Battle Of The Bogside on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of the Bogside was a large three-day

Chapter 3: August

. Reproduced by

In January 1969, a march by the radical nationalist group People's Democracy was attacked by off-duty

In January 1969, a march by the radical nationalist group People's Democracy was attacked by off-duty

The annual Apprentice Boys parade on 12 August commemorates the relief of the

The annual Apprentice Boys parade on 12 August commemorates the relief of the

On 13 August,

Battle of the Bogside

', produced and directed by Vinny Cunningham and written by John Peto, won "Best Documentary" at the

Boy with Petrol Bomb and Gas Mask (mural)

Google street view

published in (1969).

The Irish Times. 3 January 2000

''Battle of the Bogside'' Documentary (2004)

{{Authority control 1969 crimes in the United Kingdom 1969 in Northern Ireland 1969 riots 20th century in Derry (city) August 1969 events in the United Kingdom Battles and conflicts without fatalities Battles in 1969 Crime in County Londonderry Military actions and engagements during the Troubles (Northern Ireland) Police misconduct in Northern Ireland Riots and civil disorder in Northern Ireland Royal Ulster Constabulary The Troubles in Derry (city) Urban warfare

riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targete ...

that took place from 12 to 14 August 1969 in Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. Thousands of Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

/Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

residents of the Bogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The large gable-wall murals by the Bogside Artists, Free Derry Corner and the Gasyard Féile (an annual music and arts festival held in a former gasyard) are p ...

district, organised under the Derry Citizens' Defence Association, clashed with the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(RUC) and loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

. It sparked widespread violence elsewhere in Northern Ireland, led to the deployment of British troops, and is often seen as the beginning of the thirty-year conflict known as the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

.

Violence broke out as the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

loyalist Apprentice Boys

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 10,000, founded in 1814 and based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. There are branches in Ulster and elsewhere in Ireland, Scotland, Engla ...

marched past the Catholic Bogside. The RUC drove back the Catholic crowd and pushed into the Bogside, followed by loyalists who attacked Catholic homes.Stetler, Russell. ''The Battle of Bogside: The Politics of Violence in Northern Ireland''Chapter 3: August

. Reproduced by

Conflict Archive on the Internet

CAIN (Conflict Archive on the Internet) is a database containing information about Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland from 1968 to the present. The project began in 1996, with the website launching in 1997. The project is based within Ul ...

(CAIN). Thousands of Bogside residents beat back the RUC with a hail of stones and petrol bomb

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with flammab ...

s.Coogan, Tim Pat. ''The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace''. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. pp.87–90 The besieged residents built barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denot ...

s, set up first aid posts and petrol bomb workshops, and a radio transmitter broadcast messages calling for resistance. The RUC fired CS gas

The compound 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile (also called ''o''-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile; chemical formula: C10H5ClN2), a cyanocarbon, is the defining component of tear gas commonly referred to as CS gas, which is used as a riot control agent ...

into the Bogside – the first time it had been used by UK police. Residents feared the Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

would be sent in and would massacre Catholic residents.

The Irish Army

The Irish Army, known simply as the Army ( ga, an tArm), is the land component of the Defence Forces of Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. The Ar ...

set up field hospital

A field hospital is a temporary hospital or mobile medical unit that takes care of casualties on-site before they can be safely transported to more permanent facilities. This term was initially used in military medicine (such as the Mobile A ...

s near the border and the Irish government

The Government of Ireland ( ga, Rialtas na hÉireann) is the cabinet that exercises executive authority in Ireland.

The Constitution of Ireland vests executive authority in a government which is headed by the , the head of government. The governm ...

called for a United Nations peacekeeping

Peacekeeping by the United Nations is a role held by the Department of Peace Operations as an "instrument developed by the organization as a way to help countries torn by conflict to create the conditions for lasting peace". It is distinguished ...

force to be sent to Derry. On 14 August, the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

were deployed and the RUC were withdrawn. The British Army made no attempt to enter the Bogside, which became a no-go area

A "no-go area" or "no-go zone" is a neighborhood or other geographic area where some or all outsiders are either physically prevented from entering or can enter at risk. The term includes exclusion zones, which are areas that are officially kept o ...

called Free Derry

Free Derry ( ga, Saor Dhoire) was a self-declared autonomous Irish nationalist area of Derry, Northern Ireland, that existed between 1969 and 1972, during the Troubles. It emerged during the Northern Ireland civil rights movement, which sough ...

. This situation continued until October 1969 when military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear recon ...

were allowed in.

Background

Tensions had been building inDerry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

for over a year before the Battle of the Bogside. In part, this was due to long-standing grievances held by much of the city's population. The city had a majority Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

population. In 1961, for example, the population was 53,744, of which 36,049 was Catholic and 17,695 Protestant. However, because of gerrymandering

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

after the partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. I ...

, it had been ruled by the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

since 1925.

Nationalist grievances

Unionists maintained political control of Derry by two means. Firstly,electoral wards

The wards and electoral divisions in the United Kingdom are electoral districts at sub-national level, represented by one or more councillors. The ward is the primary unit of English electoral geography for civil parishes and borough and distri ...

were gerrymandered so as to give unionists a majority of elected representatives in the city. The Londonderry County Borough

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

, which covered the city, had been won by nationalists in 1921. It was recovered by unionists, however, following re-drawing of electoral boundaries by the unionist government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

in the Northern Ireland Parliament

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

.

Secondly, only owners or tenants of a dwelling and their spouses were allowed to vote in local elections. Nationalists argued that these practices were retained by unionists after their abolition in Great Britain in 1945 in order to reduce the anti-unionist vote. Figures show that, in Derry city, nationalists comprised 61.6% of parliamentary electors, but only 54.7% of local government electors. There was also widespread discrimination in employment.

As a result, although Catholics made up 60% of Derry's population in 1961, due to the division of electoral wards, unionists had a majority of 12 seats to 8 on the city council. When there arose the possibility of nationalists gaining one of the wards, the boundaries were redrawn to maintain unionist control. Control of the city council gave unionists control over the allocation of public housing

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, def ...

, which they allocated in such a way as to keep the Catholic population in a limited number of wards. This policy had the additional effect of creating a housing shortage for Catholics.

Another grievance, highlighted by the Cameron Commission into the riots of 1968, was the issue of perceived regional bias; where Northern Ireland government decisions favoured the mainly Ulster Protestant

Ulster Protestants ( ga, Protastúnaigh Ultach) are an ethnoreligious group in the Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived from Britain in the ...

east of Northern Ireland rather than the mainly Catholic west. Examples of such controversial decisions affecting Derry were the decision to close the anti-submarine training school in 1965, adding 600 to an unemployment figure already approaching 20%; the decision to site Northern Ireland's new town at Craigavon Craigavon may refer to:

* Craigavon, County Armagh, a planned town in Northern Ireland

** Craigavon Borough Council, 1972–2015 local government area centred on the planned town

* Viscount Craigavon, title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

** ...

and the siting of Northern Ireland's second university in the mainly unionist town of Coleraine

Coleraine ( ; from ga, Cúil Rathain , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern I ...

rather than Derry, which had four times the population and was Northern Ireland's second biggest city.

Activism

In March 1968, a handful of activists founded theDerry Housing Action Committee

The Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC), was an organisation formed in 1968 in Derry, Northern Ireland to protest about housing conditions and provision.

The DHAC was formed in February 1968 by two socialists and four tenants in response to the ...

(DHAC), with the intention of forcing the government of Northern Ireland to change its housing policies. The group's founders were mostly local members of the Northern Ireland Labour Party

The Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) was a political party in Northern Ireland which operated from 1924 until 1987.

Origins

The roots of the NILP can be traced back to the formation of the Belfast Labour Party in 1892. William Walker stoo ...

, such as Eamonn McCann

Eamonn McCann (born 10 March 1943) is an Irish politician, journalist, political activist, and former councillor from Derry, Northern Ireland. McCann was a People Before Profit (PBP) Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Foyle from 2016 ...

, and members of the James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

Republican Club (the Northern manifestation of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

, which had been banned in Northern Ireland). The DHAC took direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

, such as blocking roads and attending local council meetings uninvited, in order to force them to house Catholic families who had been on the council housing waiting list for a long time. By the middle of 1968, this group had linked up with the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

) was an organisation that campaigned for civil rights in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Formed in Belfast on 9 April 1967,

(NICRA) and were agitating for a broader programme of reform within Northern Ireland.

On 5 October 1968, these activists organised a march through the centre of Derry. However, the demonstration was banned. When the marchers, including Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

Eddie McAteer

Eddie McAteer (25 June 1914 – 25 March 1986) was an Irish nationalist politician in Northern Ireland.

Born in Coatbridge, Scotland, McAteer's family moved to Derry in Northern Ireland while he was young. In 1930 he joined the Inland Revenu ...

and Ivan Cooper

Ivan Averill Cooper (5 January 1944 – 26 June 2019) was an Irish politician from Northern Ireland. He was a member of the Parliament of Northern Ireland and a founding member of the SDLP. He is best known for leading the anti-internment march o ...

, defied this ban they were batoned by the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(RUC). Gerry Fitt

Gerard Fitt, Baron Fitt (9 April 1926 – 26 August 2005) was a politician in Northern Ireland. He was a founder and the first leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), a social democratic and Irish nationalist party.

Early year ...

, the Republican Labour MP for West Belfast, brought three British Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

MPs to observe the march. Fitt took his place at the front of the march and was assaulted by RUC officers. TV pictures of Fitt, a Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

MP, with bloody head and shirt were broadcast around the world. The actions of the police were televised and caused widespread anger across Ireland, particularly among northern nationalists. The following day, 4,000 people demonstrated in solidarity with the marchers in Guildhall Square in the centre of Derry. This march passed off peacefully, as did another demonstration attended by up to 15,000 people on 16 November. However, these incidents proved to be the start of an escalating pattern of civil unrest

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty m ...

that culminated in the events of August 1969.

January to July 1969

In January 1969, a march by the radical nationalist group People's Democracy was attacked by off-duty

In January 1969, a march by the radical nationalist group People's Democracy was attacked by off-duty Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

(B-Specials) members and other Ulster loyalist

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a uni ...

s during the Burntollet bridge incident

Burntollet Bridge was the setting for an attack on 4 January 1969 during the first stages of the Troubles of Northern Ireland. A People's Democracy march from Belfast to Derry was attacked by Ulster loyalists whilst passing through Burntollet ...

, five miles outside Derry. The RUC refused to protect the marchers. When the marchers (many of whom were injured) arrived in Derry on 5 January, fighting broke out between their supporters and the police. That night, police officers broke into homes in the Catholic Bogside area and assaulted several residents. An inquiry led by Lord Cameron concluded that, "a number of policemen were guilty of misconduct, which involved assault and battery, malicious damage to property...and the use of provocative sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

and political slogans". After this point, barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denot ...

s were set up in the Bogside and vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without Right, legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a pers ...

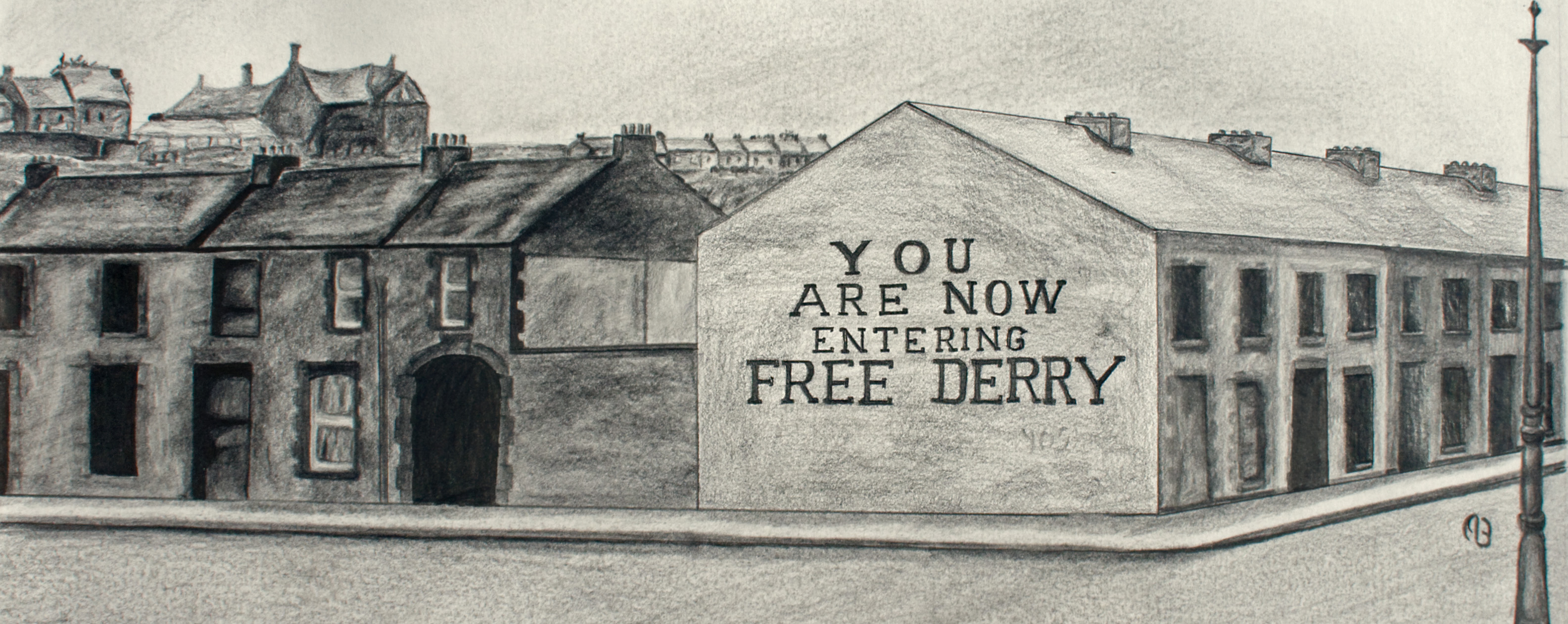

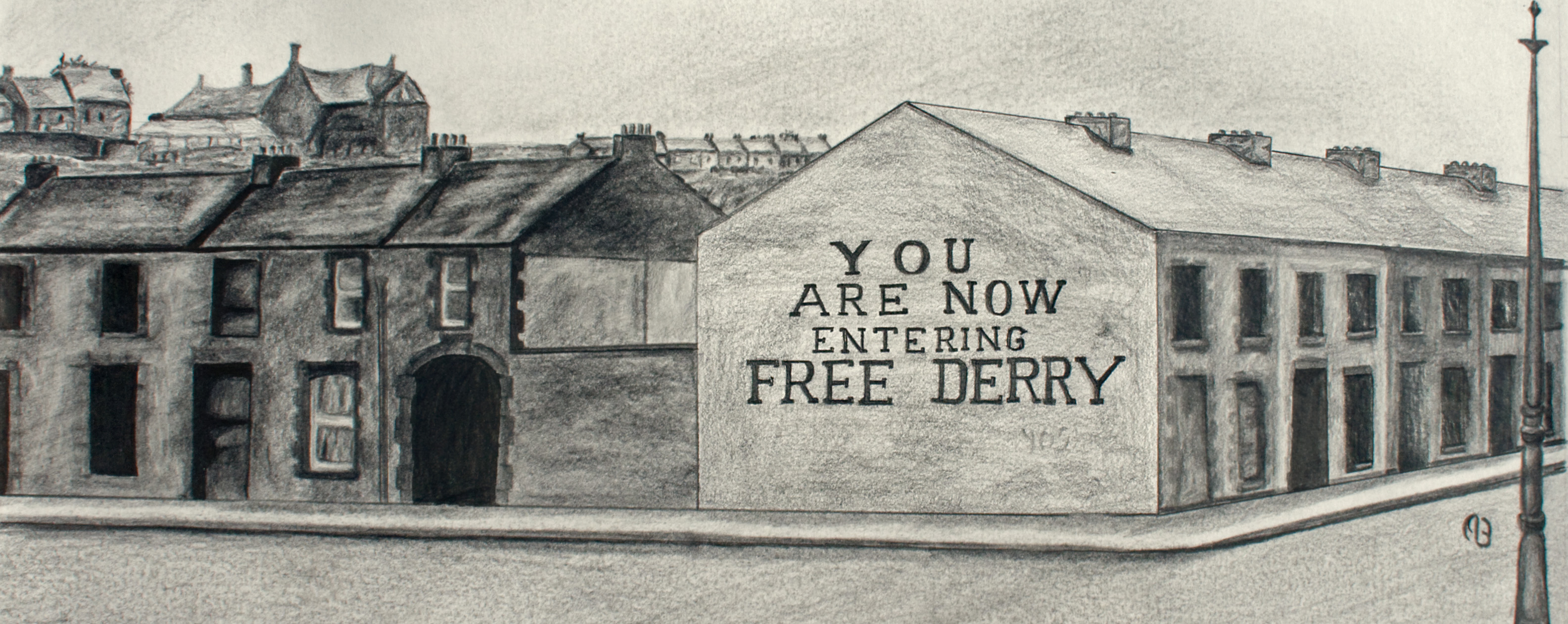

patrols organised to keep the police out. It was at this point that the famous mural

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' is a Spani ...

with the slogan "You are now entering Free Derry

Free Derry ( ga, Saor Dhoire) was a self-declared autonomous Irish nationalist area of Derry, Northern Ireland, that existed between 1969 and 1972, during the Troubles. It emerged during the Northern Ireland civil rights movement, which sough ...

" was painted on the corner of Columbs Street by a local activist named John Casey.

On 19 April there were clashes between NICRA marchers, loyalists and the RUC in the Bogside area. Police officers entered the house of Samuel Devenny (42), a local Catholic who was not involved in the riot, and severely beat him with batons. His teenage daughters were also beaten in the attack. Devenny died of his injuries on 17 July and he is sometimes referred to as the first victim of the Troubles. Others consider John Patrick Scullion, who was killed 11 June 1966 by the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook an armed campaig ...

(UVF), to have been the first victim of the conflict.

On 12 July ("The Twelfth

The Twelfth (also called Orangemen's Day) is an Ulster Protestant celebration held on 12 July. It began in the late 18th century in Ulster. It celebrates the Glorious Revolution (1688) and victory of Protestant King William III of England, W ...

") there was further rioting in Derry, in nearby Dungiven, and in Belfast. The violence arose out of the yearly Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

marches commemorating the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ga, Cath na Bóinne ) was a battle in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II of England and Ireland, VII of Scotland, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and ...

. During the clashes in Dungiven, Catholic civilian Francis McCloskey (67) was beaten with batons by RUC officers and died of his injuries the following day. Following these riots, Irish republicans

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

in Derry set up the Derry Citizens Defence Association

The Derry Citizens' Defense Association (DCDA) was an organisation set up in Derry in July 1969 in response to a threat to nationalist residents from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and civilian unionists, in connection with the annual par ...

(DCDA) with the intention of preparing for future disturbances. The members of the DCDA were initially Republican Club (and possibly IRA

Ira or IRA may refer to:

*Ira (name), a Hebrew, Sanskrit, Russian or Finnish language personal name

*Ira (surname), a rare Estonian and some other language family name

*Iran, UNDP code IRA

Law

*Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, US, on status of ...

) activists, but they were joined by many other young Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

activists and local people. This group stated their aim as firstly to keep the peace, but if this failed, to organise the defence of the Bogside. To this end, they stockpiled materials for barricades and missiles, ahead of the Apprentice Boys of Derry

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 10,000, founded in 1814 and based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. There are branches in Ulster and elsewhere in Ireland, Scotland, Engla ...

march on 12 August, the Relief of Derry parade.

Apprentice Boys march

The annual Apprentice Boys parade on 12 August commemorates the relief of the

The annual Apprentice Boys parade on 12 August commemorates the relief of the Siege of Derry

The siege of Derry in 1689 was the first major event in the Williamite War in Ireland. The siege was preceded by a first attempt against the town by Jacobite forces on 7 December 1688 that was foiled when 13 apprentices shut the gates ...

on 1 August O. S., a Protestant victory. The march was considered highly provocative by many Catholics. Derry activist Eamonn McCann

Eamonn McCann (born 10 March 1943) is an Irish politician, journalist, political activist, and former councillor from Derry, Northern Ireland. McCann was a People Before Profit (PBP) Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Foyle from 2016 ...

wrote that the march "was regarded as a calculated insult to the Derry Catholics".

Although the march did not pass through the Bogside, it passed near to it at the junction of Waterloo Place and William Street. It was here that the initial disturbance broke out. Initially, some loyalists had thrown pennies

A penny is a coin ( pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is t ...

from the top of the walls at Catholics in the Bogside below, in return marbles were fired by slingshot

A slingshot is a small hand-powered projectile weapon. The classic form consists of a Y-shaped frame, with two natural rubber strips or tubes attached to the upper two ends. The other ends of the strips lead back to a pocket that holds the pro ...

. As the parade passed the perimeter of the Bogside, Catholics hurled stones and nails, resulting in an intense confrontation.

The battle

The RUC, who had suffered a barrage of missiles, then moved against the Catholic/nationalist rioters. Whilst the police fought with the rioters at William Street, officers at the Rossville Street barricade encouraged Protestants slingshotting stones across the barricade at the Catholics. The police then tried to alleviate the pressure they were under by dismantling the barricade and moving into the Bogside, on foot and in armoured vehicles. This created a gap through which Protestants also surged through, smashing the windows of Catholic homes. Nationalists lobbed stones andpetrol bomb

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with flammab ...

s from the top of the high-rise Rossville Flats, halting the police advance, and injuring 43 of the 59 officers who made the initial incursion. When the advantage of this position was realised, the youths were kept supplied with stones and petrol bombs. Groups of loyalists and nationalists continued to throw stones and petrol bombs at each other.

The actions of the Bogside residents were co-ordinated to some extent. The DCDA set up a headquarters in the house of Paddy Doherty in Westland Street and tried to supervise the making of petrol bombs and the positioning of barricades. Petrol bomb workshops and first aid posts were set up. A radio transmitter, "Radio Free Derry", broadcast messages encouraging resistance and called on "every able-bodied man in Ireland who believes in freedom" to defend the Bogside. Many local people, however, joined in the rioting on their own initiative and impromptu leaders also emerged, such as McCann, Bernadette Devlin

Josephine Bernadette McAliskey (née Devlin; born 23 April 1947), usually known as Bernadette Devlin or Bernadette McAliskey, is an Irish civil rights leader, and former politician. She served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Mid Ulster in North ...

and others.

The RUC were not well prepared for the riot. Their riot shield

A riot shield is a lightweight protection device, typically deployed by police and some military organizations, though also utilized by protestors. Riot shields are typically long enough to cover an average-sized person from the top of the head to ...

s were too small and did not protect their whole bodies. Furthermore, their uniforms were not flame resistant and some officers were badly burned by petrol bombs. Moreover, there was no system in place to relieve officers, with the result that the same policemen had to serve in the rioting for three days without rest. The overstretched police also resorted to throwing stones back at the Bogsiders, and were helped by loyalists.

Late on 12 August, police began flooding the area with CS gas

The compound 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile (also called ''o''-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile; chemical formula: C10H5ClN2), a cyanocarbon, is the defining component of tear gas commonly referred to as CS gas, which is used as a riot control agent ...

, which caused a range of respiratory injuries among local people. A total of 1,091 canisters, each containing 12.5g of CS; and fourteen canisters containing 50g of CS, were fired into the densely-populated residential area.(extracts available online)On 13 August,

Jack Lynch

John Mary Lynch (15 August 1917 – 20 October 1999) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1966 to 1973 and 1977 to 1979, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 to 1979, Leader of the Opposition from 1973 to 1977, Minister ...

, Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

(Prime Minister) of the Republic of Ireland, made a televised speech about the events in Derry, saying "the Irish Government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse". He said he had "asked the British Government to see to it that police attacks on the people of Derry should cease immediately", and called for a United Nations peacekeeping

Peacekeeping by the United Nations is a role held by the Department of Peace Operations as an "instrument developed by the organization as a way to help countries torn by conflict to create the conditions for lasting peace". It is distinguished ...

force to be sent to Derry. Lynch also announced that the Irish Army

The Irish Army, known simply as the Army ( ga, an tArm), is the land component of the Defence Forces of Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. The Ar ...

was being sent to the border to set up field hospital

A field hospital is a temporary hospital or mobile medical unit that takes care of casualties on-site before they can be safely transported to more permanent facilities. This term was initially used in military medicine (such as the Mobile A ...

s for those civilians injured in the fighting. Some Bogsiders believed that Irish troops were about to be sent over the border to defend them.Daly, Mary. ''Sixties Ireland: Reshaping the Economy, State and Society, 1957–1973''. Cambridge University Press, 2016. pp.343–346

By 14 August, the rioting in the Bogside had reached a critical point. Almost the entire Bogside community had been mobilised by this point, many galvanised by false rumours that St Eugene's Cathedral had been attacked by loyalists. The police were also beginning to use firearms. Two rioters were shot and wounded in Great James Street. The Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

(or B-Specials) were called up and sent to Derry. This was a quasi-military reserve police force, made up almost wholly of Protestants with no training in crowd control

Crowd control is a public security practice in which large crowds are managed in order to prevent the outbreak of crowd crushes, affray, fights involving drunk and disorderly people or riots. Crowd crushes in particular can cause many hundreds ...

. Residents feared the B-Specials would be sent into the Bogside and would massacre Catholics. After two days of almost continuous rioting, during which police were drafted in from all over Northern Ireland, the police were exhausted and were snatching sleep in doorways whenever the opportunity allowed.

On the afternoon of the 14th, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The prime minister of Northern Ireland was the head of the Government of Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920; however, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, as with governors- ...

, James Chichester-Clark

James Dawson Chichester-Clark, Baron Moyola, PC, DL (12 February 1923 – 17 May 2002) was the penultimate Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and eighth leader of the Ulster Unionist Party between 1969 and March 1971. He was Member of the N ...

, took the unprecedented step of requesting the British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

, Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

, to deploy British troops

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkhas ...

to Derry. At about 5pm a company of the 1st Battalion, Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire (who had been on standby at HMS ''Sea Eagle'') arrived and took over from the police. They agreed not to breach the barricades or enter the Bogside. This marked the first direct military intervention by the British government in Ireland since partition

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

. The British troops were at first welcomed by the Bogside residents as a neutral force compared to the RUC and the B-Specials. Only a handful of radicals in the Bogside, notably Devlin, opposed their deployment. However, this good relationship did not last long as the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

escalated.

Over 1,000 people were injured in the rioting in Derry, but no one was killed. A total of 691 policemen were deployed in Derry during the riot, of whom only 255 were still in action at 12:30 on the 15th. Manpower then fluctuated for the rest of the afternoon: the numbers recorded are 318, 304, 374, 333, 285 and finally 327 at 5.30 pm. While some of the fluctuation in numbers can be put down to exhaustion rather than injury, these figures indicate that the police suffered at least 350 serious injuries. How many Bogsiders were injured is unclear, as many injuries were never reported.

Rioting elsewhere

On 13 August, NICRA called for protests across Northern Ireland in support of the Bogside to draw police away from the fighting there. That night it issued a statement:A war ofNationalists held protests at RUC stations ingenocide Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...is about to flare across the North. The CRA demands that all Irishmen recognise their common interdependence and calls upon the Government and people of the Twenty-six Counties to act now to prevent a great national disaster. We urgently request that the Government take immediate action to have aUnited Nations The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...peace-keeping force sent to Derry.

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, Newry

Newry (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Clanrye river in counties Armagh and Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry was founded in 1144 alongside a Cistercian monastery, althoug ...

, Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

, Dungannon

Dungannon () is a town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It is the second-largest town in the county (after Omagh) and had a population of 14,340 at the 2011 Census. The Dungannon and South Tyrone Borough Council had its headquarters in the ...

, Coalisland

Coalisland () is a small town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, with a population of 5,682 in the 2011 Census. Four miles from Lough Neagh, it was formerly a centre for coal mining.

History

Origins

In the late 17th century coal deposits ...

and Dungiven. Some of these became violent. The worst violence was in Belfast, where nationalists clashed with both the police and with loyalists, who attacked Catholic districts. Scores of homes and businesses were burnt out, most of them owned by Catholics, and thousands of mostly Catholic families were driven from their homes. Some viewed this as an attempted pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

against the Catholic minority. Seven people in Belfast were killed and hundreds wounded, five of them Catholic civilians shot by police. Another Catholic civilian was shot dead by B-Specials in Armagh. Both republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

and loyalist paramilitaries

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

were involved in the clashes.Shanahan, Timothy. ''The Provisional IRA and the morality of terrorism''. Edinburgh University Press, 2009. p.13

Documentary

The documentaryBattle of the Bogside

', produced and directed by Vinny Cunningham and written by John Peto, won "Best Documentary" at the

Irish Film and Television Awards

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

in October 2004.

See also

* Timeline of the Troubles *Exercise Armageddon

Exercise ArmageddonClonan, Tom, ''The Irish Times'', 31 August 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2009. was a military exercise by the Republic of Ireland in 1970. The aim of the exercise was "to study, plan for and rehearse in detail the intervention ...

References

External links

Boy with Petrol Bomb and Gas Mask (mural)

Google street view

published in (1969).

The Irish Times. 3 January 2000

''Battle of the Bogside'' Documentary (2004)

{{Authority control 1969 crimes in the United Kingdom 1969 in Northern Ireland 1969 riots 20th century in Derry (city) August 1969 events in the United Kingdom Battles and conflicts without fatalities Battles in 1969 Crime in County Londonderry Military actions and engagements during the Troubles (Northern Ireland) Police misconduct in Northern Ireland Riots and civil disorder in Northern Ireland Royal Ulster Constabulary The Troubles in Derry (city) Urban warfare