Charles Kennedy Scott on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

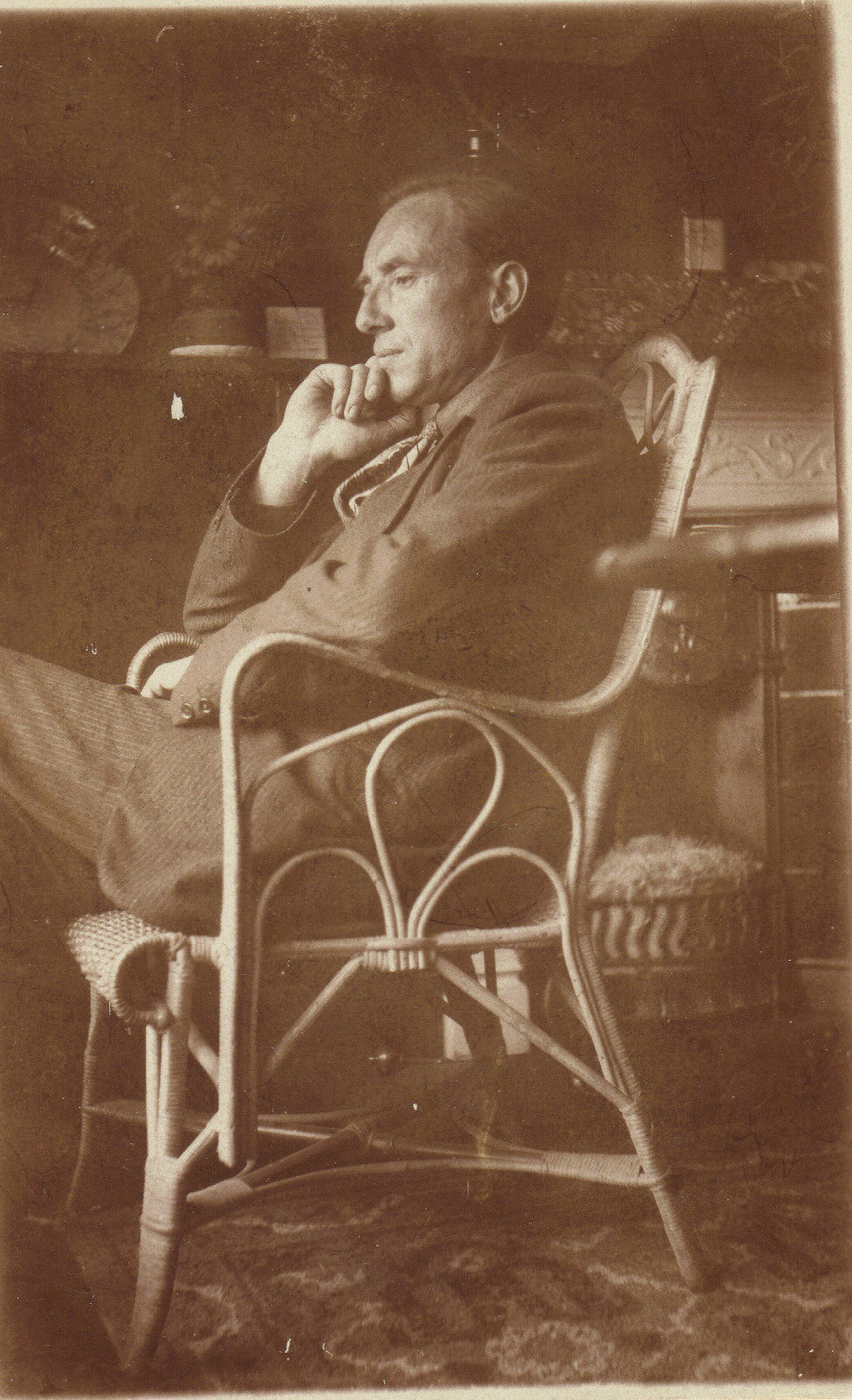

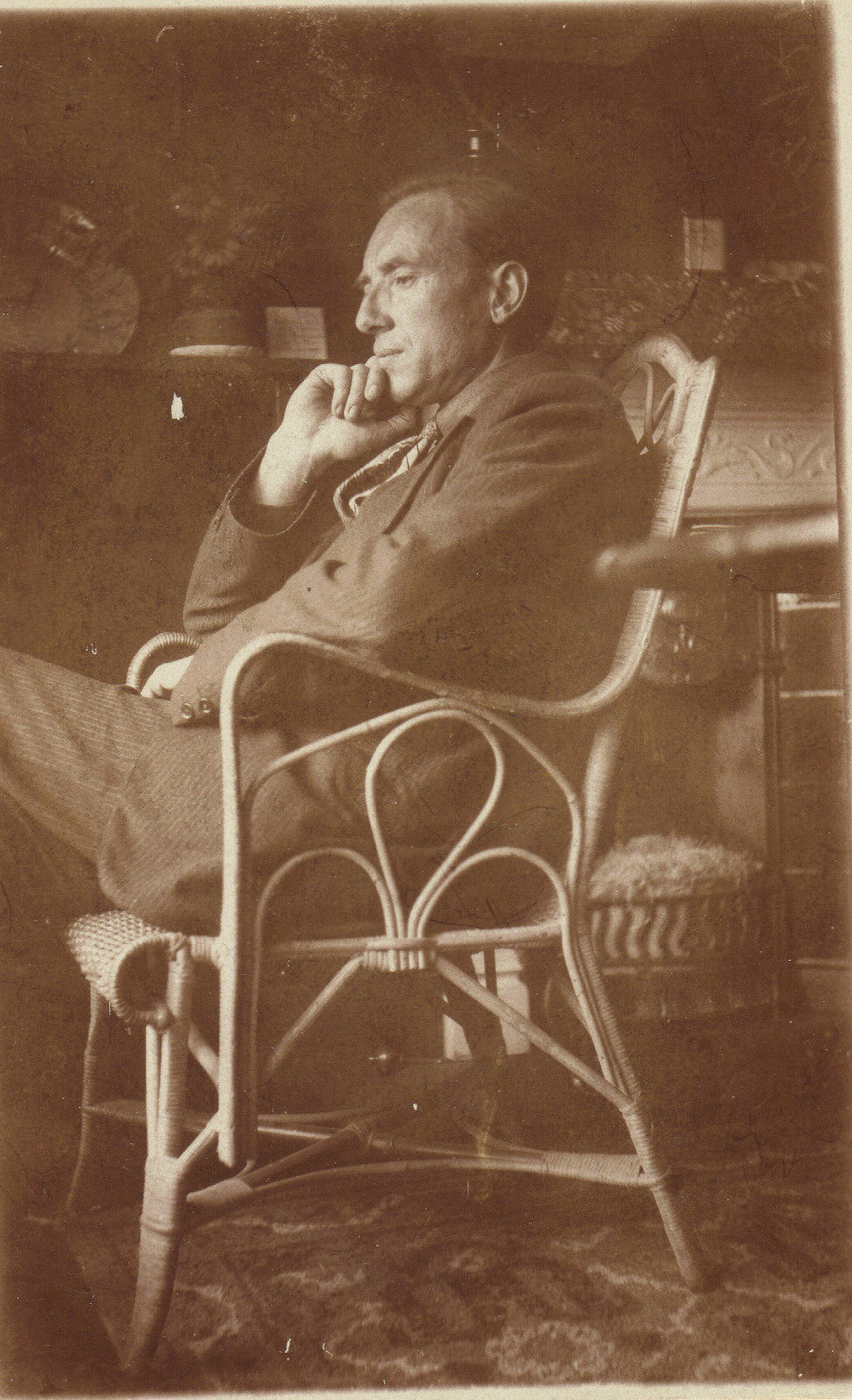

Charles James Kennedy Osborne Scott (16 November 18762 July 1965) was an English organist and choral conductor who played an important part in developing the performance of choral and polyphonic music in England, especially of early and modern English music.

The Oriana Choir brought high standards of precision and flexibility to choral performance, which had a beneficial influence on choral music in general. Their work naturally drew Scott towards the contemporary English scene, and he came to know

The Oriana Choir brought high standards of precision and flexibility to choral performance, which had a beneficial influence on choral music in general. Their work naturally drew Scott towards the contemporary English scene, and he came to know

In October 1919 Scott founded the Philharmonic Choir, the predecessor of the present

In October 1919 Scott founded the Philharmonic Choir, the predecessor of the present  They gave many performances of the great standard works such as the Mass in B minor, the ''

They gave many performances of the great standard works such as the Mass in B minor, the ''

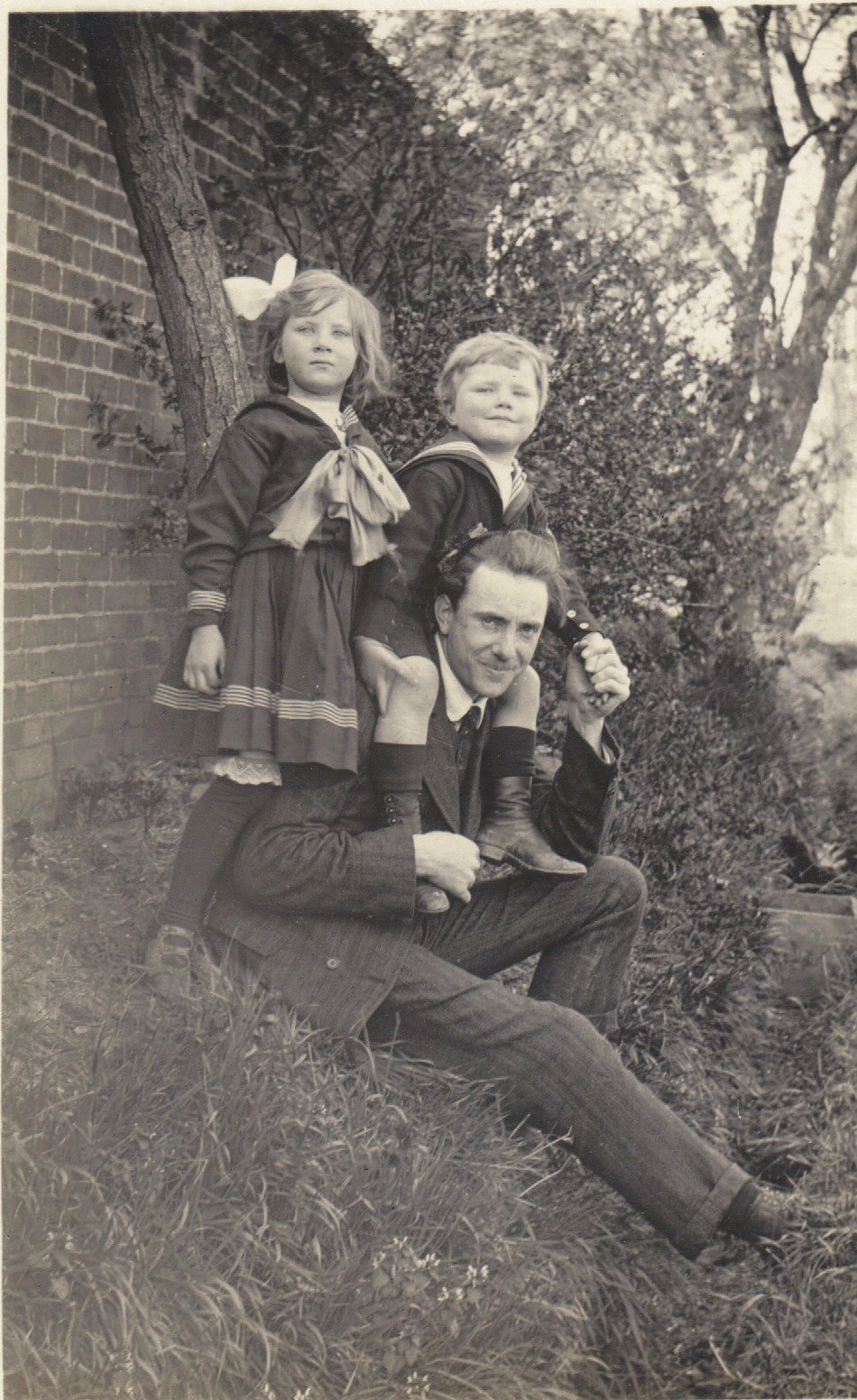

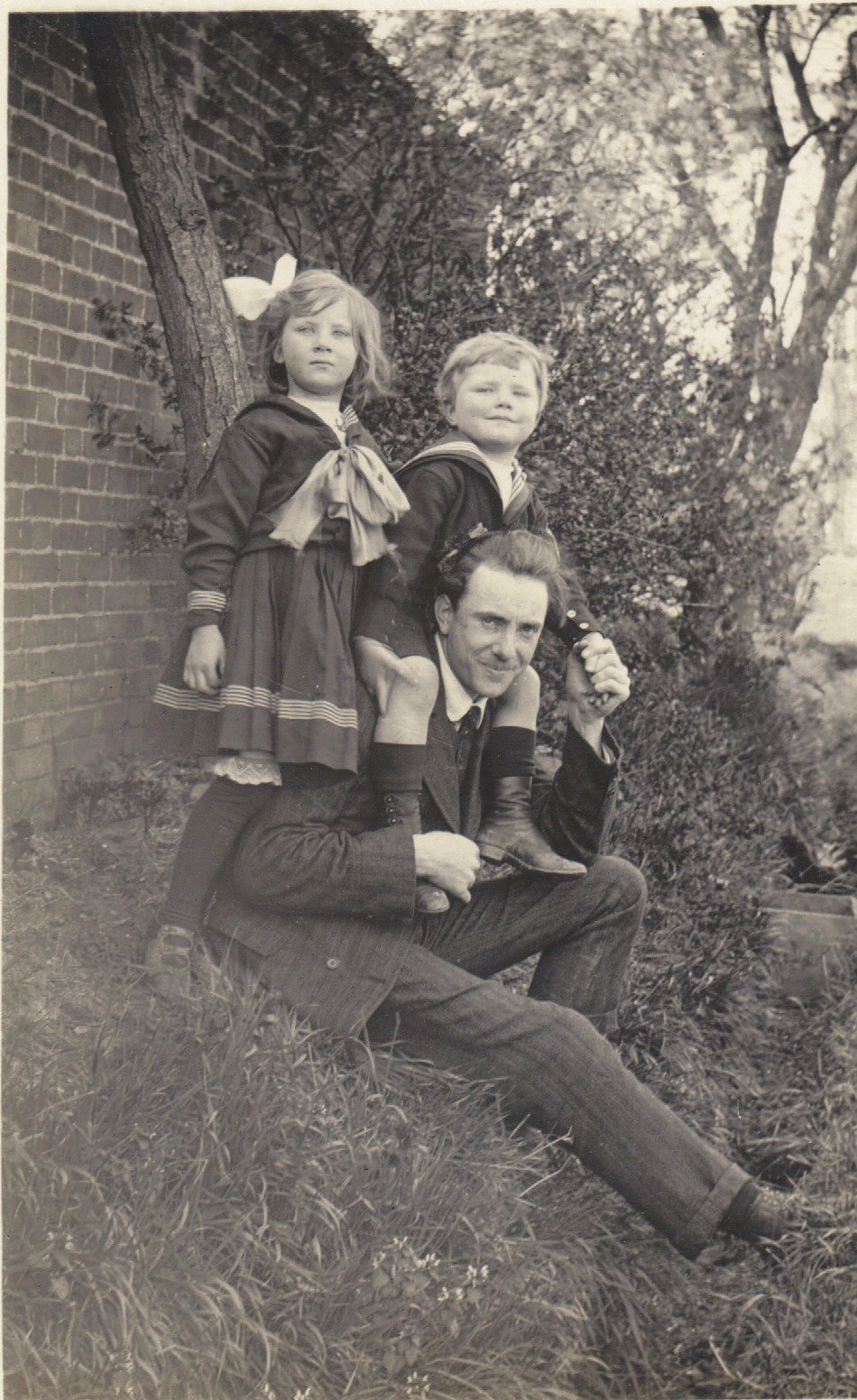

Charles Kennedy Scott and his wife Mary (née Donaldson) were the parents of the aviator

Charles Kennedy Scott and his wife Mary (née Donaldson) were the parents of the aviator

Early career

Scott was born in Romsey. Educated atSouthampton Grammar School

King Edward VI School (also known as King Edward's, or KES) is a selective co-educational independent school founded in Southampton, United Kingdom, in 1553.

The school was founded at the request of William Capon, who bequeathed money in hi ...

, he entered the Brussels Conservatory in 1894. Beginning by studying the violin, he transferred to the organ under the outstanding virtuoso and teacher Alphonse Mailly Alphonse may refer to:

* Alphonse (given name)

* Alphonse (surname)

* Alphonse Atoll, one of two atolls in the Seychelles' Alphonse Group

See also

*Alphons

*Alfonso (disambiguation) Alfonso (and variants Alphonso, Afonso, Alphons, and Alphonse) i ...

(1833–1918), who encouraged a special interest in plainchant and in the phrasing of Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

's organ music: he also studied composition under Hubert Ferdinand Kufferath (1818–1896) (a pupil of Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositi ...

's), teacher of counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

and fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

, and under the organist-composer Edgar Tinel

Edgar Pierre Joseph Tinel (27 March 185428 October 1912) was a Belgian composer and pianist.

He was born in Sinaai, today part of Sint-Niklaas in East Flanders, Belgium, and died in Brussels. After studies at the Brussels Conservatory with Lou ...

(1854–1912). In 1897 he took the ''Premier Prix avec distinction'' and the ''Mailly Prize'' for organ playing.

He settled in London in 1898 as a professional organist and teacher, and married a second cousin who had also studied at Brussels.

Oriana Choir

In 1904 Scott founded the Oriana Madrigal Society, consisting of 36 voices, which made its first public appearance at the Portman Rooms in July 1905. Its initially stated object was 'to press the claims of ourElizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

school', and 'to devote itself solely to the singing of English madrigals.' Scott was by chance shown the publications of the Musical Antiquarian Society The Musical Antiquarian Society was a British society established in 1840. It published, during seven years, 19 volumes of choral music from the 16th and 17th centuries.

History

The society was established in 1840 "for the publication of scarce and ...

, including a volume of madrigals by John Wilbye

John Wilbye (baptized 7 March 1574September 1638) was an English madrigal composer.

Early life and education

The son of a tanner, he was born at Brome, Suffolk, England. (Brome is near Diss.)

Career

Wilbye received the patronage of the Cornwa ...

, and formed the determination to lift English Elizabethan music from its position of comparative neglect. He scored many examples over the next years and held gatherings which became the core of his society. Later on the number of voices was increased to 60, and its work was extended to include modern compositions, both English and foreign, but always with emphasis on the English.

The Oriana Choir brought high standards of precision and flexibility to choral performance, which had a beneficial influence on choral music in general. Their work naturally drew Scott towards the contemporary English scene, and he came to know

The Oriana Choir brought high standards of precision and flexibility to choral performance, which had a beneficial influence on choral music in general. Their work naturally drew Scott towards the contemporary English scene, and he came to know H. Balfour Gardiner

Henry Balfour Gardiner (7 November 1877 – 28 June 1950) was a British musician, composer, and teacher.

He was born at Kensington (London), began to play at the age of 5 and to compose at 9. Between his conventional education at Charterhouse ...

and Arnold Bax

Sir Arnold Edward Trevor Bax, (8 November 1883 – 3 October 1953) was an English composer, poet, and author. His prolific output includes songs, choral music, chamber pieces, and solo piano works, but he is best known for his orchestral musi ...

, and through them Norman O'Neill

Norman Houston O'Neill (14 March 1875 – 3 March 1934) was an English composer and conductor of Irish background who specialised largely in works for the theatre.

Life

O'Neill was born at 16 Young Street in Kensington, London, the youngest so ...

, Frederick Delius

Delius, photographed in 1907

Frederick Theodore Albert Delius ( 29 January 1862 – 10 June 1934), originally Fritz Delius, was an English composer. Born in Bradford in the north of England to a prosperous mercantile family, he resisted atte ...

, Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

, Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long an ...

, Benjamin Dale

Benjamin James Dale (17 July 188530 July 1943) was an English composer and academic who had a long association with the Royal Academy of Music. Dale showed compositional talent from an early age and went on to write a small but notable corpus of ...

, Roger Quilter

Roger Cuthbert Quilter (1 November 1877 – 21 September 1953) was a British composer, known particularly for his art songs. His songs, which number over a hundred, often set music to text by William Shakespeare and are a mainstay of the En ...

and others.

Thus the Oriana gave madrigal concerts in the two series devoted to English contemporary music, of 1912 and 1913, promoted by Gardiner, and in the Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a membe ...

concert of 20 November 1913, under Scott and Balfour Gardiner, which also included part-songs by Charles Villiers Stanford

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (30 September 1852 – 29 March 1924) was an Anglo-Irish composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Romantic music, Romantic era. Born to a well-off and highly musical family in Dublin, Stanford was ed ...

, Gardiner and Hubert Parry

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, 1st Baronet (27 February 18487 October 1918) was an English composer, teacher and historian of music. Born in Richmond Hill in Bournemouth, Parry's first major works appeared in 1880. As a composer he is b ...

. In 1920 they gave the first hearing of Delius's unaccompanied choruses '' To be Sung of a Summer Night on the Water''. In 1922 they sang in a special concert of the works of Arnold Bax, with the Goossens Orchestra, giving the first performance of his motet for double choir '' Mater ora filium'', a work dedicated to Charles Kennedy Scott.

In 1926 and 1927 the Oriana joined with the Bach Cantata Club for performances of Bach's Mass in B minor

The Mass in B minor (), BWV 232, is an extended setting of the Mass ordinary by Johann Sebastian Bach. The composition was completed in 1749, the year before the composer's death, and was to a large extent based on earlier work, such as a Sanctu ...

: in 1931 they sang works by Bax, Peter Warlock

Philip Arnold Heseltine (30 October 189417 December 1930), known by the pseudonym Peter Warlock, was a British composer and music critic. The Warlock name, which reflects Heseltine's interest in occultism, occult practices, was used for all his ...

and Holst at a Festival for the International Society of Contemporary Music, and in 1936 they formed the core of a 100-voice chorus for the first London performance of Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Urbain Fauré (; 12 May 1845 – 4 November 1924) was a French composer, organist, pianist and teacher. He was one of the foremost French composers of his generation, and his musical style influenced many 20th-century composers ...

's ''Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

'', and for Heinrich Schütz

Heinrich Schütz (; 6 November 1672) was a German early Baroque composer and organist, generally regarded as the most important German composer before Johann Sebastian Bach, as well as one of the most important composers of the 17th century. He ...

's ''History of the Resurrection'' under Nadia Boulanger

Juliette Nadia Boulanger (; 16 September 188722 October 1979) was a French music teacher and conductor. She taught many of the leading composers and musicians of the 20th century, and also performed occasionally as a pianist and organist.

From a ...

. All of these performances were given at the Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. From 1895 until 1941, it ...

, but latterly most Oriana concerts were at the Aeolian Hall, usually three times yearly, and often in collaboration with the English Folk Dance Society.

Recordings

*Delius, arr. Percy Grainger: ''Brigg Fair

Brigg Fair is a traditional English folk song sung by the Lincolnshire singer Joseph Taylor. The song, which is named after a historical fair in Brigg, Lincolnshire, was collected and recorded on wax cylinder by the composer and folk song colle ...

'': Norman Stone (tenor), Oriana Madrigal Society directed by Charles Kennedy Scott (Dutton CD AX 8006)

Philharmonic Choir

In October 1919 Scott founded the Philharmonic Choir, the predecessor of the present

In October 1919 Scott founded the Philharmonic Choir, the predecessor of the present London Philharmonic Choir

The London Philharmonic Choir (LPC) is one of the leading independent British choirs in the United Kingdom based in London. The patron is Princess Alexandra, The Hon Lady Ogilvy and Sir Mark Elder is president. The choir, comprising more than ...

. This first appeared at a Philharmonic Society concert in February 1920, to give the first performance of Delius

Delius, photographed in 1907

Frederick Theodore Albert Delius ( 29 January 1862 – 10 June 1934), originally Fritz Delius, was an English composer. Born in Bradford in the north of England to a prosperous mercantile family, he resisted atte ...

's '' A Song of the High Hills'', and also Bach's ''Sing Ye to the Lord'' and Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

's 9th Symphony (directed by Scott, under Albert Coates). Most of its concerts took place in the Queen's Hall, where the space available limited the membership to about 300. The choir contained a large professional element, especially among the tenors, to achieve a high standard of performance: the costs of their employment were met principally by Balfour Gardiner.

The Choir gave two or three concerts of its own each season under its own conductor, but also made very numerous appearances with the Royal Philharmonic Society, the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

, the BBC, and the Courtauld-Sargent Concerts (established 1929). On 25 March 1920 they gave the first performance of Holst's ''The Hymn of Jesus

''The Hymn of Jesus'', H. 140, Op. 37, is a sacred work by Gustav Holst scored for two choruses, semi-chorus, and full orchestra. It was written in 1917–1919 and first performed in 1920. One of his most popular and highly acclaimed composit ...

'', the composer conducting: they went on to introduce many modern works to London, including Delius's ''Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

'' and ''Songs of Farewell

''Songs of Farewell'' is a set of six choral motets by the British composer Hubert Parry. The pieces were composed between 1916 and 1918 and were among his last compositions before his death.

Background

The songs were written during the First ...

'', César Franck

César-Auguste Jean-Guillaume Hubert Franck (; 10 December 1822 – 8 November 1890) was a French Romantic composer, pianist, organist, and music teacher born in modern-day Belgium.

He was born in Liège (which at the time of his birth was p ...

's ''Psyche'': ''St Patrick's Breastplate'', ''Walsinghame'' and ''This Worldes Joie'' by Bax; ''Requiem Mass'' by Sir George Henschel

Sir Isidor George Henschel (18 February 185010 September 1934) was a German-born British baritone, pianist, conductor, and composer. His first wife Lillian was also a singer. He was the first conductor of both the Boston Symphony Orchestra ...

; ''April'' by Balfour Gardiner; ''Psalmus Hungaricus

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived f ...

'' of Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály (; hu, Kodály Zoltán, ; 16 December 1882 – 6 March 1967) was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is well known internationally as the creator of the Kodály method of music ed ...

; ''San Francesco d'Assisi'' of Malipiero; ''The Prison'' by Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended t ...

; ''The Canterbury Pilgrims'' and ''In Honour of the City'' by George Dyson; ''Ode on a Grecian Urn'' by Philip Napier Miles

Philip Napier Miles JP DLitt ''h.c.'' (Bristol) (21 January 1865 – 19 July 1935) was a prominent and wealthy citizen of Bristol, UK, who left his mark on the city, especially on what are now its western suburbs, through his musical and organis ...

; ''Magnificat'' and ''Flourish for a Coronation'' by Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams, (; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

; Constant Lambert

Leonard Constant Lambert (23 August 190521 August 1951) was a British composer, conductor, and author. He was the founder and music director of the Royal Ballet, and (alongside Ninette de Valois and Frederick Ashton) he was a major figure in th ...

's ''Summer's Last Will and Testament'', Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

's ''Oedipus Rex

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' ( grc, Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Gr ...

'', Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

's '' The Bells'' and Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ''Ne ...

's ''Mathis der Maler

''Mathis der Maler'' (''Matthias the Painter'' is an opera by Paul Hindemith. The work's protagonist, Matthias Grünewald, was a historical figure who flourished during the Reformation, and whose art, in particular the Isenheim Altarpiece, inspi ...

''.

The choir was suspended in 1939 at the outbreak of World War II: when the London Philharmonic Choir was formed in 1946 Scott was unable to resume direction, and a new conductor was appointed.

The choir played a major part with the London Symphony Orchestra in Sir Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (29 April 18798 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, London Philharmonic and the Roya ...

's 'revitalisation' of George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

's ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

'' in December 1926, and undertook much of the choral work in the Delius Festival of 1929. They gave many performances of the great standard works such as the Mass in B minor, the ''

They gave many performances of the great standard works such as the Mass in B minor, the ''St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (german: Matthäus-Passion, links=-no), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets ...

'' and ''St John Passion

The ''Passio secundum Joannem'' or ''St John Passion'' (german: Johannes-Passion, link=no), BWV 245, is a Passion or oratorio by Johann Sebastian Bach, the older of the surviving Passions by Bach. It was written during his first year as direc ...

'', the ''Christmas Oratorio

The ''Christmas Oratorio'' (German: ''Weihnachtsoratorium''), , is an oratorio by Johann Sebastian Bach intended for performance in church during the Christmas season. It is in six parts, each part a cantata intended for performance on one of t ...

'', the ''Requiems'' of Mozart and Brahms, and many of the Handel oratorios. As an offshoot of the Philharmonic Choir appeared the Junior Philharmonic Choir, consisting of two to three hundred girls and young men from the London Secondary Schools' Festival, who gave several concerts from 1932 onwards in major religious works by Bach.

Recordings

*Mozart: Requiem Mass, K 626 (abridged version): Requiem aeternam, Kyrie, Dies Irae, Domine Jesu Christe, Hostias, Agnus Dei, Lux aeterna, Cum sanctis tuis. Soloists, Philharmonic Chorus and Orchestra, directed by C. Kennedy Scott, 6 July 1926, Queen's Hall (3 12" 78rpm, HMV D 1147–49: others unpublished). *Schubert: Mass in G major: Kyrie eleison, Gloria in Excelsis, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus, Agnus Dei. Elsie Suddaby, soprano; Howard Fry, baritone; Percy Manchester, tenor; Philharmonic Choir; London Symphony Orchestra; directed by Charles Kennedy Scott, 2 & 3 July 1928 (3 12" 78rpm, HMV D 1478–80).A Cappella Singers

Scott created the A Cappella Singers as a small group of 14 professional singers, for singing madrigals and part-songs under chamber-music conditions rather than in the concert hall. It was first assembled in 1922, and gave most of its performances in private houses or for music clubs, though occasionally singing at Queen's Hall in company with other Kennedy Scott choirs.

Involvement in opera

In 1914, at the Glastonbury Festival, Scott conducted the first performance ofRutland Boughton

Rutland Boughton (23 January 187825 January 1960) was an English composer who became well known in the early 20th century as a composer of opera and choral music. He was also an influential communist activist within the Communist Party of Gre ...

's opera ''The Immortal Hour

''The Immortal Hour'' is an opera by English composer Rutland Boughton. Boughton adapted his own libretto from the play of the same name by Fiona MacLeod, a pseudonym of writer William Sharp.

''The Immortal Hour'' is a fairy tale or fairy op ...

''.

Recordings

*Purcell: Dido and Aeneas (first complete): Nancy Evans (Dido), Mary Hamlin (Belinda), Roy Henderson (Aeneas),Mary Jarred

Mary Jarred (9 October 189912 December 1993) was an English opera singer of the mid-twentieth century. She is sometimes classed as a mezzo-soprano and sometimes as a contralto.

Biography

Jarred was born in Brotton, Yorkshire, (now in Redcar and ...

(Sorceress), Olive Dyer (Spirit), Dr Sydney Northcote (Sailor), Gladys Currie (Second woman), Gwen Catley

Gwendoline Florence Catley (9 February 190612 November 1996) was an English lyric coloratura soprano who sang in opera, concert and revues. She often sang on radio and television, and made numerous recordings of songs and arias, mostly in Englis ...

and Gladys Currie (Witches), Charles Kennedy Scott's A Cappella Singers, Boyd Neel

Louis Boyd Neel O.C. (19 July 190530 September 1981) was an English, and later Canadian conductor and academic. He was Dean of the Royal Conservatory of Music at the University of Toronto. Neel founded and conducted chamber orchestras, and cont ...

String Orchestra, Boris Ord

Boris Ord (born Bernhard Ord), (9 July 1897 – 30 December 1961) was a British organist and Director of music, choirmaster of Choir of King's College, Cambridge, King's College, Cambridge (1929-1957). During World War II he served in the Royal ...

(continuo), Clarence Raybould

Robert Clarence Raybould (28 June 1886 – 27 March 1972) was an English conductor, pianist and composer who conducted works ranging from musical comedy and operetta, Gilbert and Sullivan to the standard classical repertoire. He also cham ...

(conductor), Hubert J. Foss (Musical director). (Decca Records

Decca Records is a British record label established in 1929 by Edward Lewis (Decca), Edward Lewis. Its U.S. label was established in late 1934 by Lewis, Jack Kapp, American Decca's first president, and Milton Rackmil, who later became American ...

, X 101–107, 7 12" 78rpm records, by subscription only for the Purcell Society).

Also in 1922 Scott founded the Euterpe String Players.

The Bach Cantata Club

The Bach Cantata Club was formed in 1926, with the aim of making known the church and secularcantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning of ...

s of J. S. Bach and his instrumental works, performed with resources similar to those which Bach himself must have planned for when he was composing. In this project Scott was joined by Hubert J. Foss

Hubert James Foss (2 May 1899 – 27 May 1953) was an English pianist, composer, and first Musical Editor (1923–1941) for Oxford University Press (OUP) at Amen House in London. His work at the Press was a major factor in promoting music and ...

and E. Stanley Roper (organist of the Chapel Royal), and they received assistance from the Bach musicologist Dr Charles Sanford Terry Charles Sanford Terry may refer to:

* Charles Sanford Terry (historian) (1864-1936), English historian and authority on Johann Sebastian Bach

* Charles Sanford Terry (translator) (1926–1982), American translator of Japanese literature

(who contributed programme notes, and gave a lecture on Bach's Chorales and Chorale Preludes in 1927) and from Dr W. G. Whittaker, director of the Newcastle Bach Choir (on which the London Club was partly modelled). The Vice-President was Dr Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian-German/French polymath. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran minister, Schwei ...

, who from time to time acted as organist at the Society's concerts. The choir of the Club consisted of twenty-five singers, mostly professional, while the instrumental work was an ensemble of London players called the Bach Chamber Orchestra. The choral concerts mostly took place at St. Margaret's, Westminster, and the orchestral performances at the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a music school, conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the Undergraduate education, undergraduate to the Doctorate, doctoral level in a ...

. A command performance of the unaccompanied motets was given before the king and queen at Buckingham Palace in 1927, and the Motet 'Jesu Joy and Treasure' was recorded for HMV in the same year.

On 27 November 1929, at the Annual Extra Meeting, a bicentennial performance of the ''St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (german: Matthäus-Passion, links=-no), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets ...

'', in English, using Dr Troutbeck's version and rejecting the Elgar-Atkin treatment, was given at Westminster with a 90-minute interval for dinner. The following resources were employed:

*Bruce Flegg (Narrator); Keith Falkner (Jesus); Elsie Suddaby

Elsie Suddaby (1893 - 1980) was a British lyric soprano during the years between World War I and World War II. She was born in Leeds, a first cousin once removed to the organist and composer, Francis Jackson.

A pupil of Sir Edward Bairstow, she ...

, Margaret Balfour, Archibald Winter, Arthur Cranmer.

*Recitatives by Elsie Warner (Pilate's wife), Helen Tresillian, Ethel Robinson (Damsels), Mary Morris, Herbert Parsons (False witnesses), Wesley Dennison (High Priest), Arthur Cranmer (Peter), Walter Millard (Pilate), Leonard Rogers (Judas).

*Obbligati by Joseph Slater (flute), Leon Goossens

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again f ...

and James McDonagh (oboes), William Primrose

William Primrose CBE (23 August 19041 May 1982) was a Scottish violist and teacher. He performed with the London String Quartet from 1930 to 1935. He then joined the NBC Symphony Orchestra where he formed the Primrose Quartet. He performed in ...

(violin), Ivor James

Ivor James CBE (1882–1963) Percy A. Scholes. "James, Ivor". ''Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music''. Oxford University Press, 1964. was a British cellist. He taught for many years at the Royal College of Music; among his pupils were those who bec ...

(cello).

*Bach Cantata Choir: Two choirs, each with eight sopranos, four contraltos, three tenors and four basses (the numbers made up with the assistance of members of the Oriana and Philharmonic Choirs). Also The Boys of St Margaret's.

*Bach Chamber Orchestra: Two orchestras, each with two first violins, two second violins, two violas, two cellos, one double bass, two flutes, and two oboes (alternating with oboi d'amore and cor anglais in the first orchestra). (Leader: William Primrose).

*Organ (Herbert Dawson); Harpsichord (Frederic Jackson); Conductor (Charles Kennedy Scott).

For the grand event of 1930 the Christmas Oratorio

The ''Christmas Oratorio'' (German: ''Weihnachtsoratorium''), , is an oratorio by Johann Sebastian Bach intended for performance in church during the Christmas season. It is in six parts, each part a cantata intended for performance on one of t ...

was given complete with Dorothy Silk, Margaret Balfour, Henry Wendon and Keith Falkner.

By this date the Club had held 22 meetings including three performances of the ''Mass in B Minor'' (one in St Margaret's Church and one in Queen's Hall), twenty-five Church Cantatas, four Motets, three secular Cantatas, and various composite programmes and instrumental works. The subscription rate was 24 shillings (£1.4s.0d., i.e. £1.20p sterling) for a single seat to five concerts, £2.2s.0d. (two guineas) for a double ticket and £3 for a treble. Single Guest Tickets were 5s.9d. per concert.

Recordings

*Bach: Jesus, Joy and Treasure (Jesu meine Freude) motet, Bach Cantata Club conducted by Charles Kennedy Scott, 1927 (2 78rpm HMV D 1256–57). *Columbia History of Music, Volume II – to the death of Bach and Handel: **(Bach Cantata Club Choir) Rejoice in the Lord alway; Handel: May no rash intruder (''Solomon''); Bach: ''Vater unser in Himmelreich'' and ''Herzlich thut mich verlangen''; ''Jesu Joy of Man's Desiring''. **(Strings of Bach Cantata Club) Like as the love-lorn turtle (with Doris Owens); Bach: E major violin concerto (with Yovanovitch Bratza); Sinfonia to Church Cantata 156 (withLeon Goossens

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again f ...

); Rondeau and Badinerie from Suite in B minor for flute (with Robert Murchie).

There was a plan to amalgamate all four of the Kennedy choirs in 1939 for a series of 9 concerts illustrating a survey of choral music, but this was abandoned owing to the war.

Later life

Scott was a member of staff ofTrinity College of Music

Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance is a music and dance conservatoire based in London, England. It was formed in 2005 as a merger of two older institutions – Trinity College of Music and Laban Dance Centre. The conservatoire has ...

, Marylebone, London, from 1929 to 1965. He taught singing, conducted the College Choir, and was involved in the governance of the College. The College holds an archive relating to him, including manuscripts of some choral works, personal notebooks, concert programmes including many for the Oriana Madrigal Society, press cuttings and letters including correspondence received from well-known English composers. The collection also includes programmes from the memorial services of famous musicians which belonged to Kathleen Ewart, a singer in the Phoebus Singers, also a choir conducted by Scott. Scott died, aged 88, in London.

Charles Kennedy Scott and his wife Mary (née Donaldson) were the parents of the aviator

Charles Kennedy Scott and his wife Mary (née Donaldson) were the parents of the aviator C. W. A. Scott

Flight Lieutenant Charles William Anderson Scott, AFC (13 February 1903 – 15 April 1946Dunnell ''Aeroplane'', November 2019, p. 46.) was an English aviator. He won the MacRobertson Air Race, a race from London to Melbourne, in 1934, in a tim ...

(1903–1946) who was famous for winning the MacRobertson Air Race

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race (also known as the London to Melbourne Air Race) took place in October 1934 as part of the Melbourne Centenary celebrations. The race was devised by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir Harold Gengoult Smith, and th ...

, The Schlesinger African Air Race

The Schlesinger Race, also known as the ''"Rand Race"'', the ''"Portsmouth – Johannesburg Race"'' or more commonly the 'African Air Race', took place in September 1936. The Royal Aero Club announced the race on behalf of Isidore William Sch ...

and holding several England-Australia record solo flights, they also had a son John Kennedy Scott and a daughter Barbara Hamilton Scott, who married Major Leslie Stewart-Brown in October 1926. In 1946 whilst posted at the UNRRA

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in November 1943, it was dissolved in September 1948. it became part o ...

headquarters in Germany his son C.W.A. Scott

Flight Lieutenant Charles William Anderson Scott, Air Force Cross (United Kingdom), AFC (13 February 1903 – 15 April 1946Dunnell ''Aeroplane'', November 2019, p. 46.) was an English aviator. He won the MacRobertson Air Race, a race from Londo ...

committed suicide.

Writings

*''Madrigal Singing: A Few Remarks on the Study of Madrigal Music with an explanation of the Modes and a Note on their Relation to Polyphony'' (London 1907): 2nd, Amplified Edition (OUP, London 1931): Reprint (Greenwood Press 1970). *''Word and Tone: An English Method of Vocal Technique for Solo Singers and Choralists. In Two Books. Book I Theoretical, Book II Practical'' (2 vols, J.M. Dent & Sons, London 1933). *''The Fundamentals of Singing: An Inquiry into the Mechanical and Expressive Aspects of the Art.'' (Cassell & Co., London 1954). Scott also compiled and wrote two biographies detailing the life of his son C. W. A. Scott the famous aviator, one of the books mainly contains letters he received home from C. W. A. Scott over his entire life, with a biographical context added throughout the book by Charles Kennedy Scott. The other book is a shortened biography written almost solely by C. K. S. Both manuscripts remain unpublished, however, work has been done to digitally copy the hard copy's as part of ongoing work to create the digital back up of the Scott family Archive. this work is being done by James Scott, and Tim Barron who are both Charles's great grandchildren, they also plan to publish an edited version of one of these books at some time in the future once more work has been done to add some extra detail to what will become the publishable biography or life story of C. W. A. Scott.Scott family archive, held by Tim Barron, (digital copy by James Scott) please leave a message on this page's talk page if you wish to request a viewing.Musical publications

*''The Chelsea Song Book'' (folio), 20 traditional songs arranged for piano by Charles Kennedy Scott, with calligraphy by Margaret Shipton and 21 full and half-page chromolithographs by Juliet Wigan (Cresset Press Ltd, London 1927). *Giovanni Battista Pergolesi

Giovanni Battista Draghi (; 4 January 1710 – 16 or 17 March 1736), often referred to as Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (), was an Italian Baroque composer, violinist, and organist. His best-known works include his Stabat Mater and the opera ''L ...

''Stabat Mater'' edited and arranged by Charles Kennedy Scott, (OUP London c.1927).

Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Scott, Charles Kennedy 1876 births English conductors (music) British male conductors (music) People from Romsey 1965 deaths