Cartorhynchus Scale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cartorhynchus'' (meaning "shortened snout") is an extinct

In 2011, the only known specimen of ''Cartorhynchus'' was discovered in Bed 633 from the second level of the Majiashan Quarry near downtown

In 2011, the only known specimen of ''Cartorhynchus'' was discovered in Bed 633 from the second level of the Majiashan Quarry near downtown

At the time of its discovery, ''Cartorhynchus'' was the smallest-known member of the

At the time of its discovery, ''Cartorhynchus'' was the smallest-known member of the

Initially, Motani and colleagues inferred that ''Cartorhynchus'' was toothless; however, micro-CT scanning subsequently revealed the presence of rounded, molar-like teeth that projected inwards nearly perpendicularly to the long axis of the jaw, therefore making them invisible externally. All of the teeth were either completely flattened or weakly pointed, and many of the teeth bore a constriction between the root and the crown. Unlike other ichthyosauriforms with molariform teeth, all of the tooth crowns were "swollen" to a similar extent. On the

Initially, Motani and colleagues inferred that ''Cartorhynchus'' was toothless; however, micro-CT scanning subsequently revealed the presence of rounded, molar-like teeth that projected inwards nearly perpendicularly to the long axis of the jaw, therefore making them invisible externally. All of the teeth were either completely flattened or weakly pointed, and many of the teeth bore a constriction between the root and the crown. Unlike other ichthyosauriforms with molariform teeth, all of the tooth crowns were "swollen" to a similar extent. On the

''Cartorhynchus'' appears to have had 5 neck vertebrae and 26 back vertebrae, for a total of 31 pre-sacral vertebrae (

''Cartorhynchus'' appears to have had 5 neck vertebrae and 26 back vertebrae, for a total of 31 pre-sacral vertebrae (

The lack of complete fossil remains has resulted in a lack of clarity about the origins of the Ichthyopterygia, including the

The lack of complete fossil remains has resulted in a lack of clarity about the origins of the Ichthyopterygia, including the

Many ichthyosauriforms from the Early and

Many ichthyosauriforms from the Early and

Motani and colleagues hypothesized in 2014 that ''Cartorhynchus'' was a

Motani and colleagues hypothesized in 2014 that ''Cartorhynchus'' was a

''Cartorhynchus'' had poorly-ossified limbs in spite of its well-ossified skull and vertebrae. However, Motani and colleagues suggested in 2014 that it was still an adult because many early-diverging members of marine reptile lineages have poorly-ossified limbs through

''Cartorhynchus'' had poorly-ossified limbs in spite of its well-ossified skull and vertebrae. However, Motani and colleagues suggested in 2014 that it was still an adult because many early-diverging members of marine reptile lineages have poorly-ossified limbs through  A 2019 study by Susana Gutarra and colleagues used computational simulations to estimate the energy cost of swimming in ichthyosauriforms. Early-diverging ichthyosauriforms with lizard-shaped bodies and elongate, flukeless tails, like ''Cartorhynchus'', would have employed

A 2019 study by Susana Gutarra and colleagues used computational simulations to estimate the energy cost of swimming in ichthyosauriforms. Early-diverging ichthyosauriforms with lizard-shaped bodies and elongate, flukeless tails, like ''Cartorhynchus'', would have employed

Bed 633 of the Majiashan Quarry, the locality where ''Cartorhynchus'' was found, is a layer of grey

Bed 633 of the Majiashan Quarry, the locality where ''Cartorhynchus'' was found, is a layer of grey

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of early

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

ichthyosauriform marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment.

The earliest marine reptile mesosaurus (not to be confused with mosasaurus), arose in the Permian period during the ...

that lived during the Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which is a un ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

, about 248 million years ago. The genus contains a single species, ''Cartorhynchus lenticarpus'', named in 2014 by Ryosuke Motani and colleagues from a single nearly-complete skeleton found near Chaohu

Chaohu () is a county-level city of Anhui Province, People's Republic of China, it is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Hefei. Situated on the northeast and southeast shores of Lake Chao, from which the city was named, Chao ...

, Anhui Province

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze River ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. Along with its close relative ''Sclerocormus

''Sclerocormus'' is an extinct genus of ichthyosauriform from the early Triassic period. The fossil was discovered in the central Anhui Province, China. It is currently only known from one specimen, however the fossil is mostly complete and as ...

'', ''Cartorhynchus'' was part of a diversification of marine reptiles that occurred suddenly (over about one million years) during the Spathian

In the geologic timescale, the Olenekian is an age in the Early Triassic epoch; in chronostratigraphy, it is a stage in the Lower Triassic series. It spans the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). The Olenekian is sometimes divided int ...

substage, soon after the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event, but they were subsequently driven to extinction by volcanism and sea level changes by the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epochs of the Triassic period or the middle of three series in which the Triassic system is divided in chronostratigraphy. The Middle Triassic spans the time between Ma and ...

.

Measuring about long, ''Cartorhynchus'' was a small animal with a lizard-like body and a short torso; it probably swam in an eel-like manner at slow speeds. Its limbs bore extensive cartilage and could bend like flippers, which may have allowed it to walk on land. The most distinctive features of ''Cartorhynchus'' were its short, constricted snout, and its multiple rows of molar-like teeth which grew on the inside surface of its jaw bones. These teeth were not discovered until the specimen was subjected to CT scanning

A computed tomography scan (CT scan; formerly called computed axial tomography scan or CAT scan) is a medical imaging technique used to obtain detailed internal images of the body. The personnel that perform CT scans are called radiographers ...

. ''Cartorhynchus'' likely preyed on hard-shelled invertebrates using suction feeding

Aquatic feeding mechanisms face a special difficulty as compared to feeding on land, because the density of water is about the same as that of the prey, so the prey tends to be pushed away when the mouth is closed. This problem was first identifi ...

, although how it exactly used its inward-directed teeth is not yet known. It was one of up to five independent acquisitions of molar-like teeth among ichthyosauriforms.

Discovery and naming

In 2011, the only known specimen of ''Cartorhynchus'' was discovered in Bed 633 from the second level of the Majiashan Quarry near downtown

In 2011, the only known specimen of ''Cartorhynchus'' was discovered in Bed 633 from the second level of the Majiashan Quarry near downtown Chaohu

Chaohu () is a county-level city of Anhui Province, People's Republic of China, it is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Hefei. Situated on the northeast and southeast shores of Lake Chao, from which the city was named, Chao ...

, Anhui Province

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze River ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

; the rock strata in this quarry belong to the Upper Member of the Nanlinghu Formation. The specimen consists of a nearly-complete skeleton missing only part of the tail and some of the bones from the left part of the rear skull. The specimen's preservation likely resulted from it having been deposited in sediment right side down, thus leaving the left side exposed to the elements. It received a field number of MT-II, and later a specimen number of AGB 6257 at the Anhui Geological Museum.

In 2014, the specimen was described by Ryosuke Motani and colleagues in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'' as representing a new genus and species, ''Cartorhynchus lenticarpus''. They derived the generic name ''Cartorhynchus'' from the Greek words (καρτός, "shortened") and (ῥύγχος, "snout"), and the specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

''lenticarpus'' from the Latin words ("flexible") and ("wrist"). Both names refer to anatomical characteristics that it would have had in life. The specimen was thought to be toothless until an isolated tooth was discovered during further attempts to remove rock from between the closed jaws. Since the specimen was too fragile to expose the interior of the jaws, Jian-Dong Huang, Motani, and other colleagues subsequently scanned and rendered the specimen in 3D using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), performed at the Yinghua Testing Company in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

, China. In 2020, results from their follow-up work were published in ''Scientific Reports

''Scientific Reports'' is a peer-reviewed open-access scientific mega journal published by Nature Portfolio, covering all areas of the natural sciences. The journal was established in 2011. The journal states that their aim is to assess solely th ...

''.

Description

Ichthyosauriformes

The Ichthyosauriformes are a group of marine reptiles, belonging to the Ichthyosauromorpha, that lived during the Mesozoic.

The stem clade Ichthyosauriformes was in 2014 defined by Ryosuke Motani and colleagues as the group consisting of all ...

. The preserved specimen had a length of ; assuming that it had tail proportions comparable to close relatives, Motani and colleagues estimated a full body length of and a weight of . In 2021, Sander and colleagues produced a much lower weight estimate of .

Skull

''Cartorhynchus'' had an unusually short and constricted snout, which only occupied half of the skull's length, and a deep jaw. The tip of the snout was only wide. Unlike most reptiles, itsnasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

reached the front of the snout. Due to its likewise elongated premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

, its bony nostrils were located relatively far back on the skull, and its frontal bone

The frontal bone is a bone in the human skull. The bone consists of two portions.''Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bony part of the forehead, par ...

also lacked an expansion at its rear outer corner. All of these characteristics were shared with its close relative ''Sclerocormus

''Sclerocormus'' is an extinct genus of ichthyosauriform from the early Triassic period. The fossil was discovered in the central Anhui Province, China. It is currently only known from one specimen, however the fossil is mostly complete and as ...

''. However, unlike the latter, the frontal bone did not contribute to the eye socket in ''Cartorhynchus''; the prefrontal and postfrontal bones did not meet above the eye socket; and the location of the large hole for the pineal gland

The pineal gland, conarium, or epiphysis cerebri, is a small endocrine gland in the brain of most vertebrates. The pineal gland produces melatonin, a serotonin-derived hormone which modulates sleep, sleep patterns in both circadian rhythm, circ ...

on the skull roof differed: it was at the contact between the frontal and parietal bone

The parietal bones () are two bones in the Human skull, skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint, form the sides and roof of the Human skull, cranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, an ...

s in ''Sclerocormus'', but solely on the parietals in ''Cartorhynchus''. ''Cartorhynchus'' also had a characteristically large hyoid bone

The hyoid bone (lingual bone or tongue-bone) () is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical vertebr ...

.

Initially, Motani and colleagues inferred that ''Cartorhynchus'' was toothless; however, micro-CT scanning subsequently revealed the presence of rounded, molar-like teeth that projected inwards nearly perpendicularly to the long axis of the jaw, therefore making them invisible externally. All of the teeth were either completely flattened or weakly pointed, and many of the teeth bore a constriction between the root and the crown. Unlike other ichthyosauriforms with molariform teeth, all of the tooth crowns were "swollen" to a similar extent. On the

Initially, Motani and colleagues inferred that ''Cartorhynchus'' was toothless; however, micro-CT scanning subsequently revealed the presence of rounded, molar-like teeth that projected inwards nearly perpendicularly to the long axis of the jaw, therefore making them invisible externally. All of the teeth were either completely flattened or weakly pointed, and many of the teeth bore a constriction between the root and the crown. Unlike other ichthyosauriforms with molariform teeth, all of the tooth crowns were "swollen" to a similar extent. On the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

(upper jawbone) and dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

(lower jawbone), the teeth were arranged in three rows, with the outermost row having the most and largest teeth; the maxillae had seven, five, and probably one teeth each, while the dentaries had ten, seven, and four teeth each. Among ichthyosauriforms, only ''Cartorhynchus'' and '' Xinminosaurus'' have multiple rows of teeth. The arrangement of the teeth meant that the front-most lower teeth would have had no corresponding upper tooth, and also that the two dentaries forming the lower jaw could not have been tightly fused. This characteristic would have been shared with its close relatives, the toothless hupehsuchia

Hupehsuchia is an order of diapsid reptiles closely related to ichthyosaurs. The group was short-lasting, with a temporal range restricted to the late Olenekian age, spanning only a few million years of the Early Triassic. The order gets its na ...

ns.

Postcranial skeleton

''Cartorhynchus'' appears to have had 5 neck vertebrae and 26 back vertebrae, for a total of 31 pre-sacral vertebrae (

''Cartorhynchus'' appears to have had 5 neck vertebrae and 26 back vertebrae, for a total of 31 pre-sacral vertebrae (vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

e in front of its sacrum

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

, or hip). Along with ''Sclerocormus'' (with 34 pre-sacrals) and ''Chaohusaurus

''Chaohusaurus'' is an extinct genus of basal ichthyopterygian, depending on definition possibly ichthyosaur, from the Early Triassic of Chaohu and Yuanan, China.

Discovery

The type species ''Chaohusaurus geishanensis'' was named and des ...

'' (with 36 pre-sacrals), ''Cartorhynchus'' falls within the typical range for terrestrial animals, unlike the 40 to 80 pre-sacrals common among the more derived

Derive may refer to:

* Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguatio ...

(specialized) ichthyopterygia

Ichthyopterygia ("fish flippers") was a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1840 to designate the Jurassic ichthyosaurs that were known at the time, but the term is now used more often for both true Ichthyosauria and their more primitiv ...

ns. Unlike ''Sclerocormus'', the neural spines

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

projecting from the top of the vertebrae in ''Cartorhynchus'' were relatively narrow and inclined instead of broad and flanged. ''Cartorhynchus'' can also be distinguished by its parapophyses, vertebral processes that articulated with the ribs; their front margins were confluent with those of the vertebrae.

Both ''Cartorhynchus'' and ''Sclerocormus'' had heavily-built ribcages, which were deepest near the shoulder, with broad, flattened, and thick-walled ribs, as is commonly seen in early members of secondarily-aquatic reptile lineages. The Ichthyopterygia lost these flattened ribs with the exception of ''Mollesaurus

''Mollesaurus'' is an extinct genus of large ophthalmosaurine ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaur known from northwestern Patagonia of Argentina.

Etymology

''Mollesaurus'' was named by Marta S. Fernández in 1999 and the type species is ''Mollesaur ...

''. On the underside of the chest, the gastralia

Gastralia (singular gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In these ...

of ''Cartorhynchus'' were thin and rod-like, unlike the flattened "basket" of ''Sclerocormus'', but both lacked another pair of symmetrical elements at the midline of the body.

The limbs of ''Cartorhynchus'' were poorly ossified

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by Cell (biology), cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes ...

(only three digits of the hand were ossified) with widely-spaced bones, particularly between the wrist bones (carpals) and the digits, suggesting the presence of extensive cartilage in the limbs. This would have made the limbs flipper-like. The forelimb flippers of ''Cartorhynchus'' were curved backwards, with the digits being tilted 50° relative to the axis of the long bones (zeugopodium), while the hindlimbs were curved forwards. The femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

of ''Cartorhynchus'' was straight and not expanded at its bottom end. ''Sclerocormus'' had similar limbs, except they were better-ossified and their preserved curvature may not have been natural.

Classification

The lack of complete fossil remains has resulted in a lack of clarity about the origins of the Ichthyopterygia, including the

The lack of complete fossil remains has resulted in a lack of clarity about the origins of the Ichthyopterygia, including the ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

s. For many years, their fossils were considered to have abruptly appeared in the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epochs of the Triassic period or the middle of three series in which the Triassic system is divided in chronostratigraphy. The Middle Triassic spans the time between Ma and ...

with strong aquatic adaptations. The discovery of ''Cartorhynchus'' and ''Sclerocormus'' partially filled this gap. Phylogenetic analyses

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

conducted by Motani and colleagues found that the two were closely related to each other — forming a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

(group) called the Nasorostra

The Ichthyosauriformes are a group of marine reptiles, belonging to the Ichthyosauromorpha, that lived during the Mesozoic.

The stem clade Ichthyosauriformes was in 2014 defined by Ryosuke Motani and colleagues as the group consisting of all ...

— and to the Ichthyopterygia, to which nasorostrans formed the sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

. ''Cartorhynchus'' and ''Sclerocormus'' were united by their short snouts, elongated nasals, deep jaws, frontals lacking expansions, rib-cages deepest near the shoulder, and scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eithe ...

e (shoulder blades) wider at the bottom end than at the top end.

Incorporating nasorostrans into phylogenetic analyses also provided evidence in support of the hupehsuchians as close relatives of the ichthyopterygians. In 2014, Motani and colleagues named the clade formed by Nasorostra and Ichthyopterygia as the Ichthyosauriformes, and the clade formed by Ichthyosauriformes and Hupehsuchia as the Ichthyosauromorpha

The Ichthyosauromorpha are an extinct clade of marine reptiles consisting of the Ichthyosauriformes and the Hupehsuchia, living during the Mesozoic.

The node clade Ichthyosauromorpha was first defined by Ryosuke Motani ''et al.'' in 2014 as th ...

. Notably, the close relation between these different groups was recovered by their analyses regardless of whether characteristics linked to aquatic adaptations were removed from the analysis. Such characteristics may have developed homoplasiously (from convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

) among multiple lineages due to similar lifestyles, which can bias phylogenetic analyses to reconstruct them as homologies (derived from shared ancestry). The persistence of these reconstructed relationships even after the removal of aquatic characteristics points to their robustness.

Below, the phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

from the phylogenetic analysis published by Huang, Motani, and colleagues in 2019, in the description of ''Chaohusaurus brevifemoralis'', is partially reproduced.

Evolutionary history

The appearance of ichthyosauromorphs was part of the recovery of marine ecosystems following the devastatingPermian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, as ...

. It was commonly believed that marine ecosystems did not recover their full diversity until 5 to 10 million years following the mass extinction, and that marine reptiles recovered more slowly from the extinction than other lineages. However, the discovery of multiple diverse faunas of marine reptiles occurring in the Early Triassic — including ''Cartorhynchus'' — subsequently showed that this was not the case. In particular, it appears that ichthyosauriforms first appeared during the Spathian substage of the Olenekian

In the geologic timescale, the Olenekian is an age in the Early Triassic epoch; in chronostratigraphy, it is a stage in the Lower Triassic series. It spans the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). The Olenekian is sometimes divided into ...

stage

Stage or stages may refer to:

Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly British theatre newspaper

* Sta ...

and quickly attained high functional diversity in the first million years of their evolution. They occupied a variety of niches despite relatively low species diversity, including both demersal

The demersal zone is the part of the sea or ocean (or deep lake) consisting of the part of the water column near to (and significantly affected by) the seabed and the benthos. The demersal zone is just above the benthic zone and forms a layer of ...

(bottom-dwelling) species like hupehsuchians and nasorostrans, and pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

(open-water) species like ichthyopterygians.

Many ichthyosauriforms from the Early and

Many ichthyosauriforms from the Early and Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epochs of the Triassic period or the middle of three series in which the Triassic system is divided in chronostratigraphy. The Middle Triassic spans the time between Ma and ...

had molariform teeth (shown in the phylogenetic tree above), including ''Cartorhynchus''; such teeth indicate a diet at least partially based on hard-shelled animals. In 2020, Huang and colleagues performed an ancestral state reconstruction of teeth among ichthyosauromorphs. Probabilistic methods suggested that rounded or flat teeth most likely evolved independently five times, while methods based on parsimony

Parsimony refers to the quality of economy or frugality in the use of resources.

Parsimony may also refer to

* The Law of Parsimony, or Occam's razor, a problem-solving principle

** Maximum parsimony (phylogenetics), an optimality criterion in p ...

suggested that they evolved independently three to five times. Huang and colleagues observed that the development of molariform teeth occurred independently many times in aquatic animals (including multiple lineages of monitor lizard

Monitor lizards are lizards in the genus ''Varanus,'' the only extant genus in the family Varanidae. They are native to Africa, Asia, and Oceania, and one species is also found in the Americas as an invasive species. About 80 species are recogn ...

s, moray eel

Moray eels, or Muraenidae (), are a family of eels whose members are found worldwide. There are approximately 200 species in 15 genera which are almost exclusively marine, but several species are regularly seen in brackish water, and a few are f ...

s, and sparid and cichlid

Cichlids are fish from the family Cichlidae in the order Cichliformes. Cichlids were traditionally classed in a suborder, the Labroidei, along with the wrasses ( Labridae), in the order Perciformes, but molecular studies have contradicted this ...

fish), and thus the frequency among ichthyosauriforms is not unusually high. They also observed that Early Triassic ichthyosauriforms generally had small, rounded teeth; the teeth of Middle Triassic ichthyosauriforms were more diverse in size and shape, which correlates with increased invertebrate diversity. Thus, they suggested that the diversification of ichthyosauriforms was partially driven by the evolution of hard-shelled prey.

However, hupehsuchians and nasorostrans ultimately went extinct at the boundary between the Early and Middle Triassic, producing a "taxonomic bottleneck". At the boundary, sea level changes and volcanism led to poorly oxygenated oceans, producing a characteristic carbon isotope signature from decaying organic material in rock strata at the boundary. Ichthyosauriforms did not recover in diversity after this turnover, with the Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauria became ...

and Saurosphargidae

Saurosphargidae is an extinct family of marine reptiles known from the early Middle Triassic (Anisian stage) of Europe and China.

The type species of the family is '' Saurosphargis volzi'', named by Friedrich von Huene in 1936 based on a single ...

driving a second wave of diversification lasting three to five million years.

Palaeobiology

Diet

Motani and colleagues hypothesized in 2014 that ''Cartorhynchus'' was a

Motani and colleagues hypothesized in 2014 that ''Cartorhynchus'' was a suction feeder

Aquatic feeding mechanisms face a special difficulty as compared to feeding on land, because the density of water is about the same as that of the prey, so the prey tends to be pushed away when the mouth is closed. This problem was first identifi ...

which fed by concentrating pressure in its narrow snout. This was further supported by the robustness of its hyoid and hyobranchial element (which would have anchored the tongue), and their incorrect observation of toothlessness. Similar inferences were subsequently made for ''Sclerocormus''. ''Shastasaurus

''Shastasaurus'' ("Mount Shasta lizard") is a very large extinct genus of ichthyosaur from the middle and late Triassic, and is the largest known marine reptile.Hilton, Richard P., ''Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Animals of California'', Universit ...

'' and ''Shonisaurus

''Shonisaurus'' is a very large genus of ichthyosaur. At least 37 incomplete fossil specimens of the marine reptile have been found in the Luning Formation of Nevada, USA. This formation dates to the late Carnian age of the late Triassic period, ...

'' had previously been interpreted as suction-feeding ichthyosaurs, but a quantitative analysis of Triassic and Jurassic ichthyosaurs by Motani and colleagues in 2013 showed that none of them had sufficiently robust hyobranchial bones nor sufficiently narrow snouts to enable suction feeding.

The discovery of molariform teeth in ''Cartorhynchus'' led Huang and colleagues to conclude in 2020 that ''Cartorhynchus'' was durophagous

Durophagy is the eating behavior of animals that consume hard-shelled or exoskeleton bearing organisms, such as corals, shelled mollusks, or crabs. It is mostly used to describe fish, but is also used when describing reptiles, including fossil tu ...

, feeding on hard-shelled prey. They noted that this did not contradict a suction-feeding lifestyle; some sparid fish are both durophagous and suction-feeding. However, they suggested that ''Cartorhynchus'' would have been restricted to feeding on small prey. As for the horizontal orientation of the teeth, they observed wear surfaces which indicated that the sides of the teeth occluded with each other, instead of the crowns. However, they noted that teeth are structurally strongest at their tips, not on their sides, under the high stresses of crushing bites. They suggested that the jaw may have been twisted during preservation, or soft tissues like collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

which held up the teeth in life may have been lost, although they conceded that neither hypothesis would explain the wear patterns. Finally, they noted that the lower teeth without corresponding upper teeth were unusual; they show no wear patterns, and there is no evidence of muscular mechanisms which would have allowed the two jaws to be used against each other. Therefore, they inferred that these teeth were probably not used against other teeth.

Limbs and locomotion

''Cartorhynchus'' had poorly-ossified limbs in spite of its well-ossified skull and vertebrae. However, Motani and colleagues suggested in 2014 that it was still an adult because many early-diverging members of marine reptile lineages have poorly-ossified limbs through

''Cartorhynchus'' had poorly-ossified limbs in spite of its well-ossified skull and vertebrae. However, Motani and colleagues suggested in 2014 that it was still an adult because many early-diverging members of marine reptile lineages have poorly-ossified limbs through paedomorphosis

Neoteny (), also called juvenilization,Montagu, A. (1989). Growing Young. Bergin & Garvey: CT. is the delaying or slowing of the physiological, or somatic, development of an organism, typically an animal. Neoteny is found in modern humans compared ...

(the retention of immature traits into adulthood), although they did not completely reject the possibility that it was a juvenile due to the existence of only one specimen.

In the case of ''Cartorhynchus'', Motani and colleagues proposed that the large, flipper-like forelimbs would have enabled it to move on land, thus making it amphibious. The extensive cartilage at the wrist joint would have allowed the flipper to bend without an elbow; juvenile sea turtles have similarly cartilaginous flippers that they use to move on land. Although its flipper would not have been particularly strong, ''Cartorhynchus'' was relatively lightweight, with a body mass to flipper surface area ratio smaller than that of ''Chaohusaurus''. The curved flippers would have allowed them to be kept close to the body, thus increasing their mechanical advantage

Mechanical advantage is a measure of the force amplification achieved by using a tool, mechanical device or machine system. The device trades off input forces against movement to obtain a desired amplification in the output force. The model for t ...

. Motani and colleagues suggested that other traits of ''Cartorhynchus'' would also have aided an amphibious lifestyle, including the short trunk and snout, and the thickened ribs (which would have served as a ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship, ...

, stabilizing the animal in near-shore waters).

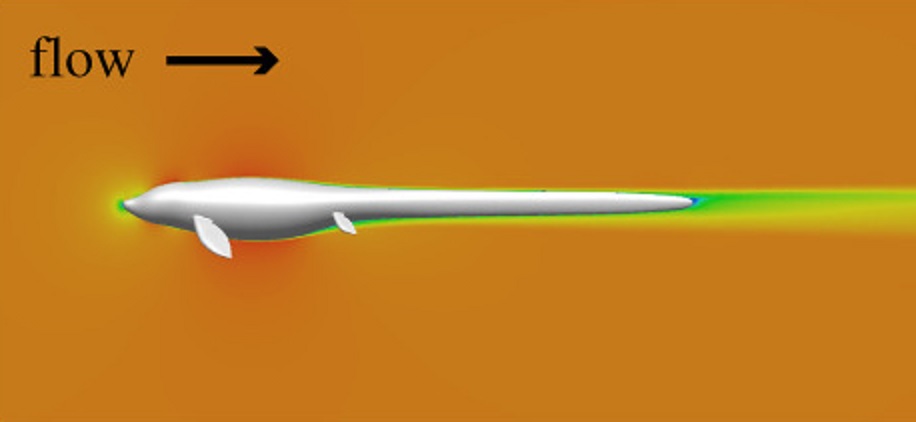

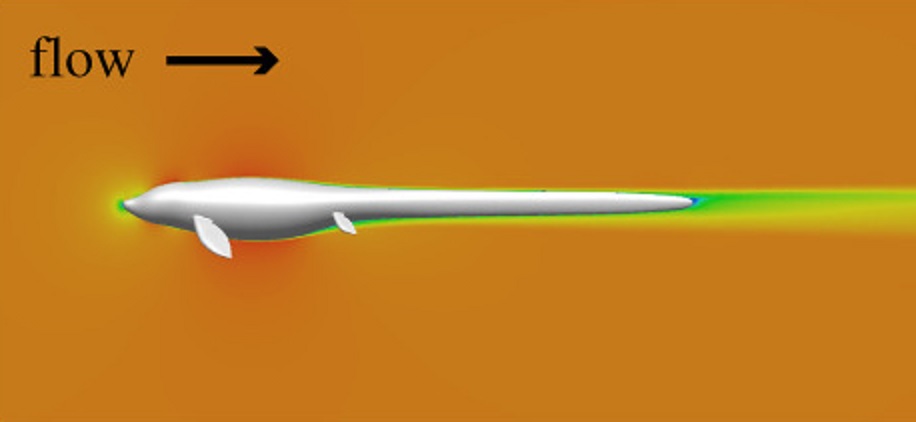

A 2019 study by Susana Gutarra and colleagues used computational simulations to estimate the energy cost of swimming in ichthyosauriforms. Early-diverging ichthyosauriforms with lizard-shaped bodies and elongate, flukeless tails, like ''Cartorhynchus'', would have employed

A 2019 study by Susana Gutarra and colleagues used computational simulations to estimate the energy cost of swimming in ichthyosauriforms. Early-diverging ichthyosauriforms with lizard-shaped bodies and elongate, flukeless tails, like ''Cartorhynchus'', would have employed anguilliform

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions of the fish's body a ...

(eel-like) swimming, while later ichthyosauriforms with deeper, fish-like bodies and well-defined tail flukes would have employed carangiform (mackerel-like) swimming. It is generally thought that anguilliform swimming is less efficient than carangiform swimming. Indeed, Gutarra and colleagues found that the energetic cost of swimming at was 24 to 42 times higher in ''Cartorhynchus'' than the ichthyosaur ''Ophthalmosaurus

''Ophthalmosaurus'' (meaning "eye lizard" in Greek) is an ichthyosaur of the Jurassic period (165–150 million years ago). Possible remains from the Cretaceous, around 145 million years ago, are also known. It was a relatively medium-sized ichth ...

'' (depending on whether swimming mode is accounted for), and its drag coefficient

In fluid dynamics, the drag coefficient (commonly denoted as: c_\mathrm, c_x or c_) is a dimensionless quantity that is used to quantify the drag or resistance of an object in a fluid environment, such as air or water. It is used in the drag equ ...

was 15% higher than that of the bottlenose dolphin

Bottlenose dolphins are aquatic mammals in the genus ''Tursiops.'' They are common, cosmopolitan members of the family Delphinidae, the family of oceanic dolphins. Molecular studies show the genus definitively contains two species: the common ...

. However, ''Cartorhynchus'' would have likely swam at slower speeds requiring less efficiency, and the advantages of carangiform swimming in later, larger ichthyosauriforms were also offset by increased body size.

Palaeoecology

Bed 633 of the Majiashan Quarry, the locality where ''Cartorhynchus'' was found, is a layer of grey

Bed 633 of the Majiashan Quarry, the locality where ''Cartorhynchus'' was found, is a layer of grey argillaceous

Clay minerals are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates (e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4), sometimes with variable amounts of iron, magnesium, alkali metals, alkaline earths, and other cations found on or near some planetary surfaces.

Clay minerals ...

(clay-bearing) limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

located above the base of the Upper Member of the Nanlinghu Formation. It is defined above and below by layers of yellowish marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part o ...

s. In terms of ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

biostratigraphy

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock Stratum, strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. “Biostratigraphy.” ''Oxford Reference: Dictiona ...

, this bed belongs to the '' Subcolumbites'' zone. High-resolution date estimates have been produced for the Olenekian-aged strata exposed in the Majiashan Quarry based on isotopic records of carbon-13

Carbon-13 (13C) is a natural, stable isotope of carbon with a nucleus containing six protons and seven neutrons. As one of the environmental isotopes, it makes up about 1.1% of all natural carbon on Earth.

Detection by mass spectrometry

A mass ...

cycling

Cycling, also, when on a two-wheeled bicycle, called bicycling or biking, is the use of cycles for transport, recreation, exercise or sport. People engaged in cycling are referred to as "cyclists", "bicyclists", or "bikers". Apart from two ...

and spectral gamma ray

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically ...

logs (which measure the amount of radiation in rocks of astronomical origin); Bed 633 in particular was estimated at 248.41 Ma in age. During the Middle Triassic, the Chaohu strata were deposited in an oceanic basin

In hydrology, an oceanic basin (or ocean basin) is anywhere on Earth that is covered by seawater. Geologically, ocean basins are large geologic basins that are below sea level.

Most commonly the ocean is divided into basins foll ...

relatively far from the coast, which was bordered on the south by shallower waters and carbonate platform

A carbonate platform is a sedimentary body which possesses topographic relief, and is composed of autochthonic calcareous deposits. Platform growth is mediated by sessile organisms whose skeletons build up the reef or by organisms (usually microb ...

s, and on the north by a continental slope

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges. The continental margin ...

and deeper basins.

The ichthyosauriforms ''Sclerocormus'' and ''Chaohusaurus'' are both found in Majiashan Quarry along with ''Cartorhynchus''; ''Sclerocormus'' is known from the younger Bed 719 (248.16 Ma), while ''Chaohusaurus'' is found in both beds. The sauropterygian '' Majiashanosaurus'' is known from Bed 643. Fish diversity in the Majiashan Quarry is poorer than other localities; the most common fish is '' Chaohuperleidus'', the oldest known member of the Perleidiformes

Perleidiformes are an extinct order of prehistoric ray-finned fish from the Triassic period Although numerous Triassic taxa have been referred to Perleidiformes, which ones should be included for it to form a monophyletic group is a matter of on ...

, but a species of the wide-ranging ''Saurichthys

''Saurichthys'' (from el, σαῦρος , 'lizard' and el, ἰχθῦς 'fish') is an extinct genus of predatory ray-finned fish from the Triassic period. It type genus family Saurichthyidae (Changhsingian- Middle Jurassic), and the larges ...

'' and several undescribed fish are also unknown. Potential invertebrate prey for ''Cartorhynchus'' include small ammonites and bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

s, and the thylacocephala

The Thylacocephala (from the Greek language, Greek or ', meaning "Bag, pouch", and or ' meaning "head") are a unique grouping of extinct probable Mandibulata, mandibulate arthropods, that have been considered by some researchers as having possi ...

n arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

'' Ankitokazocaris''.

See also

*''Sclerocormus

''Sclerocormus'' is an extinct genus of ichthyosauriform from the early Triassic period. The fossil was discovered in the central Anhui Province, China. It is currently only known from one specimen, however the fossil is mostly complete and as ...

''

*Ichthyosauriformes

The Ichthyosauriformes are a group of marine reptiles, belonging to the Ichthyosauromorpha, that lived during the Mesozoic.

The stem clade Ichthyosauriformes was in 2014 defined by Ryosuke Motani and colleagues as the group consisting of all ...

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q18511949 Early Triassic reptiles of Asia Prehistoric animals of China Ichthyosauromorph genera Fossil taxa described in 2014 Early Triassic genus first appearances Early Triassic genus extinctions Triassic ichthyosauromorphs