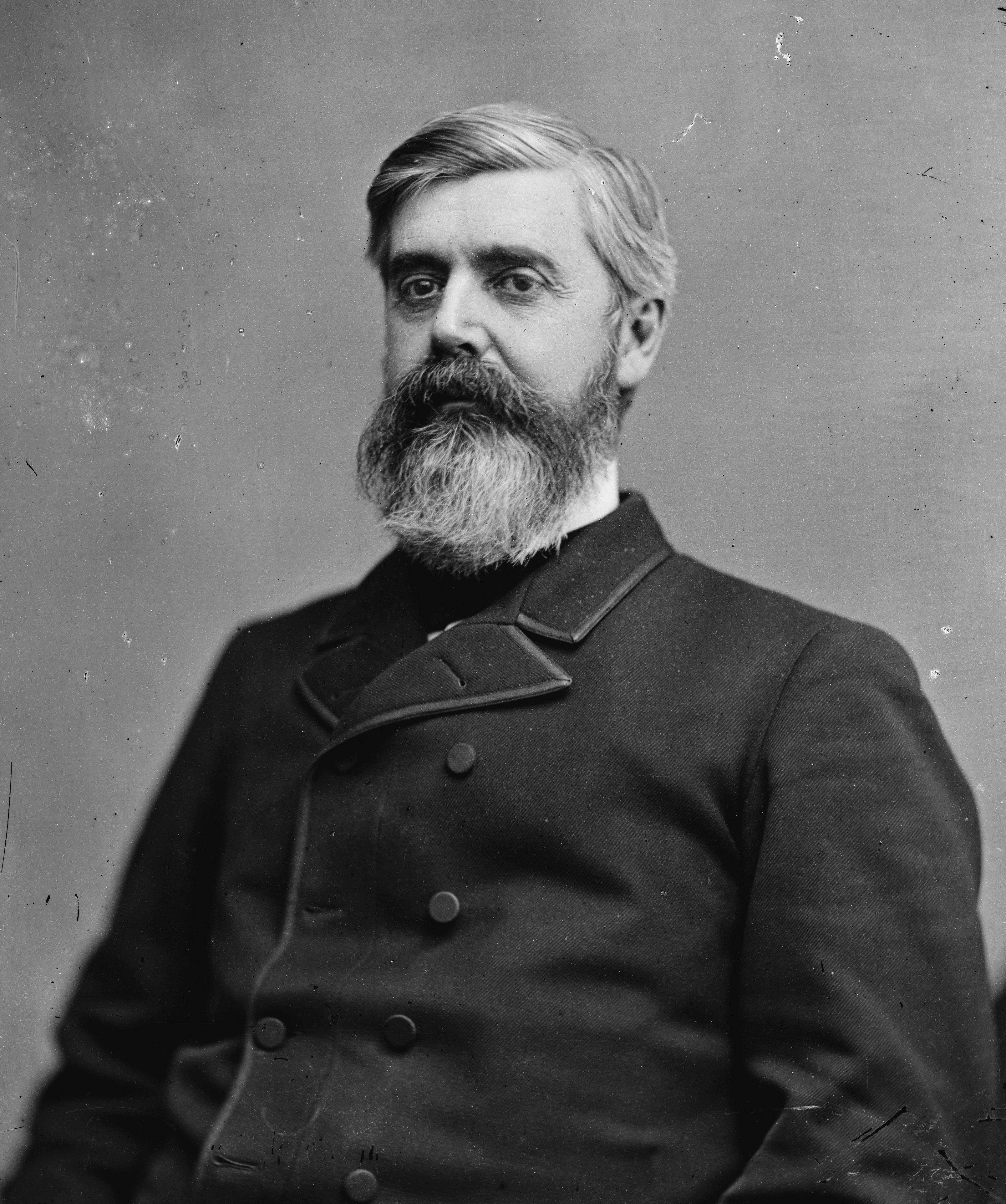

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the

Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president,

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

, and a great-grandson of

Benjamin Harrison V, a

Founding Father. A Union Army veteran and a Republican, he defeated incumbent

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

to win the presidency in 1888.

Harrison was born on a farm by the

Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

and graduated from

Miami University

Miami University (informally Miami of Ohio or simply Miami) is a public university, public research university in Oxford, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1809, it is the second-oldest List of colleges and universities in Ohio, university in Ohi ...

in

Oxford, Ohio

Oxford is a city in northwestern Butler County, Ohio, United States. The population was 23,035 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. A college town, Oxford was founded as a home for Miami University and lies in the southwestern portion ...

. After moving to

Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

, he established himself as a prominent local attorney, Presbyterian church leader, and politician in

Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

. During the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, he served in the

Union Army as a

colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

, and was confirmed by the

U.S. Senate as a

brevet brigadier general of volunteers in 1865. Harrison unsuccessfully ran for

governor of Indiana in 1876. The

Indiana General Assembly elected Harrison to a six-year term in the Senate, where he served from 1881 to 1887.

A

Republican, Harrison was elected to the presidency in

1888, defeating the

Democratic incumbent Grover Cleveland in the

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

while losing the popular vote. Hallmarks of Harrison's administration were unprecedented economic legislation, including the

McKinley Tariff, which imposed historic protective trade rates, and the

Sherman Antitrust Act. Harrison also facilitated the creation of the

national forest reserves through an amendment to the

Land Revision Act of 1891. During his administration six western states were admitted to the Union. In addition, Harrison substantially strengthened and modernized the

U.S. Navy and conducted an active foreign policy, but his proposals to secure federal education funding as well as voting rights enforcement for African Americans were unsuccessful.

Due in large part to surplus revenues from the tariffs, federal spending reached $1 billion for the first time during his term. The spending issue in part led to the Republicans' defeat in the

1890 midterm elections. Cleveland defeated Harrison for reelection in

1892, due to the growing unpopularity of high tariffs and high federal spending. Harrison returned to private life and his law practice in Indianapolis. In 1899, he represented

Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

in its

British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

boundary dispute with the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Harrison traveled to the court in Paris as part of the case and after a brief stay returned to Indianapolis. He died at his home in Indianapolis in 1901 of complications from

influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

. Many have praised Harrison's commitment to African Americans' voting rights, his work ethic, and his integrity, but scholars and historians generally

rank him as an average president, due to the uneventful nature of his term.

[ "Because of his lack of personal passion and the failure of anything truly eventful, such as a major war, during his administration, Harrison, along with every other President from the post-Reconstruction era to 1900, has been assigned to the rankings of mediocrity. He has been remembered as an average President, not among the best but certainly not among the worst."] He was defeated by Cleveland in 1892, becoming the first president to be succeeded in office by his predecessor.

Family and education

Harrison was born on August 20, 1833, in

North Bend, Ohio, the second of Elizabeth Ramsey (Irwin) and

John Scott Harrison's 10 children. His ancestors included immigrant Benjamin Harrison, who arrived in

Jamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent British colonization of the Americas, English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James River, about southwest of present-day Willia ...

, c. 1630 from

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. Harrison was of entirely English ancestry, all of his ancestors having emigrated to America during the early colonial period.

Harrison was a grandson of U.S. President

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

and a great-grandson of

Benjamin Harrison V, a Virginia planter who signed the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

and succeeded

Thomas Nelson Jr. as

governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the head of government of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. The Governor (United States), governor is head of the Government_of_Virginia#Executive_branch, executive branch ...

.

Harrison was seven years old when his grandfather was elected U.S. president, but he did not attend

the inauguration. His family was distinguished, but his parents were not wealthy. John Scott Harrison, a two-term

U.S. congressman from

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, spent much of his farm income on his children's education. Despite the family's modest resources, Harrison's boyhood was enjoyable, much of it spent outdoors fishing or hunting.

Harrison's early schooling took place in a log cabin near his home, but his parents later arranged for a tutor to help him with college preparatory studies. Fourteen-year-old Benjamin and his older brother, Irwin, enrolled in

Farmer's College near

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Ohio, in 1847. He attended the college for two years and while there met his future wife,

Caroline "Carrie" Lavinia Scott. She was a daughter of

John Witherspoon Scott, who was the school's science professor and also a Presbyterian minister.

Harrison transferred to

Miami University

Miami University (informally Miami of Ohio or simply Miami) is a public university, public research university in Oxford, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1809, it is the second-oldest List of colleges and universities in Ohio, university in Ohi ...

in

Oxford, Ohio

Oxford is a city in northwestern Butler County, Ohio, United States. The population was 23,035 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. A college town, Oxford was founded as a home for Miami University and lies in the southwestern portion ...

, in 1850, and graduated in 1852. He joined the

Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta (), commonly known as Phi Delt, is an international secret and social Fraternities and sororities in North America, fraternity founded in 1848, and currently headquartered, at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Phi Delta Theta, alo ...

fraternity, which he used as a network for much of his life. He was also a member of

Delta Chi

Delta Chi () is an international collegiate social fraternity. It was formed in 1890 at Cornell University as a professional fraternity for law students, becoming a social fraternity in 1922. In 1929. Delta Chi became one of the first internat ...

, a law fraternity that permitted dual membership.

Classmates included

John Alexander Anderson, who became a six-term U.S. congressman, and

Whitelaw Reid, Harrison's vice presidential running mate in 1892. At Miami, Harrison was strongly influenced by history and political economy professor

Robert Hamilton Bishop. He also joined a

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

church at college and, like his mother, became a lifelong Presbyterian.

Marriage and early career

After his college graduation in 1852, Harrison studied law with Judge

Bellamy Storer of

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, but before he completed his studies, he returned to Oxford, Ohio, to marry Caroline Scott on October 20, 1853. Caroline's father, a Presbyterian minister, performed the ceremony. The Harrisons had two children,

Russell Benjamin Harrison and

Mary "Mamie" Scott Harrison.

Harrison and his wife returned to live at The Point, his father's farm in southwestern Ohio, while he finished his law studies. Harrison was admitted to the Ohio bar in early 1854, the same year he sold property he had inherited after the death of an aunt for $800 (), and used the funds to move with Caroline to

Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

,

Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

. Harrison began practicing law in the office of John H. Ray in 1854 and became a

crier

A town crier, also called a bellman, is an officer of a royal court or public authority who makes public pronouncements as required.

Duties and functions

The town crier was used to make public announcements in the streets. Criers often dre ...

for the federal court in Indianapolis, for which he was paid $2.50 per day. He also served as a Commissioner for the

U.S. Court of Claims. Harrison became a founding member and first president of both the University Club, a private

gentlemen's club

A gentlemen's club is a private social club of a type originally established by males from Britain's upper classes starting in the 17th century.

Many countries outside Britain have prominent gentlemen's clubs, mostly those associated with the ...

in Indianapolis, and the Phi Delta Theta Alumni Club. Harrison and his wife became members and assumed leadership positions at Indianapolis's First Presbyterian Church.

Having grown up in a

Whig household, Harrison initially favored that party's politics, and joined the

Republican Party shortly after its formation in 1856 and campaigned on behalf of Republican presidential candidate

John C. Frémont. In 1857 Harrison was elected Indianapolis city attorney, a position that paid an annual salary of $400 ().

In 1858, Harrison entered into a law partnership with William Wallace to form the law office of Wallace and Harrison. In 1860, he was elected

reporter

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

of the

Indiana Supreme Court. Harrison was an active supporter of the Republican Party's platform and served as Republican State Committee's secretary. After Wallace, his law partner, was elected county clerk in 1860, Harrison established a new firm with William Fishback, Fishback and Harrison. The new partners worked together until Harrison entered the

Union Army after the start of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

Civil War

In 1862,

President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

issued a call for more recruits for the Union Army; Harrison wanted to enlist, but worried about how to support his young family. While visiting Governor

Oliver Morton, Harrison found him distressed over the shortage of men answering the latest call. Harrison told the governor, "If I can be of any service, I will go."

Morton asked Harrison if he could help recruit a regiment, although he would not ask him to serve. Harrison recruited throughout northern Indiana to raise a regiment. Morton offered him the command, but Harrison declined, as he had no military experience. He was initially commissioned as a captain and company commander on July 22, 1862. Morton commissioned Harrison as a colonel on August 7, 1862, and the newly formed

70th Indiana was mustered into federal service on August 12, 1862. Once mustered, the regiment left Indiana to join the Union Army at Louisville, Kentucky.

Atlanta campaign

For much of its first two years, the 70th Indiana performed reconnaissance duty and guarded railroads in

Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

and

Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

. In May 1864, Harrison and his regiment joined General

William T. Sherman

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

's

Atlanta Campaign in the

Army of the Cumberland and moved to the front lines. On January 2, 1864, Harrison was promoted to command the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division of the

XX Corps. He commanded the brigade at the battles of

Resaca,

Cassville,

New Hope Church, Lost Mountain,

Kennesaw Mountain,

Marietta,

Peachtree Creek, and

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

. When Sherman's main force began its

March to the Sea, Harrison's brigade was transferred to the District of Etowah and participated in the

Battle of Nashville. While encamped near Nashville, during a particularly cold winter, Harrison prepared coffee and brought it to his freezing men at night; his constant catchphrase as he took lead of his men was: "Come on, boys!" Harrison earned a reputation as a strong leader and an officer who did not abandon his soldiers in battle.

Resaca

At the Battle of Resaca on May 15, 1864, Harrison faced Confederate Captain

Max Van Den Corput's artillery battery, which occupied a position "some eighty yards in front of the main Confederate lines".

Sherman, renewing his assault on the center of the Confederate lines begun the previous day, was halted by Corput's four-gun, parapet-protected artillery battery; the battery was well placed to bedevil the Union ranks, and became "the center of a furious struggle".

Corput's artillery redoubt was highly fortified "with three infantry regiments in...rifle pits and four more regiments in the main trenches".

Leading the

70th Indiana Infantry Regiment, Harrison massed his troops in a ravine opposite Corput's position, along with the rest of Brigadier General

William Thomas Ward's brigade.

Harrison and his regiment, leading the assault, then emerged from the ravine, advanced over the artillery parapet, overcame the Confederate gunners, and eliminated the threat. The battery was captured by hand-to-hand combat, and intense combat continued throughout the afternoon.

Harrison's unit, now exposed, found itself immediately subject to intense gunfire from the main Confederate ranks and was forced to take cover.

Although no longer in Confederate hands, Corput's four 12-pound Napoleon cannons

sat in a "no man's land" until nightfall, when Union soldiers "dug through the parapet, slipped ropes around the four cannons, and dragged them back to

heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

lines".

Peachtree Creek

During the Battle of Peachtree Creek, on July 20, 1864, Harrison commanded his brigade against General

W. S. Featherston's Mississippi Brigade, stopping the latter's "fierce assault" over Collier Road. At Peachtree Creek, Harrison's brigade comprised the

102nd,

105th, and

129th Illinois Infantry Regiments, the

79th Ohio Infantry Regiment, and his 70th Indiana Regiment; his brigade deployed in about the center of the Union line, engaging Major General

William Wing Loring's Mississippi division and Alabama troops from General

Alexander Stewart's corps. In his report after the battle, Harrison wrote that "at one time during the fight", with his ammunition dangerously depleted, he sent his acting assistant inspector-general Captain Scott and others to cut "cartridge-boxes from the rebel dead within our lines" and distribute them to his soldiers. According to Harrison's report, the losses from his brigade were "very slight" compared with those of Confederate forces. He thought this was because of battlefield topography, writing: "I believe, that the enemy, having the higher ground, fired too high." Harrison later supported the creation of an Atlanta National Military Park, which would have included "substantial portions" of the Peachtree battlefield, writing in 1900: "The military incidents connected with the investment and ultimate capture of Atlanta are certainly worthy of commemoration and I should be glad to see the project succeed."

Surrender of Atlanta and promotion

After the conclusion of the Atlanta Campaign on September 2, 1864, Harrison was among the initial Union forces to enter the surrendered city of Atlanta; General Sherman opined that Harrison served with "foresight, discipline and a fighting spirit".

After the Atlanta Campaign, Harrison reported to Governor Morton in Indiana for special duty, and while there he campaigned for the position of Indiana's Supreme Court Reporter and for President Lincoln's reelection; after the election he left for Georgia to join Sherman's

March to the Sea, but instead was "given command of the 1st Brigade at Nashville".

Harrison led the brigade at the

Battle of Nashville in December, in a "decisive" action against the forces of General

John Bell Hood. Notwithstanding his memorable military achievements and the praise he received for them, Harrison held a dim view of war. According to historian Allan B. Spetter, he thought "war was a dirty business that no decent man would find pleasurable".

In 1888, the year he won the presidency, Harrison declared: "We Americans have no commission from God to police the world."

Several weeks after the Battle of Nashville, Harrison "received orders to rejoin the 70th Indiana at Savannah, Georgia, after a brief furlough in Indianapolis", but he caught scarlet fever and was delayed for a month, and then spent "several months training replacement troops in South Carolina".

On January 23, 1865, Lincoln nominated Harrison to the grade of

brevet brigadier general of volunteers, to rank from that date, and the Senate confirmed the nomination on February 14, 1865. Harrison was promoted because of his success at the battles of Resaca and Peachtree Creek. He finally returned to his old regiment the same day that news of Lincoln's assassination was received.

He rode in the

Grand Review in Washington, D.C. before mustering out with the 70th Indiana on June 8, 1865.

Postwar career

Indiana politics

While serving in the Union Army in October 1864, Harrison was once again elected

reporter

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

of the

Indiana Supreme Court, although he did not seek the position, and served as the Court's reporter for four more years. The position was not a politically powerful one, but it provided Harrison with a steady income for his work preparing and publishing court opinions, which he sold to the legal profession. Harrison also resumed his law practice in Indianapolis. He became a skilled orator and known as "one of the state's leading lawyers".

In 1869 President

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

appointed Harrison to represent the federal government in a civil suit filed by

Lambdin P. Milligan, whose controversial wartime conviction for

treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

in 1864 led to the landmark

U.S. Supreme Court case ''

Ex parte Milligan''.

The civil case was referred to the U.S. Circuit Court for Indiana at Indianapolis, where it evolved into ''Milligan v. Hovey''.

Although the jury found in Milligan's favor and he had sought hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages, state and federal statutes limited the amount the federal government had to award Milligan to five dollars plus court costs.

Given his rising reputation, local Republicans urged Harrison to run for Congress. He initially confined his political activities to speaking on behalf of other Republican candidates, a task for which he received high praise from his colleagues. In 1872, Harrison campaigned for the Republican nomination for

governor of Indiana. Former governor Oliver Morton favored his opponent,

Thomas M. Browne, and Harrison lost his bid for statewide office. He returned to his law practice and, despite the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "L ...

, was financially successful enough to build a grand new home in Indianapolis in 1874. He continued to make speeches on behalf of Republican candidates and policies.

In 1876, when a scandal forced the original Republican nominee,

Godlove Stein Orth, to drop out of the gubernatorial race, Harrison accepted the party's invitation to take his place on the ticket. He centered his campaign on economic policy and favored deflating the national currency. He was defeated in a plurality by

James D. Williams, losing by 5,084 votes out 434,457 cast, but Harrison built on his new prominence in state politics. When the

Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. The Great Railroad Strike of 187 ...

reached Indianapolis, he gathered a citizen militia to make a show of support for owners and management, and helped mediate an agreement between the workers and management and to prevent the strike from widening.

When U.S. Senator Morton died in 1877, the Republicans nominated Harrison to run for the seat, but the party failed to gain a majority in the state legislature, which at that time elected senators; the Democratic majority elected

Daniel W. Voorhees instead. In 1879, President

Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Harrison to the

Mississippi River Commission, which worked to develop internal improvements on the river. As a delegate to the

1880 Republican National Convention

The 1880 Republican National Convention was held from June 2 to June 8, 1880, at the Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Delegates nominated James A. Garfield of Ohio and Chester A. Arthur of New York (state), N ...

, he was instrumental in breaking a deadlock on candidates, and

James A. Garfield won the nomination.

U.S. senator from Indiana

After Harrison led Indiana's delegation at the 1880 Republican National Convention, he was considered the state's presumptive candidate for U.S. Senate. He gave speeches in favor of Garfield in Indiana and New York, further raising his profile in the party. When Republicans retook the majority in the

state legislature, Harrison's election to a six-year term in the U.S. Senate was threatened by Judge

Walter Q. Gresham, his intraparty rival, but Harrison was ultimately chosen. After Garfield's election as president in 1880, his administration offered Harrison a cabinet position, but Harrison declined in favor of continuing his service in the Senate.

Harrison served in the Senate from March 4, 1881, to March 3, 1887, and chaired the

U.S. Senate Committee on Transportation Routes to the Seaboard (

47th Congress) and the

U.S. Senate Committee on Territories (

48th and

49th Congresses).

In 1881, the major issue confronting Senator Harrison was the budget surplus. Democrats wanted to reduce the

tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

and limit the amount of money the government took in; Republicans instead wanted to spend the money on

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

and pensions for Civil War veterans. Harrison took his party's side and advocated for generous

pension

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a " defined benefit plan", wh ...

s for veterans and their widows. He also unsuccessfully supported aid for the education of Southerners, especially children of the freedmen; he believed education was necessary to help the black population rise to political and economic equality with whites. Harrison opposed the

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which his party supported, because he thought it violated existing treaties with

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

.

In 1884, Harrison and Gresham competed for influence at the

1884 Republican National Convention; the delegation ended up supporting Senator

James G. Blaine, the eventual nominee. During the

Mugwump

The Mugwumps were History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. They famously Party switching, swit ...

rebellion led by reform Republicans against Blaine's candidacy, Harrison at first stood aloof, "refusing to put his hat in the presidential ring", but after walking the middle ground he eventually supported Blaine "with energy and enthusiasm".

In the Senate, Harrison achieved passage of his Dependent Pension Bill, only to see it vetoed by President

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

. His efforts to further the admission of new western states were stymied by Democrats, who feared that the new states would elect Republicans to Congress.

In 1885 the Democrats redistricted the Indiana state legislature, which resulted in an increased Democratic majority in 1886, despite a statewide Republican majority. In 1887, largely as a result of the Democratic

gerrymandering of Indiana's legislative districts, Harrison was defeated for reelection. After a deadlock in the

state senate

In the United States, the state legislature is the legislative branch in each of the 50 U.S. states.

A legislature generally performs state duties for a state in the same way that the United States Congress performs national duties at ...

, the state legislature eventually chose Democrat

David Turpie as Harrison's successor in the Senate. Harrison returned to Indianapolis and resumed his law practice, but stayed active in state and national politics. A year after his senatorial defeat, Harrison declared his candidacy for the Republican nomination; he dubbed himself a "living and rejuvenated Republican", a reference to his lack of a power base.

Thereafter, the phrase "'Rejuvenated Republicanism' became the slogan of his presidential campaign."

Election of 1888

Nomination for president

The initial favorite for the Republican nomination was the previous nominee, James G. Blaine of

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. After his narrow loss to Cleveland in 1884, Blaine became the front-runner for 1888, but removed his name from contention.

After he wrote several letters denying any interest in the nomination, his supporters divided among other candidates, Senator

John Sherman of Ohio foremost among them. Others, including

Chauncey Depew of

New York,

Russell Alger of

Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

, and Harrison's old nemesis Walter Q. Gresham—now

a federal appellate court judge in Chicago—also sought the delegates' support at the

1888 Republican National Convention

The 1888 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, Illinois, on June 19–25, 1888. It resulted in the nomination of former United States Senate, Senator Benjamin Harrison of ...

. Harrison "marshaled his troops" to stop Gresham from gaining control of the Indiana delegation while simultaneously presenting himself "as an attractive alternative to Blaine."

Blaine did not publicly endorse anyone, but on March 1, 1888, he privately wrote that "the one man remaining who in my judgment can make the best one is Benjamin Harrison." At the convention, which took place in June, Blaine "threw his support to Harrison in the hope of uniting the party" against Cleveland, but the nomination fight was "hotly contested".

The convention opened on June 19 at the

Auditorium Building

The Auditorium Building is a structure at the northwest corner of South Michigan Avenue (Chicago), Michigan Avenue and Ida B. Wells Drive in the Chicago Loop, Loop community area of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Completed in 1889, it is o ...

in Chicago, Illinois.

Proceedings began with an announcement of the party platform; Lincoln was extolled as the "first great leader" of the Republican Party and an "immortal champion of liberty and the rights of the people."

Republican presidents Grant, Garfield, and Arthur were likewise acknowledged with "remembrance and gratitude". The "fundamental idea of the Republican party" was declared to be "hostility to all forms of despotism and oppression", and the Brazilian people were congratulated for their

recent abolition of slavery.

The convention alleged that the "present Administration and the Democratic majority in Congress owe their existence to the suppression of the ballot by a criminal nullification of the Constitution." Anticipating a principal part of Harrison's campaign, the convention also declared itself "uncompromisingly in favor of the

American system of protection" and protested "against its destruction as proposed by the President and his party." The tariff was later to become the "main issue of the campaign" in 1888.

The admission of six new states during Harrison's term, between 1889 and 1890, was foreshadowed with the declaration: "whenever the conditions of population, material resources...and morality are such as to insure a stable local government," the people "should be permitted...to form for themselves constitutions and State government, and be admitted into the Union."

The convention insisted that "The pending bills in the Senate to enable the people of Washington, North Dakota and Montana Territories to...establish State governments, should be passed without unnecessary delay."

The convention began with 17 candidates for the nomination.

Harrison placed fifth on the first ballot, with Sherman in the lead, and the next few ballots showed little change. As the convention proceeded, Harrison became "everyone's second choice in a field of seven candidates".

Then, after Sherman "faltered in the balloting",

Harrison gained support. Blaine supporters shifted their support among candidates they found acceptable, and when they shifted to Harrison, they found a candidate who could attract the votes of many other delegations. Intending to make it undeniably clear he would not be a candidate, Blaine left the country and was staying with

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

in Scotland when the convention began. He did not return to the U.S. until August, and the delegates finally accepted his refusal to be nominated.

After New York switched to Harrison's column, he gained the needed momentum for victory.

The party nominated Harrison for president on the eighth ballot, 544 votes to 108.

Levi P. Morton

Levi Parsons Morton (May 16, 1824 – May 16, 1920) was the 22nd vice president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He also served as List of ambassadors of the United States to France, United States ambassador to France, as a United States H ...

of New York—a banker, former U.S. Minister to France, and former U.S. congressman—was chosen as his running mate.

At their

National Convention in St. Louis, Democrats rallied behind Cleveland and his running mate, Senator

Allen G. Thurman; Vice President

Hendricks had died in office on November 25, 1885.

After returning to the U.S., Blaine visited Harrison at his home in October.

Campaign against Cleveland

Harrison reprised the traditional

front-porch campaign abandoned by his immediate predecessors; he received visiting delegations to Indianapolis and made over 90 pronouncements from his hometown. Republicans campaigned heavily in favor of

protective tariffs, turning out protectionist voters in the important industrial states of the North. The election took place on Tuesday, November 6, 1888; it focused on the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Harrison's home state of Indiana. Harrison and Cleveland split the four, with Harrison winning New York and Indiana. Voter turnout was 79.3%, reflecting large interest in the campaign; nearly eleven million votes were cast. Harrison received 90,000 fewer votes than Cleveland, but carried the

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

, 233 to 168.

Allegations were made against Republicans for engaging in irregular ballot practices; an example was described as

Blocks of Five. On October 31 the ''Indiana Sentinel'' published a letter allegedly by Harrison's friend and supporter,

William Wade Dudley, offering to bribe voters in "blocks of five" to ensure Harrison's election. Harrison neither defended nor repudiated Dudley, but allowed him to remain on the campaign for the remaining few days. After the election, Harrison never spoke to Dudley again.

Harrison had made no political bargains, but his supporters had made many pledges on his behalf. When Boss

Matthew Quay

Matthew Stanley Quay (; September 30, 1833May 28, 1904) was an American politician of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1887 until 1899 and from 1901 until his ...

of Pennsylvania, who was rebuffed for a Cabinet position for his political support during the convention, heard that Harrison ascribed his narrow victory to

Providence, Quay exclaimed that Harrison would never know "how close a number of men were compelled to approach...the penitentiary to make him president". Harrison was known as the Centennial President because his inauguration celebrated the

centenary of the first inauguration of

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

in 1789. In the congressional elections, Republicans increased their membership in the House of Representatives by 19 seats.

Presidency (1889–1893)

Inauguration and cabinet

Harrison was sworn into office on Monday, March 4, 1889, by

Chief Justice Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his t ...

. His speech was brief—half as long as that of his grandfather, William Henry Harrison, whose speech remains the longest inaugural address of a U.S. president. In his speech, Benjamin Harrison credited the nation's growth to the influences of education and religion, urged the cotton states and mining territories to attain the industrial proportions of the eastern states, and promised a protective tariff. Of commerce, he said, "If our great corporations would more scrupulously observe their legal obligations and duties, they would have less call to complain of the limitations of their rights or of interference with their operations." Harrison also urged early statehood for the territories and advocated pensions for veterans, a call that met with enthusiastic applause. In foreign affairs, he reaffirmed the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

as a mainstay of foreign policy, while urging modernization of the Navy and a merchant marine force. He gave his commitment to international peace through noninterference in the affairs of foreign governments.

John Philip Sousa

John Philip Sousa ( , ; November 6, 1854 – March 6, 1932) was an American composer and conductor of the late Romantic music, Romantic era known primarily for American military March (music), marches. He is known as "The March King" or th ...

's

Marine Corps band played at the Inaugural Ball inside the

Pension Building with a large crowd attending. After moving into the White House, Harrison noted, quite prophetically, "There is only a door—one that is never locked—between the president's office and what are not very accurately called his private apartments. There should be an executive office building, not too far away, but wholly distinct from the dwelling house. For everyone else in the public service, there is an unroofed space between the bedroom and the desk."

Harrison acted quite independently in selecting his cabinet, much to Republican bosses' dismay. He began by delaying the presumed nomination of James G. Blaine as secretary of state so as to preclude Blaine's involvement in the formation of the administration, as had occurred in Garfield's term. In fact, other than Blaine, the only Republican boss initially nominated was Redfield Proctor, as secretary of war. Senator Shelby Cullom's comment symbolizes Harrison's steadfast aversion to use federal positions for patronage: "I suppose Harrison treated me as well as he did any other Senator; but whenever he did anything for me, it was done so ungraciously that the concession tended to anger rather than please." Harrison's selections shared particular alliances, such as their service in the Civil War, Indiana citizenship and membership in the Presbyterian Church. Nevertheless, Harrison had alienated pivotal Republican operatives from New York to Pennsylvania to Iowa with these choices and prematurely compromised his political power and future. His normal schedule provided for two full cabinet meetings per week, as well as separate weekly one-on-one meetings with each cabinet member.

In June 1890, Harrison's Postmaster General

John Wanamaker and several Philadelphia friends purchased a large new cottage at

Cape May Point for Harrison's wife,

Caroline. Many believed the cottage gift appeared improper and amounted to a bribe for a cabinet position. Harrison made no comment on the matter for two weeks, then said he had always intended to purchase the cottage once Caroline approved. On July 2, perhaps a little tardily to avoid suspicion, Harrison gave Wanamaker a check for $10,000 () for the cottage.

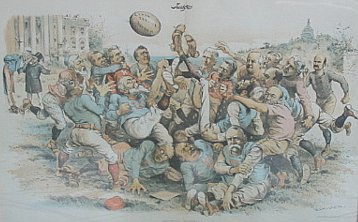

Civil service reform and pensions

Civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

reform was a prominent issue following Harrison's election. Harrison had campaigned as a supporter of the

merit system

The merit system is the process of promoting and hiring government employees based on their ability to perform a job, rather than on their political connections. It is the opposite of the spoils system.

History

The earliest known example of a ...

, as opposed to the

spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a rewar ...

. Although some of the civil service had been classified under the

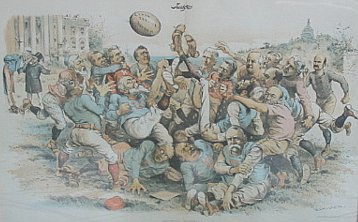

Pendleton Act by previous administrations, Harrison spent much of his first months in office deciding on political appointments. Congress was widely divided on the issue and Harrison was reluctant to address it in hope of preventing the alienation of either side. The issue became a

political football and was immortalized in a cartoon captioned "What can I do when both parties insist on kicking?" Harrison appointed

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

and

Hugh Smith Thompson, both reformers, to the

Civil Service Commission

A civil service commission (also known as a Public Service Commission) is a government agency or public body that is established by the constitution, or by the legislature, to regulate the employment and working conditions of civil servants, overse ...

, but otherwise did little to further the reform cause.

In 1890 Harrison saw the enactment of the

Dependent and Disability Pension Act, a cause he had championed in Congress. In addition to providing pensions to disabled Civil War veterans (regardless of the cause of their disability), the Act depleted some of the troublesome federal budget surplus. Pension expenditures reached $135 million under Harrison (equivalent to $ billion in ), the largest expenditure of its kind to that point in American history, a problem exacerbated by

Pension Bureau commissioner

James R. Tanner's expansive interpretation of the pension laws. An investigation into the Pension Bureau by Secretary of Interior

John Willock Noble found evidence of lavish and illegal handouts under Tanner. Harrison, who privately believed that appointing Tanner had been a mistake, due to his apparent loose management style and tongue, asked Tanner to resign and replaced him with

Green B. Raum. Raum was also accused of accepting loan payments in return for expediting pension cases. Harrison, having accepted a dissenting congressional Republican investigation report that exonerated Raum, kept him in office.

One of the first appointments Harrison was forced to reverse was that of James S. Clarkson as an assistant postmaster. Clarkson, who had expected a full cabinet position, began sabotaging the appointment from the outset, gaining the reputation for "decapitating a fourth class postmaster every three minutes". Clarkson himself said, "I am simply on detail from the Republican Committee ... I am most anxious to get through this task and leave." He resigned in September 1890.

Tariff

Tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

levels had been a major political issue since before the Civil War, and became the most dominant matter of the 1888 election. High tariff rates had created a surplus of money in the Treasury, which led many Democrats (as well as the growing Populist movement) to call for lowering them. Most Republicans preferred to maintain the rates, spend the surplus on

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

, and eliminate some internal taxes.

Representative

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

and Senator

Nelson W. Aldrich framed the

McKinley Tariff, which would raise the tariff even higher, making some rates intentionally prohibitive. At Secretary of State Blaine's urging, Harrison attempted to make the tariff more acceptable by urging Congress to add

reciprocity provisions, which would allow the president to reduce rates when other countries reduced their rates on American exports. The tariff was removed from imported raw sugar, and U.S. sugar growers were given a two cent per pound subsidy on their production. Even with the reductions and reciprocity, the McKinley Tariff enacted the highest average rate in American history, and the spending associated with it contributed to the reputation of the

Billion-Dollar Congress.

Antitrust laws and the currency

Members of both parties were concerned with the growth of the power of

trusts and

monopolies, and one of the first acts of the

51st Congress was to pass the

Sherman Antitrust Act, sponsored by Senator

John Sherman. The Act passed by wide margins in both houses, and Harrison signed it into law. The Sherman Act was the first federal act of its kind, and marked a new use of federal government power. Harrison approved of the law and its intent, but his administration did not enforce it vigorously. However, the government successfully concluded a case during Harrison's time in office (against a Tennessee coal company), and initiated several other cases against trusts.

One of the most volatile questions of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by

gold and silver or by

gold alone. The issue cut across party lines, with western Republicans and southern Democrats joining in the call for the free coinage of silver and both parties' representatives in the northeast holding firm for the gold standard. Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply. Owing to worldwide

deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% and becomes negative. While inflation reduces the value of currency over time, deflation increases i ...

in the late 19th century (resulting from increase in economic output without a corresponding increase in gold supply), a strict gold standard had resulted in reduction of incomes without the equivalent reduction in debts, pushing debtors and the poor to call for silver coinage as an inflationary measure.

The silver coinage issue had not been much discussed in the 1888 campaign, and Harrison is said to have favored a bimetallist position. But his appointment of a silverite Treasury Secretary,

William Windom, encouraged the free silver supporters. Harrison attempted to steer a middle course between the two positions, advocating free coinage of silver, but at its own value, not at a fixed ratio to gold. This failed to facilitate a compromise between the factions. In July 1890, Senator Sherman achieved passage of a bill, the

Sherman Silver Purchase Act, in both houses. Harrison thought the bill would end the controversy, and signed it into law. But the effect of the bill was increased depletion of the nation's gold supply, a problem that persisted until the second Cleveland administration

resolved it.

Civil rights

After regaining the majority in both houses of Congress, some Republicans, led by Harrison, attempted to pass legislation to protect Black Americans' civil rights. Attorney General

William H. H. Miller, through the Justice Department, ordered prosecutions for violation of voting rights in the South, but white juries often failed to convict or indict violators. This prompted Harrison to urge Congress to pass legislation that would "secure all our people a free exercise of the right of suffrage and every other civil right under the Constitution and laws". He endorsed the proposed

Federal Elections Bill written by Representative

Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

and Senator

George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician, represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 until his death in 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politic ...

in 1890, but the bill was defeated in the Senate. After the bill failed to pass, Harrison continued to speak in favor of

African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

civil rights in addresses to Congress. Most notably, on December 3, 1889, Harrison went before Congress and said:

He severely questioned the states' civil rights records, arguing that if states have the authority over civil rights, then "we have a right to ask whether they are at work upon it." Harrison also supported a bill proposed by Senator

Henry W. Blair to grant federal funding to schools regardless of the students' races. He also endorsed a proposed constitutional amendment to overturn the Supreme Court ruling in the ''

Civil Rights Cases'' (1883) that declared much of the

Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional. None of these measures gained congressional approval.

National forests

In March 1891 Congress enacted, and Harrison signed, the

Land Revision Act of 1891. This legislation resulted from a bipartisan desire to initiate

reclamation of surplus lands that had been, up to that point, granted from the public domain, for potential settlement or use by railroad syndicates. As the law's drafting was finalized, Section 24 was added at the behest of Harrison by his Secretary of the Interior John Noble, which read as follows:

Within a month of the enactment of this law Harrison authorized the first forest reserve, to be located on public domain adjacent to

Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

, in Wyoming. Other areas were so designated by Harrison, bringing the first forest reservations total to 22 million acres in his term. Harrison was also the first to give a prehistoric Indian ruin,

Casa Grande in Arizona, federal protection.

Labor policy

Various reforms affecting labor were carried out during Harrison's administration. An Act was passed in 1891 relating to convict labor that prohibited, as one study noted, "work outside the prison enclosure or machine production of commodities". The same year, the first federal legislation governing inspection practices and safety standards and inspection practices in America's coal mines was enacted. In 1892, Congress allocated $20,000 to the Commissioner of Labor "to make a full investigation relative to what is known as the slums of cities" with a population of 200,000 or more in 1890. In August that year, an eight-hour workday was introduced for all mechanics and laborers working for the federal government, along with subcontractors or contractors of public works projects. A Railway Safety Appliance Act introduced the next year included various provisions designed to protect railway workers from harm.

Native American policy

During Harrison's administration, the

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language

Lakota ( ), also referred to as Lakhota, Teton or Teton Sioux, is a Siouan languages, Siouan language spoken by the Lakota people of ...

, who had been forcibly confined to

reservations in

South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

, grew restive under the influence of

Wovoka, a

medicine man

A medicine man (from Ojibwe ''mashkikiiwinini'') or medicine woman (from Ojibwe ''mashkikiiwininiikwe'') is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Each culture has its own name i ...

, who encouraged them to participate in a spiritual movement known as the

Ghost Dance. Though the movement called for the removal of

white Americans

White Americans (sometimes also called Caucasian Americans) are Americans who identify as white people. In a more official sense, the United States Census Bureau, which collects demographic data on Americans, defines "white" as " person hav ...

from indigenous lands, it was primarily religious in nature, a fact that many in Washington did not understand; assuming that the Ghost Dance would increase Lakota resistance to U.S. government, they ordered the

American military to increase its presence on the reservations. On December 29, 1890, the

U.S. Army's

7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Irish air " Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune. The regiment participated in some of the largest ba ...

perpetrated a

massacre of over 250 Lakota at the

Pine Ridge Indian Reservation near

Wounded Knee Creek after a botched attempt to disarm the reservation's inhabitants. American soldiers buried the massacre's victims, many of them women and children, in

mass grave

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may Unidentified decedent, not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of exec ...

s.

In response to the massacre, Harrison directed Major-General

Nelson A. Miles to investigate and ordered 3,500 U.S. troops to be

deployed to South Dakota, which suppressed the Ghost Dance movement. The massacre has been widely considered the last major engagement of the

American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonization of the Americas, European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States o ...

. Harrison's general policy on

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans (also called American Indians, First Americans, or Indigenous Americans) are the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of the United States, particularly of the Contiguous United States, lower 48 states and A ...

was to encourage their

assimilation into white society and, despite the massacre, he believed the policy to have been generally successful. This policy, known as the allotment system and embodied in the

Dawes Act, was favored by liberal reformers at the time, but eventually proved detrimental to Native Americans as they sold most of their land at low prices to white speculators.

Technology and naval modernization

During Harrison's time in office, the United States was continuing to experience advances in science and technology. A recording of his voice is the earliest extant recording of a president while he was in office. That was originally made on a wax

phonograph cylinder

Phonograph cylinders (also referred to as Edison cylinders after its creator Thomas Edison) are the earliest commercial medium for Sound recording and reproduction, recording and reproducing sound. Commonly known simply as "records" in their heyda ...

in 1889 by

Gianni Bettini.

Harrison also had electricity installed in the White House for the first time by

Edison General Electric Company, but he and his wife did not touch the light switches for fear of electrocution and often went to sleep with the lights on.

Over the course of his administration, Harrison marshaled the country's technology to clothe the nation with a credible naval power. When he took office there were only two commissioned warships in the Navy. In his inaugural address he said, "construction of a sufficient number of warships and their necessary armaments should progress as rapidly as is consistent with care and perfection." Secretary of the Navy

Benjamin F. Tracy spearheaded the rapid construction of vessels, and within a year congressional approval was obtained for building of the warships , , , and . By 1898, with the Carnegie Corporation's help, no fewer than ten modern warships, including steel hulls and greater displacements and armaments, had transformed the U.S. into a legitimate naval power. Seven of these had begun during the Harrison term.

Foreign policy

Latin America and Samoa

Harrison and Secretary of State Blaine were often not the most cordial of friends, but harmonized in an aggressive foreign policy and commercial reciprocity with other nations. Blaine's persistent medical problems warranted a more hands-on effort by Harrison in conducting foreign policy. In

San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, while on tour of the United States in 1891, Harrison proclaimed that the nation was in a "new epoch" of trade and that the expanding navy would protect oceanic shipping and increase American influence and prestige abroad. The

First International Conference of American States met in

Washington in 1889; Harrison set an aggressive agenda, including customs and currency integration, and named a bipartisan delegation to the conference, led by

John B. Henderson and

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

. The conference failed to achieve any diplomatic breakthrough, due in large part to an atmosphere of suspicion fostered by the Argentinian delegation. It did succeed in establishing an information center that became the

Pan American Union. In response to the diplomatic bust, Harrison and Blaine pivoted diplomatically and initiated a crusade for tariff reciprocity with Latin American nations; the Harrison administration concluded eight reciprocity treaties among these countries. On another front, Harrison sent

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

as ambassador to

Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

, but failed in his attempts to establish a naval base there.

In 1889, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

were locked in a dispute over control of the Samoan Islands. Historian George H. Ryden's research indicates Harrison played a key role in determining the status of this Pacific outpost by taking a firm stand on every aspect of Samoa conference negotiations; this included selection of the local ruler, refusal to allow an indemnity for Germany, as well as the establishment of a three-power protectorate, a first for the U.S. These arrangements facilitated the future dominant power of the U.S. in the Pacific; Blaine was absent due to complication of

lumbago

Low back pain or lumbago is a common disorder involving the muscles, nerves, and bones of the back, in between the lower edge of the ribs and the lower fold of the buttocks. Pain can vary from a dull constant ache to a sudden sharp feeling. ...

.

European embargo of U.S. pork

Throughout the 1880s various European countries had imposed a ban on importation of American pork out of an unconfirmed concern of

trichinosis; at issue was over one billion pounds of pork products with a value of $80 million annually (equivalent to $ billion in ). Harrison engaged Whitelaw Reid, minister to France, and

William Walter Phelps, minister to Germany, to restore these exports for the country without delay. Harrison also persuaded Congress to enact the Meat Inspection Act to eliminate the accusations of product compromise, and partnered with Agriculture Secretary Rusk to threaten Germany with retaliation by initiating a U.S. embargo on Germany's highly demanded beet sugar. By September 1891 Germany relented, and Denmark, France, and Austria-Hungary soon followed.

Crises in Aleutian Islands and Chile

The first international crisis Harrison faced arose from disputed fishing rights on the

Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

n coast.

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

claimed fishing and

sealing rights around many of the

Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands ( ; ; , "land of the Aleuts"; possibly from the Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', or "island")—also called the Aleut Islands, Aleutic Islands, or, before Alaska Purchase, 1867, the Catherine Archipelago—are a chain ...

, in violation of U.S. law. As a result, the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

seized several Canadian ships. In 1891, the administration began negotiations with the British that eventually led to a compromise over fishing rights after international arbitration, with the British government paying compensation in 1898.

In 1891, a diplomatic crisis emerged in

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, otherwise known as the

''Baltimore'' Crisis. The American minister to Chile,

Patrick Egan, granted asylum to Chileans who were seeking refuge during the

1891 Chilean Civil War. Previously a militant Irish immigrant to the U.S., Egan was motivated by a personal desire to thwart Great Britain's influence in Chile; his action increased tensions between Chile and the U.S., which began in the early 1880s when Blaine alienated the Chileans in the

War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific (), also known by War of the Pacific#Etymology, multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Treaty of Defensive Alliance (Bolivia–Peru), Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought over Atacama Desert ...

.

The crisis began in earnest when sailors from took

shore leave in

Valparaiso and a fight ensued, resulting in the deaths of two American sailors and the arrest of three dozen others. ''Baltimore''s captain, Winfield Schley, based on the nature of the sailors' wounds, insisted the Chilean police had bayonet-attacked the sailors without provocation. With Blaine incapacitated, Harrison drafted a demand for reparations. Chilean Minister of Foreign Affairs Manuel Matta replied that Harrison's message was "erroneous or deliberately incorrect" and said the Chilean government was treating the affair the same as any other criminal matter.

Tensions increased to the brink of war: Harrison threatened to break off diplomatic relations unless the U.S. received a suitable apology and said the situation required "grave and patriotic consideration". He also said, "If the dignity as well as the prestige and influence of the United States are not to be wholly sacrificed, we must protect those who in foreign ports display the flag or wear the colors." The Navy was placed on a high level of preparedness. A recuperated Blaine made brief conciliatory overtures to the Chilean government that had no support in the administration; he then reversed course and joined the chorus for unconditional concessions and apology by the Chileans, who ultimately obliged, and war was averted. Theodore Roosevelt later applauded Harrison for his use of the "

big stick" in the matter.

Annexation of Hawaii

In the last days of his administration, Harrison dealt with the issue of

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

an annexation. Following

a coup d'état against Queen

Liliʻuokalani, Hawaii's new government, led by

Sanford Dole, petitioned for annexation by the United States. Harrison was interested in expanding American influence in Hawaii and in establishing a naval base at

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

but had not previously expressed an opinion on annexing the islands. The U.S.

consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

in Hawaii,

John L. Stevens, recognized the new government on February 1, 1893, and forwarded its proposals to Washington. With just one month left before leaving office, the administration signed a treaty on February 14 and submitted it to the Senate the next day with Harrison's recommendation. The Senate failed to act, and President Cleveland withdrew the treaty shortly after taking office.

Cabinet

Judicial appointments

Harrison appointed four justices to the

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

. The first was

David Josiah Brewer, a judge on the

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. The nephew of Justice

Field, Brewer had previously been considered for a cabinet position. Shortly after his nomination, Justice

Matthews died, creating another vacancy. Harrison had considered

Henry Billings Brown, a

Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

judge and

admiralty law

Maritime law or admiralty law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and conflict of laws, private international law governing the relations ...

expert, for the first vacancy and now nominated him for the second. For the third vacancy, which arose in 1892, Harrison nominated

George Shiras. Shiras's appointment was somewhat controversial because his age—60—was higher than usual for a newly appointed justice. Shiras was also opposed by Senator

Matthew Quay

Matthew Stanley Quay (; September 30, 1833May 28, 1904) was an American politician of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1887 until 1899 and from 1901 until his ...