Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the astronomer

Jean Sylvain Bailly

Jean Sylvain Bailly (; 15 September 1736 – 12 November 1793) was a French astronomer, mathematician, freemason, and political leader of the early part of the French Revolution. He presided over the Tennis Court Oath, served as the mayor of Par ...

, and Franklin. In doing so, the committee concluded, through

blind trials that mesmerism only seemed to work when the subjects expected it, which discredited mesmerism and became the first major demonstration of the

placebo

A placebo ( ) is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value. Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like Saline (medicine), saline), sham surgery, and other procedures.

In general ...

effect, which was described at that time as "imagination". In 1781, he was elected a fellow of the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

.

Franklin's advocacy for religious tolerance in France contributed to arguments made by French philosophers and politicians that resulted in Louis XVI's signing of the

Edict of Versailles

The Edict of Versailles, also known as the Edict of Tolerance, was an official act that gave non-Catholics in France the access to civil rights formerly denied to them, which included the right to contract marriages without having to convert to t ...

in November 1787. This edict effectively nullified the

Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without ...

, which had denied non-Catholics civil status and the right to openly practice their faith.

Franklin also served as American minister to Sweden, although he never visited that country.

He negotiated a

treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal per ...

that was signed in April 1783. On August 27, 1783, in Paris, he witnessed the

world's first hydrogen balloon flight.

''

Le Globe

''Le Globe'' was a French newspaper, published in Paris by the Bureau du Globe between 1824 and 1832, and created with the goal of publishing Romantic creations. It was established by Pierre Leroux and the printer Alexandre Lachevardière. Afte ...

'', created by professor

Jacques Charles

Jacques Alexandre César Charles (November 12, 1746 – April 7, 1823) was a French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist.

Charles wrote almost nothing about mathematics, and most of what has been credited to him was due to mistaking ...

and

Les Frères Robert, was watched by a vast crowd as it rose from the

Champ de Mars

The Champ de Mars (; en, Field of Mars) is a large public greenspace in Paris, France, located in the seventh ''arrondissement'', between the Eiffel Tower to the northwest and the École Militaire to the southeast. The park is named after t ...

(now the site of the

Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed ...

).

Franklin became so enthusiastic that he subscribed financially to the next project to build a manned hydrogen balloon.

On December 1, 1783, Franklin was seated in the special enclosure for honored guests when ''

La Charlière'' took off from the

Jardin des Tuileries

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace ...

, piloted by Charles and

Nicolas-Louis Robert.

Return to America

When he returned home in 1785, Franklin occupied a position second only to that of

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

as the champion of American independence. He returned from France with an unexplained shortage of 100,000 pounds in Congressional funds. In response to a question from a member of Congress about this, Franklin, quoting the Bible, quipped, "Muzzle not the ox that treadeth out his master's grain." The missing funds were never again mentioned in Congress.

Le Ray honored him with a commissioned portrait painted by

Joseph Duplessis, which now hangs in the

National Portrait Gallery of the

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

in Washington, D.C. After his return, Franklin became an

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and freed his two slaves. He eventually became president of the

Pennsylvania Abolition Society.

President of Pennsylvania and Delegate to the Constitutional convention

Special balloting conducted October 18, 1785, unanimously elected him the sixth

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

of the

Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania

The Supreme Executive Council of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was the collective directorial executive branch of the Pennsylvanian state government between 1777 and 1790. It was headed by a president and a vice president (analogous to a gov ...

, replacing

John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

. The office was practically that of the governor. He held that office for slightly over three years, longer than any other, and served the constitutional limit of three full terms. Shortly after his initial election, he was re-elected to a full term on October 29, 1785, and again in the fall of 1786 and on October 31, 1787. In that capacity, he served as host to the

Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia.

He also served as a delegate to the

Convention. It was primarily an honorary position and he seldom engaged in debate.

Death

Franklin suffered from obesity throughout his middle-aged and later years, which resulted in multiple health problems, particularly

gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

, which worsened as he aged. In poor health during the signing of the US Constitution in 1787, he was rarely seen in public from then until his death.

Benjamin Franklin died from

pleuritic attack at his home in Philadelphia on April 17, 1790. He was aged 84 at the time of his death. His last words were reportedly, "a dying man can do nothing easy", to his daughter after she suggested that he change position in bed and lie on his side so he could breathe more easily. Franklin's death is described in the book ''The Life of Benjamin Franklin'', quoting from the account of

John Jones:

Approximately 20,000 people attended his funeral. He was interred in

Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia. Upon learning of his death, the Constitutional Assembly in Revolutionary France entered into a state of mourning for a period of three days, and memorial services were conducted in honor of Franklin throughout the country. In 1728, aged 22, Franklin wrote what he hoped would be his own epitaph:

Franklin's actual grave, however, as he specified in his final will, simply reads "Benjamin and Deborah Franklin".

Inventions and scientific inquiries

Franklin was a prodigious inventor. Among his many creations were the

lightning rod,

Franklin stove,

bifocal glasses and the flexible

urinary catheter. He never patented his inventions; in his

autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

he wrote, "... as we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously."

Electricity

Franklin started exploring the phenomenon of electricity in 1746 when he saw some of

Archibald Spencer

Archibald Spencer (January 1, 1698 – January 13, 1760) was a businessman, scientist, doctor, clergyman, and lecturer. He did seminars on science and for a while made a living at this. His lecture demonstrations were on medicine, light, and elect ...

's lectures using

static electricity

Static electricity is an imbalance of electric charges within or on the surface of a material or between materials. The charge remains until it is able to move away by means of an electric current or electrical discharge. Static electricity is na ...

for illustrations.

He proposed that "vitreous" and "resinous" electricity were not different types of "

electrical fluid" (as electricity was called then), but the same "fluid" under different pressures. (The same proposal was made independently that same year by

William Watson.) He was the first to label them as

positive and negative respectively, and he was the first to discover the principle of

conservation of charge

In physics, charge conservation is the principle that the total electric charge in an isolated system never changes. The net quantity of electric charge, the amount of positive charge minus the amount of negative charge in the universe, is alway ...

. In 1748, he constructed a multiple plate

capacitor

A capacitor is a device that stores electrical energy in an electric field by virtue of accumulating electric charges on two close surfaces insulated from each other. It is a passive electronic component with two terminals.

The effect of ...

, that he called an "electrical battery" (not a true battery like

Volta's pile) by placing eleven panes of glass sandwiched between lead plates, suspended with silk cords and connected by wires.

In pursuit of more pragmatic uses for electricity, remarking in spring 1749 that he felt "chagrin'd a little" that his experiments had heretofore resulted in "Nothing in this Way of Use to Mankind", he planned a practical demonstration. He proposed a dinner party where a turkey was to be killed via electric shock and roasted on an electrical spit. After having prepared several turkeys this way, he noted that "the birds kill'd in this manner eat uncommonly tender." Franklin recounted that in the process of one of these experiments, he was shocked by a pair of

Leyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, sometimes Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It ty ...

s, resulting in numbness in his arms that persisted for one evening, noting "I am Ashamed to have been Guilty of so Notorious a Blunder."

Franklin briefly investigated

electrotherapy

Electrotherapy is the use of electrical energy as a medical treatment. In medicine, the term ''electrotherapy'' can apply to a variety of treatments, including the use of electrical devices such as deep brain stimulators for neurological dis ...

, including the use of the

electric bath

The term electric bath applies to numerous devices. These include: an early form of tanning bed, which was featured on the RMS ''Olympic'', RMS ''Titanic'', SS ''Adriatic''{{cite web, url=http://www.victorianturkishbath.org/_6DIRECTORY/AtoZE ...

. This work led to the field becoming widely known. In recognition of his work with electricity, he received the

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

's

Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

in 1753, and in 1756, he became one of the few 18th-century Americans elected a fellow of the Society. The

CGS unit of electric charge has been named after him: one ''franklin'' (Fr) is equal to one

statcoulomb

The franklin (Fr) or statcoulomb (statC) electrostatic unit of charge (esu) is the physical unit for electrical charge used in the cgs-esu and Gaussian units. It is a derived unit given by

: 1 statC = 1 dyn1/2⋅cm = 1 cm3/2⋅g1/2⋅s−1.

Tha ...

.

Franklin advised Harvard University in its acquisition of new electrical laboratory apparatus after the complete loss of its original collection, in a fire that destroyed the original

Harvard Hall in 1764. The collection he assembled later became part of the

Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments (CHSI), established 1948, is "one of the three largest university collections of its kind in the world". Waywiser, the online catalog of the collection, lists over 60% of the co ...

, now on public display in its

Science Center.

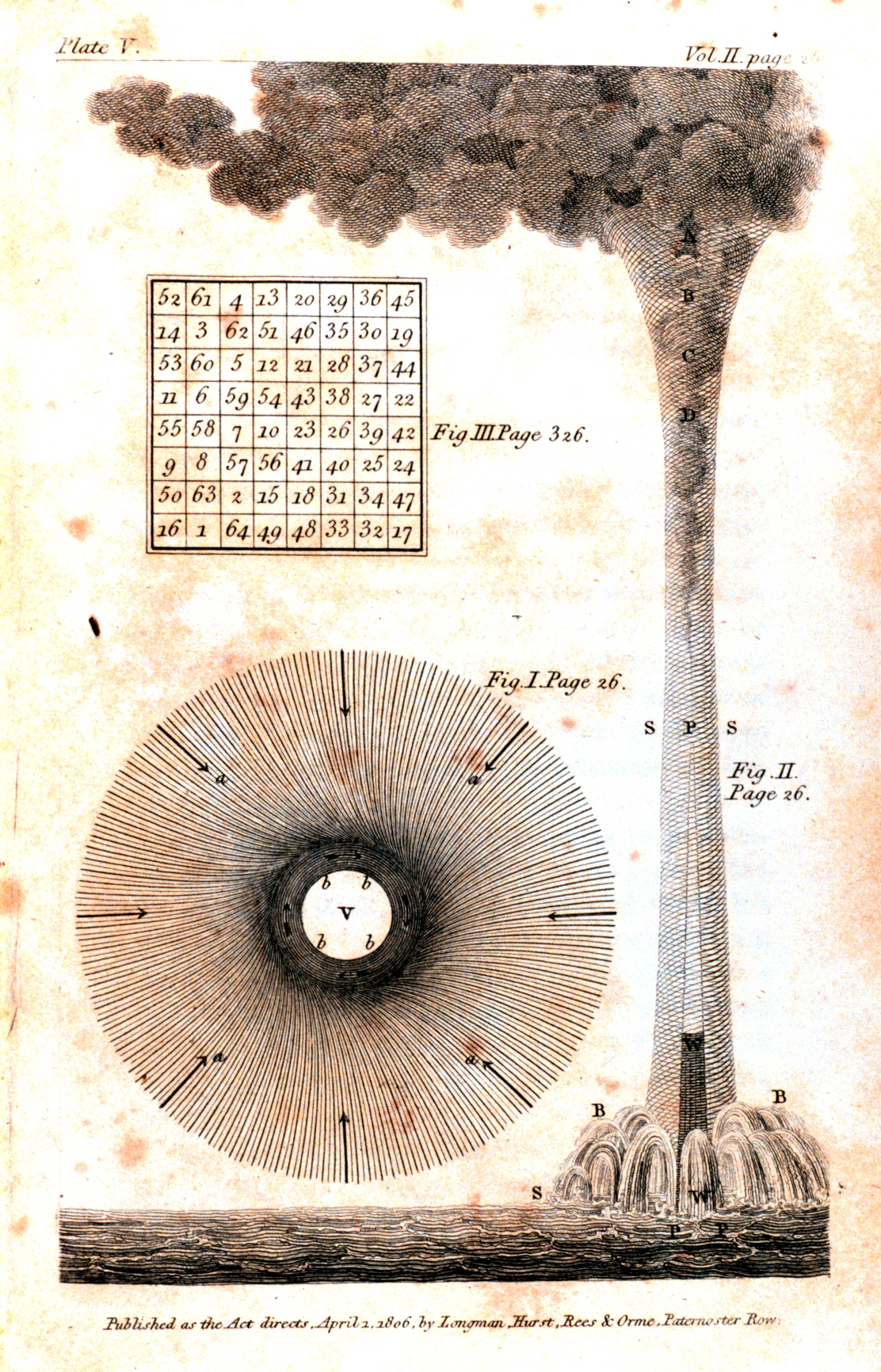

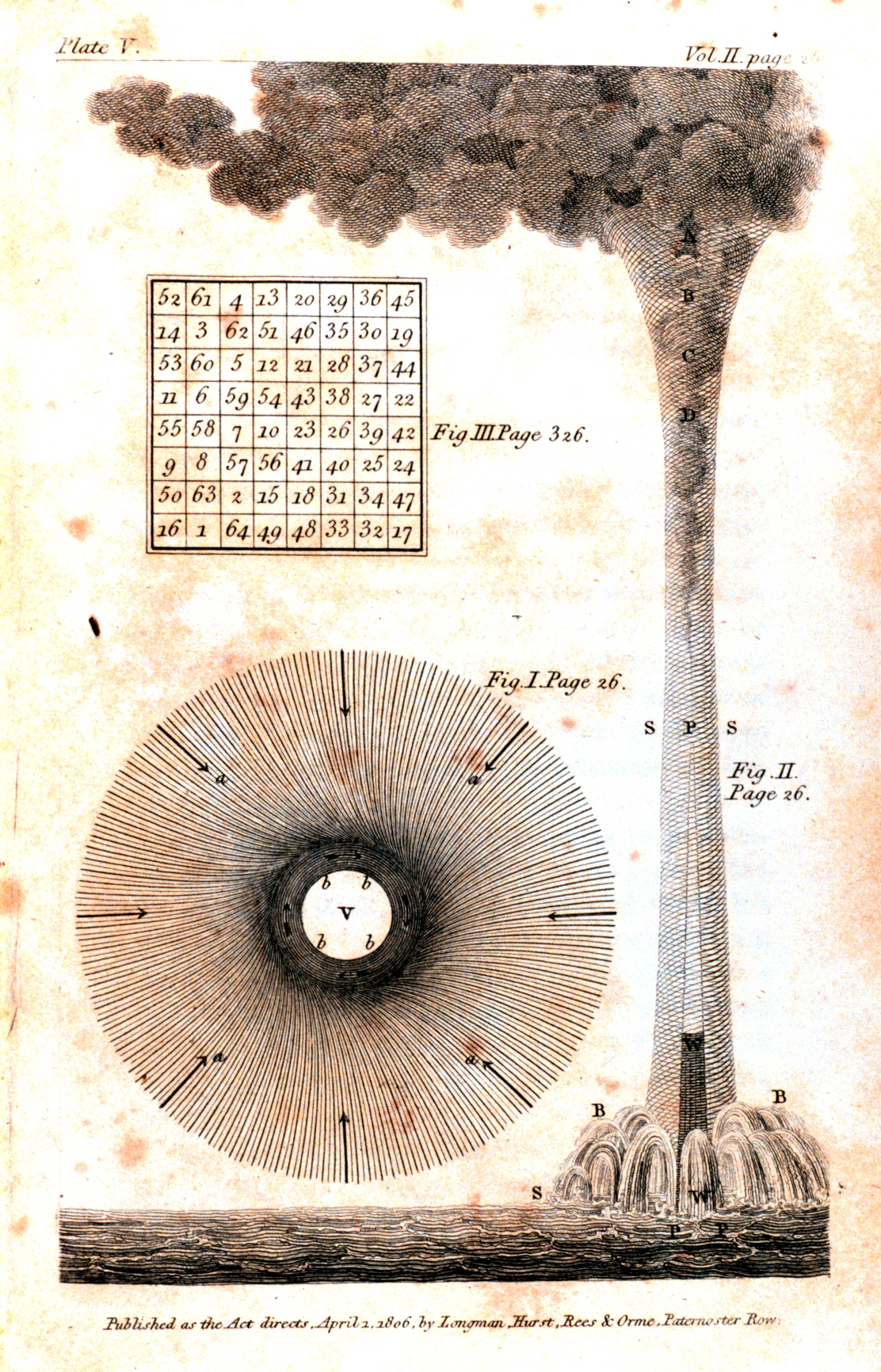

Kite experiment and lightning rod

Franklin published a proposal for an experiment to prove that

lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

is electricity by

flying a kite in a storm. On May 10, 1752,

Thomas-François Dalibard

Thomas-François Dalibard (born in Crannes-en-Champagne, France in 1709, died in 1778) was a French physicist who performed the first lightning rod experiment. He was married to the novelist and playwright Françoise-Thérèse Aumerle de Saint- ...

of France conducted Franklin's experiment using a iron rod instead of a kite, and he extracted electrical sparks from a cloud. On June 15, 1752, Franklin may possibly have conducted his well-known kite experiment in Philadelphia, successfully extracting sparks from a cloud. He described the experiment in his newspaper, ''

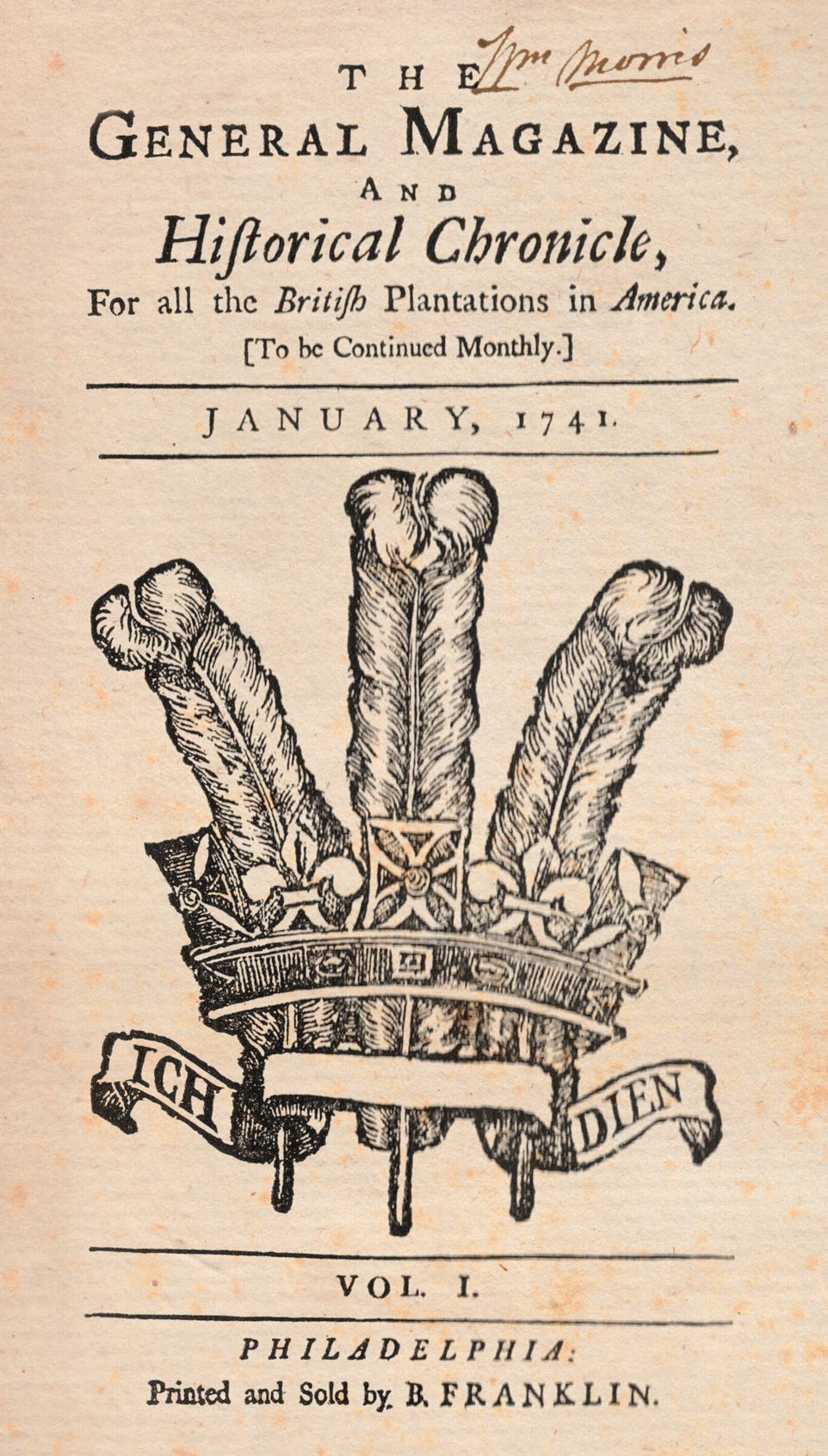

The Pennsylvania Gazette'', on October 19, 1752, without mentioning that he himself had performed it. This account was read to the Royal Society on December 21 and printed as such in the ''Philosophical Transactions''.

[National Archives]

The Kite Experiment, 19 October 1752

Retrieved February 6, 2017 Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

published an account with additional details in his 1767 ''History and Present Status of Electricity''. Franklin was careful to stand on an insulator, keeping dry under a roof to avoid the danger of

electric shock

Electrical injury is a physiological reaction caused by electric current passing through the body. The injury depends on the density of the current, tissue resistance and duration of contact. Very small currents may be imperceptible or produce a ...

. Others, such as

Georg Wilhelm Richmann

Georg Wilhelm Richmann () (22 July 1711 – 6 August 1753), (Old Style: 11 July 1711 – 26 July 1753) was a Russian Imperial physicist of Baltic German descent. Richmann did pioneering work on electricity, atmospheric electricity, and calorimetr ...

in Russia, were indeed electrocuted in performing lightning experiments during the months immediately following his experiment.

In his writings, Franklin indicates that he was aware of the dangers and offered alternative ways to demonstrate that lightning was electrical, as shown by his use of the concept of

electrical ground

In electrical engineering, ground or earth is a reference point in an electrical circuit from which voltages are measured, a common return path for electric current, or a direct physical connection to the Earth.

Electrical circuits may be co ...

. He did not perform this experiment in the way that is often pictured in popular literature, flying the kite and waiting to be struck by lightning, as it would have been dangerous. Instead he used the kite to collect some electric charge from a storm cloud, showing that lightning was electrical.

On October 19, 1752, in a letter to England with directions for repeating the experiment, he wrote:

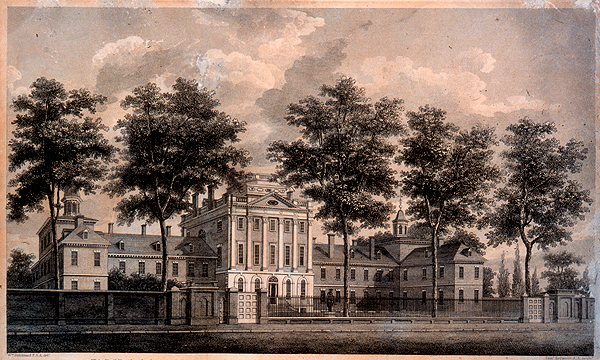

Franklin's electrical experiments led to his invention of the lightning rod. He said that conductors with a sharp rather than a smooth point could discharge silently and at a far greater distance. He surmised that this could help protect buildings from lightning by attaching "upright Rods of Iron, made sharp as a Needle and gilt to prevent Rusting, and from the Foot of those Rods a Wire down the outside of the Building into the Ground; ... Would not these pointed Rods probably draw the Electrical Fire silently out of a Cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible Mischief!" Following a series of experiments on Franklin's own house, lightning rods were installed on the Academy of Philadelphia (later the

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest- ...

) and the Pennsylvania State House (later

Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted by America's Founding Fathers. The structure forms the centerpi ...

) in 1752.

Population studies

Franklin had a major influence on the emerging science of

demography

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as ed ...

or population studies. In the 1730s and 1740s, he began taking notes on population growth, finding that the American population had the fastest growth rate on Earth. Emphasizing that population growth depended on food supplies, he emphasized the abundance of food and available farmland in America. He calculated that America's population was doubling every 20 years and would surpass that of England in a century. In 1751, he drafted

''Observations concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc.'' Four years later, it was anonymously printed in Boston and was quickly reproduced in Britain, where it influenced the economist

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

and later the demographer

Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, who credited Franklin for discovering a rule of population growth. Franklin's predictions how British mercantilism was unsustainable alarmed British leaders who did not want to be surpassed by the colonies, so they became more willing to impose restrictions on the colonial economy.

Kammen (1990) and Drake (2011) say Franklin's ''Observations concerning the Increase of Mankind'' (1755) stands alongside

Ezra Stiles

Ezra Stiles ( – May 12, 1795) was an American educator, academic, Congregationalist minister, theologian, and author. He is noted as the seventh president of Yale College (1778–1795) and one of the founders of Brown University. According ...

' "Discourse on Christian Union" (1760) as the leading works of 18th-century Anglo-American demography; Drake credits Franklin's "wide readership and prophetic insight". Franklin was also a pioneer in the study of slave demography, as shown in his 1755 essay. In his capacity as a farmer, he wrote at least one critique about the negative consequences of price controls, trade restrictions, and subsidy of the poor. This is succinctly preserved in his letter to the ''

London Chronicle'' published November 29, 1766, titled "On the Price of Corn, and Management of the poor".

Oceanography

As deputy postmaster, Franklin became interested in

North Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

circulation patterns. While in England in 1768, he heard a complaint from the Colonial Board of Customs: Why did it take British packet ships carrying mail several weeks longer to reach New York than it took an average merchant ship to reach

Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

? The merchantmen had a longer and more complex voyage because they left from London, while the packets left from

Falmouth in Cornwall. Franklin put the question to his cousin Timothy Folger, a

Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

whaler captain, who told him that merchant ships routinely avoided a strong eastbound mid-ocean current. The mail packet captains sailed dead into it, thus fighting an adverse current of . Franklin worked with Folger and other experienced ship captains, learning enough to chart the current and name it the

Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the Unit ...

, by which it is still known today.

Franklin published his Gulf Stream chart in 1770 in England, where it was ignored. Subsequent versions were printed in France in 1778 and the U.S. in 1786. The British original edition of the chart had been so thoroughly ignored that everyone assumed it was lost forever until Phil Richardson, a

Woods Hole oceanographer and Gulf Stream expert, discovered it in the

Bibliothèque Nationale

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

in Paris in 1980. This find received front-page coverage in ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''. It took many years for British sea captains to adopt Franklin's advice on navigating the current; once they did, they were able to trim two weeks from their sailing time. In 1853, the oceanographer and cartographer

Matthew Fontaine Maury noted that while Franklin charted and codified the Gulf Stream, he did not discover it:

An aging Franklin accumulated all his oceanographic findings in ''Maritime Observations'', published by the Philosophical Society's ''transactions'' in 1786. It contained ideas for

sea anchor

A sea anchor (also known as a parachute anchor, drift anchor, drift sock, para-anchor or boat brake) is a device that is streamed from a boat in heavy weather. Its purpose is to stabilize the vessel and to limit progress through the water. ...

s,

catamaran

A Formula 16 beachable catamaran

Powered catamaran passenger ferry at Salem, Massachusetts, United States

A catamaran () (informally, a "cat") is a multi-hulled watercraft featuring two parallel hulls of equal size. It is a geometry-sta ...

hulls,

watertight compartments, shipboard lightning rods and a soup bowl designed to stay stable in stormy weather.

Theories and experiments

Franklin was, along with his contemporary

Leonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( , ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, geographer, logician and engineer who founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made pioneering and influential discoveries ...

, the only major scientist who supported

Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

's

wave theory of light

In physics, physical optics, or wave optics, is the branch of optics that studies interference, diffraction, polarization, and other phenomena for which the ray approximation of geometric optics is not valid. This usage tends not to include effect ...

, which was basically ignored by the rest of the

scientific community

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many " sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional activities are als ...

. In the 18th century,

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

's

corpuscular theory

In optics, the corpuscular theory of light states that light is made up of small discrete particles called " corpuscles" (little particles) which travel in a straight line with a finite velocity and possess impetus. This was based on an alternate ...

was held to be true; it took

Thomas Young's well-known

slit experiment

In modern physics, the double-slit experiment is a demonstration that light and matter can display characteristics of both classically defined waves and particles; moreover, it displays the fundamentally probabilistic nature of quantum mechanic ...

in 1803 to persuade most scientists to believe Huygens's theory.

On October 21, 1743, according to the popular myth, a storm moving from the southwest denied Franklin the opportunity of witnessing a

lunar eclipse

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon moves into the Earth's shadow. Such alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six months, during the full moon phase, when the Moon's orbital plane is closest to the plane of the Ear ...

. He was said to have noted that the

prevailing winds

In meteorology, prevailing wind in a region of the Earth's surface is a surface wind that blows predominantly from a particular direction. The dominant winds are the trends in direction of wind with the highest speed over a particular point on ...

were actually from the northeast, contrary to what he had expected. In correspondence with his brother, he learned that the same storm had not reached Boston until after the eclipse, despite the fact that Boston is to the northeast of Philadelphia. He deduced that storms do not always travel in the direction of the prevailing wind, a concept that greatly influenced

meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

. After the Icelandic volcanic eruption of

Laki in 1783, and the subsequent harsh European winter of 1784, Franklin made observations on the causal nature of these two seemingly separate events. He wrote about them in a lecture series.

Though Franklin is famously associated with kites from his lightning experiments, he has also been noted by many for using kites to pull humans and ships across waterways.

George Pocock in the book ''A TREATISE on The Aeropleustic Art, or Navigation in the Air, by means of Kites, or Buoyant Sails'' noted being inspired by Benjamin Franklin's traction of his body by kite power across a waterway.

Franklin noted a principle of

refrigeration

The term refrigeration refers to the process of removing heat from an enclosed space or substance for the purpose of lowering the temperature.International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.phpASHRAE Terminology, ht ...

by observing that on a very hot day, he stayed cooler in a wet shirt in a breeze than he did in a dry one. To understand this phenomenon more clearly, he conducted experiments. In 1758 on a warm day in

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, England, he and fellow scientist

John Hadley experimented by continually wetting the ball of a mercury

thermometer

A thermometer is a device that measures temperature or a temperature gradient (the degree of hotness or coldness of an object). A thermometer has two important elements: (1) a temperature sensor (e.g. the bulb of a mercury-in-glass thermometer ...

with

ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again ...

and using

bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

to evaporate the ether. With each subsequent

evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when h ...

, the thermometer read a lower temperature, eventually reaching . Another thermometer showed that the room temperature was constant at . In his letter ''

Cooling by Evaporation'', Franklin noted that, "One may see the possibility of freezing a man to death on a warm summer's day."

According to

Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

, Franklin's experiments on the non-conduction of ice are worth mentioning, although the law of the general effect of

liquefaction

In materials science, liquefaction is a process that generates a liquid from a solid or a gas or that generates a non-liquid phase which behaves in accordance with fluid dynamics.

It occurs both naturally and artificially. As an example of th ...

on

electrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon ...

s is not attributed to Franklin. However, as reported in 1836 by Franklin's great-grandson Prof.

Alexander Dallas Bache

Alexander Dallas Bache (July 19, 1806 – February 17, 1867) was an American physicist, scientist, and surveyor who erected coastal fortifications and conducted a detailed survey to map the mideastern United States coastline. Originally an army ...

of the University of Pennsylvania, the law of the effect of heat on the conduction of bodies otherwise non-conductors, for example, glass, could be attributed to Franklin. Franklin wrote, "... A certain quantity of heat will make some bodies good conductors, that will not otherwise conduct ..." and again, "... And water, though naturally a good conductor, will not conduct well when frozen into ice."

While traveling on a ship, Franklin had observed that the wake of a ship

was diminished when the cooks scuttled their greasy water. He studied the effects on a large pond in

Clapham Common

Clapham Common is a large triangular urban park in Clapham, south London, England. Originally common land for the parishes of Battersea and Clapham, it was converted to parkland under the terms of the Metropolitan Commons Act 1878. It is of g ...

, London. "I fetched out a cruet of oil and dropt a little of it on the water ... though not more than a teaspoon full, produced an instant calm over a space of several yards square." He later used the trick to "calm the waters" by carrying "a little oil in the hollow joint of my cane".

Decision-making

In a 1772 letter to

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

, Franklin laid out the earliest known description of the Pro & Con list,

a common

decision-making

In psychology, decision-making (also spelled decision making and decisionmaking) is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several possible alternative options. It could be either ra ...

technique, now sometimes called a

decisional balance sheet

A decisional balance sheet or decision balance sheet is a tabular method for representing the pros and cons of different choices and for helping someone decide what to do in a certain circumstance. It is often used in working with ambivalence in p ...

:

Political, social, and religious views

Like the other advocates of

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

, Franklin emphasized that the new republic could survive only if the people were virtuous. All his life, he explored the role of civic and personal virtue, as expressed in ''Poor Richard's''

aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by ...

s. He felt that organized religion was necessary to keep men good to their fellow men, but rarely attended religious services himself. When he met

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

in Paris and asked his fellow member of the Enlightenment vanguard to bless his grandson, Voltaire said in English, "God and Liberty", and added, "this is the only appropriate benediction for the grandson of Monsieur Franklin."

Franklin's parents were both pious Puritans. The family attended the

Old South Church, the most liberal Puritan congregation in Boston, where Benjamin Franklin was baptized in 1706. Franklin's father, a poor chandler, owned a copy of a book, ''Bonifacius: Essays to Do Good'', by the Puritan preacher and family friend

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

, which Franklin often cited as a key influence on his life. "If I have been", Franklin wrote to Cotton Mather's son seventy years later, "a useful citizen, the public owes the advantage of it to that book." His first pen name, Silence Dogood, paid homage both to the book and to a widely known sermon by Mather. The book preached the importance of forming

voluntary association

A voluntary group or union (also sometimes called a voluntary organization, common-interest association, association, or society) is a group of individuals who enter into an agreement, usually as volunteers, to form a body (or organization) to ac ...

s to benefit society. Franklin learned about forming do-good associations from Mather, but his organizational skills made him the most influential force in making

voluntarism an enduring part of the American ethos.

Franklin formulated a presentation of his beliefs and published it in 1728. It did not mention many of the Puritan ideas regarding salvation, the

divinity of Jesus

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Diff ...

, or indeed much religious dogma. He classified himself as a

deist in his 1771 autobiography, although he still considered himself a Christian.

He retained a strong faith in a God as the wellspring of morality and goodness in man, and as a Providential actor in history responsible for American independence.

At a critical impasse during the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, he attempted to introduce the practice of daily common prayer with these words:

The motion met with resistance and was never brought to a vote.

Franklin was an enthusiastic supporter of the evangelical minister

George Whitefield

George Whitefield (; 30 September 1770), also known as George Whitfield, was an Anglican cleric and evangelist who was one of the founders of Methodism and the evangelical movement.

Born in Gloucester, he matriculated at Pembroke College at ...

during the

First Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affecte ...

. He did not himself subscribe to Whitefield's theology, but he admired Whitefield for exhorting people to worship God through good works. He published all of Whitefield's sermons and journals, thereby earning a lot of money and boosting the Great Awakening.

When he stopped attending church, Franklin wrote in his autobiography:

Franklin retained a lifelong commitment to the Puritan virtues and political values he had grown up with, and through his civic work and publishing, he succeeded in passing these values into the American culture permanently. He had a "passion for virtue". These Puritan values included his devotion to egalitarianism, education, industry, thrift, honesty, temperance, charity and community spirit.

The classical authors read in the Enlightenment period taught an abstract ideal of republican government based on hierarchical social orders of king, aristocracy and commoners. It was widely believed that English liberties relied on their balance of power, but also hierarchal deference to the privileged class. "Puritanism ... and the epidemic evangelism of the mid-eighteenth century, had created challenges to the traditional notions of social stratification"

by preaching that the Bible taught all men are equal, that the true value of a man lies in his moral behavior, not his class, and that all men can be saved.

[Bailyn, 1992, p. 303] Franklin, steeped in Puritanism and an enthusiastic supporter of the evangelical movement, rejected the salvation dogma but embraced the radical notion of egalitarian democracy.

Franklin's commitment to teach these values was itself something he gained from his Puritan upbringing, with its stress on "inculcating virtue and character in themselves and their communities." These Puritan values and the desire to pass them on, were one of his quintessentially American characteristics and helped shape the character of the nation.

Max Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society. His ideas p ...

considered Franklin's ethical writings a culmination of the

Protestant ethic, which ethic created the social conditions necessary for the birth of

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

.

One of his notable characteristics was his respect, tolerance and promotion of all churches. Referring to his experience in Philadelphia, he wrote in his autobiography, "new Places of worship were continually wanted, and generally erected by voluntary Contribution, my Mite for such purpose, whatever might be the Sect, was never refused."

"He helped create a new type of nation that would draw strength from its religious

pluralism."

[ Isaacson, 2004, pp. 93ff] The evangelical revivalists who were active mid-century, such as Whitefield, were the greatest advocates of religious freedom, "claiming liberty of conscience to be an 'inalienable right of every rational creature.'" Whitefield's supporters in Philadelphia, including Franklin, erected "a large, new hall, that ... could provide a pulpit to anyone of any belief." Franklin's rejection of dogma and doctrine and his stress on the God of ethics and morality and

civic virtue

Civic virtue is the harvesting of habits important for the success of a society. Closely linked to the concept of citizenship, civic virtue is often conceived as the dedication of citizens to the common welfare of each other even at the cost of ...

made him the "prophet of tolerance".

He composed "A Parable Against Persecution", an apocryphal 51st chapter of Genesis in which God teaches Abraham the duty of tolerance. While he was living in London in 1774, he was present at the birth of

British Unitarianism

The General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches (GAUFCC or colloquially British Unitarians) is the umbrella organisation for Unitarian, Free Christians, and other liberal religious congregations in the United Kingdom and Irelan ...

, attending the inaugural session of the

Essex Street Chapel, at which

Theophilus Lindsey drew together the first avowedly

Unitarian congregation in England; this was somewhat politically risky and pushed religious tolerance to new boundaries, as a denial of the doctrine of the

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

was illegal until

the 1813 Act.

Although his parents had intended for him a career in the church,

Franklin as a young man adopted the Enlightenment religious belief in deism, that God's truths can be found entirely through nature and reason, declaring, "I soon became a thorough Deist." He rejected Christian dogma in a 1725 pamphlet ''

A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain'', which he later saw as an embarrassment,

[ Isaacson, 2004, p. 45] while simultaneously asserting that God is "all wise,

all good,

all powerful."

He defended his rejection of religious dogma with these words: "I think opinions should be judged by their influences and effects; and if a man holds none that tend to make him less virtuous or more vicious, it may be concluded that he holds none that are dangerous, which I hope is the case with me." After the disillusioning experience of seeing the decay in his own moral standards, and those of two friends in London whom he had converted to deism, Franklin turned back to a belief in the importance of organized religion, on the pragmatic grounds that without God and organized churches, man will not be good. Moreover, because of his proposal that prayers be said in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, many have contended that in his later life he became a pious Christian.

According to David Morgan, Franklin was a proponent of religion in general. He prayed to "Powerful Goodness" and referred to God as "the infinite".

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

noted that he was a mirror in which people saw their own religion: "The

Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

thought him almost a Catholic. The

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

claimed him as one of them. The

Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

thought him half a Presbyterian, and the

Friends

''Friends'' is an American television sitcom created by David Crane and Marta Kauffman, which aired on NBC from September 22, 1994, to May 6, 2004, lasting ten seasons. With an ensemble cast starring Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Li ...

believed him a wet Quaker." Whatever else Franklin was, concludes Morgan, "he was a true champion of generic religion." In a letter to Richard Price, Franklin states that he believes religion should support itself without help from the government, claiming, "When a Religion is good, I conceive that it will support itself; and, when it cannot support itself, and God does not take care to support, so that its Professors are oblig'd to call for the help of the Civil Power, it is a sign, I apprehend, of its being a bad one."

In 1790, just about a month before he died, Franklin wrote a letter to

Ezra Stiles

Ezra Stiles ( – May 12, 1795) was an American educator, academic, Congregationalist minister, theologian, and author. He is noted as the seventh president of Yale College (1778–1795) and one of the founders of Brown University. According ...

, president of

Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

, who had asked him his views on religion:

On July 4, 1776, Congress appointed a three-member committee composed of Franklin, Jefferson, and Adams to design the

Great Seal of the United States. Franklin's proposal (which was not adopted) featured the motto: "Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God" and a scene from the

Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

, with

Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu ( Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pr ...

, the

Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

, the

pillar of fire, and

George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

depicted as

pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

. The design that was produced was not acted upon by Congress, and the Great Seal's design was not finalized until a third committee was appointed in 1782.

Franklin strongly supported the right to

freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

:

Thirteen Virtues

Franklin sought to cultivate his character by a plan of 13 virtues, which he developed at age 20 (in 1726) and continued to practice in some form for the rest of his life. His autobiography lists his 13 virtues as:

#

Temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation."

#

Silence

Silence is the absence of ambient audible sound, the emission of sounds of such low intensity that they do not draw attention to themselves, or the state of having ceased to produce sounds; this latter sense can be extended to apply to the c ...

. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation."

#

Order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

#

Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

#

Frugality. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

# Industry. Lose no time; be always employ'd in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

#

Sincerity. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

#

Justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

#

Moderation. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

#

Cleanliness. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, clothes, or habitation.

#

Tranquility

Tranquillity (also spelled tranquility) is the quality or state of being tranquil; that is, calm, serene, and worry-free. The word tranquillity appears in numerous texts ranging from the religious writings of Buddhism, where the term ''passaddhi'' ...

. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

#

Chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when ma ...

. Rarely use

venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another's peace or reputation.

#

Humility

Humility is the quality of being humble. Dictionary definitions accentuate humility as a low self-regard and sense of unworthiness. In a religious context humility can mean a recognition of self in relation to a deity (i.e. God), and subsequent ...

. Imitate Jesus and

Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

.

Franklin did not try to work on them all at once. Instead, he would work on one and only one each week "leaving all others to their ordinary chance." While he did not adhere completely to the enumerated virtues, and by his own admission he fell short of them many times, he believed the attempt made him a better man, contributing greatly to his success and happiness, which is why in his autobiography, he devoted more pages to this plan than to any other single point and wrote, "I hope, therefore, that some of my descendants may follow the example and reap the benefit."

Slavery

Franklin owned as many as seven slaves, including two men who worked in his household and his shop. He posted paid ads for the sale of slaves and for the capture of runaway slaves and allowed the sale of slaves in his general store. However, he later became an outspoken critic of slavery. In 1758, he advocated the opening of a school for the education of black slaves in Philadelphia. He took two slaves to England with him, Peter and King. King escaped with a woman to live in the outskirts of London, and by 1758 he was working for a household in

Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

. After returning from England in 1762, Franklin became notably more abolitionist in nature, attacking American slavery. In the wake of ''

Somerset v Stewart'', he voiced frustration at British abolitionists:

Franklin, however, refused to publicly debate the issue of slavery at the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

At the time of the American founding, there were about half a million slaves in the United States, mostly in the five southernmost states, where they made up 40% of the population. Many of the leading American foundersmost notably Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

owned slaves, but many others did not. Benjamin Franklin thought that slavery was "an atrocious debasement of human nature" and "a source of serious evils." He and

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (April 19, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, educa ...

founded the

Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery in 1774. In 1790, Quakers from New York and Pennsylvania presented their petition for abolition to Congress. Their argument against slavery was backed by the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society.

In his later years, as Congress was forced to deal with the issue of slavery, Franklin wrote several essays that stressed the importance of the

abolition of slavery and of the integration of African Americans into American society. These writings included:

* ''

An Address to the Public'' (1789)

* ''

A Plan for Improving the Condition of the Free Blacks'' (1789)

* ''Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim on the Slave Trade'' (1790)

Vegetarianism

Franklin became a vegetarian when he was a teenager apprenticing at a print shop, after coming upon a book by the early vegetarian advocate

Thomas Tryon

Thomas Tryon (6 September 1634 – 21 August 1703) was an English sugar merchant, author of popular self-help books, and early advocate of animal rights and vegetarianism. Life

Born in 1634 in Bibury near Cirencester, Gloucestershire, England, ...

. In addition, he would have also been familiar with the moral arguments espoused by prominent vegetarian Quakers in colonial Pennsylvania, such as

Benjamin Lay and

John Woolman. His reasons for vegetarianism were based on health, ethics, and economy:

Franklin also declared the consumption of meat to be "unprovoked murder". Despite his convictions, he

began to eat fish after being tempted by fried cod on a boat sailing from Boston, justifying the eating of animals by observing that the fish's stomach contained other fish. Nonetheless, he recognized the faulty ethics in this argument and would continue to be a vegetarian on and off. He was "excited" by

tofu

Tofu (), also known as bean curd in English, is a food prepared by coagulating soy milk and then pressing the resulting curds into solid white blocks of varying softness; it can be ''silken'', ''soft'', ''firm'', ''extra firm'' or ''super f ...

, which he learned of from the writings of a Spanish missionary to South East Asia,

Domingo Fernández Navarrete. Franklin sent a sample of

soybean

The soybean, soy bean, or soya bean (''Glycine max'') is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean, which has numerous uses.

Traditional unfermented food uses of soybeans include soy milk, from which tofu ...

s to prominent American botanist

John Bartram

John Bartram (March 23, 1699 – September 22, 1777) was an American botanist, horticulturist, and explorer, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for most of his career. Swedish botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus said he was the "greatest na ...

and had previously written to British diplomat and Chinese trade expert

James Flint inquiring as to how tofu was made,

with their correspondence believed to be the first documented use of the word "tofu" in the English language.

Franklin's "Second Reply to ''Vindex Patriae''", a 1766 letter advocating self-sufficiency and less dependence on England, lists various examples of the bounty of American agricultural products, and does not mention meat.

Detailing new American customs, he wrote that, "

ey resolved last spring to eat no more lamb; and not a joint of lamb has since been seen on any of their tables … the sweet little creatures are all alive to this day, with the prettiest fleeces on their backs imaginable."

View on inoculation

The concept of preventing

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

by

variolation was introduced to colonial America by an African slave named

Onesimus via his owner

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

in the early eighteenth century, but the procedure was not immediately accepted.

James Franklin's newspaper carried articles in 1721 that vigorously denounced the concept.

However, by 1736 Benjamin Franklin, by then a prominent Boston citizen, was known as a supporter of the procedure. Therefore, when four-year-old "Franky" died of smallpox, opponents of the procedure circulated rumors that the child had been inoculated, and that this was the cause of his subsequent death. When Franklin became aware of this gossip, he placed a notice in the Pennsylvania Gazette, stating: "I do hereby sincerely declare, that he was not inoculated, but receiv'd the Distemper in the common Way of Infection ... I intended to have my Child inoculated.". The child had a bad case of flux

diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin w ...

, and his parents had waited for him to get well before having him inoculated. Franklin wrote in his Autobiography: "In 1736 I lost one of my sons, a fine boy of four years old, by the small-pox, taken in the common way. I long regretted bitterly, and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation. This I mention for the sake of parents who omit that operation, on the supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a child died under it; my example showing that the regret may be the same either way, and that, therefore, the safer should be chosen."

Interests and activities

Musical endeavors

Franklin is known to have played the violin, the harp, and the guitar. He also composed music, notably a

string quartet

The term string quartet can refer to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two violinist ...

in

early classical style. While he was in London, he developed a much-improved version of the

glass harmonica, in which the glasses rotate on a shaft, with the player's fingers held steady, instead of the other way around. He worked with the London glassblower Charles James to create it, and instruments based on his mechanical version soon found their way to other parts of Europe.

Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have le ...

, a fan of Franklin's enlightened ideas, had a glass harmonica in his instrument collection.

Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

composed for Franklin's glass harmonica,

as did

Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

.

Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style ...

used the instrument in the accompaniment to Amelia's aria "Par che mi dica ancora" in the tragic opera ''

Il castello di Kenilworth'' (1821),

as did

Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (; 9 October 183516 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic music, Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Piano C ...

in his 1886 ''

The Carnival of the Animals''.

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

calls for the glass harmonica in his 1917 ''

Die Frau ohne Schatten'',

and numerous other composers used Franklin's instrument as well.

Chess

Franklin was an avid

chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

player. He was playing chess by around 1733, making him the first chess player known by name in the American colonies.

His essay on "

The Morals of Chess

"The Morals of Chess" is an essay on chess by the American intellectual Benjamin Franklin, which was first published in the ''Columbian Magazine'' in December 1786.

Franklin, who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, played chess ...

" in ''

Columbian Magazine

The ''Columbian Magazine'', also known as the ''Columbian Magazine or Monthly Miscellany'', was a monthly American literary magazine established by Mathew Carey, Charles Cist, William Spotswood, Thomas Seddon, and James Trenchard. It was publish ...

'' in December 1786 is the second known writing on chess in America.

This essay in praise of chess and prescribing a code of behavior for the game has been widely reprinted and translated. He and a friend used chess as a means of learning the Italian language, which both were studying; the winner of each game between them had the right to assign a task, such as parts of the Italian grammar to be learned by heart, to be performed by the loser before their next meeting.

Franklin was able to play chess more frequently against stronger opposition during his many years as a civil servant and diplomat in England, where the game was far better established than in America. He was able to improve his playing standard by facing more experienced players during this period. He regularly attended

Old Slaughter's Coffee House

Old Slaughter's Coffee House was a coffee house in St Martin's Lane in London. Opened in 1692 by Thomas Slaughter, it was the haunt of many of the important personages of the period. The building was demolished in 1843 when Cranbourn Street was c ...

in London for chess and socializing, making many important personal contacts. While in Paris, both as a visitor and later as ambassador, he visited the famous

Café de la Régence

The Café de la Régence in Paris was an important European centre of chess in the 18th and 19th centuries. All important chess masters of the time played there.

The Café's masters included, but are not limited to:

* Paul Morphy

* François ...

, which France's strongest players made their regular meeting place. No records of his games have survived, so it is not possible to ascertain his playing strength in modern terms.

Franklin was inducted into the

U.S. Chess Hall of Fame in 1999.

The Franklin Mercantile Chess Club in Philadelphia, the second oldest chess club in the U.S., is named in his honor.

Legacy

Bequest

Franklin

bequeathed

A bequest is property given by will. Historically, the term ''bequest'' was used for personal property given by will and ''deviser'' for real property. Today, the two words are used interchangeably.

The word ''bequeath'' is a verb form for the act ...

£1,000 (about $4,400 at the time, or about $125,000 in 2021 dollars) each to the cities of Boston and Philadelphia, in trust to gather interest for 200 years. The trust began in 1785 when the French mathematician

Charles-Joseph Mathon de la Cour, who admired Franklin greatly, wrote a friendly parody of Franklin's ''Poor Richard's Almanack'' called ''Fortunate Richard''. The main character leaves a smallish amount of money in his will, five lots of 100 ''

livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 g ...

'', to collect interest over one, two, three, four or five full centuries, with the resulting astronomical sums to be spent on impossibly elaborate utopian projects. Franklin, who was 79 years old at the time, wrote thanking him for a great idea and telling him that he had decided to leave a bequest of 1,000 pounds each to his native Boston and his adopted Philadelphia.

By 1990, more than $2,000,000 had accumulated in Franklin's Philadelphia trust, which had loaned the money to local residents. From 1940 to 1990, the money was used mostly for mortgage loans. When the trust came due, Philadelphia decided to spend it on scholarships for local high school students. Franklin's Boston trust fund accumulated almost $5,000,000 during that same time; at the end of its first 100 years a portion was allocated to help establish a

trade school that became the

Franklin Institute of Boston, and the entire fund was later dedicated to supporting this institute.

In 1787, a group of prominent ministers in

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster, ( ; pdc, Lengeschder) is a city in and the county seat of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It is one of the oldest inland cities in the United States. With a population at the 2020 census of 58,039, it ranks 11th in population amon ...

, proposed the foundation of a new college named in Franklin's honor. Franklin donated £200 towards the development of Franklin College (now called

Franklin & Marshall College

Franklin & Marshall College (F&M) is a private liberal arts college in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. It employs 175 full-time faculty members and has a student body of approximately 2,400 full-time students. It was founded upon the merger of Frank ...

).

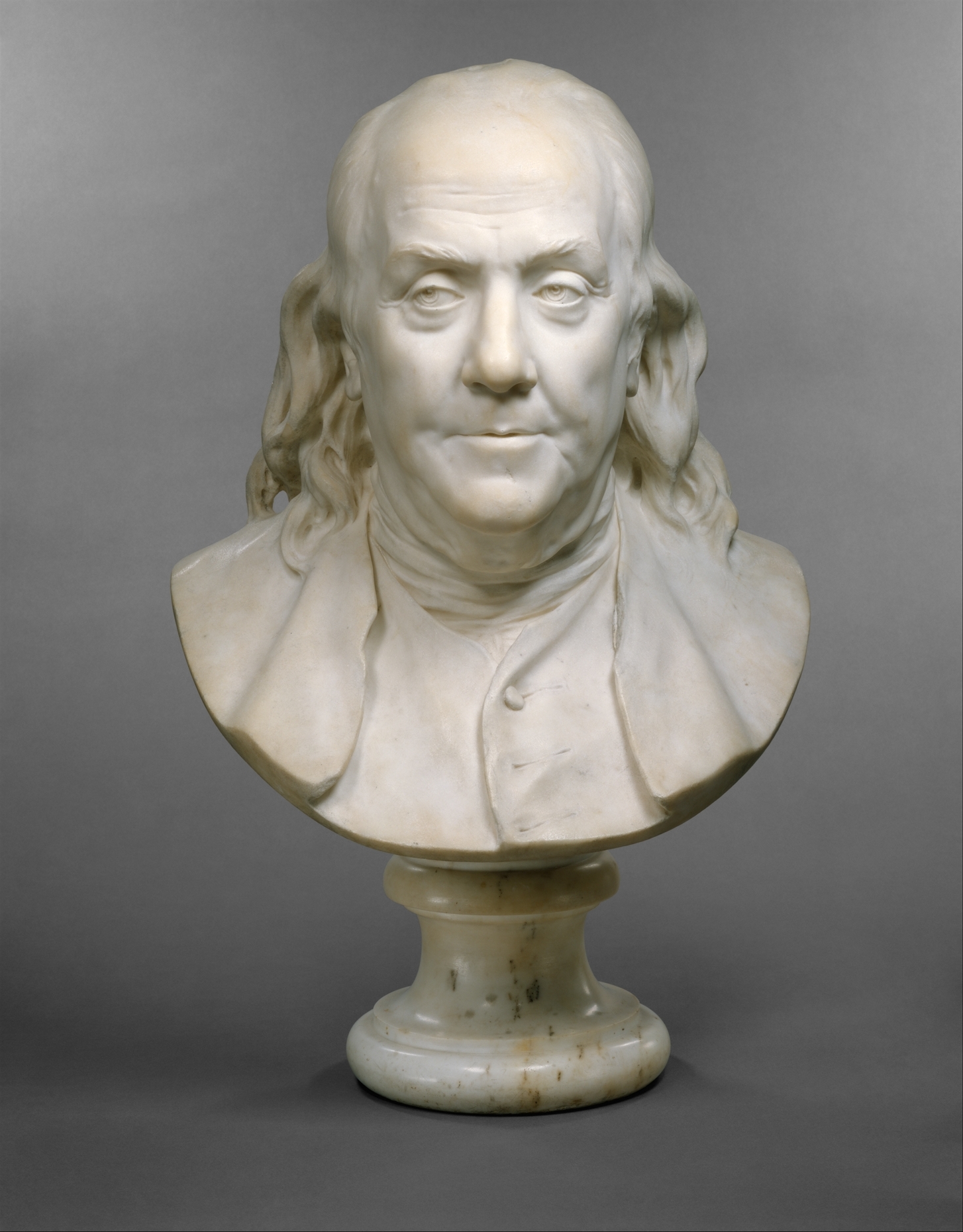

Likeness and image

As the only person to have signed the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

in 1776,

Treaty of Alliance with France in 1778,

Treaty of Paris in 1783, and

U.S. Constitution in 1787, Franklin is considered one of the leading

Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the war for independence from Great Britai ...

. His pervasive influence in the early history of the nation has led to his being jocularly called "the only president of the United States who was never president of the United States".

Franklin's likeness is ubiquitous. Since 1928, it has adorned American

$100 bills. From 1948 to 1963, Franklin's portrait was on the

half-dollar

The term "half dollar" refers to a half-unit of several currencies that are named "dollar". One dollar ( $1) is normally divided into subsidiary currency of 100 cents, so a half dollar is equal to 50 cents. These half dollars (aka 50 cent pieces) ...

. He has appeared on a

$50 bill and on several varieties of the $100 bill from 1914 and 1918. Franklin also appears on the $1,000

Series EE savings bond.

On April 12, 1976, as part of a

bicentennial __NOTOC__

A bicentennial or bicentenary is the two-hundredth anniversary of a part, or the celebrations thereof. It may refer to:

Europe

* French Revolution bicentennial, commemorating the 200th anniversary of 14 July 1789 uprising, celebrated ...

celebration,

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

dedicated a tall marble statue in Philadelphia's

Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

as the

Benjamin Franklin National Memorial

The Benjamin Franklin National Memorial, located in the rotunda of Franklin Institute science museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S., features a colossal statue of a seated Benjamin Franklin, American writer, inventor, statesman, and Founding F ...

. Many of Franklin's personal possessions are on display at the institute. In London, his house at 36 Craven Street, which is the only surviving former residence of Franklin, was first marked with a

blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term ...

and has since been opened to the public as the

Benjamin Franklin House

Benjamin Franklin House is a museum in a terraced Georgian house at 36 Craven Street, London, close to Trafalgar Square. It is the last-standing former residence of Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The hou ...

. In 1998, workmen restoring the building dug up the remains of six children and four adults hidden below the home. A total of 15 bodies have been recovered. The Friends of Benjamin Franklin House (the organization responsible for the restoration) note that the bones were likely placed there by

William Hewson, who lived in the house for two years and who had built a small anatomy school at the back of the house. They note that while Franklin likely knew what Hewson was doing, he probably did not participate in any dissections because he was much more of a physicist than a medical man.

''The Craven Street Gazette''

(PDF

Portable Document Format (PDF), standardized as ISO 32000, is a file format developed by Adobe in 1992 to present documents, including text formatting and images, in a manner independent of application software, hardware, and operating systems. ...

), Newsletter of the Friends of Benjamin Franklin House, Issue 2, Autumn 1998

He has been honored on U.S. postage stamps many times. The image of Franklin, the first postmaster general of the United States, occurs on the face of U.S. postage more than any other notable American save that of George Washington.[Scotts Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps] He appeared on the first U.S. postage stamp issued in 1847. From 1908 through 1923, the U.S. Post Office issued a series of postage stamps commonly referred to as the Washington–Franklin Issues

The Washington–Franklin Issues are a series of definitive stamp, definitive U.S. Postage stamps depicting George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, issued by the U.S. Post Office between 1908 and 1922. The distinctive feature of this issue is th ...