CSS Merrimac on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

CSS ''Virginia'' was the first steam-powered

The hull's burned timbers were cut down past the vessel's original waterline, leaving just enough clearance to accommodate her large, twin-bladed

The hull's burned timbers were cut down past the vessel's original waterline, leaving just enough clearance to accommodate her large, twin-bladed  The ironclad's casemate had 14 gun ports, three each in the bow and stern, one firing directly along the ship's centerline, the two others angled at 45° from the center line; these six bow and stern gun ports had exterior iron shutters installed to protect their cannon. There were four gun ports on each

The ironclad's casemate had 14 gun ports, three each in the bow and stern, one firing directly along the ship's centerline, the two others angled at 45° from the center line; these six bow and stern gun ports had exterior iron shutters installed to protect their cannon. There were four gun ports on each

The Battle of Hampton Roads began on March 8, 1862, when ''Virginia'' engaged the blockading Union fleet. Despite an all-out effort to complete her, the new ironclad still had workmen on board when she sailed into Hampton Roads with her flotilla of five

The Battle of Hampton Roads began on March 8, 1862, when ''Virginia'' engaged the blockading Union fleet. Despite an all-out effort to complete her, the new ironclad still had workmen on board when she sailed into Hampton Roads with her flotilla of five  The first Union ship to be engaged by ''Virginia'' was the all-wood, sail-powered , which was first crippled during a furious cannon exchange, and then rammed in her forward starboard bow by ''Virginia''. As ''Cumberland'' began to sink, the port side half of ''Virginia''s iron ram was broken off, causing a bow leak in the ironclad. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', the captain of ordered his frigate into shallower water, where she soon grounded. ''Congress'' and ''Virginia'' traded cannon fire for an hour, after which the badly-damaged ''Congress'' finally surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. Outraged at such a breach of war protocol, in retaliation ''Virginia''s now angry captain, Commodore Franklin Buchanan, gave the order to open fire with hot-shot on the surrendered ''Congress'' as he rushed to ''Virginia''s exposed upper casemate deck, where he was injured by enemy rifle fire. ''Congress'', now set ablaze by the retaliatory shelling, burned for many hours into the night, a symbol of Confederate naval power and a costly wake-up call for the all-wood Union blockading squadron.

''Virginia'' did not emerge from the battle unscathed, however. Her hanging port side anchor was lost after ramming ''Cumberland''; the bow was leaking from the loss of the ram's port side half; shot from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and the shore-based Union batteries had riddled her smokestack, reducing her boilers' draft and already slow speed; two of her broadside cannon (without shutters) were put out of commission by shell hits; a number of her armor plates had been loosened; both of ''Virginia''s

The first Union ship to be engaged by ''Virginia'' was the all-wood, sail-powered , which was first crippled during a furious cannon exchange, and then rammed in her forward starboard bow by ''Virginia''. As ''Cumberland'' began to sink, the port side half of ''Virginia''s iron ram was broken off, causing a bow leak in the ironclad. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', the captain of ordered his frigate into shallower water, where she soon grounded. ''Congress'' and ''Virginia'' traded cannon fire for an hour, after which the badly-damaged ''Congress'' finally surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. Outraged at such a breach of war protocol, in retaliation ''Virginia''s now angry captain, Commodore Franklin Buchanan, gave the order to open fire with hot-shot on the surrendered ''Congress'' as he rushed to ''Virginia''s exposed upper casemate deck, where he was injured by enemy rifle fire. ''Congress'', now set ablaze by the retaliatory shelling, burned for many hours into the night, a symbol of Confederate naval power and a costly wake-up call for the all-wood Union blockading squadron.

''Virginia'' did not emerge from the battle unscathed, however. Her hanging port side anchor was lost after ramming ''Cumberland''; the bow was leaking from the loss of the ram's port side half; shot from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and the shore-based Union batteries had riddled her smokestack, reducing her boilers' draft and already slow speed; two of her broadside cannon (without shutters) were put out of commission by shell hits; a number of her armor plates had been loosened; both of ''Virginia''s

On May 10, 1862, advancing Union troops occupied

On May 10, 1862, advancing Union troops occupied

*Other pieces of ''Virginia'' did survive and are on display at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News and the American Civil War Museum in

*Other pieces of ''Virginia'' did survive and are on display at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News and the American Civil War Museum in

Pokahuntas Bell for Exposition

", April 13, 1907 *Starting around 1883, numerous souvenirs, made from recently salvaged iron and wood raised from ''Virginia''s sunken hulk, found a ready and willing market among eastern seaboard residents who remembered the historic first battle between ironclads. Various tokens, medals, medalets, sectional watch fobs, and other similar metal keepsakes are known to have been struck by private mints in limited quantities. Known examples still exist today, being held in both public and private collections, rarely coming up for public auction. Nine examples made from ''Virginia''s iron and copper can be found cataloged in great detail, with front and back photos, in David Schenkman's 1979 numismatic booklet listed in the Reference section (below). *The name of the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel, built in Hampton Roads in the general vicinity of the famous engagement, with both Virginia and federal funds, also reflects the more recent version.

The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship

', Archon Books, p. 398. *Besse, Sumner B., ''C. S. Ironclad Virginia and U. S. Ironclad Monitor'', Newport News, Virginia, The Mariner's Museum, 1978. . *DeKay, James, (1997) ''Monitor'', Ballantine Books, New York, NY. * * .

Library of VirginiaVirginia Historical SocietyMuseum of the Confederacy

in Richmond, Virginia

Website devoted to the CSS ''Virginia''Hampton Roads Visitor Guide

USS ''Monitor'' Center and Exhibit

, Newport News, Virginia

Mariner's Museum

Newport News, Virginia

Hampton Roads Naval Museum

Civil War Naval History

{{DEFAULTSORT:Virginia Ironclad warships of the Confederate States Navy Shipwrecks of the Virginia coast Ships built in Newport News, Virginia Battle of Hampton Roads 1862 ships Maritime incidents in May 1862 Shipwrecks of the American Civil War Scuttled vessels Naval magazine explosions

ironclad warship

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. T ...

built by the Confederate States Navy during the first year of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

; she was constructed as a casemate ironclad

The casemate ironclad was a type of iron or iron-armored gunboat briefly used in the American Civil War by both the Confederate States Navy and the Union Navy. Unlike a monitor-type ironclad which carried its armament encased in a separate a ...

using the razéed

A razee or razée is a sailing ship that has been cut down (''razeed'') to reduce the number of decks. The word is derived from the French ''vaisseau rasé'', meaning a razed (in the sense of shaved down) ship.

Seventeenth century

During the ...

(cut down) original lower hull and engines of the scuttled steam frigate . ''Virginia'' was one of the participants in the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

, opposing the Union's in March 1862. The battle is chiefly significant in naval history as the first battle between ironclads.

USS ''Merrimack'' becomes CSS ''Virginia''

When the Commonwealth ofVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

seceded from the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

in 1861, one of the important federal military bases threatened was Gosport Navy Yard (now Norfolk Naval Shipyard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility tha ...

) in Portsmouth, Virginia

Portsmouth is an independent city in southeast Virginia and across the Elizabeth River from Norfolk. As of the 2020 census, the population was 97,915. It is part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area.

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Naval M ...

. Accordingly, orders were sent to destroy the base rather than allow it to fall into Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between ...

hands. On the afternoon of 17 April, the day Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

seceded, Engineer in Chief B. F. Isherwood managed to get the frigate's engines lit. However, the previous night secessionists had sunk light boats between Craney Island and Sewell's Point

Sewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to th ...

, blocking the channel. On 20 April, before evacuating the Navy Yard, the U. S. Navy burned ''Merrimack'' to the waterline and sank her to preclude capture. When the Confederate government took possession of the fully provisioned yard, the base's new commander, Flag Officer French Forrest, contracted on May 18 to salvage the wreck of the frigate. This was completed by May 30, and she was towed into the shipyard's only dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

(today known as Drydock Number One), where the burned structures were removed.

The wreck was surveyed and her lower hull and machinery were discovered to be undamaged. Stephen Mallory, Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

decided to convert ''Merrimack'' into an ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

, since she was the only large ship with intact engines available in the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

area. Preliminary sketch designs were submitted by Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

s John Mercer Brooke

John Mercer Brooke (December 18, 1826 – December 14, 1906) was an American sailor, engineer, scientist, and educator. He was instrumental in the creation of the Transatlantic Cable, and was a noted marine and military innovator.

Early li ...

and John L. Porter

John Luke Porter (13 September 1813 – 4 December 1893) was a naval constructor for United States Navy and the Confederate States Navy.

Early life

Porter was born in Portsmouth, Virginia in 1813. His mother was Frances Pritchard, daughter of ...

, each of whom envisaged the ship as a casemate ironclad. Brooke's general design showed the bow and stern portions submerged, and his design was the one finally selected. The detailed design work would be completed by Porter, who was a trained naval constructor

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befo ...

. Porter had overall responsibility for the conversion, but Brooke was responsible for her iron plate and heavy ordnance, while William P. Williamson, Chief Engineer of the Navy, was responsible for the ship's machinery.

Reconstruction as an ironclad

The hull's burned timbers were cut down past the vessel's original waterline, leaving just enough clearance to accommodate her large, twin-bladed

The hull's burned timbers were cut down past the vessel's original waterline, leaving just enough clearance to accommodate her large, twin-bladed screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

. A new fantail

Fantails are small insectivorous songbirds of the genus ''Rhipidura'' in the family Rhipiduridae, native to Australasia, Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Most of the species are about long, specialist aerial feeders, and named as "f ...

and armored casemate were built atop a new main deck, and a v-shaped (bulwark) was added to her bow, which attached to the armored casemate. This forward and aft main deck and fantail were designed to stay submerged and were covered in iron plate, built up in two layers. The casemate was built of of oak and pine in several layers, topped with two layers of iron plating oriented perpendicular to each other, and angled at 36 degrees from horizontal to deflect fired enemy shells.

From reports in Northern newspapers, ''Virginia''s designers were aware of the Union plans to build an ironclad and assumed their similar ordnance would be unable to do much serious damage to such a ship. It was decided to equip their ironclad with a ram, an anachronism on a 19th century warship. ''Merrimacks steam engines, now part of ''Virginia'', were in poor working order; they had been slated for replacement when the decision was made to abandon the Norfolk naval yard. The salty Elizabeth River water and the addition of tons of iron armor and pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

ballast, added to the hull's unused spaces for needed stability after her initial refloat, and to submerge her unarmored lower levels, only added to her engines' propulsion issues. As completed, ''Virginia'' had a turning radius of about and required 45 minutes to complete a full circle, which would later prove to be a major handicap in battle with the far more nimble ''Monitor''.

The ironclad's casemate had 14 gun ports, three each in the bow and stern, one firing directly along the ship's centerline, the two others angled at 45° from the center line; these six bow and stern gun ports had exterior iron shutters installed to protect their cannon. There were four gun ports on each

The ironclad's casemate had 14 gun ports, three each in the bow and stern, one firing directly along the ship's centerline, the two others angled at 45° from the center line; these six bow and stern gun ports had exterior iron shutters installed to protect their cannon. There were four gun ports on each broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

; their protective iron shutters remained uninstalled during both days of the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

. ''Virginia''s battery consisted of four muzzle-loading single-banded Brooke rifle

The Brooke rifle was a type of rifled, muzzle-loading naval and coast defense gun designed by John Mercer Brooke, an officer in the Confederate States Navy. They were produced by plants in Richmond, Virginia, and Selma, Alabama, between 1861 and 1 ...

s and six smoothbore Dahlgren guns salvaged from the old ''Merrimack''. Two of the rifles, the bow and stern pivot guns, were caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge (firearms) , bore – regardless of how or where the bore is measured and whether the f ...

and weighed each. They fired a shell. The other two were cannon of about , one on each broadside. The 9-inch Dahlgrens were mounted three to a side; each weighed approximately and could fire a shell up to a range of (or 1.9 miles) at an elevation of 15°. Both amidship Dahlgrens nearest the boiler furnaces were fitted-out to fire heated shot

Heated shot or hot shot is round shot that is heated before firing from muzzle-loading cannons, for the purpose of setting fire to enemy warships, buildings, or equipment. The use of heated shot dates back centuries; it was a powerful weapon agains ...

. On her upper casemate deck were positioned two anti-boarding/personnel 12-pounder 12-pounder gun or 12-pdr, usually denotes a gun which fired a projectile of approximately 12 pounds.

Guns of this type include:

*12-pounder long gun, the naval muzzle-loader of the Age of Sail

*Canon de 12 de Vallière, French cannon of 1732

*Cano ...

Howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s.

''Virginia''s commanding officer, Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan

Franklin Buchanan (September 17, 1800 – May 11, 1874) was an officer in the United States Navy who became the only full admiral in the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. He also commanded the ironclad CSS ''Virginia''.

Early lif ...

, arrived to take command only a few days before her first sortie; the ironclad was placed in commission and equipped by her executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

, Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

Catesby ap Roger Jones

Catesby ap Roger Jones (April 15, 1821 – June 21, 1877) was an officer in the U.S. Navy who became a commander in the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. He assumed command of during the Battle of Hampton Roads and engaged in ...

.

Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads began on March 8, 1862, when ''Virginia'' engaged the blockading Union fleet. Despite an all-out effort to complete her, the new ironclad still had workmen on board when she sailed into Hampton Roads with her flotilla of five

The Battle of Hampton Roads began on March 8, 1862, when ''Virginia'' engaged the blockading Union fleet. Despite an all-out effort to complete her, the new ironclad still had workmen on board when she sailed into Hampton Roads with her flotilla of five CSN ''CSN'' may refer to:

Companies

* CSN Stores, former name of Wayfair, American e-commerce company

* CSN International (Christian Satellite Network), religious radio broadcaster based on radio station KAWZ in Twin Falls, Idaho

* ''Centrala Studies ...

support ships: (serving as ''Virginia''s tender) and , , , and .

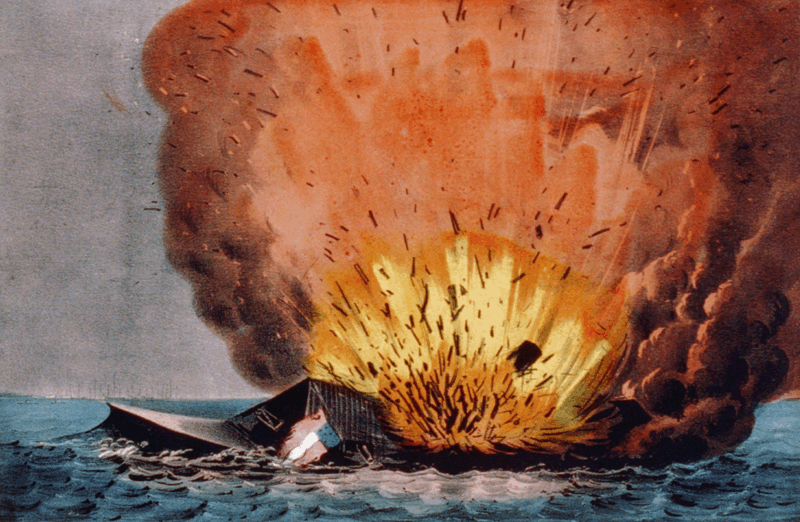

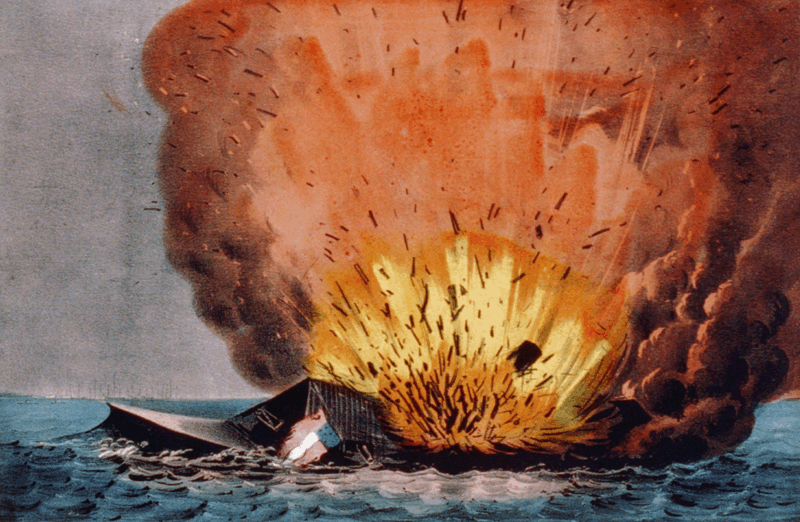

The first Union ship to be engaged by ''Virginia'' was the all-wood, sail-powered , which was first crippled during a furious cannon exchange, and then rammed in her forward starboard bow by ''Virginia''. As ''Cumberland'' began to sink, the port side half of ''Virginia''s iron ram was broken off, causing a bow leak in the ironclad. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', the captain of ordered his frigate into shallower water, where she soon grounded. ''Congress'' and ''Virginia'' traded cannon fire for an hour, after which the badly-damaged ''Congress'' finally surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. Outraged at such a breach of war protocol, in retaliation ''Virginia''s now angry captain, Commodore Franklin Buchanan, gave the order to open fire with hot-shot on the surrendered ''Congress'' as he rushed to ''Virginia''s exposed upper casemate deck, where he was injured by enemy rifle fire. ''Congress'', now set ablaze by the retaliatory shelling, burned for many hours into the night, a symbol of Confederate naval power and a costly wake-up call for the all-wood Union blockading squadron.

''Virginia'' did not emerge from the battle unscathed, however. Her hanging port side anchor was lost after ramming ''Cumberland''; the bow was leaking from the loss of the ram's port side half; shot from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and the shore-based Union batteries had riddled her smokestack, reducing her boilers' draft and already slow speed; two of her broadside cannon (without shutters) were put out of commission by shell hits; a number of her armor plates had been loosened; both of ''Virginia''s

The first Union ship to be engaged by ''Virginia'' was the all-wood, sail-powered , which was first crippled during a furious cannon exchange, and then rammed in her forward starboard bow by ''Virginia''. As ''Cumberland'' began to sink, the port side half of ''Virginia''s iron ram was broken off, causing a bow leak in the ironclad. Seeing what had happened to ''Cumberland'', the captain of ordered his frigate into shallower water, where she soon grounded. ''Congress'' and ''Virginia'' traded cannon fire for an hour, after which the badly-damaged ''Congress'' finally surrendered. While the surviving crewmen of ''Congress'' were being ferried off the ship, a Union battery on the north shore opened fire on ''Virginia''. Outraged at such a breach of war protocol, in retaliation ''Virginia''s now angry captain, Commodore Franklin Buchanan, gave the order to open fire with hot-shot on the surrendered ''Congress'' as he rushed to ''Virginia''s exposed upper casemate deck, where he was injured by enemy rifle fire. ''Congress'', now set ablaze by the retaliatory shelling, burned for many hours into the night, a symbol of Confederate naval power and a costly wake-up call for the all-wood Union blockading squadron.

''Virginia'' did not emerge from the battle unscathed, however. Her hanging port side anchor was lost after ramming ''Cumberland''; the bow was leaking from the loss of the ram's port side half; shot from ''Cumberland'', ''Congress'', and the shore-based Union batteries had riddled her smokestack, reducing her boilers' draft and already slow speed; two of her broadside cannon (without shutters) were put out of commission by shell hits; a number of her armor plates had been loosened; both of ''Virginia''s cutters

Cutter may refer to:

Tools

* Bolt cutter

* Box cutter, aka Stanley knife, a form of utility knife

* Cigar cutter

* Cookie cutter

* Glass cutter

* Meat cutter

* Milling cutter

* Paper cutter

* Side cutter

* Cutter, a type of hydraulic rescue to ...

had been shot away, as had both 12 pounder anti-boarding/anti-personnel howitzers, most of the deck stanchions

A stanchion () is a sturdy upright fixture that provides support for some other object. It can be a permanent fixture.

Types

In architecture stanchions are the upright iron bars in windows that pass through the eyes of the saddle bars or horizo ...

, railings, and both flagstaffs. Even so, the now-injured Buchanan ordered an attack on , which had run aground on a sandbar trying to escape ''Virginia''. However, because of the ironclad's draft (fully loaded), she was unable to get close enough to do any significant damage. It being late in the day, ''Virginia'' retired from the conflict with the expectation of returning the next day and completing the destruction of the remaining Union blockaders.

Later that night, arrived at Union-held Fort Monroe. She had been rushed to Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

, still not quite complete, all the way from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, in hopes of defending the force of wooden ships and preventing "the rebel monster" from further threatening the Union's blockading fleet and nearby cities, like Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

While under tow, she nearly foundered

Shipwrecking is an event that causes a shipwreck, such as a ship striking something that causes the ship to sink; the stranding of a ship on rocks, land or shoal; poor maintenance; or the destruction of a ship either intentionally or by violent ...

twice during heavy storms on her voyage south, arriving in Hampton Roads by the bright firelight from the still-burning triumph of ''Virginia''s first day of handiwork.

The next day, on March 9, 1862, the world's first battle between ironclads took place. The smaller, nimbler, and faster ''Monitor'' was able to outmaneuver the larger, slower ''Virginia'', but neither ship proved able to do any severe damage to the other, despite numerous shell hits by both combatants, many fired at virtually point-blank range. ''Monitor'' had a much lower freeboard and only its single, rotating, two-cannon gun turret and forward pilothouse sitting above her deck, and thus was much harder to hit with ''Virginia''s heavy cannon. After hours of shell exchanges, ''Monitor'' finally retreated into shallower water after a direct shell hit to her armored pilothouse forced her away from the conflict to assess the damage. The captain of the ''Monitor'', Lieutenant John L. Worden, had taken a direct gunpowder explosion to his face and eyes, blinding him, while looking through the pilothouse's narrow, horizontal viewing slits. ''Monitor'' remained in the shallows, but as it was late in the day, ''Virginia'' steamed for her home port, the battle ending without a clear victor: The captain of ''Virginia'' that day, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones

Catesby ap Roger Jones (April 15, 1821 – June 21, 1877) was an officer in the U.S. Navy who became a commander in the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. He assumed command of during the Battle of Hampton Roads and engaged in ...

, received advice from his pilots to depart over the sandbar toward Norfolk until the next day. Lieutenant Jones wanted to continue the fight, but the pilots emphasized that the ''Virginia'' had "nearly three miles to run to the bar" and that she could not remain and "take the ground on a falling tide." To prevent running aground, Lieutenant Jones reluctantly moved the ironclad back toward port. ''Virginia'' retired to the Gosport Naval Yard at Portsmouth, Virginia, and remained in drydock for repairs until April 4, 1862.

In the following month, the crew of ''Virginia'' were unsuccessful in their attempts to break the Union blockade. The blockade had been bolstered by the hastily ram-fitted paddle steamer , and SS ''Illinois'' as well as the and , which had been repaired. ''Virginia'' made several sorties back over to Hampton Roads hoping to draw ''Monitor'' into battle. ''Monitor'', however, was under strict orders not to re-engage; the two combatants would never battle again.

On April 11, the Confederate Navy sent Lieutenant Joseph Nicholson Barney, in command of the paddle side-wheeler , along with ''Virginia'' and five other ships in full view of the Union squadron, enticing them to fight. When it became clear that Union Navy ships were unwilling to fight, the CS Navy squadron moved in and captured three merchant ships, the brigs ''Marcus'' and ''Sabout'' and the schooner ''Catherine T. Dix''. Their ensigns were then hoisted "Union-side down" to further taunt the Union Navy into a fight, as they were towed back to Norfolk, with the help of .

By late April, the new Union ironclads USRC ''E. A. Stevens'' and had also joined the blockade. On May 8, 1862, ''Virginia'' and the James River Squadron

The James River Squadron was formed shortly after the secession of Virginia during the American Civil War. The squadron was part of the Virginia Navy before being transferred to the Confederate States Navy. The squadron is most notable for its r ...

ventured out when the Union ships began shelling the Confederate fortifications near Norfolk, but the Union ships retired under the shore batteries on the north side of the James River and on Rip Raps

Rip Raps is a small 15 acre (60,000 m²) artificial island at the mouth of the harbor area known as Hampton Roads in the independent city of Hampton in southeastern Virginia in the United States. Its name is derived from the Rip Rap Shoals in Hampt ...

island.

Destruction of CSS ''Virginia''

On May 10, 1862, advancing Union troops occupied

On May 10, 1862, advancing Union troops occupied Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

. Since ''Virginia'' was now a steam-powered heavy battery and no longer an ocean-going cruiser, her pilots judged her not seaworthy enough to enter the Atlantic, even if she were able to pass the Union blockade. ''Virginia'' was also unable to retreat further up the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesapea ...

due to her deep draft (fully loaded). In an attempt to reduce it, supplies and coal were dumped overboard, even though this exposed the ironclad's unarmored lower hull; this was still not enough to make a difference. Without a home port and no place to go, ''Virginia''s new captain, flag officer Josiah Tattnall III, reluctantly ordered her destruction in order to keep the ironclad from being captured. This task fell to Lieutenant Jones, the last man to leave ''Virginia'' after her cannons had been safely removed and carried to the Confederate Marine Corps base and fortifications at Drewry's Bluff

Drewry's Bluff is located in northeastern Chesterfield County, Virginia, in the United States. It was the site of Confederate Fort Darling during the American Civil War. It was named for a local landowner, Confederate Captain Augustus H. Drewry, w ...

. Early on the morning of May 11, 1862, off Craney Island, fire and powder trails reached the ironclads magazine and she was destroyed by a great explosion. What remained of the ship settled to the bottom of the harbor. Only a few remnants of ''Virginia'' have been recovered for preservation in museums; reports from the era indicate that her wreck was heavily salvaged following the war.

''Monitor'' was lost on December 31 of the same year, when the vessel was swamped by high waves in a violent storm while under tow by the tug USS ''Rhode Island'' off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Sixteen of her 62-member crew were either lost overboard or went down with the ironclad, while many others were saved by lifeboats sent from ''Rhode Island''. Subsequently, in August 1973, the wreckage was located on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean about 16 nautical miles (30 km; 18 mi) southeast of Cape Hatteras. Her upside-down turret was raised from beneath her deep, capsized

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel fro ...

wreck years later with the remains of two of her crew still aboard; they were later buried with full military honors on March 8, 2013, at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

in Washington, D.C.

Historical names: ''Merrimack'', ''Virginia'', ''Merrimac''

Although the Confederacy renamed the ship, she is still frequently referred to by her Union name. When she was first commissioned into the United States Navy in 1856, her name was ''Merrimack,'' with the ''K''; the name was derived from theMerrimack River

The Merrimack River (or Merrimac River, an occasional earlier spelling) is a river in the northeastern United States. It rises at the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin, New Hampshire, flows southward into Mas ...

near where she was built. She was the second ship of the U. S. Navy to be named for the Merrimack River, which is formed by the confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Pemigewasset

The Pemigewasset River , known locally as "The Pemi", is a river in the state of New Hampshire, the United States. It is in length and (with its tributaries) drains approximately . The name "Pemigewasset" comes from the Abenaki word ''bemijijoase ...

and Winnipesaukee

Lake Winnipesaukee () is the largest lake in the U.S. state of New Hampshire, located in the Lakes Region at the foothills of the White Mountains. It is approximately long (northwest-southeast) and from wide (northeast-southwest), covering & ...

rivers at Franklin, New Hampshire

Franklin is a city in Merrimack County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census, the population was 8,741, the least of New Hampshire's 13 cities. Franklin includes the village of West Franklin.

History

Situated at the confluence of the ...

. The Merrimack flows south across New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, then eastward across northeastern Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

before finally emptying in the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

at Newburyport, Massachusetts

Newburyport is a coastal city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States, northeast of Boston. The population was 18,289 at the 2020 census. A historic seaport with vibrant tourism industry, Newburyport includes part of Plum Island. The mo ...

.

After raising, restoring, and outfitting as an ironclad warship, the Confederacy bestowed on her the name ''Virginia''. Nonetheless, the Union continued to refer to the Confederate ironclad by either its original name, ''Merrimack'', or by the nickname "The Rebel Monster". In the aftermath of the Battle of Hampton Roads, the names ''Virginia'' and ''Merrimack'' were used interchangeably by both sides, as attested to by various newspapers and correspondence of the day. Navy reports and pre-1900 historians frequently misspelled the name as "Merrimac", which was actually an unrelated ship, hence "the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and the ''Merrimac''". Both spellings are still in use in the Hampton Roads area.

Memorial, heritage

*A large exhibit at theJamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

held in 1907 at Sewell's Point

Sewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to th ...

was the "Battle of the ''Merrimac'' and ''Monitor''," a large diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

that was housed in a special building.

*A small community in Montgomery County, Virginia, near where the coal burned by the Confederate ironclad was mined, is now known as Merrimac.

*The October 8, 1867, issue of the ''Norfolk Virginian'' newspaper carried a prominent classified advertisement in the paper's "Private Sales" section for the salvaged iron ram of CSS ''Virginia''. The ad states:

A RELIC OF WAR FOR SALE: The undersigned has had several offers for the IRON PROW! of the first iron-clad ever built, the celebrated Ram and Iron Clad Virginia, formerly the Merrimac. This immense RELIC WEIGHS 1,340 POUNDS, wrought iron, and as a sovereign of the war, and an object of interest as a revolution in naval warefare, would suit a Museum, State Institute, or some great public resort. Those desiring to purchase will please address D. A. UNDERDOWN, Wrecker, care of ''Virginian'' Office, Norfolk, Va.:It is unclear from the above whether this was the first iron ram that broke off and lodged in the starboard bow of the sinking USS ''Cumberland,'' during the first day of the Battle of Hampton Roads, or was the second iron ram affixed to ''Virginia''s bow at the time she was run aground and destroyed to avoid capture by Union forces; no further mention has been found concerning the final disposition of this historic artifact.

*Other pieces of ''Virginia'' did survive and are on display at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News and the American Civil War Museum in

*Other pieces of ''Virginia'' did survive and are on display at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News and the American Civil War Museum in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, where one of her anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek ἄγ ...

s resides on its front lawn.

*In 1907, an armor plate from the ship was melted down and used in the casting of the Pokahuntas Bell for the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

.''Richmond Times-Dispatch

The ''Richmond Times-Dispatch'' (''RTD'' or ''TD'' for short) is the primary daily newspaper in Richmond, Virginia, Richmond, the capital of Virginia, and the primary newspaper of record for the state of Virginia.

Circulation

The ''Times-Dispatc ...

'',Pokahuntas Bell for Exposition

", April 13, 1907 *Starting around 1883, numerous souvenirs, made from recently salvaged iron and wood raised from ''Virginia''s sunken hulk, found a ready and willing market among eastern seaboard residents who remembered the historic first battle between ironclads. Various tokens, medals, medalets, sectional watch fobs, and other similar metal keepsakes are known to have been struck by private mints in limited quantities. Known examples still exist today, being held in both public and private collections, rarely coming up for public auction. Nine examples made from ''Virginia''s iron and copper can be found cataloged in great detail, with front and back photos, in David Schenkman's 1979 numismatic booklet listed in the Reference section (below). *The name of the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel, built in Hampton Roads in the general vicinity of the famous engagement, with both Virginia and federal funds, also reflects the more recent version.

See also

* Bibliography of American Civil War naval historyNotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * *Nelson, James L. (2004). ''The Reign of Iron: The Story of the First Battling Ironclads, the ''Monitor'' and the ''Merrimack'' '', HarperCollins Publishers, New York, . * *Park, Carl D., (2007) ''Ironclad Down, USS ''Merrimack''-CSS ''Virginia'', From Construction to Destruction'', Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. . * *Quarstein, John V. (2000). ''C.S.S. ''Virginia'', Mistress of Hampton Roads'', self-published for the Virginia Civil War Battles and Leaders Series by H. E. Howard, Inc. * *Schenkman, David, (1979). ''Tokens & Medals Commemorating the Battle Between the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimac'' '' (sic), Hampton, Virginia, 28-page booklet (the second in a series of Special Articles on the Numismatics of The Commonwealth of Virginia), Virginia Numismatic Association. No ISSN or ISBN. * *Smith, Gene A., (1998). ''Iron and Heavy Guns, Duel Between the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimac'' '' (sic), Abilene, Texas, McWhiney Foundation Press, . *Further reading

* 82 pages. * Baxter, James Phinney (1968).The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship

', Archon Books, p. 398. *Besse, Sumner B., ''C. S. Ironclad Virginia and U. S. Ironclad Monitor'', Newport News, Virginia, The Mariner's Museum, 1978. . *DeKay, James, (1997) ''Monitor'', Ballantine Books, New York, NY. * * .

External links

Library of Virginia

in Richmond, Virginia

Website devoted to the CSS ''Virginia''

USS ''Monitor'' Center and Exhibit

, Newport News, Virginia

Mariner's Museum

Newport News, Virginia

Hampton Roads Naval Museum

Civil War Naval History

{{DEFAULTSORT:Virginia Ironclad warships of the Confederate States Navy Shipwrecks of the Virginia coast Ships built in Newport News, Virginia Battle of Hampton Roads 1862 ships Maritime incidents in May 1862 Shipwrecks of the American Civil War Scuttled vessels Naval magazine explosions