Cherchel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cherchell (

Cherchell (

In 533, the Vandal Kingdom was conquered by

In 533, the Vandal Kingdom was conquered by

In turn, many ancient statues and buildings were either restored and left in Cherchell, or taken to museums in

In turn, many ancient statues and buildings were either restored and left in Cherchell, or taken to museums in

File:Théâtre Cherchell.jpg, Roman theater

File:Aqueduc de Cherchell, Side view.jpg, Section of Caesarea's Roman aqueduct

File:Archeology Moulin.jpg, Photography of ancient Roman inscriptions from Cherchell, 1856

File:Félix-Jacques Moulin 064.jpg, Photography of Roman remains from Caesarea, 1856

File:Les 3 Grâces.JPG, Mosaic of the Three Graces from Caesarea

File:Juba II.jpg, Portrait of Juba II, found in Caesarea

File:Travail de la vigne Cherchell.jpg, Mosaic of vineyard workers

File:Cherchell museum - car pulled by leopards.jpg, Mosaic of the tigers

GigaCatholic with titular incumbent biography links

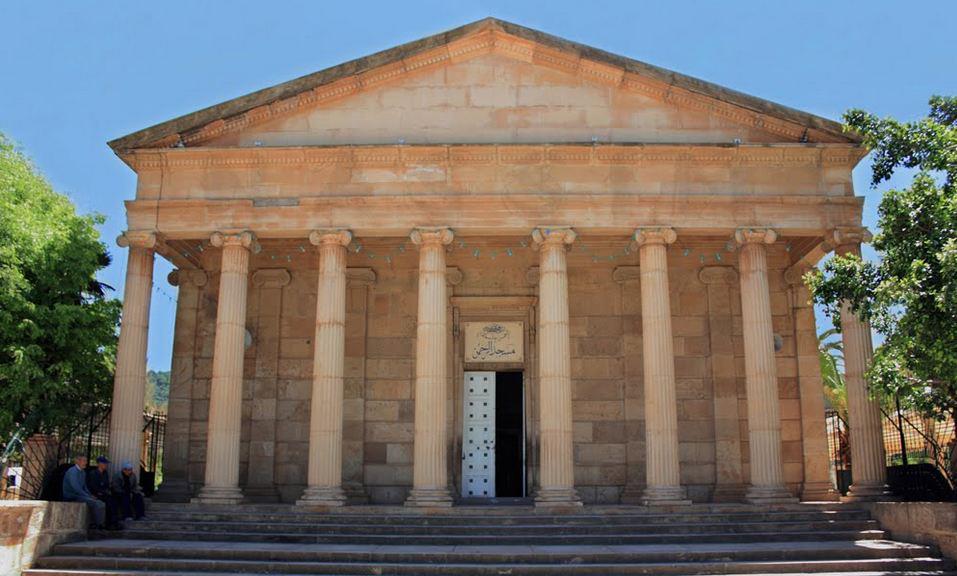

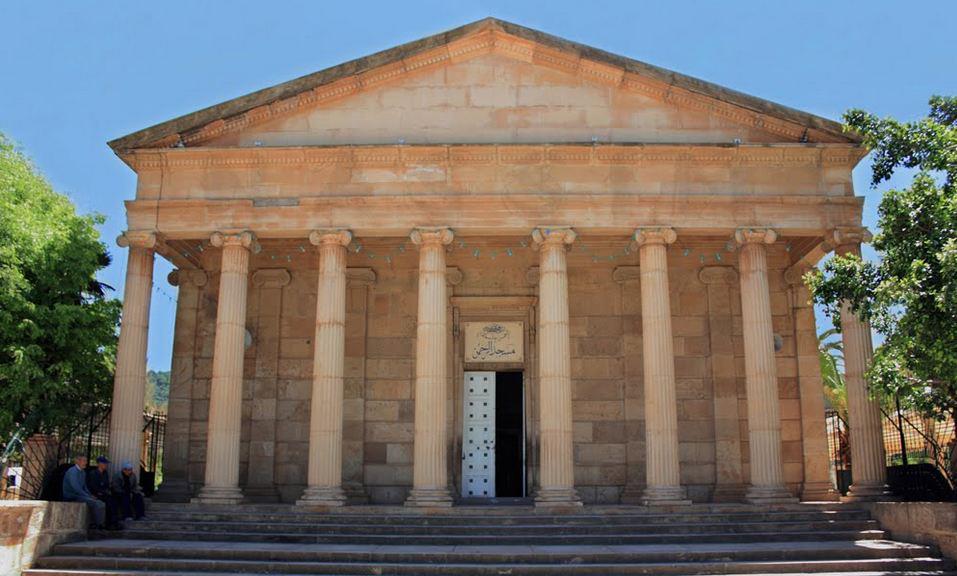

*Various ancient ruins of Cherchell:

A Roman ruin

{{Lighthouse identifiers , qid2=Q22683738 Communes of Tipaza Province Archaeological sites in Algeria Catholic titular sees in Africa Former Roman Catholic dioceses in Africa Roman towns and cities in Mauretania Caesariensis Ancient Berber cities Phoenician colonies in Algeria Populated places established in the 4th century BC 4th-century BC establishments Lighthouses in Algeria Tipaza Province

Cherchell (

Cherchell (Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

: شرشال) is a town on Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

's Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

coast, west of Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

. It is the seat of Cherchell District

Cherchell District is a district of Tipaza Province, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordina ...

in Tipaza Province

Tipaza or Tipasa ( ar, ولاية تيبازة, ''Tibaza'', older ''Tefessedt'') is a province (''wilaya'') on the coast of Algeria, Its capital is Tipaza, 50 km west of the capital of Algeria.

History

The province was created from Blida Pr ...

. Under the names Iol and Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesare ...

, it was formerly a Roman colony

A Roman (plural ) was originally a Roman outpost established in conquered territory to secure it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It is also the origin of the modern term ''colony''.

Characteri ...

and the capital of the kingdoms of Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

and Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It stretched from central present-day Algeria westwards to the Atlantic, covering northern present-day Morocco, and southward to the Atlas Mountains. Its native inhabitants, ...

.

Names

The town was originally known by the Phoenician andPunic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

name , meaning "island of sand". The Punic name was hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in th ...

as ''Iṑl'' ( grc-gre, Ἰὼλ) and Latinized as Iol.

Cherchel and Cherchell are French transcriptions of the Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

name Shershel ( ar, شرشال), derived from the town's old Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

name Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesare ...

( grc-gre, ἡ Καισάρεια, ''hē Kaisáreia''), which was given to it in 25BC by to honor his benefactor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

,. who had legally borne the name "Gaius Julius Caesar" after his posthumous adoption by Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

in 44BC. It was later distinguished from the many other Roman towns named Caesarea by calling it , ("Mauretania's Caesarea"), (, ''Iṑl Kaisáreia''), or . After its notional refounding as a Roman colony

A Roman (plural ) was originally a Roman outpost established in conquered territory to secure it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It is also the origin of the modern term ''colony''.

Characteri ...

, it was formally named after its imperial patron Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

..

History

Antiquity

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient thalassocracy, thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-st ...

established their first major wave of colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

on the coasts between their homeland and the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

in the 8th centuryBC, but Iol was probably established around 600BC. and the oldest remains so far discovered at Cherchell date from the 5th centuryBC. By that time, Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

had already taken control of the Phoenicians in the western Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the eas ...

. Punic Iol was one of the more important trading posts in what is now Algeria. In the 3rd centuryBC, it was fortified and began issuing Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

's first coins

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to ...

in bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

, bearing Punic text, Carthaginian gods, and images of local produce, particularly fish.

After the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146BC fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage. Three conflicts between these states took place on both land and sea across the western Mediterranean region and i ...

, Carthage's holdings in northwest Africa were mostly given to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

's local allies. Iol was given to Micipsa

Micipsa (Numidian: MKWSN; , ; died BC) was the eldest legitimate son of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in North Africa. Micipsa became the King of Numidia in 148 BC.

Early life

In 151 BC, Masinissa sent Micipsa and his brother ...

, the king of Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

, who first established it as a royal court. It became an important city for the kingdom and was the primary capital for and II. The town minted its own coins and received new defensive works in the 1st centuryBC. Its Punic culture continued, but worship of Baal Hammon

Baal Hammon, properly Baʿal Ḥammon or Baʿal Ḥamon ( Phoenician: ; Punic: ), meaning “Lord Hammon”, was the chief god of Carthage. He was a weather god considered responsible for the fertility of vegetation and esteemed as King of the ...

was notionally substituted with worship of his Roman equivalent Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

.

Iol was annexed directly to Rome in 33BC. Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

established as king of Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It stretched from central present-day Algeria westwards to the Atlantic, covering northern present-day Morocco, and southward to the Atlas Mountains. Its native inhabitants, ...

in 25BC, giving him the city as his capital, which Juba then renamed in his honor. Juba and his wife Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

(the daughter of Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

and Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

) rebuilt the city on a lavish scale, combining Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

and Hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in th ...

Egyptian styles. The roads were relaid on a grid and amenities included a theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actor, actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The p ...

, an art gallery, and a lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mar ...

modeled after the Pharos

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria (; Ancient Greek: ὁ Φάρος τῆς Ἀλεξανδρείας, contemporary Koine ), was a lighthouse built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, during the re ...

in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

. He probably began the Roman wall that ran for about around a space of about ; about 150 of that total was used for the settlement in antiquity. The royal couple were buried in the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania

The Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania is a funerary monument located on the road between Cherchell and Algiers, in Tipaza Province, Algeria. The mausoleum is the tomb where the Numidian Berber King Juba II (son of Juba I of Numidia) and the Queen Cleop ...

. The seaport capital and its kingdom flourished during this period, with most of the population being of Greek and Phoenician origin with a minority of Berbers.

Their son Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

was assassinated by Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

during a trip to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in AD40. Rome proclaimed the annexation of Mauretania, which was resisted by Ptolemy's former slave Aedemon

Aedemon () was a freedman of Berber origins from Mauretania who lived in the 1st century AD. Aedemon was a loyal former household slave to the client King Ptolemy of Mauretania, who was the son of King Juba II and the Ptolemaic Princess Cleopat ...

and by Berber leaders such as Sabalus Sabalus was a of Berber warrior from Mauretania, North Africa who lived in the 1st century. Sabalus was one of the tribal chiefs in the Roman Client Kingdom of Mauretania. Little is known of Sabalus’ origins.

In late 40, king Ptolemy of Mauret ...

. Caligula himself was murdered before Rome's response could be made, but his successor Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

sent legions under Gn. Hosidius Geta and G. Suetonius Paulinus to complete the conquest. By 44, most resistance had been ended and the former kingdom was divided into two Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

s, one governed from Tingis (present-day Tangiers

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

) and another governed from Caesarea. Mauretania Caesariensis

Mauretania Caesariensis (Latin for "Caesarean Mauretania") was a Roman province located in what is now Algeria in the Maghreb. The full name refers to its capital Caesarea Mauretaniae (modern Cherchell).

The province had been part of the Kingd ...

extended along what is now the Algerian coast and included most of the hinterland as far as the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. It separates the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range. It stretches around through Moroc ...

.

Roman colonies

Colonies in antiquity were post-Iron Age city-states founded from a mother-city (its "metropolis"), not from a territory-at-large. Bonds between a colony and its metropolis remained often close, and took specific forms during the period of classic ...

of veteran soldiers were established in the new provinces to maintain order. Caesarea itself was made a colony, with its residents gaining Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

. It prospered as a provincial capital during the 1st and 2nd centuries, reaching a population of over 20,000 and possibly as many as 30,000. It was defended by auxiliary units

The Auxiliary Units or GHQ Auxiliary Units were specially-trained, highly-secret quasi military units created by the British government during the Second World War with the aim of using irregular warfare in response to a possible invasion of the U ...

and was the harbor of Rome's Mauretanian Fleet, which was established as a permanent force after Berber raids in the early 170s. The city featured a hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

, amphitheater

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

, numerous temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

, and civic buildings like a basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its name ...

. It was surrounded by suburban villas whose agricultural mosaics are now celebrated. It had its own school of philosophy, academy, and library. It received a new forum

Forum or The Forum (plural forums or fora) may refer to:

Common uses

* Forum (legal), designated space for public expression in the United States

*Forum (Roman), open public space within a Roman city

**Roman Forum, most famous example

*Internet ...

and further patronage from the African emperor Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

and his dynasty, possibly reaching as many as 100,000 inhabitants. Its native son Macrinus

Marcus Opellius Macrinus (; – June 218) was Roman emperor from April 217 to June 218, reigning jointly with his young son Diadumenianus. As a member of the equestrian class, he became the first emperor who did not hail from the senatori ...

and his son Diadumenian

Diadumenian (; la, Marcus Opellius Antoninus Diadumenianus; 14September 208 – June 218) was the son of the Roman Emperor Macrinus, and served as his co-ruler for a brief time in 218. His mother was Nonia Celsa, whose name may be fictitiou ...

became the first Berber and lower-class emperors, reigning in 217 and 218. ( Their predecessor's wastefulness and wars required unpopular financial adjustments that led to their overthrow in favor of Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 11/12 March 222), better known by his nickname "Elagabalus" (, ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short reign was conspicuous for s ...

.) Juba's theater was converted into an amphitheater sometime after the year 300.

The city was sacked by a Berber revolt in 371 and 372. It largely recovered, but was ravaged again by the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

after they were invited into Roman North Africa

Africa Proconsularis was a Roman province on the northern African coast that was established in 146 BC following the defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisia, the northeast of Algeria, ...

by Count Boniface

Bonifatius (or Bonifacius; also known as Count Boniface; died 432) was a Roman general and governor of the diocese of Africa. He campaigned against the Visigoths in Gaul and the Vandals in North Africa. An ally of Galla Placidia, mother and ad ...

in 429. Parts of the town received new fortifications. After the Vandal Kingdom conquered Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

in 439, they also acquired a large part of Rome's Mediterranean fleet which they used to carry out raids all over the sea. Caesarea's port was sometimes used as a base for these raiders, and the city prospered from their plunder. Its schools produced the famous grammarian Priscian

Priscianus Caesariensis (), commonly known as Priscian ( or ), was a Latin grammarian and the author of the ''Institutes of Grammar'', which was the standard textbook for the study of Latin during the Middle Ages. It also provided the raw materia ...

, who emigrated to the Byzantine east.

Middle Ages

In 533, the Vandal Kingdom was conquered by

In 533, the Vandal Kingdom was conquered by Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

forces under Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

's general Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

. Caesarea was among the areas to return to imperial rule. It was the seat of Mauretania's duke ( la, dux),. but it went into decline and its city center was given over to ramshackle housing for the poor. The first duke was named John; that he was given an infantry unit rather than cavalry implies that he was meant to hold the port without much concern about controlling its surrounding hinterland.

The town remained under Byzantine control until its Muslim conquest in the late 7th century. Successive waves of Umayyad attacks into Byzantine North African territory over 15 years wore down the smaller and less motivated imperial forces, until finally Umayyad troops laid siege to the city of Caesarea and, although the defenders were resupplied by Byzantine fleets, finally overwhelmed it. Much of the Byzantine nobility and officials fled to other parts of the Empire, while most of the remaining Roman and semi-Roman Berber population accepted Islamic rule which granted them protected status.

Some remained Christians. For two generations what remained of the Roman population and Romanized Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

launched several revolts often in conjunction with reinforcements from the Empire. As a result, by the ninth century down much of the city's defences were damaged beyond repair, and resulting in its political loss of importance, leaving the former city little more than a small village

A village is a clustered human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet but smaller than a town (although the word is often used to describe both hamlets and smaller towns), with a population typically ranging from a few hundred to ...

.

For the following few centuries, the city remained a power center of Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

s and Berbers with a small but significant population of Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

who were fully assimilated by the beginning of the Early Modern period. Similarly, by the 10th century the city's name had transformed in the local dialect from a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

to a Berber and ultimately into the Arabised form ''Sharshal'' (in French orthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Most transnational languages in the modern period have a writing system, and mos ...

, Cherchell).

The Norman Kingdom of Africa raided Berreshk, near Cherchell, in 1144.

Modernity

Eventually, Ottoman Turks managed to successfully reconquer the city from Spanish occupation in the 16th century, using the city primarily as a fortified port. In 1520,Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa ( ar, خير الدين بربروس, Khayr al-Din Barbarus, original name: Khiḍr; tr, Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa), also known as Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1478 – 4 July 1546), was an Ot ...

captured the town and annexed the Algerian Pashalic

Eyalets (Ottoman Turkish: ایالت, , English: State), also known as beylerbeyliks or pashaliks, were a primary administrative division of the Ottoman Empire.

From 1453 to the beginning of the nineteenth century the Ottoman local government ...

. His elder brother Oruç Reis

Oruç Reis ( ota, عروج ريس; es, Aruj; 1474 – 1518) was an Ottoman corsair who became Sultan of Algiers. The elder brother of the famous Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa, he was born on the Ottoman island of Midilli (Lesbos i ...

built a fort over the town. Under Turkish occupation, the city's importance as a port and fort led to it being inhabited by Moslems of many nationalities, some engaging in privateering and piracy on the Mediterranean.

In reply, European navies and especially the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

and the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

(self-proclaimed descendants of the Crusaders) laid siege to the city and occasionally captured it for limited periods of time. For a century in the 1600s and for a brief period in the 1700s the city either was under Spanish or Hospitallar control. During this period a number of palaces were built, but the overwhelming edifice of Hayreddin Barbarossa's citadel, was considered too militarily valuable to destroy and uncover the previous ancient buildings of old Caesarea.

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

and Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

s of the early 19th century, the French under both British, American, and other European powers were encouraged to attack and destroy the Barbary Pirates. From 1836 to 1840 various allied navies, but mostly French hunted down the Barbary pirates and conquered the Barbary ports while threatening the Ottoman Empire with war if it intervened. In 1840, the French after a significant siege captured and occupied the town. The French lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

the Barbary Pirates including the local pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

for Crimes against the laws of nations

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

.

In turn, many ancient statues and buildings were either restored and left in Cherchell, or taken to museums in

In turn, many ancient statues and buildings were either restored and left in Cherchell, or taken to museums in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

or Paris, France for further study. However, not all building projects were successful in uncovering and restoring the ancient town. The Roman amphitheatre was considered mostly unsalvageable and unnecessary to rebuilt. Its dress stones were used to the build a new French fort and barracks. Materials from the Hippodrome were used to build a new church. The steps of the Hippodrome were partly destroyed by Cardinal Charles Lavigerie

Charles Martial Allemand Lavigerie (31 October 1825 – 26 November 1892) was a French cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tunis, archbishop of Carthage and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Algiers, Algiers and primate of A ...

in a search for the tomb of Saint Marciana.

French occupation also brought new European settlement, to join the city's long-established communities of semi-Arabized Christians of local origin and old European merchant families, in addition to Berbers and Arab Muslims. Under French rule, European and Christians became a majority of the population again until World War II.

In the immediate years before World War II, losses to the French national population from World War I, and a declining birthrate in general among Europeans kept further colonial settlement to a trickle. Arab and Berber populations started seeing an increase in growth. French-Algerian colonial officials and landowners encouraged larger numbers of surrounding Berber tribesmen to move into the surrounding region to work the farms and groves cheaply. In turn, more and more Berbers and Arabs moved into the city seeking employment. By 1930 the combined Berbo-Arab Algerian population represented nearly 40% of the city's population.

The changing demographics within the city were disguised by the large numbers of French military personnel based there and the numbers of European tourists visiting what had become known as the Algerian Riviera. Additionally, during World War II, Cherchell, with its libraries, cafes, restaurants, and hotels served as a base for the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

and Allied War effort, hosting a summit conference

A summit meeting (or just summit) is an international meeting of heads of state or government, usually with considerable media exposure, tight security, and a prearranged agenda. Notable summit meetings include those of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wi ...

between the US and UK in October 1942.

The end of the war with its departure of Allied forces and a reduction of French naval personnel due to rebasing saw an actual decline in Europeans living in the city. Additionally, the general austerity of the post-war years dried up the tourism industry and caused financial stagnation and losses to the local Franco-Algerian community. In 1952, a census recorded that the Frenco-Algerian population had declined to 50% of the population.

For the remaining 1950's Cherchell was only slightly caught up by the Algerian War of Independence

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

. With its large proportion of Europeans, French control and influence was strong enough to discourage all but the most daring attacks by anti-French insurgents. By 1966, after independence from the French, Cherchell had lost nearly half of its population and all of its Franco-Algerian population.

Independent Algeria

Cherchell has continued to grow post-independence, recovering to peak colonial-era population by the 1980s. Cherchell currently has industries in marble, plaster quarries and iron mines. The town trades in oils, tobacco and earthenware. Additionally, the ancient cistern first developed by Juba and Cleopatra Selene II was restored and expanded under recent French rule and still supplies water to the town. Although the Algerian Riviera ended with the war, Cherchell is still a popular tourist places in Algeria. Cherchell has various splendid temples and monuments from thePunic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

, Numidian and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

periods, and the works of art found there, including statues of Neptune and Venus, are now in the Museum of Antiquities

The Museum of Antiquities was an archaeological museum at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, England. It opened in 1960 and in 2009 its collections were merged into the Great North Museum: Hancock.

History

The museum was originally op ...

in Algiers. The former Roman port is no longer in commercial use and has been partly filled by alluvial deposits and has been affected by earthquakes. The former local mosque of the Hundred Columns contains 89 columns of diorite

Diorite ( ) is an intrusive igneous rock formed by the slow cooling underground of magma (molten rock) that has a moderate content of silica and a relatively low content of alkali metals. It is intermediate in composition between low-silic ...

. This remarkable building now serves as a hospital. The local museum displays some of the finest ancient Greek and Roman antiquities found in Africa. Cherchell is the birthplace of writer and movie director Assia Djebar

Fatima-Zohra Imalayen (30 June 1936 – 6 February 2015), known by her pen name Assia Djebar ( ar, آسيا جبار), was an Algerian novelist, translator and filmmaker. Most of her works deal with obstacles faced by women, and she is noted fo ...

.

Historical population

Remains

Earthquakes, wars and plunder have ravaged many of the ancient remains. Some remains can be seen in the local Archeological Museum of Chercell-Caesarea.Religion

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

arrived in Caesarea early enough to produce martyrs

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

during the Diocletianic Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights ...

. For vandalizing an idol

Idol or Idols may refer to:

Religion and philosophy

* Cult image, a neutral term for a man-made object that is worshipped or venerated for the deity, spirit or demon that it embodies or represents

* Murti, a point of focus for devotion or medit ...

of Diana, StMarciana was supposedly tortured and killed in Caesarea's arena, gored by a bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions,

includin ...

and mauled by a leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant species in the genus '' Panthera'', a member of the cat family, Felidae. It occurs in a wide range in sub-Saharan Africa, in some parts of Western and Central Asia, Southern Russia, a ...

for the amusement of the crowd. StTheodota and her sons were also supposedly martyred in the city.

Caesarea was a bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

from about 314 to 484, although not all of its bishops are known. Fortunatus took part in the 314 Council of Arles, which condemned Donatism

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and t ...

. Clemens was mentioned in one of Symmachus's letters and would have served in the 370s. During the 411 synod at Carthage, Caesarea was represented by the Donatist Emeritus and the orthodox Deuterius. StAugustine accosted Emeritus at Caesarea in the autumn of 418 and secured his exile. Apocorius was an orthodox bishop whom Huneric

Huneric, Hunneric or Honeric (died December 23, 484) was King of the (North African) Vandal Kingdom (477–484) and the oldest son of Gaiseric. He abandoned the imperial politics of his father and concentrated mainly on internal affairs. He was m ...

summoned to Carthage in 484 and then exiled. An early 8th-century ''Notitia Episcopatuum The ''Notitiae Episcopatuum'' (singular: ''Notitia Episcopatuum'') are official documents that furnish Eastern countries the list and hierarchical rank of the metropolitan and suffragan bishoprics of a church.

In the Roman Church (the -mostly Lati ...

'' still included this see.

Caesarea was revived by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

as a titular see

A titular see in various churches is an episcopal see of a former diocese that no longer functions, sometimes called a "dead diocese". The ordinary or hierarch of such a see may be styled a "titular metropolitan" (highest rank), "titular archbish ...

in the 19th century. It was distinguished as "Caesarea in Mauretania" in 1933.''Annuario Pontificio 2013'' (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ), p. 867 Its bishops have included:

* Titular Bishop Biagio Pisani (1897.04.23 – 1901.06.07)

* Titular Bishop Pietro Maffi (1902.06.09 – 1903.06.22)

* Titular Bishop Thomas Francis Brennan (1905.10.07 – 1916.03.20)

* Titular Archbishop Pierre-Célestin Cézerac (1918.01.02 – 1918.03.18)

* Titular Archbishop Cardinal Wilhelmus Marinus van Rossum, CSSR (1918.04.25 – 1918.05.20)

* Titular Archbishop Benedetto Aloisi Masella

Benedetto Aloisi Masella (29 June 1879 – 30 September 1970) was an Italian cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church who served as prefect of the Discipline of the Sacraments from 1954 to 1968, and as chamberlain of the Roman Church (or camer ...

(1919.12.15 – 1946.02.18)

* Titular Bishop Luigi Cammarata (1946.12.04 – 1950.02.25)

* Titular Bishop Francesco Pennisi (1950.07.11 – 1955.10.01)

* Titular Bishop André-Jacques Fougerat (1956.07.16 – 1957.01.05)

* Titular Bishop Carmelo Canzonieri (1957.03.11 – 1963.07.30)

* Titular Bishop Archbishop Enea Selis (1964.01.18 – 1971.09.02)

* Titular Bishop Giuseppe Moizo (1972.01.22 – 1976.07.01)

* Titular Archbishop Sergio Sebastiani

Sergio Sebastiani (born 11 April 1931) is an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church who was head of the Prefecture for the Economic Affairs of the Holy See from 1997 to 2008. He was made a cardinal in 2001. From 1960 to 1994 he worked in the d ...

(1976.09.27 – 2001.02.21)

* Titular Bishop Gerard Johannes Nicolaas de Korte (2001.04.11 – 2008.06.18)

* Titular Bishop Stanislaus Tobias Magombo (2009.04.29 – 2010.07.06)

* Titular Archbishop Walter Brandmüller

Walter Brandmüller (born 5 January 1929) is a German prelate of the Catholic Church, a cardinal since 2010. He was president of the Pontifical Committee for Historical Sciences from 1998 to 2009.

Early life

Brandmüller was born in 1929 in An ...

(2010.11.04 – 2010.11.20)

* Titular Archbishop Marek Solczyński (2011.11.26 – present)

Gallery

See also

*List of lighthouses in Algeria

This is a list of lighthouses in Algeria. The list includes those maritime lighthouses that are named landfall lights, or have a range of at least fifteen nautical miles. They are located along the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coastline, and on ...

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * .External links

GigaCatholic with titular incumbent biography links

*Various ancient ruins of Cherchell:

A Roman ruin

{{Lighthouse identifiers , qid2=Q22683738 Communes of Tipaza Province Archaeological sites in Algeria Catholic titular sees in Africa Former Roman Catholic dioceses in Africa Roman towns and cities in Mauretania Caesariensis Ancient Berber cities Phoenician colonies in Algeria Populated places established in the 4th century BC 4th-century BC establishments Lighthouses in Algeria Tipaza Province