Chukat, HuQath , Hukath, or Chukkas ( —

Chukat, HuQath , Hukath, or Chukkas ( — Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or , '' aliyot''.

First reading — Numbers 19:1–17

In the first reading (, ''aliyah''),

Second reading — Numbers 19:18–20:6

In the second reading (, ''aliyah''), a person who was clean was to add fresh water to ashes of the Red Cow, dip hyssop it in the water, and sprinkle the water on the tent, the vessels, and people who had become unclean. The person who sprinkled the water was then to wash his clothes, bathe in water, and be clean at nightfall. Anyone who became unclean and failed to cleanse himself was to be cut off from the congregation. The person who sprinkled the water of lustration was to wash his clothes, and whoever touched the water of lustration, whatever he touched, and whoever touched him were to be unclean until evening. The Israelites arrived at

Third reading — Numbers 20:7–13

In the third reading (, ''aliyah''), God told Moses that he and Aaron should take the rod and order the rock to yield its water. Moses took the rod, assembled the congregation in front of the rock, and said to them: "Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?" Then Moses struck the rock twice with his rod, out came water, and the community and their animals drank. But God told Moses and Aaron: "Because you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people, therefore you shall not lead this congregation into the land that I have given them." The water was named Meribah, meaning ''quarrel'' or ''contention''."Fourth reading — Numbers 20:14–21

In the fourth reading (, ''aliyah''), Moses sent messengers to the king ofFifth reading — Numbers 20:22–21:9

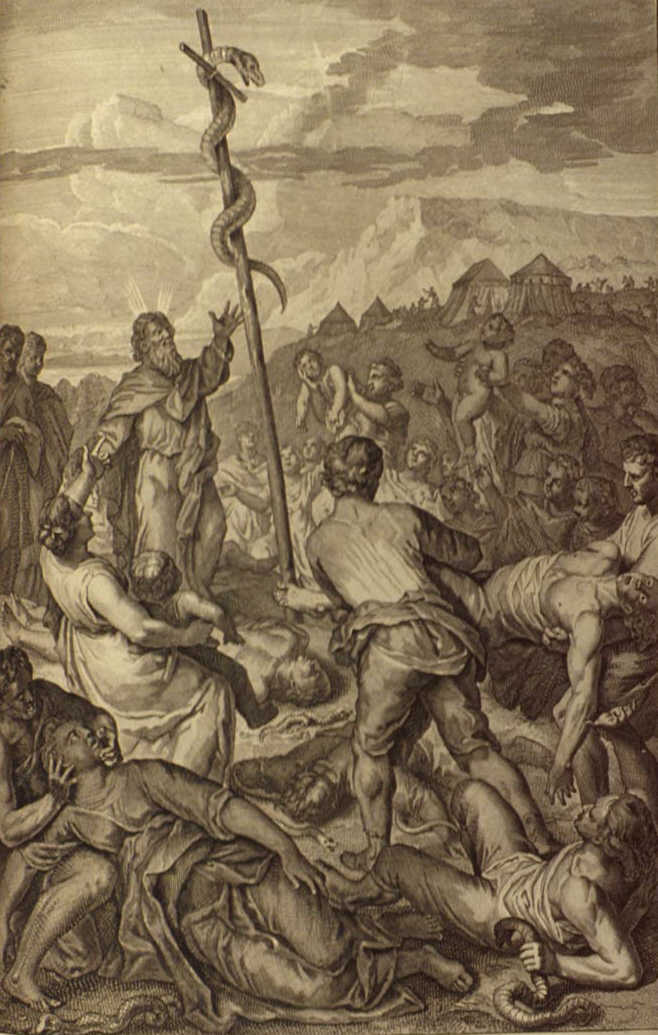

In the fifth reading (, ''aliyah''), at

Sixth reading — Numbers 21:10–20

In the sixth reading (, ''aliyah''), the Israelites traveled on toSeventh reading — Numbers 21:21–22:1

In the seventh reading (, ''aliyah''), the Israelites sent messengers toReadings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to theIn inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:Numbers chapter 19

Corpse contamination

The discussion of the Red Cow mixture for decontamination from corpse contamination in is one of a series of passages in the''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

11

and and associate it with death. And perhaps similarly, associates it with childbirth, and associates it with skin disease. associates it with various sexuality-related events. And

and and associate it with contact with the worship of alien gods.

Numbers chapter 20

An episode in the journey similar to is recorded in when the people complained of thirst and contended with God, Moses struck the rock with his rod to bring forth water, and the place was namedNumbers chapter 21

The defeat of theIn early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:Numbers chapter 19–20

Numbers chapter 21

ProfessorIn classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in theseNumbers chapter 19

Reading and in which God addresses both Moses and Aaron, a''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

The Mishnah and Tosefta taught that if the month of

The Mishnah and Tosefta taught that if the month of  A Midrash taught that an idolater once asked Rabban

A Midrash taught that an idolater once asked Rabban  Noting that “This is the statute (, ''chukat'') of the Law,” uses the same term as “This is the ordinance (, ''chukat'') of the Passover,” a Midrash found the statute of the Passover and the statute of the Red Heifer similar to one another. The Midrash taught that “Let my heart be undivided in your statutes,” refers to this similarity, and asked which statute is greater than the other. The Midrash likened this to the case of two ladies who were walking side by side together apparently on an equal footing; who then is the greater? She whom her friend accompanies to her house and so is really being followed by the friend. The Midrash concluded that the law of the Red Cow is the greater, for those who eat the Passover need the Red Cow's purifying ashes, as says, “And for the unclean they shall take of the ashes of the burning of the purification from sin.”

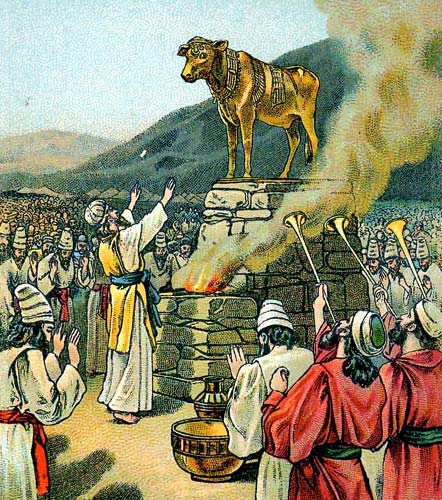

All other communal sacrifices were of male animals, but the Red Cow was of a female animal. Rabbi Aibu explained the difference with a parable: When a handmaiden's boy polluted a king's palace, the king called on the boy's mother to clear away the filth. In the same way, God called on the Red Cow to come and atone for the incident of the

Noting that “This is the statute (, ''chukat'') of the Law,” uses the same term as “This is the ordinance (, ''chukat'') of the Passover,” a Midrash found the statute of the Passover and the statute of the Red Heifer similar to one another. The Midrash taught that “Let my heart be undivided in your statutes,” refers to this similarity, and asked which statute is greater than the other. The Midrash likened this to the case of two ladies who were walking side by side together apparently on an equal footing; who then is the greater? She whom her friend accompanies to her house and so is really being followed by the friend. The Midrash concluded that the law of the Red Cow is the greater, for those who eat the Passover need the Red Cow's purifying ashes, as says, “And for the unclean they shall take of the ashes of the burning of the purification from sin.”

All other communal sacrifices were of male animals, but the Red Cow was of a female animal. Rabbi Aibu explained the difference with a parable: When a handmaiden's boy polluted a king's palace, the king called on the boy's mother to clear away the filth. In the same way, God called on the Red Cow to come and atone for the incident of the  If a cow had two black or white hairs growing within one follicle, it was invalid. Rabbi Judah said even within one hollow. If the hairs grew within two adjacent follicles, the cow was invalid.

If a cow had two black or white hairs growing within one follicle, it was invalid. Rabbi Judah said even within one hollow. If the hairs grew within two adjacent follicles, the cow was invalid.  Rabbi Isaac contrasted the Red Cow in and the bull that the

Rabbi Isaac contrasted the Red Cow in and the bull that the  A Midrash noted that God commanded the Israelites to perform certain precepts with similar material from trees: God commanded that the Israelites throw cedar wood and hyssop into the Red Cow mixture of and use hyssop to sprinkle the resulting waters of lustration in God commanded that the Israelites use cedar wood and hyssop to purify those stricken with skin disease in and in Egypt God commanded the Israelites to use the bunch of hyssop to strike the lintel and the two side-posts with blood in Noting that the cedar was among the tallest of tall trees and the hyssop was among the lowest of low plants, the Midrash associated the cedar with arrogance and the hyssop with humility. The Midrash noted that many things appear lowly, but God commanded many precepts to be performed with them. The hyssop, for instance, appears to be of no worth to people, yet its power is great in the eyes of God, who put it on a level with cedar in the purification of the leper in and the burning of the Red Cow in

A Midrash noted that God commanded the Israelites to perform certain precepts with similar material from trees: God commanded that the Israelites throw cedar wood and hyssop into the Red Cow mixture of and use hyssop to sprinkle the resulting waters of lustration in God commanded that the Israelites use cedar wood and hyssop to purify those stricken with skin disease in and in Egypt God commanded the Israelites to use the bunch of hyssop to strike the lintel and the two side-posts with blood in Noting that the cedar was among the tallest of tall trees and the hyssop was among the lowest of low plants, the Midrash associated the cedar with arrogance and the hyssop with humility. The Midrash noted that many things appear lowly, but God commanded many precepts to be performed with them. The hyssop, for instance, appears to be of no worth to people, yet its power is great in the eyes of God, who put it on a level with cedar in the purification of the leper in and the burning of the Red Cow in18

and employed it in the Exodus from Egypt in Rabbi Isaac noted two red threads, one in connection with the Red Cow in and the other in connection with the scapegoat in the Yom Kippur service of (whic

Mishnah Yoma 4:2

indicates was marked with a red thread). Rabbi Isaac had heard that one required a definite size, while the other did not, but he did not know which was which. Rav Joseph reasoned that because (as Mishnah Yoma 6:6 explains) the red thread of the scapegoat was divided, that thread required a definite size, whereas that of the Red Cow, which did not need to be divided, did not require a definite size.

Mishnah Parah 3:11

ref name=Parah3:1

Mishnah Parah 3:11

in, e.g., ''The Mishnah: A New Translation'', translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 1017–18.) that they wrapped the red thread together with the cedar wood and hyssop. Rav Hanin said in the name of Rav that if the cedar wood and the red thread were merely caught by the flame, they were used validly. They objected to Rav Hanin based on a

To protect against defilement from contact with the dead, they built courtyards over bedrock, and left beneath them a hollow to serve as protection against a grave in the depths. They used to bring pregnant women there to give birth and rear their children in this ritually pure place. They placed doors on the backs of oxen and placed the children upon them with stone cups in their hands. When the children reached the pool of

To protect against defilement from contact with the dead, they built courtyards over bedrock, and left beneath them a hollow to serve as protection against a grave in the depths. They used to bring pregnant women there to give birth and rear their children in this ritually pure place. They placed doors on the backs of oxen and placed the children upon them with stone cups in their hands. When the children reached the pool of in, e.g., ''The Mishnah: A New Translation'', translated by Jacob Neusner, page 1016. They made a causeway from the Temple Mount to the

in, e.g., ''The Mishnah: A New Translation'', translated by Jacob Neusner, page 1017. The Mishnah taught that during the time of the Temple in Jerusalem, all the walls of the Temple were high except the eastern wall. This was so that the priest who burned the Red Cow, while standing on the top of the Mount of Olives, might see the door of the main Temple building when he sprinkled the blood. The Mishnah also taught that in the time of the Temple, there were five gates to the Temple Mount. The Eastern Gate was decorated with a picture of Susa, Shushan, the capital of Parthian Empire, Persia, and through that gate the High Priest would burn the Red Cow and all those attending to it would exit to the Mount of Olives. The Mishnah taught that when the priest had finished the sprinkling, he wiped his hand on the body of the cow, climbed down, and kindled the fire with wood chips. But Rabbi Akiva said that he kindled the fire with dry branches of palm trees. When the cow's carcass burst in the fire, the priest took up a position outside the pit, took hold of the cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet wool, and said to the observers: "Is this cedar wood? Is this hyssop? Is this scarlet wool?" He repeated each question three times, and the observers answered "Yes" three times to each question. The priest then wrapped the cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet wool together with the ends of the wool and cast them into the burning pyre. When the fire burned out, they beat the ashes with rods and then sifted them with sieves. They then divided the ashes into three parts: One part was deposited on the rampart, one on the Mount of Olives, and one was divided among the courses of priests who performed the Temple services in turn. The Mishnah taught that the funding for the Red Cow came out of the appropriation of the chamber. The ramp for the Red Cow came out of the remainder in the chamber. Abba Saul said that the high priests paid for the ramp out of their own funds. Rabbi Meir taught that Moses prepared the first Red Cow ashes, Ezra prepared the second, and five were prepared since then. But the Sages taught that seven were prepared since Ezra. They said that Simeon the Just and Johanan the High Priest prepared two each, and Eliehoenai the son of Hakof, Hanamel the Egyptian, and Ishmael the son of Piabi each prepared one. Reading “And it [the mixture of ash and water] shall be kept for the congregation of the children of Israel,” the Pesikta de-Rav Kahana taught that in this world priests used the water of the Red Cow to make things ritually clean or unclean, but in the Jewish eschatology, World To Come, God will purify Israel, as says, “I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and you shall be clean; from all your uncleannesses, and from all your idols, I cleanse you.” Reading the Mishnah noted that the person who burned the Red Cow (as well as the person who burned the bulls burned pursuant to or and the person who led away the scapegoat pursuant to an

26

rendered unclean the clothes worn while so doing. But the Red Cow (as well as the bull and the scapegoat) did not itself render unclean clothes with which it came in contact. The Mishnah imagined the clothing saying to the person: "Those that render you unclean do not render me unclean, but you render me unclean." Tractate Oholot in the Mishnah and Tosefta interpreted the laws of corpse contamination in Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah counseled

The Mishnah taught that a case of corpse contamination of two things in succession (where one is rendered impure with a seven-day impurity and one being rendered impure with an impurity until the evening) occurs when a person who touches a corpse is rendered impure with a seven-day impurity, as says, "He who touches the corpse of any human being shall be unclean for seven days." The Rabbis considered a corpse to have the highest power to defile, and regarded a corpse as an originating source of impurity, a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah''). Thus the Mishnah taught that a corpse can confer a generating impurity, a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah''), on a person with whom it comes in contact. A "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') requires a seven-day cleansing period. And then a second person who touches the first person who touched the corpse is rendered impure with an impurity lasting until the evening, as says, "the person who touches him shall be unclean until evening." The "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') — in this case, the person who first touched the corpse — can, in turn, confer a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah''), which requires a cleansing period lasting only until sundown. In sum, in this case, the first person acquired a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') from the corpse, and the second person acquired a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah'') from the first person.

Resh Lakish derived from “This is the Torah, when a man shall die in the tent,” that words of Torah are firmly held by one who kills himself for Torah study.

The Mishnah taught that a case of corpse contamination of three things in succession (where two are rendered impure with seven-day impurity and one with an impurity until the evening) occurs when a utensil touching a corpse becomes a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah'') like the corpse, as says, "whoever in the open field touches one that is slain with a sword, or one that died . . . shall be impure seven days," and from the words "slain with a sword," the Rabbis deduced that "a sword is like the one slain" (, ''cherev harei hu kechalal''), and thus a utensil that touches a corpse is a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah'') like the corpse. And another utensil touching this first utensil is rendered impure — a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') — and both utensils acquire a seven-day impurity. But the third thing in this series, whether a person or a utensil, is then rendered impure with an impurity lasting until the evening — a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah'').

And the Mishnah taught that a case of corpse contamination of four things in succession (where three are rendered impure with seven-day impurity and one with impurity until the evening) occurs when a utensil touching a corpse is rendered a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah'') like the corpse, a person touching these utensils is rendered a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah''), and another utensil touching this person is rendered impure with a seven-day impurity — a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') — as the Rabbis read "And you shall wash your clothes on the seventh day, and you shall be clean," to teach that persons who have touched a corpse convey seven-day impurity to utensils. The fourth thing in this series, whether a person or a utensil, is then rendered impure with an impurity lasting until the evening — a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah'').

The Mishnah taught that there are 248 parts in a human body, and each one of these parts can render impure by contact, carrying, or being under the same roof when they have upon them flesh sufficient that they could heal if still connected to a living person. But if they do not have sufficient flesh upon them, these individual parts can render impure only by contact and carrying but cannot render impure by being under the same roof (although a mostly intact corpse does).

Ulla taught that the Rabbis ruled the skin of dead people contaminating so as to prevent people from fashioning their parents' skin into keepsakes. Similarly, the Mishnah taught that the Sadducees mocked the Pharisees, because the Pharisees taught that the Holy Scrolls rendered unclean the hands that touched them, but the books of Homer did not. In response, Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai noted that both the Pharisees and the Sadducees taught that a donkey's bones were clean, yet the bones of Johanan (High Priest), Johanan the High Priest were unclean. The Sadducees replied to Rabban Johanan that the uncleanness of human bones flowed from the love for them, so that people should not make keepsakes out of their parents' bones. Rabban Johanan replied that the same was true of the Holy Scriptures, for their uncleanness flowed from the love for them. Homer's books, which were not as precious, thus did not render unclean the hands that touched them.

Rabbi Akiva interpreted the words "and the clean person shall sprinkle upon the unclean" in to teach that if the sprinkler sprinkled upon an unclean person, the person became clean, but if he sprinkled upon a clean person, the person became unclean. The Gemara explained that Rabbi Akiva's view hinged on the superfluous words "upon the unclean," which must have been put in to teach this. But the Sages held that these effects of sprinkling applied only in the case of things that were susceptible to uncleanness. The Gemara explained that the Rabbis' view could be deduced from the logical proposition that the greater includes the lesser: If sprinkling upon the unclean makes clean, how much more so should sprinkling upon the clean keep clean or make cleaner? And the Gemara said that it is with reference to Rabbi Akiva's position that Solomon said in Ecclesiastes "I said, ‘I will get wisdom,' but it is far from me." That is, even Solomon could not explain it.

Rabbi Joshua ben Kebusai taught that all his days he had read the words "and the clean person shall sprinkle upon the unclean" in and only discovered its meaning from the storehouse of Yavneh. And from the storehouse of Yavneh Rabbi Joshua ben Kebusai learned that one clean person could sprinkle even a hundred unclean persons.

The Mishnah taught that a case of corpse contamination of two things in succession (where one is rendered impure with a seven-day impurity and one being rendered impure with an impurity until the evening) occurs when a person who touches a corpse is rendered impure with a seven-day impurity, as says, "He who touches the corpse of any human being shall be unclean for seven days." The Rabbis considered a corpse to have the highest power to defile, and regarded a corpse as an originating source of impurity, a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah''). Thus the Mishnah taught that a corpse can confer a generating impurity, a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah''), on a person with whom it comes in contact. A "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') requires a seven-day cleansing period. And then a second person who touches the first person who touched the corpse is rendered impure with an impurity lasting until the evening, as says, "the person who touches him shall be unclean until evening." The "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') — in this case, the person who first touched the corpse — can, in turn, confer a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah''), which requires a cleansing period lasting only until sundown. In sum, in this case, the first person acquired a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') from the corpse, and the second person acquired a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah'') from the first person.

Resh Lakish derived from “This is the Torah, when a man shall die in the tent,” that words of Torah are firmly held by one who kills himself for Torah study.

The Mishnah taught that a case of corpse contamination of three things in succession (where two are rendered impure with seven-day impurity and one with an impurity until the evening) occurs when a utensil touching a corpse becomes a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah'') like the corpse, as says, "whoever in the open field touches one that is slain with a sword, or one that died . . . shall be impure seven days," and from the words "slain with a sword," the Rabbis deduced that "a sword is like the one slain" (, ''cherev harei hu kechalal''), and thus a utensil that touches a corpse is a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah'') like the corpse. And another utensil touching this first utensil is rendered impure — a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') — and both utensils acquire a seven-day impurity. But the third thing in this series, whether a person or a utensil, is then rendered impure with an impurity lasting until the evening — a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah'').

And the Mishnah taught that a case of corpse contamination of four things in succession (where three are rendered impure with seven-day impurity and one with impurity until the evening) occurs when a utensil touching a corpse is rendered a "father of fathers of impurity" (, ''avi avot ha-tumah'') like the corpse, a person touching these utensils is rendered a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah''), and another utensil touching this person is rendered impure with a seven-day impurity — a "father of impurity" (, ''av ha-tumah'') — as the Rabbis read "And you shall wash your clothes on the seventh day, and you shall be clean," to teach that persons who have touched a corpse convey seven-day impurity to utensils. The fourth thing in this series, whether a person or a utensil, is then rendered impure with an impurity lasting until the evening — a first-grade impurity (, ''rishon l'tumah'').

The Mishnah taught that there are 248 parts in a human body, and each one of these parts can render impure by contact, carrying, or being under the same roof when they have upon them flesh sufficient that they could heal if still connected to a living person. But if they do not have sufficient flesh upon them, these individual parts can render impure only by contact and carrying but cannot render impure by being under the same roof (although a mostly intact corpse does).

Ulla taught that the Rabbis ruled the skin of dead people contaminating so as to prevent people from fashioning their parents' skin into keepsakes. Similarly, the Mishnah taught that the Sadducees mocked the Pharisees, because the Pharisees taught that the Holy Scrolls rendered unclean the hands that touched them, but the books of Homer did not. In response, Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai noted that both the Pharisees and the Sadducees taught that a donkey's bones were clean, yet the bones of Johanan (High Priest), Johanan the High Priest were unclean. The Sadducees replied to Rabban Johanan that the uncleanness of human bones flowed from the love for them, so that people should not make keepsakes out of their parents' bones. Rabban Johanan replied that the same was true of the Holy Scriptures, for their uncleanness flowed from the love for them. Homer's books, which were not as precious, thus did not render unclean the hands that touched them.

Rabbi Akiva interpreted the words "and the clean person shall sprinkle upon the unclean" in to teach that if the sprinkler sprinkled upon an unclean person, the person became clean, but if he sprinkled upon a clean person, the person became unclean. The Gemara explained that Rabbi Akiva's view hinged on the superfluous words "upon the unclean," which must have been put in to teach this. But the Sages held that these effects of sprinkling applied only in the case of things that were susceptible to uncleanness. The Gemara explained that the Rabbis' view could be deduced from the logical proposition that the greater includes the lesser: If sprinkling upon the unclean makes clean, how much more so should sprinkling upon the clean keep clean or make cleaner? And the Gemara said that it is with reference to Rabbi Akiva's position that Solomon said in Ecclesiastes "I said, ‘I will get wisdom,' but it is far from me." That is, even Solomon could not explain it.

Rabbi Joshua ben Kebusai taught that all his days he had read the words "and the clean person shall sprinkle upon the unclean" in and only discovered its meaning from the storehouse of Yavneh. And from the storehouse of Yavneh Rabbi Joshua ben Kebusai learned that one clean person could sprinkle even a hundred unclean persons.

Numbers chapter 20

Rabbi Ammi taught that the Torah places the account of Miriam's death in immediately after the laws of the Red Cow in to teach that even as the Red Cow provided atonement, so the death of the righteous provides atonement for those whom they leave behind.Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 28ain, e.g., ''Talmud Bavli'', elucidated by Gedaliah Zlotowitz, Michoel Weiner, Noson Dovid Rabinowitch, and Yosef Widroff, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1999), volume 21, page 28a1. Eleazar ben Shammua, Rabbi Eleazar taught that Miriam died with a Divine kiss, just as Moses would. As says, "So Moses the servant of the Lord died ''there'' in the land of Moab by the mouth of the Lord," and says, "And Miriam died ''there''" — both using the word "there" — Rabbi Eleazar deduced that both Moses and Miriam died the same way. Rabbi Eleazar explained that does not say that Miriam died "by the mouth of the Lord" because it would be indelicate to say so. Similarly, the Sages taught that there were six people over whom the Angel of Death had no sway in their demise — Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, Moses, Aaron, and Miriam. Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, as it is written with regard to them, respectively: “With everything,” “from everything,” “everything”; since they were blessed with everything they were certainly spared the anguish of the Angel of Death. Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, as and says with regard to them that they died “by the mouth of the Lord” which indicates that they died with a kiss, and not at the hand of the Angel of Death. And the Sages taught that there were seven people over whom the worm and the maggot had no sway — Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, Moses, Aaron and Miriam, and Benjamin. Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, as it is written with regard to them, respectively: “With everything,” “from everything,” “everything.” Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, as it is written with regard to them: “By the mouth of the Lord.” Rabbi Jose the son of Rabbi Judah taught that three good leaders arose for Israel — Moses, Aaron, and Miriam — and for their sake Providence conferred three good things on Israel — the well that accompanied the Israelites on their journeys for the merit of Miriam, the pillar of cloud for the merit of Aaron, and the manna for the merit of Moses. When Miriam died, the well disappeared, as reports, "And Miriam died there," and immediately thereafter reports, "And there was no water for the congregation." The well returned for the merit of Moses and Aaron. When Moses died, the well, the pillar of cloud, and the manna all disappeared, as reports, "And I cut off the three shepherds in one month." Similarly, a Midrash taught that when the righteous are born, nobody feels the difference, but when they die, everybody feels it. When Miriam was born, nobody felt it, but when she died (as reported in ), the well ceased to exist and all felt her loss. The well made her death known. When Aaron was born, nobody felt it, but when he died and the clouds of glory departed, all felt his loss. The cloud thus made his death known. And when Moses was born, nobody felt it, but when he died, all felt it, because the manna made his death known by ceasing to fall. The Gemara employed to deduce that one may not benefit from a corpse. The Gemara deduced this conclusion from the use of the same word "there" (, ''sham'') both in connection with the cow whose neck was to be broken (, ''ha-eglah ha-arufah'') prescribed in and here in in connection with a corpse. says, "And Miriam died there (, ''sham'')," and says, "And they shall break the cow's neck there (, ''sham'') in the valley." Just as one was prohibited to benefit from the cow, so also one was thus prohibited to benefit from a corpse. And the School of Rabbi Yannai taught that one was prohibited to benefit from the cow because mentions forgiveness (, ''kaper'') in connection with the cow, just as atonement (, ''kaper'') is mentioned in connection with sacrifices (for example in ). (Just as one was prohibited to benefit from sacrifices, so also one was thus prohibited to benefit from the cow.)

A Master taught that as long as the generation of the wilderness continued to die out, there was no Divine communication to Moses (in a direct manner, as describes, "face to face"). For Moses recounted in "So it came to pass, when all the men of war were consumed and dead . . . that the Lord spoke to me." Only then (after those deaths) did the Divine communication to Moses resume. Thus God's address to Moses in may have been the first time that God had spoken to Moses in 38 years.

A Midrash read God's instruction in "bring forth to them water out of the rock; so you shall give the congregation and their cattle drink," to teach that God was considerate of even the Israelites' property — their animals.

The Mishnah counted the well that accompanied the Israelites through the desert in the merit of Miriam, or others say, the well that Moses opened by striking the rock in among ten miraculous things that God created at twilight on the eve of the first Sabbath.

A Midrash interpreted to teach that Moses struck the rock once and small quantities of water began to trickle from the rock, as says, "Behold, He smote the rock, that waters issued." Then the people ridiculed Moses, asking if this was water for sucklings, or babes weaned from milk. So Moses lost his temper and struck the rock "twice; and water came forth abundantly" (in the words of ), overwhelming all those who had railed at Moses, and as says, "And streams overflowed."

Reading God's criticism of Moses in "Because you did not believe in Me," a Midrash asked whether Moses had not previously said worse when in he showed a greater lack of faith and questioned God's powers asking: "If flocks and herds be slain for them, will they suffice them? Or if all the fish of the sea be gathered together for them, will they suffice them?" The Midrash explained by relating the case of a king who had a friend who displayed arrogance towards the king privately, using harsh words. The king did not, however, lose his temper with his friend. Later, the friend displayed his arrogance in the presence of the king's legions, and the king sentenced his friend to death. So also God told Moses that the first offense that Moses committed (in ) was a private matter between Moses and God. But now that Moses had committed a second offense against God in public, it was impossible for God to overlook it, and God had to react, as reports, "To sanctify Me in the eyes of the children of Israel."

A Master taught that as long as the generation of the wilderness continued to die out, there was no Divine communication to Moses (in a direct manner, as describes, "face to face"). For Moses recounted in "So it came to pass, when all the men of war were consumed and dead . . . that the Lord spoke to me." Only then (after those deaths) did the Divine communication to Moses resume. Thus God's address to Moses in may have been the first time that God had spoken to Moses in 38 years.

A Midrash read God's instruction in "bring forth to them water out of the rock; so you shall give the congregation and their cattle drink," to teach that God was considerate of even the Israelites' property — their animals.

The Mishnah counted the well that accompanied the Israelites through the desert in the merit of Miriam, or others say, the well that Moses opened by striking the rock in among ten miraculous things that God created at twilight on the eve of the first Sabbath.

A Midrash interpreted to teach that Moses struck the rock once and small quantities of water began to trickle from the rock, as says, "Behold, He smote the rock, that waters issued." Then the people ridiculed Moses, asking if this was water for sucklings, or babes weaned from milk. So Moses lost his temper and struck the rock "twice; and water came forth abundantly" (in the words of ), overwhelming all those who had railed at Moses, and as says, "And streams overflowed."

Reading God's criticism of Moses in "Because you did not believe in Me," a Midrash asked whether Moses had not previously said worse when in he showed a greater lack of faith and questioned God's powers asking: "If flocks and herds be slain for them, will they suffice them? Or if all the fish of the sea be gathered together for them, will they suffice them?" The Midrash explained by relating the case of a king who had a friend who displayed arrogance towards the king privately, using harsh words. The king did not, however, lose his temper with his friend. Later, the friend displayed his arrogance in the presence of the king's legions, and the king sentenced his friend to death. So also God told Moses that the first offense that Moses committed (in ) was a private matter between Moses and God. But now that Moses had committed a second offense against God in public, it was impossible for God to overlook it, and God had to react, as reports, "To sanctify Me in the eyes of the children of Israel."

Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar taught that Moses and Aaron died because of their sin, as reports God told them, "Because you did not believe in Me . . . you shall not bring this assembly into the land that I have given them." Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar thus taught that had they believed in God, their time would not yet have come to depart from the world.

The Gemara implied that the sin of Moses in striking the rock at Meribah compared favorably to the sin of David. The Gemara reported that Moses and David were two good leaders of Israel. Moses begged God that his sin be recorded, as it is in and and David, however, begged that his sin be blotted out, as says, "Happy is he whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is pardoned." The Gemara compared the cases of Moses and David to the cases of two women whom the court sentenced to be lashed. One had committed an indecent act, while the other had eaten unripe figs of the seventh year in violation of The woman who had eaten unripe figs begged the court to make known for what offense she was being flogged, lest people say that she was being punished for the same sin as the other woman. The court thus made known her sin, and the Torah repeatedly records the sin of Moses.

Resh Lakish taught that Providence punishes bodily those who unjustifiably suspect the innocent. In Moses said that the Israelites "will not believe me," but God knew that the Israelites would believe. God thus told Moses that the Israelites were believers and descendants of believers, while Moses would ultimately disbelieve. The Gemara explained that reports that "the people believed" and reports that the Israelites' ancestor Abraham "believed in the Lord," while reports that Moses "did not believe." Thus, Moses was smitten when in God turned his hand white as snow.

A Midrash employed a parable to explain why God held Aaron as well as Moses responsible when Moses struck the rock, as reports, "and the Lord said to Moses ''and Aaron'': ‘Because you did not believe in Me.'" The Midrash told how a creditor came to take away a debtor's granary and took both the debtor's granary and the debtor's neighbor's granary. The debtor asked the creditor what his neighbor had done to warrant such treatment. Similarly, Moses asked God what Aaron had done to be blamed when Moses lost his temper. The Midrash taught that it on this account that praises Aaron, saying, "And of Levi he said: ‘Urim and Thummim, Your Thummim and your Urim be with your holy one, whom you proved at

Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar taught that Moses and Aaron died because of their sin, as reports God told them, "Because you did not believe in Me . . . you shall not bring this assembly into the land that I have given them." Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar thus taught that had they believed in God, their time would not yet have come to depart from the world.

The Gemara implied that the sin of Moses in striking the rock at Meribah compared favorably to the sin of David. The Gemara reported that Moses and David were two good leaders of Israel. Moses begged God that his sin be recorded, as it is in and and David, however, begged that his sin be blotted out, as says, "Happy is he whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is pardoned." The Gemara compared the cases of Moses and David to the cases of two women whom the court sentenced to be lashed. One had committed an indecent act, while the other had eaten unripe figs of the seventh year in violation of The woman who had eaten unripe figs begged the court to make known for what offense she was being flogged, lest people say that she was being punished for the same sin as the other woman. The court thus made known her sin, and the Torah repeatedly records the sin of Moses.

Resh Lakish taught that Providence punishes bodily those who unjustifiably suspect the innocent. In Moses said that the Israelites "will not believe me," but God knew that the Israelites would believe. God thus told Moses that the Israelites were believers and descendants of believers, while Moses would ultimately disbelieve. The Gemara explained that reports that "the people believed" and reports that the Israelites' ancestor Abraham "believed in the Lord," while reports that Moses "did not believe." Thus, Moses was smitten when in God turned his hand white as snow.

A Midrash employed a parable to explain why God held Aaron as well as Moses responsible when Moses struck the rock, as reports, "and the Lord said to Moses ''and Aaron'': ‘Because you did not believe in Me.'" The Midrash told how a creditor came to take away a debtor's granary and took both the debtor's granary and the debtor's neighbor's granary. The debtor asked the creditor what his neighbor had done to warrant such treatment. Similarly, Moses asked God what Aaron had done to be blamed when Moses lost his temper. The Midrash taught that it on this account that praises Aaron, saying, "And of Levi he said: ‘Urim and Thummim, Your Thummim and your Urim be with your holy one, whom you proved at  A Midrash interpreted the name "Mount Hor" (, ''hor hahar'') in to mean a mountain on top of a mountain, like a small apple on top of a larger apple. The Midrash taught that the Cloud went before the Israelites to level mountains and raise valleys so that the Israelites would not become exhausted, except that God left Mount Sinai for the Divine Presence, Mount Hor for the burial of Aaron, and Mount Nebo for the burial of Moses.

A Midrash noted the use of the verb "take" (, ''kach'') in and interpreted it to mean that God instructed Moses to ''take'' Aaron with comforting words. The Midrash thus taught that Moses comforted Aaron by explaining to him that he would pass his crown on to his son, a fate that Moses himself would not merit.

The Sifre taught that when Moses saw the merciful manner of Aaron's death, Moses concluded that he would want to die the same way. The Sifre taught that God told Aaron to go in a cave, to climb onto a bier, to spread his hands, to spread his legs, to close his mouth, and to close his eyes, and then Aaron died. At that moment, Moses concluded that one would be happy to die that way. And that is why God later told Moses in that Moses would die "as Aaron your brother died on Mount Hor, and was gathered unto his people," for that was the manner of death that Moses had wanted.

A Midrash interpreted the words "all the congregation saw that Aaron was dead" in The Midrash taught that when Moses and Eleazar descended from the mountain without Aaron, all the congregation assembled against Moses and Eleazar and demanded to know where Aaron was. When Moses and Eleazar answered that Aaron had died, the congregation objected that surely the Angel of Death could not strike the one who had withstood the Angel of Death and had restrained him, as reported in "And he stood between the dead and the living and the plague was stayed." The congregation demanded that Moses and Eleazar bring Aaron back, or they would stone Moses and Eleazar. Moses prayed to God to deliver them from suspicion, and God immediately opened the cave and showed the congregation Aaron's body, as reflected by the words of that "all the congregation saw that Aaron was dead."

A Midrash interpreted the name "Mount Hor" (, ''hor hahar'') in to mean a mountain on top of a mountain, like a small apple on top of a larger apple. The Midrash taught that the Cloud went before the Israelites to level mountains and raise valleys so that the Israelites would not become exhausted, except that God left Mount Sinai for the Divine Presence, Mount Hor for the burial of Aaron, and Mount Nebo for the burial of Moses.

A Midrash noted the use of the verb "take" (, ''kach'') in and interpreted it to mean that God instructed Moses to ''take'' Aaron with comforting words. The Midrash thus taught that Moses comforted Aaron by explaining to him that he would pass his crown on to his son, a fate that Moses himself would not merit.

The Sifre taught that when Moses saw the merciful manner of Aaron's death, Moses concluded that he would want to die the same way. The Sifre taught that God told Aaron to go in a cave, to climb onto a bier, to spread his hands, to spread his legs, to close his mouth, and to close his eyes, and then Aaron died. At that moment, Moses concluded that one would be happy to die that way. And that is why God later told Moses in that Moses would die "as Aaron your brother died on Mount Hor, and was gathered unto his people," for that was the manner of death that Moses had wanted.

A Midrash interpreted the words "all the congregation saw that Aaron was dead" in The Midrash taught that when Moses and Eleazar descended from the mountain without Aaron, all the congregation assembled against Moses and Eleazar and demanded to know where Aaron was. When Moses and Eleazar answered that Aaron had died, the congregation objected that surely the Angel of Death could not strike the one who had withstood the Angel of Death and had restrained him, as reported in "And he stood between the dead and the living and the plague was stayed." The congregation demanded that Moses and Eleazar bring Aaron back, or they would stone Moses and Eleazar. Moses prayed to God to deliver them from suspicion, and God immediately opened the cave and showed the congregation Aaron's body, as reflected by the words of that "all the congregation saw that Aaron was dead."

Numbers chapter 21

The Gemara deduced that what the King of Arad heard in was that Aaron had died and that the clouds of glory had dispersed, as the previous verse, reports that "all the congregation saw that Aaron was dead." The King thus concluded that he had received permission to fight the Israelites. The Gemara deduced from the report of that the king of Arad took some Israelites captive that a non-Jew could acquire an Israelite as a slave by an act of possession.Babylonian Talmud Gittin 38ain, e.g., ''Koren Talmud Bavli: Gittin'', commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 21.

Rav Hanin (or some say Rabbi Hanina) read to show that one who wishes to succeed should set aside some of the gains to Heaven. The Gemara thus taught that one who took possession of the property of a proselyte (who died without any Jewish heirs and thus had no legal heirs) should use some of the proceeds of the property to purchase a Torah scroll to be worthy of retaining the rest of the property. Similarly, Rav Sheshet taught that a person should act in a similar manner with a deceased spouse's estate. Rava taught that even a business person who made a large profit should act in a similar manner. Rav Papa taught that one who has found something should act in the same manner. Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, Rav Nahman bar Isaac said even if a person only arranged for the writing of a pair of Tefillin (that would be a sufficient deed).

Rav Hanin (or some say Rabbi Hanina) read to show that one who wishes to succeed should set aside some of the gains to Heaven. The Gemara thus taught that one who took possession of the property of a proselyte (who died without any Jewish heirs and thus had no legal heirs) should use some of the proceeds of the property to purchase a Torah scroll to be worthy of retaining the rest of the property. Similarly, Rav Sheshet taught that a person should act in a similar manner with a deceased spouse's estate. Rava taught that even a business person who made a large profit should act in a similar manner. Rav Papa taught that one who has found something should act in the same manner. Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, Rav Nahman bar Isaac said even if a person only arranged for the writing of a pair of Tefillin (that would be a sufficient deed).

A Midrash taught that of four who made vows, two vowed and profited, and two vowed and lost. The Israelites vowed and profited in and Hannah (Bible), Hannah vowed and profited in Books of Samuel, 1 Samuel Jephthah vowed and lost in and Jacob vowed in and lost (some say in the loss of Rachel in and some say in the disgrace of Dinah in for Jacob's vow in was superfluous, as Jacob had already received God's promise, and therefore Jacob lost because of it).

Rav Assi said in Rabbi Hanina's name that Achan (biblical figure), Achan's confession to Joshua in showed that Achan committed three sacrileges — twice in the days of Moses, including once violating the oath of and once in the days of Joshua. For in Achan said, “I have sinned (implying this time), and thus and thus have I done (implying twice apart from this instance).”

A Midrash taught that of four who made vows, two vowed and profited, and two vowed and lost. The Israelites vowed and profited in and Hannah (Bible), Hannah vowed and profited in Books of Samuel, 1 Samuel Jephthah vowed and lost in and Jacob vowed in and lost (some say in the loss of Rachel in and some say in the disgrace of Dinah in for Jacob's vow in was superfluous, as Jacob had already received God's promise, and therefore Jacob lost because of it).

Rav Assi said in Rabbi Hanina's name that Achan (biblical figure), Achan's confession to Joshua in showed that Achan committed three sacrileges — twice in the days of Moses, including once violating the oath of and once in the days of Joshua. For in Achan said, “I have sinned (implying this time), and thus and thus have I done (implying twice apart from this instance).”

A Midrash taught that according to some authorities, Israel fought Sihon in the month of Elul, celebrated the Festival in Tishri, and after the Festival fought Og. The Midrash inferred this from the similarity of the expression in "And you shall turn in the morning, and go to your tents," which speaks of an act that was to follow the celebration of a Festival, and the expression in "and Og the king of Bashan went out against them, he and all his people." The Midrash inferred that God assembled the Amorites to deliver them into the Israelites' hands, as says, "and the Lord said to Moses: ‘Fear him not; for I have delivered him into your hand." The Midrash taught that Moses was afraid, as he thought that perhaps the Israelites had committed a trespass in the war against Sihon, or had soiled themselves by the commission of some transgression. God reassured Moses that he need not fear, for the Israelites had shown themselves perfectly righteous. The Midrash taught that there was not a mighty man in the world more difficult to overcome than Og, as says, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim."The Midrash told that Og had been the only survivor of the strong men whom Amraphel and his colleagues had slain, as may be inferred from which reports that Amraphel "smote the Rephaim in Ashteroth-karnaim," and one may read to indicate that Og lived near Ashteroth. The Midrash taught that Og was the refuse among the Rephaim, like a hard olive that escapes being mashed in the olive press. The Midrash inferred this from which reports that "there came one who had escaped, and told Abraham, Abram the Hebrew," and the Midrash identified the man who had escaped as Og, as describes him as a remnant, saying, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim." The Midrash taught that Og intended that Abram should go out and be killed. God rewarded Og for delivering the message by allowing him to live all the years from Abraham to Moses, but God collected Og's debt to God for his evil intention toward Abraham by causing Og to fall by the hand of Abraham's descendants. On coming to make war with Og, Moses was afraid, thinking that he was only 120 years old, while Og was more than 500 years old, and if Og had not possessed some merit, he would not have lived all those years. So God told Moses (in the words of ), "fear him not; for I have delivered him into your hand," implying that Moses should slay Og with his own hand. The Midrash noted that in God told Moses to "do to him as you did to Sihon," and reports that the Israelites "utterly destroyed them," but reports, "All the cattle, and the spoil of the cities, we took for a prey to ourselves." The Midrash concluded that the Israelites utterly destroyed the people so as not to derive any benefit from them.

Rabbi Eleazar ben Perata I, Eleazar ben Perata taught that manna counteracted the ill effects of foreign foods on the Israelites. But the Gemara taught after the Israelites complained about the manna in God burdened the Israelites with the walk of three parasangs to get outside their camp to answer the call of nature. And it was then that the command of “And you shall have a paddle among your weapons,” began to apply to the Israelites.

A Midrash taught that according to some authorities, Israel fought Sihon in the month of Elul, celebrated the Festival in Tishri, and after the Festival fought Og. The Midrash inferred this from the similarity of the expression in "And you shall turn in the morning, and go to your tents," which speaks of an act that was to follow the celebration of a Festival, and the expression in "and Og the king of Bashan went out against them, he and all his people." The Midrash inferred that God assembled the Amorites to deliver them into the Israelites' hands, as says, "and the Lord said to Moses: ‘Fear him not; for I have delivered him into your hand." The Midrash taught that Moses was afraid, as he thought that perhaps the Israelites had committed a trespass in the war against Sihon, or had soiled themselves by the commission of some transgression. God reassured Moses that he need not fear, for the Israelites had shown themselves perfectly righteous. The Midrash taught that there was not a mighty man in the world more difficult to overcome than Og, as says, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim."The Midrash told that Og had been the only survivor of the strong men whom Amraphel and his colleagues had slain, as may be inferred from which reports that Amraphel "smote the Rephaim in Ashteroth-karnaim," and one may read to indicate that Og lived near Ashteroth. The Midrash taught that Og was the refuse among the Rephaim, like a hard olive that escapes being mashed in the olive press. The Midrash inferred this from which reports that "there came one who had escaped, and told Abraham, Abram the Hebrew," and the Midrash identified the man who had escaped as Og, as describes him as a remnant, saying, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim." The Midrash taught that Og intended that Abram should go out and be killed. God rewarded Og for delivering the message by allowing him to live all the years from Abraham to Moses, but God collected Og's debt to God for his evil intention toward Abraham by causing Og to fall by the hand of Abraham's descendants. On coming to make war with Og, Moses was afraid, thinking that he was only 120 years old, while Og was more than 500 years old, and if Og had not possessed some merit, he would not have lived all those years. So God told Moses (in the words of ), "fear him not; for I have delivered him into your hand," implying that Moses should slay Og with his own hand. The Midrash noted that in God told Moses to "do to him as you did to Sihon," and reports that the Israelites "utterly destroyed them," but reports, "All the cattle, and the spoil of the cities, we took for a prey to ourselves." The Midrash concluded that the Israelites utterly destroyed the people so as not to derive any benefit from them.

Rabbi Eleazar ben Perata I, Eleazar ben Perata taught that manna counteracted the ill effects of foreign foods on the Israelites. But the Gemara taught after the Israelites complained about the manna in God burdened the Israelites with the walk of three parasangs to get outside their camp to answer the call of nature. And it was then that the command of “And you shall have a paddle among your weapons,” began to apply to the Israelites.

A Midrash explained that God punished the Israelites by means of serpents in because the serpent was the first to speak slander in God cursed the serpent, but the Israelites did not learn a lesson from the serpent's fate, and nonetheless spoke slander. God therefore sent the serpent, who was the first to introduce slander, to punish those who spoke slander.

A Midrash explained that God punished the Israelites by means of serpents in because the serpent was the first to speak slander in God cursed the serpent, but the Israelites did not learn a lesson from the serpent's fate, and nonetheless spoke slander. God therefore sent the serpent, who was the first to introduce slander, to punish those who spoke slander.

Reading the Midrash told that the people realized that they had spoken against Moses and prostrated themselves before him and beseeched him to pray to God on their behalf. The Midrash taught that then immediately reports, “And Moses prayed,” to demonstrate the meekness of Moses, who did not hesitate to seek mercy for them, and also to show the power of repentance, for as soon as they said, “We have sinned,” Moses was immediately reconciled to them, for one who is in a position to forgive should not be cruel by refusing to forgive. In the same strain, reports, “And Abraham prayed to God; and God healed” (after Abimelech had wronged Abraham and asked for forgiveness). And similarly, reports, “And the Lord changed the fortune of Job (biblical figure), Job, when he prayed for his friends” (after they had slandered him). The Midrash taught that when one person wrongs another but then says, “I have sinned,” the victim is called a sinner if the victim does not forgive the offender. For in Samuel told the Israelites, “As for me, far be it from me that I should sin against the Lord in ceasing to pray for you,” and Samuel told them this after they came and said, “We have sinned,” as indicates when it reports that the people said, “Pray for your servants . . . for we have added to all our sins this evil.”

The Mishnah taught that the brass serpent of effected its miraculous cure because when the Israelites directed their thoughts upward and turned their hearts to God they were healed, but otherwise they perished.

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael counted 10 songs in the Tanakh: (1) the one that the Israelites recited at the first Passover in Egypt, as says, "You shall have a song as in the night when a feast is hallowed"; (2) the Song of the Sea, Song of the sea in (3) the one that the Israelites sang at the well in the wilderness, as reports, "Then sang Israel this song: ‘Spring up, O well'"; (4) the one that Moses spoke in his last days, as reports, "Moses spoke in the ears of all the assembly of Israel the words of this song"; (5) the one that Joshua recited, as reports, "Then spoke Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the

Reading the Midrash told that the people realized that they had spoken against Moses and prostrated themselves before him and beseeched him to pray to God on their behalf. The Midrash taught that then immediately reports, “And Moses prayed,” to demonstrate the meekness of Moses, who did not hesitate to seek mercy for them, and also to show the power of repentance, for as soon as they said, “We have sinned,” Moses was immediately reconciled to them, for one who is in a position to forgive should not be cruel by refusing to forgive. In the same strain, reports, “And Abraham prayed to God; and God healed” (after Abimelech had wronged Abraham and asked for forgiveness). And similarly, reports, “And the Lord changed the fortune of Job (biblical figure), Job, when he prayed for his friends” (after they had slandered him). The Midrash taught that when one person wrongs another but then says, “I have sinned,” the victim is called a sinner if the victim does not forgive the offender. For in Samuel told the Israelites, “As for me, far be it from me that I should sin against the Lord in ceasing to pray for you,” and Samuel told them this after they came and said, “We have sinned,” as indicates when it reports that the people said, “Pray for your servants . . . for we have added to all our sins this evil.”

The Mishnah taught that the brass serpent of effected its miraculous cure because when the Israelites directed their thoughts upward and turned their hearts to God they were healed, but otherwise they perished.

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael counted 10 songs in the Tanakh: (1) the one that the Israelites recited at the first Passover in Egypt, as says, "You shall have a song as in the night when a feast is hallowed"; (2) the Song of the Sea, Song of the sea in (3) the one that the Israelites sang at the well in the wilderness, as reports, "Then sang Israel this song: ‘Spring up, O well'"; (4) the one that Moses spoke in his last days, as reports, "Moses spoke in the ears of all the assembly of Israel the words of this song"; (5) the one that Joshua recited, as reports, "Then spoke Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these Middle Ages, medieval Jewish sources:

Numbers chapter 19

The Zohar taught that “a red heifer, faultless, wherein is no blemish, and upon which never came yoke,” epitomized the four Kingdoms foretold in The “heifer” is Israel, of whom says, “For Israel is stubborn like a stubborn heifer.” “Red” indicates Babylonia, regarding which says, “you are the head of gold.” “Faultless” points to Medes, Media (an allusion to Cyrus the Great, who liberated the History of the Jews in Iraq, Babylonian Jews). “Wherein is no blemish” indicates Ancient Greece, Greece (who were near the true faith). And “upon which never came yoke” alludes to Edom, that is, Ancient Rome, Rome, which was never under the yoke of any other power. Maimonides taught that nine red heifers were offered from the time that the Israelites were commanded to fulfill the commandment until the time when the Temple was destroyed a second time. Moses brought the first, Ezra brought the second, seven others were offered until the destruction of the Second Temple, and the Messiah in Judaism, Messiah will bring the tenth.

Maimonides taught that nine red heifers were offered from the time that the Israelites were commanded to fulfill the commandment until the time when the Temple was destroyed a second time. Moses brought the first, Ezra brought the second, seven others were offered until the destruction of the Second Temple, and the Messiah in Judaism, Messiah will bring the tenth.

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Numbers chapter 19

Reflecting the uncleanness that dead bodies convey (as discussed in ), the ''Kitzur Shulchan Aruch'' required one to wash one's hands after leaving a cemetery, attending a funeral, or entering a covered area in which a dead person lay.Numbers chapter 20

Dean Ora Horn Prouser of the Academy for Jewish Religion (New York), Academy for Jewish Religion noted that in before hitting the rock, Moses cried “Listen, you rebels!” using a word for “rebels,” , ''morim'', that appears nowhere else in the Bible in this form, but which in its unvocalized form is identical with the name Miriam, . Horn Prouser suggested that this verbal coincidence may intimate that Moses’ behavior had as much to do with the loss of Miriam reported in as with his frustration with the Israelite people. Horn Prouser suggested that when faced with the task of producing water, Moses recalled his older sister, his co-leader, and the clever caretaker who guarded him at the Nile.

Numbers chapter 21

Archaeology, Archeologists Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University and Neil Asher Silberman noted that recounts how the Canaanite king of Arad, “who dwelt in the Negeb,” attacked the Israelites and took some of them captive — enraging them so that they appealed for Divine assistance to destroy all the Canaanite cities. Finkelstein and Silberman reported that almost 20 years of intensive excavations at Tel Arad east of Beersheba have revealed remains of a great Early Bronze Age city, about 25 acres in size, and an Iron Age fort, but no remains whatsoever from the Late Bronze Age, when the place was apparently deserted. Finkelstein and Silberman reported the same holds true for the entire Beersheba valley. Arad did not exist in the Late Bronze Age. Finkelstein and Silberman reported that the same situation is evident eastward across the Jordan, where and report that the wandering Israelites battled at the city of Heshbon, capital of Sihon, king of the Amorites, who tried to block the Israelites from passing through his territory on their way to Canaan. Excavations at Tel Hesban south of Amman, the location of ancient Heshbon, showed that there was no Late Bronze city, not even a small village, there. And Finkelstein and Silberman noted that according to the Bible, when the children of Israel moved along the Transjordanian plateau they met and confronted resistance not only in Moab but also from the full-fledged states of Edom and Ammon. Yet the archeological evidence indicates that the Transjordan plateau was very sparsely inhabited in the Late Bronze Age, and most parts of the region, including Edom, mentioned as a state ruled by a king, were not even inhabited by a sedentary population at that time, and thus no kings of Edom could have been there for the Israelites to meet. Finkelstein and Silberman concluded that sites mentioned in the Exodus narrative were unoccupied at the time they reportedly played a role in the events of the Israelites wanderings in the wilderness, and thus a mass Exodus did not happen at the time and in the manner described in the Bible.Commandments

According to Maimonides

Maimonides cited a verse in the parashah for 1 positive Mitzvah, commandment: *To prepare a Red Cow so that its ashes are readyAccording to Sefer ha-Chinuch

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 3 positive commandments in the parashah: *The precept of the Red Cow *The precept of the ritual uncleanness of the dead *The precept of the lustral water, that it defiles a ritually clean person and purifies only one defined by the deadIn the liturgy

The people's murmuring and perhaps the rock that yielded water at Meribah of are reflected in which is in turn the first of the six Psalms recited at the beginning of the Kabbalat Shabbat Jewish services, prayer service.

Haftarah

Generally

The haftarah for the parashah is Both the parashah and the haftarah involve diplomatic missions about land issues. In the parashah, Moses sent messengers and tried to negotiate passage over the lands of the Edomites and the Amorites of Sihon. In the haftarah, Jephthah sent messengers to the Ammonites prior to hostilities over their land. In the course of Jephthah's message to the Ammonites, he recounted the embassies described in the parashah. And Jephthah's also recounted the Israelites' victory over the Amorites described in the parashah. Both the parashah and the haftarah involve vows. In the parashah, the Israelites vowed that if God delivered the Canaanites of Arad into their hands, then the Israelites would utterly destroy their cities. In the haftarah, Jephthah vowed that if God would deliver the Ammonites into his hand, then Jephthah would offer as a burnt-offering whatever first came forth out of his house to meet him when he returned. The haftarah concludes just before the verses that report that Jephthah's daughter was first to greet him, proving his vow to have been improvident.For parashah Chukat–Balak

When parashah Chukat is combined with parashah Balak (as it is in 2020, 2023, 2026, and 2027), the haftarah is the haftarah for Balak,For Shabbat Rosh Chodesh

When parashah Chukat coincides with Shabbat Rosh Chodesh, the haftarah isNotes

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:Ancient

*Ritual To Be Followed by the ''Kalu''-Priest when Covering the Temple Kettle-Drum. In James B. Pritchard, ''Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament'', 334–38. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. .Biblical

*49–52

(cedar wood, hyssop, and red stuff). * *Books of Kings, 2 Kings (bronze serpent). * (purge with hyssop);

20

(water from rock; they remembered that God was their Rock); (Meribah); (songs to God); (Meribah); (Sihon); (Sihon).

Early nonrabbinic

*First Epistle to the Corinthians, 1 Corinthians ("they drank of that spiritual Rock that followed them"). Circa 53–57. *4:4:5–7

Circa 93–94. In, e.g., ''The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition''. Translated by William Whiston, pages 107–08. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. . *Epistle to the Hebrews, Hebrews (Red Cow); (scarlet wool and hyssop). Late 1st Century. *Gospel of John, John (serpent); (hyssop). *Quran s:Quran/2#62-71, 2:67–73 (command to slaughter a cow).

Classical rabbinic

*Shekalim 4:2

s:Mishnah/Seder Moed/Tractate Yoma/Chapter 6/6, 6:6

Rosh Hashanah 3:8

s:Mishnah/Seder Nezikin/Tractate Avot/Chapter 5/6, Avot 5:6

Zevachim 14:1

Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. In, e.g., ''The Mishnah: A New Translation''. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 256, 270–71, 275–76, 304–05, 320–21, 686, 729, 836, 876, 950–81, 1012–35, 1130. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. . *

4:6

Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Genesis''. Translated by Harry Freedman (rabbi), Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 31–32, 37, 242, 330, 350, 411, 431, 469, 480; volume 2, pages 529, 636–37, 641, 661, 701, 799, 977. London: Soncino Press, 1939. . *Leviticus Rabbah. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus''. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 1, 134, 207, 283, 328–29, 378, 393. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Babylonian

*Babylonian Berakhot 19b

Babylonia, 6th Century. In, e.g., ''Talmud Bavli''. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006. *Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah, Song of Songs Rabbah. 6th–7th centuries. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Song of Songs''. Translated by Maurice Simon, volume 9, pages 28, 56, 72, 147, 200, 223, 289, 320. London: Soncino Press, 1939. . *Ruth Rabbah. 6th–7th centuries. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Ruth''. Translated by L. Rabinowitz, volume 8, page 8. London: Soncino Press, 1939. . *Ecclesiastes Rabbah 7:4, 23. 6th–8th centuries. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Ecclesiastes''. Translated by Maurice Simon, volume 8, pages 33, 60, 133, 144, 171, 208, 216–17, 288. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

Medieval

*Avot of Rabbi Natan, 12:1; 29:7; 34:6; 36:4. Circa 700–900 C.E. In, e.g., ''The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan.'' Translated by Judah Goldin, pages 64, 120, 139, 150. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955. . ''The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan: An Analytical Translation and Explanation.'' Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 89, 179, 205, 217. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986. .

*Deuteronomy Rabbah. Land of Israel, 9th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy/Lamentations''. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 7, pages 7, 16, 31, 36, 59, 76, 181. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Exodus Rabbah. 10th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Exodus''. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 25, 31, 73, 211, 231, 260, 302, 307, 312, 359, 404, 448, 492. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Lamentations Rabbah. 10th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy/Lamentations''. Translated by A. Cohen, volume 7, pages 17, 145, 166, 207, 239. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Rashi. ''Commentary''

*Avot of Rabbi Natan, 12:1; 29:7; 34:6; 36:4. Circa 700–900 C.E. In, e.g., ''The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan.'' Translated by Judah Goldin, pages 64, 120, 139, 150. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955. . ''The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan: An Analytical Translation and Explanation.'' Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 89, 179, 205, 217. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986. .

*Deuteronomy Rabbah. Land of Israel, 9th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy/Lamentations''. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 7, pages 7, 16, 31, 36, 59, 76, 181. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Exodus Rabbah. 10th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Exodus''. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 25, 31, 73, 211, 231, 260, 302, 307, 312, 359, 404, 448, 492. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Lamentations Rabbah. 10th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy/Lamentations''. Translated by A. Cohen, volume 7, pages 17, 145, 166, 207, 239. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Rashi. ''Commentary''Numbers 19–22.

Troyes, France, late 11th Century. In, e.g., Rashi. ''The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated''. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 4, pages 225–68. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. .

*Rashbam. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., ''Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation''. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 247–61. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001. .

*Yehuda Halevi, Judah Halevi. ''Kuzari''. s:Kitab al Khazari/Part Three, 3:53. Toledo, Spain, Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. In, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. ''Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel.'' Introduction by Henry Slonimsky, page 181. New York: Schocken, 1964. .

*Numbers Rabbah 19:1–33. 12th Century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Numbers''. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 2, 4, 92, 269, 271; volume 6, pages 486, 511, 532, 573, 674, 693, 699, 732, 745–85, 788, 794, 810, 820, 831, 842. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Abraham ibn Ezra. ''Commentary'' on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., ''Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar)''. Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, pages 152–77. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999. .

*Rashbam. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., ''Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation''. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 247–61. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001. .

*Yehuda Halevi, Judah Halevi. ''Kuzari''. s:Kitab al Khazari/Part Three, 3:53. Toledo, Spain, Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. In, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. ''Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel.'' Introduction by Henry Slonimsky, page 181. New York: Schocken, 1964. .

*Numbers Rabbah 19:1–33. 12th Century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Numbers''. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 2, 4, 92, 269, 271; volume 6, pages 486, 511, 532, 573, 674, 693, 699, 732, 745–85, 788, 794, 810, 820, 831, 842. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Abraham ibn Ezra. ''Commentary'' on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., ''Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar)''. Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, pages 152–77. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999. .

*Maimonides. ''Mishneh Torah

*Maimonides. ''Mishneh TorahHilchot Tum'at Meit (The Laws of Impurity from the Dead)

' an

Egypt. Circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., ''Mishneh Torah: Sefer Taharah I''. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 12–305. New York: Moznaim Publishing Corporation, 2009. . *Maimonides. ''The Guide for the Perplexed'', s:The Guide for the Perplexed (Friedlander)/Part I#CHAPTER XV, part 1, chapter 15; s:The Guide for the Perplexed (Friedlander)/Part II#CHAPTER VI, part 2, chapters 6, s:The Guide for the Perplexed (Friedlander)/Part II#CHAPTER XLII, 42; s:Page:Guideforperplexed.djvu/424, part 3, chapters 43, s:Page:Guideforperplexed.djvu/438, 47, s:Page:Guideforperplexed.djvu/453, 50. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. In, e.g., Moses Maimonides. ''The Guide for the Perplexed''. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 26, 160, 237, 354, 368, 370, 383. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. . *Hezekiah ben Manoah. ''Hizkuni''. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. ''Chizkuni: Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 951–79. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. .

*Nahmanides, Nachmanides. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., ''Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Numbers.'' Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 4, pages 194–244. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1975. .

*Zohar, part 3, pages 179a–184b. Spain, late 13th Century. In, e.g., ''The Zohar''. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

*Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). ''Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim''. Early 14th century. In, e.g., ''Baal Haturim Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers''. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 4, pages 1581–617. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003. .

*Jacob ben Asher. ''Perush Al ha-Torah''. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. ''Tur on the Torah''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1121–51. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005. .

*Isaac ben Moses Arama. ''Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac)''. Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. ''Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah''. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 741–62. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001. .

*Nahmanides, Nachmanides. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., ''Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Numbers.'' Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 4, pages 194–244. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1975. .

*Zohar, part 3, pages 179a–184b. Spain, late 13th Century. In, e.g., ''The Zohar''. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

*Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). ''Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim''. Early 14th century. In, e.g., ''Baal Haturim Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers''. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 4, pages 1581–617. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003. .

*Jacob ben Asher. ''Perush Al ha-Torah''. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. ''Tur on the Torah''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1121–51. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005. .

*Isaac ben Moses Arama. ''Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac)''. Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. ''Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah''. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 741–62. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001. .

Modern