British Logistics In The Siegfried Line Campaign on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

British logistics supported the Anglo-Canadian

At the same time, preparations were also made for the possibility of a sudden breach of the German defences requiring a rapid exploitation. When the American

At the same time, preparations were also made for the possibility of a sudden breach of the German defences requiring a rapid exploitation. When the American

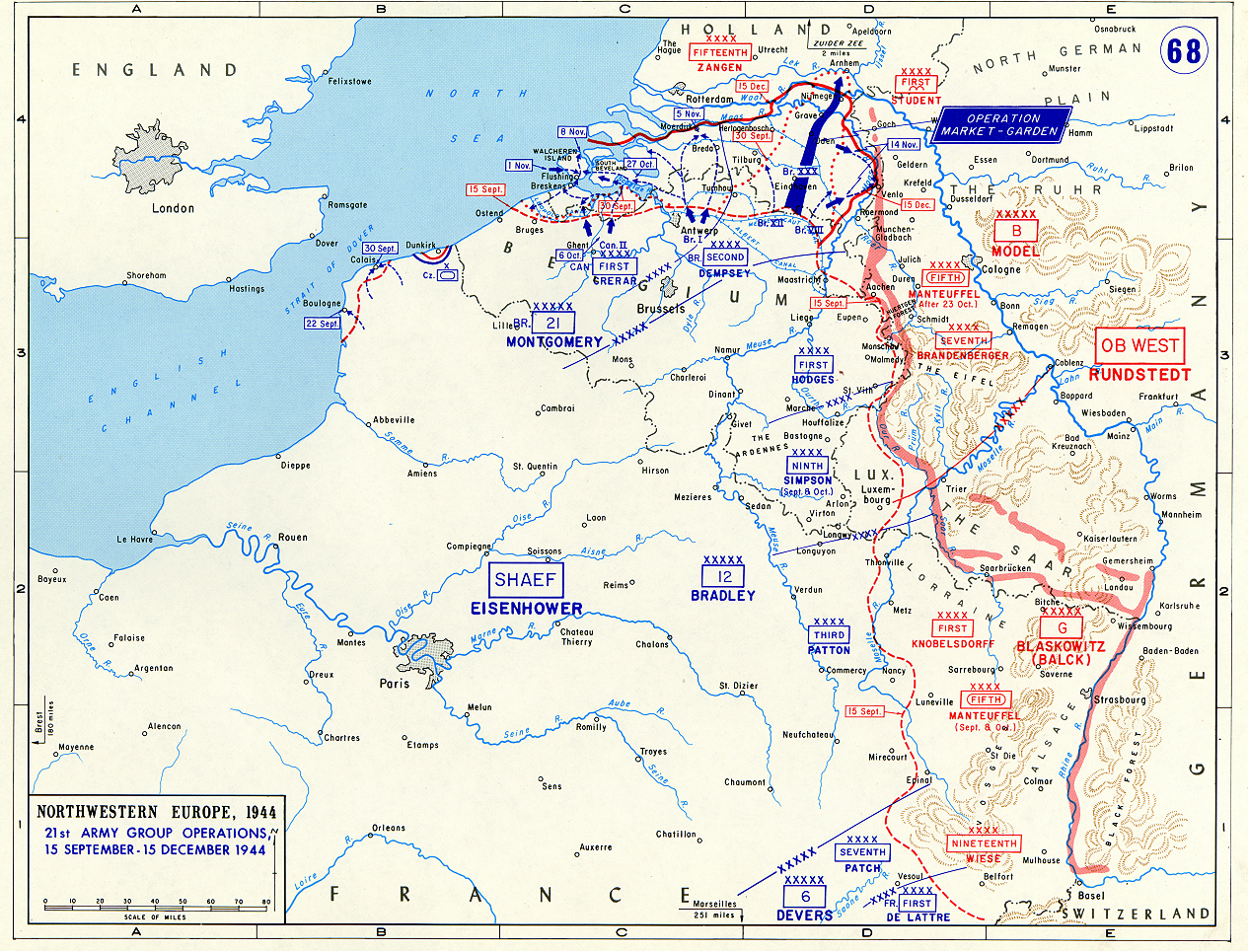

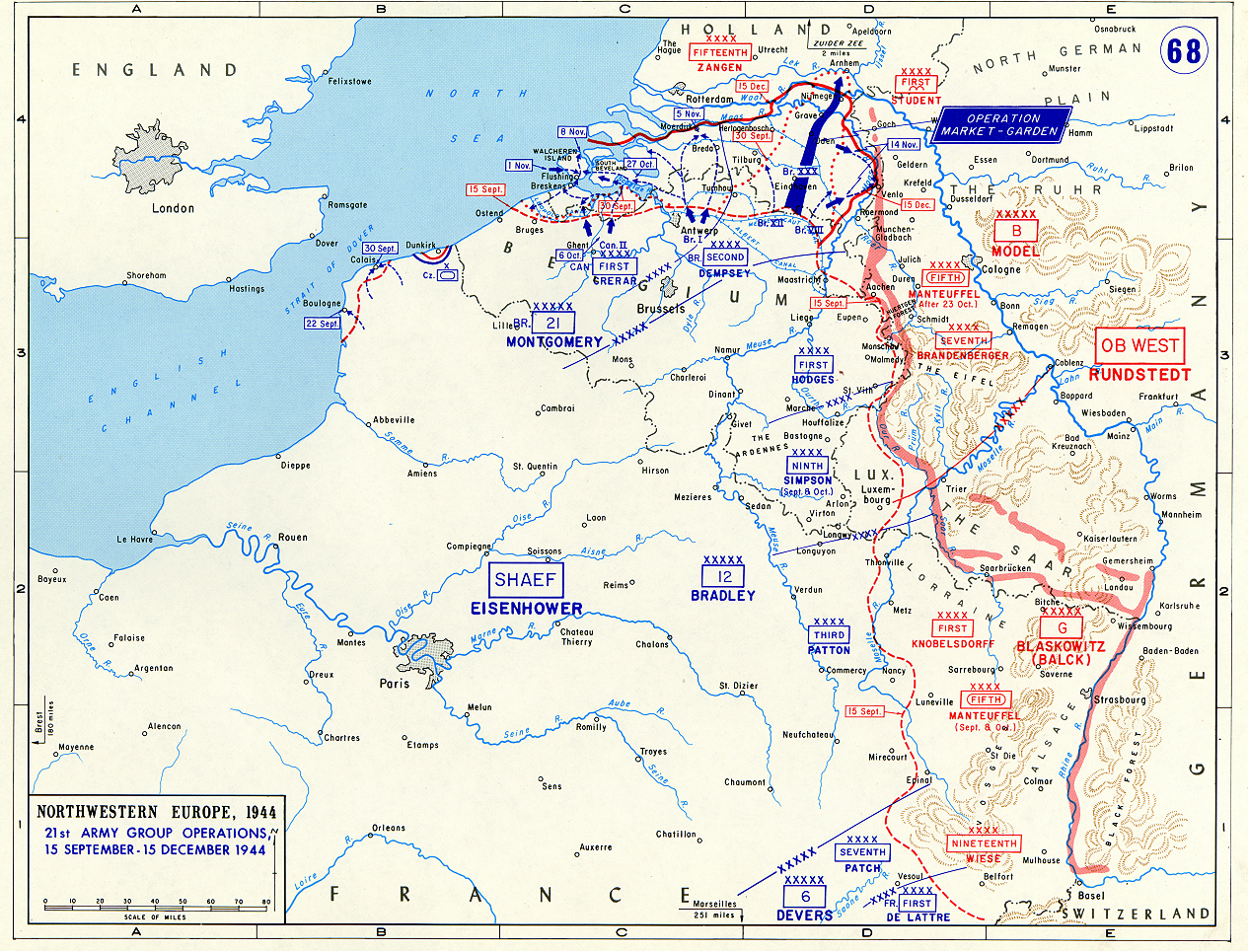

On 1 September, the Supreme Allied Commander, American

On 1 September, the Supreme Allied Commander, American  The Canadian Army did not have the manpower to manage its own

The Canadian Army did not have the manpower to manage its own

Montgomery intended to outflank the

Montgomery intended to outflank the

The second lift was supposed to depart the UK around 07:00 on 18 September, but was delayed for three hours by fog. Three General Aircraft Hamilcar gliders brought jeeps pre-loaded with ammunition and stores, but only two could be unloaded before German fire caused unloading work to cease. The divisional CRASC, Lieutenant Colonel Michael Packe arrived with his adjutant and nine soldiers, who would proceed to lay out the divisional administrative area (DAA) in front of the Airborne Museum 'Hartenstein', Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek. The resupply drop that coincided with the second lift delivered most of its stores to the predetermined supply dropping point (SDP) north of the Wolfheze railway line, which was in German hands, but some supplies were collected and transported to the DAA in captured German vehicles. Although no POL was collected, petrol pumps were found east of the DAA, allowing units to draw per vehicle using their own jerricans.

The parachutes used for supply drops were coloured to indicate the contents of their attached containers and paniers: red for ammunition, white for medical supplies, green for rations, blue for POL, yellow for signals equipment, and black for mail. The first major resupply drop was on 19 September, which was made at the prearranged SDP despite efforts to communicate alternatives. The supply effort involved 99 Stirlings and 63 Dakotas; 18 aircraft were lost. The same number flew the following day, although their departure was delayed by fog. This time 2,000 rations were collected, enough to provide about a third of the division's requirements, along with 330 rounds of 75 mm and 140 rounds of 6-pounder ammunition. This time fifteen aircraft were lost, of which eleven were Stirlings. On 21 September, American fighters based in England were supporting a bombing raid, and half the British fighters were grounded by inclement weather. The supply lift of 63 Stirlings and 63 Dakotas was attacked by German fighters, and 31 aircraft were lost. On the ground, 400 rounds of 75 mm and 170 rounds of 6-pounder ammunition was collected, but in four days only 24 rounds of 17-pounder ammunition had been retrieved.

Some resupply aircraft took off on 22 September, but were diverted to Brussels while in the air. The DAA was now under mortar fire, and some ammunition caught fire. A stack of 6-pounder shells exploded, but the fires were extinguished. Another resupply attempt was made on 23 September with 73 Stirlings and 55 Dakotas from the England and 18 aircraft from Brussels. This time 160 rounds of 75 mm and 80 rounds of 6-pounder ammunition was collected, but ammunition for the PIATs and Sten guns was critically short. There were now only a few serviceable jeeps and trailers available to distribute supplies. The resupply drop for 24 September was cancelled due to bad weather, although a drop was made near Grave, which was collected by the seaborne echelon. Most of its stock of 75mm and 6-pounder ammunition was handed over to the US 82nd Airborne Division after the 1st Airborne Division was evacuated from north of the Rhine on the night of 25/26 September.

The second lift was supposed to depart the UK around 07:00 on 18 September, but was delayed for three hours by fog. Three General Aircraft Hamilcar gliders brought jeeps pre-loaded with ammunition and stores, but only two could be unloaded before German fire caused unloading work to cease. The divisional CRASC, Lieutenant Colonel Michael Packe arrived with his adjutant and nine soldiers, who would proceed to lay out the divisional administrative area (DAA) in front of the Airborne Museum 'Hartenstein', Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek. The resupply drop that coincided with the second lift delivered most of its stores to the predetermined supply dropping point (SDP) north of the Wolfheze railway line, which was in German hands, but some supplies were collected and transported to the DAA in captured German vehicles. Although no POL was collected, petrol pumps were found east of the DAA, allowing units to draw per vehicle using their own jerricans.

The parachutes used for supply drops were coloured to indicate the contents of their attached containers and paniers: red for ammunition, white for medical supplies, green for rations, blue for POL, yellow for signals equipment, and black for mail. The first major resupply drop was on 19 September, which was made at the prearranged SDP despite efforts to communicate alternatives. The supply effort involved 99 Stirlings and 63 Dakotas; 18 aircraft were lost. The same number flew the following day, although their departure was delayed by fog. This time 2,000 rations were collected, enough to provide about a third of the division's requirements, along with 330 rounds of 75 mm and 140 rounds of 6-pounder ammunition. This time fifteen aircraft were lost, of which eleven were Stirlings. On 21 September, American fighters based in England were supporting a bombing raid, and half the British fighters were grounded by inclement weather. The supply lift of 63 Stirlings and 63 Dakotas was attacked by German fighters, and 31 aircraft were lost. On the ground, 400 rounds of 75 mm and 170 rounds of 6-pounder ammunition was collected, but in four days only 24 rounds of 17-pounder ammunition had been retrieved.

Some resupply aircraft took off on 22 September, but were diverted to Brussels while in the air. The DAA was now under mortar fire, and some ammunition caught fire. A stack of 6-pounder shells exploded, but the fires were extinguished. Another resupply attempt was made on 23 September with 73 Stirlings and 55 Dakotas from the England and 18 aircraft from Brussels. This time 160 rounds of 75 mm and 80 rounds of 6-pounder ammunition was collected, but ammunition for the PIATs and Sten guns was critically short. There were now only a few serviceable jeeps and trailers available to distribute supplies. The resupply drop for 24 September was cancelled due to bad weather, although a drop was made near Grave, which was collected by the seaborne echelon. Most of its stock of 75mm and 6-pounder ammunition was handed over to the US 82nd Airborne Division after the 1st Airborne Division was evacuated from north of the Rhine on the night of 25/26 September.

At the end of August, two port operating groups operated the Mulberry, Caen and Ouistreham, while the other four groups were withdrawn in preparation to deploying forward. The Canadian First Army had the mission of capturing the Channel ports. Rouen was captured by the Canadians on 30 August, and Le Tréport and Dieppe Operation Fusilade, were taken in an assault on 1 September. Although Dieppe's port facilities were almost intact, the approaches were extensively mined and several days of minesweeping were required; the first Coastal trading vessel, coaster docked there on 7 September. The rail link from Dieppe to Amiens was ready to accept traffic the day before. By the end of September, Dieppe had a capacity of per day. Le Tréport became a satellite port of Dieppe, and was used chiefly by the RAF for handling of awkward and bulky loads such as Queen Mary trailers with crashed aircraft, which were carried in Landing craft tank (LCTs). The port fell into disuse after Boulogne was opened.

A Operation Astonia, full-scale assault was required to capture Le Havre, and by the time the garrison surrendered on 12 September, the port was badly damaged. Unexpectedly, SHAEF allocated the port to the American forces. It was feared that this would create problems with the British and American lines of communications crossing each other, but the anticipated difficulties did not eventuate.

Boulogne Operation Wellhit, was captured on 22 September, but was badly damaged: most of the port equipment had been destroyed, and the harbour mouth was blocked by twenty-six sunken ships. The Royal Navy cleared a channel wide and deep, which permitted two coasters to get through on 12 October. Clearance of the wrecks was completed a month later, by which time the Royal Engineers had effected repairs to the quays to allow five coasters to berth. Thereafter, it handled a daily average of until early 1945, when it was handed over to the French. In its time under British control, the port received 9,000 personnel, 10,000 vehicles and of stores.

The German guns at Calais had to be silenced to facilitate the minesweeping operations to open Boulogne, so the port Operation Undergo, was captured on 29 September. SHAEF initially allocated the port to US control with the intention of developing landing ship, tank (LST), berths there for discharging vehicles, but the Communication Zone did not follow up on these plans, and when the 21st Army Group requested permission to use the railway terminal, SHAEF re-allocated it to British control on 23 October. It too was so badly damaged that repair work was initially confined to the construction of the railway terminal for LSTs equipped with rails and the ferry . The berthed on 21 November, and Calais became the major personnel reception port in the British sector. Stores were not discharged there until January, and the daily average was only around .

Ostend was captured on 9 September – the naval port party had to clear a passage through the fourteen wrecks that obstructed the harbour entrance. A channel wide and deep was cleared by 24 September, allowing coasters to enter the harbour the following day. Some quays were completely destroyed, but others were only damaged or obstructed by debris. These were cleared and repaired by the Royal Engineers. By the end of September the port had a capacity of of cargo daily, which rose to a day by the end of November, not counting bulk POL that was pumped ashore from tankers. A berth was lost when the SS ''Cedarwood'' was sunk in the harbour by a mine, but by November it was normally working three landing ships, infantry (LSIs), a hospital carrier, five LSTs and several coasters a day. Its turnaround time for coasters was days, which was faster than any other port in North West Europe.

The shipping available to the 21st Army Group in early September was limited by the inability of the recently-captured Channel Ports to handle vessels larger than coasters. The capacity of the ports was estimated at per day, but in practice no more than could be discharged daily. The coasters and landing ships had been in continuous use since D-Day, resulting in wear and tear. As the deteriorating autumn weather set in, an ever-increasing proportion were deadlined for repairs. Larger ships could still use the Mulberry harbour at Arromanches, but the RMA already held more stores than could be moved forward. A gale in early October caused considerable disruption to Mulberry operations. The two tombolas floating ship-to-shore lines at Port-en-Bessin were put out of action, and discharge of bulk POL there from tankers ceased. With the opening of Boulogne, two deep water berths became available. The port capacity available was sufficient to maintain the 21st Army Group and build up a small reserve, but not for major operations.

At the end of August, two port operating groups operated the Mulberry, Caen and Ouistreham, while the other four groups were withdrawn in preparation to deploying forward. The Canadian First Army had the mission of capturing the Channel ports. Rouen was captured by the Canadians on 30 August, and Le Tréport and Dieppe Operation Fusilade, were taken in an assault on 1 September. Although Dieppe's port facilities were almost intact, the approaches were extensively mined and several days of minesweeping were required; the first Coastal trading vessel, coaster docked there on 7 September. The rail link from Dieppe to Amiens was ready to accept traffic the day before. By the end of September, Dieppe had a capacity of per day. Le Tréport became a satellite port of Dieppe, and was used chiefly by the RAF for handling of awkward and bulky loads such as Queen Mary trailers with crashed aircraft, which were carried in Landing craft tank (LCTs). The port fell into disuse after Boulogne was opened.

A Operation Astonia, full-scale assault was required to capture Le Havre, and by the time the garrison surrendered on 12 September, the port was badly damaged. Unexpectedly, SHAEF allocated the port to the American forces. It was feared that this would create problems with the British and American lines of communications crossing each other, but the anticipated difficulties did not eventuate.

Boulogne Operation Wellhit, was captured on 22 September, but was badly damaged: most of the port equipment had been destroyed, and the harbour mouth was blocked by twenty-six sunken ships. The Royal Navy cleared a channel wide and deep, which permitted two coasters to get through on 12 October. Clearance of the wrecks was completed a month later, by which time the Royal Engineers had effected repairs to the quays to allow five coasters to berth. Thereafter, it handled a daily average of until early 1945, when it was handed over to the French. In its time under British control, the port received 9,000 personnel, 10,000 vehicles and of stores.

The German guns at Calais had to be silenced to facilitate the minesweeping operations to open Boulogne, so the port Operation Undergo, was captured on 29 September. SHAEF initially allocated the port to US control with the intention of developing landing ship, tank (LST), berths there for discharging vehicles, but the Communication Zone did not follow up on these plans, and when the 21st Army Group requested permission to use the railway terminal, SHAEF re-allocated it to British control on 23 October. It too was so badly damaged that repair work was initially confined to the construction of the railway terminal for LSTs equipped with rails and the ferry . The berthed on 21 November, and Calais became the major personnel reception port in the British sector. Stores were not discharged there until January, and the daily average was only around .

Ostend was captured on 9 September – the naval port party had to clear a passage through the fourteen wrecks that obstructed the harbour entrance. A channel wide and deep was cleared by 24 September, allowing coasters to enter the harbour the following day. Some quays were completely destroyed, but others were only damaged or obstructed by debris. These were cleared and repaired by the Royal Engineers. By the end of September the port had a capacity of of cargo daily, which rose to a day by the end of November, not counting bulk POL that was pumped ashore from tankers. A berth was lost when the SS ''Cedarwood'' was sunk in the harbour by a mine, but by November it was normally working three landing ships, infantry (LSIs), a hospital carrier, five LSTs and several coasters a day. Its turnaround time for coasters was days, which was faster than any other port in North West Europe.

The shipping available to the 21st Army Group in early September was limited by the inability of the recently-captured Channel Ports to handle vessels larger than coasters. The capacity of the ports was estimated at per day, but in practice no more than could be discharged daily. The coasters and landing ships had been in continuous use since D-Day, resulting in wear and tear. As the deteriorating autumn weather set in, an ever-increasing proportion were deadlined for repairs. Larger ships could still use the Mulberry harbour at Arromanches, but the RMA already held more stores than could be moved forward. A gale in early October caused considerable disruption to Mulberry operations. The two tombolas floating ship-to-shore lines at Port-en-Bessin were put out of action, and discharge of bulk POL there from tankers ceased. With the opening of Boulogne, two deep water berths became available. The port capacity available was sufficient to maintain the 21st Army Group and build up a small reserve, but not for major operations.

During Operation Market Garden, No. 161 FMC at Bourg-Leopold had expanded beyond the size of a normal FMC, and a great deal of US Army supplies had been accumulated, which now had to be disposed of. Second Army took it over as the basis of a new army roadhead, No. 8 Army Roadhead. As one of the Belgian pre-war military centres it contained suitable accommodation and was well served by road and railway communications. The roads in the area were straight with wide road verges, which made them ideal for roadside stacking of stores, and was also well-placed to support the Second Army's ongoing operations. Its only drawback was a shortage of covered storage space, so supplies often had to be stored in the open. Stocking of the new roadhead commenced on 4 October, and was largely done by rail.

During Operation Infatuate, the operations on Walcheren Island to open Antwerp, British commandos captured Vlissingen, Flushing on 4 November, bringing both sides of the Scheldt under Allied control. An attempt had already been made to commence minesweeping two days earlier but three of the minesweepers had been hit by guns at Zeebrugge, and the attempt had been abandoned. Zeebrugge was in Canadian hands the following day, and minesweepers from Ostend reached Breskens. Minesweeping operations commenced on 4 November, with ten flotillas engaged. Fifty mines were swept on the first day, and six minesweepers made their way to Antwerp. Thereafter, sweeping operations continued from both ends of the Scheldt. One minesweeper was lost with all hands, but on 26 November the naval officer in charge of the minesweeping effort, Captain (Royal Navy), Captain H. G. Hopper, announced that sweeping operations were complete.

The port of Antwerp was opened to coasters that day and to deep-Draft (hull), draught shipping on 28 November. The first ship to berth was Canadian-built . The quays were cleared of obstructions and the Kruisschans Lock was repaired by December. Antwerp could receive shipping not just from the UK, but directly from the United States and the Middle East. The first order placed for direct shipment from the United States was for of flour, sugar, dried fruit, condensed milk, powdered eggs and luncheon meat, to arrive in January 1945. Subsequent orders were for flour and meat only, as sufficient stocks of the other goods were held in the UK to sustain the 21st Army Group for six months. The first ocean-going reefer ship, refrigerated vessel docked at Antwerp on 2 December 1944, and daily issues of fresh meat from South America became possible, although transhipment via the UK was still sometimes necessary.

During Operation Market Garden, No. 161 FMC at Bourg-Leopold had expanded beyond the size of a normal FMC, and a great deal of US Army supplies had been accumulated, which now had to be disposed of. Second Army took it over as the basis of a new army roadhead, No. 8 Army Roadhead. As one of the Belgian pre-war military centres it contained suitable accommodation and was well served by road and railway communications. The roads in the area were straight with wide road verges, which made them ideal for roadside stacking of stores, and was also well-placed to support the Second Army's ongoing operations. Its only drawback was a shortage of covered storage space, so supplies often had to be stored in the open. Stocking of the new roadhead commenced on 4 October, and was largely done by rail.

During Operation Infatuate, the operations on Walcheren Island to open Antwerp, British commandos captured Vlissingen, Flushing on 4 November, bringing both sides of the Scheldt under Allied control. An attempt had already been made to commence minesweeping two days earlier but three of the minesweepers had been hit by guns at Zeebrugge, and the attempt had been abandoned. Zeebrugge was in Canadian hands the following day, and minesweepers from Ostend reached Breskens. Minesweeping operations commenced on 4 November, with ten flotillas engaged. Fifty mines were swept on the first day, and six minesweepers made their way to Antwerp. Thereafter, sweeping operations continued from both ends of the Scheldt. One minesweeper was lost with all hands, but on 26 November the naval officer in charge of the minesweeping effort, Captain (Royal Navy), Captain H. G. Hopper, announced that sweeping operations were complete.

The port of Antwerp was opened to coasters that day and to deep-Draft (hull), draught shipping on 28 November. The first ship to berth was Canadian-built . The quays were cleared of obstructions and the Kruisschans Lock was repaired by December. Antwerp could receive shipping not just from the UK, but directly from the United States and the Middle East. The first order placed for direct shipment from the United States was for of flour, sugar, dried fruit, condensed milk, powdered eggs and luncheon meat, to arrive in January 1945. Subsequent orders were for flour and meat only, as sufficient stocks of the other goods were held in the UK to sustain the 21st Army Group for six months. The first ocean-going reefer ship, refrigerated vessel docked at Antwerp on 2 December 1944, and daily issues of fresh meat from South America became possible, although transhipment via the UK was still sometimes necessary.

Antwerp had of quays, which were located along the river and in eighteen wet basins (docks open to the water). They were equipped with over 600 hydraulic and electric cranes, and there were also floating cranes and grain elevators. There were 900 warehouses, a granary capable of storing nearly and of cold storage. Petroleum pipelines ran from the tanker berths to 498 storage tanks with a capacity of . Labour to work the port was plentiful, and it was well-served by roads, railway and canals for barge traffic. There were of railway lines that connected to the Belgian railway system, and there was access to inland waterways, including the Albert Canal, which connected to the Meuse River. Although the port area was only lightly damaged, the Germans had removed of railway track and 200 railroad switch, points and Swingnose crossing, crossings, and the marshalling yards had been damaged by artillery and mortar fire. To handle dredging, a Scheldt Dredging Control organisation was established; its work involved coordinating military requirements with longer-term civilian policy. Some of silt was dredged between 2 November 1944 and 31 January 1945.

SHAEF decreed that Antwerp would handle both American and British supplies, under British direction. For this purpose, a special combined American and British staff was created in the Q (Movements) Branch at 21st Army Group Headquarters, and a Memorandum of Agreement known as the "Charter of Antwerp" was drawn up and signed by Graham and US Colonel Fenton S. Jacobs, the commander of the Communication Zone's Channel Base Section. Overall command of the port was vested in the Royal Navy Naval Officer in Charge (NOIC), Captain Cowley Thomas, who also chaired a port executive committee on which both American and British interests were represented. Local administration was the responsibility of the British base sub area commander. US forces were allocated primary rights to the roads and railway lines leading south east to Liège, while the British were given those leading to the north and north east. A joint US, British and Belgian Movements Organization for Transport (BELMOT) was created to coordinate highway, railway and waterway traffic. A tonnage discharge target of per day was set, of which was British and was American. This was not counting bulk POL, for which there was sufficient capacity for both. However, Antwerp was not an ideal base port; in peacetime it had been a transit port, and it lacked warehouse and factory space. The lack of warehouse space meant that when congestion occurred it was very difficult to clear. The surrounding area soon became crowded with dumps and depots.

Antwerp had of quays, which were located along the river and in eighteen wet basins (docks open to the water). They were equipped with over 600 hydraulic and electric cranes, and there were also floating cranes and grain elevators. There were 900 warehouses, a granary capable of storing nearly and of cold storage. Petroleum pipelines ran from the tanker berths to 498 storage tanks with a capacity of . Labour to work the port was plentiful, and it was well-served by roads, railway and canals for barge traffic. There were of railway lines that connected to the Belgian railway system, and there was access to inland waterways, including the Albert Canal, which connected to the Meuse River. Although the port area was only lightly damaged, the Germans had removed of railway track and 200 railroad switch, points and Swingnose crossing, crossings, and the marshalling yards had been damaged by artillery and mortar fire. To handle dredging, a Scheldt Dredging Control organisation was established; its work involved coordinating military requirements with longer-term civilian policy. Some of silt was dredged between 2 November 1944 and 31 January 1945.

SHAEF decreed that Antwerp would handle both American and British supplies, under British direction. For this purpose, a special combined American and British staff was created in the Q (Movements) Branch at 21st Army Group Headquarters, and a Memorandum of Agreement known as the "Charter of Antwerp" was drawn up and signed by Graham and US Colonel Fenton S. Jacobs, the commander of the Communication Zone's Channel Base Section. Overall command of the port was vested in the Royal Navy Naval Officer in Charge (NOIC), Captain Cowley Thomas, who also chaired a port executive committee on which both American and British interests were represented. Local administration was the responsibility of the British base sub area commander. US forces were allocated primary rights to the roads and railway lines leading south east to Liège, while the British were given those leading to the north and north east. A joint US, British and Belgian Movements Organization for Transport (BELMOT) was created to coordinate highway, railway and waterway traffic. A tonnage discharge target of per day was set, of which was British and was American. This was not counting bulk POL, for which there was sufficient capacity for both. However, Antwerp was not an ideal base port; in peacetime it had been a transit port, and it lacked warehouse and factory space. The lack of warehouse space meant that when congestion occurred it was very difficult to clear. The surrounding area soon became crowded with dumps and depots.

Although damage to the port and its environs was minor, Antwerp repeatedly failed to meet its tonnage targets. This was mainly attributable to insufficient warehouse space, a shortage of railway rolling stock, and delays in opening the Albert Canal to barge traffic. The canal was supposed to open on 15 December, but clearing away obstructions, particularly the demolished Yserburg Bridge at the entrance, delayed its opening until 28 December, by which time a backlog of 198 loaded barges had accumulated. Temporary lighting was supplied to the Antwerp quays and dumps in December to allow the port to be worked around the clock. Twenty-one lighting sets were made by mounting a 3 kW 3-phase electric generator on a bogie with a platform on which six floodlights were installed.

Another cause of difficulties at Antwerp was German V-weapons attacks, which began on 1 October. This had a serious impact on the availability of civilian labour, and military labour had to be brought in. Nonetheless, the number of civilians employed at the port rose from 7,652 in early December 1944 to over 14,000 in January 1945. Whenever possible, US Army stores were moved directly from the quays to depots maintained by the Communications Zone around Liège and Namur, but these too were frequent targets of V-weapons.

By the end of the year, 994 V-2 rocket and 5,097 V-1 flying bomb attacks had been made against continental targets, resulting in 792 military personnel killed and 993 wounded, and 2,219 deaths and 4,493 serious injuries to civilians. The worst carnage in a single attack occurred on 16 December when the Cine Rex in Brussels was hit by a V-2 rocket and 567 people were killed. Four berths at the port were damaged in an attack on 24 December, and the sluice gate at the entrance from the Scheldt was damaged, thereby increasing the locking time by eight minutes. Two large cargo ships and 58 smaller vessels were sunk between September 1944 and March 1945, and there was damage to the roads, railways, cranes and quays, but not enough to seriously impact the functioning of the port.

E-boats made several attempts to disrupt convoys sailing to Antwerp, but the convoys were escorted by destroyers that drove them off, and RAF Bomber Command attacked their bases at IJmuiden and Rotterdam in December. In the first three months of 1945, torpedoes from E-boats sank of Allied shipping, and mines laid by them sank more. midget submarines accounted for another of sunken ships. Also dangerous was aerial mining, as the sinking of a single large vessel in the Scheldt could have halted traffic in both directions for days. A major German aerial mining effort was made on 23 January 1945, with 36 mines being swept over the following five days, but this turned out to be the last minelaying mission directed against Antwerp.

Although damage to the port and its environs was minor, Antwerp repeatedly failed to meet its tonnage targets. This was mainly attributable to insufficient warehouse space, a shortage of railway rolling stock, and delays in opening the Albert Canal to barge traffic. The canal was supposed to open on 15 December, but clearing away obstructions, particularly the demolished Yserburg Bridge at the entrance, delayed its opening until 28 December, by which time a backlog of 198 loaded barges had accumulated. Temporary lighting was supplied to the Antwerp quays and dumps in December to allow the port to be worked around the clock. Twenty-one lighting sets were made by mounting a 3 kW 3-phase electric generator on a bogie with a platform on which six floodlights were installed.

Another cause of difficulties at Antwerp was German V-weapons attacks, which began on 1 October. This had a serious impact on the availability of civilian labour, and military labour had to be brought in. Nonetheless, the number of civilians employed at the port rose from 7,652 in early December 1944 to over 14,000 in January 1945. Whenever possible, US Army stores were moved directly from the quays to depots maintained by the Communications Zone around Liège and Namur, but these too were frequent targets of V-weapons.

By the end of the year, 994 V-2 rocket and 5,097 V-1 flying bomb attacks had been made against continental targets, resulting in 792 military personnel killed and 993 wounded, and 2,219 deaths and 4,493 serious injuries to civilians. The worst carnage in a single attack occurred on 16 December when the Cine Rex in Brussels was hit by a V-2 rocket and 567 people were killed. Four berths at the port were damaged in an attack on 24 December, and the sluice gate at the entrance from the Scheldt was damaged, thereby increasing the locking time by eight minutes. Two large cargo ships and 58 smaller vessels were sunk between September 1944 and March 1945, and there was damage to the roads, railways, cranes and quays, but not enough to seriously impact the functioning of the port.

E-boats made several attempts to disrupt convoys sailing to Antwerp, but the convoys were escorted by destroyers that drove them off, and RAF Bomber Command attacked their bases at IJmuiden and Rotterdam in December. In the first three months of 1945, torpedoes from E-boats sank of Allied shipping, and mines laid by them sank more. midget submarines accounted for another of sunken ships. Also dangerous was aerial mining, as the sinking of a single large vessel in the Scheldt could have halted traffic in both directions for days. A major German aerial mining effort was made on 23 January 1945, with 36 mines being swept over the following five days, but this turned out to be the last minelaying mission directed against Antwerp.

An FMC normally held two days' rations, one days' maintenance, two or three days' supply of petrol (about ) and of ammunition. Each corps had two corps troops composite companies and a corps transport company. Between them they had 222 3-ton () lorries, 12 10-ton () lorries and 36 dump truck, tippers. The tippers were never available for general duties, as they were continuously employed on construction tasks by the Royal Engineers. The normal daily requirement of a corps was , of which the corps transport had to lift . The corps' transport resources were inadequate and had to supplemented by borrowing lorries from the armies or the divisions.

With one exception, the infantry divisions of the 21st Army Group reorganised their transport on a commodity basis, with one company for supplies, one for POL, one for artillery ammunition and one for other kinds of ammunition. The armoured divisions, again with one exception, organised theirs with one company less one platoon for supplies, one plus a platoon for POL, one for ammunition and one for troop transport. Organisation by commodities was found to simplify transport arrangements and make it easier to supply lorries for use by the corps or for troop transport when required. Doctrine called for vehicles to be kept loaded when possible, providing a reserve on wheels but with Allied air supremacy, this was no longer necessary and the priority switched to dumping supplies and keeping the transport occupied.

Several expedients were used to increase the capacity of the road transport system. The First Canadian Army converted a tank transporter trailer into a load carrier by welding pierced steel plank onto it to give it a floor and sides. Second Army HQ was sufficiently impressed to order the conversion of a company of tank transporters. Modified this way, a tank transporter could haul of supplies, of ammunition or of POL. These could carry a considerable amount in a convoy of reasonable length, but careful traffic control was required to ensure that they avoided narrow roads. Additional vehicles were allocated to transport companies with sufficient drivers, two 10-ton general transport companies were issued with 5-ton trailers, and eight DUKW companies were re-equipped with regular 3-ton lorries. This left only three DUKW companies, one of which was on loan to the US Army. One 6-ton and two 3-ton general transport companies that had also been loaned to the US Army in August were returned on 4 September. Eight additional transport platoons were formed from the transport of anti-aircraft units.

An FMC normally held two days' rations, one days' maintenance, two or three days' supply of petrol (about ) and of ammunition. Each corps had two corps troops composite companies and a corps transport company. Between them they had 222 3-ton () lorries, 12 10-ton () lorries and 36 dump truck, tippers. The tippers were never available for general duties, as they were continuously employed on construction tasks by the Royal Engineers. The normal daily requirement of a corps was , of which the corps transport had to lift . The corps' transport resources were inadequate and had to supplemented by borrowing lorries from the armies or the divisions.

With one exception, the infantry divisions of the 21st Army Group reorganised their transport on a commodity basis, with one company for supplies, one for POL, one for artillery ammunition and one for other kinds of ammunition. The armoured divisions, again with one exception, organised theirs with one company less one platoon for supplies, one plus a platoon for POL, one for ammunition and one for troop transport. Organisation by commodities was found to simplify transport arrangements and make it easier to supply lorries for use by the corps or for troop transport when required. Doctrine called for vehicles to be kept loaded when possible, providing a reserve on wheels but with Allied air supremacy, this was no longer necessary and the priority switched to dumping supplies and keeping the transport occupied.

Several expedients were used to increase the capacity of the road transport system. The First Canadian Army converted a tank transporter trailer into a load carrier by welding pierced steel plank onto it to give it a floor and sides. Second Army HQ was sufficiently impressed to order the conversion of a company of tank transporters. Modified this way, a tank transporter could haul of supplies, of ammunition or of POL. These could carry a considerable amount in a convoy of reasonable length, but careful traffic control was required to ensure that they avoided narrow roads. Additional vehicles were allocated to transport companies with sufficient drivers, two 10-ton general transport companies were issued with 5-ton trailers, and eight DUKW companies were re-equipped with regular 3-ton lorries. This left only three DUKW companies, one of which was on loan to the US Army. One 6-ton and two 3-ton general transport companies that had also been loaned to the US Army in August were returned on 4 September. Eight additional transport platoons were formed from the transport of anti-aircraft units.

In response to an urgent request from 21st Army Group on 3 September, two transport companies were formed from the Anti-Aircraft Command and two from the War Office Airfields Transport Column, and shipped within six days. A second urgent request was received on 15 September. The War Office agreed to loan 21st Army Group an additional twelve transport companies with a combined lift of . They were drawn from the Anti-Aircraft Command and Command Mixed Transport units. Five companies arrived by 26 September. Five of them came pre-loaded with petrol, five with supplies, and two came empty. To control them, three new transport column HQs were formed in the UK and sent as well.

On 19 September, 21st Army Group HQ assumed control of transport through an organisation called TRANCO. Two CRASCs were assigned to the area north of the Seine and two to the south. In each area, one was responsible for the road patrol and staging camps, and the other, known as "control", reported on the location and availability of transport. Loading bills were sent out daily by telephone or radio 48-hours in advance. Road and railway traffic became more routine during October, and TRANCO was abolished at the end of the month. However, until the railway bridge at Ravenstein, Netherlands, Ravenstein was repaired in December, the support of the British Second Army's operations to the south east of Nijmegen was still by road.

To economise on manpower and release RASC personnel to become infantry reinforcements, the RASC motor transport units were reorganised in October. Sixteen army transport companies were reorganised as sixteen 3-ton or 6-ton general transport companies with four platoons each, although they retained their original designations. The bulk petrol transport companies were reorganised from six companies with four platoons into eight companies with three platoons. Each platoon operated thirty vehicles.

In November, Belgian Army units were formed into transport companies. After training in the UK, they took over the equipment of the seventeen companies loaned by the War Office, whose personnel were then returned to the UK for retraining and further service in South East Asia. This transport pool was directly controlled by the 21st Army Group headquarters, although it was administered by the Belgian government.

To give the general transport companies some much-needed time for rest and maintenance, captured German horses, wagons and saddlery were pressed into service. These were supplemented by hired and requisitioned Belgian civilian animal transport. In the first half of December, was moved by animal transport, mostly in the Antwerp area.

The major contributor to deterioration of the roads was running two-way traffic down narrow roads. Vehicles running with wheels on the verges caused rutting of the verges, which in turn caused damage to the road haunches. Once these were broken, the carriageway surface started to break up. In places where there were no trees to prevent driving on the verges, thousands of wooden pickets were driven into the ground. Stone for road repair was drawn from Porphyry (geology), porphyry rock quarries at Lessines, and , and of slag suitable for making pitch (resin), pitch was obtained from the zinc works at Neerpelt. In January 1945, the RE Quarrying Group produced of stone.

In response to an urgent request from 21st Army Group on 3 September, two transport companies were formed from the Anti-Aircraft Command and two from the War Office Airfields Transport Column, and shipped within six days. A second urgent request was received on 15 September. The War Office agreed to loan 21st Army Group an additional twelve transport companies with a combined lift of . They were drawn from the Anti-Aircraft Command and Command Mixed Transport units. Five companies arrived by 26 September. Five of them came pre-loaded with petrol, five with supplies, and two came empty. To control them, three new transport column HQs were formed in the UK and sent as well.

On 19 September, 21st Army Group HQ assumed control of transport through an organisation called TRANCO. Two CRASCs were assigned to the area north of the Seine and two to the south. In each area, one was responsible for the road patrol and staging camps, and the other, known as "control", reported on the location and availability of transport. Loading bills were sent out daily by telephone or radio 48-hours in advance. Road and railway traffic became more routine during October, and TRANCO was abolished at the end of the month. However, until the railway bridge at Ravenstein, Netherlands, Ravenstein was repaired in December, the support of the British Second Army's operations to the south east of Nijmegen was still by road.

To economise on manpower and release RASC personnel to become infantry reinforcements, the RASC motor transport units were reorganised in October. Sixteen army transport companies were reorganised as sixteen 3-ton or 6-ton general transport companies with four platoons each, although they retained their original designations. The bulk petrol transport companies were reorganised from six companies with four platoons into eight companies with three platoons. Each platoon operated thirty vehicles.

In November, Belgian Army units were formed into transport companies. After training in the UK, they took over the equipment of the seventeen companies loaned by the War Office, whose personnel were then returned to the UK for retraining and further service in South East Asia. This transport pool was directly controlled by the 21st Army Group headquarters, although it was administered by the Belgian government.

To give the general transport companies some much-needed time for rest and maintenance, captured German horses, wagons and saddlery were pressed into service. These were supplemented by hired and requisitioned Belgian civilian animal transport. In the first half of December, was moved by animal transport, mostly in the Antwerp area.

The major contributor to deterioration of the roads was running two-way traffic down narrow roads. Vehicles running with wheels on the verges caused rutting of the verges, which in turn caused damage to the road haunches. Once these were broken, the carriageway surface started to break up. In places where there were no trees to prevent driving on the verges, thousands of wooden pickets were driven into the ground. Stone for road repair was drawn from Porphyry (geology), porphyry rock quarries at Lessines, and , and of slag suitable for making pitch (resin), pitch was obtained from the zinc works at Neerpelt. In January 1945, the RE Quarrying Group produced of stone.

It was imperative to get the railway system operational again as soon as possible. The most pressing problem was the destruction of bridges, particularly those over the Seine. In northern France however, the devastation was less widespread, and rehabilitation was faster than south of the Seine. This work was carried out by British Army, civilian and POW workers. Commencing on 10 September, stores from the RMA began moving forward to railheads around Bernay, Eure, Bernay. Lorries then took them across the Seine to the Beauvais area, where they were loaded back on trains and taken to railheads south of Brussels serving No. 6 Army Roadhead. On 8 September, work commenced on bridging the Seine. A new railway bridge at Le Manoir, Eure, Le Manoir was completed on 22 September, allowing trains to cross the Seine. Two bridges across the Somme were still down, but by making a diversion around Doullens, trains could reach Brussels. In November and December, the Seine rose to its highest level since 1910, and the current ran at . There were fears for the bridge at Le Manoir as the waters rose almost to the level of the rails, but the bridge remained standing.

While the US Army had its own railway operating units, the British forces were dependent on the French and Belgian railway authorities to operate the Amiens-Lille-Brussels line. In return for military assistance in restoring the rail network, the local authorities accepted that military traffic had priority over civilian. France had around 12,000 locomotives before the war, but only about 2,000 were serviceable by September 1944. With some quick repairs, it was possible to raise this to 6,000; but it was still necessary to import British-built Hunslet Austerity 0-6-0ST, War Department Austerity 0-6-0ST, WD Austerity 2-8-0, 2-8-0 and WD Austerity 2-10-0, 2-10-0 locomotives to supplement them. Plans called for a thousand engines to be brought across, of which 900 were to be 2-8-0s. Their delivery was slow, owing to the SHAEF's inadequate allocation of locomotives and rolling stock on the British account at Cherbourg, the only port that could receive them. This limitation was overcome when Dieppe was opened as a railway ferry terminal on 28 September. By the end of November 150 locomotives had been landed at Dieppe and Ostend using LSTs that had been specially fitted with rails to allow them to be driven on and off. Calais also began receiving rolling stock on 21 November.

It was imperative to get the railway system operational again as soon as possible. The most pressing problem was the destruction of bridges, particularly those over the Seine. In northern France however, the devastation was less widespread, and rehabilitation was faster than south of the Seine. This work was carried out by British Army, civilian and POW workers. Commencing on 10 September, stores from the RMA began moving forward to railheads around Bernay, Eure, Bernay. Lorries then took them across the Seine to the Beauvais area, where they were loaded back on trains and taken to railheads south of Brussels serving No. 6 Army Roadhead. On 8 September, work commenced on bridging the Seine. A new railway bridge at Le Manoir, Eure, Le Manoir was completed on 22 September, allowing trains to cross the Seine. Two bridges across the Somme were still down, but by making a diversion around Doullens, trains could reach Brussels. In November and December, the Seine rose to its highest level since 1910, and the current ran at . There were fears for the bridge at Le Manoir as the waters rose almost to the level of the rails, but the bridge remained standing.

While the US Army had its own railway operating units, the British forces were dependent on the French and Belgian railway authorities to operate the Amiens-Lille-Brussels line. In return for military assistance in restoring the rail network, the local authorities accepted that military traffic had priority over civilian. France had around 12,000 locomotives before the war, but only about 2,000 were serviceable by September 1944. With some quick repairs, it was possible to raise this to 6,000; but it was still necessary to import British-built Hunslet Austerity 0-6-0ST, War Department Austerity 0-6-0ST, WD Austerity 2-8-0, 2-8-0 and WD Austerity 2-10-0, 2-10-0 locomotives to supplement them. Plans called for a thousand engines to be brought across, of which 900 were to be 2-8-0s. Their delivery was slow, owing to the SHAEF's inadequate allocation of locomotives and rolling stock on the British account at Cherbourg, the only port that could receive them. This limitation was overcome when Dieppe was opened as a railway ferry terminal on 28 September. By the end of November 150 locomotives had been landed at Dieppe and Ostend using LSTs that had been specially fitted with rails to allow them to be driven on and off. Calais also began receiving rolling stock on 21 November.

Rolling stock was only part of the problem; the railway operators had to contend with damaged tracks, depleted staff and a non-operational telephone system. Rounding up enough locomotives for the day's work might involve visits to half a dozen marshalling yards by an official on a bicycle. Coordination of the system was the responsibility of the Q (Movements) Branch at 21st Army Group Headquarters. Rehabilitation of the railway system in that part of the Netherlands in Allied hands involved the reconstruction of bridges over the many rivers and canals. The Germans had demolished almost all the railway bridges, and most involved spans of over . By 6 October, the line had reached Eindhoven.

The Americans assumed responsibility for all rail traffic west of Liseux on 23 October. Nineteen bridges, six of which were double-track, were opened in November, and work was under way on twenty-two more. No less than of bridging was erected during the month. By the end of the year, 75 railway bridges consisting of 202 spans were partly or completely rebuilt, most of the repairs to the Antwerp marshalling yards were complete, and with the completion of the bridge at 's-Hertogenbosch, trains were running from Antwerp to railheads at Ravenstein and Mill, North Brabant, Mill, just from the front line.

Rolling stock was only part of the problem; the railway operators had to contend with damaged tracks, depleted staff and a non-operational telephone system. Rounding up enough locomotives for the day's work might involve visits to half a dozen marshalling yards by an official on a bicycle. Coordination of the system was the responsibility of the Q (Movements) Branch at 21st Army Group Headquarters. Rehabilitation of the railway system in that part of the Netherlands in Allied hands involved the reconstruction of bridges over the many rivers and canals. The Germans had demolished almost all the railway bridges, and most involved spans of over . By 6 October, the line had reached Eindhoven.

The Americans assumed responsibility for all rail traffic west of Liseux on 23 October. Nineteen bridges, six of which were double-track, were opened in November, and work was under way on twenty-two more. No less than of bridging was erected during the month. By the end of the year, 75 railway bridges consisting of 202 spans were partly or completely rebuilt, most of the repairs to the Antwerp marshalling yards were complete, and with the completion of the bridge at 's-Hertogenbosch, trains were running from Antwerp to railheads at Ravenstein and Mill, North Brabant, Mill, just from the front line.

The 21st Army Group had made little use of resupply by air during the Normandy campaign, with the exception of the Polish 1st Armoured Division in August. The RAF operated an aerial freight service but deliveries did not exceed per week in June, and the average weekly delivery was half this. Demand increased dramatically when the 21st Army Group moved beyond the Seine. In the first week of September, of petrol and of supplies were delivered to airfields in the Amiens-Douai area. The following week, with German opposition increasing, priority switched to ammunition, of which was delivered, along with of POL and of supplies.

By this time the airfields around Brussels had been restored to use, and became the destination of air freight, except for some deliveries of POL to Lille. Over the next five weeks, the RAF delivered of air freight to Brussels' Evere Airport alone. Sometimes more than a thousand aircraft arrived in a single day, more than could be cleared with the available road transport, necessitating the establishment of temporary dumps at the airfields. A CRASC transport column HQ that had been specially trained in handling air freight was brought up from the RMA. It took control of two DIDs, and received an average of of cargo each day.

The 21st Army Group had made little use of resupply by air during the Normandy campaign, with the exception of the Polish 1st Armoured Division in August. The RAF operated an aerial freight service but deliveries did not exceed per week in June, and the average weekly delivery was half this. Demand increased dramatically when the 21st Army Group moved beyond the Seine. In the first week of September, of petrol and of supplies were delivered to airfields in the Amiens-Douai area. The following week, with German opposition increasing, priority switched to ammunition, of which was delivered, along with of POL and of supplies.

By this time the airfields around Brussels had been restored to use, and became the destination of air freight, except for some deliveries of POL to Lille. Over the next five weeks, the RAF delivered of air freight to Brussels' Evere Airport alone. Sometimes more than a thousand aircraft arrived in a single day, more than could be cleared with the available road transport, necessitating the establishment of temporary dumps at the airfields. A CRASC transport column HQ that had been specially trained in handling air freight was brought up from the RMA. It took control of two DIDs, and received an average of of cargo each day.

Meanwhile, Boulogne was captured on 22 September, and the port was opened on 12 October. Work switched to the Dumbo system, which involved a much shorter pipeline distance, and was closer to where the 21st Army Group was operating. Lines were run to a beach in the outer harbour of Boulogne instead of Ambleteuse as originally planned because the beach at the latter was heavily mined. A Hais pipeline was laid that commenced pumping on 26 October, and it remained in action until the end of the war.

Boulogne had poor railway facilities, so the pipeline was connected to an overland one to Calais where better railway connections were available. This extension was completed in November. By December, nine 3-inch and two 2-inch Hamel pipelines and four 3-inch and two 2-inch Hais cable pipelines had been laid, a total of 17 pipelines, and Dumbo was providing of petrol per day. The overland pipeline was extended to Antwerp, and then to Eindhoven in the Netherlands, and ultimately to Emmerich am Rhein, Emmerich in Germany. Three storage tanks were erected in Boulogne and four tanks and a tank at Calais.

POL was also moved forward by of POL barges. The floating bridges over the Seine, with the exception of the ones at Vernon and Elbeuf, were removed to allow for barge traffic. For the same reason, low operational bridges over canals in Belgium and the Netherlands were removed and replaced. Rehabilitation of the canal system involved the raising of sunken barges and removal of other obstructions such as blown bridges, and the repair of damaged Lock (water navigation), locks. Severe weather caused the canals to freeze for a time in January and February 1945.

Meanwhile, Boulogne was captured on 22 September, and the port was opened on 12 October. Work switched to the Dumbo system, which involved a much shorter pipeline distance, and was closer to where the 21st Army Group was operating. Lines were run to a beach in the outer harbour of Boulogne instead of Ambleteuse as originally planned because the beach at the latter was heavily mined. A Hais pipeline was laid that commenced pumping on 26 October, and it remained in action until the end of the war.

Boulogne had poor railway facilities, so the pipeline was connected to an overland one to Calais where better railway connections were available. This extension was completed in November. By December, nine 3-inch and two 2-inch Hamel pipelines and four 3-inch and two 2-inch Hais cable pipelines had been laid, a total of 17 pipelines, and Dumbo was providing of petrol per day. The overland pipeline was extended to Antwerp, and then to Eindhoven in the Netherlands, and ultimately to Emmerich am Rhein, Emmerich in Germany. Three storage tanks were erected in Boulogne and four tanks and a tank at Calais.

POL was also moved forward by of POL barges. The floating bridges over the Seine, with the exception of the ones at Vernon and Elbeuf, were removed to allow for barge traffic. For the same reason, low operational bridges over canals in Belgium and the Netherlands were removed and replaced. Rehabilitation of the canal system involved the raising of sunken barges and removal of other obstructions such as blown bridges, and the repair of damaged Lock (water navigation), locks. Severe weather caused the canals to freeze for a time in January and February 1945.

Due to the activity of the Allied air forces, few large German supply dumps were captured until Brussels was reached. Large quantities of food were found there, and for a time these made up a large part of the rations issued to the troops. These included what were for the British soldier unusual items such as pork and foods wikt:impregnate, impregnated with garlic, which served to relieve the monotony of the "compo" field ration augmented with bully beef and biscuits. To bring the German rations up to Field Service (FS) ration scale, additional tea, sugar and milk were added.

The advanced base supply organisation around Antwerp was dispersed in three locations, with four base supply depots at Antwerp, five in Ghent and three in Brussels. Large amounts of refrigeration storage were provided for fresh meat and vegetables, which were now routinely issued. Some ration items now arrived directly from the United States without the double handling inherent in being first landed in the UK. By the end of 1944, the base had of storage capacity, and held 29 million rations. There was sufficient cold storage in the base area to meet the needs of the 21st Army Group, and some storage in the UK was released for use in other theatres or war. Eighty refrigerated van, refrigerated railway wagons were acquired, but in the cold weather no problem was encountered with moving frozen meat in ordinary covered goods wagons. For Christmas, of frozen pork was landed at Ostend in late November.

To economise on bakers, who were in short supply, the 21st Army Group reorganised its eight field bakeries into fourteen mobile field bakeries. This provided a nominal increase in bread-making capacity of per day, while saving 200 bakers. The equipment for the reorganised units was shipped out from the UK.

Due to the activity of the Allied air forces, few large German supply dumps were captured until Brussels was reached. Large quantities of food were found there, and for a time these made up a large part of the rations issued to the troops. These included what were for the British soldier unusual items such as pork and foods wikt:impregnate, impregnated with garlic, which served to relieve the monotony of the "compo" field ration augmented with bully beef and biscuits. To bring the German rations up to Field Service (FS) ration scale, additional tea, sugar and milk were added.

The advanced base supply organisation around Antwerp was dispersed in three locations, with four base supply depots at Antwerp, five in Ghent and three in Brussels. Large amounts of refrigeration storage were provided for fresh meat and vegetables, which were now routinely issued. Some ration items now arrived directly from the United States without the double handling inherent in being first landed in the UK. By the end of 1944, the base had of storage capacity, and held 29 million rations. There was sufficient cold storage in the base area to meet the needs of the 21st Army Group, and some storage in the UK was released for use in other theatres or war. Eighty refrigerated van, refrigerated railway wagons were acquired, but in the cold weather no problem was encountered with moving frozen meat in ordinary covered goods wagons. For Christmas, of frozen pork was landed at Ostend in late November.

To economise on bakers, who were in short supply, the 21st Army Group reorganised its eight field bakeries into fourteen mobile field bakeries. This provided a nominal increase in bread-making capacity of per day, while saving 200 bakers. The equipment for the reorganised units was shipped out from the UK.

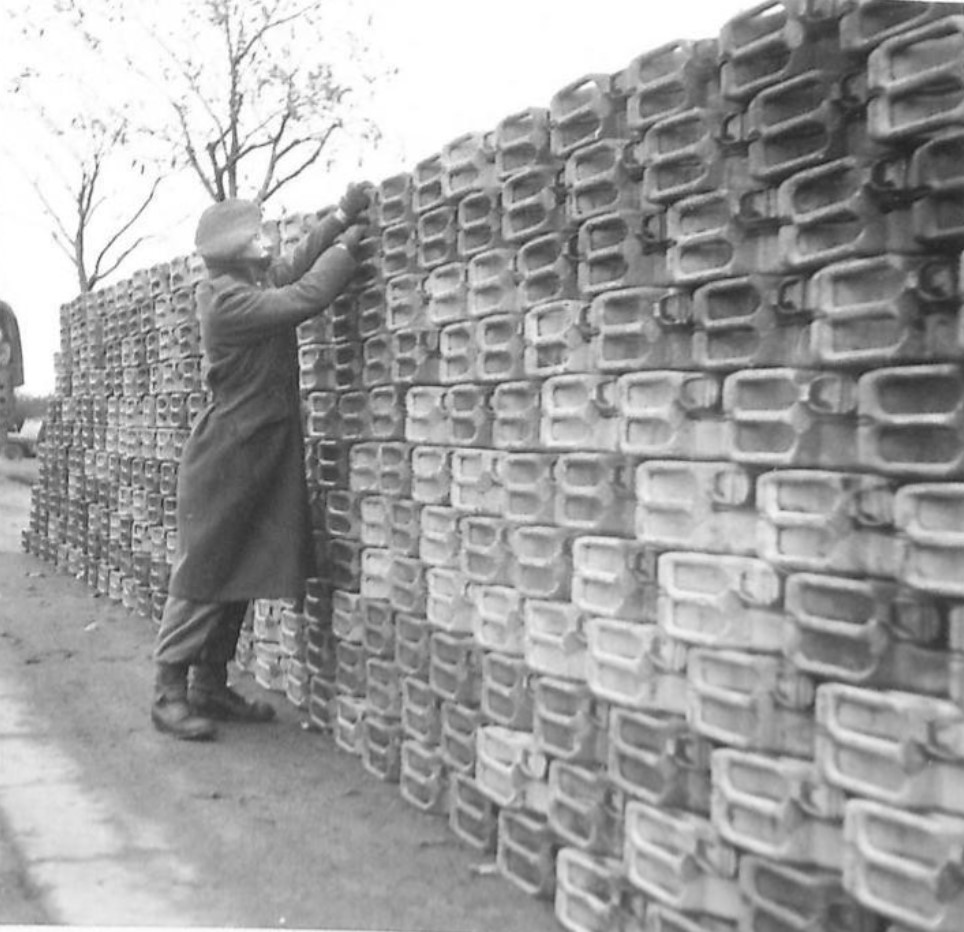

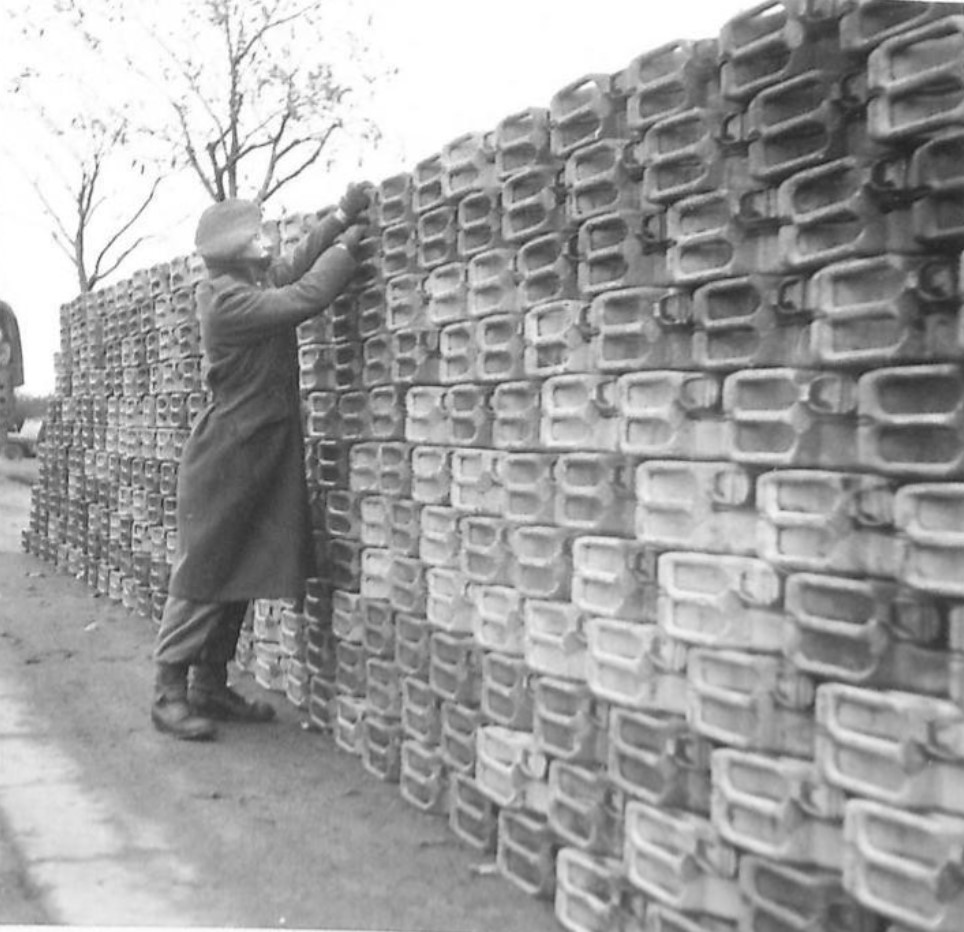

During the rapid advance, jerrican discipline was sometimes lax, and it was often necessary to emphasise the importance of returning the cans. Discarded cans were soon appropriated by the civilian population, resulting in a shortage of jerricans that took months to remedy. Stocks in the UK were depleted, and shipments became limited to the production rate of per day. To alleviate the shortage, POL was issued to line of communications units in bulk. Refilling stations were established along the line of communications to service road convoys. A salvage drive to reclaim jerricans recovered over a million of them. By the end of 1944, the 21st Army Group held stocks of of packaged and bulk POL, representing 58 days' supply. More was held in the army roadheads and FMCs. The filling centre at Rouen was too far back, which meant mobile filling stations were established at the army roadheads. They were withdrawn from army control in November and placed under that of the 21st Army Group.

The War Office held a reserve of of petrol in non-returnable flimsy tins. To alleviate the September packaged fuel shortage, these were shipped to the 21st Army Group. Jerricans were issued in preference though, and were entirely used by the armies and in the forward areas because they were more than satisfactory for shipping and handling and loss through leakage was negligible. With jerrican discipline restored, there were concerns that this might be impaired by the circulation of non-returnable containers. The result was that by December, the 21st Army Group's entire stockpile of of packaged fuel was held in flimsies.

During the German occupation of Belgium the Union Pétrolière Belge (UPB) had controlled the Belgian oil companies, and the 21st Army Group retained its services for the distribution of civilian petroleum products. Such activities were limited to essential services only, and demands were met from military stocks. In return, the oil companies allowed the Allies to use their plants and employees.

During the rapid advance, jerrican discipline was sometimes lax, and it was often necessary to emphasise the importance of returning the cans. Discarded cans were soon appropriated by the civilian population, resulting in a shortage of jerricans that took months to remedy. Stocks in the UK were depleted, and shipments became limited to the production rate of per day. To alleviate the shortage, POL was issued to line of communications units in bulk. Refilling stations were established along the line of communications to service road convoys. A salvage drive to reclaim jerricans recovered over a million of them. By the end of 1944, the 21st Army Group held stocks of of packaged and bulk POL, representing 58 days' supply. More was held in the army roadheads and FMCs. The filling centre at Rouen was too far back, which meant mobile filling stations were established at the army roadheads. They were withdrawn from army control in November and placed under that of the 21st Army Group.

The War Office held a reserve of of petrol in non-returnable flimsy tins. To alleviate the September packaged fuel shortage, these were shipped to the 21st Army Group. Jerricans were issued in preference though, and were entirely used by the armies and in the forward areas because they were more than satisfactory for shipping and handling and loss through leakage was negligible. With jerrican discipline restored, there were concerns that this might be impaired by the circulation of non-returnable containers. The result was that by December, the 21st Army Group's entire stockpile of of packaged fuel was held in flimsies.

During the German occupation of Belgium the Union Pétrolière Belge (UPB) had controlled the Belgian oil companies, and the 21st Army Group retained its services for the distribution of civilian petroleum products. Such activities were limited to essential services only, and demands were met from military stocks. In return, the oil companies allowed the Allies to use their plants and employees.

Until Antwerp was opened, ordnance stores arrived through Boulogne, Dieppe and Ostend. Each handled different types of stores, which simplified sorting and forwarding of ordnance stores, of which passed through these ports in the last three months of 1944. The 15th Advance Ordnance Depot (AOD) began its move to the advanced base in September, and requisitioned offices and storehouses in Antwerp. It was joined there by the 17th AOD. Stocking of the new 15th/17th AOD commenced in November, and it opened for issues to the First Canadian Army on 1 January 1945, and the British Second Army ten days later. Finally, on 22 January, it began servicing the whole line of communications. Until then, demands were met from the RMA. The 15th/17th AOD grew to employ 14,500 people, of whom 11,000 were civilians, and occupied of covered and of open space. Over 126,000 distinct items were stocked, and 191,000 items were demanded in January.

The 2nd Base Ammunition Depot (BAD) opened in Brussels in October 1944, and after a slow start stocks rose to . The 17th BAD opened north of Antwerp towards the end of the year, but its stocking was hampered by V-weapon attacks. Although the tonnage of ammunition was impressive, there were still shortages of it for the field artillery, field and medium artillery. In late October 1943, stocks of ammunition seemed so high that cutbacks in production had been ordered; the labour saved in the UK had been diverted to aircraft production. On 14 October 1944, the Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Lieutenant-General Sir Ronald Weeks, wrote to Montgomery, explaining that expenditure of 25-pounder ammunition was exceeding monthly production by 1.5 million rounds per month, and expenditure of medium artillery ammunition was 40 per cent higher than production.

The War Office was therefore obliged to impose quotas on the armies in the field. This primarily affected the Eighth Army (United Kingdom), Eighth Army in Italy, where major operations had to be postponed until the spring of 1945. An increase in the allotment of ammunition to Italy could only come at the expense of the 21st Army Group, and the War Office was unwilling to do this. The 21st Army Group largely escaped the effects of the shortage. On 7 November, the 21st Army Group restricted usage to 15 rounds per gun per day for field artillery ammunition and 8 rounds per gun per day for medium artillery ammunition, but Montgomery directed that this would apply only during quiet periods, and that stocking of the advanced base would continue until it held 14 days' reserves and 14 days' working margin prescribed by the War Office.

The exigencies of the campaign took their toll on vehicles in wear and tear. A major fault was found with the engines of 1,400 4x4 3-ton Austin K5 lorries, which developed piston trouble. A combination of early frosts and heavy military traffic created numerous potholes in the Dutch and Belgian roads and caused widespread suspension damage to vehicles. Repair work conducted in the advanced base workshops in Brussels and later Antwerp, which were able to take advantage of the static front line and the availability of civilian factories for military workshop spaces to increase their throughput. Civilian garages were also employed to perform repairs.

Until Antwerp was opened, ordnance stores arrived through Boulogne, Dieppe and Ostend. Each handled different types of stores, which simplified sorting and forwarding of ordnance stores, of which passed through these ports in the last three months of 1944. The 15th Advance Ordnance Depot (AOD) began its move to the advanced base in September, and requisitioned offices and storehouses in Antwerp. It was joined there by the 17th AOD. Stocking of the new 15th/17th AOD commenced in November, and it opened for issues to the First Canadian Army on 1 January 1945, and the British Second Army ten days later. Finally, on 22 January, it began servicing the whole line of communications. Until then, demands were met from the RMA. The 15th/17th AOD grew to employ 14,500 people, of whom 11,000 were civilians, and occupied of covered and of open space. Over 126,000 distinct items were stocked, and 191,000 items were demanded in January.

The 2nd Base Ammunition Depot (BAD) opened in Brussels in October 1944, and after a slow start stocks rose to . The 17th BAD opened north of Antwerp towards the end of the year, but its stocking was hampered by V-weapon attacks. Although the tonnage of ammunition was impressive, there were still shortages of it for the field artillery, field and medium artillery. In late October 1943, stocks of ammunition seemed so high that cutbacks in production had been ordered; the labour saved in the UK had been diverted to aircraft production. On 14 October 1944, the Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Lieutenant-General Sir Ronald Weeks, wrote to Montgomery, explaining that expenditure of 25-pounder ammunition was exceeding monthly production by 1.5 million rounds per month, and expenditure of medium artillery ammunition was 40 per cent higher than production.

The War Office was therefore obliged to impose quotas on the armies in the field. This primarily affected the Eighth Army (United Kingdom), Eighth Army in Italy, where major operations had to be postponed until the spring of 1945. An increase in the allotment of ammunition to Italy could only come at the expense of the 21st Army Group, and the War Office was unwilling to do this. The 21st Army Group largely escaped the effects of the shortage. On 7 November, the 21st Army Group restricted usage to 15 rounds per gun per day for field artillery ammunition and 8 rounds per gun per day for medium artillery ammunition, but Montgomery directed that this would apply only during quiet periods, and that stocking of the advanced base would continue until it held 14 days' reserves and 14 days' working margin prescribed by the War Office.

The exigencies of the campaign took their toll on vehicles in wear and tear. A major fault was found with the engines of 1,400 4x4 3-ton Austin K5 lorries, which developed piston trouble. A combination of early frosts and heavy military traffic created numerous potholes in the Dutch and Belgian roads and caused widespread suspension damage to vehicles. Repair work conducted in the advanced base workshops in Brussels and later Antwerp, which were able to take advantage of the static front line and the availability of civilian factories for military workshop spaces to increase their throughput. Civilian garages were also employed to perform repairs.

So many armoured fighting vehicles broke down during the advance in September that the stocks at the RMA and the Armoured Replacement Group (ARG) were almost exhausted. By 27 September, no replacement tanks had arrived for three weeks. Armoured units had only 70 per cent of their unit equipment, and the RMA held only 15 and 5 per cent respectively in stock. Many repairable tanks lay broken down along the road sides awaiting collection by the recovery teams, but these had to move so frequently that it would be some time before repairs could be completed. It was arranged for forty armoured vehicles a day to be shipped to Boulogne in October. The following month LSTs began arriving with tanks at Ostend, and deliveries were split between the two ports, with thirty armoured vehicles arriving at Ostend and twenty at Boulogne each every day. Port clearance presented a problem as there was no railway link at Boulogne, so hard-pressed tank transporters had to be used. By October there were nine tank transporter companies, of which one was allotted to the Canadian First Army, three to the British Second Army, and five were retained under 21st Army Group control. The average tank transporter travelled about per day. In December a shortage of heavy truck tyres caused four of the companies to be taken off the road and used only in emergencies.

At Ostend, there was a rail link, but also a shortage of flatcar, warflat wagons suitable for carrying tanks. The tank shipments absorbed all the available motor transport shipping to forward ports, so other vehicles were shipped to the RMA at the rate of about 250 per day. After Antwerp was opened, shipments through it averaged 30 armoured vehicles and 200 to 300 other vehicles per day. It was found that the two armoured fighting vehicle servicing units were insufficient to cope with the numbers of replacement tanks, so the brigade workshop of the disbanded 27th Armoured Brigade (United Kingdom), 27th Armoured Brigade was employed to service tanks alongside the Second Army Delivery Squadron. In December, the establishment of the armoured troops was changed to two Sherman Firefly tanks armed with the more effective Ordnance QF 17-pounder, 17-pounder and one Sherman tank armed with the old 75mm gun M2–M6, 75 mm gun; previously the ratio had been the reverse.

Two new armoured vehicles were received during the campaign: the American Landing Vehicle Tracked, which was used to equip the 5th Assault Regiment of the 79th Armoured Division (United Kingdom), 79th Armoured Division in September, and was employed in the amphibious operations on the Scheldt; and the British Comet tank, which was issued to the 29th Armoured Brigade (United Kingdom), 29th Armoured Brigade of the 11th Armoured Division in December. A reversion to using British tanks was prompted by a critical shortage of Sherman tanks in the US Army, which caused deliveries to the British Army to be cut back severely in September and October, and then suspended entirely in November and December. The re-equipment of the 29th Armoured Brigade was interrupted by the German Ardennes offensive, and the brigade was hastily re-armed with its Shermans and sent to hold the crossings on the Meuse between Namur and Dinant. The re-equipment process was carried out in January 1945, and the surplus Sherman Fireflies were issued to other units, further reducing the number of Shermans they had armed with the 75 mm gun.

During the German Ardennes offensive, the American depots ceased accepting shipments from Antwerp, as they were threatened by the German advance and might have to relocate at short notice, but the ships continued to arrive. With no depots in the Antwerp area, American stores piled up on the quays. By Christmas, railway traffic had come to a standstill, with trains held up as far back as Paris and Le Havre. An emergency administrative area was created around Lille, where American traffic would not interfere with the British line of communications. The German offensive also raised fears for Brussels' water supply, which would have fallen into German hands had they reached the Meuse between Huy and Dinant. The German Ardennes offensive prompted a request from the US Communications Zone on 26 December for an emergency delivery of 351 Sherman tanks to the US 12th Army Group. These were drawn from the depots and the radios replaced with US patterns. Tank transporters were used to move 217 tanks, with the other 134 despatched by rail. The US forces were also loaned 106 25-pounders, 78 artillery trailers and 30 6-pounder anti-tank guns, along with stocks of ammunition.

So many armoured fighting vehicles broke down during the advance in September that the stocks at the RMA and the Armoured Replacement Group (ARG) were almost exhausted. By 27 September, no replacement tanks had arrived for three weeks. Armoured units had only 70 per cent of their unit equipment, and the RMA held only 15 and 5 per cent respectively in stock. Many repairable tanks lay broken down along the road sides awaiting collection by the recovery teams, but these had to move so frequently that it would be some time before repairs could be completed. It was arranged for forty armoured vehicles a day to be shipped to Boulogne in October. The following month LSTs began arriving with tanks at Ostend, and deliveries were split between the two ports, with thirty armoured vehicles arriving at Ostend and twenty at Boulogne each every day. Port clearance presented a problem as there was no railway link at Boulogne, so hard-pressed tank transporters had to be used. By October there were nine tank transporter companies, of which one was allotted to the Canadian First Army, three to the British Second Army, and five were retained under 21st Army Group control. The average tank transporter travelled about per day. In December a shortage of heavy truck tyres caused four of the companies to be taken off the road and used only in emergencies.

At Ostend, there was a rail link, but also a shortage of flatcar, warflat wagons suitable for carrying tanks. The tank shipments absorbed all the available motor transport shipping to forward ports, so other vehicles were shipped to the RMA at the rate of about 250 per day. After Antwerp was opened, shipments through it averaged 30 armoured vehicles and 200 to 300 other vehicles per day. It was found that the two armoured fighting vehicle servicing units were insufficient to cope with the numbers of replacement tanks, so the brigade workshop of the disbanded 27th Armoured Brigade (United Kingdom), 27th Armoured Brigade was employed to service tanks alongside the Second Army Delivery Squadron. In December, the establishment of the armoured troops was changed to two Sherman Firefly tanks armed with the more effective Ordnance QF 17-pounder, 17-pounder and one Sherman tank armed with the old 75mm gun M2–M6, 75 mm gun; previously the ratio had been the reverse.