battle of Plataea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the

VII.145.1

/ref> This was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.Holland, p. 226 The Allies initially adopted a strategy of blocking land and sea approaches to southern Greece.Holland, pp. 255–57 Thus, in August 480 BC, after hearing of Xerxes' approach, a small Allied army led by Spartan King Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to burn and sack the Boeotian cities that had not surrendered,

Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to burn and sack the Boeotian cities that had not surrendered,  Mardonius moved to break the stalemate by trying to win over the Athenians and their fleet through the mediation of Alexander I of Macedon, offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion.Holland, pp. 336–38 The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was also on hand to hear the offer, and rejected it:

Mardonius moved to break the stalemate by trying to win over the Athenians and their fleet through the mediation of Alexander I of Macedon, offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion.Holland, pp. 336–38 The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was also on hand to hear the offer, and rejected it:

IX.7–9

/ref> According to Herodotus, the Spartans, who were at that time celebrating the festival of Hyacinthus, delayed making a decision until they were persuaded by a guest, Chileos of

IX.13

/ref> He then retreated towards Thebes, hoping to lure the Greek army into territory that would be suitable for the Persian cavalry. Mardonius created a fortified encampment on the north bank of the Mardonius also initiated hit-and-run cavalry attacks against the Greek lines, possibly trying to lure the Greeks down to the plain in pursuit. Although having some initial success, this strategy backfired when the Persian cavalry commander Masistius was killed; with his death, the cavalry retreated.Herodotu

Mardonius also initiated hit-and-run cavalry attacks against the Greek lines, possibly trying to lure the Greeks down to the plain in pursuit. Although having some initial success, this strategy backfired when the Persian cavalry commander Masistius was killed; with his death, the cavalry retreated.Herodotu

IX.22.1–3

/ref> Their morale boosted by this small victory, the Greeks moved forward, still remaining on higher ground, to a new position more suited for encampment and better watered.Herodotus

Their morale boosted by this small victory, the Greeks moved forward, still remaining on higher ground, to a new position more suited for encampment and better watered.Herodotus

IX.25.1–3

/ref> The Spartans and Tegeans were on a ridge to the right of the line, the Athenians on a hillock on the left and the other contingents on the slightly lower ground between. In response, Mardonius brought his men up to the Asopus and arrayed them for battle; However, neither the Persians nor the Greeks would attack; Herodotus claims this is because both sides received bad omens during sacrificial rituals. The armies thus stayed camped in their locations for eight days, during which new Greek troops arrived.Herodotus

IX.39–41

/ref> Mardonius then sought to break the stalemate by sending his cavalry to attack the passes of Mount Cithaeron; this raid resulted in the capture of a convoy of provisions intended for the Greeks. Two more days passed, during which time the supply lines of the Greeks continued to be menaced. Mardonius then launched another cavalry raid on the Greek lines, which succeeded in blocking the Gargaphian Spring, which had been the only source of water for the Greek army (they could not use the Asopus due to the threat posed by Persian archers).Herodotu

IX.49

/ref> Coupled with the lack of food, the restriction of the water supply made the Greek position untenable, so they decided to retreat to a position in front of Plataea, from where they could guard the passes and have access to fresh water.Herodotu

IX.51–52

/ref> To prevent the Persian cavalry from attacking during the retreat, it was to be performed that night. However, the retreat went awry. The Allied contingents in the centre missed their appointed position and ended up scattered in front of Plataea itself. The Athenians, Tegeans and Spartans, who had been guarding the rear of the retreat, had not even begun to retreat by daybreak. A single Spartan division was thus left on the ridge to guard the rear, while the Spartans and Tegeans retreated uphill; Pausanias also instructed the Athenians to begin the retreat and if possible join up with the Spartans.Herodotu

IX.54–55

/ref> However, the Athenians at first retreated directly towards Plataea, and thus the Allied battle line remained fragmented as the Persian camp began to stir.

According to Herodotus, there were a total of 69,500 lightly armed troops – 35,000 helots and 34,500 troops from the rest of Greece; roughly one per hoplite. The number of 34,500 has been suggested to represent one light skirmisher supporting each non-Spartan hoplite (33,700), together with 800 Athenian archers, whose presence in the battle Herodotus later notes. Herodotus tells us that there were also 1,800 Thespians (but does not say how they were equipped), giving a total strength of 108,200 men.

The number of hoplites is accepted as reasonable (and possible); the Athenians alone had fielded 10,000 hoplites at the Battle of Marathon. Some historians have accepted the number of light troops and used them as a population census of Greece at the time. Certainly these numbers are theoretically possible. Athens, for instance, allegedly fielded a fleet of 180 triremes at Salamis,Herodotu

According to Herodotus, there were a total of 69,500 lightly armed troops – 35,000 helots and 34,500 troops from the rest of Greece; roughly one per hoplite. The number of 34,500 has been suggested to represent one light skirmisher supporting each non-Spartan hoplite (33,700), together with 800 Athenian archers, whose presence in the battle Herodotus later notes. Herodotus tells us that there were also 1,800 Thespians (but does not say how they were equipped), giving a total strength of 108,200 men.

The number of hoplites is accepted as reasonable (and possible); the Athenians alone had fielded 10,000 hoplites at the Battle of Marathon. Some historians have accepted the number of light troops and used them as a population census of Greece at the time. Certainly these numbers are theoretically possible. Athens, for instance, allegedly fielded a fleet of 180 triremes at Salamis,Herodotu

VIII.44.1

/ref> manned by approximately 36,000 rowers and fighters. Thus 69,500 light troops could easily have been sent to Plataea. Nevertheless, the number of light troops is often rejected as exaggerated, especially in view of the ratio of seven helots to one Spartiate. For instance, Lazenby accepts that hoplites from other Greek cities might have been accompanied by one lightly armoured retainer each, but rejects the number of seven helots per Spartiate.Lazenby, pp. 227–28 He further speculates that each Spartiate was accompanied by one armed helot, and that the remaining helots were employed in the logistical effort, transporting food for the army. Both Lazenby and Holland deem the lightly armed troops, whatever their number, as essentially irrelevant to the outcome of battle.Holland, p. 400 A further complication is that a certain proportion of the Allied manpower was needed to man the fleet, which amounted to at least 110 triremes, and thus approximately 22,000 men. Since the Battle of Mycale was fought at least near-simultaneously with the Battle of Plataea, then this was a pool of manpower which could not have contributed to Plataea, and further reduces the likelihood that 110,000 Greeks assembled before Plataea. The Greek forces were, as agreed by the Allied congress, under the overall command of Spartan royalty in the person of Pausanias, who was the regent for Leonidas' young son, Pleistarchus, his cousin. Diodorus tells us that the Athenian contingent was under the command of

second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion ...

. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea

Plataea or Plataia (; grc, Πλάταια), also Plataeae or Plataiai (; grc, Πλαταιαί), was an ancient city, located in Greece in southeastern Boeotia, south of Thebes.Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Plataea.” '' Webst ...

in Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, wikt:Βοιωτία, Βοιωτία; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is pa ...

, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s (including Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

, Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

, Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

and Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

), and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

(allied with Greece's Boeotians

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its la ...

, Thessalians, and Macedonians).

The previous year the Persian invasion force, led by the Persian king in person, had scored victories at the battles of Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

and Artemisium and conquered Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

, Phocis

Phocis ( el, Φωκίδα ; grc, Φωκίς) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Va ...

, Boeotia, Euboea and Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean Se ...

. However, at the ensuing Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

, the allied Greek navy had won an unlikely but decisive victory, preventing the conquest of the Peloponnesus

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

. Xerxes then retreated with much of his army, leaving his general Mardonius to finish off the Greeks the following year.

In the summer of 479 BC the Greeks assembled a huge (by ancient standards) army and marched out of the Peloponnesus. The Persians retreated to Boeotia and built a fortified camp near Plataea. The Greeks, however, refused to be drawn into the prime cavalry terrain around the Persian camp, resulting in a stalemate that lasted 11 days. While attempting a retreat after their supply lines were disrupted, the Greek battle line fragmented. Thinking the Greeks were in full retreat, Mardonius ordered his forces to pursue them, but the Greeks (particularly the Spartans, Tegeans and Athenians) halted and gave battle, routing the lightly armed Persian infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and m ...

and killing Mardonius.

A large portion of the Persian army was trapped in its camp and slaughtered. The destruction of this army, and the remnants of the Persian navy allegedly on the same day at the Battle of Mycale

The Battle of Mycale ( grc, Μάχη τῆς Μυκάλης; ''Machē tēs Mykalēs'') was one of the two major battles (the other being the Battle of Plataea) that ended the second Persian invasion of Greece during the Greco-Persian Wars. It ...

, decisively ended the invasion. After Plataea and Mycale the Greek allies would take the offensive against the Persians, marking a new phase of the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

. Although Plataea was in every sense a resounding victory, it does not seem to have been attributed the same significance (even at the time) as, for example, the Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. The battle was the culmination ...

or the allied Greek defeat at Thermopylae.

Background

The Greek city-states of Athens andEretria

Eretria (; el, Ερέτρια, , grc, Ἐρέτρια, , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th cent ...

had supported the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfa ...

against the Persian Empire of Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

in 499–494 BC. The Persian Empire was still relatively young and prone to revolts by its subject peoples.Holland, pp. 47–55 Moreover, Darius was a usurper and had to spend considerable time putting down revolts against his rule. The Ionian Revolt threatened the integrity of his empire, and he thus vowed to punish those involved (especially those not already part of the empire). Darius also saw the opportunity to expand his empire into the fractious world of Ancient Greece.Holland, 171–78

A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the re-conquest of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and forced Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled b ...

to become a fully subordinate client kingdom of Persia; the latter had been a Persian vassal as early as the late 6th century BC. An amphibious task force was then sent out under Datis and Artaphernes in 490 BC, using Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island ar ...

as an intermediate base at, successfully sacking Karystos

Karystos ( el, Κάρυστος) or Carystus is a small coastal town on the Greek island of Euboea. It has about 5,000 inhabitants (12,000 in the municipality). It lies 129 km south of Chalkis. From Athens it is accessible by ferry via Mar ...

and Eretria

Eretria (; el, Ερέτρια, , grc, Ἐρέτρια, , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th cent ...

, before moving to attack Athens. However, at the ensuing Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. The battle was the culmination ...

, the Athenians won a remarkable victory, resulting in the withdrawal of the Persian army to Asia.

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece. However, he died before the invasion could begin. The throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I, who quickly restarted the preparations for the invasion of Greece, including building two pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, uses floats or shallow- draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maximum load that they can carry. ...

s across the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont ( ...

.Holland, pp. 208–11 In 481 BC, Xerxes sent ambassadors around Greece asking for earth and water as a gesture of their submission, but making the very deliberate omission of Athens and Sparta (both of whom were at open war with Persia). Support thus began to coalesce around these two leading states. A congress of city states met at Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

in the late autumn of 481 BC, and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

was formed (hereafter referred to as "the Allies").HerodotuVII.145.1

/ref> This was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.Holland, p. 226 The Allies initially adopted a strategy of blocking land and sea approaches to southern Greece.Holland, pp. 255–57 Thus, in August 480 BC, after hearing of Xerxes' approach, a small Allied army led by Spartan King

Leonidas I

Leonidas I (; grc-gre, Λεωνίδας; died 19 September 480 BC) was a king of the Greek city-state of Sparta, and the 17th of the Agiad line, a dynasty which claimed descent from the mythological demigod Heracles. Leonidas I was son of King ...

blocked the Pass of Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

, while an Athenian-dominated navy sailed to the Straits of Artemisium. Famously, the massively outnumbered Greek army held Thermopylae for three days before being outflanked by the Persians, who used a little-known mountain path. Although much of the Greek army retreated, the rearguard, formed of the Spartan and Thespian contingents, was surrounded and annihilated.Holland, pp. 292–94 The simultaneous Battle of Artemisium, consisting of a series of naval encounters, was up to that point a stalemate; however, when news of Thermopylae reached them, the Greeks also retreated, since holding the straits was now a moot point.

Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to burn and sack the Boeotian cities that had not surrendered,

Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to burn and sack the Boeotian cities that had not surrendered, Plataea

Plataea or Plataia (; grc, Πλάταια), also Plataeae or Plataiai (; grc, Πλαταιαί), was an ancient city, located in Greece in southeastern Boeotia, south of Thebes.Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Plataea.” '' Webst ...

and Thespiae

Thespiae ( ; grc, Θεσπιαί, Thespiaí) was an ancient Greek city (''polis'') in Boeotia. It stood on level ground commanded by the low range of hills which run eastward from the foot of Mount Helicon to Thebes, near modern Thespies.

Histo ...

, before taking possession of the now-evacuated city of Athens. The Allied army, meanwhile, prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The word " isthmus" comes from the An ...

. Xerxes wished for a final crushing defeat of the Allies to finish the conquest of Greece in that campaigning season; conversely, the Allies sought a decisive victory over the Persian navy that would guarantee the security of the Peloponnese.Holland, p. 303 The ensuing naval Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

ended in a decisive victory for the Allies, marking a turning point in the conflict.Holland, pp. 333–35

Following the defeat of his navy at Salamis, Xerxes retreated to Asia with the bulk of his army. According to Herodotus, this was because he feared the Greeks would sail to the Hellespont and destroy the pontoon bridges, thereby trapping his army in Europe. He left Mardonius, with hand-picked troops, to complete the conquest of Greece the following year. Mardonius evacuated Attica and wintered in Thessaly; the Athenians then reoccupied their destroyed city. Over the winter, there seems to have been some tension among the Allies. The Athenians in particular, who were not protected by the Isthmus but whose fleet was the key to the security of the Peloponnese, felt hard done by and demanded that an Allied army march north the following year. When the Allies failed to commit to this, the Athenian fleet refused to join the Allied navy in the spring. The navy, now under the command of the Spartan king Leotychides, stationed itself off Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island ar ...

, while the remnants of the Persian fleet remained off Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a sepa ...

, both sides unwilling to risk battle. Similarly, Mardonius remained in Thessaly, knowing an attack on the Isthmus was pointless, while the Allies refused to send an army outside the Peloponnese.

Mardonius moved to break the stalemate by trying to win over the Athenians and their fleet through the mediation of Alexander I of Macedon, offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion.Holland, pp. 336–38 The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was also on hand to hear the offer, and rejected it:

Mardonius moved to break the stalemate by trying to win over the Athenians and their fleet through the mediation of Alexander I of Macedon, offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion.Holland, pp. 336–38 The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was also on hand to hear the offer, and rejected it:

The degree to which we are put in the shadow by the Medes' strength is hardly something you need to bring to our attention. We are already well aware of it. But even so, such is our love of liberty, that we will never surrender.Upon this refusal, the Persians marched south again. Athens was again evacuated and left to the enemy, leading to the second phase of the

Destruction of Athens

Destruction may refer to:

Concepts

* Destruktion, a term from the philosophy of Martin Heidegger

* Destructive narcissism, a pathological form of narcissism

* Self-destructive behaviour, a widely used phrase that ''conceptualises'' certain kind ...

. Mardonius now repeated his offer of peace to the Athenian refugees on Salamis. Athens, along with Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

and Plataea, sent emissaries to Sparta demanding assistance and threatening to accept the Persian terms if it was not given.HerodotuIX.7–9

/ref> According to Herodotus, the Spartans, who were at that time celebrating the festival of Hyacinthus, delayed making a decision until they were persuaded by a guest, Chileos of

Tegea

Tegea (; el, Τεγέα) was a settlement in ancient Arcadia, and it is also a former municipality in Arcadia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the Tripoli municipality, of which it is a municipal unit ...

, who pointed out the danger to all of Greece if the Athenians surrendered. When the Athenian emissaries delivered an ultimatum to the Spartans the next day, they were amazed to hear that a task force was in fact already ''en route''; the Spartan army was marching to meet the Persians.

Prelude

When Mardonius learned of the Spartan force, he completed the destruction of Athens, tearing down whatever was left standing.HerodotuIX.13

/ref> He then retreated towards Thebes, hoping to lure the Greek army into territory that would be suitable for the Persian cavalry. Mardonius created a fortified encampment on the north bank of the

Asopus

Asopus (; grc, Ἀ̄σωπός ''Āsōpos'') is the name of four different rivers in Greece and one in Turkey. In Greek mythology, it was also the name of the gods of those rivers. Zeus carried off Aegina, Asopus' daughter, and Sisyphus, who h ...

river in Boeotia covering the ground from Erythrae past Hysiae and up to the lands of Plataea.

The Athenians sent 8,000 hoplites, led by Aristides

Aristides ( ; grc-gre, Ἀριστείδης, Aristeídēs, ; 530–468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (δίκαιος, ''dikaios''), he flourished in the early quarter of Athens' Classical period and is remembe ...

, along with 600 Plataean exiles to join the Allied army. The army then marched in Boeotia across the passes of Mount Cithaeron

Cithaeron or Kithairon (Κιθαιρών, -ῶνος) is a mountain and mountain range about sixteen kilometres (ten miles) long in Central Greece. The range is the physical boundary between Boeotia in the north and Attica in the south. It is ...

, arriving near Plataea

Plataea or Plataia (; grc, Πλάταια), also Plataeae or Plataiai (; grc, Πλαταιαί), was an ancient city, located in Greece in southeastern Boeotia, south of Thebes.Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Plataea.” '' Webst ...

, and above the Persian position on the Asopus. Under the guidance of the commanding general, Pausanias, the Greeks took up position opposite the Persian lines but remained on high ground.Holland, pp. 343–49 Knowing that he had little hope of successfully attacking the Greek positions, Mardonius sought to either sow dissension among the Allies or lure them down into the plain. Plutarch reports that a conspiracy was discovered among some prominent Athenians, who were planning to betray the Allied cause; although this account is not universally accepted, it may indicate Mardonius' attempts of intrigue within the Greek ranks.

Mardonius also initiated hit-and-run cavalry attacks against the Greek lines, possibly trying to lure the Greeks down to the plain in pursuit. Although having some initial success, this strategy backfired when the Persian cavalry commander Masistius was killed; with his death, the cavalry retreated.Herodotu

Mardonius also initiated hit-and-run cavalry attacks against the Greek lines, possibly trying to lure the Greeks down to the plain in pursuit. Although having some initial success, this strategy backfired when the Persian cavalry commander Masistius was killed; with his death, the cavalry retreated.HerodotuIX.22.1–3

/ref>

Their morale boosted by this small victory, the Greeks moved forward, still remaining on higher ground, to a new position more suited for encampment and better watered.Herodotus

Their morale boosted by this small victory, the Greeks moved forward, still remaining on higher ground, to a new position more suited for encampment and better watered.HerodotusIX.25.1–3

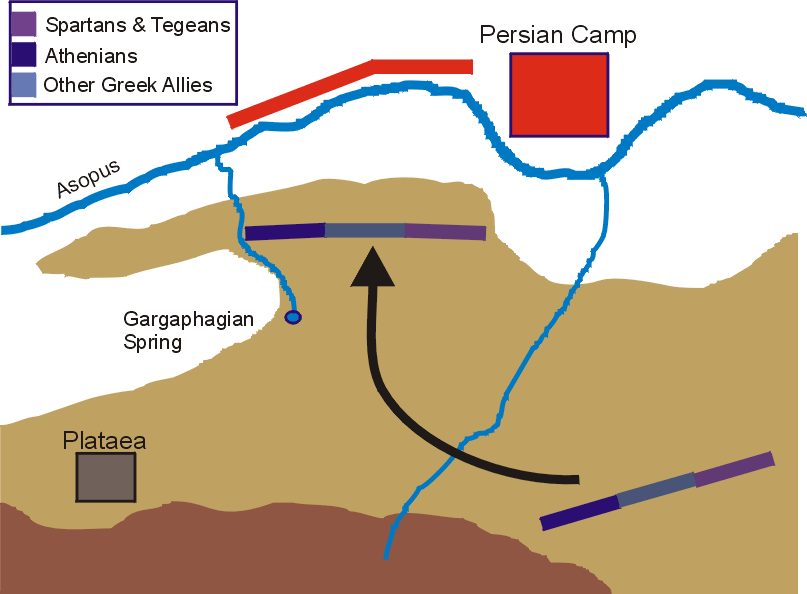

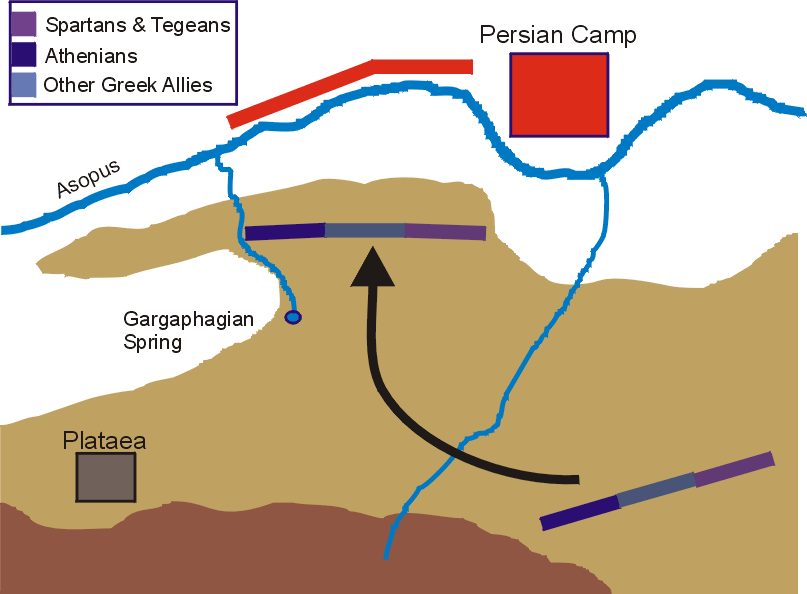

/ref> The Spartans and Tegeans were on a ridge to the right of the line, the Athenians on a hillock on the left and the other contingents on the slightly lower ground between. In response, Mardonius brought his men up to the Asopus and arrayed them for battle; However, neither the Persians nor the Greeks would attack; Herodotus claims this is because both sides received bad omens during sacrificial rituals. The armies thus stayed camped in their locations for eight days, during which new Greek troops arrived.Herodotus

IX.39–41

/ref> Mardonius then sought to break the stalemate by sending his cavalry to attack the passes of Mount Cithaeron; this raid resulted in the capture of a convoy of provisions intended for the Greeks. Two more days passed, during which time the supply lines of the Greeks continued to be menaced. Mardonius then launched another cavalry raid on the Greek lines, which succeeded in blocking the Gargaphian Spring, which had been the only source of water for the Greek army (they could not use the Asopus due to the threat posed by Persian archers).Herodotu

IX.49

/ref> Coupled with the lack of food, the restriction of the water supply made the Greek position untenable, so they decided to retreat to a position in front of Plataea, from where they could guard the passes and have access to fresh water.Herodotu

IX.51–52

/ref> To prevent the Persian cavalry from attacking during the retreat, it was to be performed that night. However, the retreat went awry. The Allied contingents in the centre missed their appointed position and ended up scattered in front of Plataea itself. The Athenians, Tegeans and Spartans, who had been guarding the rear of the retreat, had not even begun to retreat by daybreak. A single Spartan division was thus left on the ridge to guard the rear, while the Spartans and Tegeans retreated uphill; Pausanias also instructed the Athenians to begin the retreat and if possible join up with the Spartans.Herodotu

IX.54–55

/ref> However, the Athenians at first retreated directly towards Plataea, and thus the Allied battle line remained fragmented as the Persian camp began to stir.

Opposing forces

Greeks

According to Herodotus, the Spartans sent 45,000 men – 5,000Spartiate

A Spartiate (cf. its plural Spartiatae 'Spartans') �spärshēˈātē(z)or Spartiate �spärshēˌāt(from respectively the Latin and French forms corresponding to Classical- el, and pl. Σπᾰρτῐᾱ́ται) or ''Homoios'' (pl. ''Homoioi ...

s (full citizen soldiers), 5,000 other Lacodaemonian hoplites (perioeci

The Perioeci or Perioikoi (, ) were the second-tier citizens of the ''polis'' of Sparta until 200 BC. They lived in several dozen cities within Spartan territories (mostly Laconia and Messenia), which were dependent on Sparta. The ''perioeci'' ...

) and 35,000 helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their e ...

(seven per Spartiate). This was probably the largest Spartan force ever assembled. The Greek army had been reinforced by contingents of hoplites from the other Allied city-states, as shown in the table. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

claims in his Bibliotheca historica

''Bibliotheca historica'' ( grc, Βιβλιοθήκη Ἱστορική, ) is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, a ...

that the number of the Greek troops approached one hundred thousand.

According to Herodotus, there were a total of 69,500 lightly armed troops – 35,000 helots and 34,500 troops from the rest of Greece; roughly one per hoplite. The number of 34,500 has been suggested to represent one light skirmisher supporting each non-Spartan hoplite (33,700), together with 800 Athenian archers, whose presence in the battle Herodotus later notes. Herodotus tells us that there were also 1,800 Thespians (but does not say how they were equipped), giving a total strength of 108,200 men.

The number of hoplites is accepted as reasonable (and possible); the Athenians alone had fielded 10,000 hoplites at the Battle of Marathon. Some historians have accepted the number of light troops and used them as a population census of Greece at the time. Certainly these numbers are theoretically possible. Athens, for instance, allegedly fielded a fleet of 180 triremes at Salamis,Herodotu

According to Herodotus, there were a total of 69,500 lightly armed troops – 35,000 helots and 34,500 troops from the rest of Greece; roughly one per hoplite. The number of 34,500 has been suggested to represent one light skirmisher supporting each non-Spartan hoplite (33,700), together with 800 Athenian archers, whose presence in the battle Herodotus later notes. Herodotus tells us that there were also 1,800 Thespians (but does not say how they were equipped), giving a total strength of 108,200 men.

The number of hoplites is accepted as reasonable (and possible); the Athenians alone had fielded 10,000 hoplites at the Battle of Marathon. Some historians have accepted the number of light troops and used them as a population census of Greece at the time. Certainly these numbers are theoretically possible. Athens, for instance, allegedly fielded a fleet of 180 triremes at Salamis,HerodotuVIII.44.1

/ref> manned by approximately 36,000 rowers and fighters. Thus 69,500 light troops could easily have been sent to Plataea. Nevertheless, the number of light troops is often rejected as exaggerated, especially in view of the ratio of seven helots to one Spartiate. For instance, Lazenby accepts that hoplites from other Greek cities might have been accompanied by one lightly armoured retainer each, but rejects the number of seven helots per Spartiate.Lazenby, pp. 227–28 He further speculates that each Spartiate was accompanied by one armed helot, and that the remaining helots were employed in the logistical effort, transporting food for the army. Both Lazenby and Holland deem the lightly armed troops, whatever their number, as essentially irrelevant to the outcome of battle.Holland, p. 400 A further complication is that a certain proportion of the Allied manpower was needed to man the fleet, which amounted to at least 110 triremes, and thus approximately 22,000 men. Since the Battle of Mycale was fought at least near-simultaneously with the Battle of Plataea, then this was a pool of manpower which could not have contributed to Plataea, and further reduces the likelihood that 110,000 Greeks assembled before Plataea. The Greek forces were, as agreed by the Allied congress, under the overall command of Spartan royalty in the person of Pausanias, who was the regent for Leonidas' young son, Pleistarchus, his cousin. Diodorus tells us that the Athenian contingent was under the command of

Aristides

Aristides ( ; grc-gre, Ἀριστείδης, Aristeídēs, ; 530–468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (δίκαιος, ''dikaios''), he flourished in the early quarter of Athens' Classical period and is remembe ...

; it is probable that the other contingents also had their leaders. Herodotus tells us in several places that the Greeks held council during the prelude to the battle, implying that decisions were consensual and that Pausanias did not have the authority to issue direct orders to the other contingents. This style of leadership contributed to the way events unfolded during the battle itself. For instance, in the period immedi