Cheetah With Impala on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The cheetah (''Acinonyx jubatus'') is a large

In 1777,

In 1777,

The king cheetah is a variety of cheetah with a rare

The king cheetah is a variety of cheetah with a rare

The cheetah is a lightly built, spotted cat characterised by a small rounded head, a short

The cheetah is a lightly built, spotted cat characterised by a small rounded head, a short

Cheetahs appear to be less selective in habitat choice than other felids and inhabit a variety of

Cheetahs appear to be less selective in habitat choice than other felids and inhabit a variety of

In prehistoric times, the cheetah was distributed throughout Africa, Asia and Europe. It gradually fell to extinction in Europe, possibly because of competition with the lion. Today the cheetah has been

In prehistoric times, the cheetah was distributed throughout Africa, Asia and Europe. It gradually fell to extinction in Europe, possibly because of competition with the lion. Today the cheetah has been

Until the 1970s, cheetahs and other carnivores were frequently killed to protect livestock in Africa. Gradually the understanding of cheetah ecology increased and their falling numbers became a matter of concern. The De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre was set up in 1971 in South Africa to provide care for wild cheetahs regularly trapped or injured by Namibian farmers. By 1987, the first major research project to outline cheetah conservation strategies was underway. The

Until the 1970s, cheetahs and other carnivores were frequently killed to protect livestock in Africa. Gradually the understanding of cheetah ecology increased and their falling numbers became a matter of concern. The De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre was set up in 1971 in South Africa to provide care for wild cheetahs regularly trapped or injured by Namibian farmers. By 1987, the first major research project to outline cheetah conservation strategies was underway. The

File:War trophies Deir el Bahari Wellcome L0027402.jpg, alt=A hieroglyph depicting two leashed cheetahs, A

The first cheetah to be brought into captivity in a zoo was at the

The first cheetah to be brought into captivity in a zoo was at the

The cheetah has been widely portrayed in a variety of artistic works. In ''

The cheetah has been widely portrayed in a variety of artistic works. In '' Two cheetahs are depicted standing upright and supporting a crown in the

Two cheetahs are depicted standing upright and supporting a crown in the

cat

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members of ...

native to Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and central Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. It is the fastest

Fastest is a model-based testing tool that works with specifications written in the Z notation. The tool implements the Test Template Framework (TTF) proposed by Phil Stocks and David Carrington in .

Usage

Fastest presents a command-line user ...

land animal, estimated to be capable of running at with the fastest reliably recorded speeds being , and as such has evolved specialized adaptations for speed, including a light build, long thin legs and a long tail. It typically reaches at the shoulder, and the head-and-body length is between . Adults weigh between . Its head is small and rounded, with a short snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, rostrum, or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the nose of many mammals is c ...

and black tear-like facial streaks. The coat is typically tawny to creamy white or pale buff and is mostly covered with evenly spaced, solid black spots. Four subspecies are recognised.

The cheetah lives in three main social group

In the social sciences, a social group can be defined as two or more people who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and collectively have a sense of unity. Regardless, social groups come in a myriad of sizes and varieties ...

s: females and their cubs, male "coalitions", and solitary males. While females lead a nomadic life searching for prey in large home range

A home range is the area in which an animal lives and moves on a periodic basis. It is related to the concept of an animal's territory which is the area that is actively defended. The concept of a home range was introduced by W. H. Burt in 1943. He ...

s, males are more sedentary and instead establish much smaller territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

in areas with plentiful prey and access to females. The cheetah is active during the day, with peaks during dawn and dusk. It feeds on small- to medium-sized prey, mostly weighing under , and prefers medium-sized ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Ungulata which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. These include odd-toed ungulates such as horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and even-toed ungulates such as cattle, pigs, giraffes, cam ...

s such as impala

The impala or rooibok (''Aepyceros melampus'') is a medium-sized antelope found in eastern and southern Africa. The only extant member of the genus '' Aepyceros'' and tribe Aepycerotini, it was first described to European audiences by Germa ...

, springbok

The springbok (''Antidorcas marsupialis'') is a medium-sized antelope found mainly in south and southwest Africa. The sole member of the genus ''Antidorcas'', this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm v ...

and Thomson's gazelle

Thomson's gazelle (''Eudorcas thomsonii'') is one of the best known species of gazelles. It is named after explorer Joseph Thomson and is sometimes referred to as a "tommie". It is considered by some to be a subspecies of the red-fronted gazelle a ...

s. The cheetah typically stalks its prey to within , charges towards it, trips it during the chase and bites its throat to suffocate it to death. It breeds throughout the year. After a gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during pregna ...

of nearly three months, a litter of typically three or four cubs is born. Cheetah cubs are highly vulnerable to predation by other large carnivores such as hyena

Hyenas, or hyaenas (from Ancient Greek , ), are feliform carnivoran mammals of the family Hyaenidae . With only four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the Carnivora and one of the smallest in the clas ...

s and lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphi ...

s. They are weaned at around four months and are independent by around 20 months of age.

The cheetah occurs in a variety of habitats such as savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

hs in the Serengeti

The Serengeti ( ) ecosystem is a geographical region in Africa, spanning northern Tanzania. The protected area within the region includes approximately of land, including the Serengeti National Park and several game reserves. The Serengeti ...

, arid mountain ranges in the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

and hilly desert terrain in Iran. The cheetah is threatened by several factors such as habitat loss

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

, conflict with humans, poaching and high susceptibility to diseases. Historically ranging throughout most of Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

and extending eastward into the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and to central India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the cheetah is now distributed mainly in small, fragmented populations in central Iran and southern, eastern and northwestern Africa. In 2016, the global cheetah population was estimated at 7,100 individuals in the wild; it is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biol ...

. In September 2022, they were reintroduced to India after being extinct in the country for 70 years. In the past, cheetahs were tamed

A tame animal is an animal that is relatively tolerant of human presence. Tameness may arise naturally (as in the case, for example, of island tameness) or due to the deliberate, human-directed process of animal training, training an animal again ...

and trained for hunting ungulates. They have been widely depicted in art, literature, advertising, and animation.

Etymology

The vernacular name "cheetah" is derived from Hindustani ur, چیتا and hi, चीता (). This in turn comes from sa, चित्रय () meaning 'variegated', 'adorned' or 'painted'. In the past, the cheetah was often called "hunting leopard" because they could be tamed and used forcoursing

Coursing by humans is the pursuit of game or other animals by dogs—chiefly greyhounds and other sighthounds—catching their prey by speed, running by sight, but not by scent. Coursing was a common hunting technique, practised by the nobility, t ...

. The generic name ''Acinonyx'' probably derives from the combination of two Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

words: () meaning 'unmoved' or 'motionless', and () meaning 'nail' or 'hoof'. A rough translation is "immobile nails", a reference to the cheetah's limited ability to retract its claws. A similar meaning can be obtained by the combination of the Greek prefix ''a–'' (implying a lack of) and () meaning 'to move' or 'to set in motion'. The specific name is Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for 'crested, having a mane'.

A few old generic names such as ''Cynailurus'' and ''Cynofelis'' allude to the similarities between the cheetah and canid

Canidae (; from Latin, ''canis'', "dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to as dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). There are three subfamilies found within the ...

s.

Taxonomy

In 1777,

In 1777, Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber

Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber (17 January 1739 in Weißensee, Thuringia – 10 December 1810 in Erlangen), often styled J.C.D. von Schreber, was a German naturalist.

Career

He was appointed professor of'' materia medica'' at the Univers ...

described the cheetah based on a skin from the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

and gave it the scientific name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

''Felis jubatus''. Joshua Brookes

Joshua Brookes (24 November 1761 – 10 January 1833) was a British anatomist and naturalist.

Early life

Brookes studied under William Hunter, William Hewson, Andrew Marshall, and John Sheldon, in London. He then attended the practice of ...

proposed the generic

Generic or generics may refer to:

In business

* Generic term, a common name used for a range or class of similar things not protected by trademark

* Generic brand, a brand for a product that does not have an associated brand or trademark, other ...

name ''Acinonyx'' in 1828. In 1917, Reginald Innes Pocock

Reginald Innes Pocock F.R.S. (4 March 1863 – 9 August 1947) was a British zoologist.

Pocock was born in Clifton, Bristol, the fourth son of Rev. Nicholas Pocock and Edith Prichard. He began showing interest in natural history at St. Edward ...

placed the cheetah in a subfamily of its own, Acinonychinae, given its striking morphological resemblance to the greyhound

The English Greyhound, or simply the Greyhound, is a breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing, greyhound racing and hunting. Since the rise in large-scale adoption of retired racing Greyhounds, the breed has seen a resurge ...

and significant deviation from typical felid features; the cheetah was classified in Felinae

The Felinae are a subfamily of the family Felidae. This subfamily comprises the small cats having a bony hyoid, because of which they are able to purr but not roar.

Other authors have proposed an alternative definition for this subfamily: as c ...

in later taxonomic revisions.

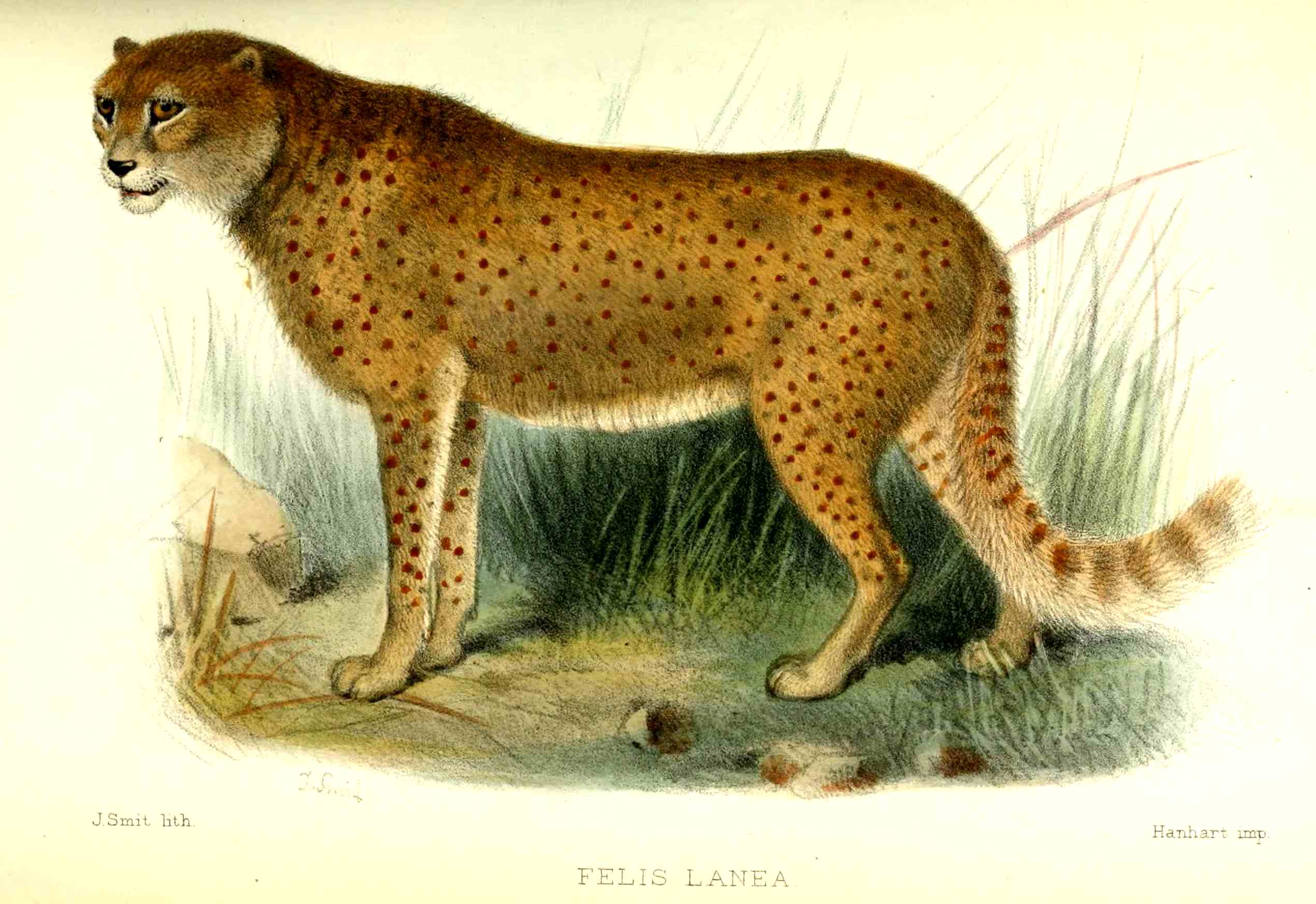

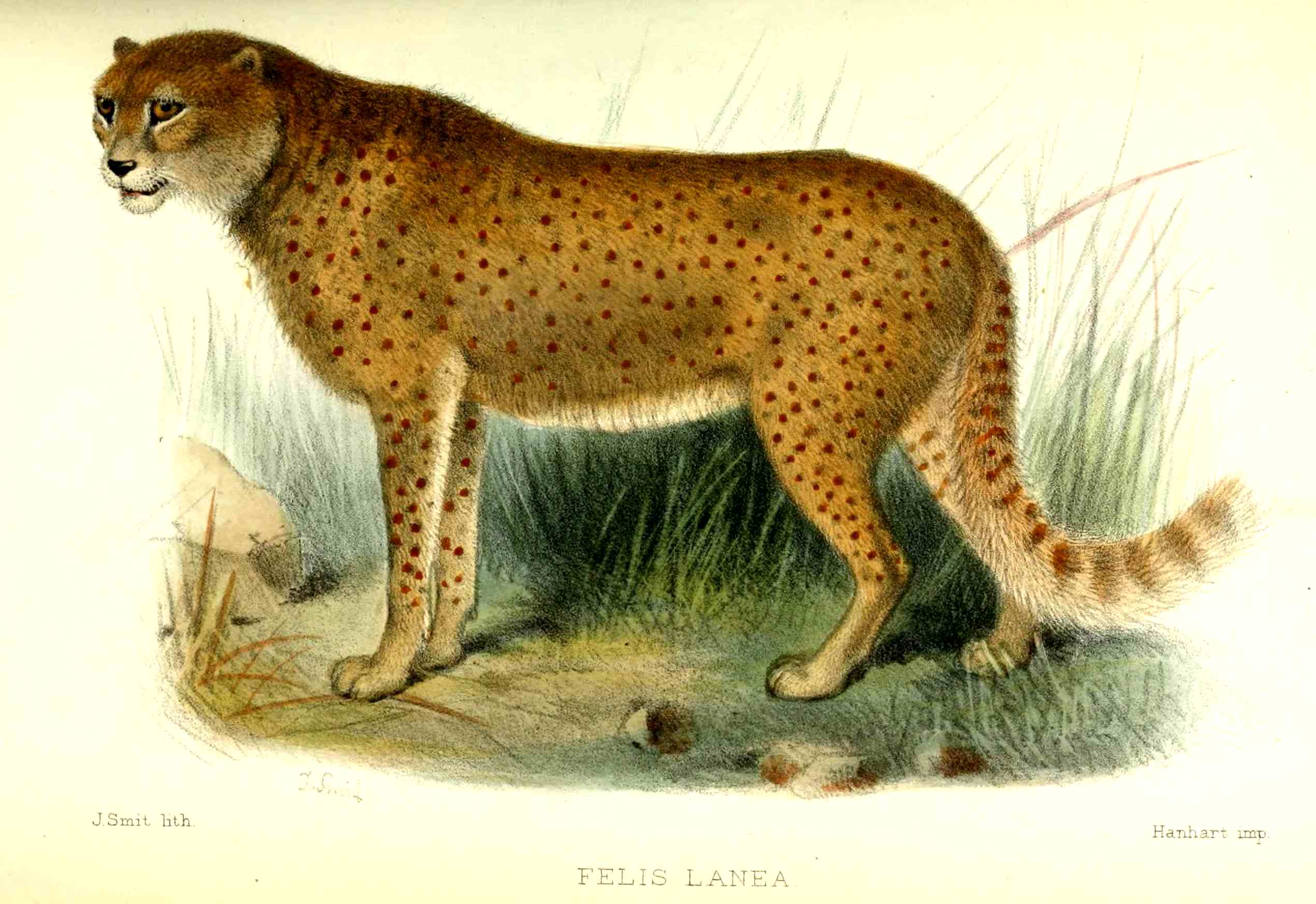

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several cheetah specimens were described; some were proposed as subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

. An example is the South African specimen known as the "woolly cheetah", named for its notably dense fur—this was described as a new species (''Felis lanea'') by Philip Sclater

Philip Lutley Sclater (4 November 1829 – 27 June 1913) was an England, English lawyer and zoologist. In zoology, he was an expert ornithologist, and identified the main zoogeographic regions of the world. He was Secretary of the Zoological ...

in 1877, but the classification was mostly disputed. There has been considerable confusion in the nomenclature of cheetahs and leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant species in the genus '' Panthera'', a member of the cat family, Felidae. It occurs in a wide range in sub-Saharan Africa, in some parts of Western and Central Asia, Southern Russia, a ...

s (''Panthera pardus'') as authors often confused the two; some considered "hunting leopards" an independent species, or equal to the leopard.

Subspecies

In 1975, five subspecies were considered validtaxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

: ''A. j. hecki'', ''A. j. jubatus'', ''A. j. raineyi'', ''A. j. soemmeringii'' and ''A. j. venaticus''. In 2011, a phylogeographic

Phylogeography is the study of the historical processes that may be responsible for the past to present geographic distributions of genealogical lineages. This is accomplished by considering the geographic distribution of individuals in light of ge ...

study found minimal genetic variation

Genetic variation is the difference in DNA among individuals or the differences between populations. The multiple sources of genetic variation include mutation and genetic recombination. Mutations are the ultimate sources of genetic variation, ...

between ''A. j. jubatus'' and ''A. j. raineyi''; only four subspecies were identified. In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy and recognised these four subspecies as valid. Their details are tabulated below:

Phylogeny and evolution

The cheetah's closest relatives are thecougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large Felidae, cat native to the Americas. Its Species distribution, range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mamm ...

(''Puma concolor'') and the jaguarundi

The jaguarundi (''Herpailurus yagouaroundi'') is a wild cat native to the Americas. Its range extends from central Argentina in the south to northern Mexico, through Central and South America east of the Andes. The jaguarundi is a medium-sized ...

(''Herpailurus yagouaroundi''). Together, these three species form the ''Puma'' lineage, one of the eight lineages of the extant felid

Felidae () is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid (). The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the dom ...

s; the ''Puma'' lineage diverged from the rest 6.7 mya. The sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

of the ''Puma'' lineage is a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

of smaller Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

cats that includes the genera ''Felis

''Felis'' is a genus of small and medium-sized cat species native to most of Africa and south of 60° latitude in Europe and Asia to Indochina. The genus includes the domestic cat. The smallest ''Felis'' species is the black-footed cat with a he ...

'', ''Otocolobus

The Pallas's cat (''Otocolobus manul'', also known as the manul, is a small wild cat with long and dense light grey fur. Its rounded ears are set low on the sides of the head. Its head-and-body length ranges from with a long bushy tail. It is ...

'' and ''Prionailurus

''Prionailurus'' is a genus of spotted, small wild cats native to Asia. Forests are their preferred habitat; they feed on small mammals, reptiles and birds, and occasionally aquatic wildlife.

Taxonomy

''Prionailurus'' was first proposed by ...

''.

The oldest cheetah fossils, excavated in eastern and southern Africa, date to 3.5–3 mya; the earliest known specimen from South Africa is from the lowermost deposits of the Silberberg Grotto (Sterkfontein

Sterkfontein (Afrikaans for ''Strong Spring'') is a set of limestone caves of special interest to paleo-anthropologists located in Gauteng province, about northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa in the Muldersdrift area close to the town of K ...

). Though incomplete, these fossils indicate forms larger but less cursorial

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often u ...

than the modern cheetah. Fossil remains from Europe are limited to a few Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. The ...

specimens from Hundsheim

Hundsheim is a town in the district of Bruck an der Leitha in Lower Austria, in northeast Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Easter ...

(Austria) and Mosbach Sands (Germany). Cheetah-like cats are known from as late as 10,000 years ago from the Old World. The giant cheetah

The giant cheetah (''Acinonyx pardinensis'') is an extinct felid species that was closely related to the modern cheetah.

Description

The lifestyle and physical characteristics of the giant cheetah were probably similar to those of its modern ...

(''A. pardinensis''), significantly larger and slower compared to the modern cheetah, occurred in Eurasia and eastern and southern Africa in the Villafranchian

Villafranchian age ( ) is a period of geologic time (3.5–1.0 Ma) spanning the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene used more specifically with European Land Mammal Ages. Named by Italian geologist Lorenzo Pareto for a sequence of terrestrial s ...

period roughly 3.8–1.9 mya. In the Middle Pleistocene a smaller cheetah, ''A. intermedius'', ranged from Europe to China. The modern cheetah appeared in Africa around 1.9 mya; its fossil record is restricted to Africa.

Extinct North American cheetah-like cats had historically been classified in ''Felis'', ''Puma'' or ''Acinonyx''; two such species, ''F. studeri'' and ''F. trumani'', were considered to be closer to the puma than the cheetah, despite their close similarities to the latter. Noting this, palaeontologist Daniel Adams proposed ''Miracinonyx

The American cheetah is either of two feline species of the extinct genus ''Miracinonyx'', endemic to North America during the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 12,000 years ago) and morphologically similar to the modern cheetah (''Acinonyx jub ...

'', a new subgenus under ''Acinonyx'', in 1979 for the North American cheetah-like cats; this was later elevated to genus rank. Adams pointed out that North American and Old World cheetah-like cats may have had a common ancestor, and ''Acinonyx'' might have originated in North America instead of Eurasia. However, subsequent research has shown that ''Miracinonyx'' is phylogenetically closer to the cougar than the cheetah; the similarities to cheetahs have been attributed to convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

.

The three species of the ''Puma'' lineage may have had a common ancestor during the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

(roughly 8.25 mya). Some suggest that North American cheetahs possibly migrated to Asia via the Bering Strait, then dispersed southward to Africa through Eurasia at least 100,000 years ago; some authors have expressed doubt over the occurrence of cheetah-like cats in North America, and instead suppose the modern cheetah to have evolved from Asian populations that eventually spread to Africa. The cheetah is thought to have experienced two population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as specicide, widespread violen ...

s that greatly decreased the genetic variability

Genetic variability is either the presence of, or the generation of, genetic differences.

It is defined as "the formation of individuals differing in genotype, or the presence of genotypically different individuals, in contrast to environmentally i ...

in populations; one occurred about 100,000 years ago that has been correlated to migration from North America to Asia, and the second 10,000–12,000 years ago in Africa, possibly as part of the Late Pleistocene extinction event.

Genetics

Thediploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

number of chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s in the cheetah is 38, the same as in most other felids. The cheetah was the first felid observed to have unusually low genetic variability among individuals, which has led to poor breeding in captivity, increased spermatozoa

A spermatozoon (; also spelled spermatozoön; ; ) is a motile sperm cell, or moving form of the haploid cell that is the male gamete. A spermatozoon joins an ovum to form a zygote. (A zygote is a single cell, with a complete set of chromosomes, ...

l defects, high juvenile mortality and increased susceptibility to diseases and infections. A prominent instance was the deadly feline coronavirus

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is a positive-stranded RNA virus that infects cats worldwide. It is a coronavirus of the species ''Alphacoronavirus 1'' which includes canine coronavirus (CCoV) and porcine transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGE ...

outbreak in a cheetah breeding facility of Oregon in 1983 which had a mortality rate of 60%—higher than that recorded for previous epizootic

In epizoology, an epizootic (from Greek: ''epi-'' upon + ''zoon'' animal) is a disease event in a nonhuman animal population analogous to an epidemic in humans. An epizootic may be restricted to a specific locale (an "outbreak"), general (an "epi ...

s of feline infectious peritonitis

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is the name given to a common and aberrant immune response to infection with feline coronavirus (FCoV).

The virus and pathogenesis of FIP

FCoV is a virus of the gastrointestinal tract. Most infections are eit ...

in any felid. The remarkable homogeneity in cheetah genes has been demonstrated by experiments involving the major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are calle ...

(MHC); unless the MHC genes are highly homogeneous in a population, skin grafts

Skin grafting, a type of graft surgery, involves the transplantation of skin. The transplanted tissue is called a skin graft.

Surgeons may use skin grafting to treat:

* extensive wounding or trauma

* burns

* areas of extensive skin loss du ...

exchanged between a pair of unrelated individuals would be rejected. Skin grafts exchanged between unrelated cheetahs are accepted well and heal, as if their genetic makeup were the same.

The low genetic diversity is thought to have been created by two population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as specicide, widespread violen ...

s from c. 100,000 years and c. 12,000 years ago, respectively. The resultant level of genetic variation is around 0.1–4% of average living species, lower than that of Tasmanian devil

The Tasmanian devil (''Sarcophilus harrisii'') (palawa kani: purinina) is a carnivorous marsupial of the family Dasyuridae. Until recently, it was only found on the island state of Tasmania, but it has been reintroduced to New South Wales in ...

s, Virunga gorilla

The mountain gorilla (''Gorilla beringei beringei'') is one of the two subspecies of the eastern gorilla. It is listed as endangered by the IUCN as of 2018.

There are two populations: One is found in the Virunga volcanic mountains of Central/ ...

s, Amur tiger

The Siberian tiger or Amur tiger is a population of the tiger subspecies ''Panthera tigris tigris'' native to the Russian Far East, Northeast China and possibly North Korea. It once ranged throughout the Korean Peninsula, but currently inhabit ...

s, and even highly inbred domestic cats and dogs.

King cheetah

The king cheetah is a variety of cheetah with a rare

The king cheetah is a variety of cheetah with a rare mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

for cream-coloured fur marked with large, blotchy spots and three dark, wide stripes extending from the neck to the tail. In Manicaland

Manicaland is a Provinces of Zimbabwe, province in eastern Zimbabwe. After Harare Province, it is the country's second-most populous province, with a population of 2.037 million, as of the 2012 Zimbabwe census, 2022 census. After Harare and Bulawa ...

, Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

, it was known as ''nsuifisi'' and thought to be a cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a sa ...

between a leopard and a hyena

Hyenas, or hyaenas (from Ancient Greek , ), are feliform carnivoran mammals of the family Hyaenidae . With only four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the Carnivora and one of the smallest in the clas ...

. In 1926 Major A. Cooper wrote about a cheetah-like animal he had shot near modern-day Harare

Harare (; formerly Salisbury ) is the capital and most populous city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of 940 km2 (371 mi2) and a population of 2.12 million in the 2012 census and an estimated 3.12 million in its metropolitan ...

, with fur as thick as that of a snow leopard

The snow leopard (''Panthera uncia''), also known as the ounce, is a Felidae, felid in the genus ''Panthera'' native to the mountain ranges of Central Asia, Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable species, Vulnerable on the IUCN Red ...

and spots that merged to form stripes. He suggested it could be a cross between a leopard and a cheetah. As more such individuals were observed it was seen that they had non-retractable claws like the cheetah.

In 1927, Pocock described these individuals as a new species by the name of ''Acinonyx rex'' ("king cheetah"). However, in the absence of proof to support his claim, he withdrew his proposal in 1939. Abel Chapman

Abel Chapman (1851–1929) was an English, Sunderland-born hunter- naturalist. He contributed in saving the Spanish Ibex from extinction and helped in the establishment of South Africa's first game reserve.

Early life

Abel Chapman was born at 2 ...

considered it a colour morph

In biology, polymorphism is the occurrence of two or more clearly different morphs or forms, also referred to as alternative ''phenotypes'', in the population of a species. To be classified as such, morphs must occupy the same habitat at the s ...

of the normally spotted cheetah. Since 1927 the king cheetah has been reported five more times in the wild in Zimbabwe, Botswana and northern Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

; one was photographed in 1975.

In 1981, two female cheetahs that had mated with a wild male from Transvaal at the De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre

The De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre, also known as Ann van Dyk Cheetah Centre is a captive breeding facility for South African cheetahs and other animals that is situated in the foothills of the Magaliesberg mountain range (near Brits and ...

(South Africa) gave birth to one king cheetah each; subsequently, more king cheetahs were born at the centre. In 2012, the cause of this coat pattern was found to be a mutation in the gene for transmembrane

A transmembrane protein (TP) is a type of integral membrane protein that spans the entirety of the cell membrane. Many transmembrane proteins function as gateways to permit the transport of specific substances across the membrane. They frequentl ...

aminopeptidase

Aminopeptidases are enzymes that catalyze the cleavage of amino acids from the amino terminus (N-terminus) of proteins or peptides (exopeptidases). They are widely distributed throughout the animal and plant kingdoms and are found in many subcell ...

(Taqpep), the same gene responsible for the striped "mackerel" versus blotchy "classic" pattern seen in tabby cats. The appearance is caused by reinforcement of a recessive allele

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

; hence if two mating cheetahs are heterozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

carriers of the mutated allele, a quarter of their offspring can be expected to be king cheetahs.

Characteristics

The cheetah is a lightly built, spotted cat characterised by a small rounded head, a short

The cheetah is a lightly built, spotted cat characterised by a small rounded head, a short snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, rostrum, or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the nose of many mammals is c ...

, black tear-like facial streaks, a deep chest, long thin legs and a long tail. Its slender, canine-like form is highly adapted for speed, and contrasts sharply with the robust build of the genus ''Panthera

''Panthera'' is a genus within the family (biology), family Felidae that was named and described by Lorenz Oken in 1816 who placed all the spotted cats in this group. Reginald Innes Pocock revised the classification of this genus in 1916 as co ...

''. Cheetahs typically reach at the shoulder and the head-and-body length is between . The weight can vary with age, health, location, sex and subspecies; adults typically range between . Cubs born in the wild weigh at birth, while those born in captivity tend to be larger and weigh around . Cheetahs are sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, with males larger and heavier than females, but not to the extent seen in other large cats. Studies differ significantly on morphological variations among the subspecies.

The coat is typically tawny to creamy white or pale buff (darker in the mid-back portion). The chin, throat and underparts of the legs and the belly are white and devoid of markings. The rest of the body is covered with around 2,000 evenly spaced, oval or round solid black spots, each measuring roughly . Each cheetah has a distinct pattern of spots which can be used to identify unique individuals. Besides the clearly visible spots, there are other faint, irregular black marks on the coat. Newly born cubs are covered in fur with an unclear pattern of spots that gives them a dark appearance—pale white above and nearly black on the underside. The hair is mostly short and often coarse, but the chest and the belly are covered in soft fur; the fur of king cheetahs has been reported to be silky. There is a short, rough mane, covering at least along the neck and the shoulders; this feature is more prominent in males. The mane starts out as a cape of long, loose blue to grey hair in juveniles. Melanistic

The term melanism refers to black pigment and is derived from the gr, μελανός. Melanism is the increased development of the dark-colored pigment melanin in the skin or hair.

Pseudomelanism, also called abundism, is another variant of pi ...

cheetahs are rare and have been seen in Zambia and Zimbabwe. In 1877–1878, Sclater described two partially albino

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

specimens from South Africa.

The head is small and more rounded compared to other big cat

The term "big cat" is typically used to refer to any of the five living members of the genus '' Panthera'', namely the tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard.

Despite enormous differences in size, various cat species are quite similar ...

s. Saharan cheetahs have canine-like slim faces. The ears are small, short and rounded; they are tawny at the base and on the edges and marked with black patches on the back. The eyes are set high and have round pupils

The pupil is a black hole located in the center of the iris of the eye that allows light to strike the retina.Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990) ''Dictionary of Eye Terminology''. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company. It appears black ...

. The whiskers, shorter and fewer than those of other felids, are fine and inconspicuous. The pronounced tear streaks (or malar stripes), unique to the cheetah, originate from the corners of the eyes and run down the nose to the mouth. The role of these streaks is not well understood—they may protect the eyes from the sun's glare (a helpful feature as the cheetah hunts mainly during the day), or they could be used to define facial expressions. The exceptionally long and muscular tail, with a bushy white tuft at the end, measures . While the first two-thirds of the tail are covered in spots, the final third is marked with four to six dark rings or stripes.

The cheetah is superficially similar to the leopard, which has a larger head, fully retractable claws, rosettes instead of spots, lacks tear streaks and is more muscular. Moreover, the cheetah is taller than the leopard. The serval

The serval (''Leptailurus serval'') is a wild cat native to Africa. It is widespread in sub-Saharan countries, except rainforest regions. Across its range, it occurs in protected areas, and hunting it is either prohibited or regulated in ran ...

also resembles the cheetah in physical build, but is significantly smaller, has a shorter tail and its spots fuse to form stripes on the back. The cheetah appears to have evolved convergently with canids in morphology and behaviour; it has canine-like features such as a relatively long snout, long legs, a deep chest, tough paw pads and blunt, semi-retractable claws. The cheetah has often been likened to the greyhound, as both have similar morphology and the ability to reach tremendous speeds in a shorter time than other mammals, but the cheetah can attain much higher maximum speeds.

Internal anatomy

Sharply contrasting with the other big cats in its morphology, the cheetah shows several specialized adaptations for prolonged chases to catch prey at some of the fastest speeds reached by land animals. Its light, streamlined body makes it well-suited to short, explosive bursts of speed, rapid acceleration, and an ability to execute extreme changes in direction while moving at high speed. The largenasal passage

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nasal c ...

s, accommodated well due to the smaller size of the canine teeth, ensure fast flow of sufficient air, and the enlarged heart and lungs allow the enrichment of blood with oxygen in a short time. This allows cheetahs to rapidly regain their stamina after a chase. During a typical chase, their respiratory rate

The respiratory rate is the rate at which breathing occurs; it is set and controlled by the respiratory center of the brain. A person's respiratory rate is usually measured in breaths per minute.

Measurement

The respiratory rate in humans is mea ...

increases from 60 to 150 breaths per minute. Moreover, the reduced viscosity

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the inte ...

of the blood at higher temperatures (common in frequently moving muscles) could ease blood flow and increase oxygen transport

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the ci ...

. While running, in addition to having good traction due to their semi-retractable claws, cheetahs use their tail as a rudder-like means of steering that enables them to make sharp turns, necessary to outflank antelopes which often change direction to escape during a chase. The protracted claws increase grip over the ground, while rough paw pads make the sprint more convenient over tough ground. The limbs of the cheetah are longer than what is typical for other cats its size; the thigh muscles are large, and the tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

and fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity is ...

are held close together making the lower legs less likely to rotate. This reduces the risk of losing balance during runs, but compromises the cat's ability to climb trees. The highly reduced clavicle

The clavicle, or collarbone, is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately 6 inches (15 cm) long that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on the left and one on the rig ...

is connected through ligament

A ligament is the fibrous connective tissue that connects bones to other bones. It is also known as ''articular ligament'', ''articular larua'', ''fibrous ligament'', or ''true ligament''. Other ligaments in the body include the:

* Peritoneal li ...

s to the scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eithe ...

, whose pendulum-like motion increases the stride length and assists in shock absorption. The extension of the vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordata, ...

can add as much as to the stride length.

The cheetah resembles the smaller cats in cranial

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

features, and in having a long and flexible spine, as opposed to the stiff and short one in other large felids. The roughly triangular skull has light, narrow bones and the sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are exceptiona ...

is poorly developed, possibly to reduce weight and enhance speed. The mouth can not be opened as widely as in other cats given the shorter length of muscles between the jaw and the skull. A study suggested that the limited retraction of the cheetah's claws may result from the earlier truncation of the development of the middle phalanx bone

The phalanges (singular: ''phalanx'' ) are digital bones in the hands and feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are classed as long bones.

...

in cheetahs.

The cheetah has a total of 30 teeth; the dental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiolo ...

is . The sharp, narrow carnassial

Carnassials are paired upper and lower teeth modified in such a way as to allow enlarged and often self-sharpening edges to pass by each other in a shearing manner. This adaptation is found in carnivorans, where the carnassials are the modified f ...

s are larger than those of leopards and lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphi ...

s, suggesting the cheetah can consume larger amount of food in a given time period. The small, flat canines

Canine may refer to:

Zoology and anatomy

* a dog-like Canid animal in the subfamily Caninae

** ''Canis'', a genus including dogs, wolves, coyotes, and jackals

** Dog, the domestic dog

* Canine tooth, in mammalian oral anatomy

People with the surn ...

are used to bite the throat and suffocate the prey. A study gave the bite force quotient

Bite force quotient (BFQ) is a numerical value commonly used to represent the bite force of an animal, while also taking factors like the animal's size into account.

The BFQ is calculated as the regression of the quotient of an animal's bite f ...

(BFQ) of the cheetah as 119, close to that for the lion (112), suggesting that adaptations for a lighter skull may not have reduced the power of the cheetah's bite. Unlike other cats, the cheetah's canines have no gap behind them when the jaws close, as the top and bottom cheek teeth show extensive overlap; this equips the upper and lower teeth to effectively tear through the meat. The slightly curved claws, shorter and straighter than those of other cats, lack a protective sheath and are partly retractable. The claws are blunt due to lack of protection, but the large and strongly curved dewclaw

A dewclaw is a digit – vestigial in some animals – on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digit ...

is remarkably sharp. Cheetahs have a high concentration of nerve cell

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. No ...

s arranged in a band in the centre of the eyes, a visual streak, the most efficient among felids. This significantly sharpens the vision and enables the cheetah to swiftly locate prey against the horizon. The cheetah is unable to roar due to the presence of a sharp-edged vocal fold within the larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

.

Speed and acceleration

The cheetah is the world'sfastest

Fastest is a model-based testing tool that works with specifications written in the Z notation. The tool implements the Test Template Framework (TTF) proposed by Phil Stocks and David Carrington in .

Usage

Fastest presents a command-line user ...

land animal. Estimates of the maximum speed attained range from . A commonly quoted value is , recorded in 1957, but this measurement is disputed. In 2012, an 11-year-old cheetah (named Sarah

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a piou ...

) from the Cincinnati Zoo

The Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden is the sixth oldest zoo in the United States, founded in 1873 and officially opening in 1875. It is located in the Avondale neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio. It originally began with in the middle of the c ...

set a world record by running in 5.95 seconds over a set run, recording a maximum speed of .

Contrary to the common belief that cheetahs hunt by simply chasing its prey at high speeds, the findings of two studies in 2013 observing hunting cheetahs using GPS collar

GPS animal tracking is a process whereby biologists, scientific researchers or conservation agencies can remotely observe relatively fine-scale movement or migratory patterns in a free-ranging wild animal using the Global Positioning System ( ...

s show that cheetahs hunt at speeds much lower than the highest recorded for them during most of the chase, interspersed with a few short bursts (lasting only seconds) when they attain peak speeds. In one of the studies, the average speed recorded during the high speed phase was , or within the range including error. The highest recorded value was . The researchers suggested that a hunt consists of two phases—an initial fast acceleration phase when the cheetah tries to catch up with the prey, followed by slowing down as it closes in on it, the deceleration varying by the prey in question. The peak acceleration observed was , while the peak deceleration value was . Speed and acceleration values for a hunting cheetah may be different from those for a non-hunter because while engaged in the chase, the cheetah is more likely to be twisting and turning and may be running through vegetation. The speeds attained by the cheetah may be only slightly greater than those achieved by the pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American a ...

at and the springbok

The springbok (''Antidorcas marsupialis'') is a medium-sized antelope found mainly in south and southwest Africa. The sole member of the genus ''Antidorcas'', this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm v ...

at , but the cheetah additionally has an exceptional acceleration.

One stride of a galloping cheetah measures ; the stride length and the number of jumps increases with speed. During more than half the duration of the sprint, the cheetah has all four limbs in the air, increasing the stride length. Running cheetahs can retain up to 90% of the heat generated during the chase. A 1973 study suggested the length of the sprint is limited by excessive build-up of body heat when the body temperature reaches . However, a 2013 study recorded the average temperature of cheetahs after hunts to be , suggesting high temperatures need not cause hunts to be abandoned.

The running speed of of the cheetah was obtained as an result of a single run of one individual by dividing the distance traveled for time spent. The run lasted 2.25 seconds and was supposed to have been long, but was later found to have been long. It was therefore discredited for a faulty method of measurement.

Cheetahs have subsequently been measured at running at a speed of as an average of three runs including in opposite direction, for a single individual, over a marked course, even starting the run behind the start line, starting the run already running on the course. Again dividing the distance by time, but this time to determine the maximum sustained speed, completing the runs in an average time of 7 seconds. Being a more accurate method of measurement, this test was made in 1965 but published in 1997.

Subsequently with GPS-IMU collars, running speed was measured for wild cheetahs during hunts with turns and maneuvers, and the maximum speed recorded was sustained for 1–2 seconds. The speed was obtained by dividing the length by the time between footfalls of a stride.

Ecology and behaviour

Cheetahs are active mainly during the day, whereas other carnivores such as leopards and lions are active mainly at night; These larger carnivores can kill cheetahs and steal their kills; hence, the diurnal tendency of cheetahs helps them avoid larger predators in areas where they aresympatric

In biology, two related species or populations are considered sympatric when they exist in the same geographic area and thus frequently encounter one another. An initially interbreeding population that splits into two or more distinct species sh ...

, such as the Okavango Delta

The Okavango Delta (or Okavango Grassland; formerly spelled "Okovango" or "Okovanggo") in Botswana is a swampy inland delta formed where the Okavango River reaches a tectonic trough at an altitude of 930–1,000 m in the central part of the en ...

. In areas where the cheetah is the major predator (such as farmlands in Botswana and Namibia), activity tends to increase at night. This may also happen in highly arid regions such as the Sahara, where daytime temperatures can reach . The lunar cycle

Concerning the lunar month of ~29.53 days as viewed from Earth, the lunar phase or Moon phase is the shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion, which can be expressed quantitatively using areas or angles, or described qualitatively using the t ...

can also influence the cheetah's routine—activity might increase on moonlit nights as prey can be sighted easily, though this comes with the danger of encountering larger predators. Hunting is the major activity throughout the day, with peaks during dawn and dusk. Groups rest in grassy clearings after dusk. Cheetahs often inspect their vicinity at observation points such as elevations to check for prey or larger carnivores; even while resting, they take turns at keeping a lookout.

Social organisation

Cheetahs have a flexible and complexsocial structure

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals. Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally rel ...

and tend to be more gregarious than several other cats (except the lion). Individuals typically avoid one another but are generally amicable; males may fight over territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

or access to females in oestrus

The estrous cycle (, originally ) is the set of recurring physiological changes that are induced by reproductive hormones in most mammalian therian females. Estrous cycles start after sexual maturity in females and are interrupted by anestrous ...

, and on rare occasions such fights can result in severe injury and death. Females are not social and have minimal interaction with other individuals, barring the interaction with males when they enter their territories or during the mating season. Some females, generally mother and offspring or siblings, may rest beside one another during the day. Females tend to lead a solitary life or live with offspring in undefended home range

A home range is the area in which an animal lives and moves on a periodic basis. It is related to the concept of an animal's territory which is the area that is actively defended. The concept of a home range was introduced by W. H. Burt in 1943. He ...

s; young females often stay close to their mothers for life but young males leave their mother's range to live elsewhere.

Some males are territorial, and group together for life, forming coalitions that collectively defend a territory which ensures maximum access to females—this is unlike the behaviour of the male lion who mates with a particular group (pride) of females. In most cases, a coalition will consist of brothers born in the same litter who stayed together after weaning, but biologically unrelated males are often allowed into the group; in the Serengeti 30% members in coalitions are unrelated males. If a cub is the only male in a litter he will typically join an existing group, or form a small group of solitary males with two or three other lone males who may or may not be territorial. In the Kalahari Desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savanna in Southern Africa extending for , covering much of Botswana, and parts of Namibia and South Africa.

It is not to be confused with the Angolan, Namibian, and South African Namib coastal de ...

around 40% of the males live in solitude.

Males in a coalition are affectionate toward each other, grooming mutually and calling out if any member is lost; unrelated males may face some aversion in their initial days in the group. All males in the coalition typically have equal access to kills when the group hunts together, and possibly also to females who may enter their territory. A coalition generally has a greater chance of encountering and acquiring females for mating, however, its large membership demands greater resources than do solitary males. A 1987 study showed that solitary and grouped males have a nearly equal chance of coming across females, but the males in coalitions are notably healthier and have better chances of survival than their solitary counterparts.

Home ranges and territories

Unlike many other felids, among cheetahs, females tend to occupy larger areas compared to males. Females typically disperse over large areas in pursuit of prey, but they are less nomadic and roam in a smaller area if prey availability in the area is high. As such, the size of their home range depends on the distribution of prey in a region. In central Namibia, where most prey species are sparsely distributed, home ranges average , whereas in the woodlands of thePhinda Game Reserve

Phinda Private Game Reserve (), formerly known as Phinda Resource Reserve, is a private game reserve situated in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, between the Mkuze Game Reserve and the Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park. Designated in 1991, Phinda i ...

(South Africa), which have plentiful prey, home ranges are in size. Cheetahs can travel long stretches overland in search of food; a study in the Kalahari Desert recorded an average displacement of nearly every day and walking speeds ranged between .

Males are generally less nomadic than females; often males in coalitions (and sometimes solitary males staying far from coalitions) establish territories. Whether males settle in territories or disperse over large areas forming home ranges depends primarily on the movements of females. Territoriality is preferred only if females tend to be more sedentary, which is more feasible in areas with plenty of prey. Some males, called floaters, switch between territoriality and nomadism depending on the availability of females. A 1987 study showed territoriality depended on the size and age of males and the membership of the coalition. The ranges of floaters averaged in the Serengeti to in central Namibia. In the Kruger National Park

Kruger National Park is a South African National Park and one of the largest game reserves in Africa. It covers an area of in the provinces of Limpopo and Mpumalanga in northeastern South Africa, and extends from north to south and from ea ...

(South Africa) territories were much smaller. A coalition of three males occupied a territory measuring , and the territory of a solitary male measured . When a female enters a territory, the males will surround her; if she tries to escape, the males will bite or snap at her. Generally, the female can not escape on her own; the males themselves leave after they lose interest in her. They may smell the spot she was sitting or lying on to determine if she was in oestrus.

Communication

The cheetah is a vocal felid with a broad repertoire of calls and sounds; the acoustic features and the use of many of these have been studied in detail. The vocal characteristics, such as the way they are produced, are often different from those of other cats. For instance, a study showed that exhalation is louder than inhalation in cheetahs, while no such distinction was observed in thedomestic cat

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members o ...

. Listed below are some commonly recorded vocalisations observed in cheetahs:

* Chirping: A chirp (or a "stutter-bark") is an intense bird-like call and lasts less than a second. Cheetahs chirp when they are excited, for instance, when gathered around a kill. Other uses include summoning concealed or lost cubs by the mother, or as a greeting or courtship between adults. The cheetah's chirp is similar to the soft roar of the lion, and its churr as the latter's loud roar. A similar but louder call ('yelp') can be heard from up to away; this call is typically used by mothers to locate lost cubs, or by cubs to find their mothers and siblings.

* Churring (or churtling): A churr is a shrill, staccato call that can last up to two seconds. Churring and chirping have been noted for their similarity to the soft and loud roars of the lion. It is produced in similar context as chirping, but a study of feeding cheetahs found chirping to be much more common.

* Purring: Similar to purring in domestic cats but much louder, it is produced when the cheetah is content, and as a form of greeting or when licking one another. It involves continuous sound production alternating between egressive

In human speech, egressive sounds are sounds in which the air stream is created by pushing air out through the mouth or nose. The three types of egressive sounds are pulmonic egressive (from the lungs), glottalic egressive (from the glottis), a ...

and ingressive

In phonetics, ingressive sounds are sounds by which the airstream flows inward through the mouth or nose. The three types of ingressive sounds are lingual ingressive or velaric ingressive (from the tongue and the velum), glottalic ingressive (f ...

airstreams.

* Agonistic sounds: These include bleating, coughing, growling, hissing, meowing and moaning (or yowling). A bleat indicates distress, for instance when a cheetah confronts a predator that has stolen its kill. Growls, hisses and moans are accompanied by multiple, strong hits on the ground with the front paw, during which the cheetah may retreat by a few metres. A meow, though a versatile call, is typically associated with discomfort or irritation.

* Other vocalisations: Individuals can make a gurgling noise as part of a close, amicable interaction. A "nyam nyam" sound may be produced while eating. Apart from chirping, mothers can use a repeated "ihn ihn" is to gather cubs, and a "prr prr" is to guide them on a journey. A low-pitched alarm call is used to warn the cubs to stand still. Bickering cubs can let out a "whirr"—the pitch rises with the intensity of the quarrel and ends on a harsh note.

Another major means of communication is by scent

An odor (American English) or odour (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences) is caused by one or more volatilized chemical compounds that are generally found in low concentrations that humans and animals can perceive via their sense ...

—the male will often investigate urine-marked places (territories or common landmarks) for a long time by crouching on his forelegs and carefully smelling the place. Then he will raise his tail and urinate on an elevated spot (such as a tree trunk, stump or rock); other observing individuals might repeat the ritual. Females may also show marking behaviour but less prominently than males do. Among females, those in oestrus will show maximum urine-marking, and their excrement can attract males from far off. In Botswana, cheetahs are frequently captured by ranchers to protect livestock by setting up traps in traditional marking spots; the calls of the trapped cheetah can attract more cheetahs to the place.

Touch and visual cues are other ways of signalling in cheetahs. Social meetings involve mutual sniffing of the mouth, anus and genitals. Individuals will groom one another, lick each other's faces and rub cheeks. However, they seldom lean on or rub their flanks against each other. The tear streaks on the face can sharply define expressions at close range. Mothers probably use the alternate light and dark rings on the tail to signal their cubs to follow them.

Diet and hunting

The cheetah is a carnivore that hunts small to medium-sized prey weighing , but mostly less than . Its primary prey are medium-sized ungulates. They are the major component of the diet in certain areas, such as Dama andDorcas

Dorcas ( el, Δορκάς, Dorkás, used as a translated variant of the Aramaic name), or Tabitha ( arc, טביתא/ܛܒܝܬܐ, Ṭaḇīṯā, (female) gazelle), was an early disciple of Jesus mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles (, see discussi ...

gazelles in the Sahara, impala

The impala or rooibok (''Aepyceros melampus'') is a medium-sized antelope found in eastern and southern Africa. The only extant member of the genus '' Aepyceros'' and tribe Aepycerotini, it was first described to European audiences by Germa ...

in the eastern and southern African woodlands, springbok in the arid savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

s to the south and Thomson's gazelle

Thomson's gazelle (''Eudorcas thomsonii'') is one of the best known species of gazelles. It is named after explorer Joseph Thomson and is sometimes referred to as a "tommie". It is considered by some to be a subspecies of the red-fronted gazelle a ...

in the Serengeti. Smaller antelopes like the common duiker

The common duiker (''Sylvicapra grimmia''), also known as the grey or bush duiker, is a small antelope and the only member of the genus ''Sylvicapra''. This species is found everywhere in Africa south of the Sahara, excluding the Horn of Africa ...

are a frequent prey in the southern Kalahari. Larger ungulates are typically avoided, though nyala

The lowland nyala or simply nyala (''Tragelaphus angasii'') is a spiral-horned antelope native to southern Africa. It is a species of the family Bovidae and genus ''Tragelaphus'', previously placed in genus ''Nyala''. It was first described in ...

, whose males weigh around , were found to be the major prey in a study in the Phinda Game Reserve. In Namibia cheetahs are the major predators of livestock. The diet of the Asiatic cheetah consists of chinkara

The chinkara (''Gazella bennettii''), also known as the Indian gazelle, is a gazelle species native to Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Taxonomy

The following six subspecies are considered valid:

* Deccan chinkara (''G. b. bennettii'') ...

, desert hare

The desert hare (''Lepus tibetanus'') is a species of hare found in Central Asia, Northwest China, and the western Indian subcontinent. Little is known about this species except that it inhabits grassland and scrub areas of desert and semi-desert ...

, goitered gazelle, urial

The urial ( ; ''Ovis vignei''), also known as the arkars or shapo, is a wild sheep native to Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.

Characteristics

Urial males have large horns, curling outwards from the to ...

, wild goat

The wild goat (''Capra aegagrus'') is a wild goat species, inhabiting forests, shrublands and rocky areas ranging from Turkey and the Caucasus in the west to Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan in the east. It has been listed as near threatene ...

s and livestock; in India cheetahs used to prey mostly on blackbuck

The blackbuck (''Antilope cervicapra''), also known as the Indian antelope, is an antelope native to India and Nepal. It inhabits grassy plains and lightly forested areas with perennial water sources.

It stands up to high at the shoulder. Mal ...

. There are no records of cheetahs killing humans. Cheetahs in the Kalahari have been reported feeding on citron melon

The citron melon (''Citrullus caffer''), also called ''Citrullus lanatus'' var. ''citroides'' and ''Citrullus amarus'', fodder melon, preserving melon, red-seeded citron, jam melon, stock melon, Kalahari melon or tsamma melon, is a relative of t ...

s for their water content.

Prey preferences and hunting success vary with the age, sex and number of cheetahs involved in the hunt and on the vigilance of the prey. Generally only groups of cheetahs (coalitions or mother and cubs) will try to kill larger prey; mothers with cubs especially look out for larger prey and tend to be more successful than females without cubs. Individuals on the periphery of the prey herd are common targets; vigilant prey which would react quickly on seeing the cheetah are not preferred.

Cheetahs hunt primarily throughout the day, sometimes with peaks at dawn

Dawn is the time that marks the beginning of twilight before sunrise. It is recognized by the appearance of indirect sunlight being scattered in Earth's atmosphere, when the centre of the Sun's disc has reached 18° below the observer's horizo ...

and dusk

Dusk occurs at the darkest stage of twilight, or at the very end of astronomical twilight after sunset and just before nightfall.''The Random House College Dictionary'', "dusk". At predusk, during early to intermediate stages of twilight, enou ...

; they tend to avoid larger predators like the primarily nocturnal lion. Cheetahs in the Sahara and Maasai Mara

Maasai Mara, also sometimes spelled Masai Mara and locally known simply as The Mara, is a large national game reserve in Narok, Kenya, contiguous with the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. It is named in honor of the Maasai people, the ancestr ...

in Kenya hunt after sunset to escape the high temperatures of the day. Cheetahs use their vision

Vision, Visions, or The Vision may refer to:

Perception Optical perception

* Visual perception, the sense of sight

* Visual system, the physical mechanism of eyesight

* Computer vision, a field dealing with how computers can be made to gain un ...

to hunt instead of their sense of smell; they keep a lookout for prey from resting sites or low branches. The cheetah will stalk its prey, trying to conceal itself in cover, and approach as close as possible, often within of the prey (or even farther for less alert prey). Alternatively the cheetah can lie hidden in cover and wait for the prey to come nearer. A stalking cheetah assumes a partially crouched posture, with the head lower than the shoulders; it will move slowly and be still at times. In areas of minimal cover the cheetah will approach within of the prey and start the chase. The chase typically lasts a minute; in a 2013 study, the length of chases averaged , and the longest run measured . The cheetah can give up the chase if it is detected by the prey early or if it can not make a kill quickly. Cheetahs catch their prey by tripping it during the chase by hitting its rump with the forepaw or using the strong dewclaw to knock the prey off its balance, bringing it down with much force and sometimes even breaking some of its limbs.

Cheetahs can decelerate dramatically towards the end of the hunt, slowing down from to in just three strides, and can easily follow any twists and turns the prey makes as it tries to flee. To kill medium- to large-sized prey, the cheetah bites the prey's throat to suffocate it, maintaining the bite for around five minutes, within which the prey stops struggling. A bite on the nape of the neck or the snout (and sometimes on the skull) suffices to kill smaller prey. Cheetahs have an average hunting success rate of 25–40%, higher for smaller and more vulnerable prey.

Once the hunt is over, the prey is taken near a bush or under a tree; the cheetah, highly exhausted after the chase, rests beside the kill and pants heavily for five to 55 minutes. Meanwhile, cheetahs nearby, who did not take part in the hunt, might feed on the kill immediately. Groups of cheetah devour the kill peacefully, though minor noises and snapping may be observed. Cheetahs can consume large quantities of food; a cheetah at the Etosha National Park

Etosha National Park is a national park in northwestern Namibia and one of the largest national parks in Africa. It was proclaimed a game reserve in March 1907 in Ordinance 88 by the Governor of German South West Africa, Friedrich von Lindequist. ...

(Namibia) was found to consume as much as within two hours. However, on a daily basis, a cheetah feeds on around meat. Cheetahs, especially mothers with cubs, remain cautious even as they eat, pausing to look around for fresh prey or for predators who may steal the kill.

Cheetahs move their heads from side to side so the sharp carnassial teeth tear the flesh, which can then be swallowed without chewing. They typically begin with the hindquarters, and then progress toward the abdomen and the spine. Ribs are chewed on at the ends, and the limbs are not generally torn apart while eating. Unless the prey is very small, the skeleton is left almost intact after feeding on the meat. Cheetahs might lose 10–15% of their kills to large carnivores such as hyenas and lions (and grey wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly u ...