Chelsea Bridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chelsea Bridge is a bridge over the

The Red House Inn was an isolated

The Red House Inn was an isolated

Page's design was typical of suspension bridges of the period, and consisted of a

Page's design was typical of suspension bridges of the period, and consisted of a  Victoria Bridge was long with a central span of , and the roadway was wide with a footpath on either side, making a total width of . Large lamps were set at the tops of the four towers, which were only to be lit when

Victoria Bridge was long with a central span of , and the roadway was wide with a footpath on either side, making a total width of . Large lamps were set at the tops of the four towers, which were only to be lit when

Although reasonably well used, it was unpopular with the public, who objected to being obliged to pay tolls to use it. On 4 July 1857, almost a year before the bridge's opening, a demonstration against the tolls attracted 6,000 residents. Concerns were raised in Parliament that poorer industrial workers in Chelsea, which had no large parks of its own, would be unable to afford to use the new park in Battersea. Bowing to public pressure, shortly after the bridge opened Parliament declared it free to use for pedestrians on Sundays, and in 1875 it was also made toll-free on public holidays. Additionally, because the main lights were only turned on when Queen Victoria was staying in London, it was poorly used at night. Despite this, the new Battersea Park was extremely popular, particularly the sporting facilities; on 9 January 1864 the park staged the world's first official game of

Although reasonably well used, it was unpopular with the public, who objected to being obliged to pay tolls to use it. On 4 July 1857, almost a year before the bridge's opening, a demonstration against the tolls attracted 6,000 residents. Concerns were raised in Parliament that poorer industrial workers in Chelsea, which had no large parks of its own, would be unable to afford to use the new park in Battersea. Bowing to public pressure, shortly after the bridge opened Parliament declared it free to use for pedestrians on Sundays, and in 1875 it was also made toll-free on public holidays. Additionally, because the main lights were only turned on when Queen Victoria was staying in London, it was poorly used at night. Despite this, the new Battersea Park was extremely popular, particularly the sporting facilities; on 9 January 1864 the park staged the world's first official game of

In 1931 the

In 1931 the

In 1934 a temporary footbridge which had previously been used during rebuilding works on

In 1934 a temporary footbridge which had previously been used during rebuilding works on  Because the self-anchored structure relies on the roadway itself to absorb stresses, the suspension cables could not be installed until the roadway was built; however, until the cables were in place the roadway could not be supported. To resolve this problem, Topham had the roadway built in sections, supported on very tall

Because the self-anchored structure relies on the roadway itself to absorb stresses, the suspension cables could not be installed until the roadway was built; however, until the cables were in place the roadway could not be supported. To resolve this problem, Topham had the roadway built in sections, supported on very tall  The new bridge was completed five months ahead of schedule and within the £365,000 budget. It was opened on 6 May 1937 by the

The new bridge was completed five months ahead of schedule and within the £365,000 budget. It was opened on 6 May 1937 by the

In the 1970s Chelsea Bridge was painted bright red and white, prompting a number of complaints from

In the 1970s Chelsea Bridge was painted bright red and white, prompting a number of complaints from

To link the new developments around Battersea Power Station to Battersea Park, in 2004 a curved footbridge was built beneath the southern end of Chelsea Bridge. The footbridge was built offsite in four sections, transported by road to the King George V Dock where it was assembled, and the completed structure floated down the river and hoisted into position. It is planned that once the riverfront in the area has been opened to the public, following the completion of the rebuilding of Battersea Power Station into a commercial development, the new bridge will form part of the

To link the new developments around Battersea Power Station to Battersea Park, in 2004 a curved footbridge was built beneath the southern end of Chelsea Bridge. The footbridge was built offsite in four sections, transported by road to the King George V Dock where it was assembled, and the completed structure floated down the river and hoisted into position. It is planned that once the riverfront in the area has been opened to the public, following the completion of the rebuilding of Battersea Power Station into a commercial development, the new bridge will form part of the

River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

in west London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, connecting Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

on the north bank to Battersea

Battersea is a large district in south London, part of the London Borough of Wandsworth, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross and extends along the south bank of the River Thames. It includes the Battersea Park.

History

Batter ...

on the south bank, and split between the City of Westminster

The City of Westminster is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and London boroughs, borough in Inner London. It is the site of the United Kingdom's Houses of Parliament and much of the British government. It occupies a large area of cent ...

, the London Borough of Wandsworth

Wandsworth () is a London boroughs, London borough in southwest London; it forms part of Inner London and has an estimated population of 329,677 inhabitants. Its main named areas are Battersea, Balham, Putney, Tooting and Wandsworth, Wandsworth ...

and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea is an Inner London borough with royal status. It is the smallest borough in London and the second smallest district in England; it is one of the most densely populated administrative regions in the ...

. There have been two Chelsea Bridges, on the site of what was an ancient ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

.

The first Chelsea Bridge was proposed in the 1840s as part of a major development of marshlands on the south bank of the Thames into the new Battersea Park

Battersea Park is a 200-acre (83-hectare) green space at Battersea in the London Borough of Wandsworth in London. It is situated on the south bank of the River Thames opposite Chelsea and was opened in 1858.

The park occupies marshland reclai ...

. It was a suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck (bridge), deck is hung below suspension wire rope, cables on vertical suspenders. The first modern examples of this type of bridge were built in the early 1800s. Simple suspension bridg ...

intended to provide convenient access from the densely populated north bank to the new park. Although built and operated by the government, tolls were charged initially in an effort to recoup the cost of the bridge. Work on the nearby Chelsea Embankment

Chelsea Embankment is part of the Thames Embankment, a road and walkway along the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England.

The western end of Chelsea Embankment, including a stretch of Cheyne Walk, is in the Royal Borough of ...

delayed construction and so the bridge, initially called Victoria Bridge, did not open until 1858. Although well-received architecturally, as a toll bridge it was unpopular with the public, and Parliament felt obliged to make it toll-free on Sundays. The bridge was less of a commercial success than had been anticipated, partly because of competition from the newly built Albert Bridge nearby. It was acquired by the Metropolitan Board of Works

The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was the principal instrument of local government in a wide area of Middlesex, Surrey, and Kent, defined by the Metropolis Management Act 1855, from December 1855 until the establishment of the London County ...

in 1877, and the tolls were abolished in 1879.

The bridge was narrow and structurally unsound, leading the authorities to rename it Chelsea Bridge to avoid the Royal Family's association with a potential collapse. In 1926 it was proposed that the old bridge be rebuilt or replaced, due to the increased volume of users from population growth, and the introduction of the automobile. It was demolished during 1934–1937, and replaced by the current structure, which opened in 1937.

The new bridge was the first self-anchored suspension bridge

A self-anchored suspension bridge is a suspension bridge type in which the main cables attach to the ends of the deck, rather than directly to the ground or via large anchorages. The design is well-suited for construction atop elevated piers, o ...

in Britain, and was built entirely with materials sourced from within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. During the early 1950s it became popular with motorcyclist

Motorcycling is the act of riding a motorcycle. For some people, motorcycling may be the only affordable form of individual motorized transportation, and small- displacement motorcycles are the most common motor vehicle in the most populous c ...

s, who staged regular races across the bridge. One such meeting in 1970 erupted into violence, resulting in the death of one man and the imprisonment of 20 others. Chelsea Bridge is floodlit from below during the hours of darkness, when the towers and cables are illuminated by of light-emitting diode

A light-emitting diode (LED) is a semiconductor device that emits light when current flows through it. Electrons in the semiconductor recombine with electron holes, releasing energy in the form of photons. The color of the light (cor ...

s. In 2008 it achieved Grade II listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

status. In 2004 a footbridge was opened beneath the southern span, carrying the Thames Path

The Thames Path is a National Trail following the River Thames from its source near Kemble, Gloucestershire, Kemble in Gloucestershire to the Woolwich foot tunnel, south east London. It is about long. A path was first proposed in 1948 but it onl ...

under the bridge.

Background

The Red House Inn was an isolated

The Red House Inn was an isolated inn

Inns are generally establishments or buildings where travelers can seek lodging, and usually, food and drink. Inns are typically located in the country or along a highway; before the advent of motorized transportation they also provided accommo ...

on the south bank of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

in the marshlands by Battersea fields, about east of the developed street of the prosperous farming village of Battersea

Battersea is a large district in south London, part of the London Borough of Wandsworth, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross and extends along the south bank of the River Thames. It includes the Battersea Park.

History

Batter ...

. Not on any major road, its isolation and lack of any police presence made it a popular destination for visitors from London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

since the 16th century, who would travel to the Red House by wherry

A wherry is a type of boat that was traditionally used for carrying cargo or passengers on rivers and canals in England, and is particularly associated with the River Thames and the River Cam. They were also used on the Broadland rivers of No ...

, attracted by Sunday dog fighting

Dog fighting is a type of blood sport that turns game and fighting dogs against each other in a physical fight, generally to the death, for the purposes of gambling or entertainment to the spectators. In rural areas, fights are often staged i ...

, bare-knuckle boxing

Bare-knuckle boxing (or simply bare-knuckle) is a combat sport which involves two individuals throwing punches at each other for a predetermined amount of time without any boxing gloves or other form of padding on their hands. It is a regulated ...

bouts and illegal horse racing

Horse racing is an equestrian performance sport, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its basic p ...

. Because of its lawless nature, Battersea Fields was also a popular area for duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

ling, and was the venue for the 1829 duel between the then Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of ...

and the Earl of Winchilsea

Earl of Winchilsea is a title in the Peerage of England held by the Finch-Hatton family. It has been united with the title of Earl of Nottingham under a single holder since 1729. The Finch family is believed to be descended from Henry FitzHerbe ...

.

The town of Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

, on the north bank of the Thames about west of Westminster, was an important industrial centre. Although by the 19th century its role as the centre of the British porcelain industry had been overtaken by the West Midlands

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

, its riverside location and good roads made it an important centre for the manufacture of goods to serve the nearby and rapidly growing London.

The Chelsea Waterworks Company

The Chelsea Waterworks Company was a London waterworks

Water supply is the provision of water by public utilities, commercial organisations, community endeavors or by individuals, usually via a system of pumps and pipes. Public water sup ...

occupied a site on the north bank of the Thames opposite the Red House Inn. Founded in 1723, the company pumped water from the Thames to reservoir

A reservoir (; from French ''réservoir'' ) is an enlarged lake behind a dam. Such a dam may be either artificial, built to store fresh water or it may be a natural formation.

Reservoirs can be created in a number of ways, including contro ...

s around Westminster through a network of hollow elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the flowering plant genus ''Ulmus'' in the plant family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical-montane regions of North ...

trunks. As London spread westwards, the former farmland to the west became increasingly populated, and the Thames became seriously polluted with sewage

Sewage (or domestic sewage, domestic wastewater, municipal wastewater) is a type of wastewater that is produced by a community of people. It is typically transported through a sewer system. Sewage consists of wastewater discharged from residenc ...

and animal carcasses. In 1852 Parliament banned water from being taken from the Thames downstream of Teddington

Teddington is a suburb in south-west London in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. In 2021, Teddington was named as the best place to live in London by ''The Sunday Times''. Historically in Middlesex, Teddington is situated on a long m ...

, forcing the Chelsea Waterworks Company to move upstream to Seething Wells

Seething Wells is a neighbourhood in southwest London on the border between Surbiton in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames in Greater London, and Elmbridge in Surrey. The area was historically a waterworks that supplied London with water ...

.

Since 1771, Battersea and Chelsea had been linked by the modest wooden Battersea Bridge

Battersea Bridge is a five-span arch bridge with cast-iron girders and granite piers crossing the River Thames in London, England. It is situated on a sharp bend in the river, and links Battersea south of the river with Chelsea to the north. Th ...

. As London grew following the advent of the railways, Chelsea began to become congested, and in 1842 the Commission of Woods, Forests, and Land Revenues recommended the building of an embankment

Embankment may refer to:

Geology and geography

* A levee, an artificial bank raised above the immediately surrounding land to redirect or prevent flooding by a river, lake or sea

* Embankment (earthworks), a raised bank to carry a road, railwa ...

at Chelsea to free new land for development, and proposed the building of a new bridge downstream of Battersea Bridge and the replacement of Battersea Bridge with a more modern structure.

Battersea Park

In the early 1840sThomas Cubitt

Thomas Cubitt (25 February 1788 – 20 December 1855) was a British master builder, notable for his employment in developing many of the historic streets and squares of London, especially in Belgravia, Pimlico and Bloomsbury. His great-great-g ...

and James Pennethorne

Sir James Pennethorne (4 June 1801 – 1 September 1871) was a British architect and planner, particularly associated with buildings and parks in central London.

Life

Early years

Pennethorne was born in Worcester, and travelled to London in 1 ...

had proposed a plan to use 150,000 tons of rocks and earth from the excavation of the Royal Victoria Dock to infill the marshy Battersea Fields and create a large public park to serve the growing population of Chelsea. In 1846 the Commissioners of Woods and Forests purchased the Red House Inn and of surrounding land, and work began on the development that would become Battersea Park

Battersea Park is a 200-acre (83-hectare) green space at Battersea in the London Borough of Wandsworth in London. It is situated on the south bank of the River Thames opposite Chelsea and was opened in 1858.

The park occupies marshland reclai ...

. It was expected that with the opening of the park the volume of cross river traffic would increase significantly, putting further strain on the dilapidated Battersea Bridge.

Consequently, in 1846 an Act of Parliament authorised the building of a new toll bridge

A toll bridge is a bridge where a monetary charge (or ''toll'') is required to pass over. Generally the private or public owner, builder and maintainer of the bridge uses the toll to recoup their investment, in much the same way as a toll road. ...

on the site of an ancient ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

exactly downstream of Battersea Bridge. The approach road on the southern side was to run along the side of the new park, while that on the northern side was to run from Sloane Square

Sloane Square is a small hard-landscaped square on the boundaries of the central London districts of Belgravia and Chelsea, located southwest of Charing Cross, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The area forms a boundary betwe ...

, through the former Chelsea Waterworks site, to the new bridge. Although previous toll bridges in the area had been built and operated by private companies, the new bridge was to be built and operated by the government, under the control of the Metropolitan Improvement Commission, despite protests in Parliament from Radicals objecting to the Government profiting from a toll-paying bridge. It was intended that the bridge would be made toll-free once the costs of building it had been recouped.

Victoria Bridge (Old Chelsea Bridge)

Engineer Thomas Page was appointed to build the bridge, and presented the Commission with several potential designs, including a seven-span stone bridge, a five-span cast iron arch bridge, and asuspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck (bridge), deck is hung below suspension wire rope, cables on vertical suspenders. The first modern examples of this type of bridge were built in the early 1800s. Simple suspension bridg ...

. The Commission selected the suspension bridge design, and work began in 1851 on the new bridge, to be called the Victoria Bridge.

Design and construction

Page's design was typical of suspension bridges of the period, and consisted of a

Page's design was typical of suspension bridges of the period, and consisted of a wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

deck and four cast iron towers supporting chains, which in turn supported the weight of the deck. The towers rested on a pair of timber and cast iron piers Piers may refer to:

* Pier, a raised structure over a body of water

* Pier (architecture), an architectural support

* Piers (name), a given name and surname (including lists of people with the name)

* Piers baronets, two titles, in the baronetages ...

. The towers passed through the deck, meaning that between the towers the road was narrower than on the rest of the bridge. Although work had begun in 1851 delays in the closure of the Chelsea Waterworks, which only completed its relocation to Seething Wells in 1856, caused lengthy delays to the project, and the Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

-made ironwork was only transported to the site in 1856.

Victoria Bridge was long with a central span of , and the roadway was wide with a footpath on either side, making a total width of . Large lamps were set at the tops of the four towers, which were only to be lit when

Victoria Bridge was long with a central span of , and the roadway was wide with a footpath on either side, making a total width of . Large lamps were set at the tops of the four towers, which were only to be lit when Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

was spending the night in London. The central span was inscribed with the date of construction and the words "Gloria Deo in Excelsis" ("Glory to God in the Highest"). It took seven years to build, at a total cost of £90,000 (about £ in ). The controversial tolls were collected from octagonal stone tollhouses at each end of the bridge.

As with the earlier construction of nearby Battersea Bridge, during excavations workers found large quantities of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

and Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

weapons and skeletons in the riverbed, leading many historians to conclude that the area was the site of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

's crossing of the Thames during the 54 BC invasion of Britain

The term Invasion of England may refer to the following planned or actual invasions of what is now modern England, successful or otherwise.

Pre-English Settlement of parts of Britain

* The 55 and 54 BC Caesar's invasions of Britain.

* The 43 AD ...

. The most significant item found was the Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic La Tène style

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and styli ...

bronze and enamel Battersea Shield

The Battersea Shield is one of the most significant pieces of ancient Celtic art found in Britain. It is a sheet bronze covering of a (now vanished) wooden shield decorated in La Tène style. The shield is on display in the British Museum, an ...

, one of the most important pieces of Celtic military equipment found in Britain, recovered from the riverbed during dredging for the piers.

Opening

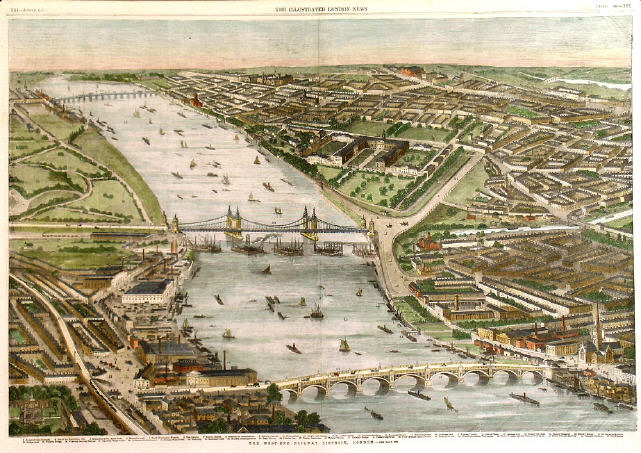

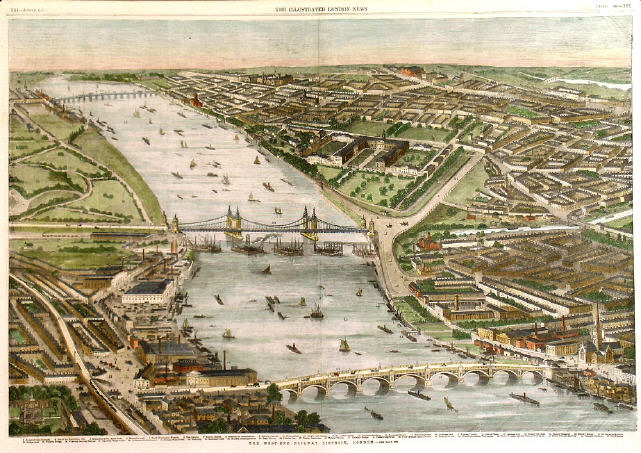

On 31 March 1858 Queen Victoria, accompanied by two of her daughters and ''en route'' to the formal opening of Battersea Park, crossed the new bridge and declared it officially open, naming it the Victoria Bridge; it was opened to the public three days later, on 3 April 1858. The design met with great critical acclaim, particularly from the ''Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

''.

Shortly after its opening, concerns were raised about the bridge's safety. Following an inspection by John Hawkshaw

Sir John Hawkshaw FRS FRSE FRSA MICE (9 April 1811 – 2 June 1891), was an English civil engineer. He served as President of the Institution of Civil Engineers 1862-63. His most noteworthy work is the Severn Tunnel.

Early life

He was born ...

and Edwin Clark in 1861, an additional support chain was added on each side. Despite the strengthening there were still concerns about its soundness, and a weight limit of 5 tons was imposed. At the same time, the name was changed from Victoria Bridge to Chelsea Bridge, as the government was concerned about the reliability of suspension bridges and did not want a potential collapse to be associated with the Queen.

Although reasonably well used, it was unpopular with the public, who objected to being obliged to pay tolls to use it. On 4 July 1857, almost a year before the bridge's opening, a demonstration against the tolls attracted 6,000 residents. Concerns were raised in Parliament that poorer industrial workers in Chelsea, which had no large parks of its own, would be unable to afford to use the new park in Battersea. Bowing to public pressure, shortly after the bridge opened Parliament declared it free to use for pedestrians on Sundays, and in 1875 it was also made toll-free on public holidays. Additionally, because the main lights were only turned on when Queen Victoria was staying in London, it was poorly used at night. Despite this, the new Battersea Park was extremely popular, particularly the sporting facilities; on 9 January 1864 the park staged the world's first official game of

Although reasonably well used, it was unpopular with the public, who objected to being obliged to pay tolls to use it. On 4 July 1857, almost a year before the bridge's opening, a demonstration against the tolls attracted 6,000 residents. Concerns were raised in Parliament that poorer industrial workers in Chelsea, which had no large parks of its own, would be unable to afford to use the new park in Battersea. Bowing to public pressure, shortly after the bridge opened Parliament declared it free to use for pedestrians on Sundays, and in 1875 it was also made toll-free on public holidays. Additionally, because the main lights were only turned on when Queen Victoria was staying in London, it was poorly used at night. Despite this, the new Battersea Park was extremely popular, particularly the sporting facilities; on 9 January 1864 the park staged the world's first official game of association football

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is ...

.

Abolition of tolls

In 1873 the privately owned Albert Bridge, between Chelsea and Battersea bridges, opened. Although Albert Bridge was not as successful as intended at luring customers from Chelsea Bridge and soon found itself in serious financial difficulties, it nonetheless caused a sharp drop in usage of Chelsea Bridge. In 1877 the Metropolis Toll Bridges Act was passed, which allowed theMetropolitan Board of Works

The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was the principal instrument of local government in a wide area of Middlesex, Surrey, and Kent, defined by the Metropolis Management Act 1855, from December 1855 until the establishment of the London County ...

(MBW) to buy all London bridges between Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

...

and Waterloo bridges and free them from tolls. Ownership of Chelsea Bridge was transferred to the MBW in 1877 at a cost of £75,000 (about £ in ), and on 24 May 1879 Chelsea Bridge, Battersea Bridge and Albert Bridge were declared toll free by the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

in a brief ceremony, after which a parade of Chelsea Pensioner

A Chelsea Pensioner, or In-Pensioner, is a resident at the Royal Hospital Chelsea, a retirement home and nursing home for former members of the British Army located in Chelsea, London. The Royal Hospital Chelsea is home to 300 retired British sold ...

s marched across the bridge to Battersea Park.

By the early 20th century, Chelsea Bridge was in poor condition. It was unable to carry the increasing volume of traffic caused by the growth of London and the increasing popularity of the automobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with Wheel, wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, pe ...

; between 1914 and 1929 use of the bridge almost doubled from 6,500 to 12,600 vehicles per day. In addition, parts of its structure were beginning to work loose, and in 1922 the gilded finial

A finial (from '' la, finis'', end) or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the Apex (geometry), apex of a d ...

s on the towers had to be removed because of concerns that they would fall off. Architectural opinion had turned heavily against Victorian styles and Chelsea Bridge was now deeply unpopular with architects; former President of the Royal Institute of British Architects

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three suppl ...

Reginald Blomfield

Sir Reginald Theodore Blomfield (20 December 1856 – 27 December 1942) was a prolific British architect, garden designer and author of the Victorian and Edwardian period.

Early life and career

Blomfield was born at Bow rectory in Devon, w ...

spoke vehemently against its design in 1921, and there were few people supporting the preservation of the old bridge. In 1926 the Royal Commission on Cross-river Traffic recommended that Chelsea Bridge be rebuilt or replaced.

New Chelsea Bridge

In 1931 the

In 1931 the London County Council

London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today kno ...

(LCC) proposed demolishing Chelsea Bridge and replacing it with a modern six-lane bridge at a cost of £695,000 (about £ in ). Because of the economic crisis of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

the Ministry of Transport

A ministry of transport or transportation is a ministry responsible for transportation within a country. It usually is administered by the ''minister for transport''. The term is also sometimes applied to the departments or other government age ...

refused to fund the project and the LCC was unable to raise the funds elsewhere. However, in an effort to boost employment in the Battersea area, which had suffered badly in the depression, the Ministry of Transport agreed to underwrite

Underwriting (UW) services are provided by some large financial institutions, such as banks, insurance companies and investment houses, whereby they guarantee payment in case of damage or financial loss and accept the financial risk for liabilit ...

60% of the costs of a cheaper four-lane bridge costing £365,000 (about £ in ), on condition that all materials used in the building of the bridge be sourced from within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

.

Design and construction

Lambeth Bridge

Lambeth Bridge is a road traffic and footbridge crossing the River Thames in an east–west direction in central London. The river flows north at the crossing point. Downstream, the next bridge is Westminster Bridge; upstream, the next bridge i ...

was moved into place alongside Chelsea Bridge, and demolition began. The new bridge, also called Chelsea Bridge, was designed by LCC architects G. Topham Forrest and E. P. Wheeler and built by Holloway Brothers (London)

Holloway Brothers (London) Ltd was a leading English construction company specialising in building and heavy civil engineering work based in London.

History

Early history

The company was founded as a partnership in 1882 by two brothers, Henry Th ...

. Much wider than the older bridge at wide, it has a wide roadway and two wide pavements cantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is supported at only one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a canti ...

ed out from the sides of the bridge. Uniquely in London, Chelsea Bridge is a self-anchored suspension bridge

A self-anchored suspension bridge is a suspension bridge type in which the main cables attach to the ends of the deck, rather than directly to the ground or via large anchorages. The design is well-suited for construction atop elevated piers, o ...

, the first of the type to be built in Britain. The horizontal stresses are absorbed by stiffening girders in the deck itself and the suspension cables are not anchored to the ground, relieving stress on the abutment

An abutment is the substructure at the ends of a bridge span or dam supporting its superstructure. Single-span bridges have abutments at each end which provide vertical and lateral support for the span, as well as acting as retaining walls ...

s which are built on soft and unstable London clay

The London Clay Formation is a marine geological formation of Ypresian (early Eocene Epoch, c. 56–49 million years ago) age which crops out in the southeast of England. The London Clay is well known for its fossil content. The fossils from t ...

. The piers of the new bridge were built on the site of the old bridge's piers, and are built of concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wi ...

, faced with granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

above the low-water point. Each side of the bridge has a single suspension cable, each made up of 37 1-inch (23mm) diameter wire rope

Steel wire rope (right hand lang lay)

Wire rope is several strands of metal wire twisted into a helix forming a composite

''rope'', in a pattern known as ''laid rope''. Larger diameter wire rope consists of multiple strands of such laid rope in a ...

s bundled to form a hexagonal cable. As was agreed with the Ministry of Transport, all materials used in the bridge came from the British Empire; the steel came from Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

and Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, the granite of the piers from Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, the timbers of the deck from British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

and the asphalt

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term a ...

of the roadway from Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

.

barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

s. The barges were floated into place at low tide, and the rising tide was used to lift the sections above the height of the piers. As the tide ebbed, the roadway dropped into place.

The recently built Battersea Power Station

Battersea Power Station is a decommissioned Grade II* listed coal-fired power station, located on the south bank of the River Thames, in Nine Elms, Battersea, in the London Borough of Wandsworth. It was built by the London Power Company (LPC) ...

then dominated most views of the area, so it was decided that the bridge's appearance was unimportant. Consequently, in contrast to the heavily ornamented 1858 bridge, the new bridge has a starkly utilitarian design and the only ornamentation consists of two ornamental lamp posts at each entrance. Each features a gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships first used as armed cargo carriers by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries during the age of sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch War ...

on top of a coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

. The outward facing sides of all four posts show the LCC coat of arms of the Lion of England, St George's Cross

In heraldry, Saint George's Cross, the Cross of Saint George, is a red cross on a white background, which from the Late Middle Ages became associated with Saint George, the military saint, often depicted as a crusader.

Associated with the cru ...

and the barry Barry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Barry (name), including lists of people with the given name, nickname or surname, as well as fictional characters with the given name

* Dancing Barry, stage name of Barry Richards (born c. 19 ...

wavy

WAVY-TV (channel 10) is a television station licensed to Portsmouth, Virginia, United States, serving the Hampton Roads area as an affiliate of NBC. It is owned by Nexstar Media Group alongside Virginia Beach–licensed Fox affiliate WVBT (c ...

lines representing the Thames; the inward faces on the south side show the dove of peace

Doves, typically domestic pigeons white in plumage, are used in many settings as symbols of peace, freedom, or love. Doves appear in the symbolism of Judaism, Christianity, Islam and paganism, and of both military and pacifist groups.

Mytho ...

of the Metropolitan Borough of Battersea

Battersea was a civil parish and metropolitan borough in the County of London, England. In 1965, the borough was abolished and its area combined with parts of the Metropolitan Borough of Wandsworth to form the London Borough of Wandsworth. The b ...

, that on the northwest corner shows the winged bull, lion, boars' heads and stag of the Metropolitan Borough of Chelsea

The Metropolitan Borough of Chelsea was a metropolitan borough of the County of London between 1900 and 1965. It was created by the London Government Act 1899 from most of the ancient parish of Chelsea. It was amalgamated in 1965 under the Lon ...

, and that on the northeast corner the portcullis

A portcullis (from Old French ''porte coleice'', "sliding gate") is a heavy vertically-closing gate typically found in medieval fortifications, consisting of a latticed grille made of wood, metal, or a combination of the two, which slides down gr ...

and Tudor rose

The Tudor rose (sometimes called the Union rose) is the traditional floral heraldic badge, heraldic emblem of England and takes its name and origins from the House of Tudor, which united the House of Lancaster and the House of York. The Tudor ...

s of the Metropolitan Borough of Westminster.

Prime Minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority the elected Hou ...

, William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

, who was in London for the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

The coronation of George VI and his wife, Elizabeth, as King and Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth, and as Emperor and Empress of India took place at Westminster Abbey, London, on Wednesday 12 May 1937. ...

.

Temporary wartime bridge

Two years after the bridge's opening theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

broke out. Because of their close proximity to Chelsea Barracks

Chelsea Barracks was a British Army barracks located in the City of Westminster, London, between the districts of Belgravia, Chelsea and Pimlico on Chelsea Bridge Road.

The barracks closed in the late 2000s, and the site is currently being redeve ...

it was expected that enemy bombers would target the three road bridges in the area, and a temporary bridge was built parallel to Chelsea Bridge. As with the four other temporary Thames bridges built in this period, it was built of steel girders supported by wooden stakes; however, despite its flimsy appearance it was a sturdy structure, capable of supporting tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s and other heavy military equipment. As it turned out, no enemy action took place in the area, and all three bridges survived the war undamaged. The temporary bridge was dismantled in 1945.

Motorcycle gangs

Beginning in the 1950s, Chelsea Bridge became a favourite meeting place formotorcyclists

Motorcycling is the act of riding a motorcycle. For some people, motorcycling may be the only affordable form of individual motorized transportation, and small- displacement motorcycles are the most common motor vehicle in the most populous c ...

, who would race across the bridge on Friday nights. On 17 October 1970 a serious confrontation took place on Chelsea Bridge between the Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

and Chelsea chapters of the Hells Angels

The Hells Angels Motorcycle Club (HAMC) is a worldwide outlaw motorcycle club whose members typically ride Harley-Davidson motorcycles. In the United States and Canada, the Hells Angels are incorporated as the Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporatio ...

, and rival motorcycle gang

An outlaw motorcycle club is a motorcycle subculture generally centered on the use of cruiser motorcycles, particularly Harley-Davidsons and choppers, and a set of ideals that purport to celebrate freedom, nonconformity to mainstream culture, ...

s the Road Rats, Nightingales, Windsor Angels

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

*Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

and Jokers. Around 50 people took part in the fight; weapons used included motorcycle chains, flick knives and at least one spiked flail. One member of the Jokers was shot with a sawn-off shotgun

A sawed-off shotgun (also called a sawn-off shotgun, short-barreled shotgun, shorty or a boom stick) is a type of shotgun with a shorter gun barrel—typically under —and often a shortened or absent stock. Despite the colloquial term, ...

and fatally wounded, and 20 of those present were sentenced to between one and twelve years' imprisonment.

Present-day

In the 1970s Chelsea Bridge was painted bright red and white, prompting a number of complaints from

In the 1970s Chelsea Bridge was painted bright red and white, prompting a number of complaints from Chelsea F.C.

Chelsea Football Club is an English professional football club based in Fulham, West London. Founded in 1905, they play their home games at Stamford Bridge. The club competes in the Premier League, the top division of English football ...

fans that Chelsea Bridge had been painted in Arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

colours. In 2007 it was redecorated in a less controversial red, blue and white colour scheme. Chelsea Bridge is now floodlit from beneath at night and of light-emitting diode

A light-emitting diode (LED) is a semiconductor device that emits light when current flows through it. Electrons in the semiconductor recombine with electron holes, releasing energy in the form of photons. The color of the light (cor ...

s strung along the towers and suspension chains, intended to complement the illuminations of the nearby Albert Bridge. Although motorcyclists still meet on the bridge, following complaints from residents about the noise their racing has been curtailed.

Chelsea Bridge was declared a Grade II listed structure

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

in 2008, providing protection to preserve its character from further alteration. Battersea Park still retains Cubitt and Pennethorne's original layout and features, including a riverfront promenade

An esplanade or promenade is a long, open, level area, usually next to a river or large body of water, where people may walk. The historical definition of ''esplanade'' was a large, open, level area outside fortress or city walls to provide cle ...

, a formal avenue

Avenue or Avenues may refer to:

Roads

* Avenue (landscape), traditionally a straight path or road with a line of trees, in the shifted sense a tree line itself, or some of boulevards (also without trees)

* Avenue Road, Bangalore

* Avenue Road, ...

through the centre of the park and multiple animal enclosures.

On the eastern side of the bridge, at the southern end, a major new residential development of 600 homes called Chelsea Bridge Wharf has been built, as part of long-term plans to regenerate the long-derelict former industrial sites around Battersea Power Station.

Battersea footbridge

Thames Path

The Thames Path is a National Trail following the River Thames from its source near Kemble, Gloucestershire, Kemble in Gloucestershire to the Woolwich foot tunnel, south east London. It is about long. A path was first proposed in 1948 but it onl ...

. The new bridge curves out from the bank, overhanging the river bank by , and cost £600,000 to build.

See also

*List of crossings of the River Thames

The River Thames is the second-longest river in the United Kingdom, passes through the capital city, and has many crossings.

Counting every channel – such as by its islands linked to only one bank – it is crossed by over 300 brid ...

* List of bridges in London

List of bridges in London lists the major bridges within Greater London or within the influence of London. Most of these are river crossings, and the best-known are those across the River Thames. Several bridges on other rivers have given thei ...

Notes and references

Notes References Bibliography * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{Featured article Bridges completed in 1937 Bridges across the River Thames Grade II listed buildings in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Grade II listed buildings in the London Borough of Wandsworth Rebuilt buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Grade II listed bridges in London Self-anchored suspension bridges Transport in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Transport in the London Borough of Wandsworth Former toll bridges in England Bridge light displays