Chickasaw High School on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Chickasaw ( ) are an

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the  The first European contact with the Chickasaw ancestors was in 1540 when

The first European contact with the Chickasaw ancestors was in 1540 when

indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the nor ...

. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the southern United States and the southern por ...

of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, and Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

as well in southwestern Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

. Their language is classified as a member of the Muskogean

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

language family. In the present day, they are organized as the federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation (Chickasaw language, Chickasaw: Chikashsha I̠yaakni) is a federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe, with its headquarters located in Ada, Oklahoma in th ...

.

Chickasaw people have a migration story in which they moved from a land west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, where they settled mostly in present-day northeast Mississippi, northwest Alabama, and into Lawrence County, Tennessee

Lawrence County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 44,159. Its county seat and largest city is Lawrenceburg. Lawrence County comprises the Lawrenceburg, TN Micropolitan Statistical Ar ...

. They had interaction with French, English, and Spanish colonists during the colonial period. The United States considered the Chickasaw one of the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

of the Southeast, as they adopted numerous practices of European Americans. Resisting European-American settlers encroaching on their territory, they were forced by the U.S. government to sell their traditional lands in the 1832 Treaty of Pontotoc Creek

The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek was a treaty signed on October 20, 1832 by representatives of the United States and the Chiefs of the Chickasaw Nation assembled at the National Council House on Pontotoc Creek in Pontotoc, Mississippi. The treaty cede ...

and move to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

(Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

) during the era of Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

in the 1830s.

Most of their descendants remain as residents of what is now Oklahoma. The Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma is the 13th-largest federally recognized tribe

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

in the United States. Its members are related to the Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

and share a common history with them. The Chickasaw were divided into two groups ( moieties): the ''Imosak Cha'a'matrilineal descent

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance of ...

, in which inheritance and descent are traced through the maternal line. Children are considered born into the mother's family and clan, and gain their social status from her. Women controlled most property and hereditary leadership in the tribe passed through the maternal line.

Etymology

The name Chickasaw, as noted by anthropologistJohn Swanton

John Reed Swanton (February 19, 1873 – May 2, 1958) was an American anthropologist, folklorist, and linguist who worked with Native American peoples throughout the United States. Swanton achieved recognition in the fields of ethnology and ethn ...

, belonged to a Chickasaw leader.

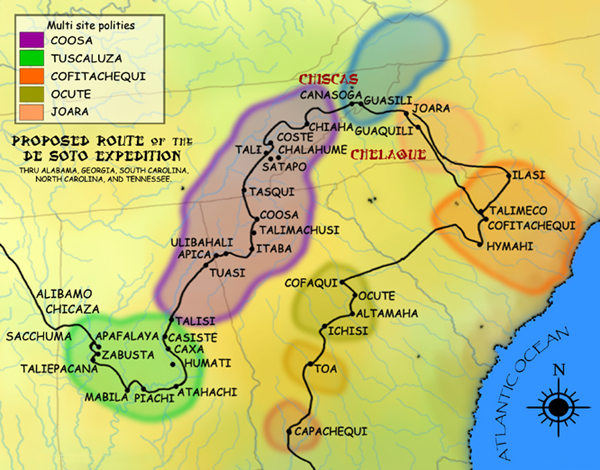

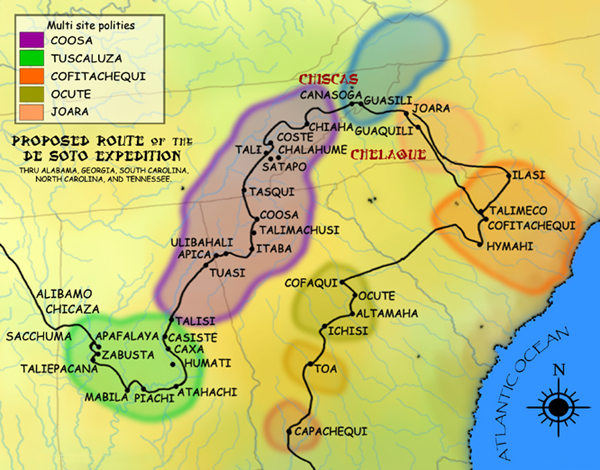

"Chickasaw" is the English spelling of ''Chikashsha'' (), meaning "comes from Chicsa". In an 1890 extra census bulletin on the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee, and Seminole, a history of the Choctaw and Chickasaw was included that was written by R.W. McAdam. McAdam claimed that the word "Chikasha" meant "rebel" in the Choctaw language. Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

had recorded the people as ''Chicaza'' when his expedition came into contact with them in 1540; the Spanish were the first known Europeans to explore the North American Southeast.

History

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

Patricia Galloway, theorize that the Chickasaw and Choctaw split into distinct peoples in the 17th century from the remains of Plaquemine culture

The Plaquemine culture was an archaeological culture (circa 1200 to 1700 CE) centered on the Lower Mississippi River valley. It had a deep history in the area stretching back through the earlier Coles Creek (700-1200 CE) and Troyville cultures ...

and other groups whose ancestors had lived in the lower Mississippi Valley for thousands of years. When Europeans first encountered them, the Chickasaw were living in villages in what is now northeastern Mississippi.

The Chickasaw are believed to have migrated into Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

from the west, as their oral history attests. They and the Choctaw were once one people and migrated from west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

into present-day Mississippi in prehistoric times; the Chickasaw and Choctaw split along the way. The Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere

The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (formerly the Southern Cult), aka S.E.C.C., is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture. It coincided with their ado ...

spanned the Eastern Woodlands

The Eastern Woodlands is a cultural area of the indigenous people of North America. The Eastern Woodlands extended roughly from the Atlantic Ocean to the eastern Great Plains, and from the Great Lakes region to the Gulf of Mexico, which is now pa ...

. The Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

s emerged from previous moundbuilding societies

A number of pre-Columbian cultures are collectively termed "Mound Builders". The term does not refer to a specific people or archaeological culture, but refers to the characteristic mound earthworks erected for an extended period of more than 5 ...

by 880 CE. They built complex, dense villages supporting a stratified society, with centers throughout the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys and their tributaries.

In the 15th century, proto-Chickasaw people left the Tombigbee Valley

The Tombigbee River is a tributary of the Mobile River, approximately 200 mi (325 km) long, in the U.S. states of Mississippi and Alabama. Together with the Alabama River, Alabama, it merges to form the short Mobile River before the latt ...

after the collapse of the Moundville chiefdom. They settled into the upper Yazoo and Pearl River

The Pearl River, also known by its Chinese name Zhujiang or Zhu Jiang in Mandarin pinyin or Chu Kiang and formerly often known as the , is an extensive river system in southern China. The name "Pearl River" is also often used as a catch-all ...

valleys in present-day Mississippi. Historian Arrell Gibson

Arrell Morgan Gibson (1921–1987) was a historian and author specializing in the history of the state of Oklahoma.

Gibson was born in Pleasanton, Kansas on December 1, 1921. He earned degrees from Missouri Southern State College and the Univers ...

and anthropologist John R. Swanton

John Reed Swanton (February 19, 1873 – May 2, 1958) was an American anthropologist, folklorist, and linguist who worked with Native American peoples throughout the United States. Swanton achieved recognition in the fields of ethnology and et ...

believed the Chickasaw Old Fields were in Madison County, Alabama

Madison County is located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 388,153, making it the third-most populous county in Alabama. Its county seat is Huntsville. Since the mid-20th centu ...

.

Another version of the Chickasaw creation story is that they arose at ''Nanih Waiya

Nanih Waiya (alternately spelled Nunih Waya) is an ancient platform mound in southern Winston County, Mississippi, constructed by indigenous people during the Middle Woodland period, about 300 to 600 CE. Since the 17th century, the Choctaw have v ...

,'' a great earthwork mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically higher el ...

built about 300 CE by Woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

peoples. It is also sacred to the Choctaw, who have a similar story about it. The mound was built about 1400 years before the coalescence of each of these peoples as ethnic

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

groups.

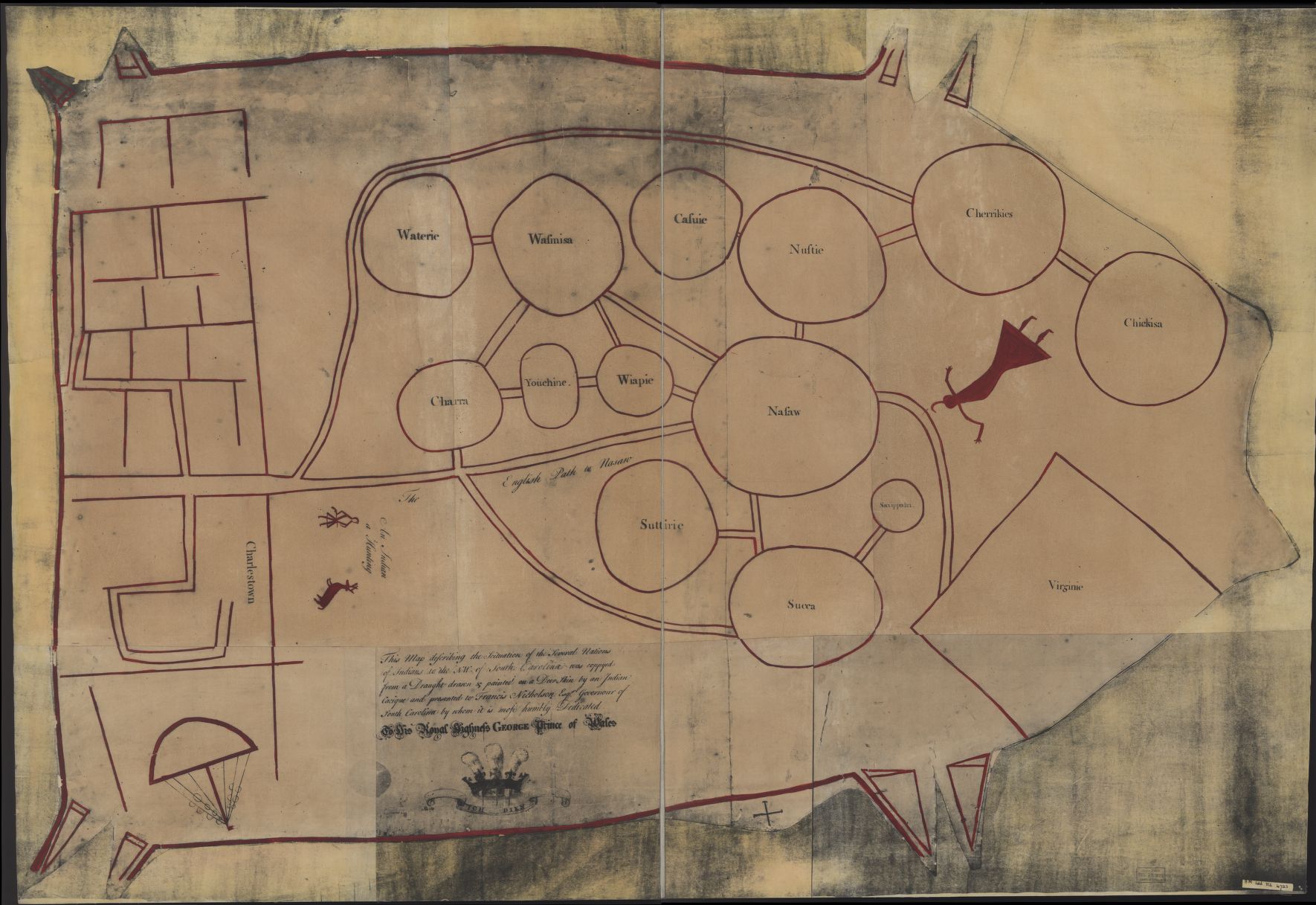

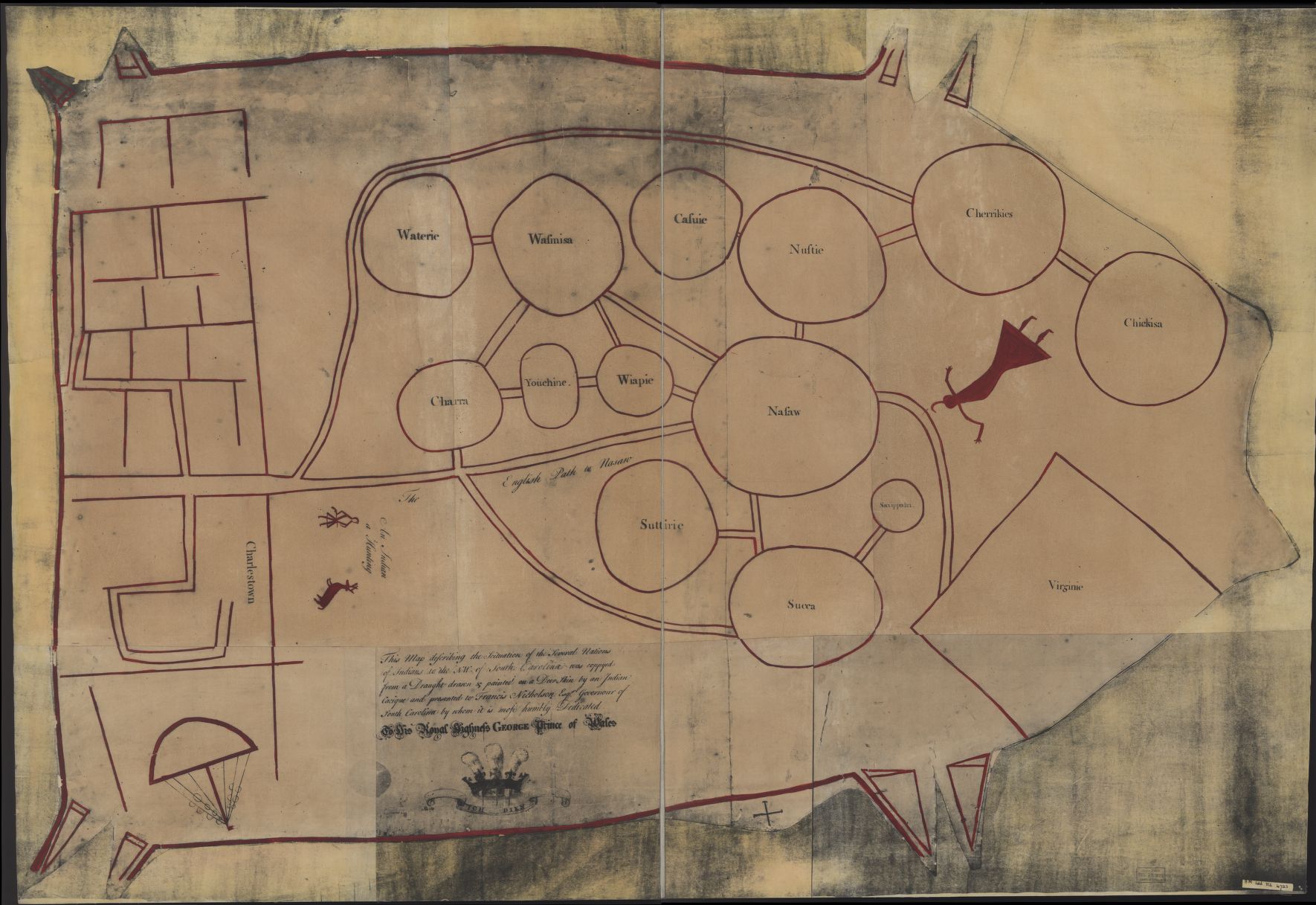

The first European contact with the Chickasaw ancestors was in 1540 when

The first European contact with the Chickasaw ancestors was in 1540 when Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

explorer Hernando de Soto encountered them and stayed in one of their towns, most likely near present-day Tupelo, Mississippi

Tupelo () is a city in and the county seat of Lee County, Mississippi, United States. With an estimated population of 38,300, Tupelo is the sixth-largest city in Mississippi and is considered a commercial, industrial, and cultural hub of North M ...

. After various disagreements, the Chickasaw attacked the De Soto expedition in a nighttime raid, nearly destroying the force. The Spanish moved on quickly.

The Chickasaw began to establish trading relationships with English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

colonists in the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

after that colony was established in 1670. After acquiring firearms from colonial merchants in Carolina, Chickasaw raiders began to attack settlements belonging to a rival tribe, the Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, in order to acquire captives which they sold to the colonists. These raids largely subsided after the Choctaw acquired firearms of their own from the French.

Allied with British colonists in the Southern Colonies, the Chickasaw were often at war with the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and the Choctaw in the 18th century, such as in the Battle of Ackia

The Chickasaw Campaign of 1736 consisted of two pitched battles by the French and allies against Chickasaw fortified villages in present-day Northeast Mississippi. Under the overall direction of the governor of Louisiana, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyn ...

on May 26, 1736. Skirmishes continued until France ceded its claims to the region east of the Mississippi River after being defeated by the British in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

(called the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

in North America).

Following the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, in 1793–94, Chickasaw fought as allies of the new United States under General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

against the Indians of the old Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. The Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

and other, allied Northwest Indians were defeated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their British allies, against the nascent United States ...

on August 20, 1794.

A 19th-century historian, Horatio Cushman, wrote, "Neither the Choctaws nor Chicksaws ever engaged in war against the American people, but always stood as their faithful allies." Cushman believed the Chickasaw, along with the Choctaw, may have had origins in present-day Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and migrated north.

That theory does not have consensus; archeological research, as noted above, has revealed the peoples had long histories in the Mississippi area and independently developed complex cultures.

Tribal lands

In 1797, a general appraisal of the tribe and its territorial bounds was made by Abraham Bishop of New Haven, who wrote:United States relations

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

(first U.S. President) and Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the ...

(first U.S. Secretary of War) proposed the cultural transformation of Native Americans.

Washington believed that Native Americans were equals, but that their society was inferior. He formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process, and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

continued it.

Historian Robert Remini wrote, "They presumed that once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans."

Washington's six-point plan included impartial justice toward Indians; regulated buying of Indian lands; promotion of commerce; promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Indian society; presidential authority to give presents; and punishing those who violated Indian rights.

The government-appointed Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

s, such as Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins (August 15, 1754June 6, 1816) was an American planter, statesman and a U.S. Indian agent He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a United States Senator from North Carolina, having grown up among the planter elite. ...

, who became Superintendent of Indian Affairs for all the territory south of the Ohio River. He and other agents lived among the Indians to teach them, through example and instruction, how to live like whites. Hawkins married a Muscogee Creek

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsFort Hampton in 1810 in present-day

The Chickasaw signed the

The Chickasaw signed the

This was known as the "

, Chickasaw Letters -- 1832, Chickasaw Historical Research Website (Kerry M. Armstrong), accessed 12 December 2011 After Levi's death in 1834, the Chickasaw people were forced upon the

Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in

Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in  When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by

When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they

Te Ata

," ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. (accessed October 17, 2013) * Tishomingo_(Chickasaw_leader), properly Tishu Miko(chief officer or guard of the king), sub-chief prior to removal * Fred Waite, cowboy and Chickasaw Nation statesman * Kevin K. Washburn, Assistant U.S. Secretary for Indian Affairs under Barack Obama * Montford Johnson, famous cattle rancher. In April 2020, Montford was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[35]

The Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma

official site

Chickasaw.tv

The online video network of the Chickasaw Nation.

Chickasaw Nation Industries (government contracting arm of the Chickasaw Nation)

"Chickasaws: The Unconquerable People", a brief history by Greg O'Brien, Ph.D.

Pashofa recipe

Tanshpashofa recipe

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Chickasaw

{{authority control Chickasaw, Native American tribes in Alabama Native American tribes in Mississippi Native American tribes in Oklahoma South Appalachian Mississippian culture Native Americans in the American Revolution

Limestone County, Alabama

Limestone County is a county of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the county's population was 103,570. Its county seat is Athens. The county is named after Limestone Creek. Limestone County is included in the Huntsville, AL Metro ...

. The fort was designed to keep settlers out of Chickasaw territory and was one of the few forts constructed in the United States to protect Native American land claims.

Treaty of Hopewell (1786)

The Chickasaw signed the

The Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Hopewell

Three agreements, each known as the Treaty of Hopewell, were signed between representatives of the Congress of the United States and the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw peoples, were negotiated and signed at the Hopewell plantation in South Caro ...

in 1786. Article 11 of that treaty states: "The hatchet shall be forever buried, and the peace given by the United States of America, and friendship re-established between the said States on the one part, and the Chickasaw nation on the other part, shall be universal, and the contracting parties shall use their utmost endeavors to maintain the peace given as aforesaid, and friendship re-established." Benjamin Hawkins attended this signing.

Treaty of 1818

In 1818, leaders of the Chickasaw signed several treaties, including theTreaty of Tuscaloosa

The Treaty of Tuscaloosa was signed in October 1818, and ratified by congress in January 1819. endorsed by President James Monroe. It was one of a series of treaties made between the Chickasaw Indians and the United States that year. The Treaty ...

, which ceded all claims to land north of the southern border of Tennessee up to the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

(the southern border of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

and the Illinois Territory

The Territory of Illinois was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 1, 1809, until December 3, 1818, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Illinois. Its ca ...

).Pate, James C. ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. "Chickasaw." Retrieved December 27, 201This was known as the "

Jackson Purchase

The Jackson Purchase, also known as the Purchase Region or simply the Purchase, is a region in the U.S. state of Kentucky bounded by the Mississippi River to the west, the Ohio River to the north, and the Tennessee River to the east.

Jackson's ...

." The Chickasaw were allowed to retain a four-square-mile reservation but were required to lease the land to European immigrants.

Colbert legacy (19th century)

In the mid-18th century, an American-born trader of Scots and Chickasaw ancestry by the name of James Logan Colbert settled in the Muscle Shoals area of Mississippi. He lived there for the next 40 years, where he married three high-ranking Chickasaw women in succession. Chickasaw chiefs and high-status women found such marriages of strategic benefit to the tribe, as it gave them advantages with traders over other groups. Colbert and his wives had numerous children, including seven sons: William, Jonathan, George, Levi, Samuel, Joseph, and Pittman (or James). Six survived to adulthood (Jonathan died young.) The Chickasaw had amatrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's Lineage (anthropology), lineage – and which can in ...

system, in which children were considered born into the mother's clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

; and they gained their status in the tribe from her family. Property and hereditary leadership passed through the maternal line, and the mother's eldest brother was the main male mentor of the children, especially of boys. Because of the status of their mothers, for nearly a century, the Colbert-Chickasaw sons and their descendants provided critical leadership during the tribe's greatest challenges. They had the advantage of growing up bilingual.

Of these six sons, William "Chooshemataha" Colbert (named after James Logan's father, Chief/Major William d'Blainville "Piomingo" Colbert) served with General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

during the Creek Wars

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama ...

of 1813–14. He also had served during the Revolutionary wars and received a commission from President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

in 1786 along with his namesake grandfather. His brothers Levi

Levi (; ) was, according to the Book of Genesis, the third of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's third son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Levi (the Levites, including the Kohanim) and the great-grandfather of Aaron, Moses and M ...

("Itawamba Mingo") and George Colbert Chief George Colbert, also known as ''Tootemastubbe'' in Chickasaw (c. 1764–1839), was a leader and war chief of the Chickasaw people in the early 19th century, then occupying territory in what are now the jurisdictions of Alabama and Mississippi. ...

("Tootesmastube") also had military service in support of the United States. In addition, the two each served as interpreters and negotiators for chiefs of the tribe during the period of removal. Levi Colbert served as principal chief, which may have been a designation by the Americans, who did not understand the decentralized nature of the chiefs' council, based on the tribe reaching broad consensus for major decisions. An example is that more than 40 chiefs from the Chickasaw Council, representing clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

and villages, signed a letter in November 1832 by Levi Colbert to President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, complaining about treaty negotiations with his appointee General John Coffee

John R. Coffee (June 2, 1772 – July 7, 1833) was an American planter of Irish descent, and state militia brigadier general in Tennessee. He commanded troops under General Andrew Jackson during the Creek Wars (1813–14) and during the Battle o ...

."Levi Colbert to President Andrew Jackson, 22 NOV 1832", Chickasaw Letters -- 1832, Chickasaw Historical Research Website (Kerry M. Armstrong), accessed 12 December 2011 After Levi's death in 1834, the Chickasaw people were forced upon the

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

. His brother, George Colbert, reluctantly succeeded him as chief and principal negotiator, because he was bilingual and bicultural. George "Tootesmastube" Colbert never reached the Chickasaw's "Oka Homa" (red waters); he died on Choctaw territory, Fort Towson

Fort Towson was a frontier outpost for United States Army, Frontier Army Quartermasters along the Army on the Frontier, Permanent Indian Frontier located about two miles (3 km) northeast of the present community of Fort Towson, Oklahoma. Loc ...

, en route.

Treaty of Pontotoc Creek and Removal (1832-1837)

In 1832 after the state of Mississippi declared its jurisdiction over the Chickasaw Indians, outlawing tribal self-governance, Chickasaw chiefs assembled at the national council house on October 20, 1832 and signed theTreaty of Pontotoc Creek

The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek was a treaty signed on October 20, 1832 by representatives of the United States and the Chiefs of the Chickasaw Nation assembled at the National Council House on Pontotoc Creek in Pontotoc, Mississippi. The treaty cede ...

, ceding their remaining Mississippi territory to the U.S. and agreeing to find land and relocate west of the Mississippi River. Between 1832 and 1837, the Chickasaw would make further negotiations and arrangements for their removal.  Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in

Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

from the previously removed Choctaw. They paid the Choctaw $530,000 for the westernmost part of their land. The first group of Chickasaw moved in 1837. For nearly 30 years, the US did not pay the Chickasaw the $3 million it owed them for their historic territory in the Southeast.

The Chickasaw gathered at Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

, on July 4, 1837, with all of their portable assets: belongings, livestock, and enslaved African Americans. Three thousand and one Chickasaw crossed the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, following routes established by the Choctaw and Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

. During the journey, often called the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

by all the Southeast tribes that had to make it, more than 500 Chickasaw died of dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

.

When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by

When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by Holmes Colbert

Holmes Colbert was a 19th-century leader of the Chickasaw Nation in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Of mixed European and Chickasaw ancestry, Colbert was born to his mother's Chickasaw clan and gained significance in the tribe's history through ...

.

After several decades of mistrust between the two peoples, in the twentieth century, the Chickasaw re-established their independent government. They are federally recognized as the Chickasaw Nation. The government is headquartered in Ada, Oklahoma

Ada is a city in and the county seat of Pontotoc County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 16,481 at the 2020 United States Census. The city was named for Ada Reed, the daughter of an early settler, and was incorporated in 1901. Ada is ...

.

American Civil War (1861)

The Chickasaw Nation was the first of the Five Civilized Tribes to become allies of theConfederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

.

In addition, they resented the United States government, which had forced them off their lands and failed to protect them against the Plains tribes in the West. In 1861, as tensions rose related to the sectional conflict, the US Army abandoned Fort Washita

Fort Washita is the former United States military post and National Historic Landmark located in Durant, Oklahoma on SH 199. Established in 1842 by General (later President) Zachary Taylor to protect citizens of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Natio ...

, leaving the Chickasaw Nation defenseless against the Plains tribes. Confederate officials recruited the American Indian tribes with suggestions of an Indian state if they were victorious in the Civil War.

The Chickasaw passed a resolution allying with the Confederacy, which was signed by Governor Cyrus Harris on May 25, 1861.

At the beginning of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Albert Pike

Albert Pike (December 29, 1809April 2, 1891) was an American author, poet, orator, editor, lawyer, jurist and Confederate general who served as an associate justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court in exile from 1864 to 1865. He had previously se ...

was appointed as Confederate envoy to Native Americans. In this capacity, he negotiated several treaties, including the Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws

The Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws was a treaty signed on July 12, 1861 between the Choctaw and Chickasaw ( American Indian) and the Confederate States. At the beginning of the American Civil War, Albert Pike was appointed as Confederate env ...

in July 1861. The treaty covered sixty-four terms, covering many subjects such as Choctaw and Chickasaw nation sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

, Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

citizenship possibilities and an entitled delegate in the House of Representatives of the Confederate States of America. Because the Chickasaw sided with the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, they had to forfeit some of their land afterward. In addition, the US renegotiated their treaty, insisting on their emancipation of slaves and offering citizenship to those who wanted to stay in the Chickasaw Nation. If they returned to the United States, they would have US citizenship.

Government

The Chickasaws were first combined with theChoctaw Nation

The Choctaw Nation ( Choctaw: ''Chahta Okla'') is a Native American territory covering about , occupying portions of southeastern Oklahoma in the United States. The Choctaw Nation is the third-largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

and their area was called the Chickasaw District. Although originally the western boundary of the Choctaw Nation extended to the 100th meridian, virtually no Chickasaw lived west of the Cross Timbers

The term Cross Timbers, also known as Ecoregion 29, Central Oklahoma/Texas Plains, is used to describe a strip of land in the United States that runs from southeastern Kansas across Central Oklahoma to Central Texas. Made up of a mix of prairie ...

. The area was subject to continual raiding by the Indians on the Southern Plains. The United States eventually leased the area between the 100th and 98th meridians for the use of the Plains tribes. The area was referred to as the "Leased District".

Treaties

Post–Civil War

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they emancipate

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure Economic, social and cultural rights, economic and social rights, civil and political rights, pol ...

the enslaved African Americans and provide full citizenship to those who wanted to stay in the Chickasaw Nation.

These people and their descendants became known as the Chickasaw Freedmen. Descendants of the Freedmen continue to live in Oklahoma. Today, the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Association of Oklahoma represents the interests of freedmen descendants in both of these tribes.

But the Chickasaw Nation never granted citizenship to the Chickasaw freedmen. The only way that African Americans could become citizens at that time was to have one or more Chickasaw parents or to petition for citizenship and go through the process available to other non-Natives, even if they were of known partial Chickasaw descent in an earlier generation. Because the Chickasaw Nation did not provide citizenship to their freedmen after the Civil War (it would have been akin to formal adoption of individuals into the tribe), they were penalized by the U.S. Government. It took more than half of their territory, with no compensation. They lost territory that had been negotiated in treaties in exchange for their use after removal from the Southeast.

State-recognized tribes

TheChaloklowa Chickasaw Indian People

The Chaloklowa Chickasaw Indian People or Chaloklowa Chickasaw is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and "state-recognized group" not to be confused with a state-recognized tribe. The state of South Carolina gave them the state-recognized group an ...

, made up of descendants of Chickasaw who did not leave the Southeast, were recognized as a "state-recognized group" in 2005 by South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. They are headquartered in Hemingway, South Carolina

Hemingway is a town in Williamsburg County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 459 at the 2010 census.

History

Hemingway was created from a crossroads community named Lamberts in 1911 by Dr. W. C. Hemingway, in an effort to secure ...

. In 2003, they unsuccessfully petitioned the US Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

to try to gain federal recognition as an Indian tribe.

Culture

The suffix ''-mingo'' (Chickasaw: ''minko'') is used to identify a chief. For example, '' Tishomingo'' was the name of a famous Chickasaw chief. The towns of Tishomingo inMississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

were named for him, as was Tishomingo County

Tishomingo County is a county located in the northeastern corner of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 19,593. Its county seat is Iuka.

History

Tishomingo County was organized February 9, 1836, from Ch ...

in Mississippi. South Carolina's Black Mingo Creek

Black Mingo Creek is a tributary to the Black River in coastal South Carolina. The creek derives its name from the Mingo, a tribe that once inhabited the fork made by the junction of Indiantown Swamp and Black Mingo Creek.

It is a blackwater riv ...

was named after a colonial Chickasaw chief, who controlled the lands around it as a hunting ground. Sometimes the suffix is spelled ''minco'', but this most often occurs in older literary references.

In 2010, the tribe opened the Chickasaw Cultural Center

The Chickasaw Cultural Center is a campus located in Sulphur, Oklahoma near the Chickasaw National Recreation Area. Its campus is home to historical museum buildings with interactive exhibits on Chickasaw tribal history, traditional dancing, and ...

in Sulphur, Oklahoma

Sulphur is a city in and county seat of Murray County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 4,929 at the 2010 census, a 3.4 percent gain over the figure of 4,794 in 2000. The area around Sulphur has been noted for its mineral springs, sin ...

. It includes the ''Chikasha Inchokka’'' Traditional Village, Honor Garden, Sky and Water pavilion, and several in-depth exhibits about the diverse culture of the Chickasaw.

Notable Chickasaw

*Bill Anoatubby

Bill Anoatubby (born November 8, 1945) is the Governor of the Chickasaw Nation, a position he has held since 1987. From 1979 to 1987, Anoatubby served two terms as Lieutenant Governor of the Chickasaw Nation in the administration of Governor Overt ...

, Governor of the Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation (Chickasaw language, Chickasaw: Chikashsha I̠yaakni) is a federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe, with its headquarters located in Ada, Oklahoma in th ...

since 1987

* Jack Brisco

Freddie Joe "Jack" Brisco (September 21, 1941 – February 1, 2010) was an American amateur wrestling, amateur and Professional wrestling, professional wrestler. As an amateur for Oklahoma State, Brisco was two-time All-American and won the Natio ...

and Jerry Brisco

Floyd Gerald "Jerry" Brisco (born September 19, 1946) is an American retired professional wrestler. Brisco is best known for his time in the wrestling promotion WWE, where he was a backstage producer, and, during the 1990s, an on-screen character, ...

, pro wrestling tag team

* Jodi Byrd

Jodi Ann Byrd is an Americans, American Native Americans in the United States, indigenous academic. They recently became an associate professor of Literatures in English at Cornell University, where they also hold an affiliation with the American ...

, Literary and political theorist

* Edwin Carewe

Edwin Carewe (March 3, 1883 – January 22, 1940) was an American motion picture director, actor, producer, and screenwriter. His birth name was Jay John Fox; he was born in Gainesville, Texas.

Career

After brief studies at the Universities of ...

(1883–1940), movie actor and director

* Charles David Carter

Charles David Carter (August 16, 1868 in Chickasaw – April 9, 1929) was a Native American politician elected as U.S. Representative from Oklahoma, serving from 1907 to 1927. During this period, he also served as Mining Trustee for Indian Terri ...

, Democratic U. S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washingto ...

man from Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

* Levi Colbert

Levi Colbert (1759–1834), also known as ''Itawamba'' in Chickasaw, was a leader and chief of the Chickasaw nation. Colbert was called ''Itte-wamba Mingo'', meaning ''bench chief''. He and his brother George Colbert were prominent interpreters ...

, Chickasaw language translator

* Tom Cole

Thomas Jeffery Cole (born April 28, 1949) is the U.S. representative for , serving since 2003. He is a member of the Republican Party and serves as Deputy Minority Whip. The chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) fro ...

, Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

U.S. Congressman from Oklahoma

* Don Cheadle

Donald Frank Cheadle Jr. (; born November 29, 1964) is an American actor. He is the recipient of multiple accolades, including two Grammy Awards, a Tony Award, two Golden Globe Awards and two Screen Actors Guild Awards. He has also earned ...

, Chickasaw Freedmen actor

* Molly Culver

Molly, Mollie or mollies may refer to:

Animals

* ''Poecilia'', a genus of fishes

** ''Poecilia sphenops'', a fish species

* A female mule (horse–donkey hybrid)

People

* Molly (name) or Mollie, a female given name, including a list of persons ...

, actress

* Kent DuChaine, American Blues singer and guitarist

* Hiawatha Estes

Hiawatha Thompson Estes (January 26, 1918 – May 8, 2003) was a California-based architect and author known for designing a large number of variations of the ubiquitous post-war ranch home, mass marketing plans of them, and publishing a number o ...

, architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

* Bee Ho Gray

Bee Ho Gray (born Emberry Cannon Gray on April 7, 1885, in Leon, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory – August 3, 1951, in Pueblo, Colorado) was a Western performer who spent 50 years displaying his skills in Wild West shows, vaudeville, circus, s ...

, actor

* John Herrington

John Bennett Herrington (born September 14, 1958, in Chickasaw Nation) is a retired United States Naval Aviator, engineer and former NASA astronaut. In 2002, Herrington became the first enrolled member of a Native American tribe to fly in spac ...

, astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member aboard a spacecraft. Although generally r ...

; first Native American in space

''In Space'' is the fourth and final studio album by American rock group Big Star, released in 2005. It was the first new studio recording by the band since ''Third/Sister Lovers'', which was recorded in 1974.

The album featured original Big S ...

* Linda Hogan, Writer-in-Residence of the Chickasaw Nation

* Miko Hughes

Miko John Hughes (born February 22, 1986) is an American actor known for his film roles as a child, such as Gage Creed in ''Pet Sematary'' (1989), ''Kindergarten Cop'' (1990), ''Apollo 13'' (1995), ''Spawn'' (1997), ''Mercury Rising'' (1998), '' ...

, actor

* Julia Jones

Julia Jones (born January 23, 1981) is an American actress, known for playing Leah Clearwater in '' The Twilight Saga'' films and Kohana in the HBO series ''Westworld''. She also co-stars on '' Dexter: New Blood''.

Early life and education

Jul ...

, actress

* Kyle Keller, Head Men's Basketball Coach, Stephen F. Austin Lumberjacks

The Stephen F. Austin Lumberjacks and Ladyjacks are composed of 16 teams representing Stephen F. Austin State University (SFA) in intercollegiate athletics. Stephen F. Austin teams participate in the Division I as a member of the Western Athle ...

* Neal A. McCaleb

Neal A. "Chief" McCaleb (born 1935) is an American civil engineer and Republican politician from Oklahoma. A member of the Chickasaw Nation, McCaleb served in several positions in the Oklahoma state government and then as the Assistant Secret ...

, Assistant U.S. Secretary for Indian Affairs (overseeing the BIA) under George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

* Wahoo McDaniel

Edward Hugh McDaniel (June 19, 1938 – April 18, 2002) was an American Choctaw-Chickasaw professional American football player and professional wrestler better known by his ring name Wahoo McDaniel. He is notable for having held the NWA United S ...

, pro wrestler

Professional wrestling is a form of theater that revolves around staged wrestling matches. The mock combat is performed in a ring similar to the kind used in boxing, and the dramatic aspects of pro wrestling may be performed both in the ring o ...

, American Football League

The American Football League (AFL) was a major professional American football league that operated for ten seasons from 1960 until 1970, when it merged with the older National Football League (NFL), and became the American Football Conference. ...

player

* Leona Mitchell

Leona Pearl Mitchell (born October 13, 1949, Enid, Oklahoma) is an American operatic Grammy Award-winning soprano who sang for 18 seasons as a leading spinto soprano at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In her home state of Oklahoma, she rece ...

, opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

singer

* Rodd Redwing

Rodd Redwing (August 24, 1904 – May 29, 1971) was born Webb Richardson on August 24, 1904 in Tennessee, USA. His father, Ulysses William Richardson (b. 1873), was Black and was an elevator man from Tennessee. His mother, Lillian Webb (b. 1 ...

, actor

* Rebecca Sandefur

Rebecca Leigh Sandefur is an American sociologist. She is Professor in the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University and a faculty fellow of the American Bar Foundation (ABF). At the ABF, she founded the access to justice ...

, Sociologist and MacArthur Fellow

The MacArthur Fellows Program, also known as the MacArthur Fellowship and commonly but unofficially known as the "Genius Grant", is a prize awarded annually by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation typically to between 20 and 30 ind ...

* Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate, composer and pianist

* Te Ata Fisher, Te Ata, traditional Indian storyteller and actressHarris, Rodger.Te Ata

," ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. (accessed October 17, 2013) * Tishomingo_(Chickasaw_leader), properly Tishu Miko(chief officer or guard of the king), sub-chief prior to removal * Fred Waite, cowboy and Chickasaw Nation statesman * Kevin K. Washburn, Assistant U.S. Secretary for Indian Affairs under Barack Obama * Montford Johnson, famous cattle rancher. In April 2020, Montford was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[35]

See also

*Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation (Chickasaw language, Chickasaw: Chikashsha I̠yaakni) is a federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe, with its headquarters located in Ada, Oklahoma in th ...

* Chickasaw language

* List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

* Chickasaw Wars

* Pashofa

* Perry Cohea

Footnotes

Further reading

* James F. Barnett, Jr., ''Mississippi's American Indians.'' Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2012. * Colin G. Calloway, ''The American Revolution in Indian Country.'' Cambridge University Press, 1995. * Daniel F. Littlefield, Jr., ''The Chickasaw Freedmen: A People Without a Country.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980.External links

The Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma

official site

Chickasaw.tv

The online video network of the Chickasaw Nation.

Chickasaw Nation Industries (government contracting arm of the Chickasaw Nation)

"Chickasaws: The Unconquerable People", a brief history by Greg O'Brien, Ph.D.

Pashofa recipe

Tanshpashofa recipe

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Chickasaw

{{authority control Chickasaw, Native American tribes in Alabama Native American tribes in Mississippi Native American tribes in Oklahoma South Appalachian Mississippian culture Native Americans in the American Revolution