Bolesław Prus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aleksander Głowacki (20 August 1847 – 19 May 1912), better known by his pen name Bolesław Prus (), was a Polish novelist, a leading figure in the history of Polish literature and

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in Hrubieszów, now in southeastern Poland, very near the present-day border with Ukraine. The town was then in the Russian-controlled sector of partitioned Poland, known as the " Congress Kingdom". Aleksander was the younger son of Antoni Głowacki, an estate steward at the village of

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in Hrubieszów, now in southeastern Poland, very near the present-day border with Ukraine. The town was then in the Russian-controlled sector of partitioned Poland, known as the " Congress Kingdom". Aleksander was the younger son of Antoni Głowacki, an estate steward at the village of  Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at Lublin Castle for his role in the Uprising. In early April a military court sentenced him to forfeiture of his nobleman's status and resettlement on imperial lands. On 30 April, however, the Lublin District military head credited Prus's time spent under arrest and, on account of the 16-year-old's youth, decided to place him in the custody of his uncle Klemens Olszewski. On 7 May, Prus was released and entered the household of Katarzyna Trembińska, a relative and the mother of his future wife, Oktawia Trembińska.

Prus enrolled at a

Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at Lublin Castle for his role in the Uprising. In early April a military court sentenced him to forfeiture of his nobleman's status and resettlement on imperial lands. On 30 April, however, the Lublin District military head credited Prus's time spent under arrest and, on account of the 16-year-old's youth, decided to place him in the custody of his uncle Klemens Olszewski. On 7 May, Prus was released and entered the household of Katarzyna Trembińska, a relative and the mother of his future wife, Oktawia Trembińska.

Prus enrolled at a

As a newspaper

As a newspaper  Though Prus was a gifted writer, initially best known as a humorist, he early on thought little of his journalistic and literary work. Hence at the inception of his career in 1872, at the age of 25, he adopted for his newspaper columns and fiction the

Though Prus was a gifted writer, initially best known as a humorist, he early on thought little of his journalistic and literary work. Hence at the inception of his career in 1872, at the age of 25, he adopted for his newspaper columns and fiction the

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic Hippolyte Taine's concept of the arts, including literature, as a second means, alongside the sciences, of studying reality, and he devoted more attention to his sideline of

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic Hippolyte Taine's concept of the arts, including literature, as a second means, alongside the sciences, of studying reality, and he devoted more attention to his sideline of

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's  In 1908, Prus serialized, in the Warsaw ''Tygodnik Ilustrowany'' (Illustrated Weekly), his novel ''Dzieci'' (Children), depicting the young revolutionaries, terrorists and anarchists of the day — an uncharacteristically humorless work. Three years later a final novel, ''Przemiany'' (Changes), was to have been, like '' The Doll'', a panorama of society and its vital concerns. However, in 1911 and 1912, the novel had barely begun serialization in the ''Illustrated Weekly'' when its composition was cut short by Prus's death.

Neither of the two late novels, ''Children'' or ''Changes'', is generally regarded as part of the essential Prus canon, and Czesław Miłosz has called ''Children'' one of Prus's weakest works.

Prus's last novel to meet with popular acclaim was '' Pharaoh'', completed in 1895. Depicting the demise of ancient Egypt's Twentieth Dynasty and

In 1908, Prus serialized, in the Warsaw ''Tygodnik Ilustrowany'' (Illustrated Weekly), his novel ''Dzieci'' (Children), depicting the young revolutionaries, terrorists and anarchists of the day — an uncharacteristically humorless work. Three years later a final novel, ''Przemiany'' (Changes), was to have been, like '' The Doll'', a panorama of society and its vital concerns. However, in 1911 and 1912, the novel had barely begun serialization in the ''Illustrated Weekly'' when its composition was cut short by Prus's death.

Neither of the two late novels, ''Children'' or ''Changes'', is generally regarded as part of the essential Prus canon, and Czesław Miłosz has called ''Children'' one of Prus's weakest works.

Prus's last novel to meet with popular acclaim was '' Pharaoh'', completed in 1895. Depicting the demise of ancient Egypt's Twentieth Dynasty and

On 3 December 1961, nearly half a century after Prus's death, a museum devoted to him was opened in the 18th-century Małachowski Palace at Nałęczów, near

On 3 December 1961, nearly half a century after Prus's death, a museum devoted to him was opened in the 18th-century Małachowski Palace at Nałęczów, near

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born, Hrubieszów, near the present Polish– Ukrainian border, is graced by an outdoor sculpture of him.

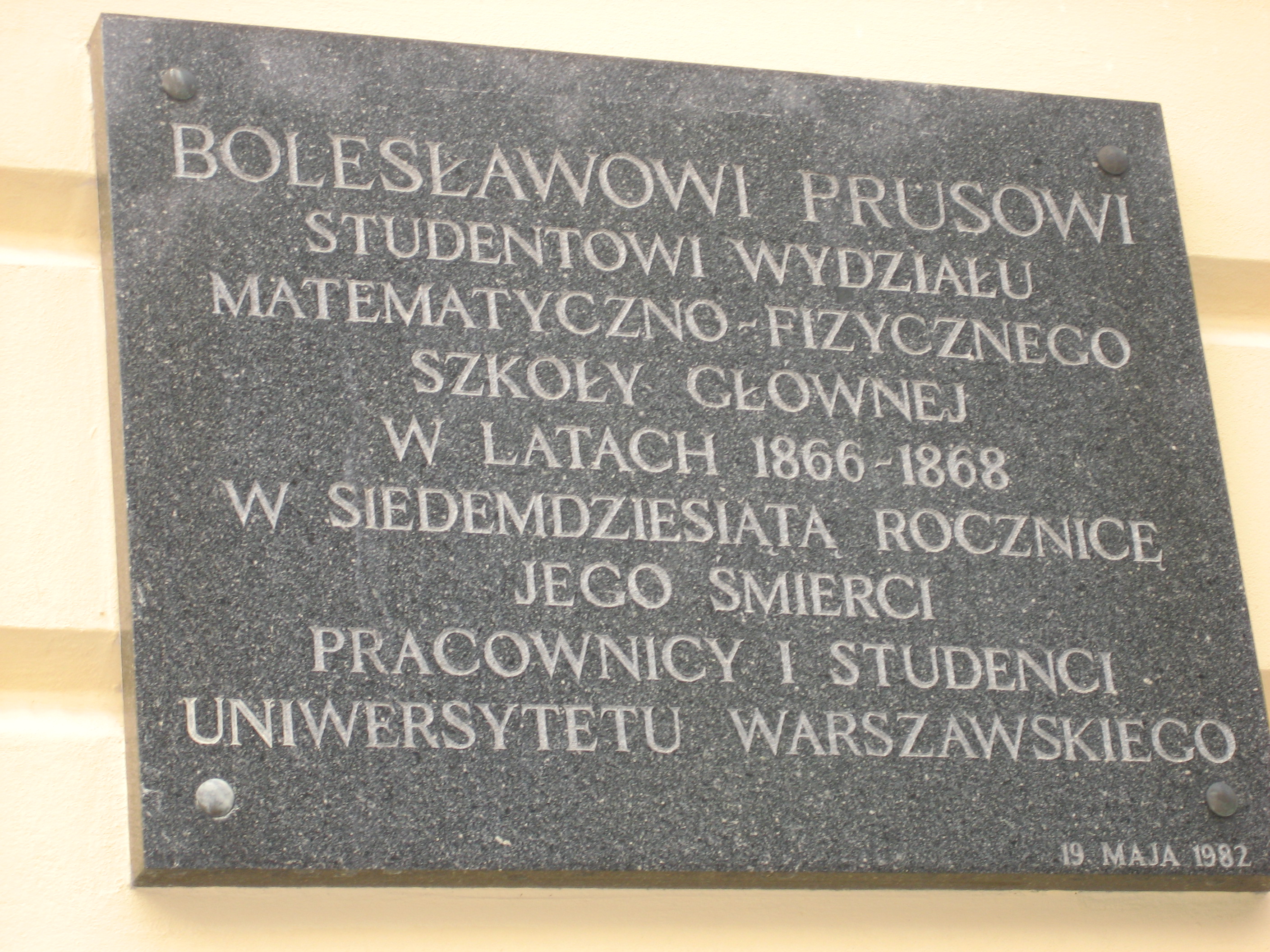

A 1982 plaque on Warsaw University's administration building, the historic Kazimierz Palace, commemorates Prus's years at the University in 1866–68. Across the street ('' Krakowskie Przedmieście'') from the University, in Holy Cross Church, a 1936 plaque by Prus's nephew

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born, Hrubieszów, near the present Polish– Ukrainian border, is graced by an outdoor sculpture of him.

A 1982 plaque on Warsaw University's administration building, the historic Kazimierz Palace, commemorates Prus's years at the University in 1866–68. Across the street ('' Krakowskie Przedmieście'') from the University, in Holy Cross Church, a 1936 plaque by Prus's nephew

* "Travel Notes (Wieliczka)" [''"Kartki z podróży (Wieliczka),"'' 1878—Prus's impressions of the Wieliczka Salt Mine; these helped inform the conception of the Labyrinth#The Egyptian labyrinth, Egyptian Labyrinth in Prus's 1895 novel, '' Pharaoh''] * "A Word to the Public" (''"Słówko do publiczności,"'' 11 June 1882 — Prus's inaugural address to readers as the new editor-in-chief of the daily, ''Nowiny'' ews famously proposing to make it "an observatory of societal facts, just as there are observatories that study the movements of heavenly bodies, or—climatic changes.") * "Sketch for a Program under the Conditions of the Present Development of Society" (''"Szkic programu w warunkach obecnego rozwoju społeczeństwa,"'' 23–30 March 1883—

* 1968: ''Lalka ( The Doll (1968 film), The Doll''), adapted from the novel '' The Doll'', directed by Wojciech Jerzy Hasbr>

* 1977: '' :pl:Lalka (serial telewizyjny), Lalka'' ( TV serial, ''The Doll''), adapted from the novel '' The Doll'', directed by

Works by Bolesław Prus

at Polish Wikisource * Józef Bachórz

Bolesław Prus

in the Virtual Library of Polish Literature

Bolesław Prus

collected works (Polish) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Prus, Boleslaw 1847 births 1912 deaths People from Hrubieszów People from Lublin Governorate January Uprising participants University of Warsaw alumni 19th-century Polish male writers 20th-century Polish male writers Polish journalists Polish essayists Male essayists 19th-century essayists 20th-century essayists Polish literary critics Polish male short story writers Polish short story writers 19th-century short story writers 20th-century short story writers Polish male novelists 19th-century Polish novelists 20th-century Polish novelists Polish historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in antiquity Burials at Powązki Cemetery 19th-century Polish philosophers 20th-century Polish philosophers Polish positivism

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

, as well as a distinctive voice in world literature.

As a 15-year-old, Aleksander Głowacki joined the Polish 1863 Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed a ...

against Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

. Shortly after his 16th birthday, he suffered severe battle injuries. Five months later, he was imprisoned for his part in the Uprising. These early experiences may have precipitated the panic disorder and agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by symptoms of anxiety in situations where the person perceives their environment to be unsafe with no easy way to escape. These situations can in ...

that dogged him through life, and shaped his opposition to attempting to regain Poland's independence by force of arms.

In 1872, at the age of 25, in Warsaw, he settled into a 40-year journalistic career that highlighted science, technology, education, and economic and cultural development. These societal enterprises were essential to the endurance of a people who had in the 18th century been partitioned out of political existence by Russia, Prussia and Austria. Głowacki took his pen name "''Prus''" from the appellation of his family's coat-of-arms.

As a sideline, he wrote short stories. Succeeding with these, he went on to employ a larger canvas; over the decade between 1884 and 1895, he completed four major novels: ''The Outpost

Outpost may refer to:

Places

* Outpost (military), a detachment of troops stationed at a distance from the main force or formation, usually at a station in a remote or sparsely populated location

* Border outpost, an outpost maintained by a so ...

'', '' The Doll'', ''The New Woman

''The New Woman'' ( pl, Emancypantki) is the third of four major novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. It was composed, and appeared in newspaper serialization, in 1890-93, and dealt with societal questions involving feminism.

History

' ...

'' and '' Pharaoh''. ''The Doll'' depicts the romantic infatuation of a man of action who is frustrated by his country's backwardness. ''Pharaoh'', Prus's only historical novel, is a study of political power and of the fates of nations, set in ancient Egypt at the fall of the 20th Dynasty

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XX, alternatively 20th Dynasty or Dynasty 20) is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties furthermore toget ...

and New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

.

Life

Early years

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in Hrubieszów, now in southeastern Poland, very near the present-day border with Ukraine. The town was then in the Russian-controlled sector of partitioned Poland, known as the " Congress Kingdom". Aleksander was the younger son of Antoni Głowacki, an estate steward at the village of

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in Hrubieszów, now in southeastern Poland, very near the present-day border with Ukraine. The town was then in the Russian-controlled sector of partitioned Poland, known as the " Congress Kingdom". Aleksander was the younger son of Antoni Głowacki, an estate steward at the village of Żabcze

Żabcze is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Dołhobyczów, within Hrubieszów County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland, close to the border with Ukraine. It lies some south of Dołhobyczów, south of Hrubieszów, and south ...

, in Hrubieszów County, and Apolonia Głowacka (née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Trembińska).

In 1850, when the future ''Bolesław Prus'' was three years old, his mother died; the child was placed in the care of his maternal grandmother, Marcjanna Trembińska of Puławy, and, four years later, in the care of his aunt, Domicela Olszewska of Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

. In 1856 Prus was orphaned by his father's death and, aged 9, began attending a Lublin primary school whose principal, Józef Skłodowski, grandfather of the future double Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make out ...

Maria Skłodowska-Curie, administered canings (a customary mode of disciplining) to wayward pupils, including the spirited Aleksander.

In 1862, Prus's brother, Leon, a teacher thirteen years his senior, took him to Siedlce, then to Kielce

Kielce (, yi, קעלץ, Keltz) is a city in southern Poland, and the capital of the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship. In 2021, it had 192,468 inhabitants. The city is in the middle of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains (Holy Cross Mountains), on the bank ...

.

Soon after the outbreak of the Polish January 1863 Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

against Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

, 15-year-old Prus ran away from school to join the insurgents.Pieścikowski, Edward, ''Bolesław Prus'', p. 147. He may have been influenced by his brother Leon, one of the Uprising's leaders. Leon, during a June 1863 mission to Wilno (now Vilnius) in Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

for the Polish insurgent government, developed a debilitating mental illness that would end only with his death in 1907.

On 1 September 1863, twelve days after his sixteenth birthday, Prus took part in a battle against Russian forces at a village called Białka, four kilometers south of Siedlce. He suffered contusions to the neck and gunpowder injuries to his eyes, and was captured unconscious on the battlefield and taken to hospital in Siedlce. This experience may have caused his subsequent lifelong agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by symptoms of anxiety in situations where the person perceives their environment to be unsafe with no easy way to escape. These situations can in ...

.

Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at Lublin Castle for his role in the Uprising. In early April a military court sentenced him to forfeiture of his nobleman's status and resettlement on imperial lands. On 30 April, however, the Lublin District military head credited Prus's time spent under arrest and, on account of the 16-year-old's youth, decided to place him in the custody of his uncle Klemens Olszewski. On 7 May, Prus was released and entered the household of Katarzyna Trembińska, a relative and the mother of his future wife, Oktawia Trembińska.

Prus enrolled at a

Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at Lublin Castle for his role in the Uprising. In early April a military court sentenced him to forfeiture of his nobleman's status and resettlement on imperial lands. On 30 April, however, the Lublin District military head credited Prus's time spent under arrest and, on account of the 16-year-old's youth, decided to place him in the custody of his uncle Klemens Olszewski. On 7 May, Prus was released and entered the household of Katarzyna Trembińska, a relative and the mother of his future wife, Oktawia Trembińska.

Prus enrolled at a Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

'' gymnasium'' (secondary school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' secondary education, lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) ...

), the still functioning prestigious Stanisław Staszic School, founded in 1586. Graduating on 30 June 1866, at nineteen he matriculated in the Warsaw University Department of Mathematics and Physics. In 1868, poverty forced him to break off his university studies.

In 1869, he enrolled in the Forestry Department at the newly opened Agriculture and Forestry Institute in Puławy, a historic town where he had spent some of his childhood and which, 15 years later, was the setting for his striking 1884 micro-story, "Mold of the Earth

"Mold of the Earth" (Polish: "''Pleśń świata''") is one of the shortest micro-stories by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus.

The story was published on 1 January 1884 in the New Year's Day issue of the ''Warsaw Courier'' (''Kurier Warszawski''). ...

", comparing human history

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied throug ...

with the mutual aggressions of blind, mindless colonies of molds that cover a boulder adjacent to the Temple of the Sibyl

The Temple of the Sibyl (in Polish, ''Świątynia Sybilli'') is a colonnaded round monopteral temple-like structure at Puławy, Poland, built at the turn of the 19th century as a museum by Izabela Czartoryska.

History

The "Temple of the Siby ...

. In January 1870, after only three months at the Institute, Prus was expelled for his insufficient deference toward the martinet Russian-language instructor.

Henceforth he studied on his own while supporting himself mainly as a tutor. As part of his program of self-education, he translated and summarized John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

's '' A System of Logic''.

In 1872, he embarked on a career as a newspaper columnist

A columnist is a person who writes for publication in a series, creating an article that usually offers commentary and opinions. Column (newspaper), Columns appear in newspapers, magazines and other publications, including blogs. They take the fo ...

, while working several months at the Evans, Lilpop and Rau Machine and Agricultural Implement Works in Warsaw. In 1873, Prus delivered two public lectures which illustrate the breadth of his scientific interests: "On the Structure of the Universe", and " On Discoveries and Inventions."

Columnist

As a newspaper

As a newspaper columnist

A columnist is a person who writes for publication in a series, creating an article that usually offers commentary and opinions. Column (newspaper), Columns appear in newspapers, magazines and other publications, including blogs. They take the fo ...

, Prus commented on the achievements of scholars and scientists such as John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

, Charles Darwin, Alexander Bain, Herbert Spencer and Henry Thomas Buckle; urged Poles to study science and technology and to develop industry and commerce;Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita, ''Bolesław Prus, 1847–1912: Kalendarz życia i twórczości'' (Bolesław Prus, 1847–1912: A Calendar of His Life and Work), ''passim.'' encouraged the establishment of charitable institutions to benefit the underprivileged; described the fiction and nonfiction works of fellow writers such as H.G. Wells; and extolled man-made and natural wonders such as the Wieliczka Salt Mine, an 1887 solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

that he witnessed at Mława, planned building of the Eiffel Tower for the 1889 Paris Exposition

The Exposition Universelle of 1889 () was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 5 May to 31 October 1889. It was the fourth of eight expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937. It attracted more than thirty-two million visitors. The ...

, and Nałęczów, where he vacationed for 30 years.

His "Weekly Chronicles" spanned forty years (they have since been reprinted in twenty volumes) and helped prepare the ground for the 20th-century blossoming of Polish science and especially mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

. "Our national life," wrote Prus, "will take a normal course only when we have become a useful, indispensable element of civilization, when we have become able to give nothing for free and to demand nothing for free." The social importance of science and technology recurred as a theme in his novels '' The Doll'' (1889) and '' Pharaoh'' (1895).

Of contemporary thinkers, the one who most influenced Prus and other writers of the Polish " Positivist" period (roughly 1864–1900) was Herbert Spencer, the English sociologist who coined the phrase, "survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

." Prus called Spencer "the Aristotle of the 19th century" and wrote: "I grew up under the influence of Spencerian evolutionary philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

and heeded its counsels, not those of Idealist or Comtean philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

." Prus interpreted "survival of the fittest," in the societal sphere, as involving not only competition but also cooperation; and he adopted Spencer's metaphor of society as organism. He used this metaphor to striking effect in his 1884 micro-story "Mold of the Earth

"Mold of the Earth" (Polish: "''Pleśń świata''") is one of the shortest micro-stories by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus.

The story was published on 1 January 1884 in the New Year's Day issue of the ''Warsaw Courier'' (''Kurier Warszawski''). ...

," and in the introduction to his 1895 historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

, '' Pharaoh''.

After Prus began writing regular weekly newspaper columns, his finances stabilized, permitting him on 14 January 1875 to marry a distant cousin on his mother's side, Oktawia Trembińska. She was the daughter of Katarzyna Trembińska, in whose home he had lived, after release from prison, for two years from 1864 to 1866 while completing secondary school. The couple adopted a boy, Emil Trembiński (born 11 September 1886, the son of Prus's brother-in-law Michał Trembiński, who had died on 10 November 1888). Emil was the model for Rascal in chapter 48 of Prus's 1895 novel, '' Pharaoh''. On 18 February 1904, aged seventeen, Emil fatally shot himself in the chest on the doorstep of an unrequited love.

It has been alleged that in 1906, aged 59, Prus had a son, Jan Bogusz Sacewicz. The boy's mother was Alina Sacewicz, widow of Dr. Kazimierz Sacewicz, a socially conscious physician whom Prus had known at Nałęczów. Dr. Sacewicz may have been the model for Stefan Żeromski's Dr. Judym in the novel, ''Ludzie bezdomni'' (Homeless People)—a character resembling Dr. Stockman in Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential playw ...

's play, ''An Enemy of the People

''An Enemy of the People'' (original Norwegian title: ''En folkefiende''), an 1882 play by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, followed his previous play, ''Ghosts'', which criticized the hypocrisy of his society's moral code. That response inclu ...

''. Prus, known for his affection for children, took a lively interest in little Jan, as attested by a prolific correspondence with Jan's mother (whom Prus attempted to interest in writing). Jan Sacewicz became one of Prus's major legatees and an engineer, and died in a German camp after the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising of August–October 1944.

pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

"Prus" ("'' Prus I''" was his family coat-of-arms), reserving his actual name, Aleksander Głowacki, for "serious" writing.

An 1878 incident illustrates the strong feelings that can be aroused in susceptible readers of newspaper columns. Prus had criticized the rowdy behavior of some Warsaw university students at a lecture about the poet Wincenty Pol. The students demanded that Prus retract what he had written. He refused, and, on 26 March 1878, several of them surrounded him outside his home, where he had returned shortly before in the company (for his safety) of two fellow writers; one of the students, Jan Sawicki, slapped Prus's face. Police were summoned, but Prus declined to press charges. Seventeen years later, during his 1895 visit to Paris, Prus's memory of the incident was still so painful that he may have refused (accounts vary) to meet with one of his assailants, Kazimierz Dłuski, and his wife Bronisława Dłuska (Marie Skłodowska Curie

Marie Salomea Skłodowska–Curie ( , , ; born Maria Salomea Skłodowska, ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first ...

's sister who 19 years later, in 1914, scolded Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

for writing his novels and stories in English, rather than in Polish for the benefit of Polish culture). These curiously interlinked incidents involving the Dłuskis and the two authors perhaps illustrate the contemporary intensity of aggrieved Polish national pride.

In 1882, on the recommendation of an earlier editor-in-chief, the prophet of Polish Positivism, Aleksander Świętochowski, Prus succeeded to the editorship of the Warsaw daily ''Nowiny'' (News). The newspaper had been bought in June 1882 by financier Stanisław Kronenberg

Stanisław Leopold Kronenberg (12 December 1846 in Warsaw – 4 April 1894 in Warsaw), was a Polish financier.

Life

He was born the son of banker and railroad tycoon Leopold Stanisław Kronenberg (1812-1878) and his wife Ernestine Rozalia ...

. Prus resolved, in the best Positivist fashion, to make it "an observatory of societal facts"—an instrument for advancing the development of his country. After less than a year, however, ''Nowiny''—which had had a history of financial instability since changing in July 1878 from a Sunday paper to a daily—folded, and Prus resumed writing columns.Pieścikowski, Edward, ''Bolesław Prus'', 152. He continued working as a journalist to the end of his life, well after he had achieved success as an author of short stories and novels.

In an 1884 newspaper column, published two decades before the Wright brothers flew, Prus anticipated that powered flight would not bring humanity closer to universal comity: "Are there among flying creatures only doves, and no hawks? Will tomorrow’s flying machine obey only the honest and the wise, and not fools and knaves?... The expected societal changes may come down to a new form of chase and combat in which the man who is vanquished on high will fall and smash the skull of the peaceable man down below."

In a January 1909 column, Prus discussed H.G. Wells's 1901 book, '' Anticipations'', including Wells's prediction that by the year 2000, following the defeat of German imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

"on land and at sea," there would be a European Union that would reach eastward to include the western Slavs—the Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

, Czechs and Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

. The latter peoples, along with the Hungarians and six other countries, did in fact join the European Union in 2004.

Fiction

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic Hippolyte Taine's concept of the arts, including literature, as a second means, alongside the sciences, of studying reality, and he devoted more attention to his sideline of

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic Hippolyte Taine's concept of the arts, including literature, as a second means, alongside the sciences, of studying reality, and he devoted more attention to his sideline of short-story writer

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest ...

. Prus's stories, which met with great acclaim, owed much to the literary influence of Polish novelist Józef Ignacy Kraszewski and, among English-language writers, to Charles Dickens and Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

. His fiction was also influenced by French writers Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Gustave Flaubert, Alphonse Daudet and Émile Zola.

Prus wrote several dozen stories, originally published in newspapers and ranging in length from micro-story to novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

. Characteristic of them are Prus's keen observation of everyday life and sense of humor, which he had early honed as a contributor to humor magazines. The prevalence of themes from everyday life is consistent with the Polish Positivist artistic program, which sought to portray the circumstances of the populace rather than those of the Romantic heroes of an earlier generation. The literary period in which Prus wrote was ostensibly a prosaic one, by contrast with the poetry of the Romantics; but Prus's prose is often a poetic prose

Prose poetry is poetry written in prose form instead of verse form, while preserving poetic qualities such as heightened imagery, parataxis, and emotional effects.

Characteristics

Prose poetry is written as prose, without the line breaks associat ...

. His stories also often contain elements of fantasy or whimsy. A fair number originally appeared in New Year's issues of newspapers.

Prus long eschewed writing historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

, arguing that it must inevitably distort history. He criticized contemporary historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

ists for their lapses in historical accuracy, including Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz ( , ; 5 May 1846 – 15 November 1916), also known by the pseudonym Litwos (), was a Polish writer, novelist, journalist and Nobel Prize laureate. He is best remembered for his historical novels, especi ...

's failure, in the military scenes in his '' Trilogy'' portraying 17th-century Polish history, to describe the logistics of warfare. It was only in 1888, when Prus was forty, that he wrote his first historical fiction, the stunning short story, "A Legend of Old Egypt

"A Legend of Old Egypt" (Polish: ''"Z legend dawnego Egiptu"'') is a seven-page short story by Bolesław Prus, originally published January 1, 1888, in New Year's supplements to the Warsaw ''Kurier Codzienny'' (Daily Courier) and ''Tygodnik Ilust ...

." This story, a few years later, served as a preliminary sketch for his only historical novel, '' Pharaoh'' (1895).

Eventually Prus composed four novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

s on what he had referred to in an 1884 letter as "great questions of our age": ''The Outpost

Outpost may refer to:

Places

* Outpost (military), a detachment of troops stationed at a distance from the main force or formation, usually at a station in a remote or sparsely populated location

* Border outpost, an outpost maintained by a so ...

'' (''Placówka'', 1886) on the Polish peasant; '' The Doll'' (''Lalka'', 1889) on the aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At t ...

and townspeople and on idealists struggling to bring about social reforms; ''The New Woman

''The New Woman'' ( pl, Emancypantki) is the third of four major novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. It was composed, and appeared in newspaper serialization, in 1890-93, and dealt with societal questions involving feminism.

History

' ...

'' (''Emancypantki'', 1893) on feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

concerns; and his only historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

, '' Pharaoh'' (''Faraon'', 1895), on mechanisms of political power. The work of greatest sweep and most universal appeal is ''Pharaoh''. Prus's novels, like his stories, were originally published in newspaper serialization

In computing, serialization (or serialisation) is the process of translating a data structure or object state into a format that can be stored (e.g. files in secondary storage devices, data buffers in primary storage devices) or transmitted (e ...

.

After having sold ''Pharaoh'' to the publishing firm of Gebethner and Wolff, Prus embarked, on 16 May 1895, on a four-month journey abroad. He visited Berlin, Dresden, Karlsbad, Nuremberg, Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

and Rapperswil. At the latter Swiss town he stayed two months (July–August), nursing his agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by symptoms of anxiety in situations where the person perceives their environment to be unsafe with no easy way to escape. These situations can in ...

and spending much time with his friends, the promising young writer Stefan Żeromski and his wife Oktawia. The couple sought Prus's help for the Polish National Museum "National Museum of Poland" is the common name for several of the country's largest and most notable museums. Poland's National Museum comprises several independent branches, each operating a number of smaller museums. The main branch is the Natio ...

, housed in the Rapperswil Castle, where Żeromski was librarian.

The final stage of Prus's journey took him to Paris, where he was prevented by his agoraphobia from crossing the Seine River to visit the city's southern Left Bank. He was nevertheless pleased to find that his descriptions of Paris in ''The Doll'' had been on the mark (he had based them mainly on French-language publications). From Paris, he hurried home to recuperate at Nałęczów from his journey, the last that he made abroad.

Later years

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

during Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

's 1897 visit to Warsaw. As a rule, Prus did not affiliate himself with political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or pol ...

, as this might compromise his journalistic objectivity. His associations, by design and temperament, were with individuals and select worthy causes rather than with large groups.

The disastrous January 1863 Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

had persuaded Prus that society must advance through learning, work and commerce rather than through risky social upheavals. He departed from this stance, however, in 1905, when Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

experienced defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and Poles demanded autonomy and reforms. On 20 December 1905, in the first issue of a short-lived periodical, ''Młodość'' (Youth), he published an article, "''Oda do młodości''" ("Ode to Youth"), whose title harked back to an 1820 poem by Adam Mickiewicz. Prus wrote, in reference to his earlier position on revolution and strikes: "with the greatest pleasure, I admit it—I was wrong!"

New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

three thousand years earlier, ''Pharaoh'' had also reflected Poland's loss of independence a century before in 1795—an independence whose post- World War I restoration Prus did not live to see.

On 19 May 1912, in his Warsaw apartment at 12 Wolf Street (''ulica Wilcza 12''), near Triple Cross Square, his forty-year journalistic and literary career came to an end when the 64-year-old author died.

The beloved agoraphobic writer was mourned by the nation that he had striven, as soldier, thinker, and writer, to rescue from oblivion. Thousands attended his 22 May 1912 funeral service at St. Alexander's Church on nearby Triple Cross Square (''Plac Trzech Krzyży'') and his interment at Powązki Cemetery.

Prus's tomb was designed by his nephew, the noted sculptor Stanisław Jackowski

Stanisław Jackowski (1887 in Warsaw – 1951 in Katowice) was a Polish sculptor, and nephew of novelist Bolesław Prus. In 1909-11 Jackowski studied sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków (''Akademia Sztuk Pięknych'') under Konstanty L ...

. On three sides it bears, respectively, the novelist's name, ''Aleksander Głowacki'', his years of birth and death, and his pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

, ''Bolesław Prus''. The epitaph on the fourth side, “''Serce Serc''” (“Heart of Hearts”), was deliberately borrowed from the Latin “''Cor Cordium''” on the grave of the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in Rome's Protestant Cemetery. Below the epitaph stands the figure of a little girl embracing the tomb — a figure emblematic of Prus's well-known empathy and affection for children.

Prus's widow, Oktawia Głowacka, survived him by twenty-four years, dying on 25 October 1936.

In 1902 the editor of the Warsaw ''Kurier Codzienny'' (Daily Courier) had opined that, if Prus’s writings had been well known abroad, he should have received one of the recently created Nobel Prizes.

Legacy

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

in eastern Poland. Outside the palace is a sculpture of Prus seated on a bench. Another statuary monument to Prus at Nałęczów, sculpted by Alina Ślesińska, was unveiled on 8 May 1966. It was at Nałęczów that Prus vacationed for thirty years from 1882 until his death, and that he met the young Stefan Żeromski. Prus stood witness at Żeromski's 1892 wedding and generously helped foster the younger man's literary career.

While Prus espoused a positivist and realist outlook, much in his fiction shows qualities compatible with pre- 1863-Uprising Polish Romantic literature

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. Indeed, he held the Polish Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

poet Adam Mickiewicz in high regard. Prus's novels in turn, especially '' The Doll'' and '' Pharaoh'', with their innovative composition techniques, blazed the way for the 20th-century Polish novel.

Prus's novel '' The Doll'', with its rich realistic detail and simple, functional language, was considered by Czesław Miłosz to be the great Polish novel.

Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

, during his 1914 visit to Poland just as World War I was breaking out, "delighted in his beloved Prus" and read everything by the ten-years-older, recently deceased author that he could get his hands on. He pronounced ''The New Woman

''The New Woman'' ( pl, Emancypantki) is the third of four major novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. It was composed, and appeared in newspaper serialization, in 1890-93, and dealt with societal questions involving feminism.

History

' ...

'' (the first novel by Prus that he read) "better than Dickens"—Dickens being a favorite author of Conrad's. Miłosz, however, thought ''The New Woman

''The New Woman'' ( pl, Emancypantki) is the third of four major novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. It was composed, and appeared in newspaper serialization, in 1890-93, and dealt with societal questions involving feminism.

History

' ...

'' "as a whole... an artistic failure..." Zygmunt Szweykowski

Zygmunt Szweykowski (7 April 1894 in Krośniewice – 11 February 1978 in Poznań) was a historian of Polish literature who specialized in 19th-century Polish prose.

Life

In 1932-39, Szweykowski held a professorship at the Free Polish University ( ...

similarly faulted ''The New Womans loose, tangential construction; but this, in his view, was partly redeemed by Prus's humor and by some superb episodes, while "The tragedy of Mrs. Latter and the picture of he town ofIksinów are among the peak achievements of olishnovel-writing."

'' Pharaoh'', a study of political power, became the favorite novel of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, prefigured the fate of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, and continues to point analogies to more recent times. ''Pharaoh'' is often described as Prus's "best-composed novel"—indeed, "one of the best-composed f allPolish novels." This was due in part to ''Pharaoh'' having been composed complete prior to newspaper serialization, rather than being written in installments just before printing, as was the case with Prus's earlier major novels.

''The Doll'' and ''Pharaoh'' are available in English versions. ''The Doll'' has been translated into twenty-eight languages, and ''Pharaoh'' into twenty. In addition, ''The Doll'' has been filmed several times, and been produced as a 1977 television miniseries, ''Pharaoh'' was adapted into a 1966 feature film.

Between 1897 and 1899 Prus serialized in the Warsaw ''Daily Courier'' (''Kurier Codzienny'') a monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monograph ...

on '' The Most General Life Ideals'' (''Najogólniejsze ideały życiowe''), which systematized ethical ideas that he had developed over his career regarding ''happiness'', ''utility'' and ''perfection'' in the lives of individuals and societies. In it he returned to the society-organizing (i.e., political) interests that had been frustrated during his ''Nowiny'' editorship fifteen years earlier. A book edition appeared in 1901 (2nd, revised edition, 1905). This work, rooted in Jeremy Bentham's Utilitarian philosophy and Herbert Spencer's view of society-as-organism, retains interest especially for philosophers and social scientists.

Another of Prus's learned projects remained incomplete at his death. He had sought, over his writing career, to develop a coherent theory of literary composition. Notes of his from 1886 to 1912 were never put together into a finished book as he had intended. His precepts included the maxim, " Nouns, nouns and more nouns." Some particularly intriguing fragments describe Prus's combinatorial calculation

A calculation is a deliberate mathematical process that transforms one or more inputs into one or more outputs or ''results''. The term is used in a variety of senses, from the very definite arithmetical calculation of using an algorithm, to th ...

s of the millions of potential "individual types" of human characters, given a stated number of "individual traits."

A curious comparative-literature aspect has been noted to Prus's career, which paralleled that of his American contemporary, Ambrose Bierce (1842–1914). Each was born and reared in a rural area and had a "Polish" connection (Bierce, born five years before Prus, was reared in Kosciusko County, Indiana, and attended high school at the county seat, Warsaw, Indiana). Each became a war casualty with combat

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

head trauma—Prus in 1863 in the Polish 1863–65 Uprising; Bierce in 1864 in the American Civil War. Each experienced false starts in other occupations, and at twenty-five became a journalist for the next forty years; failed to sustain a career as editor-in-chief; achieved celebrity as a short-story writer; lost a son in tragic circumstances (Prus, an adopted son; Bierce, both his sons); attained superb humorous effects by portraying human egoism (Prus especially in '' Pharaoh'', Bierce in '' The Devil's Dictionary''); was dogged from early adulthood by a health problem (Prus, agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by symptoms of anxiety in situations where the person perceives their environment to be unsafe with no easy way to escape. These situations can in ...

; Bierce, asthma); and died within two years of the other (Prus in 1912; Bierce presumably in 1914). Prus, however, unlike Bierce, went on from short stories to write novels.

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born, Hrubieszów, near the present Polish– Ukrainian border, is graced by an outdoor sculpture of him.

A 1982 plaque on Warsaw University's administration building, the historic Kazimierz Palace, commemorates Prus's years at the University in 1866–68. Across the street ('' Krakowskie Przedmieście'') from the University, in Holy Cross Church, a 1936 plaque by Prus's nephew

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born, Hrubieszów, near the present Polish– Ukrainian border, is graced by an outdoor sculpture of him.

A 1982 plaque on Warsaw University's administration building, the historic Kazimierz Palace, commemorates Prus's years at the University in 1866–68. Across the street ('' Krakowskie Przedmieście'') from the University, in Holy Cross Church, a 1936 plaque by Prus's nephew Stanisław Jackowski

Stanisław Jackowski (1887 in Warsaw – 1951 in Katowice) was a Polish sculptor, and nephew of novelist Bolesław Prus. In 1909-11 Jackowski studied sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków (''Akademia Sztuk Pięknych'') under Konstanty L ...

, featuring Prus's profile, is dedicated to the memory of the "great writer and teacher of the nation."

On the front of Warsaw's present-day ''ulica Wilcza 12'', the site of Prus's last home, is a plaque commemorating the earlier, now-nonexistent building's most famous resident. A few hundred meters from there, ''ulica Bolesława Prusa'' (Bolesław Prus Street) debouches into the southeast corner of Warsaw's Triple Cross Square. In this square stands St. Alexander's Church, where Prus's funeral was held.

In 1937, plaques were installed at Warsaw's '' Krakowskie Przedmieście'' ''4'' and ''7'', where the two chief characters of Prus's novel '' The Doll'', Stanisław Wokulski and Ignacy Rzecki, respectively, were deduced to have resided. On the same street, in a park adjacent to the Hotel Bristol, near the site of a newspaper for which Prus wrote, stands a twice-life-size statue of Prus, sculpted in 1977 by Anna Kamieńska-Łapińska

Anna Kamieńska-Łapińska (Rowiny, Drohiczyn Poleski County, 26 July 1932 – 29 June 2007, Warsaw) was a Polish sculptor and animated-film scenarist.

Life

In 1952–58 she studied in the Sculpture Department of the Warsaw Academy of ...

; it is some 12 feet tall, on a minimal pedestal as befits an author who walked the same ground with his fellow men.

Consonant with Prus's interest in commerce and technology, a Polish Ocean Lines freighter has been named for him.

For 10 years, from 1975 to 1984, Poles honored Prus's memory with a 10- zloty coin featuring his profile. In 2012, to mark the 100th anniversary of his death, the Polish mint produced three coins with individual designs: in gold, silver, and an aluminum-zinc alloy.

Prus's fiction and nonfiction writings continue relevant in our time.Witness articles such as Aleksander Kaczorowski, ''"My z Wokulskiego"'' ("We escendantsof Wokulski) The Doll''">rotagonist of Prus's novel '' The Doll'' in ''Plus Minus'', the '' Rzeczpospolita'' (Republic) Weekly agazine no. 33 (1016), Saturday-Sunday, 18–19 August 2012, pp. P8-P9.

Works

Following is a chronological list of notable works by Bolesław Prus. Translated titles are given, followed by original titles and dates of publication.

Novels

* ''Souls in Bondage'' (''Dusze w niewoli'', written 1876, serialized 1877) * ''Fame'' (''Sława'', begun 1885, never finished) * ''The Outpost

Outpost may refer to:

Places

* Outpost (military), a detachment of troops stationed at a distance from the main force or formation, usually at a station in a remote or sparsely populated location

* Border outpost, an outpost maintained by a so ...

'' (''Placówka'', 1885–86)

* '' The Doll'' (''Lalka'', 1887–89)

* ''The New Woman

''The New Woman'' ( pl, Emancypantki) is the third of four major novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. It was composed, and appeared in newspaper serialization, in 1890-93, and dealt with societal questions involving feminism.

History

' ...

'' (''Emancypantki'', 1890–93)

* '' Pharaoh'' (''Faraon'', written 1894–95; serialized 1895–96; published in book form 1897)

* ''Children'' (''Dzieci'', 1908; approximately the first nine chapters had originally appeared, in a somewhat different form, in 1907 as ''Dawn'' 'Świt''

* ''Changes'' (''Przemiany'', begun 1911–12; unfinished)

Stories

* "Granny's Troubles" (''"Kłopoty babuni,"'' 1874) * "The Palace and the Hovel" (''"Pałac i rudera,"'' 1875) * "The Ball Gown" (''"Sukienka balowa,"'' 1876) * "An Orphan's Lot" (''"Sieroca dola,"'' 1876) * "Eddy's Adventures" (''"Przygody Edzia,"'' 1876) * "Damnable Happiness" (''"Przeklęte szczęście,"'' 1876) * "The Honeymoon" (''"Miesiąc nektarowy"'', 1876) * "In the Struggle with Life" (''"W walce z życiem"'', 1877) * "Christmas Eve" (''"Na gwiazdkę"'', 1877) * "Grandmother's Box" (''"Szkatułka babki,"'' 1878) * "Little Stan's Adventure" (''"Przygoda Stasia,"'' 1879) * "New Year" (''"Nowy rok,"'' 1880) * "The Returning Wave" (''"Powracająca fala,"'' 1880) * "Michałko" (1880) * "Antek" (1880) * "The Convert" (''"Nawrócony,"'' 1880) * " The Barrel Organ" (''"Katarynka,"'' 1880) * "One of Many" (''"Jeden z wielu,"'' 1882) * " The Waistcoat" (''"Kamizelka,"'' 1882) * "Him" (''"On,"'' 1882) * " Fading Voices" (''"Milknące głosy,"'' 1883) * "Sins of Childhood" (''"Grzechy dzieciństwa,"'' 1883) * "Mold of the Earth

"Mold of the Earth" (Polish: "''Pleśń świata''") is one of the shortest micro-stories by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus.

The story was published on 1 January 1884 in the New Year's Day issue of the ''Warsaw Courier'' (''Kurier Warszawski''). ...

" (''"Pleśń świata,"'' 1884: a brilliant micro-story portraying human history

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied throug ...

as an endless series of conflicts among mold colonies inhabiting a common boulder)

* "The Living Telegraph

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in En ...

" (''"Żywy telegraf,"'' 1884)

* " Orestes and Pylades" (''"Orestes i Pylades,"'' 1884)

* "She Loves Me?... She Loves Me Not?..." (''"Kocha—nie kocha?..."'', a micro-story, 1884)

* "The Mirror" (''"Zwierciadło,"'' 1884)

* "On Vacation" (''"Na wakacjach,"'' 1884)

* "An Old Tale" (''"Stara bajka,"'' 1884)

* "In the Light of the Moon" (''"Przy księżycu,"'' 1884)

* "A Mistake" (''"Omyłka,"'' 1884)

* "Mr. Dutkowski and His Farm" (''"Pan Dutkowski i jego folwark,"'' 1884)

* "Musical Echoes" (''"Echa muzyczne,"'' 1884)

* "In the Mountains" (''"W górach,"'' 1885)

* "Shades

Sunglasses or sun glasses (informally called shades or sunnies; more names below) are a form of protective eyewear designed primarily to prevent bright sunlight and high-energy visible light from damaging or discomforting the eyes. They can so ...

" (''"Ciene,"'' 1885: an evocative micro-story on existential themes)

* "Anielka" (1885)

* "A Strange Story" (''"Dziwna historia,"'' 1887)

* "A Legend of Old Egypt

"A Legend of Old Egypt" (Polish: ''"Z legend dawnego Egiptu"'') is a seven-page short story by Bolesław Prus, originally published January 1, 1888, in New Year's supplements to the Warsaw ''Kurier Codzienny'' (Daily Courier) and ''Tygodnik Ilust ...

" (''"Z legend dawnego Egiptu,"'' 1888: Prus's stunning first piece of historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

; a preliminary sketch for his only historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

, '' Pharaoh'', which he wrote in 1894–95)

* "The Dream" (''"Sen,"'' 1890)

* "Lives of Saints" (''"Z żywotów świętych,"'' 1891–92)

* "Reconciled" (''"Pojednani,"'' 1892)

* "A Composition by Little Frank: About Mercy" (''"Z wypracowań małego Frania. O miłosierdziu,"'' 1898)

* "The Doctor's Story" (''"Opowiadanie lekarza,"'' 1902)

* "Memoirs of a Cyclist" (''"Ze wspomnień cyklisty,"'' 1903)

* "Revenge" (''"Zemsta,"'' 1908)

* "Phantoms" (''"Widziadła,"'' 1911, first published 1936)

Nonfiction

* "Letters from the Old Camp" (''"Listy ze starego obozu"''), 1872: Prus's first composition signed with the pseudonym ''Bolesław Prus''. * "On the Structure of the Universe" (''"O budowie wszechświata"''), public lecture, 23 February 1873. * " On Discoveries and Inventions" (''"O odkryciach i wynalazkach"''): A Public Lecture Delivered on 23 March 1873 by Aleksander Głowacki olesław Prus Passed by the ussianCensor (Warsaw, 21 April 1873), Warsaw, Printed by F. Krokoszyńska, 1873* "Travel Notes (Wieliczka)" [''"Kartki z podróży (Wieliczka),"'' 1878—Prus's impressions of the Wieliczka Salt Mine; these helped inform the conception of the Labyrinth#The Egyptian labyrinth, Egyptian Labyrinth in Prus's 1895 novel, '' Pharaoh''] * "A Word to the Public" (''"Słówko do publiczności,"'' 11 June 1882 — Prus's inaugural address to readers as the new editor-in-chief of the daily, ''Nowiny'' ews famously proposing to make it "an observatory of societal facts, just as there are observatories that study the movements of heavenly bodies, or—climatic changes.") * "Sketch for a Program under the Conditions of the Present Development of Society" (''"Szkic programu w warunkach obecnego rozwoju społeczeństwa,"'' 23–30 March 1883—

swan song

The swan song ( grc, κύκνειον ᾆσμα; la, carmen cygni) is a metaphorical phrase for a final gesture, effort, or performance given just before death or retirement. The phrase refers to an ancient belief that swans sing a beautiful so ...

of Prus's editorship of ''Nowiny'')

* "''With Sword and Fire''—Henryk Sienkiewicz's Novel of Olden Times" (''"''Ogniem i mieczem''—powieść z dawnych lat Henryka Sienkiewicza,"'' 1884—Prus's review of Sienkiewicz's historical novel, and essay on historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

s)

* "The Paris Tower" (''"Wieża paryska,"'' 1887—whimsical divagations involving the Eiffel Tower, the world's tallest structure, then yet to be constructed for the 1889 Paris '' Exposition Universelle'')

* "Travels on Earth and in Heaven" (''"Wędrówka po ziemi i niebie,"'' 1887—Prus's impressions of a solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

that he observed at Mława; these helped inspire the solar-eclipse scenes in his 1895 novel, '' Pharaoh'')

* "A Word about Positive Criticism" (''"Słówko o krytyce pozytywnej,"'' 1890—Prus's part of a polemic with Positivist guru Aleksander Świętochowski)

* "Eusapia Palladino" (1893—a newspaper column about mediumistic séances held in Warsaw by the Italian Spiritualist

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century

The ''long nineteenth century'' i ...

, Eusapia Palladino; these helped inspire similar scenes in Prus's 1895 novel, '' Pharaoh'')

* "From Nałęczów" (''"Z Nałęczowa,"'' 1894—Prus's paean to the salubrious waters and natural and social environment of his favorite vacation spot, Nałęczów)

* '' The Most General Life Ideals'' (''Najogólniejsze ideały życiowe'', 1905—Prus's system of pragmatic ethics)

* "Ode to Youth" (''"Oda do młodości,"'' 1905—Prus's admission that, before the Russian Empire's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, he had held too cautious a view of the chances for an improvement in Poland's political situation)

* "Visions of the Future" (''"Wizje przyszłości,"'' 1909—a discussion of H.G. Wells' 1901 futurological book, '' Anticipations'', which predicted, among other things, the defeat of German imperialism, the ascendancy of the English language, and the existence, by the year 2000, of a " European Union" that included the Slavic peoples of Central Europe)

* "The Poet, Educator of the Nation" (''"Poeta wychowawca narodu,"'' 1910—a discussion of the cultural and political principles imparted by the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz)

* "What We... Never Learned from the History of Napoleon" (''"Czego nas... nie nauczyły dzieje Napoleona"''—Prus's contribution to the 16 December 1911 issue of the Warsaw ''Illustrated Weekly'', devoted entirely to Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

)

Translations

Prus's writings have been translated into many languages — hishistorical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

'' Pharaoh'', into twenty; his contemporary novel '' The Doll'', into at least sixteen. Works by Prus have been rendered into Croatian by a member of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Stjepan Musulin

Stjepan Musulin (1885 in Sremska Mitrovica – 1969) was a Croatian linguist, comparative Slavicist, philologist, lexicographer and translator.

Life

Musulin translated from the Polish and Czech languages. He is recognized as one of the gre ...

.

Film versions

* 1966: ''Faraon'' (Pharaoh), adapted from the novel '' Pharaoh'', directed by Jerzy Kawalerowiczbr>* 1968: ''Lalka ( The Doll (1968 film), The Doll''), adapted from the novel '' The Doll'', directed by Wojciech Jerzy Hasbr>

* 1977: '' :pl:Lalka (serial telewizyjny), Lalka'' ( TV serial, ''The Doll''), adapted from the novel '' The Doll'', directed by

Ryszard Ber Ryszard () is the Polish equivalent of "Richard", and may refer to:

*Ryszard Andrzejewski (born 1976), Polish rap musician, songwriter and producer

*Ryszard Bakst (1926–1999), Polish and British pianist and piano teacher of Jewish/Polish/Russian ...

.

* 1979: '' Placówka'' (The Outpost), adapted from the novel ''The Outpost

Outpost may refer to:

Places

* Outpost (military), a detachment of troops stationed at a distance from the main force or formation, usually at a station in a remote or sparsely populated location

* Border outpost, an outpost maintained by a so ...

'', directed by Zygmunt Skonieczny.

* 1982: '' Pensja pani Latter'' (Mrs. Latter's Boarding School), adapted from the novel ''The New Woman

''The New Woman'' ( pl, Emancypantki) is the third of four major novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus. It was composed, and appeared in newspaper serialization, in 1890-93, and dealt with societal questions involving feminism.

History

' ...

'', directed by Stanisław Różewicz.

See also

* Flash fiction * History of philosophy in Poland * List of coupled cousins *List of newspaper columnists

This is a list of notable newspaper columnists. It does not include magazine or electronic columnists.

English-language

Australia

* Phillip Adams (born 1939), ''The Australian''

* Piers Akerman (born 1950), ''The Daily Telegraph''

* Janet A ...

* List of Poles—Philosophy

* List of Poles—Prose literature

* Logology (science of science)—Discoveries and inventions

* Positivism in Poland

* Zakopane

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * Jan Zygmunt Jakubowski, ed., ''Literatura polska od średniowiecza do pozytywizmu'' (Polish Literature from the Middle Ages to Positivism), Warsaw, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1979. * Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' '' Pharaoh'': the Creation of a Historical Novel", '' The Polish Review'', vol. XXXIX, no. 1, 1994, pp. 45–50. * Christopher Kasparek, "Two Micro-stories by Bolesław Prus", '' The Polish Review'', vol. XL, no. 1, 1995, pp. 99–103. * Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' '' Pharaoh'': Primer on Power", '' The Polish Review'', vol. XL, no. 3, 1995, pp. 331–34. * Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' '' Pharaoh'' and the Wieliczka Salt Mine", '' The Polish Review'', vol. XLII, no. 3, 1997, pp. 349–55. * Christopher Kasparek, "Prus' '' Pharaoh'' and the Solar Eclipse", '' The Polish Review'', vol. XLII, no. 4, 1997, pp. 471–78. * Christopher Kasparek, "A Futurological Note: Prus on H.G. Wells and the Year 2000," '' The Polish Review'', vol. XLVIII, no. 1, 2003, pp. 89–100. * * Miłosz, Czesław (1983), ''The History of Polish Literature'', second edition, Berkeley, University of California Press, . * Zdzisław Najder, ''Conrad

Conrad may refer to:

People

* Conrad (name)

Places

United States

* Conrad, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Conrad, Indiana, an unincorporated community

* Conrad, Iowa, a city

* Conrad, Montana, a city

* Conrad Glacier, Washington ...

under Familial Eyes'', Cambridge University Press, 1984, .

* Zdzisław Najder, ''Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

: A Life'', translated by Halina Najder, Rochester, Camden House, 2007, .

*

* Monika Piątkowska, ''Prus: Śledztwo biograficzne'' (Prus: A Biographical Investigation), Kraków, Wydawnictwo Znak

Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy „Znak” (English, "Znak Social Publishing Institute") is one of the largest Polish book publishing companies.Herbert R. LottmanPW: Publishing in Poland ''Publishers Weekly'', publishersweekly.com, 1 May 1998. Retr ...

, 2017, .

*

* Bolesław Prus, '' On Discoveries and Inventions: A Public Lecture Delivered on 23 March 1873 by Aleksander Głowacki olesław Prus', Passed by the ussianCensor (Warsaw, 21 April 1873), Warsaw, Printed by F. Krokoszyńska, 1873.

* (This book contains twelve stories by Prus, including the volume's title story, in inaccurate, clunky translations.)

*

*

* Robert Reid, ''Marie Curie'', New York, New American Library, 1974.

*

*

*

* Tokarzówna, Krystyna (1981), ''Młodość Bolesława Prusa'' (Bolesław Prus's Youth), Warsaw, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, .

*

*

External links

Works by Bolesław Prus

at Polish Wikisource * Józef Bachórz

Bolesław Prus

in the Virtual Library of Polish Literature

Bolesław Prus

collected works (Polish) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Prus, Boleslaw 1847 births 1912 deaths People from Hrubieszów People from Lublin Governorate January Uprising participants University of Warsaw alumni 19th-century Polish male writers 20th-century Polish male writers Polish journalists Polish essayists Male essayists 19th-century essayists 20th-century essayists Polish literary critics Polish male short story writers Polish short story writers 19th-century short story writers 20th-century short story writers Polish male novelists 19th-century Polish novelists 20th-century Polish novelists Polish historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in antiquity Burials at Powązki Cemetery 19th-century Polish philosophers 20th-century Polish philosophers Polish positivism