Canadian Gaelic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Canadian Gaelic or Cape Breton Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig Chanada, or ), often known in Canadian English simply as Gaelic, is a collective term for the dialects of

/ref>Nova Scotia Office of Gaelic Affairs

/ref> In terms of the total number of speakers in the 2011 census, there were 7,195 total speakers of "Gaelic languages" in Canada, with 1,365 in

/ref> The 2016 census also reported that 240 residents of Nova Scotia and 15 on Prince Edward Island considered Scottish Gaelic to be their "mother tongue".Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Canada, Table: Detailed mother tongue

/ref> While there have been many different regional dialects of

BBC News 21 October 2010. Ultimately the population dropped from a peak of 200,000 in 1850, to 80,000 in 1900, to 30,000 in 1930 and 500–1,000 today. There are no longer entire communities of Canadian Gaelic-speakers, although traces of the language and pockets of speakers are relatively commonplace on Cape Breton, and especially in traditional strongholds like

A. W. R. MacKenzie founded the Nova Scotia Gaelic College at St Ann's in 1939.

A. W. R. MacKenzie founded the Nova Scotia Gaelic College at St Ann's in 1939.

Seanchaidh na Coille/Memory-Keeper of the Forest

'. Anthology of Scottish-Gaelic Literature of Canada in original Gaelic with English translation, with historical and literary commentary. *

Iomairtean na Gàidhlig

'. Gaelic Affairs Division, Government of Nova Scotia. *

Cainnt mo Mhàthar

'. Digital audio/visual archives of Canadian Gaels speaking Gaelic.

Virtual Museum Exhibit on Cape Breton Gaelic CultureWork through Time

Audio and text archive of Cape Breton histories.

Gaelic Economic-impact Study

Nova Scotia government report on Gaelic.

Gaelic Preservation Strategy

Nova Scotia government strategy proposal.

The Encyclopædia of Canada's Cultures: The Case of GaelicScottish Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and CraftsGaelic Map of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia Gaelic Visual Archives

* ttp://www.upei.ca/islandstudies/rep_mk_1.htm Gaelic in Prince Edward Islandbr>''Leugh Seo'' Gaelic Collection of the Cape Breton Library

Cape Breton Cèilidh

St Francis Xavier University Gaelic Resources

*Se Ceap Breatainn Tìr Mo Ghràidh''

Part One

an

Part Two

Scottish documentary on Canadian Gaelic-speaking community .

''Aiseirigh nan Gàidheal''

Canadian Gaelic radio show.

''Mac-Talla''

Canadian Gaelic newspaper, 540 issues.

''Fiosrachadh 'o'n Luchd-riaghlaidh mo Dheighinn Chanada''

1892. Book describing life in Canada, by ''Ùghdarras Pàrlamaid Chanada''.

''Machraichean Mòra Chanada''

1907. Book describing immigration to the Canadian Prairies.

White people, Indians, and Highlanders: tribal peoples and colonial encounters in Scotland and North America

Calloway, Colin Gordon.

Speaking Canadian English: an informal account of the English language in Canada

Orkin, Mark M.

Canadian History: Beginnings to Confederation

Taylor, Martin Brook & Owram, Doug.

Language in Canada

Edwards, John R.

Bilingualism and language deathTransactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness

Vol.s III & IV. 1873-4, 1874–5.

Na h-Albannaich agus Canada

19th century Ontario Gaelic song

''Comhairle na Gàidhlig''

– The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia Office of Gaelic Affairs

''Comunn Gàidhlig Bhancoubhair''

– The Gaelic Society of Vancouver (Canada)

Cainnt mo Mhàthar (My Mother's Language)

Extended recordings of native speakers

''Litir do Luchd-Ionnsachaidh''

2013 Canadian Gaelic Calendar

*

''The Gaels and their Place-Names in Nova Scotia''

- Interactive map of Nova Scotia showing Gaelic place names around the province {{Scottish Gaelic linguistics Languages of Canada Endangered diaspora languages Endangered Celtic languages Diaspora languages Language conflict in Canada

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well a ...

spoken in Atlantic Canada.

Scottish Gaels were settled in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

from 1773, with the arrival of the ship ''Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

''. and continuing until the 1850s. Gaelic has been spoken since then in Nova Scotia on Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

and on the northeastern mainland of the province. Scottish Gaelic is a member of the Goidelic

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically ...

branch of the Celtic languages

The Celtic languages (usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edwar ...

and the Canadian dialectics have their origins in the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland and Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act of 1886 ...

of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

. The parent language developed out of Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Eng ...

and is closely related to modern Irish

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

. The Canadian branch is a close cousin of the Irish language in Newfoundland. At its peak in the mid-19th century, there were as many as 200,000 speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Newfoundland Irish together, making it the third-most-spoken European language in Canada after English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national id ...

and French.

In Atlantic Canada today, there are approximately 2,000 speakers, mainly in Nova Scotia.Ethnologue – Canada, Scottish Gaelic/ref>Nova Scotia Office of Gaelic Affairs

/ref> In terms of the total number of speakers in the 2011 census, there were 7,195 total speakers of "Gaelic languages" in Canada, with 1,365 in

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

and Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

where the responses mainly refer to Scottish Gaelic.Statistics Canada, 2011 NHS Survey/ref> The 2016 census also reported that 240 residents of Nova Scotia and 15 on Prince Edward Island considered Scottish Gaelic to be their "mother tongue".Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Canada, Table: Detailed mother tongue

/ref> While there have been many different regional dialects of

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well a ...

that have been spoken in other communities across Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

, particularly in Glengarry County, Ontario

Glengarry County, an area covering , is a former county in the province of Ontario, Canada. It is historically known for its settlement of Scottish Gaels, Scottish Highlanders. Glengarry County now consists of the modern-day townships of North Gle ...

, Atlantic Canada is the only area in North America where Gaelic continues to be spoken as a community language, especially in Cape Breton. Even there the use of the language is precarious and its survival is being fought for. Even so, the Gaelic-speaking communities in Canada have contributed many great figures to the history of Scottish Gaelic literature

Scottish Gaelic literature refers to literature composed in the Scottish Gaelic language and in the Gàidhealtachd communities where it is and has been spoken. Scottish Gaelic is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages, along with Iris ...

, including Ailean a' Ridse MacDhòmhnaill and John MacLean during the days of early settlement and Lewis MacKinnon, whose Canadian Gaelic poetry won the Bardic Crown at the 2011 Royal National Mòd

The Royal National Mòd ( gd, Am Mòd Nàiseanta Rìoghail) is an Eisteddfod-inspired international Celtic festival focusing upon Scottish Gaelic literature, traditional music, and culture which is held annually in Scotland. It is the largest ...

at Stornoway

Stornoway (; gd, Steòrnabhagh; sco, Stornowa) is the main town of the Western Isles and the capital of Lewis and Harris in Scotland.

The town's population is around 6,953, making it by far the largest town in the Outer Hebrides, as well ...

.

Distribution

The Gaelic cultural identity community is a part of Nova Scotia's diverse peoples and communities. Thousands of Nova Scotians attend Gaelic-related activities and events annually including: language workshops and immersions, milling frolics, square dances, fiddle and piping sessions, concerts and festivals. Up until about the turn of the 20th century, Gaelic was widely spoken on easternPrince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

(PEI). In the 2011 Canadian Census, 10 individuals in PEI cited that their mother tongue was a Gaelic language, with over 90 claiming to speak a Gaelic language.

Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic lan ...

, and their language and culture, have influenced the heritage of Glengarry County and other regions in present-day Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

, where many Highland Scots

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sc ...

settled commencing in the 18th century, and to a much lesser extent the provinces of New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic Canad ...

, Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

(especially the Codroy Valley

The Codroy Valley is a valley in the southwestern part of the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Codroy Valley is a glacial valley formed in the Anguille Mountains, a sub-range of the Long Range Mou ...

), Manitoba

, image_map = Manitoba in Canada 2.svg

, map_alt = Map showing Manitoba's location in the centre of Southern Canada

, Label_map = yes

, coordinates =

, capital = Win ...

and Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

. Gaelic-speaking poets in communities across Canada have produced a large and significant branch of Scottish Gaelic literature

Scottish Gaelic literature refers to literature composed in the Scottish Gaelic language and in the Gàidhealtachd communities where it is and has been spoken. Scottish Gaelic is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages, along with Iris ...

comparable to that of Scotland itself.

History

Arrival of earliest Gaels

In 1621,King James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

allowed privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

William Alexander William or Bill Alexander may refer to:

Literature

*William Alexander (poet) (1808–1875), American poet and author

* William Alexander (journalist and author) (1826–1894), Scottish journalist and author

*William Alexander (author) (born 1976), ...

to establish the first Scottish colony overseas. The group of Highlanders – all of whom were Gaelic-speaking – were settled at what is presently known as Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping an ...

, on the western shore of Nova Scotia.

Within a year the colony had failed. Subsequent attempts to relaunch it were cancelled when in 1631 the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye returned Nova Scotia to French rule.

Almost a half-century later, in 1670, the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trade, fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake b ...

was given exclusive trading

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

rights to all North American lands draining into Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

– about 3.9 million km2 (1.5 million sq mi – an area larger than India). Many of the traders who came in the later 18th and 19th centuries were Gaelic speakers from the Scottish Highlands who brought their language to the interior.

Those who intermarried with the local First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

** First Nat ...

people passed on their language, with the effect that by the mid-18th century there existed a sizeable population of Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which deri ...

traders with Scottish and aboriginal ancestry, and command of spoken Gaelic.

Gaels in 18th- and 19th-century settlements

Cape Breton remained the property of France until 1758 (although mainland Nova Scotia had belonged to Britain since 1713) whenFortress Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (french: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two sieg ...

fell to the British, followed by the rest of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to King ...

in the ensuing Battle at the . As a result of the conflict Highland regiments

A Scottish regiment is any regiment (or similar military unit) that at some time in its history has or had a name that referred to Scotland or some part thereof, and adopted items of Scottish dress. These regiments were created after the Acts ...

who fought for the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

secured a reputation for tenacity and combat prowess. In turn the countryside itself secured a reputation among the Highlanders for its size, beauty, and wealth of natural resources.

They would remember Canada when the earliest of the Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( gd, Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resul ...

by the increasingly Anglicized Scottish nobility began to evict Gaelic-speaking tenants en masse from their ancestral lands in order to replace them with private deer-stalking estates and herds of sheep.

The first ship loaded with Hebridean colonists arrived at Île-St.-Jean (Prince Edward Island) in 1770, with later ships following in 1772, and 1774. In September 1773 a ship named ''The Hector'' landed in Pictou

Pictou ( ; Canadian Gaelic: ''Baile Phiogto'') is a town in Pictou County, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Located on the north shore of Pictou Harbour, the town is approximately 10 km (6 miles) north of the larger town of New Gl ...

, Nova Scotia, with 189 settlers who departed from Loch Broom

Loch Broom ( gd, Lochbraon, "loch of rain showers") is a sea loch located in northwestern Ross and Cromarty, in the former parish of Lochbroom, on the west coast of Scotland. The small town of Ullapool lies on the eastern shore of the loch.

Li ...

. In 1784 the last barrier to Scottish settlement – a law restricting land-ownership on Cape Breton Island – was repealed, and soon both PEI and Nova Scotia were predominantly Gaelic-speaking. Between 1815 and 1870, it is estimated that more than 50,000 Gaelic settlers immigrated to Nova Scotia alone. Many of them left behind poetry and other works of Scottish Gaelic literature

Scottish Gaelic literature refers to literature composed in the Scottish Gaelic language and in the Gàidhealtachd communities where it is and has been spoken. Scottish Gaelic is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages, along with Iris ...

.

The poet Mìcheal Mór MacDhòmhnaill

Micheal is a masculine given name. It is sometimes an anglicized form of the Irish names Micheál, Mícheál and Michéal; or the Scottish Gaelic name Mìcheal. It is also a spelling variant of the common masculine given name '' Michael'', and is ...

emigrated from South Uist

South Uist ( gd, Uibhist a Deas, ; sco, Sooth Uist) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the ...

to Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18 ...

around 1775 and a poem describing his first winter there survives. Anna NicGillìosa

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 1221) ...

emigrated from Morar

Morar (; gd, Mòrar) is a small village on the west coast of Scotland, south of Mallaig. The name Morar is also applied to the northern part of the peninsula containing the village, though North Morar is more usual (the region to the south we ...

to Glengarry County, Ontario

Glengarry County, an area covering , is a former county in the province of Ontario, Canada. It is historically known for its settlement of Scottish Gaels, Scottish Highlanders. Glengarry County now consists of the modern-day townships of North Gle ...

in 1786 and a Gaelic poem in praise of her new home also survives. Lord Selkirk's settler Calum Bàn MacMhannain Calum is a given name. It is a variation of the name Callum, which is a Scottish Gaelic name that commemorates the Latin name Columba, meaning "dove".

It may refer to:

*Calum Angus (born 1986), English footballer

*Calum Best (born 1981), British/A ...

, alias Malcolm Buchanan, left behind the song-poem ''Òran an Imrich'' ("The Song of Emigration"), which describes his 1803 voyage from the Isle of Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye (; gd, An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or ; sco, Isle o Skye), is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated b ...

to Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingd ...

, Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

and his impressions of his new home as ''Eilean an Àigh'' ("The Island of Prosperity"). Ailean a' Ridse MacDhòmhnaill (Allan The Ridge MacDonald) emigrated with his family from Ach nan Comhaichean, Glen Spean, Lochaber

Lochaber ( ; gd, Loch Abar) is a name applied to a part of the Scottish Highlands. Historically, it was a provincial lordship consisting of the parishes of Kilmallie and Kilmonivaig, as they were before being reduced in extent by the creati ...

to Mabou

Mabou is an unincorporated settlement in the Municipality of the County of Inverness on the west coast of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. The population in 2011 was 1,207 residents. It is the site of The Red Shoe pub, the An Drochaid ...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

in 1816 and composed many works of Gaelic poetry as a homesteader in Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18 ...

and in Antigonish County

, nickname =

, settlement_type = County

, motto =

, image_skyline = Antigonish Harbour Panorama2.jpg

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, flag_size ...

. The most prolific emigre poet was John MacLean of Caolas, Tiree

Tiree (; gd, Tiriodh, ) is the most westerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The low-lying island, southwest of Coll, has an area of and a population of around 650.

The land is highly fertile, and crofting, alongside tourism, and ...

, the former Chief Bard to the 15th Chief of Clan MacLean of Coll

Coll (; gd, Cola; sco, Coll)Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 31 is an island located west of the Isle of Mull in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Coll is known for its sandy beaches, which rise to form large sand dunes, for its corncrakes, and f ...

, who emigrated with his family to Nova Scotia in 1819.

MacLean, whom Robert Dunbar once dubbed, "perhaps the most important of all the poets who emigrated during the main period of Gaelic overseas emigration", composed one of his most famous song-poems, ("A Song to America"), which is also known as ("The Gloomy Forest"), after emigrating from Scotland to Canada. The poem has since been collected and recorded from seanchaithe in both Scotland and the New World.

According to Michael Newton, however, , which is, "an expression of disappointment and regret", ended upon becoming, "so well established in the emigrant repertoire that it easily eclipses his later songs taking delight in the Gaelic communities in Nova Scotia and their prosperity."

In the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland and Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act of 1886 ...

, MacLean is commonly known as "The Poet to the Laird of Coll" () or as "John, son of Allan" (). In Nova Scotia, he is known colloquially today as, "The Bard MacLean" () or as "The Barney's River Poet" (), after MacLean's original family homestead in Pictou County, Nova Scotia

Pictou County is a county in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada. It was established in 1835, and was formerly a part of Halifax County from 1759 to 1835. It had a population of 43,657 people in 2021, a decline of 0.2 percent from 2016. Furthermo ...

.

With the end of the American War of Independence, immigrants newly arrived from Scotland were joined in Canada by so-called "United Empire Loyalist

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America du ...

" refugees fleeing persecution and the seizure of their land claims by American Patriots. These settlers arrived on a mass scale at the arable lands of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

, with large numbers settling in Glengarry County in present-day Ontario, and in the Eastern Townships

The Eastern Townships (french: Cantons de l'Est) is an historical administrative region in southeastern Quebec, Canada. It lies between the St. Lawrence Lowlands and the American border, and extends from Granby in the southwest, to Drummondv ...

of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

.

Unlike in the Gaelic-speaking settlements along the Cape Fear River

The Cape Fear River is a long blackwater river in east central North Carolina. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Fear, from which it takes its name. The river is formed at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River (North Ca ...

in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

, there was no Gaelic printing press in Canada. For this reason, in 1819, Rev. Seumas MacGriogar, the first Gaelic-speaking Presbyterian minister

Presbyterian (or presbyteral) polity is a method of church governance ("ecclesiastical polity") typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session or ...

appointed to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

, had to publish his collection of Christian poetry

Christian poetry is any poetry that contains Christian teachings, themes, or references. The influence of Christianity on poetry has been great in any area that Christianity has taken hold. Christian poems often directly reference the Bible, while ...

in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

.

Printing presses soon followed, though, and the first Gaelic-language books printed in Canada, all of which were Presbyterian religious books, were published at Pictou, Nova Scotia

Pictou ( ; Canadian Gaelic: ''Baile Phiogto'') is a town in Pictou County, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Located on the north shore of Pictou Harbour, the town is approximately 10 km (6 miles) north of the larger town of New Gla ...

and Charlottetown

Charlottetown is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island, and the county seat of Queens County. Named after Queen Charlotte, Charlottetown was an unincorporated town until it was incorporated as a city i ...

, Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

in 1832. The first Gaelic language books published in Toronto and Montreal, which were also Presbyterian religious books, appeared between 1835 and 1836. The first Catholic religious books published in the Gaelic-language were printed at Pictou in 1836.

Red River colony

In 1812,Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas th ...

obtained to build a colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

at the forks of the Red River, in what would become Manitoba

, image_map = Manitoba in Canada 2.svg

, map_alt = Map showing Manitoba's location in the centre of Southern Canada

, Label_map = yes

, coordinates =

, capital = Win ...

. With the help of his employee and friend, Archibald McDonald

Archibald McDonald (3 February 1790 – 15 January 1853) was chief trader for the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Langley, Fort Nisqually and Fort Colvile and one-time deputy governor of the Red River Colony.

Early life

McDonald was born in Le ...

, Selkirk sent over 70 Scottish settlers, many of whom spoke only Gaelic, and had them establish a small farming colony there. The settlement soon attracted local First Nations groups, resulting in an unprecedented interaction of Scottish (Lowland

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of p ...

, Highland

Highlands or uplands are areas of high elevation such as a mountainous region, elevated mountainous plateau or high hills. Generally speaking, upland (or uplands) refers to ranges of hills, typically from up to while highland (or highlands) is ...

, and Orcadian), English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national id ...

, Cree, French, Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

, Saulteaux

The Saulteaux (pronounced , or in imitation of the French pronunciation , also written Salteaux, Saulteau and other variants), otherwise known as the Plains Ojibwe, are a First Nations band government in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, A ...

, and Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which deri ...

traditions all in close contact.

In the 1840s, Toronto Anglican priest John Black was sent to preach to the settlement, but "his lack of the Gaelic was at first a grievous disappointment" to parishioners. With continuing immigration the population of Scots colonists grew to more than 300, but by the 1860s the French–Métis outnumbered the Scots, and tensions between the two groups would prove a major factor in the ensuing Red River Rebellion

The Red River Rebellion (french: Rébellion de la rivière Rouge), also known as the Red River Resistance, Red River uprising, or First Riel Rebellion, was the sequence of events that led up to the 1869 establishment of a provisional government b ...

.

The continuing association between the Selkirk colonists and surrounding First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

** First Nat ...

groups evolved into a unique contact language

Language contact occurs when speakers of two or more languages or varieties interact and influence each other. The study of language contact is called contact linguistics. When speakers of different languages interact closely, it is typical for th ...

. Used primarily by the Anglo– and Scots–Métis traders, the " Red River Dialect" or ''Bungi'' was a mixture of Gaelic and English with many terms borrowed from the local native languages. Whether the dialect was a trade pidgin

A pidgin , or pidgin language, is a grammatically simplified means of communication that develops between two or more groups of people that do not have a language in common: typically, its vocabulary and grammar are limited and often drawn from s ...

or a fully developed mixed language

A mixed language is a language that arises among a bilingual group combining aspects of two or more languages but not clearly deriving primarily from any single language. It differs from a creole or pidgin language in that, whereas creoles/pidgi ...

is unknown. Today the Scots–Métis have largely been absorbed by the more dominant French–Métis culture, and the Bungi dialect is most likely extinct.

Status in the 19th- and early 20th-century

James Gillanders of Highfield Cottage nearDingwall

Dingwall ( sco, Dingwal, gd, Inbhir Pheofharain ) is a town and a royal burgh in the Highland council area of Scotland. It has a population of 5,491. It was an east-coast harbour that now lies inland. Dingwall Castle was once the biggest cas ...

, was the Factor

Factor, a Latin word meaning "who/which acts", may refer to:

Commerce

* Factor (agent), a person who acts for, notably a mercantile and colonial agent

* Factor (Scotland), a person or firm managing a Scottish estate

* Factors of production, ...

for the estate of Major Charles Robertson of Kincardine Kincardine may refer to:

Places Scotland

*Kincardine, Fife, a town on the River Forth, Scotland

**Kincardine Bridge, a bridge which spans the Firth of Forth

*Kincardineshire, a historic county

**Kincardine, Aberdeenshire, now abandoned

**Kincardi ...

and, as his employer was then serving with the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

in Australia, Gillanders was the person most responsible for the mass evictions staged at Glencalvie, Ross-shire

Ross-shire (; gd, Siorrachd Rois) is a historic county in the Scottish Highlands. The county borders Sutherland to the north and Inverness-shire to the south, as well as having a complex border with Cromartyshire – a county consisting of ...

in 1845. A Gaelic-language poem denouncing Gillanders for the brutality of the evictions was later submitted anonymously to Pàdraig MacNeacail, the editor of the column in Canadian Gaelic in which the poem was later published in the Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

newspaper ''The Casket''. The poem, which is believed to draw upon eyewitness accounts, is believed to be the only Gaelic-language source relating to the evictions in Glencalvie.

By 1850, Gaelic was the third most-common mother tongue

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tong ...

in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

after English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national id ...

and French (when excluding Indigenous languages), and is believed to have been spoken by more than 200,000 British North Americans at that time. A large population who spoke the related Irish immigrated to Scots Gaelic communities and to Irish settlements in Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

.

In Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18 ...

and Glengarry there were large areas of Gaelic unilingualism, and communities of Gaelic-speakers had established themselves in northeastern Nova Scotia (around Pictou and Antigonish

, settlement_type = Town

, image_skyline = File:St Ninian's Cathedral Antigonish Spring.jpg

, image_caption = St. Ninian's Cathedral

, image_flag = Flag of Antigonish.pn ...

); in Glengarry, Stormont, Grey, and Bruce Counties in Ontario; in the Codroy Valley

The Codroy Valley is a valley in the southwestern part of the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Codroy Valley is a glacial valley formed in the Anguille Mountains, a sub-range of the Long Range Mou ...

of Newfoundland; in Winnipeg, Manitoba

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

; and Eastern Quebec

Image:Regions administratives du Quebec.png, 350px, The seventeen administrative regions of Quebec.

poly 213 415 206 223 305 215 304 232 246 230 255 266 251 283 263 289 280 302 291 307 307 315 308 294 318 301 333 299 429 281 432 292 403 311 388 ...

.

In 1890, Thomas Robert McInnes

Thomas Robert McInnes or (Gaelic) Tòmas Raibeart Mac Aonghais (November 5, 1840 – March 15, 1904) was a Canadian physician, Member of Parliament, Senator, and the sixth Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia.

He was the father of the ...

, an independent Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

from British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include ...

(born Lake Ainslie, Cape Breton Island) tabled a bill entitled "An Act to Provide for the Use of Gaelic in Official Proceedings." He cited the ten Scottish and eight Irish senators who spoke Gaelic, and 32 members of the House of Commons of Canada who spoke either Scottish Gaelic or Irish. The bill was defeated 42–7.

Despite the widespread disregard by government on Gaelic issues, records exist of at least one criminal trial conducted entirely in Gaelic, .

From the mid-19th century to the early 1930s, several Gaelic-language newspapers were published in Canada, although the greatest concentration of such papers was in Cape Breton. From 1840 to 1841, () was published in Kingston, Ontario, and in 1851, launched the monthly () in Antigonish, Nova Scotia

, settlement_type = Town

, image_skyline = File:St Ninian's Cathedral Antigonish Spring.jpg

, image_caption = St. Ninian's Cathedral

, image_flag = Flag of Antigonish.pn ...

, which lasted a year before being replaced by the English-language '' Antigonish Casket'', which initially occasional Gaelic-language material. On Cape Breton, several Gaelic-language newspapers were published in Sydney. The longest-lasting was (), published by from 1892 to 1904. began as a weekly, but reduced its frequency to biweekly over time. Later, during the 1920s, several new Scottish Gaelic-language newspapers launched, including the (), which included Gaelic-language lessons; the United Church

A united church, also called a uniting church, is a church formed from the merger or other form of church union of two or more different Protestant Christian denominations.

Historically, unions of Protestant churches were enforced by the state ...

-affiliated (); and MacKinnon's later endeavor, ().

In 1917, Rev. Murdoch Lamont (1865-1927), a Gaelic-speaking Presbyterian minister

Presbyterian (or presbyteral) polity is a method of church governance ("ecclesiastical polity") typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session or ...

from Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitari ...

, Queen's County, Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

, published a small, vanity press

A vanity press or vanity publisher, sometimes also subsidy publisher, is a publishing house where anyone can pay to have a book published.. The term "vanity press" is often used pejoratively, implying that an author who uses such a service is pub ...

booklet titled, ''An Cuimhneachain: Òrain Céilidh Gàidheal Cheap Breatuinn agus Eilean-an-Phrionnsa'' ("The Remembrance: Céilidh Songs of the Cape Breton and Prince Edward Island Gaels") in Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolitan Boston as one of Boston's immediate southern suburbs. Its population in 2020 was 101,636, making ...

. Due to Rev. Lamont's pamphlet, the most complete versions survive of the oral poetry

Oral poetry is a form of poetry that is composed and transmitted without the aid of writing. The complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain.

Background

Oral poetry is ...

composed in Gaelic upon Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

.

Reasons for decline

Despite the long history of Gaels and their language and culture in Canada, the Gaelic speech population started to decline after 1850. This drop was a result ofprejudice

Prejudice can be an affect (psychology), affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived group membership. The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavourable) evaluation or classification (disambiguation), classi ...

(both from outside, and from within the Gaelic community itself), aggressive dissuasion in school and government, and the perceived prestige of English.

Gaelic has faced widespread prejudice in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

for generations, and those feelings were easily transposed to British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

.

The fact that Gaelic had not received official status in its homeland made it easier for Canadian legislators to disregard the concerns of domestic speakers. Legislators questioned why "privileges should be asked for Highland Scotchmen in he Canadian Parliament

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

that are not asked for in their own country". Politicians who themselves spoke the language held opinions that would today be considered misinformed; Lunenburg Senator Henry Kaulback, in response to Thomas Robert McInnes

Thomas Robert McInnes or (Gaelic) Tòmas Raibeart Mac Aonghais (November 5, 1840 – March 15, 1904) was a Canadian physician, Member of Parliament, Senator, and the sixth Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia.

He was the father of the ...

's Gaelic bill, described the language as only "well suited to poetry and fairy tales". The belief that certain languages had inherent strengths and weaknesses was typical in the 19th century, but has been rejected by modern linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Lingu ...

.

Around 1880, from The North Shore, wrote "" (, also known in English as "The Yankee Girl"), a humorous song recounting the growing phenomenon of Gaels shunning their mother-tongue

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tongu ...

.

With the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the Canadian government attempted to prevent the use of Gaelic on public telecommunications systems. The government believed Gaelic was used by subversives affiliated with Ireland, a neutral country perceived to be tolerant of the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

. In Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton where the Gaelic language was strongest, it was actively discouraged in schools with corporal punishment. Children were beaten with the ('hanging stick') if caught speaking Gaelic.

Job opportunities for unilingual Gaels were few and restricted to the dwindling Gaelic-communities, compelling most into the mines or the fishery

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place (a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, ...

. Many saw English fluency as the key to success, and for the first time in Canadian history Gaelic-speaking parents were teaching their children to speak English en masse. The sudden stop of Gaelic language acquisition

Language acquisition is the process by which humans acquire the capacity to perceive and comprehend language (in other words, gain the ability to be aware of language and to understand it), as well as to produce and use words and sentences to ...

, caused by shame and prejudice, was the immediate cause of the drastic decline in Gaelic fluency in the 20th century.

According to Antigonish County

, nickname =

, settlement_type = County

, motto =

, image_skyline = Antigonish Harbour Panorama2.jpg

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, flag_size ...

Gaelic poet and politician Lewis MacKinnon, "We are just like the native peoples here, our culture is indigenous to this region. We too have suffered injustices, we too have been excluded, we too have been forgotten and ridiculed for something that is simply part of who and what we are. It's part of our human expression and that story needs to be told."Keeping Canada's Unique Gaelic Culture AliveBBC News 21 October 2010. Ultimately the population dropped from a peak of 200,000 in 1850, to 80,000 in 1900, to 30,000 in 1930 and 500–1,000 today. There are no longer entire communities of Canadian Gaelic-speakers, although traces of the language and pockets of speakers are relatively commonplace on Cape Breton, and especially in traditional strongholds like

Christmas Island

Christmas Island, officially the Territory of Christmas Island, is an Australian external territory comprising the island of the same name. It is located in the Indian Ocean, around south of Java and Sumatra and around north-west of the ...

, The North Shore, and Baddeck

Baddeck () is a village in northeastern Nova Scotia, Canada. It is situated in the centre of Cape Breton, approximately 6 km east of where the Baddeck River empties into Bras d'Or Lake.

Local governance is provided by the rural municipalit ...

.

Contemporary language, culture, and arts initiatives

A. W. R. MacKenzie founded the Nova Scotia Gaelic College at St Ann's in 1939.

A. W. R. MacKenzie founded the Nova Scotia Gaelic College at St Ann's in 1939. St Francis Xavier University

St. Francis Xavier University is a public undergraduate liberal arts university located in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is a member of the Maple League, a group of primarily undergraduate universities in Eastern Canada.

History

St. Franc ...

in Antigonish

, settlement_type = Town

, image_skyline = File:St Ninian's Cathedral Antigonish Spring.jpg

, image_caption = St. Ninian's Cathedral

, image_flag = Flag of Antigonish.pn ...

has a Celtic Studies department with Gaelic-speaking faculty members, and is the only such university department outside Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

to offer four full years of Scottish Gaelic instruction.

of Antigonish published the monthly Gaelic magazine () around 1851. The world's longest-running Gaelic periodical, (), was printed by Jonathon G. MacKinnon for 11 years between 1892 and 1904, in Sydney. However, MacKinnon's mockery of complaints over ''Mac-Tallas regular misprints and his tendency to financially guilt trip

A guilt trip is a feeling of guilt or responsibility, especially an unjustified one induced by someone else.

Overview

Creating a guilt trip in another person may be considered to be manipulation in the form of punishment for a perceived trans ...

his subscribers, ultimately led local Gaelic poet Alasdair a' Ridse MacDhòmhnaill

Alasdair is a Scottish Gaelic given name. The name is a Gaelic form of '' Alexander'' which has long been a popular name in Scotland. The personal name ''Alasdair'' is often Anglicised as '' Alistair'', ''Alastair'', and ''Alaster''.''A Dictionary ...

to lampoon ''Mac-Talla'' and its editor in two separate works of satirical poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in ...

: ('A Song of Revile to ''Mac-Talla''black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

speakers of Goidelic languages

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historical ...

in Canada, were born in Cape Breton and in adulthood became friends with Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much o ...

, who in 1896 wrote ''Captains Courageous

''Captains Courageous: A Story of the Grand Banks'' is an 1897 novel by Rudyard Kipling that follows the adventures of fifteen-year-old Harvey Cheyne Jr., the spoiled son of a railroad tycoon, after he is saved from drowning by a Portuguese f ...

'', which featured an isolated Gaelic-speaking African-Canadian

Black Canadians (also known as Caribbean-Canadians or Afro-Canadians) are people of full or partial sub-Saharan African descent who are citizens or permanent residents of Canada. The majority of Black Canadians are of Caribbean origin, though ...

cook from Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18 ...

.

Many English-speaking writers and artists of Scottish-Canadian

Scottish Canadians are people of Scottish descent or heritage living in Canada. As the third-largest ethnic group in Canada and amongst the first Europeans to settle in the country, Scottish people have made a large impact on Canadian culture sin ...

ancestry have featured Canadian Gaelic in their works, among them Alistair MacLeod

Alistair MacLeod, (July 20, 1936 – April 20, 2014) was a Canadian novelist, short story writer and academic. His powerful and moving stories vividly evoke the beauty of Cape Breton Island's rugged landscape and the resilient character of m ...

('' No Great Mischief''), Ann-Marie MacDonald

Ann-Marie MacDonald (born October 29, 1958) is a Canadian playwright, author, actress, and broadcast host who lives in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. MacDonald is the daughter of a member of Canada's military; she was born at an air force base near ...

('' Fall on Your Knees''), and D.R. MacDonald (''Cape Breton Road''). Gaelic singer Mary Jane Lamond has released several albums in the language, including the 1997 hit ('Jenny Dang the Weaver'). Cape Breton fiddling

Cape Breton fiddling is a regional violin style which falls within the Celtic music idiom. Cape Breton Island's fiddle music was brought to North America by Scottish immigrants during the Highland Clearances. These Scottish immigrants were prim ...

is a unique tradition of Gaelic and Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

n styles, known in fiddling circles worldwide.

Several Canadian schools use the "Gael" as a mascot, the most prominent being Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario

Kingston is a city in Ontario, Canada. It is located on the north-eastern end of Lake Ontario, at the beginning of the St. Lawrence River and at the mouth of the Cataraqui River (south end of the Rideau Canal). The city is midway between Toront ...

. The school cheer of Queen's University is ('The Queen's College and Queen forever!'), and is traditionally sung after scoring a touchdown in football matches. The university's team is nicknamed the Golden Gaels.

The Gaelic character of Nova Scotia has influenced that province's industry and traditions. Glen Breton Rare

Glenora Distillers is a distiller based in Glenville, Inverness County, Nova Scotia, Glenville, Nova Scotia, Canada, on Cape Breton Island. Their most prominent product is Glen Breton Rare whisky, made in the Scottish-style in that it is a Single ...

, produced in Cape Breton, is one of the very few single malt whiskies

Single malt whisky is malt whisky from a single Distillation, distillery.

Single malts are typically associated with single malt Scotch, though they are also produced in various other countries. Under the United Kingdom's Scotch Whisky Regul ...

to be made outside Scotland.

Gaelic settlers in Nova Scotia adapted the popular Highland winter sport

Winter sports or winter activities are competitive sports or non-competitive recreational activities which are played on snow or ice. Most are variations of skiing, ice skating and sledding. Traditionally, such games were only played in cold ...

of Highland winter sport

Winter sports or winter activities are competitive sports or non-competitive recreational activities which are played on snow or ice. Most are variations of skiing, ice skating and sledding. Traditionally, such games were only played in cold ...

of shinty

Shinty ( gd, camanachd, iomain) is a team game played with sticks and a ball. Shinty is now played mainly in the Scottish Highlands and amongst Highland migrants to the big cities of Scotland, but it was formerly more widespread in Scotland, and ...

( gd, camanachd, iomain), which was traditionally played by the Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic lan ...

upon St. Andrew's Day, Christmas Day

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

, New Year's Day

New Year's Day is a festival observed in most of the world on 1 January, the first day of the year in the modern Gregorian calendar. 1 January is also New Year's Day on the Julian calendar, but this is not the same day as the Gregorian one. Wh ...

, Handsel Monday

In Scotland, Handsel Monday or Hansel Monday is the first Monday of the year. Traditionally, gifts ( sco, Hansels) were given at this time.

Among the rural population of Scotland, '' Auld Hansel Monday'', is traditionally celebrated on the firs ...

, and Candlemas

Candlemas (also spelled Candlemass), also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Feast of the Holy Encounter, is a Christian holiday commemorating the presenta ...

, to the much colder Canadian winter climate by playing on frozen lakes while wearing ice skates

Ice skates are metal blades attached underfoot and used to propel the bearer across a sheet of ice while ice skating.

The first ice skates were made from leg bones of horse, ox or deer, and were attached to feet with leather straps. These skate ...

. This led to the creation of the modern sport known as ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an Ice rink, ice skating rink with Ice hockey rink, lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two o ...

.

According to Margie Beaton, who emigrated from Scotland to Nova Scotia to teach the Gaelic language there in 1976, "In teaching the language here I find that they already have the , the sound of the Gaelic even in their English. It's part of who they are, you can't just throw that away. It's in you."

While performing in 2000 at the annual Cèilidh at Christmas Island

Christmas Island, officially the Territory of Christmas Island, is an Australian external territory comprising the island of the same name. It is located in the Indian Ocean, around south of Java and Sumatra and around north-west of the ...

, Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18 ...

, Barra

Barra (; gd, Barraigh or ; sco, Barra) is an island in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, and the second southernmost inhabited island there, after the adjacent island of Vatersay to which it is connected by a short causeway. The island is nam ...

native and legendary Gaelic singer Flora MacNeil spread her arms wide and cried, "You are my people!" The hundreds of Canadian-born Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic lan ...

in the audience immediately erupted into loud cheers.

According to Natasha Sumner, the current literary and cultural revival of the Gaelic language in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

was largely instigated by Kenneth E. Nilsen

Kenneth is an English given name and surname. The name is an Anglicised form of two entirely different Gaelic personal names: ''Cainnech'' and '' Cináed''. The modern Gaelic form of ''Cainnech'' is ''Coinneach''; the name was derived from a byna ...

(1941-2012), an American linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Lingui ...

with a specialty in Celtic languages

The Celtic languages (usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edwar ...

. During his employment as Professor of Gaelic Studies at St. Francis Xavier University

St. Francis Xavier University is a public undergraduate liberal arts university located in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is a member of the Maple League, a group of primarily undergraduate universities in Eastern Canada.

History

St. Fra ...

in Antigonish

, settlement_type = Town

, image_skyline = File:St Ninian's Cathedral Antigonish Spring.jpg

, image_caption = St. Ninian's Cathedral

, image_flag = Flag of Antigonish.pn ...

, Nilsen was known for his contagious enthusiasm for both teaching and recording the distinctive Nova Scotia dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that ...

of the Gaelic-language, its folklore, and its oral literature

Oral literature, orature or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung as opposed to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used va ...

. Several important leaders in the recent Canadian Gaelic revival, including the poet Lewis MacKinnon

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

(), have credited Nilsen with sparking their interest in learning the Gaelic language and in actively fighting for its survival.

During his time as Professor of Gaelic Studies, Nilsen would take his students every year to visit the grave of the Tiree

Tiree (; gd, Tiriodh, ) is the most westerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The low-lying island, southwest of Coll, has an area of and a population of around 650.

The land is highly fertile, and crofting, alongside tourism, and ...

-born Bard Iain mac Ailein (John MacLean) (1787–1848) at Glenbard, Antigonish County, Nova Scotia

, nickname =

, settlement_type = County

, motto =

, image_skyline = Antigonish Harbour Panorama2.jpg

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, flag_size ...

. Following Prof. Nilsen's death in 2012, MacKinnon composed a Gaelic-language poetic lament for his former teacher, entitled .

In a 2010 interview Scottish-born Gaelic teacher Margie Beaton said that in Scotland, "The motto they have for Nova Scotia is , which translates as 'but for the ocean', meaning 'but for the ocean we'd actually be together. There's only an ocean separating us. We're like another island off the coast of Scotland but we have an ocean separating us instead of a strait or a channel."

The first Gaelic language film to be made in North America, ''The Wake of Calum MacLeod

''The Wake of Calum MacLeod'' ( gd, Faire Chaluim Mhic Leòid) is a Canadian drama short film, directed by Marc Almon and released in 2006.Royal National Mòd

The Royal National Mòd ( gd, Am Mòd Nàiseanta Rìoghail) is an Eisteddfod-inspired international Celtic festival focusing upon Scottish Gaelic literature, traditional music, and culture which is held annually in Scotland. It is the largest ...

, held at Stornoway

Stornoway (; gd, Steòrnabhagh; sco, Stornowa) is the main town of the Western Isles and the capital of Lewis and Harris in Scotland.

The town's population is around 6,953, making it by far the largest town in the Outer Hebrides, as well ...

on the Isle of Lewis

The Isle of Lewis ( gd, Eilean Leòdhais) or simply Lewis ( gd, Leòdhas, ) is the northern part of Lewis and Harris, the largest island of the Western Isles or Outer Hebrides archipelago in Scotland. The two parts are frequently referred to as ...

, crowned Lewis MacKinnon

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

(), a poet in Canadian Gaelic from Antigonish County

, nickname =

, settlement_type = County

, motto =

, image_skyline = Antigonish Harbour Panorama2.jpg

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, flag_size ...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

, as the winning Bard. It was the first time in the 120-year history of the Mòd that a writer of Gaelic poetry from the Scottish diaspora

The Scottish diaspora consists of Scottish people who emigrated from Scotland and their descendants. The diaspora is concentrated in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, England, New Zealand, Ireland and to a lesser extent ...

had won the Bardic Crown.

The Gaelic scholar Michael Newton made a half-hour documentary, ''Singing Against the Silence'' (2012), about the revival of Nova Scotia Gaelic in that language; he has also published an anthology of Canadian Gaelic literature, (2015).

Lewis MacKinnon's 2017 Gaelic poetry collection ("Seasons for Seeking"), includes both his original poetry and his literary translations of the Persian poetry

Persian literature ( fa, ادبیات فارسی, Adabiyâte fârsi, ) comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources h ...

of Sufi mystic Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

, all of which are themed around the seasons of the year.

Outlook and development

Efforts to address the decline specifically of Gaelic language in Nova Scotia began in the late 1980s. Two conferences on the status of Gaelic language and culture held on Cape Breton Island set the stage. Starting in the late 1990s, the Nova Scotia government began studying ways it might enhance Gaelic in the province. In December 2006 the Office of Gaelic Affairs was established. InPrince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

, the Colonel Gray High School now offers both an introductory and an advanced course in Gaelic; both language and history are taught in these classes. This is the first recorded time that Gaelic has ever been taught as an official course on Prince Edward Island.

Maxville Public School in Maxville, Glengarry

The Glengarry bonnet is a traditional Scots cap made of thick-milled woollen material, decorated with a toorie on top, frequently a rosette cockade on the left side, and ribbons hanging behind. It is normally worn as part of Scottish military o ...

, Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

, Canada offers Scottish Gaelic lessons weekly. The last "fluent" Gaelic-speaker in Ontario, descended from the original settlers of Glengarry County, died in 2001.

The province of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include ...

is host to the (The Gaelic Society of Vancouver), the Vancouver Gaelic Choir, the Victoria Gaelic Choir, as well as the annual Gaelic festival '' Vancouver''. The city of Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. Th ...

's Scottish Cultural Centre also holds seasonal Scottish Gaelic evening classes.

Government

A Gaelic economic impact study completed by the Nova Scotia government in 2002 estimates that Gaelic generates over $23.5 million annually, with nearly 380,000 people attending approximately 2,070 Gaelic events annually. This study inspired a subsequent report, the Gaelic Preservation Strategy, which polled the community's desire to preserve Gaelic while seeking consensus on adequate reparative measures. These two documents are watersheds in the timeline of Canadian Gaelic, representing the first concrete steps taken by a provincial government to recognize the language's decline and engage local speakers in reversing this trend. The documents recommendcommunity development

The United Nations defines community development as "a process where community members come together to take collective action and generate solutions to common problems." It is a broad concept, applied to the practices of civic leaders, activists ...

, strengthening education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. ...

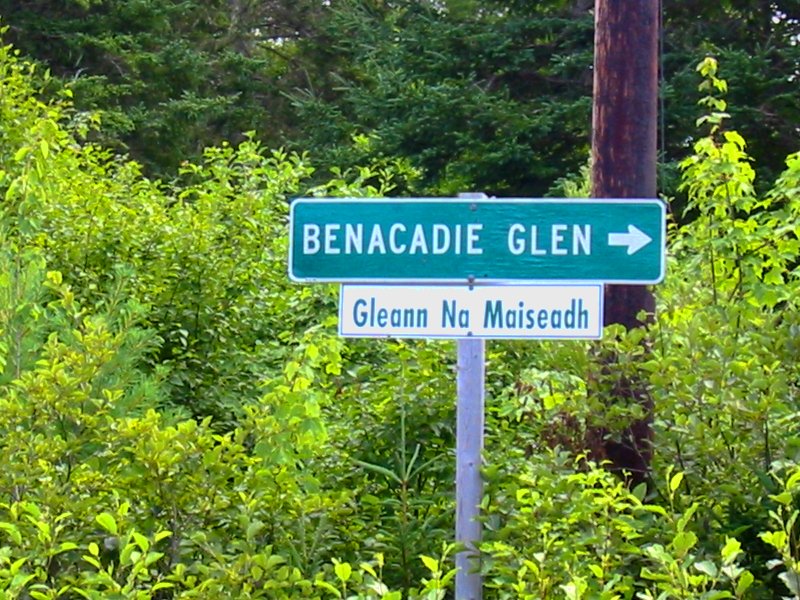

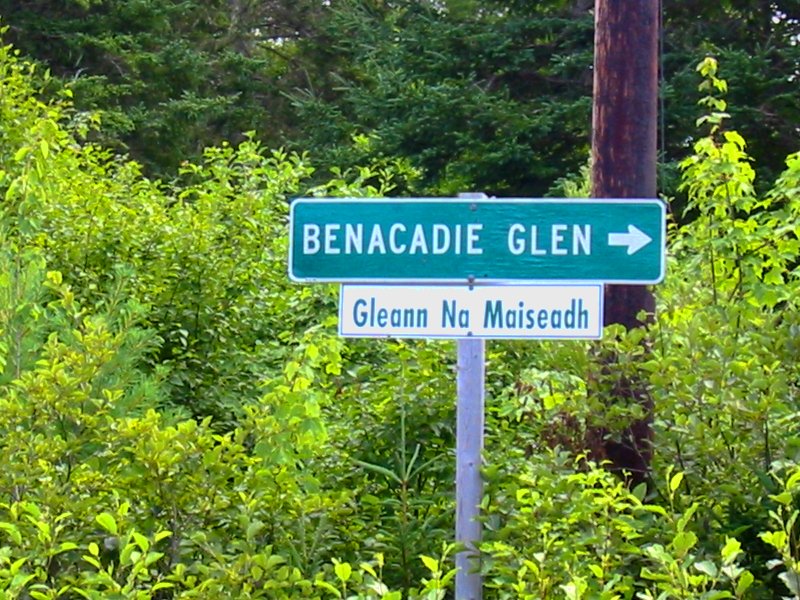

, legislating road signs