The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC)

[ or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP),]Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

after 1949. It was the sole party in China during the Republican Era Republican Era can refer to:

* Minguo calendar, the official era of the Republic of China

It may also refer to any era in a country's history when it was governed as a republic or by a Republican Party. In particular, it may refer to:

* Roman Re ...

from 1928 to 1949, when most of the Chinese mainland was under its control. The party retreated from the mainland to Taiwan on 7 December 1949, following its defeat in the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

. Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

declared martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

and retained its authoritarian rule over Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

under the ''Dang Guo

''Dang Guo'' ( zh, t=黨國, p=Dǎngguó, l=party-state) was the one-party system adopted by the Republic of China under the Kuomintang. It was from 1924 onwards, after Sun Yat-sen acknowledged the efficacy of the nascent Soviet Union's polit ...

'' system until democratic reforms were enacted in the 1980s and full democratization in the 1990s. In Taiwanese politics, the KMT is the dominant party in the Pan-Blue Coalition

The pan-Blue coalition, pan-Blue force or pan-Blue groups is a political coalition in the Republic of China (Taiwan) consisting of the Kuomintang (KMT), People First Party (PFP), New Party (CNP), Non-Partisan Solidarity Union (NPSU), and Yo ...

and primarily competes with the rival Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). It is currently the largest opposition party in the Legislative Yuan

The Legislative Yuan is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of China (Taiwan) located in Taipei. The Legislative Yuan is composed of 113 members, who are directly elected for 4-year terms by people of the Taiwan Area through a parallel ...

. The current chairman is Eric Chu.

The party originated as the Revive China Society, founded by Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

on 24 November 1894 in Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the islan ...

, Republic of Hawaii. From there, the party underwent major reorganization changes that occurred before and after the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty, the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of Chi ...

, which resulted in the collapse of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

and the establishment of the Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes Chinese postal romanization, spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China which sat in its capital Pek ...

. In 1919, Sun Yat-sen re-established the party under the name "Kuomintang" in the Shanghai French Concession

The Shanghai French Concession; ; Shanghainese pronunciation: ''Zånhae Fah Tsuka'', group=lower-alpha was a foreign concession in Shanghai, China from 1849 until 1943, which progressively expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

. From 1926 to 1928, the KMT under Chiang Kai-shek successfully led the Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. Th ...

against regional warlords and unified the fragmented nation. From 1937 to 1945, the KMT-ruled Nationalist government led China through the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Thea ...

against Japan. By 1949, the KMT was decisively defeated by the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

(CCP) in the Chinese Civil War (in which the People’s Republic of China was established by the CCP on 1 October 1949) and withdrew the ROC government

The Government of the Republic of China, is the national government of the Republic of China whose ''de facto'' territory currently consists of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other island groups in the "free area". Governed by the Dem ...

to Taiwan, a former Qing territory annexed by the Empire of Japan from 1895 to 1945.

From 1949 to 1987, the KMT ruled Taiwan as an authoritarian one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

after the February 28 incident. During this period, martial law was in effect and civil liberties were curtailed under the guise of anti-communism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and ...

, with the period being known as the White Terror. The party also oversaw Taiwan's economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals a ...

, but also experienced diplomatic setbacks, including the ROC losing its United Nations seat and most of the world including its ally the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

switching diplomatic recognition to the CCP-led People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, sli ...

(PRC) in the 1970s. In the late 1980s, Chiang Ching-kuo

Chiang Ching-kuo (27 April 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a politician of the Republic of China after its Retreat of the Republic of China to Taiwan, retreat to Taiwan. The eldest and only biological son of former president Chiang Kai-she ...

, Chiang Kai-shek's son and the next KMT leader in turn, lifted martial law and allowed the establishment of opposition parties such as the Democratic Progressive Party. His successor Lee Teng-hui

Lee Teng-hui (; 15 January 192330 July 2020) was a Taiwanese statesman and economist who served as President of the Republic of China (Taiwan) under the 1947 Constitution and chairman of the Kuomintang (KMT) from 1988 to 2000. He was the fir ...

continued pursuing democratic reforms and constitutional amendments, and was re-elected in 1996 through a direct presidential election, the first time in the ROC history. The 2000 presidential election put an end to 72 years of the KMT's political dominance in the ROC. The KMT reclaimed power from 2008 to 2016, with the landslide victory of Ma Ying-jeou

Ma Ying-jeou ( zh, 馬英九, born 13 July 1950) is a Hong Kong-born Taiwanese politician who served as president of the Republic of China from 2008 to 2016. Previously, he served as justice minister from 1993 to 1996 and mayor of Taipei from 1 ...

in the 2008 presidential election, whose presidency significantly loosened restrictions placed on cross-strait economic and cultural exchanges. The KMT again lost the presidency and its legislative majority in the 2016 election

The following elections occurred in the year 2016.

Africa

Benin Republic

*2016 Beninese presidential election 6 March 2016

Cape Verde

* 2016 Cape Verdean presidential election 2 October 2016

Chad

* 2016 Chadian presidential election 10 A ...

, returning to the opposition.

The KMT is a member of the International Democrat Union. The party's guiding ideology is the Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (; also translated as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, or Tridemism) is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China made during the Republican Era. ...

, advocated by Sun Yat-sen and historically organized in a Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establish ...

basis of democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is a practice in which political decisions reached by voting processes are binding upon all members of the political party. It is mainly associated with Leninism, wherein the party's political vanguard of professional revol ...

, a principle conceived by the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

that entailed open discussion of policy on the condition of unity among party members in upholding the agreed-upon decisions. The KMT opposes ''de jure'' Taiwan independence

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a Country, country in East Asia, at the junction of the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) to the n ...

, Chinese unification

Chinese unification, also known as the Cross-Strait unification or Chinese reunification, is the potential unification of territories currently controlled, or claimed, by the People's Republic of China ("China" or "Mainland China") and the ...

under the "one country, two systems

"One country, two systems" is a constitutional principle of the People's Republic of China (PRC) describing the governance of the special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau.

The constitutional principle was formulated in the earl ...

" framework, and any non-peaceful means to resolve the cross-strait disputes. Originally placing high priority on reclaiming the Chinese mainland through Project National Glory, the KMT now favors a closer relation with the PRC and seeks to maintain Taiwan's status quo under the Constitution of the Republic of China

The Constitution of the Republic of China is the fifth and current constitution of the Republic of China (ROC), ratified by the Kuomintang during the session on 25 December 1946, in Nanjing, and adopted on 25 December 1947. The constitution, ...

. The party also accepts the 1992 Consensus, which defines both sides of the Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a -wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

The Taiwan Strait is itself ...

as "one China

The term One China may refer to one of the following:

* The One China principle is the position held by the People's Republic of China (PRC) that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, with the PRC serving as the sole legit ...

" but maintains its ambiguity to different interpretations.

History

Founding and Sun Yat-sen era

The KMT traces its ideological and organizational roots to the work of Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, a proponent of Chinese nationalism

Chinese nationalism () is a form of nationalism in the People's Republic of China (Mainland China) and the Republic of China on Taiwan which asserts that the Chinese people are a nation and promotes the cultural and national unity of all C ...

and democracy who founded the Revive China Society at the capital of the Republic of Hawaii, Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the islan ...

, on 24 November 1894. In 1905, Sun joined forces with other anti-monarchist societies in Tokyo, Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent for ...

, to form the Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

, a group committed to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

and the establishment of a republic, on 20 August 1905.

The group supported the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty, the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of Chi ...

of 1911 and the founding of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

on 1 January 1912. Although Sun and the Tongmenghui are often depicted as the principal organizers of the Xinhai Revolution, this view is disputed by scholars who argue that the Revolution broke out in a leaderless and decentralized way and that Sun was only later elected provisional president of the new Chinese republic. However, Sun did not have military power and ceded the provisional presidency of the republic to Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. ...

, who arranged for the abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

of Puyi

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

, the last Emperor, on 12 February.

On 25 August 1912, the Nationalist Party was established at the Huguang Guild Hall in Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

, where the Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

and five smaller pro-revolution parties merged to contest the first national elections. Sun was chosen as the party chairman with Huang Xing as his deputy.

The most influential member of the party was the third ranking Song Jiaoren, who mobilized mass support from gentry and merchants for the Nationalists to advocate a constitutional parliamentary democracy. The party opposed constitutional monarchists

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

and sought to check the power of Yuan. The Nationalists won an overwhelming majority in the first National Assembly election in December 1912.

However, Yuan soon began to ignore the parliament in making presidential decisions. Song Jiaoren was assassinated in Shanghai in 1913. Members of the Nationalists, led by Sun Yat-sen, suspected that Yuan was behind the plot and thus staged the Second Revolution in July 1913, a poorly planned and ill-supported armed rising to overthrow Yuan, and failed. Yuan, claiming subversiveness and betrayal, expelled adherents of the KMT from the parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

. Yuan dissolved the Nationalists, whose members had largely fled into exile in Japan, in November and dismissed the parliament early in 1914.

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. ...

proclaimed himself emperor in December 1915. While exiled in Japan in 1914, Sun established the Chinese Revolutionary Party on 8 July 1914, but many of his old revolutionary comrades, including Huang Xing, Wang Jingwei, Hu Hanmin and Chen Jiongming

Chen Jiongming, (; 18 January 187822 September 1933), courtesy name Jingcun (竞存/競存), nickname Ayan (阿烟/阿煙), was a Hailufeng Hokkien revolutionary figure in the early period of the Republic of China.

Early life

Chen Jiongming ...

, refused to join him or support his efforts in inciting armed uprising against Yuan. To join the Revolutionary Party, members had to take an oath of personal loyalty to Sun, which many old revolutionaries regarded as undemocratic and contrary to the spirit of the revolution. As a result, he became largely sidelined within the Republican movement during this period.

Sun returned to China in 1917 to establish a military junta at Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ent ...

to oppose the Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes Chinese postal romanization, spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China which sat in its capital Pek ...

but was soon forced out of office and exiled to Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

. There, with renewed support, he resurrected the KMT on 10 October 1919, under the name Kuomintang of China () and established its headquarters in Canton in 1920.

In 1923, the KMT and its Canton government accepted aid from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

after being denied recognition by the western powers. Soviet advisers—the most prominent of whom was Mikhail Borodin, an agent of the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

—arrived in China in 1923 to aid in the reorganization and consolidation of the KMT along the lines of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

" Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

, establishing a Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establish ...

party structure that lasted into the 1990s. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was under Comintern instructions to cooperate with the KMT, and its members were encouraged to join while maintaining their separate party identities, forming the First United Front

The First United Front (; alternatively ), also known as the KMT–CCP Alliance, of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was formed in 1924 as an alliance to end warlordism in China. Together they formed the National Revo ...

between the two parties. Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

and early members of the CCP also joined the KMT in 1923.

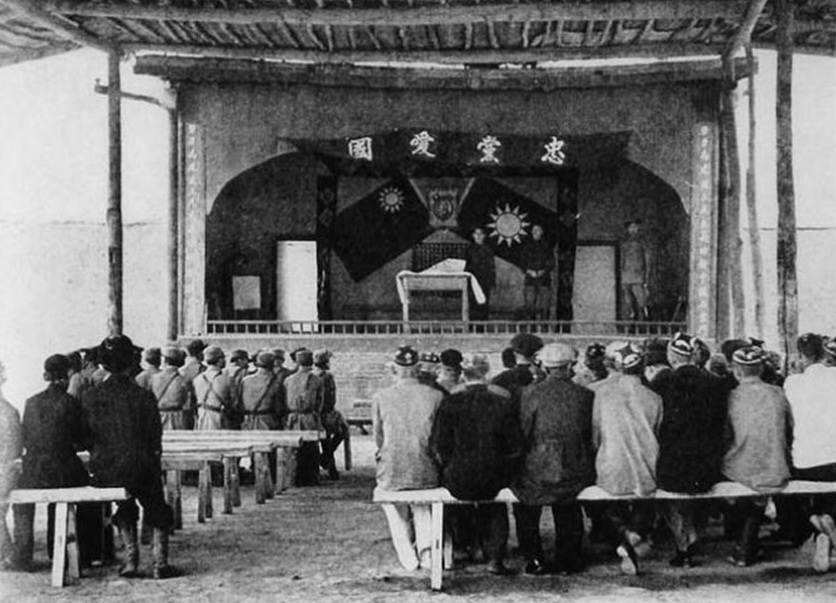

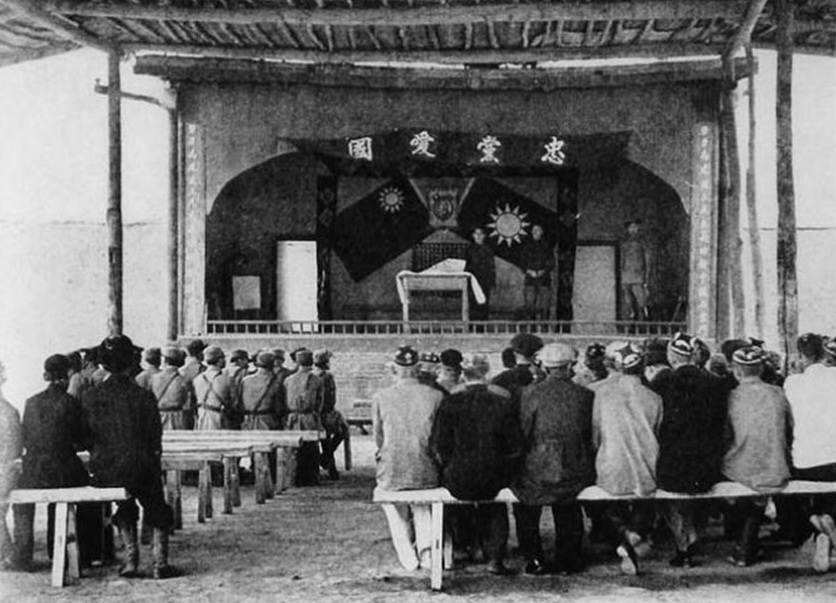

Soviet advisers also helped the KMT to set up a political institute to train propagandists in mass mobilization techniques, and in 1923 Chiang Kai-shek, one of Sun's lieutenants from the

Soviet advisers also helped the KMT to set up a political institute to train propagandists in mass mobilization techniques, and in 1923 Chiang Kai-shek, one of Sun's lieutenants from the Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

days, was sent to Moscow for several months' military and political study. At the first party congress in 1924 in Kwangchow

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong ...

, Kwangtung

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

, (Guangzhou, Guangdong) which included non-KMT delegates such as members of the CCP, they adopted Sun's political theory, which included the Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (; also translated as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, or Tridemism) is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China made during the Republican Era. ...

: nationalism, democracy and people's livelihood.

Under Chiang Kai-shek in Mainland China

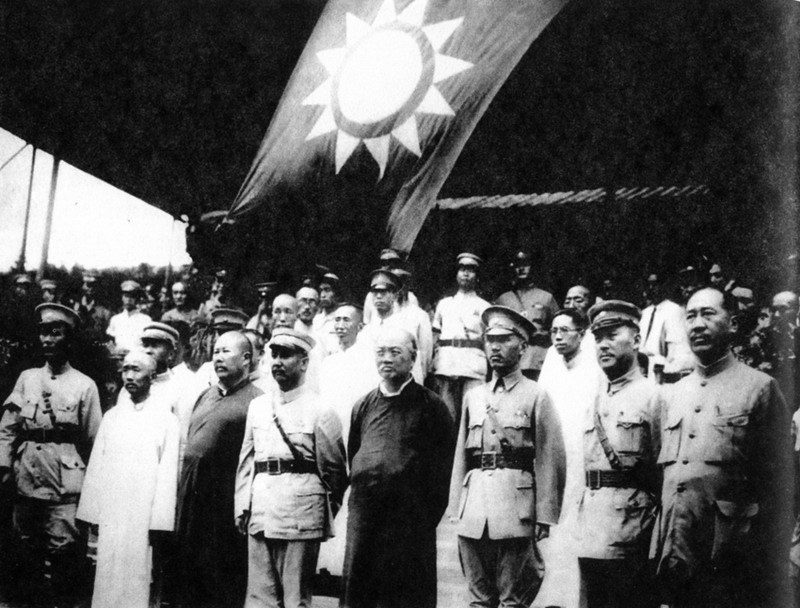

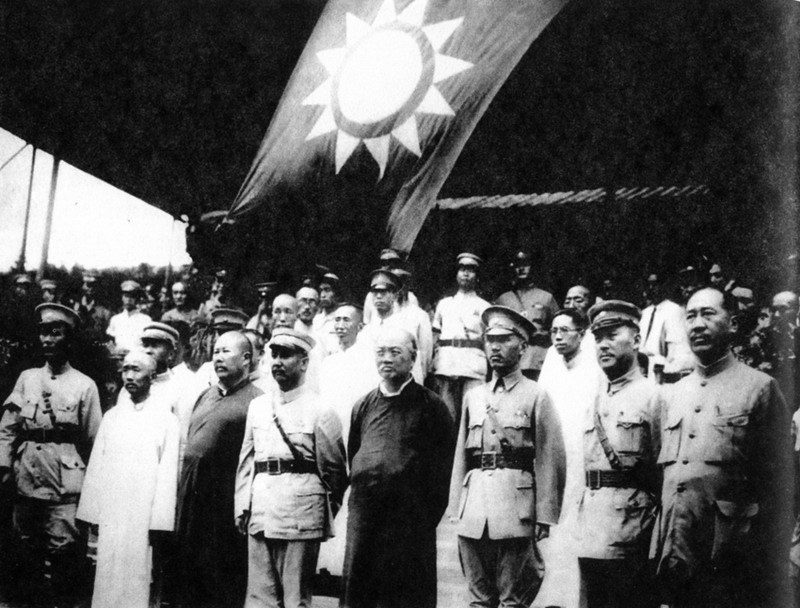

When Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, the political leadership of the KMT fell to Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin, respectively the left-wing and right-wing leaders of the party. However, the real power was in the hands of Chiang Kai-shek, who was in near complete control of the military as the superintendent of the

When Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, the political leadership of the KMT fell to Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin, respectively the left-wing and right-wing leaders of the party. However, the real power was in the hands of Chiang Kai-shek, who was in near complete control of the military as the superintendent of the Whampoa Military Academy

The Republic of China Military Academy () is the service academy for the army of the Republic of China, located in Fengshan District, Kaohsiung. Previously known as the the military academy produced commanders who fought in many of China ...

. With their military superiority, the KMT confirmed their rule on Canton, the provincial capital of Kwangtung

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

. The Guangxi warlords pledged loyalty to the KMT. The KMT now became a rival government in opposition to the warlord

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes Chinese postal romanization, spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China which sat in its capital Pek ...

based in Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

.leadership

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets v ...

of the KMT on 6 July 1926. Unlike Sun Yat-sen, whom he admired greatly and who forged all his political, economic, and revolutionary ideas primarily from what he had learned in Hawaii and indirectly through Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

and Japan under the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were r ...

, Chiang knew relatively little about the West. He also studied in Japan, but he was firmly rooted in his ancient Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

identity and was steeped in Chinese culture

Chinese culture () is one of the world's oldest cultures, originating thousands of years ago. The culture prevails across a large geographical region in East Asia and is extremely diverse and varying, with customs and traditions varying grea ...

. As his life progressed, he became increasingly attached to ancient Chinese culture and traditions. His few trips to the West confirmed his pro-ancient Chinese outlook and he studied the ancient Chinese classics and ancient Chinese history assiduously.First United Front

The First United Front (; alternatively ), also known as the KMT–CCP Alliance, of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was formed in 1924 as an alliance to end warlordism in China. Together they formed the National Revo ...

, Sun Yat-sen sent Chiang to spend three months in Moscow studying the political and military system of the Soviet Union. Although Chiang did not follow the Soviet Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

doctrine, he, like the Communist Party, sought to destroy warlordism and foreign imperialism in China, and upon his return established the Whampoa Military Academy

The Republic of China Military Academy () is the service academy for the army of the Republic of China, located in Fengshan District, Kaohsiung. Previously known as the the military academy produced commanders who fought in many of China ...

near Guangzhou, following the Soviet Model.national government A national government is the government of a nation.

National government or

National Government may also refer to:

* Central government in a unitary state, or a country that does not give significant power to regional divisions

* Federal governme ...

relocated to Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

.Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. Th ...

to defeat the northern warlords and unite China under the party. With its power confirmed in the southeast, the Nationalist Government appointed Chiang Kai-shek commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in Chin ...

(NRA), and the Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. Th ...

to suppress the warlords began. Chiang had to defeat three separate warlords and two independent armies. Chiang, with Soviet supplies, conquered the southern half of China in nine months.

A split erupted between the Chinese Communist Party and the KMT, which threatened the Northern Expedition. Wang Jing Wei, who led the KMT leftist allies, took the city of Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

in January 1927. With the support of the Soviet agent Mikhail Borodin, Wang declared the National Government as having moved to Wuhan. Having taken Nanking in March, Chiang halted his campaign and prepared a violent break with Wang and his communist allies. Chiang's expulsion of the CCP and their Soviet advisers, marked by the Shanghai massacre on 12 April, led to the beginning of the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

. Wang finally surrendered his power to Chiang. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

ordered the Chinese Communist Party to obey the KMT leadership. Once this split had been healed, Chiang resumed his Northern Expedition and managed to take Shanghai.

During the Nanking Incident in March 1927, the NRA stormed the consulates of the United States, the United Kingdom and

During the Nanking Incident in March 1927, the NRA stormed the consulates of the United States, the United Kingdom and Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent for ...

, looted foreign properties and almost assassinated the Japanese consul. An American, two British, one French, an Italian and a Japanese were killed. These looters also stormed and seized millions of dollars worth of British concessions in Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers wh ...

, refusing to hand them back to the UK government. Both Nationalists and Communist soldiers within the army participated in the rioting and looting of foreign residents in Nanking.Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

, and thus a symbolic purge of the final Qing elements. This period of KMT rule in China between 1927 and 1937 was relatively stable and prosperous and is still known as the Nanjing decade.

After the Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. Th ...

in 1928, the Nationalist government under the KMT declared that China had been exploited for decades under the unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

signed between the foreign powers and the Qing Dynasty. The KMT government demanded that the foreign powers renegotiate the treaties on equal terms.

Before the Northern Expedition, the KMT began as a heterogeneous group advocating American-inspired federalism and provincial autonomy. However, the KMT under Chiang's leadership aimed at establishing a centralized one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

with one ideology. This was even more evident following Sun's elevation into a cult figure after his death. The control by one single party began the period of "political tutelage", whereby the party was to lead the government while instructing the people on how to participate in a democratic system. The topic of reorganizing the army, brought up at a military conference in 1929, sparked the Central Plains War. The cliques, some of them former warlords, demanded to retain their army and political power within their own territories. Although Chiang finally won the war, the conflicts among the cliques would have a devastating effect on the survival of the KMT. Muslim Generals in Kansu waged war against the Guominjun in favor of the KMT during the conflict in Gansu in 1927–1930.

Although the

Although the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Thea ...

officially broke out in 1937, Japanese aggression started in 1931 when they staged the Mukden Incident

The Mukden Incident, or Manchurian Incident, known in Chinese as the 9.18 Incident (九・一八), was a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

On September 18, 1931, L ...

and occupied Manchuria. At the same time, the CCP had declared the founding of the Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) in Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north into h ...

while they had been secretly recruiting new members within the KMT government and military. Chiang was alarmed by the expansion of the communist influence. He believed that to fight against foreign aggression, the KMT must solve its internal conflicts first, so he started his second attempt to exterminate CCP members in 1934. With the advice from German military advisors, the KMT had destroyed the CSR and forced the Communists within Jiangxi to withdraw from their bases in southern and central China into the mountains in a massive military retreat known as the Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese Nati ...

. Less than 10% of the communist army survived the long retreat to Shaanxi, but they re-established their military base quickly as the Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Region

Shaan–Gan–Ning or in postal romanization Shen–Kan–Ning () was a historical proto-state that was formed in 1937 by the Chinese Communist Party following the collapse of the Chinese Soviet Republic in agreement with the Kuomintang as a pa ...

with aid from the Soviet Union.

The KMT was also known to have used terror tactics against suspected communists, through the use of a secret police force, who were employed to maintain surveillance on suspected communists and political opponents. In ''The Birth of Communist China'', C.P. Fitzgerald describes China under the rule of the KMT thus: "the Chinese people groaned under a regime Fascist in every quality except efficiency."

Zhang Xueliang, who believed that the Japanese invasion was a greater threat, was persuaded by the CCP to take Chiang hostage during the Xi'an Incident in 1937 and forced Chiang to agree to an alliance with them in the total war against the Japanese. However, in many situations the alliance was in name only; after a brief period of cooperation, the armies began to fight the Japanese separately, rather than as coordinated allies. The New Fourth Army Incident, where the KMT ambushed the New Fourth Army with overwhelming numbers and decimated it, effectively ended collaboration between the CCP and the KMT.

While the KMT army sustained heavy casualties fighting the Japanese, the CCP expanded its territory by guerrilla tactics within Japanese occupied regions, leading some claims that the CCP often refused to support the KMT troops, choosing to withdraw and let the KMT troops take the brunt of Japanese attacks.

Japan surrendered in 1945, and Taiwan was returned to the Republic of China on 25 October of that year. The brief period of celebration was soon shadowed by the possibility of a civil war between the KMT and CCP. The Soviet Union declared war on Japan just before it surrendered and occupied Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym "Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East ( Outer ...

, the north eastern part of China. The Soviet Union denied the KMT army the right to enter the region but allowed the CCP to take control of the Japanese factories and their supplies.

Full-scale civil war between the Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

and the Nationalists erupted in 1946. The Communist Chinese armies, the People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five service branches: the Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, ...

(PLA), previously a minor faction, grew rapidly in influence and power due to several errors on the KMT's part. First, the KMT reduced troop levels precipitously after the Japanese surrender, leaving large numbers of able-bodied, trained fighting men who became unemployed and disgruntled with the KMT as prime recruits for the PLA. Second, the KMT government proved thoroughly unable to manage the economy, allowing hyperinflation to result. Among the most despised and ineffective efforts it undertook to contain inflation was the conversion to the gold standard for the national treasury and the Chinese gold yuan in August 1948, outlawing private ownership of gold, silver and foreign exchange, collecting all such precious metals and foreign exchange from the people and issuing the Gold Standard Scrip in exchange. As most farmland in the north were under CCP's control, the cities governed by the KMT lacked food supply and this added to the hyperinflation. The new scrip became worthless in only ten months and greatly reinforced the nationwide perception of the KMT as a corrupt or at best inept entity. Third, Chiang Kai-shek ordered his forces to defend the urbanized cities. This decision gave CCP a chance to move freely through the countryside. At first, the KMT had the edge with the aid of weapons and ammunition from the United States (US). However, with the country suffering from hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

, widespread corruption and other economic ills, the KMT continued to lose popular support. Some leading officials and military leaders of the KMT hoarded material, armament and military-aid funding provided by the US. This became an issue which proved to be a hindrance of its relationship with US government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

. US President Harry S. Truman wrote that " the Chiangs, the Kungs and the Soongs (were) all thieves", having taken $750 million in US aid.

At the same time, the suspension of American aid and tens of thousands of deserted or decommissioned soldiers being recruited to the PLA cause tipped the balance of power quickly to the CCP side, and the overwhelming popular support for the CCP in most of the country made it all but impossible for the KMT forces to carry out successful assaults against the Communists.

By the end of 1949, the CCP controlled almost all of mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater Chin ...

, as the KMT retreated to Taiwan with a significant amount of China's national treasures and 2 million people, including military forces and refugees. Some party members stayed in the mainland and broke away from the main KMT to found the Revolutionary Committee of the Kuomintang (also known as the Left Kuomintang), which still currently exists as one of the eight minor registered parties of the People's Republic of China.

Rule over Taiwan: 1945-present

In 1895, Formosa (now called Taiwan), including the

In 1895, Formosa (now called Taiwan), including the Penghu

The Penghu (, Hokkien POJ: ''Phîⁿ-ô͘'' or ''Phêⁿ-ô͘'' ) or Pescadores Islands are an archipelago of 90 islands and islets in the Taiwan Strait, located approximately west from the main island of Taiwan, covering an ar ...

islands, became a Japanese colony via the Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the First ...

following the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the p ...

.

After Japan's defeat at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1945, General Order No. 1

General Order No. 1 (Japanese:一般命令第一号) for the surrender of Japan was prepared by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff and approved by President Harry Truman on August 17, 1945.

It was issued by General Douglas MacArthur to the r ...

instructed Japan to surrender its troops in Taiwan to Chiang Kai-shek. On 25 October 1945, KMT general Chen Yi acted on behalf of the Allied Powers to accept Japan's surrender and proclaimed that day as Taiwan Retrocession Day.

Tensions between the local Taiwanese and mainlanders from Mainland China increased in the intervening years, culminating in a flashpoint on 27 February 1947 in Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the ...

when a dispute between a female cigarette vendor and an anti-smuggling officer in front of Tianma Tea House triggered civil disorder and protests that would last for days. The uprising turned bloody and was shortly put down by the ROC Army in the February 28 Incident. As a result of 28 February Incident in 1947, Taiwanese people endured what is called the " White Terror", a KMT-led political repression that resulted in the death or disappearance of over 30,000 Taiwanese intellectuals, activists, and people suspected of opposition to the KMT.

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) on 1 October 1949, the commanders of the People's Liberation Army (PLA) believed that Kinmen

Kinmen, alternatively known as Quemoy, is a group of islands governed as a county by the Republic of China (Taiwan), off the southeastern coast of mainland China. It lies roughly east of the city of Xiamen in Fujian, from which it is se ...

and Matsu had to be taken before a final assault on Taiwan. The KMT fought the Battle of Guningtou on 25–27 October 1949 and stopped the PLA invasion. The KMT headquarter was set up on 10 December 1949 at No. 11 Zhongshan South Road. In 1950, Chiang took office in Taipei under the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion. The provision declared martial law in Taiwan and halted some democratic processes, including presidential and parliamentary elections, until the mainland could be recovered from the CCP. The KMT estimated it would take 3 years to defeat the Communists. The slogan was "prepare in the first year, start fighting in the second, and conquer in the third year." Chiang also initiated the Project National Glory to retake back the mainland in 1965, but was eventually dropped in July 1972 after many unsuccessful attempts.

However, various factors, including international pressure, are believed to have prevented the KMT from militarily engaging the CCP full-scale. The KMT backed Muslim insurgents formerly belonging to the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in Chin ...

during the KMT Islamic insurgency in 1950–1958 in Mainland China. A cold war with a couple of minor military conflicts was resulted in the early years. The various government bodies previously in Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

, that were re-established in Taipei as the KMT-controlled government, actively claimed sovereignty over all China. The Republic of China in Taiwan retained China and the United Nations, China's seat in the United Nations until 1971 as well as recognition by the United States until 1979.

Until the 1970s, the KMT successfully pushed ahead with land reforms, developed the economy, implemented a democratic system in a lower level of the government, improved Cross-Strait relations, relations between Taiwan and the mainland and created the Taiwan economic miracle. However, the KMT controlled the government under a one-party authoritarian state until reforms in the late 1970s through the 1990s. The ROC in Taiwan was once referred to synonymously with the KMT and known simply as Nationalist China after its ruling party. In the 1970s, the KMT began to allow for "supplemental elections" in Taiwan to fill the seats of the aging representatives in the National Assembly (Republic of China), National Assembly.

Although opposition parties were not permitted, the pro-democracy movement ''Tangwai'' ("outside the KMT") created the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) on 28 September 1986. Outside observers of Taiwanese politics expected the KMT to clamp down and crush the illegal opposition party, though this did not occur, and instead the party's formation marked the beginning of Taiwan's democratization.

In 1991, martial law ceased when President Lee Teng-hui

Lee Teng-hui (; 15 January 192330 July 2020) was a Taiwanese statesman and economist who served as President of the Republic of China (Taiwan) under the 1947 Constitution and chairman of the Kuomintang (KMT) from 1988 to 2000. He was the fir ...

terminated the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion. All parties started to be allowed to compete at all levels of elections, including the presidential election. Lee Teng-hui

Lee Teng-hui (; 15 January 192330 July 2020) was a Taiwanese statesman and economist who served as President of the Republic of China (Taiwan) under the 1947 Constitution and chairman of the Kuomintang (KMT) from 1988 to 2000. He was the fir ...

, the ROC's first democratically elected president and the leader of the KMT during the 1990s, announced his advocacy of "special state-to-state relations" with the PRC. The PRC associated this idea with Taiwan independence

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a Country, country in East Asia, at the junction of the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) to the n ...

.

The KMT faced a split in 1993 that led to the formation of the New Party (Taiwan), New Party in August 1993, alleged to be a result of Lee's "corruptive ruling style". The New Party has, since the purging of Lee, largely reintegrated into the KMT. A much more serious split in the party occurred as a result of the 2000 Taiwan presidential election, 2000 Presidential election. Upset at the choice of Lien Chan as the party's presidential nominee, former party Secretary-General James Soong launched an independent bid, which resulted in the expulsion of Soong and his supporters and the formation of the People First Party (Taiwan), People First Party (PFP) on 31 March 2000. The KMT candidate placed third behind Soong in the elections. After the election, Lee's strong relationship with the opponent became apparent. To prevent defections to the PFP, Lien moved the party away from Lee's pro-independence policies and became more favorable toward Chinese unification

Chinese unification, also known as the Cross-Strait unification or Chinese reunification, is the potential unification of territories currently controlled, or claimed, by the People's Republic of China ("China" or "Mainland China") and the ...

. This shift led to Lee's expulsion from the party and the formation of the Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU) by Lee supporters on 24 July 2001.

Prior to this, the party's voters had defected to both the PFP and TSU, and the KMT did poorly in the 2001 Taiwan legislative election, December 2001 legislative elections and lost its position as the largest party in the

Prior to this, the party's voters had defected to both the PFP and TSU, and the KMT did poorly in the 2001 Taiwan legislative election, December 2001 legislative elections and lost its position as the largest party in the Legislative Yuan

The Legislative Yuan is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of China (Taiwan) located in Taipei. The Legislative Yuan is composed of 113 members, who are directly elected for 4-year terms by people of the Taiwan Area through a parallel ...

. However, the party did well in the 2002 local government mayoral and council election with Ma Ying-jeou

Ma Ying-jeou ( zh, 馬英九, born 13 July 1950) is a Hong Kong-born Taiwanese politician who served as president of the Republic of China from 2008 to 2016. Previously, he served as justice minister from 1993 to 1996 and mayor of Taipei from 1 ...

, its candidate for Taipei mayor, winning reelection by a landslide and its candidate for Kaohsiung mayor narrowly losing but doing surprisingly well. Since 2002, the KMT and PFP have coordinated electoral strategies. In 2004, the KMT and PFP ran a joint presidential ticket, with Lien running for president and Soong running for vice-president.

The loss of the presidential election of 2004 to DPP President Chen Shui-bian by merely over 30,000 votes was a bitter disappointment to party members, leading to large scale rallies for several weeks protesting alleged electoral fraud and the "odd circumstances" of the 3-19 shooting incident, shooting of President Chen. However, the fortunes of the party were greatly improved when the KMT did well in the 2004 Taiwan legislative election, legislative elections held in December 2004 by maintaining its support in southern Taiwan achieving a majority for the Pan-Blue Coalition

The pan-Blue coalition, pan-Blue force or pan-Blue groups is a political coalition in the Republic of China (Taiwan) consisting of the Kuomintang (KMT), People First Party (PFP), New Party (CNP), Non-Partisan Solidarity Union (NPSU), and Yo ...

.

Soon after the election, there appeared to be a falling out with the KMT's junior partner, the People First Party and talk of a merger seemed to have ended. This split appeared to widen in early 2005, as the leader of the PFP, James Soong appeared to be reconciling with President Chen Shui-Bian and the Democratic Progressive Party. Many PFP members including legislators and municipal leaders have since defected to the KMT, and the PFP is seen as a fading party.

In 2005, Ma Ying-jeou became KMT chairman defeating speaker Wang Jin-pyng in the 2005 Kuomintang chairmanship election, first public election for KMT chairmanship. The KMT won a decisive victory in the 2005 Taiwanese local elections, 3-in-1 local elections of December 2005, replacing the DPP as the largest party at the local level. This was seen as a major victory for the party ahead of legislative elections in 2007. There were elections for the two municipalities of the ROC, Taipei and Kaohsiung in December 2006. The KMT won a clear victory in Taipei, but lost to the DPP in the southern city of Kaohsiung by the slim margin of 1,100 votes.

On 13 February 2007, Ma was indicted by the Taiwan High Prosecutors Office on charges of allegedly embezzling approximately NT$11 million (US$339,000), regarding the issue of "special expenses" while he was mayor of Taipei. Shortly after the indictment, he submitted his resignation as KMT chairman at the same press conference at which he formally announced his candidacy for ROC President. Ma argued that it was customary for officials to use the special expense fund for personal expenses undertaken in the course of their official duties. In December 2007, Ma was acquitted of all charges and immediately filed suit against the prosecutors. In 2008, the KMT won a landslide victory in the 2008 Taiwan presidential election, Republic of China Presidential Election on 22 March 2008. The KMT fielded former Taipei mayor and former KMT chairman Ma Ying-jeou

Ma Ying-jeou ( zh, 馬英九, born 13 July 1950) is a Hong Kong-born Taiwanese politician who served as president of the Republic of China from 2008 to 2016. Previously, he served as justice minister from 1993 to 1996 and mayor of Taipei from 1 ...

to run against the DPP's Frank Hsieh. Ma won by a margin of 17% against Hsieh. Ma took office on 20 May 2008, with Vice-Presidential candidate Vincent Siew, and ended 8 years of the DPP presidency. The KMT also won a landslide victory in the 2008 Taiwan legislative election, 2008 legislative elections, winning 81 of 113 seats, or 71.7% of seats in the Legislative Yuan

The Legislative Yuan is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of China (Taiwan) located in Taipei. The Legislative Yuan is composed of 113 members, who are directly elected for 4-year terms by people of the Taiwan Area through a parallel ...

. These two elections gave the KMT firm control of both the executive and legislative yuans.

On 25 June 2009, President Ma launched his bid to regain the KMT leadership and registered as the sole candidate for the 2009 Kuomintang chairmanship election, chairmanship election. On 26 July, Ma won 93.87% of the vote, becoming the new chairman of the KMT, taking office on 17 October 2009. This officially allowed Ma to be able to meet with Xi Jinping, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, and other PRC delegates, as he was able to represent the KMT as leader of a Chinese political party rather than as head-of-state of a political entity unrecognized by the PRC.

On 29 November 2014, the KMT suffered a heavy loss in the 2014 Taiwanese local elections, local election to the DPP, winning only 6 municipalities and counties, down from 14 in the previous election in 2009 Taiwanese local elections, 2009 and 2010 Taiwanese municipal elections, 2010. Ma Ying-jeou subsequently resigned from the party chairmanship on 3 December and replaced by acting Chairman Wu Den-yih. 2015 Kuomintang chairmanship election, Chairmanship election was held on 17 January 2015 and Eric Chu was elected to become the new chairman. He was inaugurated on 19 February.

Current issues and challenges

Party assets

Upon arriving in Taiwan the KMT occupied assets previously owned by the Japanese and forced local businesses to make contributions directly to the KMT. Some of this real estate and other assets was distributed to party loyalists, but most of it remained with the party, as did the profits generated by the properties.

As the ruling party on Taiwan, the KMT amassed a vast business empire of banks, investment companies, petrochemical firms, and television and radio stations, thought to have made it the world's richest political party, with assets once estimated to be around US$2–10 billion.Legislative Yuan

The Legislative Yuan is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of China (Taiwan) located in Taipei. The Legislative Yuan is composed of 113 members, who are directly elected for 4-year terms by people of the Taiwan Area through a parallel ...

to recover illegally acquired party assets and return them to the government. However, due to the DPP's lack of control of the legislative chamber at the time, it never materialized.

The KMT also acknowledged that part of its assets were acquired through extra-legal means and thus promised to "retro-endow" them to the government. However, the quantity of the assets which should be classified as illegal are still under heated debate. DPP, in its capacity as ruling party from 2000 to 2008, claimed that there is much more that the KMT has yet to acknowledge. Also, the KMT actively sold assets under its title to quench its recent financial difficulties, which the DPP argues is illegal. Former KMT chairman Ma Ying-Jeou's position is that the KMT will sell some of its properties at below market rates rather than return them to the government and that the details of these transactions will not be publicly disclosed.

In 2006, the KMT sold its headquarters at 11 Zhongshan South Road in

In 2006, the KMT sold its headquarters at 11 Zhongshan South Road in Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the ...

to Evergreen Group for New Taiwan dollar, NT$2.3 billion (US$96 million). The KMT moved into a smaller building on Bade Road in the eastern part of the city.

In July 2014, the KMT reported total assets of NT$26.8 billion (US$892.4 million) and interest earnings of NT$981.52 million for the year of 2013, making it one of the richest political parties in the world.

In August 2016, the Ill-gotten Party Assets Settlement Committee is set up by the ruling DPP government to investigate KMT party assets acquired during the martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

period and recover those that were determined to be illegally acquired.

Cross-strait relations

In December 2003, then-KMT chairman (present chairman emeritus) and presidential candidate Lien Chan initiated what appeared to some to be a major shift in the party's position on the linked questions of Chinese unification and Taiwan independence. Speaking to foreign journalists, Lien said that while the KMT was opposed to "immediate independence", it did not wish to be classed as "pro-reunificationist" either.

At the same time, Wang Jin-pyng, speaker of the Legislative Yuan

The Legislative Yuan is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of China (Taiwan) located in Taipei. The Legislative Yuan is composed of 113 members, who are directly elected for 4-year terms by people of the Taiwan Area through a parallel ...

and the Pan-Blue Coalition's campaign manager in the 2004 presidential election, said that the party no longer opposed Taiwan's "eventual independence". This statement was later clarified as meaning that the KMT opposes any immediate decision on unification and independence and would like to have this issue resolved by future generations. The KMT's position on the cross-strait relations was redefined as hoping to remain in the current neither-independent-nor-united situation.

However, there had been a warming of relations between the Pan-Blue Coalition

The pan-Blue coalition, pan-Blue force or pan-Blue groups is a political coalition in the Republic of China (Taiwan) consisting of the Kuomintang (KMT), People First Party (PFP), New Party (CNP), Non-Partisan Solidarity Union (NPSU), and Yo ...

and the PRC, with prominent members of both the KMT and PFP in active discussions with officials on the mainland. In February 2004, it appeared that the KMT had opened a campaign office for the Lien-Soong ticket in Shanghai targeting Taiwanese businessmen. However, after an adverse reaction in Taiwan, the KMT quickly declared that the office was opened without official knowledge or authorization. In addition, the PRC issued a statement forbidding open campaigning in the mainland and formally stated that it had no preference as to which candidate won and cared only about the positions of the winning candidate.

In 2005, then-party chairman Lien Chan announced that he was to leave his office. The two leading contenders for the position included Ma Ying-jeou

Ma Ying-jeou ( zh, 馬英九, born 13 July 1950) is a Hong Kong-born Taiwanese politician who served as president of the Republic of China from 2008 to 2016. Previously, he served as justice minister from 1993 to 1996 and mayor of Taipei from 1 ...

and Wang Jin-pyng. On 5 April 2005, Mayor of Taipei, Taipei Mayor Ma Ying-jeou said he wished to lead the opposition KMT with Wang Jin-pyng. On 16 July 2005, Ma was elected KMT chairman in the 2005 KMT chairmanship election, first contested leadership in the KMT's 93-year history. Some 54% of the party's 1.04 million members cast their ballots. Ma garnered 72.4% of the vote share, or 375,056 votes, against Wang's 27.6%, or 143,268 votes. After failing to convince Wang to stay on as a vice chairman, Ma named holdovers Wu Po-hsiung, Chiang Pin-kung and Lin Cheng-chi (), as well as long-time party administrator and strategist John Kuan as vice-chairmen. All appointments were approved by a hand count of party delegates.

On 28 March 2005, thirty members of the KMT, led by vice-chairman Chiang Pin-kung, 2005 Kuomintang visits to Mainland, arrived in mainland China. This marked the first official visit by the KMT to the mainland since it was defeated by communist forces in 1949 (although KMT members including Chiang had made individual visits in the past). The delegates began their itinerary by paying homage to the revolutionary martyrs of the Tenth Uprising at Huanghuagang. They subsequently flew to the former ROC capital of

On 28 March 2005, thirty members of the KMT, led by vice-chairman Chiang Pin-kung, 2005 Kuomintang visits to Mainland, arrived in mainland China. This marked the first official visit by the KMT to the mainland since it was defeated by communist forces in 1949 (although KMT members including Chiang had made individual visits in the past). The delegates began their itinerary by paying homage to the revolutionary martyrs of the Tenth Uprising at Huanghuagang. They subsequently flew to the former ROC capital of Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

to commemorate Sun Yat-sen. During the trip, the KMT signed a 10-points agreement with the CCP. The proponents regarded this visit as the prelude of the third KMT-CCP cooperation, after the First United Front, First and Second United Front. Weeks afterwards, in May 2005, Chairman Lien Chan visited the mainland and met with Hu Jintao, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. This marked the first meeting between leaders of the KMT and CCP after the end of Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

in 1949. No agreements were signed because incumbent Chen Shui-bian's government threatened to prosecute the KMT delegation for treason and violation of Law of the Republic of China, ROC laws prohibiting citizens from collaborating with CCP.

Supporter base

Support for the KMT in Taiwan encompasses a wide range of social groups but is largely determined by age. KMT support tends to be higher in northern Taiwan and in urban areas, where it draws its backing from big businesses due to its policy of maintaining commercial links with mainland China. As of 2020 only 3% of KMT members are under 40 years of age.

The KMT also has some support in the labor sector because of the many labor benefits and insurance implemented while the KMT was in power. The KMT traditionally has strong cooperation with military officers, teachers, and government workers. Among the ethnic groups in Taiwan, the KMT has stronger support among mainlanders and their descendants, for ideological reasons, and among Taiwanese aboriginals. The support for the KMT generally tend to be stronger in majority-Hakka and Mandarin Chinese, Mandarin-speaking counties of Taiwan, in contrast to the Hokkien-majority southwestern counties that tend to support the Democratic Progressive Party.

The deep-rooted hostility between Aboriginals and (Taiwanese) Hoklo, and the Aboriginal communities effective KMT networks, contribute to Aboriginal skepticism towards the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Aboriginals' tendency to vote for the KMT.Ma Ying-jeou

Ma Ying-jeou ( zh, 馬英九, born 13 July 1950) is a Hong Kong-born Taiwanese politician who served as president of the Republic of China from 2008 to 2016. Previously, he served as justice minister from 1993 to 1996 and mayor of Taipei from 1 ...

. In 2005 the Kuomintang displayed a massive photo of the anti-Japanese Aboriginal leader Mona Rudao at its headquarters in honor of the 60th anniversary of Taiwan's retrocession from Japan to the Republic of China.

On social issues, the KMT does not take an official position on Same-sex marriage in Taiwan, same-sex marriage, though most members of legislative committees, mayors of cities, and the most recent presidential candidate (Han Kuo-yu) oppose it. The party does, however, have a small faction that supports same-sex marriage, consisting mainly of young people and people in the Taipei metropolitan area. The opposition to same-sex marriage comes mostly from Christianity in Taiwan, Christian groups, who wield significant political influence within the KMT.

Organization

Leadership

The Kuomintang's constitution designated Sun Yat-sen as party president. After his death, the Kuomintang opted to keep that language in its constitution to honor his memory forever. The party has since been headed by a director-general (1927–1975) and a chairman (since 1975), positions which officially discharge the functions of the president.

Current Central Committee Leadership

Legislative Yuan leader (Caucus leader)

* (1 February 1999 – 1 February 2004)

* Tseng Yung-chuan (1 February 2004 – 1 December 2008)

* Lin Yi-shih (1 December 2008 – 1 February 2012)

* Lin Hung-chih (1 February 2012 – 31 July 2014)

* (31 July 2014 – 7 February 2015)

* Lai Shyh-bao (7 February 2015 – 7 July 2016)

* Liao Kuo-tung (7 July 2016 – 29 June 2017)

* Lin Te-fu (29 June 2017 – 14 June 2018)

* Johnny Chiang (14 June 2018 – 2019)

* Tseng Ming-chung (2019 – 2020)

* (2020 – 2021)

* Alex Fai (2021 – 2022)

* Tseng Ming-chung (2022 – present)

Party organization and structure

The KMT is organized that is being led by a Central Committee with a commitment to a Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establish ...

principle of democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is a practice in which political decisions reached by voting processes are binding upon all members of the political party. It is mainly associated with Leninism, wherein the party's political vanguard of professional revol ...

:

* National Congress

** Party chairman

*** Vice-chairmen

**

*** Central Steering Committee for Women

** Central Standing Committee

** Secretary-General

*** Deputy Secretaries-General

** Executive Director

Standing committees and departments

* Policy Committee

** Policy Coordination Department

** Policy Research Department

** Mainland Affairs Department

* Institute of Revolutionary Practice, formerly National Development Institute

** Kuomintang Youth League

** Research Division

** Education and Counselling Division

*Party Disciplinary Committee

** Evaluation and Control Office

** Audit Office

* Culture and Communications Committee

** Cultural Department

** Communications Department

** KMT Party History Institute

* Administration Committee

** Personnel Office

** General Office

** Finance Office

** Accounting Office

** Information Center

* Organizational Development Committee

** Organization and Operations Department

** Elections Mobilization Department

** Community Volunteers Department

** Overseas Department

** Youth Department

** Women's Department

Party charter

The Kuomintang Party Charter was adopted on January 28, 1924. The current charter has 51 articles and includes contents of General Principles, Party Membership, Organization, The National President, The Director-General, The National Congress, The Central Committee, District and Sub-District Party Headquarters, Cadres and Tenure, Discipline, Awards and Punishment, Funding, and Supplementary Provisions. The most recent version was made at the Twentieth National Congress on July 28, 2019.

Ideology in mainland China

Chinese nationalism

The KMT was a nationalist revolutionary party that had been supported by the Soviet Union. It was organized on the Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establish ...

principle of democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is a practice in which political decisions reached by voting processes are binding upon all members of the political party. It is mainly associated with Leninism, wherein the party's political vanguard of professional revol ...

.

Fascism

The Blue Shirts Society, a Fascism, fascist paramilitary organization within the KMT that modeled itself after Benito Mussolini, Mussolini's blackshirts, was Xenophobia, anti-foreign and Anti-communism, anti-communist, and it stated that its agenda was to expel foreign (Japanese and Western) imperialists from China, crush Communism, and eliminate feudalism.[Schoppa, R. Keith]

The Revolution and Its Past