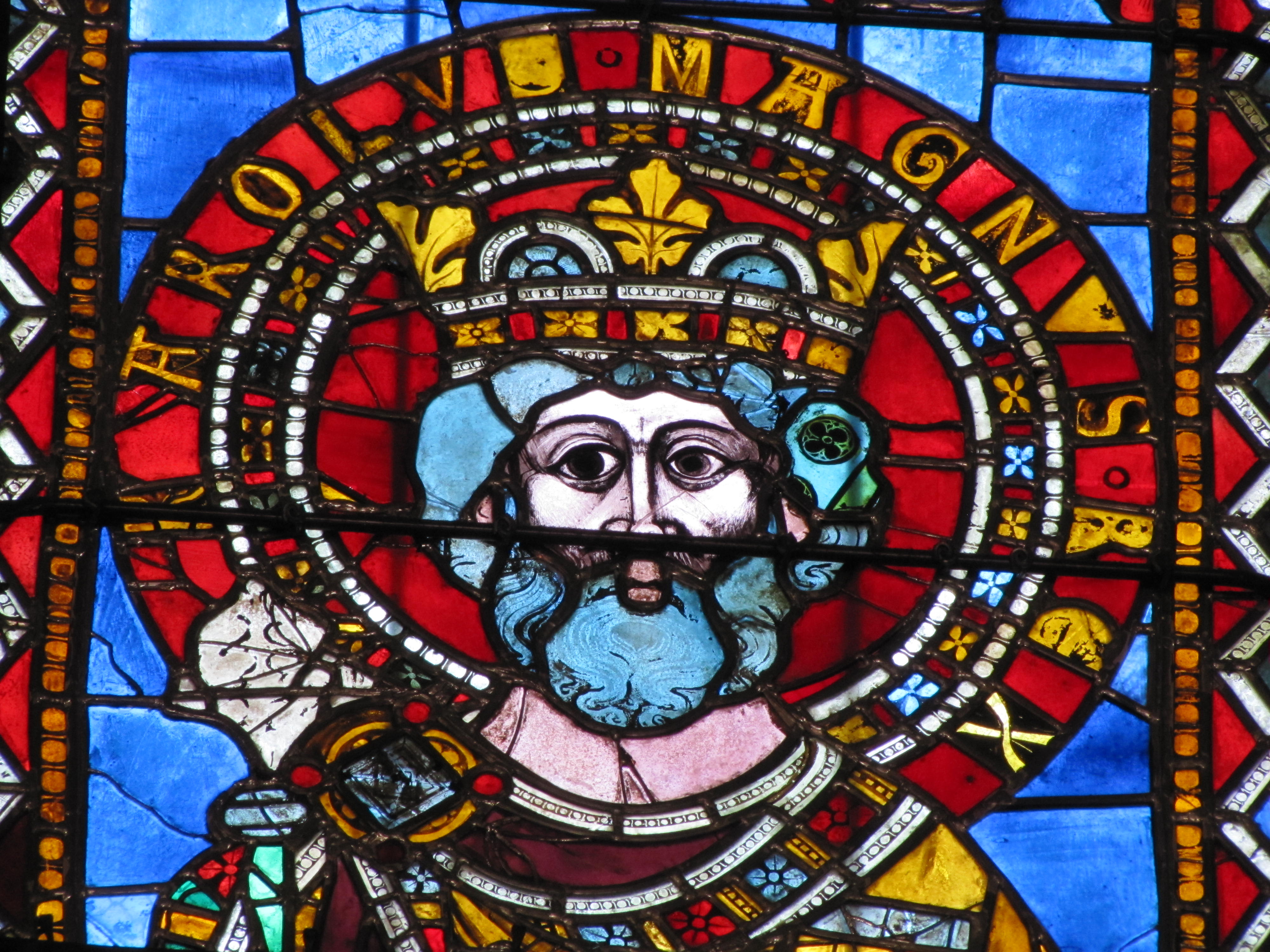

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the

Carolingian dynasty, was

King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

from 768,

King of the Lombards from 774, and the first

Emperor of the Romans from 800. Charlemagne succeeded in uniting the majority of

western and

central Europe and was the first recognized emperor to rule from western Europe after the

fall of the Western Roman Empire around three centuries earlier. The expanded Frankish state that Charlemagne founded was the

Carolingian Empire. He was

canonized by

Antipope Paschal III—an act later treated as invalid—and he is now regarded by some as

beatified (which is a step on the path to

saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

hood) in the

Catholic Church.

Charlemagne was the eldest son of

Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

and

Bertrada of Laon. He was born before their

canonical marriage. He became king of the Franks in 768 following his father's death, and was initially co-ruler with his brother

Carloman I until the latter's death in 771. As sole ruler, he continued his father's policy towards protection of the papacy and became its sole defender, removing the

Lombards from power in northern

Italy and leading an incursion into

Muslim Spain. He also campaigned against the

Saxons to his east,

Christianizing them (upon penalty of death) which led to events such as the

Massacre of Verden. He reached the height of his power in 800 when he was

crowned Emperor of the Romans by

Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

on

Christmas Day at

Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

Charlemagne has been called the "Father of Europe" (''Pater Europae''), as he united most of Western Europe for the first time since the

classical era of the

Roman Empire, as well as uniting parts of Europe that had never been under Frankish or Roman rule. His reign spurred the

Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the State church of the Roman Emp ...

, a period of energetic cultural and intellectual activity within the

Western Church. The

Eastern Orthodox Church viewed Charlemagne less favourably, due to his support of the

filioque and the Pope's preference of him as emperor over the

Byzantine Empire's first female monarch,

Irene of Athens. These and other disputes led to the eventual split of

Rome and

Constantinople in the

Great Schism of 1054.

Charlemagne died in 814 after contracting an infectious lung disease. He was laid to rest in the

Aachen Cathedral

Aachen Cathedral (german: Aachener Dom) is a Roman Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Aachen.

One of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, it was constructed by order of Emperor Charlemagne, who was buri ...

, in his imperial capital city of

Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

. He married at least four times,

and had three legitimate sons who lived to adulthood. Only the youngest of them,

Louis the Pious, survived to succeed him. Charlemagne and his predecessors are the direct ancestors of many of Europe's

royal houses, including the

Capetian dynasty

The Capetian dynasty (; french: Capétiens), also known as the House of France, is a dynasty of Frankish origin, and a branch of the Robertians. It is among the largest and oldest royal houses in Europe and the world, and consists of Hugh Cape ...

, the

Ottonian dynasty

The Ottonian dynasty (german: Ottonen) was a Saxon dynasty of German monarchs (919–1024), named after three of its kings and Holy Roman Emperors named Otto, especially its first Emperor Otto I. It is also known as the Saxon dynasty after the ...

, the

House of Luxembourg, the

House of Ivrea and the

House of Habsburg.

Names and nicknames

The name Charlemagne ( ), by which the emperor is normally known in English, comes from the French ''Charles-le-magne'', meaning "Charles the Great"., ''Karil'' or ''Karal'', whence in German and in Dutch. In modern German, ''Karl der Große'' has the same meaning. His given name was Charles (

Latin ''Carolus'',

Old High German ''Karlus'',

Romance ''Karlo''). He was named after his grandfather,

Charles Martel, a choice which intentionally marked him as Martel's true heir.

The nickname ''magnus'' (great) may have been associated with him already in his lifetime, but this is not certain. The contemporary Latin ''

Royal Frankish Annals'' routinely call him ''Carolus magnus rex'', "Charles the great king". As a nickname, it is only certainly attested in the works of the

Poeta Saxo around 900 and it only became standard in all the lands of his former empire around 1000.

Charles' achievements gave a new meaning to

his name. In many

languages of Europe

Most languages of Europe belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. Within Indo-European, the three largest phyla are Rom ...

, the very word for "king" derives from his name; e.g., pl, król, uk, король (korol'), cs, král, sk, kráľ, hu, király, lt, karalius, lv, karalis, russian: король, mk, крал, bg, крал, sh-Cyrl, краљ/kralj, tr, kral. This development parallels that of the name of the

Caesars in the original Roman Empire, which became ''kaiser'' and ''tsar'' (or ''czar''), among others.

Political background

By the 6th century, the western

Germanic tribe of the

Franks had been

Christianised, due in considerable measure to the Catholic conversion of

Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single kin ...

.

Francia, ruled by the

Merovingians, was the most powerful of the kingdoms that succeeded the

Western Roman Empire. Following the

Battle of Tertry

The Battle of Tertry was an important engagement in Merovingian Gaul between the forces of Austrasia under Pepin II on one side and those of Neustria and Burgundy on the other. It took place in 687 at Tertry, Somme, and the battle is presented as ...

, the Merovingians declined into powerlessness, for which they have been dubbed the ''

rois fainéants'' ("do-nothing kings"). Almost all government powers were exercised by their chief officer, the

mayor of the palace.

In 687,

Pepin of Herstal, mayor of the palace of

Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

, ended the strife between various kings and their mayors with his victory at Tertry. He became the sole governor of the entire Frankish kingdom. Pepin was the grandson of two important figures of the Austrasian Kingdom: Saint

Arnulf of Metz and

Pepin of Landen. Pepin of Herstal was eventually succeeded by his son Charles, later known as

Charles Martel (Charles the Hammer).

After 737, Charles governed the Franks in lieu of a king and declined to call himself ''king''. Charles was succeeded in 741 by his sons

Carloman and

Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

, the father of Charlemagne. In 743, the brothers placed

Childeric III on the throne to curb separatism in the periphery. He was the last Merovingian king. Carloman resigned office in 746, preferring to enter the church as a monk. Pepin brought the question of the kingship before

Pope Zachary

Pope Zachary ( la, Zacharias; 679 – March 752) was the bishop of Rome from 28 November 741 to his death. He was the last pope of the Byzantine Papacy. Zachary built the original church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, forbade the traffic of slav ...

, asking whether it was logical for a king to have no royal power. The pope handed down his decision in 749, decreeing that it was better for Pepin to be called king, as he had the powers of high office as Mayor, so as not to confuse the hierarchy. He, therefore, ordered him to become the ''true king''.

In 750, Pepin was elected by an assembly of the Franks, anointed by the archbishop, and then raised to the office of king. The Pope branded Childeric III as "the false king" and ordered him into a monastery. The Merovingian dynasty was thereby replaced by the

Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

dynasty, named after Charles Martel. In 753,

Pope Stephen II

Pope Stephen II ( la, Stephanus II; 714 – 26 April 757) was born a Roman aristocrat and member of the Orsini family. Stephen was the bishop of Rome from 26 March 752 to his death. Stephen II marks the historical delineation between the Byzant ...

fled from Italy to Francia, appealing to Pepin for assistance for the rights of St. Peter. He was supported in this appeal by Carloman, Charles' brother. In return, the pope could provide only legitimacy. He did this by again anointing and confirming Pepin, this time adding his young sons Carolus (Charlemagne) and Carloman to the royal patrimony. They thereby became heirs to the realm that already covered most of western Europe. In 754, Pepin accepted the Pope's invitation to visit Italy on behalf of St. Peter's rights, dealing successfully with the

Lombards.

Under the Carolingians, the Frankish kingdom spread to encompass an area including most of Western Europe; the later east–west division of the kingdom formed the basis for modern

France and

Germany. Orman portrays the

Treaty of Verdun (843) between the warring grandsons of Charlemagne as the foundation event of an independent

France under its first king

Charles the Bald; an independent Germany under its first king

Louis the German; and an independent intermediate state stretching from the

Low Countries along the borderlands to south of Rome under

Lothair I

Lothair I or Lothar I (Dutch and Medieval Latin: ''Lotharius''; German: ''Lothar''; French: ''Lothaire''; Italian: ''Lotario'') (795 – 29 September 855) was emperor (817–855, co-ruling with his father until 840), and the governor of Bavar ...

, who retained the title of emperor and the capitals

Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

and Rome without the jurisdiction. The middle kingdom had broken up by 890 and partly absorbed into the Western kingdom (later France) and the Eastern kingdom (Germany) and the rest developing into smaller "buffer" states that exist between France and Germany to this day, namely

Benelux and

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

.

Rise to power

Early life

Roman road connecting Tongeren to the Herstal region. Jupille and Herstal, near Liege, are located in the lower right corner

The most likely date of Charlemagne's birth is reconstructed from several sources. The date of 742—calculated from

Einhard

Einhard (also Eginhard or Einhart; la, E(g)inhardus; 775 – 14 March 840) was a Frankish scholar and courtier. Einhard was a dedicated servant of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious; his main work is a biography of Charlemagne, the ''Vita ...

's date of death of January 814 at age 72—predates the marriage of his parents in 744. The year given in the ''

Annales Petaviani'', 747, would be more likely, except that it contradicts Einhard and a few other sources in making Charlemagne sixty-seven years old at his death. The month and day of 2 April are based on a calendar from

Lorsch Abbey.

Charlemagne claimed descent from the Roman emperor,

Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterranea ...

.

In 747,

Easter fell on 2 April, a coincidence that likely would have been remarked upon by chroniclers but was not. If Easter was being used as the beginning of the calendar year, then 2 April 747 could have been, by modern reckoning, April 748 (not on Easter). The date favoured by the preponderance of evidence is 2 April 742, based on Charlemagne's age at the time of his death.

This date supports the concept that Charlemagne was technically an

illegitimate child, although that is not mentioned by Einhard in either since he was born out of wedlock; Pepin and Bertrada were bound by a private contract or

Friedelehe at the time of his birth, but did not marry until 744.

Charlemagne's exact birthplace is unknown, although historians have suggested Aachen in modern-day Germany, and

Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

(

Herstal) in present-day

Belgium as possible locations. Aachen and

Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

are close to the region whence the Merovingian and Carolingian families originated. Other cities have been suggested, including

Düren

Düren (; ripuarian: Düre) is a town in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, between Aachen and Cologne on the river Rur.

History

Roman era

The area of Düren was part of Gallia Belgica, more specifically the territory of the Eburones, a people ...

,

Gauting

Gauting is a municipality in the district of Starnberg, in Bavaria, Germany with a population of approximately 20,000. It is situated on the river Würm, southwest of Munich and is a part of the Munich metropolitan area.

Geography

Stockdorf, ...

,

Mürlenbach

Mürlenbach is an ''Ortsgemeinde'' – a municipality belonging to a ''Verbandsgemeinde'', a kind of collective municipality – in the Vulkaneifel district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' of Gerolstein, wh ...

,

Quierzy, and

Prüm

Prüm () is a town in the Westeifel (Rhineland-Palatinate), Germany. Formerly a district capital, today it is the administrative seat of the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' ("collective municipality") Prüm.

Geography

Prüm lies on the river Prüm (a tri ...

. No definitive evidence resolves the question.

Ancestry

Charlemagne was the eldest child of

Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

(714 – 24 September 768, reigned from 751) and his wife

Bertrada of Laon (720 – 12 July 783), daughter of

Caribert of Laon. Many historians consider Charlemagne (Charles) to have been illegitimate, although some state that this is arguable, because Pepin did not marry Bertrada until 744, which was after Charles' birth; this status did not exclude him from the succession.

Records name only

Carloman,

Gisela, and three short-lived children named Pepin, Chrothais and Adelais as his younger siblings.

Ambiguous high office

The most powerful officers of the Frankish people, the

Mayor of the Palace (''Maior Domus'') and one or more kings (''rex'', ''reges''), were appointed by the election of the people. Elections were not periodic, but were held as required to elect officers ''ad quos summa imperii pertinebat'', "to whom the highest matters of state pertained". Evidently, interim decisions could be made by the Pope, which ultimately needed to be ratified using an assembly of the people that met annually.

Before he was elected king in 751, Pepin was initially a mayor, a high office he held "as though hereditary" (''velut hereditario fungebatur''). Einhard explains that "the honour" was usually "given by the people" to the distinguished, but Pepin the Great and his brother Carloman the Wise received it as though hereditary, as had their father,

Charles Martel. There was, however, a certain ambiguity about quasi-inheritance. The office was treated as joint property: one Mayorship held by two brothers jointly. Each, however, had his own geographic jurisdiction. When Carloman decided to resign, becoming ultimately a Benedictine at

Monte Cassino, the question of the disposition of his quasi-share was settled by the pope. He converted the mayorship into a kingship and awarded the joint property to Pepin, who gained the right to pass it on by inheritance.

This decision was not accepted by all family members. Carloman had consented to the temporary tenancy of his own share, which he intended to pass on to his son, Drogo, when the inheritance should be settled at someone's death. By the Pope's decision, in which Pepin had a hand, Drogo was to be disqualified as an heir in favour of his cousin Charles. He took up arms in opposition to the decision and was joined by

Grifo, a half-brother of Pepin and Carloman, who had been given a share by Charles Martel, but was stripped of it and held under loose arrest by his half-brothers after an attempt to seize their shares by military action. Grifo perished in combat in the Battle of

Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne while Drogo was hunted down and taken into custody.

According to the ''Life'', Pepin died in Paris on 24 September 768, whereupon the kingship passed jointly to his sons, "with divine assent" (''divino nutu''). The Franks "in general assembly" (''generali conventu'') gave them both the rank of a king (''reges'') but "partitioned the whole body of the kingdom equally" (''totum regni corpus ex aequo partirentur''). The ''annals'' tell a slightly different version, with the king dying at

St-Denis, near Paris. The two "lords" (''domni'') were "elevated to kingship" (''elevati sunt in regnum''), Charles on 9 October in

Noyon, Carloman on an unspecified date in

Soissons. If born in 742, Charles was 26 years old, but he had been campaigning at his father's right hand for several years, which may help to account for his military skill.

Carloman was 17.

The language, in either case, suggests that there were not two inheritances, which would have created distinct kings ruling over distinct kingdoms, but a single joint inheritance and a joint kingship tenanted by two equal kings, Charles and his brother Carloman. As before, distinct jurisdictions were awarded. Charles received Pepin's original share as Mayor: the outer parts of the kingdom bordering on the sea, namely

Neustria, western

Aquitaine, and the northern parts of

Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

; while Carloman was awarded his uncle's former share, the inner parts: southern Austrasia,

Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

, eastern Aquitaine,

Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

, Provence, and

Swabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

, lands bordering

Italy. The question of whether these jurisdictions were joint shares reverting to the other brother if one brother died or were inherited property passed on to the descendants of the brother who died was never definitely settled. It came up repeatedly over the succeeding decades until the grandsons of Charlemagne created distinct sovereign kingdoms.

Aquitainian rebellion

Formation of a new Aquitaine

In southern

Gaul,

Aquitaine had been Romanised and people spoke a

Romance language

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European languages, I ...

. Similarly,

Hispania had been populated by peoples who spoke various languages, including

Celtic, but these had now been mostly replaced by Romance languages. Between Aquitaine and Hispania were the

Euskaldunak, Latinised to

Vascones, or

Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Bas ...

, whose country, Vasconia, extended, according to the distributions of place names attributable to the Basques, mainly in the western

Pyrenees but also as far south as the upper river

Ebro in Spain and as far north as the river

Garonne in France. The French name

Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

derives from

Vasconia

The Duchy of Gascony or Duchy of Vasconia ( eu, Baskoniako dukerria; oc, ducat de Gasconha; french: duché de Gascogne, duché de Vasconie) was a duchy located in present-day southwestern France and northeastern Spain, an area encompassing the m ...

. The Romans were never able to subjugate the whole of Vasconia. The soldiers they recruited for the Roman legions from those parts they did submit and where they founded the region's first cities were valued for their fighting abilities. The border with Aquitaine was at

Toulouse.

In about 660, the

Duchy of Vasconia united with the

Duchy of Aquitaine to form a single realm under

Felix of Aquitaine, ruling from Toulouse. This was a joint kingship with a Basque Duke,

Lupus I. ''Lupus'' is the Latin translation of Basque Otsoa, "wolf". At Felix's death in 670 the joint property of the kingship reverted entirely to Lupus. As the Basques had no law of joint inheritance but relied on

primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

,

Lupus

Lupus, technically known as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is an autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue in many parts of the body. Symptoms vary among people and may be mild to severe. Comm ...

in effect founded a hereditary dynasty of Basque rulers of an expanded Aquitaine.

Acquisition of Aquitaine by the Carolingians

The Latin chronicles of the end of

Visigothic Hispania omit many details, such as identification of characters, filling in the gaps and reconciliation of numerous contradictions. Muslim sources, however, present a more coherent view, such as in the ''Ta'rikh iftitah al-Andalus'' ("History of the Conquest of al-Andalus") by

Ibn al-Qūṭiyya ("the son of the Gothic woman", referring to the granddaughter of

Wittiza

Wittiza (''Witiza'', ''Witica'', ''Witicha'', ''Vitiza'', or ''Witiges''; 687 – probably 710) was the Visigothic King of Hispania from 694 until his death, co-ruling with his father, Egica, until 702 or 703.

Joint rule

Early in his reign, Ergi ...

, the last Visigothic king of a united Hispania, who married a Moor). Ibn al-Qūṭiyya, who had another, much longer name, must have been relying to some degree on family oral tradition.

According to Ibn al-Qūṭiyya

Wittiza

Wittiza (''Witiza'', ''Witica'', ''Witicha'', ''Vitiza'', or ''Witiges''; 687 – probably 710) was the Visigothic King of Hispania from 694 until his death, co-ruling with his father, Egica, until 702 or 703.

Joint rule

Early in his reign, Ergi ...

, the last Visigothic king of a united Hispania, died before his three sons, Almund, Romulo, and Ardabast reached maturity. Their mother was

queen regent at

Toledo

Toledo most commonly refers to:

* Toledo, Spain, a city in Spain

* Province of Toledo, Spain

* Toledo, Ohio, a city in the United States

Toledo may also refer to:

Places Belize

* Toledo District

* Toledo Settlement

Bolivia

* Toledo, Orur ...

, but

Roderic

Roderic (also spelled Ruderic, Roderik, Roderich, or Roderick; Spanish and pt, Rodrigo, ar, translit=Ludharīq, لذريق; died 711) was the Visigothic king in Hispania between 710 and 711. He is well-known as "the last king of the Goths". He ...

, army chief of staff, staged a rebellion, capturing

Córdoba. He chose to impose a joint rule over distinct jurisdictions on the true heirs. Evidence of a division of some sort can be found in the distribution of coins imprinted with the name of each king and in the king lists. Wittiza was succeeded by Roderic, who reigned for seven and a half years, followed by Achila (Aquila), who reigned three and a half years. If the reigns of both terminated with the incursion of the

Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century Germany in the Middle Ages, German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings, to refer ...

, then Roderic appears to have reigned a few years before the majority of Achila. The latter's kingdom was securely placed to the northeast, while Roderic seems to have taken the rest, notably modern

Portugal.

The Saracens crossed the mountains to claim Ardo's

Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

, only to encounter the Basque dynasty of Aquitaine, always the allies of the Goths.

Odo the Great of

Aquitaine was at first victorious at the

Battle of Toulouse in 721. Saracen troops gradually massed in Septimania and, in 732, an army under Emir

Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi advanced into Vasconia, and Odo was defeated at the

Battle of the River Garonne

The Battle of the River Garonne, also known as the Battle of Bordeaux,Matthew Bennett ''The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare'' 1579581161 1998 p319 "In 732 a large army of (70,000-80,000) men led by Abd ar-Rahman defeated the Aq ...

. They took

Bordeaux and were advancing towards

Tours when Odo, powerless to stop them, appealed to his arch-enemy,

Charles Martel, mayor of the Franks. In one of the first of the lightning marches for which the Carolingian kings became famous, Charles and his army appeared in the path of the Saracens between Tours and

Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomerat ...

, and in the

Battle of Tours decisively defeated and killed al-Ghafiqi. The Moors returned twice more, each time suffering defeat at Charles' hands—at the River Berre near Narbonne in 737 and in the

Dauphiné in 740.

Odo's price for salvation from the Saracens was incorporation into the Frankish kingdom, a decision that was repugnant to him and also to his heirs.

Loss and recovery of Aquitaine

After the death of his father,

Hunald I allied himself with free

Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

. However, Odo had ambiguously left the kingdom jointly to his two sons, Hunald and Hatto. The latter, loyal to Francia, now went to war with his brother over full possession. Victorious, Hunald blinded and imprisoned his brother, only to be so stricken by conscience that he resigned and entered the church as a monk to do penance. The story is told in

Annales Mettenses priores.

His son

Waifer took an early inheritance, becoming duke of Aquitaine and ratifying the alliance with Lombardy. Waifer, deciding to honour it, repeated his father's decision, which he justified by arguing that any agreements with Charles Martel became invalid on Martel's death. Since

Aquitaine was now Pepin's inheritance because of the earlier assistance given by Charles Martel, according to some, the latter and his son, the young Charles, hunted down Waifer, who could only conduct a guerrilla war, and executed him.

Among the contingents of the Frankish army were

Bavarians under

Tassilo III, Duke of Bavaria, an

Agilofing, the hereditary Bavarian ducal family.

Grifo had installed himself as Duke of Bavaria, but Pepin replaced him with a member of the ducal family yet a child, Tassilo, whose protector he had become after the death of his father. The loyalty of the Agilolfings was perpetually in question, but Pepin exacted numerous oaths of loyalty from Tassilo. However, the latter had married

Liutperga

Liutperga (Liutpirc) (fl 750 - fl. 793) was a Duchess of Bavaria by marriage to Tassilo III, the last Agilolfing Duke of Bavaria. She was the daughter of Desiderius, King of the Lombards, and Ansa.

Duchess of Bavaria

She was married to Tassilo ...

, a daughter of

Desiderius, king of

Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

. At a critical point in the campaign, Tassilo left the field with all his Bavarians. Out of reach of Pepin, he repudiated all loyalty to Francia. Pepin had no chance to respond as he grew ill and died within a few weeks after Waifer's execution.

The first event of the brothers' reign was the uprising of the Aquitainians and

Gascons in 769, in that territory split between the two kings. One year earlier, Pepin had finally defeated

Waifer,

Duke of Aquitaine, after waging a destructive, ten-year war against Aquitaine. Now,

Hunald II Hunald II, also spelled Hunold, Hunoald, Hunuald or Chunoald (French: ''Hunaud''), was the Duke of Aquitaine from 768 until 769. He was probably the son of Duke Waiofar, who was assassinated on the orders of King Pippin the Short in 768. He laid cla ...

led the Aquitainians as far north as

Angoulême

Angoulême (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Engoulaeme''; oc, Engoleime) is a communes of France, commune, the Prefectures of France, prefecture of the Charente Departments of France, department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwestern Franc ...

. Charles met Carloman, but Carloman refused to participate and returned to Burgundy. Charles went to war, leading an army to

Bordeaux, where he built a fortified camp on the mound at

Fronsac. Hunald was forced to flee to the court of Duke

Lupus II of Gascony. Lupus, fearing Charles, turned Hunald over in exchange for peace, and Hunald was put in a monastery. Gascon lords also surrendered, and Aquitaine and

Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

were finally fully subdued by the Franks.

Marriage to Desiderata

The brothers maintained lukewarm relations with the assistance of their mother Bertrada, but in 770 Charles signed a treaty with Duke

Tassilo III of Bavaria and married a Lombard Princess (commonly known today as

Desiderata), the daughter of King Desiderius, to surround Carloman with his own allies. Though

Pope Stephen III first opposed the marriage with the Lombard princess, he found little to fear from a Frankish-Lombard alliance.

Less than a year after his marriage, Charlemagne repudiated Desiderata and married a 13-year-old Swabian named

Hildegard

Hildegard is a female name derived from the Old High German ''hild'' ('war' or 'battle') and ''gard'' ('enclosure' or 'yard'), and means 'battle enclosure'. Variant spellings include: Hildegarde; the Polish, Portuguese, Slovene and Spanish Hildeg ...

. The repudiated Desiderata returned to her father's court at

Pavia. Her father's wrath was now aroused, and he would have gladly allied with Carloman to defeat Charles. Before any open hostilities could be declared, however, Carloman died on 5 December 771, apparently of natural causes. Carloman's widow

Gerberga fled to Desiderius' court with her sons for protection.

Wives, concubines, and children

Charlemagne had eighteen children with seven of his ten known wives or concubines.

[Durant, Will]

"King Charlemagne."

. Story of Civilization, Vol III, ''The Age of Faith''. Online version in the Knighthood, Tournaments & Chivalry Resource Library, Ed. Brian R. Price. Nonetheless, he had only four legitimate grandsons, the four sons of his fourth son, Louis. In addition, he had a grandson (

Bernard of Italy, the only son of his third son,

Pepin of Italy

Pepin or Pippin (or ''Pepin Carloman'', ''Pepinno'', April 777 – 8 July 810), born Carloman, was the son of Charlemagne and King of the Lombards (781–810) under the authority of his father.

Pepin was the second son of Charlemagne by his th ...

), who was illegitimate but included in the line of inheritance. Among his descendants are several royal dynasties, including the

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

, and

Capetian dynasties. By consequence, most if not all established European noble families ever since can genealogically trace some of their background to Charlemagne.

Children

During the first peace of any substantial length (780–782), Charles began to appoint his sons to positions of authority. In 781, during a visit to Rome, he made his two youngest sons kings, crowned by the Pope. The elder of these two,

Carloman, was made the

king of Italy, taking the Iron Crown that his father had first worn in 774, and in the same ceremony was renamed "Pepin"

[Charlemagne](_blank)

Encyclopædia Britannica (not to be confused with Charlemagne's eldest, possibly illegitimate son,

Pepin the Hunchback). The younger of the two,

Louis, became

King of Aquitaine. Charlemagne ordered Pepin and Louis to be raised in the customs of their kingdoms, and he gave their regents some control of their subkingdoms, but kept the real power, though he intended his sons to inherit their realms. He did not tolerate insubordination in his sons: in 792, he banished Pepin the Hunchback to

Prüm Abbey because the young man had joined a rebellion against him.

Charles was determined to have his children educated, including his daughters, as his parents had instilled the importance of learning in him at an early age. His children were also taught skills in accord with their aristocratic status, which included training in riding and weaponry for his sons, and embroidery, spinning and weaving for his daughters.

The sons fought many wars on behalf of their father.

Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

was mostly preoccupied with the Bretons, whose border he shared and who insurrected on at least two occasions and were easily put down. He also fought the Saxons on multiple occasions. In 805 and 806, he was sent into the Böhmerwald (modern

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

) to deal with the Slavs living there (Bohemian tribes, ancestors of the modern

Czechs). He subjected them to Frankish authority and devastated the valley of the Elbe, forcing tribute from them. Pippin had to hold the

Avar and Beneventan borders and fought the

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

to his north. He was uniquely poised to fight the

Byzantine Empire when that conflict arose after Charlemagne's imperial coronation and a

Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

rebellion. Finally, Louis was in charge of the

Spanish March and fought the Duke of Benevento in southern Italy on at least one occasion. He took

Barcelona in

a great siege in 801.

Charlemagne kept his daughters at home with him and refused to allow them to contract

sacramental marriages (though he originally condoned an engagement between his eldest daughter Rotrude and

Constantine VI of Byzantium, this engagement was annulled when Rotrude was 11). Charlemagne's opposition to his daughters' marriages may possibly have intended to prevent the creation of

cadet branches of the family to challenge the main line, as had been the case with

Tassilo of Bavaria. However, he tolerated their extramarital relationships, even rewarding their common-law husbands and treasuring the illegitimate grandchildren they produced for him. He also refused to believe stories of their wild behaviour. After his death the surviving daughters were banished from the court by their brother, the pious Louis, to take up residence in the convents they had been bequeathed by their father. At least one of them, Bertha, had a recognised relationship, if not a marriage, with

Angilbert, a member of Charlemagne's court circle.

Italian campaigns

Conquest of the Lombard kingdom

At his succession in 772,

Pope Adrian I demanded the return of certain cities in the former

exarchate of Ravenna in accordance with a promise at the succession of Desiderius. Instead, Desiderius took over certain papal cities and invaded the

Pentapolis

A pentapolis (from Greek ''penta-'', 'five' and ''polis'', 'city') is a geographic and/or institutional grouping of five cities. Cities in the ancient world probably formed such groups for political, commercial and military reasons, as happened ...

, heading for Rome. Adrian sent ambassadors to Charlemagne in autumn requesting he enforce the policies of his father, Pepin. Desiderius sent his own ambassadors denying the pope's charges. The ambassadors met at

Thionville, and Charlemagne upheld the pope's side. Charlemagne demanded what the pope had requested, but Desiderius swore never to comply. Charlemagne and his uncle

Bernard crossed the Alps in 773 and chased the Lombards back to

Pavia, which they then besieged.

Charlemagne temporarily left the siege to deal with

Adelchis, son of Desiderius, who was raising an army at

Verona. The young prince was chased to the

Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

littoral and fled to

Constantinople to plead for assistance from

Constantine V, who was waging war with

Bulgaria.

The siege lasted until the spring of 774 when Charlemagne visited the pope in Rome. There he confirmed

his father's grants of land,

with some later chronicles falsely claiming that he also expanded them, granting

Tuscany,

Emilia, Venice and

Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

. The pope granted him the title ''

patrician''. He then returned to Pavia, where the Lombards were on the verge of surrendering. In return for their lives, the Lombards surrendered and opened the gates in early summer. Desiderius was sent to the

abbey of

Corbie, and his son Adelchis died in Constantinople, a patrician. Charles, unusually, had himself crowned with the

Iron Crown and made the magnates of Lombardy pay homage to him at Pavia. Only Duke

Arechis II of Benevento refused to submit and proclaimed independence. Charlemagne was then master of Italy as king of the Lombards. He left Italy with a garrison in Pavia and a few Frankish counts in place the same year.

Instability continued in Italy. In 776, Dukes

Hrodgaud of Friuli and

Hildeprand of Spoleto rebelled. Charlemagne rushed back from

Saxony and defeated the Duke of Friuli in battle; the Duke was slain. The Duke of Spoleto signed a treaty. Their co-conspirator, Arechis, was not subdued, and Adelchis, their candidate in

Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

, never left that city. Northern Italy was now faithfully his.

Southern Italy

In 787, Charlemagne directed his attention towards the

Duchy of Benevento, where

Arechis II

Arechis II (also ''Aretchis'', ''Arichis'', ''Arechi'' or ''Aregis'') (born According to the ''Chronicon Salernitanum'', Arechis ''vixit autem quinquaginta tres (53) annos; obiit septimo Kal. Septembris, anno ab incarnacione Domini 787, indictione ...

was reigning independently with the self-given title of

Princeps. Charlemagne's siege of

Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

forced Arechis into submission. However, after Arechis II's death in 787, his son

Grimoald III

Grimoald III ( – 806) was the Lombard Prince of Benevento from 788 until his own death. He was the second son of Arechis II and Adelperga. In 787, he and his elder brother Romoald were sent as hostages to Charlemagne who had descended the It ...

proclaimed the Duchy of Benevento newly independent. Grimoald was attacked many times by Charles' or his sons' armies, without achieving a definitive victory. Charlemagne lost interest and never again returned to

Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

where Grimoald was able to keep the Duchy free from Frankish

suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

.

Carolingian expansion to the south

Vasconia and the Pyrenees

The destructive war led by Pepin in Aquitaine, although brought to a satisfactory conclusion for the Franks, proved the Frankish power structure south of the

Loire was feeble and unreliable. After the defeat and death of

Waiofar in 768, while Aquitaine submitted again to the Carolingian dynasty, a new rebellion broke out in 769 led by Hunald II, a possible son of Waifer. He took refuge with the ally Duke

Lupus II of Gascony, but probably out of fear of Charlemagne's reprisal, Lupus handed him over to the new King of the Franks to whom he pledged loyalty, which seemed to confirm the peace in

the Basque area south of the

Garonne.

In the campaign of 769, Charlemagne seems to have followed a policy of "overwhelming force" and avoided a major pitched battle

Wary of new Basque uprisings, Charlemagne seems to have tried to contain Duke Lupus's power by appointing

Seguin as the Count of Bordeaux (778) and other counts of Frankish background in bordering areas (

Toulouse,

County of Fézensac). The

Basque Duke, in turn, seems to have contributed decisively or schemed the

Battle of Roncevaux Pass (referred to as "Basque treachery"). The defeat of Charlemagne's army in Roncevaux (778) confirmed his determination to rule directly by establishing the Kingdom of Aquitaine (ruled by

Louis the Pious) based on a power base of Frankish officials, distributing lands among colonisers and allocating lands to the Church, which he took as an ally. A Christianisation programme was put in place across the high

Pyrenees (778).

[

The new political arrangement for Vasconia did not sit well with local lords. As of 788 Adalric was fighting and capturing Chorson, Carolingian Count of Toulouse. He was eventually released, but Charlemagne, enraged at the compromise, decided to depose him and appointed his trustee William of Gellone. William, in turn, fought the Basques and defeated them after banishing Adalric (790).][

From 781 ( Pallars, Ribagorça) to 806 ( Pamplona under Frankish influence), taking the County of Toulouse for a power base, Charlemagne asserted Frankish authority over the Pyrenees by subduing the south-western marches of Toulouse (790) and establishing vassal counties on the southern Pyrenees that were to make up the ]Marca Hispanica

The Hispanic March or Spanish March ( es, Marca Hispánica, ca, Marca Hispànica, Aragonese and oc, Marca Hispanica, eu, Hispaniako Marka, french: Marche d'Espagne), was a military buffer zone beyond the former province of Septimania, esta ...

. As of 794, a Frankish vassal, the Basque lord Belasko (''al-Galashki'', 'the Gaul') ruled Álava, but Pamplona remained under Cordovan and local control up to 806. Belasko and the counties in the Marca Hispánica provided the necessary base to attack the Andalusians (an expedition led by William Count of Toulouse and Louis the Pious to capture Barcelona in 801). Events in the Duchy of Vasconia (rebellion in Pamplona, count overthrown in Aragon, Duke Seguin of Bordeaux deposed, uprising of the Basque lords, etc.) were to prove it ephemeral upon Charlemagne's death.

Roncesvalles campaign

According to the Muslim historian Ibn al-Athir, the Diet of Paderborn had received the representatives of the Muslim rulers of Zaragoza, Girona, Barcelona and Huesca. Their masters had been cornered in the Iberian peninsula by Abd ar-Rahman I, the Umayyad emir of Cordova. These "Saracen" (Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or se ...

and Muwallad) rulers offered their homage to the king of the Franks in return for military support. Seeing an opportunity to extend Christendom and his own power, and believing the Saxons to be a fully conquered nation, Charlemagne agreed to go to Spain.

In 778, he led the Neustrian army across the Western Pyrenees, while the Austrasians, Lombards, and Burgundians passed over the Eastern Pyrenees. The armies met at Saragossa and Charlemagne received the homage of the Muslim rulers, Sulayman al-Arabi and Kasmin ibn Yusuf, but the city did not fall for him. Indeed, Charlemagne faced the toughest battle of his career. The Muslims forced him to retreat, so he decided to go home, as he could not trust the Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Bas ...

, whom he had subdued by conquering Pamplona. He turned to leave Iberia, but as his army was crossing back through the Pass of Roncesvalles, one of the most famous events of his reign occurred: the Basques attacked and destroyed his rearguard and baggage train. The Battle of Roncevaux Pass, though less a battle than a skirmish, left many famous dead, including the seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

Eggihard, the count of the palace Anselm, and the warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

of the Breton March, Roland

Roland (; frk, *Hrōþiland; lat-med, Hruodlandus or ''Rotholandus''; it, Orlando or ''Rolando''; died 15 August 778) was a Frankish military leader under Charlemagne who became one of the principal figures in the literary cycle known as the ...

, inspiring the subsequent creation of '' The Song of Roland'' (''La Chanson de Roland''), regarded as the first major work in the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

.

Contact with the Saracens

The conquest of Italy brought Charlemagne in contact with the Saracens who, at the time, controlled the Mediterranean. Charlemagne's eldest son, Pepin the Hunchback, was much occupied with Saracens in Italy. Charlemagne conquered

The conquest of Italy brought Charlemagne in contact with the Saracens who, at the time, controlled the Mediterranean. Charlemagne's eldest son, Pepin the Hunchback, was much occupied with Saracens in Italy. Charlemagne conquered Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

and Sardinia at an unknown date and in 799 the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

. The islands were often attacked by Saracen pirates, but the counts of Genoa and Tuscany ( Boniface) controlled them with large fleets until the end of Charlemagne's reign. Charlemagne even had contact with the caliphal court in Baghdad. In 797 (or possibly 801), the caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, presented Charlemagne with an Asian elephant named Abul-Abbas and a clock.

Wars with the Moors

In Hispania, the struggle against the Moors continued unabated throughout the latter half of his reign. Louis was in charge of the Spanish border. In 785, his men captured Girona permanently and extended Frankish control into the Catalan littoral for the duration of Charlemagne's reign (the area remained nominally Frankish until the Treaty of Corbeil in 1258). The Muslim chiefs in the northeast of Islamic Spain were constantly rebelling against Cordovan authority, and they often turned to the Franks for help. The Frankish border was slowly extended until 795, when Girona, Cardona, Ausona and Urgell were united into the new Spanish March, within the old duchy of Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

.

In 797, Barcelona, the greatest city of the region, fell to the Franks when Zeid, its governor, rebelled against Cordova and, failing, handed it to them. The Umayyad authority recaptured it in 799. However, Louis of Aquitaine marched the entire army of his kingdom over the Pyrenees and besieged it for two years, wintering there from 800 to 801, when it capitulated. The Franks continued to press forward against the emir. They probably took Tarragona and forced the submission of Tortosa in 809. The last conquest brought them to the mouth of the Ebro and gave them raiding access to Valencia, prompting the Emir al-Hakam I to recognise their conquests in 813.

Eastern campaigns

Saxon Wars

Charlemagne was engaged in almost constant warfare throughout his reign, often at the head of his elite '' scara'' bodyguard squadrons. In the

Charlemagne was engaged in almost constant warfare throughout his reign, often at the head of his elite '' scara'' bodyguard squadrons. In the Saxon Wars

The Saxon Wars were the campaigns and insurrections of the thirty-three years from 772, when Charlemagne first entered Saxony with the intent to conquer, to 804, when the last rebellion of tribesmen was defeated. In all, 18 campaigns were fought ...

, spanning thirty years and eighteen battles, he conquered Saxonia and proceeded to convert it to Christianity.

The Germanic Saxons were divided into four subgroups in four regions. Nearest to Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

was Westphalia and farthest away was Eastphalia. Between them was Engria

Angria or Angaria (german: Engern, ) is a historical region in the present-day German states of Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia. The chronicler Widukind of Corvey in his ''Res gestae saxonicae sive annalium libri tres'' denoted it as ...

and north of these three, at the base of the Jutland peninsula, was Nordalbingia.

In his first campaign, in 773, Charlemagne forced the Engrians to submit and cut down an Irminsul

An Irminsul (Old Saxon 'great pillar') was a sacred, pillar-like object attested as playing an important role in the Germanic paganism of the Saxons. Medieval sources describe how an Irminsul was destroyed by Charlemagne during the Saxon Wars. A ...

pillar near Paderborn. The campaign was cut short by his first expedition to Italy. He returned in 775, marching through Westphalia and conquering the Saxon fort at Sigiburg

The Sigiburg was a Saxon hillfort in Western Germany, overlooking the River Ruhr near its confluence with the River Lenne. The ruins of the later Hohensyburg castle now stand on the site, which is in Syburg, a neighbourhood in the Hörde distric ...

. He then crossed Engria, where he defeated the Saxons again. Finally, in Eastphalia, he defeated a Saxon force, and its leader Hessi converted to Christianity. Charlemagne returned through Westphalia, leaving encampments at Sigiburg and Eresburg

The Eresburg is the largest, well-known (Old) Saxon refuge castle (''Volksburg'') and was located in the area of the present German village of Obermarsberg in the borough of Marsberg in the county of Hochsauerlandkreis. It was a hill castle buil ...

, which had been important Saxon bastions. He then controlled Saxony with the exception of Nordalbingia, but Saxon resistance had not ended.

Following his subjugation of the Dukes of Friuli and Spoleto, Charlemagne returned rapidly to Saxony in 776, where a rebellion had destroyed his fortress at Eresburg. The Saxons were once again defeated, but their main leader, Widukind, escaped to Denmark, his wife's home. Charlemagne built a new camp at Karlstadt. In 777, he called a national diet at Paderborn to integrate Saxony fully into the Frankish kingdom. Many Saxons were baptised as Christians.

In the summer of 779, he again invaded Saxony and reconquered Eastphalia, Engria and Westphalia. At a diet near Lippe, he divided the land into missionary districts and himself assisted in several mass baptisms (780). He then returned to Italy and, for the first time, the Saxons did not immediately revolt. Saxony was peaceful from 780 to 782.

He returned to Saxony in 782 and instituted a code of law and appointed counts, both Saxon and Frank. The laws were draconian on religious issues; for example, the '' Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae'' prescribed death to Saxon pagans who refused to convert to Christianity. This led to renewed conflict. That year, in autumn, Widukind returned and led a new revolt. In response, at Verden Verden can refer to:

* Verden an der Aller, a town in Lower Saxony, Germany

* Verden, Oklahoma, a small town in the USA

* Verden (district), a district in Lower Saxony, Germany

* Diocese of Verden (768–1648), a former diocese of the Catholic Chur ...

in Lower Saxony, Charlemagne is recorded as having ordered the execution of 4,500 Saxon prisoners by beheading, known as the Massacre of Verden ("Verdener Blutgericht"). The killings triggered three years of renewed bloody warfare. During this war, the East Frisia

East Frisia or East Friesland (german: Ostfriesland; ; stq, Aastfräislound) is a historic region in the northwest of Lower Saxony, Germany. It is primarily located on the western half of the East Frisian peninsula, to the east of West Frisia ...

ns between the Lauwers and the Weser joined the Saxons in revolt and were finally subdued. The war ended with Widukind accepting baptism. The Frisians afterwards asked for missionaries to be sent to them and a bishop of their own nation, Ludger

Ludger ( la, Ludgerus; also Lüdiger or Liudger) (born at Zuilen near Utrecht 742; died 26 March 809 at Billerbeck) was a missionary among the Frisians and Saxons, founder of Werden Abbey and the first Bishop of Münster in Westphalia. He has ...

, was sent. Charlemagne also promulgated a law code, the ''Lex Frisonum ''Lex Frisionum'', the "Law Code of the Frisians", was recorded in Latin during the reign of Charlemagne, after the year 785, when the Frankish conquest of Frisia was completed by the final defeat of the Saxon rebel leader Widukind. The law code co ...

'', as he did for most subject peoples.

Thereafter, the Saxons maintained the peace for seven years, but in 792 Westphalia again rebelled. The Eastphalians and Nordalbingians joined them in 793, but the insurrection was unpopular and was put down by 794. An Engrian rebellion followed in 796, but the presence of Charlemagne, Christian Saxons and Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

quickly crushed it. The last insurrection occurred in 804, more than thirty years after Charlemagne's first campaign against them, but also failed. According to Einhard:

Submission of Bavaria

By 774, Charlemagne had invaded the

By 774, Charlemagne had invaded the Kingdom of Lombardy The Kingdom of Lombardy could refer to:

*Kingdom of the Lombards (568–774), the independent state

*Kingdom of Italy (Holy Roman Empire) (855–1801), state of the Holy Roman Empire

*Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia (1815–1866), state of the Austri ...

, and he later annexed the Lombardian territories and assumed its crown, placing the Papal States under Frankish protection.[Historical Atlas of Knights and Castles, Cartographica, Dr Ian Barnes, 2007 pp. 30, 31] The Duchy of Spoleto

The Duchy of Spoleto (, ) was a Lombard territory founded about 570 in central Italy by the Lombard ''dux'' Faroald. Its capital was the city of Spoleto.

Lombards

The Lombards had invaded Italy in 568 AD and conquered much of it, establishing ...

south of Rome was acquired in 774, while in the central western parts of Europe, the Duchy of Bavaria was absorbed and the Bavarian policy continued of establishing tributary marches, (borders protected in return for tribute or taxes) among the Slavic Serbs and Czechs. The remaining power confronting the Franks in the east were the Avars. However, Charlemagne acquired other Slavic areas, including Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, Moravia, Austria and Croatia.synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

of Frankfurt; he formally handed over to the king all of the rights he had held. Bavaria was subdivided into Frankish counties, as had been done with Saxony.

Avar campaigns

In 788, the Avars, an Asian nomadic group that had settled down in what is today Hungary (Einhard called them Huns), invaded Friuli and Bavaria. Charlemagne was preoccupied with other matters until 790 when he marched down the Danube and ravaged Avar territory to the Győr. A Lombard army under Pippin then marched into the valley and ravaged Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

. The campaigns ended when the Saxons revolted again in 792.

For the next two years, Charlemagne was occupied, along with the Slavs, against the Saxons. Pippin and Duke Eric of Friuli continued, however, to assault the Avars' ring-shaped strongholds. The great Ring of the Avars, their capital fortress, was taken twice. The booty was sent to Charlemagne at his capital, Aachen, and redistributed to his followers and to foreign rulers, including King Offa of Mercia

Offa (died 29 July 796 AD) was List of monarchs of Mercia, King of Mercia, a kingdom of History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa of Mercia, Eowa, Offa came to ...

. Soon the Avar tuduns had lost the will to fight and travelled to Aachen to become vassals to Charlemagne and to become Christians. Charlemagne accepted their surrender and sent one native chief, baptised Abraham, back to Avaria with the ancient title of khagan

Khagan or Qaghan (Mongolian:; or ''Khagan''; otk, 𐰴𐰍𐰣 ), or , tr, Kağan or ; ug, قاغان, Qaghan, Mongolian Script: ; or ; fa, خاقان ''Khāqān'', alternatively spelled Kağan, Kagan, Khaghan, Kaghan, Khakan, Khakhan ...

. Abraham kept his people in line, but in 800, the Bulgarians under Khan Krum attacked the remains of the Avar state.

In 803, Charlemagne sent a Bavarian army into Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

, defeating and bringing an end to the Avar confederation.Magyars

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic ...

in 899–900.

Northeast Slav expeditions

In 789, in recognition of his new pagan neighbours, the Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, Charlemagne marched an Austrasian-Saxon army across the Elbe into Obotrite territory. The Slavs ultimately submitted, led by their leader Witzin. Charlemagne then accepted the surrender of the Veleti under Dragovit and demanded many hostages. He also demanded permission to send missionaries into this pagan region unmolested. The army marched to the Baltic before turning around and marching to the Rhine, winning much booty with no harassment. The tributary Slavs became loyal allies. In 795, when the Saxons broke the peace, the Abotrites and Veleti rebelled with their new ruler against the Saxons. Witzin died in battle and Charlemagne avenged him by harrying the Eastphalians on the Elbe. Thrasuco, his successor, led his men to conquest over the Nordalbingians and handed their leaders over to Charlemagne, who honoured him. The Abotrites remained loyal until Charles' death and fought later against the Danes.

Southeast Slav expeditions

When Charlemagne incorporated much of Central Europe, he brought the Frankish state face to face with the Avars and Slavs in the southeast.Duchy of Croatia

The Duchy of Croatia (; also Duchy of the Croats, hr , Kneževina Hrvata; ) was a medieval state that was established by White Croats who migrated into the area of the former Roman province of Dalmatia 7th century CE. Throughout its existence ...

. While fighting the Avars, the Franks had called for their support.[

The Frankish commander Eric of Friuli wanted to extend his dominion by conquering the Littoral Croat Duchy. During that time, Dalmatian Croatia was ruled by Duke Višeslav of Croatia. In the Battle of Trsat, the forces of Eric fled their positions and were routed by the forces of Višeslav.]Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

to the west of the Avar khaganate: the Carantania

Carantania, also known as Carentania ( sl, Karantanija, german: Karantanien, in Old Slavic '), was a Slavic principality that emerged in the second half of the 7th century, in the territory of present-day southern Austria and north-eastern ...

ns and Carniola

Carniola ( sl, Kranjska; , german: Krain; it, Carniola; hu, Krajna) is a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region sti ...

ns. These people were subdued by the Lombards and Bavarii and made tributaries, but were never fully incorporated into the Frankish state.

Imperium

Coronation

In 799,

In 799, Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

had been assaulted by some of the Romans, who tried to put out his eyes and tear out his tongue. Leo escaped and fled to Charlemagne at Paderborn.Empress Irene

Irene of Athens ( el, Εἰρήνη, ; 750/756 – 9 August 803), surname Sarantapechaina (), was Byzantine empress consort to Emperor Leo IV from 775 to 780, regent during the childhood of their son Constantine VI from 780 until 790, co-ruler ...

of Constantinople:

Charlemagne's coronation as Emperor, though intended to represent the continuation of the unbroken line of Emperors from Augustus to Constantine VI, had the effect of setting up two separate (and often opposing) Empires and two separate claims to imperial authority. It led to war in 802, and for centuries to come, the Emperors of both West and East would make competing claims of sovereignty over the whole.

Einhard says that Charlemagne was ignorant of the Pope's intent and did not want any such coronation:

A number of modern scholars, however, suggest that Charlemagne was indeed aware of the coronation; certainly, he cannot have missed the bejewelled crown waiting on the altar when he came to pray—something even contemporary sources support.

Charlemagne's coronation as Emperor, though intended to represent the continuation of the unbroken line of Emperors from Augustus to Constantine VI, had the effect of setting up two separate (and often opposing) Empires and two separate claims to imperial authority. It led to war in 802, and for centuries to come, the Emperors of both West and East would make competing claims of sovereignty over the whole.

Einhard says that Charlemagne was ignorant of the Pope's intent and did not want any such coronation:

A number of modern scholars, however, suggest that Charlemagne was indeed aware of the coronation; certainly, he cannot have missed the bejewelled crown waiting on the altar when he came to pray—something even contemporary sources support.

Debate

Historians have debated for centuries whether Charlemagne was aware before the coronation of the Pope's intention to crown him Emperor (Charlemagne declared that he would not have entered Saint Peter's had he known, according to chapter twenty-eight of Einhard's ''Vita Karoli Magni''), but that debate obscured the more significant question of ''why'' the Pope granted the title and why Charlemagne accepted it.

Collins points out " at the motivation behind the acceptance of the imperial title was a romantic and antiquarian interest in reviving the Roman Empire is highly unlikely." For one thing, such romance would not have appealed either to Franks or Roman Catholics at the turn of the ninth century, both of whom viewed the Classical heritage of the Roman Empire with distrust. The Franks took pride in having "fought against and thrown from their shoulders the heavy yoke of the Romans" and "from the knowledge gained in baptism, clothed in gold and precious stones the bodies of the holy martyrs whom the Romans had killed by fire, by the sword and by wild animals", as Pepin III described it in a law of 763 or 764.

Furthermore, the new title—carrying with it the risk that the new emperor would "make drastic changes to the traditional styles and procedures of government" or "concentrate his attentions on Italy or on Mediterranean concerns more generally"—risked alienating the Frankish leadership.

For both the Pope and Charlemagne, the Roman Empire remained a significant power in European politics at this time. The Byzantine Empire, based in Constantinople, continued to hold a substantial portion of Italy, with borders not far south of Rome. Charles' sitting in judgment of the Pope could be seen as usurping the prerogatives of the Emperor in Constantinople:

For the Pope, then, there was "no living Emperor at that time" though Henri Pirenne disputes this saying that the coronation "was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople". Nonetheless, the Pope took the extraordinary step of creating one. The papacy had since 727 been in conflict with Irene's predecessors in Constantinople over a number of issues, chiefly the continued Byzantine adherence to the doctrine of iconoclasm, the destruction of Christian images; while from 750, the secular power of the Byzantine Empire in central Italy had been nullified.

Historians have debated for centuries whether Charlemagne was aware before the coronation of the Pope's intention to crown him Emperor (Charlemagne declared that he would not have entered Saint Peter's had he known, according to chapter twenty-eight of Einhard's ''Vita Karoli Magni''), but that debate obscured the more significant question of ''why'' the Pope granted the title and why Charlemagne accepted it.

Collins points out " at the motivation behind the acceptance of the imperial title was a romantic and antiquarian interest in reviving the Roman Empire is highly unlikely." For one thing, such romance would not have appealed either to Franks or Roman Catholics at the turn of the ninth century, both of whom viewed the Classical heritage of the Roman Empire with distrust. The Franks took pride in having "fought against and thrown from their shoulders the heavy yoke of the Romans" and "from the knowledge gained in baptism, clothed in gold and precious stones the bodies of the holy martyrs whom the Romans had killed by fire, by the sword and by wild animals", as Pepin III described it in a law of 763 or 764.

Furthermore, the new title—carrying with it the risk that the new emperor would "make drastic changes to the traditional styles and procedures of government" or "concentrate his attentions on Italy or on Mediterranean concerns more generally"—risked alienating the Frankish leadership.

For both the Pope and Charlemagne, the Roman Empire remained a significant power in European politics at this time. The Byzantine Empire, based in Constantinople, continued to hold a substantial portion of Italy, with borders not far south of Rome. Charles' sitting in judgment of the Pope could be seen as usurping the prerogatives of the Emperor in Constantinople:

For the Pope, then, there was "no living Emperor at that time" though Henri Pirenne disputes this saying that the coronation "was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople". Nonetheless, the Pope took the extraordinary step of creating one. The papacy had since 727 been in conflict with Irene's predecessors in Constantinople over a number of issues, chiefly the continued Byzantine adherence to the doctrine of iconoclasm, the destruction of Christian images; while from 750, the secular power of the Byzantine Empire in central Italy had been nullified.