In

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

, a species is the basic unit of

classification Classification is a process related to categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated and understood.

Classification is the grouping of related facts into classes.

It may also refer to:

Business, organizat ...

and a

taxonomic rank

In biological classification, taxonomic rank is the relative level of a group of organisms (a taxon) in an ancestral or hereditary hierarchy. A common system consists of species, genus, family (biology), family, order (biology), order, class (b ...

of an

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

, as well as a unit of

biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species (''species diversity''), and ecosystem (''ecosystem diversity'') l ...

. A species is often defined as the largest group of

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s in which any two individuals of the appropriate

sex

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing animal or plant produces male or female gametes. Male plants and animals produce smaller mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger ones ( ova, of ...

es or mating types can

produce

Produce is a generalized term for many farm-produced crops, including fruits and vegetables (grains, oats, etc. are also sometimes considered ''produce''). More specifically, the term ''produce'' often implies that the products are fresh and g ...

fertile

Fertility is the capability to produce offspring through reproduction following the onset of sexual maturity. The fertility rate is the average number of children born by a female during her lifetime and is quantified demographically. Fertilit ...

offspring

In biology, offspring are the young creation of living organisms, produced either by a single organism or, in the case of sexual reproduction, two organisms. Collective offspring may be known as a brood or progeny in a more general way. This ca ...

, typically by

sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

. Other ways of defining species include their

karyotype

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of metaphase chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is disce ...

,

DNA sequence,

morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

, behaviour or

ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

. In addition,

paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

s use the concept of the

chronospecies

A chronospecies is a species derived from a anagenesis, sequential development pattern that involves continual and uniform changes from an extinct ancestral form on an evolutionary scale. The sequence of alterations eventually produces a populatio ...

since

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

reproduction cannot be examined.

The most recent rigorous estimate for the total number of species of

eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s is between 8 and 8.7 million.

However, only about 14% of these had been described by 2011.

All species (except

virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es) are given a

two-part name, a "binomial". The first part of a binomial is the

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

to which the species belongs. The second part is called the

specific name or the

specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

(in

botanical nomenclature

Botanical nomenclature is the formal, scientific naming of plants. It is related to, but distinct from Alpha taxonomy, taxonomy. Plant taxonomy is concerned with grouping and classifying plants; botanical nomenclature then provides names for the ...

, also sometimes in

zoological nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the In ...

). For example, ''

Boa constrictor

The boa constrictor (scientific name also ''Boa constrictor''), also called the red-tailed boa, is a species of large, non-venomous, heavy-bodied snake that is frequently kept and bred in captivity. The boa constrictor is a member of the family B ...

'' is one of the species of the genus ''

Boa

Kwon Bo-ah (; born November 5, 1986), known professionally as BoA, is a South Korean singer, songwriter, dancer, record producer and actress. One of the most successful and influential Korean entertainers, she has been dubbed the " Queen of K- ...

'', with ''constrictor'' being the species' epithet.

While the definitions given above may seem adequate at first glance, when looked at more closely they represent problematic

species concept

The species problem is the set of questions that arises when biologists attempt to define what a species is. Such a definition is called a species concept; there are at least 26 recognized species concepts. A species concept that works well for se ...

s. For example, the boundaries between closely related species become unclear with

hybridisation, in a

species complex

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

of hundreds of similar

microspecies

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

, and in a

ring species

In biology, a ring species is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which interbreeds with closely sited related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too distantly relate ...

. Also, among organisms that reproduce only

asexually, the concept of a reproductive species breaks down, and each clone is potentially a

microspecies

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

. Although none of these are entirely satisfactory definitions, and while the concept of species may not be a perfect model of life, it is still an incredibly useful tool to scientists and

conservationists

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the f ...

for studying life on Earth, regardless of the theoretical difficulties. If species were fixed and clearly distinct from one another, there would be no problem, but

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary processes cause species to change. This obliges

taxonomists

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are given ...

to decide, for example, when enough change has occurred to declare that a lineage should be divided into multiple

chronospecies

A chronospecies is a species derived from a anagenesis, sequential development pattern that involves continual and uniform changes from an extinct ancestral form on an evolutionary scale. The sequence of alterations eventually produces a populatio ...

, or when populations have diverged to have enough distinct character states to be described as

cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

species.

Species were seen from the time of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

until the 18th century as fixed categories that could be arranged in a hierarchy, the

great chain of being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, humans, animals and plants to minerals.

The great c ...

. In the 19th century, biologists grasped that species could evolve given sufficient time.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's 1859 book ''

On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' explained how

species could arise by

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

. That understanding was

greatly extended in the 20th century through

genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

and population

ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overlaps wi ...

. Genetic variability arises from

mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

s and

recombination, while organisms themselves are mobile, leading to

geographical isolation

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

and

genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

with varying

selection pressures

Any cause that reduces or increases reproductive success in a portion of a population potentially exerts evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of ...

. Genes can sometimes be exchanged between species by

horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

; new species can arise rapidly through hybridisation and

polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contain ...

y; and species may

become extinct for a variety of reasons.

Viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

are a special case, driven by a

balance of mutation and selection, and can be treated as

quasispecies

The quasispecies model is a description of the process of the Darwinian evolution of certain self-replicating entities within the framework of physical chemistry. A quasispecies is a large group or "cloud" of related genotypes that exist in an en ...

.

Definition

Biologists and taxonomists have made many attempts to define species, beginning from

morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

and moving towards

genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

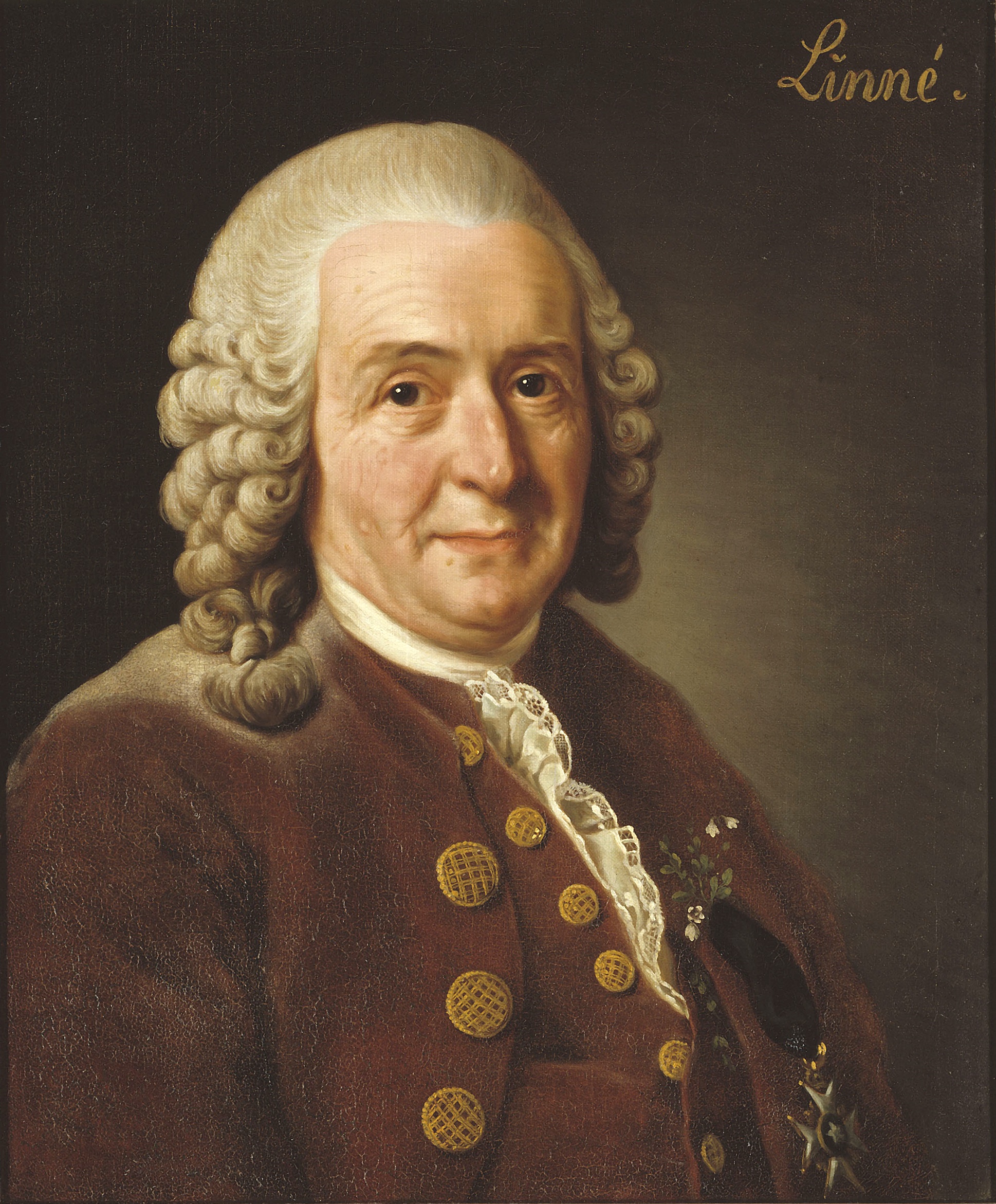

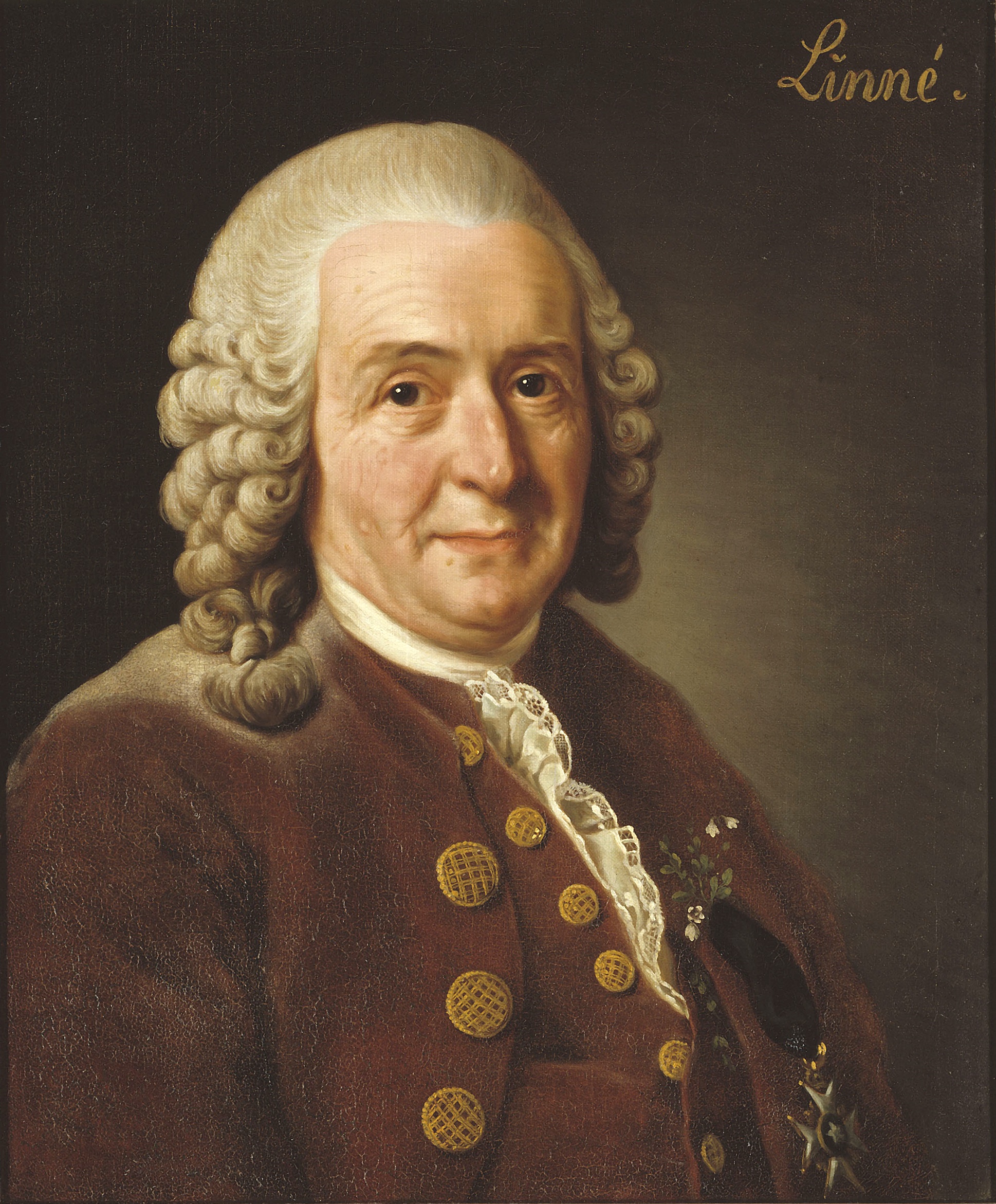

. Early taxonomists such as Linnaeus had no option but to describe what they saw: this was later formalised as the typological or morphological species concept.

Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

emphasised reproductive isolation, but this, like other species concepts, is hard or even impossible to test.

Later biologists have tried to refine Mayr's definition with the recognition and cohesion concepts, among others. Many of the concepts are quite similar or overlap, so they are not easy to count: the biologist R. L. Mayden recorded about 24 concepts,

and the philosopher of science

John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the fe ...

counted 26.

Wilkins further grouped the species concepts into seven basic kinds of concepts: (1)

agamospecies

In botany, apomixis is asexual reproduction without fertilization. Its etymology is Greek for "away from" + "mixing". This definition notably does not mention meiosis. Thus "normal asexual reproduction" of plants, such as propagation from cuttin ...

for asexual organisms (2) biospecies for reproductively isolated sexual organisms (3)

ecospecies based on ecological niches (4) evolutionary species based on lineage (5) genetic species based on gene pool (6) morphospecies based on form or phenotype and (7) taxonomic species, a species as determined by a taxonomist.

Typological or morphological species

A typological species is a group of organisms in which individuals conform to certain fixed properties (a type), so that even pre-literate people often recognise the same taxon as do modern taxonomists.

The clusters of variations or phenotypes within specimens (such as longer or shorter tails) would differentiate the species. This method was used as a "classical" method of determining species, such as with Linnaeus, early in evolutionary theory. However, different phenotypes are not necessarily different species (e.g. a four-winged ''

Drosophila

''Drosophila'' () is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many species ...

'' born to a two-winged mother is not a different species). Species named in this manner are called ''morphospecies''.

In the 1970s,

Robert R. Sokal

Robert Reuven Sokal (January 13, 1926 in Vienna, Austria – April 9, 2012 in Stony Brook, New York) was an Austrian-American biostatistician and entomologist. Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the Stony Brook University, Sokal was a member ...

, Theodore J. Crovello and

Peter Sneath

Peter Henry Andrews Sneath FRS, MD (17 November 1923 – September 9, 2011) was a microbiologist who co-founded the field of numerical taxonomy, together with Robert R. Sokal

Robert Reuven Sokal (January 13, 1926 in Vienna, Austria – Ap ...

proposed a variation on the morphological species concept, a

phenetic

In biology, phenetics ( el, phainein – to appear) , also known as taximetrics, is an attempt to classify organisms based on overall similarity, usually in morphology or other observable traits, regardless of their phylogeny or evolutionary rel ...

species, defined as a set of organisms with a similar

phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

to each other, but a different phenotype from other sets of organisms. It differs from the morphological species concept in including a numerical measure of distance or similarity to cluster entities based on multivariate comparisons of a reasonably large number of phenotypic traits.

Recognition and cohesion species

A mate-recognition species is a group of sexually reproducing organisms that recognise one another as potential mates. Expanding on this to allow for post-mating isolation, a cohesion species is the most inclusive population of individuals having the potential for phenotypic cohesion through intrinsic cohesion mechanisms; no matter whether populations can hybridise successfully, they are still distinct cohesion species if the amount of hybridisation is insufficient to completely mix their respective

gene pool

The gene pool is the set of all genes, or genetic information, in any population, usually of a particular species.

Description

A large gene pool indicates extensive genetic diversity, which is associated with robust populations that can surv ...

s.

A further development of the recognition concept is provided by the biosemiotic concept of species.

Genetic similarity and barcode species

In

microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

, genes can move freely even between distantly related bacteria, possibly extending to the whole bacterial domain. As a rule of thumb, microbiologists have assumed that members of

Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

or

Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

with

16S ribosomal RNA

16 S ribosomal RNA (or 16 S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome (SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as 16S rRNA ...

gene sequences more similar than 97% to each other need to be checked by

DNA–DNA hybridisation to decide if they belong to the same species. This concept was narrowed in 2006 to a similarity of 98.7%.

The

average nucleotide identity

Bacterial genomes are generally smaller and less variant in size among species when compared with genomes of eukaryotes. Bacterial genomes can range in size anywhere from about 130 kbp to over 14 Mbp. A study that included, but was not limited to ...

method quantifies

genetic distance

Genetic distance is a measure of the genetic divergence between species or between populations within a species, whether the distance measures time from common ancestor or degree of differentiation. Populations with many similar alleles have sma ...

between entire

genomes

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding gen ...

, using regions of about 10,000

base pairs

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

. With enough data from genomes of one genus, algorithms can be used to categorize species, as for ''

Pseudomonas avellanae

''Pseudomonas avellanae'' is a Gram-negative plant pathogenic bacterium. It is the causal agent of bacterial canker of hazelnut (''Corylus avellana''). Based on 16S rRNA analysis, ''P. avellanae'' has been placed in the ''P. syringae'' group. Thi ...

'' in 2013,

[ ] This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under th

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under th

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

license. and for all sequenced bacteria and archaea since 2020.

DNA barcoding

DNA barcoding is a method of species identification using a short section of DNA from a specific gene or genes. The premise of DNA barcoding is that by comparison with a reference library of such DNA sections (also called "sequences"), an indiv ...

has been proposed as a way to distinguish species suitable even for non-specialists to use. One of the barcodes is a region of mitochondrial DNA within the gene for

cytochrome c oxidase

The enzyme cytochrome c oxidase or Complex IV, (was , now reclassified as a translocasEC 7.1.1.9 is a large transmembrane protein complex found in bacteria, archaea, and mitochondria of eukaryotes.

It is the last enzyme in the respiratory electr ...

. A database,

Barcode of Life Data System

The Barcode of Life Data System (commonly known as BOLD or BOLDSystems) is a web platform specifically devoted to DNA barcoding. It is a cloud-based data storage and analysis platform developed at the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics in Canada. It ...

, contains DNA barcode sequences from over 190,000 species.

However, scientists such as Rob DeSalle have expressed concern that classical taxonomy and DNA barcoding, which they consider a misnomer, need to be reconciled, as they delimit species differently.

Genetic introgression

Introgression, also known as introgressive hybridization, in genetics is the transfer of genetic material from one species into the gene pool of another by the repeated backcrossing of an interspecific hybrid with one of its parent species. Introg ...

mediated by

endosymbionts

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

and other vectors can further make barcodes ineffective in the identification of species.

Phylogenetic or cladistic species

A phylogenetic or

cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

species is "the smallest aggregation of populations (sexual) or lineages (asexual) diagnosable by a unique combination of character states in comparable individuals (semaphoronts)".

The empirical basis – observed character states – provides the evidence to support hypotheses about evolutionarily divergent lineages that have maintained their hereditary integrity through time and space. Molecular markers may be used to determine diagnostic genetic differences in the nuclear or

mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

of various species.

For example, in a study done on

fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, studying the nucleotide characters using cladistic species produced the most accurate results in recognising the numerous fungi species of all the concepts studied.

Versions of the phylogenetic species concept that emphasise monophyly or diagnosability may lead to splitting of existing species, for example in

Bovidae

The Bovidae comprise the biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes cattle, bison, buffalo, antelopes, and caprines. A member of this family is called a bovid. With 143 extant species and 300 known extinct species, ...

, by recognising old subspecies as species, despite the fact that there are no reproductive barriers, and populations may intergrade morphologically. Others have called this approach

taxonomic inflation

''Taxonomic inflation'' is a pejorative term for what is perceived to be an excessive increase in the number of recognised taxa in a given context, due not to the discovery of new taxa but rather to putatively arbitrary changes to how taxa are deli ...

, diluting the species concept and making taxonomy unstable. Yet others defend this approach, considering "taxonomic inflation" pejorative and labelling the opposing view as "taxonomic conservatism"; claiming it is politically expedient to split species and recognise smaller populations at the species level, because this means they can more easily be included as

endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inva ...

in the

IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

red list

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biologi ...

and can attract conservation legislation and funding.

Unlike the biological species concept, a cladistic species does not rely on reproductive isolation – its criteria are independent of processes that are integral in other concepts.

Therefore, it applies to asexual lineages.

However, it does not always provide clear cut and intuitively satisfying boundaries between taxa, and may require multiple sources of evidence, such as more than one polymorphic locus, to give plausible results.

Evolutionary species

An evolutionary species, suggested by

George Gaylord Simpson

George Gaylord Simpson (June 16, 1902 – October 6, 1984) was an American paleontologist. Simpson was perhaps the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, and a major participant in the Modern synthesis (20th century), modern ...

in 1951, is "an entity composed of organisms which maintains its identity from other such entities through time and over space, and which has its own independent evolutionary fate and historical tendencies".

[ This differs from the biological species concept in embodying persistence over time. Wiley and Mayden stated that they see the evolutionary species concept as "identical" to ]Willi Hennig

Emil Hans Willi Hennig (20 April 1913 – 5 November 1976) was a Germans, German biologist and zoologist who is considered the founder of Phylogenesis, phylogenetic systematics, otherwise known as cladistics. In 1945 as a POWs in World War II, p ...

's species-as-lineages concept, and asserted that the biological species concept, "the several versions" of the phylogenetic species concept, and the idea that species are of the same kind as higher taxa are not suitable for biodiversity studies (with the intention of estimating the number of species accurately). They further suggested that the concept works for both asexual and sexually-reproducing species. A version of the concept is Kevin de Queiroz

Kevin de Queiroz is a vertebrate, evolutionary, and systematic biologist. He has worked in the phylogenetics and evolutionary biology of squamate reptiles, the development of a unified species concept and of a phylogenetic approach to biologica ...

's "General Lineage Concept of Species".

Ecological species

An ecological species is a set of organisms adapted to a particular set of resources, called a niche, in the environment. According to this concept, populations form the discrete phenetic clusters that we recognise as species because the ecological and evolutionary processes controlling how resources are divided up tend to produce those clusters.

Genetic species

A genetic species as defined by Robert Baker and Robert Bradley is a set of genetically isolated interbreeding populations. This is similar to Mayr's Biological Species Concept, but stresses genetic rather than reproductive isolation. In the 21st century, a genetic species can be established by comparing DNA sequences, but other methods were available earlier, such as comparing karyotype

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of metaphase chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is disce ...

s (sets of chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s) and allozyme

Alloenzymes (or also called allozymes) are variant forms of an enzyme which differ structurally but not functionally from other allozymes coded for by different alleles at the same locus. These are opposed to isozymes, which are enzymes that perfo ...

s (enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

variants).

Evolutionarily significant unit

An evolutionarily significant unit An evolutionarily significant unit (ESU) is a population of organisms that is considered distinct for purposes of conservation. Delineating ESUs is important when considering conservation action.

This term can apply to any species, subspecies, geo ...

(ESU) or "wildlife species" is a population of organisms considered distinct for purposes of conservation.

Chronospecies

In

In palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, with only comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

(morphology) from fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s as evidence, the concept of a chronospecies

A chronospecies is a species derived from a anagenesis, sequential development pattern that involves continual and uniform changes from an extinct ancestral form on an evolutionary scale. The sequence of alterations eventually produces a populatio ...

can be applied. During anagenesis

Anagenesis is the gradual evolution of a species that continues to exist as an interbreeding population. This contrasts with cladogenesis, which occurs when there is branching or splitting, leading to two or more lineages and resulting in separate ...

(evolution, not necessarily involving branching), palaeontologists seek to identify a sequence of species, each one derived from the phyletically extinct one before through continuous, slow and more or less uniform change. In such a time sequence, palaeontologists assess how much change is required for a morphologically distinct form to be considered a different species from its ancestors.

Viral quasispecies

Viruses have enormous populations, are doubtfully living since they consist of little more than a string of DNA or RNA in a protein coat, and mutate rapidly. All of these factors make conventional species concepts largely inapplicable. A viral quasispecies

The quasispecies model is a description of the process of the Darwinian evolution of certain self-replicating entities within the framework of physical chemistry. A quasispecies is a large group or "cloud" of related genotypes that exist in an en ...

is a group of genotypes related by similar mutations, competing within a highly mutagenic

In genetics, a mutagen is a physical or chemical agent that permanently changes genetic material, usually DNA, in an organism and thus increases the frequency of mutations above the natural background level. As many mutations can cause cancer in ...

environment, and hence governed by a mutation–selection balance

Mutation–selection balance is an equilibrium in the number of deleterious alleles in a population that occurs when the rate at which deleterious alleles are created by mutation equals the rate at which deleterious alleles are eliminated by select ...

. It is predicted that a viral quasispecies at a low but evolutionarily neutral

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

and highly connected (that is, flat) region in the fitness landscape

Fitness may refer to:

* Physical fitness, a state of health and well-being of the body

* Fitness (biology), an individual's ability to propagate its genes

* Fitness (cereal), a brand of breakfast cereals and granola bars

* ''Fitness'' (magazine), ...

will outcompete a quasispecies located at a higher but narrower fitness peak in which the surrounding mutants are unfit, "the quasispecies effect" or the "survival of the flattest". There is no suggestion that a viral quasispecies resembles a traditional biological species.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) authorizes and organizes the taxonomic classification of and the nomenclatures for viruses. The ICTV has developed a universal taxonomic scheme for viruses, and thus has the means to app ...

has since 1962 developed a universal taxonomic scheme for viruses; this has stabilised viral taxonomy.

Mayr's biological species concept

Most modern textbooks make use of

Most modern textbooks make use of Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

's 1942 definition, known as the Biological Species Concept

The species problem is the set of questions that arises when biologists attempt to define what a species is. Such a definition is called a species concept; there are at least 26 recognized species concepts. A species concept that works well for se ...

as a basis for further discussion on the definition of species. It is also called a reproductive or isolation concept. This defines a species as

The species problem

It is difficult to define a species in a way that applies to all organisms.species problem

The species problem is the set of questions that arises when biologists attempt to define what a species is. Such a definition is called a species concept; there are at least 26 recognized species concepts. A species concept that works well for se ...

.On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'':

When Mayr's concept breaks down

A simple textbook definition, following Mayr's concept, works well for most

A simple textbook definition, following Mayr's concept, works well for most multi-celled organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- ...

s, but breaks down in several situations:

* When organisms reproduce asexually, as in single-celled organism

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms an ...

s such as bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and other prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s, and parthenogenetic

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and development ...

or apomictic

In botany, apomixis is asexual reproduction without fertilization. Its etymology is Greek for "away from" + "mixing". This definition notably does not mention meiosis. Thus "normal asexual reproduction" of plants, such as propagation from cuttin ...

multi-celled organisms. DNA barcoding

DNA barcoding is a method of species identification using a short section of DNA from a specific gene or genes. The premise of DNA barcoding is that by comparison with a reference library of such DNA sections (also called "sequences"), an indiv ...

and phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek language, Greek wikt:φυλή, φυλή/wikt:φῦλον, φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary his ...

are commonly used in these cases.palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, as breeding experiments are not possible.

* When hybridisation permits substantial gene flow between species.

* In ring species

In biology, a ring species is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which interbreeds with closely sited related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too distantly relate ...

, when members of adjacent populations in a widely continuous distribution range interbreed successfully but members of more distant populations do not.

Species identification is made difficult by discordance between molecular and morphological investigations; these can be categorised as two types: (i) one morphology, multiple lineages (e.g. morphological convergence, cryptic species

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

) and (ii) one lineage, multiple morphologies (e.g. phenotypic plasticity

Phenotypic plasticity refers to some of the changes in an organism's behavior, morphology and physiology in response to a unique environment. Fundamental to the way in which organisms cope with environmental variation, phenotypic plasticity encompa ...

, multiple life-cycle stages). In addition, horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

(HGT) makes it difficult to define a species.[ All species definitions assume that an organism acquires its genes from one or two parents very like the "daughter" organism, but that is not what happens in HGT.]prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s, and at least occasionally between dissimilar groups of eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s,crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

s and echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea ...

s.James Mallet James Mallet (born 15 March 1955 in London) is an evolutionary zoologist specialising in entomology.

He was educated at Winchester College.

He became professor of biological diversity at the Department of Biology, University College London. He w ...

concludes that

Wilkins writes that biologists such as the botanist Brent Mishler

Brent D. Mishler (born 1953) is an American botanist who is director of the University and Jepson Herbaria at the University of California, Berkeley as well as Distinguished Professor in the Department of Integrative Biology, where he teaches phyl ...

Charles Tate Regan

Charles Tate Regan FRS (1 February 1878 – 12 January 1943) was a British ichthyologist, working mainly around the beginning of the 20th century. He did extensive work on fish classification schemes.

Born in Sherborne, Dorset, he was educat ...

's early 20th century remark that "a species is whatever a suitably qualified biologist chooses to call a species".Philip Kitcher

Philip Stuart Kitcher (born 20 February 1947) is a British philosopher who is John Dewey Professor Emeritus of philosophy at Columbia University. He specialises in the philosophy of science, the philosophy of biology, the philosophy of mathema ...

called this the "cynical species concept", and arguing that far from being cynical, it usefully leads to an empirical taxonomy for any given group, based on taxonomists' experience.

Aggregates of microspecies

The species concept is further weakened by the existence of microspecies

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

, groups of organisms, including many plants, with very little genetic variability, usually forming species aggregates.Taraxacum officinale

''Taraxacum officinale'', the dandelion or common dandelion, is a flowering herbaceous perennial plant of the dandelion genus in the family Asteraceae (syn. Compositae). The common dandelion is well known for its yellow flower heads that turn i ...

'' and the blackberry ''Rubus fruticosus

''Rubus fruticosus'' L. is the ambiguous name of a European blackberry species in the genus ''Rubus'' in the rose family. The name has been interpreted in several ways:

*The species represented by the type specimen of ''Rubus fruticosus'' L., ...

'' are aggregates with many microspecies—perhaps 400 in the case of the blackberry and over 200 in the dandelion, complicated by hybridisation, apomixis

In botany, apomixis is asexual reproduction without fertilization. Its etymology is Greek for "away from" + "mixing". This definition notably does not mention meiosis. Thus "normal asexual reproduction" of plants, such as propagation from cuttin ...

and polyploidy

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contain ...

, making gene flow between populations difficult to determine, and their taxonomy debatable.Heliconius

''Heliconius'' comprises a colorful and widespread genus of brush-footed butterflies commonly known as the longwings or heliconians. This genus is distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the New World, from South America a ...

'' butterflies,Hypsiboas

''Boana'' is a genus of frogs in the family Hylidae. They are commonly known as gladiator frogs, gladiator treefrogs or Wagler Neotropical treefrogs. These frogs are distributed in the tropical Central and South America from Nicaragua to Argent ...

'' treefrogs, and fungi such as the fly agaric

''Amanita muscaria'', commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita, is a basidiomycete of the genus ''Amanita''. It is also a muscimol mushroom. Native throughout the temperate and boreal regions of the Northern Hemisphere, ''Amanita muscar ...

.

File:Ripe, ripening, and green blackberries.jpg, Blackberries belong to any of hundreds of microspecies of the ''Rubus fruticosus

''Rubus fruticosus'' L. is the ambiguous name of a European blackberry species in the genus ''Rubus'' in the rose family. The name has been interpreted in several ways:

*The species represented by the type specimen of ''Rubus fruticosus'' L., ...

'' species aggregate

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

.

File:Heliconius mimicry.png, The butterfly genus ''Heliconius

''Heliconius'' comprises a colorful and widespread genus of brush-footed butterflies commonly known as the longwings or heliconians. This genus is distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the New World, from South America a ...

'' contains many similar species.

File:Systematics-of-treefrogs-of-the-Hypsiboas-calcaratus-and-Hypsiboas-fasciatus-species-complex-(Anura-ZooKeys-370-001-g009.jpg, The ''Hypsiboas calcaratus

Troschel's treefrog (''Boana calcarata''), also known as the blue-flanked treefrog or the convict treefrog, is a species of frog in the family Hylidae. It is found in most parts of the Amazon Basin, except in the southeast and the Guianas. Colomb ...

''–'' fasciatus'' species complex contains at least six species of treefrog.

Hybridisation

Natural hybridisation presents a challenge to the concept of a reproductively isolated species, as fertile hybrids permit gene flow between two populations. For example, the carrion crow

The carrion crow (''Corvus corone'') is a passerine bird of the family Corvidae and the genus ''Corvus'' which is native to western Europe and the eastern Palearctic.

Taxonomy and systematics

The carrion crow was one of the many species origi ...

''Corvus corone'' and the hooded crow

The hooded crow (''Corvus cornix''), also called the scald-crow or hoodie, is a Eurasian bird species in the genus ''Corvus''. Widely distributed, it is found across Northern, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe, as well as parts of the Middle Eas ...

''Corvus cornix'' appear and are classified as separate species, yet they hybridise freely where their geographical ranges overlap.Carrion crow

The carrion crow (''Corvus corone'') is a passerine bird of the family Corvidae and the genus ''Corvus'' which is native to western Europe and the eastern Palearctic.

Taxonomy and systematics

The carrion crow was one of the many species origi ...

File:20151221 hybrid Corvus corone × Corvus cornix.jpg, Hybrid with dark belly, dark gray nape

File:Corvus cornix (Scops).jpg, Hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two dif ...

with dark belly

File:Wrona_Siwa.jpg, Hooded crow

The hooded crow (''Corvus cornix''), also called the scald-crow or hoodie, is a Eurasian bird species in the genus ''Corvus''. Widely distributed, it is found across Northern, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe, as well as parts of the Middle Eas ...

Ring species

A ring species

In biology, a ring species is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which interbreeds with closely sited related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too distantly relate ...

is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which can sexually interbreed with adjacent related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too distantly related to interbreed, though there is a potential gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

between each "linked" population. Such non-breeding, though genetically connected, "end" populations may co-exist in the same region thus closing the ring. Ring species thus present a difficulty for any species concept that relies on reproductive isolation. However, ring species are at best rare. Proposed examples include the herring gull Herring gull is a common name for several birds in the genus ''Larus'', all formerly treated as a single species.

Three species are still combined in some taxonomies:

* American herring gull (''Larus smithsonianus'') - North America

* European he ...

-lesser black-backed gull

The lesser black-backed gull (''Larus fuscus'') is a large gull that breeds on the Atlantic coasts of Europe. It is migratory, wintering from the British Isles south to West Africa. It has increased dramatically in North America, most common alo ...

complex around the North pole, the ''Ensatina eschscholtzii

The ensatina (''Ensatina eschscholtzii'') is a species complex of plethodontid (lungless) salamanders found in coniferous forests, oak woodland and chaparral '' group of 19 populations of salamanders in America, and the greenish warbler

The greenish warbler (''Phylloscopus trochiloides'') is a widespread leaf warbler with a breeding range in northeastern Europe, and temperate to subtropical continental Asia. This warbler is strongly migratory and winters in India. It is not u ...

in Asia, but many so-called ring species have turned out to be the result of misclassification leading to questions on whether there really are any ring species.Larus

''Larus'' is a large genus of gulls with worldwide distribution (by far the greatest species diversity is in the Northern Hemisphere).

Many of its species are abundant and well-known birds in their ranges. Until about 2005–2007, most gulls ...

'' gulls interbreed in a ring around the Arctic.

File:PT05 ubt.jpeg, Opposite ends of the ring: a herring gull ('' Larus argentatus'') (front) and a lesser black-backed gull ('' Larus fuscus'') in Norway

File:Greenish Warbler Sikkim India 11.05.2014.jpg, A greenish warbler

The greenish warbler (''Phylloscopus trochiloides'') is a widespread leaf warbler with a breeding range in northeastern Europe, and temperate to subtropical continental Asia. This warbler is strongly migratory and winters in India. It is not u ...

, ''Phylloscopus trochiloides''

File:Greenish warbler ring.svg, Presumed evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

of five "species" of greenish warblers around the Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

s

Taxonomy and naming

Common and scientific names

The commonly used names for kinds of organisms are often ambiguous: "cat" could mean the domestic cat, ''Felis catus

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members of t ...

'', or the cat family, Felidae

Felidae () is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid (). The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the ...

. Another problem with common names is that they often vary from place to place, so that puma, cougar, catamount, panther, painter and mountain lion all mean ''Puma concolor

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large cat native to the Americas. Its range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere ...

'' in various parts of America, while "panther" may also mean the jaguar

The jaguar (''Panthera onca'') is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus '' Panthera'' native to the Americas. With a body length of up to and a weight of up to , it is the largest cat species in the Americas and the th ...

(''Panthera onca'') of Latin America or the leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant species in the genus '' Panthera'', a member of the cat family, Felidae. It occurs in a wide range in sub-Saharan Africa, in some parts of Western and Central Asia, Southern Russia, a ...

(''Panthera pardus'') of Africa and Asia. In contrast, the scientific names of species are chosen to be unique and universal; they are in two parts used together: the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

as in ''Puma'', and the specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

as in ''concolor''.

Species description

A species is given a

A species is given a taxonomic

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

name when a type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

is described formally, in a publication that assigns it a unique scientific name. The description typically provides means for identifying the new species, which may not be based solely on morphology (see cryptic species

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

), differentiating it from other previously described and related or confusable species and provides a validly published name

In botanical nomenclature, a validly published name is a name that meets the requirements in the '' International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants'' for valid publication. Valid publication of a name represents the minimum requir ...

(in botany) or an available name

In zoological nomenclature, an available name is a scientific name for a taxon of animals that has been published conforming to all the mandatory provisions of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature for the establishment of a zoological ...

(in zoology) when the paper is accepted for publication. The type material is usually held in a permanent repository, often the research collection of a major museum or university, that allows independent verification and the means to compare specimens.[One example of an abstract of an article naming a new species can be found at ]International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the ...

, are "appropriate, compact, euphonious, memorable, and do not cause offence".

Abbreviations

Books and articles sometimes intentionally do not identify species fully, using the abbreviation "sp." in the singular or "spp." (standing for ''species pluralis'', Latin for "multiple species") in the plural in place of the specific name or epithet (e.g. ''Canis'' sp.). This commonly occurs when authors are confident that some individuals belong to a particular genus but are not sure to which exact species they belong, as is common in paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

.genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

and species are usually printed in italics

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Owing to the influence from calligraphy, italics normally slant slightly to the right. Italics are a way to emphasise key points in a printed tex ...

. However, abbreviations such as "sp." should not be italicised.

Identification codes

With the rise of online databases, codes have been devised to provide identifiers for species that are already defined, including:

* National Center for Biotechnology Information

The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) is part of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM), a branch of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It is approved and funded by the government of the United States. The ...

(NCBI) employs a numeric 'taxid' or ''Taxonomy identifier'', a "stable unique identifier", e.g., the taxid of ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'' is 9606.

* Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) is a collection of databases dealing with genomes, biological pathways, diseases, drugs, and chemical substances. KEGG is utilized for bioinformatics research and education, including data analysis i ...

(KEGG) employs a three- or four-letter code for a limited number of organisms; in this code, for example, ''H. sapiens'' is simply ''hsa''.

* UniProt

UniProt is a freely accessible database of protein sequence and functional information, many entries being derived from genome sequencing projects. It contains a large amount of information about the biological function of proteins derived from ...

employs an "organism mnemonic" of not more than five alphanumeric characters, e.g., ''HUMAN'' for ''H. sapiens''.

* Integrated Taxonomic Information System

The Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) is an American partnership of federal agencies designed to provide consistent and reliable information on the taxonomy of biological species. ITIS was originally formed in 1996 as an interagenc ...

(ITIS) provides a unique number for each species. The LSID for ''Homo sapiens'' is urn:lsid:catalogueoflife.org:taxon:4da6736d-d35f-11e6-9d3f-bc764e092680:col20170225.

Lumping and splitting

The naming of a particular species, including which genus (and higher taxa) it is placed in, is a ''hypothesis'' about the evolutionary relationships and distinguishability of that group of organisms. As further information comes to hand, the hypothesis may be corroborated or refuted. Sometimes, especially in the past when communication was more difficult, taxonomists working in isolation have given two distinct names to individual organisms later identified as the same species. When two species names are discovered to apply to the same species, the older species name is given priority and usually retained, and the newer name considered as a junior synonym, a process called ''synonymy

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

''. Dividing a taxon into multiple, often new, taxa is called ''splitting''. Taxonomists are often referred to as "lumpers" or "splitters" by their colleagues, depending on their personal approach to recognising differences or commonalities between organisms.[ The circumscription of taxa, considered a taxonomic decision at the discretion of cognizant specialists, is not governed by the Codes of Zoological or Botanical Nomenclature.

]

Broad and narrow senses

The nomenclatural codes that guide the naming of species, including the ICZN

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the I ...

for animals and the ICN for plants, do not make rules for defining the boundaries of the species. Research can change the boundaries, also known as circumscription, based on new evidence. Species may then need to be distinguished by the boundary definitions used, and in such cases the names may be qualified with ''sensu stricto

''Sensu'' is a Latin word meaning "in the sense of". It is used in a number of fields including biology, geology, linguistics, semiotics, and law. Commonly it refers to how strictly or loosely an expression is used in describing any particular co ...

'' ("in the narrow sense") to denote usage in the exact meaning given by an author such as the person who named the species, while the antonym

In lexical semantics, opposites are words lying in an inherently incompatible binary relationship. For example, something that is ''long'' entails that it is not ''short''. It is referred to as a 'binary' relationship because there are two members ...

''sensu lato'' ("in the broad sense") denotes a wider usage, for instance including other subspecies. Other abbreviations such as "auct." ("author"), and qualifiers such as "non" ("not") may be used to further clarify the sense in which the specified authors delineated or described the species.[

]

Change

Species are subject to change, whether by evolving into new species,[ exchanging genes with other species,][ merging with other species or by becoming extinct.

]

Speciation

The evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary process by which biological populations evolve to become distinct or reproductively isolated as species is called speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

.Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

was the first to describe the role of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

in speciation in his 1859 book ''The Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

''. Speciation depends on a measure of reproductive isolation

The mechanisms of reproductive isolation are a collection of evolutionary mechanisms, behaviors and physiological processes critical for speciation. They prevent members of different species from producing offspring, or ensure that any offspring ...

, a reduced gene flow. This occurs most easily in allopatric

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

speciation, where populations are separated geographically and can diverge gradually as mutations accumulate. Reproductive isolation is threatened by hybridisation, but this can be selected against once a pair of populations have incompatible allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s of the same gene, as described in the Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller model

The Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller model, also known as Dobzhansky–Muller model, is a model of the evolution of genetic incompatibility, important in understanding the evolution of reproductive isolation during speciation and the role of natural s ...

.

Exchange of genes between species

Horizontal gene transfer between organisms of different species, either through hybridisation,

Horizontal gene transfer between organisms of different species, either through hybridisation, antigenic shift

Antigenic shift is the process by which two or more different strains of a virus, or strains of two or more different viruses, combine to form a new subtype having a mixture of the surface antigens of the two or more original strains. The term is ...

, or reassortment

Reassortment is the mixing of the genetic material of a species into new combinations in different individuals. Several different processes contribute to reassortment, including assortment of chromosomes, and chromosomal crossover. It is particula ...

, is sometimes an important source of genetic variation. Viruses can transfer genes between species. Bacteria can exchange plasmids with bacteria of other species, including some apparently distantly related ones in different phylogenetic domains, making analysis of their relationships difficult, and weakening the concept of a bacterial species.

Extinction

A species is extinct when the last individual of that species dies, but it may be functionally extinct

Functional extinction is the extinction of a species or other taxon such that:

#It disappears from the fossil record, or historic reports of its existence cease;

#The reduced population no longer plays a significant role in ecosystem function; or ...

well before that moment. It is estimated that over 99 percent of all species that ever lived on Earth, some five billion species, are now extinct. Some of these were in mass extinctions

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It ...

such as those at the ends of the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start ...

, Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

, Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

, Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

and Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

periods. Mass extinctions had a variety of causes including volcanic activity

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

, climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

, and changes in oceanic and atmospheric chemistry, and they in turn had major effects on Earth's ecology, atmosphere, land surface and waters.compilospecies A compilospecies is a genetically aggressive species which acquires the heredities of a closely related sympatric species by means of hybridisation and comprehensive introgression. The target species may be incorporated to the point of despeciat ...

".

Practical implications

Biologists and conservationists

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the f ...

need to categorise and identify organisms in the course of their work. Difficulty assigning organisms reliably to a species constitutes a threat to the validity

Validity or Valid may refer to:

Science/mathematics/statistics:

* Validity (logic), a property of a logical argument

* Scientific: