Restorationism (or Restitutionism or Christian primitivism) is the belief that

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

has been or should be restored along the lines of what is known about the

apostolic early church, which restorationists see as the search for a purer and more ancient form of the religion.

Fundamentally, "this vision seeks to correct faults or deficiencies (in the church) by appealing to the primitive church as a normative model."

Efforts to restore an earlier, purer form of Christianity are often a response to

denominationalism

A religious denomination is a subgroup within a religion that operates under a common name and tradition among other activities.

The term refers to the various Christian denominations (for example, Eastern Orthodox, Catholic, and the many variet ...

. As

Rubel Shelly

Dr. Rubel Shelly is an author, minister, and professor at Lipscomb University. He is the former president of Rochester University .

Life

Shelly began as an instructor in the department of Religion and Philosophy at Freed-Hardeman University in 19 ...

put it, "the motive behind all restoration movements is to tear down the walls of separation by a return to the practice of the original, essential and universal features of the Christian religion."

Different groups have tried to implement the restorationist vision in a variety of ways; for instance, some have focused on the structure and practice of the church, others on the

ethical life of the church, and others on the direct experience of the

Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

in the life of the believer.

The relative importance given to the restoration ideal, and the extent to which the full restoration of the early church is believed to have been achieved, also varies among groups.

More narrowly, the term "Restorationism" describes unrelated Restorationist groups emerging after the

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

, such as the

Christadelphians

The Christadelphians () or Christadelphianism are a restorationist and millenarian Christian group who hold a view of biblical unitarianism. There are approximately 50,000 Christadelphians in around 120 countries. The movement developed in the U ...

,

Latter Day Saints

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by Jo ...

,

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

,

La Luz del Mundo

The Iglesia del Dios Vivo, Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo (; English: "Church of the Living God, Pillar and Ground of the Truth, The Light of the World")or simply La Luz del Mundo (LLDM)is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian C ...

, and

Iglesia ni Cristo.

In this sense, Restorationism has been regarded as one of the six taxonomic groupings of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

: the

Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

,

Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent ...

,

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first m ...

,

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

,

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, and Restorationism.

These Restorationist groups share a belief that historic Christianity lost the true faith during the

Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy is a concept within Christianity to describe a perception that mainstream Christian Churches have fallen away from the original faith founded by Jesus and promulgated through his twelve Apostles.

A belief in a Great Apostasy ...

and that the Church needed to be restored.

The term has been used to refer to the

Stone–Campbell Movement in the United States,

and has been also used by more recent groups, describing their goal to re-establish Christianity in its original form, such as some anti-denominational

Charismatic Restorationists, which arose in the 1970s in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

Uses of the term

The terms ''restorationism'', ''restorationist'' and ''restoration'' are used in several senses within

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

. "Restorationism" in the sense of "Christian primitivism" refers to the attempt to correct perceived shortcomings of the current church by using the

primitive church

The history of Christianity concerns the Christian religion, Christian countries, and the Christians with their various denominations, from the 1st century to the present. Christianity originated with the ministry of Jesus, a Jewish teache ...

as a model to reconstruct

early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

,

[Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, ''The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ'', Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, , 9780802838988, entry on ''Restoration, Historical Models of''] and has also been described as "practicing church the way it is perceived to have been done in the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

".

Restorationism is called "apostolic" as representing the form of Christianity that the

twelve Apostles

In Christian theology and ecclesiology, the apostles, particularly the Twelve Apostles (also known as the Twelve Disciples or simply the Twelve), were the primary disciples of Jesus according to the New Testament. During the life and minist ...

followed. These themes arise early in church history, first appearing in the works of

Iranaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France

France (), offici ...

,

and appeared in

some movements during the Middle Ages. It was expressed to varying degrees in the theology of the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

,

and

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

has been described as "a form of Christian restorationism, though some of its forms – for example the

Churches of Christ

The Churches of Christ is a loose association of autonomous Christian congregations based on the ''sola scriptura'' doctrine. Their practices are based on Bible texts and draw on the early Christian church as described in the New Testament.

T ...

or the

Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

– are more restorationist than others". A number of historical movements within Christianity may be described as "restoration movements", including the

Glasite

The Glasites or Glassites were a small Christian church founded in about 1730 in Scotland by John Glas.John Glas preached supremacy of God's word (Bible) over allegiance to Church and state to his congregation in Tealing near Dundee in July 172 ...

s in Scotland and England, the independent church led by

James Haldane

The Rev James Alexander Haldane aka Captain James Haldane (14 July 1768 – 8 February 1851) was a Scottish independent church leader following an earlier life as a sea captain.

Biography

The youngest son of Captain James Haldane of Airth ...

and

Robert Haldane

Robert Haldane (28 February 1764 – 12 December 1842) was a religious writer and Scottish theologian. Author of ''Commentaire sur l'Épître aux Romains, On the Inspiration of Scripture'' and ''Exposition of the Epistle to the Romans.''

Early ...

in Scotland, the American

Restoration Movement

The Restoration Movement (also known as the American Restoration Movement or the Stone–Campbell Movement, and pejoratively as Campbellism) is a Christian movement that began on the United States frontier during the Second Great Awakening (179 ...

, the

Landmark Baptists and the

Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

. A variety of more contemporary movements have also been described as "restorationist". Restorationism has been described as a basic component of some

Pentecostal

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement movements such as the

Assemblies of God

The Assemblies of God (AG), officially the World Assemblies of God Fellowship, is a group of over 144 autonomous self-governing national groupings of churches that together form the world's largest Pentecostal denomination."Assemblies of God". ...

. The terms "Restorationism movement" and "Restorationist movement" have also been applied to the

British New Church Movement The British New Church Movement (BNCM) is a neocharismatic evangelical Christian movement. Its origin is associated with the Charismatic Movement of the 1960s, although it both predates it and has an agenda that goes beyond it. It was originally kno ...

.

Capitalized, the term is also used as a synonym for the American

Restoration Movement

The Restoration Movement (also known as the American Restoration Movement or the Stone–Campbell Movement, and pejoratively as Campbellism) is a Christian movement that began on the United States frontier during the Second Great Awakening (179 ...

.

[Gerard Mannion and Lewis S. Mudge, ''The Routledge companion to the Christian church'', Routledge, 2008, , 9780415374200, page 634]

The term "restorationism" can also include the belief that the Jewish people must be restored to the

promised land

The Promised Land ( he, הארץ המובטחת, translit.: ''ha'aretz hamuvtakhat''; ar, أرض الميعاد, translit.: ''ard al-mi'ad; also known as "The Land of Milk and Honey"'') is the land which, according to the Tanakh (the Hebrew ...

in fulfillment of biblical prophecy before the

Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

of

Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, names and titles), was ...

. ''Christian restorationism'' is generally used to describe the 19th century movement based on this belief, though the term ''

Christian Zionism

Christian Zionism is a belief among some Christians that the return of the Jews to the Holy Land and the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 were in accordance with Bible prophecy. The term began to be used in the mid-20th century i ...

'' is more commonly used to describe later forms.

"Restorationism" is also used to describe a form of

postmillennialism

In Christian eschatology (end-times theology), postmillennialism, or postmillenarianism, is an interpretation of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation which sees Christ's second coming as occurring ''after'' (Latin ''post-'') the "Millennium", ...

developed during the later half of the 20th century, which was influential among a number of

charismatic

Charisma () is a personal quality of presence or charm that compels its subjects.

Scholars in sociology, political science, psychology, and management reserve the term for a type of leadership seen as extraordinary; in these fields, the term "ch ...

groups and the

British new church movement The British New Church Movement (BNCM) is a neocharismatic evangelical Christian movement. Its origin is associated with the Charismatic Movement of the 1960s, although it both predates it and has an agenda that goes beyond it. It was originally kno ...

.

The term ''primitive'', in contrast with other uses, refers to a basis in scholarship and research into the actual writings of the

church fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

and other historical documents. Since written documents for the underground first-century church are sparse, the primitive church passed down its knowledge verbally. Elements of the primitive Christianity movement reject the

patristic

Patristics or patrology is the study of the early Christian writers who are designated Church Fathers. The names derive from the combined forms of Latin ''pater'' and Greek ''patḗr'' (father). The period is generally considered to run from ...

tradition of the prolific extrabiblical 2nd- and 3rd-century redaction of this knowledge (the

Ante-Nicene Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical pe ...

), and instead attempt to reconstruct primitive church practices as they might have existed in the

Apostolic Age

Christianity in the 1st century covers the formative history of Christianity from the start of the ministry of Jesus (–29 AD) to the death of the last of the Twelve Apostles () and is thus also known as the Apostolic Age. Early Christianity ...

. To do this, they

revive

Revive or Revived may refer to:

* Revival, especially bringing back to life

* Revive (video gaming), resurrecting a defeated character.

Music

* Revive (band), a Christian rock band

* ''Revive'', classical album by Elīna Garanča 2016

* ''Revive' ...

practices found in the Old Testament.

The term ''apostolic'' refers to a nonmainstream, often literal,

apostolic succession

Apostolic succession is the method whereby the ministry of the Christian Church is held to be derived from the apostles by a continuous succession, which has usually been associated with a claim that the succession is through a series of bish ...

or historical lineage tracing back to the Apostles and the

Great Commission

In Christianity, the Great Commission is the instruction of the resurrected Jesus Christ to his disciples to spread the gospel to all the nations of the world. The Great Commission is outlined in Matthew 28:16– 20, where on a mountain i ...

. These restorationist threads are sometimes regarded critically as being

Judaizers

The Judaizers were a faction of the Jewish Christians, both of Jewish and non-Jewish origins, who regarded the Levitical laws of the Old Testament as still binding on all Christians. They tried to enforce Jewish circumcision upon the Gentile c ...

in the

Ebionite

Ebionites ( grc-gre, Ἐβιωναῖοι, ''Ebionaioi'', derived from Hebrew (or ) ''ebyonim'', ''ebionim'', meaning 'the poor' or 'poor ones') as a term refers to a Jewish Christian sect, which viewed poverty as a blessing, that existed durin ...

tradition.

Historical models

The restoration ideal has been interpreted and applied in a variety of ways.

Four general historical models can be identified based on the aspect of early Christianity that the individuals and groups involved were attempting to restore.

These are:

*Ecclesiastical Primitivism;

*Ethical Primitivism;

*Experiential Primitivism;

and

*Gospel Primitivism.

Ecclesiastical primitivism focuses on restoring the ecclesiastical practices of the early church.

Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

,

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

and the

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s all advocated ecclesiastical primitivism.

The strongest advocate of ecclesiastical primitivism in the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

was

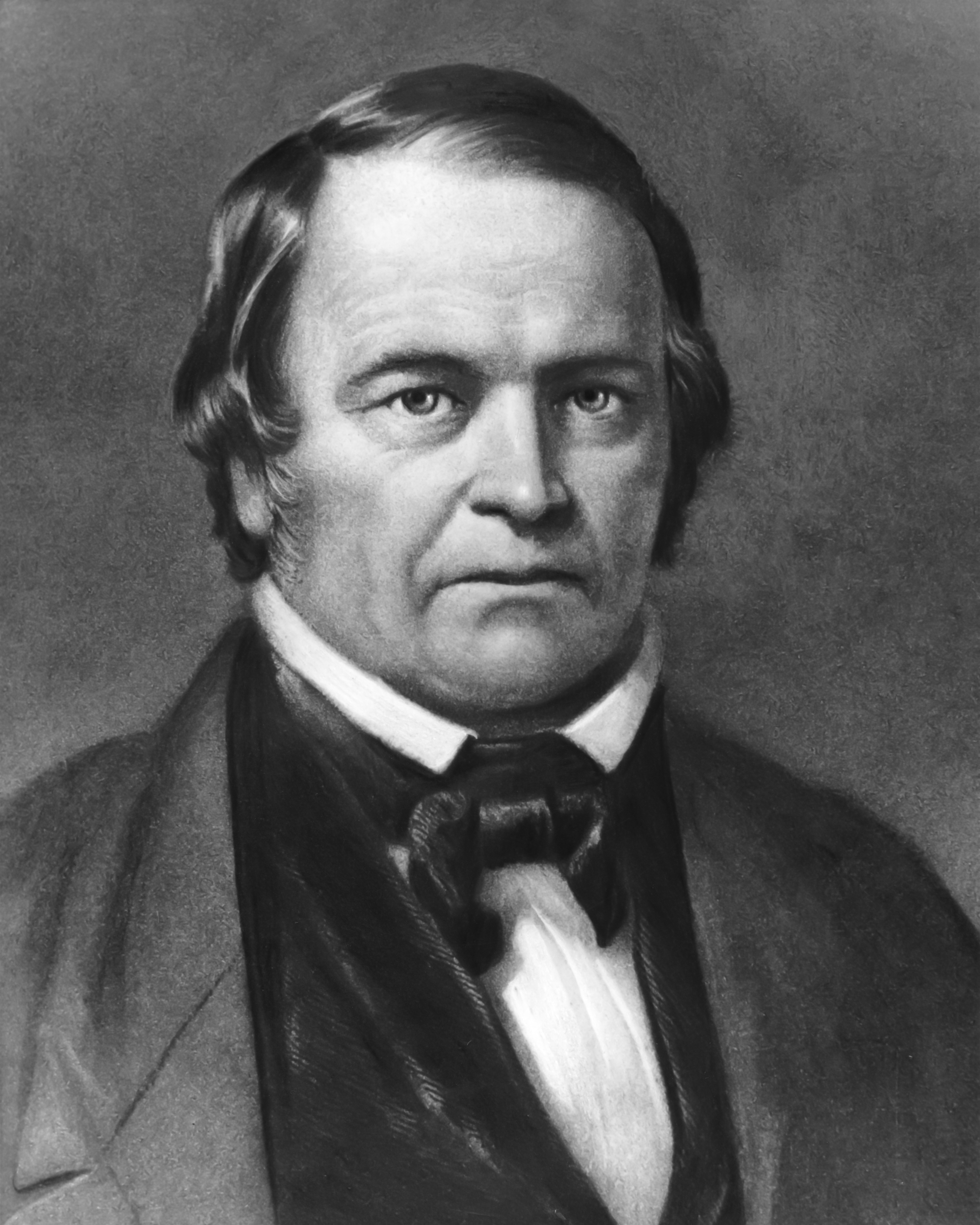

Alexander Campbell.

Ethical primitivism focuses on restoring the ethical norms and commitment to

discipleship

In Christianity, disciple primarily refers to a dedicated follower of Jesus. This term is found in the New Testament only in the Gospels and Acts. In the ancient world, a disciple is a follower or adherent of a teacher. Discipleship is not the ...

of the early church.

The

Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

s,

Barton W. Stone

Barton Warren Stone (December 24, 1772 – November 9, 1844) was an American evangelist during the early 19th-century Second Great Awakening in the United States. First ordained a Presbyterian minister, he and four other ministers of the Washingt ...

and the

Holiness Movement

The Holiness movement is a Christian movement that emerged chiefly within 19th-century Methodism, and to a lesser extent other traditions such as Quakerism, Anabaptism, and Restorationism. The movement is historically distinguished by its emph ...

are examples of this form of restorationism.

The movement often requires observance of universal commandments, such as a

biblical Sabbath

The Sabbath is a weekly day of rest or time of worship given in the Bible as the seventh day. It is observed differently in Judaism and Christianity and informs a similar occasion in several other faiths. Observation and remembrance of Sabbath ...

as given to

Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

in the

Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden ( he, גַּן־עֵדֶן, ) or Garden of God (, and גַן־אֱלֹהִים ''gan-Elohim''), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the Bible, biblical paradise described in Book of Genesis, Genes ...

, and the

Hebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar ( he, הַלּוּחַ הָעִבְרִי, translit=HaLuah HaIvri), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance, and as an official calendar of the state of Israel. I ...

to define years, seasons, weeks, and days.

Circumcision

Circumcision is a surgical procedure, procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin ...

, animal sacrifices, and ceremonial requirements, as practiced in Judaism, are distinguished from the

Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ� ...

,

Noahide laws

In Judaism, the Seven Laws of Noah ( he, שבע מצוות בני נח, ''Sheva Mitzvot B'nei Noach''), otherwise referred to as the Noahide Laws or the Noachian Laws (from the Hebrew pronunciation of "Noah"), are a set of Universal morality, ...

and

High Sabbaths

High Sabbaths, in most Christian and Messianic Jewish usage, are seven annual biblical festivals and rest days, recorded in the books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy. This is an extension of the term "high day" found in the King James Version at .

...

as given to, and in effect for, all humanity. The

Sermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount (anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is ...

and particularly the

Expounding of the Law

Matthew 5 is the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. It contains the first portion of the Sermon on the Mount, the other portions of which are contained in chapters 6 and 7. Portions are similar to the Sermon on the P ...

warn against

antinomianism

Antinomianism (Ancient Greek: ἀντί 'anti''"against" and νόμος 'nomos''"law") is any view which rejects laws or legalism and argues against moral, religious or social norms (Latin: mores), or is at least considered to do so. The term ha ...

, the rejection of biblical teachings concerning observance of the Law.

Experiential primitivism focuses on restoring the direct communication with God and the experience of the

Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

seen in the early church.

Examples include the

Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by Jo ...

of

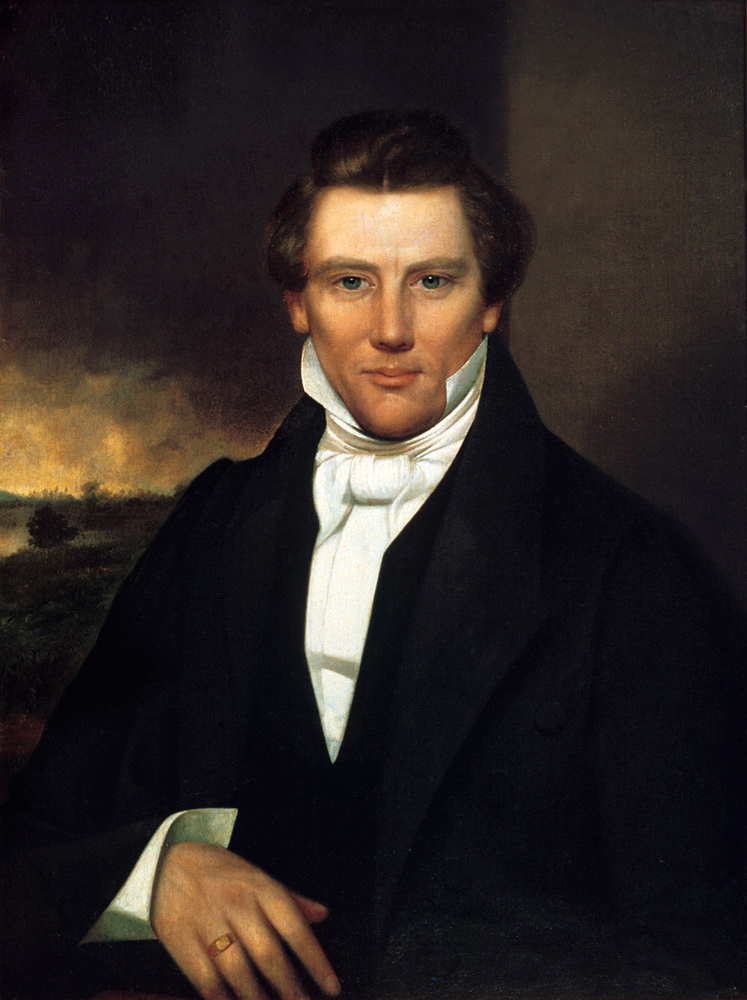

Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

and

Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement .

Gospel primitivism may be best seen in the theology of

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

.

Luther was not, in the strictest sense, a restorationist because he saw human effort to restore the church as

works righteousness

In Christian theology, ''legalism'' (or nomism) is a pejorative term applied to the idea that "by doing good works or by obeying the law, a person earns and merits salvation."

The ''Encyclopedia of Christianity in the United States'' defines '' ...

and was sharply critical of other

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

leaders who were attempting to do so.

On the other hand, he was convinced that the gospel message had been obscured by the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

of the time.

He also rejected church traditions he considered contrary to Scripture and insisted on

scripture as the sole authority for the church.

These models are not mutually exclusive, but overlap; for example, the Pentecostal movement sees a clear link between ethical primitivism and experiential primitivism.

Middle Ages

Beginning in about 1470 a succession of

Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

s focused on the acquisition of money, their role in Italian politics as rulers of the

papal states

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

and power politics within the

college of cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are appoi ...

.

Restorationism

at the time was centered on movements that wanted to renew the church, such as the

Lollards

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

, the

Brethren of the Common Life

The Brethren of the Common Life (Latin: Fratres Vitae Communis, FVC) was a Roman Catholic pietist religious community founded in the Netherlands in the 14th century by Gerard Groote, formerly a successful and worldly educator who had had a religio ...

, the

Hussite

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Hussit ...

s, and

Girolamo Savonarola

Girolamo Savonarola, OP (, , ; 21 September 1452 – 23 May 1498) or Jerome Savonarola was an Italian Dominican friar from Ferrara and preacher active in Renaissance Florence. He was known for his prophecies of civic glory, the destruction of ...

's reforms in

Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

.

While these pre-reformation movements did presage and sometimes discussed a break with Rome and papal authority, they also provoked restorationist movements within the church, such as the councils of Constance and Basle, which were held in the first half of the 15th century.

Preachers at the time regularly harangued delegates to these conferences regarding

simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to imp ...

,

venality

Venality is a vice associated with being bribeable or willing to sell one's services or power, especially when people are intended to act in a decent way instead. In its most recognizable form, venality causes people to lie and steal for their own ...

, lack of

chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when mak ...

and

celibacy

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, the ...

, and the holding of multiple

benefices

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

. The lack of success of the restorationist movements led, arguably, to the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.

Protestant Reformation

The

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

came about through an impulse to repair the Church and return it to what the reformers saw as its original biblical structure, belief, and practice, and was motivated by a sense that "the medieval church had allowed its traditions to clutter the way to God with fees and human regulations and thus to subvert the gospel of Christ."

[C. Leonard Allen and Richard T. Hughes, "Discovering Our Roots: The Ancestry of the Churches of Christ," Abilene Christian University Press, 1988, ] At the heart of the Reformation was an emphasis on the principle of "scripture alone" (

sola scriptura

, meaning by scripture alone, is a Christian theological doctrine held by most Protestant Christian denominations, in particular the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, that posits the Bible as the sole infallible source of au ...

).

As a result, the authority of church tradition, which had taken practical precedence over scripture, was rejected.

The Reformation was not a monolithic movement, but consisted of at least three identifiable sub-currents.

One was centered in

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, one was centered in

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, and the third was centered in

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

.

While these movements shared some common concerns, each had its own particular emphasis.

The

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

approach can be described as one of "reformation," seeking "to reform and purify the historic, institutional church while at the same time preserving as much of the tradition as possible."

The

Lutheran Church

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

es traditionally sees themselves as the "main trunk of the historical Christian Tree" founded by Christ and the Apostles, holding that during the Reformation, the

Church of Rome fell away.

As such, the

Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, ''Confessio Augustana'', is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Protestant Re ...

, the Lutheran confession of faith, teaches that "the faith as confessed by Luther and his followers is nothing new, but the true catholic faith, and that their churches represent the true catholic or universal church".

When the Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession to

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (Crown of Castile, Castil ...

, they explained "that each article of faith and practice was true first of all to Holy Scripture, and then also to the teaching of the church fathers and the councils".

In contrast, the

Reformed

Reform is beneficial change

Reform may also refer to:

Media

* ''Reform'' (album), a 2011 album by Jane Zhang

* Reform (band), a Swedish jazz fusion group

* ''Reform'' (magazine), a Christian magazine

*''Reforme'' ("Reforms"), initial name of the ...

approach can be described as one of "restoration," seeking "to restore the essence and form of the primitive church based on biblical precedent and example; tradition received scant respect."

While

Luther

Luther may refer to:

People

* Martin Luther (1483–1546), German monk credited with initiating the Protestant Reformation

* Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968), American minister and leader in the American civil rights movement

* Luther (give ...

focused on the question "How can we find forgiveness of sins?", the early Reformed theologians turned to the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

for patterns that could be used to replace traditional forms and practices.

Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss Re ...

and

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer ( early German: ''Martin Butzer''; 11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a me ...

in particular emphasized the restoration of biblical patterns.

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

reflected an intermediate position between that of Luther and Reformed theologians such as

Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

, stressing biblical precedents for church governance, but as a tool to more effectively proclaim the

gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

rather than as ends in themselves.

Luther opposed efforts to restore "biblical forms and structures,"

because he saw human efforts to restore the church as works righteousness.

He did seek the "marks of the true church," but was concerned that by focusing on forms and patterns could lead to the belief that by "restoring outward forms alone one has restored the essence."

Thus, Luther believed that restoring the gospel was the first step in renewing the church, rather than restoring biblical forms and patterns.

In this sense, Luther can be described as a gospel restorationist, even though his approach was very different from that of other restorationists.

Protestant groups have generally accepted history as having some "jurisdiction" in Christian faith and life; the question has been the extent of that jurisdiction.

[Richard T. Hughes (editor), ''The American Quest for the Primitive Church'', ]University of Illinois Press

The University of Illinois Press (UIP) is an American university press and is part of the University of Illinois system. Founded in 1918, the press publishes some 120 new books each year, plus 33 scholarly journals, and several electronic project ...

, 1988, 292 pages, A commitment to history and primitivism are not mutually exclusive; while some groups attempt to give full jurisdiction to the primitive church, for others the

apostolic

Apostolic may refer to:

The Apostles

An Apostle meaning one sent on a mission:

*The Twelve Apostles of Jesus, or something related to them, such as the Church of the Holy Apostles

*Apostolic succession, the doctrine connecting the Christian Churc ...

"first times" are given only partial jurisdiction.

Perhaps the most primitivist minded of the Protestant Reformation era were a group of scholars within the Church of England known as the Caroline Divines, who flourished in the 1600's during the reigns of

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

and

Charles II. They regularly appealed to the Primitive Church as the basis for their reforms.

Unlike many other Christian Primitivists, the Church of the England and the Caroline Divines did not subject Scriptural interpretation to individual human reason, but rather to the hermeneutical consensus of the Church Fathers, holding to the doctrine of Prima Scriptura as opposed to Sola Scriptura. Furthermore, they did not hold to the separatist ecclesiology of many primitivist groups, but rather saw themselves as working within the historic established church to return it to its foundation in Scripture and the patristic tradition.

Among the Caroline Divines were men like Archbishop William Laud, Bishop Jeremy Taylor, Deacon Nicholas Ferrar and the Little Gidding Community and others.

First Great Awakening

Methodism

Methodism began in the 1700's as a Christian Primitivist movement within the Church of England. John Wesley and his brother Charles, the founders of the movement, were high church Anglican priests in the vein of the Caroline Divines, who had a deep respect for the Primitive Church, which they generally defined as the Church before the Council Of Nicea. Unlike many other Christian Primitivists, the Wesleys and the early Methodists did not subject Scriptural interpretation to individual human reason, but rather to the hermeneutical consensus of the Ante-Nicene Fathers, holding to a view of authority more akin to Prima Scriptura rather than Sola Scriptura. Furthermore, they did not hold to the separatist ecclesiology of many primitivist groups, but rather saw themselves as working within the historic established church to return it to its foundation in Scripture and the tradition of the pre-Nicene Church. John Wesley very regularly asserted Methodism's commitment to the Primitive Church, saying, "From a child I was taught to love and reverence the Scripture, the oracles of God; and, next to these, to esteem the primitive Fathers, the writers of the first three centuries. Next after the primitive church, I esteemed our own, the Church of England, as the most Scriptural national Church in the world." And, "Methodism, so called, is the old religion, the religion of the Bible, the religion of the primitive Church, the religion of the Church of England." On his epitaph is written, "This GREAT LIGHT arose (By the Singular providence of GOD) To enlighten THESE NATIONS, And to revive, enforce, and defend, The Pure Apostolical DOCTRINES and PRACTICES of THE PRIMITIVE CHURCH…"

Separate Baptists

During the

First Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affecte ...

, a movement developed among the

Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

known as

Separate Baptists

The Separate Baptists were an 18th-century group of Baptists in the United States, primarily in the South, that grew out of the Great Awakening.

The Great Awakening was a religious revival and revitalization of piety among the Christian churche ...

. Two themes of this movement were the rejection of

creed

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) in a form which is structured by subjects which summarize its core tenets.

The ea ...

s and "freedom in the Spirit."

The Separate Baptists saw scripture as the "perfect rule" for the church.

However, while they turned to the Bible for a structural pattern for the church, they did not insist on complete agreement on the details of that pattern.

This group originated in

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, but was especially strong in the

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

where the emphasis on a biblical pattern for the church grew stronger.

In the last half of the 18th century it spread to the western frontier of

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

and

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, where the Stone and Campbell movements would later take root.

The development of the Separate Baptists in the southern frontier helped prepare the ground for the

Restoration Movement

The Restoration Movement (also known as the American Restoration Movement or the Stone–Campbell Movement, and pejoratively as Campbellism) is a Christian movement that began on the United States frontier during the Second Great Awakening (179 ...

, as the membership of both the Stone and Campbell groups drew heavily from among the ranks of the Separate Baptists.

Separate Baptist restorationism also contributed to the development of the

Landmark Baptists in the same area at about the same time as the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement. Under the leadership of

James Robinson Graves

James Robinson Graves (April 10, 1820 – June 26, 1893) was an American Baptist preacher, publisher, evangelist, debater, author, and editor. He is most noted as the original founder of what is now the Southwestern family of companies. Graves was ...

, this group looked for a precise blueprint for the primitive church, believing that any deviation from that blueprint would keep one from being part of the true church.

Groups arising during the Second Great Awakening

The ideal of restoring a "primitive" form of Christianity grew in popularity in the United States after the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

.

This desire to restore a purer form of Christianity played a role in the development of many groups during this period, known as the

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

, including the

Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

,

Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

and

Shakers

The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers, are a Millenarianism, millenarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian sect founded in England and then organized in the Unit ...

.

Several factors made the restoration sentiment particularly appealing during this time period.

*To immigrants in the early 19th century, the land in America seemed pristine, edenic and undefiled - "the perfect place to recover pure, uncorrupted and original Christianity" - and the tradition-bound European churches seemed out of place in this new setting.

*The new American democracy seemed equally fresh and pure, a restoration of the kind of just government that God intended.

*Many believed that the new nation would usher in a new

millennial age

Millennialism (from millennium, Latin for "a thousand years") or chiliasm (from the Greek equivalent) is a belief advanced by some religious denominations that a Golden Age or Paradise will occur on Earth prior to the final judgment and future ...

.

*Independence from the traditional churches of

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

was appealing to many Americans who were enjoying a new political independence.

*A primitive faith based on the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

alone promised a way to sidestep the competing claims of all the many

denominations available and find assurance of being right without the security of an established national church.

Camp meeting

The camp meeting is a form of Protestant Christian religious service originating in England and Scotland as an evangelical event in association with the communion season. It was held for worship, preaching and communion on the American frontier d ...

s fueled the Second Great Awakening, which served as an "organizing process" that created "a religious and educational infrastructure" across the trans-Appalachian frontier that encompassed social networks, a religious journalism that provided mass communication, and church related colleges.

American Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement

The American Restoration Movement aimed to restore the church and sought "the unification of all Christians in a single body patterned after the church of the New Testament."

Rubel Shelly

Dr. Rubel Shelly is an author, minister, and professor at Lipscomb University. He is the former president of Rochester University .

Life

Shelly began as an instructor in the department of Religion and Philosophy at Freed-Hardeman University in 19 ...

, ''I Just Want to Be a Christian'', 20th Century Christian, Nashville, Tennessee 1984, While the Restoration Movement developed from several independent efforts to go back to apostolic Christianity, two groups that independently developed similar approaches to the Christian faith were particularly important to its development.

[Monroe E. Hawley, ''Redigging the Wells: Seeking Undenominational Christianity'', Quality Publications, Abilene, Texas, 1976, (paper), (cloth)] The first, led by

Barton W. Stone

Barton Warren Stone (December 24, 1772 – November 9, 1844) was an American evangelist during the early 19th-century Second Great Awakening in the United States. First ordained a Presbyterian minister, he and four other ministers of the Washingt ...

began at

Cane Ridge

Cane Ridge was the site, in 1801, of a huge camp meeting that drew thousands of people and had a lasting influence as one of the landmark events of the Second Great Awakening, which took place largely in frontier areas of the United States. Th ...

, Bourbon County, Kentucky and called themselves simply ''Christians''. The second began in western Pennsylvania and Virginia (now West Virginia) and was led by

Thomas Campbell Thomas Campbell may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Thomas Campbell (poet) (1777–1844), Scottish poet

* Thomas Campbell (sculptor) (1790–1858), Scottish sculptor

* Thomas Campbell (visual artist) (born 1969), California-based visual artist ...

and his son,

Alexander Campbell; they used the name ''Disciples of Christ''.

The Campbell movement was characterized by a "systematic and rational reconstruction" of the early church, in contrast to the Stone movement which was characterized by radical freedom and lack of dogma.

Despite their differences, the two movements agreed on several critical issues.

Both saw restoring apostolic Christianity as a means of hastening the millennium.

Both also saw restoring the early church as a route to Christian freedom.

And, both believed that unity among Christians could be achieved by using apostolic Christianity as a model.

They were united, among other things, in the belief that

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

is the Christ, the Son of God; that Christians should celebrate the

Lord's Supper

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

on the

first day of each week; and that

baptism of adult believers by immersion in water is a necessary condition for

salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

. Because the founders wanted to abandon all denominational labels, they used the biblical names for the followers of Jesus that they found in the Bible.

[McAlister, Lester G. and Tucker, William E. (1975), Journey in Faith: A History of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) - St. Louis, Chalice Press, ] The commitment of both movements to restoring the early church and to uniting Christians was enough to motivate a union between many in the two movements.

[Richard Thomas Hughes and R. L. Roberts, ''The Churches of Christ'', 2nd Edition, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, , 9780313233128, 345 pages]

With the merger, there was the challenge of what to call the new movement. Clearly, finding a biblical, non-sectarian name was important. Stone wanted to continue to use the name "Christians." Alexander Campbell insisted upon "Disciples of Christ". As a result, both names were used.

[Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, ''The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ'', Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, , 9780802838988, 854 pages, entry on ''Campbell, Alexander'']

The Restoration Movement began during, and was greatly influenced by, the Second Great Awakening.

[Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, ''The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ'', Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, , 9780802838988, 854 pages, entry on ''Great Awakenings''] While the Campbells resisted what they saw as the spiritual manipulation of the camp meetings, the Southern phase of the Awakening "was an important matrix of Barton Stone's reform movement" and shaped the evangelistic techniques used by both Stone and the Campbells.

The Restoration Movement has seen several divisions, resulting in multiple separate groups. Three modern groups originating in the

U.S.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

claim the Stone-Campbell movement as their roots:

Churches of Christ

The Churches of Christ is a loose association of autonomous Christian congregations based on the ''sola scriptura'' doctrine. Their practices are based on Bible texts and draw on the early Christian church as described in the New Testament.

T ...

,

Christian churches and churches of Christ

The group of churches known as the Christian Churches and Churches of Christ is a fellowship of congregations within the Restoration Movement (also known as the Stone-Campbell Movement and the Reformation of the 19th Century) that have no forma ...

, and the

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

. Some see divisions in the movement as the result of the tension between the goals of restoration and ecumenism, with the

churches of Christ

The Churches of Christ is a loose association of autonomous Christian congregations based on the ''sola scriptura'' doctrine. Their practices are based on Bible texts and draw on the early Christian church as described in the New Testament.

T ...

and the

Christian churches and churches of Christ

The group of churches known as the Christian Churches and Churches of Christ is a fellowship of congregations within the Restoration Movement (also known as the Stone-Campbell Movement and the Reformation of the 19th Century) that have no forma ...

resolving the tension by stressing restoration while the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) resolved the tension by stressing ecumenism.

[Leroy Garrett, ''The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement'', College Press, 2002, , 9780899009094, 573 pages] Non-U.S. churches associated with this movement include the

Churches of Christ in Australia

The Churches of Christ in Australia is a Reformed Restorationist denomination. It is affiliated with the Disciples Ecumenical Consultative Council and the World Communion of Reformed Churches.

Key features of the church's worship are the weekly ...

and the

Evangelical Christian Church in Canada

The Evangelical Christian Church (Christian Disciples) as an evangelical Protestant Canadian church body. The Evangelical Christian Church's national office in Canada is in Waterloo, Ontario.

History

The church has its origins in the formal ...

.

[Melton's Encyclopedia of American Religions (2009)]

Christadelphians

Dr.

John Thomas (April 12, 1805 – March 5, 1871), was a devout convert to the Restoration Movement after a shipwreck at sea on his emigration to America brought to focus his inadequate understanding of the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

, and what would happen to him at death. This awareness caused him to devote his life to the study of the Bible and he promoted interpretations of it which were at variance with the mainstream Christian views the

Restoration Movement

The Restoration Movement (also known as the American Restoration Movement or the Stone–Campbell Movement, and pejoratively as Campbellism) is a Christian movement that began on the United States frontier during the Second Great Awakening (179 ...

held. In particular he questioned the nature of man. He held a number of debates with one of the leaders of the movement,

Alexander Campbell, on these topics but eventually agreed to stop because he found the practice bestowed no further practical merits to his personal beliefs and it had the potential to create division. He later determined that salvation was dependent upon having the theology he had developed for baptism to be effective for salvation and published an "Confession and Abjuration" of his previous position on March 3, 1847. He was also

rebaptised.

Following his abjuration and rebaptism he went to

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

on a preaching tour in June 1848 including Reformation Movement churches, Although his abjuration and his disfellowship in America were reported in the British churches magazines certain churches in the movement still allowed him to present his views. Thomas also gained a hearing in Unitarian and Adventist churches through his promotion of the concept of "independence of thought" with regards to interpreting the Bible.

Through a process of creed setting and division the Christadelphian movement emerged with a distinctive set of doctrines incorporating Adventism,

anti-trinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian theology, Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God in Christianity, God is three distinct Hypostasis (philosophy and religion), hypostases or perso ...

, the belief that God is a "substantial and corporeal" being,

objection to military service, a

lay-membership with full participation by all members, and other doctrines consistent with the spirit of the Restorationist movement.

One consequence of objection to military service was the adoption of the name

Christadelphians

The Christadelphians () or Christadelphianism are a restorationist and millenarian Christian group who hold a view of biblical unitarianism. There are approximately 50,000 Christadelphians in around 120 countries. The movement developed in the U ...

to distinguish this small community of believers and to be granted exemption from military service in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

.

Latter Day Saint movement

Adherents to the

Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by Jo ...

believe that founder

Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

was a

prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

of God, chosen to restore the primitive, apostolic church established by Jesus. Like other restorationist groups, members believe that the church and priesthood established by Jesus were

withdrawn from the Earth after the end of the apostolic age and before the

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

in 325. Unlike other reformers, who based their movements on their own interpretations of the Bible, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery held that they were visited by John the Baptist to receive the Aaronic Priesthood. This restoration authorized members to receive

revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

from God in order to restore the original apostolic organization lost after the events of the New Testament.

According to Allen and Hughes, "

group used the language of 'restoration' more consistently and more effectively than did the

atter Day Saints Atter may refer to:

* Ätter, Norse clans, a social group based on common descent

* Atter (Osnabrück), district in the west of Osnabrück, Lower Saxony, Germany

; People

* Tom Atter

* Mahmoud Atter Abdel Fattah

; Other

* Atter Shisha

* Gigantoch ...

... early Mormons seemed obsessed with restoring the ancient church of God."

According to Smith, God

appeared to him in 1820, instructing him that the creeds of the churches of the day were corrupted. In addition to restoring the primitive church, Smith claimed to receive new and ongoing revelations. In 1830, he published ''

The Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, which, according to Latter Day Saint theology, contains writings of ancient prophets who lived on the American continent from 600 BC to AD 421 and during an interlude date ...

'', with

he and witnesses declaring to be a translation through divine means from the

Golden Plates

According to Latter Day Saint belief, the golden plates (also called the gold plates or in some 19th-century literature, the golden bible) are the source from which Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon, a sacred text of the faith. Some acco ...

he obtained from

an angel

"An Angel" is a song by European-American pop group The Kelly Family. It was produced by Kathy Kelly and Hartmut Pfannmüller for their eighth regular studio album ''Over the Hump'' (1994) and features lead vocals by Angelo and Paddy Kelly. Pad ...

. The largest and most well known church in the Latter Day Saint movement is

the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Christianity, Christian church that considers itself to be the Restorationism, restoration of the ...

(LDS Church), followed by

Community of Christ

The Community of Christ, known from 1872 to 2001 as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS), is an American-based international church, and is the second-largest denomination in the Latter Day Saint movement. The churc ...

(formerly RLDS), and

hundreds of other denominations. Members of the LDS Church believe that, in addition to Smith being the first prophet appointed by Jesus in the "latter days", every subsequent

apostle

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

and

church president also serves in the capacity of

prophet, seer and revelator

Prophet, seer, and revelator is an ecclesiastical title used in the Latter Day Saint movement. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is the largest denomination of the movement, and it currently applies the terms to the membe ...

.

Some among the

Churches of Christ

The Churches of Christ is a loose association of autonomous Christian congregations based on the ''sola scriptura'' doctrine. Their practices are based on Bible texts and draw on the early Christian church as described in the New Testament.

T ...

have attributed the restorationist character of the Latter Day Saints movement to the influence of

Sidney Rigdon

Sidney Rigdon (February 19, 1793 – July 14, 1876) was a leader during the early history of the Latter Day Saint movement.

Biography Early life

Rigdon was born in St. Clair Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, on February 19, 1793. He was ...

, who was associated with the Campbell movement in Ohio but left it and became a close friend of Joseph Smith.

[Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, ''The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ'', Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, , 9780802838988, 854 pages, entry on ''Mormonism''] Neither the Mormons nor the early Restoration Movement leaders invented the idea of "restoration"; it was a popular theme of the time that had developed independently of both, and Mormonism and the Restoration Movement represent different expressions of that common theme.

The two groups had very different approaches to the restoration ideal.

The Campbell movement combined it with Enlightenment rationalism, "precluding emotionalism, spiritualism, or any other phenomena that could not be sustained by rational appeals to the biblical text."

The Latter Day Saints combined it with "the spirit of nineteenth-century Romanticism" and, as a result, "never sought to recover the forms and structures of the ancient church as ends in themselves" but "sought to restore the golden age, recorded in both Old Testament and New Testament, when God broke into human history and communed directly with humankind."

Mormons gave priority to current revelation. Primitive observances of "appointed times" like Sabbath were secondary to

continuing revelation

Continuous revelation or continuing revelation is a theological belief or position that God continues to reveal divine principles or commandments to humanity.

In Christian traditions, it is most commonly associated with the Latter Day Saint mo ...

, similarly to the

progressive revelation held by some non-restorationist Christian theologians.

The "

Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy is a concept within Christianity to describe a perception that mainstream Christian Churches have fallen away from the original faith founded by Jesus and promulgated through his twelve Apostles.

A belief in a Great Apostasy ...

", or loss of the original church Jesus established, has been cited with historical evidence of changes in Christian doctrine over time, scriptures prophesying of a coming apostasy before the last days (particularly , and ) and corruption within the early churches that led to the necessity of the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, which is seen as an important step towards the development of protected freedoms and speech required for a full restoration to be possible.

Adventism

Adventism

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher Wil ...

is a

Christian eschatological belief that looks for the imminent

Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

of Jesus to inaugurate the

Kingdom of God

The concept of the kingship of God appears in all Abrahamic religions, where in some cases the terms Kingdom of God and Kingdom of Heaven are also used. The notion of God's kingship goes back to the Hebrew Bible, which refers to "his kingdom" b ...

. This view involves the belief that Jesus will return to receive those who have died in Christ and those who are awaiting his return, and that they must be ready when he returns. Adventists are considered to be both restorationists and

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

.

Millerites and Seventh-day Sabbatarianism

The

Millerites

The Millerites were the followers of the teachings of William Miller, who in 1831 first shared publicly his belief that the Second Advent of Jesus Christ would occur in roughly the year 1843–1844. Coming during the Second Great Awakening, his ...

were the most well-known family of the Adventist movements. They emphasized apocalyptic teachings anticipating the end of the world, and did not look for the unity of

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

but busied themselves in preparation for Christ's return. Millerites sought to restore a prophetic immediacy and uncompromising biblicism that they believed had once existed but had long been rejected by mainstream Protestant and Catholic churches. From the Millerites descended the Seventh-day Adventists and the Advent Christian Church.

Seventh-day Adventists

The

Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

grew out of the Adventist movement, in particular the Millerites. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is the largest of several

Adventist

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher Wil ...

groups which arose from the

Millerite

Millerite is a nickel sulfide mineral, Ni S. It is brassy in colour and has an acicular habit, often forming radiating masses and furry aggregates. It can be distinguished from pentlandite by crystal habit, its duller colour, and general l ...

movement of the 1840s in upstate

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, a phase of the

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

. Important to the Seventh-day Adventist movement is a belief in

progressive revelation, teaching that the Christian life and testimony is intended to be typified by the

Spirit of Prophecy, as explained in the writings of

Ellen G. White