British Journalist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of journalism in the United Kingdom includes the gathering and transmitting of

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, Britain was an increasingly stable and prosperous country with an expanding empire, technological progress in industry and agriculture and burgeoning trade and commerce. A new upper middle class consisting of merchants, traders, entrepreneurs and bankers was rapidly emerging - educated, literate and increasingly willing to enter the

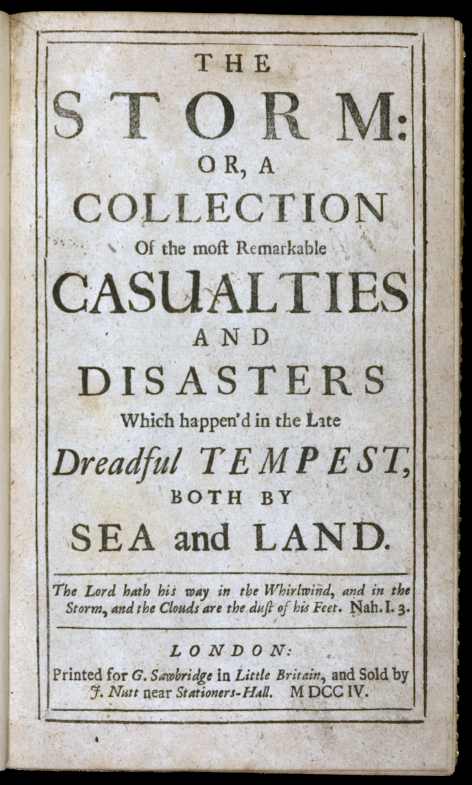

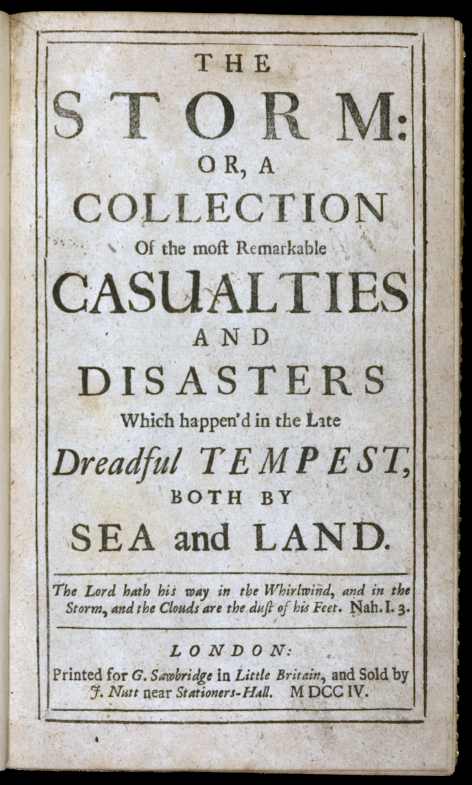

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, Britain was an increasingly stable and prosperous country with an expanding empire, technological progress in industry and agriculture and burgeoning trade and commerce. A new upper middle class consisting of merchants, traders, entrepreneurs and bankers was rapidly emerging - educated, literate and increasingly willing to enter the  Defoe in particular is regarded as a pioneer of modern journalism with his publication '' The Storm'' in 1704,John J. Miller

Defoe in particular is regarded as a pioneer of modern journalism with his publication '' The Storm'' in 1704,John J. Miller

"Writing Up a Storm"

''The Wall Street Journal''. August 13, 2011. which has been called the first substantial work of modern journalism, as well as the first account of a hurricane in Britain. It details the events of a terrible week-long storm that hit London starting Nov 24, 1703, known as the Great Storm of 1703, described by Defoe as "The Greatest, the Longest in Duration, the widest in Extent, of all the Tempests and Storms that History gives any Account of since the Beginning of Time." Defoe used eyewitness accounts by placing newspaper ads asking readers to submit personal accounts, of which about 60 were selected and edited by Defoe for the book. This was an innovative method for the time before journalism that relied on first-hand reports was commonplace.

accessed 3 May 2011

/ref> Stead became well known for his reportage on child welfare, social legislation and reformation of England's criminal codes. Stead became assistant editor of the liberal ''

''The Times'' became famous for its influential leaders (editorials). For example, Robert Lowe wrote them between 1851 and 1868 on a wide range of economic topics such as

''The Times'' became famous for its influential leaders (editorials). For example, Robert Lowe wrote them between 1851 and 1868 on a wide range of economic topics such as

online

/ref> Bingham, however, states that in his view, there are serious problems: :The three main areas where the press is justifiably open to attack are: in failing to represent and respect the diversity of modern Britain; in privileging speed and short-term impact over accuracy and reliability; and in its reluctance to accept and reflect on the social responsibilities involved in popular journalism. In 2005, the UK-based online newspaper

online old classic

* Boyce, D. G. "Crusaders without chains: power and the press barons 1896-1951" in J. Curran, A. Smith and P. Wingate, eds., ''Impacts and Influences: Essays on Media Power in the Twentieth Century'' (Methuen, 1987). * Briggs, Asa. ''The BBC—the First Fifty Years'' (Oxford University Press, 1984). * Briggs, Asa. ''The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom'' (Oxford UP, 1961). *

* Bingham, Adrian. ''Gender, Modernity, and the Popular Press in Inter-War Britain'' (Oxford UP, 2004). * Brooker, Peter, and Andrew Thacker, eds. ''The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume I: Britain and Ireland 1880-1955'' (2009) * Viscount Camrose. ''Brutish Newspapers And Their Controllers'' (1947

online

ownership of all major papers in 1947 * Clarke, Bob. ''From Grub Street to Fleet Street: An Illustrated History of English Newspapers to 1899'' (Ashgate, 2004) * Conboy, Martin. ''Journalism in Britain: a historical introduction'' (2011). * Cox, Howard and Simon Mowatt. ''Revolutions from Grub Street: A History of Magazine Publishing in Britain'' (2015

excerpt

* Crisell, Andrew ''An Introductory History of British Broadcasting.'' (2nd ed. 2002). * Griffiths, Dennis. ''The Encyclopedia of the British press, 1422-1992'' (Macmillan, 1992). * Hampton, Mark. "Newspapers in Victorian Britain." ''History Compass'' 2#1 (2004). Historiography * Harrison, Stanley (1974). ''Poor Men's Guardians: a Survey of the Democratic and Working-class Press''. London: Lawrence & Wishart. {{ISBN, 0-85315-308-6 * Herd, Harold. ''The March of Journalism: The Story of the British Press from 1622 to the Present Day'' (1952). * Jones, Aled. ''Powers of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth-Century England'' (1996). * Jones, Aled. ''Press, Politics and Society: a history of journalism in Wales'' (U of Wales Press, 1993). *

online

* Dooley, Brendan, and Sabrina Baron, eds. ''The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe'' (Routledge, 2001) * Wolff, Michael. ''The Man Who Owns the News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch'' (2008) 446 page

excerpt and text search

A media baron in Australia, UK and the US

Biographical dictionary of 24,000+ British and Irish journalists who died between 1800 and 1960

UK History of the United Kingdom by topic

news

News is information about current events. This may be provided through many different Media (communication), media: word of mouth, printing, Mail, postal systems, broadcasting, Telecommunications, electronic communication, or through the tes ...

, spans the growth of technology and trade, marked by the advent of specialised techniques for gathering and disseminating information on a regular basis. In the analysis of historians, it involves the steady increase of

the scope of news available to us and the speed with which it is transmitted.

Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. London has always been the main center of British journalism, followed at a distance by Edinburgh, Belfast, Dublin, and regional cities.

Origins

Across western Europe after 1500 news circulated through newsletters through well-established channels. Antwerp was the hub of two networks, one linking France, Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands; the other linking Italy, Spain and Portugal. Favorite topics included wars, military affairs, diplomacy, and court business and gossip. After 1600 the national governments in France and England began printing official newsletters. In 1622 the first English-language weekly magazine, "A current of General News" was published and distributed inEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in an 8- to 24-page quarto format.

16th Century

By the 1500s, printing was firmly in the royal jurisdiction, and printing was restricted only to English subjects. The Crown imposed strict controls on the distribution of religious or political printed materials. In 1538,Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

decreed that all printed matter had to be approved by the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

before publication. By 1581, the publication of seditious material had become a capital offence.

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

used the trade itself to control it. She granted a Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

to the Company of Stationers

The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (until 1937 the Worshipful Company of Stationers), usually known as the Stationers' Company, is one of the livery companies of the City of London. The Stationers' Company was formed in ...

in 1557. The Company became a partner with the state under Queen Elizabeth. They advantaged greatly from this partnership as this restricted the number of presses, allowing them to keep their profitable business without much competition. This also worked in the favour of the Crown as the Company were less likely to publish material that would disturb their relationship because their privileges were directly derived from them.

Restrictions only became tighter in the printing industry as time went on. Edward VI prohibited 'spoken news or rumour' in his proclamations of 1547 to 1549. Royal permission had to be obtained before any news could be published, and all printed news was regarded as the royal prerogative.

The only form of printed news that was permitted to be circulated was the 'relation'. This was a narrative of a single event, domestic or foreign. These were printed and circulated for hundreds of years, often sold at the north door of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

. There were two categories of news being circulated here: items of 'Wonderful and Strange Newes' and government propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

. The first category of news was often given eye catching titles to grab the reader with its sensational content.

17th Century

The 17th century saw the rise of political pamphleteering fuelled by the politically contentious times of bloodycivil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. Each party sought to mobilise its supporters by the widespread distribution of pamphlets, as in the coffeehouses where one copy would be passed around and read aloud. Holland already had a regular weekly news service, knows as corantos. Holland began supplying a thousand or so copies of corantos to the English market in 1620. The first coranto printed in England was likely printed by Thomas Archer of Pope's Head Alley in early 1621. He was sent to prison later that year for printing a coranto without a license. They were expensive and had low sales because people were more interested in issues in England rather than in Europe.

The Court of High Commission and the Star Chamber

The Star Chamber (Latin: ''Camera stellata'') was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (c. 1641), and was composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the judic ...

were abolished in 1641, and copyright laws were not enforced. The press was now free. Many people began to print their own newsbooks, free of any worry of prosecution, but only a few publications continued past the first few issues. Civil War era newsbooks contained information that affected everybody. They were available for a penny or twopence a copy. Some titles sold as many as 1,500 copies.

A milestone was reached in 1694; the final lapse of the Licensing Order of 1643 that had been put in place by the Stuart

Stuart may refer to:

Names

* Stuart (name), a given name and surname (and list of people with the name) Automobile

*Stuart (automobile)

Places

Australia Generally

*Stuart Highway, connecting South Australia and the Northern Territory

Northe ...

kings put an end to heavy-handed censorship that had previously tried to suppress the flow of free speech and ideas across society, and allowed writers to criticise the government freely. From 1694 to the Stamp Act of 1712 the only censure laws forbade treason, seditious libel and the reporting of Parliamentary proceedings.

The 1640s and 1650s were a fast-paced time in the history of British journalism. Because of the abolition of copyright laws, over 300 titles quickly came into existence. Many did not last, with only thirty three lasting a full year. This was also a time filled with war and fragmentation of opinion. The Royalists' main title was ''Mercurius Aulicus, Mercurius Melancholicus'' ('The King shall enjoy his owne againe and the Royall throne shall be arraied with the glorious presence of that mortall Deity'), ''Mercurius Electicus'' ('Communicating the Unparallell'd Proceedings of the Revels at West-minster, The Headquarters and other Places, Discovering their Designs, Reproving their Crimes, and Advising the Kingdome') and ''Mercurius Rusticus'', among others. Most newsbooks in London supported the Parliament, and titles included ''Spie,'' The ''Parliament Scout'' and The ''Kingdomes Weekly Scout''. These publication compelled the reader to take sides, depending on whose bias and propaganda they were reading.

There was also a series of semi-pornographic newsbooks produced by John Crouch: ''The Man in the Moon, Mercurius Democritus'' and ''Mercurius Fumigosus.'' These publications contained a mixture of news and dirty jokes disguised as news.

The huge and absolute freedom of the press came to an end with the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

. King Charles introduced the Printing Act of 1662, which restricted printing to the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

and to the master printers of the Stationer's Company in London. It also required that only twenty were allowed to work in the master printers. This act provided the highly regulated and restricted environment that had previously been abolished.

The Oxford Gazette was printed in 1665 by Muddiman in the middle of the turmoil of the Great Plague of London and was, strictly speaking, the first periodical to meet all the qualifications of a true newspaper. It was printed twice a week by royal authority and was soon renamed the London Gazette

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. Magazines were also moral tracts inveighing against moral decadence, notably the ''Mercurius Britannicus''. The ''Gazette'' is generally considered by most historians to be the first English newspaper.

Prior to the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

journalism had been a risky line of work. One such victim was the reckless Benjamin Harris, who was convicted for defaming the King's authority. Unable to pay the large fine that was imposed on him he was put in prison. He eventually made his way to America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

where he founded one of the first newspapers there. After the Revolution, the new monarch William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

, who had been installed by Parliament, was wary of public opinion and did not try to interfere with the burgeoning press. The growth in journalism and the increasing freedom the press enjoyed was a symptom of a more general phenomenon - the development of the party system of government. As the concept of a parliamentary opposition

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''th ...

became an acceptable (rather than treasonable) norm, newspapers and editors began to adopt critical and partisan stances and they soon became an important force in the political and social affairs of the country.

18th Century

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, Britain was an increasingly stable and prosperous country with an expanding empire, technological progress in industry and agriculture and burgeoning trade and commerce. A new upper middle class consisting of merchants, traders, entrepreneurs and bankers was rapidly emerging - educated, literate and increasingly willing to enter the

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, Britain was an increasingly stable and prosperous country with an expanding empire, technological progress in industry and agriculture and burgeoning trade and commerce. A new upper middle class consisting of merchants, traders, entrepreneurs and bankers was rapidly emerging - educated, literate and increasingly willing to enter the political discussion

Political criticism (also referred to as political commentary or political discussion) is criticism that is specific of or relevant to politics, including policies, politicians, political parties, and types of government.

See also

* Bad Subje ...

and participate in the governance of the country. The result was a boom in journalism, in newspapers and magazines. Writers who had been dependent on a rich patron in the past were now able to become self-employed by hiring out their services to the newspapers. The values expressed in this new press were overwhelmingly consistent with the bourgeois middle class - an emphasis on the importance of property rights, religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

and intellectual freedom in contrast to the restrictions prevalent in France and other nations.

London's ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term ''magazine'' (from the French ''magazine'' ...

'', first published in 1731, was the first general-interest magazine. Edward Cave

Edward Cave (27 February 1691 – 10 January 1754) was an English printer, editor and publisher. He coined the term "magazine" for a periodical, founding ''The Gentleman's Magazine'' in 1731, and was the first publisher to successfully fashio ...

, who edited it under the pen name "Sylvanus Urban", was the first to use the term "magazine", on the analogy of a military storehouse. The oldest consumer magazine still in print is '' The Scots Magazine'', which was first published in 1739, though multiple changes in ownership and gaps in publication totalling over 90 years weaken its claim. ''Lloyd's List

''Lloyd's List'' is one of the world's oldest continuously running journals, having provided weekly shipping news in London as early as 1734. It was published daily until 2013 (when the final print issue, number 60,850, was published), and is ...

'' was founded in Edward Lloyd's England coffee shop in 1734; it is still published as a daily business newspaper.

Journalism in the first half of the 18th century produced many great writers such as Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

, Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison (1 May 1672 – 17 June 1719) was an English essayist, poet, playwright and politician. He was the eldest son of The Reverend Lancelot Addison. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend Richard S ...

, Richard Steele

Sir Richard Steele (bap. 12 March 1672 – 1 September 1729) was an Anglo-Irish writer, playwright, and politician, remembered as co-founder, with his friend Joseph Addison, of the magazine ''The Spectator''.

Early life

Steele was born in Du ...

, Henry Fielding, and Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

. Men such as these edited newspapers, or wrote essays for the popular press on topical issues. Their material was entertaining and informative and was met with an insatiable demand from ordinary citizens of the middle class, who were beginning to participate in the flow of ideas and news.

The newspaper was becoming so popular that publishers began to print daily issues. The first daily newspaper in the world was the '' Daily Courant'', established by Samuel Buckley in 1702 on the streets of London. The newspaper strictly restricted itself to the publication of news and facts without opinion pieces, and was able to avoid political interference through raising revenue by selling advertising space in its columns.

Defoe in particular is regarded as a pioneer of modern journalism with his publication '' The Storm'' in 1704,John J. Miller

Defoe in particular is regarded as a pioneer of modern journalism with his publication '' The Storm'' in 1704,John J. Miller"Writing Up a Storm"

''The Wall Street Journal''. August 13, 2011. which has been called the first substantial work of modern journalism, as well as the first account of a hurricane in Britain. It details the events of a terrible week-long storm that hit London starting Nov 24, 1703, known as the Great Storm of 1703, described by Defoe as "The Greatest, the Longest in Duration, the widest in Extent, of all the Tempests and Storms that History gives any Account of since the Beginning of Time." Defoe used eyewitness accounts by placing newspaper ads asking readers to submit personal accounts, of which about 60 were selected and edited by Defoe for the book. This was an innovative method for the time before journalism that relied on first-hand reports was commonplace.

Richard Steele

Sir Richard Steele (bap. 12 March 1672 – 1 September 1729) was an Anglo-Irish writer, playwright, and politician, remembered as co-founder, with his friend Joseph Addison, of the magazine ''The Spectator''.

Early life

Steele was born in Du ...

, influenced by Defoe, set up '' The Tatler'' in 1709 as a publication of the news and gossip heard in London coffeehouses

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-caf ...

, hence the title. It presented Whiggish

Whig history (or Whig historiography) is an approach to historiography that presents history as a journey from an oppressive and benighted past to a "glorious present". The present described is generally one with modern forms of liberal democracy ...

views and created guidelines for middle-class manners, while instructing "these Gentlemen, for the most part being Persons of strong Zeal, and weak Intellects...''what to think.''"

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

wrote his greatest satires for '' The Examiner'', often in allegorical form, lampooning the controversies between the Tories and Whigs. The so-called "Cato Letters," written by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon under the pseudonym, "Cato", were published in the London Journal

James Boswell's ''London Journal'' is a published version of the daily journal he kept between the years 1762 and 1763 while in London. Along with many more of his private papers, it was found in the 1920s at Malahide Castle in Ireland, and was ...

in the 1720s and discussed the theories of the Commonwealth men

The Commonwealth men, Commonwealth's men, or Commonwealth Party were highly outspoken British Protestantism, Protestant religious, political, and economic reformers during the early 18th century. They were active in the movement called the Country ...

such as ideas about liberty, representative government, and freedom of expression. These letters had a great impact in colonial America and the nascent republican movement all the way up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Taxes on the press

The increasing popularity and influence of newspapers was unappealing to the government of the day. A duty was imposed in 1712 that lasted a century and a half at different rates covering newspapers, pamphlets, advertisements and almanacs.H. Dagnall, "The taxes on knowledge: excise duty on paper." ''Library'' 6.4 (1998): 347-363. At first the stamp tax was a halfpenny on newspapers of half a sheet or less and a penny on newspapers that ranged from half a sheet to a single sheet in size. Jonathan Swift expressed in his ''Journal to Stella'' on August 7, 1712, doubt in the ability of ''The Spectator'' to hold out against the tax. This doubt was proved justified in December 1712 by its discontinuance. However, some of the existing journals continued production and their numbers soon increased. Part of this increase was attributed to corruption and political connections of its owners. Later, toward the middle of the same century, the provisions and the penalties of the Stamp Act were made more stringent, yet the number of newspapers continued to rise. In 1753 the total number of copies of newspapers sold yearly in Britain amounted to 7,411,757. In 1760 it had risen to 9,464,790 and in 1767 to 11,300,980. In 1776 the number of newspapers published in London alone had increased to 53. An important figure in the fight for increased freedom of the press wasJohn Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fo ...

. When the Scot John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, came to head the government in 1762, Wilkes started a radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

weekly publication, '' The North Briton'', to attack him, using an anti-Scottish tone. He was charged with seditious libel over attacks on George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

's speech endorsing the Paris Peace Treaty of 1763 at the opening of Parliament on 23 April 1763. Forty-nine people, including Wilkes, were arrested under the warrants. Wilkes, however, gained considerable popular support as he asserted the unconstitutionality of general warrants. At his court hearing the Lord Chief Justice ruled that as an MP, Wilkes was protected by privilege from arrest on a charge of libel. He was soon restored to his seat and he sued his arresters for trespass.

As a result of this episode, his popular support surged, with people chanting, "Wilkes, Liberty and Number 45", referring to the newspaper. However, he was soon found guilty of libel again and he was sentenced to 22 months imprisonment and a fine of £1,000. Although he was subsequently elected 3 times in a row for Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

, the decision was overturned by Parliament. When he was finally released from prison in 1770 he campaigned for increased freedom of the press; specifically he defended the right of publishers to print reports of Parliamentary debates. Due to large and growing support, the government was forced to back down and abandoned its attempts at censorship.

19th Century

A series of developments 1850-1890 transformed the small closed newspaper world into big business. From 1860 until 1910 was the 'golden age' of newspaper publication, with technical advances in printing and communication combined with a professionalisation of journalism and the prominence of new owners. Political leaders tried to manipulate the press to a greater or lesser extent. Journalists paid more attention to leaders than to staffers, leading an advisor to tell Prime Minister Wellington in 1829 he should make his cabinet ministers responsible for secretly influencing or 'instructing' the friendly papers instead of a using a mere parliamentary secretary. Political journalists displayed an exalted view of themselves, as Lord Stanley noted in 1851: :They have the irritable vanity of authors, and add to it a sensitiveness on the score of social position which so far as I know is peculiar to them. Having in reality a vast secret influence, rating this above its true worth, and seeing that it gives them no recognised status in society, they stand up for the dignity of their occupation with a degree of jealousy that I never saw among any other profession. Meanwhile, newspapers were also facing the pressures of advertisers whose power intensified following the removal of taxes on the press and implied control over newspaper content.Taxes abolished

A pioneer of popular journalism for the masses had been the Chartist '' Northern Star'', first published on 26 May 1838. The same time saw the first cheap newspaper in the ''Daily Telegraph and Courier'' (1855), later to be known simply as the ''Daily Telegraph

Daily or The Daily may refer to:

Journalism

* Daily newspaper, newspaper issued on five to seven day of most weeks

* ''The Daily'' (podcast), a podcast by ''The New York Times''

* ''The Daily'' (News Corporation), a defunct US-based iPad new ...

''. ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

'', founded in 1842, was the world's first illustrated weekly newspaper.

Reformers pressured the government and it repeatedly cut the high taxes on knowledge, including the excise duty on paper and the 5-penny stamp tax on each copy printed of a newspapers, pamphlet, advertisements and almanacs. In 1800 there were 52 London papers and over 100 other titles. The war with France was under way and the government wanted to suppress negative rumours and damaging information, so it tightened censorship and raised taxes so that few people could afford to buy a copy. In 1802 and 1815 the tax on newspapers was increased to three pence and then four pence. This was more than the average daily pay of the working man. However, coffeehouses typically purchased one or two copies that were handed around. In the 1830s hundreds of illegal untaxed newspapers circulated. The political tone of most of them was fiercely revolutionary. Their publishers were prosecuted but this failed to get rid of them. It was chiefly Milner Gibson and Richard Cobden who advocated the case in parliament to first reduce in 1836 and in 1855 totally repeal of the tax on newspapers. After the reduction of the stamp tax in 1836 from four pence to one penny, the circulation of English newspapers rose from 39,000,000 to 122,000,000 by 1854; a trend further exacerbated by technological improvements in transportation and communication combined with growing literacy. By 1861 all taxes had ended, making cheap publications reaching a large market feasible. For the first time it was financially attractive to plan for much larger circulations and therefore to invest in the new technologies which had been impractical before. Freedom from most taxes in the 1830s encouraged the launching of such titles. The ''Daily Telegraph, which'' appeared on 29 June 1855 and soon sold for 1 d. Sixteen new major provincials papers were founded, and older titles enlarge their scope. ''The Manchester Guardian,'' started out as a weekly in 1821, became a daily of 1855, as did the ''Liverpool Post'' and the ''Scotsman.'' The newspapers were stodgy affairs bringing great prestige and political influence to the closed network of families that owned them. ''The Times'', edited by John Thadeus Delane stood preeminent.

Innovations

The new technology, especially therotary press

A rotary printing press is a printing press in which the images to be printed are curved around a cylinder. Printing can be done on various substrates, including paper, cardboard, and plastic. Substrates can be sheet feed or unwound on a continuo ...

, allowed printing of tens of thousands of copies a day at low cost. The price of paper fell and huge rolls 3 miles in length of paper made from cheap wood pulp instead of expensive rags were fitted onto the Hoe rotary press. The linotype machine appeared in the 1870s and sped up typesetting and lowered its cost. The electoral franchise was expanded from one or two percent of the men to a majority, and newspapers became the primary means of political education. In the 1870s, the London newspapers were stodgy affairs pitched to public school graduates and other elite men.

New Journalism

Sensationalism, emphasizing dramatic stories, large headlines, and an emotional writing style was introduced byW. T. Stead

William Thomas Stead (5 July 184915 April 1912) was a British newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era. Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst ed ...

, the editor of ''The Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'' (1883-1889). The New Journalism reached out not to the elite but to a popular audience. Especially influential was William Thomas Stead, a controversial journalist and editor who pioneered the art of investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years rese ...

. Stead's 'new journalism' paved the way for the modern tabloid

Tabloid may refer to:

* Tabloid journalism, a type of journalism

* Tabloid (newspaper format), a newspaper with compact page size

** Chinese tabloid

* Tabloid (paper size), a North American paper size

* Sopwith Tabloid, a biplane aircraft

* ''Ta ...

. He was influential in demonstrating how the press could be used to influence public opinion and government policy, and advocated "government by journalism".Joseph O. Baylen, 'Stead, William Thomas (1849–1912)', ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', 2004; online edn, Sept 201accessed 3 May 2011

/ref> Stead became well known for his reportage on child welfare, social legislation and reformation of England's criminal codes. Stead became assistant editor of the liberal ''

The Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'' in 1880 where he set about revolutionising a traditionally conservative newspaper "written by gentlemen for gentlemen." Over the next seven years Stead would develop what Matthew Arnold dubbed 'The New Journalism'. His innovations as editor of the ''Gazette'' included incorporating maps and diagrams into a newspaper for the first time, breaking up longer articles with eye-catching subheadings and blending his own opinions with those of the people he interviewed. He made a feature of the ''Pall Mall'' extras, and his enterprise and originality exercised a potent influence on contemporary journalism and politics. Stead's first sensational campaign was based on a Nonconformist pamphlet, "The Bitter Cry of Outcast London." His lurid stories of squalid life spurred the government into clearing the slums and building low-cost housing in their place. He also introduced the interview, creating a new dimension in British journalism when he interviewed General Gordon in 1884. His use of sensationalist headlines is exemplified with the death of Gordon in Khartoum in 1885, when he ran the first 24-point headline in newspaper history, "TOO LATE!", bemoaning the relief force's failure to rescue a national hero.The Sunday Times (London) May 13, 2012 Sunday Edition 1; National Edition Fleet Street's crusading villain; The Victorian editor whose love of sensationalism set the tone for the tabloids for a century Scandalmonger 40-42 He is also credited as originating the modern journalistic technique of creating a news event rather than just reporting it, with his most famous 'investigation', the Eliza Armstrong case.

Matthew Arnold, the leading critic of the day, declared in 1887 that the New Journalism, "is full of ability, novelty, variety, sensation, sympathy, generous instincts." However, he added, its "one great fault is that it is feather-brained."

The revolutionary: Alfred Harmsworth

Bringing all the factors together, a decisive transformation away from a high cost, low circulation elite newspaper world in the 1880s was the brainchild of Alfred Harmsworth (1865-1922). He closely studied the emergence of yellow journalism in New York, as led byWilliam Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

and Joseph Pulitzer. He realized that the money was to be made from not the cover price, which should be lowered to a halfpenny, but from advertisements. The advertisers wanted more and more readers--millions if possible--because they wanted to reach not only the entire middle class, but many well-paid members of the working-class. Harmsworth combined all the new technical innovations, with sensationalism, and a fixed goal of maximizing profits. Working with journalist Kennedy Jones, Harmsworth set up the ''Evening News'' in 1894, and in 1896 launched the morning paper, the ''Daily Mail''. The new formula was to maximize the readership using sensationalism, features, illustrations, and advertisements pitched to women for department stores offering the latest fashions. Harmsworth scored an immediate triumph. The first year daily sales averaged 200,000, and in three years it sold a half-million copies a day. The prestige press did not try to catch up, for they measured success not by sales or profits but on prestige and power they wielded by dominating the news needs of the upper class British elite.

''The Times''

''The Daily Universal Register'' published from 1785 and become known as ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' from 1788. In 1817 Thomas Barnes became general editor; he was a political radical, a sharp critic of parliamentary hypocrisy and a champion of freedom of the press. Under Barnes and his successor in 1841, John Thadeus Delane, the influence of ''The Times'' rose to great heights, especially in politics and in the financial district (the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

). It spoke for reform.

Due to Barnes's influential support for Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

in Ireland, his colleague Lord Lyndhurst

John Singleton Copley, 1st Baron Lyndhurst, (21 May 1772 – 12 October 1863) was a British lawyer and politician. He was three times Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain.

Background and education

Lyndhurst was born in Boston, Massachusetts, t ...

described him as "the most powerful man in the country". Journalists of note included Peter Fraser and Edward Sterling, who gained for ''The Times'' the pompous/satirical nickname 'The Thunderer' (from "We thundered out the other day an article on social and political reform.") The paper became the first in the world to reach mass circulation due to its early adoption of the steam-driven rotary printing press. It was also the first properly national newspaper, using the new steam trains to deliver copies to the rapidly growing concentrations of urban populations across the UK. This helped ensure the profitability of the paper and its growing influence.

''The Times'' originated the practice for newspapers to send war correspondents to cover particular conflicts. W. H. Russell

Sir William Howard Russell, (28 March 182011 February 1907) was an Irish reporter with ''The Times'', and is considered to have been one of the first modern war correspondents. He spent 22 months covering the Crimean War, including the Sieg ...

, the paper's correspondent with the army in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

of 1853–1856, wrote immensely influential dispatches; for the first time the public could read about the reality of warfare. In particular, on September 20, 1854, Russell wrote a missive about one battle that highlighted the surgeons' "humane barbarity" and the lack of ambulance care for wounded troops. Shocked and outraged, the public reacted in a backlash that led to major reforms.

''The Times'' became famous for its influential leaders (editorials). For example, Robert Lowe wrote them between 1851 and 1868 on a wide range of economic topics such as

''The Times'' became famous for its influential leaders (editorials). For example, Robert Lowe wrote them between 1851 and 1868 on a wide range of economic topics such as free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

(which he favoured).

In 1959, historian of journalism Allan Nevins analysed the importance of ''The Times'' in shaping the views of events of London's elite:

:For much more than a century ''The Times'' has been an integral and important part of the political structure of Great Britain. Its news and its editorial comment have in general been carefully coordinated, and have at most times been handled with an earnest sense of responsibility. While the paper has admitted some trivia to its columns, its whole emphasis has been on important public affairs treated with an eye to the best interests of Britain. To guide this treatment, the editors have for long periods been in close touch with 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London, also known colloquially in the United Kingdom as Number 10, is the official residence and executive office of the first lord of the treasury, usually, by convention, the prime minister of the United Kingdom. Along wi ...

.

Manchester Guardian and Daily Telegraph

The ''Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' was founded in Manchester in 1821 by a group of non-conformist businessmen. Its most famous editor, Charles Prestwich Scott

Charles Prestwich Scott (26 October 1846 – 1 January 1932), usually cited as C. P. Scott, was a British journalist, publisher and politician. Born in Bath, Somerset, he was the editor of the ''Manchester Guardian'' (now ''the Guardian'') ...

, made the ''Guardian'' into a world-famous newspaper in the 1890s. ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' was first published on June 29, 1855 and was owned by Arthur Sleigh, who transferred it to Joseph Levy the following year. Levy produced it as the first penny newspaper in London. His son, Edward Lawson soon became editor, a post he held until 1885. ''The Daily Telegraph'' became the organ of the middle class and could claim the largest circulation in the world in 1890. It held a consistent Liberal Party allegiance until opposing William Gladstone's foreign policy in 1878 when it turned Unionist.

20th Century

The 20th-century "popular press" had its origins in the street ballads, penny novels, and illustrated weeklies which preceded by many years the passage of theElementary Education Act 1870

The Elementary Education Act 1870, commonly known as Forster's Education Act, set the framework for schooling of all children between the ages of 5 and 12 in England and Wales. It established local education authorities with defined powers, autho ...

. By 1900 popular newspapers aimed at the largest possible audience had proven a success. P. P. Catterall

Pippa Poppy Catterall (born Peter Paul Catterall in 1961) is a British academic historian who, since 2016, has been Professor of History and Policy at the University of Westminster. Her research has focused on twentieth-century history and politi ...

and Colin Seymour-Ure

Colin Knowlton Seymour-Ure (11 November 1938 – 18 November 2017) was professor of government at the University of Kent at Canterbury. He was a specialist in the history of political cartoons and caricature and was one of the founders of the Briti ...

conclude that:

:More than anyone lfred Harmsworth... shaped the modern press. Developments he introduced or harnessed remain central: broad contents, exploitation of advertising revenue to subsidize prices, aggressive marketing, subordinate regional markets, independence from party control. The ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' held the world record for daily circulation until Harmsworth's death. He used his newspapers newly found influence, in 1899, to successfully make a charitable appeal for the dependents of soldiers fighting in the South African War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

by inviting Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

and Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

to write ''The Absent-Minded Beggar

"The Absent-Minded Beggar" is an 1899 poem by Rudyard Kipling, set to music by Sir Arthur Sullivan and often accompanied by an illustration of a wounded but defiant British soldier, "A Gentleman in Kharki", by Richard Caton Woodville. The song w ...

''. Prime Minister Robert Cecil Robert Cecil may refer to:

* Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563–1612), English administrator and politician, MP for Westminster, and for Hertfordshire

* Robert Cecil (1670–1716), Member of Parliament for Castle Rising, and for Wootton Ba ...

, Lord Salisbury, quipped it was "written by office boys for office boys".

Socialist and labour newspapers also proliferated and in 1912 the ''Daily Herald

Daily or The Daily may refer to:

Journalism

* Daily newspaper, newspaper issued on five to seven day of most weeks

* ''The Daily'' (podcast), a podcast by ''The New York Times''

* ''The Daily'' (News Corporation), a defunct US-based iPad new ...

'' was launched as the first daily newspaper of the trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

and labour movement.

Newspapers reached their peak of importance during the First World War, in part because wartime issues were so urgent and newsworthy, while members of Parliament were constrained by the all-party coalition government from attacking the government. By 1914 Northcliffe controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation. He eagerly tried to turn it into political power, especially in attacking the government in the Shell Crisis of 1915

The Shell Crisis of 1915 was a shortage of artillery shells on the front lines in the First World War that led to a political crisis in the United Kingdom. Previous military experience led to an over-reliance on shrapnel to attack infantry in th ...

. Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

said he was, "the greatest figure who ever strode down Fleet Street." A.J.P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

, however, says, "Northcliffe could destroy when he used the news properly. He could not step into the vacant place. He aspired to power instead of influence, and as a result forfeited both."

Other powerful editors included C. P. Scott of the ''Manchester Guardian'', James Louis Garvin

James Louis Garvin CH (12 April 1868 – 23 January 1947) was a British journalist, editor, and author. In 1908, Garvin agreed to take over the editorship of the Sunday newspaper ''The Observer'', revolutionising Sunday journalism and restori ...

of ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'' and Henry William Massingham

Henry William Massingham (25 May 1860 – 27 August 1924) was an English journalist, editor of ''The Nation and Athenaeum, The Nation'' from 1907 to 1923. In his time it was considered the leading British Radical weekly.

Life

He j ...

of the highly influential weekly magazine of opinion, ''The Nation''.

21st century

Journalism expert Adrian Bingham argues that newspaper journalists are held in low repute. He cites one poll that found the trustworthiness of journalists on ''The Sun,'' ''Mirror'' and ''Daily Star'' fell far below government ministers and estate agents. Only 7% said they could be relied upon to tell the truth. Television journalists, scored much higher at 49%. Bingham list some popular complaints, but dismisses them as an inevitable long-term characteristic of the media: :The British popular press is repeatedly accused of being untrustworthy and irresponsible; of poisoning political debate and undermining the democratic process; of inciting hostility against immigrants and ethnic minorities; and of coarsening public life by promoting a sleazy and intrusive celebrity culture.Adrian Bingham, "Monitoring the popular press: an historical perspective," ''History & Policy'' (2005online

/ref> Bingham, however, states that in his view, there are serious problems: :The three main areas where the press is justifiably open to attack are: in failing to represent and respect the diversity of modern Britain; in privileging speed and short-term impact over accuracy and reliability; and in its reluctance to accept and reflect on the social responsibilities involved in popular journalism. In 2005, the UK-based online newspaper

PinkNews

''PinkNews'' is a UK-based online newspaper marketed to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community (LGBT) in the UK and worldwide. It was founded by Benjamin Cohen in 2005.

It closely follows political progress on LGBT rights aro ...

launched. It is marketed towards the lesbian

A lesbian is a Homosexuality, homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate n ...

, gay, bisexual

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, or to more than one gender. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, whi ...

and transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through tr ...

(LGBT

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term is a ...

) community

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, tow ...

.

See also

*List of magazines in the United Kingdom

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby union ...

* List of newspapers in the United Kingdom

* The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

* The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

* The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

* Banging out

Banging out is a tradition in some British industries to mark the completion of an apprenticeship or a retirement of an employee. Particularly associated with the printing rooms of national newspapers in Fleet Street the "banging" is the noise ...

, a tradition in British newspapers relating to apprentices and retirees

References

Further reading

; Britain * Andrews, Alexander. ''The history of British journalism: from the foundation of the newspaper press in England, to the repeal of the Stamp act in 1855'' (1859)online old classic

* Boyce, D. G. "Crusaders without chains: power and the press barons 1896-1951" in J. Curran, A. Smith and P. Wingate, eds., ''Impacts and Influences: Essays on Media Power in the Twentieth Century'' (Methuen, 1987). * Briggs, Asa. ''The BBC—the First Fifty Years'' (Oxford University Press, 1984). * Briggs, Asa. ''The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom'' (Oxford UP, 1961). *

* Bingham, Adrian. ''Gender, Modernity, and the Popular Press in Inter-War Britain'' (Oxford UP, 2004). * Brooker, Peter, and Andrew Thacker, eds. ''The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume I: Britain and Ireland 1880-1955'' (2009) * Viscount Camrose. ''Brutish Newspapers And Their Controllers'' (1947

online

ownership of all major papers in 1947 * Clarke, Bob. ''From Grub Street to Fleet Street: An Illustrated History of English Newspapers to 1899'' (Ashgate, 2004) * Conboy, Martin. ''Journalism in Britain: a historical introduction'' (2011). * Cox, Howard and Simon Mowatt. ''Revolutions from Grub Street: A History of Magazine Publishing in Britain'' (2015

excerpt

* Crisell, Andrew ''An Introductory History of British Broadcasting.'' (2nd ed. 2002). * Griffiths, Dennis. ''The Encyclopedia of the British press, 1422-1992'' (Macmillan, 1992). * Hampton, Mark. "Newspapers in Victorian Britain." ''History Compass'' 2#1 (2004). Historiography * Harrison, Stanley (1974). ''Poor Men's Guardians: a Survey of the Democratic and Working-class Press''. London: Lawrence & Wishart. {{ISBN, 0-85315-308-6 * Herd, Harold. ''The March of Journalism: The Story of the British Press from 1622 to the Present Day'' (1952). * Jones, Aled. ''Powers of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth-Century England'' (1996). * Jones, Aled. ''Press, Politics and Society: a history of journalism in Wales'' (U of Wales Press, 1993). *

Koss, Stephen E.

Stephen Edward Koss (1940 – 25 October 1984) was an American historian specialising in subjects relating to Britain.

Koss received his BA, MA, and PhD from Columbia University, where he was a student of R.K. Webb. He began his academic ca ...

''The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain: the Nineteenth Cenlurv;'' ''The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain: The Twentieth Century.'' (2 vol. 1984), detailed scholarly study

* Lee, A. J. ''The Origins of the Popular Press in England, 1855–1914'' (1976).

* McNair, Brian. ''News and Journalism in the UK'' (Routledge, 2009).

* Marr, Andrew. ''My trade: a short history of British journalism'' (2004)

* Merrill, John C. and Harold A. Fisher. ''The world's great dailies: profiles of fifty newspapers'' (1980) pp 320–29

* Morison, Stanley. ''The History of the Times: Volume 1: The "Thunderer" in the Making 1785-1841.'' Volume 2: ''The Tradition Established 1841-1884.'' Volume 3: ''The Twentieth Century Test 1884-1912.'' Volume 4 : ''The 150th Anniversary and Beyond 1912-1948.'' (2 parts 1952)

* O'Malley, Tom, Stuart Allan, and Andrew Thompson. "Tokens of antiquity: The newspaper press and the shaping of national identity in Wales, 1870–1900 " ''Media History'' 3.1-2 (1995): 127–152.

* Perkin, H. J. "The Origins of the Popular Press" ''History Today'' (July 1957) 7#7 pp 425-435.

* Robinson, W. Sydney. ''Muckraker: The Scandalous Life and Times of WT Stead, Britain's First Investigative Journalist'' (Biteback Publishing, 2012).

* Scannell, Paddy, and Cardiff, David. ''A Social History of British Broadcasting, Volume One, 1922-1939'' (Basil Blackwell, 1991).

* Silberstein-Loeb, Jonathan. ''The International Distribution of News: The Associated Press, Press Association, and Reuters, 1848–1947'' (2014).

* Wiener, Joel H. "The Americanization of the British press, 1830—1914." ''Media History'' 2#1-2 (1994): 61–74.

; International context

* Burrowes, Carl Patrick. "Property, Power and Press Freedom: Emergence of the Fourth Estate, 1640-1789," ''Journalism & Communication Monographs'' (2011) 13#1 pp2–66, compares Britain, France, and the United States

* Collins, Ross F. and E. M. Palmegiano, eds. ''The Rise of Western Journalism 1815-1914: Essays on the Press in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain and the United States'' (2007)

* Conboy, Martin. ''Journalism: A Critical History'' (2004)

* Crook; Tim. ''International Radio Journalism: History, Theory and Practice'' (Routledge, 1998online

* Dooley, Brendan, and Sabrina Baron, eds. ''The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe'' (Routledge, 2001) * Wolff, Michael. ''The Man Who Owns the News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch'' (2008) 446 page

excerpt and text search

A media baron in Australia, UK and the US

External links

Biographical dictionary of 24,000+ British and Irish journalists who died between 1800 and 1960

UK History of the United Kingdom by topic