Book Of Common Prayer (1559) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'', also called the Elizabethan prayer book, is the third edition of the ''

The 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'', also called the Elizabethan prayer book, is the third edition of the ''

The authorized worship of the Elizabethan church could be broken up into three categories: the first was the ''Litany'' and approved versions of the Elizabethan prayer book, the second included the 1559 Elizabethan primer and other authorized private devotionals, and the third being the compilations of occasionally authorized prayers that for celebrations and times of

The authorized worship of the Elizabethan church could be broken up into three categories: the first was the ''Litany'' and approved versions of the Elizabethan prayer book, the second included the 1559 Elizabethan primer and other authorized private devotionals, and the third being the compilations of occasionally authorized prayers that for celebrations and times of  By the

By the

The office's title, ''The Order of the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion'', was the same as the 1552 prayer book and retained through the 1662 prayer book. A rubric detailing the place where a priest should stand during the office from the 1552 prayer book was retained within both the Elizabethan Act of Uniformity and 1559 text, though Elizabeth almost immediately abrogated it. During the administration, two sentences from the preceding prayer books were, as Mark Chapman described, "somewhat incoherently combined" to form the following passage:

The 1559 prayer book removed the 1552 prayer book's Black Rubric, causing dismay among Puritans. A declaration on the definition of kneeling which implicitly denied the

The office's title, ''The Order of the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion'', was the same as the 1552 prayer book and retained through the 1662 prayer book. A rubric detailing the place where a priest should stand during the office from the 1552 prayer book was retained within both the Elizabethan Act of Uniformity and 1559 text, though Elizabeth almost immediately abrogated it. During the administration, two sentences from the preceding prayer books were, as Mark Chapman described, "somewhat incoherently combined" to form the following passage:

The 1559 prayer book removed the 1552 prayer book's Black Rubric, causing dismay among Puritans. A declaration on the definition of kneeling which implicitly denied the

The intentions behind the 1559 prayer book, particularly the narrative of Elizabeth's pursuit of a ''

The intentions behind the 1559 prayer book, particularly the narrative of Elizabeth's pursuit of a ''

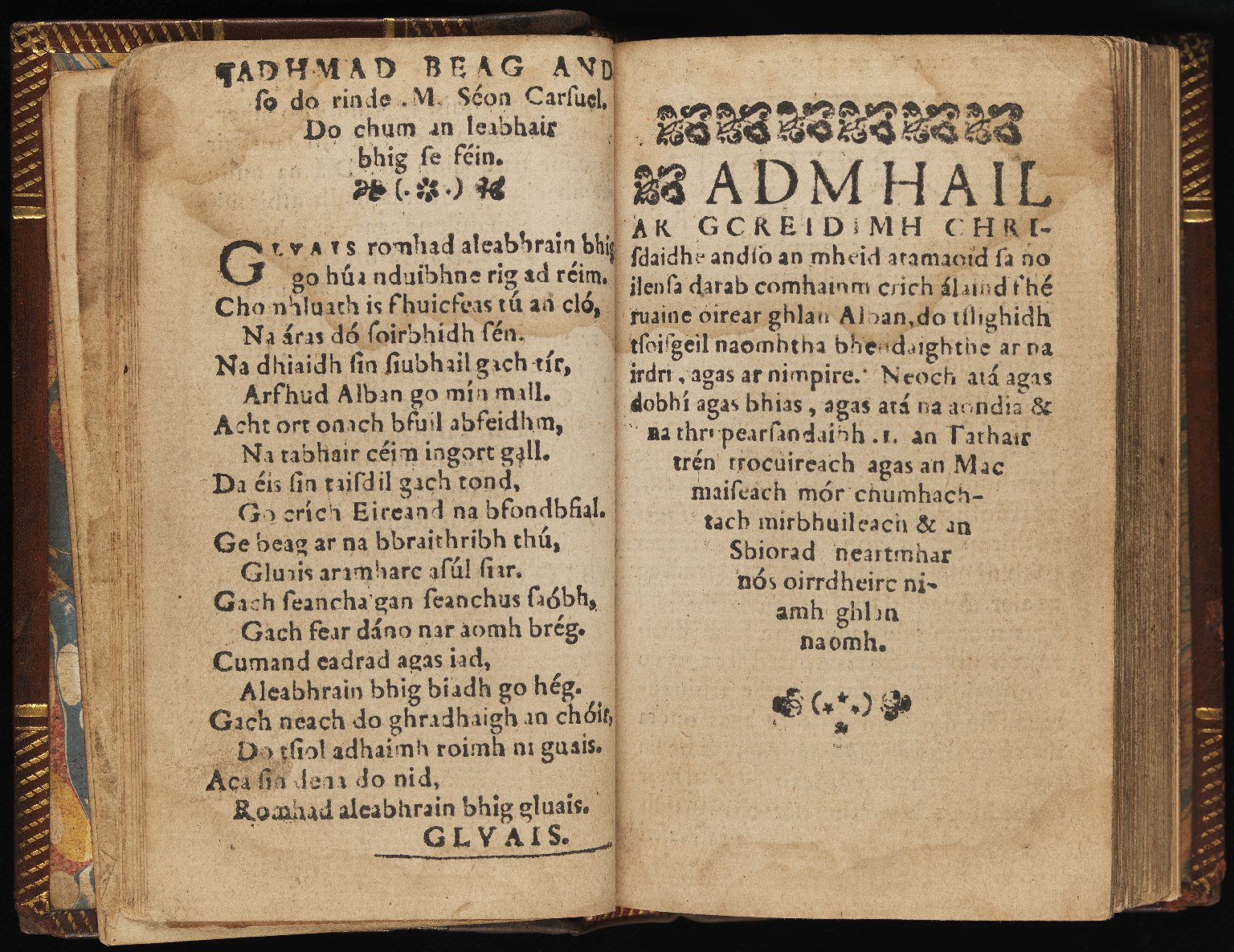

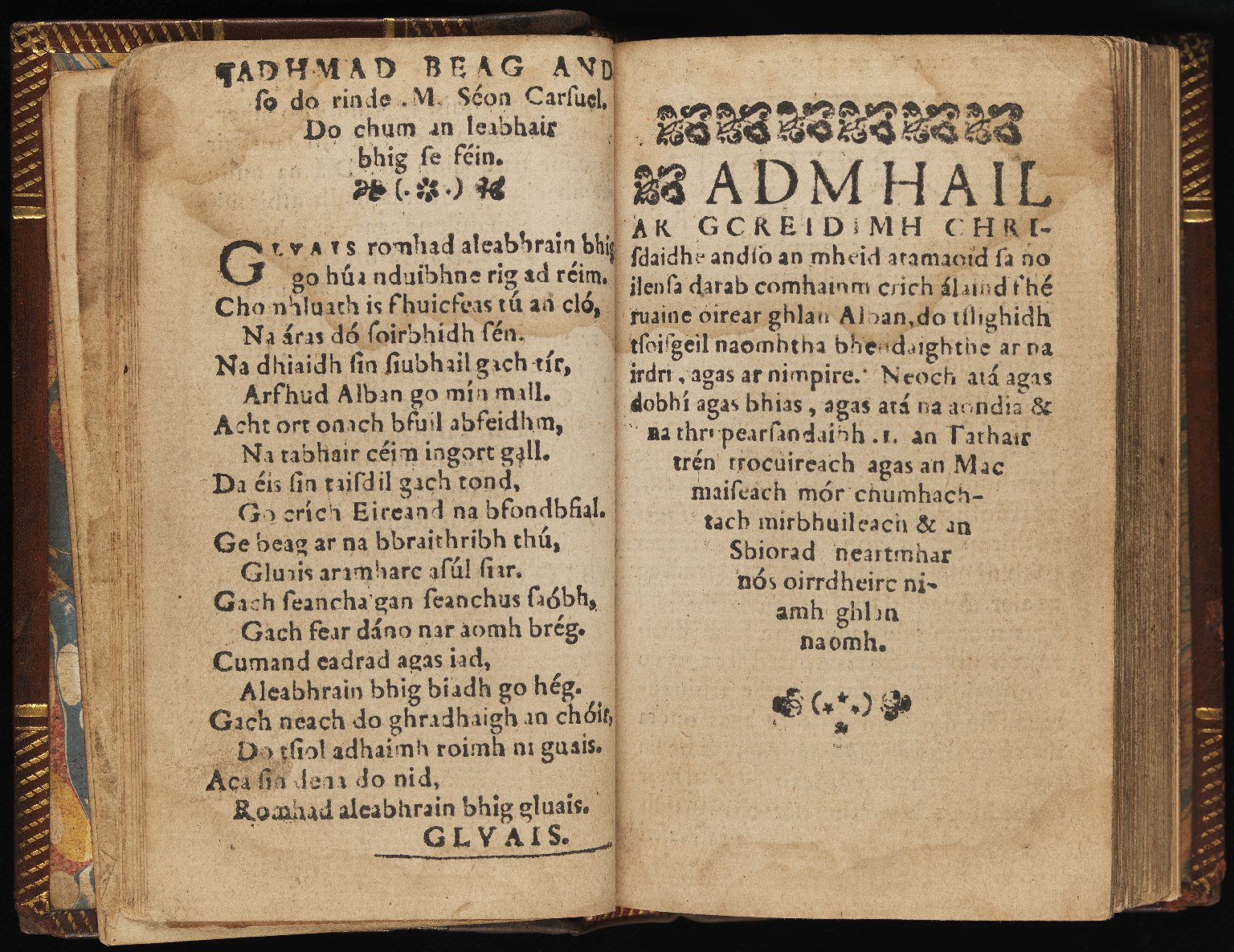

''The Booke of common praier and administration of the Sacramentes and other rites and Ceremonies in the Churche of Englande''

a digitized copy of the 1559 prayer book printed in 1562 by Richard Jugge and held by the

Choral Latin Evensong according to the 1560 ''Liber Precum Publicarum''

a recreation of choral Evensong from the 1560 ''Liber Precum Publicarum'' performed by the Oxford-based ensemble Antiquum Documentum in the

The 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'', also called the Elizabethan prayer book, is the third edition of the ''

The 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'', also called the Elizabethan prayer book, is the third edition of the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'' and the text that served as an official liturgical book

A liturgical book, or service book, is a book published by the authority of a church body that contains the text and directions for the liturgy of its official religious services.

Christianity Roman Rite

In the Roman Rite of the Catholic ...

of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

throughout the Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

.

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

became Queen of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

in 1558 following the death of her Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

half-sister Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

. After a brief period of uncertainty regarding how much the new queen would embrace the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

, the 1559 prayer book was approved as part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the E ...

. The 1559 prayer book was largely derived from the 1552 ''Book of Common Prayer'' approved under Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

. Retaining much of Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry' ...

's work from the prior edition, it was used in Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

liturgy until a minor revision in 1604 under Elizabeth's successor, James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

. The 1559 pattern was again retained by the 1662 ''Book of Common Prayer'', which remains in use by the Church of England.

The 1559 prayer book and its use throughout Elizabeth's 45-year reign secured the ''Book of Common Prayer''s prominence in the Church of England and is considered by many historians as embodying the Elizabethan church's drive for a ''via media

''Via media'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the middle road" and is a philosophical maxim for life which advocates moderation in all thoughts and actions.

Originating from the Delphic Maxim ''nothing to excess'' and subsequent Ancient Greek philosop ...

'' between Protestant and Catholic impulses and cementing the church's particular strain of Protestantism. Others have assessed it as an achievement in Elizabeth's commitment to an evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

and stridently Protestant faith.

The text became integrated with late 16th-century English society and the diction used within the 1559 prayer book has been credited with helping mould the English language's modern form. Historian Eamon Duffy

Eamon Duffy (born 1947) is an Irish historian. He is a professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow and former president of Magdalene College.

Early life

Duffy was born on 9 February 1947, in Dundalk, I ...

considered the Elizabethan prayer book an embedded and stable "re-formed" development out of medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

piety that "entered and possessed" the minds of the English people. A. L. Rowse

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan England and books relating to Cornwall.

Born in Cornwall and raised in modest circumstances, he was encourag ...

asserted that "it is impossible to over-estimate the influence of the Church's routine of prayer".

History

Edwardine prayer books and Mary's reign

WhenEdward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

succeeded his father Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

as King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

in 1547 on the latter's death, the young king's regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

council encouraged the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

and its associated Protestant liturgical reforms in England. These reforms would be undertaken by Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry' ...

, the archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, who had already performed revisions under Henry such as to the litany

Litany, in Christian worship and some forms of Judaic worship, is a form of prayer used in services and processions, and consisting of a number of petitions. The word comes through Latin ''litania'' from Ancient Greek λιτανεία (''litan ...

in 1544. Cranmer was familiar with contemporary Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

developments as well as the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

efforts to reform the ''Roman Breviary

The Roman Breviary (Ecclesiastical Latin, Latin: ''Breviarium Romanum'') is a breviary of the Roman Rite in the Catholic Church. A liturgical book, it contains public or canonical Catholic prayer, prayers, hymns, the Psalms, readings, and notati ...

'' under Cardinal Quiñones. Cranmer's royally authorized 1548 ''Order of the Communion'' introduced an English-language devotion into the Latin Mass Latin Mass may refer to:

* Liturgical use of Latin

** Mass of Paul VI in Latin

* Tridentine Mass

** As part of the use of preconciliar rites after the Second Vatican Council

* Some liturgies of the Pre-Tridentine Mass

See also

* ''Latin Mass Magaz ...

along the lines of work done by Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer ( early German: ''Martin Butzer''; 11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a me ...

and Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

in Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

. On Pentecost Sunday

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christian holiday which takes place on the 50th day (the seventh Sunday) after Easter Sunday. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers of ...

1549, the first ''Book of Common Prayer'' was issued under an Act of Uniformity and replaced the Latin rites

Latin liturgical rites, or Western liturgical rites, are Catholic rites of public worship employed by the Latin Church, the largest particular church ''sui iuris'' of the Catholic Church, that originated in Europe where the Latin language once ...

for service in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

.

The first prayer book reflected a variety of influences. Cranmer may have introduced an Epiclesis

The epiclesis (also spelled epiklesis; from grc, ἐπίκλησις "surname" or "invocation") refers to the invocation of one or several gods. In ancient Greek religion, the epiclesis was the epithet used as the surname given to a deity in reli ...

into the 1549 Communion canon based on familiarity with the Divine Liturgies of Saint John Chrysostom and Saint Basil

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great ( grc, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, ''Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas''; cop, Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ; 330 – January 1 or 2, 379), was a bishop of Ca ...

. Other services were derived from the Use of Sarum

The Use of Sarum (or Use of Salisbury, also known as the Sarum Rite) is the Latin liturgical rite developed at Salisbury Cathedral and used from the late eleventh century until the English Reformation. It is largely identical to the Roman rite, ...

(the liturgical use of Salisbury Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, is an Anglican cathedral in Salisbury, England. The cathedral is the mother church of the Diocese of Salisbury and is the seat of the Bishop of Salisbury.

The buildi ...

) and still others were translations of the old rites from Latin into English. A rubric

A rubric is a word or section of text that is traditionally written or printed in red ink for emphasis. The word derives from the la, rubrica, meaning red ochre or red chalk, and originates in Medieval illuminated manuscripts from the 13th cent ...

prohibited the Catholic practice of elevating the Communion elements, and other Protestant interpolations and simplifications appear throughout the text. Though some Catholics such as the imprisoned bishop Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 – 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip.

Early life

Gardiner was b ...

assessed the 1549 Communion rite as "not distant from the Catholic faith", peasants in the West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Gloucesters ...

launched the unsuccessful Prayer Book Rebellion

The Prayer Book Rebellion or Western Rising was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon in 1549. In that year, the ''Book of Common Prayer'', presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduced. The change was widely unpopular, ...

partially as a bid to restore the old rites.

Despite resistance, the English Reformation and its liturgical developments continued. The primer

Primer may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Primer'' (film), a 2004 feature film written and directed by Shane Carruth

* ''Primer'' (video), a documentary about the funk band Living Colour

Literature

* Primer (textbook), a t ...

issued under Henry was further reformed with the Hail Mary

The Hail Mary ( la, Ave Maria) is a traditional Christian prayer addressing Mary, the mother of Jesus. The prayer is based on two biblical passages featured in the Gospel of Luke: the Angel Gabriel's visit to Mary (the Annunciation) and Mary's ...

deleted while Latin liturgical book

A liturgical book, or service book, is a book published by the authority of a church body that contains the text and directions for the liturgy of its official religious services.

Christianity Roman Rite

In the Roman Rite of the Catholic ...

s were defaced. The first Edwardine Ordinal appeared in 1550; its vesting

In law, vesting is the point in time when the rights and interests arising from legal ownership of a property is acquired by some person. Vesting creates an immediately secured right of present or future deployment. One has a vested right to an ...

rubrics proved insufficiently reformed for John Hooper, who convinced the young king to authorize more reformed vestment regulations in the subsequent ordinal and prayer book. Cranmer's work in the 1552 ''Book of Common Prayer''–authorized for introduction on All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the church, whether they are know ...

that year by another Act of Uniformity–further directed English worship towards Protestantism. The Black Rubric

The term Black Rubric is the popular name for the declaration found at the end of the "Order for the Administration of the Lord's Supper" in the ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP), the Church of England's liturgical book. The Black Rubric explains why ...

, which was added to 1552 text after parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

had approved it, was a notable result of Protestant pressure from Hooper, John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

, Nicholas Ridley, and Peter Martyr Vermigli

Peter Martyr Vermigli (8 September 149912 November 1562) was an Italian-born Reformed theologian. His early work as a reformer in Catholic Italy and his decision to flee for Protestant northern Europe influenced many other Italians to convert a ...

. It explained that kneeling in the Communion office did not imply Eucharistic adoration nor " any real and essential presence there being of Christ's natural flesh and blood".

The momentum towards Protestantism was halted after Edward's death on 6 July 1553, which led to the accession of his Catholic half-sister, Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

. Prior to her accession, Mary had her chaplains celebrate Mass according to the pre-prayer book rites. According to Charles Wriothesley

Charles Wriothesley ( ''REYE-əths-lee''; 8 May 1508 – 25 January 1562) was a long-serving officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. He was the last member of a dynasty of heralds that started with his grandfather— Garter Principal Ki ...

's ''Chronicle

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

'', some London parishes restored the Latin Mass of their own accord upon Mary's accession. Liturgical books that were supposed to have been defaced or destroyed under Edward reemerged, sometimes without damage. However, the new queen soon proved unpopular. Her efforts to restore English religion to the state it had existed in before Henry's reforms–alongside her marriage to the Spanish Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

–brought opposition, not least due to the financial costs involved. Many prominent Protestant fled to avoid becoming imprisoned or executed during the Marian persecutions

Protestants were executed in England under heresy laws during the reigns of Henry VIII (1509–1547) and Mary I (1553–1558). Radical Christians also were executed, though in much smaller numbers, during the reigns of Edward VI (1547–1553) ...

. These exiles

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

in Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

became influenced by the worship patterns of Protestants in Frankfurt and John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

's Geneva. Before her death in 1558, Mary's efforts had claimed Cranmer's life.

Elizabeth's succession, revision, and adoption

Elizabeth succeeded Mary as queen on 17 November 1558. During her sister's reign, Elizabeth had outwardly embodied worship in conformity to the Catholic practices Mary had promoted. However, there were widespread rumours that Elizabeth's faith more approximated that of her half-brother Edward VI. Elizabeth did not firmly pronounce her preferences before her first parliament sat. However, the early years of her reign would be marked by both theElizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the E ...

and a restoration of the Edwardine patterns of "matters and ceremonies of religion".

By December 1558, rumours circulated that the English ''Litany'' had been restored in Elizabeth's Chapel Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also applie ...

. On Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus, Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by country, around t ...

, the celebrating bishop refused Elizabeth's request that he refrain from elevating the sacramental host, leading her to leave the chapel after singing the gospel. She appointed Richard Jugge

Richard Jugge (died 1577) was an eminent English printer, who kept a shop at the sign of the Bible, at the North door of St Paul's Cathedral, though his residence was in Newgate market, next to Christ Church in London. He is generally credited a ...

as the Queen's Printer

The King's Printer (known as the Queen's Printer during the reign of a female monarch) is typically a bureau of the national, state, or provincial government responsible for producing official documents issued by the King-in-Council, Ministers o ...

and had him print a pamphlet containing a version of the Cranmerian ''Litany'' for use in the Chapel Royal at the beginning of 1559; Jugge was joined by John Cawood, who had held the position under Mary and was eventually reinstated by Elizabeth. At her coronation on 15 January 1559 and the 25 January opening of parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes place ...

–both at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

–Elizabeth eschewed some ceremonial aspects of the events and processed in with the Chapel Royal singers rather than the typical monks.

On 9 February 1559, a Bill of Supremacy was introduced in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

to restore the Church of England's independence that had been lost under Mary. It was met with opposition from both Mary's bishops and some in the reformed party. J. E. Neale

Sir John Ernest Neale (7 December 1890 in Liverpool – 2 September 1975) was an English historian who specialised in Elizabethan and Parliamentary history. From 1927 to 1956, he was the Astor Professor of English History at University Coll ...

believed this bill's permission for Communion under both kinds

Communion under both kinds in Christianity is the reception under both "species" (i.e., both the consecrated bread and wine) of the Eucharist. Denominations of Christianity that hold to a doctrine of Communion under both kinds may believe that ...

indicates that Elizabeth and her advisors were unwilling to pursue a new Act of Uniformity during the queen's first parliament, as this allowance would have been made superfluous by the latter legislation. Parliament committed the supremacy bill to two returned Marian exiles, Anthony Cooke

Sir Anthony Cooke (1504 – 11 June 1576) was an English humanist scholar. He was tutor to Edward VI.

Family

Anthony Cooke was the only son of John Cooke (died 10 October 1516), esquire, of Gidea Hall, Essex, and Alice Saunders (died 1510), da ...

and Francis Knollys, on 15 February after lengthy debate.

Subsequently, two bills were introduced on 15 and 16 February to establish an English liturgy, though without support from the government. Neale believed these proposals referred to either the 1552 prayer book or a revised Frankfurt liturgy. These bills quickly disappeared but likely contributed to Cooke and Knollys including provisions for an English liturgy in the Bill of Supremacy as reintroduced by their committee on 21 February. On 3 March, the conservative Convocation of Canterbury

The Convocations of Canterbury and York are the synodical assemblies of the bishops and clergy of each of the two provinces which comprise the Church of England. Their origins go back to the ecclesiastical reorganisation carried out under Arc ...

delivered their decisions in opposition to the supremacy bill to Lord Keeper

The Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England, and later of Great Britain, was formerly an officer of the English Crown charged with physical custody of the Great Seal of England. This position evolved into that of one of the Great Officers of Sta ...

Nicholas Bacon to no apparent effect. The liturgical provisions were removed from the bill as a concession to conservatives in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, passing there on 22 March. With this, Elizabeth became Supreme Governor of the Church of England

The supreme governor of the Church of England is the titular head of the Church of England, a position which is vested in the British monarch. Queen and Church > Queen and Church of England">The Monarchy Today > Queen and State > Queen and Chur ...

.

This frustrated the reformed party in Commons which wished to expel the papacy from English affairs but also considered the lack of liturgical revision unacceptable. Elizabeth may have been content with this outcome, willing to incrementally introduce the minor reforms initially implemented in her chapel. However, the increasing threat posed by both emboldened Marian conservatives and disaffected reformers in Commons meant that the post-Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

parliamentary proceedings would emphasize liturgical revision. On 22 March, the Wednesday

Wednesday is the day of the week between Tuesday and Thursday. According to international standard ISO 8601, it is the third day of the week. In countries which have Friday as their holiday, Wednesday is the fifth day of the week. In countries ...

of Holy Week

Holy Week ( la, Hebdomada Sancta or , ; grc, Ἁγία καὶ Μεγάλη Ἑβδομάς, translit=Hagia kai Megale Hebdomas, lit=Holy and Great Week) is the most sacred week in the liturgical year in Christianity. In Eastern Churches, w ...

, Elizabeth intended to issue a proclamation permitting all Englishmen to receive Communion in both kinds in defiance of the Catholic practice. Though this proclamation went unissued, it was printed and made implicit reference to restoring the 1548 ''Order of the Communion'' or a similar liturgical supplement. By Easter, Elizabeth was privately receiving Communion in both kinds, though–contrary to some historical speculation–did not introduce the 1552 prayer book on that date as it would have undermined her legal legitimacy.

On Easter Monday

Easter Monday refers to the day after Easter Sunday in either the Eastern or Western Christian traditions. It is a public holiday in some countries. It is the second day of Eastertide. In Western Christianity, it marks the second day of the Octa ...

, John Jewel

John Jewel (''alias'' Jewell) (24 May 1522 – 23 September 1571) of Devon, England was Bishop of Salisbury from 1559 to 1571.

Life

He was the youngest son of John Jewel of Bowden in the parish of Berry Narbor in Devon, by his wife Alice Bell ...

wrote to fellow returned Marian exile Peter Martyr of a planned disputation between the Marian conservatives and the reformers. Simultaneously, Elizabeth began floating the idea of "the Mass being said in English". The privy council selected three subjects for the debate: the necessity of vernacular liturgy, whether a national church had a right to prescribe its own liturgy, and whether the Mass was a propitiatory sacrifice. This disputation, perhaps arranged during the lull between the Bill of Supremacy's initial debate and passage in the House of Lords, was intended to secure the Protestant side's success. The Westminster Disputation's first session on 31 March likely indicated that the Marian bishops would not concede the departure from papal authority and, before the 3 April second session could begin, the entire papalist party was arrested. Conservative will was broken. An Uniformity bill was read in Commons on 18 April and was passed ten days later with limited opposition in the House of Lords. The Commons passed a supremacy bill declaring Elizabeth "supreme governor"–a title they had initially rejected in favour of "supreme head"–on 29 April.

The book attached to the Act of Uniformity 1558

The Act of Uniformity 1558 was an Act of the Parliament of England, passed in 1559, to regularise prayer, divine worship and the administration of the sacraments in the Church of England. The Act was part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement ...

was the 1552 prayer book, though with what Bryan D. Spinks called "significant, if not totally explicable, alterations." Among the changes was the removal of the explanatory Black Rubric from the Communion service. Also removed were the prayers against the pope in the ''Litany''. The new Ornaments Rubric The "Ornaments Rubric" is found just before the beginning of Morning Prayer in the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England. It runs as follows:

The interpretation of the second paragraph was debated when it first appeared and became a major i ...

, while not the subject of debate at the time of adoption, was vague regarding what vestments it permitted. Printing rights for the newly adopted prayer book were solely extended to the Queen's Printers, a monopoly that reflected the text's value to the state. The prayer book was used in the queen's chapel on 12 May and legally introduced on the Feast of St. John the Baptist

The Nativity of John the Baptist (or Birth of John the Baptist, or Nativity of the Forerunner, or colloquially Johnmas or St. John's Day (in German) Johannistag) is a Christian feast day celebrating the birth of John the Baptist. It is observed ...

, 24 June.

Use and opposition

The authorized worship of the Elizabethan church could be broken up into three categories: the first was the ''Litany'' and approved versions of the Elizabethan prayer book, the second included the 1559 Elizabethan primer and other authorized private devotionals, and the third being the compilations of occasionally authorized prayers that for celebrations and times of

The authorized worship of the Elizabethan church could be broken up into three categories: the first was the ''Litany'' and approved versions of the Elizabethan prayer book, the second included the 1559 Elizabethan primer and other authorized private devotionals, and the third being the compilations of occasionally authorized prayers that for celebrations and times of fasting

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see " Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after ...

. The Act of Uniformity that introduced the 1559 prayer book had also required conformity to it and mandated Sunday attendance, with fines for all those who failed to attend. Of roughly 9,400 Church of England clergy, around 189 refused the 1559 prayer book on adoption and were deprived of their benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

s. Despite this, the act also provided for variety in allowing the queen to order and publish additional texts. Elizabeth exercised this right on 6 April 1560 to publish ''Liber Precum Publicarum'', a Latin version of the prayer book for use in collegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by a ...

es. The 1560 Latin prayer book included alterations which reflected a "practical conservatism" and reversion to the forms present within the Latin translation of the 1549 prayer book.

The prayer book provided thorough guidance on some ceremonial aspects but provided space for interpretation on others. Among those aspects of the prayer book left obliquely addressed was the presence of music. Liturgical music

Liturgical music originated as a part of religious ceremony, and includes a number of traditions, both ancient and modern. Liturgical music is well known as a part of Catholic Mass, the Anglican Holy Communion service (or Eucharist) and Evensong ...

, particularly the compositions of Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one o ...

and the Catholic recusant

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English composer of late Renaissance music. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native England and those on the continent. He ...

for the Chapel Royal, was built around and in relationship with the Elizabethan prayer book. In cathedrals, collegiate churches, and chapels, music by Byrd, John Bull

John Bull is a national personification of the United Kingdom in general and England in particular, especially in political cartoons and similar graphic works. He is usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling, jolly and matter- ...

, Thomas Morley

Thomas Morley (1557 – early October 1602) was an English composer, theorist, singer and organist of the Renaissance. He was one of the foremost members of the English Madrigal School. Referring to the strong Italian influence on the Englis ...

, Robert White, and others appeared in both in English and Latin for use with organs

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a fu ...

and choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

s at prayer book services. However, through the 1570s, the death of organ repairers and rising inflation meant that these conservative practices grew rarer.

In 1564, the deprived Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

Edmund Bonner

Edmund Bonner (also Boner; c. 15005 September 1569) was Bishop of London from 1539 to 1549 and again from 1553 to 1559. Initially an instrumental figure in the schism of Henry VIII from Rome, he was antagonised by the Protestant reforms intro ...

challenged the legality of the 1559 ordinal. Bonner had been called to swear the oath of supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy required any person taking public or church office in England to swear allegiance to the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Failure to do so was to be treated as treasonable. The Oath of Supremacy was ori ...

by Bishop Robert Horne, but Bonner declared that he did not considered Horne a bishop: the ordinal had not been mentioned in the Elizabethan Act of Uniformity, meaning that the ordinations and consecrations were technically irregular. In order to avoid a ruling on the matter, the case was dropped and, in 1566, parliament voted to retroactively authorize the 1559 ordinal and approve the ordinations that had taken place according to it.

Further discord arose regarding the Vestiarian controversy, a debate that had originated with Hooper under Edward and would continue under Elizabeth. The debate over which clerical vestments were appropriate for an English reformed church was excited by both the ambiguity of the 1559 prayer book's Ornaments Rubric and Elizabeth's promotion of vestments within her Chapel Royal. From 1559 until 1563, episcopal visitations provided a mechanism for enforcing the rubrics of the prayer book and allowed for additional regulation that furthered the reformed cause. Some bishops also met during this period and produced the "Interpretation of the Bishops", a resolution intended for acceptance by Convocation that clarified regulations and expectations for worship.

By the

By the Convocation of 1563

The Convocation of 1563 was a significant gathering of English and Welsh clerics that consolidated the Elizabethan religious settlement, and brought the ''Thirty-Nine Articles'' close to their final form (which dates from 1571). It was, more accu ...

, the prayer book had become entrenched such that even staunch reformers who resented the prayer book's proximity to Catholic ritual and ceremonial practices did not propose any major revisions. Instead, these reformers wanted the 1563 Convocation to perfect the prayer book's rubrics to their preferences. Their proposals engaged with the same matter that the queen and bishops had already issued guidance on, and the proposals generally trended towards standardizing English parish worship upon Continental Protestant lines. The visitations and regulations established by the bishops between 1559 and 1563 had meant that, outside the exceptions of the Chapel Royal and cathedrals, worship according to a reformed interpretation of the prayer book was becoming normative. After several failed attempts at compromise, Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker

Matthew Parker (6 August 1504 – 17 May 1575) was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 until his death in 1575. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder (with a p ...

's 1566 ''Advertisements

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a product or service. Advertising aims to put a product or service in the spotlight in hopes of drawing it attention from consumers. It is typically used to promote a ...

'' put an end to the encroaching Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

restrictions on vesting.

Still, Continental and Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

reformed worship continued to pressure the 1559 prayer book. Knox had introduced his version of John Calvin's ''La Forme des Prières'' to Scotland in 1559. Later approved by the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

as the ''Book of Common Order

The ''Book of Common Order'' is the name of several directories for public worship, the first originated by John Knox for use on the continent of Europe and in use by the Church of Scotland since the 16th century. The Church published revised ed ...

'', this Genevan pattern was being secretly used in London by 1567. After a revised version of this text was printed in London in 1585, a bill was introduced to House of Commons to select it as a replacement for the 1559 prayer book. Elizabeth suppressed the text and imprisoned those behind it in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. Some turned to the Geneva Bible

The Geneva Bible is one of the most historically significant translations of the Bible into English, preceding the King James Version by 51 years. It was the primary Bible of 16th-century English Protestantism and was used by William Shakespear ...

with its Calvinist notes and catechism, which was occasionally bound with the 1559 prayer book after 1583. Others began acquiring smaller printings of the authorized prayer book for purposes of devotion and establishing confessional identity.

Though the 1552 prayer book had been taken to by the minister of Hugh Willoughby

Sir Hugh Willoughby (fl. 1544; died 1554) was an English soldier and an early Arctic voyager. He served in the court of and fought in the Scottish campaign where he was knighted for his valour. In 1553, he was selected by a company of London ...

's ill-fated Arctic expedition, the 1559 prayer book was the first English prayer book to reach the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

. Robert Wolfall

Robert Wolfall was an Anglican priest who served as chaplain to Martin Frobisher's third expedition to the Arctic. He celebrated the first Anglican (i.e. post-Reformation) Eucharist in what is now Canadian territory in 1578 in Frobisher Bay.

Wolf ...

, minister for Martin Frobisher

Sir Martin Frobisher (; c. 1535 – 22 November 1594) was an English seaman and privateer who made three voyages to the New World looking for the North-west Passage. He probably sighted Resolution Island near Labrador in north-eastern Canada ...

's 1578 expedition, was reported by Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America'' (1582) and ''The Pri ...

to have celebrated the Communion upon the expedition's arrival at Frobisher Bay

Frobisher Bay is an inlet of the Davis Strait in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the southeastern corner of Baffin Island. Its length is about and its width varies from about at its outlet into the Labrador Sea ...

in July.

Millenary Petition and replacement

Puritan objections to the Elizabethan prayer book persisted after the queen's death. With KingJames VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

arriving in England in 1603 to take up the English throne, Puritan ministers gave him the Millenary Petition

The Millenary Petition was a list of requests given to James I by Puritans in 1603 when he was travelling to London in order to claim the English throne. It is claimed, but not proven, that this petition had 1,000 signatures of Puritan ministers ...

calling for the full excision of Catholic influence from the church's religion. Among the petition's demands were the deletion of the words "priest" and "altar", the removal of any implication that ministers could pronounce or grant absolution, and ceasing the use of vestments. Perhaps either seeking to appear open-minded or for his appreciation of debate, James opened the Hampton Court Conference

The Hampton Court Conference was a meeting in January 1604, convened at Hampton Court Palace, for discussion between King James I of England and representatives of the Church of England, including leading English Puritans. The conference resulte ...

in January 1604.

The resultant 1604 prayer book was only slightly different from the 1559 text, with some more significant changes to the baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

al rite. A catechism was also added. The Hampton Court Conference's prayer book and new canons formed a continuation of the Elizabethan religious life until the wars of the 1640s.

Contents

The 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'' is a revision of the 1552 prayer book. The changes from the 1552 text have been described as building towards comprehension across the various parties within the Church of England. At its initial promulgation, the 1559 prayer book's rubrics permitted a wider variety of vestments and ornaments. TheKalendar

The liturgical year, also called the church year, Christian year or kalendar, consists of the cycle of liturgical seasons in Christian churches that determines when feast days, including celebrations of saints, are to be observed, and whi ...

increased the number of lessons

A lesson or class is a structured period of time where learning is intended to occur. It involves one or more students (also called pupils or learners in some circumstances) being taught by a teacher or instructor. A lesson may be either one ...

said throughout the year and reintroduced many saints' days first removed in the 1549 prayer book. Both the Ornaments Rubric and the Kalendar would be modified over the 1560s to become more palatable to the Puritan party.

Still, much was retained between editions: The Elizabethan prayer book's title was the same as the 1552. In keeping with both the 1549 and 1552 prayer books, the Visitation of the Sick attributed God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

as the cause of illness. As with both preceding prayer books, the largely unchanged 1559 prayer book's matrimonial office and allowance of lay baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

drew the ire of Puritans. The 1559 prayer book could at times provide extensive detail on how a rite was to be conducted, though its silence on some matters meant that individual congregations would often celebrate in distinct fashions. Not always explicitly addressed in the prayer book was its use alongside liturgical music

Liturgical music originated as a part of religious ceremony, and includes a number of traditions, both ancient and modern. Liturgical music is well known as a part of Catholic Mass, the Anglican Holy Communion service (or Eucharist) and Evensong ...

.

The 1560 Latin-language prayer book, the ''Liber Precum Publicarum'', was likely translated by Walter Haddon

Walter Haddon LL.D. (1515–1572) was an English civil lawyer, much involved in church and university affairs under Edward VI, Queen Mary, and Elizabeth I. He was a University of Cambridge humanist and reformer, and was highly reputed in his time ...

. Meant for use at the chapels of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, Eton Eton most commonly refers to Eton College, a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England.

Eton may also refer to:

Places

*Eton, Berkshire, a town in Berkshire, England

* Eton, Georgia, a town in the United States

* Éton, a commune in the Meuse dep ...

, and Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, its contents were different from those of the English 1559 prayer book to the chagrin of some Protestants; most Cambridge colleges

The University of Cambridge is composed of 31 Colleges within universities in the United Kingdom, colleges in addition to the academic departments and administration of the central University. Until the mid-19th century, both University of Cambri ...

reportedly refused to use it. Among the differences were the inclusion of a requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

service, epistlers and gospelers vested in cope

The cope (known in Latin as ''pluviale'' 'rain coat' or ''cappa'' 'cape') is a liturgical vestment, more precisely a long mantle or cloak, open in front and fastened at the breast with a band or clasp. It may be of any liturgical colours, litu ...

s, and sacramental reservation.

Morning and Evening Prayer

Morning Prayer took the role of the major Sunday service in smaller parishes, with Communion commonly occurring monthly, quarterly, or even more rarely. The typical Sunday service became the Morning Prayer, Litany, the first part of the Communion service, asermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

, and Evening Prayer Evening Prayer refers to:

: Evening Prayer (Anglican), an Anglican liturgical service which takes place after midday, generally late afternoon or evening. When significant components of the liturgy are sung, the service is referred to as "Evensong ...

with catechetical instruction.

The Ornaments Rubric appeared before Morning Prayer, with language that undid some of the anti-ceremonial components of the 1552 prayer book and established ornamentation and vesting along the lines of the 1549 prayer book. However, this rubric did not demand uniformity in practice. This did not prevent efforts from both those in favour of more traditional vesting practices and those with Puritan anti-vestment views from pushing the limits of this regulation. In the 19th century, this rubric was interpreted as having permitted Mass vestments, altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

s, and candles. Another rubric, again altering the 1552 pattern, provided detail on where a minister should stand during the Morning and Evening Prayer services.

Communion office

The office's title, ''The Order of the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion'', was the same as the 1552 prayer book and retained through the 1662 prayer book. A rubric detailing the place where a priest should stand during the office from the 1552 prayer book was retained within both the Elizabethan Act of Uniformity and 1559 text, though Elizabeth almost immediately abrogated it. During the administration, two sentences from the preceding prayer books were, as Mark Chapman described, "somewhat incoherently combined" to form the following passage:

The 1559 prayer book removed the 1552 prayer book's Black Rubric, causing dismay among Puritans. A declaration on the definition of kneeling which implicitly denied the

The office's title, ''The Order of the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion'', was the same as the 1552 prayer book and retained through the 1662 prayer book. A rubric detailing the place where a priest should stand during the office from the 1552 prayer book was retained within both the Elizabethan Act of Uniformity and 1559 text, though Elizabeth almost immediately abrogated it. During the administration, two sentences from the preceding prayer books were, as Mark Chapman described, "somewhat incoherently combined" to form the following passage:

The 1559 prayer book removed the 1552 prayer book's Black Rubric, causing dismay among Puritans. A declaration on the definition of kneeling which implicitly denied the real presence

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

There are a number of Christian denominati ...

at Communion, it still remained in popular knowledge and contemporary reports maintain that its contents were taught and published. The Black Rubric reappeared in the 1662 prayer book in a modified form.

Ordinal

The 1559 ordinal, derived from the 1552 Edwardine Ordinal, was not included in the prayer book's contents lists. It contained several slight differences from the prior edition, with minor variation between the 1559 printings by Grafton and Jugge. The Jugge ordinal's printing was divided between several printers, with the first quire printed by Jugge and John Kingston and the second quire printed by Richard Payne andWilliam Copland

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

. The ordinal was not always bound with the 1559 prayer book and the separate sale of each appears to have been planned; the ordinal became an integrated part of the prayer book in the 1662 edition.

The litany recited at the beginning of the 1559 diaconal

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

ordination rite is modified to replace Edward's name with Elizabeth's, swap pronouns, and remove the deprecation of the pope's "detestable enormities". A petition directed towards the ordinands included in the Edwardine ordinal is not missing in the 1559 ordinal. Grafton had included it, but the shared printing responsibility for the Jugge edition may have resulted in its accidental deletion. The diaconal ordination rite also contains what might have been the most significant change to the ordinal. The oath for the king's "supremacie" becomes one for the queen's "Soueraintee" and the pope is again no longer directly invoked. However, in what may have again been a result of the multiple printers behind the Jugge ordinal, the oath's title establishes it as one of "Soueraintee" but the rubric retains the word "supremacye". This discrepancy persisted in Anglican prayer books for over 300 years.

Appraisal and influence

For a long time the second-most diffuse book in England behind only the Bible, the 1559 prayer book had a significant impact on English society. It was a departure from the trajectory the previous prayer books had taken–one of reform growing closer to Continental European Protestant worship–but also not a reversion to 1549, maintaining Protestantism as a crucial component of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. The Elizabethan prayer book's longevity also distinguished it from its prayer book precedents, with its vernacular rites contributing to the linguistic environment that producedWilliam Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

; Shakespeare made reference to the prayer book's regular private use in his ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

''.

The 1559 prayer book was slightly revised in 1604, followed by a more substantial revision that produced the 1662 ''Book of Common Prayer'' still used by Anglicans today. Spinks identified the 1559 prayer book as the point at which the ''Book of Common Prayer'' became "the 'incomparable liturgy'", a "hegemony" he assessed as surviving until the 1906 Royal Commission on Ecclesiastical Discipline. According to historian John Booty, the revision in 1661 did little to change the tone from that of the Elizabethan prayer book, with its model remaining normative in England until the Prayer Book (Alternative and Other Services) Measure 1965.

Eamon Duffy

Eamon Duffy (born 1947) is an Irish historian. He is a professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow and former president of Magdalene College.

Early life

Duffy was born on 9 February 1947, in Dundalk, I ...

, in his ''The Stripping of the Altars

''The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580'' is a work of history written by Eamon Duffy and published in 1992 by Yale University Press. It received the Longman-''History Today'' Book of the Year Award.

Summ ...

'', maintained that medieval piety was not replaced by the Elizabethan prayer book but rather "re-formed itself around the rituals and words of the prayer-book." While lamenting that "traditional religion" was "much reduced in scope, depth, and coherence", Duffy acknowledged that the people's consistent usage of the 1559 prayer book's meant "Cranmer's sombrely magnificent prose, read week by week, entered and possessed their minds, and became the fabric of their prayer". A. L. Rowse

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan England and books relating to Cornwall.

Born in Cornwall and raised in modest circumstances, he was encourag ...

came to a similar conclusion, saying "it is impossible to over-estimate the influence of the Church's routine of prayer and good works upon that society".

Responding to the then-ongoing 1927–1928 Prayer Book Crisis to the adoption of the 1559 prayer book, William Joynson-Hicks

William is a male given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norm ...

compared the 16th-century episcopal resistance to Protestant liturgy to the bishops of his own time. Joynson-Hicks added that parliament was crucial in upholding the 1552 prayer book pattern in 1559, something he hoped would be repeated in 1928. However, he also lamented the lack of clarity within the Ornaments Rubric.

As a ''via media''

The intentions behind the 1559 prayer book, particularly the narrative of Elizabeth's pursuit of a ''

The intentions behind the 1559 prayer book, particularly the narrative of Elizabeth's pursuit of a ''via media

''Via media'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the middle road" and is a philosophical maxim for life which advocates moderation in all thoughts and actions.

Originating from the Delphic Maxim ''nothing to excess'' and subsequent Ancient Greek philosop ...

'', have been the subjects of debate among historians. The ''via media'' narrative–supported in the works of Brian Cummings

Brian Douglas Cummings (born March 4, 1948) is an American voice actor, known for his work in radio and television commercials, television and motion picture promos, cartoons and as the announcer on '' The All-New Let's Make a Deal'' from 1984 to ...

, J. E. Neale, and Walter Frere

Walter Howard Frere (23 November 1863 – 2 April 1938) was a co-founder of the Anglican religious order the Community of the Resurrection, Mirfield, and Bishop of Truro (1923–1935).

Biography

Frere was born in Cambridge, England, on 23 Nov ...

–describes the Elizabethan prayer book as a compromise between Catholic and Protestant influence. This view remains popular, appearing regularly in English textbooks and academic volumes despite modern criticism. The queen and her ministers are typically described as having favoured the Catholic-leaning 1549 prayer book in conflict with those of reformed inclination. According to this view, parliamentary debate gave way to resolution through the adoption of the more reformed 1552 prayer book but only with alterations that reduced its Protestant character. Proponents point to three pieces of evidence: the December 1558 "Device for the alteration of religion" (thought to have called for a committee of revision), a letter from Edmund Gheast

Edmund Gheast (also known as Guest, Geste or Gest; 1514–1577) was a 16th-century cleric of the Church of England.

Life

Guest was born at Northallerton, Yorkshire, the son of Thomas Geste. He was educated at York Grammar School and Eton College ...

to William Cecil (which suggests that the revising committee met), and the 1549 prayer book (which these accounts imply Elizabeth preferred). Both Frere and John Henry Blunt

John Henry Blunt (25 August 1823 in Chelsea – 11 April 1884 in London) was an English divine.

Life

Before going to the University College, Durham in 1850, he was for some years engaged in business as a manufacturing chemist. He was ordained in ...

held that these efforts established a continuity between the 1559 prayer book and the Latin service books of medieval England.

Some modern historians, including Stephen Alford

Stephen Alford FRHistS (born 1970) is a British historian and academic. He has been professor of early modern British history at the University of Leeds since 2012. Life

Educated at the University of St Andrews, he was formerly a British Academ ...

and Diarmaid MacCulloch

Diarmaid Ninian John MacCulloch (; born 31 October 1951) is an English academic and historian, specialising in ecclesiastical history and the history of Christianity. Since 1995, he has been a fellow of St Cross College, Oxford; he was former ...

, have sought to revise the ''via media'' narrative by attempting to demonstrate Elizabeth's deep-seated Protestantism. Revisionists maintain that Elizabeth intended to restore the 1552 prayer book from the outset of her reign rather than adapting it as a concession. Critics of the compromise narrative argue that it requires a narrow view towards historical evidence, which revisionists instead appraise as betraying a fundamentally reformed nature of the 1559 prayer book's origins. Responding to MacCulloch's claim that Elizabeth reestablished the Edwardine church as it had existed in September 1552, Bryan D. Spinks argued that the rituals in Elizabeth's Chapel Royal, the 1560 Latin version of the prayer book, and the Elizabethan primers indicated a less reformed church.

A prayer book printed in 1559 by Richard Grafton

Richard Grafton (c. 1506/7 or 1511 – 1573) was King's Printer under Henry VIII and Edward VI. He was a member of the Grocers' Company and MP for Coventry elected 1562-63.

Under Henry VIII

With Edward Whitchurch, a member of the Haberdashers ...

and now at Corpus Christi College, Oxford

Corpus Christi College (formally, Corpus Christi College in the University of Oxford; informally abbreviated as Corpus or CCC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1517, it is the 12th ...

, and signed by Elizabeth's privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

is held as evidence for the revisionist view. Formerly rejected as an unsanctioned text, the Corpus Christi prayer book is now interpreted as a legitimate and authorized text possibly intended for limited circulation with the Bill of Uniformity. The Corpus Christi prayer book contains alterations to the 1552 prayer book. As it is dated to early in the revision process and signed by Elizabeth's advisors, revisionists maintain that the Grafton printing demonstrates Elizabeth desire for a prayer book derived from the 1552 edition rather than initially promoting a reversion to the 1549 pattern. Historian Cyndia Susan Clegg has argued that the Corpus Christi prayer book marks Elizabeth as a strong evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

.

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* A resource on contemporary responses to the 1559 prayer book's revision and adoption * A thorough study of the ''Book of Common Prayer''s role in English social religion during the late 16th and early 17th centuries * A survey of the 1559 prayer book's social, religious, and literary influence during Elizabeth's reignExternal links

''The Booke of common praier and administration of the Sacramentes and other rites and Ceremonies in the Churche of Englande''

a digitized copy of the 1559 prayer book printed in 1562 by Richard Jugge and held by the

Boston Public Library

The Boston Public Library is a municipal public library system in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, founded in 1848. The Boston Public Library is also the Library for the Commonwealth (formerly ''library of last recourse'') of the Commonweal ...

Choral Latin Evensong according to the 1560 ''Liber Precum Publicarum''

a recreation of choral Evensong from the 1560 ''Liber Precum Publicarum'' performed by the Oxford-based ensemble Antiquum Documentum in the

Keble College

Keble College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Its main buildings are on Parks Road, opposite the University Museum and the University Parks. The college is bordered to the north by Keble Road, to th ...

chapel

{{Portalbar, Books, Christianity, England, History

1559 books

1559 in Christianity

1559 in England

Book of Common Prayer

History of the Church of England