The military history of Canada comprises hundreds of years of armed actions in the territory encompassing modern Canada, and interventions by the

Canadian military

}

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF; french: Forces armées canadiennes, ''FAC'') are the unified military forces of Canada, including sea, land, and air elements referred to as the Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, and Royal Canadian Air Force.

...

in conflicts and

peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United N ...

worldwide. For thousands of years, the area that would become Canada was the site of sporadic intertribal conflicts among

Aboriginal peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. Beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, Canada was the site of

four colonial wars and two additional wars in Nova Scotia and Acadia between

New France and

New England; the conflicts spanned almost seventy years, as each allied with various First Nation groups.

In 1763, after the final colonial war—the

Seven Years' War—the British emerged victorious and the French civilians, whom the British hoped to assimilate, were declared "British Subjects". After the passing of the

Quebec Act in 1774, giving the

Canadians their first charter of rights under the new regime, the

northern colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

chose not to join the

American Revolution and remained loyal to the British crown. The Americans launched invasions in 1775 and 1812. On both occasions, the Americans were rebuffed by Canadian forces; however, this threat would remain well into the 19th century and partially facilitated

Canadian Confederation in 1867.

After Confederation, and amid much controversy, a full-fledged Canadian military was created. Canada, however, remained a British dominion, and Canadian forces joined their British counterparts in the

Second Boer War and the

First World War. While independence followed the

Statute of Westminster, Canada's links to Britain remained strong, and the British once again had the support of

Canadians during the

Second World War. Since then, Canada has been committed to multilateralism and has gone to war within large multinational

coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

s such as in the

Korean War, the

Gulf War, the

Kosovo War, and the

Afghan war

War in Afghanistan, Afghan war, or Afghan civil war may refer to:

*Conquest of Afghanistan by Alexander the Great (330 BC – 327 BC)

*Muslim conquests of Afghanistan (637–709)

*Conquest of Afghanistan by the Mongol Empire (13th century), see als ...

.

Indigenous

Indigenous warfare tended to be over tribal independence, resources, and personal and tribal honour—revenge for perceived wrongs committed against oneself or one's tribe.

Before

European colonization, indigenous warfare tended to be formal and ritualistic and entailed few casualties.

There is some evidence of much more violent warfare, even the complete genocide of some

First Nations groups by others, such as the total displacement of the

Dorset culture of Newfoundland by the

Beothuk.

Warfare was also common among

indigenous peoples of the Subarctic with sufficient population density.

groups of the northern Arctic extremes generally did not engage in direct warfare, primarily because of their small populations, relying instead on

traditional law to resolve conflicts.

Those captured in fights were not always killed; tribes often adopted captives to replace warriors lost during raids and battles,

and captives were also used for prisoner exchanges.

Slavery was hereditary, the slaves being

prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

and their descendants.

Slave-owning tribes of the fishing societies, such as the

Tlingit and

Haida

Haida may refer to:

Places

* Haida, an old name for Nový Bor

* Haida Gwaii, meaning "Islands of the People", formerly called the Queen Charlotte Islands

* Haida Islands, a different archipelago near Bella Bella, British Columbia

Ships

* , a 1 ...

, lived along the coast from what is now

Alaska to

California.

Among

indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast are composed of many nations and tribal affiliations, each with distinctive cultural and political identities. They share certain beliefs, traditions and prac ...

, about a quarter of the population were slaves.

The

first conflicts between Europeans and indigenous peoples may have occurred around 1003

CE, when parties of

Norsemen attempted to establish permanent settlements along the northeastern coast of North America (see

L'Anse aux Meadows).

According to

Norse sagas, the ''

Skrælings'' of

Vinland responded so ferociously that the newcomers eventually withdrew and gave up their plans to settle the area.

Prior to

French settlements in the

St. Lawrence River valley, the local

Iroquoian peoples were almost completely displaced, probably because of warfare with their neighbours the

Algonquin.

The

Iroquois League was established prior to major European contact. Most archaeologists and anthropologists believe that the League was formed sometime between 1450 and 1600.

Existing indigenous alliances would become important to the colonial powers in the struggle for North American hegemony during the 17th and 18th centuries.

After European arrival, fighting between indigenous groups tended to be bloodier and more decisive, especially as tribes became caught up in the economic and military rivalries of the European settlers. By the end of the 17th century, First Nations from the

northeastern woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands include Native American tribes and First Nation bands residing in or originating from a cultural area encompassing the northeastern and Midwest United States and southeastern Canada. It is part ...

,

eastern subarctic and the

Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which derives ...

(a people of joint First Nations and European descent

) had rapidly adopted the use of firearms, supplanting the traditional bow.

The adoption of firearms significantly increased the number of fatalities.

The bloodshed during conflicts was also dramatically increased by the uneven distribution of firearms and horses among competing indigenous groups.

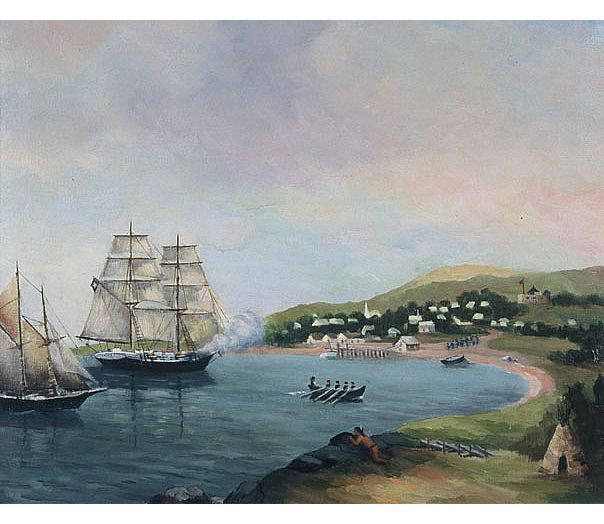

17th century

Five years after the French founded

Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and co ...

(see also

Port-Royal (Acadia)

Port-Royal (1629–1710) was a settlement on the site of modern-day Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, part of the French colony of Acadia. The original French settlement of Port-Royal (Habitation de Port-Royal (1605-1613, about southwest) had earl ...

and

Annapolis Royal) in 1605, the English began their first settlement, at

Cuper's Cove.

[ Kevin Major, ''As Near to Heaven by Sea: A History of Newfoundland and Labrador'', 2001, ] By 1706, the

French population was around 16,000 and grew slowly due to a multitude of factors.

This lack of immigration resulted in

New France having one-tenth of the British population of the

Thirteen Colonies by the mid 1700s.

's explorations had given France a claim to the

Mississippi River valley, where fur trappers and a few colonists set up scattered settlements. The colonies of New France:

Acadia on the Bay of Fundy and

Canada on the St. Lawrence River were based primarily on the fur trade and had only lukewarm support from the

French monarchy.

The colonies of

New France grew slowly given the difficult geographical and climatic circumstances.

The more favourably located

New England Colonies

The New England Colonies of British America included Connecticut Colony, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, and the Province of New Hampshire, as well as a few smaller short-lived colon ...

to the south developed a diversified economy and flourished from immigration.

From 1670, through the

Hudson's Bay Company, the English also laid claim to

Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

and its drainage basin (known as

Rupert's Land), and chartered several colonies and seasonal fishing settlements on Newfoundland.

The early

military of New France

The military of New France consisted of a mix of regular soldiers from the French Army (Carignan-Salières Regiment) and French Navy ( Troupes de la marine, later Compagnies Franches de la Marine) supported by small local volunteer militia units ...

consisted of a mix of regular soldiers from the French Army (

Carignan-Salières Regiment

The Carignan-Salières Regiment was a Piedmont French military unit formed by merging two other regiments in 1659. They were led by the new Governor, Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles, and Lieutenant-General Alexandre de Prouville, Sieur de Tracy. ...

) and French Navy (

Troupes de la marine and

Compagnies Franches de la Marine) supported by small local volunteer militia units (

Colonial militia

Colonial troops or colonial army refers to various military units recruited from, or used as garrison troops in, colonial territories.

Colonial background

Such colonies may lie overseas or in areas dominated by neighbouring land powers such ...

).

Most early troops were sent from France, but localization after the growth of the colony meant that, by the 1690s, many were volunteers from the settlers of New France, and by the 1750s most troops were descendants of the original French inhabitants.

Additionally, many of the early troops and officers who were born in France remained in the colony after their service ended, contributing to generational service and a military elite.

The

French built a series of forts from Newfoundland to Louisiana and others captured from the British during the 1600s to the late 1700s.

Some were a mix of military post and

trading forts.

Anglo-Dutch Wars

The

Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665 – 1667) was a conflict between

England and the

Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas and trade routes.

In 1664, a year before the Second Anglo-Dutch War began,

Michiel de Ruyter received instructions at

Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most pop ...

on 1 September 1664 to cross the Atlantic to attack English shipping in the West Indies and at the Newfoundland fisheries in reprisal for

Robert Holmes capturing several

Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ( ...

trading posts and ships on the

West African coast. Sailing north from Martinique in June 1665, De Ruyter proceeded to

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, capturing English merchant ships and taking the town of

St. John's before returning to Europe.

During the

Third Anglo-Dutch War, the inhabitants of St. John's fended off a second Dutch attack in 1673. The city was defended by Christopher Martin, an English merchant captain. Martin landed six cannons from his vessel, ''Elias Andrews'', and constructed an earthen breastwork and battery near Chain Rock commanding the Narrows leading into the harbour.

Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars (also known as the French and Iroquois Wars) continued intermittently for nearly a century, ending with the

Great Peace of Montreal in 1701.

The French under

Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons founded settlements at

Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and co ...

and

Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

three years later at

Quebec City, quickly joining pre-existing aboriginal alliances that brought them into conflict with other indigenous inhabitants.

Champlain joined a Huron–Algonquin alliance against the

Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

(Five/Six Nations).

In the first battle, superior French firepower rapidly dispersed a massed group of aboriginals. The Iroquois changed tactics by integrating their hunting skills and intimate knowledge of the terrain with their use of firearms obtained from the Dutch;

they developed a highly effective form of

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

, and were soon a significant threat to all but the handful of fortified cities. Furthermore, the French gave few guns to their aboriginal allies.

For the first century of the colony's existence, the chief threat to the inhabitants of New France came from the Iroquois Confederacy, and particularly from the easternmost

Mohawks

The Mohawk people ( moh, Kanienʼkehá꞉ka) are the most easterly section of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy. They are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous people of North America ...

.

While the majority of tribes in the region were allies of the French, the tribes of the Iroquois confederacy were aligned first with the

Dutch colonizers, then the

British.

In response to the Iroquois threat, the French government dispatched the

Carignan-Salières Regiment

The Carignan-Salières Regiment was a Piedmont French military unit formed by merging two other regiments in 1659. They were led by the new Governor, Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles, and Lieutenant-General Alexandre de Prouville, Sieur de Tracy. ...

, the first group of uniformed professional soldiers to set foot on what is today Canadian soil.

After peace was attained, this regiment was disbanded in Canada. The soldiers settled in the St. Lawrence valley and, in the late 17th century, formed the core of the

Compagnies Franches de la Marine, the local militia. Later militias were developed on the larger

seigneuries land systems.

Civil war in Acadia

In the mid-17th century,

Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war.

The war was between Port Royal, where Governor of Acadia

Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day

Saint John, New Brunswick, home of Governor

Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour

Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour (1593–1666) was a French colonist and fur trader who served as Governor of Acadia from 1631–1642 and again from 1653–1657.

Early life

Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour was born in France in 1593 to H ...

.

During the conflict, there were

four major battles. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640.

In response to the attack, d'Aulnay sailed out of Port Royal to establish a five-month blockade of La Tour's fort at Saint John, which La Tour eventually defeated in 1643.

La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643;

d'Aulnay and Port Royal ultimately won the war against La Tour with the 1645 siege of Saint John.

However, after d'Aulnay died in 1650, La Tour re-established himself in Acadia.

King William's War

During King William's War (1689–1697), the next most serious threat to Quebec in the 17th century came in 1690 when alarmed by the attacks of the ''petite guerre'',

the New England colonies sent an armed expedition north, under Sir

William Phips, to capture Quebec itself.

This expedition was poorly organized and had little time to achieve its objective, having arrived in mid-October, shortly before the St. Lawrence would freeze over.

The expedition was responsible for eliciting one of the most famous pronouncements in Canadian military history. When called on by Phips to surrender, the aged Governor

Frontenac replied, "I will answer ... only with the mouths of my cannon and the shots of my muskets."

After a single abortive landing on the

Beauport shore

Beauport is a borough of Quebec City, Quebec, Canada on the Saint Lawrence River.

Beauport is a northeastern suburb of Quebec City. Manufacturers include paint, construction materials, printers, and hospital supplies. Food transportation is impo ...

to the east of Quebec City, the English force withdrew down the icy waters of the St. Lawrence River.

During the war, the military conflicts in Acadia included:

Battle at Chedabucto (Guysborough)

The Battle of Chedabucto occurred against Fort St. Louis in Chedabucto (present-day Guysborough, Nova Scotia) on June 3, 1690 during King William's War (1689–97). The battle was part of Sir William Phips and New England's military campaign again ...

;

Battle of Port Royal (1690)

The Battle of Port Royal (19 May 1690) occurred at Port Royal, the capital of Acadia, during King William's War. A large force of New England provincial militia arrived before Port Royal. The Governor of Acadia Louis-Alexandre des Friches de M ...

; a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy (

Action of 14 July 1696);

Raid on Chignecto (1696)

The Raid on Chignecto occurred during King William's War when New England forces from Boston attacked the Isthmus of Chignecto, Acadia in present-day Nova Scotia. The raid was in retaliation for the French and Indian Siege of Pemaquid (1696) at ...

and

Siege of Fort Nashwaak (1696).

The

Maliseet

The Wəlastəkwewiyik, or Maliseet (, also spelled Malecite), are an Algonquian-speaking First Nation of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They are the indigenous people of the Wolastoq ( Saint John River) valley and its tributaries. Their territory ...

from their headquarters at

Meductic

Meductic is a small village located along the Saint John River in southern New Brunswick, approximately 33 kilometres southeast of Woodstock. Meductic's mayor is Lance Royden Graham.

History

During the Expulsion of the Acadians, the village w ...

on the Saint John River participated in numerous raids and battles against New England during the war.

In 1695,

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville was called upon to attack the English stations along the Atlantic coast of

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

in the

Avalon Peninsula Campaign.

Iberville sailed with his three vessels to

Placentia (Plaisance), the French capital of Newfoundland. Both English and French fishermen exploited the

Grand Banks fishery from their respective settlements on Newfoundland under the sanction of a 1687 treaty, but the purpose of the new French expedition of 1696 was nevertheless to expel the English from Newfoundland.

After setting fire to St John's, Iberville's Canadians almost totally destroyed the English fisheries along the eastern shore of Newfoundland.

Small raiding parties attacked the hamlets in remote bays and inlets, burning, looting, and taking prisoners.

By the end of March 1697, only

Bonavista and

Carbonear remained in English hands. In four months of raids, Iberville was responsible for the destruction of 36 settlements.

At the end of the war England returned the territory to France in the

Treaty of Ryswick.

18th century

During the 18th century, the British–French struggle in Canada intensified as the rivalry worsened in Europe.

The French government poured more and more military spending into its North American colonies. Expensive garrisons were maintained at distant fur trading posts, the fortifications of Quebec City were improved and augmented, and a new fortified town was built on the east coast of Île Royale, or

Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

—the

fortress of Louisbourg, called "Gibraltar of the North" or the "Dunkirk of America".

New France and New England were at war with one another three times during the 18th century.

The second and third colonial wars,

Queen Anne's War and

King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

, were local offshoots of larger European conflicts—the

War of the Spanish Succession (1702–13), the

War of the Austrian Succession (1744–48). The last, the

French and Indian War (

Seven Years' War), started in the Ohio Valley. The ''petite guerre'' of the Canadiens devastated the northern towns and villages of New England, sometimes reaching as far south as

Virginia.

The war also spread to the forts along the Hudson Bay shore.

Queen Anne's War

During Queen Anne's War (1702–1713), the British

conquered Acadia when a British force managed to capture

Port-Royal (see also

Annapolis Royal), the capital of Acadia in present-day Nova Scotia, in 1710.

On Newfoundland, the French attacked St. John's in 1705 (

Siege of St. John's

The siege of St. John's was a failed attempt by French forces led by Daniel d'Auger de Subercase to take the fort at St. John's, Newfoundland during the winter months of 1705, in Queen Anne's War. Leading a mixed force of regulars, militia, a ...

), and captured it in 1708 (

Battle of St. John's

The Battle of St. John's was the France, French capture of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John's, the capital of the Kingdom of Great Britain, British colony of Newfoundland, on , during Queen Anne's War. A mixed and motley force of ...

), devastating civilian structures with fire on each instance.

As a result, France was forced to cede control of Newfoundland and mainland Nova Scotia to Britain in the

Treaty of Utrecht (1713), leaving present-day

New Brunswick as disputed territory and Île-St. Jean (

Prince Edward Island), and

Île-Royale

The Salvation Islands (french: Îles du Salut, so called because the missionaries went there to escape plague on the mainland; sometimes mistakenly called Safety Islands) are a group of small islands of volcanic origin about off the coast of Fre ...

(present-day

Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

) in the hands of the French. British possession of Hudson Bay was guaranteed by the same treaty.

During Queen Anne's War, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included the

Raid on Grand Pré

The Raid on Grand Pré was the major action of a raiding expedition conducted by the New England militia Colonel Benjamin Church (ranger), Benjamin Church against French Acadia in June 1704, during Queen Anne's War. The expedition was allegedly ...

, the

Siege of Port Royal (1707), the

Siege of Port Royal (1710) and the

Battle of Bloody Creek (1711)

The Battle of Bloody Creek was fought on 10/21 June 1711 during Queen Anne's War. An Abenaki militia successfully ambushed British soldiers at a place that became known as Bloody Creek after the battles fought there. The creek empties into t ...

.

Father Rale's War

During the escalation that preceded

Father Rale's War (also known as Dummer's War), the

Mi'kmaq raided the new fort at

Canso

The Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO) is a representative body of companies that provide air traffic control. It represents the interests of Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs). CANSO members are responsible for supporting ov ...

(1720). Under potential siege, in May 1722 Lieutenant Governor

John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostages at

Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked.

In July 1722, the

Abenaki and Mi'kmaq created a blockade of Annapolis Royal with the intent of starving the capital.

The Mi'kmaq captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners in the area stretching from present-day

Yarmouth

Yarmouth may refer to:

Places Canada

*Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia

**Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

**Municipality of the District of Yarmouth

**Yarmouth (provincial electoral district)

**Yarmouth (electoral district)

* Yarmouth Township, Ontario

*New ...

to Canso.

As a result of the escalating conflict, Massachusetts Governor

Samuel Shute officially declared war on the

Abenaki on July 22, 1722. Early operations of Father Rale's War happened in the Nova Scotia theatre.

In July 1724, a group of sixty Mi'kmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal.

The treaty that ended the war marked a significant shift in European relations with the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet. For the first time, a European empire formally acknowledged that its dominion over Nova Scotia would have to be negotiated with the region's indigenous inhabitants. The treaty was invoked as recently as 1999 in the

Donald Marshall case.

King George's War

During King George's War, also called the War of the Austrian Succession (1744–1748), a force of New England militia under

William Pepperell

Sir William Pepperrell, 1st Baronet (27 June 1696 – 6 July 1759) was a merchant and soldier in colonial Massachusetts. He is widely remembered for organizing, financing, and leading the 1745 expedition that captured the French fortr ...

and Commodore

Peter Warren of the

Royal Navy succeeded in capturing Louisbourg in 1745.

By the

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that ended the war in 1748, France resumed control of Louisbourg in exchange for some of its conquests in the

Netherlands and

India. The New Englanders were outraged, and as a counterweight to the continuing French strength at Louisbourg, the British founded the military settlement of

Halifax in 1749.

During King George's War, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included:

Raid on Canso;

Siege of Annapolis Royal (1744); the

Siege of Louisbourg (1745); the

Duc d'Anville expedition and the

Battle of Grand Pré

The Battle of Grand Pré, also known as the Battle of Minas and the Grand Pré Massacre, was a battle in King George's War that took place between New England forces and Canadian, Mi'kmaq and Acadian forces at present-day Grand-Pré, Nova Scoti ...

.

Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755) was fought in Acadia and Nova Scotia by the British and New Englanders, primarily under the leadership of the New England

Ranger John Gorham and the British officer

Charles Lawrence,

against the Mi'kmaq and Acadians, who were led by French priest

Jean-Louis Le Loutre.

The war began when the British established

Halifax. As a result, Acadians and Mi'kmaq people orchestrated attacks at

Chignecto,

Grand-Pré,

Dartmouth Dartmouth may refer to:

Places

* Dartmouth, Devon, England

** Dartmouth Harbour

* Dartmouth, Massachusetts, United States

* Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada

* Dartmouth, Victoria, Australia

Institutions

* Dartmouth College, Ivy League university i ...

, Canso, Halifax and

Country Harbour.

The French erected forts at present-day Saint John, Chignecto and

Fort Gaspareaux. The British responded by attacking the Mi'kmaq and Acadians at Mirligueche (later known as Lunenburg), Chignecto and

St. Croix.

The British also established communities in Lunenburg and

Lawrencetown. Finally, the British erected forts in Acadian communities at Windsor, Grand-Pré and Chignecto.

Throughout the war, the Mi’kmaq and Acadians attacked the British fortifications of Nova Scotia and the newly established Protestant settlements. They wanted to retard British settlement and buy time for France to implement its Acadian resettlement scheme.

The war ended after six years with the defeat of the Mi'kmaq, Acadians and French in the

Battle of Fort Beauséjour

The Battle of Fort Beauséjour was fought on the Isthmus of Chignecto and marked the end of Father Le Loutre's War and

the opening of a British offensive in the Acadia/Nova Scotia theatre of the Seven Years' War, which would eventually lead to t ...

.

During this war, Atlantic Canada witnessed more population movements, more fortification construction, and more troop allocations than ever before in the region.

The Acadians and Mi'kmaq left Nova Scotia during the

Acadian Exodus

The Acadian Exodus (also known as the Acadian migration) happened during Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755) and involved almost half of the total Acadian population of Nova Scotia deciding to relocate to French controlled territories. The thr ...

for the French colonies of Île Saint-Jean (

Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (

Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

).

Seven Years' War

The fourth and final colonial war of the 18th century was the French and Indian War (1754–1763), a theatre of the Seven Years' War. The British sought to neutralize any potential military threat and to interrupt the vital supply lines to Louisbourg by deporting the Acadians. The British began the

Expulsion of the Acadians with the

Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755). During the next nine years, over 12,000 Acadians were removed from Nova Scotia.

In the maritime theatre, conflicts included:

Battle of Fort Beauséjour

The Battle of Fort Beauséjour was fought on the Isthmus of Chignecto and marked the end of Father Le Loutre's War and

the opening of a British offensive in the Acadia/Nova Scotia theatre of the Seven Years' War, which would eventually lead to t ...

; Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755); the

Battle of Petitcodiac; the

Raid on Lunenburg (1756)

The Raid on Lunenburg occurred during the French and Indian War when Mi'kmaw and Maliseet fighters attacked a British settlement at Lunenburg, Nova Scotia on May 8, 1756. The native militia raided two islands on the northern outskirts of the f ...

; the

Louisbourg Expedition (1757);

Battle of Bloody Creek (1757)

The Battle of Bloody Creek was fought on December 8, 1757, during the French and Indian War. An Acadian and Mi'kmaq militia defeated a detachment of British soldiers of the 43rd Regiment at Bloody Creek (formerly René Forêt River), which emp ...

;

Siege of Louisbourg (1758),

Petitcodiac River Campaign,

Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758),

St. John River Campaign

The St. John River campaign occurred during the French and Indian War when Colonel Robert Monckton led a force of 1150 British soldiers to destroy the Acadian settlements along the banks of the Saint John River until they reached the largest v ...

, and

Battle of Restigouche

The Battle of Restigouche was a naval battle fought in 1760 during the Seven Years' War (known as the French and Indian War in the United States) on the Restigouche River between the British Royal Navy and the small flotilla of vessels of the F ...

.

In the St. Lawrence and Mohawk theatres of the conflict, the French had begun to challenge the claims of Anglo-American

traders and

land speculators for supremacy in the

Ohio Country to the west of the

Appalachian Mountains—land that was claimed by some of the British colonies in their royal charters. In 1753, the French started the military occupation of the Ohio Country by building a series of forts. In 1755, the British sent two regiments to North America to drive the French from these forts, but these were

destroyed

Destroyed may refer to:

* ''Destroyed'' (Sloppy Seconds album), a 1989 album by Sloppy Seconds

* ''Destroyed'' (Moby album), a 2011 album by Moby

See also

* Destruction (disambiguation)

Destruction may refer to:

Concepts

* Destruktion, a ...

by

French Canadians

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

and First Nations as they approached

Fort Duquesne.

War was formally declared in 1756, and six French regiments of ''troupes de terre'', or

line infantry

Line infantry was the type of infantry that composed the basis of European land armies from the late 17th century to the mid-19th century. Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus are generally regarded as its pioneers, while Turenne and Monte ...

, came under the command of a newly arrived general, 44-year-old

Marquis de Montcalm.

Under their new commander, the French at first achieved a number of startling victories over the British, first at

Fort William Henry to the south of Lake Champlain.

The following year saw an even greater victory when the British army—numbering about 15,000 under Major General

James Abercrombie—was defeated in its attack on a French fortification at the

Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoniou ...

.

In June 1758, a British force of 13,000 regulars under Major General

Jeffrey Amherst

Field Marshal Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst, (29 January 1717 – 3 August 1797) was a British Army officer and Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in the British Army. Amherst is credited as the architect of Britain's successful campaig ...

, with

James Wolfe as one of his brigadiers, landed and permanently captured the

Fortress of Louisbourg.

Wolfe decided the next year to attempt the capture of Quebec City. After several botched landing attempts, including particularly bloody defeats at the

Battle of Beauport

The Battle of Beauport, also known as the Battle of Montmorency, fought on 31 July 1759, was an important confrontation between the British Armed Forces, British and French Armed Forces during the Seven Years' War (also known as the French and ...

and the Battle of Montmorency Camp, Wolfe succeeded in getting his army ashore, forming ranks on the

Plains of Abraham on September 12.

Montcalm, against the better judgment of his officers, came out with a numerically inferior force to meet the British. In the ensuing battle, Wolfe was killed, Montcalm mortally wounded, and 658 British and 644 French became casualties.

However, in the spring of 1760, the last French General,

François Gaston de Lévis

François-Gaston de Lévis, Duke of Lévis (20 August 1719 – 20 November 1787), styled as the Chevalier de Lévis until 1785, was a nobleman and a Marshal of France. He served with distinction in the War of the Polish Succession and the War o ...

, marched back to Quebec from Montreal and defeated the British at the

Battle of Sainte-Foy in a battle similar to that of the previous year; now the situation was reversed, with the French

laying siege to Quebec.

The siege lasted from 29 April until 15 May when British ships arrived to relieve the city which compelled Lévis to break off the siege and retreat.

The British were then able to launch the

Montreal Campaign in the Summer of 1760 and by September the city capitulated; French resistance seized and the British

Conquest of Canada

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent ...

was complete, this being confirmed by the

Treaty of Paris.

American Revolutionary War

With the French threat eliminated, Britain's American colonies became increasingly restive; they resented paying taxes to support a large military establishment when there was no obvious enemy.

This resentment was augmented by further suspicions of British motives when the Ohio Valley and other western territories previously claimed by France were not annexed to the existing British colonies, especially Pennsylvania and Virginia, which had long-standing claims to the region. Instead, under the Quebec Act, this territory was set aside for the First Nations. The American Revolutionary War (1776–1783) saw the revolutionaries use force to break free from British rule and claim these western lands.

In 1775, the

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

undertook its first military initiative of the war, the

invasion of the British

Province of Quebec. American forces took Montreal and the chain of forts in the Richelieu Valley, but attempts by the revolutionaries to

take Quebec City were repelled.

During this time, most French Canadians stayed neutral. After the British reinforced the province, a counter-offensive was launched pushing American forces back to

Fort Ticonderoga. The counter-offensive brought an end to the military campaign in Quebec and set the stage for the

military campaign in upstate New York and Vermont in 1777.

Throughout the war, American

privateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

devastated the maritime economy by raiding many of the coastal communities.

There were constant attacks by American and French privateers, such as the

Raid on Lunenburg (1782)

The Raid on Lunenburg (also known as the Sack of Lunenburg) occurred during the American Revolution when the US privateer, Captain Noah Stoddard of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, and four other privateer vessels attacked the British settlement at L ...

, numerous raids on

Liverpool, Nova Scotia

Liverpool is a Canadian community and former town located along the Atlantic Ocean of the Province of Nova Scotia's South Shore. It is situated within the Region of Queens Municipality which is the local governmental unit that comprises all ...

(October 1776, March 1777, September 1777, May 1778, September 1780) and a raid on

Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the n ...

(1781).

Privateers also raided Canso in 1775, returning in 1779 to destroy the fisheries.

To guard against such attacks, the

84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was garrisoned at forts around

Atlantic Canada

Atlantic Canada, also called the Atlantic provinces (french: provinces de l'Atlantique), is the region of Eastern Canada comprising the provinces located on the Atlantic coast, excluding Quebec. The four provinces are New Brunswick, Newfoundlan ...

.

Fort Edward (Nova Scotia)

Fort Edward is a National Historic Site of Canada in Windsor, Nova Scotia, (formerly known as Pisiguit) and was built during Father Le Loutre's War (1749-1755). The British built the fort to help prevent the Acadian Exodus from the region. The ...

in Windsor became the headquarters to prevent a possible American land assault on Halifax from the Bay of Fundy. There was an American attack on Nova Scotia by land, the

Battle of Fort Cumberland followed by the

Siege of Saint John (1777)

The St. John River expedition was an attempt by a small number of militia commanded by John Allan to bring the American Revolutionary War to Nova Scotia in late 1777. With minimal logistical support from Massachusetts and approximately 100 volu ...

.

During the war, American privateers captured 225 vessels either leaving or arriving at Nova Scotia ports.

In 1781, for example, as a result of the

Franco-American alliance

The Franco-American alliance was the 1778 alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States during the American Revolutionary War. Formalized in the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, it was a military pact in which the French provided many su ...

against Great Britain, there was

a naval engagement with a French fleet at

Sydney, Nova Scotia

Sydney is a former city and urban community on the east coast of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada within the Cape Breton Regional Municipality. Sydney was founded in 1785 by the British, was incorporated as a city in 1904, and dissolv ...

, near Spanish River, Cape Breton.

The British captured numerous American privateers, particularly in the

naval battle off Halifax

The Battle off Halifax took place on 28 May 1782 during the American Revolutionary War. It involved the American privateer ''Jack'' and the 14-gun Royal Naval brig off Halifax, Nova Scotia. Captain David Ropes commanded ''Jack'', and Lieut ...

. The Royal Navy used Halifax as a base from which to launch attacks on New England, such as the

Battle of Machias (1777).

The revolutionaries' failure to achieve success in what is now Canada, and the continuing allegiance to Britain of some colonists, resulted in the split of Britain's North American empire.

Many Americans who remained loyal to the Crown, known as the

United Empire Loyalists, moved north, greatly expanding the English-speaking population of what became known as

British North America.

The independent republic of the United States emerged to the south.

French Revolutionary Wars

During the

War of the First Coalition, a series of fleet manoeuvres and amphibious landings took place on the coasts of the

colony of Newfoundland

Newfoundland Colony was an English and, later, British colony established in 1610 on the island of Newfoundland off the Atlantic coast of Canada, in what is now the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. That followed decades of sporadic English ...

. The French expedition included seven

ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colum ...

and three frigates under Rear-Admiral

Joseph de Richery and was accompanied by a Spanish squadron made up of 10 ships of the line under the command of General

Jose Solano y Bote

Jose is the English transliteration of the Hebrew and Aramaic name ''Yose'', which is etymologically linked to ''Yosef'' or Joseph. The name was popular during the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods.

*Jose ben Abin

*Jose ben Akabya

* Jose the G ...

. The combined fleet sailed from

Rota

Rota or ROTA may refer to:

Places

* Rota (island), in the Marianas archipelago

* Rota (volcano), in Nicaragua

* Rota, Andalusia, a town in Andalusia, Spain

* Naval Station Rota, Spain

People

* Rota (surname), a surname (including a list of peop ...

, Spain, with the Spanish squadron accompanying the French squadron in an effort to ward off the British that had blockaded the French in Rota earlier that year. The expedition to Newfoundland was the last portion of

Richery's expedition before he returned to France.

Sighting of the combined naval squadron prompted defensives to be prepared at St. John's, Newfoundland in August 1796.

Seeing these defences, Richery opted to not attack the defended capital, instead moving south to raid the undefended settlements, fishing stations and vessels, and a garrison base at

Placentia Bay.

[ After the raids on Newfoundland, the squadron was split up, with half moving on to raid neighbouring Saint Pierre and Miquelon, while the other half moved to intercept the seasonal fishing fleets off the coast of Labrador.

]

19th century

War of 1812

After the cessation of hostilities at the end of the American Revolution, animosity and suspicion continued between the United States and the United Kingdom,

After the cessation of hostilities at the end of the American Revolution, animosity and suspicion continued between the United States and the United Kingdom,Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

's aid to do so.Niagara frontier

The Niagara Frontier refers to the stretch of land in the United States that is south of Lake Ontario and north of Lake Erie, and extends westward to Cleveland, Ohio. The term dates to the War of 1812, when the northern border was in contention b ...

was defeated at the Battle of Queenston Heights

The Battle of Queenston Heights was the first major battle in the War of 1812. Resulting in a British victory, it took place on 13 October 1812 near Queenston, Upper Canada (now Ontario).

The battle was fought between United States regulars wit ...

, where Sir Isaac Brock lost his life. In 1813, the US retook Detroit and had a string of successes along the western end of Lake Erie, culminating in the Battle of Lake Erie (September 10) and the

In 1813, the US retook Detroit and had a string of successes along the western end of Lake Erie, culminating in the Battle of Lake Erie (September 10) and the Battle of Moraviantown

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813 ...

or Battle of the Thames on October 5.Liverpool Packet

''Liverpool Packet'' was a privateer schooner from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, that captured 50 American vessels in the War of 1812. American privateers captured ''Liverpool Packet'' in 1813, but she failed to take any prizes during the four months bef ...

from Liverpool, Nova Scotia

Liverpool is a Canadian community and former town located along the Atlantic Ocean of the Province of Nova Scotia's South Shore. It is situated within the Region of Queens Municipality which is the local governmental unit that comprises all ...

, another privateer vessel, is credited with having captured fifty ships during the conflict.Deadman's Island, Halifax

Deadman's Island is a small peninsula containing a cemetery and park located in the Northwest Arm of Halifax Harbour in Nova Scotia, Canada. The area was first used as a training grounds for the British military, and later became a burial ground ...

.

Construction of defences

The fear that the Americans might again attempt to conquer Canada remained a serious concern for at least the next half century and was the chief reason for the retention of a large British garrison in the colony.Citadel Hill

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

in Halifax, and Fort Henry in Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the five most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

.Rideau Canal

The Rideau Canal, also known unofficially as the Rideau Waterway, connects Canada's capital city of Ottawa, Ontario, to Lake Ontario and the Saint Lawrence River at Kingston. It is 202 kilometres long. The name ''Rideau'', French for "curtain", ...

was built to allow ships in wartime to travel a more northerly route from Montreal to Kingston;

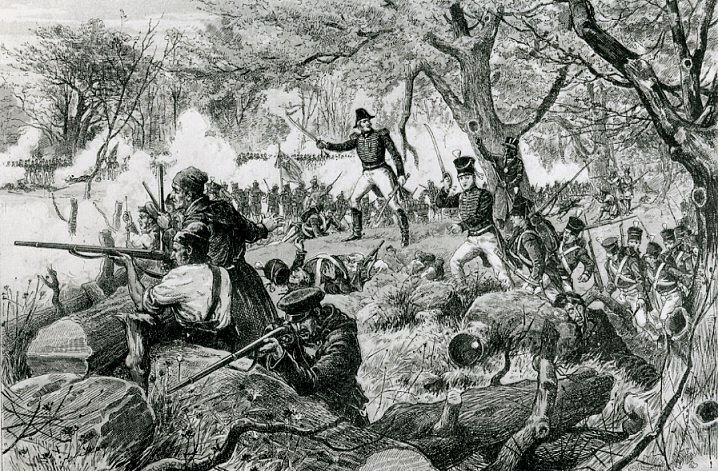

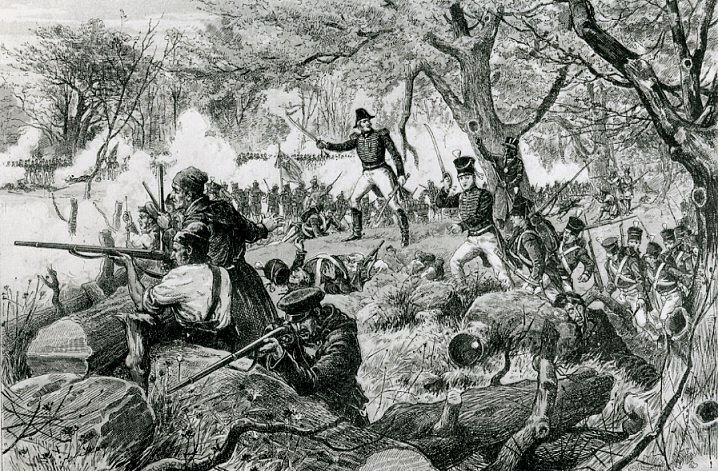

Rebellions of 1837

One of the most important actions by the British forces and Canadian Militia during this period was the putting down of the Rebellions of 1837, two separate rebellions from 1837 to 1838 in Lower Canada, and Upper Canada.

One of the most important actions by the British forces and Canadian Militia during this period was the putting down of the Rebellions of 1837, two separate rebellions from 1837 to 1838 in Lower Canada, and Upper Canada.Upper Canada Rebellion

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the rebellion in Lower Canada (p ...

was quickly and decisively defeated by the British forces and Canadian Militia.Battle of Pelee Island

The Battle of Pelee Island took place during the Patriot War along what is now the Michigan-Ontario border in 1838 involving small groups of men on each side of the border seeking to "liberate" Upper Canada from the British. Prelude

On February 2 ...

and the Battle of the Windmill. The Lower Canada Rebellion was a greater threat to the British, and the rebels were victorious at the Battle of St. Denis on November 23, 1837.Battle of Saint-Charles

The Battle of Saint-Charles was fought on 25 November 1837 between the Government of Lower Canada, supported by the United Kingdom, and Patriote rebels. Following the opening Patriote victory of the Lower Canada Rebellion at the Battle of Sai ...

, and on December 14, they were finally routed at the Battle of Saint-Eustache.

British withdrawal

By the 1850s, fears of an American invasion had begun to diminish, and the British felt able to start reducing the size of their garrison. The Reciprocity Treaty, negotiated between Canada and the United States in 1854, further helped to alleviate concerns.Trent Affair

The ''Trent'' Affair was a International incident, diplomatic incident in 1861 during the American Civil War that threatened a war between the United States and United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Great Britain. The United States Navy, ...

of late 1861 and early 1862,Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between ...

officials who were bound for Britain. The British government was outraged and, with war appearing imminent, took steps to reinforce its North American garrison, increasing it from a strength of 4,000 to 18,000.imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texa ...

strategy.

Enlistment in the British forces

Prior to Canadian Confederation, several regiments were raised in the Canadian colonies by the British Army, including the 40th Regiment of Foot

The 40th (the 2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1717 in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 82nd Regiment of Foot (Prince of Wales's Volunteers) ...

, and the 100th (Prince of Wales's Royal Canadian) Regiment of Foot

The 100th (Prince of Wales's Royal Canadian) Regiment of Foot was a British Army regiment, raised in 1858. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 109th Regiment of Foot (Bombay Infantry) to form the Prince of Wales's Leinster Regimen ...

. A number of Nova Scotians fought in the Crimean War, with the Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax, Nova Scotia, being the only Crimean War monument in North America. The monument itself is also the fourth oldest war monument in Canada, erected in 1860.Alexander Roberts Dunn

Alexander Roberts Dunn Victoria Cross, VC (15 September 1833 – 25 January 1868) was the first Canadian awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for bravery in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and C ...

, served in the war.black Canadian

Black Canadians (also known as Caribbean-Canadians or Afro-Canadians) are people of full or partial sub-Saharan African descent who are citizens or permanent residents of Canada. The majority of Black Canadians are of Caribbean origin, though t ...

and first black Nova Scotian, to receive the Victoria Cross.Siege of Lucknow

The siege of Lucknow was the prolonged defence of the British Residency within the city of Lucknow from rebel sepoys (Indian soldiers in the British East India Company's Army) during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. After two successive relief att ...

.

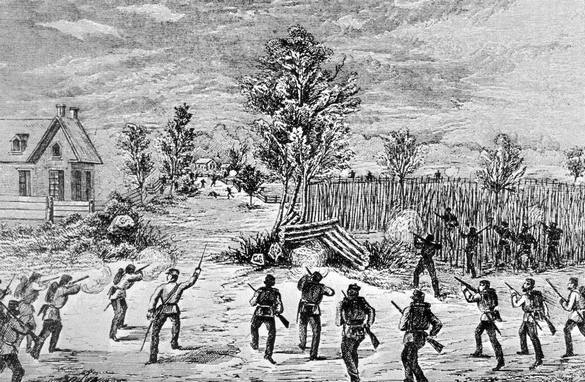

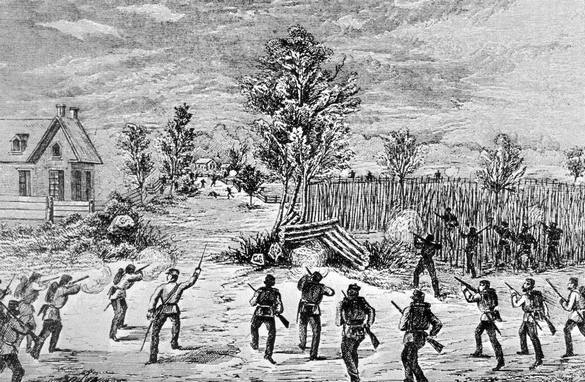

Fenian raids

It was during the period of re-examination of the British military presence in Canada and its ultimate withdrawal that the last invasion of Canada occurred. It was not carried out by any official US government force, but by an organization called the Fenians.

It was during the period of re-examination of the British military presence in Canada and its ultimate withdrawal that the last invasion of Canada occurred. It was not carried out by any official US government force, but by an organization called the Fenians.Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

or Ulster-Scots Ulster Scots, may refer to:

* Ulster Scots people

The Ulster Scots ( Ulster-Scots: ''Ulstèr-Scotch''; ga, Albanaigh Ultach), also called Ulster Scots people (''Ulstèr-Scotch fowk'') or (in North America) Scotch-Irish (''Scotch-Airisch'') ...

descent, and for the most part loyal to the British Crown.Northeastern States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

, and a large number of Irish American regiments had participated in the war. Thus, while deeply concerned about the Fenians, the US government, led by Secretary of State William H. Seward,

Canadian militia in the late–19th century

With Confederation in place and the British garrison gone, Canada assumed full responsibility for its own defence. The

With Confederation in place and the British garrison gone, Canada assumed full responsibility for its own defence. The Parliament of Canada

The Parliament of Canada (french: Parlement du Canada) is the federal legislature of Canada, seated at Parliament Hill in Ottawa, and is composed of three parts: the King, the Senate, and the House of Commons. By constitutional convention, the ...

passed the Militia Act of 1868, modelled after the earlier Militia Act of 1855

The ''Militia Act of 1855'' was an Act passed by the Parliament of the Province of Canada that permitted the formation of an "Active Militia", which was later subdivided into the Permanent Active Militia and the Non-Permanent Active Militia, and ...

, passed by the legislature of the Province of Canada. However, it was understood that the British would send aid in the event of a serious emergency and the Royal Navy continued to provide maritime defence.Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the five most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

.North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion (french: Rébellion du Nord-Ouest), also known as the North-West Resistance, was a resistance by the Métis people under Louis Riel and an associated uprising by First Nations Cree and Assiniboine of the District of S ...

in 1885 saw the largest military effort undertaken on Canadian soil since the end of the War of 1812:Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which derives ...

and their First Nations allies on one side against the Militia and North-West Mounted Police

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a Canadian para-military police force, established in 1873, to maintain order in the new Canadian North-West Territories (NWT) following the 1870 transfer of Rupert’s Land and North-Western Territory ...

on the other.Battle of Duck Lake

The Battle of Duck Lake (26 March 1885) was an infantry skirmish outside Duck Lake, Saskatchewan, between North-West Mounted Police forces of the Government of Canada, and the Métis militia of Louis Riel's newly established Provisional Govern ...

, the Battle of Fish Creek

The Battle of Fish Creek (also known as the Battle of Tourond's Coulée ), fought April 24, 1885 at Fish Creek, Saskatchewan, was a major Métis victory over the Canadian forces attempting to quell Louis Riel's North-West Rebellion. Although th ...

and the Battle of Cut Knife Hill

The Battle of Cut Knife, fought on May 2, 1885, occurred when a flying column of mounted police, militia, and Canadian army regular army units attacked a Cree and Assiniboine teepee settlement near Battleford, Saskatchewan. First Nations fight ...

.Battle of Loon Lake

The Battle of Loon Lake, also known as the Battle of Steele Narrows, concluded the North-West Rebellion on June 3, 1885, and was the last battle fought on Canadian soil. It was fought in what was then the District of Saskatchewan of the No ...

, which ended this conflict, is notable as the last battle to have been fought on Canadian soil. Government losses during the North-West Rebellion amounted to 58 killed and 93 wounded. In 1884, Britain for the first time asked Canada for aid in defending the empire, requesting experienced boatmen to help rescue Major-General Charles Gordon from the Mahdi uprising in the

In 1884, Britain for the first time asked Canada for aid in defending the empire, requesting experienced boatmen to help rescue Major-General Charles Gordon from the Mahdi uprising in the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

.Voyageur

The voyageurs (; ) were 18th and 19th century French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs via canoe during the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including the ' ...

s who were placed under the command of Canadian Militia officers.

20th century

Boer War

The issue of Canadian military assistance for Britain arose again during the Second Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa.

The issue of Canadian military assistance for Britain arose again during the Second Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa.Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

was adamantly in favour of raising 8,000 troops for service in South Africa.Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry

, colors =

, identification_symbol_2 = Maple Leaf (2nd Bn pipes and drums)

, identification_symbol_2_label = Tartan

, identification_symbol_4 = The RCR

, identification_symbol_4_label = Abbreviation

, mar ...

.The Royal Canadian Regiment

, colors =

, identification_symbol_2 = Maple Leaf (2nd Bn pipes and drums)

, identification_symbol_2_label = Tartan

, identification_symbol_4 = The RCR

, identification_symbol_4_label = Abbreviation

, mar ...

(as 2nd Canadian Contingent) and including the privately raised Strathcona's Horse

Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) (LdSH C is a regular armoured regiment of the Canadian Army and is Canada’s only tank regiment. Currently based in Edmonton, Alberta, the regiment is part of 3rd Canadian Division's 1 Canadian Mechanize ...

(as Third Canadian Contingent).Battle of Paardeberg

The Battle of Paardeberg or Perdeberg ("Horse Mountain") was a major battle during the Second Anglo-Boer War. It was fought near ''Paardeberg Drift'' on the banks of the Modder River in the Orange Free State near Kimberley.

Lord Methuen adv ...

, one of the first decisive victories of the war.Battle of Leliefontein

The Battle of Leliefontein (also known as the Battle of Witkloof) was an engagement between British-Canadian and Boer forces during the Second Boer War on 7 November 1900, at the Komati River south of Belfast at the present day Nooitgedacht Dam. ...

on November 7, 1900, three Canadians, Lieutenant Turner, Lieutenant Cockburn, Sergeant Holland and Arthur Richardson of the Royal Canadian Dragoons were awarded the Victoria Cross for protecting the rear of a retreating force.Harold Lothrop Borden

Lieutenant Harold Lothrop Borden (23 May 1876 – 16 July 1900) was from Canning, Nova Scotia and the only son of Canada's Minister of Militia and Defence (Canada), Minister of Defence and Militia, Frederick William Borden and related to future ...

, however, became the most famous Canadian casualty of the Second Boer War. About 7,400 Canadians,

Early 20th century military developments

From 1763 to prior to the Confederation of Canada in 1867, the British Army provided the main defence of Canada, although many Canadians served with the British in various conflicts.

From 1763 to prior to the Confederation of Canada in 1867, the British Army provided the main defence of Canada, although many Canadians served with the British in various conflicts.Army Pay Corps

The Royal Army Pay Corps (RAPC) was the corps of the British Army responsible for administering all financial matters. It was amalgamated into the Adjutant General's Corps in 1992.

History

The first "paymasters" have existed in the army before ...

(1906). Additional corps would be created in the years before and during the First World War, including the first separate military dental corps.

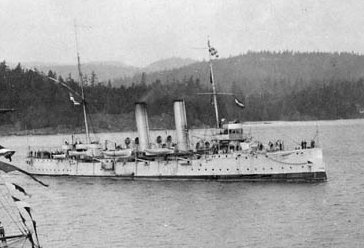

Creation of a Canadian navy

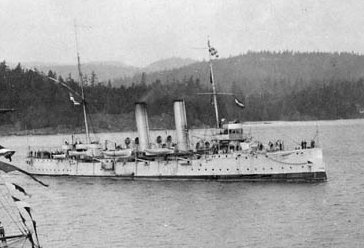

Canada had long had a small fishing protection force attached to the Department of Marine and Fisheries but relied on Britain for maritime protection. Britain was increasingly engaged in an

Canada had long had a small fishing protection force attached to the Department of Marine and Fisheries but relied on Britain for maritime protection. Britain was increasingly engaged in an arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and t ...

with Germany, and in 1908, asked the colonies for help with the navy.cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s and six destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s.

First World War

On August 4, 1914, Britain entered the First World War (1914–1918) by declaring war on Germany. The British declaration of war automatically brought Canada into the war, because of Canada's legal status as subservient to Britain.

On August 4, 1914, Britain entered the First World War (1914–1918) by declaring war on Germany. The British declaration of war automatically brought Canada into the war, because of Canada's legal status as subservient to Britain.Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was the expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed following Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on 15 August 1914, with an initial strength of one infantry division ...

was raised.Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

, Vimy, and Passchendaele battles and what later became known as "Canada's Hundred Days

Canada's Hundred Days is the name given to the series of attacks made by the Canadian Corps between 8 August and 11 November 1918, during the Hundred Days Offensive of World War I. Reference to this period as Canada's Hundred Days is due to the s ...

".Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December ...

was formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was the expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed following Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on 15 August 1914, with an initial strength of one infantry division ...

in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division

The 2nd Canadian Division (2 Cdn Div; french: 2e Division du Canada) is a formation of the Canadian Army in the province of Quebec, Canada. The present command was created 2013 when Land Force Quebec Area was re-designated. The main unit housed ...

in France.3rd Canadian Division

The 3rd Canadian Division is a formation of the Canadian Army responsible for the command and mobilization of all army units in the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, as well as all units extending westwards from th ...

in December 1915 and the 4th Canadian Division

The 4th Canadian Division is a formation of the Canadian Army. The division was first created as a formation of the Canadian Corps during the First World War. During the Second World War the division was reactivated as the 4th Canadian Infantr ...

in August 1916.[ The organization of a ]5th Canadian Division

The 5th Canadian Division is a formation of the Canadian Army responsible for the command and mobilization of most army units in the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador; as well as some unit ...

began in February 1917, but it was still not fully formed when it was broken up in February 1918 and its men used to reinforce the other four divisions.[ Although the corps was under the command of the British Army, there was considerable pressure among Canadian leaders, especially following the ]Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

, for the corps to fight as a single unit rather than spreading the divisions.[ Plans for a second Canadian corps and two additional divisions were scrapped, and a divisive national dialogue on conscription for overseas service was begun.]conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

was favourable in English Canada the idea was deeply unpopular in Quebec.Conscription Crisis of 1917

The Conscription Crisis of 1917 (french: Crise de la conscription de 1917) was a political and military crisis in Canada during World War I. It was mainly caused by disagreement on whether men should be conscripted to fight in the war, but also b ...

did much to highlight the divisions between French and English-speaking Canadians in Canada.Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

. For a nation of eight million people, Canada's war effort was widely regarded as remarkable. A total of 619,636 men and women served in the Canadian forces in the First World War, and of these 59,544 were killed and another 154,361 were wounded.

For a nation of eight million people, Canada's war effort was widely regarded as remarkable. A total of 619,636 men and women served in the Canadian forces in the First World War, and of these 59,544 were killed and another 154,361 were wounded.Vimy Memorial

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial is a war memorial site in France dedicated to the memory of Canadian Expeditionary Force members killed during the First World War. It also serves as the place of commemoration for Canadian soldiers of the First ...

and the distinctive brooding soldier at the Saint Julien Memorial

The St. Julien Memorial, also known as The Brooding Soldier, is a Canadian war memorial and small commemorative park located in the village of Saint-Julien, Langemark ( vls, Sint-Juliaan), Belgium. The memorial commemorates the Canadian First Di ...

. The other six follow a standard pattern of granite monuments surrounded by a circular path: the Hill 62 Memorial and Passchendaele Memorial

The Passchendaele Canadian Memorial (''also known as Crest Farm Canadian Memorial'') is a Canadian war memorial that commemorates the actions of the Canadian Corps in the Second Battle of Passchendaele of World War I. The memorial is located on th ...

in Belgium, and the Bourlon Wood Memorial

The Bourlon Wood Memorial, near Bourlon, France, is a Canadian war memorial that commemorates the actions of the Canadian Corps during the final months of the First World War; a period also known as Canada's Hundred Days, part of the Hundred ...

, Courcelette Memorial

The Courcelette Memorial is a Canadian war memorials, Canadian war memorial that commemorates the actions of the Canadian Corps in the final two and a half months of the infamous four-and-a-half-month-long Battle of the Somme, Somme Offensive of ...

, Dury Memorial

The Dury Memorial is a World War I Canadian war memorial that commemorates the actions of the Canadian Corps in the Second Battle of Arras

The Battle of Arras (also known as the Second Battle of Arras) was a British Empire, British offen ...

, and Le Quesnel Memorial

The Le Quesnel Memorial is a Canadian war memorial that commemorates the actions of the Canadian Corps during the 1918 Battle of Amiens during World War I. The battle marked the beginning of a 96-day period known as "Canada's Hundred Days" th ...

in France. There are also separate war memorials to commemorate the actions of the soldiers of Newfoundland (which did not join the Confederation until 1949) in the Great War. The largest is the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial and the Newfoundland National War Memorial in St. John's.[

In 1919, Canada sent a ]Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force (french: Corps expéditionnaire sibérien) (also referred to as the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia) or simply the C.S.E.F.) was a Canadian military force sent to Vladivostok, Russia, during the Ru ...

to aid the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War.

Creation of a Canadian air force

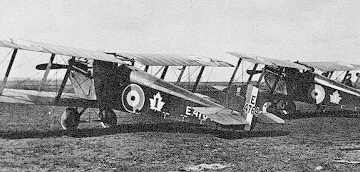

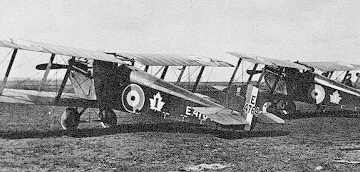

The First World War was the catalyst for the formation of Canada's air force. At the outbreak of war, there was no independent Canadian air force, although many Canadians flew with the

The First World War was the catalyst for the formation of Canada's air force. At the outbreak of war, there was no independent Canadian air force, although many Canadians flew with the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

and the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

.Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was the expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed following Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on 15 August 1914, with an initial strength of one infantry division ...

to Europe and consisted of one aircraft, a Burgess-Dunne, that was never used.Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environme ...

.

Spanish Civil War