Chaim Weizmann on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

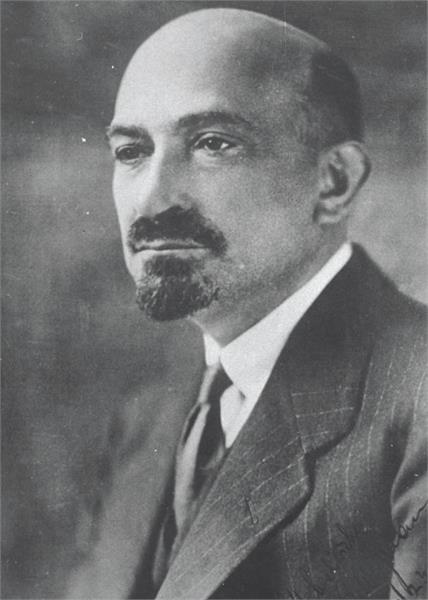

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist,

His father was a timber merchant.Brown, G.I. (1998) ''The Big Bang: A History of Explosives'' Sutton Publishing p.144 From ages four to eleven, he attended a traditional cheder, or Jewish religious primary school, where he also studied

Maria Weizmann was a doctor who was arrested as part of Stalin's fabricated " Doctors' plot" in 1952 and was sentenced to five years' imprisonment in Weizmann married Vera Khatzmann, with whom he had two sons. The elder son, Benjamin (Benjie) Weizmann (1907–1980), settled in

Weizmann married Vera Khatzmann, with whom he had two sons. The elder son, Benjamin (Benjie) Weizmann (1907–1980), settled in

That year, he joined the Organic Chemistry Department at the

While serving as a lecturer in

While serving as a lecturer in

Concurrently, Weizmann devoted himself to the establishment of a scientific institute for basic research in the vicinity of his estate in the town of Rehovot. Weizmann saw great promise in science as a means to bring peace and prosperity to the area. As stated in his own words "I trust and feel sure in my heart that science will bring to this land both peace and a renewal of its youth, creating here the springs of a new spiritual and material life. ..I speak of both science for its own sake and science as a means to an end."

His efforts led in 1934 to the creation of the Daniel Sieff Research Institute (later renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science), which was financially supported by an endowment by Israel Sieff in memory of his late son. Weizmann actively conducted research in the laboratories of this institute, primarily in the field of

Concurrently, Weizmann devoted himself to the establishment of a scientific institute for basic research in the vicinity of his estate in the town of Rehovot. Weizmann saw great promise in science as a means to bring peace and prosperity to the area. As stated in his own words "I trust and feel sure in my heart that science will bring to this land both peace and a renewal of its youth, creating here the springs of a new spiritual and material life. ..I speak of both science for its own sake and science as a means to an end."

His efforts led in 1934 to the creation of the Daniel Sieff Research Institute (later renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science), which was financially supported by an endowment by Israel Sieff in memory of his late son. Weizmann actively conducted research in the laboratories of this institute, primarily in the field of

'This Founding Father of the Jewish State Was a Serial Cheater Who Hated Israel,'

Zionists believed that anti-Semitism led directly to the need for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Weizmann first visited Jerusalem in 1907, and while there, he helped organize the Palestine Land Development Company as a practical means of pursuing the Zionist dream, and to found the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Although Weizmann was a strong advocate for "those governmental grants which are necessary to the achievement of the Zionist purpose" in Palestine, as stated at Basel, he persuaded many Jews not to wait for future events,

During World War I, at around the same time he was appointed Director of the British Admiralty's laboratories, Weizmann, in a conversation with

Zionists believed that anti-Semitism led directly to the need for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Weizmann first visited Jerusalem in 1907, and while there, he helped organize the Palestine Land Development Company as a practical means of pursuing the Zionist dream, and to found the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Although Weizmann was a strong advocate for "those governmental grants which are necessary to the achievement of the Zionist purpose" in Palestine, as stated at Basel, he persuaded many Jews not to wait for future events,

During World War I, at around the same time he was appointed Director of the British Admiralty's laboratories, Weizmann, in a conversation with

On 3 January 1919, Weizmann met Hashemite Prince Faisal to sign the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement attempting to establish the legitimate existence of the state of Israel. At the end of the month, the

On 3 January 1919, Weizmann met Hashemite Prince Faisal to sign the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement attempting to establish the legitimate existence of the state of Israel. At the end of the month, the  After 1920, he assumed leadership in the World Zionist Organization, creating local branches in Berlin serving twice (1920–31, 1935–46) as president of the World Zionist Organization. Unrest amongst Arab antagonism to a Jewish presence in Palestine increased, erupting into riots. Weizmann remained loyal to Britain, tried to shift the blame onto dark forces. The French were commonly blamed for discontent, as scapegoats for Imperial liberalism. Zionists began to believe racism existed within the administration, which remained inadequately policed.

In 1921, Weizmann went along with

After 1920, he assumed leadership in the World Zionist Organization, creating local branches in Berlin serving twice (1920–31, 1935–46) as president of the World Zionist Organization. Unrest amongst Arab antagonism to a Jewish presence in Palestine increased, erupting into riots. Weizmann remained loyal to Britain, tried to shift the blame onto dark forces. The French were commonly blamed for discontent, as scapegoats for Imperial liberalism. Zionists began to believe racism existed within the administration, which remained inadequately policed.

In 1921, Weizmann went along with

Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in J ...

leader and Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

i statesman who served as president of the Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization ( he, הַהִסְתַּדְּרוּת הַצִּיּוֹנִית הָעוֹלָמִית; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the ...

and later as the first president of Israel

The president of the State of Israel ( he, נְשִׂיא מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, Nesi Medinat Yisra'el, or he, נְשִׂיא הַמְדִינָה, Nesi HaMedina, President of the State) is the head of state of Israel. The posi ...

. He was elected on 16 February 1949, and served until his death in 1952. Weizmann was fundamental in obtaining the Balfour Declaration and later convincing the United States government to recognize the newly formed State of Israel.

As a biochemist

Biochemists are scientists who are trained in biochemistry. They study chemical processes and chemical transformations in living organisms. Biochemists study DNA, proteins and cell parts. The word "biochemist" is a portmanteau of "biological che ...

, Weizmann is considered to be the 'father' of industrial fermentation. He developed the acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation process, which produces acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscible wi ...

, n-butanol and ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a h ...

through bacterial fermentation. His acetone production method was of great importance in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants for the British war industry during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. He founded the Sieff Research Institute in Rehovot (later renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science in his honor), and was instrumental in the establishment of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Biography

Chaim Weizmann was born in the village of Motal, located in what is nowBelarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

and at that time was part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

. He was the third of 15 children born to Oizer and Rachel (Czemerinsky) Weizmann.Chaim Weizmann Of Israel Is DeadHis father was a timber merchant.Brown, G.I. (1998) ''The Big Bang: A History of Explosives'' Sutton Publishing p.144 From ages four to eleven, he attended a traditional cheder, or Jewish religious primary school, where he also studied

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

. At the age of 11, he entered high school in Pinsk

Pinsk ( be, Пі́нск; russian: Пи́нск ; Polish: Pińsk; ) is a city located in the Brest Region of Belarus, in the Polesia region, at the confluence of the Pina River and the Pripyat River. The region was known as the Marsh of Pi ...

, where he displayed a talent for science, especially chemistry. While in Pinsk, he became active in the Hovevei Zion

Hovevei Zion ( he, חובבי ציון, lit. '' hose who areLovers of Zion''), also known as Hibbat Zion ( he, חיבת ציון), refers to a variety of organizations which were founded in 1881 in response to the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russi ...

movement. He graduated with honors in 1892.

In 1892, Weizmann left for Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

to study chemistry at the Polytechnic Institute of Darmstadt

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it th ...

. To earn a living, he worked as a Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

teacher at an Orthodox Jewish

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses ...

boarding school. In 1894, he moved to Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

to study at the Technische Hochschule Berlin

The Technical University of Berlin (official name both in English and german: link=no, Technische Universität Berlin, also known as TU Berlin and Berlin Institute of Technology) is a public research university located in Berlin, Germany. It ...

.

While in Berlin, he joined a circle of Zionist intellectuals. In 1897, he moved to Switzerland to complete his studies at the University of Fribourg. In 1898, he attended the Second Zionist Congress in Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS) ...

. That year he became engaged to Sophia Getzowa

Sophia Getzowa ( he, סופיה גצובה, 10 January 1872 (O.S.)/23 January 1872 (N. S.) - 11(12) July 1946) was a Belarusian-born pathologist and scientist in Mandatory Palestine. She grew up in a Jewish shtetl in Belarus and during her medi ...

. Getzowa and Weizmann were together for four years before Weizmann, who became romantically involved with Vera Khatzman in 1900, confessed to Getzowa that he was seeing another woman. He did not tell the family he was leaving Getzowa until 1903. His fellow students held a mock trial and ruled that Weitzman should uphold his commitment and marry Getzowa, even if he later divorced her. Weizmann ignored their advice.

Of Weizmann's fifteen siblings, ten immigrated to Palestine. Two also became chemists; Anna (Anushka) Weizmann worked in his Daniel Sieff Research Institute lab, registering several patents in her name. His brother, Moshe Weizmann, was the head of the Chemistry Faculty at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Two siblings remained in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

following the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

: a brother, Shmuel, and a sister, Maria (Masha). Shmuel Weizmann was a dedicated Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

and member of the anti-Zionist Bund movement. During the Stalinist "Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

", he was arrested for alleged espionage and Zionist activity, and executed in 1939. His fate became known to his wife and children only in 1955.Family TrialsMaria Weizmann was a doctor who was arrested as part of Stalin's fabricated " Doctors' plot" in 1952 and was sentenced to five years' imprisonment in

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part o ...

. She was released following Stalin's death in 1953, and was permitted to emigrate to Israel along with her husband in 1956. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, another sister, Minna Weizmann, was the lover of a German spy (and later Nazi diplomat), Kurt Prüfer, and worked as a spy for Germany in Cairo, Egypt (then a wartime British protectorate) in 1915. Minna was outed as a spy during a trip to Italy, and was deported back to Egypt to be sent to a British POW camp. Back in Cairo, she successfully persuaded the consul of the Russian Czar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

to provide her safe passage out, and en route to Russia, she managed to reconnect with Prüfer via a German consulate. Minna was never formally charged with espionage, survived the war, and would eventually return to Palestine to work for the medical service of the Zionist women's organization, Hadassah

Hadassah () means myrtle in Hebrew. It is given as the Hebrew name of Esther in the Hebrew Bible.

Hadassah may also refer to:

* Hadassah (dancer) (1909–1992), Jerusalem-born American dancer and choreographer

* Hadassah Lieberman (born 1948) ...

.

Weizmann married Vera Khatzmann, with whom he had two sons. The elder son, Benjamin (Benjie) Weizmann (1907–1980), settled in

Weizmann married Vera Khatzmann, with whom he had two sons. The elder son, Benjamin (Benjie) Weizmann (1907–1980), settled in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and became a dairy farmer.

The younger one, Flight Lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth countries. It has a NATO rank code of OF-2. Flight lieutenant is abbreviated as Flt Lt in the Indi ...

Michael Oser Weizmann (1916–1942), fought in the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. While serving as a pilot in No. 502 Squadron RAF, he was killed when his plane was shot down over the Bay of Biscay in February 1942. His body was never found and he was listed as "missing". His father never fully accepted his death and made a provision in his will, in case he returned. He is one of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

's air force casualties without a known grave commemorated at the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede in Surrey, England.

His nephew Ezer Weizman, son of his brother Yechiel, a leading Israeli agronomist, became commander of the Israeli Air Force

The Israeli Air Force (IAF; he, זְרוֹעַ הָאֲוִיר וְהֶחָלָל, Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal, tl, "Air and Space Arm", commonly known as , ''Kheil HaAvir'', "Air Corps") operates as the aerial warfare branch of the Israel Defense ...

and also served as President of Israel

The president of the State of Israel ( he, נְשִׂיא מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, Nesi Medinat Yisra'el, or he, נְשִׂיא הַמְדִינָה, Nesi HaMedina, President of the State) is the head of state of Israel. The posi ...

.

Chaim Weizmann is buried beside his wife in the garden of his home at the Weizmann estate, located on the grounds of the Weizmann Institute

The Weizmann Institute of Science ( he, מכון ויצמן למדע ''Machon Vaitzman LeMada'') is a public research university in Rehovot, Israel, established in 1934, 14 years before the State of Israel. It differs from other Israeli un ...

, named after him.

Academic and scientific career

In 1899, he was awarded aPhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

in organic chemistry.Biography of Chaim WeizmannThat year, he joined the Organic Chemistry Department at the

University of Geneva

The University of Geneva (French: ''Université de Genève'') is a public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded in 1559 by John Calvin as a theological seminary. It remained focused on theology until the 17th centur ...

. In 1901, he was appointed assistant lecturer at the University of Geneva

The University of Geneva (French: ''Université de Genève'') is a public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded in 1559 by John Calvin as a theological seminary. It remained focused on theology until the 17th centur ...

.

In 1904, he moved to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

to teach at the Chemistry Department of the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The university owns and operates majo ...

as a senior lecturer. He joined Clayton Aniline Company

The Clayton Aniline Company Ltd. was a British manufacturer of dyestuffs, founded in 1876 by Charles Dreyfus in Clayton, Manchester.

Early history

Charles Dreyfus was a French emigrant chemist and entrepreneur, who founded the Clayton Aniline ...

in 1905 where the director Charles Dreyfus

Charles Dreyfus (b. Alsace, 1848 - d. Menton, France, 11 December 1935) was President of the Manchester Zionist Society, a member of Manchester City Council and a leading figure in the East Manchester Conservative Association during the time th ...

introduced him to Arthur Balfour, then Prime Minister.

In 1910, he became a British citizen when Winston Churchill as Home Secretary signed his papers, and held his British nationality until 1948, when he renounced it to assume his position as President of Israel. Chaim Weizmann and his family lived in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of City of Salford, Salford to ...

for about 30 years (1904–1934), although they temporarily lived at 16 Addison Road in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

In Britain, he was known as Charles Weizmann, a name under which he registered about 100 research patents. At the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, it was discovered that the SS had compiled a list in 1940 of over 2,800 people living in Britain, which included Weizmann, who were to have been immediately arrested after an invasion of Britain had the ultimately abandoned Operation Sea Lion been successful.

Discovery of synthetic acetone

While serving as a lecturer in

While serving as a lecturer in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of City of Salford, Salford to ...

he became known for discovering how to use bacterial fermentation to produce large quantities of desired substances. He is considered to be the father of industrial fermentation. He used the bacterium ''Clostridium'' ''acetobutylicum'' (the ''Weizmann organism'') to produce acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscible wi ...

. Acetone was used in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants critical to the Allied war effort (see Royal Navy Cordite Factory, Holton Heath). Weizmann transferred the rights to the manufacture of acetone to the Commercial Solvents Corporation

Commercial Solvents Corporation (CSC) was an American chemical and biotechnology company created in 1919.

History

The Commercial Solvents Corporation was established at the end of World War I; earning distinction as the pioneer producer of aceton ...

in exchange for royalties.

Winston Churchill became aware of the possible use of Weizmann's discovery in early 1915, and David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

, as Minister of Munitions, joined Churchill in encouraging Weizmann's development of the process. Pilot plant development of laboratory procedures was completed in 1915 at the J&W Nicholson & Co

''J&W Nicholson & Co'' was a London-based wine and spirits company founded by two brothers from the famous Nicholson gin family: John Nicholson (1778-1846) and William Nicholson (1780-1857) based in Clerkenwell.

History

John and William Nicholson ...

gin factory in Bow, London

Bow () is an area of East London within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is primarily a built-up and mostly residential area and is east of Charing Cross.

It was in the traditional county of Middlesex but became part of the County o ...

, so industrial scale production of acetone could begin in six British distilleries requisitioned for the purpose in early 1916. The effort produced 30,000 tonnes of acetone during the war, although a national collection of horse-chestnuts was required when supplies of maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn ( North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. ...

were inadequate for the quantity of starch needed for fermentation. The importance of Weizmann's work gave him favour in the eyes of the British Government, this allowed Weizmann to have access to senior Cabinet members and utilise this time to represent Zionist aspirations.

After the Shell Crisis of 1915 during World War I, Weizmann was director of the British Admiralty laboratories from 1916 until 1919. In April 1918 at the head of the Jewish Commission

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

, he returned to Palestine to look for "rare minerals" for the British war effort in the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

. Weizmann's attraction for British Liberalism enabled Lloyd George's influence at the Ministry of Munitions to do a financial and industrial deal with Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) to seal the future of the Zionist homeland. Tirelessly energetic Weizmann entered London again in later October to speak for a solid hour with the Prime Minister, propped by ''The Guardian'' and his Manchester friends. At another conference on 21 February 1919 at Euston Hotel the peace envoy, Lord Bryce was reassured by the pledges against international terrorism, for currency regulation and fiscal controls.

Establishment of scientific research institutes

Concurrently, Weizmann devoted himself to the establishment of a scientific institute for basic research in the vicinity of his estate in the town of Rehovot. Weizmann saw great promise in science as a means to bring peace and prosperity to the area. As stated in his own words "I trust and feel sure in my heart that science will bring to this land both peace and a renewal of its youth, creating here the springs of a new spiritual and material life. ..I speak of both science for its own sake and science as a means to an end."

His efforts led in 1934 to the creation of the Daniel Sieff Research Institute (later renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science), which was financially supported by an endowment by Israel Sieff in memory of his late son. Weizmann actively conducted research in the laboratories of this institute, primarily in the field of

Concurrently, Weizmann devoted himself to the establishment of a scientific institute for basic research in the vicinity of his estate in the town of Rehovot. Weizmann saw great promise in science as a means to bring peace and prosperity to the area. As stated in his own words "I trust and feel sure in my heart that science will bring to this land both peace and a renewal of its youth, creating here the springs of a new spiritual and material life. ..I speak of both science for its own sake and science as a means to an end."

His efforts led in 1934 to the creation of the Daniel Sieff Research Institute (later renamed the Weizmann Institute of Science), which was financially supported by an endowment by Israel Sieff in memory of his late son. Weizmann actively conducted research in the laboratories of this institute, primarily in the field of organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clay ...

. He offered the post of director of the institute to Nobel Prize laureate Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber (; 9 December 186829 January 1934) was a German chemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his invention of the Haber–Bosch process, a method used in industry to synthesize ammonia from nitrogen gas and hydroge ...

, but took over the directorship himself after Haber's death en route to Palestine.

During World War II, he was an honorary adviser to the British Ministry of Supply and did research on synthetic rubber

A synthetic rubber is an artificial elastomer. They are polymers synthesized from petroleum byproducts. About 32-million metric tons of rubbers are produced annually in the United States, and of that amount two thirds are synthetic. Synthetic rubbe ...

and high-octane gasoline.

Zionist activism

Weizmann was absent from the first Zionist conference, held in 1897 inBasel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS) ...

, Switzerland, because of travel problems, but he attended the Second Zionist Congress in 1898 and each one thereafter. Beginning in 1901, he lobbied for the founding of a Jewish institution of higher learning in Palestine. Together with Martin Buber and Berthold Feiwel

Berthold or Berchtold is a Germanic given name and surname. It is derived from two elements, ''berht'' meaning "bright" and ''wald'' meaning "(to) rule". It may refer to:

*Bertholdt Hoover, a fictional character in the anime/manga series ''Attack o ...

, he presented a document to the Fifth Zionist Congress highlighting this need especially in the fields of science and engineering. This idea would later be crystallized in the foundation of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology

The Technion – Israel Institute of Technology ( he, הטכניון – מכון טכנולוגי לישראל) is a public research university located in Haifa, Israel. Established in 1912 under the dominion of the Ottoman Empire, the Technio ...

in 1912.

Weizmann met Arthur Balfour, the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Prime Minister who was MP for East Manchester, during one of Balfour's electoral campaigns in 1905–1906. Balfour supported the concept of a Jewish homeland, but felt that there would be more support among politicians for the then-current offer in Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The south ...

, called the British Uganda Programme. Following mainstream Zionist rejection of that proposal, Weizmann was credited later with persuading Balfour, by then the Foreign Secretary during the First World War, for British support to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine, the original Zionist aspiration. The story goes that Weizmann asked Balfour, "Would you give up London to live in Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a province in western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on the south by the U.S. states of Montana and North ...

?" When Balfour replied that the British had always lived in London, Weizmann responded, "Yes, and we lived in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

when London was still a marsh." Nevertheless, this had not prevented naturalization as a British subject in 1910 with the help of '' haham'' Moses Gaster, who asked for papers from Herbert Samuel, the minister.

Weizmann revered Britain but relentlessly pursued Jewish freedom. He was head of the Democratic Fraction, a group of Zionist radicals who posed a challenge to Herzlian political Zionism. Israel Sieff described him as "pre-eminently what the Jewish people call folks-mensch...a man of the people, of the masses, not of a elite". His most recent biographers challenge this, describing him as a blatant elitist, disgusted by the masses, coldly aloof from his family, callous with friends if they did not support him, despondently alienated from Palestine, where he lived only with reluctance, and repelled by the Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe there.Ofer Aderet'This Founding Father of the Jewish State Was a Serial Cheater Who Hated Israel,'

Haaretz

''Haaretz'' ( , originally ''Ḥadshot Haaretz'' – , ) is an Israeli newspaper. It was founded in 1918, making it the longest running newspaper currently in print in Israel, and is now published in both Hebrew and English in the Berliner ...

12 September 2020.

Gradually Weizmann set up a separate following from Moses Gaster and L.J. Greenberg in London. Manchester became an important Zionist center in Britain. Weizmann was mentor to Harry Sacher, Israel Sieff and Simon Marks (founders of Marks & Spencer), and formed a friendship with Asher Ginzberg

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zi ...

, a writer who pushed for Zionist inclusivity and urged against "repressive cruelty" to the Arabs. He regularly traveled by train to London to discuss spiritual and cultural Zionism with Ginzberg, whose pen name was Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state ...

. He stayed at Ginzberg's home in Hampstead, whence he lobbied Whitehall, beyond his job as Director of the Admiralty for Manchester.

Zionists believed that anti-Semitism led directly to the need for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Weizmann first visited Jerusalem in 1907, and while there, he helped organize the Palestine Land Development Company as a practical means of pursuing the Zionist dream, and to found the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Although Weizmann was a strong advocate for "those governmental grants which are necessary to the achievement of the Zionist purpose" in Palestine, as stated at Basel, he persuaded many Jews not to wait for future events,

During World War I, at around the same time he was appointed Director of the British Admiralty's laboratories, Weizmann, in a conversation with

Zionists believed that anti-Semitism led directly to the need for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Weizmann first visited Jerusalem in 1907, and while there, he helped organize the Palestine Land Development Company as a practical means of pursuing the Zionist dream, and to found the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Although Weizmann was a strong advocate for "those governmental grants which are necessary to the achievement of the Zionist purpose" in Palestine, as stated at Basel, he persuaded many Jews not to wait for future events,

During World War I, at around the same time he was appointed Director of the British Admiralty's laboratories, Weizmann, in a conversation with David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

, suggested the strategy of the British campaign against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. From 1914, "a benevolent goodwill toward the Zionist idea" emerged in Britain when intelligence revealed how the Jewish Question could support imperial interests against the Ottomans. Many of Weizmann's contacts revealed the extent of the uncertainty in Palestine. From 1914 to 1918, Weizmann developed his political skills mixing easily in powerful circles. On 7 and 8 November 1914, he had a meeting with Dorothy de Rothschild. Her husband James de Rothschild was serving with the French Army, but she was unable to influence her cousinhood to Weizmann's favour. However, when Weizmanm spoke to Charles, second son of Nathan Mayer Rothschild, he approved the idea. James de Rothschild advised Weizmann seek to influence the British Government. By the time he reached Lord Robert Cecil

Edgar Algernon Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood, (14 September 1864 – 24 November 1958), known as Lord Robert Cecil from 1868 to 1923,As the younger son of a Marquess, Cecil held the courtesy title of "Lord". However, he ...

, Dr Weizmann was enthused with excitement. Cecil's personal foibles were representative of class consciousness, which the Zionists overcame through deeds rather than words. C. P. Scott, the editor of '' The Manchester Guardian'', formed a friendship with Weizmann after the two men encountered each other at a Manchester garden party in 1915. Scott described the diminutive leader asextraordinarily interesting, a rare combination of idealism and the severely practical which are the two essentials of statesmanship a perfectly clear sense conception of Jewish nationalism, an intense and burning sense of the Jew as Jew, just as strong, perhaps more so, as that of the German as German or the Englishman as Englishman, and secondly arising out of that and necessary for its satisfaction and development, his demand for a country, a home land which for him and for anyone during his view of Jewish nationality can be no other that the ancient home of his race.Scott wrote to the Liberal Party's Lloyd George who set up a meeting for a reluctant Weizmann with Herbert Samuel, President of the Local Government Board, who was now converted to Zionism. On 10 December 1914 at Whitehall, Samuel offered Weizmann a Jewish homeland complete with funded developments. Ecstatic, Weizmann returned to Westminster to arrange a meeting with Balfour, who was also on the War Council. He had first met the Conservatives in 1906, but after being moved to tears at 12 Carlton Gardens, on 12 December 1914, Balfour told Weizmann "it is a great cause and I understand it." Weizmann had another meeting in Paris with Baron Edmond Rothschild before a crucial discussion with Chancellor of the Exchequer Lloyd George, on 15 January 1915. Whilst some of the leading members of Britain's Jewish community regarded Weizmann's program with distaste, '' The Future of Palestine'', also known as the ''Samuel Memorandum'', was a watershed moment in the Great War and annexation of Palestine. Weizmann consulted several times with Samuel on the homeland policy during 1915, but H. H. Asquith, then Prime Minister, would be dead set against upsetting the balance of power on the Middle East. Attitudes were changing to "dithyrambic" opposition; but in the Cabinet, to the Samuel Memorandum, it remained implacably opposed with the exception of Lloyd George, an outspoken radical. Edwin Montagu, for example, Samuel's cousin was strenuously opposed. Weizmann did not attend the meeting of Jewry's ruling Conjoint Committee when it met the Zionist leadership on 14 April 1915. Yehiel Tschlenow had travelled from

Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

to speak at the congress. He envisioned a Jewish Community worldwide so that integration was complementary with amelioration. Zionists however had one goal only, the creation of their own state with British help.

In 1915, Weizmann also began working with Sir Mark Sykes

Colonel Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet (16 March 1879 – 16 February 1919) was an English traveller, Conservative Party politician, and diplomatic advisor, particularly with regard to the Middle East at the time of the First Wo ...

, who was looking for a member of the Jewish community for a delicate mission. He met the Armenian lawyer, James Malcolm, who already knew Sykes, and British intelligence, who were tired of the oppositional politics of Moses Gaster. "Dr Weizmann ... asked when he could meet Sir Mark Sykes ... Sir Mark fixed the appointment for the very next day, which was a Sunday." They finally met on 28 January 1917, "Dr Weizmann...should take the leading part in the negotiations", was Sykes response. Weizmann was determined to replace the Chief Rabbi as Jewish leader of Zionism. He had the "matter in hand" when he met Sokolow and Malcolm at Thatched House on Monday 5 February 1917. Moses Gaster was very reluctant to step aside. Weizmann had a considerable following, yet was not involved in the discussions with François Georges-Picot at the French embassy: a British Protectorate, he knew would not require French agreement. Furthermore, James de Rothschild proved a friend and guardian of the nascent state questioning Sykes' motivations as their dealings on Palestine were still secretive. Sokolow, Weizmann's diplomatic representative, cuttingly remarked to Picot underlining the irrelevance of the Triple Entente to French Jewry, but on 7 February 1917, the British government recognized the Zionist leader and agreed to expedite the claim. Weizmann was characteristically wishing to reward his Jewish friends for loyalty and service. News of the February Revolution (also known as the Kerensky Revolution) in Russia shattered the illusion for World Jewry. Unity for British Jewry was achieved by the Manchester Zionists. "Thus not for the first time in history, there is a community alike of interest and of sentiment between the British State and Jewish people." The Manchester Zionists published a pamphlet ''Palestine'' on 26 January 1917, which did not reflect British policy, but already Sykes looked to Weizmann's leadership when they met on 20 March 1917.

On 6 February 1917 a meeting was held at Dr Moses Gaster's house with Weizmann to discuss the results of the Picot convention in Paris. Sokolow and Weizmann pressed on with seizing leadership from Gaster; they had official recognition from the British government. At 6 Buckingham Gate on 10 February 1917 another was held, in a series of winter meetings in London. The older generation of Greenberg, Joseph Cowen and Gaster were stepping down or being passed over. "...those friends ... in close cooperation all these years", he suggested should become the EZF Council- Manchester's Sieff, Sacher and Marks, and London's Leon Simon and Samuel Tolkowsky. While the war was raging in the outside world, the Zionists prepared for an even bigger fight for the survival of their homeland. Weizmann issued a statement on 11 February 1917, and on the following day, they received news of the Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Novembe ...

take over in Petrograd. Tsarist Russia had been very anti-Semitic but incongruously this made the British government even more determined to help the Jews. Nahum Sokolow acted as Weizmann's eyes and ears in Paris on a diplomatic mission; an Entente under the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

was unsettling. The Triple Entente of Arab-Armenian-Zionist was fantastic to Weizmann leaving him cold and unenthusiastic. Nonetheless, the delegation left for Paris on 31 March 1917. One purpose of the Alliance was to strengthen the hand of Zionism in the United States.

Weizmann's relations with Balfour were intellectual and academic. He was genuinely overjoyed to convince the former Prime Minister in April 1917. Just after the U.S. President, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

, had left, the following morning, Lloyd George invited Weizmann to breakfast at which he promised Jewish support for Britain as the Jews "might be able to render more assistance than the Arabs." They discussed "International Control" the Russian Revolution and US involvement in the future of the Palestine Problem. The complexity of Arab ''desiderata'' – "facilities of colonization, communal autonomy, rights of language and establishment of a Jewish chartered company". This was followed by a meeting with Sir Edward Carson and the Conservatives (18 April) and another at Downing Street on 20 April. With the help of Philip Kerr the issue was moved up "the Agenda" to War Cabinet as a matter of urgency.

On 16 May 1917 the President of the Board of Deputies David Lindo Alexander QC co-signed a statement in the ''Times'' attacking Zionism and asserting that the Jewish Community in Britain was opposed to it. At the next meeting of the Board, on 15 June 1917, a motion of censure was proposed against the President, who said he would treat the motion as one of no confidence. When it was passed, he resigned. Although subsequent analysis has shown that the success of the motion possibly had more to do with a feeling on the part of Deputies that Lindo Alexander had failed to consult them than with a massive conversion on their part to the Zionist cause, nevertheless it had great significance outside the community. Within days of the resolution the Foreign Office sent a note to Lord Rothschild and to Weizmann asking them to submit their proposals for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The way had been opened to the Balfour Declaration issued in the following November.

Political career

On 31 October 1917, Chaim Weizmann became president of the British Zionist Federation; he worked with Arthur Balfour to obtain the Balfour Declaration. A founder of so-calledSynthetic Zionism

The principal common goal of Zionism was to establish a homeland for the Jewish people. Zionism was produced by various philosophers representing different approaches concerning the objective and path that Zionism should follow.

Political Zioni ...

, Weizmann supported grass-roots colonization efforts as well as high-level diplomatic activity. He was generally associated with the centrist General Zionists and later sided with neither Labour Zionism on the left nor Revisionist Zionism

Revisionist Zionism is an ideology developed by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who advocated a "revision" of the " practical Zionism" of David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann which was focused on the settling of ''Eretz Yisrael'' ( Land of Israel) by indepen ...

on the right. In 1917, he expressed his view of Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

in the following words,

Weizmann's personality became an issue but Weizmann had an international profile unlike his colleagues or any other British Zionist. He was President of EZF Executive Council. He was also criticized by Harry Cohen. A London delegate raised a censure motion: that Weizmann refused to condemn the regiment. In August 1917, Weizmann quit both EZF and ZPC which he had founded with his friends. Leon Simon asked Weizmann not to "give up the struggle". At the meeting on 4 September 1917, he faced some fanatical opposition. But letters of support "sobering down" opposition, and a letter from his old friend Ginzberg "a great number of people regard you as something of a symbol of Zionism".

Zionists linked Sokolow and Weizmann to Sykes. Sacher tried to get the Foreign Secretary to redraft a statement rejecting Zionism. The irony was not lost accusing the government of anti-semitism. Edwin Montagu opposed it, but Herbert Samuel and David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

favoured Zionism. Montagu did not regard Palestine as a "fit place for them to live". Montagu believed that it would let down assimilationists and the ideals of British Liberalism. The Memorandum was not supposed to accentuate the prejudice of mentioning 'home of the Jewish people'. Weizmann was a key holder at the Ministry of Supply by late 1917. By 1918 Weizmann was accused of combating the idea of a separate peace with Ottoman Empire. He considered such a peace at odds with Zionist interests. He was even accused of "possibly prolonging the war".

At the War Cabinet meeting of 4 October, chaired by Lloyd George and with Balfour present, Lord Curzon also opposed this "barren and desolate" place as a home for Jews. In a third memo Montagu labelled Weizmann a "religious fanatic". Montagu believed in assimilation and saw his principles being swept from under by the new policy stance. Montagu, a British Jew, had learnt debating skills as India Secretary, and Liberalism from Asquith, who also opposed Zionism.

All the memos from Zionists, non-Zionists, and Curzon were all-in by a third meeting convened on Wednesday, 31 October 1917. The War Cabinet had dealt an "irreparable blow to Jewish Britons", wrote Montagu. Curzon's memo was mainly concerned by the non-Jews in Palestine to secure their civil rights. Worldwide there were 12 million Jews, and about 365,000 in Palestine by 1932. Cabinet ministers were worried about Germany playing the Zionist card. If the Germans were in control, it would hasten support for Ottoman Empire, and collapse of Kerensky's government. Curzon went on towards an advanced Imperial view: that since most Jews had Zionist views, it was as well to support these majority voices. "If we could make a declaration favourable to such an ideal we should be able to carry on extremely useful propaganda." Weizmann "was absolutely loyal to Great Britain". The Zionists had been approached by the Germans, Weizmann told William Ormsby-Gore but the British miscalculated the effects of immigration to Palestine, and over-estimated German control over Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans were in no position to prevent movement. Sykes reported the Declaration to Weizmann with elation all round: he repeated "mazel tov" over and over. The Entente had fulfilled its commitment to both Sharif Husein and Chaim Weizmann.

Sykes stressed the Entente: "We are pledged to Zionism, Armenianism liberation, and Arabian independence". On 2 December, Zionists celebrated the Declaration at the Opera House; the news of the Bolshevik Revolution, and withdrawal of Russian troops from the frontier war with Ottoman Empire, raised the pressure from Constantinople. On 11 December, Turkish armies were swept aside when Edmund Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led ...

's troops entered Jerusalem. On 9 January 1918, all Turkish troops withdrew from the Hejaz for a bribe of $2 million to help pay Ottoman Empire's debts. Weizmann had seen peace with Ottoman Empire out of the question in July 1917. Lloyd George wanted a separate peace with Ottoman Empire to guarantee relations in the region secure. Weizmann had managed to gain the support of International Jewry in Britain, France and Italy. Schneer postulates that the British government desperate for any wartime advantage were prepared to offer any support among philo-Semites. It was to Weizmann a priority. Weizmann considered that the issuance of the Balfour Declaration was the greatest single achievement of the pre-1948 Zionists. He believed that the Balfour Declaration and the legislation that followed it, such as the (3 June 1922) Churchill White Paper and the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

Mandate for Palestine all represented an astonishing accomplishment for the Zionist movement.

On 3 January 1919, Weizmann met Hashemite Prince Faisal to sign the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement attempting to establish the legitimate existence of the state of Israel. At the end of the month, the

On 3 January 1919, Weizmann met Hashemite Prince Faisal to sign the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement attempting to establish the legitimate existence of the state of Israel. At the end of the month, the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

decided that the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire should be wholly separated and the newly conceived mandate-system applied to them. Weizmann stated at the conference that "the Zionist objective was gradually to make Palestine as Jewish as England was English" Shortly thereafter, both men made their statements to the conference.

After 1920, he assumed leadership in the World Zionist Organization, creating local branches in Berlin serving twice (1920–31, 1935–46) as president of the World Zionist Organization. Unrest amongst Arab antagonism to a Jewish presence in Palestine increased, erupting into riots. Weizmann remained loyal to Britain, tried to shift the blame onto dark forces. The French were commonly blamed for discontent, as scapegoats for Imperial liberalism. Zionists began to believe racism existed within the administration, which remained inadequately policed.

In 1921, Weizmann went along with

After 1920, he assumed leadership in the World Zionist Organization, creating local branches in Berlin serving twice (1920–31, 1935–46) as president of the World Zionist Organization. Unrest amongst Arab antagonism to a Jewish presence in Palestine increased, erupting into riots. Weizmann remained loyal to Britain, tried to shift the blame onto dark forces. The French were commonly blamed for discontent, as scapegoats for Imperial liberalism. Zionists began to believe racism existed within the administration, which remained inadequately policed.

In 1921, Weizmann went along with Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

for a fund-raiser to establish the Hebrew University in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and support the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology. At this time, simmering differences over competing European and American visions of Zionism, and its funding of development versus political activities, caused Weizmann to clash with Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer and associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.

Starting in 1890, he helped develop the "right to privacy" concept ...

. In 1921 Weizmann played an important role in supporting Pinhas Rutenberg's successful bid to the British for an exclusive electric concession for Palestine, in spite of bitter personal and principled disputes between the two figures.

During the war years, Brandeis headed the precursor of the Zionist Organization of America

The Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) () is an American non-profit pro-Israel organization. Founded in 1897, as the Federation of American Zionists, it was the first official Zionist organization in the United States. Early in the 20th centu ...

, leading fund-raising for Jews trapped in Europe and Palestine. In early October 1914, the '' USS North Carolina'' arrived in Jaffa harbor with money and supplies provided by Jacob Schiff, the American Jewish Committee, and the Provisional Executive Committee for General Zionist Affairs, then acting for the WZO, which had been rendered impotent by the war. Although Weizmann retained Zionist leadership, the clash led to a departure from Louis Brandeis's movement. By 1929, there were about 18,000 members remaining in the ZOA, a massive decline from the high of 200,000 reached during the peak Brandeis years. In summer 1930, these two factions and visions of Zionism, would come to a compromise largely on Brandeis's terms, with a restructured leadership for the ZOA. An American view is Weizmann persuaded the British cabinet to support Zionism by presenting the benefits of having a presence in Palestine in preference to the French. Imperial interests on the Suez Canal as well as sympathy after the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

were important factors for British support.

Jewish immigration to Palestine

Jewish immigration was consciously limited by the British administration. Weizmann agreed with the policy but was afraid of the rise of the Nazis. From 1933, there were year-on-year leaps in mass immigration by 50%. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald's attempted reassurance on economic grounds in a White Paper did little to stabilize Arab-Israeli relations. In 1936 and early 1937, Weizmann addressed the Peel Commission (set up by the returning Conservative Prime MinisterStanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as Prime Minister of the United Kingd ...

), whose job it was to consider the working of the British Mandate of Palestine. He insisted that the Mandate authorities had not driven home to the Palestinian population that the terms of the Mandate would be implemented, using an analogy from another part of the British Empire:

I think it was in Bombay recently, that there had been trouble and the Moslems had been flogged. I am not advocating flogging, but what is the difference between a Moslem in Palestine and a Moslem in Bombay? There they flog them, and here they save their faces. This, interpreted in terms of Moslem mentality, means: "The British are weak; we shall succeed if we make ourselves sufficiently unpleasant. We shall succeed in throwing the Jews into the Mediterranean.'On 25 November 1936, testifying before the Peel Commission, Weizmann said that there were in Europe 6,000,000 Jews "for whom the world is divided into places where they cannot live and places where they cannot enter." The Commission published a report that, for the first time, recommended partition, but the proposal was declared unworkable and formally rejected by the government. The two main Jewish leaders, Weizmann and

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the na ...

had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for more negotiation. This was the first official mention and declaration of a Zionist vision opting for a possible State with a majority of Jewish population, alongside a State with an Arab majority. The Arab leaders, headed by Haj Amin al-Husseini, rejected the plan.

Weizmann made very clear in his autobiography that the failure of the international Zionist movement (between the wars) to encourage all Jews to act decisively and efficiently in great enough numbers to migrate to the Jerusalem area was the real cause for the call for a Partition deal. A deal on Partition was first formally mentioned in 1936 but not finally implemented until 1948. Again, Weizmann blamed the Zionist movement for not being adequate during the best years of the British Mandate.

Ironically, in 1936 Ze'ev Jabotinsky prepared the so-called "evacuation plan", which called for the evacuation of 1.5 million Jews from Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

, Baltic States

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

to Palestine over the span of next ten years. The plan was first proposed on 8 September 1936 in the conservative Polish newspaper Czas, the day after Jabotinsky organized a conference where more details of the plan were laid out; the emigration would take 10 years and would include 750,000 Jews from Poland, with 75,000 between age of 20–39 leaving the country each year. Jabotinsky stated that his goal was to reduce Jewish population in the countries involved to levels that would make them disinterested in its further reduction.

The same year, he toured Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ...

, meeting with the Polish Foreign Minister, Colonel Józef Beck; the Regent of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

, Admiral Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya ( hu, Vitéz nagybányai Horthy Miklós; ; English: Nicholas Horthy; german: Nikolaus Horthy Ritter von Nagybánya; 18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957), was a Hungarian admiral and dictator who served as the regen ...

; and Prime Minister Gheorghe Tătărescu of Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

to discuss the evacuation plan. The plan gained the approval of all three governments, but caused considerable controversy within the Jewish community of Poland, on the grounds that it played into the hands of anti-Semites. In particular, the fact that the 'evacuation plan' had the approval of the Polish government was taken by many Polish Jews as indicating Jabotinsky had gained the endorsement of what they considered to be the wrong people.

The evacuation of Jewish communities in Poland, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

was to take place over a ten-year period. However, the British government vetoed it, and the World Zionist Organization's chairman, Chaim Weizmann, dismissed it.

Weizmann considered himself, not Ben-Gurion, the political heir to Theodor Herzl. Herzl's only grandchild and descendant was Stephen Norman (born Stephan Theodor Neumann, 1918–1946). Dr. H. Rosenblum, the editor of ''Haboker'', a Tel Aviv daily that later became '' Yediot Aharonot'', noted in late 1945 that Dr. Weizmann deeply resented the sudden intrusion and reception of Norman when he arrived in Britain. Norman spoke to the Zionist conference in London. Haboker reported, "Something similar happened at the Zionist conference in London. The chairman suddenly announced to the meeting that in the hall there was Herzl's grandson who wanted to say a few words. The introduction was made in an absolutely dry and official way. It was felt that the chairman looked for—and found—some stylistic formula which would satisfy the visitor without appearing too cordial to anybody among the audience. In spite of that there was a great thrill in the hall when Norman mounted on the platform of the presidium. At that moment, Dr. Weizmann turned his back on the speaker and remained in this bodily and mental attitude until the guest had finished his speech." The 1945 article went on to note that Norman was snubbed by Weizmann and by some in Israel during his visit because of ego, jealousy, vanity and their own personal ambitions. Brodetsky was Chaim Weizmann's principal ally and supporter in Britain. Weizmann secured for Norman a desirable but minor position with the British Economic and Scientific Mission in Washington, D.C.

Second World War

On 29 August 1939, Weizmann sent a letter toNeville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasem ...

, stating in part: "I wish to confirm in the most explicit manner the declarations which I and my colleagues have made during the last month and especially in the last week: that the Jews stand by Great Britain and will fight on the side of the democracies." The letter gave rise to a conspiracy theory, promoted in Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi polici ...

, that he had made a "Jewish declaration of war" against Germany.

At the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, Weizmann was appointed as an Honorary adviser to the British Ministry of Supply, using his extensive political expertise in the management of provisioning and supplies throughout the duration of the conflict. He was frequently asked to advise the cabinet and also brief the Prime Minister. Weizmann's efforts to integrate Jews from Palestine in the war against Germany resulted in the creation of the Jewish Brigade of the British Army which fought mainly in the Italian front. After the war, he grew embittered by the rise of violence in Palestine and by the terrorist tendencies amongst followers of the Revisionist fraction. His influence within the Zionist movement decreased, yet he remained overwhelmingly influential outside of Mandate Palestine.

In 1942, Weizmann was invited by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to work on the problem of synthetic rubber. Weizmann proposed to produce butyl alcohol from maize, then convert it to butylene and further to butadiene, which is a basis for rubber. According to his memoirs, these proposals were barred by the oil companies.

The Holocaust

In 1939, a conference was established atSt James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Alt ...

when the government drew up the May 1939 White Paper which severely curtailed any spending in the Jewish Home Land. Yishuv was put back to the lowest priority. At the outbreak of war the Jewish Agency pledged its support for the British war effort against Nazi Germany. They raised the Jewish Brigade into the British Army, which took years to come to fruition. It authenticated the news of the Holocaust reaching the allies.

In May 1942, the Zionists met at Biltmore Hotel in New York, US; a convention at which Weizmann pressed for a policy of unrestricted immigration into Palestine. A Jewish Commonwealth needed to be established, and latterly Churchill revived his backing for this project.

Weizmann met Churchill on 4 November 1944 to urgently discuss the future of Palestine. Churchill agreed that Partition was preferable for Israel over his White Paper. He also agreed that Israel should annex the Negev desert

The Negev or Negeb (; he, הַנֶּגֶב, hanNegév; ar, ٱلنَّقَب, an-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southe ...

, where no one was living. However, when Lord Moyne, the British Governor of Palestine, had met Churchill a few days earlier, he was surprised that Churchill had changed his views in two years. On 6 November, Moyne was assassinated for his trenchant views on immigration; the immigration question was put on hold.

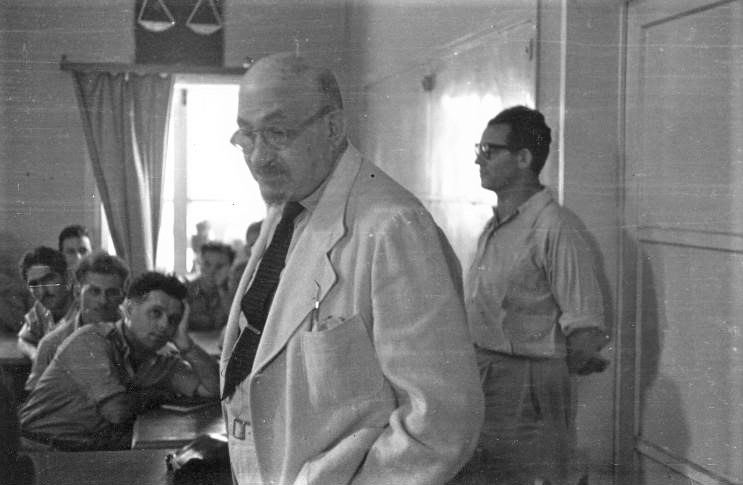

In February 1943, the British government also rejected a plan to pay $3.5 million and just $50 per head to allow 70,000, mostly Romanian, Jews to be protected and evacuated that Weizmann had suggested to the Americans. In May 1944, the British detained Joel Brand, a Jewish activist from Budapest, who wanted to evacuate 1 million Jews from Hungary on 10,000 trucks, with tea, coffee, cocoa, and soap. In July 1944, Weizmann pleaded on Brand's behalf but to no avail. Rezső Kasztner

Rezső Kasztner (1906 – 15 March 1957), also known as Rudolf Israel Kastner, was a Hungarian-Israeli journalist and lawyer who became known for having helped Jews escape from occupied Europe during the Holocaust. He was assassinated in 1957 af ...

took over the direct negotiations with Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

''

Two days after the proclamation of the State of Israel, Weizmann succeeded Ben-Gurion as chairman of the Provisional State Council, a collective presidency that held office until Israel's first parliamentary election, in February 1949.

On 2 July 1948, a new

Two days after the proclamation of the State of Israel, Weizmann succeeded Ben-Gurion as chairman of the Provisional State Council, a collective presidency that held office until Israel's first parliamentary election, in February 1949.

On 2 July 1948, a new

File:Chaim Weizmann funeral, Rehovot (997008136197505171).jpg, Weizmann's funeral in 1952

File:Stamp of Israel - President Dr. Weizmann - 110mil.jpg, Weizmann memorial stamp issued in December 1952

Historical Letters and Primary Sources from Chaim Weizmann

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Weizmann Institute of ScienceThe Chaim Weizmann Laboratory

on Chaim Weizmann's laboratory at the Weizmann Institute (includes info and links on Weizmann's scientific work)

Dr. Weitzmann visits Tel-Aviv,Exhibition in the IDF&Defense establishment archivesChaim Weizmann Personal Manuscripts and Letters

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Weizmann, Chaim 1874 births 1952 deaths Academics of the Victoria University of Manchester British Ashkenazi Jews Belarusian Jews British emigrants to Israel British people of Belarusian-Jewish descent Burials in Israel Cordite Hovevei Zion General Zionists politicians Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United Kingdom Jews from the Russian Empire Israeli chemists Israeli Ashkenazi Jews Israeli people of Belarusian-Jewish descent Israeli people of British-Jewish descent Jewish scientists Ashkenazi Jews in Mandatory Palestine Ashkenazi Jews in Ottoman Palestine People from Motal Presidents of Israel Presidents of Weizmann Institute of Science Technical University of Berlin alumni Weizmann Institute of Science faculty Chaim Technische Universität Darmstadt alumni Presidents of universities in Israel British people of Israeli descent Expatriates in Germany Expatriates in Switzerland Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society Russian Zionists

''

First president of Israel

Two days after the proclamation of the State of Israel, Weizmann succeeded Ben-Gurion as chairman of the Provisional State Council, a collective presidency that held office until Israel's first parliamentary election, in February 1949.

On 2 July 1948, a new

Two days after the proclamation of the State of Israel, Weizmann succeeded Ben-Gurion as chairman of the Provisional State Council, a collective presidency that held office until Israel's first parliamentary election, in February 1949.

On 2 July 1948, a new kibbutz

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming h ...

was founded facing the Golan Heights (Syrian) overlooking the Jordan River, only 5 miles from Syrian territory. Their forces had already seized Kibbutz '' Mishmar Ha-Yarden''. The new kibbutz was named (President's Village) '' Kfar Ha-Nasi''.

When the first Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...