Brontosaurus Yale Peabody Cropped on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Brontosaurus'' (; meaning "thunder lizard" from

The dinosaurs of North America

'. US Government Printing Office. Marsh believed that ''Brontosaurus'' was a member of the Atlantosauridae, a clade of sauropod dinosaurs named by him in 1877 that also comprised '' A year later in 1880, another partial postcranial ''Brontosaurus'' skeleton was collected in Como Bluff by Reed, including well preserved limb elements. Marsh named this second skeleton ''Brontosaurus amplus'' ("large thunder lizard") in 1881, but it was considered a synonym of ''B. excelsus'' in 2015''.''

Further south in Felch Quarry at Garden Park,

A year later in 1880, another partial postcranial ''Brontosaurus'' skeleton was collected in Como Bluff by Reed, including well preserved limb elements. Marsh named this second skeleton ''Brontosaurus amplus'' ("large thunder lizard") in 1881, but it was considered a synonym of ''B. excelsus'' in 2015''.''

Further south in Felch Quarry at Garden Park,

During a Carnegie Museum expedition in 1901 to Wyoming,

During a Carnegie Museum expedition in 1901 to Wyoming,

A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda).

''PeerJ'', ''3'', e857. The adult skeleton specifically was very well preserved, bearing many cervical and caudal vertebrae, and is the most complete definite specimen of ''Brontosaurus parvus''. The skeletons were granted a new genus and species name, ''Elosaurus parvus'' ("little field lizard"), by Olof A. Peterson and Charles Gilmore in 1902. Both of the specimens came from the Brushy Basin Member of the In 1905, the

In 1905, the

Another specimen of an Apatosaurine now referred to ''Brontosaurus'' was discovered in 1993 by the Tate Geological Museum, also from the Morrison Formation of central Wyoming. The specimen consisted of a partial postcranial skeleton, including a complete manus and many vertebrae, and described by James Filla and Pat Redman a year later. Filla and Redman named the specimen ''Apatosaurus yahnahpin'' ("yahnahpin-wearing deceptive lizard"), but Robert T. Bakker gave it the genus name ''Eobrontosaurus'' in 1998. Bakker believed that ''Eobrontosaurus'' was the direct predecessor to ''Brontosaurus'''','' although later Tschopp ''et al''.'s phylogenetic analysis placed ''B. yahnahpin'' as the basalmost species of ''Brontosaurus''''.''

In 2008, a nearly complete postcranial skeleton of an Apatosaurine was collected in Utah by crews working for

Another specimen of an Apatosaurine now referred to ''Brontosaurus'' was discovered in 1993 by the Tate Geological Museum, also from the Morrison Formation of central Wyoming. The specimen consisted of a partial postcranial skeleton, including a complete manus and many vertebrae, and described by James Filla and Pat Redman a year later. Filla and Redman named the specimen ''Apatosaurus yahnahpin'' ("yahnahpin-wearing deceptive lizard"), but Robert T. Bakker gave it the genus name ''Eobrontosaurus'' in 1998. Bakker believed that ''Eobrontosaurus'' was the direct predecessor to ''Brontosaurus'''','' although later Tschopp ''et al''.'s phylogenetic analysis placed ''B. yahnahpin'' as the basalmost species of ''Brontosaurus''''.''

In 2008, a nearly complete postcranial skeleton of an Apatosaurine was collected in Utah by crews working for

"Not so fast, Brontosaurus"

Time.com Paleontologist

"Is "Brontosaurus" Back? Not So Fast!"

Skeptic.com.

''Brontosaurus'' was a large, long-necked,

''Brontosaurus'' was a large, long-necked,  The limb bones were also very robust. The arm bones are stout, with the

The limb bones were also very robust. The arm bones are stout, with the

Originally named by its discoverer

Originally named by its discoverer

''Brontosaurus parvus'', first described as ''Elosaurus'' in 1902 by Peterson and Gilmore, was reassigned to ''Apatosaurus'' in 1994, and to ''Brontosaurus'' in 2015. Specimens assigned to this species include the

''Brontosaurus parvus'', first described as ''Elosaurus'' in 1902 by Peterson and Gilmore, was reassigned to ''Apatosaurus'' in 1994, and to ''Brontosaurus'' in 2015. Specimens assigned to this species include the

Winter 2010 Appendix.

/ref> The

Historically, sauropods like ''Brontosaurus'' were believed to be too massive to support their own weight on dry land, so theoretically they must have lived partly submerged in water, perhaps in swamps. Recent findings do not support this, and sauropods are thought to have been fully terrestrial animals.

Diplodocids like ''Brontosaurus'' are often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to browse on tall trees. Though some studies have suggested that diplodocid necks were less flexible than previously believed, other studies have found that all

Historically, sauropods like ''Brontosaurus'' were believed to be too massive to support their own weight on dry land, so theoretically they must have lived partly submerged in water, perhaps in swamps. Recent findings do not support this, and sauropods are thought to have been fully terrestrial animals.

Diplodocids like ''Brontosaurus'' are often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to browse on tall trees. Though some studies have suggested that diplodocid necks were less flexible than previously believed, other studies have found that all

The

The

Is Brontosaurus Back? (Youtube video, 11 minutes, 2015)

{{Portal bar, Dinosaurs, Paleontology, United States Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation Apatosaurinae Fossil taxa described in 1879 Articles containing video clips Taxa named by Othniel Charles Marsh Paleontology in Wyoming Paleontology in Utah Controversial dinosaur taxa Late Jurassic dinosaurs of North America

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, "thunder" and , "lizard") is a genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of gigantic quadruped

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion where four limbs are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four limbs is said to be a quadruped (from Latin ''quattuor' ...

sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; from '' sauro-'' + '' -pod'', 'lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their bo ...

dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

. Although the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

, ''B. excelsus'', had long been considered a species of the closely related ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

'' and therefore invalid, researchers proposed in 2015 that ''Brontosaurus'' is a genus separate from ''Apatosaurus'' and that it contains three species: ''B. excelsus'', ''B. yahnahpin'', and ''B. parvus''.

''Brontosaurus'' had a long, thin neck and a small head adapted for a herbivorous lifestyle, a bulky, heavy torso, and a long, whip-like tail. The various species lived during the Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

epoch, in the Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

of what is now North America, and were extinct by the end of the Jurassic.Foster, J. (2007). ''Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World''. Indiana University Press. 389pp. Adult individuals of ''Brontosaurus'' are estimated to have measured up to long and weighed up to .

As the archetypal

The concept of an archetype (; ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main model that ...

sauropod, ''Brontosaurus'' is one of the best-known dinosaurs and has been featured in film, advertising, and postage stamps, as well as many other types of media.

History of discovery

Initial discovery and the Felch Quarry skull

In 1879,Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

, a professor of paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, announced the discovery of a large and fairly complete sauropod skeleton collected from Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

rocks at Como Bluff

Como Bluff is a long ridge extending east–west, located between the towns of Rock River and Medicine Bow, Wyoming. The ridge is an anticline, formed as a result of compressional geological folding. Three geological formations, the Sundance, t ...

, Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

by William Harlow Reed

William Harlow Reed (9 June 1848 – 24 April 1915) was an American fossil collector and pioneer. He served as a curator at the Museum of Geology at the University of Wyoming, Laramie. He collected for a while for Othniel Charles Marsh but left a ...

. He identified it as belonging to an entirely new genus and species, which he named ''Brontosaurus excelsus'',

meaning "thunder lizard", from the Greek / meaning "thunder" and / meaning "lizard", and from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''excelsus'', "noble" or "high". By this time, the Morrison Formation had become the center of the Bone Wars

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Acade ...

, a fossil-collecting rivalry between Marsh and another early paleontologist, Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interested ...

. Because of this, the publications and descriptions of taxa by Marsh and Cope were rushed at the time. ''Brontosaurus excelsus'' type specimen ( YPM 1980) was one of the most complete sauropod skeletons known at the time, preserving many of the characteristic but fragile cervical vertebrae.Marsh, O. C. (1896). The dinosaurs of North America

'. US Government Printing Office. Marsh believed that ''Brontosaurus'' was a member of the Atlantosauridae, a clade of sauropod dinosaurs named by him in 1877 that also comprised ''

Atlantosaurus

''Atlantosaurus'' (meaning "Atlas lizard") is a dubious genus of sauropod dinosaur. It contains a single species, ''Atlantosaurus montanus'', from the upper Morrison Formation of Colorado, United States. ''Atlantosaurus'' was the first sauropod t ...

'' and ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

''.

A year later in 1880, another partial postcranial ''Brontosaurus'' skeleton was collected in Como Bluff by Reed, including well preserved limb elements. Marsh named this second skeleton ''Brontosaurus amplus'' ("large thunder lizard") in 1881, but it was considered a synonym of ''B. excelsus'' in 2015''.''

Further south in Felch Quarry at Garden Park,

A year later in 1880, another partial postcranial ''Brontosaurus'' skeleton was collected in Como Bluff by Reed, including well preserved limb elements. Marsh named this second skeleton ''Brontosaurus amplus'' ("large thunder lizard") in 1881, but it was considered a synonym of ''B. excelsus'' in 2015''.''

Further south in Felch Quarry at Garden Park, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

, Marshall P. Felch collected a disarticulated partial skull (USNM

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with 7. ...

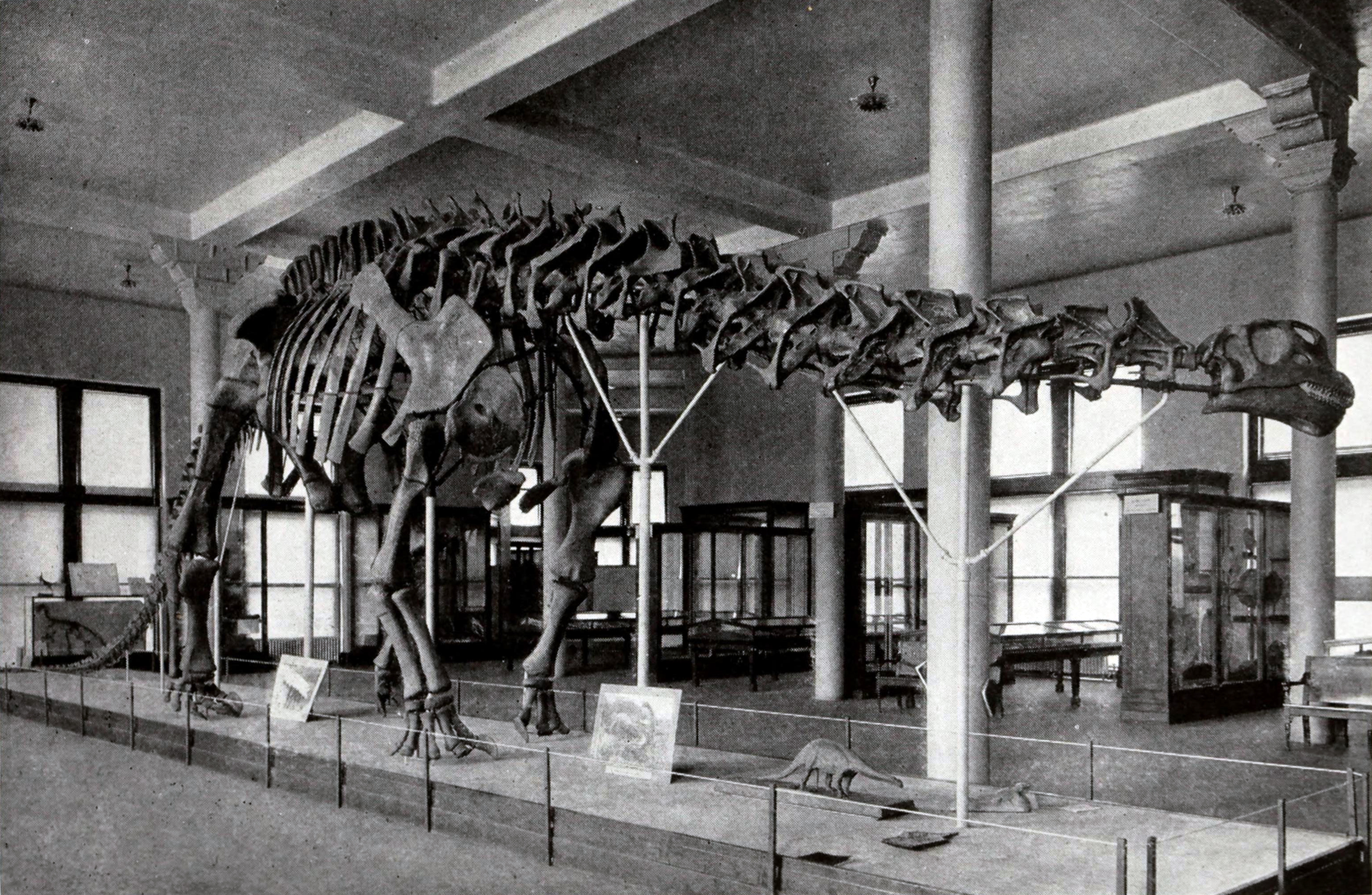

V 5730) of a sauropod in August 1883 and sent the specimen to Yale. Marsh referred the skull to ''B. excelsus'',Marsh, O. C. (1891). Restoration of Brontosaurus. ''American Journal of Science, Series 3'', ''41'', 341-342. later featuring it in a skeletal reconstruction of the ''B. excelsus'' type specimen in 1891 and the illustration was featured again in Marsh's landmark publication, ''The Dinosaurs of North America'', in 1896. At the Yale Peabody Museum

The Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University is among the oldest, largest, and most prolific university List of natural history museums, natural history museums in the world. It was founded by the philanthropist George Peabody in 1866 ...

, the skeleton of ''Brontosaurus excelsus'' was mounted in 1931 with a skull based on the Marsh reconstruction of the Felch Quarry skull. While at the time most museums were using ''Camarasaurus

''Camarasaurus'' ( ) was a genus of quadrupedal, herbivorous dinosaurs and is the most common North American sauropod fossil. Its fossil remains have been found in the Morrison Formation, dating to the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to Titho ...

'' casts for skulls, the Peabody Museum sculpted a completely different skull based on Marsh's recon. The skull also included forward-pointing nasals, something truly different to any dinosaur, and fenestrae differing from the drawing and other skulls, and the mandible was based on a ''Camarasaurus''Brachiosaurus

''Brachiosaurus'' () is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic, about 154to 150million years ago. It was first described by American paleontologist Elmer S. Riggs in 1903 from fossils found in th ...

'' instead and this was supported in 2020 with a redescription of the Brachiosaurid

The Brachiosauridae ("arm lizards", from Greek ''brachion'' (βραχίων) = "arm" and ''sauros'' = "lizard") are a family or clade of herbivorous, quadrupedal sauropod dinosaurs. Brachiosaurids had long necks that enabled them to access the le ...

material found at Felch Quarry.

Second Dinosaur Rush and skull issue

During a Carnegie Museum expedition in 1901 to Wyoming,

During a Carnegie Museum expedition in 1901 to Wyoming, William Harlow Reed

William Harlow Reed (9 June 1848 – 24 April 1915) was an American fossil collector and pioneer. He served as a curator at the Museum of Geology at the University of Wyoming, Laramie. He collected for a while for Othniel Charles Marsh but left a ...

collected another ''Brontosaurus'' skeleton, a partial postcranial skeleton of a young juvenile (CM 566), including partial limbs, intermingled with a fairly complete skeleton of an adult (UW 15556).Tschopp, E., Mateus, O., & Benson, R. B. (2015)A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda).

''PeerJ'', ''3'', e857. The adult skeleton specifically was very well preserved, bearing many cervical and caudal vertebrae, and is the most complete definite specimen of ''Brontosaurus parvus''. The skeletons were granted a new genus and species name, ''Elosaurus parvus'' ("little field lizard"), by Olof A. Peterson and Charles Gilmore in 1902. Both of the specimens came from the Brushy Basin Member of the

Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

. The species was later transferred to ''Apatosaurus'' by several authors until it was placed in ''Brontosaurus'' in 2015 by Tschopp ''et al''.

Elmer Riggs

Elmer Samuel Riggs (January 23, 1869 – March 25, 1963) was an American paleontologist known for his work with the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois.

Biography

He was born in Trafalgar, Indiana, and moved with his famil ...

, in the 1903 edition of ''Geological Series of the Field Columbian Museum'', argued that ''Brontosaurus'' was not different enough from ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

'' to warrant its own genus, so he created the new combination ''Apatosaurus excelsus'' for it. Riggs stated that "In view of these facts the two genera may be regarded as synonymous. As the term 'Apatosaurus' has priority, 'Brontosaurus' will be regarded as a synonym". Nonetheless, before the mounting of the American Museum of Natural History specimen, Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

chose to label the skeleton "Brontosaurus", though he was a strong opponent of Marsh and his taxa.

In 1905, the

In 1905, the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

(AMNH) unveiled the first-ever mounted skeleton of a sauropod, a composite specimen (mainly made of bones from AMNH 460) that they referred to as the species ''Brontosaurus excelsus''. The AMNH specimen was very complete, only missing the feet (feet from the specimen AMNH 592 were added to the mount), lower leg, and shoulder bones (added from AMNH 222), and tail bones (added from AMNH 339).Norell, M.A., Gaffney, E.S., & Dingus, L. (1995). ''Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History''. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. To complete the mount, the rest of the tail was fashioned to appear as Marsh believed it should, which had too few vertebrae. In addition, a sculpted model of what the museum felt the skull of this massive creature might look like was placed on the skeleton. This was not a delicate skull like that of ''Diplodocus'', which would later turn out to be more accurate, but was based on "the biggest, thickest, strongest skull bones, lower jaws and tooth crowns from three different quarries". These skulls were likely those of ''Camarasaurus'', the only other sauropod for which good skull material was known at the time. The mount construction was overseen by Adam Hermann, who failed to find ''Brontosaurus'' skulls. Hermann was forced to sculpt a stand-in skull by hand. Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

noted in a publication that the skull was "largely conjectural and based on that of ''Morosaurus''" (now ''Camarasaurus'').

In 1909, an ''Apatosaurus'' skull was found, during the first expedition to what would become the Carnegie Quarry at Dinosaur National Monument

Dinosaur National Monument is an American national monument located on the southeast flank of the Uinta Mountains on the border between Colorado and Utah at the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers. Although most of the monument area is in ...

, led by Earl Douglass. The skull was found a few meters away from a skeleton (specimen CM 3018) identified as the new species ''Apatosaurus louisae

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

''. The skull was designated CM 11162, and was very similar to the skull of ''Diplodocus''. It was accepted as belonging to the ''Apatosaurus'' specimen by Douglass and Carnegie Museum director William H. Holland, although other scientists, most notably Osborn, rejected this identification. Holland defended his view in 1914 in an address to the Paleontological Society of America, yet he left the Carnegie Museum mount headless. While some thought Holland was attempting to avoid conflict with Osborn, others suspected that Holland was waiting until an articulated skull and neck were found to confirm the association of the skull and skeleton. After Holland's death in 1934, a cast of a ''Camarasaurus'' skull was placed on the mount by museum staff.

Skull correction, resurgent discoveries, and reassessment

No apatosaurine skull was mentioned in literature until the 1970s, when John Stanton McIntosh and David Berman redescribed the skulls of ''Diplodocus'' and ''Apatosaurus'' in 1975. They found that though he never published his opinion, Holland was almost certainly correct, that ''Apatosaurus'' (and ''Brontosaurus'') had a ''Diplodocus''-like skull. According to them, many skulls long thought to pertain to ''Diplodocus'' might instead be those of ''Apatosaurus''. They reassigned multiple skulls to ''Apatosaurus'' based on associated and closely associated vertebrae. Though they supported Holland, ''Apatosaurus'' was noted to possibly have possessed a ''Camarasaurus''-like skull, based on a disarticulated ''Camarasaurus''-like tooth found at the precise site where an ''Apatosaurus'' specimen was found years before. On October 20, 1979, after the publications by McIntosh and Berman, the first skull of an ''Apatosaurus'' was mounted on a skeleton in a museum, that of the Carnegie. In 1995, the American Museum of Natural History followed suit, and unveiled their remounted skeleton (now labelled ''Apatosaurus excelsus'') with a corrected tail and a new skull cast from ''A. louisae''. In 1998, Robert T. Bakker referred a skull and mandible of an Apatosaurine fromComo Bluff

Como Bluff is a long ridge extending east–west, located between the towns of Rock River and Medicine Bow, Wyoming. The ridge is an anticline, formed as a result of compressional geological folding. Three geological formations, the Sundance, t ...

to ''Brontosaurus excelsus'' (TATE

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

099-01)'','' though the skull is still undescribed. In 2011, the first specimen of ''Apatosaurus'' where a skull was found articulated with its cervical vertebrae was described. This specimen, CMC VP 7180, was found to differ in both skull and neck features from ''A. louisae'', and the specimen was found to have a majority of features related to those of ''A. ajax''.

Another specimen of an Apatosaurine now referred to ''Brontosaurus'' was discovered in 1993 by the Tate Geological Museum, also from the Morrison Formation of central Wyoming. The specimen consisted of a partial postcranial skeleton, including a complete manus and many vertebrae, and described by James Filla and Pat Redman a year later. Filla and Redman named the specimen ''Apatosaurus yahnahpin'' ("yahnahpin-wearing deceptive lizard"), but Robert T. Bakker gave it the genus name ''Eobrontosaurus'' in 1998. Bakker believed that ''Eobrontosaurus'' was the direct predecessor to ''Brontosaurus'''','' although later Tschopp ''et al''.'s phylogenetic analysis placed ''B. yahnahpin'' as the basalmost species of ''Brontosaurus''''.''

In 2008, a nearly complete postcranial skeleton of an Apatosaurine was collected in Utah by crews working for

Another specimen of an Apatosaurine now referred to ''Brontosaurus'' was discovered in 1993 by the Tate Geological Museum, also from the Morrison Formation of central Wyoming. The specimen consisted of a partial postcranial skeleton, including a complete manus and many vertebrae, and described by James Filla and Pat Redman a year later. Filla and Redman named the specimen ''Apatosaurus yahnahpin'' ("yahnahpin-wearing deceptive lizard"), but Robert T. Bakker gave it the genus name ''Eobrontosaurus'' in 1998. Bakker believed that ''Eobrontosaurus'' was the direct predecessor to ''Brontosaurus'''','' although later Tschopp ''et al''.'s phylogenetic analysis placed ''B. yahnahpin'' as the basalmost species of ''Brontosaurus''''.''

In 2008, a nearly complete postcranial skeleton of an Apatosaurine was collected in Utah by crews working for Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU, sometimes referred to colloquially as The Y) is a private research university in Provo, Utah. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day ...

(BYU 1252-18531) where some of the remains are currently on display. The skeleton is undescribed, but many of the features of the skeleton are shared with ''Brontosaurus parvus''.

Almost all 20th-century paleontologists agreed with Riggs that all ''Apatosaurus'' and ''Brontosaurus'' species should be classified in a single genus. According to the rules of the ICZN

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the I ...

(which governs the scientific names of animals), the name ''Apatosaurus'', having been published first, had priority as the official name; ''Brontosaurus'' was considered a junior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linna ...

and was therefore discarded from formal use. Despite this, at least one paleontologist— Robert T. Bakker—argued in the 1990s that ''A. ajax'' and ''A. excelsus'' are in fact sufficiently distinct that the latter continues to merit a separate genus. In 2015, an extensive study of diplodocid relationships by Emanuel Tschopp, Octavio Mateus, and Roger Benson concluded that ''Brontosaurus'' was indeed a valid genus of sauropod distinct from ''Apatosaurus''. The scientists developed a statistical method to more objectively assess differences between fossil genera and species, and concluded that ''Brontosaurus'' could be "resurrected" as a valid name. They assigned two former ''Apatosaurus'' species, ''A. parvus'' and ''A. yahnahpin'', to ''Brontosaurus'', as well as the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

''B. excelsus''. Paleontologist Michael D'Emic made a critique.D'Emic, M. 2015"Not so fast, Brontosaurus"

Time.com Paleontologist

Donald Prothero

Donald Ross Prothero (February 21, 1954) is an American geologist, paleontologist, and author who specializes in mammalian paleontology and magnetostratigraphy, a technique to date rock layers of the Cenozoic era and its use to date the climate ...

criticized the mass media reaction to this study as superficial and premature.Prothero, D. 2015"Is "Brontosaurus" Back? Not So Fast!"

Skeptic.com.

Description

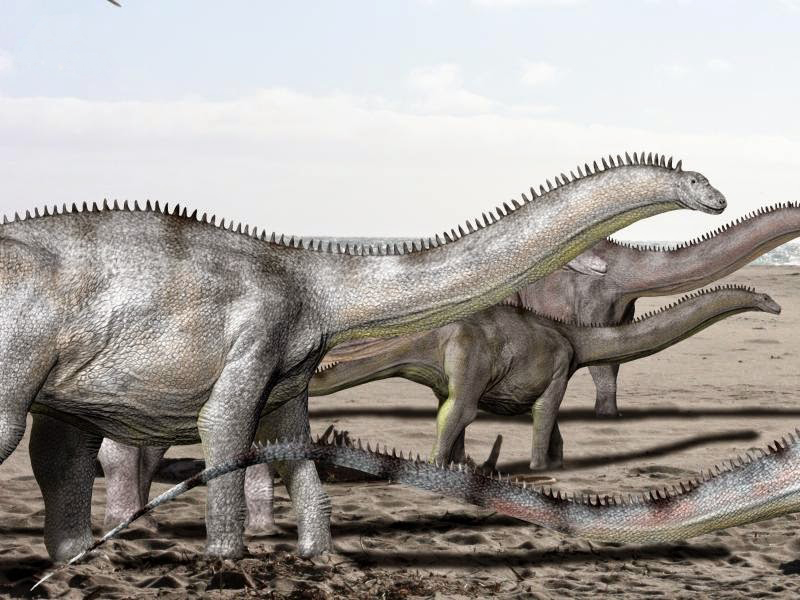

''Brontosaurus'' was a large, long-necked,

''Brontosaurus'' was a large, long-necked, quadruped

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion where four limbs are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four limbs is said to be a quadruped (from Latin ''quattuor' ...

al animal with a long, whip-like tail, and forelimbs that were slightly shorter than its hindlimbs. The largest species, ''B. excelsus'', measured up to long from head to tail and weighed up to ; other species were smaller, measuring long and weighing .

The skull of ''Brontosaurus'' has not been found, but was probably similar to the skull of the closely related ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

''. Like those of other sauropods, the vertebrae of the neck were deeply bifurcated; that is, they carried paired spines, resulting in a wide and deep neck. The spine and tail consisted of 15 cervicals, ten dorsals, five sacrals, and about 82 caudals. The number of caudal vertebrae was noted to vary, even within a species. The cervical vertebrae were stouter than other diplodocid

Diplodocids, or members of the family Diplodocidae ("double beams"), are a group of sauropod dinosaurs. The family includes some of the longest creatures ever to walk the Earth, including ''Diplodocus'' and ''Supersaurus'', some of which may have ...

s, though not as stout as in mature specimens of ''Apatosaurus''. The dorsal ribs are not fused or tightly attached to their vertebrae, instead being loosely articulated. Ten dorsal ribs are on either side of the body. The large neck was filled with an extensive system of weight-saving air sacs. ''Brontosaurus'', like its close relative ''Apatosaurus'', had tall spines on its vertebrae, which made up more than half the height of the individual bones. The shape of the tail was unusual for diplodocids, being comparatively slender, due to the vertebral spines rapidly decreasing in height the farther they are from the hips. ''Brontosaurus'' spp. also had very long ribs compared to most other diplodocids, giving them unusually deep chests. As in other diplodocids, the last portion of the tail of ''Brontosaurus'' possessed a whip-like structure.

The limb bones were also very robust. The arm bones are stout, with the

The limb bones were also very robust. The arm bones are stout, with the humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

resembling that of ''Camarasaurus

''Camarasaurus'' ( ) was a genus of quadrupedal, herbivorous dinosaurs and is the most common North American sauropod fossil. Its fossil remains have been found in the Morrison Formation, dating to the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to Titho ...

'', and those of ''B. excelsus'' being nearly identical to those of ''Apatosaurus ajax''. Charles Gilmore in 1936 noted that previous reconstructions erroneously proposed that the radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

and ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

could cross, when in life they would have remained parallel. ''Brontosaurus'' had a single large claw on each forelimb, and the first three toes possessed claws on each foot. Even by 1936, it was recognized that no sauropod had more than one hand claw preserved, and this one claw is now accepted as the maximum number throughout the entire group. The single front claw bone is slightly curved and squarely shortened on the front end. The hip bones included robust ilia and the fused pubes and ischia

Ischia ( , , ) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about from Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Roughly trapezoidal in shape, it measures approximately east to west ...

. The tibia and fibula bones of the lower leg were different from the slender bones of ''Diplodocus'', but nearly indistinguishable from those of ''Camarasaurus''. The fibula is longer than the tibia, although it is also more slender.

Classification

''Brontosaurus'' is a member of thefamily

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Diplodocidae

Diplodocids, or members of the family Diplodocidae ("double beams"), are a group of sauropod dinosaurs. The family includes some of the longest creatures ever to walk the Earth, including ''Diplodocus'' and '' Supersaurus'', some of which may hav ...

, a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

of gigantic sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; from '' sauro-'' + '' -pod'', 'lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their bo ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s. The family includes some of the longest and largest creatures ever to walk the earth, including ''Diplodocus

''Diplodocus'' (, , or ) was a genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaurs, whose fossils were first discovered in 1877 by S. W. Williston. The generic name, coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, is a neo-Latin term derived from Greek διπ� ...

'', ''Supersaurus

''Supersaurus'' (meaning "super lizard") is a genus of diplodocid Sauropoda, sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. The type species, ''S. vivianae'', was first discovered by Vivian Jones of Delta, Colorad ...

'', and ''Barosaurus

''Barosaurus'' ( ) was a giant, long-tailed, long-necked, plant-eating sauropod dinosaur closely related to the more familiar ''Diplodocus''. Remains have been found in the Morrison Formation from the Upper Jurassic Period of Utah and South Da ...

''. ''Brontosaurus'' is also classified in the subfamily Apatosaurinae

Apatosaurinae is a subfamily of diplodocid sauropods that existed between 157 and 150 million years ago in North America. The group includes two genera for certain, ''Apatosaurus'' and ''Brontosaurus'', and at least five species. ''Atlantosaurus ...

, which also includes ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

'' and one or more possible unnamed genera. Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

described ''Brontosaurus'' as being allied to ''Atlantosaurus

''Atlantosaurus'' (meaning "Atlas lizard") is a dubious genus of sauropod dinosaur. It contains a single species, ''Atlantosaurus montanus'', from the upper Morrison Formation of Colorado, United States. ''Atlantosaurus'' was the first sauropod t ...

'', within the now defunct group Atlantosauridae. In 1878, Marsh raised his family to the rank of suborder, including ''Apatosaurus'', ''Brontosaurus'', ''Atlantosaurus'', ''Morosaurus

''Camarasaurus'' ( ) was a genus of quadrupedal, herbivorous dinosaurs and is the most common North American sauropod fossil. Its fossil remains have been found in the Morrison Formation, dating to the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to Titho ...

'' (=''Camarasaurus''), and ''Diplodocus''. He classified this group within Sauropoda. In 1903, Elmer S. Riggs

Elmer Samuel Riggs (January 23, 1869 – March 25, 1963) was an American paleontologist known for his work with the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois.

Biography

He was born in Trafalgar, Indiana, and moved with his family ...

mentioned that the name Sauropoda would be a junior synonym of earlier names, and grouped ''Apatosaurus'' within Opisthocoelia. Most authors still use Sauropoda as the group name.

Originally named by its discoverer

Originally named by its discoverer Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

in 1879, ''Brontosaurus'' had long been considered a junior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linna ...

of ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

''; its type species, ''Brontosaurus excelsus'', was reclassified as ''A. excelsus'' in 1903. However, an extensive study published in 2015 by a joint British-Portuguese research team concluded that ''Brontosaurus'' was a valid genus of sauropod distinct from ''Apatosaurus''. Nevertheless, not all paleontologists agree with this division. The same study classified two additional species that had once been considered ''Apatosaurus'' and ''Eobrontosaurus'' as ''Brontosaurus parvus'' and ''Brontosaurus yahnahpin'' respectively. Cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

of the Diplodocidae after Tschopp, Mateus, and Benson (2015):

Species

* ''Brontosaurus excelsus'', thetype species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

of ''Brontosaurus'', was first named by Marsh in 1879. Many specimens, including the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

specimen YPM 1980, have been assigned to the species. They include FMNH P25112, the skeleton mounted at the Field Museum of Natural History

The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), also known as The Field Museum, is a natural history museum in Chicago, Illinois, and is one of the largest such museums in the world. The museum is popular for the size and quality of its educational ...

, which has since been found to represent an unknown species of apatosaurine. ''Brontosaurus amplus'', occasionally assigned to ''B. parvus'', is a junior synonym of ''B. excelsus''. ''B. excelsus'' therefore only includes its type specimen and the type specimen of ''B. amplus''. The largest of these specimens is estimated to have weighed up to 15 tonnes and measured up to long from head to tail. Both known definitive ''B. excelsus'' fossils have been reported from Reed's Quarry 10 of the Morrison Formation Brushy Basin member in Albany County, Wyoming

Albany County ( ) is a county in the U.S. state of Wyoming. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 37,066. Its county seat is Laramie, the site of the University of Wyoming. Its south border lies on the northern Colorado state ...

, dated to the late Kimmeridgian age, about 152 million years ago.

*  ''Brontosaurus parvus'', first described as ''Elosaurus'' in 1902 by Peterson and Gilmore, was reassigned to ''Apatosaurus'' in 1994, and to ''Brontosaurus'' in 2015. Specimens assigned to this species include the

''Brontosaurus parvus'', first described as ''Elosaurus'' in 1902 by Peterson and Gilmore, was reassigned to ''Apatosaurus'' in 1994, and to ''Brontosaurus'' in 2015. Specimens assigned to this species include the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

, CM 566 (a partial skeleton of a juvenile found in Sheep Creek Quarry 4 in Albany County, WY), BYU 1252-18531 (a nearly complete skeleton found in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

and mounted at Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU, sometimes referred to colloquially as The Y) is a private research university in Provo, Utah. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day ...

), and the partial skeleton UW 15556 (which had once been accidentally mixed together with the holotype). It dates to the middle Kimmeridgian. Adult specimens are estimated to have weighed up to 14 tonnes and measured up to long from head to tail.

*''Brontosaurus yahnahpin'' is the oldest species, known from a single site from the lower Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

, Bertha Quarry, in Albany County, Wyoming, dating to about 155 million years ago.Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, U.S.A." Pp. 77–114 in Gillette, D. D. (ed.), ''Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah''. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1. It grew up to long.Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) ''Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages,'Winter 2010 Appendix.

/ref> The

type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

, ''E. yahnahpin'', was described by James Filla and Patrick Redman in 1994 as a species of ''Apatosaurus

''Apatosaurus'' (; meaning "deceptive lizard") is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic period. Othniel Charles Marsh described and named the first-known species, ''A. ajax'', in 1877, an ...

'' (''A. yahnahpin''). The specific name is derived from Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

''mah-koo yah-nah-pin'', "breast necklace", a reference to the pairs of sternal ribs that resemble the hair pipe

A Hair pipe is a term for an elongated bead, more than 1.5 inches long, which are popular with American Indians, particularly from the Great Plains and Northwest Plateau.

History

In 1878, Joseph H. Sherburne became a trader to the Ponca peopl ...

s traditionally worn by the tribe. The holotype specimen is TATE-001, a relatively complete postcrania Postcrania (postcranium, adjective: postcranial) in zoology and vertebrate paleontology is all or part of the skeleton apart from the skull. Frequently, fossil remains, e.g. of dinosaurs or other extinct tetrapods, consist of partial or isolated sk ...

l skeleton found in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

, in the lower Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

. More fragmentary remains have also been referred to the species. A re-evaluation by Robert T. Bakker in 1998 found it to be more primitive, so Bakker coined the new generic name ''Eobrontosaurus'', derived from Greek , "dawn", and ''Brontosaurus''.

The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

below is the result of an analysis by Tschopp, Mateus, and Benson (2015). The authors analyzed most diplodocid type specimens separately to deduce which specimen belonged to which species and genus.

Palaeobiology

Posture and locomotion

Historically, sauropods like ''Brontosaurus'' were believed to be too massive to support their own weight on dry land, so theoretically they must have lived partly submerged in water, perhaps in swamps. Recent findings do not support this, and sauropods are thought to have been fully terrestrial animals.

Diplodocids like ''Brontosaurus'' are often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to browse on tall trees. Though some studies have suggested that diplodocid necks were less flexible than previously believed, other studies have found that all

Historically, sauropods like ''Brontosaurus'' were believed to be too massive to support their own weight on dry land, so theoretically they must have lived partly submerged in water, perhaps in swamps. Recent findings do not support this, and sauropods are thought to have been fully terrestrial animals.

Diplodocids like ''Brontosaurus'' are often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to browse on tall trees. Though some studies have suggested that diplodocid necks were less flexible than previously believed, other studies have found that all tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids (pelycosaurs, extinct theraps ...

s appear to hold their necks at the maximum possible vertical extension when in a normal, alert posture, and argue that the same would hold true for sauropods barring any unknown, unique characteristics that set the soft tissue anatomy of their necks apart from that of other animals.

Trackways of sauropods like ''Brontosaurus'' show that the average range for them was around per day, and they could potentially reach a top speed of . The slow locomotion of sauropods may be due to the minimal muscling or recoil after strides.

Various uses have been proposed for the single claw on the forelimb of sauropods. They were suggested to have been for defence, but the shape and size of them makes this unlikely. Other predictions were that it could be for feeding, but the most probable is that the claw was for grasping objects like tree trunks when rearing.

Physiology

James Spotila ''et al.'' (1991) suggest that the large body size of ''Brontosaurus'' and other sauropods would have made them unable to maintain high metabolic rates, as they would not be able to release enough heat. However, temperatures in the Jurassic were 3 degrees Celsius higher than present. They assumed that the animals had a reptilian respiratory system. Wedel found that an avian system would have allowed them to dump more heat. Some scientists have argued that the heart would have had trouble sustaining sufficient blood pressure to oxygenate the brain.Juveniles

Juvenile ''Brontosaurus'' material is known based on the type specimen of ''B. parvus''. The material of this specimen, CM 566, includes vertebrae from various regions, one pelvic bone, and some bones of the hindlimb.Tail

An article that appeared in the November 1997 issue of ''Discover'' magazine reported research into the mechanics of diplodocid tails byNathan Myhrvold

Nathan Paul Myhrvold (born August 3, 1959), formerly Chief Technology Officer at Microsoft, is co-founder of Intellectual Ventures and the principal author of ''Modernist Cuisine'' and its successor books. Myhrvold was listed as co-inventor o ...

, a computer scientist

A computer scientist is a person who is trained in the academic study of computer science.

Computer scientists typically work on the theoretical side of computation, as opposed to the hardware side on which computer engineers mainly focus (al ...

from Microsoft

Microsoft Corporation is an American multinational technology corporation producing computer software, consumer electronics, personal computers, and related services headquartered at the Microsoft Redmond campus located in Redmond, Washing ...

. Myhrvold carried out a computer simulation

Computer simulation is the process of mathematical modelling, performed on a computer, which is designed to predict the behaviour of, or the outcome of, a real-world or physical system. The reliability of some mathematical models can be dete ...

of the tail, which in diplodocids like ''Brontosaurus'' was a very long, tapering structure resembling a bullwhip

A bullwhip is a single-tailed whip, usually made of braided leather or nylon, designed as a tool for working with livestock or competition.

Bullwhips are pastoral tools, traditionally used to control livestock in open country. A bullwhip's leng ...

. This computer modeling suggested that sauropods were capable of producing a whip-like cracking sound of over 200 decibel

The decibel (symbol: dB) is a relative unit of measurement equal to one tenth of a bel (B). It expresses the ratio of two values of a power or root-power quantity on a logarithmic scale. Two signals whose levels differ by one decibel have a po ...

s, comparable to the volume of a cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

. There is some circumstantial evidence supporting this as well: a number of diplodocids have been found with fused or damaged tail vertebrae, which may be a symptom of cracking their tails: these are particularly common between the 18th and the 25th caudal vertebra, a region the authors consider a transitional zone between the stiff muscular base and the flexible whiplike section. However, Rega (2012) notes that ''Camarasaurus

''Camarasaurus'' ( ) was a genus of quadrupedal, herbivorous dinosaurs and is the most common North American sauropod fossil. Its fossil remains have been found in the Morrison Formation, dating to the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to Titho ...

'', while lacking a tailwhip, displays a similar level of caudal co-ossification, and that ''Mamenchisaurus

''Mamenchisaurus'' (or spelling pronunciation ) is a genus of sauropod dinosaur known for their remarkably long necks which made up nearly half the total body length. Numerous species have been assigned to the genus; however, many of these might ...

'', while having the same pattern of vertebral metrics, lacks a tailwhip and doesn't display fusion in any "transitional region". Also, the crush fractures which would be expected if the tail was used as a whip have never been found in diplodocids. More recently, Baron (2020) considers the use of the tail as a bullwhip unlikely because of the potentially catastrophic muscle and skeletal damage such speeds could cause on the large and heavy tail. Instead, he proposes that the tails might have been used as a tactile organ to keep in touch with the individuals behind and on the sides in a group while migrating, which could have augmented cohesion and allowed communication among individuals while limiting more energetically demanding activities like stopping to search for dispersed individuals, turning to visually check on individuals behind, or communicating vocally.

Paleoecology

The

The Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

is a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments which, according to radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares t ...

, ranges between 156.3 million years old (Mya) at its base, and 146.8 Mya at the top, which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian

In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is an age in the Late Jurassic Epoch and a stage in the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxfordian ...

, and early Tithonian

In the geological timescale, the Tithonian is the latest age of the Late Jurassic Epoch and the uppermost stage of the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 152.1 ± 4 Ma and 145.0 ± 4 Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the K ...

stages

Stage or stages may refer to:

Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly British theatre newspaper

* S ...

of the Late Jurassic period. This formation is interpreted as a semiarid

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of semi-ar ...

environment with distinct wet and dry season

The dry season is a yearly period of low rainfall, especially in the tropics. The weather in the tropics is dominated by the tropical rain belt, which moves from the northern to the southern tropics and back over the course of the year. The te ...

s. The Morrison Basin, where dinosaurs lived, stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range

The Front Range is a mountain range of the Southern Rocky Mountains of North America located in the central portion of the U.S. State of Colorado, and southeastern portion of the U.S. State of Wyoming. It is the first mountain range encountere ...

of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, t ...

s were carried by streams and river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of wate ...

s and deposited in swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

y lowlands, lakes, river channels, and floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

s. This formation is similar in age to the Lourinha Formation in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and the Tendaguru Formation

The Tendaguru Formation, or Tendaguru Beds are a highly fossiliferous formation and Lagerstätte located in the Lindi Region of southeastern Tanzania. The formation represents the oldest sedimentary unit of the Mandawa Basin, overlying Neoproter ...

in Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

.

''Brontosaurus'' may have been a more solitary animal than other Morrison Formation dinosaurs. As a genus, ''Brontosaurus'' existed for a long span of time, and have been found in most levels of the Morrison. ''B. excelsus'' fossils have been reported from the upper Salt Wash Member to the upper Brushy Basin Member, ranging from the middle to late Kimmeridgian age, about 154–151 Mya. Additional remains are known from even younger rocks, but they have not been identified as any particular species. Older ''Brontosaurus'' remains have also been identified from the middle Kimmeridgian, and are assigned to ''B. parvus''. Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s of these animals have been found in Nine Mile Quarry and Bone Cabin Quarry

Bone Cabin Quarry is a dinosaur quarry that lay approximately northwest of Laramie, Wyoming near historic Como Bluff. During the summer of 1897 Walter Granger, a paleontologist from the American Museum of Natural History, came upon a hillside li ...

in Wyoming and at sites in Colorado, Oklahoma, and Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, present in stratigraphic zones 2–6.

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs. Dinosaurs known from the Morrison include the theropods ''Ceratosaurus

''Ceratosaurus'' (from Ancient Greek, Greek κέρας/κέρατος, ' meaning "horn" and wikt:σαῦρος, σαῦρος ' meaning "lizard") was a carnivorous Theropoda, theropod dinosaur in the Late Jurassic Period (geology), period (Kim ...

'', ''Ornitholestes

''Ornitholestes'' (meaning "bird robber") is a small theropod dinosaur of the late Jurassic (Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation, middle Kimmeridgian age, about 154 million years agoTurner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraph ...

'', and ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alluding to ...

'', the sauropods ''Apatosaurus'', ''Brachiosaurus'', ''Camarasaurus'', and ''Diplodocus'', and the ornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek s ...

ns ''Camptosaurus

''Camptosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of plant-eating, beaked ornithischian dinosaurs of the Late Jurassic period of western North America and possibly also Europe. The name means 'flexible lizard' (Greek (') meaning 'bent' and (') meaning 'lizard') ...

'', ''Dryosaurus

''Dryosaurus'' ( , meaning 'tree lizard', Greek ' () meaning 'tree, oak' and () meaning 'lizard'; the name reflects the forested habitat, not a vague oak-leaf shape of its cheek teeth as is sometimes assumed) is a genus of an ornithopod dinosaur ...

'', and ''Stegosaurus

''Stegosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of herbivorous, four-legged, armored dinosaur from the Late Jurassic, characterized by the distinctive kite-shaped upright plates along their backs and spikes on their tails. Fossils of the genus have been foun ...

''. Other vertebrates that shared this paleoenvironment included ray-finned fishes

Actinopterygii (; ), members of which are known as ray-finned fishes, is a class of bony fish. They comprise over 50% of living vertebrate species.

The ray-finned fishes are so called because their fins are webs of skin supported by bony or hor ...

, frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely Carnivore, carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order (biology), order Anura (ανοὐρά, literally ''without tail'' in Ancient Greek). The oldest fossil "proto-f ...

s, salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All ten ...

s, turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

s, sphenodonts, lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

s, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorpha

Crocodylomorpha is a group of pseudosuchian archosaurs that includes the crocodilians and their extinct relatives. They were the only members of Pseudosuchia to survive the end-Triassic extinction.

During Mesozoic and early Cenozoic times, cro ...

ns, and several species of pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s. Shells of bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

s and aquatic snail

A snail is, in loose terms, a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class Gastro ...

s are also common. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae

The green algae (singular: green alga) are a group consisting of the Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister which contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/Streptophyta. The land plants (Embryophytes) have emerged deep in the Charophyte alga as ...

, fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hor ...

es, horsetails

''Equisetum'' (; horsetail, snake grass, puzzlegrass) is the only living genus in Equisetaceae, a family of ferns, which reproduce by spores rather than seeds.

''Equisetum'' is a "living fossil", the only living genus of the entire subclass Eq ...

, cycad

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk (botany), trunk with a crown (botany), crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants o ...

s, ginkgo

''Ginkgo'' is a genus of non-flowering seed plants. The scientific name is also used as the English name. The order to which it belongs, Ginkgoales, first appeared in the Permian, 270 million years ago, and is now the only living genus within ...

es, and several families of conifer

Conifers are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single ...

s. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree fern

The tree ferns are arborescent (tree-like) ferns that grow with a trunk elevating the fronds above ground level, making them trees. Many extant tree ferns are members of the order Cyatheales, to which belong the families Cyatheaceae (scaly tree ...

s, and fern

A fern (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta ) is a member of a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. The polypodiophytes include all living pteridophytes except t ...

s (gallery forest

A gallery forest is one formed as a corridor along rivers or wetlands, projecting into landscapes that are otherwise only sparsely treed such as savannas, grasslands, or deserts. The gallery forest maintains a more temperate microclimate above th ...

s), to fern savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

s with occasional trees such as the ''Araucaria

''Araucaria'' (; original pronunciation: .ɾawˈka. ɾja is a genus of evergreen Conifer, coniferous trees in the family Araucariaceae. There are 20 extant taxon, extant species in New Caledonia (where 14 species are endemism, ende ...

''-like conifer ''Brachyphyllum

''Brachyphyllum'' (meaning "short leaf") is a form genus of fossil coniferous plant foliage. Plants of the genus have been variously assigned to several different conifer groups including Araucariaceae and Cheirolepidiaceae. They are known from ...

''.

In popular culture

The length of time taken for Riggs's 1903 reclassification of ''Brontosaurus'' as ''Apatosaurus'' to be brought to public notice, as well as Osborn's insistence that the ''Brontosaurus'' name be retained despite Riggs's paper, meant that the ''Brontosaurus'' became one of the most famous dinosaurs. ''Brontosaurus'' has often been depicted in cinema, beginning withWinsor McCay

Zenas Winsor McCay ( – July 26, 1934) was an American cartoonist and animator. He is best known for the comic strip ''Little Nemo'' (1905–14; 1924–26) and the animated film ''Gertie the Dinosaur'' (1914). For contractual reasons, he worke ...

's 1914 classic ''Gertie the Dinosaur

''Gertie the Dinosaur'' is a 1914 animated short film by American cartoonist and animator Winsor McCay. It is the earliest animated film to feature a dinosaur. McCay first used the film before live audiences as an interactive part of his vaude ...

'', one of the first animated films. McCay based his unidentified dinosaur on the apatosaurine skeleton in the American Museum of Natural History. The 1925 silent film ''The Lost World

The lost world is a subgenre of the fantasy or science fiction genres that involves the discovery of an unknown Earth civilization. It began as a subgenre of the late- Victorian adventure romance and remains popular into the 21st century.

The g ...

'' featured a battle between a ''Brontosaurus'' and an ''Allosaurus'', using special effect

Special effects (often abbreviated as SFX, F/X or simply FX) are illusions or visual tricks used in the theatre, film, television, video game, amusement park and simulator industries to simulate the imagined events in a story or virtual wor ...

s by Willis O'Brien

Willis Harold O'Brien (March 2, 1886 – November 8, 1962) was an American motion picture special effects and stop-motion animation pioneer, who according to ASIFA-Hollywood "was responsible for some of the best-known images in cinema history," ...

. The 1933 film ''King Kong

King Kong is a fictional giant monster resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. He has been dubbed The Eighth Wonder of the World, a phrase commonly used within the franchise. His first appearance was in the novelizat ...

'' featured a ''Brontosaurus'' chasing Carl Denham, Jack Driscoll and the terrified sailors on Skull Island. These, and other early uses of the animal as major representative of the group, helped cement ''Brontosaurus'' as a quintessential dinosaur in the public consciousness.

Sinclair Oil Corporation

Sinclair Oil Corporation was an American petroleum corporation, founded by Harry F. Sinclair on May 1, 1916, the Sinclair Oil and Refining Corporation combined, amalgamated, the assets of 11 small petroleum companies. Originally a New York cor ...

has long been a fixture of American roads (and briefly in other countries) with its green dinosaur logo and mascot, a ''Brontosaurus''. While Sinclair's early advertising included a number of different dinosaurs, eventually only ''Brontosaurus'' was used as the official logo, due to its popular appeal.

As late as 1989, the U.S. Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the U. ...

caused controversy when it issued four "dinosaur" stamps: ''Tyrannosaurus

''Tyrannosaurus'' is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' (''rex'' meaning "king" in Latin), often called ''T. rex'' or colloquially ''T-Rex'', is one of the best represented theropods. ''Tyrannosa ...

'', ''Stegosaurus'', ''Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (); from Ancient Greek (''pteron'', "wing") and (''anodon'', "toothless") is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of . They lived during the late Cr ...

'', and ''Brontosaurus''. The use of the term ''Brontosaurus'' in place of ''Apatosaurus'' led to complaints of "fostering scientific illiteracy." The Postal Service defended itself (in Postal Bulletin 21744) by saying, "Although now recognized by the scientific community as ''Apatosaurus'', the name ''Brontosaurus'' was used for the stamp because it is more familiar to the general population." Indeed, the Postal Service even implicitly rebuked the somewhat inconsistent complaints by adding that " milarly, the term 'dinosaur' has been used generically to describe all the animals .e., all four of the animals represented in the given stamp set even though the ''Pteranodon'' was a flying reptile ather than a true 'dinosaur'" a distinction left unmentioned in the numerous correspondence regarding the ''Brontosaurus''/''Apatosaurus'' issue. Palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould (; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Gould sp ...

supported this position. In the essay from which the title of the collection ''Bully for Brontosaurus

''Bully for Brontosaurus'' (1991) is the fifth volume of collected essays by the Harvard University, Harvard paleontology, paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. The essays were culled from his monthly column "This View of Life" in ''Natural History ( ...

'' is taken, Gould wrote: "Touché and right on; no one bitched about ''Pteranodon'', and that's a real error." His position, however, was not one suggesting the exclusive use of the popular name; he echoed Riggs' original argument that ''Brontosaurus'' is a synonym for ''Apatosaurus''. Nevertheless, he noted that the former has developed and continues to maintain an independent existence in the popular imagination.

The more vociferous denunciations of the usage have elicited sharply defensive statements from those who would not wish to see the name be struck from official usage. Tschopp's study has generated a very high number of responses from many, often opposed, groups – of editorial, news staff, and personal blog nature (both related and not), from both sides of the debate, from related and unrelated contexts, and from all over the world.

References

External links

* *Is Brontosaurus Back? (Youtube video, 11 minutes, 2015)

{{Portal bar, Dinosaurs, Paleontology, United States Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation Apatosaurinae Fossil taxa described in 1879 Articles containing video clips Taxa named by Othniel Charles Marsh Paleontology in Wyoming Paleontology in Utah Controversial dinosaur taxa Late Jurassic dinosaurs of North America