Battle of Warsaw (1944) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major

In 1944, Poland had been occupied by Nazi Germany for almost five years. The

In 1944, Poland had been occupied by Nazi Germany for almost five years. The  The Soviets and the Poles distrusted each other and

The Soviets and the Poles distrusted each other and

The situation came to a head on 13 July 1944 as the Soviet offensive crossed the old Polish border. At this point the Poles had to make a decision: either initiate the uprising in the current difficult political situation and risk a lack of Soviet support, or fail to rebel and face

The situation came to a head on 13 July 1944 as the Soviet offensive crossed the old Polish border. At this point the Poles had to make a decision: either initiate the uprising in the current difficult political situation and risk a lack of Soviet support, or fail to rebel and face

Colonel Antoni Chruściel (codename "Monter") who commanded the Polish underground forces in Warsaw, divided his units into eight areas: the Sub-district I of Śródmieście (Area I) which included Warszawa-Śródmieście and the Old Town; the Sub-district II of Żoliborz (Area II) comprising

Colonel Antoni Chruściel (codename "Monter") who commanded the Polish underground forces in Warsaw, divided his units into eight areas: the Sub-district I of Śródmieście (Area I) which included Warszawa-Śródmieście and the Old Town; the Sub-district II of Żoliborz (Area II) comprising  The exact number of the foreign fighters (''obcokrajowcy'' in Polish), who fought in Warsaw for Poland's independence, is difficult to determine, taking into consideration the chaotic character of the Uprising causing their irregular registration. It is estimated that they numbered several hundred and represented at least 15 countries – Slovakia, Hungary, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece, Italy, the United States, the Soviet Union, South Africa, Romania, Germany, and even

The exact number of the foreign fighters (''obcokrajowcy'' in Polish), who fought in Warsaw for Poland's independence, is difficult to determine, taking into consideration the chaotic character of the Uprising causing their irregular registration. It is estimated that they numbered several hundred and represented at least 15 countries – Slovakia, Hungary, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece, Italy, the United States, the Soviet Union, South Africa, Romania, Germany, and even

In late July 1944 the German units stationed in and around Warsaw were divided into three categories. The first and the most numerous was the garrison of Warsaw. As of 31 July, it numbered some 11,000 troops under General Rainer Stahel.

In late July 1944 the German units stationed in and around Warsaw were divided into three categories. The first and the most numerous was the garrison of Warsaw. As of 31 July, it numbered some 11,000 troops under General Rainer Stahel.

These well-equipped German forces prepared for the defence of the city's key positions for many months. Several hundred concrete bunkers and barbed wire lines protected the buildings and areas occupied by the Germans. Apart from the garrison itself, numerous army units were stationed on both banks of the Vistula and in the city. The second category was composed of police and SS, under SS and Police Leader SS-''

These well-equipped German forces prepared for the defence of the city's key positions for many months. Several hundred concrete bunkers and barbed wire lines protected the buildings and areas occupied by the Germans. Apart from the garrison itself, numerous army units were stationed on both banks of the Vistula and in the city. The second category was composed of police and SS, under SS and Police Leader SS-''

That evening the resistance captured a major German arsenal, the main post office and power station and the Prudential building. However, Castle Square, the police district, and the airport remained in German hands. The first days were crucial in establishing the battlefield for the rest of the fight. The resistance fighters were most successful in the

That evening the resistance captured a major German arsenal, the main post office and power station and the Prudential building. However, Castle Square, the police district, and the airport remained in German hands. The first days were crucial in establishing the battlefield for the rest of the fight. The resistance fighters were most successful in the

The uprising was intended to last a few days until Soviet forces arrived; however, this never happened, and the Polish forces had to fight with little outside assistance. The results of the first two days of fighting in different parts of the city were as follows:

* ''Area I'' (city centre and the Old Town): Units captured most of their assigned territory, but failed to capture areas with strong pockets of resistance from the Germans (the Warsaw University buildings,

The uprising was intended to last a few days until Soviet forces arrived; however, this never happened, and the Polish forces had to fight with little outside assistance. The results of the first two days of fighting in different parts of the city were as follows:

* ''Area I'' (city centre and the Old Town): Units captured most of their assigned territory, but failed to capture areas with strong pockets of resistance from the Germans (the Warsaw University buildings,

The Uprising reached its

The Uprising reached its

Despite the loss of Wola, the Polish resistance strengthened. ''Zośka'' and ''Wacek'' battalions managed to capture the ruins of the

Despite the loss of Wola, the Polish resistance strengthened. ''Zośka'' and ''Wacek'' battalions managed to capture the ruins of the

The limited landings by the 1st Polish Army represented the only external ground force which arrived to physically support the uprising; and even they were curtailed by the Soviet High Command due to the losses they took.

The Germans intensified their attacks on the Home Army positions near the river to prevent any further landings, but were not able to make any significant advances for several days while Polish forces held those vital positions in preparation for a new expected wave of Soviet landings. Polish units from the eastern shore attempted several more landings, and from 15 to 23 September sustained heavy losses (including the destruction of all their landing boats and most of their other river crossing equipment). Red Army support was inadequate. After the failure of repeated attempts by the 1st Polish Army to link up with the resistance, the Soviets limited their assistance to sporadic artillery and air support. Conditions that prevented the Germans from dislodging the resistance also acted to prevent the Poles from dislodging the Germans. Plans for a river crossing were suspended "for at least 4 months", since operations against the 9th Army's five

The limited landings by the 1st Polish Army represented the only external ground force which arrived to physically support the uprising; and even they were curtailed by the Soviet High Command due to the losses they took.

The Germans intensified their attacks on the Home Army positions near the river to prevent any further landings, but were not able to make any significant advances for several days while Polish forces held those vital positions in preparation for a new expected wave of Soviet landings. Polish units from the eastern shore attempted several more landings, and from 15 to 23 September sustained heavy losses (including the destruction of all their landing boats and most of their other river crossing equipment). Red Army support was inadequate. After the failure of repeated attempts by the 1st Polish Army to link up with the resistance, the Soviets limited their assistance to sporadic artillery and air support. Conditions that prevented the Germans from dislodging the resistance also acted to prevent the Poles from dislodging the Germans. Plans for a river crossing were suspended "for at least 4 months", since operations against the 9th Army's five

In 1939 Warsaw had roughly 1,350,000 inhabitants. Over a million were still living in the city at the start of the Uprising. In Polish-controlled territory, during the first weeks of the Uprising, people tried to recreate the normal day-to-day life of their free country. Cultural life was vibrant, both among the soldiers and civilian population, with theatres, post offices, newspapers and similar activities. Boys and girls of the

In 1939 Warsaw had roughly 1,350,000 inhabitants. Over a million were still living in the city at the start of the Uprising. In Polish-controlled territory, during the first weeks of the Uprising, people tried to recreate the normal day-to-day life of their free country. Cultural life was vibrant, both among the soldiers and civilian population, with theatres, post offices, newspapers and similar activities. Boys and girls of the

According to many historians, a major cause of the eventual failure of the uprising was the almost complete lack of outside support and the late arrival of that which did arrive. The Polish government-in-exile carried out frantic diplomatic efforts to gain support from the Western Allies prior to the start of battle but the allies would not act without Soviet approval. The Polish government in London asked the British several times to send an allied mission to Poland. However, the British mission did not arrive until December 1944. Shortly after their arrival, they met up with Soviet authorities, who arrested and imprisoned them. In the words of the mission's deputy commander, it was "a complete failure". Nevertheless, from August 1943 to July 1944, over 200 British

According to many historians, a major cause of the eventual failure of the uprising was the almost complete lack of outside support and the late arrival of that which did arrive. The Polish government-in-exile carried out frantic diplomatic efforts to gain support from the Western Allies prior to the start of battle but the allies would not act without Soviet approval. The Polish government in London asked the British several times to send an allied mission to Poland. However, the British mission did not arrive until December 1944. Shortly after their arrival, they met up with Soviet authorities, who arrested and imprisoned them. In the words of the mission's deputy commander, it was "a complete failure". Nevertheless, from August 1943 to July 1944, over 200 British

From 4 August the Western Allies began supporting the Uprising with airdrops of munitions and other supplies. Initially the flights were carried out mostly by the ''1568th Polish Special Duties Flight'' of the

From 4 August the Western Allies began supporting the Uprising with airdrops of munitions and other supplies. Initially the flights were carried out mostly by the ''1568th Polish Special Duties Flight'' of the  Finally on 18 September the Soviets allowed a

Finally on 18 September the Soviets allowed a

The role of the Red Army during the Warsaw Uprising remains controversial and is still disputed by historians. The Uprising started when the Red Army appeared on the city's doorstep, and the Poles in Warsaw were counting on Soviet front capturing or forwarding beyond the city in a matter of days. This basic scenario of an uprising against the Germans, launched a few days before the arrival of Allied forces, played out successfully in a number of European capitals, such as

The role of the Red Army during the Warsaw Uprising remains controversial and is still disputed by historians. The Uprising started when the Red Army appeared on the city's doorstep, and the Poles in Warsaw were counting on Soviet front capturing or forwarding beyond the city in a matter of days. This basic scenario of an uprising against the Germans, launched a few days before the arrival of Allied forces, played out successfully in a number of European capitals, such as  The Red Army was fighting intense battles further to the south of Warsaw, to seize and maintain bridgeheads over the Vistula river, and to the north of the city, to gain bridgeheads over the river Narew. The best German armoured divisions were fighting on those sectors. Despite the fact, both of these objectives had been mostly secured by September. Yet the Soviet 47th Army did not move into

The Red Army was fighting intense battles further to the south of Warsaw, to seize and maintain bridgeheads over the Vistula river, and to the north of the city, to gain bridgeheads over the river Narew. The best German armoured divisions were fighting on those sectors. Despite the fact, both of these objectives had been mostly secured by September. Yet the Soviet 47th Army did not move into  One way or the other, the presence of Soviet tanks in nearby

One way or the other, the presence of Soviet tanks in nearby  The Soviet units which reached the outskirts of Warsaw in the final days of July 1944 had advanced from the

The Soviet units which reached the outskirts of Warsaw in the final days of July 1944 had advanced from the

However, by the morning of 27 September, the Germans had retaken Mokotów. Talks restarted on 28 September. In the evening of 30 September, Żoliborz fell to the Germans. The Poles were being pushed back into fewer and fewer streets, and their situation was ever more desperate. On the 30th, Hitler decorated von dem Bach, Dirlewanger and Reinefarth, while in London General Sosnkowski was dismissed as Polish commander-in-chief. Bór-Komorowski was promoted in his place, even though he was trapped in Warsaw. Bór-Komorowski and Prime Minister Mikołajczyk again appealed directly to Rokossovsky and Stalin for a Soviet intervention. None came. According to Soviet Marshal

However, by the morning of 27 September, the Germans had retaken Mokotów. Talks restarted on 28 September. In the evening of 30 September, Żoliborz fell to the Germans. The Poles were being pushed back into fewer and fewer streets, and their situation was ever more desperate. On the 30th, Hitler decorated von dem Bach, Dirlewanger and Reinefarth, while in London General Sosnkowski was dismissed as Polish commander-in-chief. Bór-Komorowski was promoted in his place, even though he was trapped in Warsaw. Bór-Komorowski and Prime Minister Mikołajczyk again appealed directly to Rokossovsky and Stalin for a Soviet intervention. None came. According to Soviet Marshal

The destruction of the Polish capital was planned before the start of World War II. On 20 June 1939, while Adolf Hitler was visiting an architectural bureau in

The destruction of the Polish capital was planned before the start of World War II. On 20 June 1939, while Adolf Hitler was visiting an architectural bureau in

Most soldiers of the Home Army (including those who took part in the Warsaw Uprising) were persecuted after the war; captured by the

Most soldiers of the Home Army (including those who took part in the Warsaw Uprising) were persecuted after the war; captured by the  The facts of the Warsaw Uprising were inconvenient to Stalin, and were twisted by propaganda of the

The facts of the Warsaw Uprising were inconvenient to Stalin, and were twisted by propaganda of the

File:Warsaw 1944 by Lubicz - Stolica 004.jpg, Bunker in front of gate to University of Warsaw converted to a base for Wehrmacht viewed from Krakowskie Przedmieście Street, July 1944

Image:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-R97906 Warschauer Aufstand, Straßenkampf, SS.jpg, Members of the SS-Sonderregiment Dirlewanger fighting in Warsaw, pictured in window of a townhouse at Focha Street, August 1944

File:Generał Heinz Reinefarth w czapce kubance i 3 pułk Kozaków.jpg, German SS-''

Warsaw Rising Museum in Warsaw

at Polonia Today

Warsaw Rising: The Forgotten Soldiers of World War II. Educator GuideWarsaw Uprising 1944

A source for checking data used in this page and offers of material and help.

page provides information and maps which may be freely copied with attribution.

Warsaw Life: A detailed account of the 1944 Warsaw Rising, including the facts, the politics and first-hand accountsThe Warsaw Uprising daily diary, written in English by Eugenuisz Melech, on the events as they happened.Anglo-Polish Radio ORLA.fm

Has broadcast several historical programmes on the Warsaw Uprising

Website summarizing many publications against decision to initiate Warsaw Uprising

Dariusz Baliszewski, ''Przerwać tę rzeź!'' Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1132 (8 August 2004)

Warschau – Der letzte Blick

German aerial photos of Warsaw taken during the last days before the Warsaw Uprising

– Daily Telegraph obituary

Interview with Warsaw Uprising veteran Stefan Bałuk

The State We're in from Radio Netherlands Worldwide

'Chronicles of Terror' – collection of civilian testimonies concerning Warsaw Uprising

{{Authority control Battles and operations of World War II Battles of Operation Tempest Conflicts in 1944 Mass murder in 1944 Military history of Warsaw Uprisings during World War II

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

operation by the Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

from German occupation. It occurred in the summer of 1944, and it was led by the Polish resistance Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

( pl, Armia Krajowa). The uprising was timed to coincide with the retreat of the German forces from Poland ahead of the Soviet advance. While approaching the eastern suburbs of the city, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

temporarily halted combat operations, enabling the Germans to regroup and defeat the Polish resistance and to destroy the city in retaliation. The Uprising was fought for 63 days with little outside support. It was the single largest military effort taken by any European resistance movement during World War II.

The Uprising began on 1 August 1944 as part of a nationwide Operation Tempest

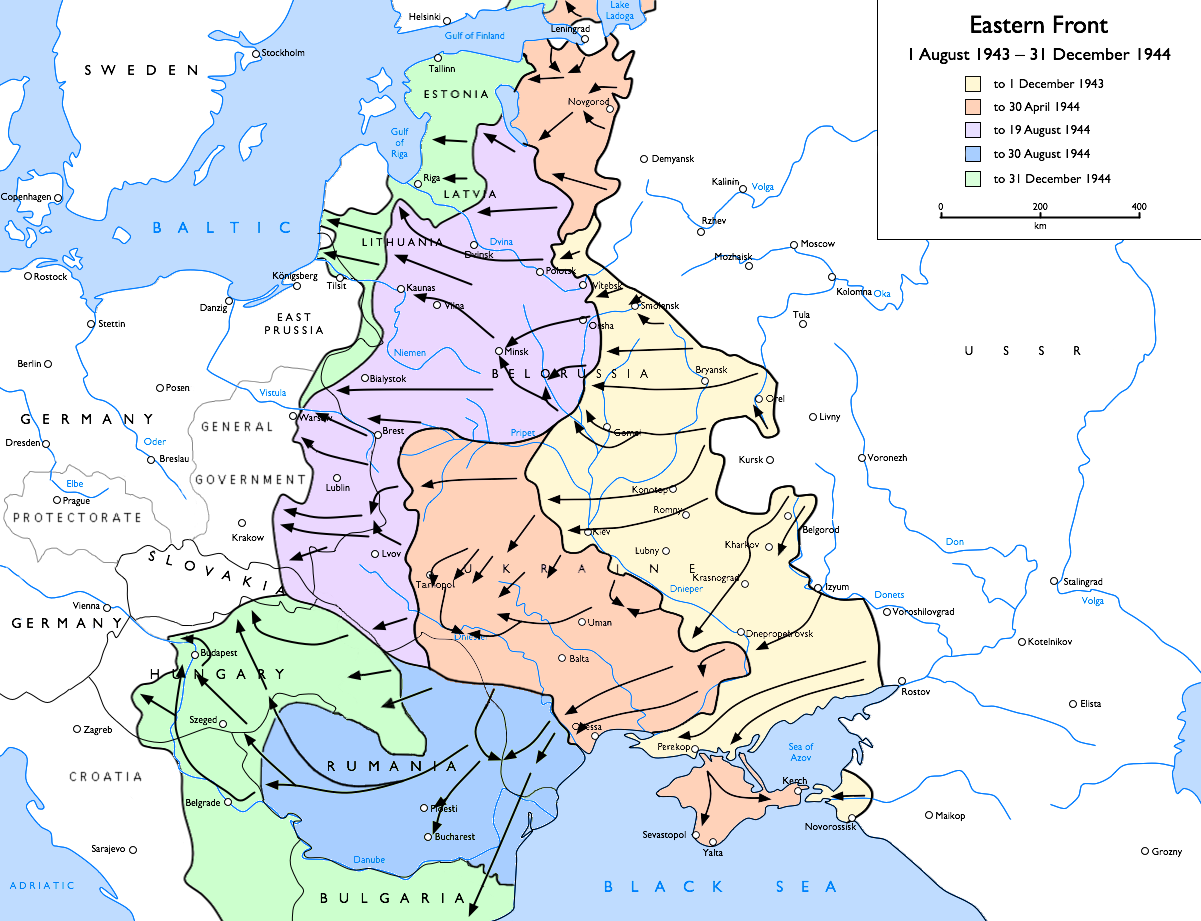

file:Akcja_burza_1944.png, 210px, right

Operation Tempest ( pl, akcja „Burza”, sometimes referred to in English as "Operation Storm") was a series of uprisings conducted during World War II against occupying German forces by the Polish Home ...

, launched at the time of the Soviet Lublin–Brest Offensive

The Lublin–Brest Offensive (russian: Люблин‐Брестская наступательная операция, 18 July – 2 August 1944) was a part of the Operation Bagration strategic offensive by the Soviet Red Army to clear the Nazi ...

. The main Polish objectives were to drive the Germans out of Warsaw while helping the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

defeat Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. An additional, political goal of the Polish Underground State

The Polish Underground State ( pl, Polskie Państwo Podziemne, also known as the Polish Secret State) was a single political and military entity formed by the union of resistance organizations in occupied Poland that were loyal to the Gover ...

was to liberate Poland's capital and assert Polish sovereignty before the Soviet-backed Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polish: ''Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego'', ''PKWN''), also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the lat ...

could assume control. Other immediate causes included a threat of mass German round-ups of able-bodied Poles for "evacuation"; calls by Radio Moscow

Radio Moscow ( rus, Pадио Москва, r=Radio Moskva), also known as Radio Moscow World Service, was the official international broadcasting station of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics until 1993. It was reorganized with a new name ...

's Polish Service for uprising; and an emotional Polish desire for justice and revenge against the enemy after five years of German occupation.

Initially, the Poles established control over most of central Warsaw, but the Soviets ignored Polish attempts to make radio contact with them and did not advance beyond the city limits. Intense street fighting between the Germans and Poles continued. By 14 September, the eastern bank of the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

River opposite the Polish resistance positions was taken over by the Polish troops fighting under the Soviet command; 1,200 men made it across the river, but they were not reinforced by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

. This, and the lack of air support from the Soviet air base five-minutes flying time away, led to allegations that Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

tactically halted his forces to let the operation fail and allow the Polish resistance to be crushed. Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, (, ; ; hu, Kösztler Artúr; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was a Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria. In 1931, Koestler join ...

called the Soviet attitude "one of the major infamies of this war which will rank for the future historian on the same ethical level with Lidice

Lidice (, german: Liditz) is a municipality and village in Kladno District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 600 inhabitants.

Lidice is built near the site of the previous village of the same name, which was com ...

." On the other hand, David Glantz

David M. Glantz (born January 11, 1942) is an American military historian known for his books on the Red Army during World War II and as the chief editor of ''The Journal of Slavic Military Studies''.

Born in Port Chester, New York, Glantz r ...

argued that the uprising started too early and the Red Army could not realistically have aided it, regardless of Soviet intentions.

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

pleaded with Stalin and Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

to help Britain's Polish allies, to no avail. Then, without Soviet air clearance, Churchill sent over 200 low-level supply drops by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, the South African Air Force

"Through hardships to the stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, equipment ...

, and the Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force ( pl, Siły Powietrzne, , Air Forces) is the aerial warfare branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 16,425 mil ...

under British High Command, in an operation known as the Warsaw Airlift

The Warsaw airlift or Warsaw air bridge was a British-led operation to re-supply the besieged Polish resistance Home Army (AK) in the Warsaw Uprising against Nazi Germany during the Second World War, after nearby Soviet forces chose not to come to ...

. Later, after gaining Soviet air clearance, the U.S. Army Air Force

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

sent one high-level mass airdrop as part of Operation Frantic

Operation Frantic was a series of seven shuttle bombing List of air operations during the Battle of Europe, operations during World War II conducted by American aircraft based in Great Britain and southern Italy which then landed at three Soviet ...

, although 80% of these supplies landed in German-controlled territory.

Although the exact number of casualties is unknown, it is estimated that about 16,000 members of the Polish resistance were killed and about 6,000 badly wounded. In addition, between 150,000 and 200,000 Polish civilians died, mostly from mass executions. Jews being harboured by Poles were exposed by German house-to-house clearances and mass evictions of entire neighbourhoods. German casualties totalled over 2,000 to 17,000 soldiers killed and missing. During the urban combat

Urban warfare is combat conducted in urban areas such as towns and cities. Urban combat differs from combat in the open at both the operational and the tactical levels. Complicating factors in urban warfare include the presence of civilians and t ...

, approximately 25% of Warsaw's buildings were destroyed. Following the surrender of Polish forces, German troops systematically levelled another 35% of the city block by block. Together with earlier damage suffered in the 1939 invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; pl, powstanie w getcie warszawskim; german: link=no, Aufstand im Warschauer Ghetto was the 1943 act of Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto in German-occupied Poland during World War II to oppose Nazi Germany's ...

in 1943, over 85% of the city was destroyed by January 1945 when the course of the events in the Eastern Front forced the Germans to abandon the city.

Background

In 1944, Poland had been occupied by Nazi Germany for almost five years. The

In 1944, Poland had been occupied by Nazi Germany for almost five years. The Polish Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

planned some form of rebellion against German forces. Germany was fighting a coalition of Allied powers, led by the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States. The initial plan of the Home Army was to link up with the invading forces of the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy. ...

as they liberated Europe from the Nazis. However, when the Soviet Army began its offensive in 1943, it became clear that Poland would be liberated by it instead of the Western Allies.

The Soviets and the Poles had a common enemy—Germany—but were working towards different post-war goals: the Home Army desired a pro-Western, capitalist Poland, but the Soviet leader Stalin intended to establish a pro-Soviet, socialist Poland. It became obvious that the advancing Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

might not come to Poland as an ally but rather only as "the ally of an ally".

"The Home Commander was, in his political thinking, pledged to the doctrine of two enemies, in accordance with which both Germany and Russia were seen as Poland's traditional enemies, and it was expected that support for Poland, if any, would come from the West".

The Soviets and the Poles distrusted each other and

The Soviets and the Poles distrusted each other and Soviet partisans in Poland

Poland was invaded and annexed by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the invasion of Poland in 1939. In the pre-war Polish territories annexed by the Soviets (modern-day western Ukraine, Western Belarus, Lithuania and Białyst ...

often clashed with a Polish resistance increasingly united under the Home Army's front. Stalin broke off Polish–Soviet relations on 25 April 1943 after the Germans revealed the Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, "Katyń crime"; russian: link=yes, Катынская резня ''Katynskaya reznya'', "Katyn massacre", or russian: link=no, Катынский расстрел, ''Katynsky rasstrel'', "Katyn execution" was a series of m ...

of Polish army officers, and Stalin refused to admit to ordering the killings and denounced the claims as German propaganda. Afterwards, Stalin created the Rudenko Commission, whose goal was to blame the Germans for the war crime at all costs. The Western alliance accepted Stalin's words as truth in order to keep the Anti-Nazi alliance intact. On 26 October, the Polish government-in-exile issued instructions to the effect that, if diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union were not resumed before the Soviet entry into Poland, Home Army forces were to remain underground pending further decisions.

However, the Home Army commander, Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski

Generał Tadeusz Komorowski (1 June 1895 – 24 August 1966), better known by the name Bór-Komorowski (after one of his wartime code-names: ''Bór'' – "The Forest") was a Polish military leader. He was appointed commander in chief a day bef ...

, took a different approach, and on 20 November, he outlined his own plan, which became known as Operation Tempest

file:Akcja_burza_1944.png, 210px, right

Operation Tempest ( pl, akcja „Burza”, sometimes referred to in English as "Operation Storm") was a series of uprisings conducted during World War II against occupying German forces by the Polish Home ...

. On the approach of the Eastern Front, local units of the Home Army were to harass the German ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

'' in the rear and co-operate with incoming Soviet units as much as possible. Although doubts existed about the military necessity of a major uprising, planning continued. General Bór-Komorowski and his civilian advisor were authorised by the government in exile to proclaim a general uprising whenever they saw fit.

Eve of the battle

The situation came to a head on 13 July 1944 as the Soviet offensive crossed the old Polish border. At this point the Poles had to make a decision: either initiate the uprising in the current difficult political situation and risk a lack of Soviet support, or fail to rebel and face

The situation came to a head on 13 July 1944 as the Soviet offensive crossed the old Polish border. At this point the Poles had to make a decision: either initiate the uprising in the current difficult political situation and risk a lack of Soviet support, or fail to rebel and face Soviet propaganda

Propaganda in the Soviet Union was the practice of state-directed communication to promote class conflict, internationalism, the goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the party itself.

The main Soviet censorship body, Glavlit, ...

describing the Home Army as impotent or worse, Nazi collaborators. They feared that if Poland was liberated by the Red Army, then the Allies would ignore the London-based Polish government in the aftermath of the war. The urgency for a final decision on strategy increased as it became clear that, after successful Polish-Soviet co-operation in the liberation of Polish territory (for example, in Operation Ostra Brama

Operation Ostra Brama (lit. Operation Gate of Dawn, Sharp Gate) was an attempt by the Home Army, Polish Home Army to take over Vilnius ( pl, Wilno) from Nazi Germany's evacuating troops ahead of the approaching Soviet Vilnius Offensive. A part o ...

), Soviet security forces behind the frontline shot or arrested Polish officers and forcibly conscripted lower ranks into the Soviet-controlled forces. On 21 July, the High Command of the Home Army decided that the time to launch Operation Tempest in Warsaw was imminent. The plan was intended both as a political manifestation of Polish sovereignty and as a direct operation against the German occupiers. On 25 July, the Polish government-in-exile (without the knowledge and against the wishes of Polish Commander-in-Chief General Kazimierz Sosnkowski

General Kazimierz Sosnkowski (; Warsaw, 19 November 1885 – 11 October 1969, Arundel, Quebec) was a Polish independence fighter, general, diplomat, and architect.

He was a major political figure and an accomplished commander, notable in p ...

) approved the plan for an uprising in Warsaw with the timing to be decided locally.

In the early summer of 1944, German plans required Warsaw to serve as the defensive centre of the area and to be held at all costs. The Germans had fortifications constructed and built up their forces in the area. This process slowed after the failed 20 July plot

On 20 July 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg and other conspirators attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler, Führer of Nazi Germany, inside his Wolf's Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg, East Prussia, now Kętrzyn, in present-day Poland. The ...

to assassinate the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, and around that time, the Germans in Warsaw were weak and visibly demoralized. However, by the end of July, German forces in the area were reinforced. On 27 July, the Governor of the Warsaw District, Ludwig Fischer

Ludwig Fischer (16 April 1905 – 8 March 1947) was a German Nazi Party lawyer, politician and a convicted war crimes, war criminal who was executed for war crimes.

Background

Born into a Catholic family in Kaiserslautern, Fischer joined the ...

, called for 100,000 Polish men and women to report for work as part of a plan which envisaged the Poles constructing fortifications around the city. The inhabitants of Warsaw ignored his demand, and the Home Army command became worried about possible reprisals or mass round-ups, which would disable their ability to mobilize. The Soviet forces were approaching Warsaw, and Soviet-controlled radio stations called for the Polish people to rise in arms.

On 25 July, the Union of Polish Patriots

Union of Polish Patriots (''Society of Polish Patriots'', pl, Związek Patriotów Polskich, ZPP, russian: Союз Польских Патриотов, СПП) was a political body created by Polish communists in the Soviet Union in 1943. The Z ...

, in a broadcast from Moscow, stated: "The Polish Army of Polish Patriots ... calls on the thousands of brothers thirsting to fight, to smash the foe before he can recover from his defeat ... Every Polish homestead must become a stronghold in the struggle against the invaders ... Not a moment is to be lost."On 29 July, the first Soviet armoured units reached the outskirts of Warsaw, where they were counter-attacked by two German Panzer Corps: the 39th and 4th SS. On 29 July 1944 Radio Station Kosciuszko located in Moscow emitted a few times its "Appeal to Warsaw" and called to "Fight The Germans!":

"No doubt Warsaw already hears the guns of the battle which is soon to bring her liberation. ... The Polish Army now entering Polish territory, trained in the Soviet Union, is now joined to the People's Army to form the Corps of the Polish Armed Forces, the armed arm of our nation in its struggle for independence. Its ranks will be joined tomorrow by the sons of Warsaw. They will all together, with the Allied Army pursue the enemy westwards, wipe out the Hitlerite vermin from Polish land and strike a mortal blow at the beast of Prussian Imperialism."Bór-Komorowski and several officers held a meeting on that day.

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański (; 2 October 1914 – 20 January 2005) was a Polish journalist, writer, politician, social worker and patriot. He served during the Second World War as one of the most notable resistance fighters of the Home Army. He is b ...

, who had arrived from London, expressed the view that help from the Allies would be limited, but his views received no attention.

"In the early afternoon of 31 July the most important political and military leaders of the resistance had no intention of sending their troops into battle on 1 August. Even so, another late afternoon briefing of Bor-Komorowski's Staff was arranged for five o'clock(...) At about 5.30 p.m. Col 'Monter' arrived at the briefing, reporting that the Russian tanks were already entering Praga and insisting on the immediate launching of the Home Army operations inside the city as otherwise it 'might be too late'. Prompted by 'Monter`s report, Bor-Komorowski decided that the time was ripe for the commencement of 'Burza' in Warsaw, in spite of his earlier conviction to the contrary, twice expressed during the course of that day".

"Bor-Komorowski and Jankowski issued their final order for the insurrection when it was erroneously reported to them that the Soviet tanks were entering Praga. Hence they assumed that the Russo-German battle for Warsaw was approaching its climax and that this presented them with an excellent opportunity to capture Warsaw before the Red Army entered the capital. The Soviet radio appeals calling upon the people of Warsaw to rise against the Germans, regardless of Moscow's intentions, had very little influence on the Polish authorities responsible for the insurrection".

Believing that the time for action had arrived, on 31 July, the Polish commanders General Bór-Komorowski and Colonel Antoni Chruściel

Gen. Antoni Chruściel ( '' nom de guerre'' Monter; 16 July 1895 – 30 November 1960) was a Polish military officer and a general of the Polish Army. He is best known as the ''de facto'' commander of all the armed forces of the Warsaw Uprising o ...

ordered full mobilization of the forces for 17:00 the following day.

Opposing forces

Polish forces

The Home Army forces of the Warsaw District numbered between 20,000, and 49,000 soldiers. Other underground formations also contributed; estimates range from 2,000 in total, to about 3,500 men including those from theNational Armed Forces

National Armed Forces (NSZ; ''Polish:'' Narodowe Siły Zbrojne) was a Polish right-wing underground military organization of the National Democracy operating from 1942. During World War II, NSZ troops fought against Nazi Germany and communist pa ...

and the communist People's Army. Most of them had trained for several years in partisan

Partisan may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (weapon), a pole weapon

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

Films

* ''Partisan'' (film), a 2015 Australian film

* ''Hell River'', a 1974 Yugoslavian film also know ...

and urban guerrilla warfare

An urban guerrilla is someone who fights a government using unconventional warfare or domestic terrorism in an urban environment.

Theory and history

The urban guerrilla phenomenon is essentially one of industrialised society, resting both ...

, but lacked experience in prolonged daylight fighting. The forces lacked equipment, because the Home Army had shuttled weapons to the east of the country before the decision to include Warsaw in Operation Tempest. Other partisan groups subordinated themselves to Home Army command, and many volunteers joined during the fighting, including Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

freed from the Gęsiówka

Gęsiówka () is the colloquial Polish name for a prison that once existed on ''Gęsia'' ("Goose") Street in Warsaw, Poland, and which, under German occupation during World War II, became a Nazi concentration camp.

In 1945–56 the Gęsiówka ...

concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

in the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

. Morale among Jewish fighters was hurt by displays of antisemitism, with several former Jewish prisoners in combat units even killed by antisemitic Poles.

Colonel Antoni Chruściel (codename "Monter") who commanded the Polish underground forces in Warsaw, divided his units into eight areas: the Sub-district I of Śródmieście (Area I) which included Warszawa-Śródmieście and the Old Town; the Sub-district II of Żoliborz (Area II) comprising

Colonel Antoni Chruściel (codename "Monter") who commanded the Polish underground forces in Warsaw, divided his units into eight areas: the Sub-district I of Śródmieście (Area I) which included Warszawa-Śródmieście and the Old Town; the Sub-district II of Żoliborz (Area II) comprising Żoliborz

Żoliborz () is one of the northern districts of the city of Warsaw. It is located directly to the north of the City Centre, on the left bank of the Vistula river. It has approximately 50,000 inhabitants and is one of the smallest boroughs of W ...

, Marymont

Marymont (from French ''Mont de Marie'' - Mary's Hill) is one of the northern neighbourhoods of Warsaw, Poland, administratively a part of the boroughs of Żoliborz (Marymont-Potok) and Bielany (Marymont-Kaskada and Marymont-Ruda). Named after the ...

, and Bielany

Bielany () is a district in Warsaw located in the north-western part of the city.

Initially a part of Żoliborz, Bielany has been an independent district since 1994. Bielany borders Żoliborz to the south-east, and Bemowo to the south-west. Its ...

; the Sub-district III of Wola (Area III) in Wola

Wola (, ) is a district in western Warsaw, Poland, formerly the village of Wielka Wola, incorporated into Warsaw in 1916. An industrial area with traditions reaching back to the early 19th century, it underwent a transformation into an office (co ...

; the Sub-district IV of Ochota (Area IV) in Ochota

Ochota () is a district of Warsaw, Poland, located in the central part of the Polish capital city's urban agglomeration.

The biggest housing estates of Ochota are:

* Kolonia Lubeckiego

* Kolonia Staszica

* Filtry

* Rakowiec

* Szosa Krakowska

...

; the Sub-district V of Mokotów (Area V) in Mokotów

Mokotów , is a ''dzielnica'' (borough, district) of Warsaw, the capital of Poland. Mokotów is densely populated, and is a seat to many foreign embassies and companies. Only a small part of the district is lightly industrialised (''Służewiec ...

; the Sub-district VI of Praga (Area VI) in Praga

Praga is a district of Warsaw, Poland. It is on the east bank of the river Vistula. First mentioned in 1432, until 1791 it formed a separate town with its own city charter.

History

The historical Praga was a small settlement located at ...

; the Sub-district VII of Warsaw suburbs (Area VII) for the Warsaw West County

__NOTOC__

The Warsaw West County ( pl, powiat warszawski zachodni) is a county in Masovian Voivodeship, located in the east-central Poland, with its seat of government located in Ożarów Mazowiecki. Other towns located in the county are: Łomiank ...

; and the Autonomous Region VIII of Okęcie (Area VIII) in Okęcie

Okęcie () is the largest neighbourhood of the Włochy district of Warsaw, Poland.

It is the location of Warsaw Chopin Airport and the PZL Warszawa-Okęcie aircraft works, and home to the Okęcie Warszawa professional association football club. ...

; while the units of the Directorate of Sabotage and Diversion (''Kedyw'') remained attached to the Uprising Headquarters. On 20 September, the sub-districts were reorganized to align with the three areas of the city held by the Polish units. The entire force, renamed the Warsaw Home Army Corps ( pl, Warszawski Korpus Armii Krajowej, links=no) and commanded by General Antoni Chruściel – who was promoted from Colonel on 14 September – formed three infantry divisions (Śródmieście, Żoliborz and Mokotów).

The exact number of the foreign fighters (''obcokrajowcy'' in Polish), who fought in Warsaw for Poland's independence, is difficult to determine, taking into consideration the chaotic character of the Uprising causing their irregular registration. It is estimated that they numbered several hundred and represented at least 15 countries – Slovakia, Hungary, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece, Italy, the United States, the Soviet Union, South Africa, Romania, Germany, and even

The exact number of the foreign fighters (''obcokrajowcy'' in Polish), who fought in Warsaw for Poland's independence, is difficult to determine, taking into consideration the chaotic character of the Uprising causing their irregular registration. It is estimated that they numbered several hundred and represented at least 15 countries – Slovakia, Hungary, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece, Italy, the United States, the Soviet Union, South Africa, Romania, Germany, and even Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

.

These people – emigrants who had settled in Warsaw before the war, escapees from numerous POW, concentration and labor camps, and deserters from the German auxiliary forces – were absorbed in different fighting and supportive formations of the Polish underground. They wore the underground's red-white armband (the colors of the Polish national flag) and adopted the Polish traditional independence fighters' slogan 'Za naszą i waszą wolność'. Some of the 'obcokrajowcy' showed outstanding bravery in fighting the enemy and were awarded the highest decorations of the AK and the Polish government in exile.

During the fighting, the Poles obtained additional supplies through airdrop

An airdrop is a type of airlift in which items including weapons, equipment, humanitarian aid or leaflets are delivered by military or civilian aircraft without their landing. Developed during World War II to resupply otherwise inaccessible tro ...

s and by capture from the enemy, including several armoured vehicles, notably two Panther tank

The Panther tank, officially ''Panzerkampfwagen V Panther'' (abbreviated PzKpfw V) with ordnance inventory designation: ''Sd.Kfz.'' 171, is a German medium tank of World War II. It was used on the Eastern and Western Fronts from mid-1943 to ...

s and two Sd.Kfz. 251

The Sd.Kfz. 251 (''Sonderkraftfahrzeug 251'') half-track was a World War II German armored personnel carrier designed by the Hanomag company, based on its earlier, unarmored Sd.Kfz. 11 vehicle. The Sd.Kfz. 251 was designed to transport the ''Panz ...

armored personnel carrier

An armoured personnel carrier (APC) is a broad type of armoured military vehicle designed to transport personnel and equipment in combat zones. Since World War I, APCs have become a very common piece of military equipment around the world.

Acc ...

s. Also, resistance workshops produced weapons throughout the fighting, including submachine gun

A submachine gun (SMG) is a magazine-fed, automatic carbine designed to fire handgun cartridges. The term "submachine gun" was coined by John T. Thompson, the inventor of the Thompson submachine gun, to describe its design concept as an autom ...

s, K pattern flamethrower

The K pattern flamethrower (Polish: ''miotacz ognia wzór K'') was a man-portable backpack flamethrower, produced in occupied Poland during World War II for the underground Home Army. These flamethrowers were used in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944.

...

s, grenades, mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a village i ...

, and even an armoured car (). As of 1 August, Polish military supplies consisted of 1,000 guns, 1,750 pistols, 300 submachine guns, 60 assault rifles, 7 heavy machine guns, 20 anti-tank guns, and 25,000 hand grenades. "Such collection of light weapons might have been sufficient to launch an urban terror campaign, but not to seize control of the city".

Germans

In late July 1944 the German units stationed in and around Warsaw were divided into three categories. The first and the most numerous was the garrison of Warsaw. As of 31 July, it numbered some 11,000 troops under General Rainer Stahel.

In late July 1944 the German units stationed in and around Warsaw were divided into three categories. The first and the most numerous was the garrison of Warsaw. As of 31 July, it numbered some 11,000 troops under General Rainer Stahel.

These well-equipped German forces prepared for the defence of the city's key positions for many months. Several hundred concrete bunkers and barbed wire lines protected the buildings and areas occupied by the Germans. Apart from the garrison itself, numerous army units were stationed on both banks of the Vistula and in the city. The second category was composed of police and SS, under SS and Police Leader SS-''

These well-equipped German forces prepared for the defence of the city's key positions for many months. Several hundred concrete bunkers and barbed wire lines protected the buildings and areas occupied by the Germans. Apart from the garrison itself, numerous army units were stationed on both banks of the Vistula and in the city. The second category was composed of police and SS, under SS and Police Leader SS-''Oberführer

__NOTOC__

''Oberführer'' (short: ''Oberf'', , ) was an early paramilitary rank of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) dating back to 1921. An ''Oberführer'' was typically a NSDAP member in charge of a group of paramilitary units in a particular geographic ...

'' Paul Otto Geibel, numbering initially 5,710 men, including ''Schutzpolizei

The ''Schutzpolizei'' (), or ''Schupo'' () for short, is a uniform-wearing branch of the '' Landespolizei'', the state (''Land'') level police of the states of Germany. ''Schutzpolizei'' literally means security or protection police, but it is ...

'' and ''Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

''. The third category was formed by various auxiliary units, including detachments of the ''Bahnschutz'' (rail guard), ''Werkschutz'' (factory guard) and the Polish Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

(ethnic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

in Poland) and Soviet former POW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

of the ''Sonderdienst

''Sonderdienst'' (german: Special Services) were the Nazi German paramilitary formations created in semicolonial General Government during the occupation of Poland in World War II. They were based on similar '' SS'' formations called ''Volksdeuts ...

'' and ''Sonderabteilungen'' paramilitary units.

During the uprising the German side received reinforcements on a daily basis. Stahel was replaced as overall commander by SS-General Erich von dem Bach

Erich Julius Eberhard von dem Bach-Zelewski (born Erich Julius Eberhard von Zelewski; 1 March 1899 – 8 March 1972) was a high-ranking SS commander of Nazi Germany. During World War II, he was in charge of the Nazi security warfare against tho ...

in early August.Davies, pp. 666–667. As of 20 August 1944, the German units directly involved with fighting in Warsaw comprised 17,000 men arranged in two battle groups:

* Battle Group Rohr (commanded by Major General Rohr), which included 1,700 soldiers of the anti-communist S.S. Sturmbrigade R.O.N.A. ''Russkaya Osvoboditelnaya Narodnaya Armiya'' (''Russian National Liberation Army'', also known as Kaminski Brigade

Kaminski Brigade, also known as Waffen-Sturm-Brigade der SS RONA, was a collaborationist formation composed of Russian nationals from the territory of the Lokot Autonomy in Axis-occupied areas of the RSFSR, Soviet Union on the Eastern Front.R ...

) under German command made up of Russian, Belorussian and Ukrainian collaborators,

* and Battle Group Reinefarth commanded by SS-''Gruppenführer'' Heinz Reinefarth

Heinz Reinefarth (26 December 1903 – 7 May 1979) was a German SS commander during World War II and government official in West Germany after the war. During the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944 his troops committed numerous atrocities. After t ...

, which consisted of Attack Group Dirlewanger (commanded by Oskar Dirlewanger

Oskar Paul Dirlewanger (26 September 1895 – ) was a German military officer ('' SS-Oberführer'') who served as the founder and commander of the Nazi SS penal unit "Dirlewanger" during World War II. Serving in Poland and in Belarus, his nam ...

), which included Aserbaidschanische Legion

The Azerbaijani Legion (german: Aserbaidschanische Legion) was one of the foreign units of the Wehrmacht. It was formed in December 1941 on the Eastern Front as the ''Kaukasische-Mohammedanische Legion'' (Muslim Caucasus Legion) and was re-desig ...

(part of the Ostlegionen

''Ostlegionen'' ("eastern legions"), ''Ost-Bataillone'' ("eastern battalions"), ''Osttruppen'' ("eastern troops"), and ''Osteinheiten'' ("eastern units") were units in the Army of Nazi Germany during World War II made up of personnel from the ...

), Attack Group Reck (commanded by Major Reck), Attack Group Schmidt (commanded by Colonel Schmidt) and various support and backup units.

The Nazi forces included about 5,000 regular troops; 4,000 Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

personnel (1,000 at Okęcie airport

Warsaw Chopin Airport ( pl, Lotnisko Chopina w Warszawie, ) is an international airport in the Włochy district of Warsaw, Poland. It is Poland's busiest airport with 18.9 million passengers in 2019, thus handling approximately 40% of t ...

, 700 at Bielany

Bielany () is a district in Warsaw located in the north-western part of the city.

Initially a part of Żoliborz, Bielany has been an independent district since 1994. Bielany borders Żoliborz to the south-east, and Bemowo to the south-west. Its ...

, 1,000 in Boernerowo

Boernerowo is a neighbourhood in the Warsaw's borough of Bemowo. Initially the spot was occupied by a small village called Babice, with an eponymous fort located in its centre. In early 1920s the area surrounding the fort was bought by the Polish s ...

, 300 at Służewiec and 1,000 in anti-air artillery

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

posts throughout the city); as well as about 2,000 men of the Sentry Regiment Warsaw (''Wachtregiment Warschau''), including four infantry battalions (''Patz'', ''Baltz'', No. 996 and No. 997), and an SS reconnaissance squadron with ca. 350 men.

Uprising

W-hour or "Godzina W"

After days of hesitation, at 17:00 on 31 July, the Polish headquarters scheduled "W-hour" (from the Polish ''wybuch'', "explosion"), the moment of the start of the uprising for 17:00 on the following day. The decision was a strategic miscalculation because the under-equipped resistance forces were prepared and trained for a series of coordinated surprise dawn attacks. In addition, although many units were already mobilized and waiting at assembly points throughout the city, the mobilization of thousands of young men and women was hard to conceal. Fighting started in advance of "W-hour", notably inŻoliborz

Żoliborz () is one of the northern districts of the city of Warsaw. It is located directly to the north of the City Centre, on the left bank of the Vistula river. It has approximately 50,000 inhabitants and is one of the smallest boroughs of W ...

, and around Napoleon Square and Dąbrowski Square. The Germans had anticipated the possibility of an uprising, though they had not realized its size or strength. At 16:30 Governor Fischer put the garrison on full alert.

That evening the resistance captured a major German arsenal, the main post office and power station and the Prudential building. However, Castle Square, the police district, and the airport remained in German hands. The first days were crucial in establishing the battlefield for the rest of the fight. The resistance fighters were most successful in the

That evening the resistance captured a major German arsenal, the main post office and power station and the Prudential building. However, Castle Square, the police district, and the airport remained in German hands. The first days were crucial in establishing the battlefield for the rest of the fight. The resistance fighters were most successful in the City Centre

A city centre is the commercial, cultural and often the historical, political, and geographic heart of a city. The term "city centre" is primarily used in British English, and closely equivalent terms exist in other languages, such as "" in Fren ...

, Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

, and Wola

Wola (, ) is a district in western Warsaw, Poland, formerly the village of Wielka Wola, incorporated into Warsaw in 1916. An industrial area with traditions reaching back to the early 19th century, it underwent a transformation into an office (co ...

districts. However, several major German strongholds remained, and in some areas of Wola the Poles sustained heavy losses that forced an early retreat. In other areas such as Mokotów

Mokotów , is a ''dzielnica'' (borough, district) of Warsaw, the capital of Poland. Mokotów is densely populated, and is a seat to many foreign embassies and companies. Only a small part of the district is lightly industrialised (''Służewiec ...

, the attackers almost completely failed to secure any objectives and controlled only the residential areas. In Praga

Praga is a district of Warsaw, Poland. It is on the east bank of the river Vistula. First mentioned in 1432, until 1791 it formed a separate town with its own city charter.

History

The historical Praga was a small settlement located at ...

, on the east bank of the Vistula, the Poles were sent back into hiding by a high concentration of German forces. Most crucially, the fighters in different areas failed to link up with each other and with areas outside Warsaw, leaving each sector isolated from the others. After the first hours of fighting, many units adopted a more defensive strategy, while civilians began erecting barricades. Despite all the problems, by 4 August the majority of the city was in Polish hands, although some key strategic points remained untaken.

First four days

The uprising was intended to last a few days until Soviet forces arrived; however, this never happened, and the Polish forces had to fight with little outside assistance. The results of the first two days of fighting in different parts of the city were as follows:

* ''Area I'' (city centre and the Old Town): Units captured most of their assigned territory, but failed to capture areas with strong pockets of resistance from the Germans (the Warsaw University buildings,

The uprising was intended to last a few days until Soviet forces arrived; however, this never happened, and the Polish forces had to fight with little outside assistance. The results of the first two days of fighting in different parts of the city were as follows:

* ''Area I'' (city centre and the Old Town): Units captured most of their assigned territory, but failed to capture areas with strong pockets of resistance from the Germans (the Warsaw University buildings, PAST

The past is the set of all events that occurred before a given point in time. The past is contrasted with and defined by the present and the future. The concept of the past is derived from the linear fashion in which human observers experience t ...

skyscraper, the headquarters of the German garrison in the Saxon Palace

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

, the German-only area near Szucha Avenue, and the bridges over the Vistula). They thus failed to create a central stronghold, secure communication links to other areas, or a secure land connection with the northern area of Żoliborz

Żoliborz () is one of the northern districts of the city of Warsaw. It is located directly to the north of the City Centre, on the left bank of the Vistula river. It has approximately 50,000 inhabitants and is one of the smallest boroughs of W ...

through the northern railway line and the Citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

.

* ''Area II'' (Żoliborz, Marymont

Marymont (from French ''Mont de Marie'' - Mary's Hill) is one of the northern neighbourhoods of Warsaw, Poland, administratively a part of the boroughs of Żoliborz (Marymont-Potok) and Bielany (Marymont-Kaskada and Marymont-Ruda). Named after the ...

, Bielany

Bielany () is a district in Warsaw located in the north-western part of the city.

Initially a part of Żoliborz, Bielany has been an independent district since 1994. Bielany borders Żoliborz to the south-east, and Bemowo to the south-west. Its ...

): Units failed to secure the most important military targets near Żoliborz. Many units retreated outside of the city, into the forests. Although they captured most of the area around Żoliborz, the soldiers of Colonel Mieczysław Niedzielski ("Żywiciel") failed to secure the Citadel area and break through German defences at Warsaw Gdańsk railway station.

* ''Area III'' (Wola

Wola (, ) is a district in western Warsaw, Poland, formerly the village of Wielka Wola, incorporated into Warsaw in 1916. An industrial area with traditions reaching back to the early 19th century, it underwent a transformation into an office (co ...

): Units initially secured most of the territory, but sustained heavy losses (up to 30%). Some units retreated into the forests, while others retreated to the eastern part of the area. In the northern part of Wola the soldiers of Colonel Jan Mazurkiewicz ("Radosław") managed to capture the German barracks, the German supply depot at Stawki Street, and the flanking position at the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery

The Warsaw Jewish Cemetery is one of the largest Jewish cemetery, Jewish cemeteries in Europe and in the world. Located on Warsaw, Warsaw's Okopowa Street and abutting the Christians, Christian Powązki Cemetery, the Jewish necropolis was establis ...

.

* ''Area IV'' (Ochota

Ochota () is a district of Warsaw, Poland, located in the central part of the Polish capital city's urban agglomeration.

The biggest housing estates of Ochota are:

* Kolonia Lubeckiego

* Kolonia Staszica

* Filtry

* Rakowiec

* Szosa Krakowska

...

): The units mobilized in this area did not capture either the territory or the military targets (the Gęsiówka

Gęsiówka () is the colloquial Polish name for a prison that once existed on ''Gęsia'' ("Goose") Street in Warsaw, Poland, and which, under German occupation during World War II, became a Nazi concentration camp.

In 1945–56 the Gęsiówka ...

concentration camp, and the SS and Sipo

The ''Sicherheitspolizei'' ( en, Security Police), often abbreviated as SiPo, was a term used in Germany for security police. In the Nazi era, it referred to the state political and criminal investigation security agencies. It was made up by the ...

barracks on Narutowicz Square). After suffering heavy casualties most of the Home Army forces retreated to the forests west of Warsaw. Only two small units of approximately 200 to 300 men under Lieut. Andrzej Chyczewski ("Gustaw") remained in the area and managed to create strong pockets of resistance. They were later reinforced by units from the city centre. Elite units of the Kedyw

''Kedyw'' (, partial acronym of ''Kierownictwo Dywersji'' ("Directorate of Diversion") was a Polish World War II Home Army unit that conducted active and passive sabotage, propaganda and armed operations against Nazi German forces and collaborato ...

managed to secure most of the northern part of the area and captured all of the military targets there. However, they were soon tied down by German tactical counter-attacks from the south and west.

* ''Area V'' (Mokotów

Mokotów , is a ''dzielnica'' (borough, district) of Warsaw, the capital of Poland. Mokotów is densely populated, and is a seat to many foreign embassies and companies. Only a small part of the district is lightly industrialised (''Służewiec ...

): The situation in this area was very serious from the start of hostilities. The partisans aimed to capture the heavily defended Police Area (''Dzielnica policyjna'') on Rakowiecka Street, and establish a connection with the city centre through open terrain at the former airfield of Mokotów Field

Mokotów Field (Polish: ''Pole Mokotowskie'') is a large park in Warsaw, Poland. A part of the parkland is called Józef Piłsudski Park.

Located between Warsaw's Mokotów district and the city center, the park is one of the largest in Warsaw. ...

. As both of the areas were heavily fortified and could be approached only through open terrain, the assaults failed. Some units retreated into the forests, while others managed to capture parts of Dolny Mokotów, which was, however, severed from most communication routes to other areas.

* ''Area VI'' (Praga

Praga is a district of Warsaw, Poland. It is on the east bank of the river Vistula. First mentioned in 1432, until 1791 it formed a separate town with its own city charter.

History

The historical Praga was a small settlement located at ...

): The Uprising was also started on the right bank of the Vistula, where the main task was to seize the bridges on the river and secure the bridgeheads until the arrival of the Red Army. It was clear that, since the location was far worse than that of the other areas, there was no chance of any help from outside. After some minor initial successes, the forces of Lt.Col. Antoni Żurowski ("Andrzej") were badly outnumbered by the Germans. The fights were halted, and the Home Army forces were forced back underground.

* ''Area VII'' (''Powiat

A ''powiat'' (pronounced ; Polish plural: ''powiaty'') is the second-level unit of local government and administration in Poland, equivalent to a county, district or prefecture ( LAU-1, formerly NUTS-4) in other countries. The term "''powia ...

warszawski''): this area consisted of territories outside Warsaw city limits. Actions here mostly failed to capture their targets.

An additional area within the Polish command structure was formed by the units of the Directorate of Sabotage and Diversion or ''Kedyw

''Kedyw'' (, partial acronym of ''Kierownictwo Dywersji'' ("Directorate of Diversion") was a Polish World War II Home Army unit that conducted active and passive sabotage, propaganda and armed operations against Nazi German forces and collaborato ...

'', an elite formation that was to guard the headquarters and was to be used as an "armed ambulance", thrown into the battle in the most endangered areas. These units secured parts of Śródmieście and Wola; along with the units of ''Area I'', they were the most successful during the first few hours.

Among the most notable primary targets that were not taken during the opening stages of the uprising were the airfields of Okęcie

Okęcie () is the largest neighbourhood of the Włochy district of Warsaw, Poland.

It is the location of Warsaw Chopin Airport and the PZL Warszawa-Okęcie aircraft works, and home to the Okęcie Warszawa professional association football club. ...

and Mokotów Field

Mokotów Field (Polish: ''Pole Mokotowskie'') is a large park in Warsaw, Poland. A part of the parkland is called Józef Piłsudski Park.

Located between Warsaw's Mokotów district and the city center, the park is one of the largest in Warsaw. ...

, as well as the PAST skyscraper overlooking the city centre and the Gdańsk railway station guarding the passage between the centre and the northern borough of Żoliborz.

The leaders of the uprising counted only on the rapid entry of the Red Army in Warsaw ('on the second or third or, at the latest, by the seventh day of the fighting') and were more prepared for a confrontation with the Russians. At this time, the head of the government in exile Mikolajczyk met with Stalin on 3 August 1944 in Moscow and raised the questions of his imminent arrival in Warsaw, the return to power of his government in Poland, as well as the Eastern borders of Poland, while categorically refusing to recognize the Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by George Curzon, 1st Marque ...

as the basis for negotiations.Geoffrey Roberts. Stalin`s war. Yale university press. 2008. p. 212 In saying this, Mikolajczyk was well aware that the USSR and Stalin had repeatedly stated their demand for recognition of the Curzon line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by George Curzon, 1st Marque ...

as the basis for negotiations and categorically refused to change their position. 23 March 1944 Stalin said 'he could not depart from the Curzon Line; in spite of Churchill's post-Teheran reference to his Curzon Line policy as one 'of force', he still believed it to be the only legitimate settlement'. Thus, the Warsaw uprising was actively used to achieve political goals. The question of assistance to the insurrection was not raised by Mikolajczyk, apparently for reasons that it might weaken the position in the negotiations. 'The substance of the two-and-a-half-hour discussion was a harsh disagreement about future of Poland, the Uprising – considered by the Poles as a bargaining chip – turned to be disadvantageous for Mikolajczyk's position since it made him seem like a supplicant (...) Nothing was agreed about the Uprising.' The question of helping the "Home Army" with weapons was only raised, but Stalin refused to discuss this question until the formation of a new government was decided.

Wola massacre

The Uprising reached its

The Uprising reached its apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. For example, the apsides of the Earth are called the aphelion and perihelion.

General description

There are two apsides in any ellip ...

on 4 August when the Home Army soldiers managed to establish front lines in the westernmost boroughs of Wola

Wola (, ) is a district in western Warsaw, Poland, formerly the village of Wielka Wola, incorporated into Warsaw in 1916. An industrial area with traditions reaching back to the early 19th century, it underwent a transformation into an office (co ...

and Ochota

Ochota () is a district of Warsaw, Poland, located in the central part of the Polish capital city's urban agglomeration.

The biggest housing estates of Ochota are:

* Kolonia Lubeckiego

* Kolonia Staszica

* Filtry

* Rakowiec

* Szosa Krakowska

...

. However, it was also the moment at which the German army stopped its retreat westwards and began receiving reinforcements. On the same day SS General Erich von dem Bach

Erich Julius Eberhard von dem Bach-Zelewski (born Erich Julius Eberhard von Zelewski; 1 March 1899 – 8 March 1972) was a high-ranking SS commander of Nazi Germany. During World War II, he was in charge of the Nazi security warfare against tho ...

was appointed commander of all the forces employed against the Uprising. German counter-attacks aimed to link up with the remaining German pockets and then cut off the Uprising from the Vistula river. Among the reinforcing units were forces under the command of Heinz Reinefarth

Heinz Reinefarth (26 December 1903 – 7 May 1979) was a German SS commander during World War II and government official in West Germany after the war. During the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944 his troops committed numerous atrocities. After t ...

.

On 5 August Reinefarth's three attack groups started their advance westward along '' Wolska'' and ''Górczewska'' streets toward the main east–west communication line of Jerusalem Avenue

Jerusalem Avenue ( pl, Aleje Jerozolimskie) is one of the principal streets of the capital city of Warsaw in Poland. It runs through the City Centre along the East-West axis, linking the western borough of Wola with the bridge on the Vistula Riv ...

. Their advance was halted, but the regiments began carrying out Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

's orders: behind the lines, special SS, police and ''Wehrmacht'' groups went from house to house, shooting the inhabitants regardless of age or gender and burning their bodies. Estimates of civilians killed in Wola and Ochota range from 20,000 to 50,000, 40,000 by 8 August in Wola alone, or as high as 100,000. The main perpetrators were Oskar Dirlewanger