Biscayne National Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Biscayne National Park is an American

Biscayne National Park comprises in

Biscayne National Park comprises in

Biscayne Bay marks the southernmost extent of the Atlantic barrier islands, represented by Key Biscayne, and the northernmost extent of the Florida Keys at Elliott Key. The keys are distinguished from the barrier islands by the coral limestone that extends to the islands' surface under a thin veneer of topsoil, while the barrier islands are dominated by wave-deposited sands that cover most of the limestones.Bryan ''et al.'', p. 288 Biscayne Bay lies between low ridges of oolitic Miami Limestone on the west, forming Cutler Ridge, and the coral-based Key Largo Limestone that underlies Elliott Key and the keys to the south. The Miami Limestone was deposited in turbulent lagoon waters. The Key Largo Limestone is a fossilized coral reef formed during the

Biscayne Bay marks the southernmost extent of the Atlantic barrier islands, represented by Key Biscayne, and the northernmost extent of the Florida Keys at Elliott Key. The keys are distinguished from the barrier islands by the coral limestone that extends to the islands' surface under a thin veneer of topsoil, while the barrier islands are dominated by wave-deposited sands that cover most of the limestones.Bryan ''et al.'', p. 288 Biscayne Bay lies between low ridges of oolitic Miami Limestone on the west, forming Cutler Ridge, and the coral-based Key Largo Limestone that underlies Elliott Key and the keys to the south. The Miami Limestone was deposited in turbulent lagoon waters. The Key Largo Limestone is a fossilized coral reef formed during the

Native Americans were present in lower Florida 10,000 years ago, when ocean levels were low and Biscayne Bay was comparatively empty of water. Water levels rose from about 4000 years ago and inundated the bay. Archeologists believe any traces left by the peoples of that era are now submerged; none now exist on dry lands in the park. The

Native Americans were present in lower Florida 10,000 years ago, when ocean levels were low and Biscayne Bay was comparatively empty of water. Water levels rose from about 4000 years ago and inundated the bay. Archeologists believe any traces left by the peoples of that era are now submerged; none now exist on dry lands in the park. The

As modern communities grew in and around Miami, developers looked to southern Dade County for new projects. The undeveloped keys south of Key Biscayne were viewed as prime development territory. Beginning in the 1890s local interests promoted the construction of a causeway to the mainland. One proposal included building a highway linking the Biscayne Bay keys to the

As modern communities grew in and around Miami, developers looked to southern Dade County for new projects. The undeveloped keys south of Key Biscayne were viewed as prime development territory. Beginning in the 1890s local interests promoted the construction of a causeway to the mainland. One proposal included building a highway linking the Biscayne Bay keys to the  The oil-fired Turkey Point power stations were completed in 1967–68 and experienced immediate problems from the discharge of hot cooling water into Biscayne Bay, where the heat killed marine grasses. In 1964 FP&L announced plans for two 693 MW nuclear reactors at the site, which were expected to compound the cooling water problem. Because of the shallowness of Biscayne Bay, the power stations were projected to consume a significant proportion of the bay's waters each day for cooling. After extensive negotiations and litigation with both the state and with Ludwig, who owned lands needed for cooling water canals, a closed-loop canal system was built south of the power plants and the nuclear units became operational in the early 1970s.

Portions of the present park were used for recreation prior to the park's establishment. Homestead Bayfront Park, still operated by Miami-Dade County just south of Convoy Point, established a "blacks-only" segregated beach for African-Americans at the present site of the Dante Fascell Visitor Center. The segregated beach operated through the 1950s into the early 1960s before segregated public facilities were abolished.

The oil-fired Turkey Point power stations were completed in 1967–68 and experienced immediate problems from the discharge of hot cooling water into Biscayne Bay, where the heat killed marine grasses. In 1964 FP&L announced plans for two 693 MW nuclear reactors at the site, which were expected to compound the cooling water problem. Because of the shallowness of Biscayne Bay, the power stations were projected to consume a significant proportion of the bay's waters each day for cooling. After extensive negotiations and litigation with both the state and with Ludwig, who owned lands needed for cooling water canals, a closed-loop canal system was built south of the power plants and the nuclear units became operational in the early 1970s.

Portions of the present park were used for recreation prior to the park's establishment. Homestead Bayfront Park, still operated by Miami-Dade County just south of Convoy Point, established a "blacks-only" segregated beach for African-Americans at the present site of the Dante Fascell Visitor Center. The segregated beach operated through the 1950s into the early 1960s before segregated public facilities were abolished.

The earliest proposals for the protection of Biscayne Bay were part of proposals by Everglades National Park advocate Ernest F. Coe, whose proposed Everglades park boundaries included Biscayne Bay, its keys, interior country including what are now Homestead and

The earliest proposals for the protection of Biscayne Bay were part of proposals by Everglades National Park advocate Ernest F. Coe, whose proposed Everglades park boundaries included Biscayne Bay, its keys, interior country including what are now Homestead and  The park's popularity as a destination for boaters has led to a high rate of accidents, some of them fatal. The

The park's popularity as a destination for boaters has led to a high rate of accidents, some of them fatal. The

Biscayne National Park operates year-round. Camping is most practical in winter months, when mosquitoes are less troublesome on the keys. The Biscayne National Park Institute provides half and full day tours in the park that include snorkeling, hiking, paddling and sailing from the park headquarters. Boat excursions to Boca Chita Key and the area's lighthouses are also available. Licensed private concessionaires provide guided fishing, snorkeling, sailing, and sightseeing tours.

Biscayne National Park operates year-round. Camping is most practical in winter months, when mosquitoes are less troublesome on the keys. The Biscayne National Park Institute provides half and full day tours in the park that include snorkeling, hiking, paddling and sailing from the park headquarters. Boat excursions to Boca Chita Key and the area's lighthouses are also available. Licensed private concessionaires provide guided fishing, snorkeling, sailing, and sightseeing tours.

Although most of Biscayne National Park's area is water, the islands have a number of protected historical structures and districts. Shipwrecks are also protected within the park, and the park's offshore waters are a protected historic district.

Although most of Biscayne National Park's area is water, the islands have a number of protected historical structures and districts. Shipwrecks are also protected within the park, and the park's offshore waters are a protected historic district.

Stiltsville was established by Eddie "Crawfish" Walker in the 1930s as a small community of shacks built on pilings in a shallow section of Biscayne Bay, not far from Key Biscayne. Comprising 27 structures at its height in the 1960s, Stiltsville lost shacks to fires and hurricanes, with only seven surviving in 2012, none of them dating to the 1960s or earlier. The site was incorporated into Biscayne National Park in 1985, when the Park Service agreed to honor existing leases until July 1, 1999. Hurricane Andrew destroyed most of Stiltsville in 1992. The Park Service has undertaken to preserve the community, which is now unoccupied. The community is to be administered by a trust and used as accommodation for overnight camping, educational facilities and researchers.

Stiltsville was established by Eddie "Crawfish" Walker in the 1930s as a small community of shacks built on pilings in a shallow section of Biscayne Bay, not far from Key Biscayne. Comprising 27 structures at its height in the 1960s, Stiltsville lost shacks to fires and hurricanes, with only seven surviving in 2012, none of them dating to the 1960s or earlier. The site was incorporated into Biscayne National Park in 1985, when the Park Service agreed to honor existing leases until July 1, 1999. Hurricane Andrew destroyed most of Stiltsville in 1992. The Park Service has undertaken to preserve the community, which is now unoccupied. The community is to be administered by a trust and used as accommodation for overnight camping, educational facilities and researchers.

national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

located south of Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County is a county located in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Florida. The county had a population of 2,701,767 as of the 2020 census, making it the most populous county in Florida and the seventh-most populous county in ...

. The park preserves Biscayne Bay

Biscayne Bay () is a lagoon with characteristics of an estuary located on the Atlantic coast of South Florida. The northern end of the lagoon is surrounded by the densely developed heart of the Miami metropolitan area while the southern end is la ...

and its offshore barrier reefs. Ninety-five percent of the park is water, and the shore of the bay is the location of an extensive mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evoluti ...

forest. The park covers and includes Elliott Key

Elliott Key is the northernmost of the true Florida Keys (those 'keys' which are ancient coral reefs lifted above the present sea level), and the largest key north of Key Largo. It is located entirely within Biscayne National Park, in Miami-Dade ...

, the park's largest island and northernmost of the true Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral cay archipelago located off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami, and e ...

, formed from fossilized coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and sec ...

reef. The islands farther north in the park are transitional islands of coral and sand. The offshore portion of the park includes the northernmost region of the Florida Reef

The Florida Reef (also known as the Great Florida Reef, Florida reefs, Florida Reef Tract and Florida Keys Reef Tract) is the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States. It is the third largest coral barrier reef system in ...

, one of the largest coral reefs in the world.

Biscayne National Park protects four distinct ecosystems: the shoreline mangrove swamp

Mangrove forests, also called mangrove swamps, mangrove thickets or mangals, are productive wetlands that occur in coastal intertidal zones. Mangrove forests grow mainly at tropical and subtropical latitudes because mangroves cannot withstand fre ...

, the shallow waters of Biscayne Bay, the coral limestone keys and the offshore Florida Reef. The shoreline swamps of the mainland and island margins provide a nursery for larval and juvenile fish, molluscs and crustaceans. The bay waters harbor immature and adult fish, seagrass beds, sponges, soft corals, and manatees

Manatees (family Trichechidae, genus ''Trichechus'') are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing three of the four living species ...

. The keys are covered with tropical vegetation including endangered cacti and palms, and their beaches provide nesting grounds for endangered sea turtles

Worldwide, hundreds of thousands of sea turtles a year are accidentally caught in shrimp trawl nets, on longline hooks and in fishing gill-nets. Sea turtles need to reach the surface to breathe, and therefore many drown once caught. Loggerhead an ...

. Offshore reefs and waters harbor more than 200 species of fish, pelagic birds, whales and hard corals. Sixteen endangered species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inv ...

including Schaus' swallowtail butterflies, smalltooth sawfish

The smalltooth sawfish (''Pristis pectinata'') is a species of sawfish in the family Pristidae. It is found in shallow tropical and subtropical waters in coastal and estuarine parts of the Atlantic. Reports from elsewhere are now believed to be m ...

, manatees, and green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 Nanometre, nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by ...

and hawksbill

The hawksbill sea turtle (''Eretmochelys imbricata'') is a critically endangered sea turtle belonging to the family Cheloniidae. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Eretmochelys''. The species has a global distribution, that is large ...

sea turtles may be observed in the park. Biscayne also has a small population of threatened American crocodile

The American crocodile (''Crocodylus acutus'') is a species of crocodilian found in the Neotropics. It is the most widespread of the four extant species of crocodiles from the Americas, with populations present from South Florida and the coasts ...

s and a few American alligator

The American alligator (''Alligator mississippiensis''), sometimes referred to colloquially as a gator or common alligator, is a large crocodilian reptile native to the Southeastern United States. It is one of the two extant species in the g ...

s.

The people of the Glades culture

The Glades culture is an archaeological culture in southernmost Florida that lasted from about 500 BCE until shortly after European contact. Its area included the Everglades, the Florida Keys, the Atlantic coast of Florida north through present-day ...

inhabited the Biscayne Bay region as early as 10,000 years ago before rising sea levels filled the bay. The Tequesta

The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans a ...

people occupied the islands and shoreline from about 4,000 years before the present to the 16th century, when the Spanish took possession of Florida. Reefs claimed ships from Spanish times through the 20th century, with more than 40 documented wrecks within the park's boundaries. While the park's islands were farmed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, their rocky soil and periodic hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

s made agriculture difficult to sustain.

In the early 20th century the islands became secluded destinations for wealthy Miamians who built getaway homes and social clubs. Mark C. Honeywell's guesthouse on Boca Chita Key

Boca Chita Key is the island north of the upper Florida Keys in Biscayne National Park, Miami-Dade County, Florida.

The key is located in Biscayne Bay, just north of Sands Key. An ornamental lighthouse is present on the key.Cocolobo Cay Club

The Cocolobo Cay Club, later known as the Coco Lobo Club, was a private club on Adams Key in what is now Biscayne National Park, Florida. It was notable as a destination for the rich and the politically well-connected. Four presidents ( Warren G ...

was at various times owned by Miami developer Carl G. Fisher

Carl Graham Fisher (January 12, 1874 – July 15, 1939) was an American entrepreneur. He was an important figure in the automotive industry, in highway construction, and in real estate development.

In his early life in Indiana, despite fa ...

, yachtsman Garfield Wood

Garfield Arthur "Gar" Wood (December 4, 1880 – June 19, 1971) was an American inventor, entrepreneur, and championship motorboat builder and racer who held the world water speed record on several occasions. He was the first man to travel ...

, and President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's friend Bebe Rebozo

Charles Gregory "Bebe" (pronounced ) Rebozo (November 17, 1912 – May 8, 1998) was an American Florida-based banker and businessman who was a friend and confidant of President Richard Nixon.

Early life

The youngest of 12 children (he ...

, and was visited by four United States presidents. The amphibious community of Stiltsville, established in the 1930s in the shoals of northern Biscayne Bay, took advantage of its remoteness from land to offer offshore gambling and alcohol during Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

. After the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in cou ...

of 1959, the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

and Cuban exile groups used Elliott Key as a training ground for infiltrators into Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

's Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

.

Originally proposed for inclusion in Everglades National Park

Everglades National Park is an American national park that protects the southern twenty percent of the original Everglades in Florida. The park is the largest tropical wilderness in the United States and the largest wilderness of any kind east ...

, Biscayne Bay was removed from the proposed park to ensure Everglades' establishment. The area remained undeveloped until the 1960s, when a series of proposals were made to develop the keys in the manner of Miami Beach

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It was incorporated on March 26, 1915. The municipality is located on natural and man-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay, the latter of which sep ...

, and to construct a deepwater seaport for bulk cargo, along with refinery and petrochemical facilities on the mainland shore of Biscayne Bay. Through the 1960s and 1970s, two fossil-fueled power plants and two nuclear power plants were built on the bay shores. A backlash against development led to the 1968 designation of Biscayne National Monument. The preserved area was expanded by its 1980 re-designation as Biscayne National Park. The park is heavily used by boaters, and apart from the park's visitor center on the mainland and a jetty at Black Point Marina, its land and sea areas are accessible only by boat.

Geography

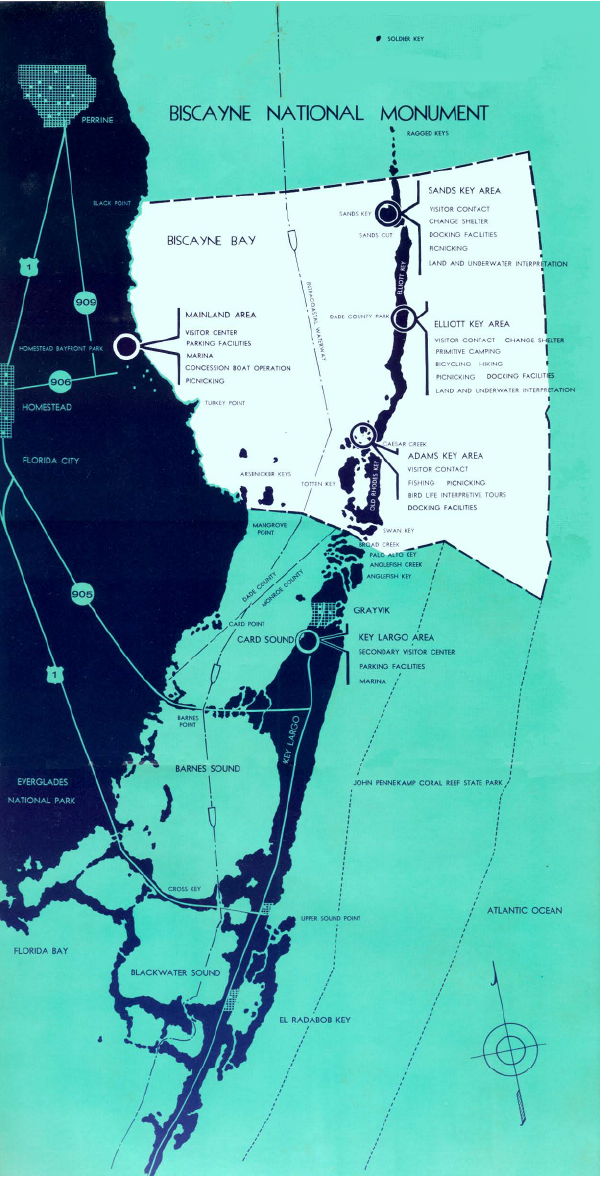

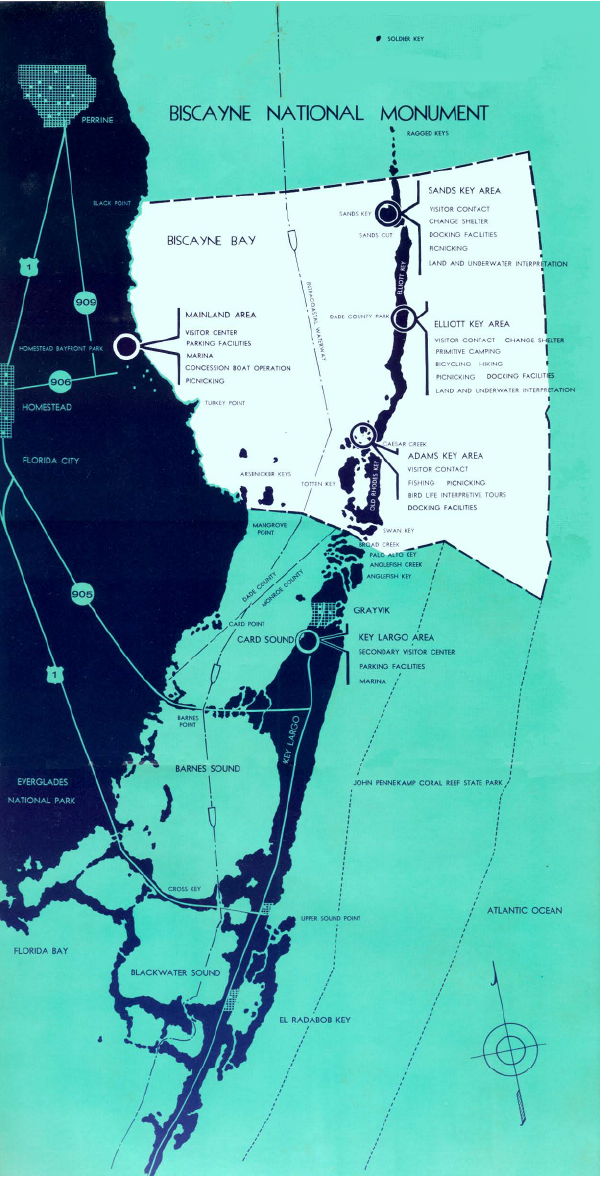

Biscayne National Park comprises in

Biscayne National Park comprises in Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County is a county located in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Florida. The county had a population of 2,701,767 as of the 2020 census, making it the most populous county in Florida and the seventh-most populous county in ...

in southeast Florida. Extending from just south of Key Biscayne

Key Biscayne ( es, Cayo Vizcaíno, link=no) is an island located in Miami-Dade County, Florida, located between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay. It is the southernmost of the barrier islands along the Atlantic coast of Florida, and lies sout ...

southward to just north of Key Largo

Key Largo ( es, Cayo Largo) is an island in the upper Florida Keys archipelago and is the largest section of the keys, at long. It is one of the northernmost of the Florida Keys in Monroe County, and the northernmost of the keys connected b ...

, the park includes Soldier Key

Soldier Key is an island in Biscayne National Park in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It is located between Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, about three miles north of the Ragged Keys, five miles south of Cape Florida on Key Biscayne, seven-an ...

, the Ragged Keys

Ragged Keys are small islands north of the upper Florida Keys.

They are located in Biscayne Bay, just north of Sands Key, and are part of Biscayne National Park

Biscayne National Park is an American national park located south of Miami, ...

, Sands Key

Sands Key is an island north of the upper Florida Keys in Biscayne National Park. It is in Miami-Dade County, Florida.

It is located in lower Biscayne Bay, between Elliott Key and Boca Chita Key.

History

Earlier names for the island were "Las ...

, Elliott Key

Elliott Key is the northernmost of the true Florida Keys (those 'keys' which are ancient coral reefs lifted above the present sea level), and the largest key north of Key Largo. It is located entirely within Biscayne National Park, in Miami-Dade ...

, Totten Key

Totten Key is an island of the upper Florida Keys in Biscayne National Park. It is in Miami-Dade County, Florida.

It is located in southern Biscayne Bay, just west of Old Rhodes Key.

History

It was probably named for General Joseph Totten who ...

and Old Rhodes Key

Old Rhodes Key is an island north of the upper Florida Keys in Biscayne National Park. It is in Miami-Dade County, Florida.

It is located just north of Broad Creek in the lower part of Biscayne Bay

Biscayne Bay () is a lagoon with characte ...

, as well as smaller islands that form the northernmost extension of the Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral cay archipelago located off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami, and e ...

. The Safety Valve

A safety valve is a valve that acts as a fail-safe. An example of safety valve is a pressure relief valve (PRV), which automatically releases a substance from a boiler, pressure vessel, or other system, when the pressure or temperature exceeds ...

, a wide shallow opening in the island chain, between the Ragged Keys and Key Biscayne just north of the park's boundary, allows storm surge

A storm surge, storm flood, tidal surge, or storm tide is a coastal flood or tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water commonly associated with low-pressure weather systems, such as cyclones. It is measured as the rise in water level above the n ...

water to flow out of the bay after the passage of tropical storms. The park's eastern boundary is the ten-fathom line () of water depth in the Atlantic Ocean on the Florida Reef

The Florida Reef (also known as the Great Florida Reef, Florida reefs, Florida Reef Tract and Florida Keys Reef Tract) is the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States. It is the third largest coral barrier reef system in ...

. The park's western boundary is a fringe of property on the mainland, extending a few hundred meters inland between Cutler Ridge

Cutler Bay is an incorporated town in Miami-Dade County, Florida established in 2005, with a population of approximately 45,425 as of 2020. With 45,425 people, Cutler Bay is in 9th place of the top 10 most populous municipalities of the 34 m ...

and Mangrove Point. The only direct mainland access to the park is at the Convoy Point Visitor Center, adjacent to the park headquarters. The southwestern boundary adjoins the Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station

Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station is a nuclear and gas-fired power plant located on a site two miles east of Homestead, Florida, United States, next to Biscayne National Park located about south of Miami, Florida near the southernmo ...

and its system of cooling canals.

The southern portion of Biscayne Bay

Biscayne Bay () is a lagoon with characteristics of an estuary located on the Atlantic coast of South Florida. The northern end of the lagoon is surrounded by the densely developed heart of the Miami metropolitan area while the southern end is la ...

extends between Elliott Key and the mainland, transited by the Intracoastal Waterway

The Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) is a inland waterway along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts of the United States, running from Massachusetts southward along the Atlantic Seaboard and around the southern tip of Florida, then following th ...

. The park abuts the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary is a U.S. National Marine Sanctuary in the Florida Keys. It includes the Florida Reef, the only barrier coral reef in North America and the third-largest coral barrier reef in the world. It also has ex ...

on the east and south sides of the park and John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park

John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park is a Florida State Park located on Key Largo in Florida. It includes approximately 70 nautical square miles (240 km²) of adjacent Atlantic Ocean waters. The park is approximately 25 miles in length a ...

to the south. Only of the park's area are on land, with the offshore keys comprising and mainland mangrove swamps account for the remaining . As an extension of the Everglades ecosystem, much of the park was originally proposed to be included in Everglades National Park

Everglades National Park is an American national park that protects the southern twenty percent of the original Everglades in Florida. The park is the largest tropical wilderness in the United States and the largest wilderness of any kind east ...

, but was excluded to obtain a consensus for the establishment of the Everglades park in 1947.Grunwald, p. 214

Geology

Biscayne Bay marks the southernmost extent of the Atlantic barrier islands, represented by Key Biscayne, and the northernmost extent of the Florida Keys at Elliott Key. The keys are distinguished from the barrier islands by the coral limestone that extends to the islands' surface under a thin veneer of topsoil, while the barrier islands are dominated by wave-deposited sands that cover most of the limestones.Bryan ''et al.'', p. 288 Biscayne Bay lies between low ridges of oolitic Miami Limestone on the west, forming Cutler Ridge, and the coral-based Key Largo Limestone that underlies Elliott Key and the keys to the south. The Miami Limestone was deposited in turbulent lagoon waters. The Key Largo Limestone is a fossilized coral reef formed during the

Biscayne Bay marks the southernmost extent of the Atlantic barrier islands, represented by Key Biscayne, and the northernmost extent of the Florida Keys at Elliott Key. The keys are distinguished from the barrier islands by the coral limestone that extends to the islands' surface under a thin veneer of topsoil, while the barrier islands are dominated by wave-deposited sands that cover most of the limestones.Bryan ''et al.'', p. 288 Biscayne Bay lies between low ridges of oolitic Miami Limestone on the west, forming Cutler Ridge, and the coral-based Key Largo Limestone that underlies Elliott Key and the keys to the south. The Miami Limestone was deposited in turbulent lagoon waters. The Key Largo Limestone is a fossilized coral reef formed during the Sangamonian

The Sangamonian Stage (or Sangamon interglacial) is the term used in North America to designate the last interglacial period. In its most common usage, it is used for the period of time between 75,000 and 125,000 BP.Willman, H.B., and J.C. Frye, 1 ...

Stage of about 75,000 to 125,000 years ago. The Miami Formation achieved its present form somewhat later, during a glacial period in which fresh water consolidated and cemented the lagoon deposits. The Key Largo Limestone is a coarse stone formed from stony corals, between in thickness. As a consequence of their origins as reefs, the beaches of Elliott Key and Old Rhodes Key are rocky. Significant sandy beaches are found only at Sands Key.

Hydrology

Biscayne Bay is a shallow semi-enclosed lagoon which averages in depth. Both its mainland margins and the keys are covered by mangrove forest. The park includes the southern portion of Biscayne Bay, with areas of thin sediment called "hardbottom", and vegetatedseagrass meadow

A seagrass meadow or seagrass bed is an underwater ecosystem formed by seagrasses. Seagrasses are marine (saltwater) plants found in shallow coastal waters and in the brackish waters of estuaries. Seagrasses are flowering plants with stems and ...

s supporting turtlegrass and shoal grass.

As a result of efforts to control water resources in Florida and projects to drain the Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of tropical climate, tropical wetlands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orland ...

during the early and mid-20th century, water flow into Biscayne Bay has been altered by the construction of canals. These canals channel water from portions of the southeastern Everglades now used for agriculture into the bay. Prior to canal construction, most fresh water inflow came from rain and groundwater, but the canals are now altering the salinity profile of the bay, conveying sediment and pollutants and leading to saltwater intrusion

Saltwater intrusion is the movement of saline water into freshwater aquifers, which can lead to groundwater quality degradation, including drinking water sources, and other consequences. Saltwater intrusion can naturally occur in coastal aquifers ...

into the Biscayne aquifer. The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) is the plan enacted by the U.S. Congress for the restoration of the Everglades ecosystem in southern Florida.

When originally authorized by the U.S. Congress in 2000, it was estimated that CERP ...

(CERP) was established in 2000 to mitigate the effects of human intervention into the natural water flow of the Everglades. Primarily aimed at the restoration of historical patterns of water flow into Everglades National Park, the project will also deal with issues arising from the diversion of water out of the southern Everglades into Biscayne Bay.NPCA, p. 2 The Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands Project (BBCW) is a CERP component specifically intended to redistribute water flow so that fresh water is introduced gradually through creeks and marshes rather than short, heavy discharges through drainage canals.NPCA, p. 13

Human history

Native people

Native Americans were present in lower Florida 10,000 years ago, when ocean levels were low and Biscayne Bay was comparatively empty of water. Water levels rose from about 4000 years ago and inundated the bay. Archeologists believe any traces left by the peoples of that era are now submerged; none now exist on dry lands in the park. The

Native Americans were present in lower Florida 10,000 years ago, when ocean levels were low and Biscayne Bay was comparatively empty of water. Water levels rose from about 4000 years ago and inundated the bay. Archeologists believe any traces left by the peoples of that era are now submerged; none now exist on dry lands in the park. The Cutler Fossil Site

The Cutler Fossil Site ( 8DA2001) is a sinkhole near Biscayne Bay in Palmetto Bay, Florida, which is south of Miami. The site has yielded bones of Pleistocene animals and bones as well as artifacts of Paleo-Indians and people of the Archaic perio ...

, just to the west of the park, has yielded evidence of human occupation extending to at least 10000 years before the present.Leynes, Cullison, Chapter 2, pp. 9–10 The earliest evidence of human presence in Biscayne dates to about 2500 years before the present, with piles of conch

Conch () is a common name of a number of different medium-to-large-sized sea snails. Conch shells typically have a high spire and a noticeable siphonal canal (in other words, the shell comes to a noticeable point at both ends).

In North Am ...

and whelk

Whelk (also known as scungilli) is a common name applied to various kinds of sea snail. Although a number of whelks are relatively large and are in the family Buccinidae (the true whelks), the word ''whelk'' is also applied to some other marine ...

shells left by the Glades culture

The Glades culture is an archaeological culture in southernmost Florida that lasted from about 500 BCE until shortly after European contact. Its area included the Everglades, the Florida Keys, the Atlantic coast of Florida north through present-day ...

. The Glades culture was followed by the Tequesta

The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans a ...

people, who occupied the shores of Biscayne Bay. The Tequesta were a sedentary community that lived on fish and other sea life, with no significant agricultural activity. A site on Sands Key has yielded potsherds, worked shells and other artifacts indicating occupation from at latest 1000 AD to about 1650, after contact was made with Europeans. Fifty significant archaeological sites have been identified in the park.NPCA, p. 33

Exploration

Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León (, , , ; 1474 – July 1521) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' known for leading the first official European expedition to Florida and for serving as the first governor of Puerto Rico. He was born in Santervá ...

explored the area in 1513, discovering the Florida Keys and encountering the Tequesta on the mainland. Other Spanish explorers arrived later in the 16th century and Florida came under Spanish rule. The Tequesta were resettled by the then-Spanish government in the Florida Keys, and the South Florida mainland was depopulated. Ponce de León referred to the bay as "Chequescha" after its inhabitants, becoming "Tequesta" by the time of Spanish governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (; ast, Pedro (Menéndez) d'Avilés; 15 February 1519 – 17 September 1574) was a Spanish admiral, explorer and conquistador from Avilés, in Asturias, Spain. He is notable for planning the first regular trans-oceani ...

later in the century. The present name has been attributed to a shipwrecked Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

sailor known as the " Biscaino" or "Viscayno" who lived in the area for a time, or to a more general allusion to the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

.

Spanish treasure fleets regularly sailed past the Florida Keys and were often caught in hurricanes. There are 44 documented shipwrecks in the park from the 16th through the 20th centuries. At least two 18th-century Spanish ships were wrecked in the park area.Miller, p. 6 The Spanish galleon ''Nuestra Senora del Popolo'' is believed to have been wrecked in park waters in 1733, though the site has not been found. HMS ''Fowey'' was wrecked in 1748NPCA, p. 32 in what is now Legare Anchorage, at some distance from the Fowey Rocks. The discovery of the ship in 1975 resulted in a landmark court case that established the wreck as an archaeological site rather than a salvage site. 43 wrecks are included on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in the Offshore Reefs Archeological District, which extends for along the seaward side of the Biscayne National Park keys. During the 18th century, Elliott Key was the reputed base of two different pirates, both called Black Caesar, commemorated by Caesar's Creek between Elliott and Old Rhodes Key.

Settlement and pre-park use

The first permanent European settlers in the Miami area did not come until the early 19th century. The first settlements around Biscayne Bay were small farms on Elliott Key growing crops likekey lime

The Key lime or acid lime (''Citrus'' × ''aurantiifolia'' or ''C. aurantifolia'') is a citrus hybrid ('' C. hystrix'' × '' C. medica'') native to tropical Southeast Asia. It has a spherical fruit, in diameter. The Key lime is usually picked ...

s and pineapple

The pineapple (''Ananas comosus'') is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae. The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centuri ...

s. John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin; April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was an American self-trained artist, naturalist, and ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornithology turned into a plan to make a complete pictoria ...

visited Elliott Key in 1832. Colonel Robert E. Lee surveyed the area around Biscayne Bay for potential fortification sites in 1849. At the end of the American Civil War in 1865, a number of Confederates passed through the area as they were attempting to escape to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. Elliott Key was a brief stopping point for John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

during his flight to Cuba. The former United States vice president, Confederate general and Confederate secretary of war spent two nights in Biscayne Bay on his journey. Few people lived in the park area until 1897, when Israel Lafayette Jones, an African-American property manager, bought Porgy Key for $300 US. The next year Jones bought the adjoining Old Rhodes Key and moved his family there, clearing land to grow limes and pineapples. In 1911 Jones bought Totten Key, which had been used as a pineapple plantation, for a dollar an acre, selling in 1925 for $250,000.Shumaker, p. 53 Before Israel Jones' death in 1932 the Jones plantations were for a while among the largest lime producers on the Florida east coast.

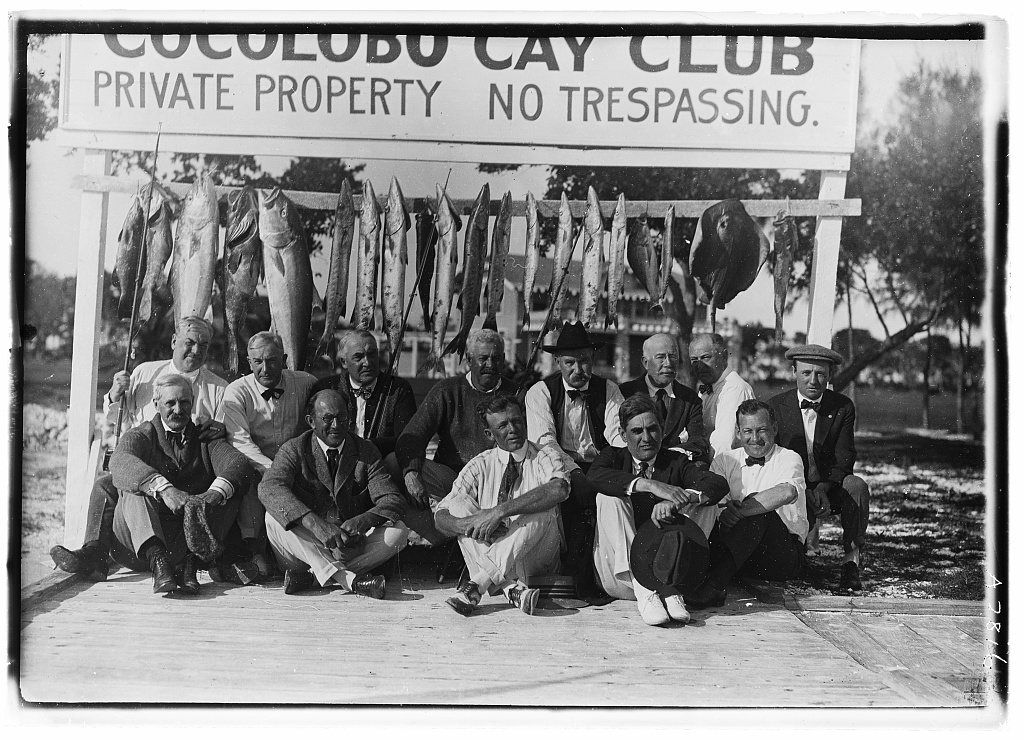

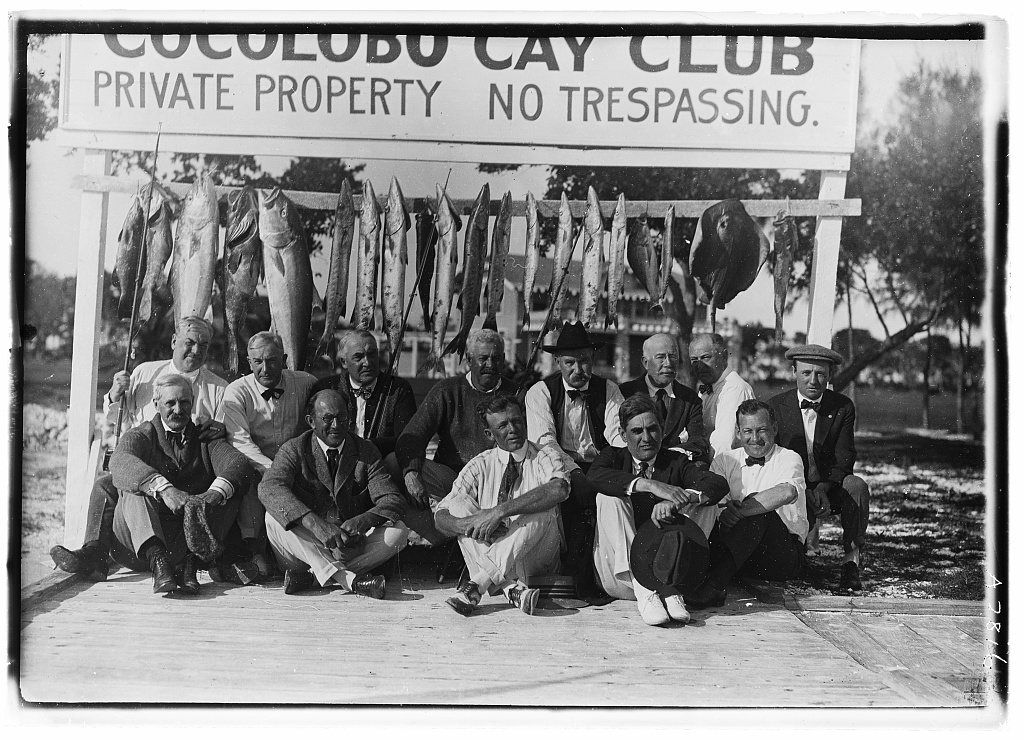

Carl G. Fisher

Carl Graham Fisher (January 12, 1874 – July 15, 1939) was an American entrepreneur. He was an important figure in the automotive industry, in highway construction, and in real estate development.

In his early life in Indiana, despite fa ...

, who was responsible for much of the development of Miami Beach, bought Adams Key

Adams Key is an island north of the upper Florida Keys in Biscayne National Park. It is in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It is located west of the southern tip of Elliott Key, on the north side of Caesar Creek in the lower part of Biscayne Bay. Th ...

, once known as Cocolobo Key, in 1916 and built the Cocolobo Cay Club

The Cocolobo Cay Club, later known as the Coco Lobo Club, was a private club on Adams Key in what is now Biscayne National Park, Florida. It was notable as a destination for the rich and the politically well-connected. Four presidents ( Warren G ...

in 1922. The two-story club building had ten guest rooms, a dining room, and a separate recreation lodge. Patrons included Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

, Albert Fall

Albert Bacon Fall (November 26, 1861November 30, 1944) was a United States senator from New Mexico and the Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding, infamous for his involvement in the Teapot Dome scandal; he was the only perso ...

, T. Coleman du Pont, Harvey Firestone

Harvey Samuel Firestone (December 20, 1868 – February 7, 1938) was an American businessman, and the founder of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, one of the first global makers of automobile tires.

Family background

Firestone was born o ...

, Jack Dempsey

William Harrison "Jack" Dempsey (June 24, 1895 – May 31, 1983), nicknamed Kid Blackie and The Manassa Mauler, was an American professional boxer who competed from 1914 to 1927, and reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926. ...

, Charles F. Kettering

Charles Franklin Kettering (August 29, 1876 – November 25, 1958) sometimes known as Charles Fredrick Kettering was an American inventor, engineer, businessman, and the holder of 186 patents.

For the list of patents issued to Kettering, see, Le ...

, Will Rogers

William Penn Adair Rogers (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) was an American vaudeville performer, actor, and humorous social commentator. He was born as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, in the Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma ...

and Frank Seiberling

Franklin Augustus “Frank” Seiberling''Find A Grave'', database and imageshttps://www.findagrave.com: accessed 24 August 2019), memorial page for Franklin Augustus “Frank” Seiberling (6 Oct 1859–11 Aug 1955), Find A Grave Memorial no51433 ...

.Shumaker, p. 57 Israel Jones' sons Lancelot and Arthur dropped out of the lime-growing business after competition from Mexican limes made their business less profitable, and after a series of devastating hurricanes in 1938 they became full-time fishing guides at the Cocolobo Club. The club had declined with the crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

which cost Fisher his fortune, but was revived by Garfield Wood

Garfield Arthur "Gar" Wood (December 4, 1880 – June 19, 1971) was an American inventor, entrepreneur, and championship motorboat builder and racer who held the world water speed record on several occasions. He was the first man to travel ...

in 1934.Shumaker, p. 59 Among the Joneses' clients was avid fisherman Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

and his family. The Joneses also provided the club with fish, lobster and crabs. Arthur and Lancelot Jones were the second largest landowners and the only permanent residents of the lower Biscayne Bay keys during the 1960s. Wood sold the Cocolobo Cay Club to a group of investors led by Miami banker Bebe Rebozo

Charles Gregory "Bebe" (pronounced ) Rebozo (November 17, 1912 – May 8, 1998) was an American Florida-based banker and businessman who was a friend and confidant of President Richard Nixon.

Early life

The youngest of 12 children (he ...

in 1954, who renamed it the Coco Lobo Fishing Club. Clients guided by the Joneses included then-senators John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, Herman Talmadge

Herman Eugene Talmadge (August 9, 1913 – March 21, 2002) was an American politician who served as governor of Georgia in 1947 and from 1948 to 1955 and as a U.S. Senator from Georgia from 1957 to 1981. Talmadge, a Democrat, served during a tim ...

and George Smathers

George Armistead Smathers (November 14, 1913 – January 20, 2007) was an American lawyer and politician who represented the state of Florida in the United States Senate from 1951 until 1969 and in the United States House from 1947 to 1951, as ...

through the 1940s and 1950s.Shumaker, p. 61

During the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

the future park area was a training ground for Cuban exiles training for missions in Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

's Cuba. Elliott Key in particular was used by the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

as a training area in the early 1960s in preparation for Bay of Pigs invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fina ...

. The largest facility was Ledbury Lodge, the only hotel ever built on the key. As late as 1988 a group of Cuban exiles were arrested when they tried to use the key for a mock landing. Farther north, exiled Venezuelan president Marcos Pérez Jiménez

Marcos Evangelista Pérez Jiménez (25 April 1914 – 20 September 2001) was a Venezuelan military and general officer of the Army of Venezuela and the dictator of Venezuela from 1950 to 1958, ruling as member of the military junta from 195 ...

kept a house on Soldier Key until he was extradited in 1963.Hach, pp. 35–36

Proposed development

As modern communities grew in and around Miami, developers looked to southern Dade County for new projects. The undeveloped keys south of Key Biscayne were viewed as prime development territory. Beginning in the 1890s local interests promoted the construction of a causeway to the mainland. One proposal included building a highway linking the Biscayne Bay keys to the

As modern communities grew in and around Miami, developers looked to southern Dade County for new projects. The undeveloped keys south of Key Biscayne were viewed as prime development territory. Beginning in the 1890s local interests promoted the construction of a causeway to the mainland. One proposal included building a highway linking the Biscayne Bay keys to the Overseas Highway

The Overseas Highway is a highway carrying U.S. Route 1 (US 1) through the Florida Keys to Key West. Large parts of it were built on the former right-of-way of the Overseas Railroad, the Key West Extension of the Florida East Coast Railwa ...

at Key Largo and to the developed barrier islands to the north. At the same time, pressure built to accommodate industrial development in South Florida. This led to competing priorities between those who wanted to develop for residential and leisure use and those in favor of industrial and infrastructure development. On December 6, 1960, 12 of the 18 area landowners who favored development voted to create the City of Islandia on Elliott Key. The town was incorporated to encourage Dade County to improve access to Elliott Key in particular, which landowners viewed as a potential rival to Miami Beach. The new city lobbied for causeway access and formed a negotiating bloc to attract potential developers.

In 1962 an industrial seaport was proposed for the mainland shores of Biscayne Bay, to be known as SeaDade. SeaDade, supported by billionaire shipping magnate Daniel K. Ludwig, would have included an oil refinery. In addition to the physical structures, it would have been necessary to dredge a channel through the bay for large ships to access the refinery. The channel would have also required cutting through the coral reef to get to the deep water. In 1963 Florida Power and Light

Florida Power & Light Company (FPL), the principal subsidiary of NextEra Energy Inc. (formerly FPL Group, Inc.), is the largest power utility in Florida. It is a Juno Beach, Florida-based power utility company serving roughly 5 million customers ...

(FP&L) announced plans for two new 400-megawatt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of Power (physics), power or radiant flux in the International System of Units, International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantification (science), ...

oil-fired power plants on undeveloped land at Turkey Point.

Many local residents and politicians supported SeaDade because it would have created additional jobs, but a group of early environmentalists thought the costs were too high. They fought against development of the bay and formed the Safe Progress Association. Led by Lloyd Miller, the president of the local chapter of the Izaak Walton League

The Izaak Walton League is an American environmental organization founded in 1922 that promotes natural resource protection and outdoor recreation. The organization was founded in Chicago, Illinois, by a group of sportsmen who wished to protect fi ...

, ''Miami Herald

The ''Miami Herald'' is an American daily newspaper owned by the McClatchy Company and headquartered in Doral, Florida, a List of communities in Miami-Dade County, Florida, city in western Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade County and the M ...

'' reporter Juanita Greene

Juanita Greene (1924 - 2017) was an American journalist and conservationist. She worked for the ''Miami Herald'' as a reporter and wrote about Everglades National Park and Biscayne National Park. She was the ''Herald's'' first environmental report ...

, and Art Marshall, the opponents of industrialization proposed the creation of a national park unit that would protect the reefs, islands and bay. After initial skepticism, the park proposal obtained the support of ''Miami Herald'' editors, as well as Florida Congressman Dante Fascell

Dante Bruno Fascell (March 9, 1917 – November 28, 1998) was an American politician who represented Florida as a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1955 to 1993. He served as chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee ...

and Florida Governor Claude R. Kirk, Jr.

Claude Roy Kirk Jr. (January 7, 1926 – September 28, 2011) was the 36th governor of the U.S. state of Florida (1967–1971). He was the first Republican governor of Florida since Reconstruction.

Early life

Kirk was born in San Bernardino, Ca ...

, and were supported by lobbying efforts by sympathetic businessmen including Herbert Hoover, Jr.

One vision of Islandia, supported by land owners, would have connected the northern Florida Keys – from Key Biscayne to Key Largo – with bridges and created new islands using the fill from the SeaDade channel. Although Miami-area politicians and the state of Florida did not support Ludwig's SeaDade plans, Islandia's supporters continued to lobby for development support. In 1968, when it appeared the area was about to become a national monument, Islandia supporters bulldozed a highway six lanes wide down the center of the island, destroying the forest for . Islandia landowners called it Elliott Key Boulevard, but called it "Spite Highway" privately. It was hoped that since there was so much environmental damage, no one would want it for a national monument. Over time in the near-tropical climate, the forest grew back and now the only significant hiking trail on Elliott Key now follows the path of Elliott Key Boulevard.

The oil-fired Turkey Point power stations were completed in 1967–68 and experienced immediate problems from the discharge of hot cooling water into Biscayne Bay, where the heat killed marine grasses. In 1964 FP&L announced plans for two 693 MW nuclear reactors at the site, which were expected to compound the cooling water problem. Because of the shallowness of Biscayne Bay, the power stations were projected to consume a significant proportion of the bay's waters each day for cooling. After extensive negotiations and litigation with both the state and with Ludwig, who owned lands needed for cooling water canals, a closed-loop canal system was built south of the power plants and the nuclear units became operational in the early 1970s.

Portions of the present park were used for recreation prior to the park's establishment. Homestead Bayfront Park, still operated by Miami-Dade County just south of Convoy Point, established a "blacks-only" segregated beach for African-Americans at the present site of the Dante Fascell Visitor Center. The segregated beach operated through the 1950s into the early 1960s before segregated public facilities were abolished.

The oil-fired Turkey Point power stations were completed in 1967–68 and experienced immediate problems from the discharge of hot cooling water into Biscayne Bay, where the heat killed marine grasses. In 1964 FP&L announced plans for two 693 MW nuclear reactors at the site, which were expected to compound the cooling water problem. Because of the shallowness of Biscayne Bay, the power stations were projected to consume a significant proportion of the bay's waters each day for cooling. After extensive negotiations and litigation with both the state and with Ludwig, who owned lands needed for cooling water canals, a closed-loop canal system was built south of the power plants and the nuclear units became operational in the early 1970s.

Portions of the present park were used for recreation prior to the park's establishment. Homestead Bayfront Park, still operated by Miami-Dade County just south of Convoy Point, established a "blacks-only" segregated beach for African-Americans at the present site of the Dante Fascell Visitor Center. The segregated beach operated through the 1950s into the early 1960s before segregated public facilities were abolished.

Park establishment and history

The earliest proposals for the protection of Biscayne Bay were part of proposals by Everglades National Park advocate Ernest F. Coe, whose proposed Everglades park boundaries included Biscayne Bay, its keys, interior country including what are now Homestead and

The earliest proposals for the protection of Biscayne Bay were part of proposals by Everglades National Park advocate Ernest F. Coe, whose proposed Everglades park boundaries included Biscayne Bay, its keys, interior country including what are now Homestead and Florida City

Florida City is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. It is the southernmost municipality in the South Florida metropolitan area. Florida City is primarily a Miami suburb and a major agricultural area. As of the 2020 census, it ...

, and Key Largo. Biscayne Bay, Key Largo and the adjoining inland extensions were cut from Everglades National Park before its establishment in 1947. When proposals to develop Elliott Key surfaced in 1960, Lloyd Miller asked Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall

Stewart Lee Udall (January 31, 1920 – March 20, 2010) was an American politician and later, a federal government official. After serving three terms as a congressman from Arizona, he served as Secretary of the Interior from 1961 to 1969, unde ...

to send a Park Service reconnaissance team to review the Biscayne Bay area for inclusion in the national park system. A favorable report ensued, and with financial help from Herbert Hoover, Jr., political support was solicited, most notably from Congressman Fascell. A area of Elliott Key was by this time a part of the Dade County park system. The 1966 report noted the proposed park contained the best remaining areas of tropical forest in Florida and a rare combination of "terrestrial, marine and amphibious life," as well as significant recreational value. The report found the most significant virtues of the potential park were "the clear, sparkling waters, marine life, and the submerged lands of Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Here in shallow water is a veritable wonderland."

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Public Law 90-606 to create Biscayne National Monument on October 18, 1968. The monument was expanded in 1974 under Public Law 93-477 and expanded again when the monument was redesignated a national park by an act of Congress through Public Law 96-287, effective June 28, 1980. The 1980 expansion extended the park almost to Key Biscayne and included Boca Chita Key, the Ragged Keys and the Safety Valve shoal region, together with the corresponding offshore reefs and a substantial portion of central Biscayne Bay.NPS, ''Draft General Management Plan'', pp. 295–299NPCA, p. 9

The first Islandia property owner to sell land to the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

was Lancelot Jones, together with Katherine Jones, Arthur's widow. They sold their lands for $1,272,500, about a third of the potential development value. Jones was given a life estate on at the age of 70. He visited with park rangers stationed at the former Cocolobo Club, which eventually burned down in 1975. The other life estate in the park was held by Virginia Tannehill, the widow of Eastern Airlines

Eastern Air Lines, also colloquially known as Eastern, was a major United States airline from 1926 to 1991. Before its dissolution, it was headquartered at Miami International Airport in an unincorporated area of Miami-Dade County, Florida.

Ea ...

executive Paul Tannehill. Jones' house built by Lancelot, his father and his brother, burned down in 1982. He lived in a two-room shack for the next ten years, riding out hurricanes on Porgy Key, but left his home permanently just before Hurricane Andrew in 1992. The house was destroyed and Jones remained in Miami until his death in 1997 at 99 years.

Deprived of a rationale for existence by the national monument's establishment, Islandia languished. The hiring of a police chief in 1989 prompted questions from the National Park Service to the Dade County state attorney's office, headed by Janet Reno

Janet Wood Reno (July 21, 1938 – November 7, 2016) was an American lawyer who served as the 78th United States attorney general. She held the position from 1993 to 2001, making her the second-longest serving attorney general, behind only Wi ...

. In 1990 Reno's office determined after investigation that all of the town's elections were invalid, since the elections were restricted only to landowners, not residents. The town was finally abolished by the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners in March 2012.

The impact of Hurricane Andrew on neighboring Homestead Air Force Base

Homestead Air Reserve Base (Homestead ARB), previously known as Homestead Air Force Base (Homestead AFB) is located in Miami–Dade County, Florida to the northeast of the city of Homestead. It is home to the 482nd Fighter Wing (482 FW) of th ...

caused the Air Force to consider closing the base and conveying it to Miami-Dade County, which was interested in using the base for commercial air traffic as an alternative to Miami International Airport

Miami International Airport , also known as MIA and historically as Wilcox Field, is the primary airport serving the greater Miami metropolitan area with over 1,000 daily flights to 167 domestic and international destinations, including most co ...

. An environmental impact study concluded the resulting flight paths over the bay, only to the east, would result in degradation of the park. In 1999 The Air Force prohibited major commercial development at Homestead as a result.

The park's popularity as a destination for boaters has led to a high rate of accidents, some of them fatal. The

The park's popularity as a destination for boaters has led to a high rate of accidents, some of them fatal. The Columbus Day

Columbus Day is a national holiday in many countries of the Americas and elsewhere, and a federal holiday in the United States, which officially celebrates the anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the Americas on October 12, 1492.

...

weekend has been cited as the "most dangerous weekend of the year." An annual boating regatta in its 57th year in 2012 resulted in six deaths between 2002 and 2011, with damage to seabeds from vessel groundings and littering. Although official regatta activities take place outside the park, the area of Elliott Key has become a popular destination for some participants.

A fifth generating unit fueled by natural gas and oil was added to the Turkey Point generating station in 2007. In 2009, Turkey Point was proposed as the site of two new 1117 MW AP1000

The AP1000 is a nuclear power plant designed and sold by Westinghouse Electric Company. The plant is a pressurized water reactor with improved use of passive nuclear safety and many design features intended to lower its capital cost and improve ...

nuclear reactors, to be designated Turkey Point 6 and 7. If built, the new reactors would make Turkey Point one of the largest generating sites in the United States. Other neighboring influences on the bay are the agricultural lands of south Miami-Dade County, a sewage treatment facility on the park boundary at Black Point, and its neighbor, the South Miami-Dade Landfill.NPCA, p. 14

Activities

Biscayne National Park operates year-round. Camping is most practical in winter months, when mosquitoes are less troublesome on the keys. The Biscayne National Park Institute provides half and full day tours in the park that include snorkeling, hiking, paddling and sailing from the park headquarters. Boat excursions to Boca Chita Key and the area's lighthouses are also available. Licensed private concessionaires provide guided fishing, snorkeling, sailing, and sightseeing tours.

Biscayne National Park operates year-round. Camping is most practical in winter months, when mosquitoes are less troublesome on the keys. The Biscayne National Park Institute provides half and full day tours in the park that include snorkeling, hiking, paddling and sailing from the park headquarters. Boat excursions to Boca Chita Key and the area's lighthouses are also available. Licensed private concessionaires provide guided fishing, snorkeling, sailing, and sightseeing tours.

Recreation

Access to the park from the mainland is limited to the immediate vicinity of the Dante Fascell Visitor Center at Convoy Point. All other portions of the park are reachable only by private or concessioner boats. Activities include boating, fishing,kayaking

Kayaking is the use of a kayak for moving over water. It is distinguished from canoeing by the sitting position of the paddler and the number of blades on the paddle. A kayak is a low-to-the-water, canoe-like boat in which the paddler sits fac ...

, windsurfing

Windsurfing is a wind propelled water sport that is a combination of sailing and surfing. It is also referred to as "sailboarding" and "boardsailing", and emerged in the late 1960s from the aerospace and surf culture of California. Windsurfing ga ...

, snorkeling

Snorkeling ( British and Commonwealth English spelling: snorkelling) is the practice of swimming on or through a body of water while equipped with a diving mask, a shaped breathing tube called a snorkel, and usually swimfins. In cooler waters, a ...

and scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chris ...

. Miami-Dade County operates four marina parks near the park. Homestead Bayfront Park is directly adjacent to the park headquarters at Convoy Point. Farther south Black Point Park provides access to Adams and Elliott Keys. Matheson Hammock Park is near the north end of the park, and Crandon Park is on Key Biscayne.

Although it is a federally designated park, fishing within Biscayne is governed by the state of Florida. Anglers in Biscayne are required to have a Florida recreational saltwater fishing license. Fishing is limited to designated sport fish, spiny lobster

Spiny lobsters, also known as langustas, langouste, or rock lobsters, are a family (Palinuridae) of about 60 species of achelate crustaceans, in the Decapoda Reptantia. Spiny lobsters are also, especially in Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, So ...

, stone crab, blue crab Blue crab may refer to:

* Blue Crab 11, an American sailboat design

* ''Callinectes sapidus'' – Chesapeake or Atlantic blue crab of the West Atlantic, introduced elsewhere

* ''Cardisoma guanhumi'' – blue land crab of the West Atlantic

* '' Disc ...

and shrimp. Tropical reef fish may not be collected, nor may sharks, conch, sea urchins and other marine life. Reef life species such as coral and sponges are also protected from collecting by visitors. Additionally, lobstering is prohibited in the Biscayne Bay-Card Sound Lobster Sanctuary, administered by the state of Florida to protect spiny lobster breeding areas, which overlaps much of Biscayne Bay.

A private concessioner provides tours from the Park headquarters into the bay and to the keys. Most tours are operated during the peak winter season from January to April. Personal watercraft

A personal watercraft (PWC), also called water scooter or jet ski, is a recreational watercraft that a rider sits or stands on, not within, as in a boat. PWCs have two style categories, first and most popular being a runabout or "sit down" whe ...

are prohibited in Biscayne and most other national parks,NPS, ''Draft General Management Plan'', p. 12 but other private powerboats and sailboats are permitted.

Island facilities

Most of Biscayne's permanent facilities are on the offshore keys. A seasonally staffed ranger station is on Elliott Key, as well as a campground and 36 boat slips. A single loop trail runs from the harbor to the oceanfront, and a path following the Spite Highway runs the length of the island. Adams Key is a day-use-only area for visitors, although two Park Service residences are on the island. Boca Chita Key is the most-visited island, with a campground and picnic areas. The Boca Chita Lighthouse is occasionally open to visitors when staffing permits.Snorkeling and diving

Snorkeling and scuba diving on the offshore reefs are popular activities. The reefs have been the cause of many shipwrecks. A selection of wrecks have been the subjects of ranger-led snorkeling tours and have been organized as the Maritime Heritage Trail, the only underwater archaeological trail in the National Park Service system. The wrecks of the '' Arratoon Apcar'' (sank 1878), ''Erl King'' (1891), ''Alicia'' (1905), ''Lugano'' (1913) and ''Mandalay'' (1966) are on the trail together with an unknown wreck from the 1800s and the Fowey Rocks Lighthouse. The ''Alicia'', ''Erl King'' and ''Lugano'' are relatively deep wrecks, best suited for scuba dives. The ''Mandalay'' is at a shallower depth and is especially popular for snorkeling.Historical structures

Although most of Biscayne National Park's area is water, the islands have a number of protected historical structures and districts. Shipwrecks are also protected within the park, and the park's offshore waters are a protected historic district.

Although most of Biscayne National Park's area is water, the islands have a number of protected historical structures and districts. Shipwrecks are also protected within the park, and the park's offshore waters are a protected historic district.

Stiltsville

Stiltsville was established by Eddie "Crawfish" Walker in the 1930s as a small community of shacks built on pilings in a shallow section of Biscayne Bay, not far from Key Biscayne. Comprising 27 structures at its height in the 1960s, Stiltsville lost shacks to fires and hurricanes, with only seven surviving in 2012, none of them dating to the 1960s or earlier. The site was incorporated into Biscayne National Park in 1985, when the Park Service agreed to honor existing leases until July 1, 1999. Hurricane Andrew destroyed most of Stiltsville in 1992. The Park Service has undertaken to preserve the community, which is now unoccupied. The community is to be administered by a trust and used as accommodation for overnight camping, educational facilities and researchers.

Stiltsville was established by Eddie "Crawfish" Walker in the 1930s as a small community of shacks built on pilings in a shallow section of Biscayne Bay, not far from Key Biscayne. Comprising 27 structures at its height in the 1960s, Stiltsville lost shacks to fires and hurricanes, with only seven surviving in 2012, none of them dating to the 1960s or earlier. The site was incorporated into Biscayne National Park in 1985, when the Park Service agreed to honor existing leases until July 1, 1999. Hurricane Andrew destroyed most of Stiltsville in 1992. The Park Service has undertaken to preserve the community, which is now unoccupied. The community is to be administered by a trust and used as accommodation for overnight camping, educational facilities and researchers.

Other structures

Biscayne National Park includes a number of navigational aids, as well as an ornamental structure built to resemble a lighthouse. TheFowey Rocks Light

Fowey Rocks Light is located seven miles southeast of Cape Florida on Key Biscayne. The lighthouse was completed in 1878, replacing the Cape Florida Light. It was automated on May 7, 1975, and is still in operation. The structure is cast iron, wi ...

is a skeleton-frame cast iron structure built in 1878. Already included within the boundaries of the park, the light was acquired by the Park Service on October 2, 2012. The unmanned Pacific Reef Light is about three miles (5 km) offshore from Elliott Key. The original 1921 structure was replaced in 2000 and its lantern was placed on display in a park in Islamorada

Islamorada (also sometimes Islas Morada) is an incorporated village in Monroe County, Florida. It is located directly between Miami and Key West on five islands— Tea Table Key, Lower Matecumbe Key, Upper Matecumbe Key, Windley Key and Plant ...

.

Industrialist Mark C. Honeywell was a Cocolobo Club member who bought Boca Chita Key

Boca Chita Key is the island north of the upper Florida Keys in Biscayne National Park, Miami-Dade County, Florida.

The key is located in Biscayne Bay, just north of Sands Key. An ornamental lighthouse is present on the key.plantations developed by Israel Jones and his sons, and the Sweeting Homestead on Elliott Key. The frame structures associated with these plantations, together with those of the Cocolobo Cay Club and frame buildings on Boca Chita Key, have been destroyed by fire and hurricanes.NPS, ''Draft General Management Plan'', p. 151

South Florida is a transitional zone between the

South Florida is a transitional zone between the

Ecology

South Florida is a transitional zone between the

South Florida is a transitional zone between the Nearctic

The Nearctic realm is one of the eight biogeographic realms constituting the Earth's land surface.

The Nearctic realm covers most of North America, including Greenland, Central Florida, and the highlands of Mexico. The parts of North America t ...

and Neotropical realm

The Neotropical realm is one of the eight biogeographic realms constituting Earth's land surface. Physically, it includes the tropical terrestrial ecoregions of the Americas and the entire South American temperate zone.

Definition

In bioge ...

s, resulting in a wide variety of plant and animal life. The intersection of realms brings opportunities for visitors to see species, particularly birds, not seen elsewhere in North America. The park includes four distinct ecosystems, each supporting its own flora and fauna. Mangrove swamp, lagoon, island key and offshore reef habitats provide diversity for many species. In this semi-tropical environment, the seasons are differentiated mainly by rainfall. Warm to hot and wet summers bring occasional tropical storms. Though only marginally cooler, the winters tend to be relatively drier. Bay salinity varies accordingly, with lower salinity levels in the wet summer, trending to more fresh water on the west side where new fresh water flows in.

Hundreds of species of fish are present in park waters, including more than fifty crustacean species ranging from isopod

Isopoda is an order of crustaceans that includes woodlice and their relatives. Isopods live in the sea, in fresh water, or on land. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons, two pairs of antennae, seven pairs of jointed limbs on the thorax, an ...

s to giant blue land crabs, about two hundred species of birds and about 27 mammal species, both terrestrial and marine. Mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

s include a variety of bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

s, terrestrial and marine snails, sea hare

The clade Anaspidea, commonly known as sea hares (''Aplysia'' species and related genera), are medium-sized to very large opisthobranch gastropod molluscs with a soft internal shell made of protein. These are marine gastropod molluscs in the s ...

s, sea slug

Sea slug is a common name for some marine invertebrates with varying levels of resemblance to terrestrial slugs. Most creatures known as sea slugs are gastropods, i.e. they are sea snails (marine gastropod mollusks) that over evolutionary t ...

s and two cephalopod