Benjamin Latrobe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe (May 1, 1764 – September 3, 1820) was an Anglo-American neoclassical

architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

who emigrated to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. He was one of the first formally trained, professional architects in the new United States, drawing on influences from his travels in Italy, as well as British and French Neoclassical architects such as Claude Nicolas Ledoux. In his thirties, he emigrated to the new United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

and designed the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

, on "Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, in addition to being a metonym for the United States Congress, is the largest historic residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C., stretching easterly in front of the United States Capitol along wide avenues. It is one of the ...

" in Washington, D.C., as well as the Old Baltimore Cathedral or The Baltimore Basilica, (later renamed the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary). It is the first Cathedral constructed in the United States for any Christian denomination. Latrobe also designed the largest structure in America at the time, the "Merchants' Exchange" in Baltimore. With extensive balconied atriums through the wings and a large central rotunda under a low dome which dominated the city, it was completed in 1820 after five years of work and endured into the early twentieth century.

Latrobe emigrated in 1796, initially settling in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

where he worked on the Virginia State Penitentiary Virginia State Penitentiary was a prison in Richmond, Virginia. Towards the end of its life it was a part of the Virginia Department of Corrections.

First opening in 1800, the prison was completed in 1804; it was built due to a reform movement prec ...

in Richmond. Latrobe then moved to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

where he established his practice. In 1803, he was hired as Surveyor of the Public Buildings of the United States, and spent much of the next fourteen years working on projects in the new national capital of Washington, D.C., (in the newly-laid out Federal capital of the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

) where he served as the second Architect of the Capitol

The Architect of the Capitol (AOC) is the federal agency responsible for the maintenance, operation, development, and preservation of the United States Capitol Complex. It is an agency of the legislative branch of the federal government and i ...

. He also was responsible for the design of the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest, Washington, D.C., NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. preside ...

porticos. Latrobe spent the later years of his life in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Latrobe was born on May 1, 1764, at the Fulneck Moravian Settlement, near Pudsey in the city of

Latrobe was born on May 1, 1764, at the Fulneck Moravian Settlement, near Pudsey in the city of

Latrobe arrived in

Latrobe arrived in

By the time he arrived in Philadelphia, Latrobe's two friends, Scandella and Volney, had left due to concerns regarding the Alien and Sedition Acts, but Latrobe made friends with some of their acquaintances at the

By the time he arrived in Philadelphia, Latrobe's two friends, Scandella and Volney, had left due to concerns regarding the Alien and Sedition Acts, but Latrobe made friends with some of their acquaintances at the

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

.

Latrobe has been called the "father of American architecture". He was the uncle of Charles La Trobe, who was the first Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria in Australia.

Biography

Latrobe was born on May 1, 1764, at the Fulneck Moravian Settlement, near Pudsey in the city of

Latrobe was born on May 1, 1764, at the Fulneck Moravian Settlement, near Pudsey in the city of Leeds

Leeds () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the thi ...

, in the West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

, England. His parents were the Reverend

The Reverend is an style (manner of address), honorific style most often placed before the names of Christian clergy and Minister of religion, ministers. There are sometimes differences in the way the style is used in different countries and c ...

Benjamin Latrobe, a leader of the Moravian Church

, image = AgnusDeiWindow.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, caption = Church emblem featuring the Agnus Dei.Stained glass at the Rights Chapel of Trinity Moravian Church, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States

, main_classification = Proto-Pr ...

who was of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

(French Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

) ancestry, and Anna Margaretta Antes whose father was German and whose maternal line was Dutch. Antes was born in the American colony of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

, but was sent to England by her father, a wealthy landowner, to attend a Moravian school at Fulneck.

Latrobe's father, who was responsible for all Moravian schools and establishments in Britain, had an extensive circle of friends in the higher ranks of society. He stressed the importance of education, scholarship, and the value of social exchange; while Latrobe's mother instilled in her son a curiosity and interest in America. From a young age, Benjamin Henry Latrobe enjoyed drawing landscapes and buildings. He was a brother of Moravian leader and musical composer Christian Ignatius Latrobe.

In 1776, at the age of 12, Latrobe was sent away to the Moravian School at Niesky in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

near the border of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

. At age eighteen, he spent several months traveling around Germany, and then joined the Royal Prussian Army, becoming close friends with a distinguished officer in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

. Latrobe also may have served briefly in the Austrian Imperial Army, and suffered some injuries or illness. After recovering, he embarked on a continental "Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tu ...

", visiting eastern Saxony, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, and other places. Through his education and travels, Latrobe mastered German, French, ancient and modern Greek, and Latin. He had advanced ability in Italian and Spanish and some knowledge of Hebrew. Latrobe was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society in ...

in 1815.

His son, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, II

Benjamin Henry Latrobe II (December 19, 1806 – October 19, 1878) was an American civil engineer, best known for his railway bridges, and a railway executive.

Personal life

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on December 19, 1806, he was th ...

, (sometimes referred to as "Junior"), also worked as a civil engineer. In 1827, he joined the newly organized Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

and designed the longest, most challenging bridge on its initial route: the curving Thomas Viaduct, (the third of four multi-arched "viaduct

A viaduct is a specific type of bridge that consists of a series of arches, piers or columns supporting a long elevated railway or road. Typically a viaduct connects two points of roughly equal elevation, allowing direct overpass across a wide va ...

s").

Another son, John Hazlehurst Boneval Latrobe (1803–1891), was a noted civic leader, lawyer, author, historian, artist, inventor, intellectual, and social activist in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

.

A grandson, Charles Hazlehurst Latrobe

Benjamin Henry Latrobe II (December 19, 1806 – October 19, 1878) was an American civil engineer, best known for his railway bridges, and a railway executive.

Personal life

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on December 19, 1806, he was the ...

(1834–1902), Benjamin Henry Latrobe II's son, a Confederate soldier, also continued the tradition of architect and engineer, building bridges for the city and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

. Latrobe Park in south Baltimore is named for the family, as is Latrobe Park, New Orleans Latrobe or La Trobe may refer to:

People

* Christian Ignatius Latrobe (1758–1836), English clergyman and musician

* Charles La Trobe (1801–1875), first lieutenant-governor of Victoria, Australia, son of C. I. Latrobe

* Benjamin Henry Latrobe ...

, in the French Quarter

The French Quarter, also known as the , is the oldest neighborhood in the city of New Orleans. After New Orleans (french: La Nouvelle-Orléans) was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city developed around the ("Old S ...

. Another grandson, Ferdinand Claiborne Latrobe, was a seven-term mayor of Baltimore.

Travels

England

Latrobe returned to England in 1784, and was apprenticed toJohn Smeaton

John Smeaton (8 June 1724 – 28 October 1792) was a British civil engineer responsible for the design of bridges, canals, harbours and lighthouses. He was also a capable mechanical engineer and an eminent physicist. Smeaton was the firs ...

, an engineer known for designing Eddystone Lighthouse

The Eddystone Lighthouse is a lighthouse that is located on the dangerous Eddystone Rocks, south of Rame Head in Cornwall, England. The rocks are submerged below the surface of the sea and are composed of Precambrian gneiss. View at 1:50000 ...

. Then in 1787 or 1788, he worked in the office of neoclassical architect Samuel Pepys Cockerell for a brief time. In 1790, Latrobe was appointed Surveyor of the Public Offices in London, and established his own private practice in 1791. Latrobe was commissioned in 1792 to design Hammerwood Lodge, near East Grinstead

East Grinstead is a town in West Sussex, England, near the East Sussex, Surrey, and Kent borders, south of London, northeast of Brighton, and northeast of the county town of Chichester. Situated in the extreme northeast of the county, the civ ...

in Sussex, his first independent work, and he designed nearby Ashdown House in 1793. Latrobe was involved in construction of the Basingstoke Canal in Surrey, together with engineers John Smeaton

John Smeaton (8 June 1724 – 28 October 1792) was a British civil engineer responsible for the design of bridges, canals, harbours and lighthouses. He was also a capable mechanical engineer and an eminent physicist. Smeaton was the firs ...

and William Jessop

William Jessop (23 January 1745 – 18 November 1814) was an English civil engineer, best known for his work on canals, harbours and early railways in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early life

Jessop was born in Devonport, Devon, the ...

. In spring 1793, Latrobe was hired to plan improvements to the River Blackwater from Maldon to Beeleigh, so that the port of Maldon could compete with the Chelmer and Blackwater Navigation, which bypassed the town. The project lasted until early 1795, when Parliament denied approval of his plan. Latrobe had problems getting payment for his work on the project, and faced bankruptcy.

In February 1790, Latrobe married Lydia Sellon, and they lived a busy social life in London. The couple had a daughter (Lydia Sellon Latrobe) and a son (Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe

Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe (1793–1817) was an American architect noted for his work in and around New Orleans. He was the son of Benjamin Henry Latrobe by his first wife.

He was educated at St. Mary's College in Baltimore and joined his fathe ...

), before she died giving birth during November 1793. Lydia had inherited her father's wealth, which in turn was to be left to the children through a trust with the children's uncles, but never ended up going to the children. In 1795, Latrobe suffered a breakdown and decided to emigrate to America, departing on November 25 aboard the ''Eliza''.

In America, Latrobe was known for his series of topological and landscape watercolors; the series started with a view of the White Cliffs of the south coast of England viewed from the ''Eliza''. The series was preceded by a watercolor of East Grinstead, dated September 8, 1795.

Virginia

Latrobe arrived in

Latrobe arrived in Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 cen ...

, in mid-March 1796 after a harrowing four-month journey aboard the ship, which was plagued with food shortages under near-starvation conditions. Latrobe initially spent time in Norfolk, where he designed the "William Pennock House," then set out for Richmond in April 1796. Soon after arriving in Virginia, Latrobe became friends with Bushrod Washington, nephew of President George Washington, along with Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

and other notable figures. Through Bushrod Washington, Latrobe was able to pay a visit to Mount Vernon to meet with the president in the summer of 1796.

Latrobe's first major project in the United States was the State Penitentiary in Richmond, commissioned in 1797. The penitentiary included many innovative ideas in penal reform

Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of a penal system, or implement alternatives to incarceration. It also focuses on ensuring the reinstatement of those whose lives are impacted by crimes ...

, then being espoused by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

and various other figures, including cells arranged in a semicircle, that allowed for easy surveillance, as well as improved living conditions for sanitation and ventilation. He also pioneered the use of solitary confinement in the Richmond penitentiary. While in Virginia, Latrobe worked on the Green Spring mansion near Williamsburg

Williamsburg may refer to:

Places

*Colonial Williamsburg, a living-history museum and private foundation in Virginia

*Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood in New York City

*Williamsburg, former name of Kernville (former town), California

*Williams ...

, which had been built by Governor Sir William Berkeley in the seventeenth century but fell into disrepair after the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

. Latrobe created designs for Fort Nelson Fort Nelson may refer to:

Canada

*Fort Nelson, British Columbia, a town

*Fort Nelson River, British Columbia

* Fort Nelson (Manitoba) (1670–1713), an early fur trading post at the mouth of the Nelson River and the first headquarters of the Hudson ...

in Virginia in 1798. He also made drawings for a number of houses that were not built, including the "Mill Hill" plantation house near Richmond.

After spending a year in Virginia, the novelty of being in a new place wore off, and Latrobe was lonely and restless in Virginia. Giambattista Scandella Giambattista Scandella (1770–1798) was an Italian physician and scientist who emigrated to the United States in 1796. Scandella studied medicine at the University of Padua, and then went into medical practice in Venice in 1786. He also conducted ...

, a friend, suggested Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

as an ideal location for him. In April 1798, Latrobe visited Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

for the first time, meeting with Bank of Pennsylvania president Samuel J. Fox, and presented to him a design for a new bank building. At the time, the political climate in Philadelphia was quite different than Virginia, with a strong division between the Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of d ...

and Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans, along with anti-French sentiment, thus the city was not entirely welcoming for Latrobe. On his way to Philadelphia, Latrobe passed through the national capital city of Washington, D.C., then under construction (congress and the president would not arrive until the year 1800), where he met with the first architect of the capitol, William Thornton, and viewed the United States Capitol for the first time. He stopped by Washington again on his way back to Richmond. Latrobe remained in Richmond, Virginia, until November 1798, when his design was selected for the Bank of Pennsylvania. He moved to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, so that he could supervise the construction, although he continued to do occasional projects for clients in Virginia.

Philadelphia

By the time he arrived in Philadelphia, Latrobe's two friends, Scandella and Volney, had left due to concerns regarding the Alien and Sedition Acts, but Latrobe made friends with some of their acquaintances at the

By the time he arrived in Philadelphia, Latrobe's two friends, Scandella and Volney, had left due to concerns regarding the Alien and Sedition Acts, but Latrobe made friends with some of their acquaintances at the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communi ...

. Latrobe submitted several papers to the society, on his geology and natural history observations, and became a member of the society in 1799. With his charming personality, Latrobe quickly made other friends among the influential financial and business families in Philadelphia, and became close friends with Nicholas Roosevelt, a talented steam-engine builder who would help Latrobe in his waterworks projects.

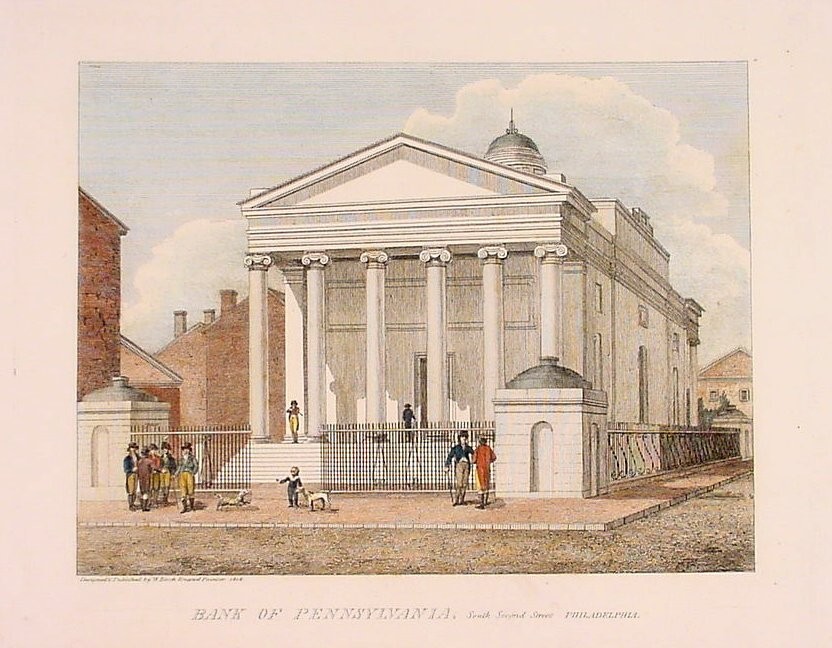

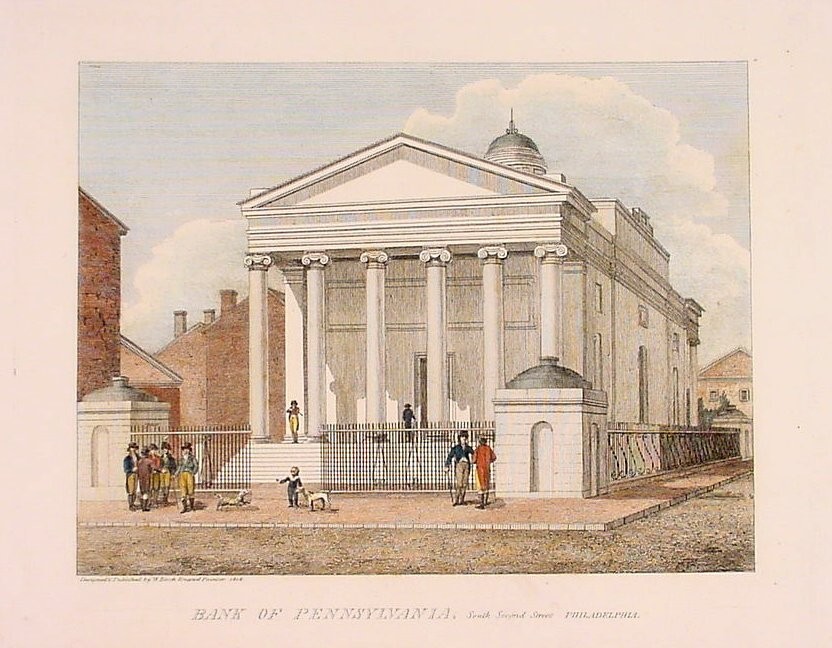

Latrobe's first major project in Philadelphia was to design the Bank of Pennsylvania, which was the first example of Greek Revival

The Greek Revival was an architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United States and Canada, but a ...

architecture in the United States. It was demolished in 1870. This commission is what convinced him to set up his practice in Philadelphia, where he developed his reputation.

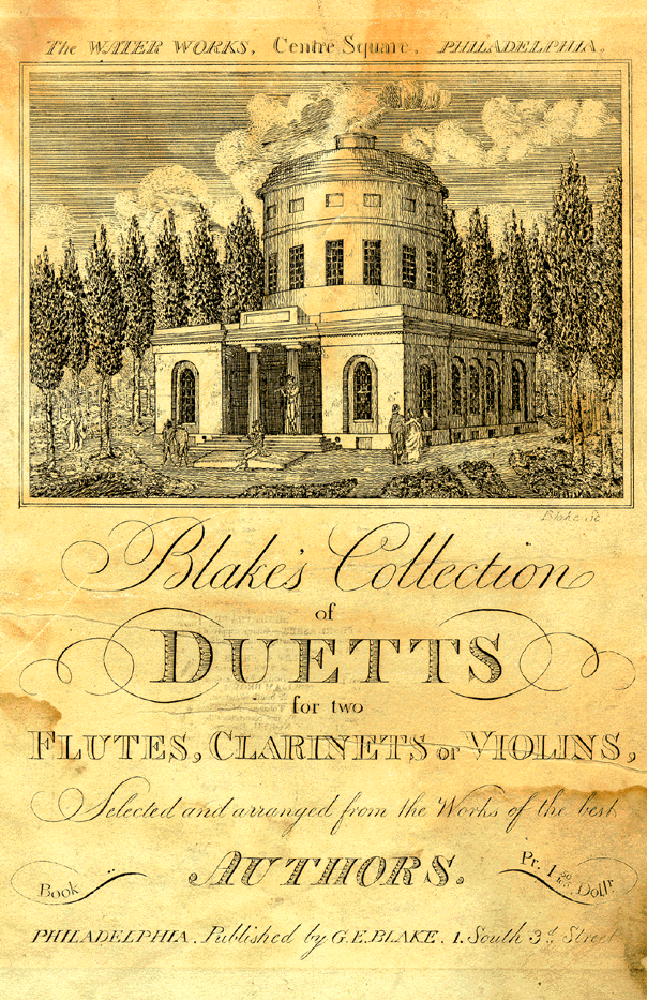

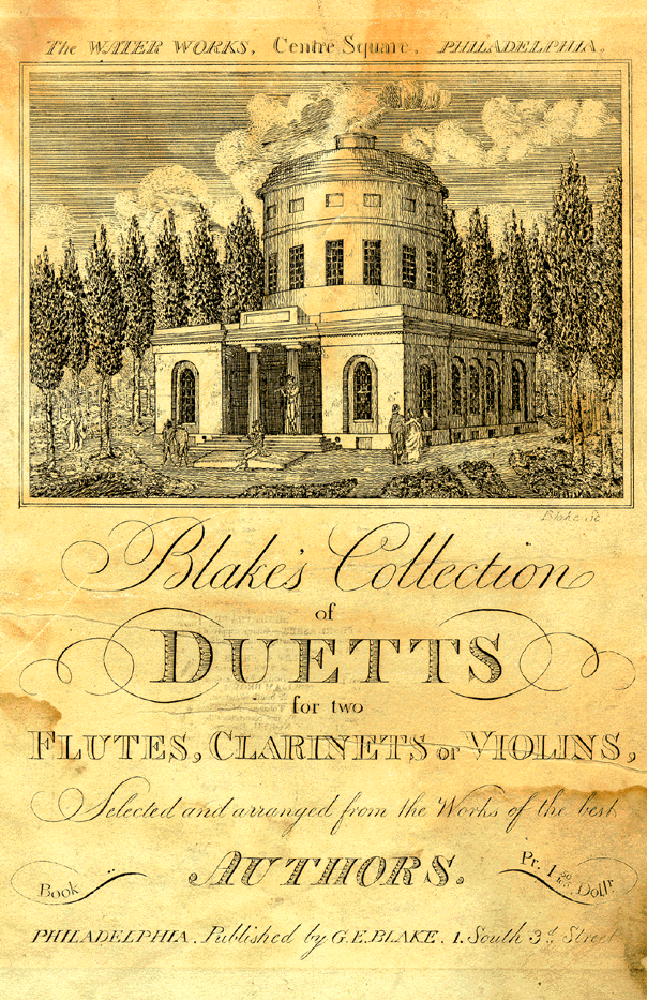

Latrobe also was hired to design the Center Square Water Works in Philadelphia. The Pump House, located on the common at Broad and Market Streets (now the site of Philadelphia City Hall

Philadelphia City Hall is the seat of the municipal government of the City of Philadelphia. Built in the ornate Second Empire style, City Hall houses the chambers of the Philadelphia City Council and the offices of the Mayor of Philadelphia. ...

), was designed by Latrobe in a Greek Revival style. It drew water from the Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River ( , ) is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania. The river was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal, and several of its tributaries drain major parts of Pennsylvania's Coal Region. It ...

, a mile away, and contained two steam engines that pumped it into wooden tanks in its tower. Gravity then fed the water by wooden mains into houses and businesses. Following his work on the Philadelphia water works project, Latrobe worked as an engineer of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal

The Chesapeake & Delaware Canal (C&D Canal) is a -long, -wide and -deep ship canal that connects the Delaware River with the Chesapeake Bay in the states of Delaware and Maryland in the United States.

In the mid‑17th century, mapmaker Augus ...

.

In addition to Greek Revival designs, Latrobe also used Gothic Revival designs in many of his works, including the 1799 design of Sedgeley

Sedgeley was a mansion, designed by the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, and built on the east banks of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, USA, in 1799–1802.

Design and construction

The land where the house was located was originally own ...

, a country mansion in Philadelphia. The Gothic Revival style was used in Latrobe's design of the Philadelphia Bank building as well, which was built in 1807 and demolished in 1836. As a young architect, Robert Mills worked as an assistant with Latrobe from 1803 until 1808 when he set up his own practice.

While in Philadelphia, Latrobe married Mary Elizabeth Hazlehurst (1771–1841), in 1800. The couple had several children together.

Washington, D.C.

In the United States, Latrobe quickly achieved eminence as the first professional architect working in the country. Latrobe was a friend ofThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

, influencing Jefferson's design for the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with College admission ...

. Latrobe also knew James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe wa ...

, as well as New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Barthelemy Lafon, was Aaron Burr's preferred architect, and he trained architect William Strickland.

In 1803, Jefferson hired Latrobe as Surveyor of the Public Buildings of the United States, and to work as superintendent of construction of the  Although Latrobe's major work was overseeing construction of the

Although Latrobe's major work was overseeing construction of the  Benjamin Latrobe was responsible for several other projects located around Lafayette Square, including St. John's Episcopal Church, Decatur House, and the

Benjamin Latrobe was responsible for several other projects located around Lafayette Square, including St. John's Episcopal Church, Decatur House, and the

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

. As construction of the capitol was already underway, Latrobe was tasked to work with William Thornton's plans, which Latrobe criticized. In an 1803 letter to Vice President Aaron Burr, he characterized the plans and work done as "faulty construction". Nonetheless, President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

insisted that Latrobe follow Thornton's design for the capitol.

Although Latrobe's major work was overseeing construction of the

Although Latrobe's major work was overseeing construction of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

, he also was responsible for numerous other projects in Washington. In 1804, became chief engineer in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. As chief surveyor, Latrobe was responsible for the Washington Canal. Latrobe faced bureaucratic hurdles in moving forward with the canal, with the directors of the company rejecting his request for stone locks. Instead, the canal was built with wooden locks, which were subsequently destroyed in a heavy storm in 1811. Latrobe also designed the main gate of the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administra ...

. Latrobe worked on other transportation projects in Washington, D.C., including the Washington and Alexandria Turnpike, which connected Washington with Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, as well as a road connecting with Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in and the county seat of Frederick County, Maryland. It is part of the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area, Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area. Frederick has long been an important crossroads, located at the inter ...

, and a third road, the Columbia Turnpike going through Bladensburg to Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. Latrobe also provided consulting on the construction of the Washington Bridge across the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia, Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Datas ...

in a way that would not impede navigation and commerce to Georgetown.

Benjamin Latrobe was responsible for several other projects located around Lafayette Square, including St. John's Episcopal Church, Decatur House, and the

Benjamin Latrobe was responsible for several other projects located around Lafayette Square, including St. John's Episcopal Church, Decatur House, and the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest, Washington, D.C., NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. preside ...

porticos. Private homes designed by Latrobe include commissions by John P. Van Ness and Peter Casanove.

In June 1812, construction of the Capitol came to a halt with the outbreak of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It ...

and the failure of the First Bank of the United States

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

* World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

. During the war, Latrobe relocated to Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, and returned to Washington in 1815, as Architect of the Capitol

The Architect of the Capitol (AOC) is the federal agency responsible for the maintenance, operation, development, and preservation of the United States Capitol Complex. It is an agency of the legislative branch of the federal government and i ...

, charged with responsibility of rebuilding the capitol after it was destroyed in the war. Latrobe was given more freedom in rebuilding the capitol, to apply his own design elements for the interior. Through much of Latrobe's time in Washington, he remained involved with his private practice to some extent and with other projects in Philadelphia and elsewhere. His clerk of works, John Lenthal, often urged Latrobe to spend more time in Washington.

By 1817, Latrobe had provided President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe wa ...

with complete drawings for the entire building. He resigned as Architect of the Capitol

The Architect of the Capitol (AOC) is the federal agency responsible for the maintenance, operation, development, and preservation of the United States Capitol Complex. It is an agency of the legislative branch of the federal government and i ...

on November 20, 1817, and without this major commission, Latrobe faced difficulties and was forced into bankruptcy. Latrobe left Washington, for Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

in January 1818.

Latrobe left Washington with pessimism, with the city's design contradicting many of his ideals. Latrobe disliked the Baroque-style plan for the city, and other aspects of L'Enfant's plan, and resented having to conform to Thornton's plans for the Capitol Building. One of the greatest problems with the overall city plan, in the view of Latrobe, was its vast interior distances, and Latrobe considered the Washington Canal as a key factor that, if successful, could help alleviate this issue. Latrobe also had concerns about the city's economic potential, and argued for constructing a road connecting Washington with Frederick to the northwest to enhance economic commerce through Washington.

New Orleans

Latrobe saw great potential for growth in New Orleans, situated at the mouth of theMississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it ...

, with the advent of the steamboat and great interest in steamboat technology. Latrobe's first project in New Orleans was the first New Orleans United States Customs building, constructed in 1807.

In 1810 Latrobe sent his son, Henry Sellon "Boneval" Latrobe, to the city to present a plan for a waterworks system to the New Orleans city council. Latrobe's plan for the waterworks system was based on that of Philadelphia, which he earlier designed. The system in Philadelphia was created as a response to yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

epidemics affecting the city. Latrobe's system used steam pumps to move water from the Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River ( , ) is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania. The river was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal, and several of its tributaries drain major parts of Pennsylvania's Coal Region. It ...

to a reservoir, located upstream; so that gravity could be used to transmit the water from there to residents in the city. The New Orleans waterworks project also was designed to desalinate water, using steam-powered pumps. While in New Orleans, Latrobe's son participated in the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Fren ...

against British forces in 1815, and took on other projects including building a lighthouse, a new Charity Hospital, and the French Opera House.

New Orleans agreed to commission the waterworks project in 1811, although Latrobe was not ready to take on the project immediately and faced financial problems in securing enough investors for the project. His work on the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

was completed shortly before the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It ...

started, ending his source of steady income. During the war Latrobe unsuccessfully tried several wartime schemes to make money, including some steamboat projects. In 1814, Latrobe partnered with Robert Fulton in a steamship venture based at Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

. While in Pittsburgh, Latrobe designed and built a theater for the Circus of Pepin and Breschard. After the U. S. Capitol and White House were burned by the British Army, Latrobe remained in Washington to help with rebuilding, and Latrobe's son took on much of the work for the New Orleans waterworks project.

Latrobe faced further delays trying to get an engine built for the waterworks, which he finally accomplished in 1819. The process of designing and constructing the waterworks system in New Orleans spanned eleven years. In addition to this project, Latrobe designed the central tower of the St. Louis Cathedral, which was his last architectural project.

Latrobe died September 3, 1820, from yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

, while working in Louisiana. He was buried in the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

section of the Saint Louis Cemetery in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

While studying in Germany, Latrobe was mentored by Baron Karl von Schachmann, a classical scholar interested in art and collecting. Around 1783, Latrobe made the decision to become an architect, a decision influenced by the baron. While Latrobe was in Germany, a new architectural movement, led by Carl Gotthard Langhans and others, was emerging with return to more Classical or Vitruvian designs.

In 1784, Latrobe set off on a

While studying in Germany, Latrobe was mentored by Baron Karl von Schachmann, a classical scholar interested in art and collecting. Around 1783, Latrobe made the decision to become an architect, a decision influenced by the baron. While Latrobe was in Germany, a new architectural movement, led by Carl Gotthard Langhans and others, was emerging with return to more Classical or Vitruvian designs.

In 1784, Latrobe set off on a

When Latrobe began private practice in England, his first projects were alterations to existing houses, designing Hammerwood Park, and designing

When Latrobe began private practice in England, his first projects were alterations to existing houses, designing Hammerwood Park, and designing

Fine Arts Library Image Collection

– University of Pennsylvania

* ttps://www.pbs.org/benjaminlatrobe/ Benjamin Latrobe: America's First Architecton PBS

Benjamin Henry LaTrobe Sketches of Fishes, 1796–1797, 1882

from the

Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe

Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe (1793–1817) was an American architect noted for his work in and around New Orleans. He was the son of Benjamin Henry Latrobe by his first wife.

He was educated at St. Mary's College in Baltimore and joined his fathe ...

(1792–1817), had been buried three years earlier, having also succumbed to yellow fever.

Architecture

Influences

Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tu ...

around Europe, visiting Paris where the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was ...

, a church dedicated to St. Genevieve

Genevieve (french: link=no, Sainte Geneviève; la, Sancta Genovefa, Genoveva; 419/422 AD –

502/512 AD) is the patroness saint of Paris in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Her feast is on 3 January.

Genevieve was born in Nanterre and ...

, was nearing completion. The Panthéon in Paris, designed by Jacques Germain Soufflot and Jean-Baptiste Rondelet, represented an early example of Neoclassicism. At that time, Claude Nicolas Ledoux was designing numerous houses in France, in Neoclassical style. Latrobe also visited Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, where he was impressed by the Roman Pantheon and other ancient structures with Greek influence. Influential architects in Britain, at the time when Latrobe returned in 1784, adhered to a number of different styles. Sir William Chambers was at the forefront, designing in Palladianism style, while Chambers' rival, Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him. With his ...

's designs had Roman influence, in a style known as Adam style. Latrobe was not interested in either the Palladian nor Adam style, but Neoclassicalism also was being introduced to Great Britain at the time by George Dance the Younger

George Dance the Younger RA (1 April 1741 – 14 January 1825) was an English architect and surveyor as well as a portraitist.

The fifth and youngest son of the architect George Dance the Elder, he came from a family of architects, artists ...

. Other British architects, including John Soane and Henry Holland, also designed in the Neoclassical style while Latrobe was in London.

During his European tour, Latrobe gathered ideas on how American cities should be designed. He suggested city block

A city block, residential block, urban block, or simply block is a central element of urban planning and urban design.

A city block is the smallest group of buildings that is surrounded by streets, not counting any type of thoroughfare within ...

s be laid out as thin rectangles, with the long side of the blocks oriented east-west so that as many houses as possible could face south. For a city to succeed, he thought it needed to be established only in places with good prospects for commerce and industrial growth, and with a good water supply.

Public health was another key consideration of Latrobe, who believed that the eastern shores of rivers were unhealthy, due to prevailing direction of the wind, and recommended cities be built on the western shores of rivers.

Greek Revival in America

Latrobe brought from England influences of British Neoclassicism, and was able to combine it with styles introduced by Thomas Jefferson, to devise an American Greek Revival style. John Summerson described the Bank of Pennsylvania, as an example of how Latrobe "married English Neo-Classicism to Jeffersonian Neo-Classicism nd... from that moment, the classical revival in America took on a national form". The American form of Greek Revival architecture that Latrobe developed became associated with political ideals ofdemocracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

—a meaning that was less apparent in Britain. The direct link between the Greek Revival architecture and American democracy has been disputed by recent scholars such as W. Barksdale Maynard, who sees the Greek Revival as an international phenomenon.

Selected works

Houses

Ashdown House, East Sussex

Ashdown House is a country house near Forest Row, in East Sussex, England. It is a listed building, Grade II* listed building. One of the first houses in England to be built in the Greek Revival architectural style, it was built in 1793 as the ...

. Alterations completed early in his career may have included Tanton Hall, Sheffield Park, Frimley, and Teston Hall, although these homes have since been altered and it is difficult now to isolate Latrobe's work in the current designs. His designs were simpler than was typical at the time, and had influences of Robert Adam. Features in his designs often included as part of the front portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many c ...

s, Greek ionic columns, as used in Ashdown House, or doric columns, seen in Hammerwood Park.

The book, ''The Domestic Architecture of Benjamin Henry Latrobe'', lists buildings he designed in England, including Grade II* listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

Alderbury House (late 1800s) in Wiltshire. This structure had previously been misattributed to James Wyatt. It has been described as "one of Wiltshire’s most elegant Georgian country houses".

Latrobe continued to design houses after he emigrated to the United States, mostly using Greek Revival designs. Four houses still stand that Latrobe designed: the Decatur House in Washington, D.C.; Adena in Chillicothe, Ohio; the Pope Villa in Lexington, Kentucky; and the Sedgeley Porter's house in Philadelphia. As one of Latrobe's most avant-garde designs, the Pope Villa has national significance for its unique design. He also introduced Gothic Revival architecture

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

to the United States with the design of Sedgeley

Sedgeley was a mansion, designed by the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, and built on the east banks of the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, USA, in 1799–1802.

Design and construction

The land where the house was located was originally own ...

. The mansion was built in 1799 and demolished in 1857; however, the stone Porter's house at Sedgeley remains as his only extant building in Philadelphia. A theme seen in many of Latrobe's designs is plans with squarish-dimensions and a central, multi-story hall with a cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, most often dome-like, tall structure on top of a building. Often used to provide a lookout or to admit light and air, it usually crowns a larger roof or dome.

The word derives, via Italian, fr ...

to provide lighting, which was contrary to the popular trend of the time of building houses with long narrow plans.

Personal life

* First wife: Lydia Sellon (1760-1793) ** Lydia Sellon Mary Latrobe (1791-1878) m. Nicholas James Roosevelt **Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe

Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe (1793–1817) was an American architect noted for his work in and around New Orleans. He was the son of Benjamin Henry Latrobe by his first wife.

He was educated at St. Mary's College in Baltimore and joined his fathe ...

(1792-1817)

** Unnamed (1793)

* Second wife: Mary Elizabeth Hazlehurst (1771-1841)

** Juliana Latrobe (1801)

** John Hazlehurst Boneval Latrobe (1803-1891)

** Juliana Elizabeth Boneval Latrobe (1804-1890)

** Mary Agnes Latrobe (1805-1806)

** Benjamin Henry Latrobe Jr.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe II (December 19, 1806 – October 19, 1878) was an American civil engineer, best known for his railway bridges, and a railway executive.

Personal life

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on December 19, 1806, he was th ...

(1806-1878)

** Louisa Latrobe (1808)

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Klotter, James C., and Daniel Rowland, eds. ''Bluegrass Renaissance: The History and Culture of Central Kentucky, 1792–1852'' (University Press of Kentucky; 2012) 371 pages; emphasis on Benjamin Henry Latrobe and "neoclassical" Lexington * * * * * * * * *External links

Fine Arts Library Image Collection

– University of Pennsylvania

* ttps://www.pbs.org/benjaminlatrobe/ Benjamin Latrobe: America's First Architecton PBS

Benjamin Henry LaTrobe Sketches of Fishes, 1796–1797, 1882

from the

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an institutional archives and library system comprising 21 branch libraries serving the various Smithsonian Institution museums and research centers. The Libraries and Archives serve Smithsonian Institutio ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Latrobe, Benjamin Henry

American neoclassical architects

British neoclassical architects

Architects of the Capitol

1764 births

1820 deaths

American ecclesiastical architects

Architects of cathedrals

Gothic Revival architects

English ecclesiastical architects

Federalist architects

Greek Revival architects

American surveyors

English surveyors

Members of the American Philosophical Society

Members of the American Antiquarian Society

English emigrants to the United States

English people of the Moravian Church

People educated at Fulneck School

People from Pudsey

Prussian Army personnel

Burials in Louisiana

Deaths from yellow fever

Infectious disease deaths in Louisiana

Latrobe, Pennsylvania

18th-century American people

18th-century English architects

Architects from Leeds

Latrobe family