Chickamauga Cherokee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Chickamauga Cherokee refers to a group that separated from the greater body of the

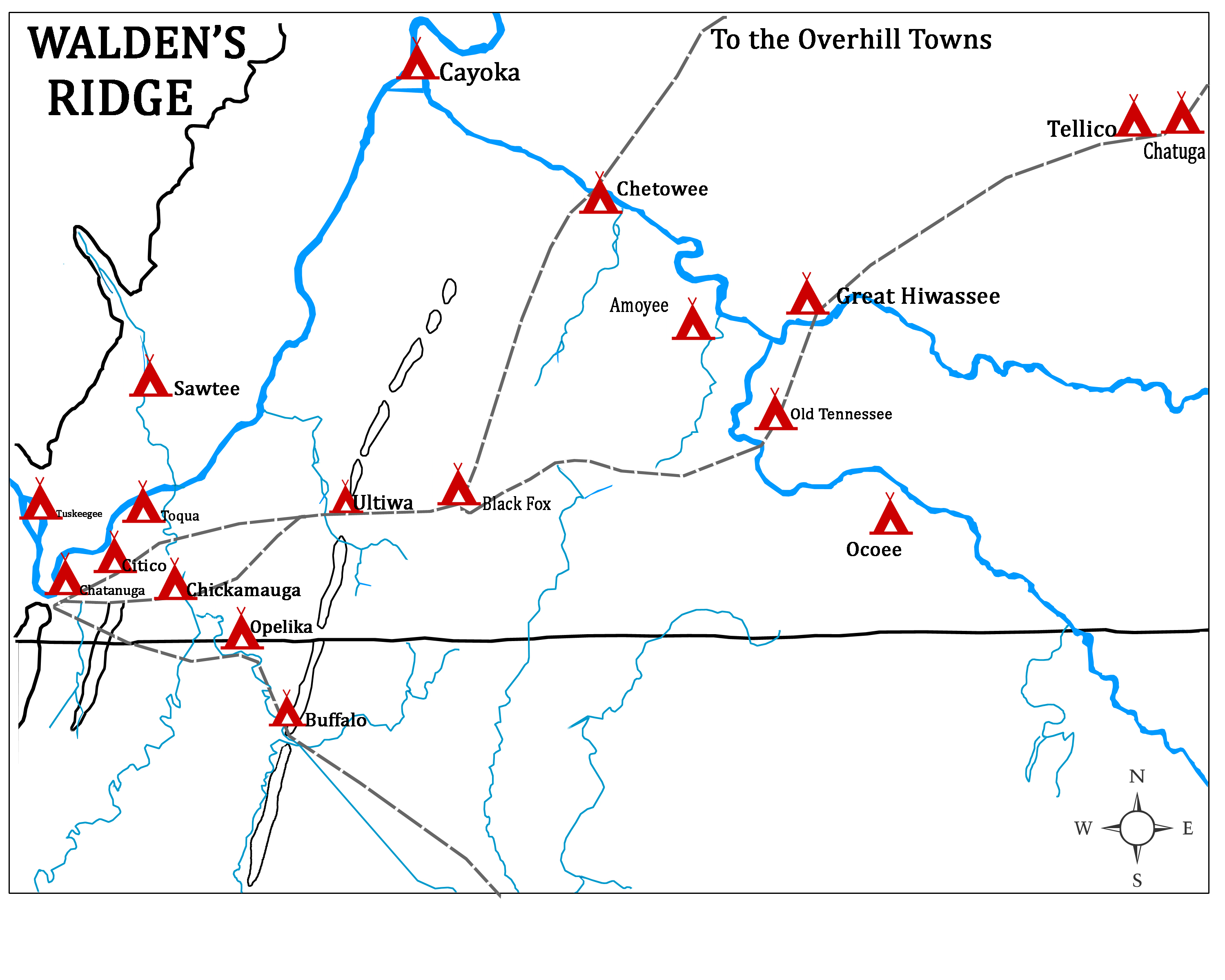

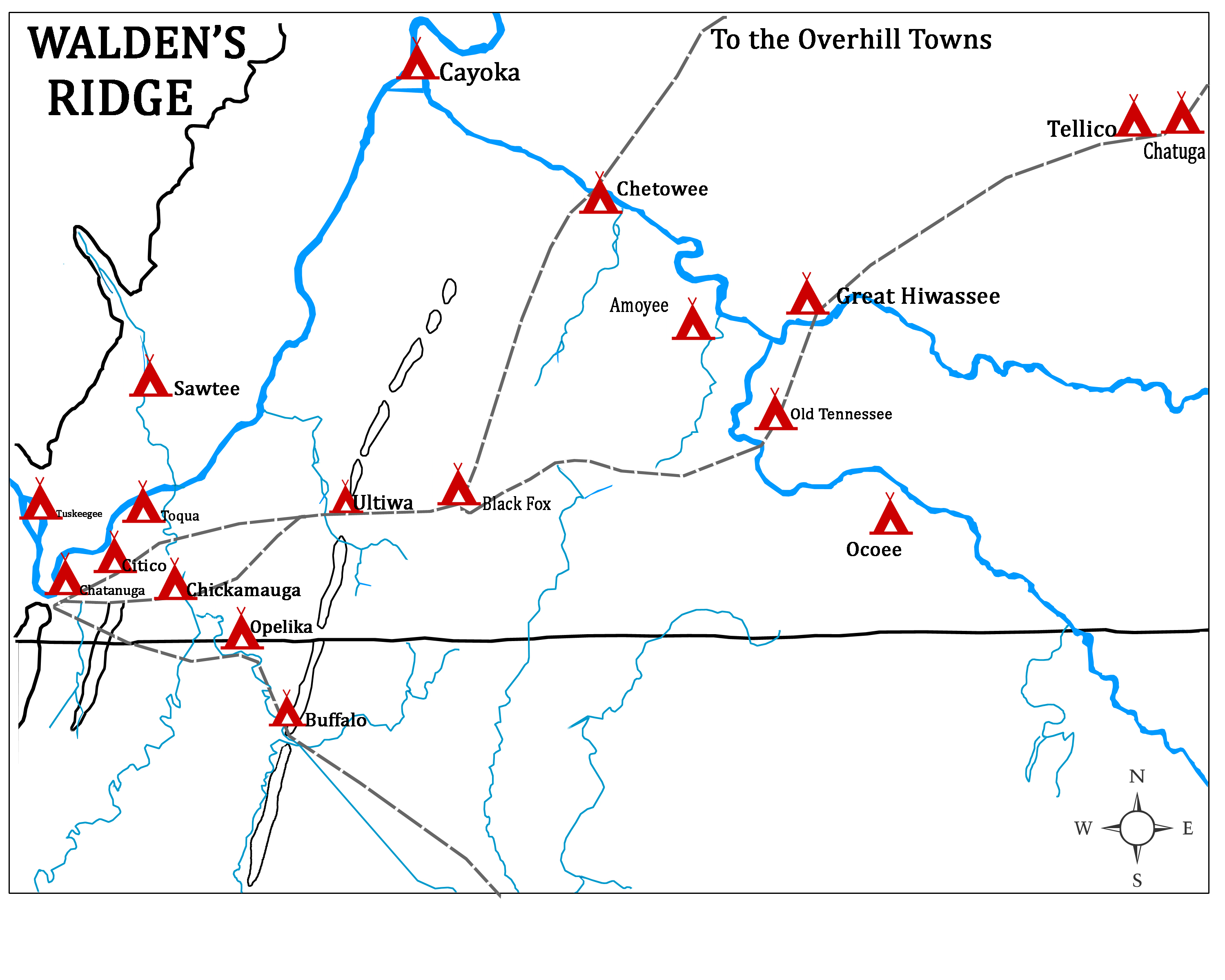

During the winter of 1776–77, Cherokee followers of Dragging Canoe, who had supported the British at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, moved down the Tennessee River and away from their historic Overhill Cherokee towns. They established nearly a dozen new towns in this frontier area in an attempt to gain distance from encroaching European-American settlers.

Dragging Canoe and his followers settled at the place where the

During the winter of 1776–77, Cherokee followers of Dragging Canoe, who had supported the British at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, moved down the Tennessee River and away from their historic Overhill Cherokee towns. They established nearly a dozen new towns in this frontier area in an attempt to gain distance from encroaching European-American settlers.

Dragging Canoe and his followers settled at the place where the

For a decade or more after the end of the hostilities, the northern section of the Upper Towns had their own council and acknowledged the top headman of the Overhill Towns as their leader. They gradually had to move south because they ceded their land to the United States.

John McDonald returned to his old home on the Chickamauga River, across from Old Chickamauga Town, and lived there until selling it in 1816. It was purchased by the

For a decade or more after the end of the hostilities, the northern section of the Upper Towns had their own council and acknowledged the top headman of the Overhill Towns as their leader. They gradually had to move south because they ceded their land to the United States.

John McDonald returned to his old home on the Chickamauga River, across from Old Chickamauga Town, and lived there until selling it in 1816. It was purchased by the

By the time John Norton (a

By the time John Norton (a

''The Bloody Ground: The Chickamauga Wars and Trans–Appalachian Expansion, 1776-1794''

Kane, Sean Patrick; retrieved July 2021; PDF format/download.

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The majority of the Cherokee people wished to make peace with the Americans near the end of 1776, following several military setbacks and American reprisals.

The followers of the skiagusta

A skiagusta (ᎠᏍᎦᏯᎬᏍᏔ, also ''asgayagvsta'', also ''skyagunsta'', also ''skayagusta''), (ᎠᏍᎦᏯᎬᏍᏔ, ''asgayagvsta''), also spelled ''skyagusta'', ''skiagunsta'', ''skyagunsta'', ''skayagunsta'', ''skygusta'', ''askayagust ...

(or red chief), Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

, moved with him in the winter of 1776–77 down the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, ...

away from their historic Overhill Cherokee

Overhill Cherokee was the term for the Cherokee people located in their historic settlements in what is now the U.S. state of Tennessee in the Southeastern United States, on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. This name was used by 1 ...

towns. Relocated in a more isolated area, they established 11 new towns in order to gain distance from colonists' encroachments. The frontier Americans associated Dragging Canoe and his band with their new town on Chickamauga Creek

Chickamauga Creek refers to two short tributaries of the Tennessee River, which join the river near Chattanooga, Tennessee. The two streams are North Chickamauga Creek and South Chickamauga Creek, joining the Tennessee from the north and south s ...

and began to refer to them as the ''Chickamaugas.'' Five years later, the Chickamauga moved further west and southwest into present-day Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, establishing five larger settlements. They were then more commonly known as the ''Lower Cherokee''. This term was closely associated with the people of these "Five Lower Towns".

Migration

"Chickamauga" towns

During the winter of 1776–77, Cherokee followers of Dragging Canoe, who had supported the British at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, moved down the Tennessee River and away from their historic Overhill Cherokee towns. They established nearly a dozen new towns in this frontier area in an attempt to gain distance from encroaching European-American settlers.

Dragging Canoe and his followers settled at the place where the

During the winter of 1776–77, Cherokee followers of Dragging Canoe, who had supported the British at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, moved down the Tennessee River and away from their historic Overhill Cherokee towns. They established nearly a dozen new towns in this frontier area in an attempt to gain distance from encroaching European-American settlers.

Dragging Canoe and his followers settled at the place where the Great Indian Warpath

The Great Indian Warpath (GIW)—also known as the Great Indian War and Trading Path, or the Seneca Trail—was that part of the network of trails in eastern North America developed and used by Native Americans which ran through the Great Appala ...

crossed the Chickamauga Creek, near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

. They named their town Chickamauga after the stream. The entire adjacent region was referred to in general as the Chickamauga area. American settlers adopted that term to refer to the militant Cherokee in this area as "Chickamaugas."

In 1782, militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

forces under John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

and William Campbell destroyed the eleven Cherokee towns. Dragging Canoe led his people further down the Tennessee River, establishing five new, ''Lower Cherokee'' towns.

After the Revolutionary War, westward migration increased by pioneers from the new states of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

.

"Five Lower Towns"

Dragging Canoe relocated his people west and southwest, into new settlements in Georgia centered onRunning Water

Tap water (also known as faucet water, running water, or municipal water) is water supplied through a tap, a water dispenser valve. In many countries, tap water usually has the quality of drinking water. Tap water is commonly used for drinking, ...

(now Whiteside) on Running Water Creek. The other towns founded at this time were: Nickajack (near the cave of the same name), Long Island (on the Tennessee River), Crow Town (at the mouth of Crow Creek), and Lookout Mountain

Lookout Mountain is a mountain ridge located at the northwest corner of the U.S. state of Georgia, the northeast corner of Alabama, and along the southeastern Tennessee state line in Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain was the scene of the 18th-cen ...

Town (at the site of the current Trenton, Georgia

Trenton is a city and the only incorporated municipality in Dade County, Georgia, United States—and as such, it serves as the county seat. The population was 2,195 at the 2020 census. Trenton is part of the Chattanooga, Tennessee–GA Metropo ...

). In time more towns developed to the south and west, and all these were referred to as the Lower Towns.

Constant war

The Chickamauga Cherokee became known for their uncompromising enmity againstUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

(US) settlers, who had pushed them out of their traditional territory. From Running Water town, Dragging Canoe led attacks on white settlements all over the American Southeast

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the southern United States and the southern por ...

.

The Chickamauga/Lower Cherokee and the frontiersmen were continuously at war until 1794. Chickamauga warriors raided as far as Indiana, Kentucky, and Virginia (along with members of the Northwestern Confederacy

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to it ...

—which they helped establish). Because of a growing belief in the Chickamauga cause, as well as the US destruction of homes of other Native Americans, a majority of the Cherokee eventually came to be allied against the United States.

Following the death of Dragging Canoe in 1792, his hand-picked successor, John Watts, assumed control of the Lower Cherokee. Under Watts's lead, the Cherokee continued their policy of Indian unity and hostility toward European Americans. Watts moved his base of operations to Willstown to be closer to his Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsPensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

with the Spanish governor of West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

, Arturo O'Neill de Tyrone

Arturo O'Neill de Tyrone y O'Kelly (January 8, 1736 – December 9, 1814) was an Irish-born Spanish colonel who served the Spanish crown as governor of several places in New Spain. He came from a lineage that occupied prominent European po ...

, for arms and supplies with which to carry on the war.

Cherokee interactions

The Chickamauga Towns and the later Lower Towns were no different from the rest of the Cherokee than were other groups of historic settlements, known as the Middle Towns, Out Towns, (original) Lower Towns, Valley Towns, or Overhill Towns, which well established on the east and western sides of theAppalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

by the time the Europeans first encountered these people. The groupings did not constitute separate political entities, as much as indicate geographic groupings. People of the Overhill and Valley towns did speak a similar dialect. The highly decentralized people based their governments in the clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

and larger town

A town is a human settlement. Towns are generally larger than villages and smaller than cities, though the criteria to distinguish between them vary considerably in different parts of the world.

Origin and use

The word "town" shares an ori ...

, where townhouse

A townhouse, townhome, town house, or town home, is a type of terraced housing. A modern townhouse is often one with a small footprint on multiple floors. In a different British usage, the term originally referred to any type of city residence ...

s were built for communal gatherings. Some of the towns were associated with nearby, smaller villages. Although there were regional councils, these had no binding powers.

Over time, the different groups of towns developed differing ideas about relations with European-Americans. In part this was based on the degree of interaction and intermarriage they had with them through trading and other partnerships.

The only "national" role which existed among Cherokee people before 1788 was that of ''First Beloved Man'', a chief negotiator from the Towns of the Cherokee most isolated from the reach of European settlers. After 1788, the people established a national council of sorts, but it met irregularly and at the time had little authority. Even after the peace of 1794, the Cherokee had five groups: the Upper Towns (formerly the Lower Towns of western Carolina and northeastern Georgia), the Overhill Towns, the Hill Towns, the Valley Towns, and the (new) Lower Towns, each with their own regional ruling councils (considered more important than the "national" council at Ustanali in Georgia).

Dragging Canoe had addressed the National Council at Ustanali, and publicly acknowledged Little Turkey as the senior leader of all the Cherokee. He was memorialized by the council following his death in 1792. Leaders of the "Chickamauga" frequently communicated with the Cherokee of other regions. They were supported in warfare against the colonists and later pioneers by warriors from the Overhill Towns. Numerous Chickamauga headmen signed treaties with the federal government, along with other leaders of Cherokee Nation.

Aftermath of the wars

Following the Treaty ofTellico Blockhouse

The Tellico Blockhouse was an early American outpost located along the Little Tennessee River in what developed as Vonore, Monroe County, Tennessee. Completed in 1794, the blockhouse was a US military outpost that operated until 1807; the garrison ...

in late 1794, leaders from the Lower Cherokee dominated national affairs of the people. When the national government of all the Cherokee Nation was organized, the first three persons to hold the office of Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

Principal Chief is today the title of the chief executives of the Cherokee Nation, of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, the three federally recognized tribes of Cherokee. In the eighteent ...

were: Little Turkey (1788–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller

Pathkiller, (died January 8, 1827) was a Cherokee warrior and Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Warrior life

PathkillerPathkiller is a Cherokee rank or title—not a name. His original name is unknown. fought against the Overmountain Men ...

(1811–1827). These men had all served as warriors under Dragging Canoe. Doublehead and Turtle-at-Home, the first two Speakers of the Cherokee National Council, had also served with Dragging Canoe.

The domination of the Cherokee Nation by the former warriors from the Lower Towns continued well into the 19th century. Even after the revolt of the young chiefs of the Upper Towns, the representatives of the Lower Towns were a major voice. The "young chiefs" of the Upper Towns who dominated that region had also previously been warriors with Dragging Canoe and Watts.

Resettling

Many of the former warriors returned to the original settlements in the Chickamauga area, some of which had already been reoccupied. They also established new towns in the area, plus several in north Georgia. Others moved into those towns established after the earlier migration. In 1799,Brother

A brother is a man or boy who shares one or more parents with another; a male sibling. The female counterpart is a sister. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to refer to non-familia ...

Steiner, a representative of the Moravian Brethren

, image = AgnusDeiWindow.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, caption = Church emblem featuring the Agnus Dei.Stained glass at the Rights Chapel of Trinity Moravian Church, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States

, main_classification = Proto-Prot ...

, met with Richard Fields (Lower Cherokee) at Tellico Blockhouse. Fields had previously served as a warrior. Steiner hired him as guide and interpreter, as the missionary had been sent south by the Brethren to scout for an appropriate location for a mission and school in the Nation. It was ultimately located at Spring Place

Spring Place (also Poinset, Springplace) is an unincorporated community in Murray County, Georgia, United States.

History

A post office was established at Spring Place in 1826. The community took its name from Spring Place Mission, a nearby Nativ ...

, on land donated by James Vann, who supported gaining some European-American education for his people. On one occasion, Steiner asked his guide, "What kind of people are the Chickamauga?" Fields laughed, then replied, "They are Cherokee, and we know no difference."Allen, Penelope; "The Fields Settlement"; Penelope Allen Manuscript; Archive Section; Chattanooga-Hamilton County Bicentennial Library; Neither the Chickamauga nor other Cherokee considered them to be distinct from the overall 18th-century Cherokee peoples.

Still others joined the remnant populations from the former Overhill towns on the Little Tennessee River that were referred to as the Upper Towns. These were centered on Ustanali in Georgia. Vann and his protégés The Ridge and Charles R. Hicks rose to be their top leaders. The leaders of these towns were the most progressive among the Cherokee, favoring extensive acculturation, formal education adapted from European Americans, and modern methods of farming.Wilkins, Thurman. ''Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People,'' pp. 33–47. (New York: Macmillan Company, 1970).

For a decade or more after the end of the hostilities, the northern section of the Upper Towns had their own council and acknowledged the top headman of the Overhill Towns as their leader. They gradually had to move south because they ceded their land to the United States.

John McDonald returned to his old home on the Chickamauga River, across from Old Chickamauga Town, and lived there until selling it in 1816. It was purchased by the

For a decade or more after the end of the hostilities, the northern section of the Upper Towns had their own council and acknowledged the top headman of the Overhill Towns as their leader. They gradually had to move south because they ceded their land to the United States.

John McDonald returned to his old home on the Chickamauga River, across from Old Chickamauga Town, and lived there until selling it in 1816. It was purchased by the Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

-based American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions for use as the Brainerd Mission

The Brainerd Mission was a Christian mission to the Cherokee in present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee. The associated Brainerd Mission Cemetery is the only part that remains, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

History

B ...

, which served as both a church (named the Baptist Church of Christ at Chickamauga) and a school offering academic and vocational training. His daughter, Mollie McDonald, and son-in-law, Daniel Ross, developed a farm and trading post near the old village of Chatanuga (Tsatanugi) from the early days of the wars. Settled near them were sons Lewis and Andrew Ross and a number of daughters. Their son John Ross, born at Turkey Town, later rose to become a principal chief, guiding the Cherokee through the Indian Removals of the 1830s and relocation to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

west of the Mississippi River.

The majority of the Lower Cherokee remained in the towns they inhabited in 1794, known as the Lower Towns, with their seat at Willstown. The former warriors of the Lower Towns dominated the political affairs of the Nation for the next twenty years. They were more conservative than leaders of the Upper Towns, adopting many elements of assimilation but keeping as many of the old ways as possible.

Roughly speaking, the Lower Towns were south and southwest of the Hiwassee River

The Hiwassee River has its headwaters on the north slope of Rocky Mountain in Towns County in the northern area of the State of Georgia. It flows northward into North Carolina before turning westward into Tennessee, flowing into the Tennessee Riv ...

along the Tennessee down to the north border of the Muscogee nation, and west of the Conasauga and the Ustanali in Georgia, while the Upper Towns were north and east of the Hiwassee and between the Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chatta ...

and the Conasauga. This latter was approximately the same area as the later Amohee, Chickamauga, and Chattooga districts of the Cherokee Nation East.

Also traditional were the settlements of the Cherokee in the highlands of western North Carolina, which had become known as the Hill Towns, with their seat at Quallatown. Similarly, the lowland Valley Towns, with their seat at Tuskquitee, were more traditional, as was the Upper Town of Etowah. It was notable both for being inhabited mostly by full-bloods (as many Cherokee of the other towns were of mixed race but identified as Cherokee) and for being the largest town in the Cherokee Nation. The Overhill towns remaining along the Little Tennessee remained more or less autonomous, and kept their seat at Chota.

All five regions had their own councils. These were more important to their people than the nominal nation council until the reorganization in 1810, which took place after the national council held that year at Willstown.

Peacetime leaders of the Lower Towns

John Watts remained the head of the council of the Lower Cherokee at Willstown until his death in 1802. Afterward, Doublehead, already a member of the triumvirate, moved into that position and held it until his death in 1807. He was assassinated by The Ridge, Alexander Saunders (best friend to James Vann), and John Rogers. The latter was a white former trader who had first come west with Dragging Canoe in 1777. By 1802 he was considered a member of the nation, and was allowed to sit on the council. He was succeeded on the council by The Glass, who was also assistant principal chief of the nation to Black Fox. The Glass was head of the Lower Towns' council until the unification council of 1810. By the time John Norton (a

By the time John Norton (a Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

* Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

* Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been ...

of Cherokee and Scottish ancestry) visited the area in 1809–1810, many of the formerly militant Cherokee of the Lower Towns were among the most assimilated members. James Vann, for instance, became a major planter, holding more than 100 African-American slaves, and was one of the wealthiest men east of the Mississippi. Norton became a personal friend of Turtle-at-Home as well as John Walker, Jr., and The Glass, all of whom were involved in business and commerce. At the time of Norton's visit, Turtle-at-Home owned a ferry with a landing on the Federal Road between Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the List of muni ...

and Athens, Georgia

Athens, officially Athens–Clarke County, is a consolidated city-county and college town in the U.S. state of Georgia. Athens lies about northeast of downtown Atlanta, and is a satellite city of the capital. The University of Georgia, the sta ...

, where he lived at Nickajack. This community had expanded down the Tennessee as well as across it to the north, eclipsing Running Water.

When Georgia and the US government increased pressure for the Cherokee Nation to cede its lands and remove to the west of the Mississippi River, such leaders of the Lower Towns as Tahlonteeskee, Degadoga, John Jolly

John Jolly (Cherokee: ''Ahuludegi''; also known as ''Oolooteka''), was a leader of the Cherokee in Tennessee, the Arkansas Territory, and the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. After 1818, he was the Principal Chief and after reorganization of the t ...

, Richard Fields, John Brown, Bob McLemore, John Rogers, Young Dragging Canoe, George Guess (''Tsiskwaya'', or Sequoyah

Sequoyah (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, ''Ssiquoya'', or ᏎᏉᏯ, ''Se-quo-ya''; 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American polymath of the Ch ...

) and Tatsi (aka Captain Dutch) were forerunners. Believing that removal was inevitable in the face of settlers' greed, they wanted to try to get the best lands and settlements possible. They moved with followers to Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas. Arkansas Post was the first territo ...

, establishing what later became known as the Cherokee Nation West. They next moved to Indian Territory following an 1828 treaty between their leaders and the US government. They were called the "Old Settlers" in Indian Territory and lived there nearly a decade before the remainder of the Cherokee were forced to join them.

Likewise, the remaining leaders of the Lower Towns proved to be the strongest advocates of voluntary westward emigration, in which they were most bitterly opposed by those former warriors and their sons who led the Upper Towns. Ultimately such leaders as Major Ridge (as The Ridge had been known since his military service during the Creek and First Seminole Wars), his son John Ridge

John Ridge, born ''Skah-tle-loh-skee'' (ᏍᎦᏞᎶᏍᎩ, Yellow Bird) ( – 22 June 1839), was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He went to Cornwall, Connecticut, to study at the Foreign Mis ...

, his nephews Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot ( ; May 2, 1740 – October 24, 1821) was a lawyer and statesman from Elizabeth, New Jersey who was a delegate to the Continental Congress (more accurately referred to as the Congress of the Confederation) and served as President ...

and Stand Watie

Brigadier-General Stand Watie ( chr, ᏕᎦᏔᎦ, translit=Degataga, lit=Stand firm; December 12, 1806September 9, 1871), also known as Standhope Uwatie, Tawkertawker, and Isaac S. Watie, was a Cherokee politician who served as the second princ ...

, came to believe that they needed to try to negotiate the best deal with the federal government, as they believed that removal would happen. Other emigration advocates were John Walker, Jr., David Vann, and Andrew Ross (brother of then Principal Chief John Ross). They agreed to the Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established terms ...

in 1835, which resulted in the Cherokee removal

Cherokee removal, part of the Trail of Tears, refers to the forced relocation between 1836 and 1839 of an estimated 16,000 members of the Cherokee Nation and 1,000–2,000 of their slaves; from their lands in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carol ...

in 1838–1839.

Later events

Tecumseh's return

In November 1811,Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

chief Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

returned to the South hoping to gain the support of the southern tribes for his crusade to drive back the Americans and revive the old ways. He was accompanied by representatives from the Shawnee, Muscogee, Kickapoo, and Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

peoples. Tecumseh's exhortations in the towns of the Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

, Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, and Lower Muscogee found no traction. He did attract some support from younger warriors of the Upper Muscogee.

The Cherokee delegation under The Ridge who visited Tecumseh's council at Tuckabatchee

Tukabatchee or Tuckabutche ( Creek: ''Tokepahce'' ) is one of the four mother towns of the Muscogee Creek confederacy.Isham, Theodore and Blue Clark"Creek (Mvskoke)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.'' ...

strongly opposed his plans; Tecumseh cancelled his visit to the Cherokee Nation, as The Ridge threatened him with death if he went there. But, during his recruiting tour, Tecumseh was accompanied by an enthusiastic escort of 47 Cherokee and 19 Choctaw, who presumably went north with him when he returned to the "Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

."

War with the Creek

Tecumseh's mission sparked a religious revival, referred to by anthropologistJames Mooney

James Mooney (February 10, 1861 – December 22, 1921) was an American ethnographer who lived for several years among the Cherokee. Known as "The Indian Man", he conducted major studies of Southeastern Indians, as well as of tribes on the Gr ...

as the "Cherokee Ghost Dance

The Ghost Dance ( Caddo: Nanissáanah, also called the Ghost Dance of 1890) was a ceremony incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka (renamed Jack Wilso ...

" movement. It was led by the prophet Tsali of Coosawatee, a former Chickamauga warrior. He later moved to the western North Carolina mountains, where he was executed by U.S. forces in 1838 for violently resisting Removal.

Tsali met with the national council at Ustanali, arguing for war against the Americans. He moved some leaders, until The Ridge spoke even more eloquently in rebuttal, calling instead for support of the Americans in the coming war with the British and Tecumseh's alliance. During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, William McIntosh

William McIntosh (1775 – April 30, 1825),Hoxie, Frederick (1996)pp. 367-369/ref> was also commonly known as ''Tustunnuggee Hutke'' (White Warrior), was one of the most prominent chiefs of the Creek Nation between the turn of the nineteenth cen ...

of the Lower Muscogee sought Cherokee help in the Creek War, to suppress the " Red Sticks" (Upper Muscogee). More than 500 Cherokee warriors served under Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

in this effort, going against their former allies.

A few years later, Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge (and sometimes Pathkiller II) (c. 1771 – 22 June 1839) (also known as ''Nunnehidihi'', and later ''Ganundalegi'') was a Cherokee leader, a member of the tribal council, and a lawmaker. As a warrior, he fought in the ...

led a troop of Cherokee cavalry who were attached to the 1,400-strong contingent of Lower Muscogee warriors under McIntosh in the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

in Florida. They were allied with and accompanied a force of U.S. regular Army, Georgia militia, and Tennessee volunteers into Florida for action against the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

s, refugee Red Sticks, and escaped slaves fighting against the United States.

Warriors from the Cherokee Nation East traveled to the lands of the Old Settlers (or Cherokee Nation West) in Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas. Arkansas Post was the first territo ...

to assist them during the Cherokee-Osage War of 1817–1823, in which they fought against the Osage. Following the Seminole War, Cherokee warriors, with only one exception, did not take to the warpath in the Southeast again until the time of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, when William Holland Thomas

William Holland Thomas (February 5, 1805 – May 10, 1893) was an American merchant and soldier.

He was the son of Temperance Thomas (née Colvard) and Richard Thomas, who died before he was born. He was raised by his mother on Raccoon Cr ...

raised the Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders in North Carolina to fight for the Confederacy.

In 1830 the State of Georgia seized land in its south that had belonged to the Cherokee since the end of the Creek War, land separated from the rest of the Cherokee Nation by a large section of Georgia territory, and began to parcel it out to settlers. Major Ridge led a party of 30 south, where they drove the settlers out of their homes on what the Cherokee considered their land, and burned all buildings to the ground, but harmed no one.McLoughlin, William G., ''Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic'', pp. 209–215.(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

References

Further reading

''The Bloody Ground: The Chickamauga Wars and Trans–Appalachian Expansion, 1776-1794''

Kane, Sean Patrick; retrieved July 2021; PDF format/download.

External links

* http://www.cherokee.org {{DEFAULTSORT:Cherokee, Chickamauga 18th century Cherokee history 19th century Cherokee history Native American history of North Carolina Native American history of Tennessee State of Franklin Ethnic groups in Appalachia Cherokee Nation (1794–1907)