Central Park is an

urban park

An urban park or metropolitan park, also known as a municipal park (North America) or a public park, public open space, or municipal gardens ( UK), is a park in cities and other incorporated places that offer recreation and green space to resi ...

in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

located between the

Upper West and

Upper East Side

The Upper East Side, sometimes abbreviated UES, is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 96th Street to the north, the East River to the east, 59th Street to the south, and Central Park/Fifth Avenue to the wes ...

s of

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. It is the

fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban park in the United States, with an estimated 42 million visitors annually , and is the most filmed location in the world.

After proposals for a large park in Manhattan during the 1840s, it was approved in 1853 to cover . In 1857, landscape architects

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the USA. Olmsted was famous for co- ...

and

Calvert Vaux

Calvert Vaux (; December 20, 1824 – November 19, 1895) was an English-American architect and landscape designer, best known as the co-designer, along with his protégé and junior partner Frederick Law Olmsted, of what would become New York Ci ...

won a

design competition

A design competition or design contest is a competition in which an entity solicits design proposals from the public for a specified purpose.

Architecture

An architectural design competition solicits architects to submit design proposals for a b ...

for the park with their "Greensward Plan". Construction began the same year; existing structures, including a majority-Black settlement named

Seneca Village

Seneca Village was a 19th-century settlement of mostly African American landowners in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, within what would become present-day Central Park. The settlement was located near the current Upper West Side ne ...

, were seized through

eminent domain

Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...

and razed. The park's first areas were opened to the public in late 1858. Additional land at the northern end of Central Park was purchased in 1859, and the park was completed in 1876. After a period of decline in the early 20th century, New York City parks commissioner

Robert Moses

Robert Moses (December 18, 1888 – July 29, 1981) was an American urban planner and public official who worked in the New York metropolitan area during the early to mid 20th century. Despite never being elected to any office, Moses is regarded ...

started a program to clean up Central Park in the 1930s. The

Central Park Conservancy

The Central Park Conservancy is a private, nonprofit park conservancy that manages Central Park under a contract with the City of New York and NYC Parks. The conservancy employs most maintenance and operations staff in the park. It effectively ...

, created in 1980 to combat further deterioration in the late 20th century, refurbished many parts of the park starting in the 1980s.

Main attractions include landscapes such as

the Ramble and Lake

The Ramble and Lake are two geographic features of Central Park in Manhattan, New York City. Part of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux's 1857 Greensward Plan for Central Park, the features are located on the west side of the park betwee ...

,

Hallett Nature Sanctuary

The Pond and Hallett Nature Sanctuary are two connected features at the southeastern corner of Central Park in Manhattan, New York City. It is located near Grand Army Plaza, across Central Park South from the Plaza Hotel, and slightly west of ...

, the

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir

The Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir, also known as Central Park Reservoir, is a decommissioned reservoir in Central Park in the borough of Manhattan, New York City, stretching from 86th to 96th Streets. It covers and holds over 10⁹ US ...

, and

Sheep Meadow

Sheep Meadow is a meadow near the southwestern section of Central Park, between West 66th and 69th Streets in Manhattan, New York City. It is adjacent to Central Park Mall to the east, The Ramble and Lake to the north, West Drive to the we ...

; amusement attractions such as

Wollman Rink

Wollman Rink is a public ice rink in the southern part of Central Park, Manhattan, New York City. It is named after the Wollman family who donated the funds for its original construction. The rink is open for ice skating from late October t ...

,

Central Park Carousel

The Central Park Carousel, officially the Michael Friedsam Memorial Carousel, p.413 is a vintage wood-carved carousel located in Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, at the southern end of the park, near East 65th Street. It is the fourt ...

, and the

Central Park Zoo

The Central Park Zoo is a zoo located at the southeast corner of Central Park in New York City. It is part of an integrated system of four zoos and one aquarium managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). In conjunction with the Central ...

; formal spaces such as the

Central Park Mall and

Bethesda Terrace

Bethesda Terrace and Fountain are two architectural features overlooking the southern shore of The Ramble and Lake, the Lake in New York City's Central Park. The fountain, with its ''Angel of the Waters'' statue, is located in the center of the ...

; and the

Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte Theater is a 1,800-seat open-air theater in Central Park, in the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is home to the Public Theater's free Shakespeare in the Park productions.

Over five million people have attended more than 15 ...

. The

biologically diverse

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity'') ...

ecosystem has several hundred species of flora and fauna. Recreational activities include carriage-horse and bicycle tours, bicycling, sports facilities, and concerts and events such as

Shakespeare in the Park

Shakespeare in the Park is a term for outdoor festivals featuring productions of William Shakespeare's plays. The term originated with the New York Shakespeare Festival in New York City's Central Park, originally created by Joseph Papp. This conc ...

. Central Park is traversed by a system of roads and walkways and is served by public transportation.

Its size and cultural position make it a model for the world's urban parks. Its influence earned Central Park the designations of

National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

in 1963 and of

New York City scenic landmark in 1974. Central Park is owned by the

New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, also called the Parks Department or NYC Parks, is the department of the government of New York City responsible for maintaining the city's parks system, preserving and maintaining the ecolog ...

but has been managed by the Central Park Conservancy since 1998, under a contract with the

municipal government

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the go ...

in a

public–private partnership

A public–private partnership (PPP, 3P, or P3) is a long-term arrangement between a government and private sector institutions.Hodge, G. A and Greve, C. (2007), Public–Private Partnerships: An International Performance Review, Public Administ ...

. The Conservancy, a non-profit organization, raises Central Park's annual operating budget and is responsible for all basic care of the park.

Description

Central Park is bordered by

Central Park North at 110th Street;

Central Park South

59th Street is a crosstown street in the New York City borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan, running from York Avenue and Sutton Place on the East Side (Manhattan), East Side of Manhattan to the West Side Highway on the West Side (Manha ...

at 59th Street;

Central Park West

Eighth Avenue is a major north–south avenue on the west side of Manhattan in New York City, carrying northbound traffic below 59th Street. It is one of the original avenues of the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 to run the length of Manhattan, ...

at Eighth Avenue; and

Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major and prominent thoroughfare in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It stretches north from Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village to West 143rd Street in Harlem. It is one of the most expensive shopping stre ...

on the east. The park is adjacent to the neighborhoods of

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street (Manhattan), 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and 110th Street (Manhattan), ...

to the north,

Midtown Manhattan

Midtown Manhattan is the central portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan and serves as the city's primary central business district. Midtown is home to some of the city's most prominent buildings, including the Empire State Buildin ...

to the south, the

Upper West Side

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper West ...

to the west, and the

Upper East Side

The Upper East Side, sometimes abbreviated UES, is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 96th Street to the north, the East River to the east, 59th Street to the south, and Central Park/Fifth Avenue to the wes ...

to the east. It measures from north to south and from west to east.

Design and layout

Central Park is split into three sections: the "North End" extending above the

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir

The Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir, also known as Central Park Reservoir, is a decommissioned reservoir in Central Park in the borough of Manhattan, New York City, stretching from 86th to 96th Streets. It covers and holds over 10⁹ US ...

; "Mid-Park", between the reservoir to the north and the

Lake

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much large ...

and

Conservatory Water to the south; and "South End" below the Lake and Conservatory Water.

The park has five visitor centers:

Charles A. Dana Discovery Center,

Belvedere Castle

Belvedere Castle is a folly in Central Park in Manhattan, New York City. It contains exhibit rooms, an observation deck, and since 1919 has housed Central Park’s official weather station.

Belvedere Castle was designed by Calvert Vaux and Jac ...

, Chess & Checkers House,

the Dairy

The Dairy is a small building in Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, designed by the architect Calvert Vaux. The building was completed in 1871 as a restaurant but is now one of the park's five visitor centers managed by the Central Park ...

, and

Columbus Circle

Columbus Circle is a traffic circle and heavily trafficked intersection in the New York City borough of Manhattan, located at the intersection of Eighth Avenue, Broadway, Central Park South ( West 59th Street), and Central Park West, at the so ...

.

The park has natural-looking plantings and

landform

A landform is a natural or anthropogenic land feature on the solid surface of the Earth or other planetary body. Landforms together make up a given terrain, and their arrangement in the landscape is known as topography. Landforms include hills, ...

s, having been almost entirely landscaped when built in the 1850s and 1860s. It has eight lakes and ponds that were created artificially by damming natural

seeps and flows. There are several wooded sections, lawns, meadows, and minor grassy areas. There are 21 children's

playground

A playground, playpark, or play area is a place designed to provide an environment for children that facilitates play, typically outdoors. While a playground is usually designed for children, some are designed for other age groups, or people ...

s,

and of drives.

Central Park is the

fifth-largest park in New York City, behind

Pelham Bay Park

Pelham Bay Park is a public park, municipal park located in the northeast corner of the New York City borough (New York City), borough of the Bronx. It is, at , the largest public park in New York City. The park is more than three times the siz ...

, the

Staten Island Greenbelt,

Van Cortlandt Park

Van Cortlandt Park is a park located in the borough of the Bronx in New York City. Owned by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, it is managed with assistance from the Van Cortlandt Park Alliance. The park, the city's third-lar ...

, and

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, often referred to as Flushing Meadows Park, or simply Flushing Meadows, is a public park in the northern part of Queens, New York City. It is bounded by I-678 (Van Wyck Expressway) on the east, Grand Central Par ...

, with an area of .

Central Park constitutes its own United States

census tract, numbered 143. According to

American Community Survey

The American Community Survey (ACS) is a demographics survey program conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. It regularly gathers information previously contained only in the long form of the decennial census, such as ancestry, citizenship, educati ...

five-year estimates, the park was home to four females with a

median age

A population pyramid (age structure diagram) or "age-sex pyramid" is a graphical illustration of the distribution of a population (typically that of a country or region of the world) by age groups and sex; it typically takes the shape of a pyramid ...

of 19.8. Though the

2010 United States Census

The United States census of 2010 was the twenty-third United States national census. National Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2010. The census was taken via mail-in citizen self-reporting, with enumerators servin ...

recorded 25 residents within the census tract, park officials have rejected the claim of anyone permanently living there.

Visitors

Central Park is the most visited

urban park

An urban park or metropolitan park, also known as a municipal park (North America) or a public park, public open space, or municipal gardens ( UK), is a park in cities and other incorporated places that offer recreation and green space to resi ...

in the United States and one of the most visited tourist attractions worldwide, with 42 million visitors in 2016. The number of unique visitors is much lower; a Central Park Conservancy report conducted found that between eight and nine million people visited Central Park, with 37 to 38 million visits between them. By comparison, there were 25 million visitors in 2009,

and 12.3 million in 1973.

The number of tourists as a proportion of total visitors is much lower: in 2009, one-fifth of the 25 million park visitors recorded that year were estimated to be tourists.

The 2011 Conservancy report gave a similar ratio of park usage: only 14% of visits are by people visiting Central Park for the first time. According to the report, nearly two-thirds of visitors are regular park users who enter the park at least once weekly, and about 70% of visitors live in New York City. Moreover, peak visitation occurred during summer weekends, and most visitors used the park for passive recreational activities such as walking or sightseeing, rather than for active sport.

Governance

The park is maintained by the

Central Park Conservancy

The Central Park Conservancy is a private, nonprofit park conservancy that manages Central Park under a contract with the City of New York and NYC Parks. The conservancy employs most maintenance and operations staff in the park. It effectively ...

, a private,

not-for-profit

A nonprofit organization (NPO) or non-profit organisation, also known as a non-business entity, not-for-profit organization, or nonprofit institution, is a legal entity organized and operated for a collective, public or social benefit, in co ...

organization that manages the park under a contract with the

New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, also called the Parks Department or NYC Parks, is the department of the government of New York City responsible for maintaining the city's parks system, preserving and maintaining the ecolog ...

(NYC Parks),

in which the president of the Conservancy is the ''

ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by right ...

'' administrator of Central Park. It effectively oversees the work of both the private and public employees under the authority of the publicly appointed Central Park administrator, who reports to the parks commissioner and the conservancy's president.

The Central Park Conservancy was founded in 1980 as a nonprofit organization with a citizen board to assist with the city's initiatives to clean up and rehabilitate the park.

The Conservancy took over the park's management duties from NYC Parks in 1998, though NYC Parks retained ownership of Central Park.

The Conservancy provides maintenance support and staff training programs for other public parks in New York City, and has assisted with the development of new parks such as the

High Line

The High Line is a elevated park, elevated linear park, greenway (landscape), greenway and rail trail created on a former New York Central Railroad spur on the West Side (Manhattan), west side of Manhattan in New York City. The High Line's ...

and

Brooklyn Bridge Park

Brooklyn Bridge Park is an park on the Brooklyn side of the East River in New York City. Designed by landscape architecture firm Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, the park is located on a plot of land from Atlantic Avenue in the south, und ...

.

Central Park is patrolled by its own

New York City Police Department

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the City of New York, the largest and one of the oldest in ...

precinct, the 22nd (Central Park) Precinct, at the 86th Street transverse. The precinct employs both regular police and auxiliary officers. The 22nd Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 81.2% between 1990 and 2019. The precinct saw one murder, one rape, 21 robberies, seven felony assaults, one burglary, 37 grand larcenies, and one grand larceny auto in 2019.

The citywide

New York City Parks Enforcement Patrol

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation maintains a unit of full-time and seasonal uniformed officers who enforce parks department rules and regulations, as well as New York State laws within the jurisdiction of New York City parks. ...

patrols Central Park, and the Central Park Conservancy sometimes hires seasonal Parks Enforcement Patrol officers to protect certain features such as the

Conservatory Garden

The Conservatory Garden is a formal garden near the northeastern corner of Central Park in Upper Manhattan, New York City. Comprising , it is the only formal garden in Central Park. Conservatory Garden takes its name from a conservatory that ...

.

A free volunteer

medical emergency

A medical emergency is an acute injury or illness that poses an immediate risk to a person's life or long-term health, sometimes referred to as a situation risking "life or limb". These emergencies may require assistance from another, qualified p ...

service, the

Central Park Medical Unit

The Central Park Medical Unit (CPMU) is an all-volunteer ambulance service that provides completely free emergency medical service to patrons of Central Park and the surrounding streets, in Manhattan, New York City, United States.

Description

...

, operates within Central Park. The unit operates a rapid-response patrol with bicycles,

ambulance

An ambulance is a medically equipped vehicle which transports patients to treatment facilities, such as hospitals. Typically, out-of-hospital medical care is provided to the patient during the transport.

Ambulances are used to respond to medi ...

s, and an

all-terrain vehicle

An all-terrain vehicle (ATV), also known as a light utility vehicle (LUV), a quad bike, or simply a quad, as defined by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI); is a vehicle that travels on low-pressure tires, with a seat that is stra ...

. Before the unit was established in 1975, the

New York City Fire Department Bureau of EMS

The New York City Fire Department Bureau of Emergency Medical Services (FDNY EMS) is a division of the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) in charge of emergency medical services for New York City. It was established on March 17, 1996, following ...

often took over 30 minutes to respond to incidents in the park.

History

Planning

Between 1821 and 1855, New York City's population nearly quadrupled. As the city expanded northward up Manhattan Island, people were drawn to the few existing open spaces, mainly cemeteries, for passive recreation. These were seen as escapes from the noise and chaotic life in the city, which at the time was almost entirely centered on

Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan (also known as Downtown Manhattan or Downtown New York) is the southernmost part of Manhattan, the central borough for business, culture, and government in New York City, which is the most populated city in the United States with ...

. The

Commissioners' Plan of 1811

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 was the original design for the streets of Manhattan above Houston Street and below 155th Street, which put in place the rectangular grid plan of streets and lots that has defined Manhattan on its march uptown u ...

, the outline for Manhattan's modern street grid, included several smaller open spaces but not Central Park. As such, John Randel Jr. had surveyed the grounds for the construction of intersections within the modern-day park site. The only remaining surveying bolt from his survey is embedded in a rock north of the present Dairy and the 66th Street transverse, marking the location where West 65th Street would have intersected

Sixth Avenue

Sixth Avenue – also known as Avenue of the Americas, although this name is seldom used by New Yorkers, p.24 – is a major thoroughfare in New York City's borough of Manhattan, on which traffic runs northbound, or "uptown". It is commercial ...

.

Site

By the 1840s, members of the city's elite were publicly calling for the construction of a new large park in Manhattan.

At the time, Manhattan's seventeen squares comprised a combined of land, the largest of which was the

Battery Park

The Battery, formerly known as Battery Park, is a public park located at the southern tip of Manhattan Island in New York City facing New York Harbor. It is bounded by Battery Place on the north, State Street on the east, New York Harbor to ...

at Manhattan island's southern tip. These plans were endorsed in 1844 by ''

New York Evening Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established i ...

'' editor

William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the ''New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poetry ...

, and in 1851 by

Andrew Jackson Downing

Andrew Jackson Downing (October 31, 1815 – July 28, 1852) was an American landscape designer, horticulturist, and writer, a prominent advocate of the Gothic Revival in the United States, and editor of ''The Horticulturist'' magazine (1846–5 ...

, one of the first American landscape designers.

Mayor

Ambrose Kingsland, in a message to the

New York City Common Council

The New York City Council is the lawmaking body of New York City. It has 51 members from 51 council districts throughout the five boroughs.

The council serves as a check against the mayor in a mayor-council government model, the performance of ...

on May 5, 1851, set forth the necessity and benefits of a large new park and proposed the council move to create such a park. Kingsland's proposal was referred to the Council's Committee of Lands, which endorsed the proposal. The committee chose

Jones's Wood

Jones's Wood was a block of farmland on the island of Manhattan overlooking the East River. The site was formerly occupied by the wealthy Schermerhorn and Jones families. Today, the site of Jones's Wood is part of Lenox Hill, in the present-day Up ...

, a tract of land between 66th and 75th streets on the Upper East Side, as the park's site, as Bryant had advocated for Jones Wood. The acquisition was controversial because of its location, small size relative to other potential uptown tracts, and cost. A bill to acquire Jones's Wood was invalidated as unconstitutional, so attention turned to a second site: a area known as "Central Park", bounded by 59th and 106th streets between Fifth and Eighth avenues.

Croton Aqueduct

The Croton Aqueduct or Old Croton Aqueduct was a large and complex water distribution system constructed for New York City between 1837 and 1842. The great aqueducts, which were among the first in the United States, carried water by gravity from ...

Board president Nicholas Dean, who proposed the Central Park site, chose it because the Croton Aqueduct's , collecting reservoir would be in the geographical center. In July 1853, the New York State Legislature passed the Central Park Act, authorizing the purchase of the present-day site of Central Park.

The board of land commissioners conducted property assessments on more than 34,000 lots in the area, completing them by July 1855. While the assessments were ongoing, proposals to downsize the plans were vetoed by mayor

Fernando Wood

Fernando Wood (February 14, 1812 – February 13, 1881) was an American Democratic Party politician, merchant, and real estate investor who served as the 73rd and 75th Mayor of New York City. He also represented the city for several terms in ...

. At the time, the site was occupied by free black people and Irish immigrants who had developed a property-owning community there since 1825. Most of the Central Park site's residents lived in small villages, such as Pigtown;

Seneca Village

Seneca Village was a 19th-century settlement of mostly African American landowners in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, within what would become present-day Central Park. The settlement was located near the current Upper West Side ne ...

;

or in the school and convent at

Mount St. Vincent's Academy. Clearing began shortly after the land commission's report was released in October 1855, and approximately 1,600 residents were evicted under

eminent domain

Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...

.

Though supporters claimed that the park would cost just $1.7 million, the total cost of the land ended up being $7.39 million (equivalent to $ in ), more than the price that

the United States would pay for Alaska a few years later.

Design contest

In June 1856, Fernando Wood appointed a "consulting board" of seven people, headed by author

Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

, to inspire public confidence in the proposed development. Wood hired military engineer

Egbert Ludovicus Viele

Egbert Ludovicus Viele () (June 17, 1825 – April 22, 1902) was a civil engineer and United States Representative from New York from 1885 to 1887, as well as an officer in the Union army during the American Civil War.

Biography

Viele was born ...

as the park's chief engineer, tasking him with a topographical survey of the site. The following April, the state legislature passed a bill to authorize the appointment of four

Democratic and seven

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

commissioners, who had exclusive control over the planning and construction process.

Though Viele had already devised a plan for the park, the commissioners disregarded it and retained him to complete only the topographical surveys. The Central Park Commission began hosting a landscape design contest shortly after its creation. The commission specified that each entry contain extremely detailed specifications, as mandated by the consulting board. Thirty-three firms or organizations submitted plans.

In April 1858, the park commissioners selected

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the USA. Olmsted was famous for co- ...

and

Calvert Vaux

Calvert Vaux (; December 20, 1824 – November 19, 1895) was an English-American architect and landscape designer, best known as the co-designer, along with his protégé and junior partner Frederick Law Olmsted, of what would become New York Ci ...

's "Greensward Plan" as the winning design. Three other plans were designated as runners-up and featured in a city exhibit. Unlike many of the other designs, which effectively integrated Central Park with the surrounding city, Olmsted and Vaux's proposal introduced clear separations with sunken transverse roadways.

The plan eschewed symmetry, instead opting for a more picturesque design.

It was influenced by the pastoral ideals of landscaped cemeteries such as

Mount Auburn in

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, and

Green-Wood in Brooklyn. The design was also inspired by Olmsted's 1850 visit to

Birkenhead Park

Birkenhead Park is a major public park located in the centre of Birkenhead, Merseyside, England. It was designed by Joseph Paxton and opened on 5 April 1847. It is generally acknowledged as the first publicly funded civic park in the world. Th ...

, in the

Liverpool City Region

The Liverpool City Region is a combined authority region of England, centred on Liverpool, incorporating the local authority district boroughs of Halton, Knowsley, Sefton, St Helens, and Wirral. The region is in the historic counties of ...

in England, which is generally acknowledged as the first publicly funded civil park in the world. According to Olmsted, the park was "of great importance as the first real Park made in this country—a democratic development of the highest significance".

Construction

Construction of Central Park's design was executed by a gamut of professionals. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were the primary designers, assisted by board member

Andrew Haswell Green

Andrew Haswell Green (October 6, 1820 – November 13, 1903) was a lawyer, New York City planner, and civic leader. He is considered "the Father of Greater New York," and is responsible for Central Park, the New York Public Library, the Bronx ...

, architect

Jacob Wrey Mould

Jacob Wrey Mould (7 August 1825 – 14 June 1886) was a British architect, illustrator, linguist and musician, noted for his contributions to the design and construction of New York City's Central Park. He was "instrumental" in bringing the Brit ...

, master gardener

Ignaz Anton Pilat Ignaz is a male given name, related to the name Ignatius. Notable people with this name include:

* Franz Ignaz Beck (1734–1807), German musician

* Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644–1704), Bohemian-Austrian musician

* Ignaz Brüll (1846–1907), ...

, and engineer

George E. Waring Jr.

George E. Waring Jr. (July 4, 1833 – October 29, 1898) was an American Sanitary engineering, sanitary engineer and civic reformer. He was an early American designer and advocate of sewer systems that keep domestic sewage separate from storm run ...

Olmsted was responsible for the overall plan, while Vaux designed some of the finer details. Mould, who worked frequently with Vaux, designed the Central Park Esplanade and the

Tavern on the Green

Tavern on the Green is an American cuisine restaurant in Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, near the intersection of Central Park West and West 66th Street on the Upper West Side. The restaurant, housed in a former sheepfold, has been o ...

building. Pilat was the park's chief landscape architect, whose primary responsibility was the importation and placement of plants within the park. A "corps" of construction engineers and foremen, managed by superintending engineer

William H. Grant, were tasked with the measuring and constructing architectural features such as paths, roads, and buildings. Waring was one of the engineers working under Grant's leadership and was in charge of land drainage.

Central Park was difficult to construct because of the generally rocky and swampy landscape. Around of soil and rocks had to be transported out of the park, and more gunpowder was used to clear the area than was used at the

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. More than of topsoil were transported from

Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

and

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, because the original soil was neither fertile nor sufficiently substantial to sustain the flora specified in the Greensward Plan. Modern steam-powered equipment and custom tree-moving machines augmented the work of unskilled laborers. In total, over 20,000 individuals helped construct Central Park. Because of extreme precautions taken to minimize collateral damage, five laborers died during the project, at a time when fatality rates were generally much higher.

During the development of Central Park, Superintendent Olmsted hired several dozen

mounted police

Mounted police are police who patrol on horseback or camelback. Their day-to-day function is typically picturesque or ceremonial, but they are also employed in crowd control because of their mobile mass and height advantage and increasingly in the ...

officers, who were classified into two types of "keepers": park keepers and gate keepers. The mounted police were viewed favorably by park patrons and were later incorporated into a permanent patrol. The regulations were sometimes strict. For instance, prohibited actions included

games of chance

A game of chance is in contrast with a game of skill. It is a game whose outcome is strongly influenced by some randomizing device. Common devices used include dice, spinning tops, playing cards, roulette wheels, or numbered balls drawn from ...

, speech-making, large congregations such as

picnics

A picnic is a meal taken outdoors ( ''al fresco'') as part of an excursion, especially in scenic surroundings, such as a park, lakeside, or other place affording an interesting view, or else in conjunction with a public event such as preceding ...

, or picking flowers or other parts of plants. These ordinances were effective: by 1866, there had been nearly eight million visits and only 110 arrests in the park's history.

Late 1850s

In late August 1857, workers began building fences, clearing vegetation, draining the land, and leveling uneven terrain. By the following month, chief engineer Viele reported that the project employed nearly 700 workers. Olmsted employed workers using

day labor

Day labor (or day labour in Commonwealth spelling) is work done where the worker is hired and paid one day at a time, with no promise that more work will be available in the future. It is a form of contingent work.

Types

Day laborers (also kn ...

, hiring men directly without any contracts and paying them by the day. Many of the laborers were

Irish immigrants

The Irish diaspora ( ga, Diaspóra na nGael) refers to ethnic Irish people and their descendants who live outside the island of Ireland.

The phenomenon of migration from Ireland is recorded since the Early Middle Ages,Flechner and Meeder, The ...

or first-or-second generation

Irish Americans

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

, and some

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

and

Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

; there were no black or female laborers. The workers were often underpaid, and workers would often take jobs at other construction projects to supplement their income. A pattern of seasonal hiring was established, wherein more workers would be hired and paid at higher rates during the summers.

For several months, the park commissioners faced funding issues,

and a dedicated workforce and funding stream was not secured until June 1858.

The landscaped

Upper Reservoir

Upper may refer to:

* Shoe upper or ''vamp'', the part of a shoe on the top of the foot

* Stimulant, drugs which induce temporary improvements in either mental or physical function or both

* ''Upper'', the original film title for the 2013 found fo ...

was the only part of the park that the commissioners were not responsible for constructing; instead, the Reservoir would be built by the Croton Aqueduct board. Work on the Reservoir started in April 1858. The first major work in Central Park involved grading the driveways and draining the land in the park's southern section. The Lake in Central Park's southwestern section was the first feature to open to the public, in December 1858, followed by the Ramble in June 1859. The same year, the New York State Legislature authorized the purchase of an additional at the northern end of Central Park, from 106th to 110th Streets. The section of Central Park south of 79th Street was mostly completed by 1860.

The park commissioners reported in June 1860 that $4 million had been spent on the construction to date. As a result of the sharply rising construction costs, the commissioners eliminated or downsized several features in the Greensward Plan. Based on claims of cost mismanagement, the New York State Senate commissioned the Swiss engineer

Julius Kellersberger

The gens Julia (''gēns Iūlia'', ) was one of the most prominent patrician (ancient Rome), patrician families in ancient Rome. Members of the gens attained the highest dignities of the state in the earliest times of the Roman Republic, Republic ...

to write a report on the park. Kellersberger's report, submitted in 1861, stated that the commission's management of the park was a "triumphant success".

1860s

Olmsted often clashed with the park commissioners, notably with Chief Commissioner Green. Olmsted resigned in June 1862, and Green was appointed to Olmsted's position.

Vaux resigned in 1863 because of what he saw as pressure from Green. As superintendent of the park, Green accelerated construction, though having little experience in architecture.

He implemented a style of

micromanagement

In business management, micromanagement is a management style whereby a manager closely observes, controls, and/or reminds the work of their subordinates or employees.

Micromanagement is generally considered to have a negative connotation, main ...

, keeping records of the smallest transactions in an effort to reduce costs. Green finalized the negotiations to purchase the northernmost of the park which was later converted into a "rugged" woodland and the Harlem Meer waterway.

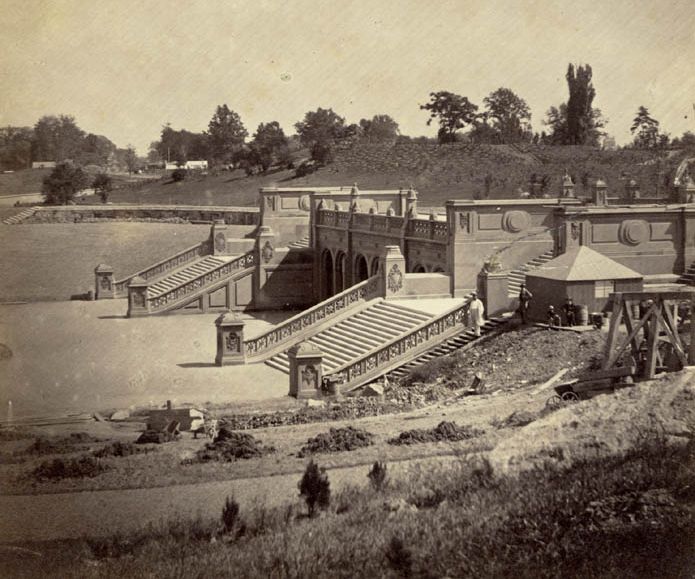

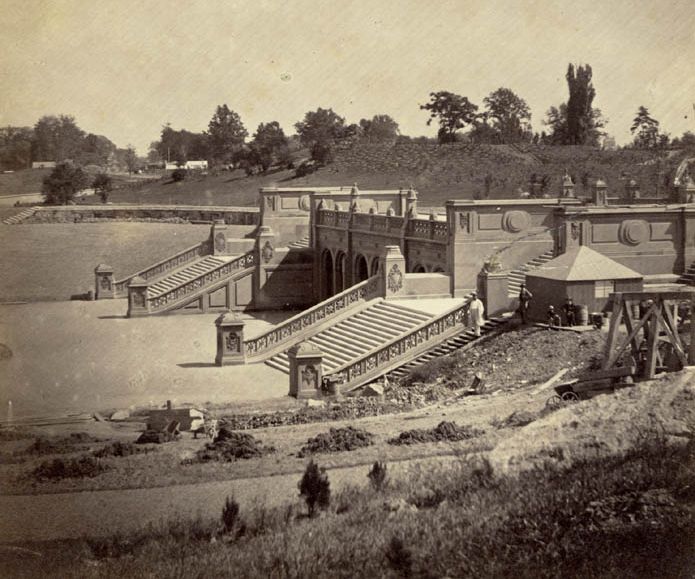

When the American Civil War began in 1861, the park commissioners decided to continue building Central Park, since significant parts of the park had already been completed. Only three major structures were completed during the Civil War: the Music Stand and the

Casino

A casino is a facility for certain types of gambling. Casinos are often built near or combined with hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail shopping, cruise ships, and other tourist attractions. Some casinos are also known for hosting live entertai ...

restaurant, both later demolished, and the

Bethesda Terrace and Fountain

Bethesda Terrace and Fountain are two architectural features overlooking the southern shore of the Lake in New York City's Central Park. The fountain, with its ''Angel of the Waters'' statue, is located in the center of the terrace.

Bethesda T ...

. By late 1861, the park south of 72nd Street had been completed, except for various fences. Work had begun on the northern section of the park but was complicated by a need to preserve the historic

McGowan's Pass

McGowan's Pass (sometimes spelled "McGown's") is a topographical feature of Central Park in New York City, just west of Fifth Avenue and north of 102nd Street. It has been incorporated into the park's East Drive since the early 1860s. A steep ...

. The Upper Reservoir was completed the following year.

During this period Central Park began to gain popularity. One of the main attractions was the "Carriage Parade", a daily display of horse-drawn carriages that traversed the park. Park patronage grew steadily: by 1867, Central Park accommodated nearly three million pedestrians, 85,000 horses, and 1.38 million vehicles annually. The park had activities for New Yorkers of all social classes. While the wealthy could ride horses on bridle paths or travel in horse-drawn carriages, almost everyone was able to participate in sports such as ice-skating or rowing, or listen to concerts at the Mall's bandstand.

Olmsted and Vaux were re-hired in mid-1865. Several structures were erected, including the Children's District, the

Ballplayers House

Ballplayers House is a building in Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, designed by the architecture firm Buttrick White & Burtis. Completed in 1990, it replaced an older building, architect Calvert Vaux's Boys Play House of 1868, which st ...

, and the Dairy in the southern part of Central Park. Construction commenced on Belvedere Castle, Harlem Meer, and structures on Conservatory Water and the Lake.

1870–1876: completion

The

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

political machine, which was the largest political force in New York at the time, was in control of Central Park for a brief period beginning in April 1870. A new

charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

created by Tammany boss

William M. Tweed

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), often erroneously referred to as William "Marcy" Tweed (see below), and widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany ...

abolished the old 11-member commission and replaced it with one with five men composed of Green and four other Tammany-connected figures. Subsequently, Olmsted and Vaux resigned again from the project in November 1870. After Tweed's embezzlement was publicly revealed in 1871, leading to his imprisonment, Olmsted and Vaux were re-hired, and the Central Park Commission appointed new members who were mostly in favor of Olmsted.

One of the areas that remained relatively untouched was the underdeveloped western side of Central Park, though some large structures would be erected in the park's remaining empty plots.

By 1872, Manhattan Square had been reserved for the

American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

, founded three years before at the

Arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

. A corresponding area on the East Side, originally intended as a playground, would later become the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

.

In the final years of Central Park's construction, Vaux and Mould designed several structures for Central Park. The park's sheepfold (now Tavern on the Green) and Ladies' Meadow were designed by Mould in 1870–1871, followed by the administrative offices on the 86th Street transverse in 1872. Even though Olmsted and Vaux's partnership was dissolved by the end of 1872, the park was not officially completed until 1876.

Late 19th and early 20th centuries: first decline

By the 1870s, the park's patrons increasingly came to include the middle and working class, and strict regulations were gradually eased, such as those against public gatherings. Because of the heightened visitor count, neglect by the Tammany administration, and budget cuts demanded by taxpayers, the maintenance expenses for Central Park had reached a nadir by 1879. Olmsted blamed politicians, real estate owners, and park workers for Central Park's decline, though high maintenance costs were also a factor. By the 1890s, the park faced several challenges: cars were becoming commonplace, and with the proliferation of amusements and refreshment stands, people were beginning to see the park as a recreational attraction. The 1904 opening of the

New York City Subway

The New York City Subway is a rapid transit system owned by the government of New York City and leased to the New York City Transit Authority, an affiliate agency of the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Opened on October 2 ...

displaced Central Park as the city's predominant leisure destination, as New Yorkers could travel to farther destinations such as

Coney Island

Coney Island is a peninsular neighborhood and entertainment area in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bounded by Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, Manhattan Beach to its east, L ...

beaches or

Broadway theaters for a five-cent fare.

In the late 19th century the landscape architect

Samuel Parsons

Samuel Bowne Parsons Jr. (8 February 1844 – 3 February 1923), was an American landscape architect. He is remembered as being a founder of the American Society of Landscape Architects, helping to establish the profession.

Early years

Parsons wa ...

took the position of New York City parks superintendent. A onetime apprentice of Calvert Vaux, Parsons helped restore the nurseries of Central Park in 1886. Parsons closely followed Olmsted's original vision for the park, restoring Central Park's trees while blocking the placement of several large statues in the park. Under Parsons' leadership, two circles (now

Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was based ...

and

Frederick Douglass Circle

Frederick Douglass Circle is a traffic circle located at the northwest corner of Central Park at the intersection of Eighth Avenue (Frederick Douglass Boulevard and Central Park West) and 110th Street (Cathedral Parkway and Central Park North) i ...

s) were constructed at the northern corners of the park. He was removed in May 1911 following a lengthy dispute over whether an expense to replace the soil in the park was unnecessary. A succession of Tammany-affiliated Democratic mayors were indifferent toward Central Park.

Several park advocacy groups were formed in the early 20th century. To preserve the park's character, the citywide Parks and Playground Association, and a consortium of multiple Central Park civic groups operating under the Parks Conservation Association, were formed in the 1900s and 1910s. These associations advocated against such changes to the park as the construction of a library, sports stadium, a cultural center, and an underground parking lot. A third group, the Central Park Association, was created in 1926. The Central Park Association and the Parks and Playgrounds Association were merged into the Park Association of New York City two years later.

The

Heckscher Playground—named after philanthropist

August Heckscher

August Heckscher (August 26, 1848 – April 26, 1941) was a German-born American capitalist and philanthropist.

Early life

Heckscher was born in Hamburg, Germany. He was the son of Johann Gustav Heckscher (1797–1865) and Marie Antoinette Br ...

, who donated the play equipment—opened near its southern end in 1926, and quickly became popular with poor immigrant families. The following year, Mayor

Jimmy Walker

James John Walker (June 19, 1881November 18, 1946), known colloquially as Beau James, was mayor of New York City from 1926 to 1932. A flamboyant politician, he was a liberal Democrat and part of the powerful Tammany Hall machine. He was forced t ...

commissioned landscape designer Hermann W. Merkel to create a plan to improve Central Park. Merkel's plans would combat vandalism and plant destruction, rehabilitate paths, and add eight new playgrounds, at a cost of $1 million. One of the suggested modifications, underground irrigation pipes, were installed soon after Merkel's report was submitted. The other improvements outlined in the report, such as fences to mitigate plant destruction, were postponed due to the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.

1930s to 1950s: Moses rehabilitation

In 1934, Republican

Fiorello La Guardia

Fiorello Henry LaGuardia (; born Fiorello Enrico LaGuardia, ; December 11, 1882September 20, 1947) was an American attorney and politician who represented New York in the House of Representatives and served as the 99th Mayor of New York City fro ...

was elected

mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

. He unified the five park-related departments then in existence. Newly appointed city parks commissioner

Robert Moses

Robert Moses (December 18, 1888 – July 29, 1981) was an American urban planner and public official who worked in the New York metropolitan area during the early to mid 20th century. Despite never being elected to any office, Moses is regarded ...

was given the task of cleaning up the park, and he summarily fired many of the Tammany-era staff. At the time, the lawns were filled with weeds and dust patches, while many trees were dying or already dead. Monuments had been vandalized, equipment and walkways were broken, and ironwork was rusted. Moses's biographer

Robert Caro

Robert Allan Caro (born October 30, 1935) is an American journalist and author known for his biographies of United States political figures Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson.

After working for many years as a reporter, Caro wrote '' The Power ...

later said, "The once beautiful Mall looked like a scene of a wild party the morning after. Benches lay on their backs, their legs jabbing at the sky..."

During the following year, the city's parks department replanted lawns and flowers, replaced dead trees and bushes, sandblasted walls, repaired roads and bridges, and restored statues. The park

menagerie

A menagerie is a collection of captive animals, frequently exotic, kept for display; or the place where such a collection is kept, a precursor to the modern Zoo, zoological garden.

The term was first used in 17th-century France, in reference to ...

and Arsenal was transformed into the modern

Central Park Zoo

The Central Park Zoo is a zoo located at the southeast corner of Central Park in New York City. It is part of an integrated system of four zoos and one aquarium managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). In conjunction with the Central ...

, and a rat extermination program was instituted within the zoo. Another dramatic change was Moses' removal of the "

Hoover valley A "Hooverville" was a shanty town built during the Great Depression by the homeless in the United States. They were named after Herbert Hoover, who was President of the United States during the onset of the Depression and was widely blamed for it. T ...

" shantytown at the north end of Turtle Pond, which became the Great Lawn. The western part of the Pond at the park's southeast corner became an ice skating rink called

Wollman Rink

Wollman Rink is a public ice rink in the southern part of Central Park, Manhattan, New York City. It is named after the Wollman family who donated the funds for its original construction. The rink is open for ice skating from late October t ...

, roads were improved or widened, and twenty-one playgrounds were added. These projects used funds from the

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

program, and donations from the public. Moses removed

Sheep Meadow

Sheep Meadow is a meadow near the southwestern section of Central Park, between West 66th and 69th Streets in Manhattan, New York City. It is adjacent to Central Park Mall to the east, The Ramble and Lake to the north, West Drive to the we ...

's sheep to make way for the Tavern on the Green restaurant.

Renovations in the 1940s and 1950s include a restoration of the Harlem Meer completed in 1943, and a new boathouse completed in 1954.

Moses began construction on several other recreational features in Central Park, such as playgrounds and ball fields. One of the more controversial projects proposed during this time was a 1956 dispute over a parking lot for Tavern in the Green. The controversy placed Moses, an urban planner known for displacing families for other large projects around the city, against a group of mothers who frequented a wooded hollow at the site of a parking lot. Though opposed by the parents, Moses approved the destruction of part of the hollow. Demolition work commenced after Central Park was closed for the night and was only halted after the threat of a lawsuit.

1960s and 1970s: "Events Era" and second decline

Moses left his position in May 1960. No park commissioner since then has been able to exercise the same degree of power, nor did NYC Parks remain in as stable a position in the aftermath of his departure. Eight commissioners held the office in the twenty years following his departure. The city experienced economic and social changes, with some residents moving to the suburbs.

Interest in Central Park's landscape had long since declined, and it was now mostly being used for recreation. Several unrealized additions were proposed for Central Park in that decade, such as a public housing development, a golf course, and a "revolving world's fair".

The 1960s marked the beginning of an "Events Era" in Central Park that reflected the widespread cultural and political trends of the period.

The Public Theater

The Public Theater is a New York City arts organization founded as the Shakespeare Workshop in 1954 by Joseph Papp, with the intention of showcasing the works of up-and-coming playwrights and performers.Epstein, Helen. ''Joe Papp: An American Li ...

's annual

Shakespeare in the Park

Shakespeare in the Park is a term for outdoor festivals featuring productions of William Shakespeare's plays. The term originated with the New York Shakespeare Festival in New York City's Central Park, originally created by Joseph Papp. This conc ...

festival was settled in the

Delacorte Theater

The Delacorte Theater is a 1,800-seat open-air theater in Central Park, in the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is home to the Public Theater's free Shakespeare in the Park productions.

Over five million people have attended more than 15 ...

, and summer performances were instituted on the Sheep Meadow and the Great Lawn by the

New York Philharmonic Orchestra

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

and the

Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is operat ...

. During the late 1960s, the park became the venue for rallies and cultural events such as the

"love-ins" and "be-ins" of the period. The same year,

Lasker Rink

Lasker Rink, dedicated as the Loula D. Lasker Memorial Swimming Pool and Skating Rink was a seasonal ice skating rink and swimming pool at the southwest corner of the Harlem Meer in the northern part of Central Park in Manhattan, New York Cit ...

opened in the northern part of the park; the facility served as an ice rink in winter and Central Park's only swimming pool in summer.

By the mid-1970s, managerial neglect resulted in a decline in park conditions. A 1973 report noted that the park suffered from severe erosion and tree decay, and that individual structures were being vandalized or neglected. The Central Park Community Fund was subsequently created based on the recommendation of a report from a

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

professor. The Fund then commissioned a study of the park's management and suggested the appointment of both a NYC Parks administrator and a board of citizens. In 1979, Parks Commissioner

Gordon Davis

Gordon Jamison Davis is an American lawyer and civic leader. He was born in Chicago in 1941 and has been a resident of New York City since his graduation from Harvard Law School in 1967, and has been a prominent leader in New York City's publ ...

established the Office of Central Park Administrator and appointed

Elizabeth Barlow, the executive director of the Central Park Task Force, to the position.

The Central Park Conservancy, a nonprofit organization with a citizen board, was founded the following year.

1970s to 2000s: restoration

Under the leadership of the Central Park Conservancy, the park's reclamation began by addressing needs that could not be met within NYC Parks' existing resources. The Conservancy hired interns and a small restoration staff to reconstruct and repair unique rustic features, undertaking horticultural projects, and removing graffiti under the

broken windows theory

In criminology, the broken windows theory states that visible signs of crime, anti-social behavior and civil disorder create an urban environment that encourages further crime and disorder, including serious crimes. The theory suggests that pol ...

which advocated removing visible signs of decay. The first structure to be renovated was the Dairy, which reopened as the park's first visitor center in 1979. The Sheep Meadow, which reopened the following year, was the first landscape to be restored. Bethesda Terrace and Fountain, the

USS ''Maine'' National Monument, and the

Bow Bridge were also rehabilitated.

By then, the Conservancy was engaged in design efforts and long-term restoration planning,

and in 1981, Davis and Barlow announced a 10-year, $100 million "Central Park Management and Restoration Plan".

The long-closed Belvedere Castle was renovated and reopened in 1983, while the Central Park Zoo closed for a full reconstruction that year.

To reduce the maintenance effort, large gatherings such as free concerts were canceled.

On completion of the planning stage in 1985, the Conservancy launched its first campaign

and mapped out a 15-year restoration plan. Over the next several years, the campaign restored landmarks in the southern part of the park, such as

Grand Army Plaza

Grand Army Plaza, originally known as Prospect Park Plaza, is a public plaza that comprises the northern corner and the main entrance of Prospect Park (Brooklyn), Prospect Park in the New York City Borough (New York City), borough of Brooklyn. ...

and the police station at the 86th Street transverse; while Conservatory Garden in the northeastern corner of the park was restored to a design by

Lynden B. Miller. Real estate developer

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

renovated the Wollman Rink in 1987 after plans to renovate it were delayed repeatedly. The following year, the Zoo reopened after a $35 million, four-year renovation.

Work on the northern end of the park began in 1989.

A $51 million campaign, announced in 1993, resulted in the restoration of bridle trails, the Mall, the Harlem Meer,

and the North Woods,

and the construction of the Dana Discovery Center on the Harlem Meer.

This was followed by the Conservancy's overhaul of the near the

Great Lawn and Turtle Pond

The Great Lawn and Turtle Pond are two connected features of Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, United States. The lawn and pond are located on the site of a former reservoir for the Croton Aqueduct system which was infilled during the ...

, which was completed in 1997. The Upper Reservoir was decommissioned as a part of the city's water supply system in 1993,

and was renamed after former U.S. first lady

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American socialite, writer, photographer, and book editor who served as first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A pop ...

the next year.

During the mid-1990s, the Conservancy hired additional volunteers and implemented a zone-based system of management throughout the park.

The Conservancy assumed much of the park's operations in early 1998.

Renovations continued through the first decade of the 21st century, and a project to restore the pond was commenced in 2000. Four years later, the Conservancy replaced a chain-link fence with a replica of the original cast-iron fence that surrounded the Upper Reservoir. It started refurbishing the ceiling tiles of the Bethesda Arcade, which was completed in 2007. Soon after, the Central Park Conservancy began restoring the Ramble and Lake, in a project that was completed in 2012. Bank Rock Bridge was restored, and the Gill, which empties into the lake, was reconstructed to approximate its dramatic original form. The final feature to be restored was the East Meadow, which was rehabilitated in 2011.

2010s to present

In 2014, the

New York City Council

The New York City Council is the lawmaking body of New York City. It has 51 members from 51 council districts throughout the five Borough (New York City), boroughs.

The council serves as a check against the Mayor of New York City, mayor in a may ...

proposed a study on the viability of banning vehicular traffic from the park's drives. The next year, mayor

Bill de Blasio

Bill de Blasio (; born Warren Wilhelm Jr., May 8, 1961; later Warren de Blasio-Wilhelm) is an American politician who served as the 109th mayor of New York City from 2014 to 2021. A member of the Democratic Party, he held the office of New Yor ...

announced that West and East drives north of 72nd Street would be closed to vehicular traffic, because the city's data showed that closing the roads did not adversely impact traffic flows. Subsequently, in June 2018, the remaining drives south of 72nd Street were closed to vehicular traffic.

Several structures were renovated. Belvedere Castle was closed in 2018 for an extensive renovation, reopening in June 2019. Later in 2018, it was announced that the Delacorte Theater would be closed from 2020 to 2022 for a $110 million rebuild. The Central Park Conservancy further announced that Lasker Rink would be closed for a $150 million renovation between 2021 and 2024.

Landscape features

Geology

There are four different types of

bedrock

In geology, bedrock is solid Rock (geology), rock that lies under loose material (regolith) within the crust (geology), crust of Earth or another terrestrial planet.

Definition

Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies looser surface mater ...

in Manhattan. In Central Park,

Manhattan schist

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

and Hartland schist, which are both metamorphosed

sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

, are exposed in various

outcrop

An outcrop or rocky outcrop is a visible exposure of bedrock or ancient superficial deposits on the surface of the Earth.

Features

Outcrops do not cover the majority of the Earth's land surface because in most places the bedrock or superficial ...

pings. The other two types,

Fordham gneiss (an older deeper layer) and

Inwood marble

Tuckahoe marble (also known as Inwood and Westchester marble) is a type of marble found in southern New York state and western Connecticut. Part of the Inwood Formation of the Manhattan Prong, it dates from the Late Cambrian to the Early Ordovici ...

(metamorphosed

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

which overlays the

gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures an ...

), do not surface in the park. Fordham gneiss, which consists of metamorphosed

igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main The three types of rocks, rock types, the others being Sedimentary rock, sedimentary and metamorphic rock, metamorphic. Igneous rock ...

s, was formed a billion years ago, during the

Grenville orogeny

The Grenville orogeny was a long-lived Mesoproterozoic mountain-building event associated with the assembly of the supercontinent Rodinia. Its record is a prominent orogenic belt which spans a significant portion of the North American continent, ...

that occurred during the creation of an ancient super-continent. Manhattan schist and Hartland schist were formed in the

Iapetus Ocean during the

Taconic orogeny

The Taconic orogeny was a mountain building period that ended 440 million years ago and affected most of modern-day New England. A great mountain chain formed from eastern Canada down through what is now the Piedmont of the East coast of the Unit ...

in the

Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

era, about 450 million years ago, when the tectonic plates began to merge to form the supercontinent

Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

.

Cameron's Line

Cameron's Line is an Ordovician suture fault in the northeast United States which formed as part of the continental collision known as the Taconic orogeny around 450 mya. Named after Eugene N. Cameron, who first described it in the 1950s, it ...

, a

fault zone

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

that traverses Central Park on an east–west axis, divides the outcroppings of Hartland schist to the south and Manhattan schist to the north.

Various glaciers have covered the area of Central Park in the past, with the most recent being the

Wisconsin glacier

The Wisconsin Glacial Episode, also called the Wisconsin glaciation, was the most recent glacial period of the North American ice sheet complex. This advance included the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which nucleated in the northern North American Cord ...

which receded about 12,000 years ago. Evidence of past glaciers can be seen throughout the park in the form of

glacial erratic

A glacial erratic is glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word ' ("to wander"), are carried by glacial ice, often over distances of hundred ...

s (large boulders dropped by the receding glacier) and north–south glacial striations visible on stone outcroppings.

Alignments of glacial erratics, called "boulder trains", are present throughout Central Park. The most notable of these outcroppings is

Rat Rock (also known as Umpire Rock), a circular outcropping at the southwestern corner of the park.

It measures wide and tall with different east, west, and north faces.

sometimes congregate there.

A single

glacial pothole

A giant's kettle, also known as either a giant's cauldron, moulin pothole, or glacial pothole, is a typically large and cylindrical pothole drilled in solid rock underlying a glacier either by water descending down a deep moulin or by gravel r ...

with yellow clay is near the southwest corner of the park.

The underground geology of Central Park was altered by the construction of several subway lines underneath it, and by the

New York City Water Tunnel No. 3 approximately underground. Excavations for the project have uncovered

pegmatite

A pegmatite is an igneous rock showing a very coarse texture, with large interlocking crystals usually greater in size than and sometimes greater than . Most pegmatites are composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica, having a similar silicic com ...

,

feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagioclase'' (sodium-calcium) feldsp ...

,

quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

,

biotite

Biotite is a common group of phyllosilicate minerals within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula . It is primarily a solid-solution series between the iron-endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more alumino ...

, and several

metal

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typicall ...

s.