Capital and corporal punishment in Judaism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Capital punishment in traditional Jewish law has been defined in Codes of Jewish law dating back to medieval times, based on a system of oral laws contained in the Babylonian and

Capital punishment in traditional Jewish law has been defined in Codes of Jewish law dating back to medieval times, based on a system of oral laws contained in the Babylonian and

The institution of capital punishment in Jewish law is defined in the Law of Moses (Torah) in multiple places. The Mosaic Law provides for the death penalty to be inflicted upon those persons convicted of the following offences:

* adultery (for a married woman and her lover)

* bestiality

* blasphemy

*

The institution of capital punishment in Jewish law is defined in the Law of Moses (Torah) in multiple places. The Mosaic Law provides for the death penalty to be inflicted upon those persons convicted of the following offences:

* adultery (for a married woman and her lover)

* bestiality

* blasphemy

*

The principal tractate in the

The principal tractate in the

For some crimes, the Bible specifies which form of execution is to be used. Blasphemy, idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, witchcraft, prostitution by a betrothed virgin, or deceiving her husband at marriage as to her chastity (Deut. 22:21), and the rebellious son are punished with death by

For some crimes, the Bible specifies which form of execution is to be used. Blasphemy, idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, witchcraft, prostitution by a betrothed virgin, or deceiving her husband at marriage as to her chastity (Deut. 22:21), and the rebellious son are punished with death by

Death by stoning (סקילה, ''skila'') was issued for the transgression of one of eighteen crimes, among which being those who wantonly transgressed the Sabbath-day by breaking its laws (excluding those who may have broken the Sabbath laws unintentionally), as well as a male who had a licentious connection with another male. Stoning was administered by pushing the bound, convicted criminal over the side of a building, so that he fell down and died upon impact with the ground.

* Intercourse between a man and his mother.

* Intercourse between a man and his father's wife (not necessarily his mother).

* Intercourse between a man and his daughter in law.

* Intercourse with another man's wife from the first stage of marriage.

* Intercourse between two men.

* Bestiality.

* Cursing the name of God in God's name.

* Idol worship.

* Giving one's progeny to

Death by stoning (סקילה, ''skila'') was issued for the transgression of one of eighteen crimes, among which being those who wantonly transgressed the Sabbath-day by breaking its laws (excluding those who may have broken the Sabbath laws unintentionally), as well as a male who had a licentious connection with another male. Stoning was administered by pushing the bound, convicted criminal over the side of a building, so that he fell down and died upon impact with the ground.

* Intercourse between a man and his mother.

* Intercourse between a man and his father's wife (not necessarily his mother).

* Intercourse between a man and his daughter in law.

* Intercourse with another man's wife from the first stage of marriage.

* Intercourse between two men.

* Bestiality.

* Cursing the name of God in God's name.

* Idol worship.

* Giving one's progeny to

Capital Punishment

Jewish Virtual Library

The Death Penalty in Jewish Tradition

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Capital And Corporal Punishment (Judaism) Jewish courts and civil law Corporal punishments Punishments in religion Jewish ethics Judaism and capital punishment Jewish law Capital punishment Ethically disputed judicial practices Penology 1st century in law

Capital punishment in traditional Jewish law has been defined in Codes of Jewish law dating back to medieval times, based on a system of oral laws contained in the Babylonian and

Capital punishment in traditional Jewish law has been defined in Codes of Jewish law dating back to medieval times, based on a system of oral laws contained in the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud ( he, תַּלְמוּד יְרוּשַׁלְמִי, translit=Talmud Yerushalmi, often for short), also known as the Palestinian Talmud or Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century ...

, the primary source being the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' stoning Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times. The Torah and Ta ...

, b) burning by ingesting molten lead, c) strangling, and d) beheading, each being the punishment for specific offences. Except in special cases where a king can issue the death penalty, capital punishment in Jewish law cannot be decreed upon a person unless there were a minimum of twenty-three judges ('' stoning Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times. The Torah and Ta ...

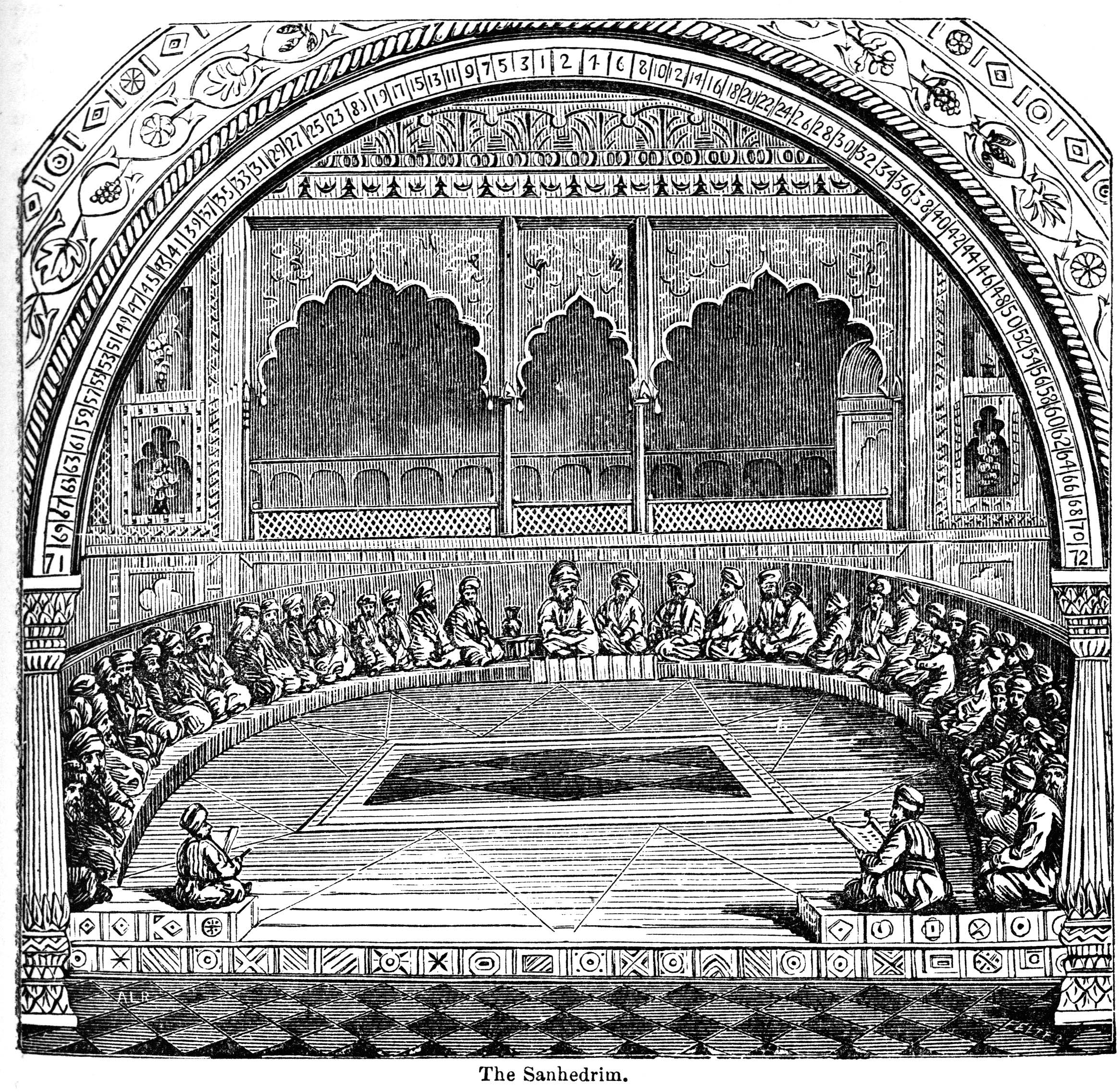

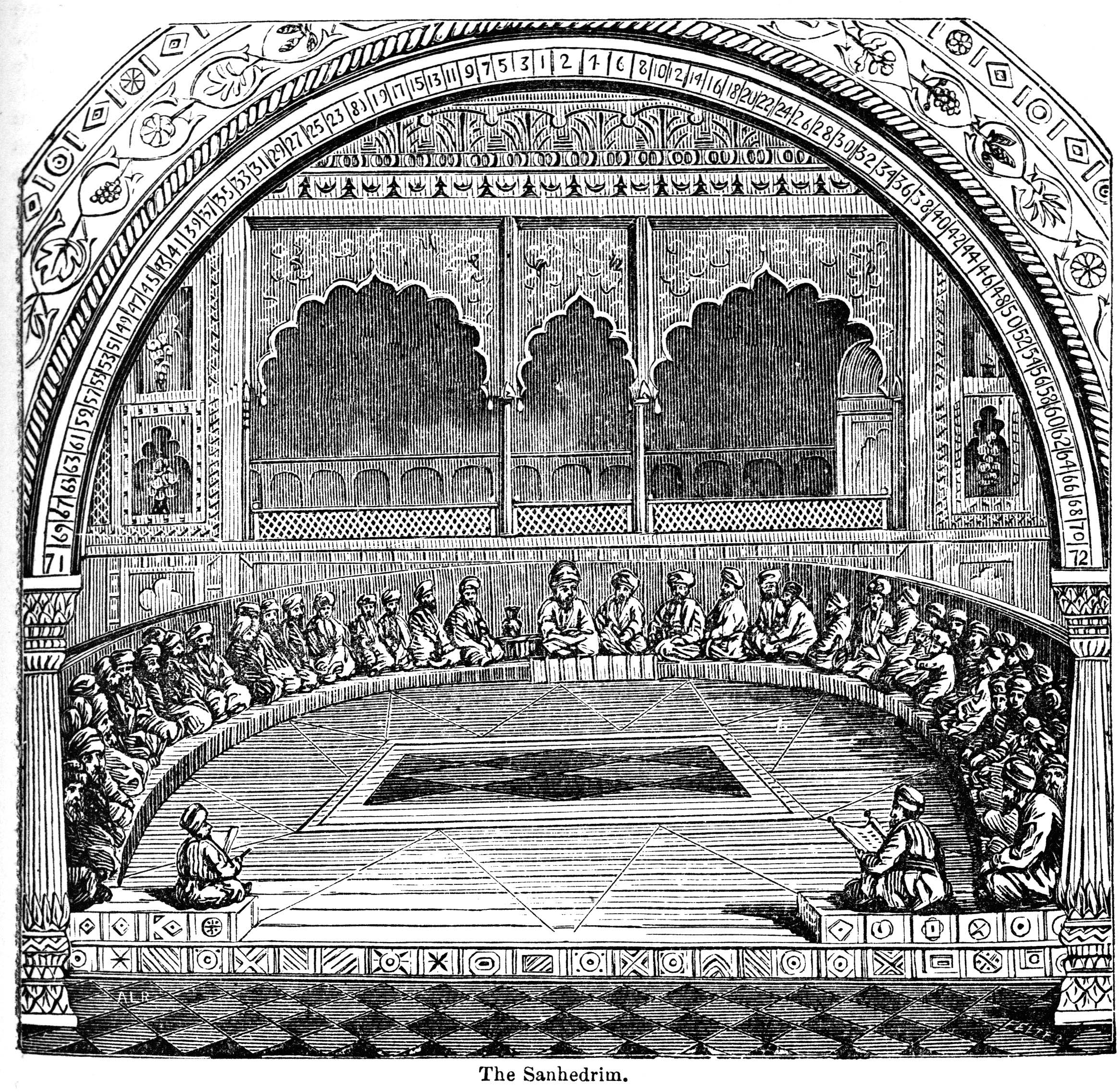

Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , ''synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), ...

) adjudicating in that person's trial who, by a majority vote, gave the death sentence, and where there had been at least two competent witnesses who testified before the court that they had seen the litigant commit the offence. Even so, capital punishment does not begin in Jewish law until the court adjudicating in this case had issued the death sentence from a specific place (formerly, the Chamber of Hewn Stone) on the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount ( hbo, הַר הַבַּיִת, translit=Har haBayīt, label=Hebrew, lit=Mount of the House f the Holy}), also known as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, lit. 'The Noble Sanctuary'), al-Aqsa Mosque compou ...

in the city of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

.

History

Capital and corporal punishment in Judaism has a complex history which has been a subject of extensive debate. The Bible and theTalmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

specify capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

by the "Four Executions of the Court," — stoning, burning, decapitation, and strangulation — for the most severe transgressions, and the corporal punishment of flagellation

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on ...

for intentional transgressions of negative commandments that do not incur one of the Four Executions. According to Talmudic law, the authority to apply capital punishment ceased with the destruction of the Second Temple. The Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tor ...

states that a Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , ''synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), ...

that executes one person in seven years — or seventy years, according to Eleazar ben Azariah

Eleazar ben Azariah ( he, אלעזר בן עזריה) was a 1st-century CE Jewish tanna, i.e. Mishnaic sage. He was of the second generation and a junior contemporary of Gamaliel II, Eliezer b. Hyrcanus, Joshua b. Hananiah, and Akiva.

Bio ...

— is considered bloodthirsty. During the Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

, the tendency of not applying the death penalty at all became predominant in Jewish courts. In practice, where medieval Jewish courts had the power to pass and execute death sentences, they continued to do so for particularly grave offenses, although not necessarily the ones defined by the law. While it was recognized that the use of capital punishment in the post-Second Temple era went beyond the biblical warrant, the rabbis who supported it believed that it could be justified by other considerations of Jewish law. Whether Jewish communities ever practiced capital punishment according to rabbinical law, and whether the rabbis of the Talmudic era ever supported its use even in theory, has been a subject of historical and ideological debate.

The 12th-century Jewish legal scholar Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

stated that "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death." Maimonides argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until convictions would be merely "according to the judge's caprice". Maimonides was concerned about the need for the law to guard itself in public perceptions, to preserve its majesty and retain the people's respect.

The position of Jewish Law on capital punishment often formed the basis of deliberations by Israel's Supreme Court. It has been carried out by Israel's judicial system only twice, in the cases of Adolf Eichmann and Meir Tobianski.

Capital punishment in classical sources

In the Pentateuch

child sacrifice

Child sacrifice is the ritualistic killing of children in order to please or appease a deity, supernatural beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of human ...

* false testimony in capital cases

* false prophecy

* proselytizing and promoting other religions

* male homosexual relations

* idolatry, actual or virtual

* incestuous relations

* insubordination to supreme authority

*lying about one's virginity upon marrying a spouse ()

* kidnapping

* licentiousness of a priest's daughter

* murder

* rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

committed against a betrothed woman

* striking, cursing, or otherwise rebelling against parental authority

* Sabbath-breaking

* touching Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai ( he , הר סיני ''Har Sinai''; Aramaic: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܣܝܢܝ ''Ṭūrāʾ Dsyny''), traditionally known as Jabal Musa ( ar, جَبَل مُوسَىٰ, translation: Mount Moses), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is ...

while God was giving Moses the Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ ...

* witchcraft, divination, necromancy, sorcery, etc.

In Rabbinic Judaism

The principal tractate in the

The principal tractate in the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

that deals with such cases is Tractate Sanhedrin.

Cases concerning offences punishable by death are decided by 23 judges. The reason for this odd number is that the early rabbis had learnt that it takes at least 10 judges to convict a man, and another 10 judges to acquit a man, and the court being unequal will result in a verdict rendered by majority vote. Strict regulations were in place as to how these judges were to be selected, based on their sex, age and family standing. For example, they could not appoint a judge who did not have children of his own, for he was thought to be less merciful towards other men's children. Neither could they select a judge who was not a male, by way of an edict, and which others say was because of the levity and temerity of the other sex. Nor could they admit the testimony of women in a court of Jewish law where the death-penalty hinged over the accused.

The harshness of the death penalty indicated the seriousness of the crime. Jewish philosophers argue that the whole point of corporal punishment was to serve as a reminder to the community of the severe nature of certain acts. This is why, in Jewish law, the death penalty is more of a principle than a practice. The numerous references to a death penalty in the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

underscore the severity of the sin, rather than the expectation of death. This is bolstered by the standards of proof required for application of the death penalty, which were extremely stringent. The ''Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tor ...

'' outlines the views of several prominent first-century CE rabbis on the subject:

"A Sanhedrin that puts a man to death once in seven years is called a murderous one. Rabbi Eliezer ben Azariah said, 'Or even once in 70 years.'The Talmud notes that "forty years before the destruction of the econdTemple, capital punishment ceased in Israel." This date is traditionally put at 28 CE, a time that corresponds with the 18th year ofRabbi Tarfon Rabbi Tarfon or Tarphon ( he, רבי טרפון, from the Greek Τρύφων ''Tryphon''), a Kohen, was a member of the third generation of the Mishnah sages, who lived in the period between the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE) and the ...and Rabbi Akiba said, 'If we had been in the Sanhedrin, no death sentence would ever have been passed'; Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel said, 'If so, they would have multiplied murderers in Israel.'"

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

' reign. At this time, the Sanhedrin required the approbation of the Roman procurator

Procurator (with procuracy or procuratorate referring to the office itself) may refer to:

* Procurator, one engaged in procuration, the action of taking care of, hence management, stewardship, agency

* ''Procurator'' (Ancient Rome), the title o ...

of Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous sou ...

before they could punish any malefactor by death. Other sources, such as Josephus, disagree. The issue is highly debated because of the relevancy to the New Testament trial of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

. Ancient rabbis did not like the idea of capital punishment, and interpreted the texts in a way that made the death penalty virtually non-existent.

Legal proceedings involving capital punishment were to be handled with extreme caution. In all cases of capital punishment in Jewish law, the judges are required to open their deliberations by pointing out the good qualities of the litigant and to bring up arguments why he should be acquitted. Only later did they hear the incriminating evidence. It was almost impossible to inflict the death penalty because the standards of proof were so high. As a result, convictions for capital offense were rare, but did happen in Judaism. The standards of evidence in capital cases include:

* Two witnesses were required. Acceptability was limited to:

** Adult Jewish men who were known to keep the commandments, knew the written and oral law, and had legitimate professions;

** The witnesses had to see each other at the time of the sin;

** The witnesses had to be able to speak clearly, without any speech impediment or hearing deficit (to ensure that the warning and the response were done);

** The witnesses could not be related to each other, or to the accused.

* The witnesses had to see each other, and both of them had to give a warning (''hatra'ah'') to the person that the sin they were about to commit was a capital offense;

* This warning had to be delivered within seconds of the performance of the sin (in the time it took to say, "Peace unto you, my Rabbi and my Master");

* In the same amount of time, the person about to sin had to both respond that s/he was familiar with the punishment, but they were going to sin anyway; ''and'' begin to commit the sin/crime;

*However, if the accused has already committed the crime, the accused would have been given a chance to repent (i.e. Ezekiel 18:27), and if they repeated the same crime, or any other, it would lead to a death sentence. If witnesses were caught lying about the crime, they would be executed.

* The Beth Din (rabbinical court) had to examine each witness separately; and if even one minor point of their evidence, such as eye color, was contradictory the evidence was considered contradictory, and the evidence was not heeded;

* The Beth Din had to consist of a minimum of 23 judges;

* The majority could not be a simple majority - the split verdict that would allow conviction had to be at least 13 to 10 in favor of conviction;

* If the Beth Din arrived at a unanimous verdict of guilty, the person was let go - the idea being that if no judge could find anything exculpatory about the accused, there was something wrong with the court.

* The witnesses were appointed by the court to be the executioners.

Where the death sentence was warranted but the court had not the jurisdiction to mete out the death sentence, such as when there were not two or more witnesses, the court had the authority to lock-up the convicted individual within a cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, most often dome-like, tall structure on top of a building. Often used to provide a lookout or to admit light and air, it usually crowns a larger roof or dome.

The word derives, via Italian, fro ...

, or similar confined structure, and to feed them meager portions of bread and water until they died.

Megillat Taanit

According to an oral teaching appearing in ''Megillat Taanit

''Megillat Taanit'' (Hebrew: ), lit. ''"the Scroll of Fasting,"'' is an ancient text, in the form of a chronicle, which enumerates 35 eventful days on which the Jewish nation either performed glorious deeds or witnessed joyful events. These days ...

'', the four modes of execution formerly used in Jewish law were mostly orally transmitted practices not explicitly stated in the Written Law

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the sa ...

of Moses, although some modes of punishment are explicitly stated. ''Megillat Taanit'' records that "On the fourth ayof he lunar month Tammuz, the book of decrees had been purged ()". The Hebrew commentary (scholion) on this line brings two different explanations of this event; according to one of the explanations, the "book of decrees" was composed by the Sadducees

The Sadducees (; he, צְדוּקִים, Ṣədūqīm) were a socio- religious sect of Jewish people who were active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE through the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. T ...

and used by them as proof concerning the four modes of capital punishment; the Pharisees and rabbis preferred to determine the punishments via orally transmitted interpretation of scripture.

Modes of punishment

The court had power to inflict four kinds of death-penalty:stoning Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times. The Torah and Ta ..., burning, beheading, and strangling.

For some crimes, the Bible specifies which form of execution is to be used. Blasphemy, idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, witchcraft, prostitution by a betrothed virgin, or deceiving her husband at marriage as to her chastity (Deut. 22:21), and the rebellious son are punished with death by

For some crimes, the Bible specifies which form of execution is to be used. Blasphemy, idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, witchcraft, prostitution by a betrothed virgin, or deceiving her husband at marriage as to her chastity (Deut. 22:21), and the rebellious son are punished with death by stoning

Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times.

The Torah and Ta ...

; bigamous marriage with a wife's mother and the prostitution of a priest's daughter are punished by burning; communal apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

is punished by the sword.

With reference to all other capital offenses, the law ordains that the perpetrator shall die a violent death, occasionally adding the expression, "His (their) blood shall be upon him (them)." This expression applies to death by stoning.

The Bible speaks also of hanging (Deut. 21:22), but (according to the rabbinical interpretation) not as a mode of execution, but rather of exposure after death.

The following is a list by Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

of the crimes punished by each form of capital punishment:

Punishment by stoning

Death by stoning (סקילה, ''skila'') was issued for the transgression of one of eighteen crimes, among which being those who wantonly transgressed the Sabbath-day by breaking its laws (excluding those who may have broken the Sabbath laws unintentionally), as well as a male who had a licentious connection with another male. Stoning was administered by pushing the bound, convicted criminal over the side of a building, so that he fell down and died upon impact with the ground.

* Intercourse between a man and his mother.

* Intercourse between a man and his father's wife (not necessarily his mother).

* Intercourse between a man and his daughter in law.

* Intercourse with another man's wife from the first stage of marriage.

* Intercourse between two men.

* Bestiality.

* Cursing the name of God in God's name.

* Idol worship.

* Giving one's progeny to

Death by stoning (סקילה, ''skila'') was issued for the transgression of one of eighteen crimes, among which being those who wantonly transgressed the Sabbath-day by breaking its laws (excluding those who may have broken the Sabbath laws unintentionally), as well as a male who had a licentious connection with another male. Stoning was administered by pushing the bound, convicted criminal over the side of a building, so that he fell down and died upon impact with the ground.

* Intercourse between a man and his mother.

* Intercourse between a man and his father's wife (not necessarily his mother).

* Intercourse between a man and his daughter in law.

* Intercourse with another man's wife from the first stage of marriage.

* Intercourse between two men.

* Bestiality.

* Cursing the name of God in God's name.

* Idol worship.

* Giving one's progeny to Molech

Moloch (; ''Mōleḵ'' or הַמֹּלֶךְ ''hamMōleḵ''; grc, Μόλοχ, la, Moloch; also Molech or Molek) is a name or a term which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the book of Leviticus. The Bible strongly co ...

(child sacrifice).

* Necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of magic or black magic involving communication with the dead by summoning their spirits as apparitions or visions, or by resurrection for the purpose of divination; imparting the means to foretell future even ...

sorcery.

* Pythonic sorcery.

* Attempting to convince another to worship idols.

* Instigating a community to worship idols.

* Witchcraft.

* Violating the Sabbath.

* Cursing one's own parent.

* Ben sorer umoreh, a stubborn and rebellious son.

Punishment by burning

Death by burning (שריפה, ''serefah'') was issued for ten offenses, including prostitution and bigamous relations with one's wife and their mother.Marcus Jastrow

Marcus Jastrow (June 5, 1829 – October 13, 1903) was a German-born American Talmudic scholar, most famously known for his authorship of the popular and comprehensive ''Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Babli, Talmud Yerushalmi and Midrashic L ...

, S. Mendelsohn, ''Jewish Encyclopedia'', s.v. Capital Punishment Perpetrators were not burnt at the stake, but rather molten lead was poured down the perpetrator's esophagus

The esophagus ( American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to ...

. Alternatively, the burning was inflicted after the perpetrator had been stoned, a precedent that was established in Achan's stoning.

According to Halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

, this punishment is conducted by pouring molten metal (lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, or a mixture of lead and tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

) into one's throat, rather than burning at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

.

* The daughter of a priest who completed the second stage of marriage commits adultery.

* Intercourse between a man and his daughter.

* Intercourse between a man and his daughter's daughter.

* Intercourse between a man and his son's daughter.

* Intercourse between a man and his wife's daughter (not necessarily his own daughter).

* Intercourse between a man and his wife's daughter's daughter.

* Intercourse between a man and his wife's son's daughter.

* Intercourse between a man and his mother in law.

* Intercourse between a man and his mother in law's mother.

* Intercourse between a man and his father in law's mother.

Punishment by the sword

Death by the sword (הרג, ''hereg'') was issued in two cases: for wanton murder and for communal apostasy ( idolatry). The perpetrators of these crimes were beheaded. * Unlawful premeditated murder. * Being a citizen of an Ir nidachat, a "city that has gone astray".Punishment by strangulation

Death by strangulation (חנק, ''chenek'') was issued for six crimes, among which being a man who had a forbidden connexion with another man's wife (adultery), and a person who willfully caused injury (bruise) to one of his/her parents. * Committingadultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

with another man's wife, when it does not fall under the above criteria.

* Wounding one's own parent.

* Kidnapping another Israelite

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

.

* Prophesying falsely.

* Prophesying in the name of other deities.

* A sage who is guilty of insubordination

Insubordination is the act of willfully disobeying a lawful order of one's superior. It is generally a punishable offense in hierarchical organizations such as the armed forces, which depend on people lower in the chain of command obeying ord ...

in front of the grand court in the Chamber of the Hewn Stone.

Contemporary attitudes towards capital punishment

Rabbinical courts have given up the ability to inflict any kind of physical punishment, and such punishments are left to the civil court system to administer. The modern institution of the death penalty, at least as practiced in the United States, is opposed by the major rabbinical organizations of Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Judaism. In a 2014 poll, 57 percent of Jews surveyed said they supported life in prison without the chance of parole over the death penalty for people convicted of murder.Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox RabbiAryeh Kaplan

Aryeh Moshe Eliyahu Kaplan ( he, אריה משה אליהו קפלן; October 23, 1934 – January 28, 1983) was an American Orthodox rabbi, author, and translator, best known for his Living Torah edition of the Torah. He became well known as ...

wrote: "In practice, ... these punishments were almost never invoked, and existed mainly as a deterrent and to indicate the seriousness of the sins for which they were prescribed. The rules of evidence and other safeguards that the Torah provides to protect the accused made it all but impossible to actually invoke these penalties ... the system of judicial punishments could become brutal and barbaric unless administered in an atmosphere of the highest morality and piety. When these standards declined among the Jewish people, the Sanhedrin ... voluntarily abolished this system of penalties.On the other hand, Rabbi

Moshe Feinstein

Moshe Feinstein ( he, משה פײַנשטיין; Lithuanian pronunciation: ''Moshe Faynshteyn''; en, Moses Feinstein; March 3, 1895 – March 23, 1986) was an American Orthodox rabbi, scholar, and ''posek'' (authority on ''halakha''—J ...

, in a letter to then-New York Governor Hugh Carey

Hugh Leo Carey (April 11, 1919 – August 7, 2011) was an American politician and attorney. He was a seven-term U.S. representative from 1961 to 1974 and the 51st governor of New York from 1975 to 1982. He was a member of the Democratic Part ...

, states:

"One who murders because the prohibition to kill is meaningless to him, and he is especially cruel, and so too when murderers and evil people proliferate, they he courtswould hould?judge apital punishmentto repair the issue ndto prevent murder – for this ction of the courtsaves the state."

According to Yaakov Elman, imprisonment of criminals was impractically expensive under the material conditions of ancient society, which meant that the death penalty and other corporal punishments were the only available options for severe crimes. Thus, use of the death penalty in ancient society would not necessarily imply that the Jewish tradition prefers it in wealthy modern society.

Conservative Judaism

In Conservative Judaism, the death penalty was the subject of aresponsum

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars i ...

by its Committee on Jewish Law and Standards

The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards is the central authority on halakha (Jewish law and tradition) within Conservative Judaism; it is one of the most active and widely known committees on the Conservative movement's Rabbinical Assembly. With ...

, which has gone on record as opposing the modern institution of the death penalty: "The Talmud ruled out the admissibility of circumstantial evidence in cases which involved a capital crime. Two witnesses were required to testify that they saw the action with their own eyes. A man could not be found guilty of a capital crime through his own confession or through the testimony of immediate members of his family. The rabbis demanded a condition of cool premeditation in the act of crime before they would sanction the death penalty; the specific test on which they insisted was that the criminal be warned prior to the crime, and that the criminal indicate by responding to the warning, that he is fully aware of his deed, but that he is determined to go through with it. In effect, this did away with the application of the death penalty. The rabbis were aware of this, and they declared openly that they found capital punishment repugnant to them… There is another reason which argues for the abolition of capital punishment. It is the fact of human fallibility. Too often, we learn of people who were convicted of crimes, and only later are new facts uncovered by which their innocence is established. The doors of the jail can be opened; in such cases, we can partially undo the injustice. But the dead cannot be brought back to life again. We regard all forms of capital punishment as barbaric and obsolete."

Reform Judaism

Since 1959, theCentral Conference of American Rabbis

The Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), founded in 1889 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the principal organization of Reform rabbis in the United States and Canada. The CCAR is the largest and oldest rabbinical organization in the world. I ...

and the Union for Reform Judaism

The Union for Reform Judaism (URJ), known as the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC) until 2003, founded in 1873 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, is the congregational arm of Reform Judaism in North America. The other two arms establishe ...

have formally opposed the death penalty. The Central Conference also resolved in 1979 that "both in concept and in practice, Jewish tradition found capital punishment repugnant", and there is no persuasive evidence "that capital punishment serves as a deterrent to crime".

Humanistic Judaism

Humanistic Judaism has no policy on the use of the death penalty.https://shj.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Volume-XLV-2016-Number-2-Change-Fear-and-Hope-in-the-Twenty-First-Century.pdfSee also

* Capital punishment in Israel *Death penalty in the Bible

Capital punishment in the Bible refers to instances in the Bible where death is called for as a punishment and also instances where it is proscribed or prohibited. The story of the woman taken in adultery at the start of John 8, is of little rel ...

* List of capital crimes in the Torah

* Religion and capital punishment

* Testimony in Jewish law

Notes

References

Further reading

Capital Punishment

Jewish Virtual Library

The Death Penalty in Jewish Tradition

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Capital And Corporal Punishment (Judaism) Jewish courts and civil law Corporal punishments Punishments in religion Jewish ethics Judaism and capital punishment Jewish law Capital punishment Ethically disputed judicial practices Penology 1st century in law