Burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal was an important event in pre-

The burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal was an important event in pre-

The St. Anne's Market building was completely devastated. The fire consumed the parliament's two libraries, parts of the archives of Upper Canada and Lower Canada, as well as more recent public documents. Over 23,000 volumes, forming the collections of the two parliamentary libraries, were lost. Only about 200 books, along with the portrait of Queen Victoria, were saved, thanks to James Curran. Four people, Colonel Wiley, a Scotsman named McGillivray, an employee of the parliament, and the uncle of Todd, who was responsible for the libraries, and

The St. Anne's Market building was completely devastated. The fire consumed the parliament's two libraries, parts of the archives of Upper Canada and Lower Canada, as well as more recent public documents. Over 23,000 volumes, forming the collections of the two parliamentary libraries, were lost. Only about 200 books, along with the portrait of Queen Victoria, were saved, thanks to James Curran. Four people, Colonel Wiley, a Scotsman named McGillivray, an employee of the parliament, and the uncle of Todd, who was responsible for the libraries, and

Four of the speakers of the Champs-de-Mars meeting, James Moir Ferres, editor in chief and principal owner of ''The Montreal Gazette'', William Gordon Mack, lawyer and secretary of the British American League, Hugh E. Montgomerie, trader, Augustus Heward, trader and courtier, as well as Alfred Perry, five persons in total, were arrested and charged with arson early in the morning of April 26 by the

Four of the speakers of the Champs-de-Mars meeting, James Moir Ferres, editor in chief and principal owner of ''The Montreal Gazette'', William Gordon Mack, lawyer and secretary of the British American League, Hugh E. Montgomerie, trader, Augustus Heward, trader and courtier, as well as Alfred Perry, five persons in total, were arrested and charged with arson early in the morning of April 26 by the

Montreal, 1535–1914

Chicago: S. J. Clarke, 1914, volume II. * *

The Earl of Elgin

Londres: Methuen & Co., 1905, pp. 21–88 (Chapter II). * * John Douglas Borthwick

History of the Montreal prison from A.D. 1784 to A.D. 1886: Containing a Complete Record of the Troubles of 1837–1838, Burning of the Parliament Buildings in 1849, the St. Alban's Raiders, 1864, the Two Fenian Raids of 1866 and 1870 […]

Montreal: A. Periard, 1866, pp. 174–183 (Chapter XIV). * Joseph Edmund Collins

Life and Times of the Right Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald

Toronto: Rose Publishing Company, 1883, pp. 114–134 (Chapter VII). *Alexander Mackenzie

The Life and Speeches of Hon. George Brown

Toronto: Globe Printing Company, 1882, pp. 18–21 (Chapter III). *. * William Henry Withrow

A Popular History of the Dominion of Canada

Boston: BB Russell, 1878, pp. 406–412.

Letters and Journals of James, Eighth Earl of Elgin

Londres: John Murray, 1872, pp. 70–99

Google

*James Bruce Elgin and Henry George Grey. ''The Elgin-Grey Papers, 1846–1852'', JO Patenaude, Printer to the King, 1937 * Alfred Perry. "A Reminiscence of '49. Who burnt the Parliament Buildings?", in ''Montreal Daily Star. Carnival Number,'', February 1887 (

Portraits of Five Gentlemen: Who Were Unjustly Imprisoned by an Arbitrary Administration in Consequence of Presuming, at a Public Meeting, to Express Their Disapprobation of that Administration's "Indemnity Act," for Rewarding Traitors, and Putting a Premium on Rebellion

1849.

Hansard's Parliamentary Debates

Volume CVI (June 12 to July 6), London: G. Woodfall & Son, 1849, pp. 189–283.

Rebellion Losses Bill (Hansard)

online

*A Canadian Loyalist. ''The Question Answered, "Did the Ministry Intend to Pay Rebels?": In a Letter to His Excellency the Right Honourable the Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, K. T., Governor General of British North America, &c. &c. &c.'', Montreal: Armour & Ramsay, 1849, 24 p. ttributed to Hugh E. Montgomerie and Alexander Morris in ''A Bibliography of Canadiana'', Dent. ''The Last Forty Years'', vol. 2, p. 143.*Cephas D. Allin and George M. Jones. ''Annexation, Preferential Trade, and Reciprocity; An Outline of the Canadian Annexation Movement of 1849–50, with Special Reference to the Questions of Preferential Trade and Reciprocity'', Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 398 p.

online

Le Parlement brûle !

, Centre d'histoire de Montréal, Ville de Montréal, 11 avril 2006 * Alain Roy. ''Le Marché Sainte-Anne, le Parlement de Montréal et la formation d'un état moderne : un lieu d'échanges, des événements marquants, une époque charnière : étude historique'', Montréal: Direction de Montréal, 93 f. eport presented to the Institut d'histoire de l'Amérique française for the Ministère de la culture et des communications du Québec, Direction de Montréal] *Kirk Johnson, David Widgington. ''Montréal vu de près'', XYZ editeur, 2002, 156 p. ()

preview

*Jean Chartier. "L'année de la Terreur", in ''Le Devoir'', 21 avril 1999

* * * *Jacques Lacoursière, Claude Bouchard et Richard Howard. ''Notre histoire. Québec-Canada. Vers l'autonomie intérieure. 1841–1864'', volume 6, 1965, pp. 507–51

online

*

eproduced in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849''* Alfred Perry. "Un souvenir de 1849 : Qui a brûlé les édifices parlementaires?", in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849'', pp. 105–125 ranslation of "Who burnt the Parliament Buildings?", in ''Montreal Daily Star. Carnival Number,'', February 1887* William Rufus Seaver. "Les confidences du marchand Seaver à son épouse", in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849'', pp. 127–134 ranslation of a letter dated April 25, 1849, transcribed in Josephine Foster. "The Montreal Riot of 1849", ''Canadian Historical Review'', 32, 1 (March 1951), p. 61–65*

Place D'Youville

, in ''Site Web officiel du Vieux-Montréal''. Ville de Montréal, 30 décembre 2005 *Inconnu.

Montréal 1849 : le parlement brûle !

, in ''Les Patriotes de 1837@1838'', 30 avril 2003 *Pierre Turgeon. ''Jour de feu'', Montréal: Flammarion, 1998, 270 p. ()

L'incendie du Parlement à Montréal

, in McCord Museum Web site ainting attributed to Joseph Légaré {{DEFAULTSORT:Burning Of The Parliament Buildings In Montreal History of Montreal 1849 fires in North America 1849 in Canada 1849 in law 1849 riots 1849 crimes in North America Attacks on legislatures

The burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal was an important event in pre-

The burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal was an important event in pre-Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

Canadian history

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians to North America thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Canada were inhabited for millennia by ...

and occurred on the night of April 25, 1849, in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, the then-capital of the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British North America, British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham ...

. It is considered a crucial moment in the development of the Canadian democratic tradition, largely as a consequence of how the matter was dealt with by then co-prime ministers of the united Province of Canada, Sir Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin

Robert Baldwin (May 12, 1804 – December 9, 1858) was an Upper Canada, Upper Canadian lawyer and politician who with his political partner Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine of Lower Canada, led the first responsible government ministry in the Province ...

.

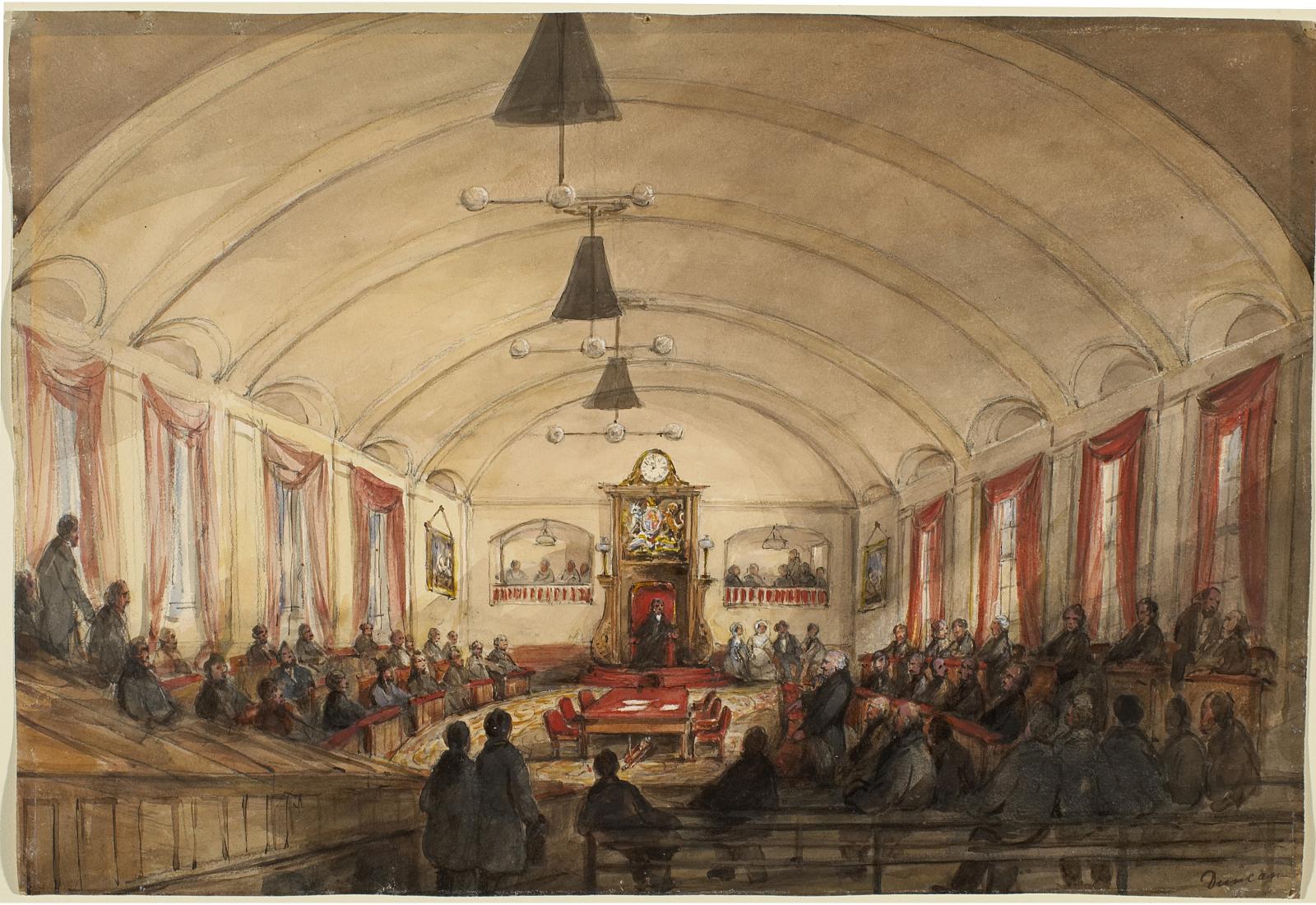

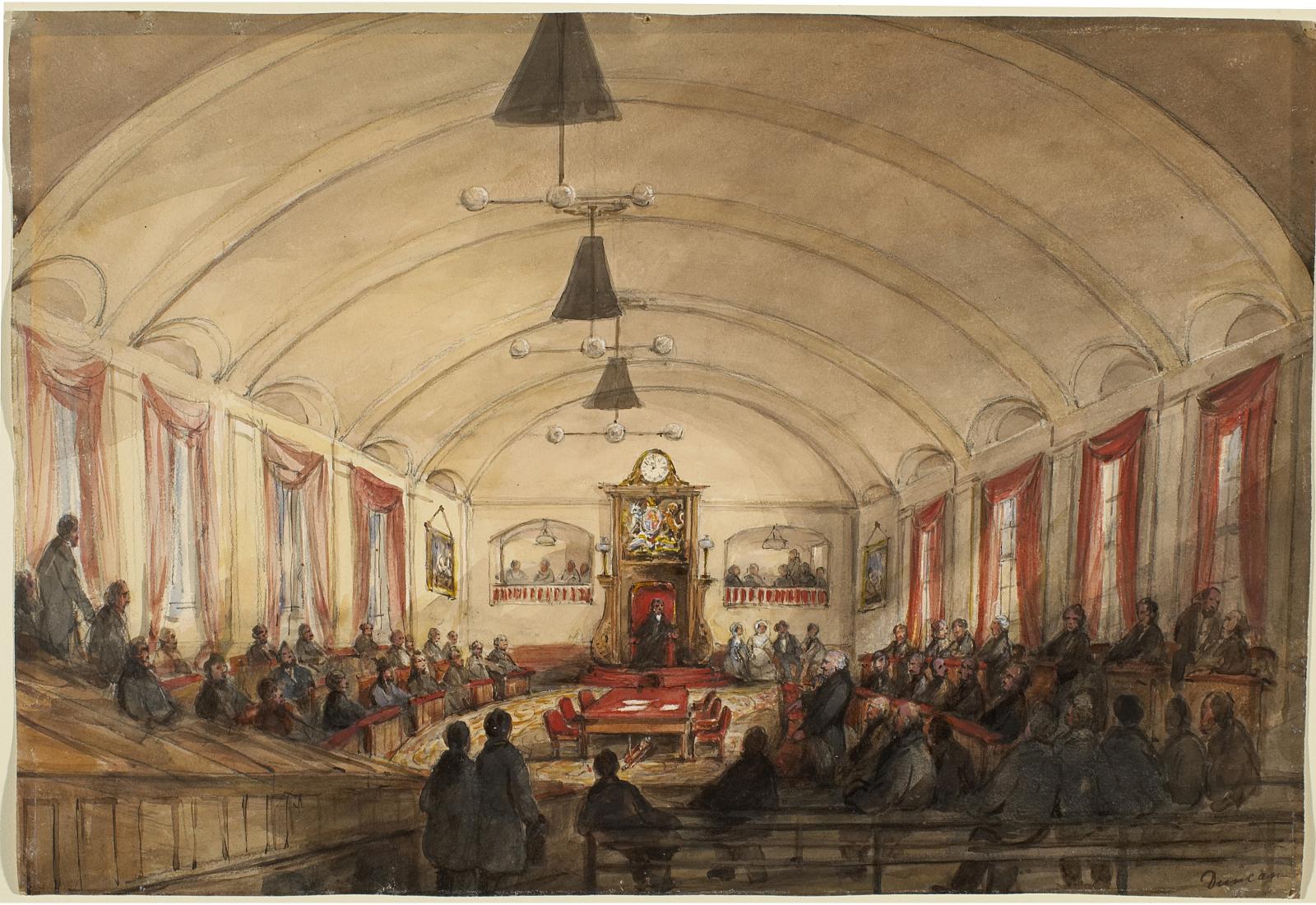

The St. Anne's Market building lodging the Legislative Council and Assembly

Assembly may refer to:

Organisations and meetings

* Deliberative assembly, a gathering of members who use parliamentary procedure for making decisions

* General assembly, an official meeting of the members of an organization or of their representa ...

of Canada was burned down by Tory rioters as a protest against the Rebellion Losses Bill

The Rebellion Losses Bill (full name: ''An Act to provide for the Indemnification of Parties in Lower Canada whose Property was destroyed during the Rebellion in the years 1837 and 1838'') was a controversial law enacted by the legislature of ...

while the members of the Legislative Assembly were sitting in session. There were protests right across British North America. The episode is characterized by divisions in pre-Confederation Canadian society concerning whether Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

was the North American

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Ca ...

appendage of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

or a nascent sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

nation.

In 1837 and 1838 Canada was hit by an economic depression caused partly by unusually bad weather and the banking crisis in the United States and Europe. A number of Canadians in Upper and Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

(now the Canadian provinces

Within the geographical areas of Canada, the ten provinces and three territories are sub-national administrative divisions under the jurisdiction of the Canadian Constitution. In the 1867 Canadian Confederation, three provinces of British North ...

of Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

and Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

respectively) demanded political changes in response to the economic downturn. The Rebellions of 1837

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

occurred first

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

in Lower Canada, then in Upper Canada. After Lord Durham's Report political reforms followed the rebellions.

Many key leaders of the Rebellions would play focal roles in the development of the political and philosophical foundations for an independent Canada, something achieved on July 1, 1867. The Rebellion Losses Bill was intended to both offer amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

to former rebels (permitting them to return to Canada) and an indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one party (the ''indemnitor'') to compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or any other party. The duty to indemni ...

to individuals who had suffered financial losses as a consequence of the rebellions. Lord Durham had granted an amnesty to those involved in the first Rebellion but not to those in the Second Rebellion. Despite an amendment stating that only those that had not pleaded guilty or been found guilty of high treason would receive compensation, the bill was decried as amounting to "paying the rebels" by the opposition. The bill was eventually passed by the majority of those sitting in the Legislative Assembly, but it remained unpopular with most of the population of Canada East and West. Those in Montreal decided to use violence to demonstrate their opposition. It is the only time in the history of the British Empire and Commonwealth that citizens burned down their Parliamentary Buildings in protest. The Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

buildings were destroyed amidst considerable mob violence, and an invaluable collection of historical records kept in the parliamentary library was lost forever.

Despite the tense situation and deplorable socio-cultural crime committed by the mob, Lafontaine proceeded cautiously, fought off armed thugs who had shot through his window, and maintained restraint and resolve in his actions. Jailed members of the mob were released on bail soon after their arrest and a force of special constables established to keep the peace. Though there was public concern this might be a crushing blow to the reform movement, Lafontaine persevered despite the opposition, and would continue in his role developing the tenets of Canadian federalism

Canadian federalism () involves the current nature and historical development of the federal system in Canada.

Canada is a federation with eleven components: the national Government of Canada and ten provincial governments. All eleven go ...

– peace, order, and good government

In many Commonwealth jurisdictions, the phrase "peace, order, and good government" (POGG) is an expression used in law to express the legitimate objects of legislative powers conferred by statute. The phrase appears in many Imperial Acts of ...

. Within a decade public opinion had shifted overwhelmingly in the development of a sovereign Canada.

Parliament moved to Montreal

TheProvince of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British North America, British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham ...

(or United Canada) was born out of the legislative union of the provinces of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

(Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

) and Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

(Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

) in February 1841. In 1844, its capital was moved from Kingston, in Canada West

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

(formerly Upper Canada), to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, in Canada East

Canada East (french: links=no, Canada-Est) was the northeastern portion of the United Province of Canada. Lord Durham's Report investigating the causes of the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions recommended merging those two colonies. The new ...

(formerly Lower Canada). St. Anne's Market, located where Place d'Youville

The Place d'Youville in Old Montreal is a historical square in Montreal, named after Marguerite d'Youville. The roads from the Place Royale (Montreal), Place Royale and McGill Street (Montreal), McGill Street meet at this point. The square is nota ...

stands today, was renovated by architect John Ostell

John Ostell (7 August 1813 – 6 April 1892) architect, surveyor and manufacturer, was born in London, England and emigrated to Canada in 1834, where he apprenticed himself to a Montreal surveyor André Trudeau to learn French methods of surve ...

to host the provincial parliament. As part of the moving of the capital, all books in the two parliamentary libraries, as well as those of the Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council were transported by boat on the St. Lawrence

Saint Lawrence or Laurence ( la, Laurentius, lit. " laurelled"; 31 December AD 225 – 10 August 258) was one of the seven deacons of the city of Rome under Pope Sixtus II who were martyred in the persecution of the Christians that the Roma ...

.

General elections were held in October 1844. The Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

party won a majority and Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Metcalfe had its principal spokesmen enter the Executive Council. The first session of the second parliament opened on November 28 of the same year.

Economic crisis

In 1843, theParliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

passed the ''Canadian Corn Act'', which favoured Canada's exports of wheat and flour on the UK markets through the reduction of duties. The protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

policy of Lord Stanley

Earl of Derby ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl forfeited his property toward the en ...

and Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

, in continuity with Great Britain's colonial practice during the first half of the 19th century, was overturned in 1846, by the repeal of the ''Corn Laws'' and the promotion of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

by the government of Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

.

Canada's chambers of commerce feared an imminent disaster. The ''Anti-Corn Law League

The Anti-Corn Law League was a successful political movement in Great Britain aimed at the abolition of the unpopular Corn Laws, which protected landowners’ interests by levying taxes on imported wheat, thus raising the price of bread at a time ...

'' was triumphant, but the commercial class and ruling class of Canada, principally English-speaking and conservative, experienced an important setback. The repercussions of the repeal were felt as early as 1847. The Canadian government put pressure on Colonial Secretary Earl Grey

Earl Grey is a title in the peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1806 for General Charles Grey, 1st Baron Grey. In 1801, he was given the title Baron Grey of Howick in the County of Northumberland, and in 1806 he was created Viscou ...

to have Great Britain negotiate a lowering of the duties imposed on Canadian products entering the United States market, which had become the only lucrative path to export. A reciprocity treaty was ultimately negotiated, but only eight years later in 1854. During the interval, Canada experienced an important political crisis and influential members of society openly discussed three alternatives to the political status quo: annexation to the United States, the federation of the colonies and territories of British North America, and the independence of Canada. Two citizens' associations appeared in the wake of the crisis: the Annexation Association

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

and the British American League

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

.

After 1847, the fears of the chambers of commerce in Canada were confirmed, and bankruptcies kept accumulating. Property values were in freefall in the cities, particularly in the capital. In February 1849, the introduction in Parliament of an indemnity bill only aggravated the discontent of a part of the population who had watched the passing of a series of legislative measures by the reformist majority, which took power in beginning of 1848, about a year before.

Rebellion Losses Bill

In 1845, theDraper

Draper was originally a term for a retailer or wholesaler of cloth that was mainly for clothing. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher.

History

Drapers were an important trade guild during the medieval period ...

-Viger Viger may refer to:

People

There are a number of prominent Canadians with the surname Viger. This includes:

* Amanda Viger (1845–1909), nun, pharmacist and hospital founder

* André Viger (1952–2006), wheelchair marathoner and Paralympic

* Bo ...

government set up, on November 24, a commission of inquiry into the claims the inhabitants of Lower Canada had sent since 1838, to determine those that were justified and provide an estimate of the amount to be paid. The five commissioners, Joseph Dionne

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, P. H. Moore, Jacques Viger, John Simpson and Joseph-Ubalde Beaudry, submitted their first report in April 1846. They received instructions from the government to distinguish between claims made by persons participating in the rebellion and those who had given no support to the insurrectionist party. The total of the claims considered receivable amounted to £241,965, 10 s. and 5d., but the commissioners were of opinion that following a more thorough enquiry into the claims they were unable to make, the amount to be paid by the government would likely not go beyond £100,000. The Assembly passed a motion on June 9, 1846 authorizing a compensation of £9,986 for claims studied prior to the presentation of the report. Nothing further was accomplished on this question until the dissolution of parliament on December 6, 1847.

The general election of January 1848 changed the composition of the House of Assembly in favour of the opposition party, the moderate reformists led by Robert Baldwin

Robert Baldwin (May 12, 1804 – December 9, 1858) was an Upper Canada, Upper Canadian lawyer and politician who with his political partner Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine of Lower Canada, led the first responsible government ministry in the Province ...

and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine

Sir Louis-Hippolyte Ménard '' dit'' La Fontaine, 1st Baronet, KCMG (October 4, 1807 – February 26, 1864) was a Canadian politician who served as the first Premier of the United Province of Canada and the first head of a responsible governmen ...

. The new governor, Lord Elgin

Earl of Elgin is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in 1633 for Thomas Bruce, 3rd Lord Kinloss. He was later created Baron Bruce, of Whorlton in the County of York, in the Peerage of England on 30 July 1641. The Earl of Elgin is the h ...

, who arrived in the colony on January 30, first formed a government that did not have the support of the majority of the members in the House. These withdrew their support of the Executive by a vote of no-confidence on March 3. On March 7, Governor Elgin called in Baldwin and Lafontaine, respectively leaders of the majority parties in both sections of the united province, to the Executive Council. On March 11, eleven new ministers entered the council.

On January 29, 1849, Lafontaine moved to form a committee of the whole House on February 9 to "take into consideration the necessity of establishing the amount of Losses incurred by certain inhabitants in Lower Canada during the political troubles of 1837 and 1838, and of providing for the payment thereof". The consideration of this motion was pushed ahead on several occasions. The opposition party, which denounced the desire of the government to "pay the rebels", showed itself reluctant to begin the study of the question which was on hold since 1838. Its members proposed various amendments to Lafontaine's motion: a first, on February 13, to report the vote by ten days "to give time for the expression of the feelings of the country"; a second one, on February 20, declaring that the House had "no authority to entertain any such proposition" since the Governor General had not recommended that the House "make provision for liquidating the claims for Losses incurred by the Rebellions in Lower Canada, during the present session". The amendments were rejected and the committee was eventually formed on Tuesday, February 20, but the House was adjourned.

The debates that took place between February 13 and 20 were particularly intense and, in the House, the verbal violence of the representatives soon yielded to physical violence. Tory MPP

MPP or M.P.P. may refer to:

* Marginal physical product

* Master of Public Policy, an academic degree

* Member of Provincial Parliament (Ontario), Canada

* Member of Provincial Parliament (Western Cape), South Africa

* ''Merriweather Post Pavilion ...

s Henry Sherwood

Henry Sherwood, (1807 – July 7, 1855) was a lawyer and Tory politician in the Province of Canada. He was involved in provincial and municipal politics. Born into a Loyalist family in Brockville in Augusta Township, Upper Canada, he stud ...

, Allan MacNab

Sir Allan Napier MacNab, 1st Baronet (19 February 1798 – 8 August 1862) was a Canadian political leader who served as joint Premier of the Province of Canada from 1854 to 1856.

Early life

He was born in Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) to All ...

and Prince attacked the legitimacy of the proposed measure, stating that it rewarded the "rebels" of yesterday and constituted an insult to the "loyal" subjects who had fought against them in 1837 and 1838. On February 15, executive councillors Francis Hincks

Sir Francis Hincks, (December 14, 1807 – August 18, 1885) was a Canadian businessman, politician, and British colonial administrator. An immigrant from Ireland, he was the Co-Premier of the Province of Canada (1851–1854), Governor of Barb ...

and William Hume Blake

William Hume Blake, (10 March 1809 – 15 November 1870) was an Irish-Canadian jurist and politician. He was the father of Edward Blake, an Ontario Premier and federal Liberal party of Canada leader, and the first Chancellor of Upper Canada.

H ...

retorted in the same tone and Blake even went as far as claiming the Tories to be the true rebels, because, he said, it was they who had violated the principles of the British constitution and caused the civil war of 1837–38. Mr. Blake refused to apologize after his speech, and a mêlée burst out among the spectators standing on the galleries. The speaker of the House had them expelled and a confrontation between MacNab and Blake was avoided by the intervention of the Sergeant at Arms.

The English-language press of the capital (''The Gazette

The Gazette (stylized as the GazettE), formerly known as , is a Japanese visual kei Rock music, rock band, formed in Kanagawa Prefecture, Kanagawa in early 2002.''Shoxx'' Vol 106 June 2007 pg 40-45 The band is currently signed to Sony Music Recor ...

'', ''Courier

A courier is a person or organisation that delivers a message, package or letter from one place or person to another place or person. Typically, a courier provides their courier service on a commercial contract basis; however, some couriers are ...

'', ''Herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen to ...

'', '' Transcript'', ''Witness'', ''Punch'') participated in the movement of opposition to the indemnification measure. A single daily, the ''Pilot'', owned by cabinet member Francis Hinks, supported the government. In the French-language press (''La Minerve

''La Minerve'' (French for "The Minerva") was a newspaper founded in Montreal, Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) by Augustin-Norbert Morin to promote the political goals of Louis-Joseph Papineau's Parti patriote. It was notably directed by Ludge ...

'', ''L'Avenir''), the measure was unanimously supported.

On February 17, the leading Tory MPPs held a public meeting to protest against the measure. George Moffatt George Moffat or Moffatt may refer to:

* George Moffat Sr. (1810–1878), New Brunswick businessman and Conservative politician

* George Moffat Jr. (1848–1918), son of the above, also a New Brunswick businessman and Conservative politician

* G ...

was elected chairman and various public men such as Allan MacNab, Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

, Gugy, Macdonald, Molson

The Molson Brewery is a Canadian based brewery company based in Montreal which was established in 1786 by the Molson family. In 2005, Molson merged with the Adolph Coors Company to become Molson Coors.

Molson Coors maintains some of its Can ...

, Rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

and others gave speeches. The meeting prepared a petition to the governor asking him to dissolve the parliament and call new elections, or to reserve the assent of the bill for the Queen's pleasure, that is to say, to defer the question to the UK Parliament. The press reported that Lafontaine was burned in effigy that night.

On February 22, Henry John Boulton

Henry John Boulton, (1790 – June 18, 1870) was a lawyer and political figure in Upper Canada and the Province of Canada, as well as Chief Justice of Newfoundland.

Boulton began his legal career under the tutelage of John Beverly Robin ...

, MPP for Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

, introduced an amendment that all persons having pleaded guilty or having been found to be guilty of high treason should not receive compensation from the government. The government party supported the amendment, but the gesture had no effect on the opposition, which persisted in denouncing the measure as amounting to "paying the rebels". Certain liberal MPPs, including Louis-Joseph Papineau and Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau, opposed the amendment because, according to them, it resulted in the recognition, by the government, of the legality of the military court created by former acting governor John Colborne in order to speedily execute the prisoners of 1839.

On March 9, the Legislative Assembly passed the bill by a vote of 47 to 18. MPPs from the former Upper Canada voted in favour, 17 to 14, while those of the former Lower Canada voted 30 to 4 in favour. Six days later, the Legislative Council approved the project 20 to 14. The project having passed both Houses of the Provincial Parliament, the next step was the assent of Governor Elgin, which came 41 days later, on April 25, 1849.

On March 22, a crowd paraded in the streets of Toronto with effigies of William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify elite members of Upper Canada. He represented Yor ...

, Robert Baldwin, and William Hume Blake. When the group neared Baldwin's residence, and in front of that of a Mr. McIntosh on Yonge Street, where Mackenzie was residing after his return from exile, they set the effigies on fire and threw rocks through the windows of Mr. McIntosh's house.<

Mob attacks parliament

On April 25, the cabinet sent Francis Hinks toThe Monklands

Villa Maria is a subsidized private Catholic co-educational high school in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It was founded in 1854 and offers both a francophone and an anglophone stream.

There are roughly 950 students in the French sector and 800 s ...

, the governor's residence, to request that Governor Elgin quickly come to town in order to assent a new tariff bill. The first European ship of the year had already arrived in the Port of Quebec

The Port of Quebec (french: Port de Québec) is an inland port located in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It is the oldest port in Canada, and the second largest in Quebec after the Port of Montreal.

History

In the 19th century, the Port of Quebec ...

and the new law needed to be in force in order to tax its merchandise. The governor left his residence and went to the Parliament the same day.

At about 5:00 pm, the governor gave the royal assent to the bill in the Legislative Council room, in the presence of members of both houses of Parliament. Since he was already in town, the governor decided to also give assent to some forty one other bills passed by the houses and awaiting to be assented. Among those bills was the ''Rebellion Losses Bill''. The assent of this law seemed to take some people by surprise, and the galleries where some visitors were standing became agitated.

When the governor exited the building at around 6:00 pm, he found a crowd of protesters blocking his path. Some of the protesters began throwing eggs and rocks at him and his aides and he was forced to climb back into his carriage in haste and return to Monklands at gallop speed, while some of his assailants pursued him in the streets.

Not long after the attacks on the governor, alarm bells sounded throughout town to alert the population. A horse-drawn carriage traveled through the streets to announce a public meeting to denounce the governor's assent to the ''Rebellion Losses Bill''. The editor in chief

An editor-in-chief (EIC), also known as lead editor or chief editor, is a publication's editorial leader who has final responsibility for its operations and policies.

The highest-ranking editor of a publication may also be titled editor, managing ...

of ''The Gazette

The Gazette (stylized as the GazettE), formerly known as , is a Japanese visual kei Rock music, rock band, formed in Kanagawa Prefecture, Kanagawa in early 2002.''Shoxx'' Vol 106 June 2007 pg 40-45 The band is currently signed to Sony Music Recor ...

'', James Moir Ferres

James Moir Ferres (1813 – April 21, 1870) was a journalist and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1813 and studied at Marischal College in Aberdeen. Ferres came to Montreal in 1833 and taught at Edward Bl ...

, published an ''Extra'' which contained a report of the incident involving Lord Elgin, and invited the "Anglo-Saxons" of Montreal to attend a mass meeting to be held at 8:00 pm on Place d'Armes

Place may refer to:

Geography

* Place (United States Census Bureau), defined as any concentration of population

** Census-designated place, a populated area lacking its own municipal government

* "Place", a type of street or road name

** Often ...

. The ''Extra'' read:

Between 1,200 and 1,500 were reported to have attended the meeting (which in the end took place on Champ-de-Mars

The Champ de Mars (; en, Field of Mars) is a large public greenspace in Paris, France, located in the seventh ''arrondissement'', between the Eiffel Tower to the northwest and the École Militaire to the southeast. The park is named after the ...

) to hear, by the gleam of torch light, the speeches of orators protesting vigorously against Lord Elgin's assent to the bill. Among the speakers were George Moffat, Colonel Gugy and other members of the official opposition. During the meeting it was proposed to address a petition to Her Majesty asking her to recall governor Elgin and disavow the indemnification act. In the 1887 account he gave of his participation to the events, some 38 years later, Alfred Perry, the captain of a volunteer corps of firemen, asserted that on that night he stepped on the hustings to speak to the crowd, put his hat on the torch lighting the petition, and exclaimed: "The time for petitions is over, but if the men who are present here are serious, let them follow me to the Parliament Buildings."

The crowd then followed him to the Parliament Buildings. Along the way, they broke the windows of the offices of the '' Montreal Pilot'', which was the only English-language daily supporting the administration at that time.

When they arrived on site, the rioters broke the windows of the House of Assembly, which was still in session despite the late hour. A committee of the whole House was at that time debating a ''Bill to Establish a Court having jurisdiction in Appeals and Criminal matters for Lower Canada''. The last entry in the journal of the House on April 25 reads:

After breaking the windows and the gas lamps on the outside, a group entered the building and committed various acts of vandalism. According to Perry's account, he, together with Augustus Howard and Alexander Courtney

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, broke into the building after a first unsuccessful attempt to open the locked doors. Someone ordered a fire truck brought over, and then Perry and a notary, John H. Isaacson, used the truck's ladder as a battering ram

A battering ram is a siege engine that originated in ancient history, ancient times and was designed to break open the masonry walls of fortifications or splinter their wooden gates. In its simplest form, a battering ram is just a large, hea ...

to break down the doors. He entered with a few followers and reached the House of Assembly. A certain O'Connor attempted to block their entry, but Perry knocked him down with the handle of the axe he was carrying. The mob took control of the room despite the resistance of a few MPPs (John Sandfield Macdonald

John Sandfield Macdonald, (December 12, 1812 – June 1, 1872) was the joint premier of the Province of Canada from 1862 to 1864. He was also the first premier of Ontario from 1867 to 1871, one of the four founding provinces created at Conf ...

, William Hume Blake, Thomas Aylwin, John Price) and sergeant at arms Chrisholm.

One of the rioters sat in the Speaker's chair where Morin had been sitting only a few minutes before, and declared the dissolution of the House. The room was turned upside down while other men entered the room of the Legislative Council. The acts of vandalism that were reported included the destruction of the seats and desks, stamping on the portrait of Louis-Joseph Papineau, that had been hanging on the wall next to that of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

. Perry claimed to have accidentally set fire to the room himself when he hit the gas chandelier suspended on the ceiling with a brick, aiming for the clock that was directly above the Speaker's chair. The clock, whose ticking apparently got on his nerves, was, according to his account, showing 9:40 pm when it happened. Other sources, including newspapers of the time, believed the fire to have been started when rioters outside the building started throwing the torches that some of them had carried from the Champ-de-Mars meeting.

Since gas pipes were broken both inside and outside the building, the fire spread rapidly. Perry and Courtney ran out of the building with the ceremonial mace

A ceremonial mace is a highly ornamented staff of metal or wood, carried before a sovereign or other high officials in civic ceremonies by a mace-bearer, intended to represent the official's authority. The mace, as used today, derives from the or ...

of the House of Assembly which was lying on the clerk's desk in front of the Speaker's chair. The mace was afterwards brought to Allan MacNab who was then at Donegana Hotel.

The St. Anne's Market building burned very rapidly, with the fire propagating to adjacent buildings, including a house, some warehouses, and the general hospital of the Grey Nuns

The Sisters of Charity of Montreal, formerly called The Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal and more commonly known as the Grey Nuns of Montreal, is a Canadian religious institute of Roman Catholic religious sisters, founde ...

. The mob did not allow firefighters to fight the flames devastating the parliament buildings, but did not intervene against those who were trying to save the other structures.

Damages

The St. Anne's Market building was completely devastated. The fire consumed the parliament's two libraries, parts of the archives of Upper Canada and Lower Canada, as well as more recent public documents. Over 23,000 volumes, forming the collections of the two parliamentary libraries, were lost. Only about 200 books, along with the portrait of Queen Victoria, were saved, thanks to James Curran. Four people, Colonel Wiley, a Scotsman named McGillivray, an employee of the parliament, and the uncle of Todd, who was responsible for the libraries, and

The St. Anne's Market building was completely devastated. The fire consumed the parliament's two libraries, parts of the archives of Upper Canada and Lower Canada, as well as more recent public documents. Over 23,000 volumes, forming the collections of the two parliamentary libraries, were lost. Only about 200 books, along with the portrait of Queen Victoria, were saved, thanks to James Curran. Four people, Colonel Wiley, a Scotsman named McGillivray, an employee of the parliament, and the uncle of Todd, who was responsible for the libraries, and Sandford Fleming

Sir Sandford Fleming (January 7, 1827 – July 22, 1915) was a Scottish Canadian engineer and inventor. Born and raised in Scotland, he emigrated to colonial Canada at the age of 18. He promoted worldwide standard time zones, a prime meridian, ...

, who later became a renowned engineer, saved the portrait of Queen Victoria hanging in the hall leading to the lower house. The canvas of the painting without the frame was transported to the Donegana Hotel. The market buildings and all it contained were insured for £12,000; the insurers refused to pay because of the criminal origin of the fire.

The two libraries and the public archives had been kept in the Parliament buildings since 1845. At the beginning of the session of 1849, the library of the Legislative Assembly counted more than 14,000 volumes and that of the Legislative Council more than 8,000. The collections were those of the libraries of the old provincial parliaments of Lower Canada and Upper Canada, which were merged into a single parliament through the ''Act of Union'' in 1840. The parliament house of the province of Upper Canada, founded in 1791 and seated in York, had been burned down by the American army during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. The parliament remained itinerant between 1814 and 1829, and a permanent building did not re-open before 1832. Consequently, its libraries were not considerable and only provided a few hundreds of books to the new united legislature. Most of the books came from the Parliament of Lower Canada's libraries, particularly that of the Legislative Assembly, which comprised many thousands of books and was opened to the public in 1825. The losses were estimated at over .Le Canada sous l'Union, 1841–1867, p. 112.

Looking to rebuild the parliamentary library, the government sent bibliographer Georges-Barthélemi Faribault to Europe, where he spent £4,400 purchasing volumes in Paris and London. About two years after its partial reconstruction, the library of the Parliament of United Canada was lost again to a fire, on February 1, 1854. This time, the flames destroyed half the 17,000 volumes of the library, which had been in the new Parliament Buildings of Quebec City since 1853.

The parliamentary agenda was obviously affected by the events of April 25. The day after the fire, a special meeting of the members of the Legislative Assembly was convened to meet at 10:00 am in the hall of the Bonsecours Market

Bonsecours Market (french: Marché Bonsecours), at 350 rue Saint-Paul in Old Montreal, is a two-story domed public market. For more than 100 years, it was the main public market in the Montreal area. It also briefly accommodated the Parliament of ...

, under the protection of British soldiers. On that day, the MPPs accomplished nothing other than appointing a committee responsible to report on the bills that were destroyed. Their report was presented to the House a week later on May 2. Lafontaine was not present that morning, because he assisted to the wedding of lawyer Amable Berthelot

Amable Berthelot (February 10, 1777 – November 24, 1847) was a ''Canadien'' lawyer, author and political figure. He was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada and later to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. ...

, his associate in law, who was marrying the adoptive daughter of judge Elzéar Bédard

Elzéar Bédard (24 July 1799 – 11 August 1849) was a lawyer and a member of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada. He later became a judge.

He was born at Quebec City in 1799, the son of Pierre-Stanislas Bédard. Bédard received a typica ...

. The Legislative Assembly kept meeting at Bonsecours Market until May 7, after which date the parliament was convened in a building owned by Moses Judas Hayes on Place Dalhousie.

The Legislative Council's first meeting after the fire was held in the sacristy

A sacristy, also known as a vestry or preparation room, is a room in Christian churches for the keeping of vestments (such as the alb and chasuble) and other church furnishings, sacred vessels, and parish records.

The sacristy is usually located ...

of the Trinity Church on April 30.

First series of arrests

Four of the speakers of the Champs-de-Mars meeting, James Moir Ferres, editor in chief and principal owner of ''The Montreal Gazette'', William Gordon Mack, lawyer and secretary of the British American League, Hugh E. Montgomerie, trader, Augustus Heward, trader and courtier, as well as Alfred Perry, five persons in total, were arrested and charged with arson early in the morning of April 26 by the

Four of the speakers of the Champs-de-Mars meeting, James Moir Ferres, editor in chief and principal owner of ''The Montreal Gazette'', William Gordon Mack, lawyer and secretary of the British American League, Hugh E. Montgomerie, trader, Augustus Heward, trader and courtier, as well as Alfred Perry, five persons in total, were arrested and charged with arson early in the morning of April 26 by the police superintendent

Superintendent (Supt) is a rank in the British police and in most English-speaking Commonwealth nations. In many Commonwealth countries, the full version is superintendent of police (SP). The rank is also used in most British Overseas Territories ...

William Ermatinger

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

. A crowd gathered around the police station at the Bonsecours Market in protest. Perry, who was arrested last, was transferred to the prison of the faubourg de Québec at 12:00 pm, escorted by a company of soldiers, and pursued by the crowd. Once in prison, he was put in the same cell with the other four.

Lafontaine, exercising his role as Attorney General, advised Ermatinger to release the prisoners. On Saturday April 28, they were released on bail. A procession of omnibuses and cabs transported them in triumph from the prison to the front door of the Bank of Montreal

The Bank of Montreal (BMO; french: Banque de Montréal, link=no) is a Canadian multinational investment bank and financial services company.

The bank was founded in Montreal, Quebec, in 1817 as Montreal Bank; while its head office remains in ...

, on Place d'Armes, where they addressed their partisans and thanked them for their support.

Continuation of violence until May

On the night of April 26, a group of men vandalized the residences of reformist MPPs Hinks, Wilson and Benjamin Holmes at Beaver Hall. The men then proceeded to the house of Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, on rue de l'Aqueduc in the faubourg Saint-Antoine, vandalizing it and setting his stable on fire. The fire propagated to his house, however no one was inside at the time. The fire was extinguished by a detachment of soldiers, but not before it had caused significant damage to Lafontaine's private library. Returning toward downtown Montreal, the men broke windows on the boarding house where Baldwin and Price resided as well as those of McNamee's Inn, two buildings forming the corner of the Catholic Cemetery street. They also attacked the residences of Solicitor General Mr. Drummond on Craig street and that of Dr.Wolfred Nelson

Wolfred Nelson (10 July 1791 – 17 June 1863) was the mayor of Montreal, Quebec, from 1854 to 1856.

Biography

Nelson was born in Montreal. His father, William Nelson, was an immigrant to Colonial America from Newsham, North Yorkshire, En ...

, at the corner of Saint-Laurent and Petite Saint-Jacques.

A group of Tory leaders including George Moffatt and Gugy convened a new public meeting of the "Friends of Peace" on Champ-de-Mars on Friday April 27 at 12:00 pm. There they tried to calm their followers down and proposed the resumption of peaceable means to resolve the crisis. It was resolved to submit a petition praying the Queen to relieve Elgin from office and disavow the ''Rebellion Losses Act''.

Confronted with riots threatening the lives of citizens and damaging their properties, the government took the decision to raise a special police force. On the morning of April 27, the authorities informed the population that men who would show up at 6:00 pm in front of the dépôt de l'ordonnance on rue du Bord-de-l'Eau would receive arms. Some 800 men, principally Canadians from Montreal and its suburbs and some Irish immigrants of Griffintown

Griffintown is a historic neighbourhood of Montreal, Quebec, southwest of downtown. The area existed as a functional neighbourhood from the 1820s until the 1960s, and was mainly populated by Irish immigrants and their descendants. Mostly depopulate ...

, presented themselves and between 500 and 600 constables were armed and barracked near the Bonsecours Market. During the arms distribution, a group of men showed up and attacked the new constables by firing on them and throwing rocks at them. The newly armed men fought back and wounded three of their assailants.

During a public meeting on Place du Castor on that night, general Charles Stephen Gore

General Sir Charles Stephen Gore (26 December 1793 – 4 September 1869), also styled as the Honorable Charles Gore, was a British general.

Early life

Gore was a son of Arthur Gore, 2nd Earl of Arran and, his third wife, the former Elizabet ...

stepped on the hustings and dispersed the crowd by swearing on his honour that the new constables would be disarmed by morning. This is indeed what occurred, as the new force supposed to act under the orders of Montreal's justices of the peace was demobilized less than 24 hours after being armed.

A part of the 71st (Highland) Regiment of Foot

The 71st Regiment of Foot was a Highland regiment in the British Army, raised in 1777. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 74th (Highland) Regiment of Foot to become the 1st Battalion, Highland Light Infantry in 1881.

History ...

equipped with two cannons was mobilized to repel a group of armed men marching toward the Bonsecours Market. The soldiers blocked rue Notre-Dame near the Jacques Cartier Market. Colonel Gugy intervened and dissuaded the rioters from attacking the Bonsecours Market.

On Saturday April 28, the representatives present at the Bonsecours Market appointed a special committee to prepare an address to the governor by which the Legislative Assembly deplored the acts of violence of the past three days, especially the burning of the Parliament Buildings, and gave its full support to the governor to enforce the law and restore public peace. The representatives voted for the address 36 to 16.

While not necessarily supportive of the acts of violence shaking the town of Montreal, the conservative circles of British Canada publicly expressed their contempt for the representative of the Crown. The members of the Thistle Society met and voted to strike Governor Elgin's name from the list of benefactors. On April 28, the Saint Andrew's Society

Saint Andrew's Society refers to one of many independent organizations celebrating Scottish heritage which can be found all over the world.

Some Saint Andrew's Societies limit membership to people born in Scotland or their descendants. Some sti ...

also struck him from its list of members.

On Sunday April 29, the day of the Christian Sabbath

Sabbath in Christianity is the inclusion in Christianity of a Sabbath, a day set aside for rest and worship, a practice that was mandated for the Israelites in the Ten Commandments in line with God's blessing of the seventh day (Saturday) making it ...

, the town of Montreal was at rest and no incidents were reported.

On Monday April 30, the governor and his dragoon escort left his suburban residence of Monklands for the Government House, then lodging in the Château Ramezay

The Château Ramezay is a museum and historic building on Notre-Dame Street in Old Montreal, opposite Montreal City Hall in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Built in 1705 as the residence of then-governor of Montreal, Claude de Ramezay, the Château ...

on rue Notre-Dame in downtown Montreal, to publicly receive, at 3:00 pm, the address of the House of Assembly voted on the 28th. When the governor entered rue Notre-Dame toward 14:30 pm, a crowd of protesters threw rocks and eggs and other projectiles against his carriage and the armed escort protecting him. He was hooted at by some, applauded by others along the way. The representatives, also protected by an armed escort, arrived at the meeting with the governor in the Bonsecours Market by way of the ruelle Saint-Claude.

After the ceremony for the presentation of the address, the governor and his escort returned to Monklands by taking rue St-Denis in order to avoid conflict with the crowd still demonstrating against his presence. The stratagem did not work and the governor and his guards were intercepted at the corner of Saint-Laurent and Sherbrooke by rioters who again pelted them with rocks. The brother of the governor, colonel Bruce, was seriously injured by a rock that hit his head; Ermatinger and captain Jones were also injured.

On that day, Elgin wrote to Colonial Secretary Earl Grey to suggest that if he lginfailed "to recover that position of dignified neutrality between contending parties" that he had strived to maintain, that it might be in the interest of the metropolitan government to replace him with someone who would not be personally obnoxious to an important part of Canada's population. Earl Grey, to the contrary, believed that his replacement would be harmful and would have the effect of encouraging those who violently and illegally opposed the authority of his government, which continued to receive the full support of the Westminster cabinet.

On May 10, a delegation of citizens from Toronto, who had come to Montreal to deliver an address in support of the Earl of Elgin, were attacked while in the Hôtel Têtu.

Case before Westminster

The Tories sent Allan MacNab and Cayley to London in early May to bring their petitions to the Imperial Parliament and lobby their case with the Colonial Office. The government party delegated Francis Hinks, who left Montreal on May 14, to represent the point of view of the governor, his Executive Council, and the majority of the members in both Houses of Parliament. The former colonial secretary,William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

, of the Tory Party, sided with the Canadian opposition and exercised all his influence in its favour. On June 14, John Charles Herries

John Charles Herries PC (November 1778 – 24 April 1855), known as J. C. Herries, was a British politician and financier and a frequent member of Tory and Conservative cabinets in the early to mid-19th century.

Background and education

Herri ...

, a Tory member of the House of Commons for Stamford, presented a motion to disavow the ''Rebellion Losses Act'' assented by the Earl of Elgin on April 25. But the governor of British North America received the support of both John Russell, the Whig Prime Minister as well as the Tory leader of the opposition Robert Peel. On June 16, the House of Commons rejected Herries' motion by a majority of 141 votes.

On June 19, Lord Brougham introduced a motion in the House of Lords to suspend the ''Rebellion Losses Act'' until it is amended to insure that no person who participated to the rebellion against the established government be compensated. The motion was defeated 99 to 96.

Second series of arrests

On the morning of August 15, John Orr, Robert Cooke, John Nier, Jr., John Ewing and Alexander Courtney were charged with arson and arrested by justices McCord, Wetherall and Ermatinger. All were released on bail except for Courtney. The transfer of the accused from theCourt House

A courthouse or court house is a building that is home to a local court of law and often the regional county government as well, although this is not the case in some larger cities. The term is common in North America. In most other English-sp ...

to the prison was a repeat of Perry's transfer on April 26. A crowd, determined to deliver up Courtney, attacked the military escort protecting his car, but were pushed back at the points of bayonets.

A gathering formed at dusk (after 8:00 pm), in front of the Orr Hotel, on rue Notre-Dame. Men endeavoured to raise barricades of three to four feet in height using the paving stones of the Saint-Gabriel and Notre-Dame streets. The authorities were informed of what was going on and a detachment of the 23rd Regiment of Foot (Royal Welsh Fusiliers) was sent to undo the work before the barricades could be armed. Some of the men who ran off when the army showed up regrouped and decided to attack the houses of Lafontaine and the boarding house where Baldwin was residing.

At around 10:00 pm, some 200 men attacked the residence of Lafontaine, who was at home and without a guard. It was around 5:00 pm when he learned of a rumour circulating in town saying that his house was going to be attacked. At around 6 or 7:00 pm, he sent a note to captain Wetherall to tell him about the rumour. Around the same time, some friends who had heard the rumour arrived on their own to help him defend his life and his property. Among them were Étienne-Paschal Taché

Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché (5 September 1795 – 30 July 1865) was a Canadian doctor, politician, and Father of Confederation.

Life

Born in St. Thomas, Lower Canada, in 1795, the third son of Charles Taché and Geneviève Michon, Tach� ...

, C.-J. Coursol, Joseph-Ubalde Beaudry, Moïse Brossard, and Harkin. Guns were fired on both sides. The attackers retreated with seven wounded, including William Mason, the son of a blacksmith living on Craig street, who died of his wounds the following morning. The cavalry commanded by captain Sweeney which Wetherall had sent to protect Lafontaine arrived later and missed the entire action.

The Tory press gave great coverage of the death of Mason, and, on the August 18, a grand funeral procession marched on Craig, Bonsecours and Saint-Paul street, as well as on Place Jacques-Cartier, before going toward the English cemetery.

An enquiry of the circumstances of Mason's death was opened by coroners Jones and Coursol. Lafontaine was called in to testify before the jury in the Cyrus Hotel, on Place Jacques Cartier, on August 20 at 10:00 am. While the co-premier was inside the hotel, some men spread oil in the front staircase and set it on fire. The building was evacuated, and Lafontaine exited under the protection of the military guards.

Capital moves to Toronto

On May 9, Sherwood, MPPs for Toronto, proposed to move the capital alternatively to Toronto orQuebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

. After a debate in which other cities were thrown in, Sherwood's proposal to relocate to Toronto was approved 34 to 29. On May 30, the provincial parliament was prorogued until August 9 by general William Rowan

Field Marshal Sir William Shearman Rowan,England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973 (18 June 1789 – 26 September 1879) was a British Army officer. He served in the Peninsular War and then the Hundred Days, fighting at the Battle of Waterloo and t ...

in place of governor Elgin who no longer wanted to leave Monklands. A proclamation by the governor announced the move on November 14. The Parliament stayed prorogued until it reconvened in Toronto on May 14, 1850.

Unlike Montreal, Toronto was a homogeneous town at the linguistic level; English was the common language of all main ethnic and religious groups inhabiting it. By comparison, the Montreal of the time of governor Metcalfe (1843–45) counted 27,908 Canadians, the majority French-speaking, and 15,668 immigrants from the British Isles. The statistics were similar when looking at the whole county of Montreal. In 1857 Queen Victoria chose Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

as the new and current capital.

Notes

Citations

References

In English

Works, articles

* * * * William H. AthertonMontreal, 1535–1914

Chicago: S. J. Clarke, 1914, volume II. * *

George MacKinnon Wrong

George MacKinnon Wrong (June 25, 1860 – June 29, 1948) was a Canadian clergyman and historian.

Life and career

Born at Grovesend, Ontario, Grovesend in Elgin County, Canada West (now Ontario), he was ordained in the Anglican Church of Canad ...

The Earl of Elgin

Londres: Methuen & Co., 1905, pp. 21–88 (Chapter II). * * John Douglas Borthwick

History of the Montreal prison from A.D. 1784 to A.D. 1886: Containing a Complete Record of the Troubles of 1837–1838, Burning of the Parliament Buildings in 1849, the St. Alban's Raiders, 1864, the Two Fenian Raids of 1866 and 1870 […]

Montreal: A. Periard, 1866, pp. 174–183 (Chapter XIV). * Joseph Edmund Collins

Life and Times of the Right Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald

Toronto: Rose Publishing Company, 1883, pp. 114–134 (Chapter VII). *Alexander Mackenzie

The Life and Speeches of Hon. George Brown

Toronto: Globe Printing Company, 1882, pp. 18–21 (Chapter III). *. * William Henry Withrow

A Popular History of the Dominion of Canada

Boston: BB Russell, 1878, pp. 406–412.

Witnesses and press coverage

*James Bruce Elgin and Theodore WalrondLetters and Journals of James, Eighth Earl of Elgin

Londres: John Murray, 1872, pp. 70–99

*James Bruce Elgin and Henry George Grey. ''The Elgin-Grey Papers, 1846–1852'', JO Patenaude, Printer to the King, 1937 * Alfred Perry. "A Reminiscence of '49. Who burnt the Parliament Buildings?", in ''Montreal Daily Star. Carnival Number,'', February 1887 (

online

In computer technology and telecommunications, online indicates a state of connectivity and offline indicates a disconnected state. In modern terminology, this usually refers to an Internet connection, but (especially when expressed "on line" or ...

)

* William Rufus Seaver. "Rev. Wm. Seaver to his wife, 25–27 April" in Josephine Foster. "The Montreal Riot of 1849", ''Canadian Historical Review'', 32, 1 (March 1951), pp. 61–65

*James Moir Ferres

James Moir Ferres (1813 – April 21, 1870) was a journalist and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1813 and studied at Marischal College in Aberdeen. Ferres came to Montreal in 1833 and taught at Edward Bl ...

. April 25, 1849, Extra of daily ''The Montreal Gazette''.

*The Montreal Pilot. ''The Montreal Pilot Extra: Speeches and Papers Relating to Rebellion Losses, Montreal February 26, 1849'', Montreal: The Pilot, 1849, 38 p.Portraits of Five Gentlemen: Who Were Unjustly Imprisoned by an Arbitrary Administration in Consequence of Presuming, at a Public Meeting, to Express Their Disapprobation of that Administration's "Indemnity Act," for Rewarding Traitors, and Putting a Premium on Rebellion

1849.

Parliamentary documents

* 24 p. * * *Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. ''Debates of the Legislative Assembly of United Canada, 1841–1867'', Montreal: Presses de l'École des hautes études commerciales, 1970, volume 8 (1849). *United Kingdom ParliamentHansard's Parliamentary Debates

Volume CVI (June 12 to July 6), London: G. Woodfall & Son, 1849, pp. 189–283.

Others

*Unknown. "The Canadas: How Long Can We Hold Them?", in ''The Dublin University Magazine'', Volume XXXIV, No. CCI (September 1849), pp. 314–330online

*A Canadian Loyalist. ''The Question Answered, "Did the Ministry Intend to Pay Rebels?": In a Letter to His Excellency the Right Honourable the Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, K. T., Governor General of British North America, &c. &c. &c.'', Montreal: Armour & Ramsay, 1849, 24 p. ttributed to Hugh E. Montgomerie and Alexander Morris in ''A Bibliography of Canadiana'', Dent. ''The Last Forty Years'', vol. 2, p. 143.*Cephas D. Allin and George M. Jones. ''Annexation, Preferential Trade, and Reciprocity; An Outline of the Canadian Annexation Movement of 1849–50, with Special Reference to the Questions of Preferential Trade and Reciprocity'', Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 398 p.

online

In French

Works, articles

*Éric Coupal

Éric eʁikis a French masculine given name, the equivalent of English Eric. In French-speaking Canada and Belgium it is also sometimes unaccented, and pronounced "Eric" as English with the stress on the "i". A notable French exception is Erik Sat ...

.Le Parlement brûle !

, Centre d'histoire de Montréal, Ville de Montréal, 11 avril 2006 * Alain Roy. ''Le Marché Sainte-Anne, le Parlement de Montréal et la formation d'un état moderne : un lieu d'échanges, des événements marquants, une époque charnière : étude historique'', Montréal: Direction de Montréal, 93 f. eport presented to the Institut d'histoire de l'Amérique française for the Ministère de la culture et des communications du Québec, Direction de Montréal] *Kirk Johnson, David Widgington. ''Montréal vu de près'', XYZ editeur, 2002, 156 p. ()

preview

*Jean Chartier. "L'année de la Terreur", in ''Le Devoir'', 21 avril 1999

* * * *Jacques Lacoursière, Claude Bouchard et Richard Howard. ''Notre histoire. Québec-Canada. Vers l'autonomie intérieure. 1841–1864'', volume 6, 1965, pp. 507–51

online

*

Lionel Groulx

Lionel Groulx (; 13 January 1878 – 23 May 1967) was a Canadian Roman Catholic priest, historian, and Quebec nationalism, Quebec nationalist.

Biography

Early life and ordination

Lionel Groulx, né Joseph Adolphe Lyonel Groulx, the son of ...

. "L'émeute de 1849 à Montréal", in ''Notre maître, le passé : (troisième série)'', Montreal: Librairie Granger frères limitée, 1944, 318 p. irst published in ''Ville, ô ma ville'' in 1942* 525 p.

* p. 92-1xx chap. II

Witnesses and press coverage

* iary dates: April 29 to August 21, 1849 eproduced in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849'', pp. 135–151* irst published March 11, 1885, in ''La Patrie''br>onlineeproduced in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849''* Alfred Perry. "Un souvenir de 1849 : Qui a brûlé les édifices parlementaires?", in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849'', pp. 105–125 ranslation of "Who burnt the Parliament Buildings?", in ''Montreal Daily Star. Carnival Number,'', February 1887* William Rufus Seaver. "Les confidences du marchand Seaver à son épouse", in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849'', pp. 127–134 ranslation of a letter dated April 25, 1849, transcribed in Josephine Foster. "The Montreal Riot of 1849", ''Canadian Historical Review'', 32, 1 (March 1951), p. 61–65*

James Moir Ferres

James Moir Ferres (1813 – April 21, 1870) was a journalist and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1813 and studied at Marischal College in Aberdeen. Ferres came to Montreal in 1833 and taught at Edward Bl ...

. ''Extra du 25 avril 1849'' of ''The Montreal Gazette'', ranslated to French in eproduced in Gaston Deschênes. ''Une capitale éphémère. Montréal et les événements tragiques de 1849'', pp. 101–104Parliamentary documents

* *Assemblée législative de la Province du Canada. ''Debates of the Legislative Assembly of United Canada, 1841–1867'', Montréal: Presses de l'École des hautes études commerciales, 1970, volume 8 (1849).Others

*Ville de Montréal.Place D'Youville

, in ''Site Web officiel du Vieux-Montréal''. Ville de Montréal, 30 décembre 2005 *Inconnu.

Montréal 1849 : le parlement brûle !

, in ''Les Patriotes de 1837@1838'', 30 avril 2003 *Pierre Turgeon. ''Jour de feu'', Montréal: Flammarion, 1998, 270 p. ()

ovel

Bereavement in Judaism () is a combination of ''minhag'' and ''mitzvah'' derived from the Torah and Judaism's classical rabbinic texts. The details of observance and practice vary according to each Jewish community.

Mourners

In Judaism, the p ...

* Georges-Barthélemi Faribault. ''Notice sur la destruction des archives et bibliothèques des deux chambres législatives du Canada, lors de l'émeute qui a eu lieu à Montréal le 25 avril 1849'', Québec: Impr. du Canadien, 1849, 11 p.

*McCord Museum.L'incendie du Parlement à Montréal

, in McCord Museum Web site ainting attributed to Joseph Légaré {{DEFAULTSORT:Burning Of The Parliament Buildings In Montreal History of Montreal 1849 fires in North America 1849 in Canada 1849 in law 1849 riots 1849 crimes in North America Attacks on legislatures

Montreal Riots

The burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal was an important event in pre-Confederation Canadian history and occurred on the night of April 25, 1849, in Montreal, the then-capital of the Province of Canada. It is considered a crucial mo ...

Building and structure fires in Canada

Province of Canada

Political history of Canada

Political violence in Canada

Sectarian violence

19th century in Montreal

Fires at legislative buildings

April 1849 events

1840s crimes in Canada

1849 disasters in Canada