring Forties

The Roaring Forties are strong westerlies, westerly winds that occur in the Southern Hemisphere, generally between the latitudes of 40th parallel south, 40° and 50th parallel south, 50° south. The strong eastward air currents are caused by ...

.

* In 1960, the U.S. Navy nuclear-powered submarine completed the submerged circumnavigation.

* In 1969, Robin Knox-Johnston became the first person to complete a single-handed non-stop circumnavigation.

* In 1999, Jesse Martin became the youngest recognized person to complete an unassisted, non-stop, circumnavigation, at the age of 18.

* In 2001, the U.S. Coast Guard became the first Coast Guard vessel to circumnavigate the globe.

* In 2012, ''PlanetSolar'' became the first ever solar electric vehicle to circumnavigate the globe.

* In 2012, Laura Dekker became the youngest person to circumnavigate the globe single-handed, with stops, at the age of 16.

* In 2017, trimaran '' IDEC 3'' with sailors: Francis Joyon, Alex Pella, Clément Surtel, Gwénolé Gahinet, Sébastien Audigane and Bernard Stamm completes the fastest circumnavigation of the globe ever; in 40 days, 23 hours, 30 minutes and 30 seconds. The voyage followed the North Atlantic Ocean, Equator, South Atlantic Ocean, Southern Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Equator, North Atlantic Ocean route in an easterly direction.

* In 2022, the ''MV Astra'', a former Swedish Sea Rescue Society ship became the first sub-24m motor-powered vessel to circumnavigate the globe via the southern capes.

Aviation

*United States Army Air Service

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 9 (also known as the ''"Air Service"'', ''"U.S. Air Service"'' and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the ''"Air Service, United States Army"'') was the aerial warf ...

, 1924, first aerial circumnavigation, 175 days, covering , with examples of the Douglas World Cruiser biplane.

* In 1949, the ''Lucky Lady II

''Lucky Lady II'' is a United States Air Force Boeing B-50 Superfortress that became the first airplane to circumnavigate, circle the world nonstop. Its 1949 journey, assisted by in-flight refueling, lasted 94 hours and 1 minute.

1949: First cir ...

'', a Boeing B-50 Superfortress

The Boeing B-50 Superfortress is a retired American strategic bomber. A post–World War II revision of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, it was fitted with more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial engines, stronger structure, a taller tail fin ...

of the U.S. Air Force, commanded by Captain James Gallagher, became the first aeroplane to circle the world non-stop (by refueling the plane in flight). Total time airborne was 94 hours and one minute.

* In 1957, three United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic aircraft, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the ...

es made the first non-stop jet-aircraft circumnavigation in 45 hours and 19 minutes, with two in-air refuelings.

* In 1964, Geraldine "Jerrie" Mock was the first woman to fly solo around the world.

* In 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager made the first non-refueled circumnavigation in an airplane ( Rutan Voyager), in 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds.

* In 1999, Bertrand Piccard

Bertrand Piccard Royal Scottish Geographical Society, FRSGS (born 1 March 1958) is a Swiss explorer, psychiatrist and balloon (aircraft), environmentalist. Along with Brian Jones (aeronaut), Brian Jones, he was the first to complete a non-stop b ...

and Brian Jones

Lewis Brian Hopkin Jones (28 February 1942 – 3 July 1969) was an English musician and founder of the Rolling Stones. Initially a slide guitarist, he went on to sing backing vocals and played a wide variety of instruments on Rolling Stones r ...

, achieved the first non-stop balloon

A balloon is a flexible membrane bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, or air. For special purposes, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), ...

circumnavigation in '' Breitling Orbiter 3''.

* In 2002, Steve Fossett

James Stephen Fossett (April 22, 1944 – September 3, 2007) was an American businessman and a record-setting aviator, sailor, and adventurer. He was the first person to fly solo nonstop around the world in a balloon and in a fixed-wing aircraf ...

, after flying on the ''Spirit of Freedom'' balloon gondola, became the first person to fly around the world alone, nonstop in any kind of aircraft. Fossett's sole source of aid was a control center in Brookings Hall

Brookings Hall is a Collegiate Gothic landmark on the campus of Washington University in St. Louis. The building, first named "University Hall", was built between 1900 and 1902 and served as the administrative center for the 1904 World's Fair ...

of Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) is a private research university in St. Louis, Missouri, United States. Founded in 1853 by a group of civic leaders and named for George Washington, the university spans 355 acres across its Danforth ...

.

* In 2005, Steve Fossett

James Stephen Fossett (April 22, 1944 – September 3, 2007) was an American businessman and a record-setting aviator, sailor, and adventurer. He was the first person to fly solo nonstop around the world in a balloon and in a fixed-wing aircraf ...

, flying a Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, set the current record for fastest aerial circumnavigation (first non-stop, non-refueled solo circumnavigation in an airplane) in 67 hours, covering 37,000 kilometers.

* In 2014, Matt Guthmiller became the youngest person to solo circumnavigate by air at age 19 years, 7 months, and 15 days.

* In 2016, Bertrand Piccard

Bertrand Piccard Royal Scottish Geographical Society, FRSGS (born 1 March 1958) is a Swiss explorer, psychiatrist and balloon (aircraft), environmentalist. Along with Brian Jones (aeronaut), Brian Jones, he was the first to complete a non-stop b ...

and André Borschberg completed the first solar-powered aircraft circumnavigation of the world in '' Solar Impulse 2''.

* In 2020, One More Orbit completed the fastest circumnavigation via both geographic poles in a Gulfstream G650ER.

* In 2020, Robert DeLaurentis and his twin-engine aircraft "Citizen of the World" became the first pilot and plane to successfully use biofuels over the North and South poles.

Land

* In 1841–1842 Sir George Simpson made the first "land circumnavigation", crossing Canada and Siberia and returning to London. *Ranulph Fiennes

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, 3rd Baronet (born 7 March 1944), commonly known as Sir Ranulph Fiennes () and sometimes as Ran Fiennes, is a British explorer, writer and poet, who holds several endurance records.

Fiennes served in the ...

and Charlie Burton are credited with the first north–south circumnavigation of the Earth.

Human

* On 13 June 2003, Robert Garside completed the first recognized run around the world, taking years; the run was authenticated in 2007 by ''Guinness World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a British reference book published annually, list ...

'' after five years of verification.

* On 6 October 2007, Jason Lewis completed the first human-powered circumnavigation of the globe (including human-powered sea crossings).

* On 21 July 2012, Erden Eruç completed the first entirely ''solo'' human-powered circumnavigation of the globe.

* On 4 April 2024, Latvian adventurer kārlis Bardelis completed a 2,898-day human-powered circumnavigation of the globe that involved rowing 46,326km and cycling 11,972km.

See also

* ''Around the World in Eighty Days

''Around the World in Eighty Days'' () is an adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in French in 1872. In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employed French valet Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate ...

''

* List of circumnavigations

This is a list of circumnavigations of Earth. Sections are ordered by ascending date of completion.

Global Nautical

16th century

* The 18 survivors, led by Juan Sebastián Elcano (Spanish), of Ferdinand Magellan's Magellan's circumnavigation ...

* Circumnavigation world record progression

This is a list of the fastest circumnavigation, made by a person or team, excluding orbits of Earth from spacecraft.

List

Other categories

See also

*List of circumnavigations

This is a list of circumnavigations of Earth. Sections are ord ...

* Transglobe Expedition

References

Further reading

*External links

* *Route of the first circumnavigation in Google Maps and Earth

{{Authority control 16th-century introductions Navigation