Christ In Islam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christianity and Islam are the two largest religions in the world, with 2.8 billion and 1.9 billion adherents, respectively. Both religions are considered as

Christianity and Islam are the two largest religions in the world, with 2.8 billion and 1.9 billion adherents, respectively. Both religions are considered as

Christianity and Islam are the two largest religions in the world, with 2.8 billion and 1.9 billion adherents, respectively. Both religions are considered as

Christianity and Islam are the two largest religions in the world, with 2.8 billion and 1.9 billion adherents, respectively. Both religions are considered as Abrahamic

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout Abrahamic religious scriptures such as the Bible and the Quran.

Jewish tradition ...

, and are monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfor ...

, originating in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

developed out of Second Temple Judaism

Second Temple Judaism refers to the Jewish religion as it developed during the Second Temple period, which began with the construction of the Second Temple around 516 BCE and ended with the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

The Second Temple p ...

in the 1st century CE. It is founded on the life, teachings, death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

, and resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. In a number of religions, a dying-and-rising god is a deity which dies and is resurrected. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions, whic ...

of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, and those who follow it are called Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

. Islam developed in the 7th century CE. Islam is founded on the teachings of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

, as an expression of surrender to the will of God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

. Those who follow it are called Muslims which means "submitter to God".

Muslims view Christians to be People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

, and also regard them as kafir

Kafir ( ar, كافر '; plural ', ' or '; feminine '; feminine plural ' or ') is an Arabic and Islamic term which, in the Islamic tradition, refers to a person who disbelieves in God as per Islam, or denies his authority, or reject ...

s (unbelievers) committing shirk (polytheism) because of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, and thus, contend that they must be dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

s (religious taxpayers) under Sharia law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the ...

. Christians similarly possess a wide range of views about Islam. The majority of Christians view Islam as a false religion due to the fact that its adherents reject the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, the divinity of Christ

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

, and the Crucifixion

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and consider ...

and Resurrection of Christ

The resurrection of Jesus ( grc-x-biblical, ἀνάστασις τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is the Christianity, Christian belief that God in Christianity, God Resurrection, raised Jesus on the third day after Crucifixion of Jesus, his crucifixion, ...

.

Islam considers Jesus to be the '' al-Masih'' (Arabic for Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

) who was sent to guide the Banī Isrā'īl (Arabic for Children of Israel) with a new revelation: '' al-Injīl'' (Arabic for "the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

"). Christianity also believes Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

to be the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

prophesied in the Hebrew scripture

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''

Christianity and

Christianity and

Hasib Sabbagh: A Legacy of Understanding

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

"I'm Right, You're Wrong, Go to Hell"

– Religions and the meeting of civilization by Bernard Lewis

Islam & Christianity (IRAN & GEORGIA) News Photos

{{Authority control

''

hypostases

Hypostasis, hypostatic, or hypostatization (hypostatisation; from the Ancient Greek , "under state") may refer to:

* Hypostasis (philosophy and religion), the essence or underlying reality

** Hypostasis (linguistics), personification of entities

...

of the Triune God

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, God the Son

God the Son ( el, Θεὸς ὁ υἱός, la, Deus Filius) is the second person of the Trinity in Christian theology. The doctrine of the Trinity identifies Jesus as the incarnation of God, united in essence ( consubstantial) but distinct ...

. Belief in Jesus is a fundamental part of both Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

and Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding '' ʿaqīdah'' (creed). The main schools of Islamic Theology include the Qadariyah, Falasifa, Jahmiyya, Murji'ah, Muʿtazila, Bat ...

.

Christianity and Islam have different sacred scriptures

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pract ...

. The sacred text of Christianity is the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts o ...

while the sacred text of Islam is the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

. Muslims believe that '' al-Injīl'' was distorted or altered to form the Christian New Testament. Christians, on the contrary, do not have a univocal understanding of the Quran, though most believe that it is fabricated or apocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

l work. There are similarities in both texts, such as accounts of the life and works of Jesus and the virgin birth of Jesus

The virgin birth of Jesus is the Christian doctrine that Jesus was conceived by his mother, Mary, through the power of the Holy Spirit and without sexual intercourse. It is mentioned only in and , and the modern scholarly consensus is that t ...

through Mary; yet still, some Biblical and Quranic accounts of these events differ.

Similarities and differences

There are many different opinions in the discussion of whetherMuslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abra ...

and Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

worship the same God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

. The argument that "Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately fr ...

" and "Allah

Allah (; ar, الله, translit=Allāh, ) is the common Arabic word for God. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam. The word is thought to be derived by contraction from '' al- ilāh'', which means "the god", ...

" are referring to the same entity, despite the dissimilar concepts of God involved, is not sound. A greater problem is that "worships x" is what analytic philosophers

Analytic philosophy is a branch and tradition of philosophy using analysis, popular in the Western world and particularly the Anglosphere, which began around the turn of the 20th century in the contemporary era in the United Kingdom, United St ...

, like Peter van Inwage, a leading professor in the philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known Text (literary theo ...

, label an "intensional (as opposed to extensional) context", where the term "x" does not have to refer to anything at all (as in, e.g., "Jason worships Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

"). In an "intensional context" co-referring terms cannot be replaced without affecting the truth value of the statement. For instance, even though "Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandt ...

" may refer to the same entity as "Zeus", still Jason, a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, does not worship Jupiter and may not even be aware of the Roman deity. So it cannot be said that "Abdul," a Muslim, worships Yahweh, even if Yahweh and Allah are co-referring names.

Scriptures

The Christian Bible is made up of theOld Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

and the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

. The Old Testament was written over a period of two millennia prior to the birth of Christ. The New Testament was written in the decades following the death of Christ. Historically, Christians universally believed that the entire Bible was the divinely inspired Word of God. However, the rise of higher criticism during the Enlightenment has led to a diversity of views concerning the authority and inerrancy of the Bible in different denominations. Christians consider the Quran to be a non-divine set of texts.

The Quran dates from the early 7th century, or decades thereafter. Muslims believe it was revealed to Muhammad, gradually over a period of approximately 23 years, beginning on 22 December 609, when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632, the year of his death.''Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths'', Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, page 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers. The Quran assumes familiarity with major narratives recounted in the Jewish and Christian scriptures. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and differs in others. Muslims believe that Jesus was given the Injil (Greek ''evangel'', or ''Gospel'') by Allah and that parts of these teachings were lost or distorted (''tahrif

( ar, تحريف, ) is an Arabic-language term used by some Muslims to refer to the alterations that are believed to have been made to the previous revelations of God—specifically those that make up the '' Tawrat'' (or Torah), the '' Zabur'' ( ...

'') to produce the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

and the Christian ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

. The majority of Muslims consider the Quran to be the only revealed book that has been protected by God from distortion or corruption, being remained unchanged and unedited since the death of Muhammad, though scholars and early Islamic sources reject this traditionalist view.

Jesus

Muslims and Christians both believe that Jesus was born to Mary, avirgin

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

. They both also believe that Jesus is the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

. However, they differ on other key issues regarding Jesus. Christians believe that Jesus was the incarnated Son of God, divine, and sinless. Islam teaches that Jesus was one of the most important prophets of God, but not the Son of God, not divine, and not part of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

. Rather, Muslims believe the creation of Jesus was similar to the creation of Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

( Adem).

Christianity and Islam also differ in their fundamental views related to the crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Cartha ...

and resurrection of Jesus

The resurrection of Jesus ( grc-x-biblical, ἀνάστασις τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is the Christian belief that God raised Jesus on the third day after his crucifixion, starting – or restoring – his exalted life as Christ and Lord. ...

. Christianity teaches that Jesus was condemned to death by the Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , '' synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence 'assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), ...

and the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (; grc-gre, Πόντιος Πιλᾶτος, ) was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of ...

, crucified

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

, and after three days, resurrected. Islam teaches that Jesus was a human prophet who, like the other prophets, tried to bring his people to worship God, termed ''Tawhid

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam (Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single ...

''. Muslims also believe that Jesus was condemned to crucifixion and then miraculously saved from execution, and was raised to the heavens. In Islam, instead of Jesus being crucified, his lookalike was crucified.

Both Christians and Muslims believe in the Second Coming of Jesus. Christianity does not state where will Jesus return, while the Hadith in Islam states that Jesus will return at a white minaret at the east of Damascus (believed to be the Minaret of Isa

The Umayyad Mosque ( ar, الجامع الأموي, al-Jāmiʿ al-Umawī), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus ( ar, الجامع الدمشق, al-Jāmiʿ al-Damishq), located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of the ...

in the Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque ( ar, الجامع الأموي, al-Jāmiʿ al-Umawī), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus ( ar, الجامع الدمشق, al-Jāmiʿ al-Damishq), located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of t ...

), and will pray behind Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad w ...

. Christians believe that Jesus will return to kill the Antichrist and similarly Muslims believe that Jesus will return to kill Dajjal. Many Christians believe that Jesus would then rule for 1,000 years, while Muslims believe Jesus will rule for forty years, marry, have children and will be buried at the Green Dome

The Green Dome ( ar, ٱَلْقُبَّة ٱلْخَضْرَاء, al-Qubbah al-Khaḍrāʾ) is a green-coloured dome built above the tombs of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and the early Rashidun Caliphs Abu Bakr () and Umar (), which used to be ...

.

Muhammad

Muslims believe that Muhammad was a prophet, who received revelations (Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

) by God through the angel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

(''Jibril''), gradually over a period of approximately 23 years, beginning on 22 December 609, when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632, the year of his death. Muslims regard the Quran as the most important miracle of Muhammad, a proof of his prophethood, and the culmination of a series of divine messages that started with the messages revealed to Adam and ended with Muhammad. Muslims also believe that the reference to the Paraclete

Paraclete ( grc, παράκλητος, la, paracletus) means 'advocate' or 'helper'. In Christianity, the term ''paraclete'' most commonly refers to the Holy Spirit.

Etymology

''Paraclete'' comes from the Koine Greek word (). A combination o ...

in the Bible is a prophecy of the coming of Muhammad.

Muslims revere Muhammad as the embodiment of the perfect believer and take his actions and sayings as a model of ideal conduct. Unlike Jesus, who Christians believe was God's son, Muhammad was a mortal, albeit with extraordinary qualities. Today many Muslims believe that it is wrong to represent Muhammad, but this was not always the case. At various times and places pious Muslims represented Muhammad although they never worshiped these images.

During the lifetime of Muhammad, he had many interactions with Christians. One of the first Christians who met Muhammad was Waraqah ibn Nawfal, a Christian priest of ancient Arabia. He was one of the first ''hanif

In Islam, a ( ar, حنيف, ḥanīf; plural: , ), meaning "renunciate", is someone who maintains the pure monotheism of the patriarch Abraham. More specifically, in Islamic thought, renunciates were the people who, during the pre-Islamic peri ...

s'' to believe in the prophecy of Muhammad. Muhammad also met the Najrani Christians and made peace with them. One of the earliest recorded comment of a Christian reaction to Muhammad can be dated to only a few years after Muhammad's death. As stories of the Arab prophet spread to Christian Syria, an old man who was asked about the "prophet who has appeared with the Saracens

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

" responded: "He is false, for the prophets do not come armed with a sword."

God

In Christianity, the most common name of God isYahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately fr ...

. In Islam, the most common name of God is Allah

Allah (; ar, الله, translit=Allāh, ) is the common Arabic word for God. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam. The word is thought to be derived by contraction from '' al- ilāh'', which means "the god", ...

, similar to Eloah in the Old Testament. The vast majority of the world's Christians adhere to the doctrine of the Trinity, which in creedal formulations states that God is three ''hypostases

Hypostasis, hypostatic, or hypostatization (hypostatisation; from the Ancient Greek , "under state") may refer to:

* Hypostasis (philosophy and religion), the essence or underlying reality

** Hypostasis (linguistics), personification of entities

...

'' (the Father

Father is the male parent of a child.

Father may also refer to:

Name

* Daniel Fathers (born 1966), a British actor

* Father Yod (1922–1975), an American owner of one of the country's first health food restaurants

Cinema

* ''Father'' (1966 f ...

, the Son and the Spirit) in one ''ousia

''Ousia'' (; grc, οὐσία) is a philosophical and theological term, originally used in ancient Greek philosophy, then later in Christian theology. It was used by various ancient Greek philosophers, like Plato and Aristotle, as a primary d ...

'' (substance). In Islam, this concept is deemed to be a denial of monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxf ...

, and thus a sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, ...

of shirk, which is considered to be a major 'al-Kaba'ir' sin. The Quran itself refers to Trinity in Al-Ma'ida 5:73 which says "''They have certainly disbelieved who say, "Allah is the third of three." And there is no god except one God. And if they do not desist from what they are saying, there will surely afflict the disbelievers among them a painful punishment''." Islam has the concept of Tawhid

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam (Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single ...

which is the concept of a single, indivisible God, who has no partners.

The Holy Spirit

Christians and Muslims have differing views about the Holy Spirit. Most Christians believe that the Holy Spirit is God, and the third member of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit is generally believed to be the angelGabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

. Most Christians believe that the Paraclete

Paraclete ( grc, παράκλητος, la, paracletus) means 'advocate' or 'helper'. In Christianity, the term ''paraclete'' most commonly refers to the Holy Spirit.

Etymology

''Paraclete'' comes from the Koine Greek word (). A combination o ...

referred to in the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "sig ...

, who was manifested on the day of Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christian holiday which takes place on the 50th day (the seventh Sunday) after Easter Sunday. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers o ...

, is the Holy Spirit. Most Muslims believe that the reference to the Paraclete

Paraclete ( grc, παράκλητος, la, paracletus) means 'advocate' or 'helper'. In Christianity, the term ''paraclete'' most commonly refers to the Holy Spirit.

Etymology

''Paraclete'' comes from the Koine Greek word (). A combination o ...

is a prophecy of the coming of Muhammad.

One of the key verses concerning the Paraclete is John 16:7:

Salvation

TheCatechism of the Catholic Church

The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' ( la, Catechismus Catholicae Ecclesiae; commonly called the ''Catechism'' or the ''CCC'') is a catechism promulgated for the Catholic Church by Pope John Paul II in 1992. It aims to summarize, in book ...

, the official doctrine document released by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, has this to say regarding Muslims:

Protestant theology mostly emphasizes the necessity of faith in Jesus as a savior in order for salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

. Muslims may receive salvation in theologies relating to Universal reconciliation

In Christian theology, universal reconciliation (also called universal salvation, Christian universalism, or in context simply universalism) is the doctrine that all sinful and alienated human souls—because of divine love and mercy—will u ...

, but will not according to most Protestant theologies based on justification through faith:

The Quran explicitly promises salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

for all those righteous Christians who were there before the arrival of Muhammad:

The Quran also makes it clear that the Christians will be nearest in love to those who follow the Quran and praises Christians for being humble and wise:

Early and Medieval Christian writers on Islam and Muhammad

John of Damascus

In 746John of Damascus

John of Damascus ( ar, يوحنا الدمشقي, Yūḥanna ad-Dimashqī; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Δαμασκηνός, Ioánnēs ho Damaskēnós, ; la, Ioannes Damascenus) or John Damascene was a Christian monk, priest, hymnographer, and ...

(sometimes St. John of Damascus) wrote the ''Fount of Knowledge'' part two of which is entitled ''Heresies in Epitome: How They Began and Whence They Drew Their Origin''. In this work St. John makes extensive reference to the Quran and, in St. John's opinion, its failure to live up to even the most basic scrutiny. The work is not exclusively concerned with the ''Ismaelites'' (a name for the Muslims as they claimed to have descended from Ismael) but all heresy. The ''Fount of Knowledge'' references several suras directly often with apparent incredulity.

Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before takin ...

(died c.822) wrote a series of chronicles (284 onwards and 602-813 AD) based initially on those of the better known George Syncellus

George Syncellus ( el, Γεώργιος Σύγκελλος, ''Georgios Synkellos''; died after 810) was a Byzantine chronicler and ecclesiastic. He had lived many years in Palestine (probably in the Old Lavra of Saint Chariton or Souka, near Tekoa ...

. Theophanes reports about Muhammad thus:

Niketas

In the work ''A History of Christian-Muslim Relations'' Hugh Goddard mentions both John of Damascus and Theophanes and goes on to consider the relevance of Niketas Byzantios who formulated replies to letters on behalf of EmperorMichael III

Michael III ( grc-gre, Μιχαήλ; 9 January 840 – 24 September 867), also known as Michael the Drunkard, was Byzantine Emperor from 842 to 867. Michael III was the third and traditionally last member of the Amorian (or Phrygian) dynasty. ...

(842-867). Goddard sums up Niketas' view:

Goddard further argues that Niketas demonstrates in his work a knowledge of the entire Quran, including an extensive knowledge of Suras

The Abhira kingdom in the Mahabharata is either of two kingdoms near the Sarasvati river.

They were dominated by the Abhiras, sometimes referred to as Surabhira also, combining both Sura and Abhira kingdoms. Modern day Abhira territory lies wit ...

2-18. Niketas' account from behind the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

frontier apparently set a strong precedent for later writing both in tone and points of argument.

11th century

Knowledge and depictions of Islam continued to be varied within the Christian West during the 11th century. For instance, the author(s) of the 11th century ''Song of Roland

''The Song of Roland'' (french: La Chanson de Roland) is an 11th-century ''chanson de geste'' based on the Frankish military leader Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, during the reign of the Carolingian king Charlemagne. It is ...

'' evidently had little actual knowledge of Islam. As depicted in this epic poem, Muslims erect statues of Mohammed and worship them, and Mohammed is part of an "Unholy Trinity" together with the Classical Greek Apollyon

The Hebrew term Abaddon ( he, אֲבַדּוֹן ''’Ăḇaddōn'', meaning "destruction", "doom"), and its Greek equivalent Apollyon ( grc-koi, Ἀπολλύων, ''Apollúōn'' meaning "Destroyer") appear in the Bible as both a place of d ...

and Termagant

In the Middle Ages, Termagant or Tervagant was the name given to a god which European Christians believed Muslims worshipped.

The word is also used in modern English to mean a violent, overbearing, turbulent, brawling, quarrelsome woman; a virago ...

, a completely fictional deity. This view, evidently confusing Islam with the pre-Christian Graeco-Roman Religion, appears to reflect misconceptions prevalent in Western Christian society at the time.

On the other hand, ecclesiastic writers such as Amatus of Montecassino

Amatus of Montecassino ( la, Amatus Casinensis), (11th century) was a Benedictine monk of the Abbey of Montecassino who is best known for his historical chronicles of his era. His ''History of the Normans'' (which has survived only in its medieval ...

or Geoffrey Malaterra

Gaufredo (or Geoffrey, or Goffredo) Malaterra ( la, Gaufridus Malaterra) was an eleventh-century Benedictine monk and historian, possibly of Norman origin. He travelled to the southern Italian peninsula, passing some time in Apulia before enteri ...

in Norman Southern Italy, who occasionally lived among Muslims themselves, would depict at times Muslims in a negative way but would depict equally any other (ethnic) group that was opposed to the Norman rule such as Byzantine Greeks

The Byzantine Greeks were the Greek-speaking Eastern Romans of Orthodox Christianity throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were the main inhabitants of the lands of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), of Constantinop ...

or Italian Lombards. Often the depictions would depend on context: when writing about neutral events, Muslims would be called according to geographical terms such as "Saracens" or "Sicilians, when reporting events where Muslims came into conflict with Normans, Muslims would be called "pagans" or "infidels".

Similarities were occasionally acknowledged such as by Pope Gregory VII wrote in a letter to the Hammadid

The Hammadid dynasty () was a branch of the Sanhaja Berber dynasty that ruled an area roughly corresponding to north-eastern modern Algeria between 1008 and 1152. The state reached its peak under Nasir ibn Alnas during which it was briefly the m ...

emir an-Nasir that both Christians and Muslims "worship and confess the same God though in diverse forms and daily praise".

''The Divine Comedy''

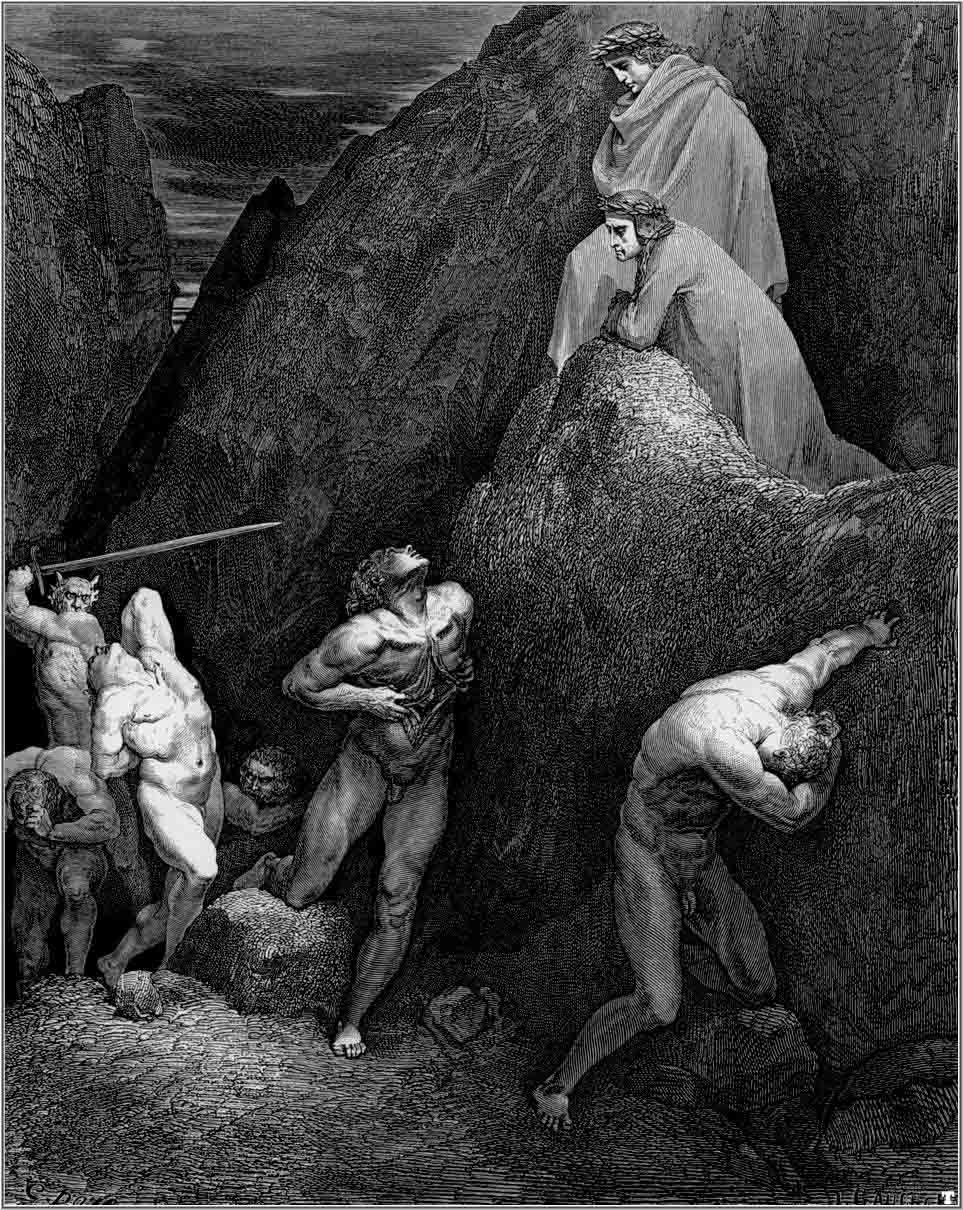

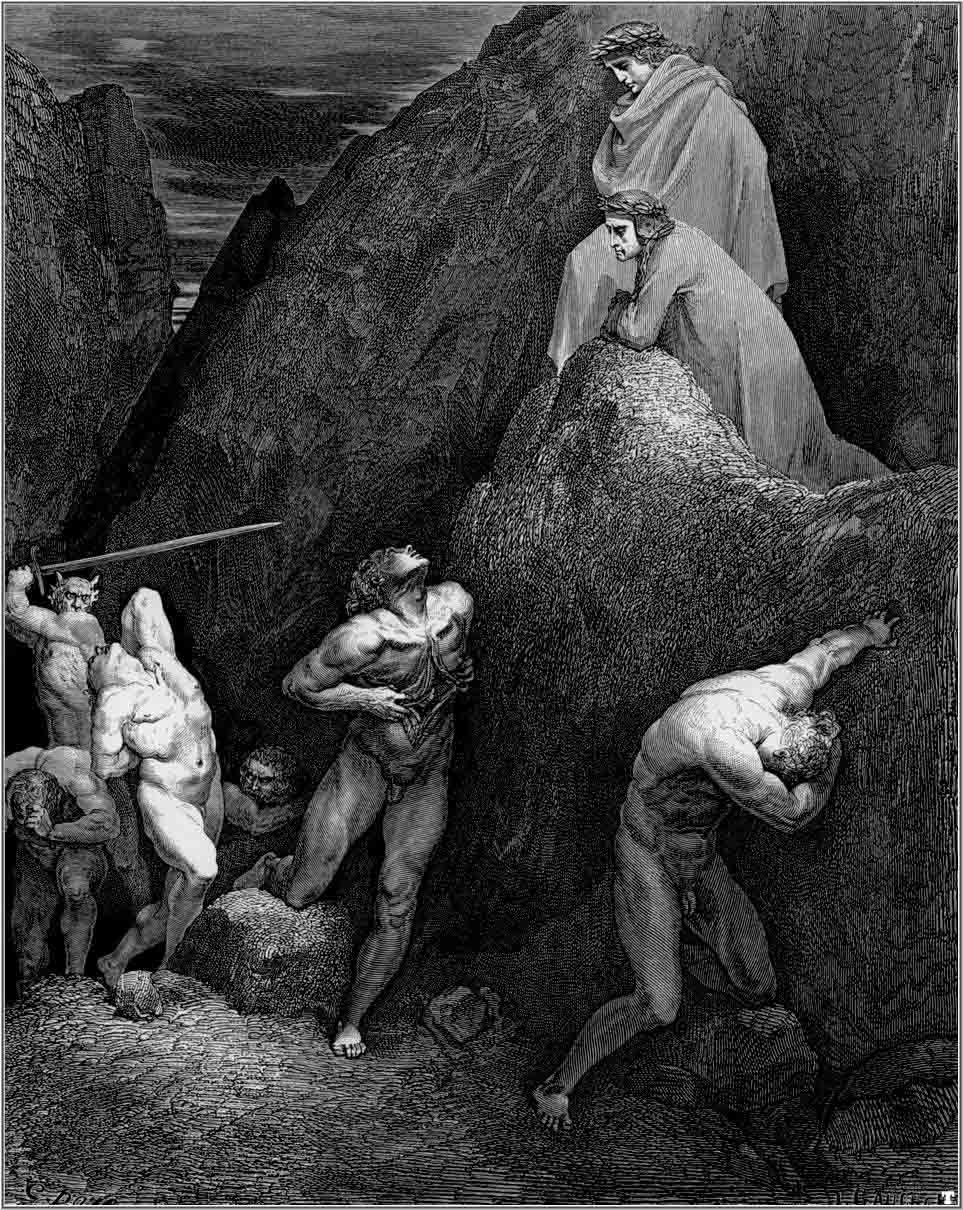

InDante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

's ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature a ...

'', Muhammad is in the ninth ditch of Malebolge

In Dante Alighieri's '' Inferno'', part of the ''Divine Comedy'', Malebolge () is the eighth circle of Hell. Roughly translated from Italian, Malebolge means "evil ditches". Malebolge is a large, funnel-shaped cavern, itself divided into ten co ...

, the eighth realm, designed for those who have caused schism; specifically, he was placed among the Sowers of Religious Discord. Muhammad is portrayed as split in half, with his entrails hanging out, representing his status as a heresiarch

In Christian theology, a heresiarch (also hæresiarch, according to the ''Oxford English Dictionary''; from Greek: , ''hairesiárkhēs'' via the late Latin ''haeresiarcha''Cross and Livingstone, ''Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' 1974 ...

(Canto 28).

This scene is frequently shown in illustrations of the ''Divine Comedy''. Muhammad is represented in a 15th-century fresco ''Last Judgment

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

'' by Giovanni da Modena and drawing on Dante, in the San Petronio Basilica

The Basilica of San Petronio is a minor basilica and church of the Archdiocese of Bologna located in Bologna, Emilia Romagna, northern Italy. It dominates Piazza Maggiore. The basilica is dedicated to the patron saint of the city, Saint Petr ...

in Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, as well as in artwork by Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarre images in ...

, Auguste Rodin, William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, and Gustave Doré

Paul Gustave Louis Christophe Doré ( , , ; 6 January 1832 – 23 January 1883) was a French artist, as a printmaker, illustrator, painter, comics artist, caricaturist, and sculptor. He is best known for his prolific output of wood-engravin ...

.

Catholic Church and Islam

Second Vatican Council and ''Nostra aetate''

The question of Islam was not on the agenda when ''Nostra aetate

(from Latin: "In our time") is the incipit of the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions of the Second Vatican Council. Passed by a vote of 2,221 to 88 of the assembled bishops, this declaration was promulgated o ...

'' was first drafted, or even at the opening of the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

. However, as in the case of the question of Judaism, several events came together again to prompt a consideration of Islam. By the time of the Second Session of the Council in 1963 reservations began to be raised by bishops of the Middle East about the inclusion of this question. The position was taken that either the question will not be raised at all, or if it were raised, some mention of the Muslims should be made. Melkite

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in the Middle East. The term comes from the common Central Semitic root ''m-l-k'', meaning "royal", and ...

patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in ce ...

Maximos IV was among those pushing for this latter position.

Early in 1964 Cardinal Bea notified Cardinal Cicognani, President of the Council's Coordinating Commission, that the Council fathers wanted the Council to say something about the great monotheistic religions, and in particular about Islam. The subject, however, was deemed to be outside the competence of Bea's Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity. Bea expressed willingness to "select some competent people and with them to draw up a draft" to be presented to the Coordinating Commission. At a meeting of the Coordinating Commission on 16–17 April Cicognani acknowledged that it would be necessary to speak of the Muslims.

The period between the first and second sessions saw the change of pontiff

A pontiff (from Latin ''pontifex'') was, in Roman antiquity, a member of the most illustrious of the colleges of priests of the Roman religion, the College of Pontiffs."Pontifex". "Oxford English Dictionary", March 2007 The term "pontiff" was l ...

from Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Roman Catholic Church, Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 28 Oc ...

to Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in Augus ...

, who had been a member of the circle (the ''Badaliya'') of the Islamologist

Islamic studies refers to the academic study of Islam, and generally to academic multidisciplinary "studies" programs—programs similar to others that focus on the history, texts and theologies of other religious traditions, such as Easter ...

Louis Massignon

Louis Massignon (25 July 1883 – 31 October 1962) was a Catholic scholar of Islam and a pioneer of Catholic-Muslim mutual understanding. He was an influential figure in the twentieth century with regard to the Catholic church's relationship ...

. Pope Paul VI chose to follow the path recommended by Maximos IV and he therefore established commissions to introduce what would become paragraphs on the Muslims in two different documents, one of them being ''Nostra aetate'', paragraph three, the other being ''Lumen gentium

''Lumen gentium'', the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, is one of the principal documents of the Second Vatican Council. This dogmatic constitution was promulgated by Pope Paul VI on 21 November 1964, following approval by the assembled bish ...

'', paragraph 16.

The text of the final draft bore traces of Massignon's influence. The reference to Mary, for example, resulted from the intervention of Monsignor Descuffi, the Latin archbishop of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

with whom Massignon collaborated in reviving the cult of Mary at Smyrna. The commendation of Muslim prayer may reflect the influence of the Badaliya.(Robinson, p. 195)

In ''Lumen gentium'', the Second Vatican Council declares that the plan of salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

also includes Muslims, due to their professed monotheism.

Recent Catholic-Islamic controversies

* For the controversy surrounding Muslim prayer in Spain, seeMuslim campaign at Córdoba Cathedral

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraham ...

* For criticism of interfaith dialogue with Muslims, see Pierre Claverie#Relations with Islam

* For the controversy over whether Islam is a religion or a political system, see Raymond Leo Burke#Islam and immigration

* For the controversy over advice not to marry a Muslim and move to an Islamic country, see José Policarpo#Marriages with Muslim men

* For the controversy over whether Catholics may call God "Allah" if they want to, see ''Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur v Menteri Dalam Negeri

''Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur v. Menteri Dalam Negeri'' is a court decision by the High Court of Malaya holding that Christians do not have the constitutional right to use the word "Allah" in church newspapers. An appeals c ...

''

* For the controversy over remarks by Pope Benedict XVI, see Regensburg lecture

The Regensburg lecture or Regensburg address was delivered on 12 September 2006 by Pope Benedict XVI at the University of Regensburg in Germany, which sparked international reactions and controversy. The lecture entitled " Faith, Reason and the ...

and Pope Benedict XVI and Islam

Protestantism and Islam

Protestantism and Islam entered into contact during the 16th century, at a time whenProtestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

movements in northern Europe coincided with the expansion of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alba ...

. As both were in conflict with the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

, numerous exchanges occurred, exploring religious similarities and the possibility of trade and military alliances. Relations became more conflictual in the early modern and modern periods, although recent attempts have been made at rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual enemy, as was the case with Germa ...

.

Mormonism and Islam

Mormonism and Islam

Islam and Mormonism have been compared to one another ever since the earliest origins of the latter in the nineteenth century, often by detractors of one religion or the other—or both. For instance, Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint ...

have been compared to one another ever since the earliest origins of the former in the nineteenth century, often by detractors of one religion or the other—or both. For instance, Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, h ...

, the founding prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

of Mormonism, was referred to as "the modern Mahomet" by the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the ''New York Herald Tribune''.

Hist ...

'', shortly after his murder in June 1844. This epithet repeated a comparison that had been made from Smith's earliest career, one that was not intended at the time to be complimentary. Comparison of the Mormon and Muslim prophets still occurs today, sometimes for derogatory or polemical reasons but also for more scholarly and neutral purposes. While Mormonism and Islam certainly have many similarities, there are also significant, fundamental differences between the two religions. Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into seve ...

– Muslim relations have historically been cordial; recent years have seen increasing dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is ...

between adherents of the two faiths, and cooperation in charitable endeavors, especially in the Middle

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek (d ...

and Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The te ...

.

Christianity and Druze

Christianity and

Christianity and Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings o ...

are Abrahamic religion

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout Abrahamic religious scriptures such as the Bible and the Quran.

Jewish trad ...

s that share a historical traditional connection with some major theological differences. The two faiths share a common place of origin in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, and consider themselves to be monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfor ...

. Even though the faith originally developed out of Ismaili Islam

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

, Druze do not identify as Muslim.

The relationship between the Druze and Christians has been characterized by harmony and coexistence, with amicable relations between the two groups prevailing throughout history, with the exception of some periods, including 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war

The 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus (also called the 1860 Syrian Civil War) was a civil conflict in Mount Lebanon during Ottoman rule in 1860–1861 fought mainly between the local Druze and Christians. Following decisive Druz ...

. Over the centuries a number of the Druze embraced Christianity, such as some of Shihab dynasty members,Mishaqa, p. 23. as well as the Abi-Lamma clan.

Contact between Christians (members of the Maronite

The Maronites ( ar, الموارنة; syr, ܡܖ̈ܘܢܝܐ) are a Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and Levant region of the Middle East, whose members traditionally belong to the Maronite Church, with the largest ...

, Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canoni ...

, Melkite

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in the Middle East. The term comes from the common Central Semitic root ''m-l-k'', meaning "royal", and ...

and other churches) and the Unitarian Druze led to the presence of mixed villages and towns in Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

, Jabal al-Druze

Jabal al-Druze ( ar, جبل الدروز, ''jabal ad-durūz'', ''Mountain of the Druze''), officially Jabal al-Arab ( ar, جبل العرب, links=no, ''jabal al-ʿarab'', ''Mountain of the Arabs''), is an elevated volcanic region in the As-Suwa ...

, Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

, and Mount Carmel

Mount Carmel ( he, הַר הַכַּרְמֶל, Har haKarmel; ar, جبل الكرمل, Jabal al-Karmil), also known in Arabic as Mount Mar Elias ( ar, link=no, جبل مار إلياس, Jabal Mār Ilyās, lit=Mount Saint Elias/ Elijah), is a ...

. The Maronites and the Druze founded modern Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

in the early eighteenth century, through the ruling and social system known as the "Maronite-Druze dualism" in Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate

The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate (1861–1918, ar, مُتَصَرِّفِيَّة جَبَل لُبْنَان, translit=Mutasarrifiyyat Jabal Lubnān; ) was one of the Ottoman Empire's subdivisions following the Tanzimat reform. After 1861, ther ...

.

Christianity does not include belief in reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is ...

or the transmigration of the soul

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

, unlike the Druze. Christians engage in evangelism, often through the establishment of missions

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

* Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

, unlike the Druze who do not accept converts; even marriage outside the Druze faith is rare and strongly discouraged. Similarities between the Druze and Christians include commonalities in their view of views on marriage and divorce, as well as belief in the oneness of God and theophany

Theophany (from Ancient Greek , meaning "appearance of a deity") is a personal encounter with a deity, that is an event where the manifestation of a deity occurs in an observable way. Specifically, it "refers to the temporal and spatial manifes ...

. The Druze faith incorporates some elements of Christianity, and other religious beliefs.

Both faiths give a prominent place to Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

: Jesus is the central figure of Christianity, and in the Druze faith, Jesus is considered an important prophet of God, being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history. Both religions venerated John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

, Saint George

Saint George (Greek: Γεώργιος (Geórgios), Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldie ...

, Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/ YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books ...

, and other common figures.

Artistic influences

Islamic art

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide r ...

and culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these grou ...

have both influenced and been influenced by Christian art

Christian art is sacred art which uses subjects, themes, and imagery from Christianity. Most Christian groups use or have used art to some extent, including early Christian art and architecture and Christian media.

Images of Jesus and narrat ...

and culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these grou ...

. Some arts have received such influence strongly, particularly religious architecture in the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

and medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

eras

See also

* Ashtiname of Muhammad *Chrislam (Yoruba)

Chrislam refers to a Christian expression of Islam, originating as an assemblage of Islamic and Christian religious practices in Nigeria; in particular, the series of religious movements that merged Muslim and Christian religious practice during ...

, a syncretist religion

* Christian influences in Islam

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

* Christian philosophy

Christian philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Christians, or in relation to the religion of Christianity.

Christian philosophy emerged with the aim of reconciling science and faith, starting from natural rational explanations wi ...

* Christianity and other religions

Christianity and other religions documents Christianity's relationship with other world religions, and the differences and similarities.

Christian groups

Christian views on religious pluralism

Western Christian views

Some Christians have argu ...

* Christianity and war

Christians have had diverse attitudes towards violence and non-violence over time. Both currently and historically, there have been four attitudes towards violence and war and four resulting practices of them within Christianity: non-resista ...

* Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

* Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

* Divisions of the world in Islam

In classical Islamic law, the major divisions are ''dar al-Islam'' (lit. territory of Islam/voluntary submission to God), denoting regions where Islamic law prevails, ''dar al-sulh'' (lit. territory of treaty) denoting non-Islamic lands which have ...

* Islam and other religions

Over the centuries of Islamic history, Muslim rulers, Islamic scholars, and ordinary Muslims have held many different attitudes towards other religions. Attitudes have varied according to time, place and circumstance.

Non-Muslims and Islam ...

* Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic ...

* Islam and war

* Muhammad's views on Christians

Muhammad's views on Christians were shaped through his interactions with them. Muhammad had a generally semi-positive view of Christians and viewed them as fellow receivers of Abrahamic revelation (People of the Book). However, he also criticis ...

References

Further reading

* Abdiyah Akbar Abdul-Haqq, ''Sharing Your hristianFaith with a Muslim'', Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1980. * Giulio Basetti-Sani, ''The Koran in the Light of Christ: a Christian Interpretation of the Sacred Book of Islam'', trans. by W. Russell-Carroll and Bede Dauphinee, Chicago, Ill.: Franciscan Herald Press, 1977. * Roger Arnaldez, ''Jésus: Fils de Marie, prophète de l'Islam'', coll. ''Jésus et Jésus-Christ'', no 13, Paris: Desclée, 1980. * Kenneth Cragg, ''The Call of the Minaret'', Third ed., Oxford: Oneworld icPublications, 2000, xv, 358 p. * Maria Jaoudi, ''Christian & Islamic Spirituality: Sharing a Journey'', Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 1992. iii, 103 p. * Jane Dammen McAuliffe, ''Qur'anic Christians: An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. * Frithjof Schuon, ''Christianity/Islam: Essays on Esoteric Ecumenicism'', in series, ''The Library of Traditional Wisdom'', Bloomington, Ind.: World Wisdom Books, cop. 1985. vii, 270 p. ''N.B''.: Trans. from French. ; the ISBN on the verso of the t.p. surely is erroneous. * Mark D. Siljander and John David Mann, ''A Deadly Misunderstanding: a Congressman's Quest to Bridge the Muslim-Christian Divide'', New York: Harper One, 2008. . * Robert Spencer, ''Not Peace But a Sword: The Great Chasm Between Christianity and Islam.'' Catholic Answers. March 25, 2013. . * Thomas, David, ''Muhammad in Medieval Christian-Muslim Relations (Medieval Islam),'' in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol. I, pp. 392–400. 1610691776External links

Hasib Sabbagh: A Legacy of Understanding

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

"I'm Right, You're Wrong, Go to Hell"

– Religions and the meeting of civilization by Bernard Lewis

Islam & Christianity (IRAN & GEORGIA) News Photos

{{Authority control