Bastnäsite on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The mineral bastnäsite (or bastnaesite) is one of a family of three

Bastnäsite has

Bastnäsite has  Bastnäsite is closely related to the mineral series

Bastnäsite is closely related to the mineral series

Bastnäsite gets its name from its type locality, the Bastnäs Mine,

Bastnäsite gets its name from its type locality, the Bastnäs Mine,

Bastnäsite ore is typically used to produce rare-earth metals. The following steps and process flow diagram detail the rare-earth-metal extraction process from the ore.McIllree, Roderick. "Kvanefjeld Project – Major Technical Breakthrough". ''ASX Announcements''. Greenland Minerals and Energy LTD, 23 Feb. 2012. Web. 03 Mar. 2014.

# After extraction, bastnasite ore is typically used in this process, with an average of 7% REO (rare-earth oxides).

# The ore goes through

Bastnäsite ore is typically used to produce rare-earth metals. The following steps and process flow diagram detail the rare-earth-metal extraction process from the ore.McIllree, Roderick. "Kvanefjeld Project – Major Technical Breakthrough". ''ASX Announcements''. Greenland Minerals and Energy LTD, 23 Feb. 2012. Web. 03 Mar. 2014.

# After extraction, bastnasite ore is typically used in this process, with an average of 7% REO (rare-earth oxides).

# The ore goes through

carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate g ...

-fluoride

Fluoride (). According to this source, is a possible pronunciation in British English. is an inorganic, monatomic anion of fluorine, with the chemical formula (also written ), whose salts are typically white or colorless. Fluoride salts typ ...

minerals, which includes bastnäsite-( Ce) with a formula of (Ce, La)CO3F, bastnäsite-( La) with a formula of (La, Ce)CO3F, and bastnäsite-( Y) with a formula of (Y, Ce)CO3F. Some of the bastnäsites contain OH− instead of F− and receive the name of hydroxylbastnasite. Most bastnäsite is bastnäsite-(Ce), and cerium

Cerium is a chemical element with the symbol Ce and atomic number 58. Cerium is a soft, ductile, and silvery-white metal that tarnishes when exposed to air. Cerium is the second element in the lanthanide series, and while it often shows the +3 o ...

is by far the most common of the rare earths in this class of minerals. Bastnäsite and the phosphate mineral

Phosphate minerals contain the tetrahedrally coordinated phosphate (PO43−) anion along sometimes with arsenate (AsO43−) and vanadate (VO43−) substitutions, and chloride (Cl−), fluoride (F−), and hydroxide (OH−) anions that also fit i ...

monazite

Monazite is a primarily reddish-brown phosphate mineral that contains rare-earth elements. Due to variability in composition, monazite is considered a group of minerals. The most common species of the group is monazite-(Ce), that is, the cerium- ...

are the two largest sources of cerium and other rare-earth element

The rare-earth elements (REE), also called the rare-earth metals or (in context) rare-earth oxides or sometimes the lanthanides (yttrium and scandium are usually included as rare earths), are a set of 17 nearly-indistinguishable lustrous silve ...

s.

Bastnäsite was first described by the Swedish chemist Wilhelm Hisinger

Wilhelm Hisinger (23 December 1766 – 28 June 1852) was a Swedish physicist and chemist who in 1807, working in coordination with Jöns Jakob Berzelius, noted that in electrolysis any given substance always went to the same pole, and that substan ...

in 1838. It is named for the Bastnäs mine near Riddarhyttan

Riddarhyttan is a locality in Skinnskatteberg Municipality, Västmanland County, Sweden, with 431 inhabitants in 2010. It has an old iron mining tradition, which can be followed back to the last centuries before Christ. The last mine was closed ...

, Västmanland

Västmanland ( or ), is a historical Swedish province, or ''landskap'', in middle Sweden. It borders Södermanland, Närke, Värmland, Dalarna and Uppland.

Västmanland means "(The) Land of the Western Men", where the "western men" (''västerm ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

.

Bastnäsite also occurs as very high-quality specimens at the Zagi Mountains, Pakistan.

Bastnäsite occurs in alkali granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

and syenite

Syenite is a coarse-grained intrusive igneous rock with a general composition similar to that of granite, but deficient in quartz, which, if present at all, occurs in relatively small concentrations (< 5%). Some syenites contain larger proport ...

and in associated pegmatite

A pegmatite is an igneous rock showing a very coarse texture, with large interlocking crystals usually greater in size than and sometimes greater than . Most pegmatites are composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica, having a similar silicic com ...

s. It also occurs in carbonatite

Carbonatite () is a type of intrusive rock, intrusive or extrusive rock, extrusive igneous rock defined by mineralogic composition consisting of greater than 50% carbonate minerals. Carbonatites may be confused with marble and may require geoche ...

s and in associated fenite

Fenite is a metasomatic alteration associated particularly with carbonatite intrusions and created, very rarely, by advanced carbon dioxide alteration (carbonation) of felsic and mafic rocks. It is characterised by the presence of alkali feldspar, ...

s and other metasomatites.

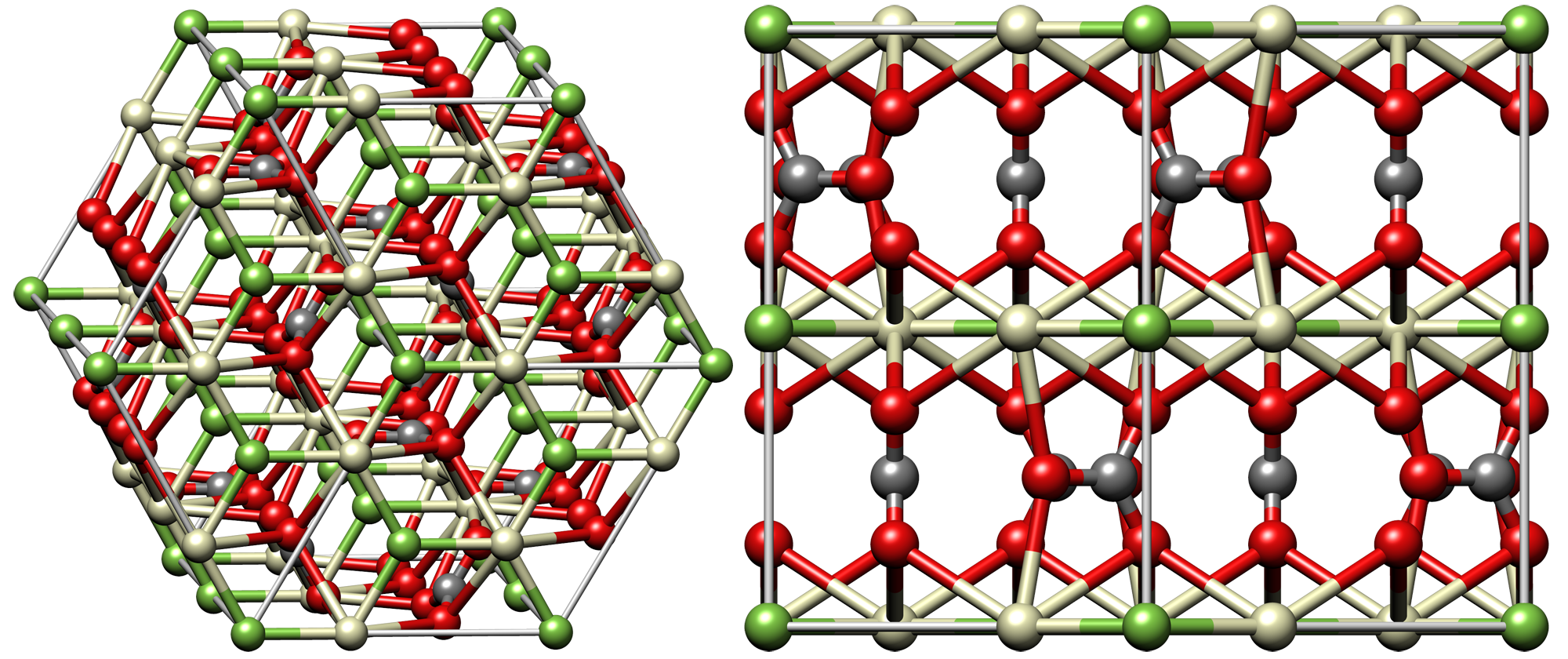

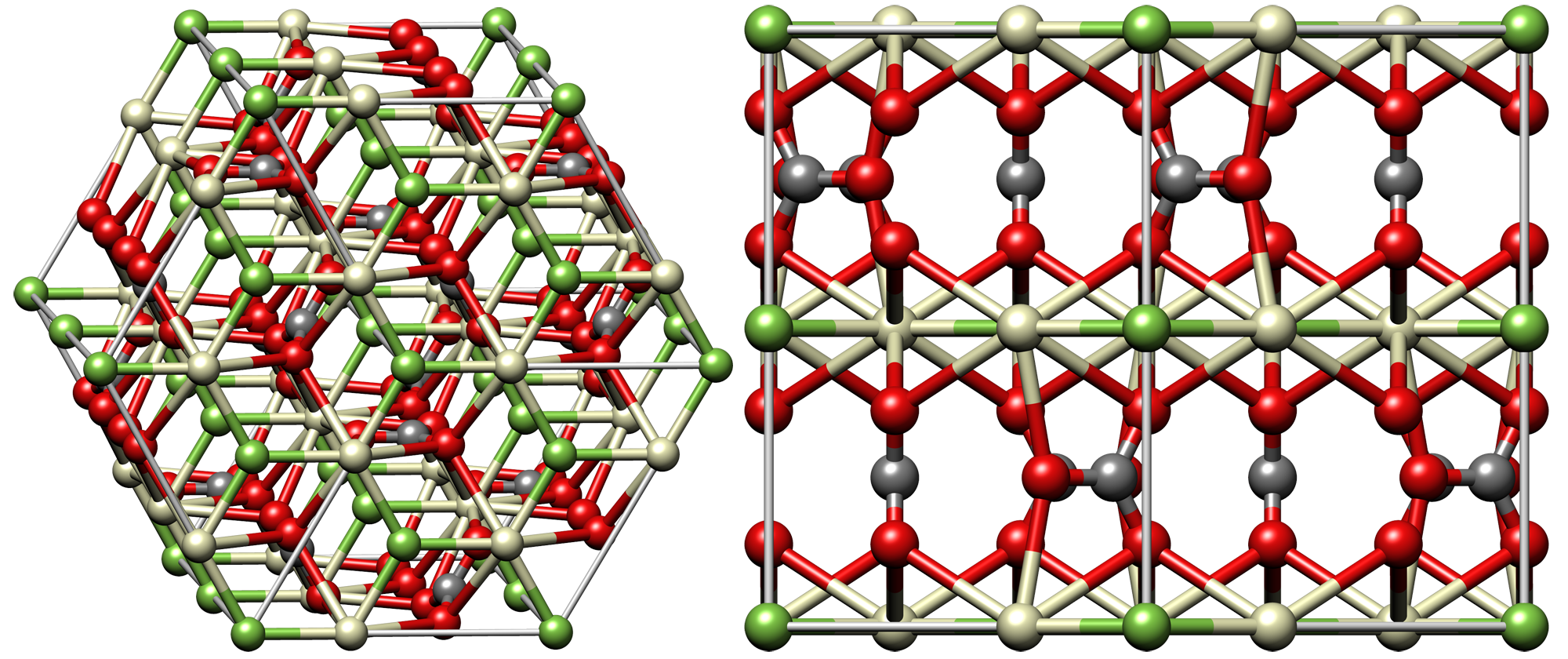

Composition

Bastnäsite has

Bastnäsite has cerium

Cerium is a chemical element with the symbol Ce and atomic number 58. Cerium is a soft, ductile, and silvery-white metal that tarnishes when exposed to air. Cerium is the second element in the lanthanide series, and while it often shows the +3 o ...

, lanthanum

Lanthanum is a chemical element with the symbol La and atomic number 57. It is a soft, ductile, silvery-white metal that tarnishes slowly when exposed to air. It is the eponym of the lanthanide series, a group of 15 similar elements between lantha ...

and yttrium

Yttrium is a chemical element with the symbol Y and atomic number 39. It is a silvery-metallic transition metal chemically similar to the lanthanides and has often been classified as a "rare-earth element". Yttrium is almost always found in com ...

in its generalized formula but officially the mineral is divided into three minerals based on the predominant rare-earth element

The rare-earth elements (REE), also called the rare-earth metals or (in context) rare-earth oxides or sometimes the lanthanides (yttrium and scandium are usually included as rare earths), are a set of 17 nearly-indistinguishable lustrous silve ...

.Beatty, Richard; 2007; Th℮ Lanthanides; Publish℮d by Marshall Cavendish. There is bastnäsite-(Ce) with a more accurate formula of (Ce, La)CO3F. There is also bastnäsite-(La) with a formula of (La, Ce)CO3F. And finally there is bastnäsite-(Y) with a formula of (Y, Ce)CO3F. There is little difference in the three in terms of physical properties and most bastnäsite is bastnäsite-(Ce). Cerium in most natural bastnäsites usually dominates the others. Bastnäsite and the phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

mineral monazite

Monazite is a primarily reddish-brown phosphate mineral that contains rare-earth elements. Due to variability in composition, monazite is considered a group of minerals. The most common species of the group is monazite-(Ce), that is, the cerium- ...

are the two largest sources of cerium, an important industrial metal.

Bastnäsite is closely related to the mineral series

Bastnäsite is closely related to the mineral series parisite

Parisite is a rare mineral consisting of cerium, lanthanum and calcium fluoro-carbonate, . Parisite is mostly parisite-(Ce), but when neodymium is present in the structure the mineral becomes parisite-(Nd).

It is found only as crystals, which bel ...

.Gupta, C. K. (2004) Extractive metallurgy of rare earths, CRC Press . The two are both rare-earth fluorocarbonates, but parisite's formula of contains calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

(and a small amount of neodymium

Neodymium is a chemical element with the symbol Nd and atomic number 60. It is the fourth member of the lanthanide series and is considered to be one of the rare-earth metals. It is a hard, slightly malleable, silvery metal that quickly tarnishes i ...

) and a different ratio of constituent ions. Parisite could be viewed as a formula unit of calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

(CaCO3) added to two formula units of bastnäsite. In fact, the two have been shown to alter back and forth with the addition or loss of CaCO3 in natural environments.

Bastnäsite forms a series with the minerals hydroxylbastnäsite-(Ce) and hydroxylbastnäsite-(Nd). The three are members of a substitution series that involves the possible substitution of fluoride

Fluoride (). According to this source, is a possible pronunciation in British English. is an inorganic, monatomic anion of fluorine, with the chemical formula (also written ), whose salts are typically white or colorless. Fluoride salts typ ...

(F−) ions with hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

(OH−) ions.

Name

Bastnäsite gets its name from its type locality, the Bastnäs Mine,

Bastnäsite gets its name from its type locality, the Bastnäs Mine, Riddarhyttan

Riddarhyttan is a locality in Skinnskatteberg Municipality, Västmanland County, Sweden, with 431 inhabitants in 2010. It has an old iron mining tradition, which can be followed back to the last centuries before Christ. The last mine was closed ...

, Västmanland

Västmanland ( or ), is a historical Swedish province, or ''landskap'', in middle Sweden. It borders Södermanland, Närke, Värmland, Dalarna and Uppland.

Västmanland means "(The) Land of the Western Men", where the "western men" (''västerm ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

. Ore from the Bastnäs Mine led to the discovery of several new minerals and chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

s by Swedish scientists such as Jöns Jakob Berzelius

Jöns is a Swedish given name and a surname.

Notable people with the given name include:

* Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779–1848), Swedish chemist

* Jöns Budde (1435–1495), Franciscan friar from the Brigittine monastery in NaantaliVallis Grati ...

, Wilhelm Hisinger

Wilhelm Hisinger (23 December 1766 – 28 June 1852) was a Swedish physicist and chemist who in 1807, working in coordination with Jöns Jakob Berzelius, noted that in electrolysis any given substance always went to the same pole, and that substan ...

and Carl Gustav Mosander

Carl Gustaf Mosander (10 September 1797 – 15 October 1858) was a Swedish chemist. He discovered the rare earth elements lanthanum, erbium and terbium.

Early life and education

Born in Kalmar, Mosander attended school there until he moved t ...

. Among these are the chemical elements cerium

Cerium is a chemical element with the symbol Ce and atomic number 58. Cerium is a soft, ductile, and silvery-white metal that tarnishes when exposed to air. Cerium is the second element in the lanthanide series, and while it often shows the +3 o ...

, which was described by Hisinger in 1803, and lanthanum

Lanthanum is a chemical element with the symbol La and atomic number 57. It is a soft, ductile, silvery-white metal that tarnishes slowly when exposed to air. It is the eponym of the lanthanide series, a group of 15 similar elements between lantha ...

in 1839. Hisinger, who was also the owner of the Bastnäs mine, chose to name one of the new minerals ''bastnäsit'' when it was first described by him in 1838.

Occurrence

Although a scarce mineral and never in great concentrations, it is one of the more common rare-earth carbonates. Bastnäsite has been found in karstbauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(O ...

deposits in Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

region. Also found in carbonatite

Carbonatite () is a type of intrusive rock, intrusive or extrusive rock, extrusive igneous rock defined by mineralogic composition consisting of greater than 50% carbonate minerals. Carbonatites may be confused with marble and may require geoche ...

s, a rare carbonate igneous intrusive rock, at the Fen Complex The Fen Complex ( no, Fensfeltet) in Nome, Telemark, Norway is a region noted for an unusual suite of igneous rocks. Several varieties of carbonatite are present in the area as well as lamprophyre, ijolite and other highly alkalic rocks. It is the ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

; Bayan Obo

Bayan'obo Mining District, ( Mongolian: ''Bayan Oboɣ-a Aɣurqai-yin toɣoriɣ'', Баян-Овоо Уурхайн тойрог ( mn, italic=yes, "rich" + ovoo); ), or Baiyun-Obo or Baiyun'ebo, is a mining town in the west of Inner Mongolia, ...

, Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

; Kangankunde, Malawi

Malawi (; or aláwi Tumbuka: ''Malaŵi''), officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast ...

; Kizilcaoren, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

and the Mountain Pass rare earth mine

The Mountain Pass Mine, owned by MP Materials, is an open-pit mine of rare-earth elements on the south flank of the Clark Mountain Range in California, southwest of Las Vegas, Nevada. In 2020 the mine supplied 15.8% of the world's rare-earth p ...

in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, US. At Mountain Pass, bastnäsite is the leading ore mineral. Some bastnäsite has been found in the unusual granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

s of the Langesundsfjord area, Norway; Kola Peninsula

sjd, Куэлнэгк нёа̄ррк

, image_name= Kola peninsula.png

, image_caption= Kola Peninsula as a part of Murmansk Oblast

, image_size= 300px

, image_alt=

, map_image= Murmansk in Russia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Murmansk Oblas ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

; Mont Saint-Hilaire

Mont Saint-Hilaire (English: Mount Saint-Hilaire; abe, Wigwômadenizibo; see for other names) is an isolated hill, high, in the Montérégie region of southern Quebec. It is about thirty kilometres east of Montreal, and immediately east of the ...

mines, Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

, and Thor Lake

Thor Lake is a deposit of rare metals located in the Blachford Lake intrusive complex. It is situated 5 km north of the Hearne Channel of Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories, Canada, approximately 100 kilometers east-southeast of the cap ...

deposits, Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. Hydrothermal

Hydrothermal circulation in its most general sense is the circulation of hot water (Ancient Greek ὕδωρ, ''water'',Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with th ...

sources have also been reported.

The formation of hydroxylbastnasite (NdCO3OH) can also occur via the crystallization of a rare-earth bearing amorphous precursor. With increasing temperature, the habit of NdCO3OH crystals changes progressively to more complex spherulitic or dendritic morphologies. The development of these crystal morphologies has been suggested to be controlled by the level at which supersaturation is reached in the aqueous solution during the breakdown of the amorphous precursor. At higher temperature (e.g., 220 °C) and after rapid heating (e.g. < 1 h) the amorphous precursor breaks down rapidly and the fast supersaturation promotes spherulitic growth. At a lower temperature (e.g., 165 °C) and slow heating (100 min

Min or MIN may refer to:

Places

* Fujian, also called Mǐn, a province of China

** Min Kingdom (909–945), a state in Fujian

* Min County, a county of Dingxi, Gansu province, China

* Min River (Fujian)

* Min River (Sichuan)

* Mineola (Am ...

) the supersaturation levels are approached more slowly than required for spherulitic growth, and thus more regular triangular pyramidal shapes form.

Mining history

In 1949, the huge carbonatite-hosted bastnäsite deposit was discovered atMountain Pass

A mountain pass is a navigable route through a mountain range or over a ridge. Since many of the world's mountain ranges have presented formidable barriers to travel, passes have played a key role in trade, war, and both Human migration, human a ...

, San Bernardino County, California

San Bernardino County (), officially the County of San Bernardino, is a County (United States), county located in the Southern California, southern portion of the U.S. state of California, and is located within the Inland Empire area. As of the ...

. This discovery alerted geologists to the existence of a whole new class of rare earth deposit: the rare earth containing carbonatite. Other examples were soon recognized, particularly in Africa and China. The exploitation of this deposit began in the mid-1960s after it had been purchased by Molycorp

Molycorp Inc. was an American mining corporation headquartered in Greenwood Village, Colorado. The corporation, which was formerly traded on the New York Stock Exchange, owned the Mountain Pass rare earth mine in California. It filed for bankrup ...

(Molybdenum Corporation of America). The lanthanide composition of the ore included 0.1% europium oxide, which was needed by the color television industry, to provide the red phosphor, to maximize picture brightness. The composition of the lanthanides was about 49% cerium, 33% lanthanum, 12% neodymium, and 5% praseodymium, with some samarium and gadolinium, or distinctly more lanthanum and less neodymium and heavies as compared to commercial monazite. The europium content was at least double that of a typical monazite. Mountain Pass bastnäsite was the world's major source of lanthanides from the 1960s to the 1980s. Thereafter, China became an increasingly important rare earth supply. Chinese deposits of bastnäsite include several in Sichuan Province

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

, and the massive deposit at Bayan Obo

Bayan'obo Mining District, ( Mongolian: ''Bayan Oboɣ-a Aɣurqai-yin toɣoriɣ'', Баян-Овоо Уурхайн тойрог ( mn, italic=yes, "rich" + ovoo); ), or Baiyun-Obo or Baiyun'ebo, is a mining town in the west of Inner Mongolia, ...

, Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, which had been discovered early in the 20th century, but not exploited until much later. Bayan Obo is currently (2008) providing the majority of the world's lanthanides. Bayan Obo bastnäsite occurs in association with monazite (plus enough magnetite to sustain one of the largest steel mills in China), and unlike carbonatite bastnäsites, is relatively closer to monazite lanthanide compositions, with the exception of its generous 0.2% content of europium.

Ore technology

At Mountain Pass, bastnäsite ore was finely ground, and subjected to flotation to separate the bulk of the bastnäsite from the accompanyingbarite

Baryte, barite or barytes ( or ) is a mineral consisting of barium sulfate ( Ba S O4). Baryte is generally white or colorless, and is the main source of the element barium. The ''baryte group'' consists of baryte, celestine (strontium sulfate), ...

, calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, and dolomite Dolomite may refer to:

*Dolomite (mineral), a carbonate mineral

*Dolomite (rock), also known as dolostone, a sedimentary carbonate rock

*Dolomite, Alabama, United States, an unincorporated community

*Dolomite, California, United States, an unincor ...

. Marketable products include each of the major intermediates of the ore dressing process: flotation concentrate, acid-washed flotation concentrate, calcined acid washed bastnäsite, and finally a cerium concentrate, which was the insoluble residue left after the calcined bastnäsite had been leached with hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbol ...

. The lanthanides that dissolved as a result of the acid treatment were subjected to solvent extraction

A solvent (s) (from the Latin '' solvō'', "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for ...

, to capture the europium

Europium is a chemical element with the symbol Eu and atomic number 63. Europium is the most reactive lanthanide by far, having to be stored under an inert fluid to protect it from atmospheric oxygen or moisture. Europium is also the softest lanth ...

, and purify the other individual components of the ore. A further product included a lanthanide mix, depleted of much of the cerium, and essentially all of samarium and heavier lanthanides. The calcination of bastnäsite had driven off the carbon dioxide content, leaving an oxide-fluoride, in which the cerium content had become oxidized to the less basic quadrivalent state. However, the high temperature of the calcination gave less-reactive oxide, and the use of hydrochloric acid, which can cause reduction of quadrivalent cerium, led to an incomplete separation of cerium and the trivalent lanthanides. By contrast, in China, processing of bastnäsite, after concentration, starts with heating with sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular formu ...

.

Extraction of rare-earth metals

Bastnäsite ore is typically used to produce rare-earth metals. The following steps and process flow diagram detail the rare-earth-metal extraction process from the ore.McIllree, Roderick. "Kvanefjeld Project – Major Technical Breakthrough". ''ASX Announcements''. Greenland Minerals and Energy LTD, 23 Feb. 2012. Web. 03 Mar. 2014.

# After extraction, bastnasite ore is typically used in this process, with an average of 7% REO (rare-earth oxides).

# The ore goes through

Bastnäsite ore is typically used to produce rare-earth metals. The following steps and process flow diagram detail the rare-earth-metal extraction process from the ore.McIllree, Roderick. "Kvanefjeld Project – Major Technical Breakthrough". ''ASX Announcements''. Greenland Minerals and Energy LTD, 23 Feb. 2012. Web. 03 Mar. 2014.

# After extraction, bastnasite ore is typically used in this process, with an average of 7% REO (rare-earth oxides).

# The ore goes through comminution

Comminution is the reduction of solid materials from one average particle size to a smaller average particle size, by crushing, grinding, cutting, vibrating, or other processes. In geology, it occurs naturally during faulting in the upper part of ...

using rod mills, ball mills, or autogenous mills.

# Steam is consistently used to condition the ground ore, along with soda ash fluosilicate, and usually Tail Oil C-30. This is done to coat the various types of rare earth metals with either flocculent, collectors, or modifiers for easier separation in the next step.

# Flotation using the previous chemicals to separate the gangue from the rare-earth metals.

# Concentrate the rare-earth metals and filter out large particles.

# Remove excess water by heating to ~100 °C.

# Add HCl to solution to reduce pH to < 5. This enables certain REM (rare-earth metals) to become soluble (Ce is an example).

# Oxidizing roast further concentrates the solution to approximately 85% REO. This is done at ~100 °C and higher if necessary.

# Enables solution to concentrate further and filters out large particles again.

# Reduction agents (based on area) are used to remove Ce as Ce carbonate or CeO2, typically.

# Solvents are added (solvent type and concentration based on area, availability, and cost) to help separate Eu, Sm, and Gd from La, Nd, and Pr.

# Reduction agents (based on area) are used to oxidize Eu, Sm, and Gd.

# Eu is precipitated and calcified.

# Gd is precipitated as an oxide.

# Sm is precipitated as an oxide.

# Solvent is recycled into step 11. Additional solvent is added based on concentration and purity.

# La separated from Nd, Pr, and SX.

# Nd and Pr separated. SX goes on for recovery and recycle.

# One way to collect La is adding HNO3, creating La(NO3)3. HNO3 typically added at a very high molarity (1–5 M), depending on La concentration and amount.

# Another method is to add HCl to La, creating LaCl3. HCl is added at 1 M to 5 M depending on La concentration.

# Solvent from La, Nd, and Pr separation is recycled to step 11.

# Nd is precipitated as an oxide product.

# Pr is precipitated as an oxide product.

References

Bibliography

*Palache, P.; Berman H.; Frondel, C. (1960). "''Dana's System of Mineralogy, Volume II: Halides, Nitrates, Borates, Carbonates, Sulfates, Phosphates, Arsenates, Tungstates, Molybdates, Etc. (Seventh Edition)"'' John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, pp. 289–291. {{DEFAULTSORT:Bastnasite Lanthanide minerals Carbonate minerals Fluorine minerals Hexagonal minerals Minerals in space group 190