Motu Ihupuku on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

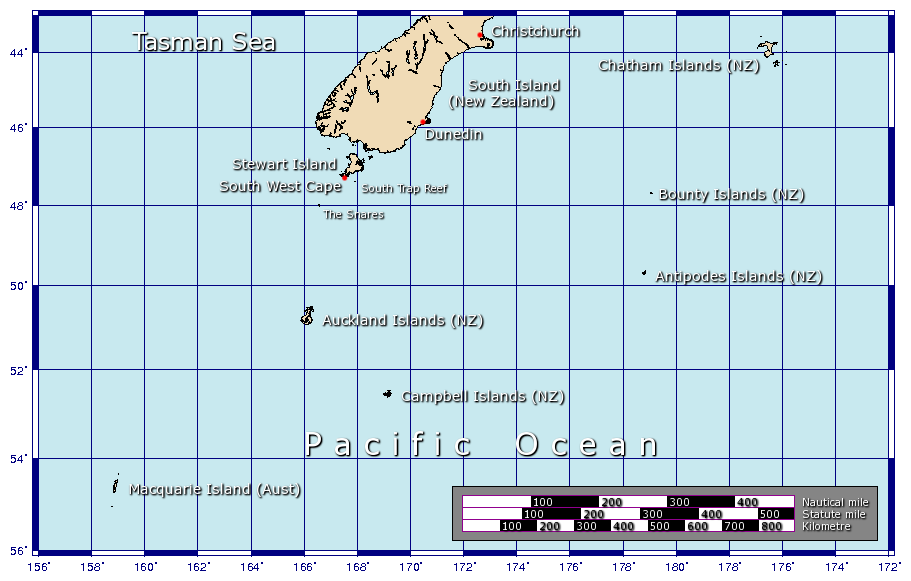

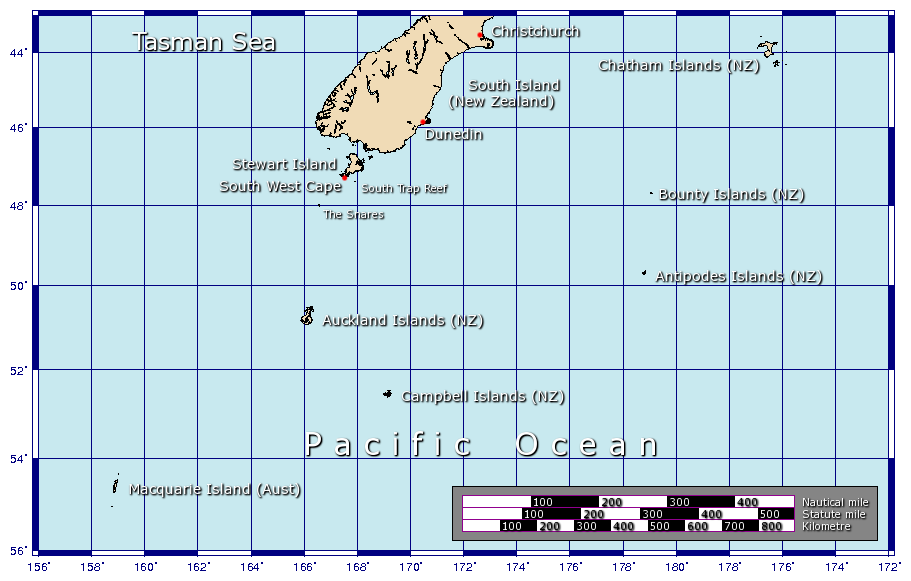

Campbell Island / Motu Ihupuku is an

Campbell Island was discovered in 1810 by Captain

Campbell Island was discovered in 1810 by Captain

After

After

/ref>

File:Elephantseal.jpg, Vagrant adolescent male

Topographic map

Campbell Island, NZMS 272/3, Edition 1, 1986.

* ttps://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/science/plants-animals-fungi/fungi/describing-the-fungi-of-new-zealand/subantarctic-fungi/subantarctic-islands/campbell-island Landcare Research - Campbell Island

Campbell Island Bicentennial Expedition

Campbell Island Freshwater Invertebrate Identification Keys

{{coord, 52, 32.4, S, 169, 8.7, E, region:NZ_type:isle, display=title Islands of the Campbell Islands New Zealand subantarctic islands Seabird colonies Island restoration Important Bird Areas of the Campbell Islands Subantarctic islands Seal hunting Whaling stations in New Zealand Volcanoes of the New Zealand outlying islands Miocene shield volcanoes Penguin colonies

uninhabited

The list of uninhabited regions includes a number of places around the globe. The list changes year over year as human beings migrate into formerly uninhabited regions, or migrate out of formerly inhabited regions.

List

As a group, the list of ...

subantarctic

The sub-Antarctic zone is a region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46° and 60° south of the Equator. The subantarctic region includes many islands ...

island of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, and the main island of the Campbell Island group

The Campbell Islands (or Campbell Island Group) are a group of subantarctic islands, belonging to New Zealand. They lie about 600 km south of Stewart Island. The islands have a total area of , consisting of one big island, Campbell Isla ...

. It covers of the group's , and is surrounded by numerous stacks, rocks and islet

An islet is a very small, often unnamed island. Most definitions are not precise, but some suggest that an islet has little or no vegetation and cannot support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/or hard coral; may be permanen ...

s like Dent Island, Folly Island

Folly Island is a barrier island in the Atlantic Ocean near Charleston, South Carolina. It is one of the Sea Islands and is within the boundaries of Charleston County, South Carolina. During the American Civil War, the island served as a majo ...

(or Folly Islands), Isle de Jeanette-Marie, and Jacquemart Island

Jacquemart Island, one of the islets surrounding Campbell Island in New Zealand, lies south of Campbell Island and is the southernmost island of New Zealand.

The name commemorates Captain J. Jacquemart, of the vessel FRWS ''Vire'', that supp ...

, the latter being the southernmost extremity of New Zealand. The island is mountainous, rising to over in the south. A long fiord

In physical geography, a fjord or fiord () is a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Alaska, Antarctica, British Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Förden and East Jutland Fjorde, Germany, Gr ...

, Perseverance Harbour

Perseverance Harbour, also known as South harbour, is a large indentation in the coast of Campbell Island, one of New Zealand's subantarctic outlying islands. The harbour is a long lateral fissure which reaches the ocean in the island's sout ...

, nearly bisects it, opening out to sea on the east coast.

The island is listed with the New Zealand Outlying Islands

The New Zealand outlying islands are nine offshore island groups that are part of New Zealand, with all but Solander Islands lying beyond the 12nm limit of the mainland's territorial waters. Although considered an integral parts of New Zealand ...

. The island is an immediate part of New Zealand, but not part of any region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics ( physical geography), human impact characteristics ( human geography), and the interaction of humanity an ...

or district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municipa ...

, but instead ''Area Outside Territorial Authority'', like all other outlying islands, other than the Solander Islands

The Solander Islands / Hautere are three uninhabited volcanic islets toward the western end of the Foveaux Strait just beyond New Zealand's South Island. The Māori name ''Hautere'' translates into English as "flying wind". The islands lie so ...

. It is the closest piece of land to the antipodal point

In mathematics, antipodal points of a sphere are those diametrically opposite to each other (the specific qualities of such a definition are that a line drawn from the one to the other passes through the center of the sphere so forms a true d ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, meaning that the furthest away city is Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

, Ireland.

Campbell Island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

.

History

Campbell Island was discovered in 1810 by Captain

Campbell Island was discovered in 1810 by Captain Frederick Hasselborough

Frederick Hasselborough (drowned 4 November 1810, in Perseverance Harbour), whose surname is also spelled Hasselburgh and Hasselburg, was an Australian sealer from Sydney who discovered Campbell (4 January 1810) and Macquarie Island

Macqua ...

of the sealing brig ''Perseverance'', which was owned by shipowner Robert Campbell's Sydney-based company Campbell & Co. (whence the island's name). Captain Hasselborough drowned on 4 November 1810 in Perseverance Harbour

Perseverance Harbour, also known as South harbour, is a large indentation in the coast of Campbell Island, one of New Zealand's subantarctic outlying islands. The harbour is a long lateral fissure which reaches the ocean in the island's sout ...

on the south of the island, along with a young woman and a boy.

The island became a seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to imp ...

hunting base, and the seal population was almost totally eradicated. The first sealing boom was over by the mid-1810s. The second was a brief revival in the 1820s. The sealing era lasted from 1810 till 1912 during which time 49 vessels are recorded visiting for sealing purposes, one of which was lost off the coast.

The whaling boom extended here in the 1830s and '40s. In 1874, the island was visited by a French scientific expedition intending to view the transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tr ...

. Much of the island's topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sc ...

is named after aspects of, or people connected with, the expedition.

In 1840 Campbell Island was the last landfall before the Ross expedition explored the Antarctic.

In 1883 the American schooner ''Sarah W. Hunt'', a whaler, was near Campbell Island. Twelve men in two small whaleboats headed for the island in terrible weather looking for seals. One of the boats disappeared, and the other boat with six men aboard managed to make it ashore. Sanford Miner, the captain of the ''Sarah W. Hunt'', assumed all the whalers were lost, and sailed away to Lyttelton, New Zealand. Fortunately for the stranded whalers, a seal protection boat, the ''Kekeno'', happened to arrive at the island, and rescued the castaways. The captain's behaviour caused an international scandal.

In the late 19th century, the island became a pastoral lease. Sheep farming

Sheep farming or sheep husbandry is the raising and breeding of domestic sheep. It is a branch of animal husbandry. Sheep are raised principally for their meat (lamb and mutton), milk (sheep's milk), and fiber (wool). They also yield sheepskin an ...

was undertaken from 1896 until the lease, along with the sheep and a small herd of cattle, was abandoned in 1931 because of the Great Depression.

In 1907, a group of scientists spent eight days on the island group surveying. The 1907 Sub-Antarctic Islands Scientific Expedition

The Sub-Antarctic Islands Scientific Expedition of 1907 was organised by the Philosophical Institute of Canterbury. The main aim of the expedition was to extend the magnetic survey of New Zealand by investigating Campbell Island and the Aucklan ...

conducted a magnetic survey and also took botanical, zoological and geological specimens.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, a coastwatching station was operative at Tucker Cove at the north shore of Perseverance Harbour as part of the Cape Expedition

The Cape Expedition was the deliberately misleading name given to a secret five-year wartime program of establishing coastwatching stations on New Zealand’s more distant uninhabited subantarctic islands. The decision to do so was made by t ...

program.

Following the passage of the Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998, the name of the island was officially altered to Campbell Island / Motu Ihupuku.

An amateur radio DXpedition

A DX-pedition is an expedition to what is considered an exotic place by amateur radio operators and DX listeners, typically because of its remoteness, access restrictions, or simply because there are very few radio amateurs active from that pl ...

organised by the Hellenic Amateur Radio Association of Australia visited Campbell Island during November–December 2012. The team consisted of ten amateur radio operators from around the world, a NZ Department of Conservation Officer and the ship's crew of six including the captain on the sailing vessel "Evohe". The ZL9HR DXpedition team made 42,922 on-air contacts during an eight-day operating period.

Weather station

After

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the coast watching facilities at Tucker Cove were used as a meteorological station until the summer of 1958, when a new base was established at Beeman Cove, a few hundred metres further east. The new location provided improved exposure for the weather instruments, particularly wind recordings, and more modern accommodation for up to 12 full-time staff.

The new meteorological station (WMO ID 93944) at Beeman Cove was operated by the New Zealand Meteorological Service

Meteorological Service of New Zealand Limited (MetService - Te Ratonga Tirorangi) is the national meteorological service of New Zealand. MetService was established as a state-owned enterprise in 1992. It employs about 300 staff, and its headqua ...

with ten full-time staff. Each team undertook 12-month expeditions to the island to undertake three hourly weather reports and twice daily radiosonde

A radiosonde is a battery-powered telemetry instrument carried into the atmosphere usually by a weather balloon that measures various atmospheric parameters and transmits them by radio to a ground receiver. Modern radiosondes measure or calcula ...

flights using hydrogen filled balloons. Weather reports were radioed back to New Zealand using HF radio to ZLW Wellington Radio. In addition to its primary purpose as a meteorological station, staff at the station also made measurements of the earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic ...

, the ionosphere, and aurora australis, and undertook Albatross banding and whale counts of primarily Southern Right Whales

The southern right whale (''Eubalaena australis'') is a baleen whale, one of three species classified as right whales belonging to the genus ''Eubalaena''. Southern right whales inhabit oceans south of the Equator, between the latitudes of 20° ...

for the New Zealand Wildlife Service

The New Zealand Wildlife Service was a division of the Department of Internal Affairs responsible for managing wildlife in New Zealand. It was established in 1945 (as the ''Wildlife Branch'') in order to unify wildlife administration and operation ...

.

In April 1992, staff of the weather station were snorkelling at Northwest Bay when one of them, Mike Fraser, was attacked by a great white shark

The great white shark (''Carcharodon carcharias''), also known as the white shark, white pointer, or simply great white, is a species of large Lamniformes, mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major ocean ...

some offshore from the beach at Middle Bay. Fraser managed to return to shore with the assistance of one of his team, Jacinda Amey, after suffering severe lacerations to both his arms. The team kept Fraser alive at the bay—some from the main base—while a rescue helicopter from Taupo was called and made an emergency flight to the island to repatriate him to Invercargill

Invercargill ( , mi, Waihōpai is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. The city lies in the heart of the wide expanse of t ...

Hospital. This was the longest ever single-engine helicopter rescue in the world.

Jacinda Amey was awarded the New Zealand Cross—the highest bravery medal for civilians—for assisting the injured team member from the water. The rescue helicopter pilot, John Funnell, was awarded the New Zealand Bravery Medal.

In 1995, station staff were permanently withdrawn when the manual weather observation programme was replaced by an automated weather station, and the upper air soundings ceased. Today periodic visits to the island are undertaken by Meteorological Service staff to maintain the weather station on Royal New Zealand Navy

The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN; mi, Te Taua Moana o Aotearoa, , Sea Warriors of New Zealand) is the maritime arm of the New Zealand Defence Force. The fleet currently consists of nine ships. The Navy had its origins in the Naval Defence Act ...

vessels, which also transport conservation staff undertaking field research. Other visitors to the island include occasional summer time eco-tourism cruises.

In May 2018, scientists in New Zealand documented what they believe is the largest wave ever recorded in the Southern Hemisphere to date. The wave was measured by a weather buoy

Weather buoys are instruments which collect weather and ocean data within the world's oceans, as well as aid during emergency response to chemical spills, legal proceedings, and engineering design. Moored buoys have been in use since 1951, wh ...

near the island.

The legend of ''The Lady of the Heather''

''The Lady of the Heather'' is the title of a romantic novel by Will Lawson. The novel is a mixture of facts and fiction elaborating on the incidents surrounding Captain Hasselburg's death on Campbell Island. The story is about a daughter ofBonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie, is a Scottish given name and is sometimes used as a descriptive reference, as in the Scottish folk song, My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean. It comes from the Scots language word "bonnie" (pretty, attractive), or the French bonne (good). That ...

, exiled to Campbell Island after she is suspected of treachery to the Jacobite cause.

Her character was inspired by Elizabeth Farr. Farr was probably what would now be called a "ship girl", but the presence of a European woman at this remote place, and her death, gave rise to ''The Lady of the Heather'' story.

The accident happened when William Tucker was present on the ''Aurora''. Tucker was another unusual character in the sealing era who became the source of a legend and a novel. The remoteness and striking appearance of the sealing grounds, whether on mainland New Zealand or the subantarctic islands, and the sealing era's early place in Australasia's European history, supply the elements for romance and legend which are generally absent in the area's colonial history.

Climate

Campbell Island has a maritimetundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

climate (Köppen ''ET''). The island receives only 647 hours of bright sunshine annually and it can expect less than an hour's sunshine on 215 days (59%) of the year. The peaks of the island are frequently obscured by clouds. It has an annual rainfall of , with rain, mainly light showers or drizzle (although it occasionally snows in the winter), falling on an average of 325 days a year. It is a windy place, with gusts of over occurring on at least 100 days each year. Variations in daily and annual temperatures are small with a mean annual temperature of , rarely rising above . The warmest temperature ever recorded was and the coldest was .

NZ Govt report on eradication of Norway rats/ref>

Flora and fauna

Important Bird Area

Campbell Island is the most important breeding area of thesouthern royal albatross

The southern royal albatross or toroa, (''Diomedea epomophora'') is a large seabird from the albatross family. At an average wingspan of above , it is one of the two largest species of albatross, together with the wandering albatross. Recent stu ...

. The island is part of the Campbell Island group Important Bird Area (IBA), identified as such by BirdLife International because of its significance as a breeding site for several species of seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s as well as the endemic Campbell teal

The Campbell teal or Campbell Island teal (''Anas nesiotis'') is a small, flightless, nocturnal species of dabbling duck of the genus ''Anas'' endemic to the Campbell Island group of New Zealand. It is sometimes considered conspecific with the ...

and Campbell snipe

The Campbell snipe (''Coenocorypha aucklandica perseverance''), also known as the Campbell Island snipe, is a rare subspecies of the Subantarctic snipe, endemic to Campbell Island, a subantarctic island south of New Zealand in the Southern Oce ...

. Campbell Island also hosts numerous penguin species that breed on the island, including the yellow-eyed penguin

The yellow-eyed penguin (''Megadyptes antipodes''), known also as hoiho or tarakaka, is a species of penguin endemic to New Zealand.

Previously thought closely related to the little penguin (''Eudyptula minor''), molecular research has shown it ...

, the rockhopper penguin

The rockhopper penguins are three closely related taxa of crested penguins that have been traditionally treated as a single species and are sometimes split into three species.

Not all experts agree on the classification of these penguins. Some ...

, and the erect-crested penguin. Other albatross species breed on the island as well, such as the wandering albatross

The wandering albatross, snowy albatross, white-winged albatross or goonie (''Diomedea exulans'') is a large seabird from the family Diomedeidae, which has a circumpolar range in the Southern Ocean. It was the last species of albatross to be desc ...

, the light-mantled sooty albatross

The light-mantled albatross (''Phoebetria palpebrata'') also known as the grey-mantled albatross or the light-mantled sooty albatross, is a small albatross in the genus '' Phoebetria'', which it shares with the sooty albatross. The light-mantle ...

, and both the Black-browed mollymawk and the grey-headed mollymawk. Other bird species that breed on the island include the sooty shearwater

The sooty shearwater (''Ardenna grisea'') is a medium-large shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. In New Zealand, it is also known by its Māori name , and as muttonbird, like its relatives the wedge-tailed shearwater (''A. pacificus ...

, the grey petrel, the white-chinned petrel

The white-chinned petrel (''Procellaria aequinoctialis'') also known as the Cape hen and shoemaker, is a large shearwater in the family Procellariidae. It ranges around the Southern Ocean as far north as southern Australia, Peru and Namibia, and ...

, the endemic Campbell Island shag

The Campbell shag (''Leucocarbo campbelli''), also known as the Campbell Island shag, is a species of bird in the family Phalacrocoracidae. It is endemic to Campbell Island. Its natural habitats are open seas and rocky shores. It is a medium-s ...

, the grey duck, the southern skua, the southern black-backed gull, the red-billed gull, the Antarctic tern

The Antarctic tern (''Sterna vittata'') is a seabird in the family Laridae. It ranges throughout the southern oceans and is found on small islands around Antarctica as well as on the shores of the mainland. Its diet consists primarily of small fis ...

, the song thrush, the Common blackbird, the Dunnock

The dunnock (''Prunella modularis'') is a small passerine, or perching bird, found throughout temperate Europe and into Asian Russia. Dunnocks have also been successfully introduced into New Zealand. It is by far the most widespread member of th ...

(Hedge sparrow), the New Zealand pipit

The New Zealand pipit (''Anthus novaeseelandiae'') is a fairly small passerine bird of open country in New Zealand and outlying islands. It belongs to the pipit genus ''Anthus'' in the family Motacillidae.

It was formerly lumped together with th ...

, the white-eye

The white-eyes are a family, Zosteropidae, of small passerine birds native to tropical, subtropical and temperate Sub-Saharan Africa, southern and eastern Asia, and Australasia. White-eyes inhabit most tropical islands in the Indian Ocean, the ...

, the lesser redpoll

The lesser redpoll (''Acanthis cabaret'') is a small passerine bird in the finch family, Fringillidae. It is the smallest, brownest, and most streaked of the redpolls. It is sometimes classified as a subspecies of the common redpoll (''Acanthis ...

, the chaffinch

The common chaffinch or simply the chaffinch (''Fringilla coelebs'') is a common and widespread small passerine bird in the finch family. The male is brightly coloured with a blue-grey cap and rust-red underparts. The female is more subdued in ...

, and the starling

Starlings are small to medium-sized passerine birds in the family Sturnidae. The Sturnidae are named for the genus '' Sturnus'', which in turn comes from the Latin word for starling, ''sturnus''. Many Asian species, particularly the larger ones, ...

.

World's most remote tree

Campbell Island is home to what is believed to be the world's most remote tree – a solitary Sitka spruce, more than 100 years old. The nearest tree is over away on theAuckland Islands

The Auckland Islands (Māori: ''Motu Maha'' "Many islands" or ''Maungahuka'' "Snowy mountains") are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying , is surrounded by smaller Adams Islan ...

. The tree is believed to have been introduced by Lord Ranfurly

Uchter John Mark Knox, 5th Earl of Ranfurly (14 August 1856 – 1 October 1933), was a British politician and colonial governor. He was Governor of New Zealand from 1897 to 1904.

Early life

Lord Ranfurly was born into an Ulster-Scots aristocrat ...

between 1901 and 1907. The tree has been proposed as a golden spike signal marker for the start of the anthropocene

The Anthropocene ( ) is a proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems, including, but not limited to, anthropogenic climate change.

, neither the International Commissio ...

epoch.

Conservation

In 1954, the island was gazetted as anature reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

. Feral Campbell Island cattle were eliminated by about 1984 and feral Campbell Island sheep

Campbell Island sheep are a feral breed of domestic sheep formerly found on New Zealand's subantarctic Campbell Island.

History The sheep farmers

The sheep were originally introduced to Campbell Island in the late 1890s, following the inclusion ...

were culled during the 1970s and 1980s, with their eventual extermination in 1992. In 2001, brown rat

The brown rat (''Rattus norvegicus''), also known as the common rat, street rat, sewer rat, wharf rat, Hanover rat, Norway rat, Norwegian rat and Parisian rat, is a widespread species of common rat. One of the largest muroids, it is a brown o ...

s (Norway rats) were eradicated from the island nearly 200 years after their introduction. This was the world's largest rat eradication programme. The island's rat-free status was confirmed in 2003. Since the eradication, vegetation and invertebrates have been recovering, seabirds have been returning and the Campbell teal

The Campbell teal or Campbell Island teal (''Anas nesiotis'') is a small, flightless, nocturnal species of dabbling duck of the genus ''Anas'' endemic to the Campbell Island group of New Zealand. It is sometimes considered conspecific with the ...

, the world's rarest duck, has been reintroduced. An undescribed ''Cyanoramphus

''Cyanoramphus'' is a genus of parakeets native to New Zealand and islands of the southern Pacific Ocean. The New Zealand forms are often referred to as kākāriki. They are small to medium-sized parakeets with long tails and predominantly gree ...

'' parakeet was discovered (in fossil bones) in 2004, along with evidence of a falcon or harrier. Banded dotterel

The double-banded plover (''Charadrius bicinctus''), known as the banded dotterel or pohowera in New Zealand, is a species of bird in the plover family. Two subspecies are recognised: the nominate ''Charadrius bicinctus bicinctus'', which breed ...

(''Charadrius bicinctus'') are also believed to have inhabited the island at one point. Other native landbirds include the New Zealand pipit

The New Zealand pipit (''Anthus novaeseelandiae'') is a fairly small passerine bird of open country in New Zealand and outlying islands. It belongs to the pipit genus ''Anthus'' in the family Motacillidae.

It was formerly lumped together with th ...

and the Campbell snipe

The Campbell snipe (''Coenocorypha aucklandica perseverance''), also known as the Campbell Island snipe, is a rare subspecies of the Subantarctic snipe, endemic to Campbell Island, a subantarctic island south of New Zealand in the Southern Oce ...

, a race of the Subantarctic snipe, ''Coenocorypha aucklandica

The Subantarctic snipe (''Coenocorypha aucklandica'') is a species of snipe endemic to New Zealand's subantarctic islands. The Maori call it "Tutukiwi". The nominate race ''C. a. aucklandica'' ( Auckland snipe) is found on the Auckland Islands ( ...

'', described race perseverance. It was discovered only in 1997 on a tiny rat-free island off the south coast, Jacqeumart Island. The snipe had survived there and began recolonising the main island after the rats had been removed.

Marine mammal

Marine mammals are aquatic mammals that rely on the ocean and other marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as seals, whales, manatees, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their ...

s have shown gradual recovery in the past decades. Sea lions

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

and southern elephant seal

The southern elephant seal (''Mirounga leonina'') is one of two species of elephant seals. It is the largest member of the clade Pinnipedia and the order Carnivora, as well as the largest extant marine mammal that is not a cetacean. It gets its ...

s have begun to re-colonize the island. Some southern right whales still come into bays in the winter to winter or calve most notably at Northwest Bay and Perseverance Harbour, but in much smaller number than in the Auckland Islands

The Auckland Islands (Māori: ''Motu Maha'' "Many islands" or ''Maungahuka'' "Snowy mountains") are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying , is surrounded by smaller Adams Islan ...

. Historically, fin whale

The fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus''), also known as finback whale or common rorqual and formerly known as herring whale or razorback whale, is a cetacean belonging to the parvorder of baleen whales. It is the second-longest species of ce ...

s used to inhabit close to shore.

The area is one of five subantarctic island groups designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Geology

Campbell Island is an extinct alkaline shield volcano that marine erosion has worn down into its present shape. The volcano has been extinct for some six million years and glacial ice cover prevented vegetation from growing on the island until approximately 15,000 years ago.Basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

, hawaiite

Hawaiite is an olivine basalt with a composition between alkali basalt and mugearite. It was first used as a name for some lavas found on the island of Hawaii.

It occurs during the later stages of volcanic activity on oceanic islands such as Ha ...

, mugearite

Mugearite () is a type of oligoclase-bearing basalt, comprising olivine, apatite, and opaque oxides. The main feldspar in mugearite is oligoclase.

Mugearite is a sodium-rich member of the alkaline magma series. In the TAS classification of vol ...

and trachyte

Trachyte () is an extrusive igneous rock composed mostly of alkali feldspar. It is usually light-colored and aphanitic (fine-grained), with minor amounts of mafic minerals, and is formed by the rapid cooling of lava enriched with silica and al ...

are the dominant volcanic rock

Volcanic rock (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) is a rock formed from lava erupted from a volcano. In other words, it differs from other igneous rock by being of volcanic origin. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic ...

s comprising Campbell Island. They were erupted between 6.5 and 11 million years ago during the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

epoch. The island is considered to be part of the submerged continent of Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as (Māori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83–79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L., ...

.

Research

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the New Zealand government had coastal watchers on the island with trained naturalists who made observations of the geology, flora, and fauna of Campbell Island.

To mark the 200th anniversary of its discovery, the Campbell Island Bicentennial Expedition (CIBE) was undertaken from December 2010 to February 2011. The research expedition was the largest multidisciplinary expedition to the island in over 20 years, and aimed to document the island's human history, assess recovery of the island's flora and invertebrate fauna since the removal of sheep and the world's largest rat eradication programme, study the island's plentiful but little understood streams and characterise the unusual stream fauna, and reconstruct past environmental conditions and deduce long term climate change from tarn sediment cores.

The expedition was run by the 50 Degrees South Trust, a charitable organisation established to further research and education on New Zealand's Subantarctic Islands, and to support the preservation and management of these World Heritage ecosystems. The expedition and the programme outputs can be followed at the CIBE website.

Gallery

elephant seal

Elephant seals are very large, oceangoing earless seals in the genus ''Mirounga''. Both species, the northern elephant seal (''M. angustirostris'') and the southern elephant seal (''M. leonina''), were hunted to the brink of extinction for oi ...

''Mirounga leonina'' resting in the tussock grasses

File:Campbell Island, New Zealand scene.jpg, New Zealand sea lion

The New Zealand sea lion (''Phocarctos hookeri''), once known as Hooker's sea lion, and as or (male) and (female) in Māori, is a species of sea lion that is endemic to New Zealand and primarily breeds on New Zealand's subantarctic Auckland ...

s disporting themselves among the tussock grass

File:Campbell Island Landscape.jpg, Campbell Island landscape (taken during an unusually warm and dry late summer)

File:Southern Royal Albatross (Diomedea epomophora) with chick on Campbell Island.jpg, Southern royal albatross

The southern royal albatross or toroa, (''Diomedea epomophora'') is a large seabird from the albatross family. At an average wingspan of above , it is one of the two largest species of albatross, together with the wandering albatross. Recent stu ...

, ''Diomedea epomophora'' with chick on mound nest on Campbell Island

File:Campbell Island and megaherbs.jpg, Campbell Island landscape with a megaherb

Megaherbs are a group of herbaceous wildflowers growing in the New Zealand subantarctic islands and on the other subantarctic islands. They are characterised by their great size, with huge leaves and very large and often unusually coloured flowers ...

community in the foreground

File:Southern Royal Albatross in flight.jpg, Southern royal albatross

The southern royal albatross or toroa, (''Diomedea epomophora'') is a large seabird from the albatross family. At an average wingspan of above , it is one of the two largest species of albatross, together with the wandering albatross. Recent stu ...

in flight

File:Pair of Southern Royal Albatrosses.jpg, Pair of southern royal albatross

The southern royal albatross or toroa, (''Diomedea epomophora'') is a large seabird from the albatross family. At an average wingspan of above , it is one of the two largest species of albatross, together with the wandering albatross. Recent stu ...

es

File:Campbell2.jpg, Sea lions playing at Northwest Bay

See also

* Megaherbs *Campbell teal

The Campbell teal or Campbell Island teal (''Anas nesiotis'') is a small, flightless, nocturnal species of dabbling duck of the genus ''Anas'' endemic to the Campbell Island group of New Zealand. It is sometimes considered conspecific with the ...

* Campbell Island group

The Campbell Islands (or Campbell Island Group) are a group of subantarctic islands, belonging to New Zealand. They lie about 600 km south of Stewart Island. The islands have a total area of , consisting of one big island, Campbell Isla ...

* New Zealand subantarctic islands

The New Zealand Subantarctic Islands comprise the five southernmost groups of the New Zealand outlying islands. They are collectively designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Most of the islands lie near the southeast edge of the largel ...

* List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

* List of islands

This is a list of the lists of islands in the world grouped by country, by continent, by body of water

A body of water or waterbody (often spelled water body) is any significant accumulation of water on the surface of Earth or another plan ...

* Desert island

A desert island, deserted island, or uninhabited island, is an island, islet or atoll that is not permanently populated by humans. Uninhabited islands are often depicted in films or stories about shipwrecked people, and are also used as stereot ...

* Rat Island, where rats have also been eradicated

References

External links

Topographic map

Campbell Island, NZMS 272/3, Edition 1, 1986.

* ttps://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/science/plants-animals-fungi/fungi/describing-the-fungi-of-new-zealand/subantarctic-fungi/subantarctic-islands/campbell-island Landcare Research - Campbell Island

Campbell Island Bicentennial Expedition

Campbell Island Freshwater Invertebrate Identification Keys

{{coord, 52, 32.4, S, 169, 8.7, E, region:NZ_type:isle, display=title Islands of the Campbell Islands New Zealand subantarctic islands Seabird colonies Island restoration Important Bird Areas of the Campbell Islands Subantarctic islands Seal hunting Whaling stations in New Zealand Volcanoes of the New Zealand outlying islands Miocene shield volcanoes Penguin colonies